Table des matières

Couverture

Page de titre

Page de copyright

Les auteurs

Abréviations

I: Connaissances

I: Médecine légale

Chapitre 1: Item 7 – UE 1 – Droits individuels et collectifs du patient

I Respect des droits fondamentaux du patient, information et consentement

II L'accès à son dossier médical

III Désigner une personne de confiance (encadré 1.2)

IV Droits individuels en fin de vie et rédaction de directives anticipées

V Confidentialité, secret et respect de la vie privée : exercer un droit de contrôle sur ses données de santé (encadré 1 4)

VI Cas particulier : utilisation et informatisation des données d'un patient à des fins de recherche

I L'obligation d'informer

II La preuve de l'information

III Conséquences d'un défaut d'information

IV Le consentement du patient

I Fondement du secret médical et sanctions

II Contenu du secret médical

III Les professionnels tenus au secret professionnel

IV Le secret, le patient et les proches

V Le secret partagé

VI Cas particuliers d'exercice médical

VII Dérogations légales au secret médical

I Élaboration et tenue du dossier médical

II Conservation du dossier

III Dossier médical informatisé (encadré 1.19)

IV Contenu du dossier

V Les notes personnelles

VI Personnes ayant accès au dossier médical

VII Modalités de communication

VIII Respect des délais et refus de communication du dossier

IX Dossier médical partagé (DMP)

X Dossier médical de santé au travail (DMST)

Chapitre 2: Item 8 – UE 1 – Éthique médicale

I Sens de la démarche éthique, différente de la morale et de la déontologie

II Éthique de la responsabilité

III Bioéthique et éthique appliquée

IV La nécessité d'une éthique procédurale pour guider l'éthique appliquée

I L'accès à l'AMP

II Fécondation in vitro et devenir des embryons

III AMP avec don de gamètes

IV Conservation de gamètes à usage autologue (autoconservation)

V Don et accueil d'embryons

VI Gestation pour autrui (GPA)

VII La question du clonage

VIII Révision des lois de bioéthique

I Cas de l'IVG : interruption pratiquée avant la fin de la douzième semaine de grossesse

II Cas de l'IMG : interruption pour motif médical de la grossesse

III Discussion des enjeux éthiques : les femmes, les couples et les professionnels face à des choix complexes

I Principes et objectifs de l'éthique de la recherche

II Émergence de l'éthique de la recherche

III Textes normatifs

IV Lois françaises

I Cas particulier de l'identification d'une personne par ses empreintes génétiques

II Cas le plus fréquent de l'examen des caractéristiques génétiques d'une personne dans un cadre de soins ou d'une recherche médicale

III Discussion des enjeux éthiques de la génétique prédictive

Chapitre 3: Item 9 – UE 1 – Certificats médicaux / décès et législation / prélèvements d'organes et législation

I Caractères généraux des certificats

II Certificat de « coups et blessures »

III Violences conjugales

I Diagnostic de la mort

II Certificat de décès

III Levée de corps médico-légale

IV Opérations consécutives au décès

V Cas des enfants décédés avant toute déclaration à l'état civil ou mort-nés

I Contexte des prélèvements multi-organes

II Législation – Historique

III Prélèvements pouvant être réalisés (tableau 3 5)

IV Prélèvements sur personne vivante

V Prélèvements sur personne décédée

Chapitre 4: Item 10 – UE 1 – Violences sexuelles

I Introduction

II Définitions et bases juridiques

III Prise en charge médico-légale

IV Prise en charge médicale

V Rédaction d'un certificat médical

Chapitre 5: Items 5 et 12 – UE 1 – Responsabilités médicales et missions de l'ONIAM

I Responsabilité et sanctions

II Responsabilité et indemnisation

Chapitre 6: Item 55 – UE 3 – Maltraitance et enfants en danger / Protection maternelle et infantile

I Éléments de compréhension

II Repérage d'une situation de maltraitance

III Diagnostics différentiels

IV Argumentation de la démarche médicale et administrative

V Quelques entités cliniques et paracliniques

II: Médecine du travail

Chapitre 7: Item 28 – UE 2 – Connaître les principaux risques professionnels pour la maternité, liés au travail de la mère

I Effets sur la fertilité

II Effets sur le développement lors de l'exposition durant la grossesse

III Effets sur l'allaitement

IV Prévention

V Réglementation

VI Accidents du travail et maladies professionnelles

Chapitre 8: Item 176 – UE 6 – Risques sanitaires liés aux irradiations Radioprotection

I Généralités

II Expositions

III Effets sur la santé

IV Prévention des risques d'exposition

Chapitre 9: Item 178 – UE 6 – Environnement professionnel et santé au travail

I Impact du travail sur la santé : rapporter une pathologie aux contraintes professionnelles

II Impact d'une pathologie chronique sur les capacités de travail

Chapitre 10: Item 179 – UE 6 – Missions et fonctionnement des services de santé au travail

I Organisation des services de santé au travail (SST)

II Actions des services de santé au travail

III Médecin du travail

IV Possibilités d'actions préventives du médecin du travail

Chapitre 11: Item 180 – UE 6 – Accident du travail et maladie professionnelle

I Couverture du risque accident du travail et maladie professionnelle (AT/MP) en France

II Accident du travail (AT)

III Maladies professionnelles (MP)

IV Procédures de déclaration d'AT et de MP

V Réparations des AT et des MP

VI Dispositions spécifiques pour les maladies liées à l'amiante

VII Protection de l'emploi

VIII Litiges

IX Suivi post-professionnel

X Différents types d'incapacité (encadré 11 1)

Chapitre 12: Item 183 – UE 7 – Hypersensibilités et allergies cutanéomuqueuses chez l'enfant et l'adulte. Urticaire, dermatites atopique et de contact

I Aspects cliniques

II Données épidémiologiques – Principales étiologies

III Stratégie diagnostique

IV Prévention

V Réparation

Chapitre 13: Item 184 – UE 7 – Hypersensibilité et allergies respiratoires chez l'enfant et chez l'adulte. Asthme, rhinite

I Définitions

II Diagnostic d'un asthme en relation avec le travail

III Pronostic, évolution et devenir du sujet atteint d'un ART

IV Mesures de prévention

V Réparation

Chapitre 14: Item 288 –

I Généralités

II Cancers broncho-pulmonaires (CBP)

III Mésothéliomes

IV Tumeurs malignes de vessie et des voies urinaires (encadré 14 2)

V Leucémies aiguës

VI Tumeurs malignes cutanées (épithéliomas cutanés)

VII Cancers naso-sinusiens (encadré 14 3)

VIII Cancers du nasopharynx

IX Angiosarcomes hépatiques

X Principales circonstances d'exposition à ces agents cancérogènes

II: Entraînements

I: Médecine légale

Chapitre 15: Dossiers progressifs

Dossier progressif 1

Dossier progressif 2

Dossier progressif 3

Dossier progressif 4

Dossier progressif 5

Dossier progressif 6

Dossier progressif 7

Dossier progressif 1

Dossier progressif 2

Dossier progressif 3

Dossier progressif 4

Dossier progressif 5

Dossier progressif 6

Dossier progressif 7

Chapitre 16: Questions isolées QI 1

2

3

4

5

6

Item 7 – UE 1 – Droits individuels et collectifs du patient

L'apport de la loi du 4 mars 2002 : droits individuels et droits collectifs

I. Respect des droits fondamentaux du patient, information et consentement

II L'accès à son dossier médical

III Désigner une personne de confiance

IV Droits individuels en fin de vie et rédaction de directives anticipées

V. Confidentialité, secret et respect de la vie privée : exercer un droit de contrôle sur ses données de santé

VI Cas particulier : utilisation et informatisation des données d'un patient à des fins de recherche

Information et consentement du patient

I L'obligation d'informer

II. La preuve de l'information

III Conséquences d'un défaut d'information

IV Le consentement du patient

Partage des données de santé : le secret professionnel

I Fondement du secret médical et sanctions

II Contenu du secret médical

III Les professionnels tenus au secret professionnel

IV. Le secret, le patient et les proches

V Le secret partagé

VI Cas particuliers d'exercice médical

VII Dérogations légales au secret médical

Le dossier médical

I Élaboration et tenue du dossier médical

II. Conservation du dossier

III Dossier médical informatisé

IV Contenu du dossier

V Les notes personnelles

VI. Personnes ayant accès au dossier médical

VII Modalités de communication

VIII Respect des délais et refus de communication du dossier

IX Dossier médical partagé (DMP)

X. Dossier médical de santé au travail (DMST)

Objectifs pédagogiques

L'apport de la loi du 4 mars 2002 : droits individuels et droits collectifs

Comprendre l'apport de la loi du 4 mars 2002 dans la relation médecin/patient.

Connaître les droits individuels des patients (consentement, information, accès au dossier, directives anticipées, personne de confiance, protection des données de santé)

Connaître les droits collectifs (notion de démocratie sanitaire).

Information et consentement du patient

Comprendre les enjeux du droit à l'information du patient dans la relation médicale

Comprendre que le patient est un coacteur de ses soins et de sa santé

Comprendra la notion de consentement éclairé.

Connaître les conditions de recueil du consentement éclairé.

Connaître la problématique du refus de soin.

Partage des données de santé : le secret professionnel

Connaître la notion de secret professionnel (principe, contenu)

Connaître les professionnels avec qui peuvent être partagées les données de santé

Connaître les dérogations au secret professionnel et notamment les situations pouvant conduire à la réalisation d'un signalement judiciaire

Le dossier médical

Connaître les principes d'élaboration et d'exploitation du dossier du patient, support de la coordination des soins

Connaître les modalités d'accès au dossier médical.

L'apport de la loi du 4 mars 2002 : droits individuels et droits collectifs

Aujourd'hui, du fait d'une démocratisation et d'une généralisation progressives de l'accès au savoir médical, la demande de participation des patients à la démarche de soins est croissante, posant la question de la liberté de choix des malades et questionnant de plus en plus les domaines où celle-ci serait niée

La pratique médicale est devenue un domaine où la participation du patient aux choix qui le concernent est reconnue comme un droit (quand cela n'est pas rendu impossible par un état de grande vulnérabilité et de perte d'autonomie psychique liée à la maladie)

I Respect des droits fondamentaux du patient, information et consentement

Le respect du patient repose en premier lieu sur le devoir d'information. Il recoupe deux niveaux :

• le premier, d'ordre éthique, où la place de l'autonomie du patient dans la relation de soin est de plus en plus reconnue et promue, fondement démocratique du respect et de la protection des personnes ;

• le second, d'ordre juridique, qui se traduit par l'obligation de délivrer une information de qualité permettant une acceptation ou un refus éclairé de la part du patient (encadré 1.1).

Encadré 1 1

L'information doit répondre à plusieurs objectifs :

• assurer la délivrance d'une information dans le respect des principes de transparence et d'intégrité, en se fondant sur les données actuelles de la science et de la médecine ;

• éclairer le patient sur les bénéfices et les risques en s'appuyant sur des données validées et, le cas échéant, en exposant les zones d'incertitudes ;

• éclairer, au-delà des bénéfices et des risques, sur : – le déroulement des soins, – les inconvénients physiques et psychiques dans la vie quotidienne,

– l'organisation du parcours de prise en charge au fil du temps et les contraintes organisationnelles entraînées,

– les droits sociaux de la personne malade et les aides et soutiens accessibles si besoin ;

• participer au choix entre deux démarches médicales ou plus dès lors qu'elles sont des alternatives validées et compatibles avec la situation d'un patient ;

• informer sur les aspects financiers (prise en charge par les organismes sociaux)

Après la délivrance d'une information de qualité, l'exigence du consentement d'un patient est fondée sur le principe de l'intangibilité de la personne humaine Tout individu a un droit fondamental à son intégrité corporelle Il convient donc d'avoir le consentement d'un patient, dès qu'il est conscient et à même de donner son accord, préalablement à toute intervention sur sa personne, c'est-à-dire avant mise en route de toute démarche diagnostique, thérapeutique ou de toute action de prévention

Les articles du Code civil précisent que « La loi assure la primauté de la personne, interdit toute atteinte à la dignité de celle-ci et garantit le respect de l'être humain dès le commencement de sa vie » (article 16 du Code civil) et que « Il ne peut être porté atteinte à l'intégrité du corps humain qu'en cas de nécessité médicale pour la personne ou à titre exceptionnel dans l'intérêt thérapeutique d'autrui Le consentement de l'intéressé doit être recueilli préalablement, hors le cas où son état rend nécessaire une intervention thérapeutique à laquelle il n'est pas à même de consentir » (article 16-3 du Code civil).

Le prélèvement d'un organe du vivant de la personne, par exemple un rein, est rendu possible par cet ajout de l'intérêt thérapeutique d'autrui

Pour que le consentement soit valide, il faut toujours avoir à l'esprit qu'il repose sur la qualité de l'information délivrée et comprise par le patient En effet, comment donner sens à un consentement recueilli alors que le patient aurait reçu une information de piètre qualité, le privant de la possibilité de faire un choix éclairé ?

Un cas rare doit cependant être mentionné : celui de la volonté de ne pas savoir Ceci peut constituer une exception au devoir d'information du patient s'il a clairement exprimé (données et arguments qui doivent être notés dans le dossier médical) la volonté d'être tenu dans l'ignorance d'un diagnostic ou d'un pronostic grave, voire de toute information concernant sa santé et sa prise en charge Toutefois, cette exception ne peut s'appliquer lorsque des tiers sont exposés à un risque de contamination Cette précision, inspirée du cas du VIH, vaut pour toutes les affections contagieuses graves et s'impose en raison de la responsabilité du patient vis-à-vis d'autrui et dans un intérêt de santé publique (par exemple dans le cas d'une tuberculose pulmonaire)

II L'accès à son dossier médical

Le dossier médical est défini comme un document sécurisé et pérenne regroupant, pour chaque patient, l'ensemble des informations le concernant Fiable et exhaustif, son contenu doit permettre de faire de ce dossier un outil d'analyse, de synthèse, de planification, d'organisation et de traçabilité des soins et de l'ensemble des prestations dispensées au patient. Son accès est régi par les règles du secret professionnel, c'est-à-dire que seules les personnes participant effectivement à la prise en charge du patient peuvent y avoir accès, sauf restriction particulière supplémentaire souhaitée par le malade.

La loi du 4 mars 2002 a prévu qu'au cours des soins ou postérieurement, le patient puisse avoir accès aux éléments de son dossier médical, directement ou par l'intermédiaire d'un médecin qu'il désigne Ce droit d'accès concerne les informations « qui sont formalisées ou ont fait l'objet d'échanges écrits entre professionnels de santé, notamment des résultats d'examen, comptes rendus de consultation, d'intervention, d'exploration ou d'hospitalisation, des protocoles et prescriptions thérapeutiques mis en œuvre, feuilles de surveillance, correspondances entre professionnels de santé, à l'exception des informations mentionnant qu'elles ont été recueillies auprès de tiers n'intervenant pas dans la prise en charge thérapeutique ou concernant un tel tiers » (article L 1111-7 du Code de la santé publique)

La loi du 13 août 2004 relative à l'assurance-maladie rappelle que l'accès au dossier médical permet de « favoriser la coordination, la qualité et la continuité des soins, gage d'un bon niveau de santé [ ] »

III Désigner une personne de confiance (encadré 1.2)

Outre l'optimisation du droit à l'information du patient, la loi de 2002 permet au patient majeur de se faire accompagner dans sa démarche de soins par ses proches, ce qui vise à l'amélioration de la relation soignants-soignés et du parcours de soins Le droit de désigner une personne de confiance est inscrit à l'article L.1111-6 du CSP.

Encadré 1 2

La désignation d'une personne de confiance doit donc sortir du cadre des pathologies sévères et des seules situations d'hospitalisation pour devenir une possibilité citoyenne, proposée à tous en population générale, indépendamment de l'état clinique

En pratique, patients et proches ne connaissent pas forcément cette procédure. Il est du devoir de tout soignant et de toute institution de soins de la proposer

La désignation devra in fine se faire par écrit, être signée par le patient et par la personne désignée et être notée dans le dossier médical, avec les coordonnées précises et la nature des liens entre patient et personne désignée, incluant les mises à jour

Depuis longtemps, les équipes soignantes sont soucieuses de voir comment un proche du patient, tiers relationnel et médiateur, peut aider à construire du lien dans les parcours de prise en charge et porter la parole du patient, en particulier lorsque ce dernier ne peut ou ne veut participer seul à la décision.

La personne de confiance, dans son acception première, a pour rôle premier, après désignation par le patient (désignation qui permet alors un partage du secret), d'assister ce dernier dans ses démarches de soins, de l'accompagner physiquement et/ou psychologiquement et de faire le lien avec les équipes médicales Elle est donc un accompagnant du soin au quotidien et des démarches de choix et de décision que fait le patient

Ce rôle premier mérite d'être rappelé car, parfois, la personne de confiance n'est encore perçue que comme un interlocuteur lors des situations de crises majeures, comme par exemple les arrêts ou limitations de soins en fin de vie, situation où la personne de confiance est amenée à témoigner des désirs du patient

Il faut d'abord exposer que tout proche peut être personne de confiance : frère, sœur, parent, grand-parent, oncle, tante, conjoint, concubin, ami, membre d'association, etc

Il faut expliquer au patient les buts de cette désignation, tout en expliquant aussi qu'elle n'a rien d'obligatoire. C'est une possibilité que le patient doit pourvoir choisir (accepter ou refuser s'il n'en ressent ni le besoin ni le désir), a fortiori s'il souhaite que le secret soit gardé totalement ou s'il veut protéger tous ses proches et taire sa maladie

Le rôle du soignant est de conseiller le patient en fonction du vécu de la maladie et de l'environnement familial ou affectif parfois complexe Il faut expliquer que la désignation, comme la non-désignation, sont des choix tout à fait légitimes C'est en ce sens que le Code de la santé publique dispose qu'il y a une obligation à proposer une personne de confiance mais non une obligation de désignation. Le fait de laisser cette liberté au patient et de le guider au mieux selon ses intérêts est ici une responsabilité d'ordre éthique Lors de la délivrance d'explications, la question de la rupture du secret vis-à-vis du proche désigné doit être discutée (jusqu'où le patient souhaite-t-il aller vis-à-vis des confidences, à quel moment, etc )

Concernant les personnes désignées, plusieurs points importants sont à évoquer, en particulier ceux de la disponibilité et de leur volonté de remplir cette mission, essentiels pour donner sens à la démarche

La loi ne prévoit pas de limite de validité de la désignation effectuée. Cependant, les aléas relationnels de la vie et l'évolution du vécu de la maladie par un patient impliquent que les choses peuvent évoluer et changer au fil du temps L'esprit de la loi et la variabilité légitime des choix d'une personne amènent à dire qu'il convient d'informer le patient sur le changement possible de personne désignée. La désignation est en effet révocable à tout moment par le patient. Pour les professionnels de santé, la recommandation est qu'il convient d'interroger le patient à chaque nouvelle hospitalisation ou à chaque nouveau cycle de prise en charge sur la pérennité de la personne désignée

IV Droits individuels en fin de vie et rédaction de directives anticipées

En lien direct avec la loi du 4 mars 2002, la loi du 22 avril 2005, relative aux droits des malades et à la fin de vie, est venue compléter dans ce domaine, les droits des patients

Elle instaure la possibilité du refus de soins, dès lors que ces derniers apparaissent « inutiles, disproportionnés, ou n'ayant d'autre effet que le seul maintien artificiel de la vie » Ce refus se concrétise par un arrêt ou une limitation des soins, curatifs ou palliatifs, avec pour conséquence, à plus ou moins court terme, le décès du patient Cette démarche autorisée par la loi a pu être qualifiée de « droit au laisser mourir ». La loi n°2016-87 du 2 février 2016, dite loi « fin de vie » est une évolution de celle de 2005 Elle renforce les droits en faveur des personnes malades en fin de vie et précise le rôle important que peuvent jouer les directives anticipées et la personne de confiance

En situation de fin de vie, d'un point de vue éthique, c'est le degré d'autonomie de pensée du patient qui est déterminant, véritable critère de qualification de sa capacité à développer une argumentation cohérente et réfléchie face à une telle décision

De manière pratique, deux cas de figure se dégagent :

• si le patient est conscient et capable de participer à une délibération, étayée par l'acquisition d'un savoir suffisant concernant sa maladie et son évolution, il est associé à cette décision Médecin et patient construisent alors un échange complexe et intime où le patient exprime son incapacité à lutter davantage et son souhait de ne pas prolonger sa vie Ainsi, un dialogue peut se nouer et permettre d'attester, au fil du temps, de la légitimité et de la réalité d'une demande de fin de vie. Le médecin peut donner alors suite à la demande formulée de LATA (limitation et arrêt des thérapeutiques actives), après discussions et réflexions approfondies avec le patient ;

• si le patient est dans l'incapacité de s'exprimer, il s'est construit un large consensus sur l'importance de rechercher son avis pour l'intégrer à la décision. C'est pourquoi la loi précise que lorsqu'une personne, en phase avancée ou terminale, d'une affection grave et incurable, quelle qu'en soit la cause, est hors d'état d'exprimer sa volonté, le médecin peut décider de limiter ou d'arrêter un traitement, inutile ou impuissant à améliorer l'état du malade, après avoir respecté la procédure collégiale et consulté les directives anticipées de la personne, la personne de confiance et les proches On fait intervenir ici, pour s'approcher du respect de la volonté du patient, la notion de témoignage de ce que la personne aurait souhaité

En France, l'évolution de la loi en 2016 avait pour objectif de renforcer et de préciser la place des directives anticipées, qui sont désormais valides dans le temps sans limite (tant que le patient ne les a pas modifiées) et opposables aux médecins Ce texte de 2016 précise par ailleurs une hiérarchie de valeur : les directives anticipées priment sur la personne de confiance, primant elle-même sur les autres proches Il réaffirme enfin le droit au soulagement de la souffrance et instaure un droit à la sédation profonde et continue jusqu'au décès (encadré 1.3).

Encadré 1 3

Principes instaurés par la loi

• Une obligation pour les professionnels de santé de mettre en œuvre tous les moyens à leur disposition pour que toute personne ait le droit d'avoir une fin de vie digne et accompagnée du meilleur apaisement possible de la souffrance

• La reconnaissance d'un droit pour le patient à l'arrêt ou à la limitation de traitement au titre du refus de l'obstination déraisonnable.

• Une obligation pour le médecin de respecter la volonté de la personne de refuser ou de ne pas recevoir un traitement après l'avoir informée des conséquences de ses choix et de leur gravité

• Un rôle renforcé d'information des médecins auprès de leurs patients sur la possibilité de rédaction de directives anticipées

• Le fait que les directives anticipées inscrites dans la loi sont désormais opposables, c'est-à-dire que les médecins référents d'un malade inconscient doivent suivre les perspectives écrites dans ce document si celles-ci sont appropriées à la situation médicale et hors urgence

• Le fait qu'il existe une hiérarchie concernant les moyens de tracer la volonté d'un patient ; d'abord les directives anticipées, puis à défaut le témoignage de la personne de confiance, puis à défaut tout autre témoignage de la famille ou des proches.

Tout citoyen, informé de cette possibilité, peut librement rédiger ses directives anticipées et les tenir à disposition des soignants en cas de besoin

Il convient donc aujourd'hui de promouvoir une information sur ce sujet de la fin de vie, sur l'accompagnement et sur le fait que les directives doivent être, si un patient ou un citoyen les a rédigées, transmises aux équipes qui le suivent

V Confidentialité, secret et respect de la vie privée : exercer un droit de contrôle sur ses données de santé (encadré 1.4)

La pratique médicale répond aux impératifs de secret et de confidentialité Toute personne a droit au respect de sa vie privée, les données de santé en faisant partie intégrante. Tout professionnel de santé et tout établissement de soins garantit la confidentialité des informations qu'il détient sur les personnes (informations médicales, données administratives, sociales et financières)

Encadré 1.4

Une déclaration doit être faite auprès de la CNIL lorsque le principe de la création de dossiers ou de fichiers informatisés est envisagé De plus, le patient doit être explicitement informé de l'informatisation de ses données et de son droit de s'y opposer Dans la pratique, il serait difficile aujourd'hui de prendre en charge un patient sans utiliser des données informatisées.

Ces informations sont couvertes par le secret professionnel Elles peuvent être partagées entre soignants uniquement dans la mesure où elles sont utiles à la continuité des soins visant à la meilleure prise en charge possible. En établissement de santé, ces données sont réputées avoir été confiées par la personne hospitalisée à l'ensemble de l'équipe de soins qui la prend en charge. La violation du secret à travers la divulgation de données concernant un patient engage des responsabilités pénales et civiles

En pratique, le stockage et la gestion des données médicales passent par des systèmes informatisés La protection des citoyens et le respect de la confidentialité lors de l'informatisation des données personnelles sont régis par la loi, en particulier celle de 1978, dite loi « informatique et liberté », à travers la Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés (CNIL)

Les procédures d'agrément des systèmes informatiques en santé impliquent :

• le respect de règles de sécurisation des données (codes d'accès et cryptage) ;

• l'interdiction d'usage à d'autres fins que médicales ;

• l'interdiction de partage avec tout tiers ne participant pas à la prise en charge d'un patient ;

• l'interdiction d'utilisation à des fins commerciales, politiques ou autres

Ces obligations s'imposent à tous les professionnels de santé mais aussi aux établissements de soins, aux réseaux de santé et hébergeurs de données

Toute personne peut obtenir communication, modification (droit de rectification) ou suppression des informations la concernant en s'adressant aux responsables de l'établissement ou du cabinet médical. Elle peut aussi demander des restrictions concernant les personnes habilitées à y avoir accès Tous ces choix du patient doivent être pris en compte

Qu'un dossier soit uniquement local ou en réseau, les données saisies et la tenue du dossier relèvent de la responsabilité médicale Chacun a sa part de responsabilité, au sens éthique comme au sens juridique et, en cas de litiges, seuls le ou les professionnels concernés par la partie du dossier incriminée peuvent être mis en cause, ce qui implique pour tous une grande vigilance, aussi bien dans leurs comptes rendus et leurs notes que dans la protection de l'accès aux dossiers, via leur système de codage et/ou leur carte informatique CPS (carte de professionnel de santé)

VI Cas particulier : utilisation et informatisation des données d'un patient à des fins de recherche

Cette possibilité est ouverte après information du patient, qui doit pouvoir exercer son droit d'opposition

Les recherches, études et évaluations n'impliquant pas la personne humaine portent en particulier sur la réutilisation de données déjà collectées au sein de bases existantes (cohortes, observatoires, registres, dossiers médicaux, etc ) et de bases médico-administratives L'ensemble de ces recherches, études et évaluations doit faire l'objet d'une demande d'autorisation auprès du Comité d'expertise pour les recherches, les études et les évaluations dans le domaine de la santé (CEREES) puis d'une autorisation de la Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés (CNIL)

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

world. By one of the canons issued by the fifth Council of Carthage, it was decreed that no church should be consecrated until some well-authenticated relics had been placed beneath the altar. In afterdays, it was further required that there should be relics visible at each entrance to the church, on the diptychs fastened to the chapel walls, in the sacraria, in a number of the private oratories, and even on the cover of the books of the mass.

This continual removal of relics from one country to another gave rise to many imposing and touching ceremonies. St. Chrysostom has related, in one of his homilies, all the details concerning the translation of the relics of St. Ignatius, who suffered martyrdom at Rome, to his episcopal residence at Antioch, amidst a vast assemblage of the faithful.

From the seventh century the removal of relics became more and more frequent, and the number of pilgrimages increased accordingly. Sometimes the relics were those of unknown saints. When Pope Boniface IV. (606) was about to dedicate to the Holy Virgin, and to all the martyrs or confessors, the Pantheon of Agrippa, by transforming it into a church, to be called Sancta Maria Rotunda, he caused to be conveyed thither thirty-two chariot loads of bones, taken from the Catacombs. Pope Pascal I. (817) also deposited a vast quantity of saints’ bones in the Church of St. Praxeas at Rome, previous to consecrating it. The names of these saints were not known, but the authenticity of their remains and of their claims to veneration were verified before the ceremony, by a committee appointed for that purpose.

Fig. 282. Henry I., Emperor of Germany, and one of his Generals, Gautier Von der Hoye. Equestrian statues in bronze, cast in 948 by order of the Emperor, and placed in the Church of Our Lady at Maurkirchen (Austria), in commemoration of his victory over the Huns. These statues, destroyed in a fire, were re-cast in plaster and placed on the same spot, where they were visible until June 27th, 1865, when the church was burnt to the ground.—After a Woodcut from a work called “ThurnierBuch,” in gothic folio: printed at Siemern in 1530.

In the course of three centuries, from the ninth to the eleventh, the discovery and the disinterment of saints’ bodies, their solemn

removal (Fig. 281), the foundation of monasteries, oratories, and churches in their honour, the institution of anniversary fêtes, and the setting apart of a number of private devotions at services, relating not only to relics, but to holy images, abound in all the annals of the Catholic world. This is supposed to be the epoch when were introduced into Europe those ancient images, in sculpture and in painting, of the Holy Mother of Christ, which were revered in the Middle Ages just as they are in the present day; among these were black virgins, which were, no doubt, of Abyssinian origin; tawny or yellowish virgins, from some country of Africa; and brown and Byzantine virgins, of a stern and hard-featured type, wanting in expression. These images, all of which were very coarsely executed —though the last-mentioned seem to be copied from a picture attributed to St. Luke (Fig. 283)—often peculiar in their expression and character, but most of them of unquestionable antiquity, were common in Italy, Spain, the Mediterranean Isles, and many of the southern provinces of France. They were much rarer in the west of Europe, in Belgium, Germany, and Ireland, where, however, they were looked upon with just as much veneration—as, for instance, the Notre-Dame de Luxembourg, which was tawny. In the North, in Hungary, Poland, and Russia, but especially in Russia (Figs. 284 and 285), there were only the dark and Byzantine images of the Virgin.

Fig. 283. The Virgin of St. Luke (so called). An image painted on wood, placed in the Church of Sta. Maria Maggiore, now San Paolofuor-gli-Muri, at Rome, in the Fourth or Fifth Century.

Fig. 284. Greek Panagia, or Image of the Holy Virgin, with a Portrait of Jesus Christ upon her bosom. From the “Antiquities of Russia,” by Sevastianof (Thirteenth Century).

The worship of relics, as well as that of miraculous images, had, beyond question, sometimes degenerated into superstition; but it is impossible to deny the services which it rendered to Christianity in these ages of barbarism. The people, without anything to restrain or to guide them, were in a state of perpetual commotion, easily tempted to evil, a prey to the first adventurer who could show them some ready road to plunder, impatient of all social restraint, moving about from place to place, and dead to all family ties and love of country. Amidst all this disorder, preaching unaccompanied by grand

religious spectacles would have been fruitless, and thus the Church revived the worship of relics. Search was made in every direction for the bodies of saints; the bishops themselves journeyed to Italy, to Africa, and to the East to collect the precious remains of those who had sealed their testimony with their blood. When these relics arrived at the place for which they were destined, the people went out to meet them and escort them back. Their transfer to the sanctuary, in which they were solemnly laid, was made the occasion for ornate ceremonies and for numerous pilgrimages (Figs. 286 and 287); and so devotion brought together hostile races which had long been separated by bitter warfare. The deeds done by the saint, who seemed as if present and visible to the eyes of the faithful, were read from the pulpit; the miracles which he had wrought might always be renewed under the influence of fervent prayer; a few cures were soon worked in proximity to his shrine, or upon his tomb. The pilgrims continually increased in number, and the priests gradually regained the moral authority which they had allowed to slip away from them.

Fig. 285. Miraculous Image of Our Lady of Vladimir, the goal of one of the most famous pilgrimages in Russia. From the “Antiquities of Russia,” by Sevastianof. (Twelfth Century.)

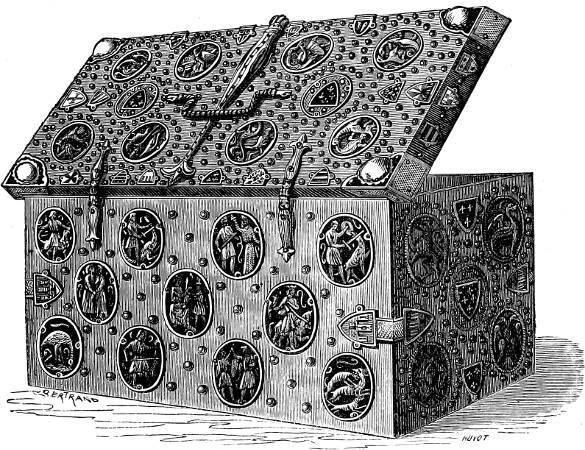

Fig. 286. Coffer containing the Hair-cloths of St. Louis, presented by Philippe le Bel, his grandson, to the Abbey of Notre-Dame-du-Lis, near Melun. The chest is in beech-wood, covered with metal, and with painted designs of the royal insignia of France and Castille, and various allegorical subjects.— Work of the Thirteenth Century, in the Louvre, Paris.

The Crusades were in reality but the general application, upon a larger scale, of those pilgrimages to the Holy Land which the inhabitants of Christian Europe had so long been performing. In the rear of the armed hosts marched with unfurled banners a tribe of infirm pilgrims, women, children, and old men (Fig. 288), led by priests in their sacerdotal vestments—undisciplined multitudes, into whose ranks inevitably crept a number of those miscreants who were the real authors of all the misdeeds with which history has reproached the Crusaders. As to the pilgrimages, the immediate result of this great movement of the European population towards Palestine was the creation, along the road which they had to travel,

of a number of receiving-houses, supported and managed by certain religious and military orders, who entertained the wearied and sick pilgrims, and helped them on their journey.

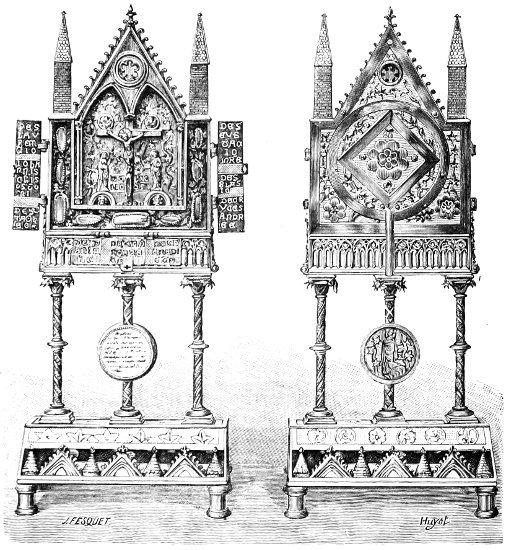

Fig. 287. Reliquary in chased copper (front and reverse), with movable Panels, and containing round the Crucifixion Scene, and in the space between the columns, Relics of Apostles, Fathers of the Church, Saints, and Martyrs. Flemish work of the Thirteenth Century, preserved in the Convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart, at Mons.

Fig. 288. Robert I., Duke of Normandy, father of William the Conqueror, seized with illness during his pilgrimage to Jerusalem (1035), is carried in his litter by negroes: hence his jocular saying, “I am being taken by demons into Paradise.” From a Miniature in the “Chroniques de Normandie,” a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century, in the Library of M. Ambroise Firmin Didot.

That model of pilgrims, the good King Louis IX., collected, in the course of his unsuccessful expeditions (1248–1270), a number of relics (Figs. 290 to 293, and 305). These, brought back to France as trophies of the crusade, were offered as gifts to ancient and

venerable churches already possessing many valuable relics, or deposited in new churches which were built expressly for their reception, as in the case of the Sainte Chapelle at Paris. And this brought about the increase of pilgrimages throughout Europe, in which the worship, not only of relics but of miraculous images, was ardently pursued. At the end of the thirteenth century, which was undoubtedly the most brilliant as it was the most solemn epoch of Christian art, in respect to the processional and itinerant acts of devotion, there were said to be no less than ten thousand Catholic sanctuaries, all of more or less celebrity, and each of which attracted its share of pilgrims, either for its Madonna or Notre-Dame. This was exclusive of the numberless images of Notre-Dame which were occasionally honoured by a special worship, and which were erected at cross-roads, at street-corners, and upon the fronts of houses, as a protection for the wayfarer and for the inhabitants of the locality. Many dioceses, such as those of Soissons and Toul, each contained from sixty to seventy places of pilgrimage.

Fig. 289. The Pilgrims of Emmaus. Pilgrim’s dress in the second half of the Thirteenth Century. Portion of the celebrated Altarpiece of Mareuil-en-Brie, reproduced in its entirety in the article “Liturgy and Ceremonies.”

The authentic titles of the principal pilgrimages, apart from those of Rome and Jerusalem, thus date from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Some, no doubt, were anterior to this period, but their origin, though attested by tradition, cannot be said to rest

upon any indisputable evidence. Of this nature are the celebrated devotions of Notre-Dame of Loretto, of our Lord’s robe at Trèves, of the seamless robe of Jesus Christ in the village of Argenteuil, near Paris, of St. Larme at Vendôme, of St. Face at Chambéry, of the blood of St. Januarius at Naples, of the stole of St. Hubert, &c.

Fig. 290. The Crown of Thorns brought into France. The three lower compartments represent: 1, the first visit of the king to the SainteChapelle, expressly built to receive the crown of thorns; 2, the reception of the crown, presented by Baldwin II., Emperor of Constantinople, and brought to Paris in 1239; 3, the adoration of the crown in the Sainte-Chapelle by the king and his mother, Blanche of Castille. Above are the Island of Cyprus, the Crusaders’ fleet, and a battle with the Saracens, as recalling the crusade of Louis IX. In the Burgundian Library, Brussels. (Fifteenth Century.)

Figs. 291 and 292.—1. The Nail used in the Crucifixion of our Lord, preserved in the Church of Santa Croce di Gerusalemme, at Rome. 2. The Holy Bit of Carpentras, brought to that town between 1204 and 1206. This is the bit which St. Helena forged for the horse of the Emperor Constantine from nails which had been driven into the holy cross. After the Engraving of M. Rohault de Fleury, in his work called “Mémoire sur les Instrumens de la Passion de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ.”

Fig. 293.—The Title or Superscription upon our Lord’s Cross: fragment of the piece of cedar-wood given to the Pope by St. Helena, and preserved in the Church of Santa Croce di Gerusalemme, at Rome.—The Inscription, which signifies “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” was in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, written backwards and in sunken characters; only a third remains. Fac-simile from M. Rohault de Fleury’s Engraving for his work called “Mémoires sur les Instrumens de la Passion de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ.”

Christian Rome, bedewed with the martyrs’ blood and enriched with their relics, has since the first ages of Christianity been the central object of the great majority of pilgrimages. Her three hundred churches have one after another been visited by a host of believers drawn thither by pious recollections, by all kinds of effectual acts of grace or indulgences, by an abundant hospitality, by a pompous ceremonial, and, above all, by the ardour of their faith. On great anniversaries, at jubilees and at the Inventions of the bodies of saints, the number of pilgrims multiplied indefinitely. As many as twelve hundred thousand have been known to have arrived in the course of a single day, from different parts of the world—pious bands which encamped around the walls of the Eternal City, their

Fig. 294. Touching the Relics of St. Philip. Fresco Painting by Andrea del Sarto, in the Cloister of the Church of the Annunziata, at Florence.

ranks being constantly added to by fresh arrivals during several consecutive months. Besides the basilica of St. Peter, Rome possessed several privileged sanctuaries which were at all periods the chief haunts of the pilgrims: these were the Church of Sta. Maria Maggiore, where the manger in which our Lord was born was seen; San Praxeas, the basilica which contained two thousand five hundred martyrs; San Giovanni Laterano, in which are the scala santa, the same steps blessed by the blood of Jesus Christ when He was wearing the crown of thorns, and which are only ascended by people upon their knees; San Pietro-in-Montorio, the crypt of which stands upon the spot where that apostle was crucified; San Sebastianofuor-gli-Muri, famous for its catacombs; San Paolo da Tre Fontane— miraculous springs which gushed from the ground with three leaps, just as St. Paul’s head rebounded three times from the ground when he was executed; San Paolo-fuori-le-Muri, where is preserved the crucifix which spoke to St. Bridget; San Lorenzo-fuori-le-Muri, where are interred the bodies of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence; Santa Croce di Gerusalemme (Fig. 293), a basilica founded by the august mother of St. Constantine on her return from a pilgrimage to Palestine; St. Cecilia, a church built upon the site of the house in which that saint lived, and containing the bath-room in which she suffered martyrdom; as well as twenty other churches which have been the cradles of the Christian religion, and which, by their origin, tradition, and relics, command the pious respect of those who visit them. No matter by what road the pilgrims travelled, they passed on their way to Rome a vast number of sanctuaries and stations which were dedicated either to the Virgin Mary or to illustrious saints (Fig. 294). Upon the sea-coast, the church of Our Guardian Lady and of Our Lady of Genesta, the tutelary guardians of the Gulf of Lyons and the Gulf of Genoa; and with them St. Martha and St. Magdalene; St. George, the legend of whose warlike exploit is reproduced in so many pictures; at Lucca, Our Lady of the Rose; in the Neapolitan States, Our Lady of the Commencement, Our Lady of the Conception, Our Lady of the Assumption, Our Lady of Naples, Our Lady of Mount St. Januarius; in Sicily, Our Lady of the Crown, St. Restituta, St. Agatha, but particularly St. Rosalie; towards the

eastern shores of the Ionian Sea, several virgins of Byzantine origin, who were worshipped conjointly with St. Nicholas and St. Spiridion; along the Adriatic other Madonnas and other saints, conspicuous among whom, like a precious pearl, shines the celebrated image known as Our Lady of Victory. It was in her honour that an Eastern emperor caused a triumphal car to be constructed, in order that she might be drawn through the streets of Constantinople whenever the empire was threatened with danger. Brought to Venice and deposited in the Church of St. Mark, she was looked upon as the safe-guard of the republic, and, in place of the triumphal car, a magnificent gondola was specially reserved for this image. From the days of Godfroy de Bouillon, who, with a part of the Crusaders, made a pilgrimage to Bari, on the “soil of Monseigneur St. Nicholas,” before pursuing his journey to Jerusalem, this august sanctuary became the scene of continuous devotions. Joinville, Froissart, Philippe Giraud de Vigneulles, and other chroniclers speak of the number of pilgrims who visited Bari to do honour to the relics of St. Nicholas. The miracles accomplished there through the intercession of the blessed Bishop of Myra, form a rich volume of legends dating from the eleventh century, when forty burghers of the town of Bari went into Asia Minor to rescue his precious body from the violence of the Saracens.

We must not be astonished at the profanities committed by the Mahometans at the places of pilgrimage in Palestine, since the cessation of the Crusades left these venerable sanctuaries at their mercy. It was to preserve the chapel of Nazareth from these outrages that God commanded his angels to carry it into a Christian country. According to a tradition confirmed by several papal bulls, the angels who carried off this chapel deposited it, on May 10th, 1291, at Rauneza, between Fiume and Tersatz, in Dalmatia. On the same night the Virgin Mary appeared in a dream to a dying priest named Alexander, and told him of the miracle. The chapel transported to Rauneza was no other than the house in which the divine mother of God had been born and had conceived the Redeemer. After her death the apostles had converted it into a

chapel; St. Peter had erected an altar in it, and St. Luke had with his own hands carved in cedar a statue of the Virgin for it. The priest who had had the vision rose from his bed cured of his disease, and went to prostrate himself before the holy image previous to making a public announcement of the apparition of the Virgin. The house of Nazareth was there standing to confirm the truth of his story. Then began the pilgrimages to Tersatz. The Emperor Rudolph, on being informed of this marvellous occurrence, sent several persons of distinction into Palestine to see whether the chapel of Nazareth had really been removed. Their report was of the most satisfactory character, and very soon the worship of Our Lady of Tersatz had become very general throughout the Danubian provinces. In order to preserve the treasure with which Providence had endowed this spot, the santa casa was surrounded by a wooden framework while the church of which it was to form the sanctuary was being built. But after standing for three years in Dalmatia, this holy house disappeared. Contemporary chroniclers relate that, on the 10th of December, 1291, it was carried up into the air by angels and borne across the Adriatic.

It appears that the santa casa, before taking up its definite position, halted near Recanati, upon a property belonging to two brothers who for eight months disputed its possession. In order to bring about a reconciliation between them, and chiefly, no doubt, because they were unwilling to leave this sanctuary at the mercy of these two jealous rivals, the angels bore it off once more, and finally deposited it in a field belonging to a poor widow of the name of Loreta—whence the denomination Our Lady of Loreta. Here may still be seen the santacasa, just as it came from Nazareth, but not as it was decorated, endowed, and enriched by the sumptuous devotion of the Middle Ages. Its treasures, valued at several million francs, already much diminished by the religious wars brought about by the great Western schism, ceased to accumulate in the sixteenth century during the struggle of the Church against Protestantism, and they were almost all carried off in 1796 by the pillaging armies of the French Republic. Nevertheless the fervour of the pilgrims was not in

the least abated, and the splendid church in which the santa casa was as it were enshrined, was too small to contain all the votive offerings brought thither from every part of the world. The popes had granted numerous indulgences to those who made this pilgrimage, which was the most celebrated as well as the most frequented of any outside Rome.

The legend of the pilgrimages, as marvellous in Spain as it was in Italy, always associated the worship of St. James with that of the Holy Virgin. After the ascension of our Lord and the descent of the Holy Ghost, Santiago the Iberian—St. James, as we call him—bid adieu to his elder brother St. John the Evangelist, and afterwards went to ask the Virgin for her blessing. She said to him, “Dear son, since thou hast chosen Spain, the country which I love best of all European lands, to preach the Gospel, take care to found there a church dedicated to me, in the town where you convert the greatest number of heathen.” Santiago then left Jerusalem, and crossing the Mediterranean, arrived at Tarragona, where, despite all his efforts, he only succeeded in converting eight persons.

Fig. 295. Our Lady of Mountserrat, with a Spanish Inscription signifying “Celestial abode of Our Lady of Mountserrat.” This mountain derives its name from its rocks being shaped like the teeth of a saw (sierra, saw). This symbolical saw is seen in the hands of the Infant Jesus. Reduced Fac-simile of a Woodcut of the Sixteenth Century, belonging to M. Bertin, publisher, of Paris.

But in the night of February 4th, A.D. 36, whilst he and his eight neophytes were sound asleep in the plain upon which Saragossa now stands, they were awaked by celestial music, and this music was the voice of angels celebrating the praises of the Virgin. Santiago prostrated himself with his face to the ground, and before him he saw the august mother of Christ, standing on a pillar of jasper, surrounded with angels, and with the same smile of ineffable sweetness which he had seen on her features when he left Jerusalem. “James, my son,” she said to him, “you must build me a church upon this very spot. Take the pillar upon which I am standing, place it, with my image upon its summit, in the midst of a sanctuary dedicated to me, and to the end of time it shall never cease to work miracles.” The apostle at once commenced the work, aided by his disciples, and the church was soon constructed. Such, according to the legend, was the origin of the cathedral and the pilgrimage of Our Lady of the Pillar (NuestraseñoradelPilar).

The Virgin of the Pillar (Virgo delPilar) was not the only one held in profound veneration by the Spaniards during the Middle Ages; every petty kingdom, every principality, every important town of the Iberian peninsula had its Madonna, its Señora, which attracted numerous pilgrims. Amongst them may be mentioned Our Lady of Mountserrat, in Catalonia (Fig. 295), Our Lady of France (laRena di Francia), half-way between Salamanca and Ciudad Rodrigo, and Our Lady of the Dice (Señora del Dado), in the kingdom of Leon— sanctuaries which stood in the midst of mountainous ranges, and which could only be reached on foot or with mules.

In a small town called El Padron—the Monument—which is but the ancient Iria, where Santiago, called James the Elder, taught (Fig. 296), and which was for a long time the guardian of his earthly remains, there flowed beneath the high altar of the church, which was dedicated to him, a stream of spring water, the ripple of which, like heavenly music, mingled with the prayers of the pilgrims, who were so numerous that their knees have worn holes in the stone slabs of the sanctuary. The body of the illustrious martyr, when brought from Compostella to Santiago, was laid upon a granite block

which was miraculously fashioned into a tomb, and it never emerged therefrom save as a phantom either to appear in vision before kings, prelates, and other pious persons who had invoked it, or to seize a lance and combat the enemies of Christianity. Thus, the legend tells us, he was seen in 946, riding a white horse, holding in his hand a banner emblazoned with a red cross (such as the knights of Santiago wear on the left side of their mantles), and marching at the head of the Christian barons against the Moors or Saracens.

The pilgrimage to St. James of Compostella was famous as early as the ninth century; people came with votive offerings from all parts of the Christian world. The road leading to this sanctuary was perpetually crowded with an army of pilgrims, and such continued to be the case throughout the Middle Ages. On returning to their own country, the pilgrims of “Monseigneur St. James” formed a regular order of Catholic chivalry; they kept up the pious devotions in which they had engaged during their pilgrimage, and maintained till their lives’ end the spirit of religious fellowship which had united them under the same banner.

Fig. 296. The Magician Armogenes, in the presence of the Compostella pilgrims, orders devils to bring him the apostle St. James (the legend of the saint gives the contrary version).—After a Miniature from “The Holy Scriptures,” a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century (Burgundian Library, Brussels).

France, notwithstanding her warlike spirit, did not pay so much honour to the warlike saints as did Italy and Spain to St. George and St. James, but she seems to have held in highest esteem the healing saints, as we may term them, such as St. Martin of Tours, St. Roch, St. Christopher, St. Blaze, St. Lazarus, &c., whose venerated relics have been the object of so many celebrated pilgrimages (Fig. 297). She has also rendered touching homage to certain specially holy women, the worship of whom has become almost national, such as St. Mary Magdalene and St. Martha, St. Barbara, St. Geneviève, &c. But in no country has the worship of the Virgin Mary been more general or more sublime than in France, where the mother of God had so many venerable sanctuaries; such as that of Our Lady of Puy, Our Lady of Liesse, Our Lady of Chartres, Our Lady of Rocamadour,

Our Lady of the Thorn, Our Lady of Auray, and Our Lady of Victory, amongst others.

Fig. 297. Thanksgivings made in a Chapel of Pilgrimage by a family carrying out a vow. It is believed that this is the chapel in which were preserved the relics of the saint in the Abbey of Mont St. Claude (Franche-Comté). French Picture of the Fifteenth Century, belonging to M. P. Lacroix.

One of the first altars erected in France to the Virgin Mary was that upon the summit of Mount Anicium, a volcanic rock near Velay, called Le Puy (from the Italian poggio, high mountain). St. George, bishop of the diocese, came to baptize a lady of the district, who became seriously ill, upon which an unknown voice bid her repair to Mount Anicium. Having obeyed this command, she fell into a quiet sleep, during which she saw a celestial female figure, wearing a crown of precious stones. “Who is this queen, so beautiful, so noble, and so gracious?” she inquired, addressing herself to one of the angelic host that surrounded her. The answer came: “This is the mother of the Son of God. She has selected this mountain for you to come and make your invocation; she bids you acquaint her faithful servant, Bishop George, of what has taken place. And now awake; you are cured of your illness.” The lady, filled with gratitude and faith, went to the bishop, who, when he had heard her story, prostrated himself to the ground, as if it were the Virgin herself who was speaking. Followed by his clergy, he then repaired to the miraculous rock. It was in the month of July; the sun was very hot, but the snow lay deep upon the table-land of the mountain. Suddenly a stag bounded forward and traced with his feet the plan of the sanctuary which was to be built upon that very spot, and then disappeared. The bishop at once saw that a fresh miracle had been wrought in confirmation of the first; he had the spot enclosed, and made a vow to erect a church there. This vow was executed by St. Evodius, seventh Bishop of Puy, in 223.

The statue of Our Lady of Puy, in cedar wood, blackened with age, was the work of the first Christians of Libanus, who executed it after the image of the Egyptian goddess Isis, sitting upright upon a stool, and holding upon her knee the Infant Jesus, swathed in fine linen as if he were a little mummy. This image was brought from the East by St. Louis in 1254.

The origin of the statue of Our Lady of Liesse also dates from the Crusades, which inundated France and the rest of Europe with so many images of the Holy Virgin. Thus, in 1131, Foulques d’Anjou, King of Jerusalem, entrusted the guard of the city of Beersheba to

the Knights Hospitallers of St. John, amongst the most distinguished of whom were the three brothers of the house of Eppes, near Laon. These knights having been taken prisoners, the Sultan determined to make them become Mahometans, and imprudently selected his daughter Ismeria to effect the work of conversion. But she forgot the object of her mission, and allowed herself to be converted to Christianity by the arguments of the three knights. She asked them to carve for her an image of the Holy Virgin, and though they were utterly ignorant of the art, they began an image which angels came down from heaven to complete. The Virgin appeared to the Sultan’s daughter, encouraged her in her project to set the three captives at liberty, and advised her to follow them in her flight. At about midnight she went to the prison, the doors of which opened before her, as did those of the city. Ismeria bore in her arms the image of the Virgin, and the sovereign virtue of this talisman overcame all obstacles. The fugitives, who had gone to sleep upon Egyptian soil, woke up to find themselves in front of the Château d’Eppes, and the statuette, sparkling with light, selected the place which it wished to occupy in the middle of a wood. Ismeria caused to be erected upon this very spot a plain chapel, whilst in the town of Laon a cathedral was built, dedicated to Our Lady of Liesse. Since that period the great basilica and the tiny chapel have shared between them the worship of the crowd of pilgrims which the startling miracles have attracted thither. Both structures suffered from the fury of the Huguenots in the sixteenth century, but the miraculous image of the Virgin has always escaped from sacrilegious outrage.

Fig. 298.—Ancient Banner of the City of Strasburg, on which is represented the Image of Our Lady, to whom the city was dedicated about the middle of the Thirteenth Century; the lilies running round it are the emblem of the Virgin’s purity. A Memorial of the Thirteenth Century, burnt during the bombardment of Strasburg in 1870. From a copy published in the “Dictionnaire du Haut et du Bas-Rhin,” by M. Ristelhuber.

Fig. 299. Removal, by St. Bodillon and the Chevalier Gérard de Roussillon, of the Body of Mary Magdalene to the Church of Vézelay (Yonne). After a Miniature in the “Chroniques de Hainaut,” a Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century, in the Burgundian Library, Brussels.]

There is much analogy between the worship of the patronal Virgin of the country round Chartres and that of the Virgin of the Pillar at Saragossa. The two statues are alike in regard to posture, costume, and general character, and moreover they date back to the same epoch—namely, the fourth or fifth century. The Chartres cathedral, though ancient—for it was in existence during the seventh century