Evidence-based practice in surgery

Critical appraisal for developing evidence-based practice can be obtained from a number of sources, the most reliable being randomised controlled clinical trials, systematic literature reviews, metaanalyses and observational studies. For practical purposes three grades of evidence can be used, analogous to the levels of ‘proof’ required in a court of law:

1. Beyond all reasonable doubt. Such evidence is likely to have arisen from high-quality randomised controlled trials, systematic reviews or high-quality synthesised evidence such as decision analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis or large observational datasets. The studies need to be directly applicable to the population of concern and have clear results. The grade is analogous to burden of proof within a criminal court and may be thought of as corresponding to the usual standard of ‘proof’ within the medical literature (i.e. P <0.05).

2. On the balance of probabilities. In many cases a high-quality review of literature may fail to reach firm conclusions due to conflicting or inconclusive results, trials of poor methodological quality or the lack of evidence in the population to which the guidelines apply. In such cases it may still be possible to make a statement as to the best treatment on the ‘balance of probabilities’. This is analogous to the decision in a civil court where all the available evidence will be weighed up and the verdict will depend upon the balance of probabilities.

3. Not proven. Insufficient evidence upon which to base a decision, or contradictory evidence.

Depending on the information available, three grades of recommendation can be used:

a. Strong recommendation, which should be followed unless there are compelling reasons to act otherwise.

b. A recommendation based on evidence of effectiveness, but where there may be other factors to take into account in decisionmaking, for example the user of the guidelines may be expected to take into account patient

preferences, local facilities, local audit results or available resources.

c. A recommendation made where there is no adequate evidence as to the most effective practice, although there may be reasons for making a recommendation in order to minimise cost or reduce the chance of error through a locally agreed protocol.

Evidence where a conclusion can be reached ‘ beyond all reasonable doubt’ and therefore where a strong recommendation can be given. This will normally be based on evidence levels:

• Ia. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

• Ib. Evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial

• IIa. Evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation

• IIb. Evidence from at least one other type of quasiexperimental study.

Evidence where a conclusion might be reached ‘on the balance of probabilities’ and where there may be other factors involved which influence the recommendation given. This will normally be based on less conclusive evidence than that represented by the double tick icons:

• III. Evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies and case–control studies

• IV. Evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both.

Evidence that is associated with either a strong recommendation or expert opinion is highlighted in the text in panels such as those shown above, and is distinguished by either a double or single tick icon, respectively. The references associated with doubletick evidence are listed as Key References at the end of each chapter, along with a short summary of the paper's conclusions where applicable. The full reference list for each chapter is available in the ebook. The reader is referred to Chapter 1, ‘Evaluation of surgical evidence’ in the volume Core Topics in General and Emergency Surgery of this series, for a more detailed description of this topic.

Contributors

Omer Aziz, MBBS, BSc(Hons), DIC, PhD, FRCS

Consultant Colorectal, General, and Laparoscopic Surgeon, Colorectal and Peritoneal Oncology Centre; Honorary Senior Lecturer, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

John Bunni, MBChB(Hons), DipLapSurg, FRCS [ASGBI Medal]

Consultant Colorectal and General Surgeon, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Bath; Honorary Lecturer, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

Sue Clark, MA, MD, FRCS(Gen Surg), EBSQ(Coloproctology)

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow; Adjunct Professor of Surgery, Imperial College, London, UK

Eric J. Dozois, MD, FACS, FACRS Colon and Rectal Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Anton V. Emmanuel, BSc, MD, FRCP

Department of Gastroenterology (GI Physiology), University College London, UK

Nicola S. Fearnhead, BMBCh, FRCS, DM

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Pasquale Giordano, MD, FRCS

Consultant Surgeon, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal London Hospital; Honorary Senior Lecturer Queen Mary University London, London, UK

Simon Gollins, BMBCh, MA, DPhil, MRCP, FRCR

Consultant Clinical Oncologist and Oncology Clinical Director, North Wales Cancer Treatment Centre, Rhyl, UK

Gianpiero Gravante, MBBS, MD, PhD

Surgical Registrar, Colorectal Surgery, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester, UK

Adam Haycock, MBBS, MRCP, BSc, MD

Wolfson Unit for Endoscopy, St Mark's Hospital, London, UK

David J. Humes, BSc, MSc, MBBS, PhD, FRCS

Associate Professor of Surgery, Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Centre, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Scott R. Kelley, MD, FACS, FASCRS

Assistant Professor of Surgery, Colon and Rectal Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Robin Kennedy, MS, FRCS

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow; Adjunct Professor of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College, London, UK

Andrew Latchford, BSc(Hons), MBBS, FRCP, MD

Consultant Gastroenterologist, St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow, UK

Paul-Antoine Lehur, MD, PhD Professor, Digestive and Endocrine Surgery, University Hospital, Nantes, France

Brendan J. Moran, MBBCh, FRCS, FRCSI, MCh Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Hampshire Hospitals Foundation Trust, Basingstoke, UK

Robin K.S. Phillips, MBBS, MS, FRCS Professor of Colorectal Surgery, Imperial College London; Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow, UK

Eanna Ryan, MBBCh, BAO, MD Candidate Surgical Professorial Unit, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Alexis M.P. Schizas, BSc, MBBS, MSc, MD, FRCS(Gen Surg)

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Guy's and St Thomas' Hospitals, London, UK

John H. Scholefield, MBChB, FRCS, ChM (Distinction)

Professor of Surgery, Head of Division, Division of GI Surgery, University Hospital, Nottingham, UK

David Sebag-Montefiore, MBBS, FRCP, FRCR

Professor of Clinical Oncology, University of Leeds and Leeds Cancer Centre, St James's University Hospital, Leeds, UK

Robert J.C. Steele, MD, FRCSEd, FRCSEng, FCSHK, FRCPE, MFPH(Hon), FRSE

Professor of Surgery, Head of Department of Surgery, University of Dundee Medical School, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, UK

Gregory P. Thomas, MBBS, BSc, FRCS, MD

Resident Surgical Officer, St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow, UK

Siwan Thomas-Gibson, MD, FRCP

Consultant Gastroenterologist, Wolfson Unit for Endoscopy, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow; Honorary Senior Lecturer, Surgery, Imperial College, London, UK

Mark W. Thompson-Fawcett, MBChB, MD, FRACS

Associate Professor, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Phil Tozer, MBBS, FRCS, MD(Res)

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, and Lead, Robin Phillips Fistula Research Unit, St Mark’s Hospital, Harrow, UK

Carolynne Vaizey, MBChB, MD, FRCS(Gen), FCS(SA)

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow, UK

Janindra Warusavitarne, BMed, FRACS, PhD

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, St Mark's Hospital, Harrow, UK

Des Winter, MB, FRCSI, MD, FRCS(Gen)

Consultant Surgeon, Centre for Colorectal Disease, St Vincent's University Hospital and University College, Dublin, Ireland

Andrew B. Williams, MBBS, BSc, MS, FRCS

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon, Director Pelvic Floor Unit, Colorectal Surgery, Guy's and St Thomas' Hospitals, London, UK

Anorectal investigation

Alexis M.P. Schizas

Andrew B. Williams

Introduction

Many tests are available to investigate anorectal disorders, each only providing part of a patient's assessment, so results should be considered together and alongside the clinical picture derived from a careful history and physical examination. Investigations provide information about structure alone, function alone, or both, and have been directed to five general areas of interest: faecal incontinence, constipation (including Hirschsprung's disease), anorectal sepsis, rectal prolapse (including solitary rectal ulcer syndrome) and anorectal malignancy.

Anatomy and physiology of the anal canal

The adult anal canal is approximately 4 cm long and begins as the rectum narrows, passing backwards between the levator ani muscles. There is in fact wide variation in length between the sexes, particularly anteriorly, and between individuals of the same sex. The canal has an upper limit at the pelvic floor and a lower limit at the anal opening. The proximal canal is lined by simple columnar epithelium, changing to stratified squamous epithelium lower in the canal via an intermediate transition zone just above the dentate line. Beneath the mucosa is the subepithelial tissue, composed of connective tissue and smooth muscle. This layer increases in thickness throughout life and forms the basis of the vascular cushions thought to aid continence.

Outside the subepithelial layer the caudal continuation of the circular smooth muscle of the

rectum forms the internal anal sphincter, which terminates distally with a well-defined border at a variable distance from the anal verge. Continuous with the outer layer of the rectum, the longitudinal layer of the anal canal lies between the internal and external anal sphincters and forms the medial edge of the intersphincteric space. The longitudinal muscle comprises smooth muscle cells from the rectal wall, augmented with striated muscle from a variety of sources, including the levator ani, puborectalis and pubococcygeus muscles. Fibres from this layer traverse the external anal sphincter forming septa that insert into the skin of the lower anal canal and adjacent perineum as the corrugator cutis ani muscle.

The striated muscle of the external sphincter surrounds the longitudinal muscle and between these lies the intersphincteric space. The external sphincter is arranged as a tripartite structure, classically described by Holl and Thompson and later adopted by Gorsch and by Milligan and Morgan. In this system, the external sphincter is divided into deep, superficial and subcutaneous portions, with the deep and subcutaneous sphincter forming rings of muscle and, between them, the elliptical fibres of the superficial sphincter running anteriorly from the perineal body to the coccyx posteriorly. Some consider the external sphincter to be a single muscle contiguous with the puborectalis muscle, while others have adopted a two-part model. The latter proposes a deep anal sphincter and a superficial anal sphincter, corresponding to the puborectalis and deep external anal sphincter combined, as well as the fused superficial and subcutaneous sphincter of the tripartite model. Anal endosonography (AES) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have not

resolved the dilemma, although most authors report a three-part sphincter where the puborectalis muscle is fused with the deep sphincter.1,2 The external anal sphincter is innervated by the pudendal nerve (S2–S4), which leaves the pelvis through the lower part of the greater sciatic notch, where it passes under the pyriformis muscle. It then crosses the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament to enter the ischiorectal fossa through the lesser sciatic notch or foramen via the pudendal (or Alcock's) canal.

The pudendal nerve has two branches: the inferior rectal nerve, which supplies the external anal sphincter and sensation to the perianal skin; and the perineal nerve, which innervates the anterior perineal muscles together with the sphincter urethrae and forms the dorsal nerve of the clitoris (or penis). Although the puborectalis receives its main innervation from a direct branch of the fourth sacral nerve root, it may derive some innervation from the pudendal nerve.

The autonomic supply to the anal canal and pelvic floor comes from two sources. The fifth lumbar nerve root sends sympathetic fibres to the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses, and the parasympathetic supply is from the second to fourth sacral nerve roots through the nervi erigentes. Fibres of both systems pass obliquely across the lateral surface of the lower rectum to reach the region of the perineal body.

The internal anal sphincter has an intrinsic nerve supply from the myenteric plexus together with an additional supply from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Sympathetic nervous activity is thought to enhance and parasympathetic activity to reduce internal sphincter contraction. Relaxation of the internal anal sphincter may be mediated by non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic nerve activity via the neural transmitter nitric oxide. Anorectal physiological studies alone cannot separate the different structures of the anal canal; instead, they provide measurements of the resting and squeeze pressures along the canal. Between 60% and 85% of resting anal pressure can be attributed to the action of the internal anal sphincter.3 The external anal sphincter and the puborectalis muscle generate the maximal squeeze pressure.3 Symptoms of passive anal leakage (where the patient is unaware that episodes are happening) are attributed to internal sphincter dysfunction, whereas urge symptoms and frank incontinence of faeces are due to external sphincter problems.4

Faecal continence is maintained by the complex interaction of many different variables. Stool must be delivered at a manageable rate from the colon into a compliant rectum of adequate volume. The consistency of this stool should be appropriate and accurately sensed by the sampling mechanism. Sphincters should be intact and able to contract

adequately to produce pressures sufficient to prevent leakage of flatus, liquid and solid stool. For effective defecation there needs to be coordinated relaxation of the striated muscle components with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure to expel the rectal contents. The structure of the anorectal region should prevent herniation or prolapse of elements of the anal canal and rectum during defecation. Because of the complex interplay between the factors involved in continence and faecal evacuation, a wide range of investigations is needed for full assessment. A defect in any one element of the system in isolation is unlikely to have great functional significance and so in most clinical situations there is more than one contributing factor.

Rectoanal inhibitory reflex

Increasing rectal distension is associated with transient reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter and contraction of the external anal sphincter, known as the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (Fig. 1.1). The exact neurological pathway for this reflex is unknown, although it may be mediated via the myenteric plexus and stretch receptors in the pelvic floor. Patients with rectal hyposensitivity have higher thresholds for rectoanal inhibitory reflex; it is absent in patients with Hirschsprung's disease, progressive systemic sclerosis, Chagas' disease, and initially absent after a coloanal anastomosis, although it rapidly recovers.

The rectoanal inhibitory reflex may enable rectal contents to be sampled by the transition zone mucosa to allow discrimination between solid, liquid and flatus. The rate of recovery of sphincter tone after this relaxation differs between the proximal and distal canal, which may be important in maintaining continence.5

Further studies investigating the role of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex in incontinent patients show that as rectal volume increases, greater sphincter relaxation is seen, whereas constipated patients have a greater recovery velocity of the resting anal pressure in the proximal anal canal. There is a longer recovery time back to resting pressure in patients with faecal incontinence.6

Manometry

A variety of different catheter systems can be used to measure anal pressure and it is important to note that measurements differ depending on which is employed. Systems include microballoons filled with air or water, microtransducers and water-perfused

catheters. These may be hand-held or automated. Hand-held systems are withdrawn in a measured stepwise fashion with recordings made after each step (usually of 0.5–1.0-cm intervals); this is called a station pull-through. Automated withdrawal devices allow continuous data recording (vector manometry).

Water-perfused catheters use hydraulic capillary infusers to perfuse catheter channels, which are arranged either radially or obliquely staggered. Each catheter channel is then linked to a pressure transducer (Fig. 1.2). Infusion rates of perfusate (sterile water) vary between 0.25 and 0.5 mL/min per channel. Systems need to be free from air bubbles, which may lead to inaccurate recordings, and must avoid leakage of perfusate onto the perianal skin, which may lead to falsely high resting pressures due to reflex external sphincter action. Perfusion rates should remain constant, because faster rates are associated with higher resting pressures, while larger diameter catheters lead to greater recorded pressure. 7

Balloon systems may be used to overcome some of these problems and may be more representative of pressure generated within a hollow viscus than recordings using a perfusion system. They are not subject to the same problems as a perfusion system when canal pressures are radially asymmetrical.7

Balloons can be filled with either air or water. Over the range of balloon sizes used (diameter 2–10 mm), diameter appears to have less of an effect on the

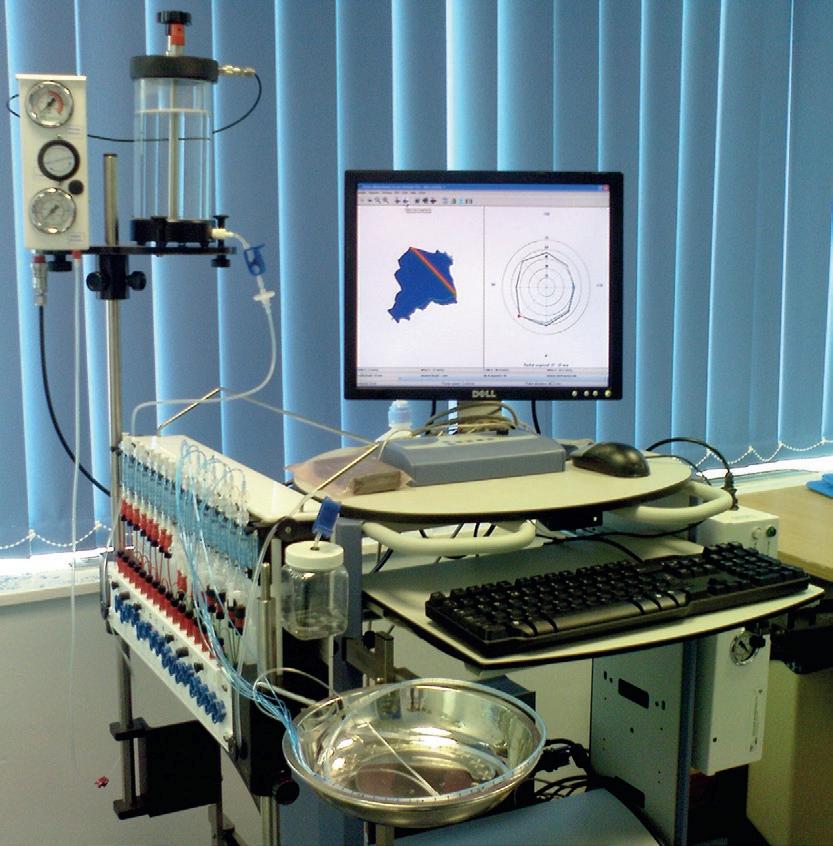

system used for anorectal manometry. Standard water perfusion set-up plus computer interface for anorectal manometry. The screen shows a vector volume profile.

recorded than it does with water-perfused catheter systems.

Microtransducers that can accurately measure canal pressure continue to be developed, but they are expensive and fragile.

Figure 1.1 • Normal rectoanal inhibitory reflex.

Figure 1.2 • Perfusion

High-resolution anal manometry uses the same catheters as standard manometry but updated software presents the information in a new way that may increase its clinical utility, especially when used to produce a three-dimensional picture of the anal canal. High-definition manometry uses closely spaced solid-state sensors simultaneously to measure circumferential pressures in the rectum and throughout the anal canal, so there is no need to perform a station pull-through manoeuvre.8

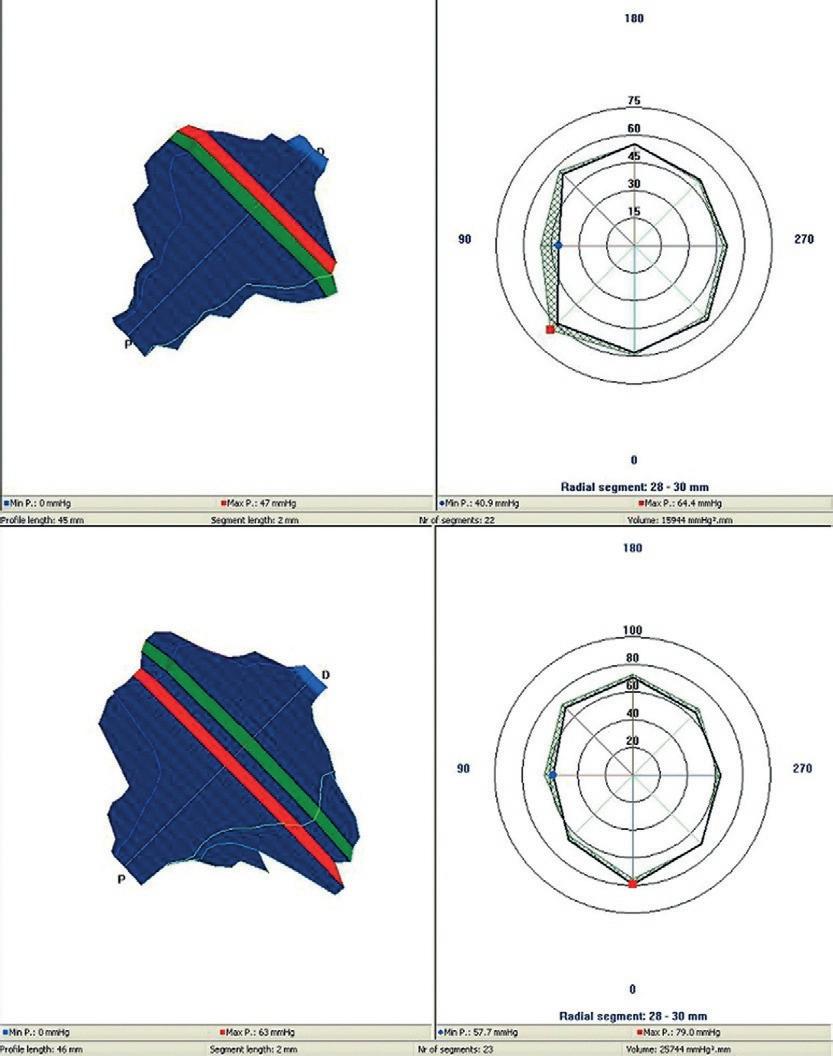

Three-dimensional anal canal manometry (vector volume manometry) utilises a radially arranged catheter setting (commonly eight-channel) that is automatically withdrawn from the anal canal during rest and squeeze, and computer software that produces a three-dimensional reconstruction of the anal canal (Fig. 1.3).9 Three-dimensional manometry is also possible with high definition anal canal manometry. These systems can assess radial asymmetry or vector symmetry index (i.e. how far the radial symmetry of the anal canal differs from a perfect circle, which has a radial asymmetry of 0% or vector symmetry index of 1). Sphincter defects are associated with symmetry indices of 0.6 or less.

Three-dimensional anal canal manometry may differentiate between idiopathic and traumatic faecal incontinence by showing global external sphincter weakness rather than a localised area of scarred sphincter indicated by an asymmetrical

Figure 1.3 • Normal vector volume at squeeze and at rest. Note that asymmetry of the sphincter contour can be normal.

vectogram.9,10 Anal vector manometry has been extensively used to assess obstetric anal sphincter injury. Following caesarean section, no change in anal pressures is seen; however, after vaginal delivery a fall in rest and squeeze pressures occurs.11 The reduction in pressures has been shown to be greatest after a third- or fourth-degree tear confirmed on AES. Functional anal sphincter length and vector volumes have been shown to decrease both at rest and during contraction after obstetric anal sphincter injury.12 Vector volumes are decreased further in women with persistent flatus incontinence.

Pressure changes in the anal canal can be measured in a number of ways and each method has been validated for its repeatability and reproducibility, although individual methods are not interchangeable.13 Although the correlation between measurements made using different systems and catheters is good, the absolute values are different, so that when comparing the results of different studies, it is essential to consider the method used to obtain the pressure measurements.

Significant variation exists in the results of anorectal manometry in normal asymptomatic subjects. Men have higher mean resting and squeeze pressures.14 Pressures decline after the age of 60 years, changes most marked in women.15 These facts must be considered when selecting appropriate control subjects for clinical studies. Normal mean anal canal resting tone in healthy adults is 50–100 mmHg. Resting tone increases in a cranial to caudal direction along the canal such that the maximal resting pressure is found 5–20 mm from the anal verge.3,16 The high-pressure zone (the part of the anal canal where the resting pressure is >50% of the maximum resting or squeeze pressure) is similar at rest between men and women (20 mm in length) but longer in men than women when squeezing (31 mm vs 23 mm).16 In a normal individual the rise in pressure on maximal squeezing should be at least 50–100% of the resting pressure (usually 100–180 mmHg).17 Reflex contraction of the external sphincter should occur when the rectum is distended, on coughing, or with any rise in intra-abdominal pressure.

In the assessment of patients with faecal incontinence, both resting and maximal squeeze pressures are significantly lower in patients with incontinence than in matched controls,18 but there is considerable overlap between the pressures recorded in patients and controls.19

Ambulatory manometry

The use of continuous ambulatory manometry to record rectal and anal canal pressures20 has provided

information on the functioning of the sphincter mechanism in a more physiological situation. The generation of giant waves of pressure in the rectum or neorectum may relate to episodes of incontinence in patients after restorative proctocolectomy. Ambulatory manometry has also identified patients in whom episodes of internal sphincter relaxation are not accompanied by reflex external sphincter contraction,21 a finding that may prove useful in selecting patients likely to benefit from biofeedback treatment.

Anal and rectal sensation

The anal canal is rich in sensory receptors,22 including those for pain, temperature and movement, with the somatic sensation of the anal transitional mucosa being more sensitive than that of the perianal skin. In contrast, the rectum is relatively insensitive to pain, although crude sensation may be transmitted by the nervi erigentes of the parasympathetic nervous system.23

A variety of methods have been used to measure anal sensation. Initial assessment of anal sensation used a stiff bristle to detect light touch in the anal canal, and hot and cold metal rods to detect temperature sensation.22 Thermal sensation has been assessed with water-perfused thermodes; normal subjects can detect a change in temperature of 0.92°C.24 The ability of the mucosa to detect a small electrical current can be assessed by the use of a double platinum electrode and a signal generator providing a square wave impulse at 5 Hz of 100 μs duration. The lowest recorded current of three readings at the point at which the subject feels a tingling or pricking sensation in the anal canal is noted as the sensation threshold. Normal electrical sensation for the most sensitive area of the anal canal (the transition zone) is 4 mA (2–7 mA). Rectal mucosal electrical sensation may also be measured using the same technique as that used for anal mucosal electrical sensation measurement, with slight modification of the stimulus (500 μs duration at a frequency of 10 Hz).23

The sensation of rectal filling is measured by progressively inflating a balloon placed within the rectum or by intrarectal saline infusion.23 Normal perception of rectal filling occurs after inflation of 10–20 mL, the sensation of the urge to defecate occurs after 60 mL, and normally up to 230 mL is tolerated in total before discomfort occurs.23

Temperature sensation may be vital in the discrimination of solid stool from liquid and flatus, 24 and is reduced in patients with faecal incontinence. It is thought that this sensation is important in the sampling reflex, although this is brought into question by the fact that the sensitivity of the anal mucosa to temperature change is not great enough to detect the very slight temperature gradient between the rectum and anal canal.

Anal mucosal electrical sensation threshold increases with age and thickness of the subepithelial layer of the anal canal. Anal canal electrical sensation is reduced in idiopathic faecal incontinence, diabetic neuropathy, descending perineum syndrome and haemorrhoids.26 There are differing reports on whether there is any correlation between electrical sensation and measurement of motor function of the sphincters (pudendal terminal motor latency and single-fibre electromyography).

The sampling mechanism and maintenance of faecal continence are complex multifactorial processes, as seen by the fact that the application of local anaesthetic to the sensitive anal mucosa does not lead to incontinence and in some individuals actually improves continence.

Rectal compliance

The clinical use of these measurements may be limited due to the large inter- and intra-subject variation in values and the wide normal range, reducing the discriminatory value of this technique as a clinical investigation.25

The relation between changes in rectal volume and the associated pressure changes is termed compliance, which is calculated by dividing the change in volume by the change in pressure. Compliance is measured by inflating a rectal balloon with saline or air or by directly infusing saline at physiological temperature into the rectum. In the former method, the filling of the rectal balloon can be either incremental or continuous. When continuous inflation of the rectal balloon is used, the rate of inflation should be 70–240 mL/min.25 Mean rectal compliance is about 4–14 mL/cmH2O, with pressures of 18–90 cmH2O at the maximum tolerated volume.27 Reports on the reproducibility of the measurement of rectal compliance are varied and many have found great variation within the same subject;25,27 the most reproducible measurement is usually the maximum tolerated volume. The use of the barostat to measure rectal compliance has been shown to be reproducible at pressures of between 36 and 48 mmHg. The compliance of the rectum does not differ between men and women up to the age of 60 years, but after this age women have more compliant rectums. Compliance is reduced in Behçet's disease and Crohn's disease and after radiotherapy in a dose-related fashion. It is also reduced in irritable bowel syndrome.

The association between changes in rectal compliance and faecal incontinence is less clear. Some state that compliance is normal in incontinence whereas others have found a reduction in compliance associated with faecal incontinence,18 although changes in compliance may be secondary to the incontinence and not causative. Altered compliance may play a role in soiling and constipation associated with megarectum.

Pelvic floor descent

Parks et al. first described the association between excessive descent of the perineum and anorectal dysfunction, and subsequently it has been described in several conditions: faecal incontinence, severe constipation, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and anterior mucosal and full-thickness rectal prolapse. The presumption in all these conditions is that abnormal perineal descent, especially during straining, causes traction and damage to the pudendal and pelvic floor nerves, leading to progressive neuropathy and muscular atrophy. Irreversible pudendal nerve damage occurs after a stretch of 12% of its length, and often the descent of the perineum in these patients is of the order of 2 cm, which is estimated to cause pudendal nerve stretching of 20%.

Descent of the perineum was initially measured using the St Mark's perineometer. The perineometer is placed on the ischial tuberosities and a movable Perspex cylinder is positioned on the perineal skin. The distance between the level of the perineum and the ischial tuberosities is measured at rest and during straining.28 Negative readings indicate that the plane of the perineum is above the tuberosities and a positive value indicates descent below this level. In normal asymptomatic adults, the plane of the perineum at rest should be 2.5 ± 0.6 cm, descending to +0.9 ± 1.0 cm on straining. When measured using dynamic proctography, similar measurements of pelvic floor descent are obtained. The anorectal angle normally lies on a line drawn between the coccyx and the most anterior part of the pubis, and descends by 2 ± 0.3 cm on straining. Excessive perineal descent is found in 75% of subjects who chronically strain during defecation. The degree of descent correlates with age and is greater in women. Although increased perineal descent on straining has been shown to be associated with features of neuropathy, namely decreased anal mucosal electrical sensitivity and increased pudendal nerve terminal motor latency, not all patients with abnormal descent have abnormal neurology.29 Perineal descent is also associated with faecal incontinence, although the degree of incontinence and the results of anorectal manometry do not correlate with the extent of pelvic floor laxity.30

Electrophysiology

Neurophysiological assessment of the anorectum includes assessment of the conduction of the pudendal and spinal nerves, and electromyography (EMG) of the sphincter.

Electromyography

Electromyographic traces can be recorded from the separate components of the sphincter complex, both at rest and during active contraction of the striated components. Initially, EMG was used to map sphincter defects before surgery, but AES is now so superior in its ability to map defects and is so much better tolerated by patients31 that EMG has largely become a research tool. Broadly, two techniques of EMG are used: concentric needle studies and singlefibre studies.

Concentric needle EMG records the activity of up to 30 muscle fibres from around the area of the needle both at rest and during voluntary squeeze. The amplitude of the signal recorded correlates with the maximal squeeze pressure,32 polyphasic longduration action potentials indicating reinnervation subsequent to denervation injury. The main use of this technique has been in the confirmation and mapping of sphincter defects. Examination of puborectalis EMG may be more sensitive than cinedefecography in the detection of paradoxical puborectalis contraction in obstructed defecation,33 although paradoxical puborectalis contraction is also present in normal subjects.

The use of an anal plug or sponge can record global electrical activity from the anal sphincters,32 EMG amplitudes recorded in this way correlating with voluntary squeeze pressure. EMG performed using a needle has a smaller recording area (25 μm diameter) and the action potential from individual motor units is recorded. Denervated muscle fibres can regain innervation from branching of adjacent axons, leading to an increase in the number of muscle fibres supplied by a single axon. With multiple readings (an average of 20) using this small-diameter needle, the mean fibre density (MFD) for an area of sphincter can be calculated (i.e. the mean number of muscle action potentials per unit area or axon). Denervation and subsequent reinnervation are also indicated by neuromuscular ‘jitter’, which is caused by variation in the timing of triggering and non-triggering potentials.34 An increase in sphincter MFD is often found in cases of idiopathic incontinence and is associated with recognised histological changes in sphincter structure. Atrophic sphincter muscle shows a loss of the characteristic mosaic pattern of distribution of type 1 and type 2 muscle fibres. There is also selective muscle fibre hypertrophy together with fibro-fatty fibre

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Suomen Kansan Vanhoja Runoja ynnä myös

Nykyisempiä Lauluja 4

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Suomen Kansan Vanhoja Runoja ynnä myös Nykyisempiä Lauluja 4

Compiler: Zacharias Topelius

Release date: February 16, 2024 [eBook #72976]

Language: Finnish

Original publication: Helsinki: J. Simeliuksen leski, 1829

Credits: Tuula Temonen *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUOMEN KANSAN VANHOJA RUNOJA YNNÄ MYÖS NYKYISEMPIÄ LAULUJA 4 ***

Koonnut ja pränttiin antanut

Z. TOPELIUS

Läänin Lääkäri ja Ritari

Helsingin Kaupungissa, Präntätty J. Simeliuksen Lesken tykönä, 1829.

Laulavat Lapinni lapset

Vesi-maljan juotuahan

Petäjäisessä pesässä

Honkasessa huonehessa;

Miksi en minähi laula

Suulta suurukselliselta

Oluelta ohraselta

Ruualta rukihiselta.

SUOMEN KANSAN VANHOJA RUNOJA YNNÄ MYÖS NYKYISEMPIÄ LAULUJA IV

Sisällä-pito.

Vanhoja Runoja.

Esi-puhe.

Kontion Synty.

Riien Synty.

Pistoksen Synnyn alku.

Vaapsahaisen Sanat.

Hiiren Sanat.

Pakkasen Sanat.

Tulen Sanat.

Lapsen Saajan Sanat. Imehiä.

Jauho-Runo.

Tarttuman Loihtu.

Nykyisempiä Runoja.

Viinan ryyppäämisestä. Kirpusta.

Muurarinen ja Kärvänen.

Vuori Synnyttävä.

Heinä-Sirkka ja Muurainen.

Muistutus.

Esi-puhe.

Kontion Synnyn, Riien Synnyn, ja Pistoksen Synnyn on Kajanin tienoilta minullen laittanut Kappalainen Suomus-Salmesa Herra C.

Saxa. Vaapsajaisen, hiiren ja Pakkaisen Sanat ovat Kalajoen

Pitäjästä; Tulen Sanat Vuokkiniemeltä; Lapsen Saajan Sanat ja Jauho-Runo Kemistä; Imehet ja tarttuman Loihtu Savon maalta.

Näitä Runoja kokoillessani, joista vielä yksi tai kaksi vihkoa mahtaa ilmantua, olen keksinyt että siellä ja täällä, erinomattain vanhoisa

Pappi-suvuisa löytyypi kaikenmoisia Runokirjotukksia, vanhoista ajoista säilytettynnä, Jonka tähden on minun nöyrä rukoukseni, että maanmiehet, joilla tämänlaisia kätköjä olisi, tahtoisivat niitä minullen toimittaa, jotta ne täsä kokouksesa saisivat siansa. Ehkä vailinaisina otetaan ne kiitollisuudella vastaan, niin muodoin kuin monesta ainehsta täysinäinen työ helpommasti valmistetaan.

Myös nykyisempiä Runon Seppiä, jotka soisivat laulujansa julistetuiksi, vaadin ja kehoitan minä että niitä tänne lähättäisit.

Minun asunopaikkani on Nyy-Carlebyyn tai Joensuun kaupungisa Pohjan maalla.

Kontion Synty.

Kulkia, metän Kuningas, Metän käyjä käyretyinen, Hilli Ukko, halli parta

Miss' on Ohto syntynynnä, Harva karva kasvanunna, Saatuna sini saparo?

Tuoll' on Ohto syntynynnä, Saatuna sini saparo, Pimeässä Pohjolassa,

Tarkassa Tapiolassa, Juuressa nyryn närien, Vieressä vihannan viian, Luona karkean karahkan.

Jos lähen Ohon oville, Tasa-kärsän tanterille, Pikku-silmäsen pihalle, Kattellani kuoltoani, Lyhyt on jalka, lysmä polvi, Tasa-kärsä talleroinen.

Annikki tytär Tapion, Mielikki metän emäntä, Joka on pienin piikojahan, Paras palkkalaisiahan, Kytke kiinni koiriasi, Rakentele rakkiasi, Kuusamisehen kujahan, Talasehen tammisehen, Tullessani tanhuville, Jalon Ohtosen oville.

Kukas Ohtosen sukesi, Harvo karvan kasvatteli?

Mielikki metän emäntä Sepä Ohtosen sukesi, Harva karvan kasvatteli

Alla kuusen kukka latvan, Kukka latvan, kulta lehvän.

Koska korpien Kuningas Kaikoaapi kammiosta, Linnastahan lähtenöövi,

Tuometar, Tapion neiti,

Mielikki metän emäntä,

Veäs kynnet viertehellä, Hampahat meellä hauvo,

Jot' ei koske konnanana, Liikuta lipeänänä

Karjaa, maita kulkiessa!

Neityt Maria Emoinen, Rakas äiti armollinen, Kuo mulle kulta-kangas,

Vaippa vaskinen vanuta, Jolla karjan kaihtesisin,

Saara-sorkat suojeleisin

Kuusiaisen kulkehissa,

Ohto pojan astuissa, Matkatessa Mausiaisen!

Annikki tytär Tapion

Vestä pilkat pitkin maita, Rasti vaarahin rakoja

Vikomata mennä viljan, Kamomata karjan käyvä

Kiviksi minun omani, Kannon päiksi kaunihini!

Emmäs kiellä kiertämästä, Karjoani kahtomasta,

Enkä käymästä epeä;

Kiellän kielin koskemasta, Hammasten hajottamasta, Lihan keski liikkumasta.

Annikki metän emäntä

Painas panta pihlajainen, Tahi tuominen rakenna, Tahi vaskesta valuos;

Kuin ei vaski vahva liene

Sitten rauvasta rakenna, Kytke sillä Ohon kuono, Jot' ei koske konnanana, Liikuta lipeänänä!

Oisi maata muuallahi, Tarhoa taempanahi, Juosta miehen joutilahan;

Kuin mä Ohtona olisin, Mesi-kämmennä kävisin, Emmä noissa noin olisi,

Aina akkohin jaloissa;

Käpy on kangas käyväksesi, Sormin sorkutellaksesi;

Otas juoni juostaksesi, Polku poimetellaksesi

Tuonne Manalan metälle.

Kuittola metän Kuningas

Veä ponto portahaksi, Silkki sillaksi sivalla, Poikki Pohjolan joesta, Jot' ei saisi juoni juosta, Ohto sormin sorkutella, Sipsutella sini sukka.

Niin sanoovi saaren vanhin, Puhas Taaria puhuuvi

Yheksältä yö-sialta, Sa-an taipaleen takoa:

Lulloseni, Lalloseni, Omenani, Ohtoseni

Siniä sullen syötetähän, Mesi nuori juotetahan Urohoisessa väessä, Miehisessä joukkiossa.

Kuin minä mies lähen metällen, Uros korvellen kohoan, Vuolen kuonat kullistani, Hopeistani homehet, Otan kolmet koiroani, Viisi villa-hänteäni, Seihtemän sepeliäni.

Niin on häntä koirallani

Kuin korehin korpi kuusi, Niin on silmä koirallani

Kuin on suurin suihti-rengas, Niin on hammas koirallani

Kuin on viikate virossa; Sinä koirani komehin, Otukseni oivallisin, Juoksuttele, jouvuttele

Aho-maita aukehia, Ensin kuusia kumarra, Havu-latvoja haloa, Hyväile hyötö-puita.

Juokse tuonne toisualle

Mielusahan Mehtolahan, Tarkkahan Tapiolahan!

Mielikki, metän Emäntä

Käyvös kättä antamahan, Oikeaa oijentamahan, Sormia sovittamahan!

Mikä mieli, mikä muutos

Mielusassa Mehtolassa, Tarkassa Tapiolassa!

Entinen metän Emäntä

Oli kaunis kahtannolta, Ihana imertimiltä,

Käet oli kulta-käärehissä,

Sormet kulta-sormuksissa;

Nykynen metän Emäntä

Ruma on varsin rungoltansa,

Käet on vihta- käärehissä,

Sormet vihta-sormuksissa, Pää vihta-pätinehissä.

Koreasti koirat haukku

Mieluhissa Mehtolassa, Leveästi lehmät ammo

Korven kuulussa koissa.

Louki (sic!) Pohjolan Emäntä

Pistäs villanen pivosi,

Käännä karva-kämmenesi; Oisi laajalta luvattu, Sukeukselta suvattu, Tapiolta taivotettu

Saalis suuri saahakseni, Mesi-kämmen käätäkseni.

Hilli Ukko, Halli-parta

Hiihatas hiasta miestä, Takin helmasta taluta, Veä verka-kauluksesta, Saata sillen saareksellen, Sillen kummullen kuleta, Josta saalis saatasihin, Erän toimi tuotasihin.

Kosk' oli saalis saatununna

Noin ne ennen vanhat virkko: En minä pahon pitänyt, Eikä toinen kumppanini:

Ite vierit vempeleeltä, Horjahit haon selältä

Puhki kultasen kupusi, Halki marjasen mahasi;

Päret jousi, puikko nuoli, Minä mies vähä väkinen, Uros heikko hengellinen.

Lähes nyt kulta kulkemahan, Sipomahan sini-sukka, Verka housu vieremähän

Urohoisehen väkehen, Miehisehen joukkiohon. Ellös vaimoja varuo, Katet-lakkia kamoja, Syltty-sukkia surejo, Peitto-päitä peljästyö.

Meill' on aitta ammon tehty

Hopeaisillen jaloillen, Kultasillen pahtahillen, Jonne viemme vierahamme, Kuletamme kultasemme.

Anna Päivälän miniä, Tuometar Tapion Neiti,

Kuin lienee vihattu vieras

Ovi kiinni ottoate;

Vaan kuin lienee suotu vieras

Ovi avoinna piteätä, Kulettaissa kultoamme,

Ohon astuissa sisähän.

Niin tuo Ohto pyörteleksen

Mesi kämmen käänteleksen

Niin kuin pyy pesäsän päällä

Hanhi hautomaksillahan.

Riien Synty.

Naata nuorin neitosia

Teki tiellen vuotehesan, Pahnasan pahalle maalle; Perin tuulehen makasi, Kalton säähän karkeahan.

Tuuli nosti turkin helmat, Ahava hamehen helmat,

Teki tuuli tiineheksi,

Ahavainen paksuksehen:

Tuosta tyyty, tuosta täyty

Tuosta paksuksi paneksen.

Kanto kohtua kovoa,

Vatan täyttä vaikeata;

Kanto kuuta kaksi, kolmet,

Kanto kuuta viisi, kuusi,

Jo kanto kaheksan kuuta, Kanto kuuta kymmenkunnan

Kanto kuuta kaksitoist;

Jo kuulla kahella toista

Tuotihin kavon kipua,

Immin tulta tuikattihin.

Juoksi polvesta merehen,

Vyö-lapasta laineheseen,

Sukka-rihmasta sulahan;

Heti huutaa heiahutti

Ainosillen ahvenillen,

Kaikillen veen kaloillen:

Tuuos kiiskinen kinasi,

Matikainen nuljaskasi;

Nyt tuloovi Immin tuska

Pakko neitosen paneksen.

Sivalti simasen siiven

Vyöltä Vanhan Väinämöisen,

Jolla voiti luun limiä,

Siveli sivuja myöten,

Perä vieriä veteli;

Syrjin syöstihin merehen,

Vesii-hiien hinkalohon,

Sala-kammun karsinahan, Lumme-korjuhun kotihin.

Alla raanusan yheksän, Alla viien villa vaipan

Teki poikoa yheksän, Tyttö-lapsen kymmenennen;

Sikiötähän sitoovi, Saamiahan solmiaavi

Kylpy-pelsimen perillä, Saunan lautaen laella, Nimitteli poikiahan, Lasketteli lapsiahan, Minkä kuuseksi kuvasi, Minkä mainihti maoksi.

Riisi on poika Ruivantehen, Ruivantehen, Räyväntehen,

Isätön, emätön lapsi, Suuton, silmitön sikiä.

Kuinkas taisi suuton syyä,

Kielitön nisän imeä, Hampaiton haukkaella, Näkemätön närvistellä?

Voi sinua piian pilkka, Piian pilkka, naisten nauru, Etkös nyt häiy häpeä, Paha poikkehen pakene

Ristittyä rikkomasta, Kastettua kalvamasta!

Miss' on Riisi ristittynä, Kaluaja kastettuna?

Tuoll' on Riisi ristittynä

Kaivolla kalevan pojan, Ketaroilla pienen kelkan.

Oliko vesi puhasta?

Ei ollut vesi puhasta;

Se vesi veren sekanen, Pesi huorat huntujahan,

Pahat vaimot paitojahan, Joilla Riisi ristittihin, Kaluaja kastettihin

Hamehissa haisevissa, Nukka-vieroissa nutuissa.

Kunne ma sinun manoan

Ristittyä rikkomasta,

Kastettua kautumasta?

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Suuhun juoksevan sutosen, Kesä-peuran kielen alle;

Hyvä on siellä ollaksesi, Armas aikaellaksesi, Lempi liehakellaksesi,

Siell' on voiset vuotehesi, Siasi sianlihaiset; Siellä itkeevi isäsi,

Valittaavl vanhempasi:

Kunne joutu poikuoni?

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Livu liitto-leivillesi, Mäne määrä- mämmillesi.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Ottuos sukusi sukset,

Heimokuntasi hevoset

Kotihisi mennäksesi,

Lemmon leppäset sivakat,

Hiien kalhut, rauta-kannat,

Pahan hengen paksun sauvan,

Joilla hiihat Hiien maita,

Lemmon maita leuhattelet.

Ehtiivi sinun emosi

Kotihisan Koiroahan.

Hyvin oot tehnyt, koskas tullut;

Teet paremmin kuin palajat.

Anna mennä männessähän

Venehellä vettä myöten,

Suksella mäkiä myöten,

Hevosella tietä myöten;

On lipua liiaksihin

Mäen alle mäntähissä.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Jalaksillen juoksevillen

Portimo kiven kolohon.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Korpin kiljuvan kitahan,

Suuhun vankuvan vareksen.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Suuhun Antero Vipusen,

Joka on viikon maassa maannut

Kauvon liekona levännyt;

Kulmill' on oravi-kuusi

Paju-pehko parran päällä.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Kirjo kirkon kynnyksehen,

Sata-lauvan lappeahan,

Tuhat malkosen maluhun;

Papit siellä pauhoavat

Miehet messua pitävät.

Ja jos et sitä totelle

Tuonne ma sinun manoan

Suurillen sota-keoillen,

Miesten tappu-tanterillen,

Joss' on verta vyöhön asti,

Siell' on luutonta lihoa,

Suonitonta pohkeata

Syyä miehen nälkähisen,

Hilpoa himertynehen,

Haukata halun alasen.

Pistoksen Synnyn Alku.

(Toisin.) [Katso II Osa, 1 sivu.]

Oli ennen neljä neittä.

Koko kolmet morsianta;

Nepä heiniä tekivät,

Kokoelit kortehia

Nenässä utusen niemen, Lässä saaren terhennisen.

Kuin niitit, ne haravoit, Heti ruoposit ruollen, Lapohollen laskettelit, Pistit pielihin välehin.

Tuli poika Pohjolasta, Nimeltä tulinen Tursas.

Ne Tursas tulehen tunki, Paiskasi panun väkehen.

Tuli tuhkia vähänen, Kypeniä kouran täysi.

Ne kypenet kylvettihin

Portin Pohjolan etehen, Kirjo-kannon kynnys alle.

Tähän kasvo kaunis tammi,

Virpi virhetön yleni;

Latva täytti taivahille, Lehvät ilmoillen levesit,

Estit päivän paistamasta, Esti kuun kumottamasta, Pietti pilvet juoksemasta, Hattarat harittamasta.

Neiet neuvoa pitävät

Kuinkas kuutta lietänehen, Otavatta oltanehen, Päivätä elättänehen.

Etittihin tuota miestä, Haettihin miestä mointa

Väestä, pitäjähästä, Kuuen kirkon kuulusalta, Joka nyt taisi tammen kaata, Puun sorean sorrutella, Puun vihannan vieretellä.

Mies musta merestä nousi, Aallollen ylenteleksen.

Koko korttelin pitunen, Vähän vaaksan korkeunen, Maljan alle maata' mahtu, Seulan alle seisomahan; Astua lykytteleevi,

Levehillä liehumilla;

Syltä oli housu-lahkehesta, Puolta toista polven päältä, Kahta kartehen perästä j.n.e.

Vaapsahaisen Sanat.

Ampiainen, angervainen

Synnyttattari synnyttää, Kasvattattari kasvattaa, Pistä piikkis, taita nuoles, Käännä kärki käppyrään, Mieles mesi-leipää!

Hiiren Sanat.

(Heiniä suovaan pannessa.)

Hiukka hiiren hampaaseen, Karsi kaunajan kitahan!

Jos karvan nielet, Toisen puret, Kolmannelle kohta kuolet.

Pakkasen Sanat.

(Lisäys. Katso II Osa, 26 sivu.)

Panen Pakkasen rekehen, Pakkasen keulan pajulle, Pakkasen perä-pajulle, Kesän keskelle rekeä

Ite keskelle keseä.

Tulen Sanat.

Taian minä tulen lumoja, Valtiasta vaivutella:

Neito laskien Lapista

Vaskisella Venehellä, Jäinen kokka, jäinen keula,

Jäinen jälkkäres sisässä, Jäinen kattila tulella, Jäinen sanka kattilassa.

Jos se on tulessa palanut, Hauvo metinen sauna

Metisellä kiukahalla!

Mettiäinen mettä tuo

Meren yheksän takoa, Meri puolen kymmenettä, Haavolle paranteheksi, Kipiöille voiteheksi.

Lapsen Saajan Sanat.

Neity Maria emonen, Rakas äiti armollinen,

Käys tänne käpein kengin, Helmon hienon helmotellen,

Sukin valkein vaella,

Sukin mustin muikuttele!

Tule saunahan salahan, Piilten pirtti-huoneheseen,

Tule! tänne tarvitahan

Kivut kiinni ottamahan, Vaivat vaikahuttamahan!

Päästä piika pintehistä, Vaimo vattan vääntehistä!

Ota kiiskiltä kinaa, Matehelta nuljaskata,

Hauvo nuilla hautehilla, Voia nuilla voitehilla, Joilla Jesus voieltihin, Kastettihin kaikkivalta,

Päästä päivistä pahoista, Sitehistä sitkehistä, Kipu-vöistä kiintehistä!

Imehiä. Joulu toi joukossa tuleepi, Tanssissa Tapanin päivä.

Tanssas toi taitava Tapani Puoli yöstä puoli yöhön.

Tapanill' on talli renki, Vei toi hevoista vedelle

Läpi säärtä lähtehelle, Kaivolle kadikkaselle; Lähde läikky, hepo kuorsu. "Mitäs kuorsut koiran ruoka, Hirnut Hiisien hevoinen?"

Iskin mä silmäni itähän, Näjin tähden taivahalla, Pilkun pilvien raossa.

Meninpä Ruotuksen tupahan.

Ruotus haastoi rualtansa, Tiivas tiiskinsä nojalta:

"Siis mä tuon todeksi uskon, "Jos toi härkä mylvineepi, "Kuin on luina laattialla, "Liha syöty, luut lusittu, "Kesi kenkinä pidetty."

Rupeispa härkä mylvimähän, Luillansa luhisemahan, Kynsin maata kaappimahan.

"Siis mä tuon todeksi uskon, Jos toi kukko laulaneepi,

Kuin on paistina vaissa, Kuin on voilla voideltuna, Jäsenille järköitetty,

Höyhenille höykytetty."

Rupeis toi kukko laulamahan, Kukko kuudelta sanalta, Kananpoika kahdeksalta.

"Siis mä tuon todeksi uskon

Jos toi veitsen pää vesoisi, Kuin on lyöty laattiahan."

Rupespa veitsen pää vesohon, Vesois kuudelta vesalta, Kulta lehti kunkin päässä,

Jo ma nyt luovun Ruotuksesta, Otan uskon Jesuksesta.

Tämä paljo vaillinainen Runo, jonka Savon maalta on minulle

toimittanut Hovi-Rätin Assessori Herra C.H. Asp, arvellaan olevan niiltä ajoilta, koska Christin usko Ruotsalaisilta Papeilta täällä ensin levitettiin ja ne imehitten saarnajat luultiin itte imehiä tekevän, että myös pakanalliset loihtu-miehet toisia imehiä näitä vastaan yrittelit.

Jauho Runo

Jos mun tuttuni tulisi,

Ennen nähtyni näkyisi!

Sille suuta suikkajaisin;

Olis suu suen veressä;

Sillen kättä käppäjäisin, Jospa kärme kämmen-päässä.

Olisko tuuli mielellissä

Ahavainen kielellissä:

Sanan toisi, sanan veisi, Sanan liian liikuttaisi, Kahden rakkaan välillä.

Ennenpä heitän herkku-ruat, Paistit pappilan unohtan

Ennenkuin heitä herttaiseni, Kesän keskyteltyäni, Talven taivuteltuani.

Tarttuman Loihtu.

Tuonne ma sinun manoan, Tuonne kuollehen kuoppahan, Iki männehen ihoon, Joss' on muutkin murha-miehet, Ikuiset pahan tekiät.

Jos on kalman kammiosta, Männös kalman kammiohon;

Jos vesi-Hiien hinkalosta

Männös vesi-Hiien hinkalohon,

Syömästä, kaloamasta, Ristittyä rikkomasta, Kastettua koatamasta,

Tehtyä tellomasta. Siellä on syyä syöläisen Haukata halun alaisen.

Nykyisempiä Runoja.

Runo viinan ryyppäämisestä.

Kuules, viina! kuin ma laulan, Kuules, Putelli! puheeni.

En minä moiti mahtiasi,

Enkä voimias vähennä.

Viina on Jumalan vilja,

Ja on kyllä kelpo ruoka,

Siivo syöjille suloinen,

Jotka ryypyn ryyppäjävät,

Harvoin kaksi kallistavat,

Kolmest' ei koskaan huoli.

Kuinka kultainen kulekset

Herran lahja hielukselet

Sydämmess' syömättömässä,

Eine-ryyppynä esitte,

Annat aamusta varahin

Ruoka-lystin ruumihille.

Vaan ne kuin ovat ystävänä

Suunsa kanssa suuttumata,

Siihen hankkivat halulla

Kaikin ajoin kantamista,

Niille on ikänsä ollut

Ruoka varsin vaarallinen.

Eikä se sukua katso,

Eikä säätyä eroita.

Teki se ennen tengan reijän

Talonpojankin povelle;

Potkaisi se Porvarinkin

Kauppa-kaaren kallellensa;

Saa se Saarnamiehistäkin

Vaarsin valmiista Papeista

Tekee Teiniks' toisen kerran;

Lukkareilla laulattaapi

Väärän virrenkin välistä;

Toisinaan se toimittaapi

Tuomarinkin tuhnioksi;

Lautamiehet laitteleepi

Juttu-miesten mieltä myöden,

Kuin käyvät käräjä-miesten

Arkun kantta aukomassa:

Sitte torkkuvat tuvassa,

Virka vaihtuupi uneksi.

Minkäs tekee mittareille?

Minkä muille muutamille

Virkamiehille vähille?

Nimismiehet niinkuin muutkin

Paneepi pahalle tielle,

Viskaapi virattomaksi,

Toimittaapi Tolppariksi.

Siinä se siivon tekeepi,

Kuin se vaimoja vetääpi

Penkin päähän pitkäksensä,

Lakki päässä pyörähtääpi, Pois nokka nenän kohalta:

On outo näkevän nähdä

Paha pitävän pitää, Joita varjele Jumala

Näkemästä, kuulemasta.

(Tekiä: Matti Korhoin, Rautalammen Pitäjästä.)

Kirpusta.

Elias Tuoriniemelta.

Saattasinkoma sanoa

Kirjotella kirpustakin?

Kirottu on kirppu rukka

Ijankaiken ihmisiltä;

Siitä on kirppu kirottu

Moitittava musta lintu,

Kuin on hyvä hyppimähän.

Vielä potkiipi povessa,

Tohtii tulla turkkihinkin,

Valta-miesten vaatteisiinkin

Hyvän huovin housuhinkin

Suuren herran sukkahankin

Papin paijanki sisälle.

Käypi se kirppu kirkossakin

Kirkko-miehen kintahassa.

Kaikki sitä kanteleepi

Kaikki kurjat kuljettaapi

Yli soijen, yli maijen,

Syän maijen synkiöinkin.

Varsin tuttu vaimoillenkin

Miesten luona mielellänsä;

Syöpi lasta laattialla

Käypi lasten kätkyesä

Vanhojakin valvottaapi, Ei anna nuorten nukkua

Eikä maata matka-miehen.

Alla se aina asuupi

Vuosi kauet vuotehilla,