IN

VERITAS: Brotherhood of Saints Marian Andrew

https://ebookmass.com/product/in-veritas-brotherhood-of-saints-marianandrew/

ebookmass.com

The Dublin Murder Mysteries: Books one to six Valerie Keogh

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-dublin-murder-mysteries-books-oneto-six-valerie-keogh/

ebookmass.com

Pumping Station Design, 3rd Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/pumping-station-design-3rd-edition/

ebookmass.com

Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Handbook: UVGI for Air and Surface Disinfection 2009 Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/ultraviolet-germicidal-irradiationhandbook-uvgi-for-air-and-surface-disinfection-2009-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Optics of Charged Particles 2nd Edition Hermann Wollnik

https://ebookmass.com/product/optics-of-charged-particles-2nd-editionhermann-wollnik/

ebookmass.com

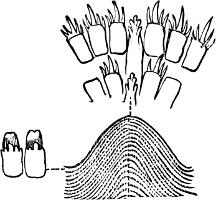

F��. 136. Portion of the radula of Gadinia peruviana Sowb., Chili. × 250 Type (c)

(c) Radula with an indefinite number of marginals, laterals (if present) merging into marginals, central tooth present or absent, inconspicuous, teeth all very small. This type of radula, among the Nudibranchiata, is characteristic of certain sub-genera of Doris (e.g. Chromodoris, Aphelodoris, Casella, Centrodoris), of Hypobranchiaea and Pleurophyllidia; among the Tectibranchiata, of Actaeon, many of the Bullidae, Aplustrum, the Aplysiidae, Pleurobranchus, Umbrella and Gadinia (Figs. 136 and 137, C).

In the Pteropoda there are two types of radula. The Gymnosomata, which are in the main carnivorous, possess a radula with a varying number (4–12) of sickle-shaped marginals, central tooth present or absent. In the Thecosomata, which feed on a vegetable diet, there are never more than three teeth, a central and a marginal on each side; teeth more or less cusped on a square base.

Pulmonata.—The radula of the Testacellidae, or carnivorous land Mollusca, is large, and consists of strong sickle-shaped teeth with very sharp points, arranged in rows with or without a central tooth, in such a way that the largest teeth are often on the outside, and the smallest on the inside of the row (as in Rhytida, Fig. 139). The number and size of the teeth vary. In Testacella and Glandina, they are numerous, consisting of from 30 to 70 in a row, with about 50

F��. 139. Portion of the radula of Rhytida Kraussii Pfr., S. Africa. × 25.

When we reach the Helicidae, we arrive at a type of radula in which the aculeate form of tooth—so characteristic of the Agnatha— disappears even in the marginals, and is replaced by teeth with a more or less quadrate base; the laterals, which are always present, are intermediate in form between the central and the marginals, and insensibly pass into the latter. In size and number of cusps the first few laterals resemble the central tooth; in the extreme marginals the cusps often become irregular or evanescent. As a rule, the teeth are set squarely in the rows, with the exception of the extreme marginals, which tend to slope away on either side. In some Helicidae there is a slight approximation to the Zonitidae in the elongation of the first marginals.

The above is the type of radula occurring in the great family Helicidae, which includes not only Helix proper, with several thousand species, but also Arion, Bulimus, Ariolimax, and other genera. The jaw is almost always strongly transversely ribbed.

In the Orthalicidae (Fig. 140, C) the teeth of the radula, instead of being in straight rows, slope back at an angle of about 45 degrees from the central tooth. The central and laterals are very similar, with an obtuse cusp on rather a long stem; the marginals become bicuspid.

In the Bulimulidae, which include the important genera Placostylus, Amphidromus, Partula, Amphibulimus, and all the

groups of South American Bulimulus, the jaw is very characteristic, being thin, arched, and denticulated at the edges, as if formed of numerous narrow folds overlapping one another. The radula is like that of the Helicidae, but the inner cusp of the laterals is usually lengthened and incurved. In Partula the separation between laterals and marginals is very strongly marked.

The remaining families of Pulmonata must be more briefly described. In the Cylindrellidae there are three distinct types of radula: (a) Central tooth a narrow plate, laterals all very curiously incurved with a blunt cusp, no marginals (Fig. 140, D); (b) radula long and narrow, central tooth as in (a), two laterals, and about eight small marginals; (c) much more helicidan in type, central and laterals obtusely unicuspid, marginals quite helicidan. Type (c) is restricted to Central America, types (a) and (b) are West Indian.

Pupidae: Radula long and narrow; teeth of the helicidan type, centrals and laterals tricuspid on a quadrate base, marginals very small, cusps irregular and evanescent. This type includes Anostoma, Odontostomus, Buliminus, Vertigo, Strophia, Holospira, Clausilia, and Balea

Stenogyridae, including Achatina, Stenogyra, and all its subgenera: Central tooth small and narrow, laterals much larger, tricuspid, central cusp long, marginals similar, but smaller.

Achatinellidae: Two types occur; (a) teeth in very oblique rows, central, laterals, and marginals all of the same type, base narrow, head rather broad, with numerous small denticles (Achatinella proper, with Auriculella and Tornatellina, Fig. 140, E); (b) central tooth small and narrow, laterals bicuspid, marginals as in Helix (Amastra and Carelia).

F��. 140. Portions of the radula of A, Hyalinia nitidula Drap., Yorkshire, with central tooth, first lateral, and a marginal very highly magnified; B, Helix pomatia L., Kent, showing central tooth, laterals, and one extreme marginal, the two former also highly magnified; C, Orthalicus undatus Brug , Trinidad, with three laterals highly magnified; D, Cylindrella rosea Pfr , Jamaica, central tooth and laterals, the same very highly magnified; E, Achatinella vulpina Fér , Oahu, central tooth (c) and laterals, the same highly magnified

Succineidae: Central and laterals helicidan, bi- or tricuspid on a quadrate plate, marginals denticulate on a narrow base; jaw with an accessory oblong plate.

Janellidae: Central tooth very small, laterals and marginals like Achatinellidae (a).

Vaginulidae: Central, laterals, and marginals unicuspid throughout, on same plan.

Onchidiidae: Rows oblique at the centre, straight near the edges; central strong, tricuspid; laterals and marginals very long, falciform, arched, unicuspid.

Auriculidae: Teeth very small; central narrow, tricuspid on rather a broad base; laterals and marginals obscurely tricuspid on a base like Succinea.

Limnaeidae: Jaw composed of one upper and two lateral pieces; central and lateral teeth resembling those of Helicidae; marginals much pectinated and serriform (Fig. 141, A). In Ancylus proper the teeth are of a very different type, base narrow, head rather blunt, with no sharp cusps, teeth similar throughout, except that the marginals become somewhat pectinated (Fig. 141, B); another type more resembles Limnaea.

Chilinidae: Central tooth small, cusped on an excavated triangular base, marginals five-cusped, with a projection as in Physa, laterals comb-like, serrations not deep.

Amphibolidae: Central tooth five-cusped on a broad base, central cusp very large; two laterals only, the first very small, thorn-like, the second like the central tooth, but three-cusped; laterals simple, sabre-shaped.

Scaphopoda.—In the single family (Dentaliidae) the radula is large, and quite unlike that of any other group. The central tooth is a simple broad plate; the single lateral is strong, arched, and slightly cusped; the marginal a very large quadrangular plate, quite simple; formula, 1.1.1.1.1 (Fig. 133, B).

Cephalopoda.—The radula of the Cephalopoda presents no special feature of interest. Perhaps the most remarkable fact about it is its singular uniformity of structure throughout a large number of genera. It is always very small, as compared with the size of the animal, most of the work being done by the powerful jaws, while the digestive powers of the stomach are very considerable.

The general type of structure is a central tooth, a very few laterals, and an occasional marginal or two; teeth of very uniform size and shape throughout. In the Dibranchiata, marginals are entirely absent, their place being always taken, in the Octopoda, by an accessory plate of varying shape and size. This plate is generally absent in the Decapoda. The central tooth is, in the Octopoda, very strong and characteristic; in Eledone and Octopus it is five-cusped, central cusp strong; in Argonauta unicuspid, in Tremoctopus tricuspid. The laterals are always three in number, the innermost lateral having a tendency to assume the form of the central. In Sepia the two inner laterals are exact reproductions of the central tooth; in Eledone, Sepiola, Loligo, and Sepia, the third lateral is falciform and much the largest.

F�� 142 Portion of the radula of Octopus tetracirrhus D Ch , Naples, × 20

In Nautilus, the only living representative of the Tetrabranchiata, there are two sickle-shaped marginals on each side, each of which has a small accessory plate at the base. The two laterals and the central tooth are small, very similar to one another, unicuspid on a square base.

F��. 143. Alimentary canal of Helix aspersa L.: a, anus; b.d, b.d´, right and left biliary ducts; b.m, buccal mass; c, crop; h.g, hermaphrodite gland; i, intestine; i.o, opening of same from stomach (pyloric orifice); l, l´, right and left lobes of liver; m, mouth; oe, oesophagus; r, rectum; s.d, salivary duct; s g, salivary gland; st, stomach; t, left tentacle (After Howes and Marshall, slightly modified )

F�� 145 Gizzard of Scaphander lignarius L : A, showing position with regard to oesophagus (oe) and intestine (i), the latter being full of comminuted fragments of food; p, left plate; p ´ , right plate; p.ac, accessory plate; B, the plates as seen from the front, with the enveloping membranes removed, lettering as in A. Natural size.

F��. 146.—Section of the stomach of Melongena, showing the gastric plates (g.p, g.p,) for the trituration of food; b.d, biliary duct; g.g, genital gland; i, intestine; l, liver; oe, oesophagus; st, stomach. (After Vanstone.)

3. The Oesophagus.—That part of the alimentary canal which lies between the pharynx and the stomach (in Pelecypoda between the mouth and stomach) is known as the oesophagus. Its exact limits are not easy to define, since in many cases the tube widens so gradually, while the muscular structure of its walls changes so slowly that it is difficult to say where oesophagus ends and stomach begins. As a rule, the oesophagus is fairly simple in structure, and consists of a straight and narrow tube. In the Pulmonata and Opisthobranchiata it often widens out into a ‘crop,’ which appears to serve the purpose of retaining a quantity of masticated food before it passes on to the stomach. In Octopus and Patella the crop takes the form of a lobular coecum. In the carnivorous Mollusca the oesophagus becomes complicated by the existence of a varying number of glands, by the action of which digestion appears to begin in some cases before the food reaches the stomach proper.

4. The Stomach.—At the posterior end of the oesophagus lies the muscular pouch known as the stomach, in which the digestion of the food is principally performed. This organ may be, as in Limax, no more than a dilatation of the alimentary canal, or it may, as is usually the case, take the form of a well-marked bag or pocket. The two orifices of the stomach are not always situated at opposite ends; when the stomach itself is a simple enlargement of the wall of one side of the alimentary canal, the cardiac or entering orifice often becomes approximated to the orifice of exit (pyloric orifice).

The walls of the stomach itself are usually thickened and strengthened by constrictor muscles. In some Nudibranchs (Scyllaea, Bornella) they are lined on the inside with chitinous teeth. In Cyclostoma, and some Bithynia, Strombus, and Trochus there is a free chitinous stylet within the stomach.[328] In Melongena (Fig. 146) the posterior end of the oesophagus is provided with a number of hard plate-like ridges, while the stomach is lined with a double row of cuticular knobs, which are movable on their bases of attachment, and serve the purpose of triturating food.[329] Aplysia has several hard plates, set with knobs and spines, and similar organs occur in the Pteropoda. But the most formidable organ for the crushing of food is possessed by the Bullidae, and particularly by Scaphander

(Fig. 145). Here there is a strong gizzard, consisting of several plates connected by powerful cartilages, which crush the shells, which are swallowed whole.

Into the stomach, or into the adjacent portions of the digestive tract, open the ducts which connect with the so-called liver. The functions of this important organ have not yet been thoroughly worked out. The liver is a lobe-shaped gland of a brown-gray or light red colour, which in the spirally-shelled families usually occupies the greater part of the spire. In the Cephalopoda, the two ducts of the liver are covered by appendages which are usually known as the pancreatic coeca; the biliary duct, instead of leading directly into the stomach, passes into a very large coecum (see Fig. 144) or expansion of the same, which serves as a reservoir for the biliary secretions. At the point of connexion between the coecum and stomach is found a valve, which opens for the issue of the biliary products into the stomach, but closes against the entry of food into the coecum. In most Gasteropoda the liver consists of two distinct lobes, between which are embedded the stomach and part of the intestine. In many Nudibranchiata the liver becomes ‘diffused’ or broken up into a number of small diverticula or glands connecting with the stomach and intestine. The so-called cerata or dorsal lobes in the Aeolididae are in effect an external liver, the removal of which to the outside of the body gives the creature additional stomachroom.

The Hyaline Stylet.—In the great majority of bivalves the intestine is provided with a blind sac, or coecum of varying length. Within this is usually lodged a long cylindrical body known as the hyaline or crystalline stylet In a well-developed Mytilus edulis it is over an inch in length, and in Mya arenaria between two and three inches. The bladder-like skin of the stylet, as well as its gelatinoid substance, are perfectly transparent. In the Unionidae there is no blind sac, and the stylet, when present, is in the intestine itself. It is said to be present or absent indifferently in certain species.

The actual function performed by the hyaline stylet is at present a matter of conjecture. Haseloff’s experiments on Mytilus edulis tend to confirm the suggestion of Möbius, that the structure represents a

reserve of food material, not specially secreted, but a chemical modification of surplus food. He found that under natural conditions it was constantly present, but that specimens which were starved lost it in a few days, the more complete the starvation the more thorough being the loss; it reappeared when they were fed again. Schulze, on the other hand, believes that it serves, in combination with mucus secreted by the stomach, to protect the intestine against laceration by sharp particles introduced with the food. W. Clark found that in Pholas the stylet is connected with a light yellow corneous plate, and imagined therefore that it acts as a sort of spring to work the plate in order to comminute the food, the two together performing somewhat the function of a gizzard.[330]

5. and 6. The Intestine, Rectum, and Anus.—The intestine, the wider anal end of which is called the rectum, almost invariably makes a bend forward on leaving the stomach. This is the case in the Cephalopoda, Scaphopoda, and the great majority of Gasteropoda. The exceptions are the bilaterally symmetrical Amphineura, in which the anus is terminal, and many Opisthobranchiata, in which it is sometimes lateral (Fig. 68, p. 159), sometimes dorsal (Fig. 67). The intestine is usually short in carnivorous genera, but long and more or less convoluted in those which are phytophagous. In all cases where a branchial or pulmonary cavity exists, the anus is situated within it, and thus varies its position according to the position of the breathing organ. Thus in Helix it is far forward on the right side, in Testacella, Vaginula, and Onchidium almost terminal, in Patella at the back of the neck, slightly to the right side (Fig. 64, p. 157).

In the rhipidoglossate section of the Diotocardia (Trochus, Haliotis, etc.) the rectum passes through the ventricle of the heart, a fact which, taken in conjunction with others, is evidence of their relationship to the Pelecypoda.

end of the animal, adjacent to and slightly above the adductor muscle.

Anal glands, which open into the rectum close to the anus, are present in some Prosobranchiata, e.g. Murex, Purpura. In the Cephalopoda the anal gland becomes of considerable size and importance, and is generally known as the ink-sac (Fig. 147); it occurs in all known living genera, except Nautilus. The ink-sac consists of a large bag generally divided into two portions, in one of which the colouring matter is secreted, while the other acts as a reservoir for its storage. A long tube connects the bag with the end of the rectum, the mouth of the tube being controlled, in Sepia, by a double set of sphincter muscles.

The Kidneys

The kidneys, nephridia,[331] renal or excretory organs, consist typically of two symmetrical glands, placed on the dorsal side of the body in close connexion with the pericardium. Each kidney opens on the one hand into the mantle cavity, close to the anus (see Fig. 64, p. 157), and on the other, into the pericardium. The venous blood returning from the body passes through the vascular walls of the kidneys, which are largely formed of cells containing uric acid. The blood thus parts with its impurities before it reaches the breathing organs.

The kidneys are paired in all cases where the branchiae are paired, and where the heart has two auricles, i.e. in the Amphineura, the Diotocardia (with the exception of the Neritidae), the Pelecypoda, and all Cephalopoda except Nautilus, which has four branchiae, four auricles, and four kidneys. In other Gasteropoda only one kidney survives, corresponding to the left kidney of Zygobranchiate Gasteropods.

Besides their use as excretory organs the kidneys, in certain groups of the Mollusca, stand in very close relation to the genital glands. In some of the Amphineura the generative products, instead of possessing a separate external orifice of their own, pass from the genital gland into the pericardium and so out through the kidneys

Welcome to our website – the ideal destination for book lovers and knowledge seekers. With a mission to inspire endlessly, we offer a vast collection of books, ranging from classic literary works to specialized publications, self-development books, and children's literature. Each book is a new journey of discovery, expanding knowledge and enriching the soul of the reade

Our website is not just a platform for buying books, but a bridge connecting readers to the timeless values of culture and wisdom. With an elegant, user-friendly interface and an intelligent search system, we are committed to providing a quick and convenient shopping experience. Additionally, our special promotions and home delivery services ensure that you save time and fully enjoy the joy of reading.

Let us accompany you on the journey of exploring knowledge and personal growth!