Monotonic and cyclic simple shear response of gravel-sand mixtures Jonathan F. Hubler & Adda Athanasopoulos-Zekkos & Dimitrios Zekkos

https://ebookmass.com/product/monotonic-andcyclic-simple-shear-response-of-gravel-sandmixtures-jonathan-f-hubler-adda-athanasopouloszekkos-dimitrios-zekkos/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Mechanism of Failure Under Cyclic Simple Shear Strain Muniram Budhu

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-mechanism-of-failure-undercyclic-simple-shear-strain-muniram-budhu/

Elsevier Weekblad - Week 26 - 2022 Gebruiker

https://ebookmass.com/product/elsevier-weekbladweek-26-2022-gebruiker/

Jock Seeks Geek: The Holidates Series Book #26 Jill Brashear

https://ebookmass.com/product/jock-seeks-geek-the-holidatesseries-book-26-jill-brashear/

The New York Review of Books – N. 09, May 26 2022

Various Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-york-review-ofbooks-n-09-may-26-2022-various-authors/

Numerical Analysis of Soils in Simple Shear Devices

Muniram Budhu & Arul Britto

https://ebookmass.com/product/numerical-analysis-of-soils-insimple-shear-devices-muniram-budhu-arul-britto/

Calculate with Confidence, 8e (Oct 26, 2021)_(0323696953)_(Elsevier) 8th Edition Morris Rn

Bsn Ma Lnc

https://ebookmass.com/product/calculate-withconfidence-8e-oct-26-2021_0323696953_elsevier-8th-edition-morrisrn-bsn-ma-lnc/

Geomechanics of Sand Production and Sand Control Nobuo

Morita

https://ebookmass.com/product/geomechanics-of-sand-productionand-sand-control-nobuo-morita/

1

st International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainability in Music, Art, Textile and Fashion (ICESMATF 2023) January, 26-27 Madrid, Spain Exhibition

Book 1st Edition Tatiana Lissa

https://ebookmass.com/product/1-st-international-congress-andexhibition-on-sustainability-in-music-art-textile-and-fashionicesmatf-2023-january-26-27-madrid-spain-exhibition-book-1stedition-tatiana-lissa/

Cyclic Plasticity of Metals: Modeling Fundamentals and

Applications Hamid Jahed

https://ebookmass.com/product/cyclic-plasticity-of-metalsmodeling-fundamentals-and-applications-hamid-jahed/

SoilDynamicsandEarthquakeEngineering

journalhomepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soildyn

Monotonicandcyclicsimpleshearresponseofgravel-sandmixtures

JonathanF.Hublera,AddaAthanasopoulos-Zekkos b,⁎,DimitriosZekkosb

a Dept.ofCivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,VillanovaUniversity,800LancasterAve,Villanova,PA19085,UnitedStates b Dept.ofCivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofMichigan,2350HaywardSt.,AnnArbor,MI48109,UnitedStates

ARTICLEINFO

Keywords: CyclicSimpleShear GravellySoils ShearWaveVelocity Liquefaction GravelSandMixes

ABSTRACT

1.Introduction

Understandingtheresponseofgravellysoilsduringseismiceventsis criticaltorobustperformance-baseddesign.Historical(1964Alaska, USA;1975Haicheng,China;1976Tangsham,China;1983,BorahPeak Idaho,USA;1994Armenia;1995Kobe,Japan)aswellasrecent earthquakes(2008Wenchaun,China;2014Cephalonia,Greece;2016 Kaikoura,NewZealand)havedemonstratedthatgravellysoilsare susceptibletoliquefaction [1,13–15,24,30].However,theresponseof gravellysoilsbothduringandfollowingseismiceventsisnotwellunderstoodastherearefewwell-documentedcasehistoriesandlimited laboratorytestdata.Toproperlydesignandevaluategravellysoilsites forliquefactionsusceptibility,astudyofthefactorsthataffectgravelly soilshearresponseunderavarietyofconditionsisneeded.

Laboratorytestingofsoilsallowsfortheinvestigationofparameters thataffectshearresponseundercontrolledconditionsandparametric evaluationscanbeperformedforloadingscenarioswhere fieldcasehistorydataissparse.Severalstudieshaveevaluatedthemonotonic andcyclicshearresponseofgravellysoils.HoltzandGibbs [17] performedconsolidateddrainedtriaxialtestsonmixturesofsandand gravelwithdifferentpercentgravelcontentsandfoundthattheshear strengthofgravellysoilsincreasedwithincreasingthegravelcontent upto50–60%.Theauthorsalsofoundthatincreasingparticleangularityincreasedtheshearstrengthofthegravellysoil.Rashidian [25]

⁎ Correspondingauthor.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.07.016

Understandingthefactorsthataffectthemonotonicandcyclicresponseofgravellysoilsduringearthquake eventsiscriticaltoinfrastructuredesign.Inthisstudyalarge-sizeCyclicSimpleShear(CSS)devicewasutilized toperformmonotonicandcyclicsheartestsonmixturesofeithersubrounded9mmPeaGravelorangular8mm CrushedLimestone(CLS8)withsubroundedOttawaC109sand.Testswereperformedinconstantvolume conditionsandshearwavevelocitywasmeasuredforeachspecimen.MonotonicandcyclictestresultsatDr =47%showthatthereisanoptimummixturepercentagethatresultsinthegreatestshearstrengthandresistancetoliquefaction(40%SandforPeaGravelMixturesand60%SandforCLS8Mixtures).Theeffectsof particleangularity,cyclicstressratio,andinitialverticalstressonmonotonicandcyclicresponseoflooseand densegravelmixtureswereinvestigatedandarepresented.Comparisonoftheresultsfromthecyclicsimple sheartestswithexistingliquefactiontriggeringchartssuggeststheneedforimprovedchartsforgravellysoil liquefactionevaluation.

performedastudyofsandandgravelmixturespreparedveryloose (relativedensitylessthanapproximately20%)andshowedthatduring undrainedmonotonicloadingspecimenswithupto90%gravelcontent displayedacontractivebehavior.ChangandPhantachang [7] performedconstantloadmonotonicsimplesheartestsonangularcrushed aggregatesmixedwitheitherpoorly-gradedorwell-gradedsandin differentpercentages.Theauthorsconcludedthatgravellysoilscanbe categorizedaseithersand-like,gravel-like,orin-transitionbasedon gravelcontent.Inboththewell-gradedandpoorly-gradedmixtures, increasinggravelcontentreducedshearresistance.Initialverticalstress wasshownnottohaveaneffectonthenormalizedshearstressratio ′ τσ( / ) v ,whichrangedfrom0.40to0.60forthedrainedsimpleshear tests.

Thecyclicresponseofgravellysoilshasalsobeeninvestigatedinthe laboratory.Wongetal. [29] studiedtheliquefactionresponseof gravellysoilsusinglarge-scaletriaxialtestsandconcludedthatuniform gravelsexhibitslightlyhigherresistancetoliquefactionthanwellgradedgravellysoils,butthatmembranecomplianceaffectedthe measuredresponse.Banerjeeetal. [3] performedcyclictriaxialtestson densegravellysoilsfromOrovilledamandfoundthatthedensegravel exhibitedmanysimilaritiestodensesandundercyclicloading.Specimenpreparationtechniquewasfoundtohavelittleeffectonshear response.EvansandSeed [9] testedWatsonvillegravelintriaxialdevices,andfoundthatthecyclicstressratio(CSR)forliquefactionin10

E-mailaddresses: jonathan.hubler@villanova.edu (J.F.Hubler), addazekk@umich.edu (A.Athanasopoulos-Zekkos), zekkos@geoengineer.org (D.Zekkos).

Received5October2017;Receivedinrevisedform11June2018;Accepted14July2018

Availableonline06September2018

0267-7261/©2018ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved. T

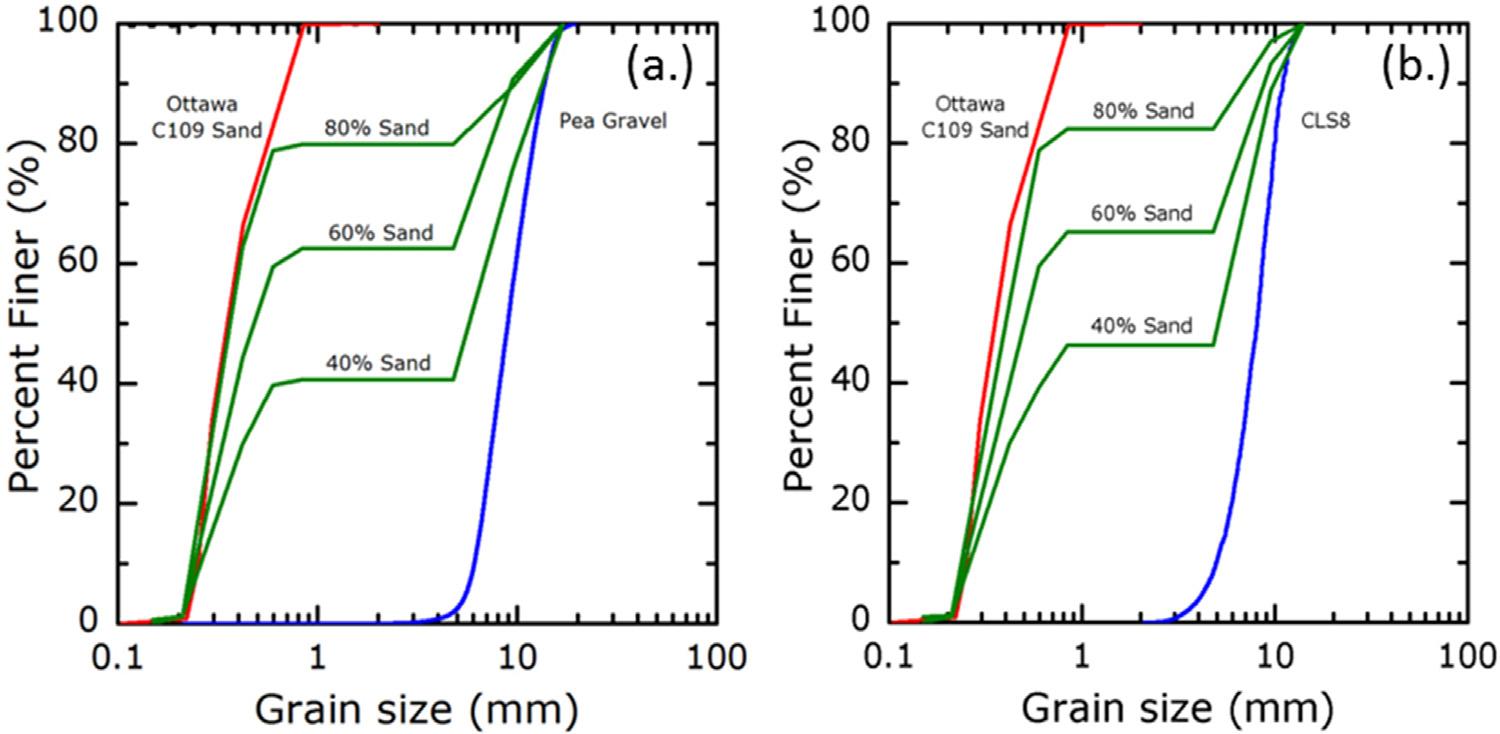

Fig.1. GrainSizeDistributionsfor(a)PeaGravelmixturesand(b)CLS8mixtures.

cycleswasonly0.143.Evansetal. [10] showedthatmembranecomplianceinthetriaxialapparatuscanoverestimateliquefactionresistancebyasmuchas40%.Hatanakaetal. [16] testedMasado fillthat liquefiedduringthe1995Kobeearthquakeandfoundthatdespiteits highdrydensityandgravelcontent,thegravel fillliquefiedatCSRs from0.15to0.23whichissimilartoToyourasandtestedatarelative densityof70%.EvansandZhou [11] performedundrainedtriaxialtests ofgravel-sandmixtureswithgravelcontentsrangingfrom0%to60% andfoundthattheinclusionofgravelparticlesincreasedtheliquefactionresistance.Kokushoetal. [22] evaluatedtheundrainedcyclicand post-cyclicshearstrengthofgranularsoilswithdifferentparticlegradationsutilizingatriaxialtestapparatus.Theauthorsfoundthatthe liquefactionstrengthofwell-gradedgranularsoilsissimilartopoorlygradedsandswithidenticalrelativedensities.Changetal. [6] performedcyclicsimplesheartestsofgravel-sandmixtureswithaD50 valueforthegravelsof5.3mm.Theauthorsfoundthatthetransition fromsand-liketogravel-likeresponsewasinthe50–70%gravelcontent range.Theauthorsmeasuredshearwavevelocity(VS)ofeachspecimen andfoundthataddinggraveltosand-likespecimensincreasedVS.A comparisonofcyclicdatawithAndrusandStokoe [2] showedthatthe AndrusandStokoe [2] curve,whichisbasedon field-liquefactioncase historydata,shouldbeshiftedtolowervaluesofVS1.Insummary, whilelaboratorytestingofgravellysoilshasbeenundertaken,most testinghasbeenperformedusingtriaxialdevices(whichareproneto membranecomplianceissues)andtheinfluenceofseveralparameters (particleangularity,density,verticalstress)stillremainstobeinvestigated.Studyoftheseparametersaidsintheunderstandingof gravellysoilresponsethathasbeenobservedinthelaboratory(includinguniformgraveltestsin [18])andinthe field(withlimiteddata) duringearthquakeevents.

Alarge-sizeCyclicSimpleShear(CSS)devicewasutilizedtoperformmonotonicandcyclicsheartestsonmixturesofeithersubrounded 9mmPeaGravelorangular8mmCrushedLimestone(CLS8)with subroundedOttawaC109sand.Testswereperformedatconstantvolumeconditionsandshearwavevelocityofeachspecimenwasmeasuredforcomparisonbetweentestdataandexistingrelationshipsfor liquefactionevaluation [2,21,5].Thispaperpresentssomeofthe first cyclicsimplesheardataforgravel-sandmixtures,andprovidesan evaluationofparametersthataffecttheshearresponseofgravellysoils undermonotonicandcyclicloadingconditions.

2.Testmaterialsandmethods

2.1.Testequipment

Alarge-sizeCyclicSimpleShear(CSS)devicedevelopedatthe

UniversityofMichiganincollaborationwithalaboratoryequipment manufacturerwasutilizedtoevaluatethemonotonicandcyclicresponseofgravellysoils.TheCSSspecimenis307.5mmindiameterand thespecimenheightcanrangefromapproximately100mmto120mm. ThedevelopmentandvalidationoftheCSSdeviceispresentedindetail inZekkosetal. [31].Inadditiontomonotonicandcyclic,stressor straincontrolled,constantloadorconstantvolumesimplesheartesting, VS measurementsusingbenderelementsandminiatureaccelerometers canbeconducted.Inthisresearch,accelerometerswereutilizedfor shearwavevelocitymeasurementssincetheywerefoundtoyield identicalVS valueswithbenderelements,butthelatterweregetting damagedoftenbythegravellysoils.Detailsoftheaccelerometersetup andmeasurementisgiveninHubler [20] andZekkosetal. [31].

2.2.Testmaterials

Thematerialstestedinthisstudyincludedauniformsand(Ottawa C109sand)andtwouniformgravels(9mmPeaGraveland8mm CrushedLimestone(CLS8)).Theseuniformly-gradedmaterialswere extensivelytested(andtheresultsarepresentedin [18])before studyinggravel-sandmixturesofPeaGravelwithOttawaC109sand andCLS8withOttawaC109sand.Gravel-sandmixtureswereprepared atmixturepercentages(byweight)of80%Sand/20%Gravel,60% Sand/40%Gravel,and40%Sand/60%Gravel.Thesemixtureswillbe referencedbytheirsandpercentagethroughoutthispaper.Twodifferenttypesofgravelsofsimilarsizewereusedfortestingsothateffects ofparticleangularitycouldbeassessed.Thegrainsizedistributionsof thePeaGravelmixturesaregivenin Fig.1a,whilethegrainsizedistributionsoftheCLS8mixturesaregivenin Fig.1b.The80%Sand, 60%Sand,and40%Sandspecimenshavegap-gradeddistributionsfor thePeaGravelmixturesandCLS8mixtures.Therelevantpropertiesof thePeaGravelandOttawaC109sandmixturesaregivenin Table1, andthepropertiesoftheCLS8andOttawaC109sandmixturesare givenin Table2.Theevaluationofthemaximumdensityofgap-graded

Table1

PropertiesofPeaGravel/OttawaC109sandmixtures.

GS 2.65 2.652.652.652.65

γd,max (kg/m3)17512223203218701733

γd,min (kg/m3)13572068184216601512

emax 0.9530.4190.4550.5860.752

emin 0.5130.3130.3350.4130.529

gravellysoilmixturescanbechallenging,andthereforethemethod describedinHubleretal. [19] wasusedtoassessthemaximumdensity. Thismethodresultedinexperimentalvaluesofmaximumdensitythat weresimilartothosepredictedbythealphamethod [12].Minimum densitywasevaluatedbyplacinggravel-sandmixturesaslooseas possiblewithafunnelatzerodropheight. Fig.2 showstheminimum andmaximumvoidratiosasafunctionofpercentsandforPeaGravel andCLS8mixtures.Asshowninthe figure,therangeofpossiblevoid ratiosbecomessmallerforthemixturesandissmallestinthe40–60% rangecomparedtotheuniformmaterials.

2.3.Testprocedure

Thelarge-sizeCSSdevicewasutilizedtoperformaseriesof92 monotonicandcyclictestsonOttawaC109sand,PeaGravel,CLS8,and mixturesofOttawaC109sandwitheitherPeaGravelorCLS8. Specimenswerepreparedattwotargetrelativedensities(Dr)foreach material:Dr =47%+/ 3%andDr =87%+/ 5%.TheseDr values arebasedontheglobalvoidratioofthespecimen,includingboth gravelandsandskeletons.Thisrelativedensitycanbeconsideredthe globalrelativedensity,asitaccountsfortheentiremixtureofsandand gravelinthespecimen.EvansandZhou [11] referredtothisoverall relativedensityasthecompositerelativedensityofthespecimen.This relativedensitycanalsobeconvertedtoaglobalvoidratiovaluewhen thespecificgravityofthemixingmaterialsisknown.Thevoidratiosof thesandskeletonandgravelskeletoncanalsobedefinedusingthe intergrainstateframework [6].Asimilarframeworkhasbeenusedfor sandandsiltmixtures [27],wheretheintergranularandinterfinevoid ratioweredefinedforsandandsiltmixtures.Althoughitisrecognized thatthestress-strainresponseofsand-siltmixturesandgravelmixtures iscomplex,thealternativeskeletonvoidratiosofferaninteresting approachininterpretingmaterialresponseandthereforewereevaluatedinthisstudy.Intheinterpretationofgravellysoils,thesand skeletonvoidratioisfoundtobecriticalwhenthegravelisnotcontributingtotheforcechainandthegravelskeletonvoidratioiscritical

whenthesandis fillingthevoidspacebetweengravelparticlesandnot contributingtotheforcechain.Thesandskeletonvoidratiocanbe definedas:

= e e GC 1 sk (1) whereeistheglobalvoidratioandGCisthegravelcontentinpercent. Thegravelskeletonvoidratiocanbedefinedas:

= +− e eGC GC (1) gk (2)

Specimenswerepreparedattheloosedrystatebyplacingthe gravel-sandmixtureswithafunnelinliftsofapproximately25mm.The sandandgravelwas firstmixedtogetherbeforeplacementwiththe funneltoensureuniformparticledistributionandminimizeparticle segregation.Specimenswerepreparedatthedensedrystatebydroppinga5-kgweightwithacirculardiameterof150mmfromaheightof 50–75mm.Anaverageof25dropsperlayerin3layers(approximately 35–40mmlayerheight)wasused.Thissmalldropheightwasusedto minimizeparticledamageduringspecimenpreparationandagreater numberofdropswasusedforsuccessivelayerstoensurespecimen uniformity.

Specimensof100%Sand,80%Sand,60%Sand,40%Sand,and0% Sand(or100%Gravel)weretestedatDr =47%andDr =87%atinitial verticalstresses ′ σ( ) v0 of100,200,and400kPa.Specimenswere first subjectedtothedesiredverticalstress ′ σv0 .VS wasmeasuredfollowing verticalloadapplicationandbeforeshearing(eithermonotonicor cyclic)usingaccelerometers.Monotonictestswerestrain-controlled andshearedatarateof0.3%perminute,whichenabledprecisecontrol ofconstantvolumeconditionsandwassimilartootherstrainratesused insimplesheartestingofcohesionlesssoils [26].Cyclictestswere stress-controlledwithdifferentcyclicstressratios(CSRs)rangingfrom 0.04to0.14andaloadingfrequencyof0.33Hz.Monotonicandcyclic testswereperformedatconstantvolumeconditions,whichhavebeen showntoaccuratelyrepresenttrulyundrainedconditionsinsimple sheartesting [8].Inconstantvolumesimplesheartesting,themeasured changeintheverticalstressisassumedtobeequaltotheporepressures thatwoulddevelopinatrulyundrainedtest.ConstantvolumeconditionsaremaintainedintheCSSdevicebyactivecontrolthrougha feedbackloop,whichsuppressesmovementoftheverticalcapandallowsforaccuratemeasurementofthechangeinverticalstress.

3.Testresults

3.1.Shearwavevelocity

Shearwavevelocitywasmeasuredfollowingverticalload

Fig.2. Minimumandmaximumvoidratiofor(a)Peagravelmixtureand(b)CLS8mixtures.

Table3

Fig.3. Shearwavevelocitymeasurementsfor(a)PeaGravelmixturesand(b)CLS8mixtures.

ShearwavevelocityparametersforPeaGravel/OttawaC109sandmixturesat Dr =47%.

ParameterOttawaC109sand80%sand60%sand40%sandPeagravel

α (m/s)189196199204188

β 0.260.230.230.230.25

Table4

ShearwavevelocityparametersforCLS8/OttawaC109sandmixturesatDr =47%.

ParameterOttawaC109 sand 80%sand60%sand40%sand8mmcrushed limestone

α (m/s)189206215201210

β 0.260.230.270.250.23

applicationandcompressionofthegravel-sandmixturespecimensand resultsarepresentedforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47%in Fig.3aand CLS8mixturesatDr =47%in Fig.3b.ForbothPeaGravelandCLS8 mixtures,VS increasedwithincreasing ′ σv0 from100to400kPa. Fig.3a showsthatthemixingofPeaGravelwithOttawaC109sanddoesnot significantlyaffecttheVS.ThisisduetothesimilarityinVS ofthe uniformPeaGravelandOttawaC109sandmaterialsat ′ σv0 =100kPa (PeaGravelVS =189m/s,OttawaC109sandVS =191m/s).The mixturewiththehighestVS valueswasthe40%Sandspecimen. Fig.3b showsthatthemixingofCLS8withOttawaC109sandresultsin changesinVS comparedtotheuniformCLS8specimens.Thisisdueto thedifferencesinVS at ′ σv0 =100kPafortheuniformcrushedlimestone CLS8gravel(VS=212m/s)andOttawaC109sand(Vs=191m/s).The mixturewiththehighestVS wasthe60%Sandspecimenfollowedby the100%Gravelspecimen.PowerfunctionsoftheforminEq. (3) were fittothedataandvaluesdeterminedforthe α and β parametersare presentedin Table3 forPeaGravelmixturesand Table4 forCLS8 mixtures.TheVS relationshipwithverticalstresscanbedescribedby: ⎟

atm

(3)

where α (expressingVS inm/sat1atm(101.3kPa))and β are fitting parametersdeterminedfromlaboratorytesting.The α valueforthePea Gravelmixtureswasthehighestforthe40%Sandspecimen,whilethe highest α valuefortheCLS8mixtureswasforthe60%Sandspecimen. The β valuesforthePeaGravelmixturesrangedfrom0.23to0.26,with

lowervaluesof0.23forthe80%Sand,60%Sand,and40%Sand specimens.The β valuesfortheCLS8mixturesrangedfrom0.23to 0.27,withthe60%Sandspecimenhavingthehighest β valueof0.27. The β valuesevaluatedinthisstudyarereasonableforthesoilstested [23].VS1,whichwillbeusedforanalysisandcomparisonofdatainthis study,wascalculatedusingthefollowingequation:

wherePa isatmosphericpressure(101.3kPa)and ′ σv istheverticaleffectivestress.

3.2.Monotonicconstantvolumesimpleshear

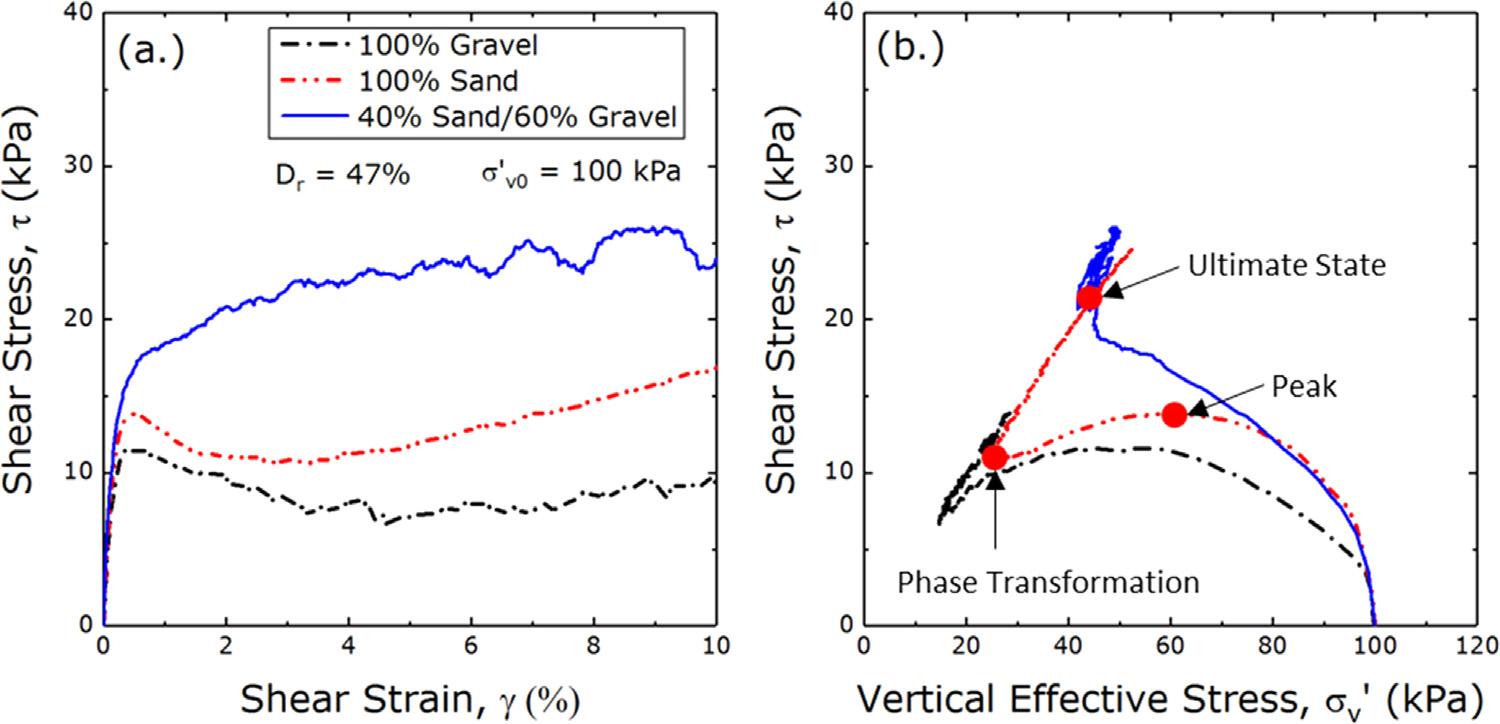

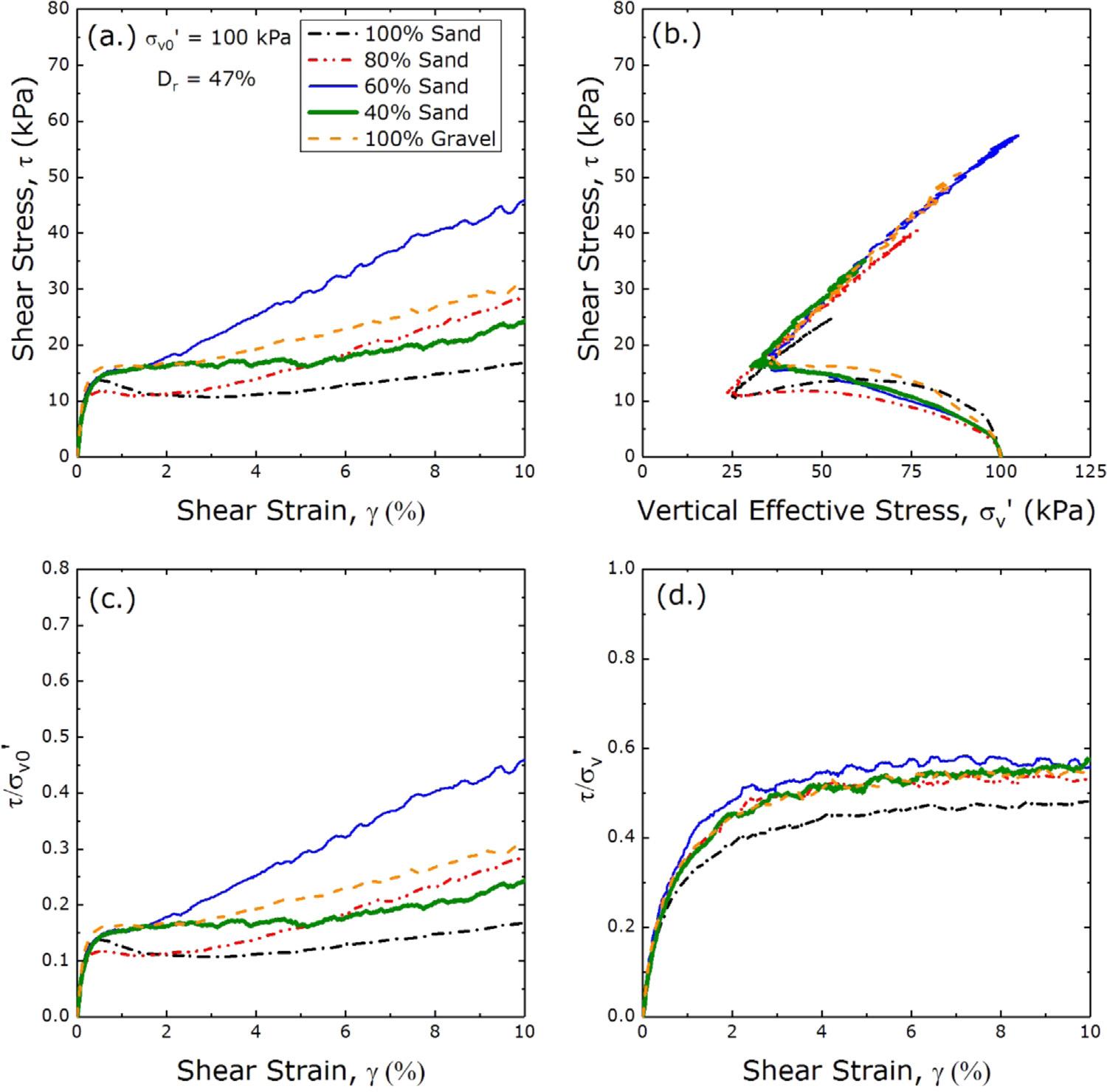

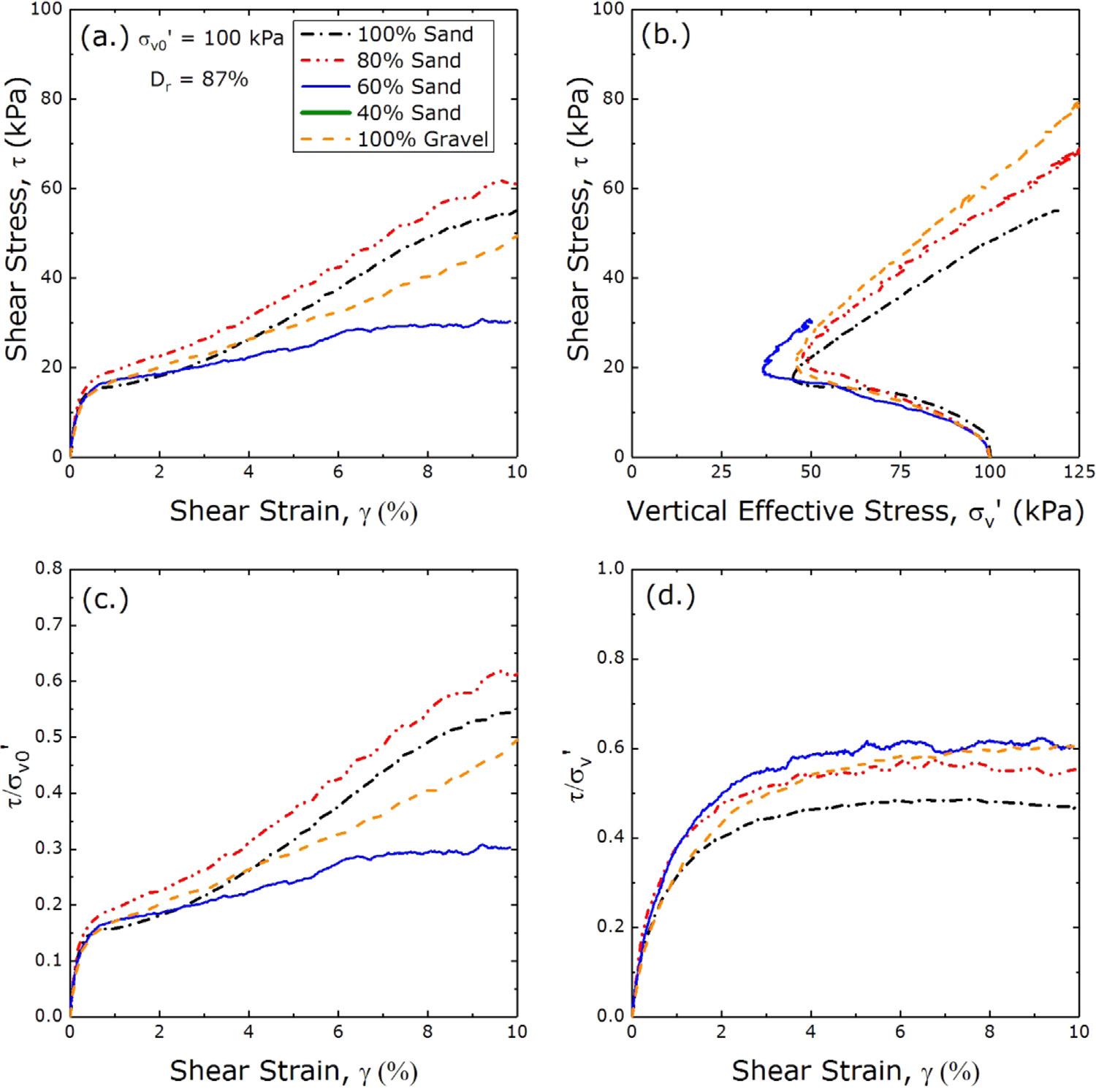

MonotonicsheartestswereperformedonmixturesofPeaGravel withOttawaC109sandandCLS8withOttawaC109sand.Specific parameters,includingmixturepercentage,initialverticalstress,and relativedensity,weretargetedtoprovideinsightintotheireffecton shearresponse.Datawasinterpretedbyevaluatingthepeak,phase transformation(PT),andultimatestate(US)shearstrengths. Fig.4 showsdatafor100%Sand,40%Sand,and100%PeaGravelforshear stress-shearstrainresponseandcorrespondingstresspaths.Thepeak, PT,andUSpointsareidentifiedin Fig.4bforthe100%Sandspecimen. Thepeakpointcorrespondstothepeakshearstrength,whichiseasily identifiedforthe100%Sandspecimen.ThePTpointisthepointof maximumporepressuregeneration(i.e.minimumverticaleffective stress),whiletheUSpointcorrespondstothelineofmaximumobliquitythatisattainedasthespecimenisshearedtogreatershearstrain. PeaGravelandOttawaC109sandmixturesweretestedatmixture percentagesof100%Sand,80%Sand,60%Sand,40%Sand,and100% Gravel. Fig.5 presentsmonotonicsheartestresultsforspecimensatDr =47%and ′ σv0 =100kPa. Fig.6 presentsthemonotonicresultsfor specimensatDr =87%and ′ σv0 =100kPa.Inthese figuresthefollowing plotsarepresented:(a)stress-strainresponse,(b)stresspathresponse, (c) ′ τσ / v0 versusshearstrain,and(d) ′ τσ / v versusshearstrain.Ofparticularinterestisthechangeinstress-strainresponseofthegravel-sand mixturescomparedtotheuniformgravelorsand.FortheDr =47% specimens,theuniformsandandgravelexhibitapeakonthestressstraincurve(Fig.5a),followedbystrainsofteningtosomeminimum shearresistancevalueandthenexhibitastrainhardeningresponse. Thistrendbecomeslesspronouncedforthegravel-sandmixturesandat 40%Sand(theoptimummixture)thespecimendoesnotexhibitany softening,butonlystrainhardeningresponse.FortheDr =87%specimens,strainsofteningisnotobserved.Theuniformmaterialshave

Fig.4. ComparisonofPeaGravel,Sand,andPeaGravel-Sandmixturemonotonic(a)Shearstress-shearstrainresponseand(b)Shearstress-verticaleffectivestress response.

lowerpeakshearstrengths,butpost-peakstrainhardeningisgreater thaninthegravel-sandmixtures.Theeffectofmixturepercentageis morepronouncedfortheDr =47%specimensthantheDr =87% specimens.Forexample,Dr =47%specimensatinitialverticalstressof 100kPashowasignificantincreaseinshearstrengthforamixture percentageof40%Sand,asshownin Fig.5a.Conversely,fortheDr =87%specimens,theshearstrengthinthepeakrange(approximately 1%shearstrain)ismoretightlygroupedwiththe60%Sandand40%

Sanddisplayingthegreatestpeakstrength.Asshearstrainincreasesto 10%theshearresistancevariationincreases,withthe80%Sandspecimendisplayingthegreatestshearstrength.FortheDr =47%specimens,the40%Sandmixtureisconsideredtheoptimummixturesinceit hasthegreatestshearresistance. Fig.5bshowstheeffectofmixture percentageonstresspathresponse.Asthemixturepercentageincreases totheoptimum,theresponsechangestofullystrainhardening,withno post-peaksoftening.

Fig.5. MonotonicsimpleshearresultsforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47%and ′ σv0 =100kPafor(a)Shearstress-shearstrainresponse,(b)Stresspathresponse,(c) ′ τσ / v0 versusshearstrain,and(d) ′ τσ / v versusshearstrain.

Fig.6. MonotonicsimpleshearresultsforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =87%and ′ σv0 =100kPafor(a)Stress-strainresponse,(b)Stresspathresponse,(c) ′ τσ / v0 versus strain,and(d) ′ τσ / v versusstrain.

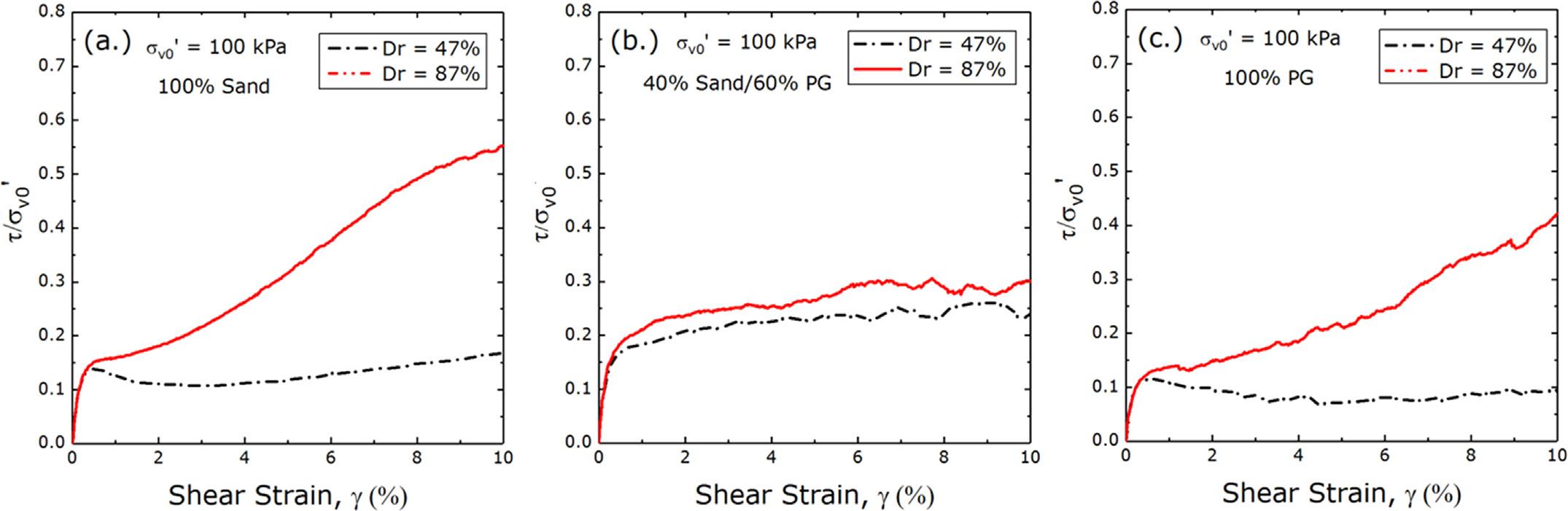

Tobetterillustratetheeffectsofrelativedensity,100%Sand,40% Sand(theoptimummixture),and100%Gravel ′ τσ / v0 versusshearstrain responseatDr =47%andDr =87%wereplottedin Fig.7.This figure showsthatthedifferencein ′ τσ / v0 versusshearstrainresponseforlooser anddenserspecimensisgreaterfortheuniformspecimensof100% Sandand100%Gravel.Asthemixturereachestheoptimumpercentage (i.e.40%SandforPeaGravelmixtures),theeffectofrelativedensityis reduced.Thisresponsecanbeattributedtothesmallvariationofvoid ratiosofthespecimensattheoptimummixturepercentageintheloose

anddensestates.TheDr =47%optimummixturespecimenhasa globalvoidratioof0.334,whiletheDr =87%optimummixturespecimenhasaglobalvoidratioof0.294,whichisgenerallyanarrower rangethanthatoftheotherspecimens.

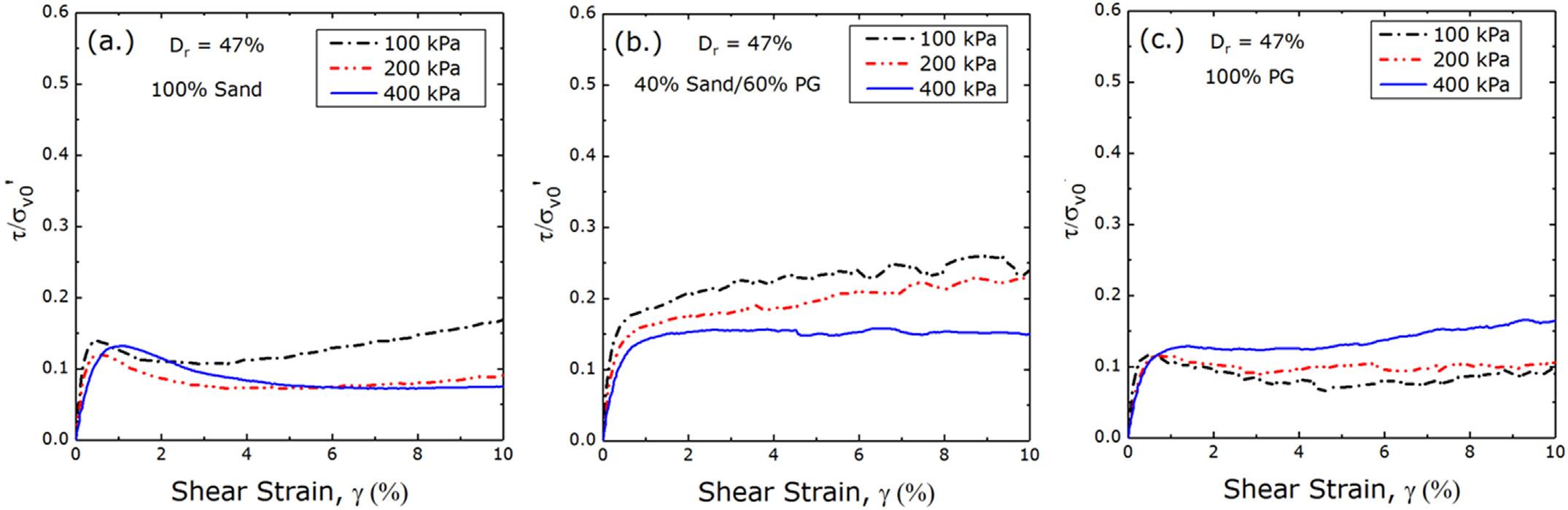

TheeffectofinitialverticalstressonDr =47%specimenswasinvestigatedbyplotting ′ τσ / v0 versusshearstrainasshownin Fig.8 for 100%Sand,40%Sand,and100%Gravel. Fig.8ashowsthatasinitial verticalstressincreases,the100%Sandspecimensdisplaylessstrain hardeningresponseinthepost-peakrange(i.e.thespecimendilatesless

Fig.7. ComparisonofEffectofRelativeDensityfor(a)100%Sand,(b)40%Sand/60%PG,and(c)100%PG.

Fig.8. Comparisonofeffectofinitialverticalstressfor(a)100%sand,(b)40%sand/60%PG,and(c)100%PG.

post-peak).Adifferenttrendwasobservedforthe100%Gravelspecimensin Fig.8c,withthe400kPaspecimenattaininggreater ′ τσ / v0 valuespost-peak. Fig.8bshowssignificantdifferencesinboththepeak andpost-peakrangesforthe40%Sandmixture,with ′ τσ / v0 valuesdecreasingwithincreasingverticalstress.These figuresalsoshowthatthe uniformsandandgravelspecimenssoftenpost-peakandthenstrain harden,buttheoptimummixturespecimensdonotsoftenat100or 200kPaanddonothardenat400kPa.

ThemonotonicresponseofCLS8andOttawaC109sandmixtures

wasalsoinvestigatedformixturepercentagesof100%Sand,80%Sand, 60%Sand,40%Sand,and100%Gravel.Limitedtestingof40%Sand specimenswascompletedsinceparticlesegregationwasobservedin thesespecimensbecausetherewasnotenoughsandto fillinthegravel voidspace. Fig.9 showsthemonotonicshearresultsforspecimensatDr =47%and ′ σv0 =100kPa. Fig.9ashowsthatthe60%Sandspecimen exhibitsthegreatestpost-peakshearstrengthandisconsideredthe optimummixturepercentage.The60%Sand,40%Sand,and100% Gravelspecimenshadverysimilarpeakshearstrengthsandallexhibit

Fig.9. MonotonicsimpleshearresultsforCLS8mixturesatDr =47%and ′ σv0 =100kPafor(a)Stress-strainresponse,(b)Stresspathresponse,(c) ′ τσ / v0 versusstrain, and(d) ′ τσ / v versusstrain.

Fig.10. MonotonicSimpleShearresultsforCLS8mixturesatDr =87%and ′ σv0 =100kPafor(a)Stress-strainresponse,(b)Stresspathresponse,(c) ′ τσ / v0 versus strain,and(d) ′ τσ / v versusstrain.

strainhardeningresponse,whichsuggeststhatthegravelportionofthe specimeniscontrollingresponseoncethegravelcontenthasreached 40%(inthe60%Sandspecimen). Fig.9bshowstheeffectofmixture percentageonstresspathresponse.SimilartothePeaGravelmixtures, asthemixturepercentageincreasestotheoptimum,theresponse changestofullystrainhardening,withnopost-peaksoftening.The uniformsanddisplayspost-peaksoftening,whilethegravel-sandmixturesanduniformgravelarestrainhardening. Fig.9dshowstheeffect ofmixturepercentageon ′ τσ / v ratioasstrainincreases.Alltestsreachan US,withthe60%Sandspecimenhavingthehighest ′ τσ / v ratio(approximately0.58).Thisplotalsoshowsthateven20%gravelhasa significantinfluenceontheUSresponsesinceeveryspecimenthat containsgravel(even80%Sandspecimen)hasahigher ′ τσ / v ratiothan 100%Sand. Fig.10 presentsthestress-strainresponseforDr =87% specimensofCLS8andOttawaC109sandmixtures.Theoptimum mixturepercentageinthesetestsisthe80%Sandspecimen,whilethe 60%Sandspecimen,whichhadthegreatestpost-peakshearstrength (bothPT,US)forDr =47%specimens,hastheweakestresponse.This responsecanbeexplainedifthevoidratioofthesandskeletononlyis examined.Thevoidratioofsandskeletononlywas0.574,0.559,and 0.590for100%Sand,80%Sand,and60%Sand,respectively.The80% Sand,whichhadasandskeletonvoidratioof0.559,hadthegreatest shearstrength,whilethe60%Sandspecimenhadthehighestsand skeletonvoidratioandexhibitedthelowestshearstrength.Thevoid ratioofthe100%Gravel(globalvoidratio)was0.575andthisspecimendisplayedresponsesimilartothe100%Sandwhichhada0.574 voidratio.Therefore,theresponsecanbeexplainedbyconsideringthe sandskeletonvoidratio.

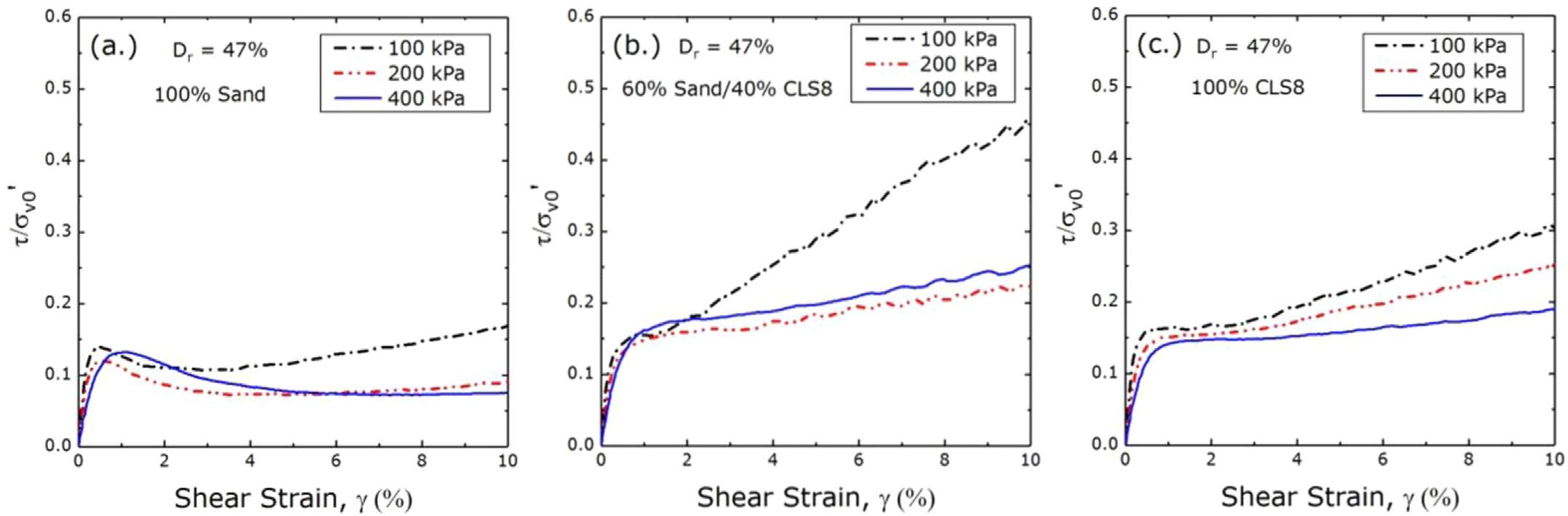

Tofurtherinvestigatetheeffectofrelativedensity, ′ τσ / v0 versus shearstrainwasplottedin Fig.11 for100%Sand,60%Sand,and100% Gravel.The100%Sandand100%Graveldisplaygreater ′ τσ / v0 values post-peak(i.e.morestrainhardeningoccurringinthedensespecimens).The60%SanddatashowsthattheDr =87%specimendisplays lessstrainhardeningpost-peak.TheglobalvoidratiosforthesespecimensareverysimilarwiththeDr =47%specimenhavingavoidratio of0.394andtheDr =87%specimenhavingavoidratioof0.354. Therefore,whenspecimensareneartheoptimummixture,therangeof possiblevoidratiosislowerandthespecimensdisplaysimilarresponse atlowandhighrelativedensities.Theeffectofinitialverticalstressfor CLS8mixtureswasalsoinvestigatedbyplotting ′ τσ / v0 versusshear strainasshownin Fig.12 for100%Sand,60%Sand,and100%Gravel. Foreachmixturepercentage,thepost-peakresponseislessstrain hardeningasinitialverticalstressincreases.The100%Sandspecimens exhibitpost-peakstrainsofteningandthenhardening;however,the 100%Graveland60%Sandspecimensarefullystrainhardening.This observationisimportanttoconsiderwhenevaluatingresponseatlarger shearstrains(greaterthan2%).

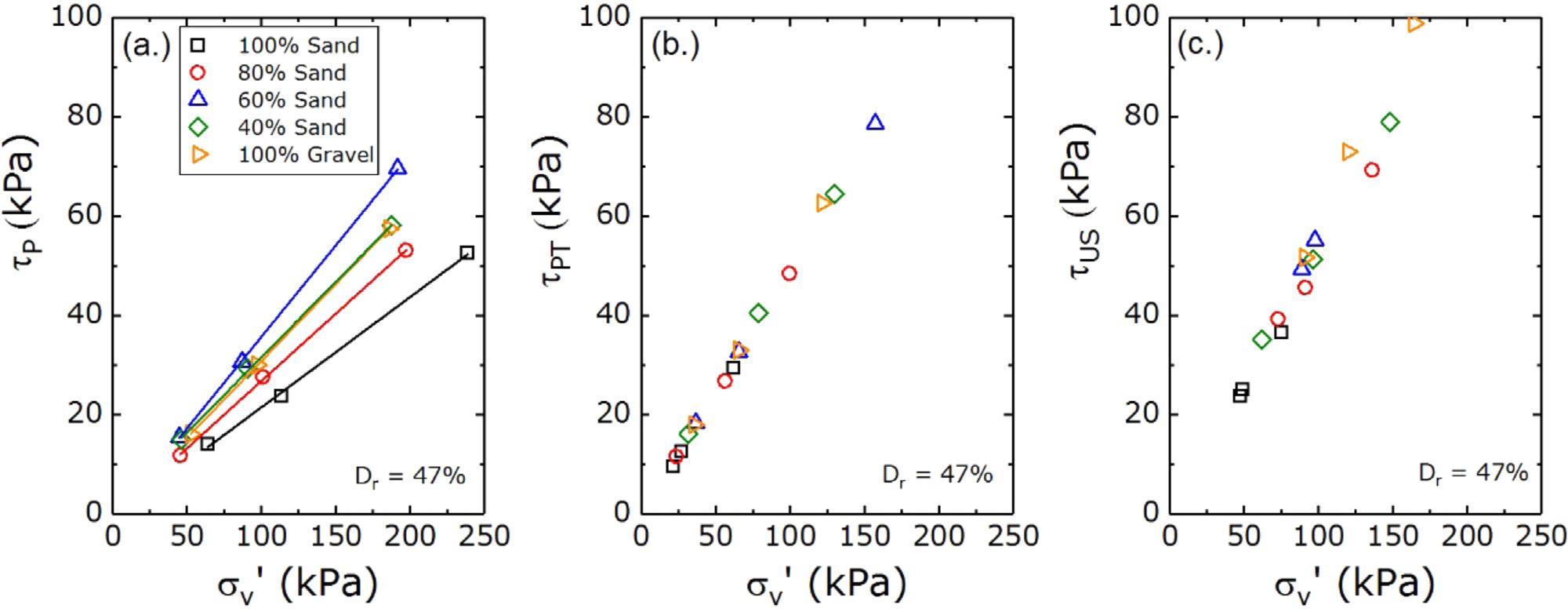

DatafromDr =47%specimensat100,200,and400kPawereused toevaluatethepeak,PT,andUSlinesin Figs.13and14.In Fig.13 the peak,PT,andUSshearstrengthsareplottedforPeaGravelmixtures. Linesweredrawnonthe figureshowingthepeakstrengthstomore easilyhighlightthetrends.40%Sandhadthehighestpeaklinewhile the100%Sandhadthelowestpeaklinewiththeothermixturesfalling inbetween. Fig.13bshowsthatthePTpointsfallalongasimilarline ( ′ = τσ/0.47 v ),whichisexpectedsincethePToftheuniformsandand gravelisverysimilar.SimilartrendsarealsoobservedfortheUS

Fig.11. Comparisonofeffectofrelativedensityfor(a)100%Sand,(b)60%Sand/40%CLS8,and(c)100%CLS8.

Fig.12. Comparisonofeffectofinitialverticalstressfor(a)100%Sand,(b)60%Sand/40%CLS8,and(c)100%CLS8.

Fig.13. Shearstrengthandverticaleffectivestressat(a)Peak,(b)Phasetransformation,and(c)UltimatestateforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47%.

responsein Fig.13c. Fig.14 illustratesthepeak,PT,andUSpointsfor CLS8mixtures.Inthiscase,60%Sandhadthehighestpeakline,while the100%Sandhadthelowestpeakline.AdifferentresponseisobservedfortheCLS8mixturescomparedtothePeaGravelmixtures, sincetheuniformCLS8isstrongerthanthePeaGravelduetoincreased particleangularity [18].Therefore,fortheCLS8mixtures,the80% Sandspecimenpeaklinefallsbelowthe100%Gravelwhichwasnotthe caseforPeaGravelmixtures.Anewoptimummixturepercentageis alsoobserved(40%SandforCLS8mixturescomparedto60%Sandfor PeaGravelmixtures).ThePTpointsfallalongasimilarlineagainfor theCLS8mixtures( ′ = τσ/0.50 v foroptimummixture),butthevalueis greaterthanthePeaGravelmixtures( ′ = τσ/0.46 v foroptimummixture),whichisattributedtotheincreasedshearresistanceoftheCLS8 gravelduetoincreasedangularity.ThereismorescatterintheUS

Fig.14. Shearstrengthandverticaleffectivestressat(a)Peak,(b)Phasetransformation,and(c)UltimatestateforCLS8mixturesatDr =47%.

Fig.15. Shearstrengthandverticaleffectivestressat(a)Peak,(b)Phasetransformation,and(c)Ultimatestateforevaluationofparticleangularityeffects.

responsewith100%SandhavingalowerUSvaluethanthe100% Gravel.The60%and40%SandspecimenshaveasimilarUStothe 100%Gravel,whichshowsthatthegravelportioniscontrollingUS responseinthosemixtures.

Tofurtherexaminetheeffectofparticleangularity,thepeak,PT, andUSfortheoptimummixturepercentagesforPeaGravel(40% Sand/60%PG)andCLS8(60%Sand/40%CLS8)wereplottedin Fig.15 with100%Sand,100%CLS8,and100%PeaGravelforDr =47% specimens.Thecomparisonshowsthatforthepeak,PT,andUS,the optimummixturefortheangularCLS8gravel-sandmixturehasthe greatestshearresistance. Fig.15ashowsthatthepeaklinefortheoptimummixtureforthesubroundedPeaGravelmixtureisapproximately thesameasthe100%CLS8gravelspecimen.The100%Sandand100% PeaGravelspecimensdisplaytheleastshearresistanceastheyare subroundedanduniformlygraded. Fig.15bshowsthatthePTlinesare dependentonparticlemorphology,withthe100%CLS8and60% Sand/40%CLS8mixturefallingalongasimilarPTlinewhichisabove (i.e.greatershearresistance)the100%Sand,100%PeaGravel,and 40%Sand/100%PeaGravelmixture.Similarly, Fig.15cshowsthatthe USlineforthe100%CLS8andtheoptimumCLS8mixtureplotabove the100%Sand,100%PeaGravel,and40%Sand/60%PeaGravel specimens.Aspreviouslydiscussed,thegravelfractioncontrolsthe specimen'spost-peakresponse,andthereforetheangularityofthe gravelisanimportantparameterwhenevaluatingPTandUSshear response.

3.3.Cyclicshearresponse

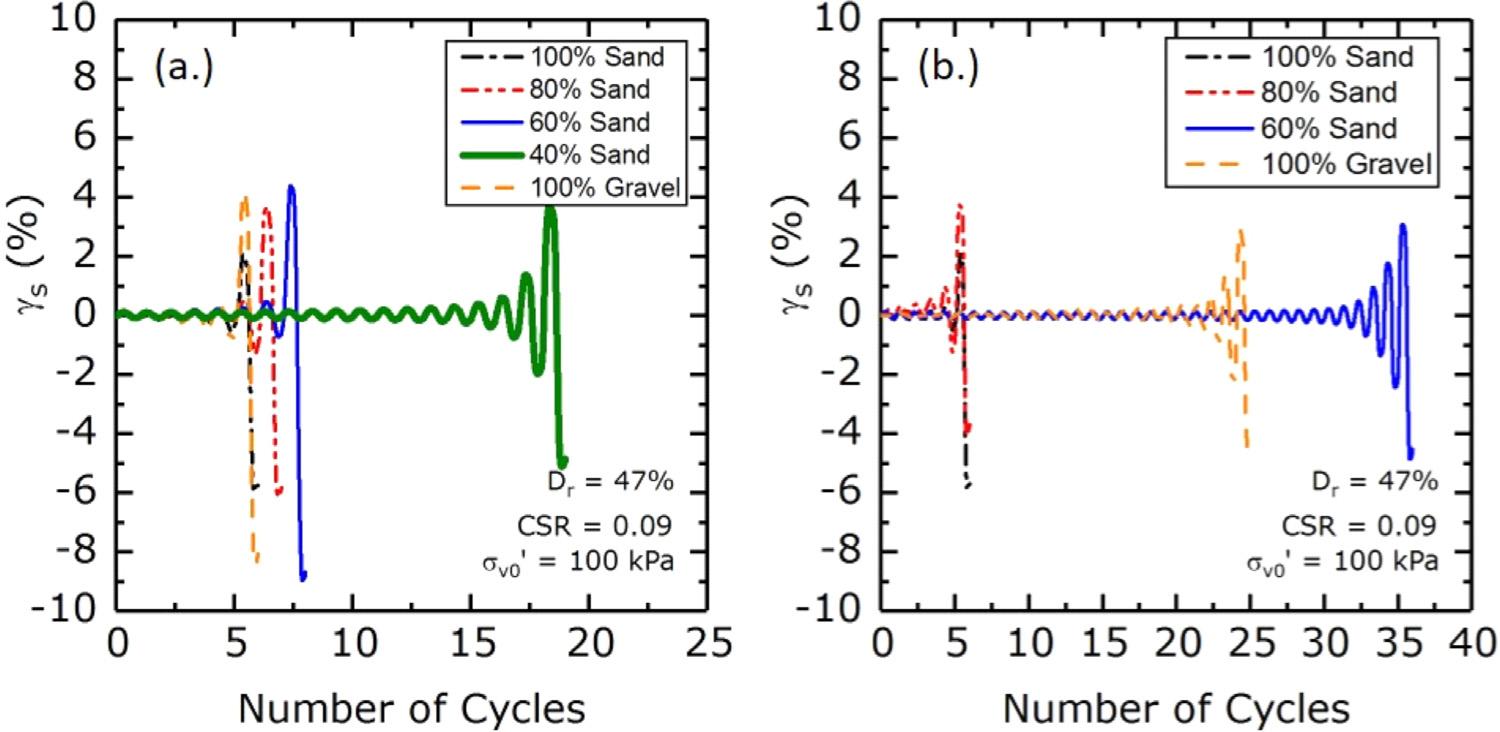

Constantvolumecyclicsimplesheartestswerealsoperformedon mixturesofPeaGravelandOttawaC109sandaswellasCLS8and OttawaC109sand.Specificparameters,includingmixturepercentage, CSR,andinitialverticalstressweretargetedforevaluation.ThebaselinetestswereperformedatCSR=0.09andataninitialverticalstress of100kPa.Liquefactionwasdefinedastheattainmentof3.75%single amplitudeshearstrain. Fig.16 showsexampleresultsforamixtureof 40%OttawaC109sandand60%PeaGravelforstress-strain(Fig.16a), stresspath(Fig.16b),porepressuregeneration(Fig.16c),andstrain development(Fig.16d).

3.3.1.Effectofmixturepercentage

Fig.17apresentsdataforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47%and ′ σv0 =100kPathatweretesteduntilliquefactionataCSR=0.09.This figureshowsthattheoptimummixturepercentageaccordingtothe monotonictestresults(40%Sandspecimen(VS =201m/s))alsoexhibitsthegreatestresistancetoliquefaction.The100%Sand(VS =190m/s)and100%Gravel(VS =180m/s)specimensliquefyinthe samenumberofcycles,whichisexpectedgiventhesimilarityofthese materialsfromaparticlemorphologyperspective(i.e.,roundness) [18]

Fig.16. Cyclicsimpleshearresultsfor40%Sand/60%CLS8GravelatDr =44%andCSR=0.09.

Sandcontrolsthecyclicresponseforthe80%Sand(VS =205m/s)and 60%Sand(VS =217m/s)specimensasevidencedbytheirnumberof cyclestoliquefactionincreasingbyonly1and2cycles,respectively, comparedto100%Sand,butthemeasuredVs ishigher.Althoughthe 60%SandspecimenhadthehighestVS at217m/sitliquefiedinfewer cyclesthanthe40%SandwhichhadaVS of201m/s.ThelowerVS of the40%Sandspecimencanbeattributedtothehighergravelcontent (whichhasaVS of180m/sfor100%Gravelwhichislessthan100% Sand).SimilarresultswerealsoobservedfortheCLS8mixturesas shownin Fig.17b.Theoptimummixturepercentagefromthemonotonictestresultsagaindisplayedthegreatestresistancetoliquefaction (60%Sandspecimen(VS =230m/s)).FortheCLS8mixtures,the100% Gravel(VS =204m/s)displayssignificantresistancetoliquefaction andrespondsquitedifferentlythan100%Sand,adifferencethatcanbe attributedtotheirdifferencesinparticlemorphology(i.e.angularvs. rounded)asdescribedinHubleretal. [18].Aspecimenwith80%Sand (VS =188m/s)respondedsimilarlytoaspecimenwith100%Sand indicatingthatthegravelskeletonwasnotinvolvedinloadtransfer duringcyclicshearing(i.e.thegravelwas floatingwithinthesand matrix).FortheCLS8mixturesanincreaseinVS correspondedtoan increaseinliquefactionresistance.

3.3.2.EffectofCSR

Fig.18apresentstheresultsforPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47% and ′ σv0 =100kPaforCSRsof0.04,0.09,and0.14.Thebvaluesfrom fittedpowerfunctionsrangedfromapproximately0.20to0.40.CSR wasfoundtohaveaneffectontheliquefactionresponseofthePea Gravelmixtures.ForCSR=0.14tests,the60%Sandand40%Sand specimensdisplayedhigherresistancetoliquefactionthantheother

mixes,whileatCSR=0.09,only40%Sandshowsanincreaseinresistancecomparedtotheothermixtures.ForCSR=0.04,80%Sand, 100%Sand,and100%Gravelexhibitsignificantlymoreresistanceto liquefactioncomparedtothe60%Sandand40%Sandmixtures.This showsthatatthelowerCSRvaluesthemixturesneartheoptimum mixturepercentage(40%Sand)arenotasresistanttoliquefactionas theuniformmaterials.Thiscouldbeexplainedbyexaminingtheparticleinteractionbetweenthesandandgravel.

SimilarresultswerealsoobservedfortheCLS8mixturesasshownin Fig.18b.Thebvaluesfrom fittedpowerfunctionsrangedfromapproximately0.20to0.35.ForCSR=0.14tests,100%Gravel,80% Sand,and60%Sandliquefyinasimilarnumberofcyclesandexhibit higherresistancethanthe100%Sandspecimen.The80%Sand/20% CLS8specimenrespondssimilarlytothe100%Gravel,whilethePea Gravelmixtureswith80%Sandrespondedsimilarlytothe100%Sand forCSR=0.14.ThissuggeststhatatCSR=0.14theangularCLS8is contributingtotheloadtransferforthe80%Sand/20%CLS8specimen. ForCSR=0.14tests,largerstrainsareappliedwhichmeansthatmore movementofparticlesoccursinthespecimenandfortheCLS8gravel engagementbetweentheparticlesduringtheselargerstrainscouldlead togreaterresistancetothecyclicloading.ForCSR=0.09tests,the 80%Sandspecimenrespondssimilarlytothe100%Sand.Thiscouldbe duetothesmallerstrainsinvolvedintheloadingmechanismwhichdo notallowthegravelparticlestofullyengageandcontributetotheload transfer.60%Sandand100%Graveldisplaysthemostresistanceto liquefactionatCSR=0.09.ForCSR=0.04tests,againtheuniform specimens(100%Sandand100%Gravel)exhibitedthemostresistance toliquefactioncomparedtothe80%Sandand60%Sandspecimens. ThedatapresentedhereshowsthatthelevelofCSR(andtherefore

Fig.17. Shearstrainversusnumberofcyclestoliquefactionfor(a)PeaGravelmixturesand(b)CLS8mixtures.

Fig.18. CSRversusnumberofcyclestoliquefactionfor(a)PeaGravelmixturesand(b)CLS8mixtures.

strainapplied)hasaneffectontheliquefactionresistanceofgravelsandmixtures.

3.3.3.Effectofinitialverticalstress

Fig.19apresentsresultsfortestsonPeaGravelmixturesatDr =47%andaCSR=0.09atverticalstressesof100,200,and400kPa. Theresultsshowthatthereisnotasignificanteffectofinitialvertical stressonthenumberofcyclestoliquefaction.The400kPaspecimen

(VS1 =N/A)liquefiedin17cycles,the200kPaspecimen(VS1 =197m/s)liquefiedin20cycles,andthe100kPaspecimen(VS1 =201m/s)liquefiedin18cycles.Thesedifferencesarenotsignificant andtheresponsecanbeconsideredindependentofinitialvertical stress.

Similarly, Fig.19bpresentstheresultsforCLS8mixturestestedatDr =47%andaCSR=0.09at100kPaand400kPa.FortheCLS8mixtures,aneffectofinitialverticalstressisobserved.The100kPa

Fig.19. Comparisonoftheeffectofinitialverticalstressfor(a)OptimumPeaGravelmixtureand(b)OptimumCLS8mixture.

Fig.20. Comparisonwithexistingliquefactiontriggeringchartsforgravellysoilsandsandsfor(a)PeaGravelmixturesand(b)CLS8mixtures(NL=15, Liquefaction=3.75%Singleamplitudeshearstrain).

specimen(VS1 =230m/s)liquefiedin36cycleswhilethe400kPa specimen(VS1 =205m/s)liquefiedin22cycles.Thisdifferencein responsemaybeattributedtothetendencyforlessstrainhardening (i.e.dilation)ofthe400kPaspecimen(asshownin Fig.12b).Itisalso possiblethattherearedifferencesinspecimenfabricasevidencedby thedifferenceinVS1 values.The100kPatestshadaVS1 valueof 230m/swhilethe400kPaspecimenhadaVS1 valueof205m/s.

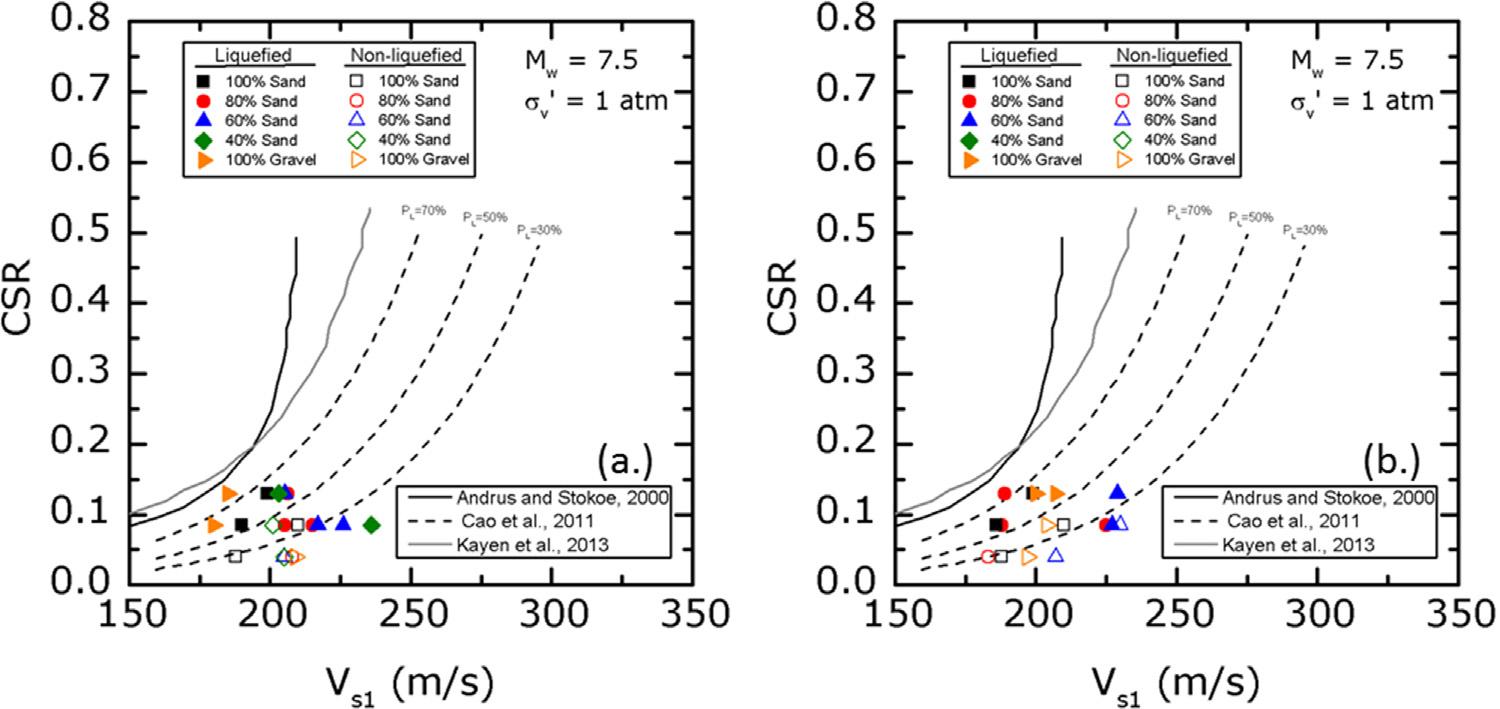

3.3.4.Comparisonwithexisting field-basedliquefactiontriggeringcharts SinceVS wasmeasuredfollowingconsolidationandbeforecyclic shearing,comparisonsofdatafromthisstudy(CSR,VS1)weremade withexistingliquefactiontriggeringchartsbasedon fieldcasehistories forsandyandgravellysoils.ThemethodforcorrectingdataandplottingonthecharthavebeendescribedinHubleretal. [18].

Fig.20ashowsacomparisonofthePeaGravelmixturedatawith existingrelationshipsfromAndrusandStokoe [2] forgravels,Kayen etal. [21] forsands(PL =15%),andCaoetal. [5] forgravels.Results showthatthePeaGravelmixturesliquefiedinthelaboratoryatVS1 valueshigherthan200m/sandashighasapproximately240m/s, whichisconsistentwiththe findingsofHubleretal. [18].Allofthe specimensthatliquefied,including100%Sand,wouldhavebeenpredictedasnon-liquefiableinthe fieldaccordingtobothAndrusand Stokoe [2] andKayenetal. [21] forsands.The100%Sandspecimens fellslightlybelowtheKayenetal. [21] line.Previousresearchershave shownthattheCRR-VS1 relationshiplinesarematerialdependent(i.e. responsedependsonparticlemorphology)andmaynotalways fitinto the field-basedVS charts [4,28].Laboratory-baseddatafromTokimatsu etal. [28] forsandsandBaxteretal. [4] forsiltareconsistentwiththe datainthisstudyforsand-gravelmixtures.Similarly, Fig.20bplotsthe CLS8mixtureswithexistingrelationshipsfromAndrusandStokoe [2] forgravels,Kayenetal. [21] forsands,andCaoetal. [5] forgravels. ResultsshowthattheCLS8mixturesliquefiedatVS1 valueshigherthan 200m/sandashighasapproximately230m/s.These findingssuggest thatgravellysoilsliquefyinthelaboratoryathigherVsthanpredicted basedon field-basedliquefactiontriggeringtests.Thishighlightsthe needforfurtherinvestigationoftheliquefactionbehaviorofgravelly soils,andespeciallycomparingthe “elementtests” inthelaboratory withthe fieldresponsebasedonsurficialobservations.

4.Conclusions

Themonotonicandcyclicshearresponseofgravel-sandmixtures wereevaluatedinthisstudy.Datawascomparedthroughoutthestudy forspecimensatthesamerelativedensity.VS wasmeasuredineach specimenandwasalsousedforcomparisonofdata.Thedatapresented inthisstudyrepresentssomeofthe firstcyclicsimplesheardatafor

gravel-sandmixturestestedinthelaboratory.Thefollowingareconclusionsofthisstudy:

• ForsubroundedPeaGravel/OttawaC109sandmixtures,therewas notasignificantchangeinVS asthemixturepercentageschanged. ThisislikelyduetothesimilarityinVS oftheuniformPeaGravel anduniformOttawaC109sand.ThemixturewiththehighestVS valuewasthe40%Sand/60%Gravelmixture.Alternatively,mixturepercentagehadasignificanteffectontheVS valuesforthe CLS8/OttawaC109sandmixtures.Inthiscase,theuniformangular CLS8anduniformOttawaC109sandhaddifferentVS values.The mixturewiththehighestVS valuewasthe60%Sand/40%Gravel mixture,followedbythe100%Gravelspecimen.

• Thestress-strainresponseofgravel-sandmixturesisdifferentcomparedtotheuniformgravelandsands,particularlyattheloosestate andforsubroundedmaterials.Thesubroundeduniformloosesand andPeaGravelexhibitacharacteristicpeakstressfollowedbystrain softeningtoaminimumshearresistancethatisfollowedbystrain hardeningresponseatlargestrains.TheangularuniformCLS8does notdisplaypost-peakstrainsoftening,whichhighlightstheimportanceofparticlemorphologyofthegravel-sandmixturematerials.Forgravel-sandmixtures,thestrainsofteningandstrain hardeningbecomeslesspronounced,andfortheoptimumgravelsandmixture,nostrainsofteningisobservedandstrainhardeningis lesspronouncedorcompletelyabsent.

• Thepercentageofgravelandsandinamixtureaffectsthemonotonicshearresponse.Thereexistsanoptimummixturepercentage ofgravelandsandthatmaximizesshearstrength.Theoptimum mixturepercentageforDr =47%specimenswasfoundtobe60% PeaGravel/40%OttawaC109sandforPeaGravelmixturesand 40%CLS8/60%OttawaC109sandforCLS8mixtures.Thisoptimum mixturehadthehighestpeakline(orfrictionangle)duringmonotonictestingaswellasthehighestVS value.Initialverticalstress wasshowntonotinfluencetheoptimummixturepercentage,but didaffectthestress-strainresponse.Relativedensityaffectedthe optimummixturepercentagefordensemonotonicspecimens; however,furthertestingisrequiredfordensespecimens.

• ThePhaseTransformationpointswerenotaffectedbymixture percentageforthePeaGravelmixtures,butincreasedtothelevelof 100%CLS8gravelwiththeadditionofonly20%CLS8totheCLS8 mixtures.

• ′ τσ / v ratiowasnearlyconstant(approximately0.50)atlargerstrains (i.e.theUS)forPeaGravelmixtures,regardlessofmixturepercentage;however,forCLS8mixturesthe ′ τσ / v ratioattheUSwasdependentonmixturepercentageandvariedfrom0.48to0.58.The ′ τσ / v ratiodidnotchangesignificantlyforthePeaGravelmixtures

sincetheuniformPeaGravelandOttawaC109sandhadsimilar shearresponsewhentestedindependently.Conversely,CLS8and OttawaC109haddifferentshearresponsewhentestedindependently,whichledtodifferentresultswhenmixed,highlightingthepossibleeffectofparticleangularity.

• Mixturepercentagewasshowntoalsoaffectthecyclicresponseof gravel-sandmixtures.FortestsatCSR=0.09andDr =47%,the optimummixturethatwasfoundfromthemonotonicsheartests exhibitedthegreatestresistancetoliquefaction.

• TheeffectofCSRonliquefactionresistancewasnotthesameforall gravel-sandmixturestestedinthisstudy.FortestsatCSR=0.04, mixturesof60%Sandand40%Sandweretheleastresistanttoliquefaction(comparedtotheothermixturesandthe100%Gravel and100%Sand),whileatCSR=0.14thesemixtureswerethemost resistantforbothmixturesofPeaGravelandCLS8.Thiscould possiblybeexplainedbyexaminingtheparticleinteractionbetween thesandandgravel.Itispossiblethatforcertainmixturesatthe lowerCSRvalue(andthereforelowerstrainlevel)thegravelisnot engagedinthesmallcyclicmovements(i.e.thesandiscontrolling theresponse).Inthe60%Sandand40%Sandspecimensmixedwith PeaGravel,thesandinbetweenthegravelisalsoinalooserstate thanatDr =47%(e=0.64),whichcouldexplainthefewernumber ofcyclestoliquefactionifthesandiscontrollingtheresponse.The sandskeletonvoidratioforthe60%SandspecimenatDr =47%is 0.70,whilethesandskeletonvoidratioforthe40%Sandspecimen atDr =47%is0.83.Thisshowsthatthesandskeletonislikely controllingresponseandthereforeliquefyinginfewercyclesthan thee=0.64(Dr =47%)100%Sandspecimen.

• Theparticleangularityofthegravelinagravel-sandmixtureaffects theresponseduringmonotonicandcyclictests.ThesubroundedPea Gravelmixtureshadadifferentoptimummixturepercentagethan theangularCLS8gravelmixtures.

• Initialverticalstresswasshowntonothaveasignificanteffecton theliquefactionresistanceofPeaGravelmixtures.CLS8mixtures exhibitedaneffectofinitialverticalstress,andthiscouldbedueto lowerdilationoccurringasinitialverticalstressincreasesaswellas differencesinspecimenVS

• Thetestedgravel-sandmixturesliquefiedatVS1 valueshigherthan 200m/sandashighasapproximately240m/s.Allofthespecimens thatliquefied,includingthecleansand,wouldhavebeenpredicted asnon-lique fiableaccordingtoexisting field-basedtriggeringcorrelations [2,21]

Acknowledgments

ThismaterialisbaseduponworksupportedbytheNationalScience FoundationGraduateStudentResearchFellowshipunderGrantNo. DGE1256260andbytheNationalScienceFoundationCAREERGrant No.1351403andCMMIgrantNo.1663288.Anyopinions, findings, andconclusionsorrecommendationsexpressedinthismaterialare thoseoftheauthorsanddonotnecessarilyreflecttheviewsofthe NationalScienceFoundation.ConeTecInvestigationsLtd.andthe ConeTecEducationFoundationareacknowledgedfortheirsupportto theGeotechnicalEngineeringLaboratoriesattheUniversityof Michigan.TheauthorswouldalsoliketothankZontaOwensforhisaid inspecimenpreparationandlaboratorytesting.

References

[1] AndrusRD.Insitucharacterizationofgravellysoilsthatliquefiedinthe1983Borah

Peakearthquake[Ph.D.thesis].Austin,TX:UniversityofTexasatAustin;1994

[2] AndrusRD,StokoeIIKH.Liquefactionresistanceofsoilsfromshear-wavevelocity. JGeotechGeoenvironEng2000;126(11):1015 –25

[3] BanerjeeNG,ChanCK,SeedHB.Cyclicbehaviorofdensecoarsegrainedmaterials inrelationtotheseismicstabilityofdams.Berkeley,CA:UniversityofCalifornia; 1979

[4] BaxterCD,BradshawAS,GreenRA,WangJH.Correlationbetweencyclicresistance andshear-wavevelocityforprovidencesilts.JGeotechGeoenvironEng 2008;134(1):37–46

[5] CaoZ,YoudTL,YuanX.Gravellysoilsthatliquefiedduring2008Wenchuan,China earthquake,Ms=8.0.SoilDynEarthqEng2011;31(8):1132–43

[6] ChangWJ,ChangCW,ZengJK.Liquefactioncharacteristicsofgap-gradedgravelly soilsinK0 condition.SoilDynEarthqEng2014;56:74–85

[7] ChangWJ,PhantachangT.Effectsofgravelcontentonshearresistanceofgravelly soils.EngGeol2016;207:78–90

[8] DyvikR,BerreT,LacasseS,RaadimB.Comparisonoftrulyundrainedandconstant volumedirectsimplesheartests.Geotechnique1987;37(1):3–10

[9] EvansMD,SeedHB.Undrainedcyclictriaxialtestingofgravels – theeffectof membranecompliance.1987–07.Berkeley:EarthquakeEngineeringResearch Center,UniversityofCalifornia;1987.p.434.[UCB/EERC-87/08].

[10] EvansMD,SeedHB,SeedRB.Membranecomplianceandliquefactionofsluiced gravelspecimens.JGeotechEng1992;118(6):856–72

[11] EvansMD,ZhouS.Liquefactionbehaviorofsand-gravelcomposites.JGeotech Engrg1995;121(3):287–98

[12] FragaszyRJ,SuW,SiddiqiFH.Effectsofoversizeparticlesonthedensityofclean granularsoils.GeotechTestJ1990;13(2):106–14

[13]GEER(2014). “EarthquakeReconnaissanceJanuary26th/February2nd 2014 Cephalonia,Greeceevents,Version1.” Nikolaou,S.,Zekkos,D.,Assimaki,D., Gilsanz,R.(Eds.),GEER/EERI/ATC,p.492.

[14]GEER(2017). “GeotechnicalReconnaissanceofthe2016Mw 7.8Kaikoura,New ZealandEarthquake,Version1.0.” Cubrinovski,M.andBray,J.(Eds.),GEER,p. 247.

[15] HarderJrLF,SeedHB.Determinationofpenetrationresistanceforcoarse-grained soilsusingthebeckerpenetrationtest.Berkeley:UniversityofCalifornia;1986. [EERCReportNo.UCB/EERC-86-06]

[16] HatanakaM,UchidaA,SuzukiY.Correlationbetweenundrainedcyclicshear strengthandshearwavevelocityforgravellysoils.SoilsFound1997;37(4):85–92

[17] HoltzWG,GibbsHJ.Triaxialsheartestsonperviousgravellysoils.JSoilMech FoundDiv,ASCE1956;82(SM1):1 –22

[18] HublerJF,Athanasopoulos-ZekkosA,ZekkosD.Monotonic,cyclicandpost-cyclic simpleshearresponseofthreeuniformgravelsinconstantvolumeconditions.J GeotechGeoenvironEng2017;143(9):04017043.[2017]

[19]HublerJF,Athanasopoulos-ZekkosA,ZekkosD.PorePressuregenerationofpea gravel,sand,andgravel-sandmixturesinconstantvolumesimpleshear.In: Proceedingsofthe3rdinternationalconferenceonperformance-baseddesignin earthquakegeotechnicalengineering(PBD-III).

[20] HublerJF.Laboratoryandin-situassessmentofliquefactionofgravellysoils[Ph.D. dissertation].AnnArbor:UniversityofMichigan;2017

[21] KayenR,MossRES,ThompsonEM,SeedRB,CetinKO,KiureghianAD,Tokimatsu K.Shear-wavevelocity–basedprobabilisticanddeterministicassessmentofseismic soilliquefactionpotential.JGeotechGeoenvironEng2013;139(3):407–19

[22] KokushoT,HaraT,HiraokaR.Undrainedshearstrengthofgranularsoilswith differentparticlegradations.JGeotechGeoenvironEng2004;130(6):621–9

[23] MenqF-Y.Dynamicpropertiesofsandyandgravellysoils[Ph.D.thesis].Austin: UniversityofTexas;2003

[24]NikolaouS,ZekkosD,AsimakiD,GilsanzR.ReconnaissanceHighlightsofthe2014 sequenceofearthquakesinCephalonia,Greece.In:Proceedingsofthe6thinternationalconferenceonearthquakegeotechnicalengineering,1–4November2015, Christchurch,NewZealand;2015.

[25] RashidianM.Undrainedshearingbehaviorofgravellysandsanditsrelationwith shearwavevelocity[Ph.D.thesis].Tokyo,Japan:UniversityofTokyo;1995 [26] SivathayalanS.Fabric,initialstateandstresspatheffectsonliquefactionsusceptibilityofsands[Ph.D.thesis].Vancouver,BC:UniversityofBritishColumbia;2000 [27] ThevanayagamS.Effectof finesandconfiningstressonundrainedshearstrengthof siltysands.JGeotechGeoenvironEng1998;124(6):479–91

[28] TokimatsuK,YamazakiT,YoshimiY.Soilliquefactionevaluationsbyelasticshear moduli.SoilsFound1986;26(1):25–35

[29]WongRT,SeedHB,ChanCK.Liquefactionofgravellysoilsundercyclicloading conditions.UCB/EERC-74/11,1974-06,46p;1974.

[30] YoudT,HarpE,KeeferD,WilsonR.TheBorahPeak,IdahoEarthquakeofOctober 28,1983Liquefaction.EarthqSpectra1985;2(1):71–89

[31]ZekkosD,Athanasopoulos-ZekkosA,HublerJF,FeiX,ZehtabK,MarrA. Developmentofalarge-sizeCyclicsimplesheardeviceforcharacterizationof groundmaterialswithOversizedparticles.ASTMGeotechTestJ 2018;41(2GTJ20160271). https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ2016027

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

By the morning light it was easy to find the path which the night’s shadows had hidden from him, and being very hungry he started out to seek some dwelling. The path led away from the temple, in an opposite direction to that from which he had come the night before. Soon, however, he came out of the forest and saw a little hamlet surrounded by green fields.

“How fortunate I am,” he cried joyfully. “Here are houses, and so there must be people, and people must have something to eat. If they are kind they will share with me, and I am starving for a bowl of rice.”

He hurried to the nearest cottage, but as he approached he heard sounds of bitter weeping. He went up to the door, and was met by a sweet young girl whose eyes were red with crying. She greeted him kindly, and he asked her for food.

“Enter and welcome,” said she. “My parents are about to be served with breakfast. You shall join them, for no one must pass our door hungry.”

Thanking her the young warrior went in and seated himself upon the floor. The parents of the young girl greeted him courteously. A small table was set before him, and on it was placed rice and tea. He ate heartily, and, when he had finished eating, rose to go.

“Thank you very many times for such a good meal, kind friends,” he said.

“You have been welcome. Go in peace,” said the master of the house.

“And may happiness be yours,” returned the young Samurai.

“Happiness can never again be ours,” said the old man, with a sad face, as his daughter left the room. Her mother followed her and from behind the paper partitions of the breakfast room, Wakiki could hear sounds as if she were trying to comfort the young girl.

“You are then in trouble?” he asked, not liking to be inquisitive, and yet wishing to show sympathy.

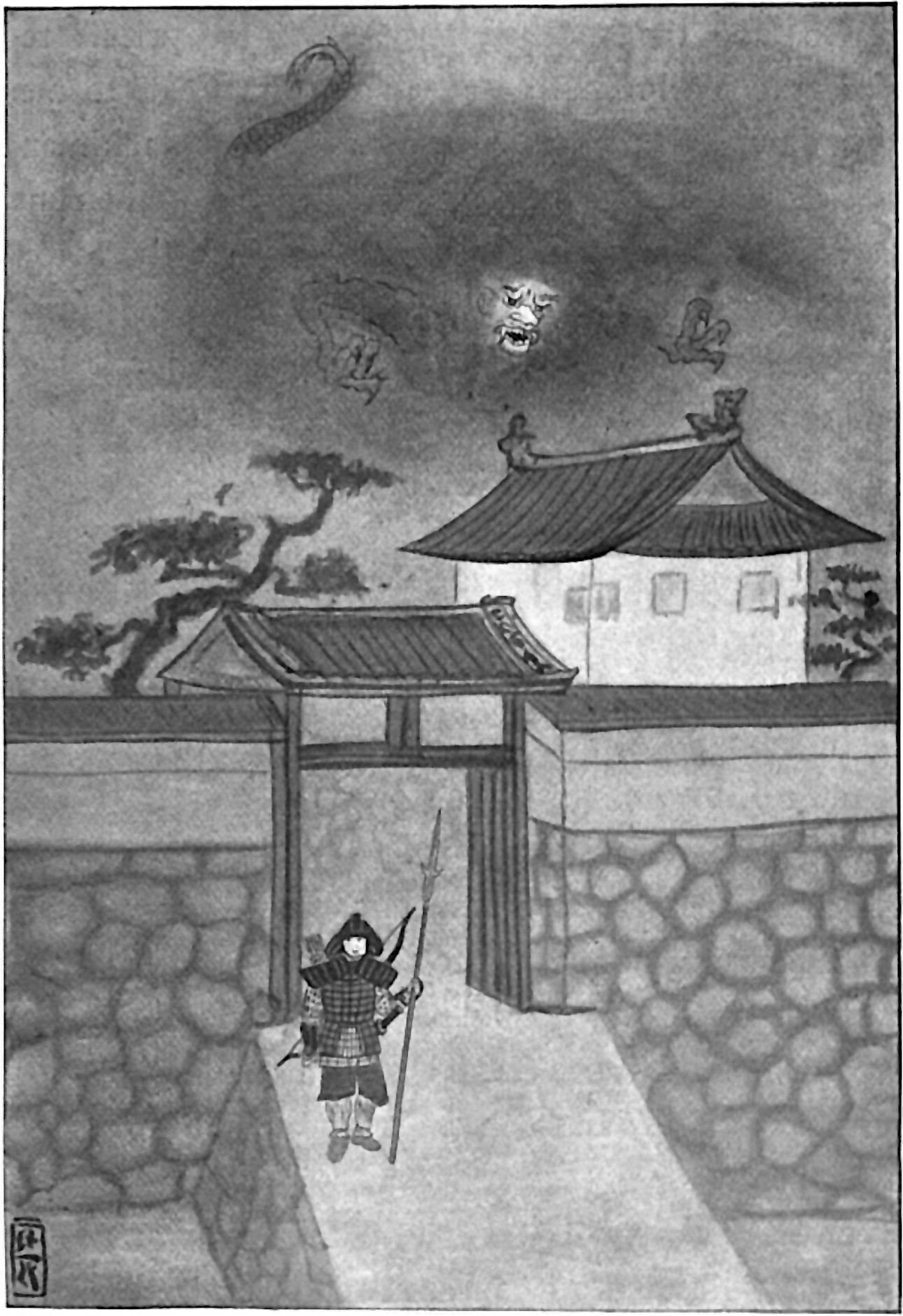

“Terrible trouble,” said the father. “There is no help! Know, gentle Samurai, that there is within the forest a ruined temple. This shrine, once the home of sacred things, is now the abode of horrors too terrible for words. Each year a mountain spirit, a demon whom no

one has ever seen, demands from us a victim, upon pain of destroying the whole village. The victim is placed in a cage and carried to the temple just at sunset. There she is left and no one knows what is her fate, for in the morning not a trace of her remains. It must always be the fairest maiden of the village who is offered up and this year, alas, it is my daughter’s turn;” and the old man buried his face in his hands and groaned.

“I should think this strange thing would make the young girls of your village far from vain and each would wish to be the ugliest,” said the young warrior. “It is terrible indeed, but do not despair. I am sure I shall find a way to help you.” He paused to think. “Tell me, who is Shippeitaro?” he asked suddenly, as he remembered the scene of the night before.

“Shippeitaro is a beautiful dog owned by our lord the prince,” said the old man, wondering at the question.

“That will be just the thing,” cried the Samurai. “Keep your daughter closely at home. Do not allow her out of your sight. Trust me and she shall be saved.”

He hurried away, and having found the castle of the prince, he begged that just for one night Shippeitaro be lent to him.

“Upon condition that you bring him back to me safe and sound,” said the prince.

“To-morrow he shall return in safety,” the young warrior promised. Taking Shippeitaro with him he returned to the village; and when evening came, he placed the dog in the cage which was to have carried the maiden.

“Take him to the ruined temple,” he said to the bearers, and they obeyed.

When they reached the little shrine they placed the cage on the ground and ran away to the village as fast as their legs could carry them. The young warrior laughed softly, saying to himself, “For once fear is greater than curiosity.”

He hid himself in the little temple as before, and so quiet was the spot that he could scarcely keep awake. Soon he was aroused, however, by the same weird chant he had heard the evening before. Through the darkness came the same troop of fearful phantom cats

led by a fierce Tom cat, the largest he had ever seen. As they came, they chanted with unearthly screeches,

“Whisper not to Shippeitaro, That the phantom cats are near, Whisper not to Shippeitaro Lest he soon appear.”

The song was scarcely ended, when the great Tom cat caught sight of the cage and sprang upon it with a fierce yowl. With one sweep of his paw he tore open the lid, when instead of the dainty morsel he had expected, out leaped Shippeitaro! The noble dog sprang upon the beast and shook him as a cat shakes a rat, while the other beasts stood still in amazement. Drawing his sword the young warrior dashed to Shippeitaro’s aid and to such good purpose that in a few moments the phantom cats were no more.

“Brave dog!” cried Wakiki. “You have delivered a whole village by your courage! Let us return and tell the people what has happened, that all men may do you honor.”

Patting the dog on the head he led him back to the village. There in terror the maiden awaited his return, but great was her joy when she heard of her deliverance.

“Oh, sir,” she cried. “I can never thank you! I am the only child of my parents, and no one would have been left to care for them had I gone to be the monster’s victim!”

“Do not thank me,” said the young warrior. “I have done little. All the thanks of the village are due to the brave Shippeitaro. It was he who destroyed the phantom cats.”

[2] The nightingale.

Footnotes

[3] Japanese word for soldier.