https://ebookmass.com/product/essentialneuroscience-4th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Neuroscience for Neurosurgeons (Feb 29, 2024)_(110883146X)_(Cambridge University Press) 1st Edition Farhana Akter

https://ebookmass.com/product/neuroscience-for-neurosurgeonsfeb-29-2024_110883146x_cambridge-university-press-1st-editionfarhana-akter/

Empowerment Series: Essential Research Methods for Social Work 4th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-essentialresearch-methods-for-social-work-4th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Essential Clinical Procedures 4th Edition Richard Dehn

https://ebookmass.com/product/essential-clinical-procedures-4thedition-richard-dehn/

Netter's Atlas of Neuroscience 4th Edition David L. Felten

https://ebookmass.com/product/netters-atlas-of-neuroscience-4thedition-david-l-felten/

Essentials of Health Policy and Law (Essential Public Health) 4th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/essentials-of-health-policy-andlaw-essential-public-health-4th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Basic Clinical Neuroscience 3rd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/basic-clinical-neuroscience-3rdedition-ebook-pdf/

Essential guide to marketing planning 4th Revised edition Edition Wood

https://ebookmass.com/product/essential-guide-to-marketingplanning-4th-revised-edition-edition-wood/

Foundations of Behavioral Neuroscience 9th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/foundations-of-behavioralneuroscience-9th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Essential Reproduction (Essentials) 8th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/essential-reproductionessentials-8th-edition-ebook-pdf/

hasbeenaddedinChapter2,“DevelopmentoftheNervousSystem,”which summarizesthekeyaspectsofthesedevelopmentalmechanisms.Inaddition, inrecentyears,greatstrideshavebeenmadeintheidentificationof neurotransmittermalfunctioninseveraldiseases.Therefore,inthethird editionandexpandeduponinthefourthedition,adetailedchapterhasbeen includedonneurotransmittersandimplicationsoftheirmalfunctionsin mentaldisorders.Similarly,geneticabnormalitiesinvolvedincertaindiseases (e.g.,cysticfibrosis,schizophrenia,Huntington’schorea)havebeenbriefly discussed.Malfunctionsoftheimmunesystemincertaindiseases(e.g., Lambert-Eatonsyndrome,multiplesclerosis,myastheniagravis)havealso beendiscussedwhereapplicable.

Thegenesisofthistextbookevolvedoverthepast30years,asaresultof oureffortsinteachingneurosciencetomedicalandgraduatestudentsinways thatwouldmakelearningthesubjectmattersimpleyetmeaningful.After testingavarietyofapproaches,abuilding-blocksapproachinthe presentationofthesubjectmatterprovedmosteffective.Consistentwiththis approach,afteraninitialoverviewofthecentralnervoussystem,including thebrainandspinalcordpresentedinChapter1,thebookbeginswith analysisofthesingleneuron,whichthenexpandstohowneurons communicatewitheachother.Afterdiscussionoftheanatomyofthespinal cordandbrain,thetextcontinueswithadetailedstudyofthesensory,motor, andintegrativesystems.Thisapproachwasdeemedhelpfulbybothstudents andfaculty.Moreover,thebuilding-blocksapproachimprovedstudent performanceonUSMLEandNeuroscienceShelfexaminations.

Thebookcomprises28chaptersandaglossary.Chapters1through3 (“OverviewoftheCentralNervousSystem,”“DevelopmentoftheNervous System,”and“MeningesandCerebrospinalFluid”)provideabackgroundfor understandingthestructuralorganizationofthebrainandspinalcord.These chaptersprovideabasisforamorein-depthanalysisofnervoussystem functionsandclinicaldisorders.

Havingprovidedthestudentwithabasicunderstandingofthegross anatomyandgeneralfunctionsofthebrainandspinalcord,thebookthen introducesaseriesoftopicsdesignedtoprovideanunderstandingofthe

basicelementsofthenervoussystemandtheroletheyplayinneuronal communication.ThesetopicsarediscussedinChapters4through7 (“HistologyoftheNervousSystem,”“ElectrophysiologyofNeurons,” “SynapticTransmission,”and“Neurotransmitters”).Thebasicphysiological processespresentedinthesechapterspreparethestudentforfurther understandingofthediversefunctionsofthenervoussysteminthe subsequentsections.Chapters8through12(“TheSpinalCord,”“Brainstem I:TheMedulla,”“BrainstemII:PonsandCerebellum,”“BrainstemIII:The Midbrain,”and“TheForebrain”)enablethestudenttodevelopan understandingoftheorganizationofthecentralnervoussystemina systematicwayaswellastoacquaintthestudentwiththebasicdisorders relatedtodysfunctionsofeachoftheseregionsofthebrainstemand forebrain.Inthismanner,thestudentwillbegintodevelopanunderstanding ofwhydamagetoagivenstructureproducesaparticularconstellationof deficits.BecauseoftheimportanceofChapter13,“TheCranialNerves,”and theextenttowhichthismaterialistestedonUSMLEexaminations,each cranialnerveispresentedseparatelyintermsofitsstructuralandfunctional propertiesaswellasthedeficitsassociatedwithitsdysfunction.

Atthispointinthestudyofthenervoussystem,thestudenthasdeveloped abasicknowledgeoftheanatomicalorganizationofthecentralnervous systemanditsphysiologyandneurochemistry.Consequently,thestudentis nowreadytostudythesensory,motor,andintegrativesystemsthatrequire theknowledgeaccumulatedthusfar.Thenextsectionofthebookincludes Chapters14through17(“SomatosensorySystem,”“VisualSystem,” “AuditoryandVestibularSystems,”and“OlfactionandTaste”)anddiscusses anatomicalandphysiologicalpropertiesofsensorysystemscoupledwith associatedclinicalcorrelationsresultingfromdeficitsinthesesystems.

Thenextsectionofthetextturnstothestudyofmotorsystemsand includesChapters18to20,“TheUpperMotorNeurons,”“TheBasal Ganglia,”and“TheCerebellum.”Thesechaptersexamine,inanintegrated manner,theanatomical,physiological,andneurochemicalbasesfornormal movementandmovementdisordersassociatedwiththecerebralcortex,basal ganglia,cerebellum,brainstem,andspinalcord.

Thefinalsectionofthetext(Chapters21to28)concernsavarietyof functionsofthenervoussystemcharacterizedbyhigherlevelsofcomplexity. Chapters21to24,“TheAutonomicNervousSystem,”“TheReticular Formation,”“TheHypothalamus,”and“TheLimbicSystem,”include analysesofvisceralprocesses,suchasmechanismsoffeeding,drinking, sexualbehavior,endocrinefunction,aggressionandrage,fear,sleep,and wakefulness.Inaddition,ananalysisofthestructure,functions,and dysfunctionsofthecerebralcortexisprovidedinChapter25,“TheThalamus andCerebralCortex.”Inthefourthedition,anumberofclinicalsyndromes frequentlyaskedonUSMLEhavebeenaddedtothischapter.Inthisthird editionofourtext,Chapters26and27,“BloodSupplyoftheCentral NervousSystem”and“VascularSyndromes,”wereplacedtowardtheendof thebookbecausebythispointthestudenthasgainedadeeperunderstanding andappreciationofbrainstemsyndromesthanifthatmaterialhadbeen presentedearlierinthetext.Thisapproachhasbeenmaintainedinthefourth editionbecauseplacingthesetwochaptersback-to-backhasallowedthe studenttomoreeffectivelyrelatethedistributionofthebloodsupply (Chapter26)tovascularsyndromes(Chapter27),whichconstitutesan importantreviewforthestudentonatopicthatisheavilytestedonUSMLE examinations.Thefinalchapter,“BehavioralandPsychiatricDisorders” (Chapter28),examinesdisorderssuchasschizophrenia,depression,anxiety, andobsessivecompulsion.Inthefourthedition,thenumberofbehavioral disordershasbeenexpandedtoincludeamoreextensiveexaminationof drugsofabuse,anxiety,andeatingdisorderswhileretainingimportanttopics suchasdepression,schizophrenia,obsessivecompulsivedisorders,posttraumaticstressdisorder(PTSD),andautismspectrumdisorder.These disordershaveaclearrelationshiptoabnormalitiesinneuraland neurochemicalfunctionsand,thus,reflectanimportantcomponentof neuroscience.ThesetopicsalsoreceiveattentionontheUSMLE.

EssentialNeuroscienceprovedtobeahighlyeffectivetoolforstudents andfaculty.Thegoalofthefourthedition,therefore,istoperfecttheformula withwhichwehadsuchsuccess.Forexample,wehavesignificantly increasedthenumbersofphotographsofMRIsthroughoutthetextatkey

locationstosupportbasicandclinicalphenomenapresentedinthose chapters.Inaddition,wehavemaintainedtheimprovementsmadeinthethird edition.Theseincludekeytermsandconceptsofneurosciencethatwere highlightedinboldineachchapterandexplainedinanextensiveglossaryat theendofthebook,whichwasexpandedfromearliereditions.

Also,asaresultofthepositivefeedbackwereceivedinthechangesmade intheearliereditions,wehavemaintainedthesechangesinthefourthedition withrespecttoChapterSummaryTablesattheendofeachchapter.These tablesnotonlyhelpedstudentsreviewchapters,whichwerejuststudied,but alsoservedasvaluable,high-yieldtoolsforstudyandreviewatexamination time.

Inthefourthedition,wehavemaintained,enhanced,andexpanded whereverappropriatethefull-colorillustrations,whichhavebeenuniversally praisedinearliereditionsandwhichwebelieveareevenbetterinthefourth edition.Inaddition,thenumbersoftestquestionsandexplanationsofthe answersattheendofeachchapterhavebeendoubled.Thereisnowatotalof 280testquestions,answers,andexplanationsoftheanswers,whichwill hopefullyprovidethestudentwithathoroughself-testreviewofthekey topicsessentialforagoodunderstandingofthesubjectmatterof neuroscience.

Selectedtopicshavebeenexpandedwhereappropriate.Anumberofthese includememory,cerebrallateralization;neuralrelationshipstopsychiatric issues;discussionofprionsinrelationtoCreutzfeldt-Jakobdisease;andother disorders.

Materialhasalsobeenintegratedinmultipleplaceswhereitwould augmentunderstandingofimportantconcepts.Forexample,thefunctional relationshipsassociatedwiththecerebralcortexareagainreferredtovis-à-vis sensoryandmotorsystems.Extensivecross-referencingamongchaptershas likewisebeenincorporated.

Althoughthistextwasoriginallyprimarilydesignedformedicalstudents whostudyneuroscience,itcanbeusedquiteeffectivelybyneurology residentsandgraduateandundergraduateuniversitystudentsspecializingin biologicalsciences.Inthislatestedition,specialtopicshavebeenreworked

tobetteraccommodatedentalstudents.Theorganizationandfunctionsofthe trigeminalnucleus,forinstance,hasbeenpresentedinamannerappropriate fordentalstudents.

EssentialNeuroscience,fourthedition,distinguishesitselffromothertexts astheconcise,clinicallyrelevantneurosciencetextprovidingbalanced coverageofanatomy,physiology,biology,andbiochemistry.Withafull arrayofpedagogicalfeatures,ithelpsstudentsgainconceptualmasteryof thischallengingdisciplineand,wehope,fomentstheurgetocontinueits exploration.

HredayN.Sapru

AllanSiegel

Acknowledgments

TheauthorsthankDr.LeoWolansky,DepartmentofRadiology,Rutgers NewJerseyMedicalSchool,forgenerouslyprovidinguswiththeMRIsand CTscansusedinChapter27,andDr.LewisBaxter,UniversityofFlorida MedicalSchool,Gainesville,forprovidinganMRIofapatientwith obsessive-compulsivedisordershowninChapter28.Theauthorsalsothank Dr.BarbaraFadem,DepartmentofPsychiatry,RutgersNewJerseyMedical School,forhercritiqueofChapter28.TheauthorsthankDr.Masanobu Maeda,MD,PhD,ProfessorandChairman,DepartmentofPhysiology, WakayamaMedicalUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Japan,forservingas TranslationDirectorfortheJapaneseeditionofthisbook,whichwas publishedbyMaruzenCo,Ltd,Tokyo,Japan.WealsothankMs.AnneRains forherexcellentillustrationsincludedineachoftheeditionsofthisbook.

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Section i Gross Anatomy of the Brain

1 OverviewoftheCentralNervousSystem

GrossAnatomyoftheBrain

NeuroanatomicalTerms

ComponentsoftheCentralNervousSystem

CerebralTopography

LateralSurfaceoftheBrain

FrontalLobe

ParietalLobe

OccipitalLobe

TemporalLobe

MedialSurfaceoftheBrain

Inferior(Ventral)SurfaceoftheCerebralCortex

PosteriorAspectoftheCerebralCortex:TemporalandOccipital Lobes

ForebrainStructuresVisibleinHorizontalandFrontalSectionsofthe Brain

Ventricles

BasalGanglia

Diencephalon

LimbicStructures

TopographyoftheCerebellumandBrainstem

Cerebellum

Brainstem

DorsalViewoftheBrainstem

VentralViewoftheBrainstem

2 DevelopmentoftheNervousSystem

EarlyAspectsofDevelopment

MorphogenesisoftheCentralNervousSystem

TheSpinalCord

TheBrain

Myelencephalon(Medulla)

Metencephalon

Mesencephalon(Midbrain)

Prosencephalon(Forebrain)

MyelinationintheCentralNervousSystem

AbnormalitiesinDevelopmentoftheNervousSystem

SpinaBifida

Syringo(hydro)myelia

TetheredCord

Encephalocele

Dandy-WalkerSyndrome

Anencephaly

FolateTherapyforPreventionofNeuralTubeDefects

MechanismsUnderlyingNeuralDevelopment

SignalInductionandNeuralCellDifferentiation

NeuronalGenerationandCellDeath

FactorsAffectingFormationandSurvivalofNeurons

HowAxonsAreDirectedtoTheirTargetsandSynapsesAre Formed:NeurochemicalSpecificity

3 MeningesandCerebrospinalFluid

TheMeninges

CoveringsoftheBrain

DuraMater

ArachnoidMater

PiaMater

CoveringsoftheSpinalCord

SpinalDuraMater

SpinalArachnoidMater

SpinalPiaMater

LumbarCistern

BrainVentricularSystem

TheChoroidPlexus

CerebrospinalFluid

Formation

Circulation

Functions

Composition

AlterationoftheCerebrospinalFluidinPathologicConditions

TheBlood-BrainBarrierandBlood–CerebrospinalFluidBarrier

DisordersAssociatedWithMeninges

Meningitis

Meningiomas

DisordersoftheCerebrospinalFluidSystem

Hydrocephalus

IncreaseinIntracranialPressure

Section ii The Neuron

4 HistologyoftheNervousSystem

TheNeuron

TheCellMembrane

TheNerveCellBody

TheNucleus

TheCytoplasm

NisslSubstanceorBodies

Mitochondria

GolgiApparatus

Lysosomes

Cytoskeleton

Dendrites

Axon

AxonalTransport

FastAnterogradeTransport

SlowAnterogradeTransport

FastRetrogradeTransport

TypesofNeurons

MultipolarNeurons

BipolarNeurons

Pseudo-UnipolarNeurons

UnipolarNeurons

OtherTypesofNeurons

Neuroglia

Astrocytes

ProtoplasmicAstrocytes

FibrousAstrocytes

RadialGlia

FunctionsofAstrocytes

Oligodendrocytes

Microglia

EpendymalCells

MyelinatedAxons

PeripheralNervousSystem

CentralNervousSystem

DifferencesintheCompositionofMyelinintheCentralNervous

SystemandPeripheralNervousSystem

CompositionofPeripheralNerves

ClinicalConsiderations

DisordersAssociatedWithDefectiveMyelination

MultipleSclerosis

Guillain-BarréSyndrome

NeuronalInjury

InjuryoftheNeuronalCellBody

AxonalDamage

5 ElectrophysiologyofNeurons

Introduction

StructureandPermeabilityoftheNeuronalMembrane

StructureofProteins

MembraneTransportProteins

CarrierProteins(CarriersorTransporters)

ChannelProteins

TransportofSolutesAcrossCellMembranes

SimpleDiffusion

PassiveTransport(FacilitatedDiffusion)

ActiveTransport

Sodium-PotassiumIonPump

CalciumPump

IntracellularandExtracellularIonicConcentrations

ElectrophysiologyoftheNeuron

Terminology

Ion-RelatedTerms

ElectricalCharge–RelatedTerms

CurrentFlow–RelatedTerms

MembranePotential–RelatedTerms

IonChannels

ClassificationofIonChannels

EquilibriumPotentials

IonicBasisoftheRestingMembranePotential

IonicBasisoftheActionPotential

PropagationofActionPotentials

ClinicalConsiderations

Lambert-Eaton(Eaton-Lambert)Syndrome

Guillain-BarréSyndrome

MultipleSclerosis

PrionDiseases

CysticFibrosis

6 SynapticTransmission

Introduction

TypesofSynapticTransmission

ElectricalTransmission

ChemicalTransmission

Cotransmission

TypesofCentralNervousSystemSynapses Receptors

DirectlyGatedSynapticTransmissionataPeripheralSynapse (NeuromuscularJunction)

DirectlyGatedTransmissionataCentralSynapse

ClinicalConsiderations

DiseasesAffectingtheChemicalTransmissionattheNerve–Muscle Synapse

MyastheniaGravis

Lambert-Eaton(Eaton-Lambert)Syndrome

DefectsinMyelination

Charcot-Marie-ToothDisease

DisordersAssociatedWithToxins

Botulism

Tetanus

7 Neurotransmitters

Introduction

Definition

CriteriaUsedforIdentifyingNeurotransmitters

MajorClassesofNeurotransmitters

MechanismofTransmitterRelease

Exocytosis

RecyclingofSynapticVesicleMembranes

StepsInvolvedinNeurotransmitterRelease

Small-MoleculeNeurotransmitters

NeuropeptideNeurotransmitters

IndividualSmall-MoleculeNeurotransmitters

Acetylcholine

Synthesis

Removal Distribution

PhysiologicalandClinicalConsiderations

ExcitatoryAminoAcids:Glutamate

Synthesis

Removal

PhysiologicalandClinicalConsiderations

InhibitoryAminoAcids

γ-AminobutyricAcid

Glycine

Catecholamines

Dopamine

Norepinephrine

Epinephrine

Indoleamines

Serotonin

ImidazoleAmines

Histamine

Purines

NeuroactivePeptides

OpioidPeptides

Nociceptin

PhysiologicalandClinicalConsiderations

Tachykinins:SubstanceP

GaseousNeurotransmitters

NitricOxide

DifferencesFromOtherTransmitters

SynthesisandRemoval

PhysiologicalandClinicalConsiderations

Cotransmission

Receptors

NicotinicAcetylcholineReceptor

N-Methyl-D-AsparticAcidReceptor

KainateReceptor

AMPA/QuisqualateReceptor

GABAA Receptors

GlycineReceptor

5-HT3 Receptor

MetabotropicReceptors

CholinergicMuscarinicReceptors

MetabotropicGlutamateReceptors

DopamineReceptors

AdrenergicReceptors

GABAB Receptors

OpioidReceptors

NociceptinReceptors

Serotonin(5-HT)Receptors

HistamineReceptors

AdenosineReceptors

PatternRecognitionReceptors

Toll-LikeReceptors

MechanismsofRegulationofReceptors

Desensitization

Down-Regulation

IonotropicReceptors

Section iii Organization of the Central Nervous System

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

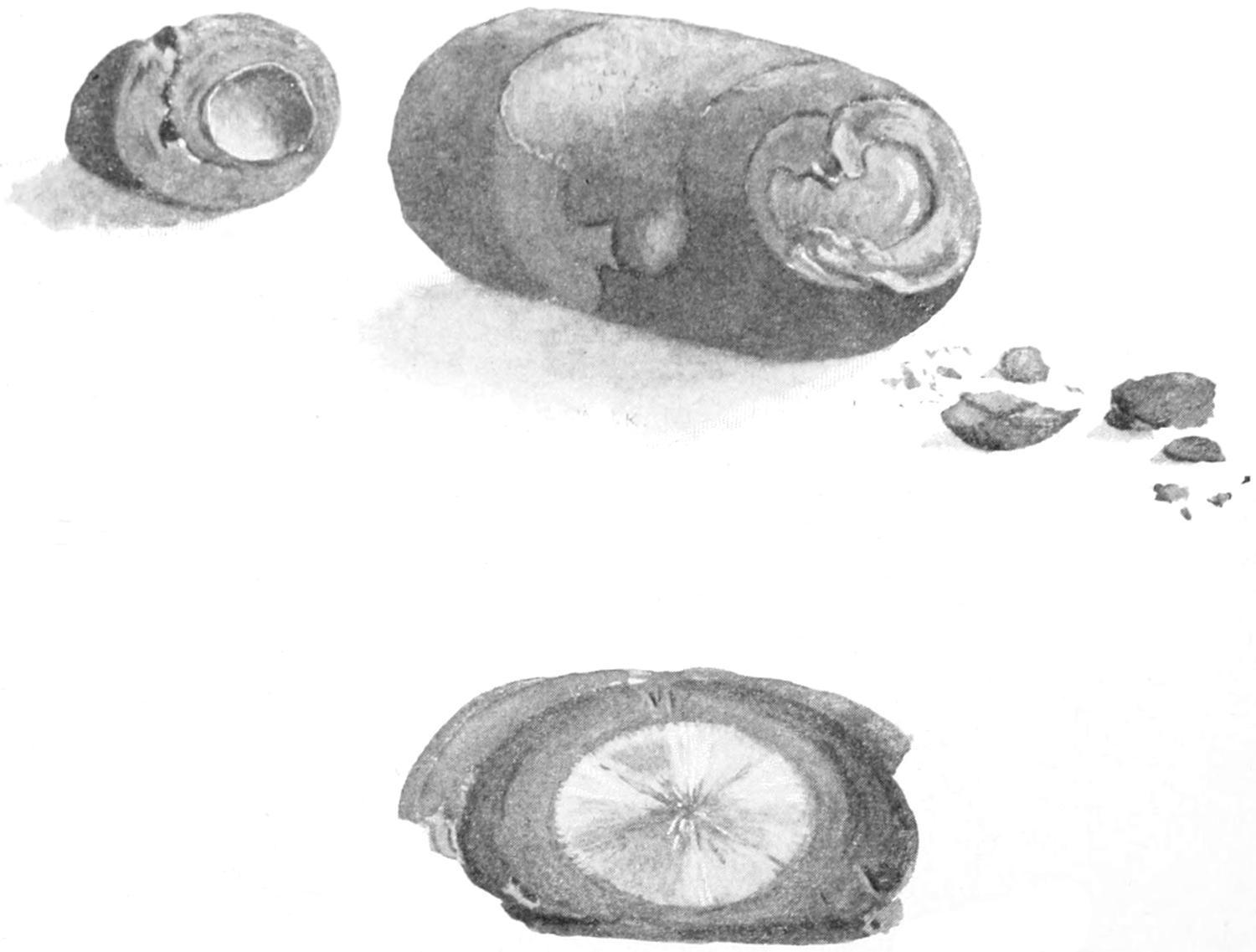

PLATE L

Enterolith with Gallstone for a Nucleus; Removed by Enterotomy. (Richardson.)

This patient was a man of sixty-nine, with symptoms of complete intestinal obstruction. There was no previous history whatever of gallstone. The impaction was high up in the small intestine. The gallstone was removed by a small linear cut which was satisfactorily sutured. The patient died in the course of twentyfour hours.

Stricture may be recognized by the gradual course of the case and by a history of increasing difficulty or of increasing constipation. A stricture as such is not formed within an hour, and in this sense is

the result of a previous more or less active disease. This is true, also, of cancerous stricture.

6. Intrinsic Neoplasms.

—The possibility of both innocent and malignant tumors occurring within the intestinal structures has already been considered. It is obvious that any such growth will cause gradual obstruction by the usual process, or may precipitate by its presence the occurrence of intussusception, of volvulus, or of some kinking by which obstruction is suddenly produced.

7. Extrinsic Neoplasms.

—What has been said above applies equally well to growths not primarily involving the intestine, but encroaching upon it. Thus obstruction may gradually result from retroperitoneal growths, or from the impaction of a growing uterine myoma pressing upon the rectum and finally occluding it. Also cancers growing in various locations encroach upon and finally involve the bowel in conditions which nevertheless were originally quite external to it.

8. Gallstones.

—In the section devoted to the biliary passages the accidents which may occur during gallstone disease have been summarized, and it has there been related how large ones may ulcerate through and drop into the small or even into the large intestine. Enteroliths may be thus produced, which were originally small gallstones that have lodged and grown by accretion until they have reached considerable size, or by gallstones which have suddenly entered the intestine by ulceration above, or by other material which may have collected in some sacculation or diverticulum, where it has received more or less calcareous deposit and has grown by accretion until it produces obstruction, either by occlusion or by causing the intestine to kink. Other foreign bodies may also produce obstruction. Although it has been generally held that whatever may escape through the pylorus may be evacuated from the rectum, nevertheless peculiarly shaped objects become entangled in such a way as to be checked in progress and serve as impacted bodies upon which an accumulation may take place. (See Plate L.)

9. Peritonitis.

—While coprostasis is a feature of almost every case of acute peritonitis the obstruction referred to in this paragraph

comes rather from the adhesion and fixation of bowel from outpour of lymph than from paralysis and ileus in consequence. It may be doubted whether acute peritonitis is ever idiopathic. As seen by the surgeon, at least, it has some point of origin which furnishes ample excuse for its existence. The most common cause in the male is the appendix, and in the female the appendix or the tube. At least onehalf of the cases occurring in general practice originate in one or the other of these ways. Infection may also easily spread from the mesenteric nodes, beginning locally and resulting in adhesions, the disease spreading by a natural process until perhaps the whole abdomen is finally involved. While healthy bowel is ordinarily impervious to germs, when it becomes diseased germs may easily travel from its interior to its exterior and thus set up peritonitis. In this way a purely mechanical original condition may bring about a fatal septic peritonitis. It is known also that intestinal diverticula are subject to exactly the same lesions as is that one in particular which is called the appendix, and the symptoms and sequences of the diverticulitis may simulate those of an acute appendicitis. In acute appendicitis coprostasis and even apparently fatal obstruction are frequently met with. Their occurrence is to be explained not alone by toxemic paralysis (i.e., toxemic ileus), but by the actual mechanical impediments offered by loops of bowel strongly bound together around the appendix in the actual protective effort.

10. Bands.

—Bands of tissue which may cause obstruction of the bowel are neither necessarily long nor large, and one will frequently be astonished to see how trifling a tissue cord may produce intense disturbance. The bands which may be found within the abdominal cavity under these circumstances include those produced by peritoneal adhesions, where the cohering lymph has organized and at the same time stretched, such bands being found to arise from and connect with the bowels alone, to arise from the omentum from any other causes, particularly traumatic, or to occur at any point within the peritoneal cavity. They may be single or multiple. When speaking of Meckel’s diverticulum it was stated how it might be mistaken for a band extending to the region of the umbilicus, and acting as one cause of obstruction. (See Fig. 559.) An adherent

appendix or tube tightly attached at its free extremity may also act as a band, and the former is known to very frequently produce at least a mild form of intestinal obstruction, which may at any time assume acute proportions. The pedicle of an ovarian or other tumor may also, if long, by becoming twisted, include an intestinal loop and thus produce obstruction.

11. Slits and Apertures.

The mesentery is the occasional site of fenestra which apparently are of congenital origin. Through such openings or slits a loop of bowel may easily pass and become strangulated. The same is true of the omentum. Openings in either of these structures are perhaps more frequently the result of traumatisms. Similar conditions result where omental or mesenteric surfaces have united over small areas, leaving pockets or openings in which bowel might be caught. Quite a similar condition results in so-called hernia of bowel into and through the foramen of Winslow. —These causes are not perhaps independent of some of those above mentioned, yet presuppose a certain looping or abnormal festooning of intestine, with the further stretching that occurs as the result of greater loading and the final entanglement of such loops, or their adhesion, in such a way as to become completely occluded. To this result some local inflammatory process may contribute. The condition is often met in connection with pelvic disease of females. Much that may happen to a loop of bowel which has become attached to a growing tumor during its migration, as it gradually changes its shape and position, may be imagined. —Certain congenital defects predispose to acute obstruction. Among these are diverticula, as already mentioned, which may produce trouble, either by incomplete obliteration and separation from the umbilicus, in which event they act as bands or cords, or by becoming acutely inflamed, then attaching themselves and indirectly producing the same effects (Figs. 559 and 562). Even the smaller diverticula or sacculations which extend between the folds of the mesentery may, when infected and inflamed, thicken and cause angular bending of the intestine, with consequent partial obstruction, which later is made complete by the consequences of

12. Intestinal Loops and their Traction Effects.

Strangulation of bowel by a long diverticulum. (Lejars.)

13. Congenital Defects.

local peritonitis, with its dense inevitable adhesions. Statistics show that acquired diverticula occur twice as often as Meckel’s, and nearly as frequently in the small as in the large intestine. They are mostly of the traction variety and occur at the mesenteric border, where they have close relation to the bloodvessels, thus increasing the dangers of operative measures because of possible gangrene from shutting off circulation. Porter has recently collected 188 cases of violent and even fatal trouble thus produced within the abdominal cavity, returning an exceedingly high death-rate after operation, which unfortunately was almost always done late. In nearly all of these cases the diverticula were found within the lower four feet of the ileum. In one case of my own an unobliterated hypogastric artery caused acute obstruction.

14. Postoperative Obstruction.

—Finally cases of postoperative obstruction are met with in a way to bring disappointment and

disaster when everything else has seemed favorable, and constitute a clinical type without any distinct pathological foundation. Most of them are due either to some form of paralytic ileus, or else to local or general peritonitis with its combined sequels of paralysis and adhesion by the gluing of portions covered with exudate. Some of these cases will justify reopening the abdomen, while in others the condition is absolutely helpless because of the septic element present.

General Symptoms of Acute Intestinal Obstruction.

Certain symptoms and signs characterize all cases of acute intestinal obstruction and may be, therefore, included as common to each; consequently they may be considered collectively. The cardinal indications are pain, vomiting, constipation, distention, and collapse.

Pain may be the first indication, and usually is so in invagination, volvulus, and mechanical obstructions generally. It is usually of violent paroxysmal character, continuing at least during the earlier stages, rapidly wearing away the patient’s strength, diminishing as distention increases and nerve endings become paralyzed.

Vomitingis an early or late feature, according to the portion of the alimentary canal obstructed. The more prompt its occurrence presumably the higher in the small bowel the defect. In consequence of the remedies usually administered it will be found that when nothing but stomach contents are ejected it is easier to produce fecal evacuation from below, while the greater the difficulty in securing a return from the lower bowel the lower the obstruction and the more likely the vomited material to become fecal in character. Vomiting once begun is usually continuous until relief is afforded or the patient utterly exhausted.

Constipation or obstipation sooner or later characterize these cases. The tenesmus of intussusception, with the passage of bloody mucus, which may occur in this form, or in volvulus, for instance, does not imply that the bowel itself is not obstructed, nor does the emptying of the larger bowel of an accumulated load necessarily imply that the fecal stream is in motion. Even the passage of flatus usually is promptly shut off, and it is the gas which forms and cannot escape that produces the distention.

Distention gradually becomes excessive, the abdomen becoming ballooned and extremely tympanitic on percussion, while its surface becomes shiny because so stretched. This meteorism is in large degree due to the formation of gas within the bowel proper, but is permitted by the additional features of paralysis of intestinal muscle and weakening of that of the abdominal wall. As it increases the diaphragm is pressed upward and respiration is much impeded, while even the bladder may be compressed below. It affords another reason why fluid which is taken into the stomach is quickly ejected. Characteristic collapsecomes on more or less promptly, according to the nature of the exciting cause, and the date of its occurrence is in some degree an index of its violence.

In dealing with obstructive cases any history that may bear upon the conditions, as of previous peritonitis, appendicitis, of so-called dyspepsia which might indicate gallstone disease or gastric ulcer, or of pelvic conditions which might indicate pyosalpinx or the like, should be obtained. The manner of onset should be learned, whether acute or gradual, with the relative date of the occurrence of pain, vomiting, and stools, along with their character, if there be anything distinctive therein. Past and present history being secured, the most methodical examination of the body should be made, including the physiognomy and general conditions, the attitude (e.g., whether the knees are drawn up, whether the patient is able easily to turn), the type of respiration, and the amount of restlessness. The character of the abdominal movements during respiration should also be noted, as well as the presence of any prominence or the indications of violent peristalsis. By palpation the degree and location of greatest tenderness, the presence of muscle spasm or of tumor may be learned. Careful examination of all the ordinaryhernialoutletsshould be made and the rectum and vagina explored. Revelations thus obtained may also prompt a careful physical examination of the chest. Percussion will show the presence of free or localized fluid or gas, while localized dulness may denote a loop of intestine distended with fluid or impacted feces. Auscultation will enable the surgeon to hear the sounds produced by violent peristalsis or to note the absence of movement within the bowel. A

study of the temperature and the pulse may reveal much in certain cases, especially the inflammatory, and particularly in appendicitis, while the urine may be examined for indican, and a differential blood count made.

Meteorism,constipation,andfecalvomitingofthemselvesindicate acuteobstruction, but furnish no aid as to the nature of the exciting cause. They are, however, sufficient to indicate the wisdom of immediate intervention.

Pathologically every case of intestinal obstruction has an interest of its own. Surgically, however, they are readily grouped as a class of cases in which operation should always be performed early, inasmuch as it offers the better prospect of relief and in which death is the inevitable spontaneous termination. It can scarcely be imagined how a more distressing case than an acute strangulation can be allowed to go to its fatal termination without being offered the prospect of a judicious operation, if only performed early. The disfavor with which operation is received by the general physician, as well as by laymen, is due to the fact that too much time is wasted with futile drug treatment, and that the golden hours when surgical intervention might save are allowed to pass unutilized. Of most of these cases it may be said that dying after operation they have died inspiteofitratherthaninconsequenceofit.

This is particularly true with intussusception and volvulus in young children or infants. Within six hours, in such cases, the harm which may be done is necessarily fatal, and to keep them for a day or more, dosing them with cathartics or making strenuous efforts to relax invagination, is to deprive them of the only measure which offers them any chance. The disrepute into which operative treatment of these cases has fallen in certain quarters is due, then, solely to the fact that the physician does not call the surgeon early, because there is a time in the history of nearly every one of them when it could be saved were mechanical relief afforded.

Treatment.

There are certain cases of obstruction by fecal impaction or lodgement of enteroliths which may be successfully treated by internal or non-operative means. Could these always be diagnosticated it would be known when not to operate. But to wait

until paralysis of the bowel has occurred, or gangrene due to stasis, or perforation have taken place, or septic peritonitis has set in, is to wait far longer than circumstances justify and reflects on those responsible for the delay rather than on the operator or the operation. In general terms, acute intestinal obstruction is always a surgicaldisease.

It is not necessary to wait for accurate diagnosis—recognition of the existence of obstruction alone is all that is required. Conditions rapidly aggravate themselves, and strength is rapidly lost, if we wait for more than distinctive symptoms. There isnopalliative treatment saveoperation, andthedrugsandotherharshmeasures whichare often prescribed serve to intensify and aggravate rather than to relieve.Anodynes given, though administered with the most humane intent, serve only to mask conditions and lead to delay.

Exploration once resolved upon, careful judgment must decide as to where to place the incision. If local indications be present they may be followed. If there be good reason to believe that the original cause was an acute appendicitis, then the incision may be placed upon the right side. In the absence of all indications the surgeon operates most safely in the middle line by an incision below, above, or around the umbilicus, as circumstances may indicate. Edema of the subserous tissue or of the abdominal muscles indicates the presence of pus beneath. Peritoneum should be sought and opened with care, as in the presence of much distended bowel injury to the same may easily occur. The opening once made the operator will be embarrassed from that time until the conclusion of the operation by the distention of the bowels—at least those above the obstruction, and by their being constantly in the way. If a mechanical cause for obstruction be found it will be noted that the intestine above is more distended than that below, which latter may be collapsed and apparently smaller than natural. Thus if a constricting band be found, or an internal hernia, the removal of the obstructing cause will permit of prompt restoration of equal gaseous pressure between the parts above and below.

Scarcely any surgical emergency requires wiser discretion than do cases of this kind. Bands may be double ligated and divided, kinks

straightened out, twists untwisted, invaginations withdrawn, if this be possible by reasonable effort. On the other hand the surgeon should be prepared to find bowel which has apparently lost its vitality or is actually necrotic, either for a few inches or for several feet, and he will soon realize that to leave such gangrenous masses within the abdomen is to accomplish naught, while to remove them is to subject the patient to a procedure longer and more severe than he can bear. He must, then, decide whether to close the abdomen for form’s sake and let the patient die a natural death, or whether to undertake the risk of resection, or perhaps to leave a considerable portion of the intestinal canal upon the outside of the body, opening it and establishing an artificial anus in the hope that the sloughing portion may be cast off, and that the artificial anus, having served its purpose, may be subsequently closed by another operation. Such cases live, though not very often. Here, perhaps as often as anywhere, can be seen the most desperate expedient succeed and the most trifling measure fail.

Another question is what to do with distended and paralyzed intestine, especially when it appears impossible to restore it to the abdominal cavity. Paralyzed as it is, it is almost too much to hope that it may recover its tone, and distended as it is, it is practically unmanageable. To open it at one point would be to empty several loops, at least of gas and probably of fluid fecal matter, all of which will help. One cannot but reflect on the toxic nature of all fecal matter so retained and feel that could it all be evacuated the patient would, other things being equal, be in vastly better condition. And so operators have often made openings, taking all possible precautions to prevent contamination, and have not only evacuated a considerable length of the intestinal canal, but, as suggested by Mixter and others, have washed it out.

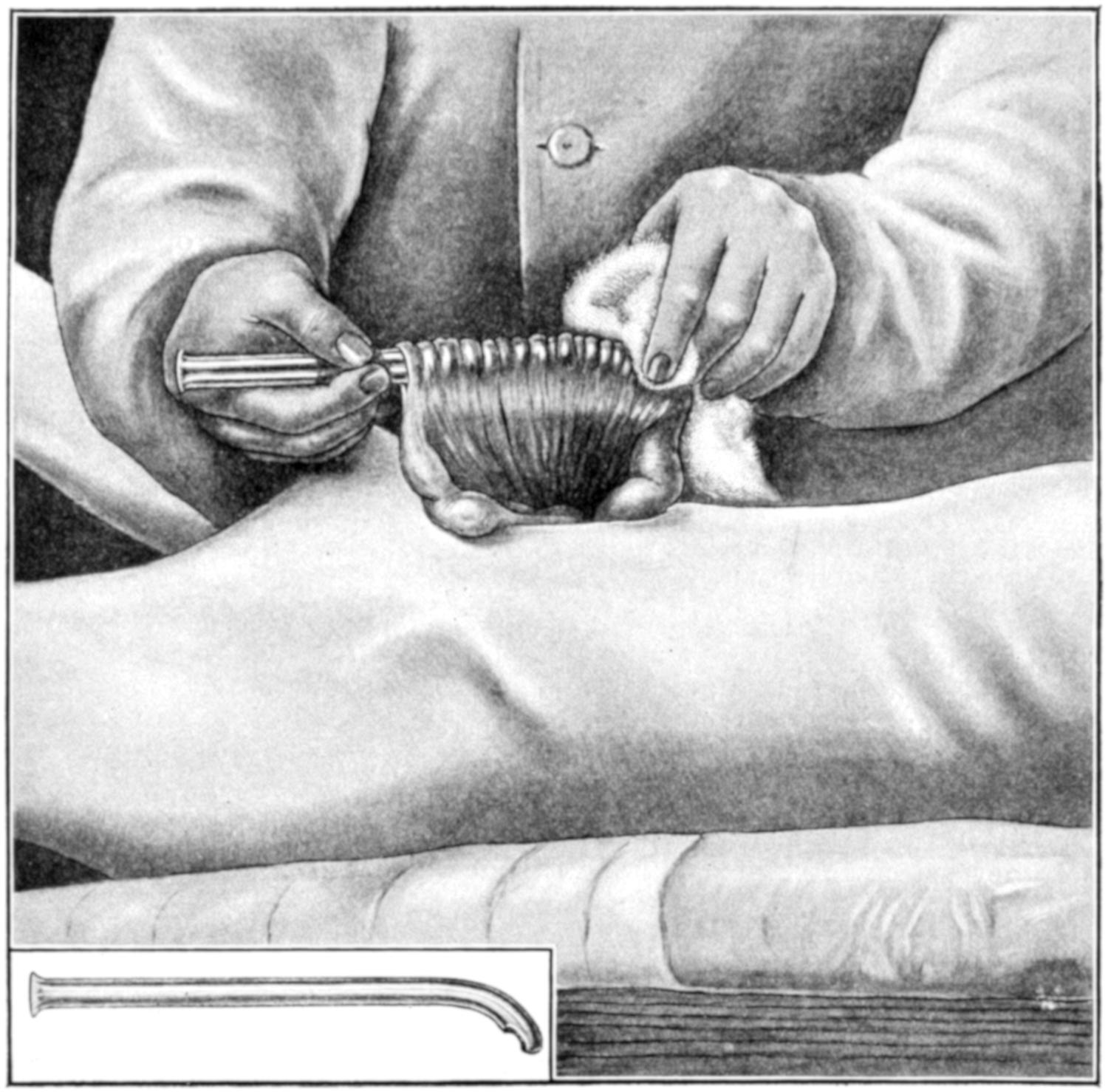

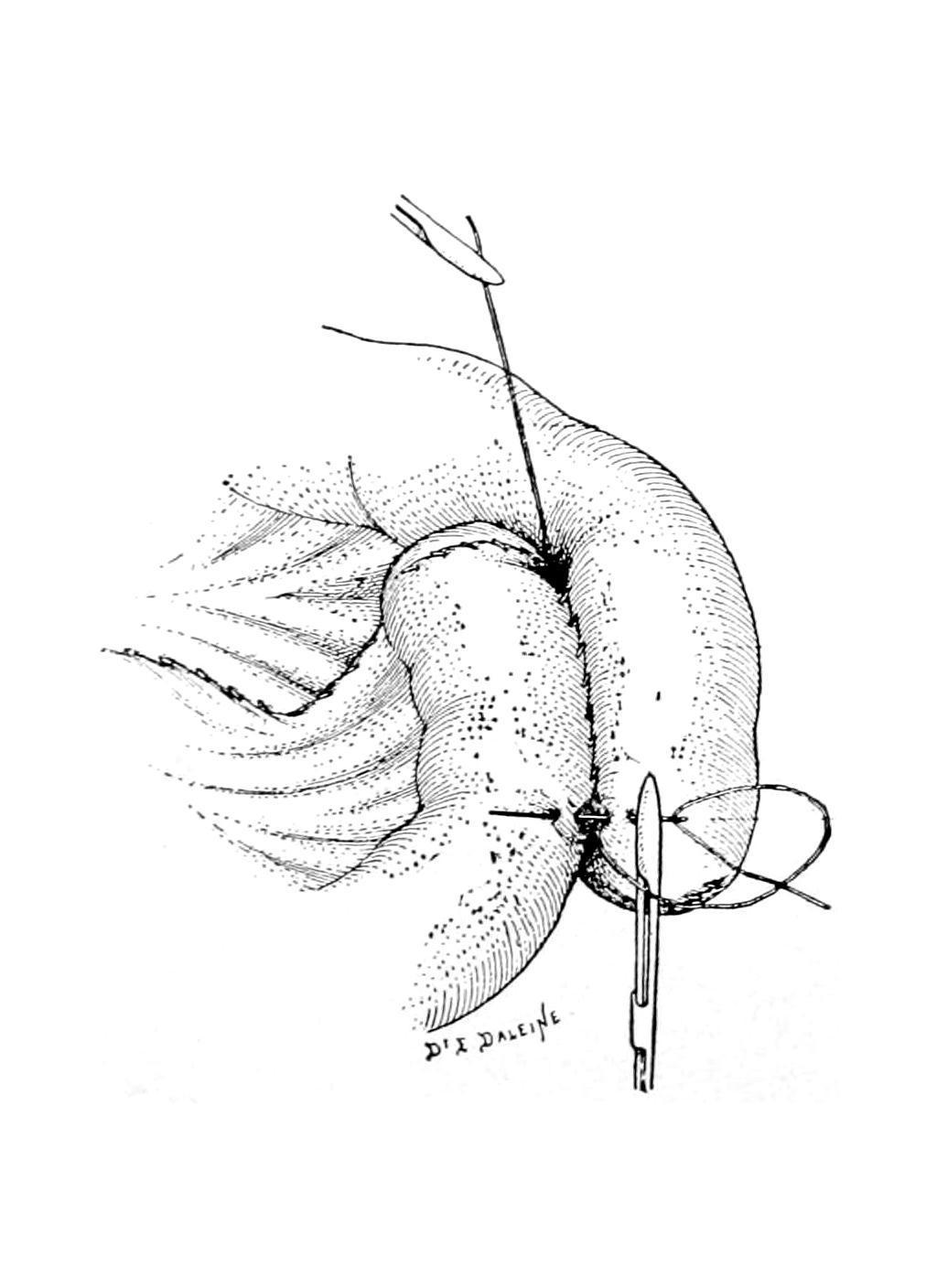

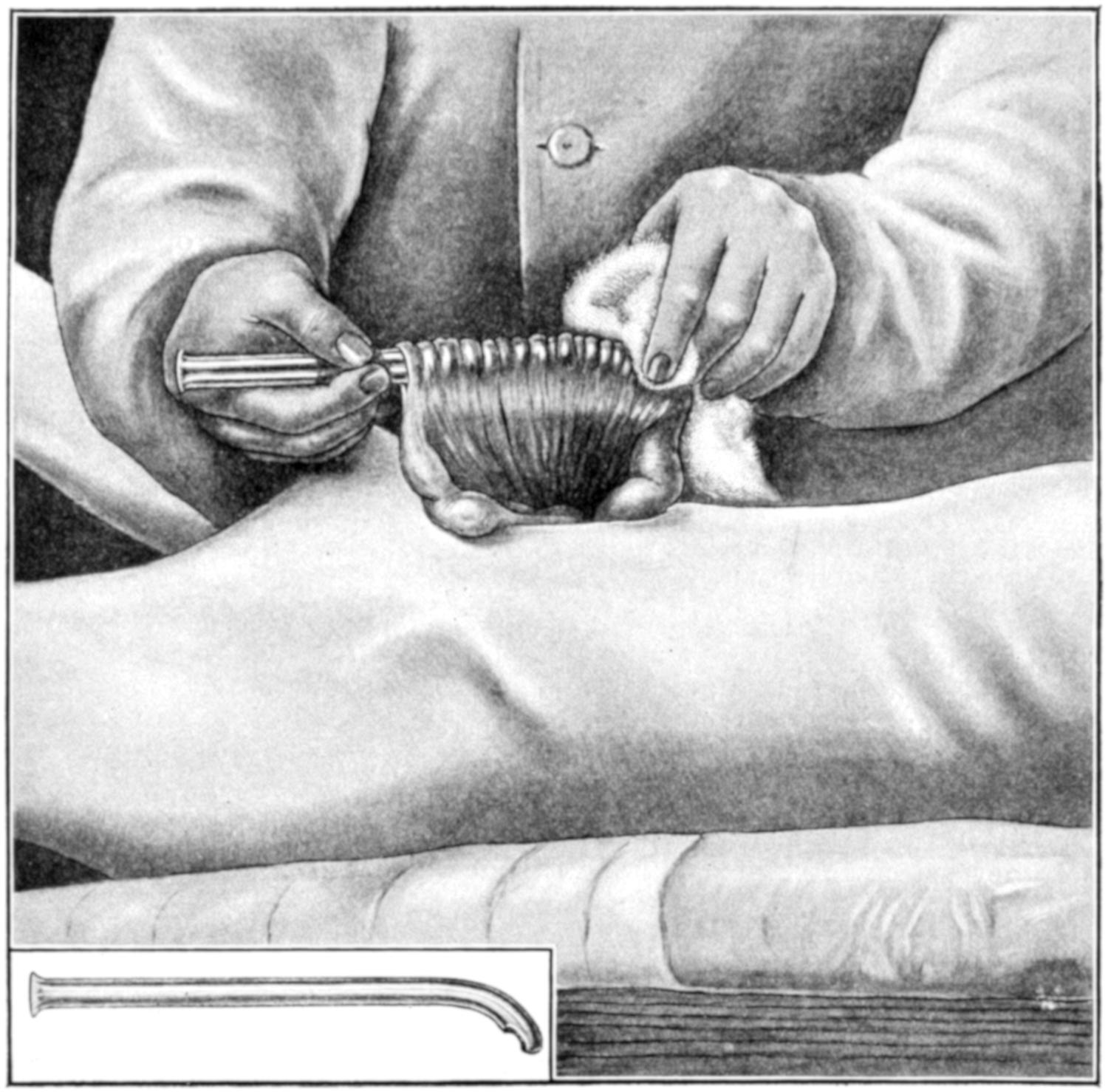

A more perfect method, however, of accomplishing this purpose has been suggested by Monks, of Boston, in the use of a large glass tube, from twenty to twenty-four inches in length, strong and with smooth ends. He has shown how, an opening having been made, say just above the obstruction, it is possible by manipulating the bowel with gauze pads to draw it over the tube (as shown in Fig.

563), to an extent of several feet, and to thus more completely evacuate it than could be accomplished in any other way. Monks is undoubtedly entitled to priority for this suggestion over Moynihan, who has elaborately figured and described it. All in all this permits better management and more complete effect than any other method. The bowel having been emptied, the opening is closed by the usual double row of sutures and is then easily dropped back into the abdominal cavity. Cases occur where this procedure might be carried out at two different points, say above and below the obstruction.

Method of inserting a tube (through an enterostomy opening) a considerable distance into the intestine by drawing the intestine around it with the help of a piece of dry gauze. The tube used in this case has a curved extremity, the opening being on the concavity of the curve. It is shown entire at the lower left corner of the illustration. The longer the abdominal incision and the longer the tube the greater the length of intestine which may be drawn upon it and emptied of its contents. (Monks.)

What may be done with the obstruction produced by local and septic peritonitis, such as is especially seen in acute cases of cholecystitis, appendicitis, and pyosalpinx? Here the surgeon deals not only with twisted, kinked, and obstructed bowel, tensely distended, but with much infected lymph and perhaps a collection of pus and a gangrenous appendix. Such a condition becomes appalling and every such case should be dealt with upon its merits. Any collection of pus should be evacuated and drained, and it must then be decided whether to endeavor to withdraw entangled loops, disengage and straighten them out, or to be content with an artificial anus for temporary purposes, the latter often being the safer course, even though it may lead to a tedious convalescence and the necessity for subsequent operation. It might even be advisable to evacuate pus and remove a sloughing appendix, if it were easily found, and then make an enterostomy, opening at some other point, in order to keep the two procedures and fields of activity quite distinct.

A case may occasionally be seen where the question of affording some relief is paramount to every other consideration, and where, at the same time, the patient’s condition is such as to make anything extra-hazardous. I have saved life under conditions of this kind by making a simple enterostomy under cocaine, the intent being only to attach a loop of distended bowel to the parietal peritoneum and to open it then or a little later, thus establishing an artificial anus. This may be done with local cocaine anesthesia. I have even seen the fecal fistula thus produced close spontaneously in the course of time, and, while the exact character of the lesion was never known, have had the satisfaction of thus saving a life which I believe would otherwise have been lost.

One of the most unfortunate accidents that can occur during operation for acute obstruction is to have the patient practically drown in his own fecal vomit. This may occur either on the operating table or soon after leaving it. The term implies simply this—that there is regurgitation of fecal matter into the stomach, and that as this is ejected by a patient in his unconscious condition he is not able to prevent its aspiration into the trachea, with the occurrence of

all that essentially constitutes drowning. Even a few ounces of fluid material drawn into the lungs, under these circumstances, would be sufficient to cause asphyxia and death.

The accident is to be prevented not alone by lavage, both before and at the conclusion of the operation, but by placing the patient upon his side in such a way that any gush of fluid into the mouth may escape from it and not be sucked into the lung. The amount of fluid that may arise is sometimes astonishing. The introduction of harmless fluid, under these circumstances, would be sufficient, but the entrance into the lungs of a viscid, offensive, and septic fluid, even in small quantity, would quickly serve to induce a septic pneumonia if nothing else. The accident once having occurred, resuscitation is almost impossible. Under the relaxation of anesthesia it may occur without outcry and almost unsuspected, and with the patient on his back, death may be determined even before the attendant has noticed anything particularly wrong. To prevent this accident tubes have been devised having balloons around them which can be inflated with air, to the desired degree, and the esophagus thus be plugged.

Hence it will be seen that the surgeon should temper his measures to the condition of the case, its exigencies and its surroundings. Operation, therefore, may be exceedingly mild or exceedingly severe, taxing the resources of the best-equipped clinic.

Strangulations recognized from surface indications are usually dealt with according to standard indications. Those discovered only after abdominal section are to be dealt with each on its merits.

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTION OF THE BOWEL.

The expressions of chronic obstruction are essentially those of acute, in which they usually terminate, occurring meantime in milder degree. Their causes are nowise different from those tabulated above.

Symptoms.

The symptoms of chronic obstruction are those of intermittent colic, constipation, perhaps with local tenderness, with change in shape of the abdomen due to the primary cause or to

intestinal distention, and in many instances with some characteristic appearance or shape of the feces. Thus the stools are often loose, or scybalous masses when removed by cathartics, and these are followed by diarrheal stools containing many gaseous bubbles. Obstruction of the lower bowel will frequently cause the hardened fecal masses to assume a tape-like shape. With increasing obstruction there is increasing severity of symptoms, until finally they become acute.

Treatment.

—The treatment of chronic obstruction is also operative, either radical or palliative. When the exciting cause can not only be detected on exploration but removed, it should be radical. If, however, this be not possible then enterostomy or enteroanastomosis only can be practised. Thus in cancer of the rectum or sigmoid, colostomy is the last resort. In cancer of the bowel above the sigmoid anastomosis may relieve the obstruction and permit the patient to linger until he dies of the natural progress of the disease. Here, as elsewhere, operation should not be too long delayed. To wait for a chronic obstruction to merge into one of the acute forms, and then to wait until the patient is moribund, is to have deliberately deprived him of that which otherwise might have prolonged his life.

For chronic obstruction whose cause is not easily revealed the hypothesis of cancer affords the most common explanation. This may be intrinsic or extrinsic, so far as the bowel itself is concerned, the results however not differing. It matters but little whether cancer is producing an annular stricture or involving a considerable extent of bowel, something should be done. When health has gradually failed, and obstructive symptoms have come on slowly, and when distinct cachexia is present the presence of cancer within the abdomen may be suspected. When a distinct tumor is palpable or when the abdomen gradually fills with fluid there is little doubt. When to these signs is added pigmentation of the abdominal wall the diagnosis may be considered certain. Even now exploratory section is justified, in the hope that some operative measure may offer comfort and at least temporary relief.

On the other hand, when obstructive symptoms appear and increase without the accompaniment of other serious indications, it

may be hoped that the condition is benign rather than malignant. Obstruction with ascites may possibly be due to tuberculouslesions, which are not uncommon, especially in children. The recognition of enlarged mesenteric nodes would corroborate this diagnosis. A history of typhoid fever or of injuries or foreign bodies might confirm the theory of cicatricial stenosis. The possibility of enteroptosis of the colon and impaction of hardened fecal matters should not be disregarded and that of enteroliths, especially gallstones, not forgotten.

FECAL FISTULA; ARTIFICIAL ANUS.

A fecal fistula implies any communication between the intestinal tract and the exterior of the body or one of its other cavities. Thus it is possible to have a rectovaginal fistula as well as a vesicovaginal. In rare instances we may meet also with intestinal communication with the bladder, the other viscera, or even the pleura or lungs.

Fecal fistulas are always abnormal productions, and result either from congenital causes, previous injury, or disease. Among the traumatic causes may be mentioned penetrations or ruptures of the intestines, injuries to the bowel occurring in the course of abdominal operations (for instance, the inclusion of some part of the bowel wall within a ligature or suture), while the pathological causes include the possibilities of perforation of any form of ulcerative lesion, cancer, actinomycosis, or the secondary sloughing which may follow appendicitis, or even the pressure of a drainage tube. Fistulas result also from escape of foreign bodes (for instance enteroliths or bone fragments), which may work their way into some other viscus, or out through the abdominal wall to the body surface. Old pelvic and abdominal abscesses also occasionally cause perforation and fecal fistulas. These fistulous tracts may be long or short, and direct or indirect. They may also permit the escape of a large amount of fecal matter or the smallest appreciable amount. The majority of them tend to close spontaneously in the course of time, but this time is sometimes so prolonged that a surgical operation is preferable to waiting for natural processes. The communications may be high in

the intestinal canal. In such a case matter that escapes will be but partially digested and will have the character of chyme rather than of feces; and patients suffer in consequence, as products of digestion are not complete and opportunities for absorption have been too limited, and they are deprived of all that should normally happen further along in the bowel. In such a case there is temptation to operate much earlier than is advisable. Another form of fistula results from certain cases of strangulated hernia, in consequence of necrosis of the strangulated loop of bowel. In fact this is true of any of the mechanical causes of acute obstruction, where this expedient may be resorted to under compulsion and we produce a fistula as an emergency measure.

The difference between intestinal or fecal fistula and artificial anus is that the former is an undesirable and untoward event, whereas the latter is deliberately produced by operation practised for the purpose. Artificial anus is in the main limited to cases of cancerous or other hopeless or inoperable obstruction of the lower bowel, and in such case is purely a palliative measure. It is made occasionally at the upper end of the colon in order to give a diseased colon physiological rest and permit of more perfect irrigation of that tube, the intent being to later close the opening. It is an inevitable emergency measure in certain cases of acute obstruction, where the patient is in no condition to bear anything more extensive or prolonged.

The operation for making an artificial anus, usually referred to as enterostomyor colostomy, will be described below.

Fecal fistulas should be treated largely according to their causes; when they are the product of actinomycotic or cancerous disease little can be done, and perhaps nothing should be. On the other hand, when resulting from traumatism, from sloughing of some portion of the bowel, or from strangulation, much can be accomplished.

A small, fistulous tract should be kept clean and stimulated occasionally with silver nitrate or something of the kind, and perhaps by introducing into it every day a small piece of gauze, which provokes the granulation process as well as fills the opening. It is

bad practice, however, to simply close the outer end and let the lower portion distend with feces. Much will depend upon whether it now connects with the bowel. This may be determined by injecting into the fistula some methyl blue and then noting the subsequent stools. When communication with the bowel is evidently free the surgeon may feel like making a deeper operation, perhaps with intestinal suture or even intestinal resection, whereas if there be little or no actual fecal leakage it may be sufficient to enlarge the outer end of the fistula, to thoroughly scrape it with the sharp spoon, and then, lightly packing it, see it close with granulations. A passage-way which is exceedingly short may be treated by simple superficial plastic operation, including freshening of the entire margin of the opening and the passage around it, and a purse-string suture, with or without a circular incision of the skin. By drawing this suture tight the external opening may be closed. This is a neat way in which to dispose of a small fistulous opening resulting from a previous enterostomy or appendicitis operation.

A rectovaginalfistulamay be closed by formal operation, similar to that for closure of a vesicovaginal fistula, based upon the simple principle of freshening the edges of the opening and then holding them together with suitably placed sutures. A rectovesical fistula would, in most instances at least, require a laparotomy, with careful separation of the rectum from the bladder, and then a separate suture of each opening. Such an operation might be quite difficult, made so not by its plan of performance but by the conditions which necessitated it. Any bladder thus attacked should be kept perfectly empty for several days by the use of a self-retaining catheter. Every case of fecal communication with any large abscess cavity, or through the diaphragm, directly or indirectly, as with a bronchus, should be treated on its individual merits, it being a grave question whether operation would be indicated or not.

Certain fecal fistulas will justify more formidable operation, in which, after opening the abdomen and carefully protecting its contents against contamination, the adhesions should be separated entirely and that portion of the bowel which is involved removed, making either an end-to-end suture or a lateral approximation. If

this be done it will be best also to completely excise the old fistulous tract through the abdominal wall, and to remove everything that was involved in the previous condition. It is possible to atone for almost every opening of this character, save those produced by some seriously malignant disease. If such a condition be the result of cancerous extension then it is practically hopeless.

OPERATIONS UPON THE INTESTINE.

Intestinal Suture.

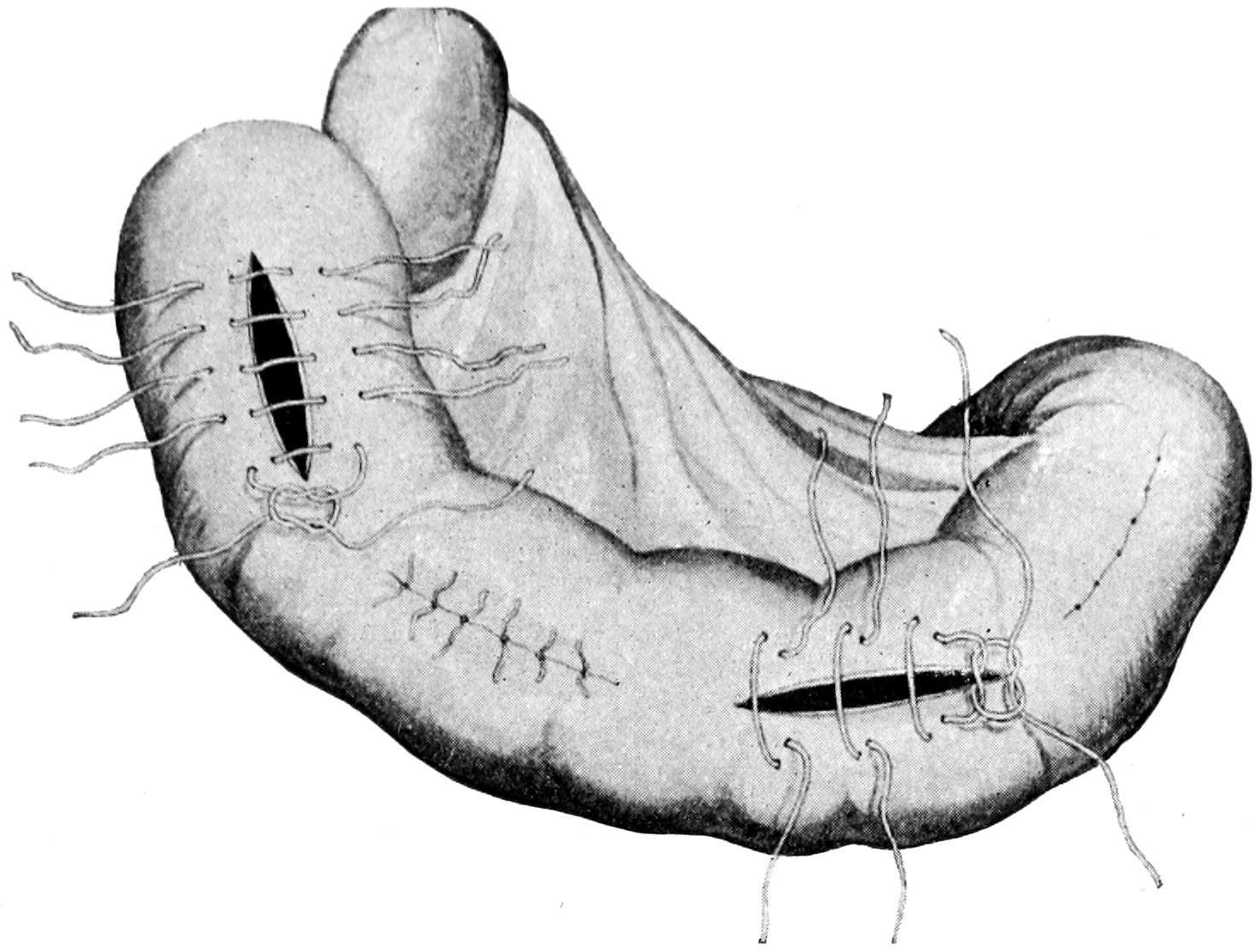

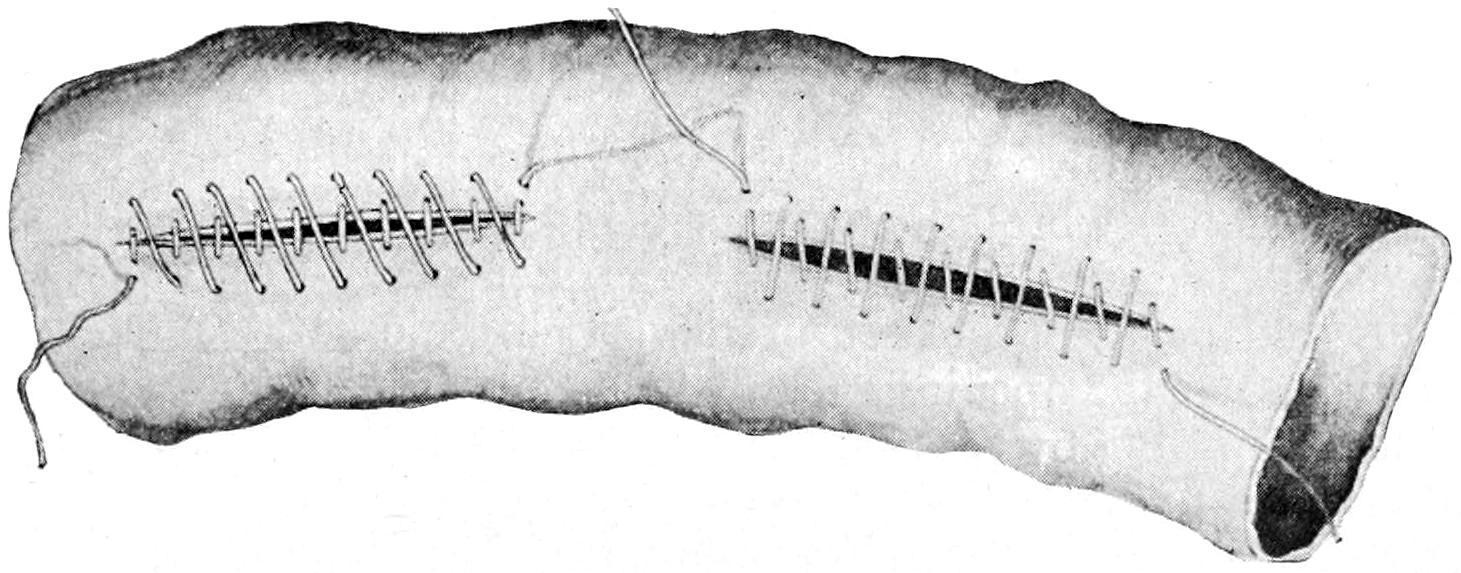

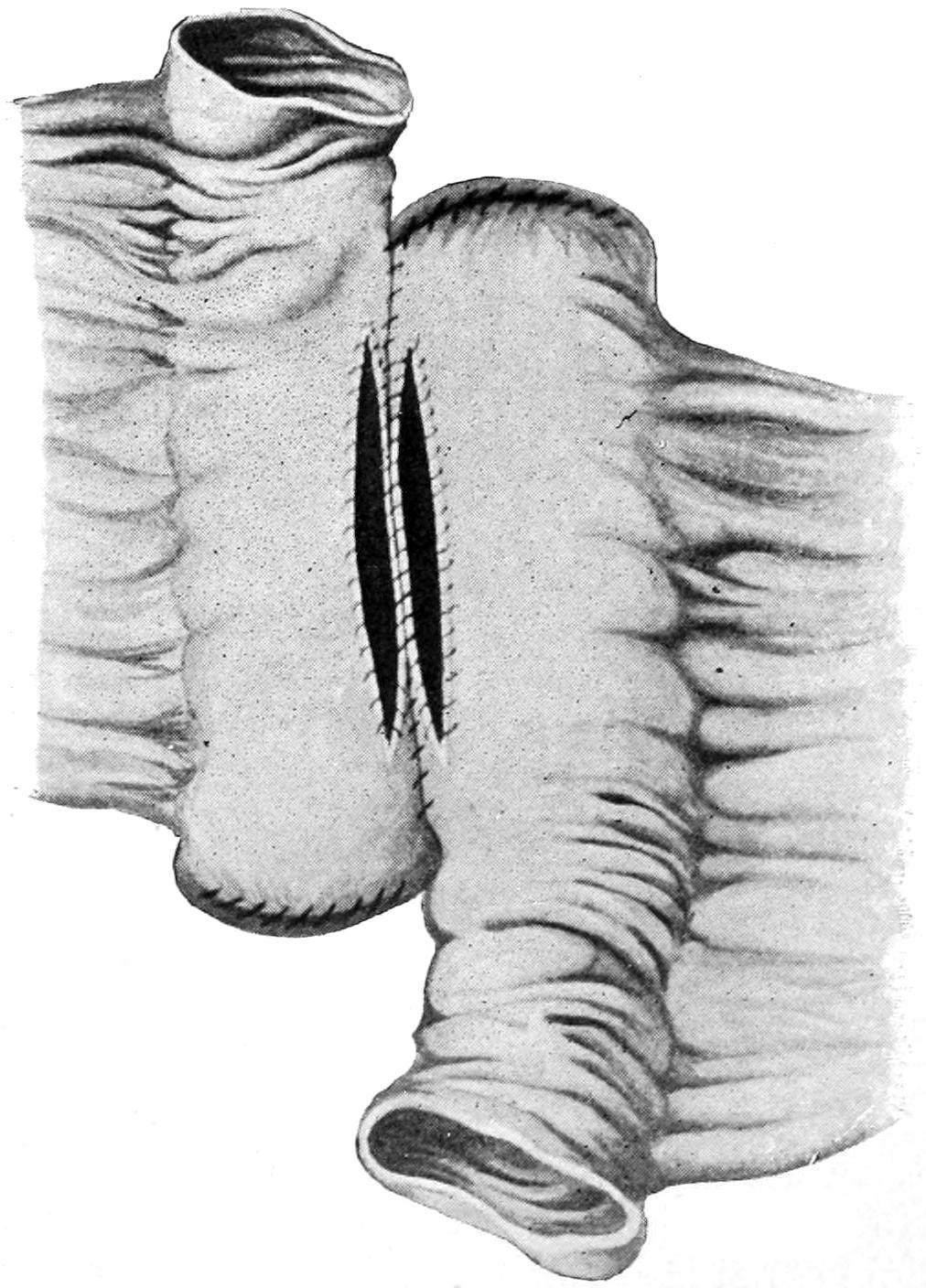

Intestinal suture is by no means a new or modern operation. It was spoken of by the ancient writers and was evidently practised in the middle ages by the “Four Masters” of the School of Salernum and their followers. But until it was reduced to a science by the French surgeons, Jobert and Lembert, during the first quarter of the past century, it was always a hazardous measure. Success with intestinal suture depends upon exact hemostasis of the edges to be united and their accurate approximation in layers (i.e., mucosa to mucosa and serous and muscular coat to its like). Save when haste compels, this accurate application is effected by two distinct suture rows, the first or deeper (of hardened gut) made to include the mucosa alone, the suture being usually continuous, but knotted at intervals, with stitches close together and drawn tightly to amply secure against leakage from the relatively large vessels of this membrane. It is better to apply this row by itself, as any suture drawn through the mucosa and out again through the serous coat is liable to contaminate the latter, it being much better to keep the contaminated row of sutures distinct. The first row having been applied and the surface carefully cleansed the operator may then coapt the balance of the annular wound by a continuous row of fine silk sutures, made to include the serous and muscular coats and to avoid the mucosa. The stomach and the colon are sufficiently thick to take a row of rather coarse sutures for this purpose, but most of the small intestine is so thin-walled that these need to be applied with caution as well as with dexterity.

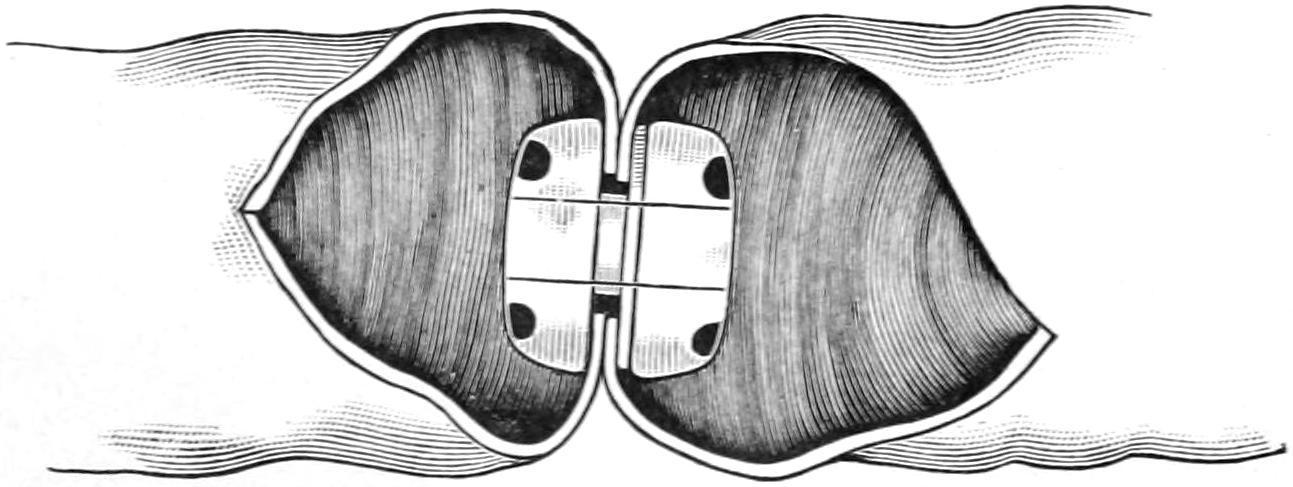

Every row of sutures should be so applied and directed that the lumen of the bowel be not reduced by its presence, it being a serious matter to greatly encroach upon the diameter of the bowel, since obstruction will thereby be favored and extra tension made upon the sutures (Figs. 564 and 565).

FIG. 564

Application of the interrupted Lembert suture. (Richardson.)

The continuous Lembert stitch. (Richardson.)

So many different forms of intestinal suture have been devised that it is useless to attempt here to describe them all.

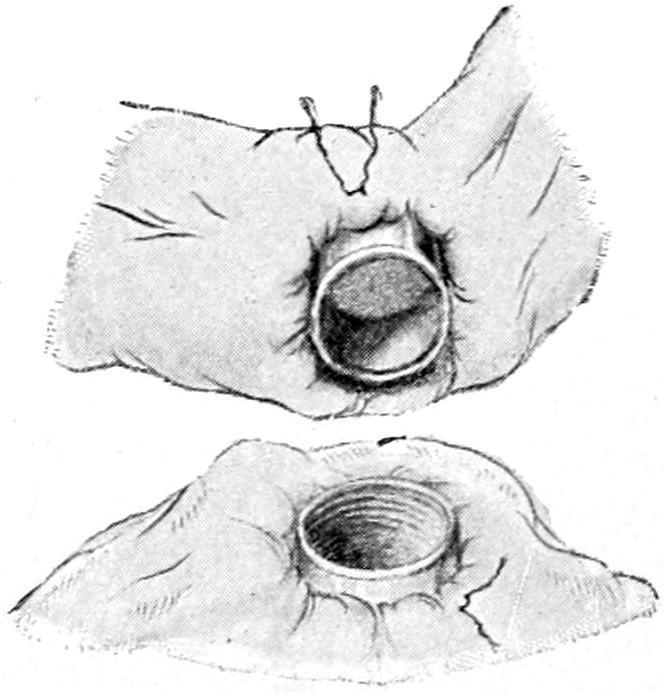

Any minute puncture of the bowel may be closed by purse-string suture. Any perforating wound should be not only first carefully cleansed, but also slightly enlarged, cutting away its more or less contused margins in order that fresh, viable tissue may be exposed. This is particularly true of gunshot wounds. Many of the operations now practised include inversion of the end of the bowel, a method illustrated in Fig. 566, showing a method equally applicable to burying the stump after removing the appendix, closing the end of a portion of the small or even the large bowel.

Most operators now use for the mucosa a carefully prepared and reliable chromicized catgut, the smaller size being preferable, with the ends cut short after the knots are tied. It is well also to use for intestinal suture needles which are round rather than made with cutting edges, as by the latter openings are made larger and vessels sometimes cut, this requiring the insertion of extra sutures for their securement. Whether the operator shall use curved or straight needles, and shall do the work with his fingers or depend upon various forms of needle holders, is purely a matter of choice and training. Success or failure depend not so much upon the needle holderasupon theholderoftheneedle, and his care and attention

to detail. In the presence of multiple lesions the procedure may have to be repeated to meet each indication.

Anastomotic Operations.

—For the general application of the principle of anastomosis to intestinal work the profession is largely indebted to Senn. The principle having been once recognized will never be rejected, but methods have already varied much from those first introduced, and will be improved by the substitution of simpler procedures for the more complex.

In general an anastomotic opening may be made between any distinct portions of the alimentary canal, and almost any one part may be thus, as it were, connected up with any other. Gastrojejunostomy has already been described. Only under compulsion does one thus connect the stomach with any other part of the alimentary canal. From the jejunum down to the rectum one may, however, effect attachments of this kind at any desired point. These operations are in the main done for one of the following purposes:

(a) In cases of obstruction of the bowel;

(b) For the purpose of exclusion of a certain length; or

(c) As a substitute for end-to-end reunion, after resection of a portion of the bowel.

The method of performance will depend not so much upon the nature of the difficulty requiring the operation as upon the condition of the patient, the equipment, and the operative skill of the surgeon. With a patient in extremely serious condition that method which may be most quickly performed is obviously the best. When time and method are under control, then that is best which can be most perfectly performed by the operator, or that which he is compelled to adopt, as when, for instance, he resorts to a suture method because he has no button at hand.

In order to simplify the subject as much as possible the following methods alone will be mentioned here:

The method by suture is essentially similar to that described as gastro-anastomosis, the surfaces which are to be brought together being properly placed, and approximated, first, by a row of silk suture, the openings being then made with excision of a strip of

mucosa, and the mucosa being next sutured with chromic gut, first on the further side, then on the near side of the opening, after which the serous membranes are accurately sutured around the opening by continuation of the first row of silk sutures. The actual opening made for the purpose should be at least an inch in length, preferably an inch and a half or more, while when the lower bowel is attached to the colon such an opening may well have a length of at least 2¹⁄₂ inches, for if successful it will be followed by a certain degree of cicatricial contraction and will never remain of its original size (Figs. 566, 567, 568 and 569). The suture may be combined with the elastic ligature, the method again being similar to that for uniting the jejunum with the stomach, already described. The rubber ligature used for the purpose is of the same size, and there is no difference to be made in the directions already given. The elastic ligature, however, can not be relied upon in emergency cases where it is necessary to effect a communication at once. It is serviceable only in instances where there is a leeway of at least three or four days. This method has for one of its advantages the fact that in its performance it is not necessary to clamp or secure the bowel by any instrument, simply to empty it for the moment with the fingers, it not being opened during the operation by anything save the needle puncture, which is promptly filled with the rubber. It does require, however, that the rubber used for the purpose shall be reliable and new, it being unfortunately the case that pure rubber which will last for a long time is seldom found in the market.

Entero-anastomosis of intestinal loops which have been resected and the bowel ends closed; the first row of sutures has been applied and the line of opening indicated. (Lejars.)

Suture of the distal edges of the mucosa.

FIG. 567

Insertion of the last (fourth) row of sutures. (Lejars.)

Resection of intestine with lateral anastomosis. Posterior suture inserted. The free ends of the bowel inverted and sutured. (Richardson.)

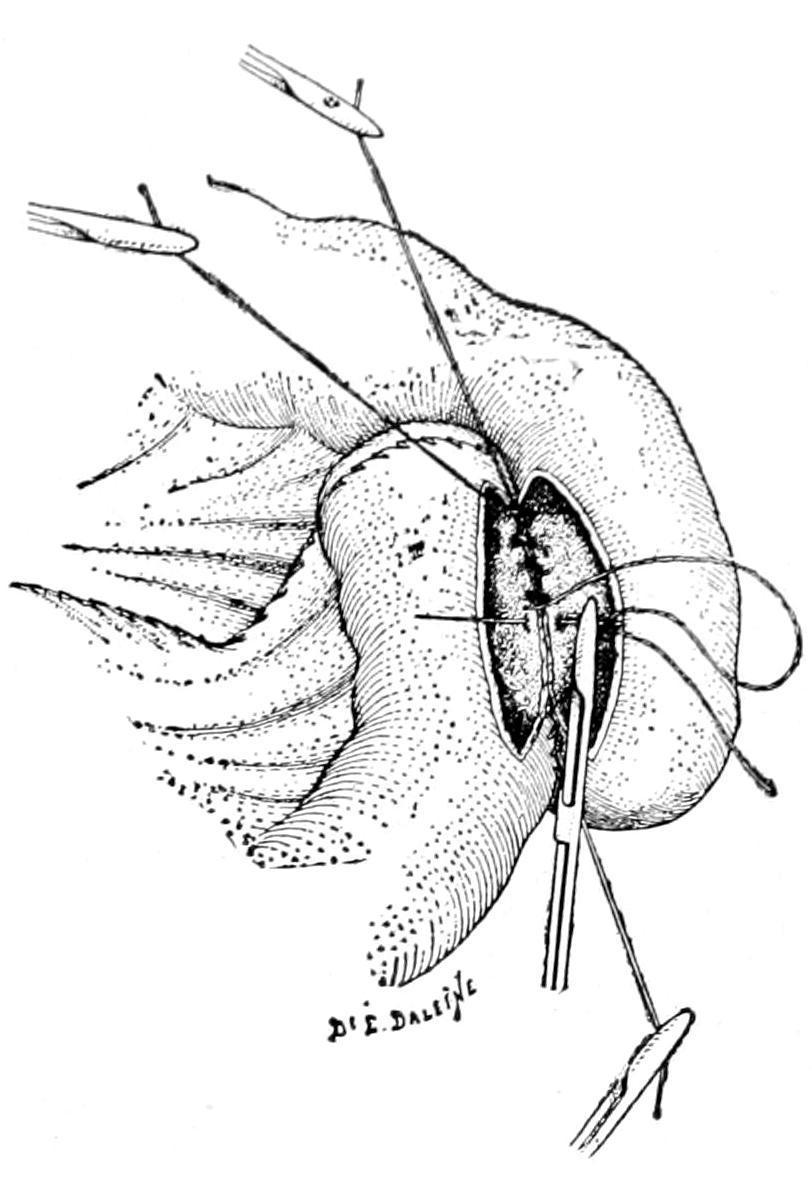

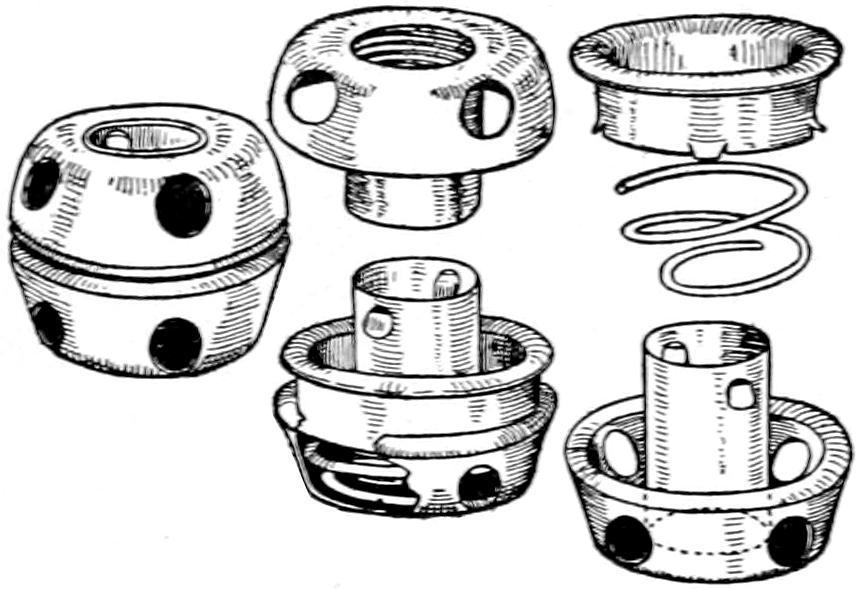

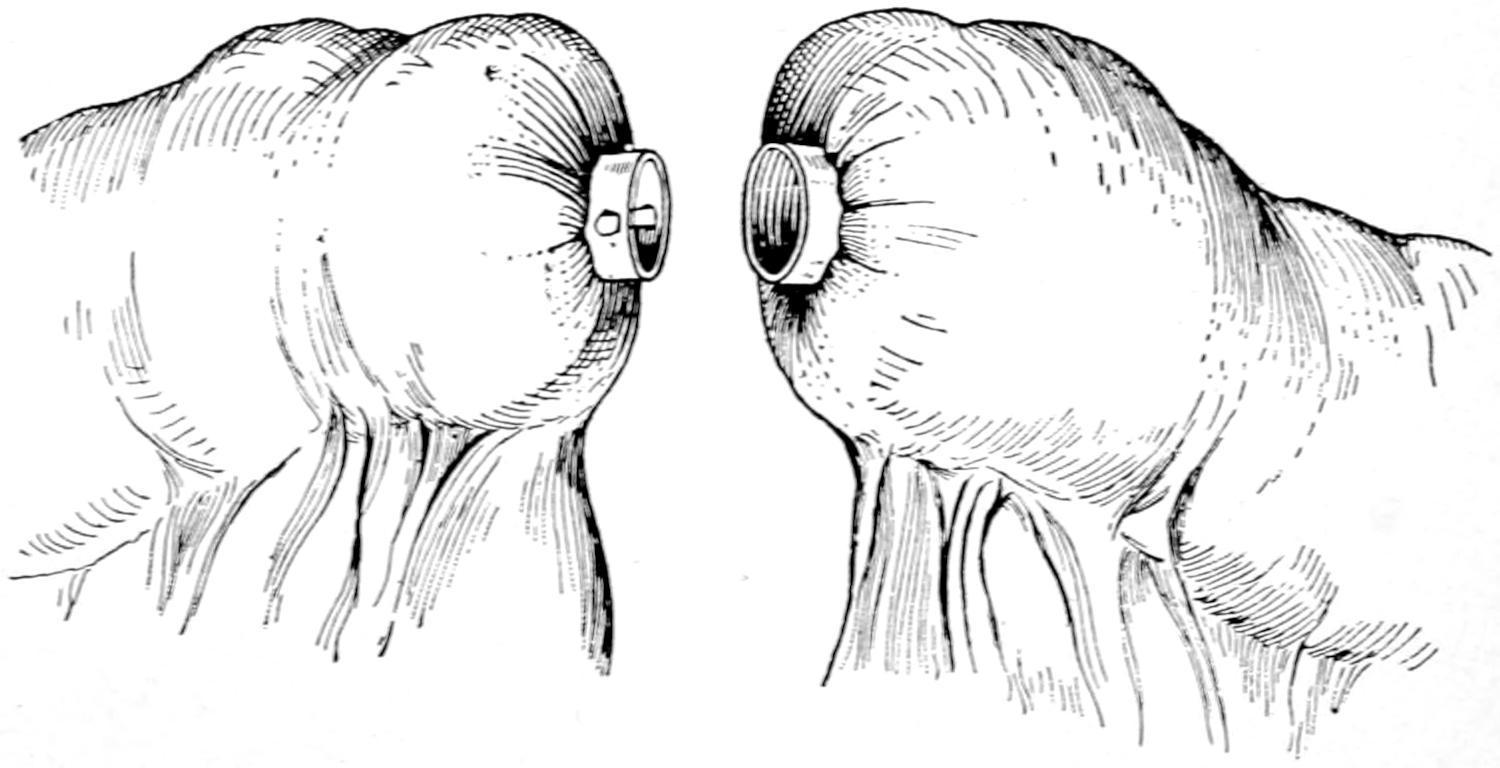

The button method depends for its success upon a mechanical device of Murphy, known everywhere as the “Murphy button,” or upon one of its modifications. Fig. 570 illustrates the component parts of this device, which is made in various sizes and, in fact, in various shapes for different purposes, though the circular forms suffice for practically all cases. In Fig. 572 it is seen in actual use, while Figs. 573 and 574 illustrate the method of its insertion and securement.

FIG. 569

The Murphy button.

FIG. 571

End-to-end union of intestine by means of the Murphy button: the two portions of the Murphy button, held in position by purse-string sutures, are ready to be pressed together. (Richardson.)

Union end to end with the Murphy button.

The underlying principle of the Murphy button is that each half can be inserted separately and that then, by pressing these halves together, an opening is at once afforded from one part of the bowel

FIG. 572

to the other. If the halves be pressed together with the proper degree of firmness they produce, first, adhesion between considerable areas around their circumference, followed in the course of a few days by a necrosis of the central portion, which sloughs because deprived of its circulation by the pressure. So soon as this separation or sloughing is complete the button drops into the intestinal canal, being completely loosened, and is now carried along by peristalsis and by the fecal current from above, its position shifting as would that of a scybalous mass or a fecal concretion, until it finally emerges from the intestinal tube, being passed from the anus. How soon it will thus appear will depend in large measure upon the point of the intestinal canal into which it is thus intruded. If this be high up it will be slower in appearing. If low down it may be expected sooner. While it usually appears within ten days or two weeks it may, however, be longer retained, and in one case of my own was not passed for three months, although the anastomosis was made with the ascending colon, into which it must have dropped.

Fig. 573 shows one of the halves held in the grasp of a forceps, being inserted into a small buttonhole opening just large enough to receive it, around which there has been passed a buttonhole or purse-string suture of silk. This portion once thus inserted should not be lost within the bowel, it being necessary to retain control of it by the forceps until its application to the other half. Both halves being inserted and brought opposite to each other, as in Fig. 574, the smaller is introduced into the larger, and they are then pressed together until the included serous surfaces are brought into contact, with sufficient pressure inflicted to bleach them, in order that their subsequent necrosis may be ensured. A circular row of sutures should now be placed around the surfaces thus applied, in order to more widely secure them in contact. The procedure being completed in this way, the parts are dropped back into the abdomen and the abdominal wound closed.

Introduction of one-half of a Murphy button. (Bergmann.)

Intestinal anastomosis with a Murphy button, showing the halves in position ready to be pushed together. (Bergmann.)

End-to-endreunioncan be accomplished by the same method, or the end of the small intestine may be applied to the side of the large, after a method which will be best understood by reference to Fig. 571, it being necessary here to draw the squarely cut end of the