Introduction

Landuseregulationsarecommonurbanpoliciesinmostcitiesalloverthe world.Commonregulationsinclude(1)zoningbywhichlanduseisrestricted zonebyzone;(2)lotsize(LS)regulation,whichrestrictsthesizeofeachhousinglot;(3)urbangrowthboundary(UGB)control,whichseparatesurban developmentareasfromurbanizationcontrolareas;and(4)floorarearatio (FAR)regulation,a whichrestrictsbuildingsizes.Theadoptionandimplementationoftheseregulationsvaryaccordingtothecountryorthecity.In somecases,multipleregulationsmaybeappliedtoasinglebuilding;likewise, eachregulationcouldbeimplementedinslightlydifferentways.b

Whydocitiesimposelanduseregulations?Inpractice,citiesimposeland useregulationsforvariousreasonssuchastomitigatetrafficcongestionand noise,improveurbanaesthetics,controlairpollution,recoverpublicservice cost,orreducefrictionsbetweenagents(e.g.,landownersandresidents)and conflictsinlanduse.c Similartootherpublicpolicies,thetargetsofpractical landuseregulationsarenotnecessarilyeconomicallyreasonable.Nevertheless,sufficientaccountabilityisrequiredforregulationsbecausetheregulationsrestrictresidentsandlandownersfromfreelyusingtheirpropertyas theywish,andinmostcases,regulationsresultincostsforthem.Hence,land useregulationsshouldbejustifiable.

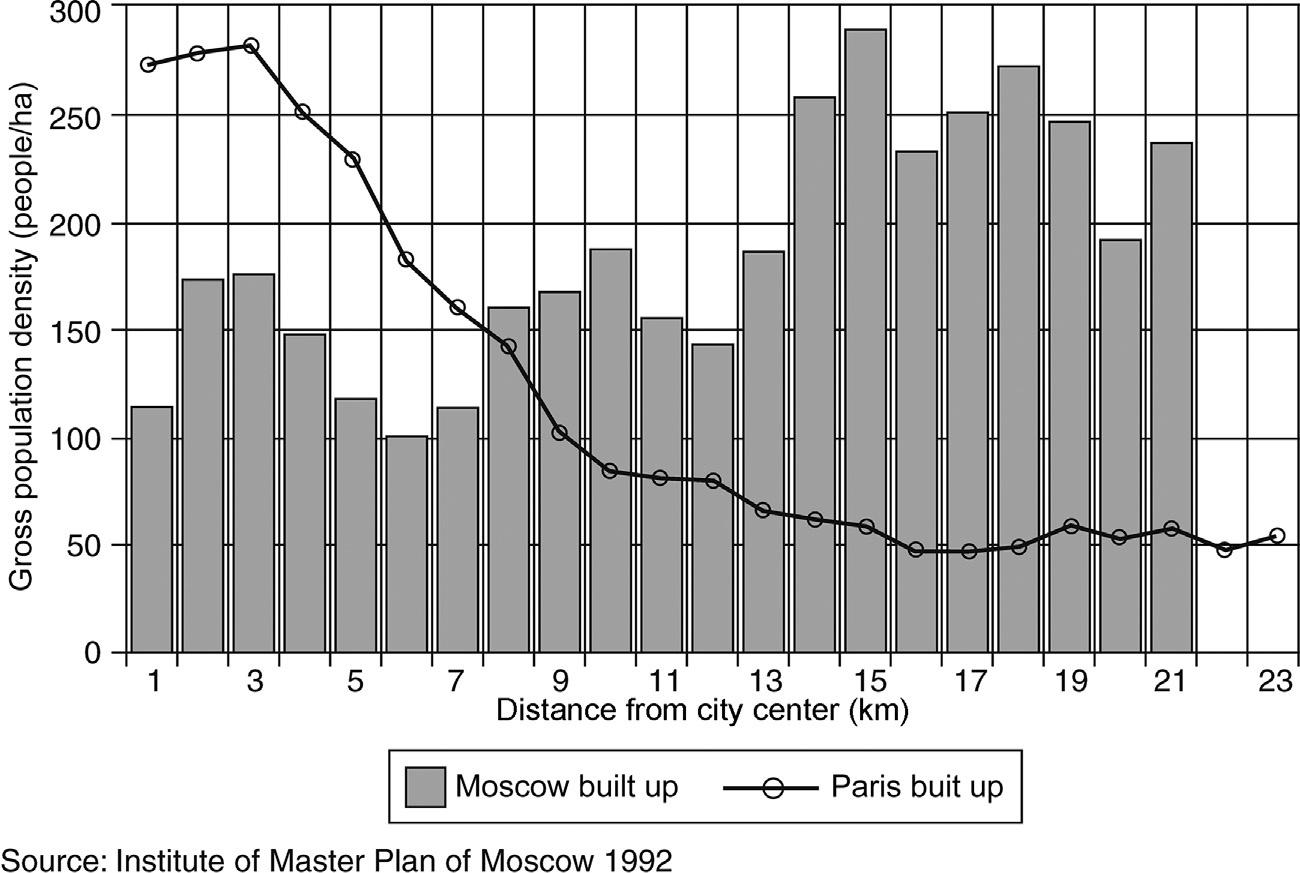

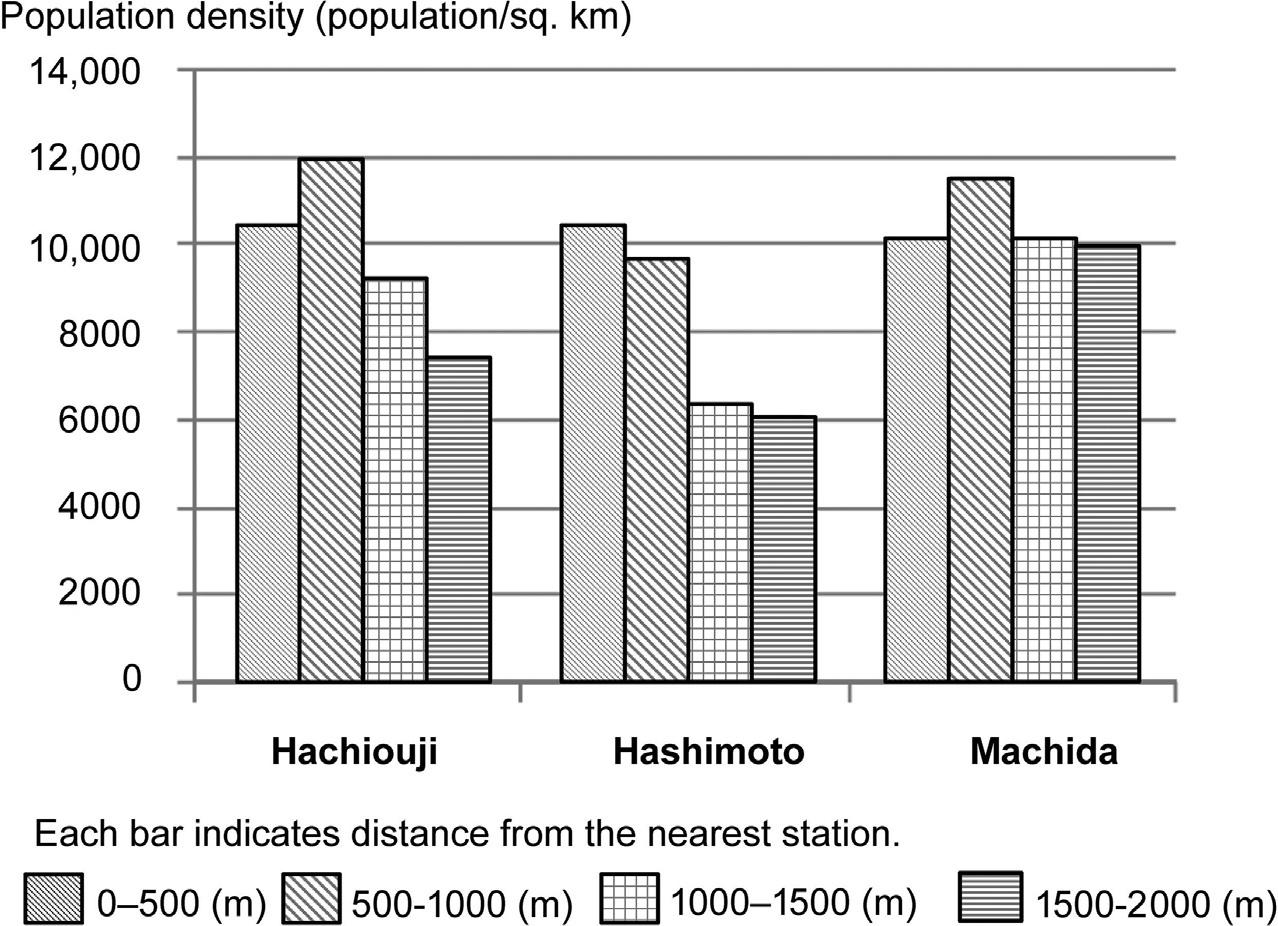

Moreover,buildingsareprobablyoneofthemostdurablegoodsever produced.Accordingly,ifaregulationatacertaintimeleadstoinefficient urbanlanduse,itremainsinefficientformanyyears.Aninefficientresultof landuseregulationcanbeseeninMoscow.Asshownin Fig.1.1 borrowed from BertaudandRenaud(1997),theMoscowbureaucraticdensitycontrol ledtoaperverse,invertedpopulationdensitypatterninwhichsuburban areashavemoreresidentsthanthecentralareas,incontrasttoPariswhere thereverseistrue.ThedensitypatterninMoscowgeneratesheavytraffic burdens.AnotherexampleisseeninsuburbsinTokyo. Fig.1.2 shows

a FARistheratioofthetotalfloorareaofabuildingtothesizeoftheplotonwhichthebuildingisbuilt.

b Forexample,anurbangrowthboundarycanbeimplementedbyusingagreenbelt.Inmanycountries, forregulatingabuilding,aLSrestrictionissetalongwitharestrictionontheFARofthebuilding.

c Somelanduseregulationsmightbeusedforlessbenignpurposessuchastoservelandowners’benefits (see BruecknerandLai,1996). TrafficCongestionandLandUseRegulations

Fig.1.1 ComparisonofdensitygradientsofMoscowandParis. (Source:Bertaud,A., Renaud,B.,1997.Socialistcitieswithoutlandmarkets.J.UrbanEcon.41(1),137–151.)

Fig.1.2 ComparisonofdensitygradientsamongtownsinTokyo. (Source:Sagamihara City,2011.OutlookofSagamiharaandMachidaUsingMaps,p.52.)

changeinthepopulationdensityinthreesuburbtownsaccordingtothedistancefromtheneareststationin2005(SagamiharaCity,2011).Thesethree townsarenewtowns,informallycalled“bedtowns,”whichwerebuiltas residentialplacesforemployeesworkinginthecenterofTokyo.Comparing thedensitypatternsamongthethreetowns,whilethepopulationdensity decreaseswithdistanceinHachioujiandHashimoto,thedensityisalmost constantinMachida.TheconstantdensityofMachidageneratesgreater congestionofcommutingtripsthanintheothertwotowns.Thisdifference inpopulationdensitypatternsisprobablycausedbypastlanduseplanning.

Asthesedifferentdensitypatternsshow,itisimportanttosetappropriate landuseregulationsorpoliciestoachieveefficientpopulationdensitypatterns.However,asthisbookwillshow,theurbanmechanismbehindland useregulationsisnotstraightforward.Accordingly,carefulconsiderationin cityplanningisrequiredatanytime.

Ineconomics,policiescanbeevaluatedandaccountedforfromtwo viewpoints:efficiencyandincomedistribution.Inthisbook,weexplore landuseregulationsfromthesetwoperspectives.However,wefocusmore onefficientlanduseregulationsbecausetheeffectoflanduseregulationson incomedistributionissoindirectandcomplexthatpolicymakersdonot adoptlanduseregulationsfromtheviewpointofincomedistributionin mostcases.Nevertheless,becauselanduseregulationsdonotnormally involveincomeredistribution,itisimportanttoknowtheeffectsofland useregulationontheincomedistributionbetweenagents.Thisbook exploresthedifferenteffectsonlandownersandresidents.

Urbanactivitiesinthemarketmechanismsloseefficiencyinvarious manners.Landuseregulationscandealwithseveraltypesofmarketfailures suchasagglomerationeconomiesinbusinessareas,congestionexternality, pollution(e.g.,noiseandairpollution),blockedsunlightoraircirculation betweenbuildings,aestheticdegradationoflandscape,andnonoptimal investmentcostsofpublicfacilitiessuchasroadsandwaterandsewagesystems.Thesemarketfailuresincurhugesocialcosts.

Oneimportantmarketfailureistrafficcongestionexternalities.Traffic congestionintheUnitedStatesin2007causedanadditional4.2billion hoursoftravelandanextra2.8billiongallonsoffuelconsumption,costing alossof $87.2billionintraveltimeandfuelalone(SchrankandLomax, 2009).InJapan,about8billionhoursperyeararelostduetotrafficcongestion,andthisamountcorrespondstoabout40%ofthetraveltime(Ministry ofLand,Infrastructure,TransportationandTourism,2015).Trafficcongestionexternalityspatiallyextendsfromthecenterofacitytoitsboundary,

anditsmagnitudedependsonthelocation.So,landuseanddensitiesatlocationsinacitywithtrafficcongestionareobviouslyinefficient.

Anotherimportantmarketfailureisagglomerationeconomies,which arisefromhighemploymentdensitybecauseofeasyaccesstointermediate goodsandlabor,facilitatingjobmatching,andknowledgespillovers,among others(FujitaandThisse,2013; RosenthalandStrange,2004; Puga,2010). Theemploymentelasticityofcityproductivity,whichisatypicalmeasureof agglomerationeconomies,isestimatedtobe0.05intheEUregion (Ciccone,2002)andJapan(Nakamura,1985)and0.06intheUnitedStates (CicconeandHall,1996).d Inotherwords,doublingtheemploymentdensitywouldincreasethecityoutputby5%intheEUregionandJapanand6% intheUnitedStates.

Agglomerationeconomiesgeneratespatialconcentrationofworkers, althoughtheconcentrationlevelisinsufficient.Thegeographicalconcentrationofworkerssimultaneouslyproducescommutingtripsfromresidentialareastothebusinessareas.Asagglomerationeconomiesincrease,the numberofconcentratedworkersincreases,andsimultaneouslythetotal lengthoftripsinacityincreases.Wehavetodealwithsuchspatialland usepatternstoincreasethewelfareofcityresidents.

TheseexternalitiescanbecompletelyinternalizedbyspatiallydifferentiatedPigouviantax(orsubsidies),whicharedifferencesbetweenthesocial marginalcost(benefit)andtheprivatemarginalcost(benefit).However,for politicalreasonsinparticular,itishardtoimplementsuchspace-dependent Pigouviantaxesandsubsidies.

Indeed,Pigouviantaxes,orevendilutedversionsofPigouviantaxes, haveneverbeenthecommonmeasurestoaddressurbanspatialexternalities suchascongestionandagglomerationeconomies.Forexample,although mostcitiesintheworldsufferfromseveretrafficcongestion,whenafew advancedcities(e.g.,London,Milan,Oslo,Singapore,andStockholm) introducedcongestionpricing,ithadbeenmorethan50yearssinceJohn

d Elasticityofproductivitycanalsobemeasuredintermsofindustrysize(employment)andcitysize(population).Forexample,theemploymentelasticityofproductivityinJapanesecitiesisestimatedat0.05by Nakamura(1985),thatinBraziliancitiesat0.11by Henderson(1986),andthatintheUSmetropolitan statisticalareasat0.19by Henderson(1986).ThepopulationelasticityofproductivityinJapanesecities isestimatedat0.03by Nakamura(1985) and0.04by Tabuchi(1986) andthatinGreekregionsat0.05 by Louri(1988).Recently,suchquantitativeanalyseshavebeenconductedatmicrolevels(individual firmsandplants)owingtotheincreaseindataavailability.Thisbodyofresearchincludes Henderson (2003), RosenthalandStrange(2003), Moretti(2004),and Jofre-Monsenyetal.(2014) Henderson (2003),usingpaneldata,estimatesplantlevelproductionfunctionsthatallowforscaleexternalitiesfrom otherlocalplantsinthesameindustryandfromthediversityoflocaleconomicactivitiesoutsidethe industry.

KainandWilliamVickreyproposedpracticalversionsofcongestionpricing inthe1950sfollowing Pigou’s(1920) initialproposal(see Harsmanand Quigley,2011).Furthermore,currentpracticalapplicationsofcongestion pricingareintheformofcordonorareapricingandarefarfromthe first-bestcongestionpricing.Foragglomerationeconomies,laborsubsidies havebeenproposedbymanystudies(e.g., Kanemoto,1990; Fujitaand Thisse,2013; LucasandRossi–Hansberg,2002).Nevertheless,laborsubsidieshaveneverbeenintroducedinanycitiesandprobablyneverbeen discussedeither.

Incontrasttosuchfirst-bestpolicies,landuseregulationshavebeen imposedforalongtimeinmanycitiesaroundtheworld.e Thiscommon useoflanduseregulationsispartlybecausegovernmentstendtoprefer quantityregulationstopriceregulations.Forexample,intheUnitedStates, 92%ofthejurisdictionsinthe50largestmetropolitanareashavezoning ordinancesofonekindoranotherinplace,andonly5%ofthemetropolitan populationlivesinjurisdictionswithoutzoning(Pendalletal.,2006).In Japan,mostcitieshavetheirownlocalcityplanningcouncilstomakecity plans.However,itisnotaneasytaskforthegovernmentstorationallydesign optimallanduseregulationsbecauseoftheneedtoconsiderchangeinprice distortionscausedbytheregulationsandchangeinspatialexternalities.f Indeedthemechanismsinvolvingaspatialequilibriumarecomplex.

Againstthisbackground,itisveryimportanttofindoptimallanduseregulations,byclarifyinghowthedistortionsandexternalitieschangeaccording tolanduseregulationsandbyclarifyingthemechanisms,whichdependon theurbansituation(e.g.,whetherornotpopulationchangesinresponseto landuseregulation)ortheexternalitycharacteristics.g Forthispurpose,we needatheoreticalmodelinwhichtheoutcomesofalltheagents’behaviors areinequilibriumandtheequilibriumdependsonlanduseregulations.

Inthischapter,wereviewtheoreticalstudiesonlanduseregulations. Thepurposeofthisreviewistocapturetheoverallflowofdevelopment ofmodelsforanalyzinglanduseregulationsandnottoshowacomprehensivereviewofthestudies.Toaddressthespatialmechanismsoflanduse

e Theprevalenceoflanduseregulationsallovertheworldcouldbeattributedtothesocialpreferencefor policiesthatinvolvenodirectmoneypayment,makingiteasyforpolicymakerstoimplementsuch policies.

f Sometimes,somemembersinthelocalcityplanningcouncilsinJapanarguethattheyfollowmarket equilibriumtosetregulations.However,suchcommentisillogicalbecauseifthemarketequilibriumis followed,thereisnoneedtosettheregulations.

g Notethatlanduseregulationscanbereplacedbyequivalentpropertytaxpolicies(see PinesandKono, 2012).

regulations,webasicallyreviewonlygeneralequilibriummodelsandignore empiricalresearchonlanduseregulations.h Inaddition,wedonotreview growthcontrolpapersthatconsideronlythepopulationdistributionacross citiesandignoreheterogeneousspaceswithtransportationandamenities withinacity.Basically,wefocusontheingredients,whichplayanimportant roleindetermininglanduseregulationsinacity.

Thefollowingdiscussionclassifiesthetheoreticalstudiesintofivecategories.Thefirstfourcategoriesofthestudiesexploreefficiencyoflanduse regulationsratherthanincomedistribution.Thefirstcategoryincludesstudiesuptotheyear2000.ManystudiesinthisperioduseAlonso-typemodels andregardthecentralbusinessdistrict(CBD)asapointinthecenterofthe city(apointCBD).Thesecondcategoryofstudies,publishedafter2000, alsofeaturesAlonso-typemodelsbutwithsomemodification(e.g.,acity withhigh-riseresidentialbuildingsbutapointCBD).Thethirdcategory extendstheAlonsomodelfromapointCBDbyaddingnonzerobusiness areasorconsideringduocentriccity.Thefourthcategoryleapsfromthe Alonsomodeltodemonstratedynamicsandasystemofcitiesandispublishedafter2000.Thelastcategoryexploresmainlyincomedistributionof landuseregulations,ratherthanefficiency.Thestudiesineachcategory aresummarizedinthetablesonthefollowingpages.

Theoreticalstudiesontheefficiencyoflanduseregulationsfirstappearin the1970s,followingthe Muth(1961) model,the MillsandDeFerranti (1971) model,andthe Solow(1973) model,whichincorporateroadcongestionintothe Alonso(1964) model. Table1.1 summarizessuchstudies onlanduseregulationsfromthe1970supto2000.

Studiesinthisperiod,exceptfor ArnottandMacKinnon(1978) that numericallycalculatethewelfarecostofbuildingsizeregulation,take accountofcitiescomposedofonlydetachedhousesandroads.Moststudies useanAlonso-typemodel,thatis,astaticmonocentriccity.Forexample, Kanemoto(1977), Arnott(1979), PinesandSadka(1985),and Wheaton (1998) useAlonso-typemodelstoexploredeviationofshadowpricesfrom marketpricesofhousingatdifferentlocationsunderunpricedcongestion.

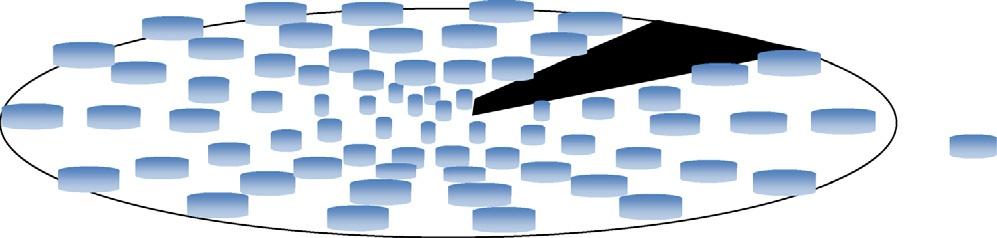

Agraphicalrepresentationofthistypeofcitiesisshownin Fig.1.3,where eachcylinderonthecitycircleindicatesahouse,andthebaseofthecylinder representsthelotsize.Asaresultofrentcompetitionamongresidents,the

h Landuseinterventionsandtheireffectsonthewelfarelevelofurbanresidentshavebeendiscussedin manypreviousstudies(see Brueckner,2009,forasurveyoftheoreticalanalyses,or Evans,1999; Brueckner,2009,forasurveyofempiricalinvestigations).Inaddition,hugeempiricalresearchisbeing produced(e.g., Brueckneretal.,2017; Albouyetal.,2017).

Table1.1 Studiesonefficiencyoflanduseregulations(1970–2000).

Study Landuse regulation Targeted externalitiesModelcharacteristics

Stull(1974) ZoningNeighborhood externalities Nonzerobusinessarea, detachedhousing

Helpmanand Pines(1977) ZoningNeighborhood externalities Nonzerobusinessarea, detachedhousing, multiplecities

Kanemoto(1977) UGBcontrolRoadcongestionRoadspace,detached housing

Arnottand MacKinnon (1978) FAR regulation Nospecified externalities Condominiums

Arnott(1979) UGBcontrolRoadcongestionRoadspace,detached housing

PinesandSadka (1985) LSregulation andUGB control RoadcongestionDetachedhousing

Sullivan(1983) ZoningAgglomeration economies,road congestion Nonzerobusinessarea

Brueckner(1990) UGBcontrolPopulation congestion Dynamicmodelling,an opencity

Engleetal.(1992) UGBcontrolRoadcongestion andpollution Detachedhousing,twocitymodel

Sakashita(1995) UGBcontrolRoadcongestionTwo-citymodel Sasaki(1998) UGBcontrolCongestion,public goods,production Differentlandownership systems

Wheaton(1998) LSregulationRoadcongestionDetachedhousing Dingetal.(1999) UGBcontrolCongestiblepublic good Dynamicmodelling,an opencity

Abbreviations: UGB,urbangrowthboundary; FAR,floorarearatio; LS,lotsize.

Fig.1.3 Alonso-typemodelincorporatingcongestedroads.

lotsizeislargerinthesuburbsthaninthecentralarea.ThisAlonso-type modelhasonlydetachedhousesandnohigh-risebuildingssothatthe inverseofthelotsizeexpressespopulationdensity.AnotherimportantfeatureisapointCBD.

Amongotherstudiesusingsimilarmodels, Stull(1974) and Helpmanand Pines(1977) explorezoning,takingaccountofnonzerobusinessareasin additiontotheresidentialareas. Sullivan(1983) considersexternaleconomiesofscaleinproductioninnonzerobusinessareasundertrafficcongestion,usingnumericalsimulations. HelpmanandPines(1977), Engleetal. (1992),and Sakashita(1995) extendtheAlonso-typemodelstoincludemultiplecities.Incontrasttothepreviouslymentionedstaticmodelsinthis period, Brueckner(1990) and Dingetal.(1999) derivetheefficientdynamic pathoftheUGB.

Asanoptimalregulation, Kanemoto(1977) showsthattheUGBshould besmallerthanthemarketequilibriumurbanboundary. PinesandSadka (1985)i and Wheaton(1998) showthattheexcessburdenofunpricedtraffic congestioncanbecompletelyeliminatedbyappropriateLSregulations. Accordingly,underoptimalLSregulation,theUGBcanbedetermined bythemarketintheirmodel.Thisishardlysurprisingbecauseimplementing LSregulationsisequivalenttodeterminingthepopulation’sdistributionina citymodelcomposedofonlydetachedhouses.Comparing Kanemoto (1977) and PinesandSadka(1985),wefindthatsimultaneousconsideration ofmultiplelanduseregulations(LSregulationandUGB)givesadifferent optimalsolution(uselessUGBinPinesandSadka)whenaddressingasingle regulation(usefulUGBinKanemoto).Accordingly,multiplelanduseregulationsshouldbeexploredsimultaneously.Inthisperiod,mostpapers explorezoning,LSregulations,orUGBcontrol,ignoringfloorareasizeregulationsbecausetheytreatonlydetachedhouses.

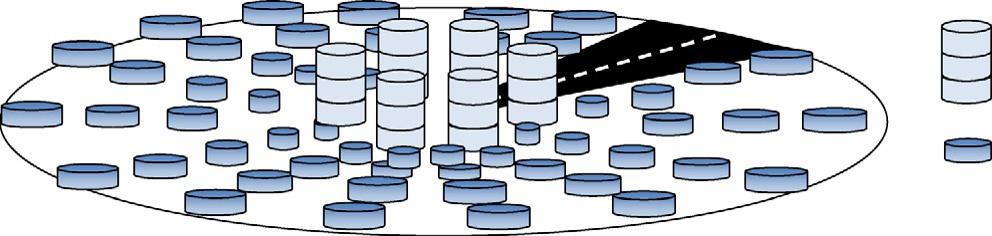

Since2000,variationsofthemodelexploringlanduseregulationshave expanded.Wehaveclassifiedthisvarietyintothreetypes.Eachtypeissummarizedin Tables1.2–1.4.Asshownin Table1.2,mostpaperstakeaccount ofhigh-risebuildingsincludingcondominiumsinacitywithpointCBD andexploreFARregulations.Thispointisdifferentfromthestudiesbefore 2000.Agraphicalrepresentationofthistypeofcitiesisshownin Fig.1.4, wherehigh-risebuildingsareaddedto Fig.1.2.UnliketheAlonso-type

i PinesandSadka(1985) usehousingtaxtocontrollotsize.However,thisisequivalenttoLSregulationin termsofsocialwelfare.Landuseregulationscanbereplacedbyequivalentpropertytaxpolicies(see PinesandKono,2012).

Table1.2 CitywithapointCBD(2000onward).

StudyLanduseregulation Targeted externalities Model characteristics

Bertaudand Brueckner (2005)

Brueckner (2007)

PinesandKono (2012)

Konoetal. (2012)

MaximumFARregulationNoexternalitiesNumerical simulation

MaximumFARregulation, UGBcontrol RoadcongestionNumerical simulation

Maximumandminimum FARregulations,UGB control Roadcongestion

Maximumandminimum FARregulations,UGB control Roadcongestion

KonoandJoshi (2012) FARregulation,UGB control RoadcongestionClosedand opencities

Borck(2016)

MaximumFARregulationGHGemissions Tikoudisetal. (2018) FARregulation,UGB control Roadcongestion

Konoand Kawaguchi (2017) FARregulation,UGB control Roadcongestion

Abbreviations: UGB,urbangrowthboundary; FAR,floorarearatio; LS,lotsize; GHG,greenhousegas.

Table1.3 ExtensionsoftheAlonsomodelfromapointCBD(2000onward).

Study Landuse regulationTargetedexternalitiesModelcharacteristics

Rossi-Hansberg (2004)

AnasandRhee (2006)

ZoningAgglomeration economies,no roadcongestion Nonzerobusinessarea

UGBRoadcongestionMixedlanduse,nonzero businessarea Rheeetal. (2014)

Buyukerenand Hiramatsu (2016)

Zhangand Kockelman (2016)

KonoandJoshi (2018)

ZoningAgglomeration economies,road congestion Mixedlanduse,nonzero businessarea

UGBRoadcongestionAnuncongestedpublic transitmodeandacar mode

Zoning, UGB Agglomeration economies,road congestion Nonzerobusinessarea

Zoning, FAR, UGB Agglomeration economies,road congestion Nonzerobusinessarea

Abbreviations: UGB,urbangrowthboundary; FAR,floorarearatio; LS,lotsize.

Table1.4 LeapsfromtheAlonsomodel(2000onward).

Study Landuse regulationTargetedexternalitiesModelcharacteristics

Linetal.(2004) FAR regulation Neighborhood externalities,road congestion Dynamicmodelling

AnasandRhee (2007) UGB control RoadcongestionExistenceofasuburban businessdistrict

Anasand Pines(2008) UGB control RoadcongestionTwo-citymodel

Joshiand Kono(2009) FAR regulation PopulationcongestionTwo-zonecitywith growingpopulation Konoetal. (2010) FAR regulation PopulationcongestionTwo-zonecity

Jou(2012) UGB control PopulationcongestionStochasticrents

AnasandPines (2012) UGB control RoadcongestionMultiple-citymodel

Abbreviations: UGB,urbangrowthboundary; FAR,floorarearatio.

models,theinverseofthelotsizedoesnotrepresentpopulationdensityanymorebecausehigh-risebuildingsincludemanyhouseholds.Still,thistypeof modelassumesapointCBD.

Asthesepost-2000studieshaveclarified,weshouldtreatFARregulation andLSregulationseparatelytoexploreoptimalregulationsbecauseFAR regulationnecessarilygeneratesdeadweightlosscausedbytheregulation itself(see Chapter2 fordetails),whereasLSregulationhasnodeadweight losses(see PinesandSadka,1985; Wheaton,1998).UnderFARregulation, householdscanchoosetheiroptimalfloorsizewithintheregulatedbuildings.Inotherwords,FARregulationcontrolspopulationdensityindirectly, whereasLSregulationdoesthisdirectly.

Detached houses

High-rise building

CBD Road

Fig.1.4 Alonso-typemodelwithhigh-risebuildingsandroads.

Consideringhigh-risebuildings, BertaudandBrueckner(2005), Brueckner(2007),and BruecknerandSridhar(2012) quantitativelycalculateinageneralequilibriumframeworkhowmuchthewelfarecostofmaximumbuildingsize(orFAR)regulationincreaseswithanincreaseinthe commutingcosts. Konoetal.(2012) and PinesandKono(2012),usinga closedcitymodel,showthat minimum FARregulationshouldbesimultaneouslyimposedalongwithmaximumFARregulationtoachieveoptimal regulation.Next, KonoandJoshi(2012) showhowoptimallanduseregulationsdifferbetweenclosedandopencities. Tikoudisetal.(2018) and KonoandKawaguchi(2017) considerroadtollsandFARregulationssimultaneously.Indeed,real-worldcitiesimplementingcongestionpricing imposelanduseregulationssimultaneously.

Landuseregulationscanalsocontributetowardmakingcitiesenvironmentfriendlybychangingpopulationdistribution.Inarelatedstudy, Borck (2016) estimateshowgreenhousegasemissionsasCO2-equivalentchange withFARregulation.

Thestudieslistedin Table1.2 havetakenaccountofonlyroadcongestionorenvironmentaldamageintheresidentialareas,assumingapoint CBD.Incontrasttosuchnegativeexternalities,concentrationofworkers inbusinessareasincitiesenhancescommunicationandthusfacilitates exchangeofinnovativeideas(see Rauch,1993; CicconeandHall,1996; DurantonandPuga,2001; Moretti,2004).Suchpositiveagglomeration economiesinbusinessareascanbeexploredbytakingaccountofnonzero businessareaasshownbypost-2000paperslistedin Table1.3

Inthe1970s, Stull(1974) and HelpmanandPines(1977) already considerednonzerobusinessareastoexploreoptimalzoningtotackleexternalitiesbetweenmanufacturingandresidentiallanduse.However,agglomerationeconomiesarisingfromemploymentdensityarenotconsidered. Rossi-Hansberg(2004) takesaccountoftheexistenceofagglomeration spilloversoffirmstoexplorezoning. Rheeetal.(2014), Zhangand Kockelman(2016),and KonoandJoshi(2018) considertheexistenceof agglomerationeconomiesandtrafficcongestiontoexplorelanduseregulations. Rheeetal.(2014) focusonmixedlandusewithresidencesand businesses.Onelandusepatternofthesemodelsisshownin Fig.1.5.An essentialfeatureofthistypeofcitiesisnouseofapointCBD.So,howland isallocatedfordifferentlandusepurposesmatters.

Allpreviousstudiessofarhaveshownthatinamonocentriccity,residentiallocationsshouldbecentralizedbyoptimallanduseregulationswhen thereisonlycarcommuting.Incontrast, BuyukerenandHiramatsu(2016),

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

R.

Rain-maker, the Bahurutsi, 442; murdered among the Bauangketsi nation, 447.

Rains, the, begin as early as September and October, 125.

Rath, Mr., 61, 109, 121; his description of the track of a nondescript animal, 133.

Rehoboth, a Rhenish missionary station, 139, 281; description of, 286; the rocks in its neighborhood strongly impregnated with copper, 349.

Religion, 198.

Reptiles, numerous in Damara-land and Namaqua-land, 293; superstitions respecting, 294; antidotes used in Southern Africa for the bites of, 295.

Rhinoceros, the, curious anecdote preserved in the archives of Cape-Town relating to a death of one, 26; Mr. Bam’s story of his wonderful escape from one, 49, 50; tracks of, 49; one shot, 72; fall frequently on their knees when killed, 73; curious anecdote, ib.; flesh not unpalatable, ib.; hide useful, ib.; discovery of a, 84; adventure in pursuit of one, 85; its escape, 86, 87; combat between elephant and, 164; several shot at Ghanzé, 369; where found, 370; four distinct species known to exist in South Africa, 371; distinctions between the black and the white rhinoceros, 373; appearance of, 374;

food, 375; breeding, 376; Colonel Williams’s story respecting one, 377, 378; conflicts with elephants, 378; the flesh and horns, 380; adventure with a black rhinoceros at Kobis, 399; with a white one, 400; the Author shoots a white one, 407; desperate adventure with a black one, 407, 408; method of chasing, 381; Mr. Oswell’s stories respecting the chase of, 382.

Richterfeldt, a Rhenish missionary station, reached, 61; water abundant, ib.; soil fertile, ib.; when founded, 62; return to, 95; bid a final farewell to, 123.

Rifle, obtained in barter, 150; excellent weapon, ib.

Rights of succession, 198, 222, 225.

Ringel-hals, the, or ring-throat, a species of snake, 294.

Roode Natie, the (or Red Nation), a powerful tribe of Namaquas, 279; their character, 280; Cornelius, their chief, ib.; their country, 281; few Damara slaves among them, ib.

S.

Salt-lick, a, 366.

Sand Fountain, excursion to, 34; badness of its water, 35;

its disagreeable guests, 36; its advantages, 37; general aspect of the country in the neighborhood of, 38.

Sand-wells, 365.

Scarlet flower, the, emotions on first seeing, 48; observe it again, 49.

Scenery, striking, 170.

Schaap-steker, the, a species of snake, 294.

Scheppmansdorf, Mr. Galton arrives at, 40; all the baggage safely deposited at, 41; description of, ib.; first impressions of, 76; kind friends at, 77; departure from, 83.

Scheppman’s Mountain, origin of its name, 103.

Schmelen, Mr., a highly-gifted and enterprising missionary, 127.

Schmelen’s Hope, its situation, 126; origin of its name, 127; agreeable residence; abundance of game to be obtained there, 135; departure from, 146; return to, 214.

Schöneberg, Mr., 101; his mishap, 102; his wailing, 103.

Scorpions, a swarm of, 105; their fondness of warmth, ib.; their bite poisonous, but rarely fatal, ib.

Season, the rainy, in Ovambo-land, 201; in Damara-land, 217.

Sebetoane, an African chief, false report respecting, 414.

Serpent, tracks of an immense (the Ondara), 290; story of a, 291.

Serpent-stones, 297.

Servants, described, 78-83; African travelers can not be too particular in the selection of, 79; become refractory, 125; adventure of one of them with an ox, 270; Damara servants abscond, 355.

Shambok, the, 73, 74.

Shrike, a species of, 78; superstitious belief respecting, ib.

Smith, Dr. Andrew, 213, 491.

Snake, a curious species of, 292; several species occasionally met with in Damara-land and Namaqua-land, 294; antidotes for the bites of, 295; numerous in and about Lake Ngami, 435, 436.

Snake-stone, the, 298.

Snuff, manner in which the Bechuanas manufacture, 458.

Spring, hot, at Barmen, 108; at Eikhams, 230; at Rehoboth, 286.

“Spring,” Author’s ride-ox, 71.

Spuig-slang, the, or spitting-snake, 294.

St. Helena, John, officiates as head wagoner, 80; his extraordinary disposition, ib.; discourses on ghosts, 331.

Steinbok, the, a young one taken and reared, 130; its tragic end, 131.

Stewardson, Mr., 45.

Stink-hout, a species of oak, 170.

Sugar-cane, supposed to exist in many parts of Southern Africa, 188.

Sun-stroke, Author receives one, 58; usual results of a, ib.; the Author in danger of a second, 88.

Sunrise, the, in the tropics, 51; often followed by intense heat, and sufferings thereon, ib.; a mule left behind, ib.

Superstition, a, with regard to oxen, 152.

Swakop, the, first appearance of, 49; its cheerful aspect, ib.; the Author’s party attacked by two lions on the bank of, 93; the Damaras flock with their cattle to, 241.

T.

Table Mountain, 25; ascent by the Author of, ib.

Tans Mountain, 348.

Tent, the Author’s, takes fire, 299.

Teoge, the River, feeds Lake Ngami, 427; scenery along the banks of, 460; crocodiles observed on, 471.

Termites, the, Schmelen’s Hope swarms with, 136; their method of constructing their nests, ib.; encampment in the middle of a nest of, 145; instances of the fearful ravages they are capable of committing in an incredibly-short space of time, 155.

Textorerythrorhynchus, a parasitical insect-feeding bird, 213.

Thirst, suffering from, 52; water not quenching thirst, ib.

Thorn coppices, 182.

Thunder-storm, a, in the tropics, 107, 141, 352.

Tiger-wolf (or spotted hyæna), 369.

Timbo, a native of Mazapa, 81; carried into captivity by Caffres, ib.; sold as a slave to the Portuguese, 82; liberated by an English cruiser, ib.; his faithless spouse, ib.; his good qualities, ib.; his love of (native) country, 83; friendship between him and George Bonfield, 336; turns sulky, 352; the Author sends him to Lake Ngami, 393; his return, 402.

Tincas, the mountain, 52; great stronghold and breeding-place of lions, ib.

Tincas, the River, 84.

Tjobis, a river and tributary to the Swakop, 59.

Tjobis Fountain, arrive at, 60, 93; depart from, 61, 93.

Tjopopa, a great chief of the Damaras, 168; reach his werft, 169; his character, ib.; death of his mother, 176; his idleness and fondness for tobacco, ib.; sensuality, 177; leaves Okamabuti, 207.

Tobacco, great size of leaves of, 110; the Ovambo cultivate it, 189;

buy sheep for, 208.

Topnaars, a branch of the Hottentot tribe, 314.

Toucans, 59.

Trans-vaal River, the, rumors respecting the churlish conduct of the Boers on, 27.

Traveling by day injurious, 58, 61; by, night preferable, but dangerous, 84; difficulties of African, 160.

Trees, bearing an apple-looking fruit, 176, 189; enormous sized, ib.

Tsetse fly, the, where chiefly found, 468; description of, 469; poisonous nature of its bite, ib.; result of Captain Vardon’s experiment on, 470; Mr. Oswell’s examination of oxen bitten by, 471; wild animals unaffected by the poison of, ib.

Tunobis, 233; days profitably and pleasantly passed there, 235; immense quantity of game in the neighborhood of, ib.; the Author’s misadventure at, 360.

Twass, the head-quarters of the Namaqua chief Lambert, 355.

U.

Usab, the, a striking gorge, we arrive at, 83.

V.

“Venus,” a small half-breed dog, her combat with a rhinoceros, 391; great sagacity of, ib.

Voet-gangers (videlarvæ).

Vollmer, Mr., 139, 286.

W.

Waggoner, John, his sulkiness and reluctance to work, 79; dismissed at Barmen, 125; his subsequent dishonest career, 139.

Wagons, the, fifteen hundred weight a good load for, 78; accident to, 170.

Wait-a-bit thorn, the, 156; great strength of its prickles, ib.; excessively troublesome, 367, 413, 415.

Walfisch Bay, the Author’s party advised to select this place as a starting-point for their journey into the interior, 28; arrival at the entrance of, 29; appearance of the coast as seen from, ib.; description of, 30; trading establishments there, ib.; frequented by immense numbers of water-fowl, 31: outrageous conduct of the crews of whaling and guano ships visiting, 243; extraordinary number of dead fish in, 245; the Author’s second visit to, 339.

Water, difficulty of obtaining, 306, 387.

Water-courses, the periodical, afford the only really practicable roads, 124.

Wenzel, Abraham, 79; his thievish habits, ib.; dismissed at Schmelen’s Hope, 140.

Whirlwinds, 217.

Williams, John, results of his carelessness, 80.

Willow-tree, the, in the neighborhood of Omuvereoom, 155.

Witch-doctor, the Namaqua, 318.

Witchcraft, Damaras have great faith in, 219; the Bechuanas have great faith in, 442.

“Wolf,” 114.

Wolves, or hyænas, 131.

Women, Ovambo, 194; Damara, 221; Bayeye, 480.

Z.

Zebra, melancholy wail of the, 98; the Author shoots one, 102; its flesh not very palatable, ib.; a lion mistaken for one, 112; the Author shoots one, 142.

Zouga, a river which flows out of Lake Ngami, 403; runs in an easterly direction from Lake Ngami for a distance of about three hundred miles, 428; vegetation along its course varied and luxuriant, ib.

Zwartbooi, William, a Namaqua chieftain, 137; relations between Jonker Afrikaner, and, ib.; his territory, 138; assists us with servants, 140.

Zwart Nosop, many pitfalls for game constructed in the neighborhood of, 238.

Zwart-slang, the, or black snake, 294, 295.

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting the free distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work (or any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project Gutenberg™ License available with this file or online at www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg™ electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property (trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in your possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. “Project Gutenberg” is a registered trademark. It may only be used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg™ electronic works even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project Gutenberg™ electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the Foundation” or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the United States and you are located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg™ works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg™ name associated with the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg™ License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project Gutenberg™ work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any country other than the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg™ License must appear prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg™ work (any work on which the phrase “Project

Gutenberg” appears, or with which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase “Project Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg™ trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is posted with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked to the Project Gutenberg™ License for all works posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg™ License terms from this work, or any files

containing a part of this work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg™.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project Gutenberg™ License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary, compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg™ work in a format other than “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official version posted on the official Project Gutenberg™ website (www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg™ License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying, performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg™ works unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing access to or distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works provided that:

• You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from the use of Project Gutenberg™ works calculated using the method you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, but he has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty

payments must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in Section 4, “Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.”

• You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg™ License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg™ works.

• You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of receipt of the work.

• You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free distribution of Project Gutenberg™ works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the manager of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread works not protected by U.S. copyright

law in creating the Project Gutenberg™ collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain “Defects,” such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the “Right of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, and any other party distributing a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund.

If the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you ‘AS-IS’, WITH NO OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone providing copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg™ work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg™ work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of

Project Gutenberg™ is synonymous with the free distribution of electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg™’s goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg™ collection will remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure and permanent future for Project Gutenberg™ and future generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project