SPT-based probabilistic and deterministic assessment of seismic soil liquefaction triggering hazard K. Onder Cetin & Raymond B. Seed & Robert E. Kayen & Robb E.S. Moss & H. Tolga Bilge & Makbule Ilgac & Khaled Chowdhury https://ebookmass.com/product/spt-basedprobabilistic-and-deterministic-assessment-ofseismic-soil-liquefaction-triggering-hazard-konder-cetin-raymond-b-seed-robert-e-kayen-robb-es-moss-h-tolga-bilge-makbule-ilgac/

Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Elsevier Weekblad - Week 26 - 2022 Gebruiker

https://ebookmass.com/product/elsevier-weekbladweek-26-2022-gebruiker/

Jock Seeks Geek: The Holidates Series Book #26 Jill Brashear

https://ebookmass.com/product/jock-seeks-geek-the-holidatesseries-book-26-jill-brashear/

The New York Review of Books – N. 09, May 26 2022

Various Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-york-review-ofbooks-n-09-may-26-2022-various-authors/

Calculate with Confidence, 8e (Oct 26, 2021)_(0323696953)_(Elsevier) 8th Edition Morris Rn Bsn Ma Lnc

https://ebookmass.com/product/calculate-withconfidence-8e-oct-26-2021_0323696953_elsevier-8th-edition-morrisrn-bsn-ma-lnc/

1 st International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainability in Music, Art, Textile and Fashion (ICESMATF 2023) January, 26-27 Madrid, Spain Exhibition

Book 1st Edition Tatiana Lissa

https://ebookmass.com/product/1-st-international-congress-andexhibition-on-sustainability-in-music-art-textile-and-fashionicesmatf-2023-january-26-27-madrid-spain-exhibition-book-1stedition-tatiana-lissa/

Empirical Correlation of Soil Liquefaction Based on SPT TV-Value and Fines Content Kohji Tokimatsu & Yoshiaki Yoshimi

https://ebookmass.com/product/empirical-correlation-of-soilliquefaction-based-on-spt-tv-value-and-fines-content-kohjitokimatsu-yoshiaki-yoshimi/

Probabilistic

knowledge Moss

https://ebookmass.com/product/probabilistic-knowledge-moss/

Fragility-based seismic performance assessment of modular underground arch bridges Van-Toan Nguyen

https://ebookmass.com/product/fragility-based-seismicperformance-assessment-of-modular-underground-arch-bridges-vantoan-nguyen/

Deterministic Numerical Modeling of Soil Structure Interaction 1st Edition Stephane Grange

https://ebookmass.com/product/deterministic-numerical-modelingof-soil-structure-interaction-1st-edition-stephane-grange/

SoilDynamicsandEarthquakeEngineering

journalhomepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soildyn

SPT-basedprobabilisticanddeterministicassessmentofseismicsoil liquefactiontriggeringhazard

K.OnderCetina,⁎,RaymondB.Seedb,RobertE.Kayenb,RobbE.S.Mossc,H.TolgaBilged, MakbuleIlgaca,KhaledChowdhuryb,e

a Dept.ofCivilEngineering,MiddleEastTechnicalUniversity,Ankara,Turkey

b Dept.ofCivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley,CA,USA

c CaliforniaPolytechnicStateUniversity,SanLuisObispo,CA,USA

d GeoDestekLtd.Sti.,Ankara,Turkey

e USArmyCorpsofEngineers,SouthPacificDivisionDamSafetyProductionCenter,Sacramento,CA,USA

ARTICLEINFO

Keywords: Soilliquefaction Earthquake Seismichazard Cyclicloading

Standardpenetrationtest

In-situtest Probability

1.Introduction

ABSTRACT

ThisstudyservesasanupdatetotheCetinetal.(2000,2004)[1,2]databasesandpresentsnewliquefaction triggeringcurves.Comparedwiththesestudiesfromoveradecadeago,theresultingnewStandardPenetration Test(SPT)-basedtriggeringcurveshaveshiftedtoslightlyhigherCSR-levelsforagivenN1,60,CS forvaluesof N1,60,CS greaterthan15blows/ft,butthecorrelationcurvesremainessentiallyunchangedatN1,60,CS valuesless than15blows/ft.Thispaperaddressestheimproveddatabaseandthemethodologiesusedforthedevelopment oftheupdatedtriggeringrelationships.Acompanionpaperaddressestheprincipalissuesthatcausedifferences amongthreewidelyusedSPT-basedliquefactiontriggeringrelationships.

Empiricalfield-basedframeworksfortheassessmentofseismicsoil liquefactiontriggeringhazardcontinuestobetheprincipalapproach usedinengineeringpractice.Threein-situindextestmethods;the StandardPenetrationTest(SPT),theConePenetrationTest(CPT),and themeasurementofin-situShearWaveVelocity(Vs)havereacheda levelofdevelopmentinthefieldsuchthattheirusagehasbeenapplied worldwide.Thesethreemethodsandthedatasupportingthemare discussedindetailintherecent2016reportoftheNationalAcademies Sciences,Engineering,andMedicine,CommitteeonGeologicaland GeotechnicalEngineering(COGGE):“StateoftheArtandPracticein theAssessmentofEarthquake-InducedSoilLiquefactionandits Consequences”,(NAP [3]).Advancesintestproceduresinafourth method,theBeckerPenetrationTest(BPT)mayexpandthetest'susage inthefuture.Newmethodsareunderdevelopment,thoughthesefour testsremainthecornerstoneofempiricaltestmethodologies.

TheauthorsusedtheopportunitypresentedbytheNAPcommittee reporttore-evaluate,organize,updatethedatabaseofCetinetal. [2] (hereafter,CEA2004),andthencastnewregressionmodelsforseismic soilliquefactiontriggeringbasedonthedataimprovements.

2.UpdatedCetinetal. [4,9] database

ThecasehistoriesofCEA2004arere-visitedsoastocorrecterrorsin theoriginaldocument,aswellastakeadvantageofupdatesinthe currentstateofknowledge.Changestothedatabaseincludethefollowing:

(1)Atypographicalerroratthethirddecimalpointinthespreadsheet executionoftherd formulaintheoriginalworkofCetinetal. [2] wasidentified.Thiserrorbiasedrd valuestowardsthelowside.The effectwasnegligibleatthegroundsurfaceandincreasedwith depth.Theoverallaverageincreaseinthenewrd valuesforthe150 affectedcasehistorieswas6.1%.Theremaining50fieldperformancecasehistorieshadrd valuesdirectlycalculatedfromsitespecificandevent-specificseismicsiteresponseanalyses(Cetin etal. [1],Cetin [5]).Sincethese50rd valueswereproperlyestimatedintheoriginaldatabase,theysimplyremainunchanged.A briefdiscussionoftheconsistentuseofCetinandSeed [6] rd relationshipwillbepresentedlaterinthismanuscript,andamore detaileddiscussionisavailableinCetinetal. [7]

Theestimationofrd valuesinCetinandSeed [6] requirestheestimationofrepresentativeshearwavevelocityintheupper12mof

⁎ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses: kemalondercetin@gmail.com, ocetin@metu.edu.tr (K.O.Cetin).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.09.012

Received11July2017;Receivedinrevisedform6September2018;Accepted12September2018

Availableonline12October2018

0267-7261/©2018ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Nomenclature

amax peakhorizontalacceleration

CB SPTcorrectionforboreholediameter

CE SPTcorrectionforhammerenergyratio(ER)

CN overburdencorrectionfactor

CR SPTcorrectionfactorfortherodlength

CS SPTcorrectionforsamplerconfigurationdetails

CSRcyclicstressratio

CSR M 1atm,0,7.5 v w === CSRnormalizedtoσ'v =1atm,Mw =7.5and α=0

CSR M 1atm,7.5 v w == CSRnormalizedtoσ'v =1atm,Mw =7.5

CSR M ,, v w actualCSR,notnormalizedtoareferencestateofσ'v =1 atm,Mw =7.5andα=0

CSR M , v w actualCSR,notnormalizedtoareferencestateofσ'v =1 atm,Mw =7.5

CSRpeak M v w peakCSR,notnormalizedtoareferencestateofσ'v = 1atm,Mw =7.5

CRRcyclicresistanceratio

dcr =dcriticaldepthforliquefaction

DR relativedensity

FCfinescontent

FSfactorofsafetyagainsttriggeringofliquefaction gaccelerationofgravity

Hi thicknessofsoilsublayers

K Mw correctionformagnitude(duration)effects

K correctionforoverburdenstress

K correctionforslopingsites

Nfieldmeasuredstandardpenetrationresistance(blows/30 cm)

N60 standardpenetrationtestblowcountvaluecorrectedfor energy,equipmentandproceduralfactors

N1 standardpenetrationtestblowcountvaluecorrectedfor overburden.

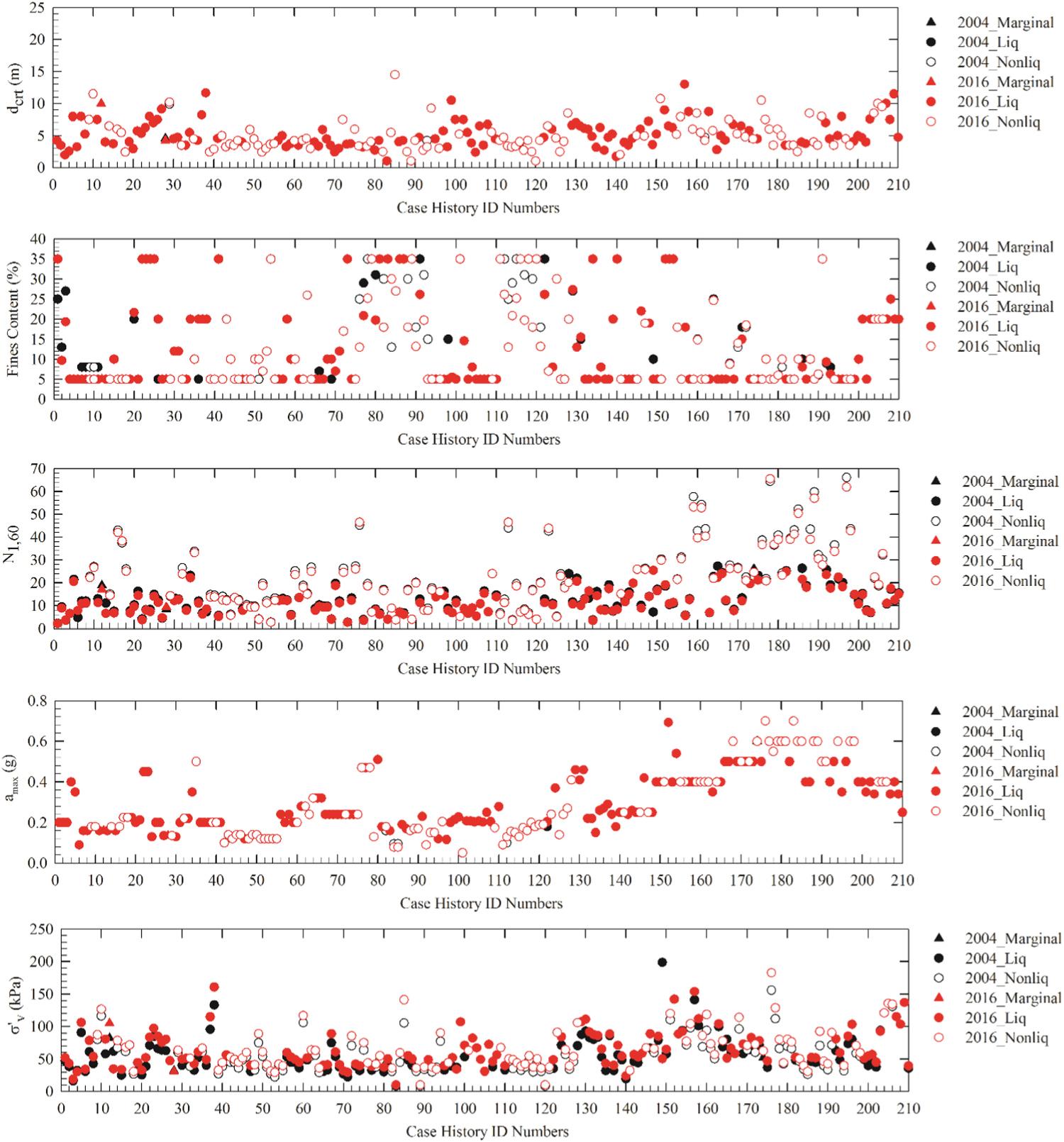

thesoilprofile.Comparedtotheearlierversionofthedatabase, shearwavevelocitiesforthe150casesincreasedonaverage6.6%. ThechangestoVs hadanegligibleimpactontheestimatedrd values,howevertheywereperformedforconsistencybyfollowingthe recommendationsofJapanRoadAssociation [8] Fig.1 presentsa visualcomparisonbetweentheback-analyzedfieldperformance casehistoryinputparametersoftheCEA2004andCetinetal. [4,9] databases.Inthisfigure,theblackandredsymbolsrepresentthe valuesfromCEA2004andCetinetal. [4,9],respectively.

(2)Unitweightsforeachcasehistorysitewereupdatedasgivenin Table1,unlesstheavailablecase-specificinformationwasindicatingotherwise.Individualunitweightsforeachcase,andeach stratum,typicallyvaryslightlybasedoninformationavailable. DetailsforeachcasehistoryarepresentedinCetinetal. [4,9].The updatedunitweightsare,typically,verycloseto,andslightlylower than,theaveragevaluescommontothedatabasesofCetinetal. [4,9] andIdrissandBoulanger [10] (hereafterIB2010).Inthe average,theγmoist andγsaturated valuesincreasedbyapproximately 10%ascomparedtothevaluesusedinCEA2004.Meanvaluesof theunitweightsusedforcasehistoryprocessingwillbepresented laterinthemanuscript.Thechangesinunitweightaffectthevalues oftotalandeffectivestresses.

(3)Theconversionofatmosphericpressure(Pa)fromatmospheresto kilopascalstopounds-per-square-footwassetaccuratelyasfollows forallcasehistories:1atm 101.3kPa 2116.2lbs/ft2.In CEA2004,theseconversionswhichareneededfortheeffective stressadjustments(CN)toSPTblowcountsandKσ adjustmentsfor cyclicstressratiowereapproximatedas1atm=100kPa=2000 lbs/ft2.Theseadjustmentsandupdateswerecommontoallcase

N1,60 standardpenetrationtestblowcountvaluecorrectedfor overburden,energy,equipmentandproceduralfactors

N1,60,cs fines-correctedN1,60 value

ΔN1,60 SPTpenetrationresistancecorrectionforfinescontent

Mearthquakemagnitude

Mw earthquakemomentmagnitude

ML earthquakelocalmagnitude

Ms earthquakesurfacewavemagnitude

Pa atmosphericpressure(1atm)

PL probabilityoftriggeringofliquefaction

PIplasticityindex

rd shearmassmodalparticipationfactor,commonlyreferred toascyclicshearstressreductionfactor

SPT-Nstandardpenetrationtestblowcount

Wliq correctiveweightingfactorfortheliquefieddata

Wnonliq correctiveweightingfactorforthenon-liquefieddata

Vs shearwavevelocity

Vs,12m shearwavevelocityfortheupper12m

γsat unitweigthbelowgroundwatertable

γmoist unitweigthabovegroundwatertable standarddeviation

standarddeviationofthemodeluncertainty

Φ standardcumulativenormaldistribution standardnormaldensityfunction

ε modelerrorterm

r , d standarddeviationofthemodeluncertaintyofrd

σ'v verticaleffectivestress

σv verticaltotalstress

θlimitstatemodelcoefficient setofunknownmodelcoefficients

ΔN1,60 SPTpenetrationresistancecorrectionforfinescontent

αinitialstaticdrivingshearstressratio;α= τhv,static /σ'v max maximumshearstrain

histories.

SomemodificationsweremadetoselectedcasehistoriesperobservationsofIdrissandBoulanger [11].Theauthorsexcludedthree casesfromtheCEA2004database:(1)1975HaichengEarthquake(Ms =7.3)ShungTaiZiRiver,(2)1994NorthridgeEarthquake(Mw =6.7) MaldenStreetUnitD,and(3)1979ImperialValleyEarthquake(ML = 6.6)WildlifeUnitB.Thereasonsforexclusionofthesecasesaresummarizedin Table2

Threecasehistorysites(1)1989LomaPrietaEarthquake(Mw = 6.93)ClintMillerFarm(CMF-10),and1995Hyogoken-Nanbu Earthquake(Mw =6.9)Kobe(2)#6and(3)#16arenowreclassified asnon-liquefactionsites.Additionally,(4)thecriticaldepthofthe1993 Kushiro-OkiEarthquake(Mw =7.6)KushiroPortstrongmotionrecordingstationcasehistorysiteismodified.Thereasonsforthemodificationsofthesecasesaresummarizedin Table3

Recentworkongroundmotionmodelsand,inparticular,thedatabasedevelopmentoftheNextGenerationAttenuation(NGA)project, hasprovidednewinsightintosomeofthehistoricalearthquakemagnitudesand,therefore,estimatedpeakgroundaccelerationlevels.New momentmagnitudesforeventsaresummarizedin Table4,andtheyare comparedwiththemomentmagnitudesusedinCEA2004.Changesin momentmagnitudesarerelativelyminorandweremadeforcompleteness.Thechangestomagnitudehadanegligibleimpactonthe triggeringcorrelations.

Allothercaseswerealsoreviewed,andforsomecases,detailssuch astheelevationofthephreaticsurface,amax,averagefinescontent, criticaldepth,averageSPT-Nvalues,CR and/orCB correctionswerereassessedandadjusted.Asshownin Fig.1,resultingmodificationshere

Fig.1. Comparisonofcasehistorymodelinputparameters(a)dcrt (b)Finescontent(c)N1,60 (d)amax (e)σ'v forCEA2004andCetinetal. [4,9].(Casehistoriesare numberedaslistedin TableS1).ComparisonofcasehistorymodelinputparametersforCEA2004andCetinetal. [4,9].(f)σv (g)Vs (h)rd (i)Mw (j)CSR.(Case historiesarenumberedaslistedin TableS1).

weretypicallyminorandhadnosignificantimpactontheresulting liquefactiontriggeringcorrelationsdeveloped.

TheIB2010SPT-catalogdatabasehas230casehistories,andmany arethosescreenedandcompiledbyCEA2004.Anewgroupof33case historieswasaddedbyIB2010.TheseincludetwentysevencasehistoriescompiledbyIaietal. [21] forthe1983Nihonkai-ChubuEarthquake(M=7.7),threecasehistoriesfromthe1989LomaPrieta Earthquake(Mw =6.93),onefromthe1964NiigataEarthquake(Mw =7.6),onefromthe1968Hyūga-nadaEarthquake(M=6.9),andone fromthe1982Urakawa-OkiEarthquake(M=6.9).Morerecently, BoulangerandIdriss [22] (hereafterBI2014)compiled24additional casesfromthe1999Kocaeli(Mw =7.51)and1999Chi-Chi(Mw = 7.62)earthquakes.

Cetinetal. [4,9] re-evaluatedthese57newcases.Thescreening criteriausedfortheCEA2004wereusedhere,and13ofthenew IB2010andBI2014casehistories(10oftheNihonkai-Chubuand3of theLomaPrietaearthquakecasehistories)satisfiedtheauthors screeningcriteria,andwereaddedtothedatabasepresentedhere. These13newcasesaddedarelistedin Table5.Non-inclusionofthe remainingcasehistoriesisdiscussedinCetinetal. [4,9] andthese exclusionswereconsistentwiththecriteriausedtoassesstheauthors’ originaldatabase:thatis,duetonotmeetingoneormoreofthefollowingscreeningfilters:(1)soilprofiles(e.g.:boringlogs)arenotwell documentedoraccessible,(2)soilpropertiesforthecriticalsoillayer

arenotavailabletoassessplasticity,(3)sitesarenotfree-field,dueto non-leveltopographyorcloseproximityofastructure,and(4)theuse ofpercussiondrillingtechniquesforSPTborings.

2.1.Summaryofchangestothenewdatabase

Theupdateddatabaseisschematicallypresentedin Fig.2,and plottedhereasthemeanvaluesof CSR M , vw andN1,60 foreachcase history,withoutfinescorrections,oradjustmentsforeffectivestress (Kσ)andearthquakemagnitude(KMw).In Fig.2,“Seedetal.”represents casesfromSeedetal. [21].The1995Hyogoken-NanbuEarthquake (“KobeEQ”)casesarefromtheCEA2004database.“Cetinetal.”data pointsrepresenttheremainingcasehistories.Thedatabaseisalso summarizedin SupplementarymaterialTableS1.Acompletediscussionofthecasehistorydatabase,itsbackgrounddocumentation,analysis,andparametricevaluationsareavailableinCetinetal. [4,9] In Table6,thereisacomparativesummaryofkeydatabasestatistics ofSeedetal. [23],CEA2004,Cetinetal. [4,9] andIB2010.While calculatingthesecompositestatisticsforallthreeofthesedatabases(1) liquefied,(2)nonliquefied,and(3)Hyogoken-Nanbu(Kobe)earthquakecasehistorieswereeachweightedindividuallyaswillbediscussedlaterinthismanuscript.Sothecross-comparisonsherearebased onidenticalweightingwithineachdatabase.Asaresult,theparameter ensembleaveragesshownin Table6 arenotbiasedbydifferent

Table1

AssumedunitweightsasusedinCetinetal. [4,9] forbackanalysesoffield performancecasehistoriesunlesscase-specificvaluesareavailable.

(a)Coarse-grainedsoillayers

SPT-N60 γmoist

(blows/ft)(lb/ft3)(kN/m3)(lb/ft3)(kN/m3)

0–4

(b)Fine-grainedsoillayers

weightingschemes,anddirectcross-comparisonsare,therefore, meaningful.

Interestingly,inthecalculationofcyclicstressratios(CSR),the effectoftheaverageincreaseinrd valuesinthenewdatabaseofCetin etal. [4,9],relativetoCEA2004,islargelyoffsetbytheeffectofincreasedunitweighthasontheratioofσv /σ′v.Theeffectofthisoffsetis seeninthefinalplotof Fig.1(j),wheretheupdated CSR M , vw valuesare likelytodecreaseinnearlyasmanycasesasthoseforwhichthereisan increase.

3.Conventionsforanalyzingliquefactionfieldperformancecase histories

Thekeyelementsoftheconventionsandproceduresemployedin theauthors’evaluationofthefieldperformancecasehistoriesforthis studyareessentiallythesameasthoseemployedinCetinetal. [1,2] AdditionaldescriptionsanddetailsareprovidedbyCetin [5] andsome ofthesearealsodiscussedinthecompanionmanuscriptofCetinetal. [24] andCetinetal. [7].

3.1.Casehistoryscreening

Allcasehistoriesusedinthesestudiesarefree-fieldandlevel groundcases.Caseswithgroundslopesgreaterthan3%,orcasesneara freeface(e.g.trench,streamcut,shorelineetc.)wereeliminated.Cases inwhichsoil/structureinteractionmighthavehadapronouncedinfluenceonthecyclicshearstress,orenhancedliquefactiondamage, wereeliminated.Casehistoriescanproduceonlybinaryoutcomes-sites eitherliquefiedornot.Theauthorsmadeexceptionsfortwocasehistorieswheretheperformancewascharacterizedas“marginal”bythe fieldteamthatmadetheobservation.Thereisonlyonesinglemost ‘criticallayer’atanyborehole,anditwasnotallowedtoevaluateboth “liquefied”and“non-liquefied”dataforthesameborehole(orthesame site,ifmultipleboringscharacterizethesamesoilunit),astheonsetof liquefactioninonestratumreducescyclicshearstressesinbothoverlyingandunderlyingstratasuchthatback-analysesforotherlayers becomeunreliable.Thatis,derivinganunbiased“non-liquefied”data

Table2

Reasonsforexclusionofthethreecasehistories.

Casehistory Comments

1975HaichengEarthquake(Ms =7.3),ShuangTaiZi River

1994NorthridgeEarthquake(Mw =6.7),Malden StreetUnitD

1979ImperialValleyEarthquake(ML =6.6),Wildlife UnitB

Lackofdocumentationoffinescontentandsoiltexturelimitsintheoriginalreference.Thisinformationisneededto judgeifthesuspectfinegrainedsoillayerisnon-plasticornot.Seedetal. [12] describedthecriticallayeras"silt"withno furtherdetails.

UnitAisacompactedfill,locatedmostlyabovethewatertable,andisjudgedtobenon-liquefiable;UnitBisafine grainedsoillayerwithN≈2–3blows/ft.,andFC>70%,withaveragePI=18%,andaverageclaycontentof31% (Bennettetal. [13]).ClayeysoilswithPI=18%,werecategoricallyjudgedtobenon-liquefiableinCetin [5] and CEA2004.UnitDisPleistocenesiltysand.However,revisitingthiscasehistorybasedonexchangeswiththeoriginalfield investigators,ithasbeendeterminedthatthesuspectlayerfortheobservedgrounddeformationsisthesoftfine-grained plasticUnitBthataccumulatedpermanentseismicdisplacementsduringthedynamicloadingofcohesivesoils,as proposedandmodeledrecentlybyKayen [14]

Lackofaconfirmedno-liquefactionperformancebyfieldinvestigators.Youd [15] notedthat:“thenoassignedtothe Wildlifesiteforthe1979ImperialValleyEarthquake(M=6.5)wasnotconfirmedbyinvestigatorobservation.”

pointfromotherstrataatasitewhereoneormorestratahaveliquefied, isnotpossible.Compilingmultiplecasehistoriesfromasingleborehole alsohasthenegativeeffectofweakeningthestatisticalindependenceof themaximumlikelihoodformulation.Ateachcasehistorysite,the criticalstratumwasidentifiedasthenon-plastic,submergedsoilsubstratummostsusceptibletotriggeringofliquefaction,andthemiddepthofthecriticalsub-layerwasusedastherepresentativedepth. However,soilpropertieswereassessedwithinthefullthicknessofthe criticalsoillayer.

3.2.EstimationoftheCSR

Peakgroundsurfaceacceleration(amax)valuesforeachcasehistory wereestimatedusingsourcemechanismandgeometry,localandregionalrecordedstrongmotiondata,andsuitesofavailableground motionpredictionequations.Whenavailable,valuesofamax inthe databaseareestimatedasthegeometricmean(GM )ofthetwoorthogonalpeakgroundacceleration(PGA )horizontalcomponents (ie:GMPGAPGA . 12 = )ofmotion.However,ifthegeometricmeanof therotatedsetofcomponentscorrespondingtoppth percentile(i.e.: GMRotDpp)isavailable,asuitableconversionfactorneedstobeapplied.Uncertainty(orvariance)inamax wasevaluatedforeachcaseand isdirectlyreflectiveofthelevelandqualityofdataforeachcasehistory.

For48ofthe210liquefactionfieldperformancecasehistories,insitu CSR M vw wasevaluatedbasedonsite-specificandevent-specific seismicsiteresponseanalyses(usingSHAKE91;IdrissandSun [25]). Fortheremaining162cases,whereinfullseismicsiteresponseanalyses werenotperformed, CSR M , vw wasevaluatedusingtheestimatedamax andEq. (1),withrd-valuesestimatedbyusingthepredictiverd relationshipdevelopedbyCetinandSeed [6,26]

Table3

Reasonsforthemodificationoffourcasehistories.

CaseHistoryID

1989LomaPrietaEarthquake(Mw =6.93),MillerFarmCMF10

Comments

Table4

Comparisonbetweenthemomentmagnitudes(Mw)usedinCEA2004andCetin etal. [4,9]

Earthquake CEA2004Cetin etal. [4,9]

1948Fukui 7.307.00

Ref.

1944Tohnankai8.008.10USGSCentennialEarthquake Catalog,EngadhlandVillasenor [17]

1968Tokachioki7.908.30

1975Haicheng7.307.00

1976Tangshan8.007.60

1977Argentina7.407.50

1978Miyagiken-Oki Feb.20 6.706.50

1978Miyagiken-Oki June12 7.407.70

1990Luzon 7.607.70

1979ImperialValley6.506.53NGAFlatfiles [18]

1987Superstition Hills 6.706.54

1989LomaPrieta7.006.93

1964Niigata 7.507.60IncorporatedResearch InstitutionsforSeismology (IRIS)SeismoArchives [19]

1993Kushiro-Oki8.007.60IdeandTakeo [20]

InEq. (3),asdefinedearlier,amax isthepeakhorizontalground surfaceacceleration;gistheaccelerationofgravity,σv andσ′v aretotal andeffectiveverticalstresses,respectively,andrd isthestressreduction ornonlinearshearmassparticipationfactor.Afullexplanationofthe developmentoftheprobabilisticrd relationshipispresentedinCetin andSeed [6,24].Intotal,2153one-dimensionalseismicsiteresponse

AtthetimeofCetin [5] andCEA2004studies,theClintMillerFarmCMF-10casehistorysitewasclassifiedasa liquefiedsite.TheCMF-10boreholewaslocatedinasuiteoftestsacrossapermanentdeformationtransition zoneanditisnowunderstoodthatthefieldinvestigationteam(Wayneetal. [16])intendedCMF-10torepresent thenon-liquefiedzone.Theauthorsacceptthefieldjudgmentsofthefieldinvestigationteams.

1995Hyogoken-NanbuEarthquake(Mw =6.9),Kobe#6Thissitewasfoundtobeinconsistentlylistedasanon-liquefiedandaliquefiedsiteonthesummarytableandthe map,respectively,fromtheKobeCityOfficein1999.AfterpersonalcommunicationwithProf.Tokimatsu,the siteisupdatedasa"non-liquefied"site.

1995Hyogoken-NanbuEarthquake(Mw =6.9),Kobe#16DuetotheproximityofKobe#15(Liquefied)and#16(Non-Liquefied)sites,Kobe#16wasoriginallyclassified asamarginalliquefaction(Yes/No)site.Nowitistreatedasanon-liquefiedsite.

1993Kushiro-OkiEarthquake(Mw =7.6),KushiroPort strongmotionrecordingstation

WhentheCEA2004databasewascompiled,thesiltylayeratthedepthrangeof20–22mwithSPT-Nvaluesof 6–10blows/ftwasjudgedtobethesuspectstratum.However,afterhavingrevisitedthiscasehistory,thesuspect stratumwasidentifiedas"mediumdense"coarsesandsoillayerwithSPT-Nvaluesof16–18blows/ftatthe depthrangeof2.8–5.2m.Thiscasehistoryisjudgedtowarrantfurtherindepthinvestigation.Meanwhile,this shallower"mediumdense"coarsesandsoillayerisusedasthecriticallayer.

Table5

Listof13additionalfieldperformancecasehistoriesfromIB2010thatwere addedtoCetinetal. [4,9] database.

1983Nihonkai-ChubuM=7.7 Earthquake 1989LomaPrietaMw =6.93 Earthquake

1.AkitaStation

2.Gaiko1&2

3.Hakodate

4.NakajimaNo.1(5)

5.NakajimaNo.2(1)

6.NakajimaNo.2(2)

7.NakajimaNo.3(3)

8.NakajimaNo.3(4)

9.OhamaNo.2(2)

10.OhamaNo.Rvt.(1)

1.GeneralFish

2.MarinaLaboratory_F1-F7

3.MBARINO.4-B4B5EB2EB3

Fig.2. SummaryoftheCetinetal. [4,9] fieldperformancecasehistorydata.

Table6

Fig.3. Plotsofrd forall2153siteresponseanalysesforallcombinationsofsites andinputmotionssuperimposedwiththepredictionsbasedongroupmean valuesofVs,Mw,andamax (Heavyblacklinesshowregressedmeanand±1 standarddeviations)(takenfromCetinandSeed [6]).

analyseswereperformedinordertogeneratethedatasetforprobabilisticregressions. Fig.3 showstherd curvesforallofthesesiteresponseanalyses.

Theconsistentuseofrd relationshipofCetinandSeed [6,26] is presentedonanillustrativeseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringassessmentprobleminCetinetal. [7];hencewillnotberepeatedherein.

Theprobabilisticregressionsindicatethattheharderasoilcolumn isshaken,andthesofterthecolumnis,thegreaterthedegreeofnonlinearityofresponsethatresults,suchthatrd valuesdecreasemore rapidlywithincreasingdepth.Increasedheterogeneityordistinct “layering”ofthesiteconditionstendstobreakupwavecoherence,and alsotendstocauserd valuestodecreasemorerapidlywithincreasing depth.Increasedmagnitudeservesasaproxyforduration,andisthe leastsignificantofthefourfactors.ThepredictiverelationshipofCetin andSeed [6,26] isintendedtobeusedonsoilprofileswithpotentially liquefiablelayersanditisrecommendedbytheauthorsthatanupper boundofVS,12m ≤230m/sbeemployedinforwardanalysessoasnot

Summaryandcomparisonofoverallcasehistoryweightedaverageinputparameters.

a Functionsofregressedlikelihoodmodelcoefficients,aspresentedlaterinthismanuscript.

toproducenearlyrigidbodytyperesponsepredictions.Theshearwave velocityvalueof230m/sforVS,12m iscoincidentwiththezoneof highestvaluesofVS1 foundtohaveliquefiedinthedatabaseofKayen etal. [27].Similarly,forunusuallysoftsiteswithVS,12m ≤90m/s,rd relationshipofCetinandSeed [6,26] canbeemployed,thoughthat lowervalueofaverageshearwavevelocitycorrespondswiththevery lowestVS1 reportedinKayenetal. [27].Nositeexistswithconditions ofVS,12m lessthan90m/sorabove230m/sinanyoftheliquefaction databases,thoughthesestudiesrepresentthevastmajorityofwell documentedfield-performancesites.VS,12m isestimatedbycalculating theapparenttraveltimesthrougheachsub-layer,downtoadepthof12 m,andthenbydividingthetotaldistance(i.e.:12m)bythetotaltravel time.AdetaileddiscussiononconsistentestimationofVS,12m ispresentedinCetinetal. [7] byanillustrativeseismicsoilliquefaction triggeringassessmentproblem;hencewillnotberepeatedherein.

Theseapproacheswereemployedtodevelopunbiasedbest-estimatesofrd,anditsvariance.Assuch,theresultingliquefactiontriggeringrelationshipscanbeusedinforwardengineeringanalyseswith eitherrd relationshipofCetinandSeed [6,26],orsite-specificseismic siteresponseanalyses.Factorscontributingtooverallvarianceinestimationoftheequivalentuniformcyclicshearstressratio(CSR M , vw ) weresummedwithinastructuralreliabilityframework.Themain contributorstothisvariancewere(1)uncertaintyinamax,and(2)uncertaintyinnonlinearshearmassparticipationfactor(orrd).Other variables,whichcontributedtoalesserdegreetotheoverallvariance werethedepthofthecriticalsoilstratum,soilunitweights,andlocationofthephreaticsurface(“watertabledepth”)atthetimeofthe earthquake.

3.3.EstimationofSPT-Nvalues

Somecasehistorieshavecriticallayerscharacterizedwithonlya singleSPTboring,whileothershavedenseconcentrationscharacterizedfrommultipleSPTborings.Thisstudyassignedasinglecasehistorytothetotalnumberofboringsatthesamesitethatcouldbe groupedtogethertojointlydefineastratum.CaseswithmoreSPTdata usuallyhaveloweruncertaintiesintheirN-values.Thesecasesexert moreweightonthelocationofthetriggeringcurvesthanlesswellcharacterizedcaseswithhigheruncertainty.

TheresultingN1,60 valuesaretheproductoftheaveragedNvalues forastratumcorrectedforeffectivenormalstress(CN),hammerenergy (CE),equipmentrodlength(CR),equipmentsampler(CS),borehole diameter(CB),andproceduraleffectstofullystandardizedN1,60 values asgiveninEq. (2)

NCCCCC N····· 1,60NRSBE = (2)

ThecorrectionsforCN,CR,CS,CB andCE correspondcloselytothose recommendedbytheNCEERWorkingGroup(NCEER [28],andYoud etal. [29]),andarediscussedinCEA2004andCetinetal. [4,7];hence willnotberepeatedherein.Intheliteraturethereexistalternative correctionschemesregardingthesefactors(e.g.effectivestressonlyor effectivestressandrelativedensitydependentCN (LiaoandWhitman [30],Boulanger [31],etc.)orrodlength(NCEERworkshopproceedings [28],CEA2004,SancioandBray [32],etc.).However,duetolackof consensusamongthesecorrectionschemes,andduetotheirrelative insignificanceontheoverallcorrectedSPTblowcounts,NCEER workshopconsensusrecommendationisadopted.Foreffectivestress rangesexceeding2atm,whichisoutsidethelimitsofcasehistorybasedliquefactiontriggeringmodels,thedifferencesbetweeneffective stressonly-,andeffectivestress-relativedensitydependent-CN correctionschemescanbesignificant.Hence,theireffectsontheestimated N1,60 valuesshouldbecarefullyandcasespecificallyassessed.For furtherdiscussionregardingthesecorrectionfactorsrefertoNCEER WorkshopProceedings [28],Youdetal. [29],CEA2004andCetinetal. [4,9]

For20outof210caseswhereinthecriticalstratumhadonlyone

singleusefulN1,60-value,thestandarddeviationwastakenas2blows/ft because2blows/ftwastypicalofthelargervariancesamongthecases withmultipleN1,60 valuesregardlessofthevalueofthemeanblowcount.

4.Developmentofprobabilisticliquefactiontriggeringcurves

Liquefactiontriggeringcorrelationsweredevelopedbasedon probabilistic“regressions”performedemployingthemaximumlikelihoodestimation(MLE)method.Theformulationsandapproaches employedaredescribedindetailbyCetin [5],Cetinetal. [4,33],and hereonlybriefly.TheMLEservesessentiallythesamepurposeasmultidimensionalprobabilistic“regression”analyses,but(1)allowsforseparatetreatmentofvariouscontributingsourcesofaleatoryuncertainty,and(2)facilitatestreatmentofmoredescriptivevariables (modelparameters)whilealsopermittingthemonitoringofmodel parameterinteractionsandco-variances.WithintheMLEanalyses,all data(i.e.:CSR,N1,60,σ′v,FC,Mw)weremodeledasrandomvariables. Thus,thepointsin Figs.1and2 areactuallythemeanvaluesofuncertaintycloudsinallparametricdirectionsforeachcasehistory.

Allliquefactiondatabaseshaveasamplingdisparitythatbiasesthe datasettowardliquefiedsitesandisduetotheundersamplingof nonliquefiedsites.Cetinetal. [1,2,33] proposedaproceduretobalance thedatasetbyup-weightingthevalueofnon-liquefiedsitesbya weightingfactorof1.2,andbydown-weightingthevalueofliquefied sitesbyafactorof0.8.Thisisapproximatelyequivalenttosimplyupweightingthenon-liquefiedcasesbyafactorof1.5.However,partitioningtheweightingfactorsamongbothliquefiedandnon-liquefied casesallowsimprovedtreatmentofmodeluncertainty.

TheCetinetal. [4,9] databasehasnearlythesameoverallcharacteristics(andalmostthesamecases)astheCEA2004database,and thesameweightingfactors(1.2and0.8)wereagainappliedtoliquefied andnonliquefiedcasehistories.Anadditionalweightingfactorwas neededtoaddressthelargenumberofcasehistoriesfromthe1995 Hyogoken-Nanbu(Kobe,Japan)earthquake.Thedatabasehas56case historiesfromthissingleevent;andthatverylargenumberresultsinan unbalanceoftheoveralldatasetwhereinthatsingleeventisover-represented.ThiswasaddressedintheassessmentsperformedforCetin etal. [4,9] databasebydown-weightingtheHyogoken-Nanbu(Kobe) earthquakecasehistoriesbyaweightingfactorof0.25.Additional detailsoftheassessmentsperformedarepresentedinCetinetal. [4,9].

Themaximumlikelihoodapproachbeginswiththeselectionofa mathematicalmodel.Themodelforthelimit-statefunctionhasthe generalform gg x (,) = ,where NCSRMFC x (, ,,,) Mwv 1,60,,vw = isa setofdescriptivevariablesand isthesetofunknownmodelcoefficients.Consistentwiththenormaldefinitionoffailureinstructural reliability,liquefactionisassumedtohaveoccurredwhen g x (,) takes onanegativevalue.Thelimit-statesurface g x (,)0 = denotesthe50percentile(median)boundaryconditionbetweenliquefactionand nonliquefaction.ThefollowingmodelfromCetinetal. [2,33] isused forthelimitstatefunction:

isthesetofunknownmodelcoefficients.

ThelimitstatefunctiongiveninEq. (3) hastheadvantageofassessingKσ,KMw andfinescorrectionswithinaunifiedframework. Hence,aspartofthemaximumlikelihoodassessment,theoverallliquefactiontriggeringrelationshipisassessedjointlywithrelationships forthesecorrectionsfactors.Eq. (3) assumesthattheliquefaction triggeringhazardcanbecompletelyexplainedbyasetoffivedescriptivevariables NCSRMFC x (, ,,,) Mwv 1,60,,vw = .Butothervariablesexist,whichmayinfluencetheinitiationofliquefaction.Evenif theselecteddescriptivevariableswereabletofullyexplainthe

liquefactiontriggeringphenomenon,theadoptedmathematicalexpressionmaynothavetheidealform.Hence,Eq. (3) isbydefinitionan imperfectmodelofthelimit-statefunction.Thisissignifiedbytheuse ofasuperposed"hat"on g .Toaccountfortheinfluencesofpossible missingvariablesandthepossibleimperfectmodelform,arandom modelerrorterm, ε,wasintroducedasgiveninEq. (4).

Withtheaimofproducinganunbiasedmodel(i.e.,onethat,onthe average,makesthecorrectprediction),themeanof issettozero,and forconvenienceitisassumedtobenormallydistributed.Thestandard deviationof ,denoted ,howeverisunknownandmustbeestimated aspartoftheregression.Thesetofunknowncoefficientsofthemodel, therefore,is (,) = .

Let xNCSRMFC(,,,,) i i Miwiivi 1,60, vw = bethevaluesof N1,60, CSR, Mw, FC and v forthe ithcasehistory,respectively,and i bethe correspondingrealizationofthemodelcorrectionterm.Ifthe ithcase historyfieldperformanceisliquefied,then gx(,,)0 ii .Ontheother hand,ifthe ithcasehistoryfieldperformanceisnonliquefied,then gx(,,)0 ii > .When gx(,,)0 ii thenthecasehistoryisdefinedas marginallyliquefied(ormarginallynonliquefied).Assumingthatthe Cetinetal. [4,9] databaseiscompiledfromstatisticallyindependent liquefactionfieldperformancecasehistories,thelikelihoodfunction canbewrittenastheproductoftheprobabilitiesoftheobservations giveninEq. (5).

Num.ofliquefiedsites 1

L Pgx Pgx Pgx ( ,) [(,, )0] [(,, )0] [(,, )0] l ll j jj k kk 1

Num.ofmarginallyliquefiedsites = > = = = (5)

Num.ofnonliquefiedsites 1

Supposethat NCSRMFC x (, ,,,) i i Miwi i vi 1,60, vw = foreachliquefactionfieldperformancecasehistoryisexact,i.e.,nomeasurement orestimationuncertaintyispresent.Then,notingthatEq. (4) hasthe

correctionfactors0.8and1.2,respectively. If NCSRMFC x (, ,,,) i i Miwi i vi 1,60, vw = isinexact(uncertain), thenthisadditionaluncertaintyshouldbeincludedintheformulation ofthelikelihoodfunctionasgiveninEq. (7)

L gx gx gx (,) (,) (,) (,) i toti w i toti w i toti liquefiedsites ,, nonliquefiedsites ,,

marginallyliquefiedsites ,, liq nonliq = (7)

Assumingthatthemeanvaluesofthecasehistorydescriptiveinput parameters NCSRMFC , ,,, i Miwi i vi 1,60, ,,,, , vw areestimatedinanunbiasedmanner(i.e.,meanchoices,ratherthanconservativeorunconservativechoices,aremadeincasehistoryprocessing)thenthe errortermsof NCSR MFC ,ln( ),ln(),,ln() i Miwi i vi 1,60, ,,, , , vw canbe consideredasnormallydistributedrandomvariableswithzeromeans andstandarddeviations Ni 1,60 , CSRiln( ), v Mw ,, , Miln(), w , FCi and i ln(), v , respectively.Thentheoverallvarianceofeachliquefactionfieldperformancecasehistory(σ2tot)isestimatedasthesumofthevarianceof casehistoryinputparameters(σ2case-history)andmodelerror(σ2 є )asgiven inEq. (8)

( ) toti casehistoryi , 2 7 , 2 2 = + (8)

InEq. (8), casehistoryi , representstheconsolidateduncertaintyof individualcasehistoryinputparameters,andasdiscussedearliera scalingfactorof 7 issystematicallyappliedtothem.Thisfactor( 7 )is oneoftheregressedparametersoftheoveralltriggeringrelationship.If thehigher-ordertermsareeliminated,then casehistoryi , canbeestimated asgivenEq. (9).

[ ] CSR FC N ()cov( ) (1) ( )()[cov()] casehistoryi Mi N iFC i vi , 2 6 2 ,,, 2 2 1 22 11,60,4 2 3 2 2 vw i i 1,60, =

(9)

normaldistributionwithmean gx ˆ (,) i andstandarddeviation ,the likelihoodfunctionEq. (5) canbewrittenasgiveninEq. (6)

L gx gx gx (,) (,) (,) (,) l w j w k liquefiedsites nonliquefiedsites

marginallyliquefiedsites liq nonliq = (6)

InEq. (6), [] and [] arethestandardnormalcumulative functionandthestandardnormalprobabilitydensityfunctions,respectively.Alsonotethatwliq andwnonliq arethesamplingbias

Finally,theeightmodelcoefficients(i.e.: 1 through 7 ,and )are assessedsimultaneouslyinasingleoverallregressioninordertomaximizethelikelihoodfunctionpresentedinEq. (9).Theresulting(new) recommendedseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringrelationshipsare presentedinEqs. (10)and(11) andthenewmodelcoefficientsare listedin Table7 alongwithCEA2004modelcoefficientsforcomparison purposes.

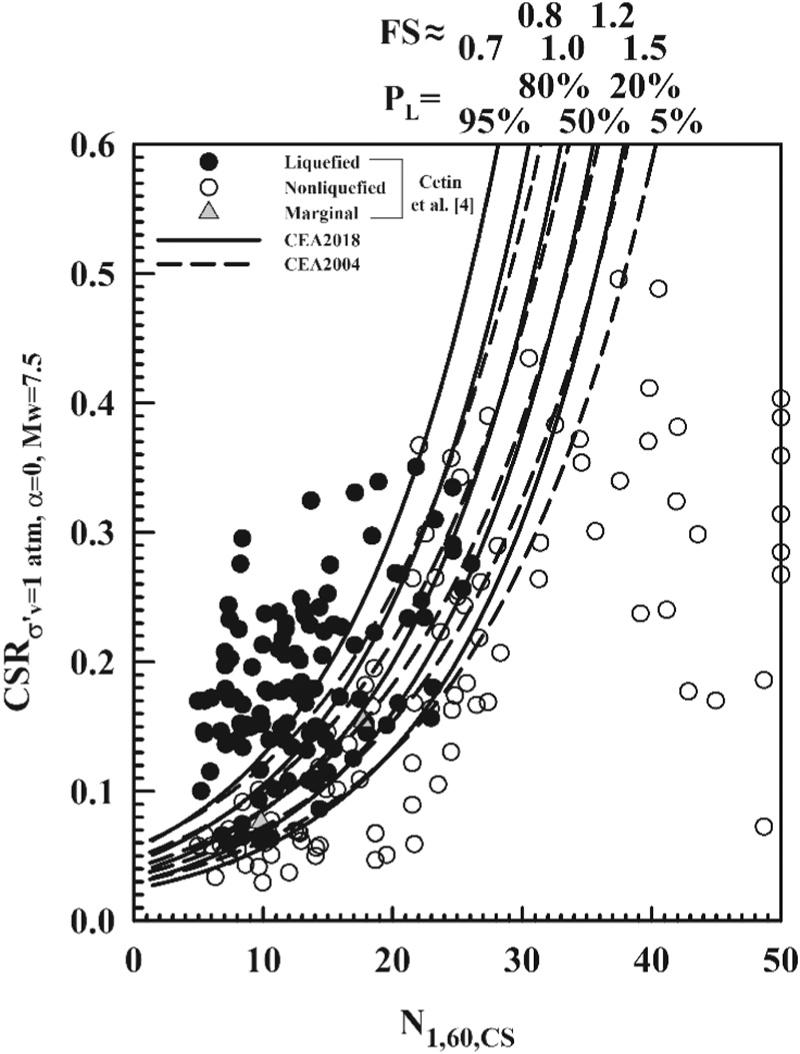

Thenewprobabilisticboundarycurvesareshownin Fig.4 Fig.5 presentsadirectcomparisonbetweenthenewtriggeringrelationship andthepreviousrelationshipofCEA2004.ThesenewtriggeringrelationshipswillbereferredtoasCEA2018,hereafter.

InEq. (10),PL istheprobabilityofliquefactionindecimals(i.e.PL =30%isinputas0.30), CSR M ,0, vw isnot“adjusted”forvertical overburdenstressormagnitude/durationeffects(correctionsareexecutedwithintheequationitself),FCispercentfinescontent(bydry weight)expressedasaninteger(e.g.:12%finesisinputasFC=12) withthelimitof5≤FC≤35,Pa isatmosphericpressure(1atm=

Table7 Acomparativesummaryoflimitstatemodelcoefficients.

101.3kPa=2116.2psf)inthesameunitsasthein-situverticaleffectivestress(σ′v),and Φ isthestandardcumulativenormaldistribution.Thecyclicresistanceratio,CRR,foragivenprobabilityofliquefactioncanbeexpressedasgiveninEq. (11),where Φ−1(PL)istheinverseofthestandardcumulativenormaldistribution(i.e.mean=0,andstandarddeviation=1).Forspreadsheet constructionpurposes,thecommandinMicrosoftExcelforthisspecific functionis“NORMINV(PL,0,1)”.In Figs.4and5,factorofsafety(FS) valuescorrespondingtoprobabilityofliquefaction5%,20%,50%, 80%,95%arealsoshown.Approximatefactorsofsafety,FSvaluescan beestimatedbyEq. (12) basedontheassumptionthatPL valueof50% correspondstoabest-estimatefactorofsafetyvalueequalto1.0and theresultingFSvaluesforthefivesetsofPL contoursarealsoshownin Figs.4and5

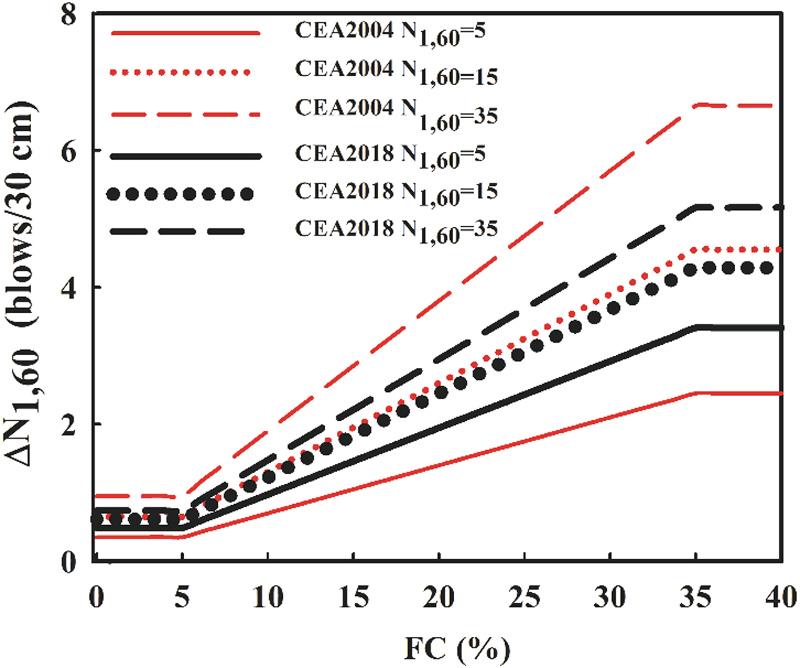

tworelationshipsaresimilar,andthenewfinescorrectionrelationship hasalesserdependenceuponN1,60

Similarly,in-situequivalentuniform CSR M ,, vw canbeevaluated eitherbasedon(1)directseismicsiteresponseanalyses,or(2)direct seismicsiteresponseandsoil-structure-interactionanalyses,or(3) usingthe"simplified"approachemployingEq. (1),andtheCetinand Seed [6] rd relationships.

CSR M vw isthenadjustedbythe K , K and K Mw correctionfactors toconvertoverburdenandstaticshearstresses,andduration(magnitude)tothereferencesstatesof 1atm v = , 0 = andMw =7.5,as giveninEqs. (13)–(15).Notethatforlevelsites(whichincludesallfield performancecasehistoriesinthedatabase)thevalueof K =1.0.

111

CSR CSR KKK lim

Forthepurposeofassessingtheeffectsofsamplingdisparity(and weighting),thesameexercisewasthenrepeated,butthistimewithout applyingweightsonnon-liquefiedandliquefiedcasehistorydata points. Fig.6 presentstherelativepositionsofequi-probability(5%, 20%,50%,80%and95%)liquefactiontriggeringcontourswith(solid lines)andwithouttheweightingfactors(dashedlines).Sinceitwould bepotentiallyover-conservativetoleavethesamplingdisparityproblemunaddressed,themodeldevelopedwithweightingfactorsof w 1.2 nonliquefied = and w 0.8 liquefied = isrecommendedforforwardengineeringassessments.

5.Recommendeduseofthenewcorrelations

Theproposednewprobabilisticcorrelationscanbeusedintwo ways.Theycanbeuseddirectly,allatonce,assummarizedinEqs. (10) and(11).Alternatively,theycanbeused“inparts”ashasbeenconventionalformostprevious,similarmethods.Theuseofbothofthe alternativesinseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringassessmentsispresentedinCetinetal. [7] foranillustrativeseismicsoilliquefaction triggeringassessmentofasoilsiteshakenbyascenarioearthquake.The protocols,whichneedtobefollowed,aswellastherecommendations whichguidestheengineersthroughtheprocedureand“tricks”forthe correctuseofthemethodologyforforwardengineering(design)assessmentsarediscussedinthesubjectmanuscript.Hence,thereaders arereferredtoCetinetal. [7] fortheconsistentuseofthemethodology, meananduncertaintyestimationsofinputparameters:i.e.:SPTblowcountalongwithFinesContentdata,CSRanditsinputparametersof maximumgroundacceleration,stressreduction(massparticipation) factorrd,momentmagnitude,verticaleffectiveandtotalstresses.

“In-part”useoftheproposedseismicsoilliquefactiontriggering relationshipsrequiretheapplicationoffines,stressandmagnitude correctionfactors(K and K Mw ). Fig.7 showstheregressedfinescorrectionsforthesecurrentstudies,andalsofortheprevioustriggering relationshipsofCEA2004.Theoverallaveragefinescorrectionsforthe

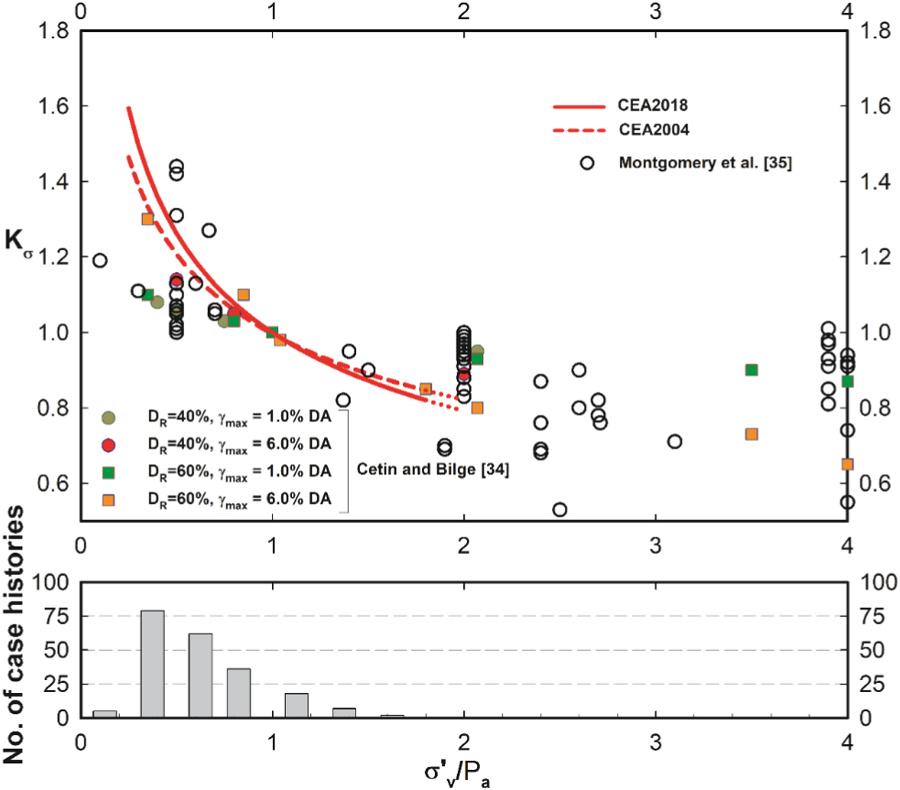

AsanalternativetoEqs. (14)and(15), K and K Mw correctionscan beemployedbyusing Figs.8and9.

Fig.8 showsthenew K curveregressedfromtheliquefaction performancefieldcasehistorydatabase,andthelowerportionof Fig.8 showsahistogramofthedistributionofcasehistorieswithdifferent rangesofσ'v.Thisfieldcasehistory-based K relationshipisvalidover therangeofapproximately0.25atm≤σ'v ≤1.8atm.Extrapolationto highervaluesofσ'vforforwardengineeringanalysesisdiscussedinthe companionpaperofCetinetal. [24].

Thenew K curveisobservedtobelargelyconsistentwiththe CEA2004recommendations,whichwerealsobasedonregressionsof fieldperformancecasehistories,andatleastapproximatelyalsofits laboratorycyclicsimplesheartestresultsofCetinandBilge [34] andis similartoadatasetofcyclictriaxialandcyclicsimplesheardata

Fig.4. Newprobabilisticseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringcurves.

Fig.5. ComparisonbetweenthetriggeringboundarycurvesofCEA2004and thesecurrentstudies.

Fig.6. Effectsofimplementingcompensationforsamplingdisparity(solid lines)vs.leavingsamplingdisparityunaddressed.

collectedandcompiledbyMontgomeryetal. [35].Intheliterature, therealsoexistalternative K relationshipswhichweredevelopedon thebasisofcycliclaboratorytestdata(e.g.Vaidetal. [36],Hynesand Olsen [37],Boulanger [31],CetinandBilge [34],etc.).Asdiscussedin therecentstateoftheartreportofNAP [3] boththecasehistoryor laboratorytestdatabased K frameworksarejudgedtobetechnically validandtheiruseforthestressnormalizationofhigheffectivestress casehistoryCSRvaluestotheCSRvaluesatthereferencestateof1atm verticaleffectivestress,ispossible.

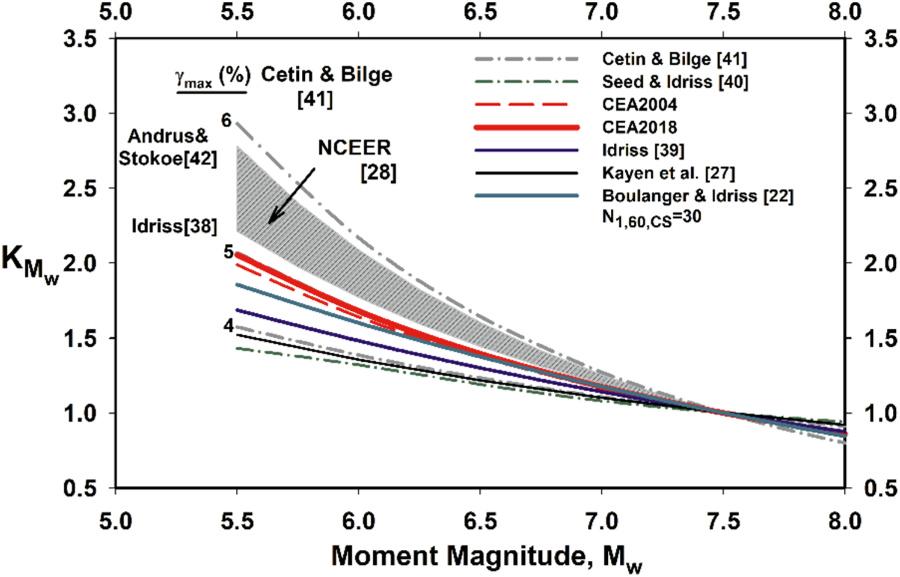

Fig.9 presentsthenew K Mw curve,whichwasalsodevelopedbased

ProposedN1,60 dependentfinescorrection.

ontheoverallregressionoftheliquefactiontriggeringfieldperformancecasehistorydatabase.Itagreeswellwiththerelationshipof CEA2004,whichwasalsobasedonregressionoffieldcasehistories, anditisboundwithinthefield K Mw lower-boundofNCEER [28] (the upperboundcurveofAndrusandStokoe [42] isalsopresentedon Fig.9),thelaboratoryrelationshipsofIdriss [38,39] andBoulangerand Idriss [22],andtheshearwavevelocity–basedrelationshipsofKayen etal. [27].Agreementbetweenthese,SeedandIdriss [40],andCetin andBilge [41] K Mw relationshipsdevelopedbasedondifferentsetsof approachesisrelativelygood.

Theresulting,fullyadjustedandnormalizedvaluesofN1,60,cs and CSR M 1atm,0,7.5 v w === canthenbeused,with Fig.4,toassesstheprobabilityofinitiationofliquefaction.For“deterministic”evaluationofliquefactionresistanceEq. (12) canbeusedtoapproximateanacceptable factorofsafety.

6.Conclusions

ThepreparationofthereportbytheNationalAcademiesof Sciences,Engineering,andMedicineonthe“StateoftheArtand PracticeintheAssessmentofEarthquake-InducedSoilLiquefactionand ItsConsequences”providedtheauthorsthemotivationandimpetusto updatetheSPT-basedrelationshipofCEA2004andcastanewprobabilistictriggeringrelationshipbasedupontheupdatedfielddatabase. Newprobabilisticanddeterministicliquefactiontriggeringcurvesare proposedbasedonthemostrecentcasehistorydatabaseofCetinetal.

Fig.8. Newlyregressed K correctionscomparedwithavailablecycliclaboratorytestdata.

Fig.9. Newlyregressed K Mw correctionscomparedwithavailableliterature.

[4,9].Maximumlikelihoodmodelsforassessmentofseismicsoilliquefactioninitiationarepresented,andintheirdevelopmenttherelevantuncertaintiesincluding(a)measurement/estimationuncertaintiesofinputparameters,(b)limitstatemodelimperfection,(c) statisticaluncertainty,and(d)uncertaintiesarisingfrominherent variabilitywereaddressed.

Theuseofsite-specificandevent-specificseismicsiteresponsebasedcalculationsofCSR,andofcompatibleunbiased(median) probabilisticrd relationshipsbasedonrepresentativesuitesofsite conditionsresultsintriggeringrelationshipsthatarethereforeunbiased withrespecttouseinconjunctionwitheither(1)directseismicsite responseanalyses,orsiteresponseandsoil-structureinteractionanalyses,forevaluationofin-situCSR,or(2)improved“simplified”assessmentofin-situCSRinforwardengineeringanalyses.

Thenewmodelsprovideanimprovedbasisforengineeringassessmentofthelikelihoodofliquefactioninitiation.Theproposedmodels dealexplicitlywiththeissuesof(1)finescontent(FC),(2)magnitude (duration)effects(i.e.: K Mw correction),and(3)effectiveoverburden stresseffects(i.e.: K correction).Thesecorrectionfactorrelationships arealldevelopedbasedonregressionoftheentirefieldcasehistory database.Asaresult,theoveralltriggeringrelationshipsprovideboth (1)anunbiased(median)basisforevaluationofliquefactioninitiation hazard,and(2)abasisforassessmentofoverallmodeluncertainty. Overalluncertaintyinapplicationofthesenewcorrelationstofield problemsisdrivenbythedifficulties/uncertaintiesassociatedwith project-specificengineeringassessmentofthe“loading”and“resistance”variables.Intheestimationoftheseloadingandresistance terms,theneedtouseaseriesofcorrectionsandnormalizationsremainsattheheartofthetriggeringassessment.Theobjectiveofthis updatedsetofcorrelationsistoprovideanunbiasedsetofliquefaction triggeringrelationships,normalizedatσ'v =1atm,MW =7.5andα= 0.Theserelationshipsarerecommendedtobeusedforeitherprobabilisticordeterministicassessmentofseismicsoilliquefactiontriggering.Theuseofthembeyondtheirrecommendedlimitsbysimple extrapolationtechniqueswithoutadditional,projectspecificengineeringassessmentsand/orlaboratorytesting-basedconfirmations mayleadtounconservativelybiasedpredictions;henceitisstrongly discouraged.

Acknowledgements

Theauthorsaredeeplygratefultothemanyengineersandresearcherswhodevelopedthefieldcasehistorydatauponwhichthese typesofcorrelationsarebased.Wearealsogratefultothemanyengineers,colleaguesandouranonymousReviewers,whoencouraged thiscurrentwork,andwhosediscussionsandcommentswereofgreat value.

AppendixA.Supplementarymaterial

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefoundinthe onlineversionat doi:10.1016/j.soildyn.2018.09.012

References

[1]CetinKO,SeedRB,MossRES,DerKiureghianAK,TokimatsuK,HarderLF,etal. FieldperformancecasehistoriesforSPT-basedevaluationofsoilliquefactiontriggeringhazard,(GeotechnicalResearchReportNo.UCB/GT-2000/09)Berkeley,CA: Dept.ofCivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley; 2000.

[2] CetinKO,SeedRB,DerKiureghianA,TokimatsuK,HarderJrLF,KayenRE,etal. SPT-basedprobabilisticanddeterministicassessmentofseismicsoilliquefaction potential.ASCEJGeotechGeoenvironEng2004;130(12):1314–40

[3]NAP.Stateoftheartandpracticeintheassessmentofearthquake-inducedsoil liquefactionanditsconsequences.NationalAcademiesofSciences,Engineering, andMedicine;Washington,DC:TheNationalAcademiesPress;2016.〈https://dx. doi.org/10.17226/23474〉.

[4]CetinKO,SeedRB,KayenRE,MossRES,BilgeHT,IlgacM,etal.SummaryofSPTbasedfieldcasehistorydataoftheupdated2016Database.(Reportno:METU/ GTENG08/16-01)METUSoilMechanicsandFoundationEngineeringResearch Center;2016.

[5]CetinKO.Reliability-basedassessmentofseismicsoilliquefactioninitiationhazard. Dissertationsubmittedinpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementforthedegreeof DoctorofPhilosophy,UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley;2000.

[6] CetinKO,SeedRB.Nonlinearshearmassparticipationfactor,rd forcyclicshear stressratioevaluation.SoilDynEarthqEngJ2004;24(2):103–13

[7] CetinKO,SeedRB,KayenRE,MossRES,BilgeHT,IlgacM,etal.TheuseoftheSPTbasedseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringevaluationmethodologyinengineering hazardassessments.MethodsX2018.[Inpreparation]

[8]JapanRoadAssociationDesignSpecificationsforHighwayBridges;2002.

[9] CetinKO,SeedRB,KayenRE,MossRES,BilgeHT,IlgacM,etal.DatasetonSPTbasedseismicsoilliquefaction.DataBrief2018;20:544–8.Elsevier

[10]IdrissIM,BoulangerRW.SPT-basedliquefactiontriggeringprocedures.(Report UCD/CGM-10/02)Davis,CA:CenterforGeotechnicalModeling,Departmentof CivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofCalifornia;2010.p.136.

[11] IdrissIM,BoulangerRW.ExaminationofSPT-basedliquefactiontriggeringcorrelations.EarthqSpectra2012;28(3):989–1018

[12]SeedHB,TokimatsuK,HarderLF,ChungRM.TheinfluenceofSPTproceduresin soilliquefactionresistanceevaluations.(EarthquakeEngineeringResearchCenter ReportNo.UCB/EERC-84/15)Berkeley,CA:Dept.ofCivilandEnvironmental Engineering,UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley;1984.

[13]BennettMJ,PontiDJ,TinsleyJC,HolzerTL,ConawayCH.Subsurfacegeotechnical investigationsnearsitesofgrounddeformationscausedbythe17January1994 NorthridgeCaliforniaEarthquake.(OpenFileReport1998).DepartmentofInterior U.S.GeologicalSurvey,p.98–373.

[14]KayenR.Seismicdisplacementofgently-slopingcoastalandmarinesedimentunder multidirectionalearthquakeloading.EngGeol2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enggeo.2016.12.009

[15] YoudTL.Discussionof“examinationandreevaluationofSPT-basedliquefaction triggeringcasehistories”byRossW.Boulanger,DanielW.Wilson,andI.M.Idriss.J GeotechGeoenvironEng2013;138(8):898–909

[16] WayneAC,DonaldOD,JeffreyPB,HassenH.Directmeasurementofliquefaction potentialinsoilsofMontereyCounty,California.In:HolzerTL,editor.TheLoma Prieta,California,EarthquakeofOctober17,1989:Liquefaction.WashingtonD.C: U.S.GovernmentPrintingOffice;1998.p.B181–208

[17]EngadhlER,VillasenorA.Globalseismicity:1900–1999.Internationalhandbookof earthquakeandengineeringseismology.InternationalAssociationofSeismology andPhysicsoftheEarth'sInterior,CommitteeonEducation;81A;2002.p.665–90.

[18]NGAFlatfiles.〈http://peer.berkeley.edu/ngawest2/databases/〉;2015.

[19]IncorporatedResearchInstitutionsforSeismology(IRIS)SeismoArchives,〈http:// ds.iris.edu/seismo-archives/〉;2004.

[20] IdeS,TakeoM.Thedynamicruptureprocessofthe1993Kushiro-okiearthquake.J GeophysRes1996;101(B3):5661–75

[21] IaiS,TsuchidaH,KoizumiK.Aliquefactioncriterionbasedonfieldperformances aroundseismographstations.SoilsFound1989;29(2):52–68

[22]BoulangerRW,IdrissIM.CPTandSPTbasedliquefactiontriggeringprocedures. (ReportNo.UCD/CGM-14/01).Davis,CA:CenterforGeotechnicalModeling, DepartmentofCivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofCalifornia;2014. p.134.

[23] SeedHB,TokimatsuK,HarderLF,ChungRM.TheinfluenceofSPTproceduresin soilliquefactionresistanceevaluations.JGeotechEngASCE 1985;111(12):1425–45

[24] CetinKO,SeedRB,KayenRE,MossRES,BilgeHT,IlgacM,etal.Examinationof differencesbetweenthreeSpt-basedseismicsoilliquefactiontriggeringrelationships.SoilDynEarthqEng2018;113:75–86.Elsevier

[25]IdrissIM,SunJI.User’smanualforSHAKE91,acomputerprogramforconducting equivalentlinearseismicresponseanalysesofhorizontallylayeredsoildeposits programmodifiedbasedontheoriginalSHAKEprogrampublishedinDecember 1972bySchnabel,LysmerandSeed;1992.

[26]CetinKO,SeedRB.Earthquake-inducednonlinearshearmassparticipationfactor (rd).(GeotechnicalResearchRept.No.UCB/GT-2000/08).Berkeley,CA:Dept.of CivilandEnvironmentalEngineering,UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley;2000.

[27]KayenR,MossR,ThompsonE,SeedR,CetinK,KiureghianA,etal.Shear-wave velocity–basedprobabilisticanddeterministicassessmentofseismicsoilliquefactionpotential.JGeotechGeoenvironEng2013:407–19. https://doi.org/10.1061/ (ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000743

[28]NCEER.In:YoudTL,IdrissIM,editors.ProceedingsoftheNCEERworkshopon evaluationofliquefactionresistanceofsoils(TechnicalReportNo.NCEER-970022).NationalCenterforEarthquakeEngineeringResearch,SUNY,Buffalo;1997.

[29] YoudTL,IdrissIM,AndrusRD,ArangoI,CastroG,ChristianJT,etal.Liquefaction resistanceofsoils.Summaryreportfromthe1996NCEERand1998NCEER/NSF workshopsonevaluationofliquefactionresistanceofsoils.JGeotechGeoenviron Eng2001;127(10):817–33

[30] LiaoSSC,WhitmanRV.OverburdencorrectionfactorOSforSPTinsand.JGeotech Eng1986;112(3):373–7

[31] BoulangerRW.Highoverburdenstresseffectsinliquefactionanalyses.JGeotech GeoenvironEngASCE2003;129(12):1071–82

[32] SancioRB,BrayJD.AnassessmentoftheeffectofrodlengthonSPTenergycalculationsbasedonmeasuredfielddata.GeotechTestJASTM2005;28(1):1–9. [PaperGTJ11959]

[33] CetinKO,DerKiureghianA,SeedRB.Probabilisticmodelsfortheinitiationof seismicsoilliquefaction.JStructSaf2002;24(1):67–82.

[34]CetinKO,Bilge,HT.Stressscalingfactorsforseismicsoilliquefactionengineering problems:aperformance-basedapproach.In:Proceedingsoftheinternational

conferenceonearthquakegeotechnicalengineeringfromcasehistorytopracticein honorofProf.KenjiIshihara,Istanbul,Turkey;2013.

[35]MontgomeryJ,BoulangerRW,HarderJr.LF.ExaminationoftheKσoverburden correctionfactoronliquefactionresistance.JGeotechGeoenvironEng2014. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT

[36] VaidYP,ChernJC,TumiH.Confiningpressure,grainangularityandliquefaction.J GeotechEngASCE1985;111(10):1229–35

[37]HynesME,OlsenRS.Influenceofconfiningstressonliquefaction.Physicsand MechanicsofSoilLiquefaction.Balkema,Rotterdam;1999.p.145–51.

[38]IdrissIM.Seedmemoriallecture.UniversityofCaliforniaatBerkeley;1995.

[39]IdrissIM.AnupdatetotheSeed-Idrisssimplifiedprocedureforevaluatingliquefactionpotential.(PublicationNo.FHWA-RD-99-165).In:ProceedingsoftheTRB workshoponnewapproachestoliquefaction,FederalHighwayAdministration; 1999.

[40] SeedHB,IdrissIM.Groundmotionandsoilliquefactionduringearthquakes. Oakland,Calif.:EarthquakeEngineeringResearchInstituteMonograph;1982

[41] CetinKO,BilgeHT.Performance-basedassessmentofmagnitude(duration)scaling factors.JGeotechGeoenvironEngASCE2012;138(3):324–34

[42]AndrusRD,StokoeKHII.Liquefactionresistancebasedonshearwavevelocity.In: ProceedingsoftheNCEERworkshoponevaluationofliquefactionresistanceof soils.StateUniv.ofNewYork,Buffalo;1997.p.89–128.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

will: he is the sheer miraculous birth of gayety from the frustrate desert of Cervantes’ life.

To Sancho, the “phenomenal” world, the world of facts is everything. Since he conceives no other, and since his master continuously lives within another of his own conceiving, Sancho is held busy translating into factual terms the entire adventure which he rides with Don Quixote.

A vertiginous effort it is, and it ends by making Sancho more nearly mad than his knight. He believes factually in his Island. He believes himself its governor, though he has crossed no water to attain it. The maid who is to wed Don Quixote after he has gone to Africa to slay her foe is factually to him the Princess Micomacoma. This enchantment must be a fact, like the one which befell Dulcinea, turning her into the wench Aldonza. Sancho vacillates forever between the credulity and the skepticism of the literal mind: ignorance is so clearly the matrix of his sanity that the delusions of his master become wise by contrast. There are no dimensions to his thinking. Don Quixote is mad—or he is a true knight-errant: the adventure is wild,—or there will be a veritable island.

His dominant impulse, either way, is greed. Greed makes him doubt: greed makes him trust his master. Yet underneath, there works subtly upon Sancho a sweeter influence: his indefeasible respect for Don Quixote. Howsoever he argue, howsoever clear he see, howsoever he sicken from constant thumpings and sparse earnings, howsoever wry are the pleasures of his Island, Sancho cannot altogether free himself from the dominion of an idealizing will which he can never understand. In a directer way (since he is no intellectual) than that of Sansón Carrasco, he is held and haunted by Don Quixote. When he is absent from his master he is lost. When, in a scene more touching than the pathos of two quarreling lovers, Don Quixote gives him leave to depart homeward, promising him reward for his past service, Sancho bursts into tears and vows that he cannot forsake him.

He loves his master. Not greed alone, or if so, the greed of devotion to an ungrasped grandeur, holds him astride his dappled ass to follow Don Quixote to the sea. And yet, he despises him; and he betrays him. He judges him, and he exploits him. He makes sure of his reward in Don Quixote’s will, and he gives up the comfort of his wife to follow him through ridiculous dangers. He is this sensual, lusty, greedy oaf of the soil. And yet

in the love that masters him he is Cervantes, himself: Cervantes who created Don Quixote to laugh and to mock—and who remained to worship.

For this is the crux of the matter. Cervantes needed Sancho to keep Don Quixote in the perspective for laughter. “Common-sense” rides along with the “madman,” and constantly shows him up. But here is Sancho, shown up himself! Here is Cervantes, shown up! For Cervantes accepts Don Quixote. And that is why we accept him. Cervantes builds up these countless reasons for rejecting him: the havoc wrought by his acts, the shoddy stuff of his dream, the addled way of his brain. It avails naught. Cervantes ends with love. And we—the more humbly in that we have mocked and roared— avow our veneration.

Of such stuff is made the holiness of Don Quixote: mildewed notions, slapstick downfalls. We laugh at his unfitness to impose his dream upon a stubborn world: we see well enough that Rocinante is a nag and the knight himself, helmeted with a dish, a mangy addled fellow. And we accept, in order that he may live this nonsense, the disruption of inns, the discomfiture of pilgrims, the routing of funerals, the breaking of bones!

Cervantes strives hard to snuff out the aspiring hunger of his soul. For this, Don Quixote is bemuddied and deformed. But Don Quixote lives: and his chief enemy—Cervantes—gives him his blood and his passion, in order that he may triumph.

c. The Book of the Hero

Don Quixote is written in a prose majestical, dense, warm, lucid, still. It is the fulfillment of the Castilian music which Rojas’ La Celestina promised a century before. The tempo is slow. More correctly, the organic movement of the prose is slow; and the facet movements are swift and nervous. The Cervantine prose is a portrait of the soul of Spain whose cadences of desire and will resolve into an immobile whole.

The accentual music of this prose had already become the innate quality of Castilian. Cervantes heightened his inheritance. The natural genius of the language was already, in the mystics and novelists before him, one that made for a muscular, slow yet sharply surfaced prose. In Don Quixote, the music has as its base an almost cosmic beat, within which as in a firmament, the swifter, brighter, more fleeting qualities stand forth. Cervantes makes good use of the agglutinated verb and pronoun, of the

syncopations within the general prose rhythm. Above all, he makes use of the loamy expressions of the people, transfiguring them, however, into a tonal design not remotely naturalistic and more akin to the prose of the religious writers than of the pícaro novelists who also helped themselves to the vernacular of the soil.

In the great novel of Rojas there is a like marriage of pungent and ironical stuffs in an exalted orchestration. The difference is one of quality and quantity. Cervantes’ instruments are more varied; his themes and the materials that build them are more numerous, even if no one is richer than the central form of La Celestina. Indeed, the earlier work is the intenser; its colors are more hot. There is in Cervantes a strain of the north which the Jew Rojas lacked; and which made his æsthetic action longer and slower. The art of the Semite is more lyrical, less architectonic. La Celestina is a bomb-like organ; a piston-strong machine driving hard and singly. It is the tale, moreover, of a city where life is vertical and packed. Its form is true to its theme. But Don Quixote is the story of a journey—of three journeys rather—over the plains and mountains of La Mancha, Aragon, Catalonia. Its basal movement is panoramic, horizontal. Its loftier dimensions are attained by the associative power of its hero who, riding the roads of Spain, touches incessantly the spiritual realms of a people, of an age, of a soul. The formal values of La Celestina are more manifest. Very consciously, an intellectual, nervously coördinated man bound together the counterpoint of his design, so that each element partakes immediately of the whole. This is not the case in Don Quixote. The materials of the book—persons of the road, interpolated stories, situations—stand end to end, flat for the most part and quite episodic. The knight enters them organically. He transfigures them as a new element in a chemical solution. He enacts a continuous catalysis upon the parts of Spain which he encounters. The result of this is two-fold. There is created for the entire book a surface of action and a line of action. These hold the attention of the reader: these, indeed, caused the book’s popularity when it first appeared. The surface of action in the large is the Spain to which the Spanish people through the picaresque novel had been accustomed for over fifty years. The line of action is the pilgrimage of Quixote and Sancho.

But each of these two actions is complex. In consequence, their organic synthesis is often subtle and hidden. This synthesis gives to the work its unity: and one can enjoy Don Quixote without awareness of it. Indeed, the

synthesis may take place in the reader’s mind, long after he has absorbed its elements and put the book aside.

Consciousness of the organic greatness of La Celestina must come at once; since that greatness is the result of a design preconceived and implicit in the book’s several scenes. Consciousness of the greatness of Don Quixote came late even to its author and not to Spain until a whole century had passed. For its parts have an immediate life of their own; only after they have become lost and merged in one another does the book’s unity, as a synthesis of all these parts, dawn on the reader.

The knight himself is not so much an organ in this ultimate synthesis as a dimension. The synthesis is not articulate in him alone, any more than in the episodes. But it is articulate in the book’s language. And the rare individual who understood the æsthetic nature of prose might tell from the first page that Don Quixote was a stupendously formal work of art.

This prose is a becoming prose. It is heavy and pregnant. It is the antithesis of the immediate prose of Santa Teresa or of the lapidic absoluteness of the verse of Luis de Góngora. It is attuned at every moment to the whole of the book. It lacks swiftness and often sharpness. It is frequently clumsy in the projecting of little scenes. The book abounds in episodes that Quevedo would have fleshed more brightly or the author of Lazarillo pointed to more effect.

Cervantes is forever after deeper game. If, for instance, he describes the cozy dinner at which Quixote and Sancho shared the meat and acorns of six goatherds, the prose is not fundamentally focused upon the genre: but upon the tragic implications of Don Quixote’s presence and upon the irony of the attitude of the goatherds.

But Cervantes never states these deeper implications. His prose creates them. And creates them, by the immanent and abstract nature of its music. This immanence runs throughout the work, and thereby Cervantes is permanently saved the unæsthetic makeshift of statement. His direct attention goes unhindered to the presentment of the action. The action’s significance, one might say its soul, is implicit as is the significance of life implicit and unasserted in material substance and in specific action.

But as in all great art, this deep effect is won at sacrifice of a lesser. Analogously, El Greco maintains the larger anatomy of his vision

throughout the details of his paintings, although he loses thereby the grace and accuracy of the anatomy of his subjects.

There are still cavilers at El Greco’s drawing; and there have always been depreciators of Cervantes’ prose. Lope de Vega whose prosody was an immediate lyric flow of two dimensions, was perhaps sincere in his denigration of Cervantes. And even today Miguel de Unamuno, for all his adoration of Don Quixote, decries the language of Cervantes, for a similar reason: Unamuno’s lyric mood can not span the parabolas in which the figure of Don Quixote is limned.

These parabolas are the lines of the prose: and they are not, like simpler curves, to be plotted in the segment of any specific action in the book. But they are to be felt in every page. That is why the first chapter of Don Quixote announces the inscrutable tragi-comedy, although Cervantes when he wrote it had no knowledge of his undertaking. The music of his prose is the mother of his book. It is the beginning of the book’s significance, and it is the conclusion. Nor can it be translated.

A work of art in whose making significant forces have not played is inconceivable. The veriest trash, the most incompetent effort must in some wise have issued from a man’s life, from a people’s will, from an epoch’s spirit. What lies between such work and work significant in itself is not difference of material, but form. The poor work is one in which the elements of life are inchoate and, failing to achieve a unity of form, cannot be said to achieve life itself. The real work of art is that in which these elements achieve a body: is that of which these elements are the body. But the bodies of men and age whence its elements of life have sprung will rot away. Other men and other ages will succeed; and these in their will to know essential union with all men and all ages preserve the true work of art. For in it only, do those moldered lives of other men and ages touch them. The real work of art, builded of the substances of time, therefore alone does not exist in time. And a consideration of the work of art, whose basis is not equally beyond time—is not metaphysical or religious—is inadequate to art’s function in the world of time.

Before all else, Don Quixote is in form the life of Cervantes.

Toward the end of his last adventure, on the way to Barcelona, Don Quixote with Sancho attempts to hold the road against a herd of bulls. But

they are overturned, trampled, bemudded. They find a limpid spring garlanded with trees and wash the blood and mire from their sore bodies. Sancho brings food from the saddlebags. But his master is too disconsolate to eat. Sancho waits patiently: seeing no end to Don Quixote’s sorrow nor to his own hunger, he falls to.

“Eat, friend Sancho,” says Don Quixote. “Sustain the life which means more to you than to me, and leave me to die in the embrace of my thoughts and in the power of my disgraces. I, Sancho, was born to live dying; you, to die eating. And that you may see how I speak truth in this, behold me printed in history, celebrated in arms, commended in all my acts, respected in principles, desired by damsels; from end to end, whilst I awaited the palms, triumphs and crowns merited by my valorous deeds, you have seen me as this morning laid low, outraged and ground down, under the hoofs of obscene and filthy brutes....”

The roars and blows that greet the Sorrowful Knight might, in the jargon of our day, be termed Cervantes’ masochistic satisfaction. Cervantes ridicules himself for the dreaming fool he has been. But the strain is too deep. This figure that he sets going to make mock of is after all his soul. He grows away from his embittered pose. He can still laugh at his creature; still gather him at the end back into the logic of his story. But in Part Two, he is seen defending him against the laughter of others. He is seen regarding his knight, for all his folly, as purer than the sensible world: and at the last, more real.

But the times were out of joint. Spain and Don Quixote were pitted against Reasons: the logic of their ideal against the reasons of a world breaking from the unity of God which once had been the Roman Church, into a multiverse of fragmentary facts which is our modern crisis.

Frustrate brilliance, seeking to be healed, is the one unity of the modern story. Since Columbus voyaged, we have voyaged and bruised ourselves in spiritual chaos: seeking the salvation of wholeness and seeking it in vain.

From our search has come the national concept of the State, for instance: a degenerate medievalism, this—a wistful effort to achieve the wholeness of Rome without the holiness that informed it. Has come the Marxian Internation—an inverted idealism which put up the economic process in place of the Hegelian Spirit. Has come the faith in science as Revelation. Has come with Rousseau, the seeking of salvation through the return to the

unity of man’s primordial needs: with Nietzsche, the same seeking in the but seeming opposite direction of the superman. And finally, Darwin inspired us to hope that God might be inserted as the principle of flux in biologic process. All these prophecies and dogmatic actions strove alike to enlist mankind once more in a full unity of life and impulse. All who believed in them, to the extent of their devotion, have been Quixotes.

Don Quixote gave himself to make the world One, through the application of measures that strike us as shoddy and unreal. His were the old “magics” of chivalry—of a Europe peopled by Germanic children and schooled by adolescents from Athens, Alexandria and Rome. The magics no longer worked: had indeed not worked to build a universal House, since Dante. But we, laughing betimes at Quixote, patronizing Dante, have for five hundred years been struggling to construct our house with materials equally inadequate. The primacy of reason or of subjective intuition, the autonomy of science or of economic purpose, the ideal of the State or social interstate, the dream of communism or the return to nature—one and all are magics as impotent and as unreal as those of the old knight who rode La Mancha on a bony nag, with a barber’s dish on his brow, and in his head a neo-platonic vision.

Don Quixote and Faust are the great antistrophes to the Commedia of Dante. The body of Dante’s poem had the same elements as the body of Dante’s world. They were the Judæo-Christian revelation, Aristotelian logic, Euclidean Nature, the Ptolemaic cosmos. They cracked, and with them Catholic Europe passed. Only in Dante and in certain other art forms, like the Gothic churches, has that body lived.

Don Quixote and Faust are bodies of Europe’s dissolution—forms of our modern formlessness and of our need to be whole. They are perhaps the most vital æsthetic organs of the activity into which modern man was thrown by the deliquescence of his medieval world. As a poem, the Spanish work is the greater. Faust is the child of personal lyrism and speculative will. His sources, like the Knight’s, are medieval. He seeks knowledge and through knowledge personal redemption. He knows that he cannot be redeemed, save by a cosmic understanding; and his sense of understanding is in this, the mystic’s: that it implies possession of what is understood, and a dynamic act. But Faust remains the atom, the unfertile seed of human

will. His way to unify the world is to dominate and absorb it within the complex of personal volition. This is heroic, but it is savage. It ignores the fundamental wisdom of the Jews and Hindus which taught that the health of the personal will lies through the threshold of its death. Faust seeks knowledge through its extended acquisition. Mefisto is the symbol of his faith in the reality of extension. If he can garner the right catchwords, he can swallow the world; and the world will become one within him. This bluntly is the means toward a new synthesis adapted by all the centuries of Europe that intervene between the Renaissance and us: and it is Kabbalistic! The personal will, in its endeavor to achieve fusion with the world, has concocted formulæ that were to act directly on the world, and by magic to control it. These formulæ of course became external organisms: they became a machine, an empire or empiric law. Instead of lending themselves to a solution, they spawned a multitude of problems. They could not fecundate the personal will, from which they issued. For it is the Law that from personal will, alone when it is rendered fertile by its own disaster (like a rotted seed) can cosmic will and a cosmic synthesis arise.

The legend of Christ was deeper: deeper the blundering way of Quixote. For he sought the grace of union not by absorbing the world into himself, but by transmuting himself into an impersonal symbol of the world.

He failed; but his book lives; for with the failure is the triumphant impulse that led up to it. The effect of the crusade was death; the cause was life.

The magics of Don Quixote are as absurd as our own. But his impulse was as true as the Prophets’. The Old and the New Testaments also are a tale of sins and follies. But these are visible, because the light of God shines on them. In the effect that passes, all the prophets and all the Christs have failed. None of them has failed, in the cause that remains. The cause of Don Quixote’s life strikes us as truer than the realities which brought about his death. This is the pitiful best that we can say for him—or for any of the prophets.

One and all, they encountered reasons which put their truth to flight. And the world was able to live whole within their truth only in ages which willfully made reason servile. In the violence of his divorce from the world which he aspired to unite, in the ridiculousness of his discord from it, Don Quixote stands the last prophet of our historic Order. He bespeaks our need:

a dynamic understanding which shall enlist ideal and reason, thought and act, knowledge and experience; which shall preserve the personal within the mystical will; which shall unite the world of fact in which we suffer all together, with the world of dream in which we are alone....

CHAPTER X

THE WILL OF GOD

a The Bull Fight

b Man and Woman

c Madrid

a. The Bull Fight

T�� bull fight is older than Spain; the art of the bull fight has little more than a hundred years of history. Perhaps Crete, which gave El Greco to Toledo, gave the bull worship to Tartessos. Perhaps the Romans turned the bull rite into spectacle. The Visigoths assuredly had bull fights: and the medieval lords of Spain jousted with bulls as Amadis with dragons. The toreo was held in the public squares of towns, alternating possibly with autos de fe. In the one sport, the actors were nobles and the victims were bulls. In the other, officiated captains of the Church and the victims were Jews. In both, the religious norm was more or less lost sight of, as the spectacular appeal grew greater. But no æsthetic norm had been evolved to take its place. The bull fight was a daredevil game to which the young bloods of the Court—in their lack of Moors to fight—became addicted after the Reconquest. It was a dangerous sport, and it cost the kings of Spain many good horses and not a few good soldiers. Still, it throve until in 1700 a puritan, Philip V, ascended to the throne. He disliked the bull fight. It lost caste among the nobles. But its usage was too deeply, too immemorially engrained. The gentleman toreador went out: the professional torero and banderillero came in.

Francisco Goya has recorded in genial sketches and engravings the nature of this bull fight. It was still chiefly a game of prowess. If an art, it was more allied to the art of the clown and acrobat than to the dance or the drama. The professional torero was a gymnast. He had to risk his skin in elaborate ways: and skill was primarily confined to his grace in going off unhurt. He fought the bull, hobbled on a table, or lashed to a chair, or riding a forerunner in a coach, or saddled to another bull.

Only after the War of Independence against the French and after the lapse caused by Napoleon, whose generals disapproved of so barbarous an art, did Spain’s popular tragedy arise: the modern, profound corrida. Its birthday was the same as that of the jota of Aragon which sprang directly from the incitement against the French. Like the jota, the bull fight was new only as an integration of old elements. And like the ancient bull-rite of Tartessos it reached its climax in Andalusia: more particularly in the Province of Seville.

The plaza de toros is of course the Roman circus. Rome created no more powerful form for an æsthetic action than this rounded, human mass concentered on sand and blood. With its arena, the bull fight wins a vantage over such western spectacles as cricket, baseball, the theater. In all of these, the audience is a partial unit: it is not above the action, but beside it. The arena of the bull fight is a pith of passion, wholly fleshed by the passionate human wills around it.

The plaza is too sure of its essential virtue to expend energy in architectural display. Here it scores another point over the modern theater whose plush and murals and tapestries and candelabras so often overbear the paleness of the play. The plaza has tiers of backless seats terracing up to balcony and boxes. The seats are of stone: the upper reaches are a series of plain arcades. The plaza is grim and silent. It is stripped for action. It is prepared to receive intensity. The human mass that fills it takes from the sand of the arena, glowing in the sun, a color of rapt anticipation. These thousands of men and women, since the moment when they have bought their tickets, have lived in a sweet excitement. Hours before the bugle, they are on their way. They examine the great brutes whose deaths they are to witness. They march up and down the sand which will soon rise with blood.

Bright shawls are flung on the palcos. Women’s voices paint the murmur of the men. A bugle sounds, and there is silence. The crimson and gold mantones stand like fixed fires in this firmament of attention. The multitudinous eyes are rods holding in diapason the sky and the arena. Two horsemen (alguaciles) prance forward through the gates. Black velvet capes fold above their doublets. From their black hats wave red and yellow plumes.

They salute the royal or presidential box; circle the ring in opposite directions and return to the gate. The music flares. They proceed once more on their proud stallions, and behind them file the actors in the drama. The toreros are first: four of them: they wear gold-laid jackets, gold-fronted breeches backed in blue, rose-colored stockings. The banderilleros in silver drape their pied capas across their arms. The picadores follow. They are heavy brutish men, with chamois leggings and trousers drawn like gloves over their wooden armor. They are astride pitiful nags, each of which is Rocinante. The shoes are encased in stirrups of steel; the spurs are savage against the pitiful flanks. Behind the picadores are the red-bloused grooms, costumed like villains. It is their task to clean up entrails and gore. And the procession closes with two trios of mules, festooned and belled, who draw the drag to which the bodies of slaughtered bulls and horses will be attached.

The cavalcade crosses and salutes. Toreros, banderilleros, picadores on nervous nags, scatter along the barriers. Again, the bugle sounds. Doors open on the interior passage which two high barriers hold as a protective cordon between the audience and the arena. A bull leaps into the glare.