OpticalFiberSensors fortheNext Generationof RehabilitationRobotics

ArnaldoLeal-Junior

MechanicalEngineeringDepartment

FederalUniversityofEspiritoSanto Vitória,Brazil

AnselmoFrizera-Neto

ElectricalEngineeringDepartment

FederalUniversityofEspiritoSanto Vitória,Brazil

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright©2022ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans, electronicormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageand retrievalsystem,withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseek permission,furtherinformationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangements withorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency, canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchand experiencebroadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,or medicaltreatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgein evaluatingandusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.In usingsuchinformationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyof others,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors, assumeanyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproducts liability,negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products, instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-323-85952-3

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: MaraConner

AcquisitionsEditor: SonniniR.Yura

EditorialProjectManager: IsabellaC.Silva

ProductionProjectManager: SojanP.Pazhayattil

Designer: VictoriaPearson

TypesetbyVTeX

2.1Softrobots:definitionsand(bio)medicalapplications

2.2Softrobotsforrehabilitationandfunctionalcompensation

2.3Human-in-the-loopdesignofsoftstructuresandhealthcare systems

2.3.1Human-in-the-loopsystems34

2.3.2Human-in-the-loopapplicationsandcurrenttrends37

2.3.3Human-in-the-loopdesigninsoftwearablerobots39

2.4Currenttrendsandfutureapproachesinwearablesoftrobots

3.3Gaitanalysissystems:fixedsystemsandwearablesensors

4.1Historicalperspective

4.2Lightpropagationinopticalwaveguides

4.3Opticalfiberpropertiesandtypes

4.4Passiveandactivecomponentsinopticalfibersystems

4.4.1Lightsources77

4.4.2Photodetectors77

4.4.3Opticalcouplers79

4.4.4Opticalcirculators80

4.4.5Spectrometersandopticalspectrumanalyzers81

4.5Opticalfiberfabricationandconnectionmethods 83

4.5.1Fabricationmethods84

4.5.2Opticalfiberconnectorizationapproaches87 References 89

5.Opticalfibermaterials

5.1Opticallytransparentmaterials

5.2Viscoelasticityoverview

5.3Dynamicmechanicalanalysisinpolymeropticalfibers 101

5.3.1DMAonPMMAsolidcorePOF103

5.3.2DynamiccharacterizationofCYTOPfibers107

5.4Influenceofopticalfibertreatmentsonpolymerproperties 111 References 115

6.Opticalfibersensingtechnologies

6.1Intensityvariationsensors 119

6.1.1Macrobendingsensors120

6.1.2Lightcoupling-basedsensors125

6.1.3Multiplexedintensityvariationsensors127

6.2Interferometers 129

6.3Gratings-basedsensors 133

6.4Compensationtechniquesandcross-sensitivitymitigationin opticalfibersensors

7.Wearablerobotsinstrumentation

7.1Opticalfibersensorsonexoskeleton’sinstrumentation

7.2Exoskeleton’sangleassessmentapplicationswithintensity variationsensors 152

7.2.1Casestudy:activelowerlimborthosisforrehabilitation (ALLOR)156

7.2.2Casestudy:modularexoskeleton157

7.3Human-robotinteractionforcesassessmentwithFiberBragg Gratings 160

7.4Interactionforcesandmicroclimateassessmentwithintensity variationsensors 166

References 172

8.Smartstructuresandtextilesforgaitanalysis

8.1Opticalfibersensorsforkinematicparametersassessment 175

8.1.1Intensityvariation-basedsensorsforjointangle assessment175

8.1.2FiberBragggratingssensorswithtunablefilter interrogationforjointangleassessment178

8.2Instrumentedinsoleforplantarpressuredistributionand groundreactionforcesevaluation 183

8.2.1FiberBragggratinginsoles183

8.2.2Multiplexedintensityvariation-basedsensorsforsmart insoles188

8.3Spatiotemporalparametersestimationusingintegratedoptical fibersensors 198 References 199

9.Softroboticsandcompliantactuatorsinstrumentation

9.1Serieselasticactuatorsinstrumentation 201

9.1.1Torquemeasurementwithintensityvariationsensors202

9.1.2Torquemeasurementwithintensityvariationsensors206

9.2Tendon-drivenactuatorsinstrumentation 212

9.2.1Artificialtendoninstrumentationwithhighlyflexible opticalfibers213 References 217

PartIV Casestudiesandadditionalapplications

10.Wearablemultifunctionalsmarttextiles

10.1Opticalfiberembedded-textilesforphysiologicalparameters monitoring 223

10.1.1Breathandheartratesmonitoring224

10.1.2Bodytemperatureassessment232

10.2Smarttextileformultiparametersensingandactivities monitoring 234

10.3Opticalfiber-embeddedsmartclothingformechanical perturbationandphysicalinteractiondetection 239

11.Smartwalker’sinstrumentationanddevelopmentwith compliantopticalfibersensors

11.1Smartwalkers’technologyoverview

11.2Smartwalkerembeddedsensorsforphysiologicalparameters assessment 247

11.2.1Systemdescription247

11.2.2Preliminaryvalidation250

11.2.3Experimentalvalidation252

11.3Multiparameterquasidistributedsensinginasmartwalker structure 252

11.3.1Experimentalvalidation252

11.3.2Experimentalvalidation256

12.Opticalfibersensorsapplicationsforhumanhealth

12.1Roboticsurgery

12.2.1Introductiontobiosensing269

12.2.2Backgroundonopticalfiberbiosensingworking principles271

12.2.3Biofunctionalizationstrategiesforfiberimmunosensors276

12.2.4Immunosensingapplicationsinmedicalbiomarkers detection279

Preface

Theadvancesinmedicineandphysicaltherapyinconjunctionwithnewdevelopmentsofmechatronicdeviceswithahigherlevelofcontrollabilityenabled thedevelopmentofassistiveroboticdevices,whichareexploredbymanyresearchgroupsaroundtheworld.Concurrently,thereisthedevelopmentand widespreadofopticalfibertechnology,whichisincreasinglyusedassensors devices.Theopticalfibersensorscharacteristicsarewellalignedwiththerequirementsofroboticinstrumentation,especiallytheoneswithelectricmotors, commonlyusedinwearablerobots:Opticalfibersensorsareimmunetoelectromagneticperturbationsofferingprecisemeasurementsinnoiseenvironments. Inaddition,theflexibilityofopticalfibersisalsoalignedwiththenewtrends insoftandflexibleroboticsystems,wherethesensorscanbeembeddedinthe robot’sstructureortheycanbeplacedonwearabledevicesforpatientmonitoring.Yearsago,alloftheseadvancesresultedinanewresearchdirection,where theopticalfibersensorswereusedontherobots’instrumentationtoextendtheir controlcapabilitiesbymeasuringparametersthatwerenotcommonlymeasured withconventionalelectromechanicalsensors.

Theresultsofyearsofresearchinroboticsandopticalfibersensorsina jointeffortoftheGraduatePrograminElectricalEngineeringandMechanical EngineeringDepartmentoftheFederalUniversityofEspiritoSanto(UFES)are summarizedinthisbook.Theaimofthisbookistoprovideacomprehensive understandingonthisnewresearchtopicanditsunderlyingtheoryandprinciples.Thisbookwasproposedandconceivedundertheassumptionthatthe nextgenerationofwearablerobotsanddevicesnotonlywillincludethesoft structureandcompliantactuators,butalsothenewopticalfibersensorsembeddedintherobots’structureandactuationunits.Wedividedthebookintofour parts.Inthefirstpartofthisbook,thedevelopmentsinwearablerobotsand assistivedevicesaswellashuman-in-the-loopdesignandtherecentdevelopmentsonsoftroboticsarediscussed.Inthesecondpart,thefocusisshiftedto opticalfibersincludingthepresentationofanoverview,themaincomponents, andcharacteristicsofanopticalfiber-baseddetectionsystemandthematerials commonlyusedonthedevelopmentofopticalsensors.Moreover,opticalfiber sensorsapproachesarepresented.Thethirdpartpresentstheopticalfiber-based instrumentationsystemsinwearablerobotsandassistivedevices,resultingin

x Preface

thecombinationoftheknowledgeacquiredinthefirstandsecondpartsofthe book.Thediscussedsystemsincludewearablerobots,smartstructuresinwhich thesensorsareembeddedinrigidand/orsoftstructuresoftherobots,compliant actuatorsandsmartwearabletextilesforpatientsmonitoring.Inthelastpart ofthebook,differentcasestudiesandadditionalapplicationarepresentedto provideabroaderviewofthemanypossibilitiesofopticalfibersensorsinassistivedevices,whichincludethedevelopmentsinsmartwalker’sinstrumentation, roboticsurgerywithmanipulators,physiologicalparametersmonitoringusing multifunctionaltextiles,andeveninbiosensorsforhealthassessment.

Thisbookcouldnotbewrittenwithoutthehardworkofthecontributors, L.Avellar,V.Biazi,W.Coimbra,andL.Vargas-Valencia,allofthemfrom UFES,contributedforsomechaptersthroughoutthebook.C.Marquesfrom UniversityofAveiro,alongtimecontributorinourresearchgrouphelpedus onthebiosensorsapplicationsusingopticalfibers.Theadvancesandmethods discussedinthisbookweredevelopedintheframeworkofdifferentresearch projectsfocusedonrehabilitationoropticalfibersensingtechnologiesasfollows:

–Activetransparentorthosisforrehabilitationandmovementassistance (CAPES88887.095626/2015-01);

–ResearchCenteronPhotonicsandAdvancedSensing(FAPES84336650);

–Opticalfibersensorsnetworkforpatientsremotemonitoring(FAPES 320/2020);

–Opticalfibersensorsinoil-waterinterfacemeasurementinproductiontanks (Petrobras2017/00702-6).

Wewouldalsoliketothankallthesupportfromourcolleaguesinwritingthis book.

ArnaldoLeal-Junior AnselmoFrizera-Neto FederalUniversityofEspiritoSanto,Vitória,Brazil

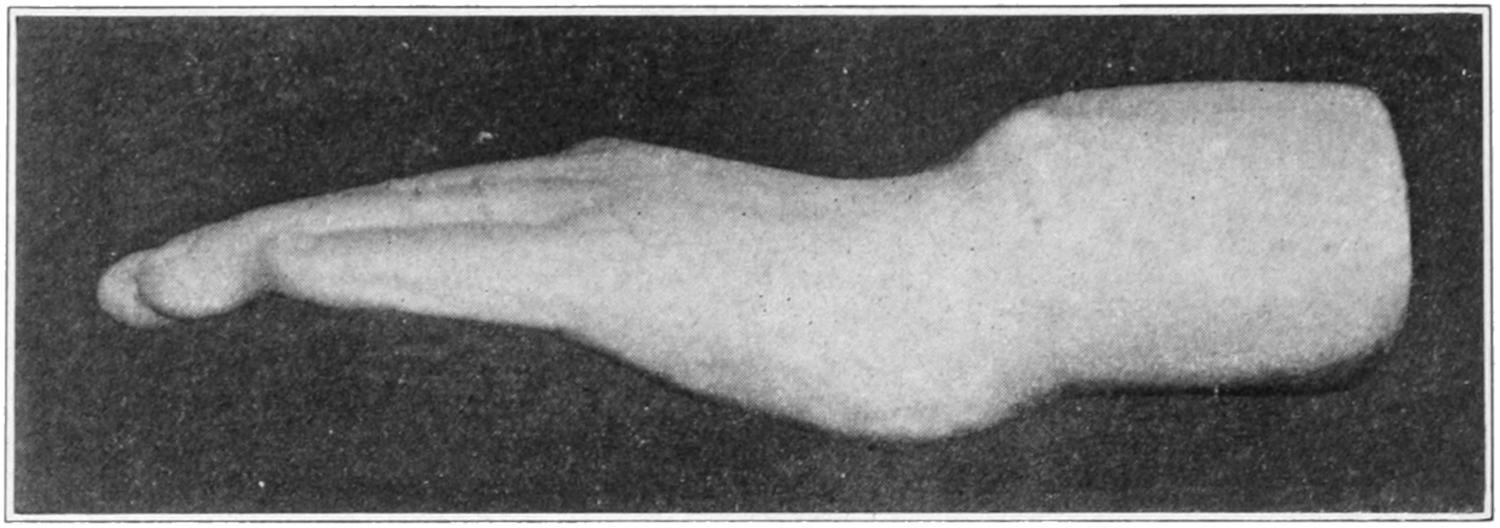

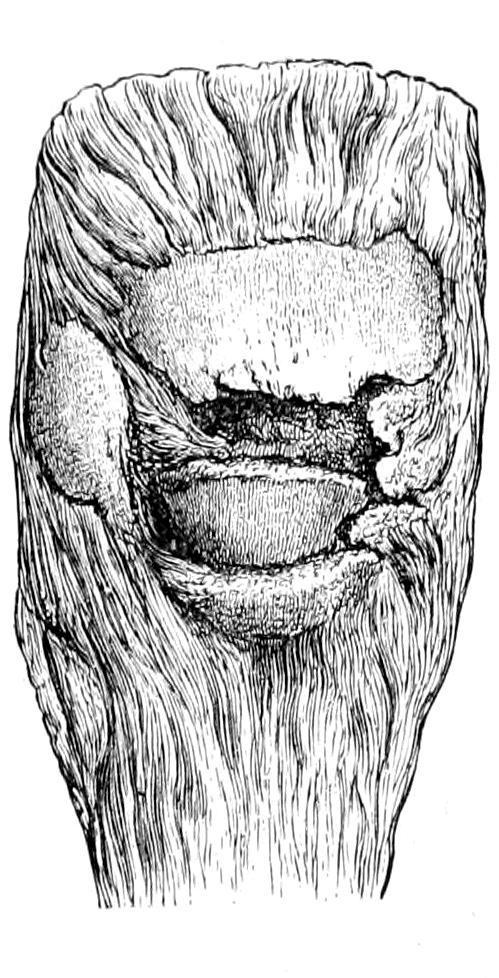

Skiagram of Fracture of the Proximal Phalanx of the Ring Finger. (Wharton.)

FRACTURES OF THE WRIST AND HAND.

Fractures of the carpal bones seldom occur, except when the parts have been crushed. The scaphoid is, however, broken much more often, and doubtless many cases of so-called severe sprain include this injury. The use of the x-rays has done more to teach the relative frequency of carpal fractures than was ever previously appreciated. The scaphoid ossifies by two centres, which do not appear until the eighth year. When the bone has been thus cracked the usual signs of sprain are present, which subside and leave a tender wrist and hand whose fingers can be normally moved, but whose wrist movements are reduced one-half, while attempts at motion beyond these limits produce great muscle spasm and pain. Codman and Chase[40] have shown that the sheaths of the radial extensor tendons are in close relation to the periosteum of the bone at this point, as well as to that of the radius, so that by injury here blood may escape into the sheath without appearing at other parts; the result being a tense, fluctuating, triangular swelling over the radial half of the wrist, the blood being effused so deeply as not to discolor, or at least not at first. They regard the presence of such an engorged bursa as diagnostic of fracture either of the radius or the scaphoid.

[40] Annals of Surgery, March, 1905.

While carpal fractures call ordinarily for treatment by absolute rest, Codman and Chase have advised removal of any loose fragment, especially of the scaphoid, by incision along the back of the wrist just to the inner side of the long radial extensor. The annular ligament is to be divided between it and the long extensors of the fingers, and without opening tendon sheaths; inasmuch as this ligament does not retract when divided its borders must be held apart. In this way the joint may be completely exposed over the

proximal half of the scaphoid. The line of fracture being made out, a blunt hook is introduced into the fissure and the fragment elevated, loosened by a tenotome, and removed, its removal seeming nowise to interfere with the function of the whole bone or the usefulness of the wrist.

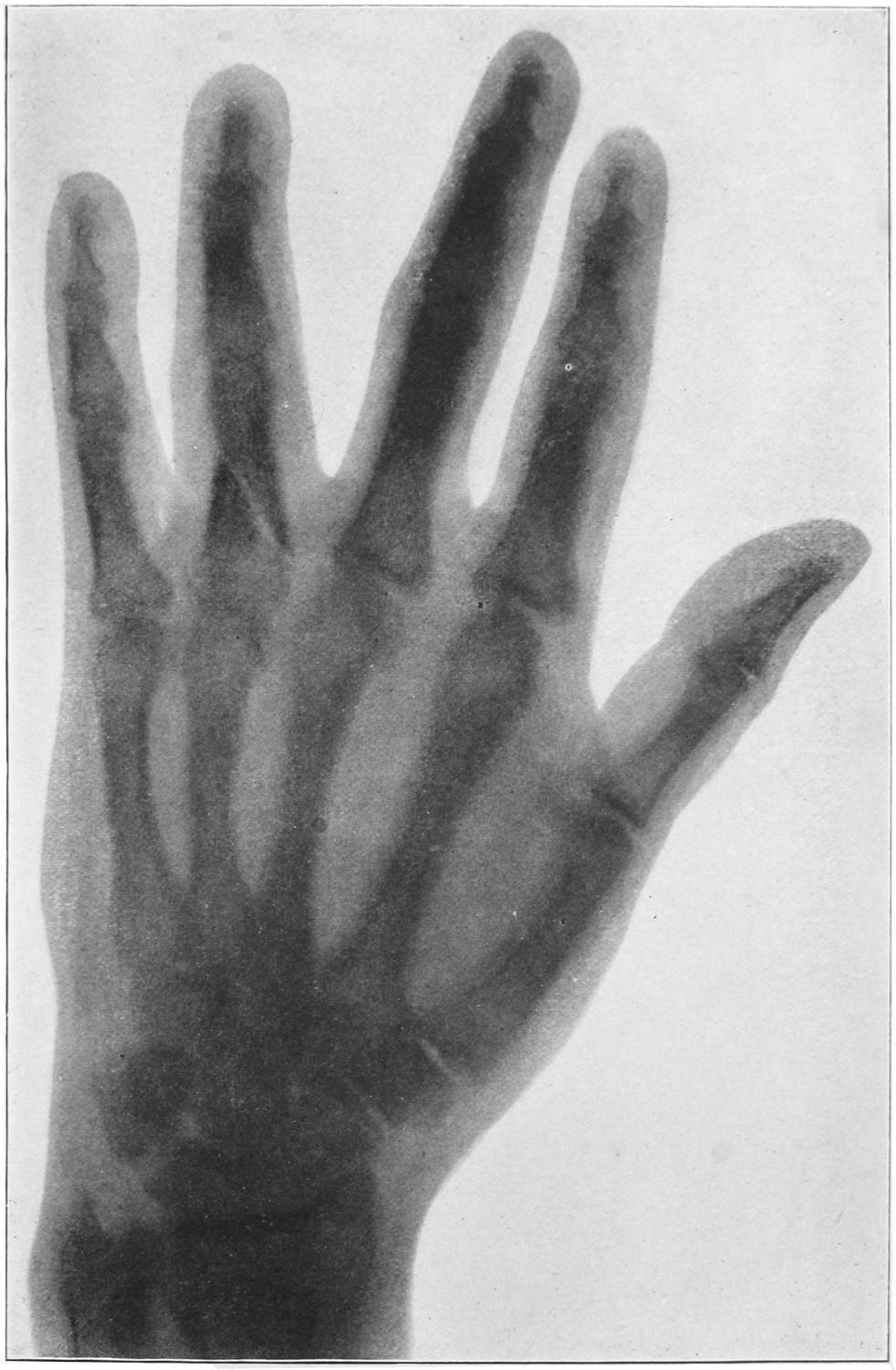

The metacarpalbones are frequently broken, usually as the result of violence, the distal portions suffering more than the proximal. The diagnosis is best made with the fingers closed, when any lack of symmetry in the row of knuckles may be seen or any protrusion of a fragment noted. Here the x-rays are useful. Such injury should be treated by placing the hand upon a palmar splint extending well up the forearm and maintaining rest by suitable pressure, with or without traction upon the finger of the bone involved. For this purpose adhesive plaster may be passed up and down the finger and attached to an elastic band which is fixed to the end of the splint.

The same is true of fractures of the phalanges, which are often made compound by the injury. Here the danger is not so much to the bone as to the tendon sheaths or thecæ, along which infection may easily spread. Widespread and prolonged suppuration might disable a hand thus injured unless properly and promptly dressed. Ordinarily adjoining fingers can be utilized for splints, and if the outstretched hand be fastened upon a palmar splint and the injured finger kept in position by its neighbors a good result can generally be obtained. Occasionally distinct splints for one or more fingers are required, and occasionally also the suggestion made above with regard to traction may need to be enforced.

FRACTURES OF THE PELVIS.

Fracture of the pelvis may be serious not only in and of itself but because of frequently accompanying injuries to the various pelvic viscera. Save in the possible separations that may occur during parturition it is always the result of direct violence. Such injuries are usually divided into fractures of the pelvic girdle and those of the more exposed prominences, such as the iliac crest, the ischiac tuberosity, the coccyx, etc. Lines of fracture may run at any point,

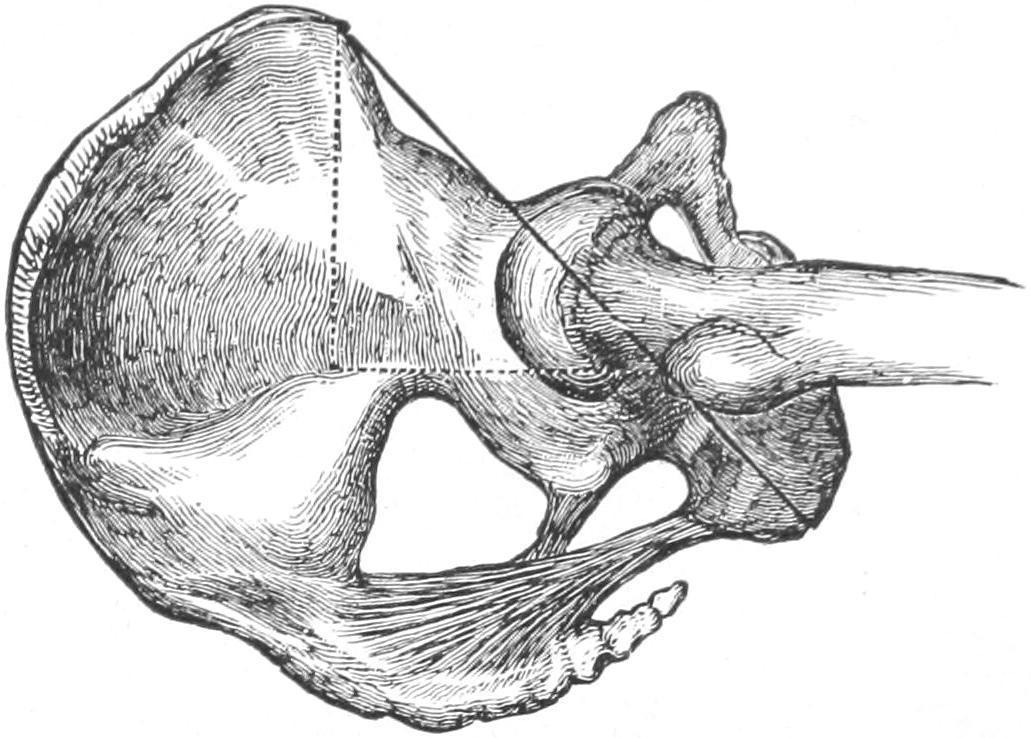

although it is at the synchondrosis that the pelvis is usually broken loose from the sacrum. As in the skull and the lower jaw double fractures or even comminutions may occur. The same considerations concerning the transmission of serious violence may account for some of the vagaries seen in these cases. The sacrum is usually broken as the result of great violence. The pelvic girdle is perhaps weakest opposite the joints and in the neighborhood of the pubis. Here there may be a separation of the symphysis, but the break usually occurs a little to one side of the middle line. In rare instances the head of the femur has been forced through the acetabulum (Fig. 308).

In a general way fractures of the pelvic girdle can be recognized not merely by local evidences of injury and shock, but by the resulting more or less complete loss of function; patients will be disabled in proportion to the violence and extent of the injury. The more unilateral the symptoms the easier it is to localize the site of the injury. Mobility can often be detected upon examination, sometimes crepitus. This is essentially true of fractures of the pubis. Occasionally combined manipulation, with a finger in the rectum or vagina, will permit more accurate localization of the injury. When the crest of the pelvis is fractured, or any of the parts to which the abdominal muscles are inserted, then the patient will be still further disabled in movements of the lower part of the body, while by palpation the fracture is sometimes easily determined.

Not the least serious features of these injuries are those which pertain to the viscera. These include not only the ordinary results of abdominal contusions which may produce all sorts of harm, for example, ruptures of the kidneys, spleen, or liver, but also more localized lesions, such as ruptures of the rectum, bladder, or urethra, or even the pelvic connective tissue. If the urinary passages be torn there is always opportunity for urinary infiltration and infection. The same is true of the rectum so far as possibility of infection is concerned. Therefore one of the earliest maneuvers in dealing with such a case should be the passage of a catheter, to determine if the urine be bloody or the urethra obstructed. In such a case, in the male at least, it will usually be wise to make a perineal section and

to open widely and then drain the bladder. In not a few of these instances the laceration takes place internally, and a pelvic crushing injury, which is followed by collapse and abdominal rigidity, without satisfactory explanation as above, should be promptly explored by abdominal section, the danger of doing it being considerably less than the risk of leaving it undone.

Some of these fractures are conspicuously compound, and the treatment for the external wound will permit of more careful exploration of the bone injury, as well perhaps as the insertion of wire sutures or other means of fixation.

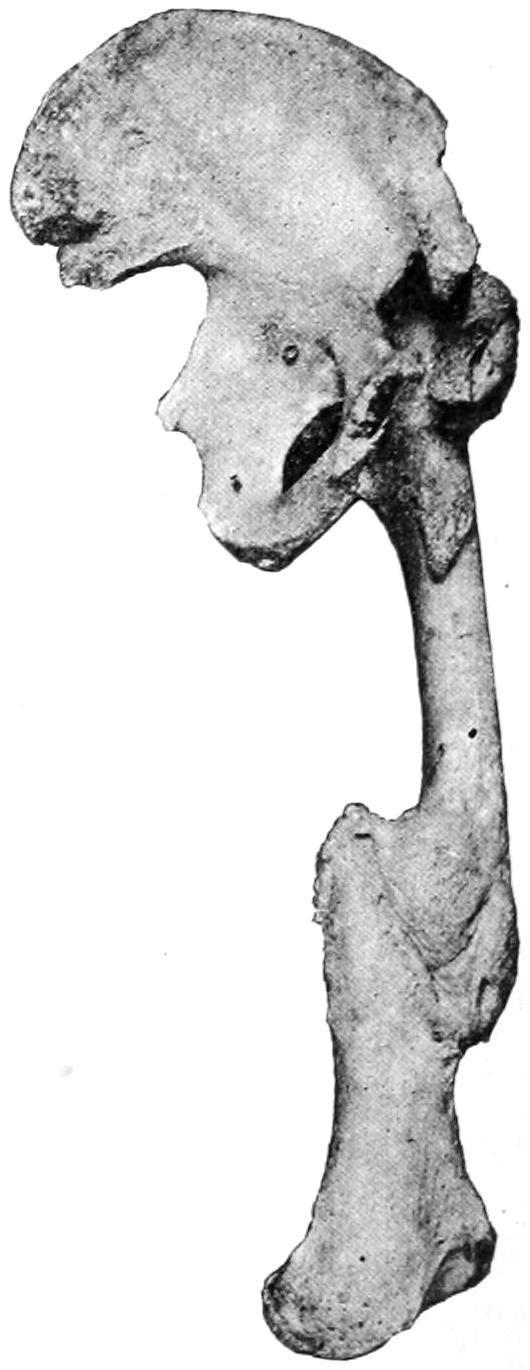

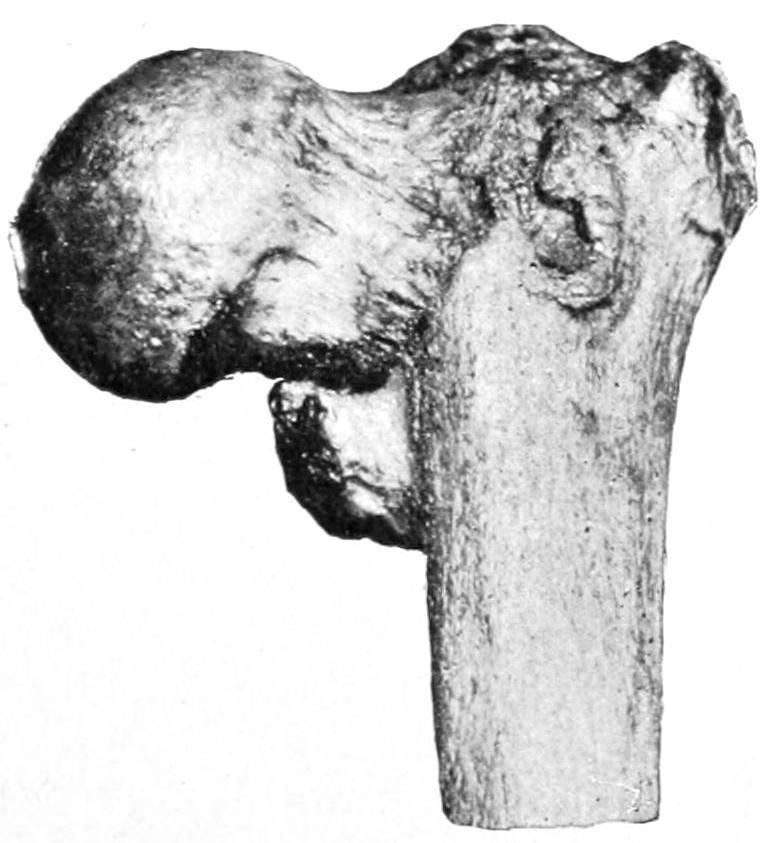

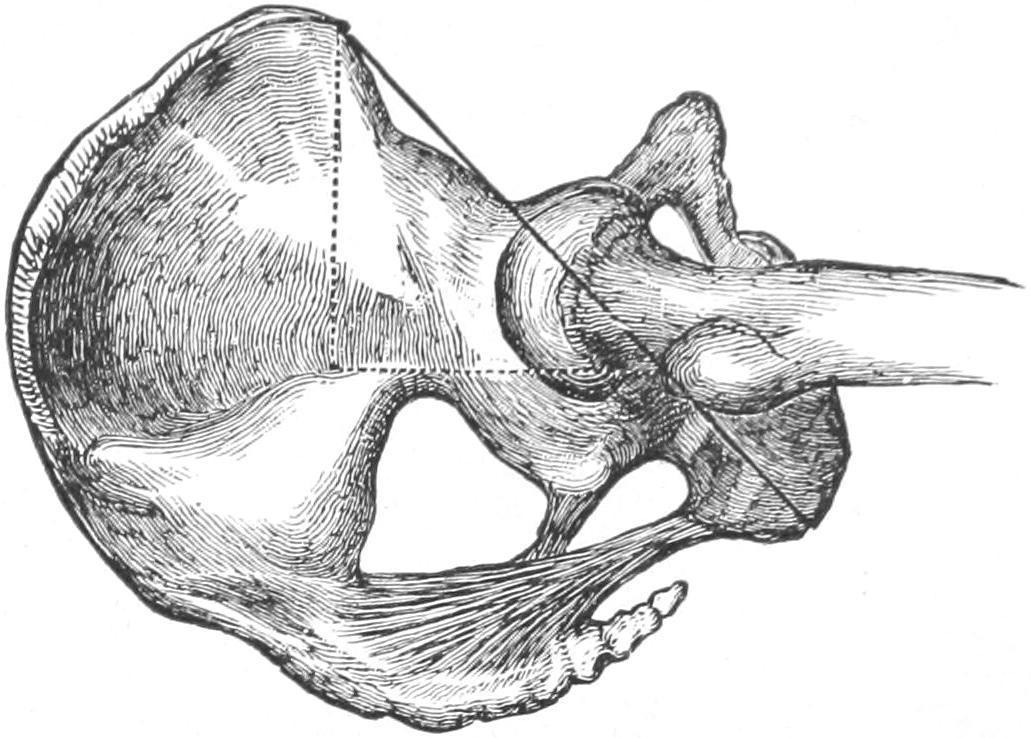

Fracture of pelvis. (Mudd.)

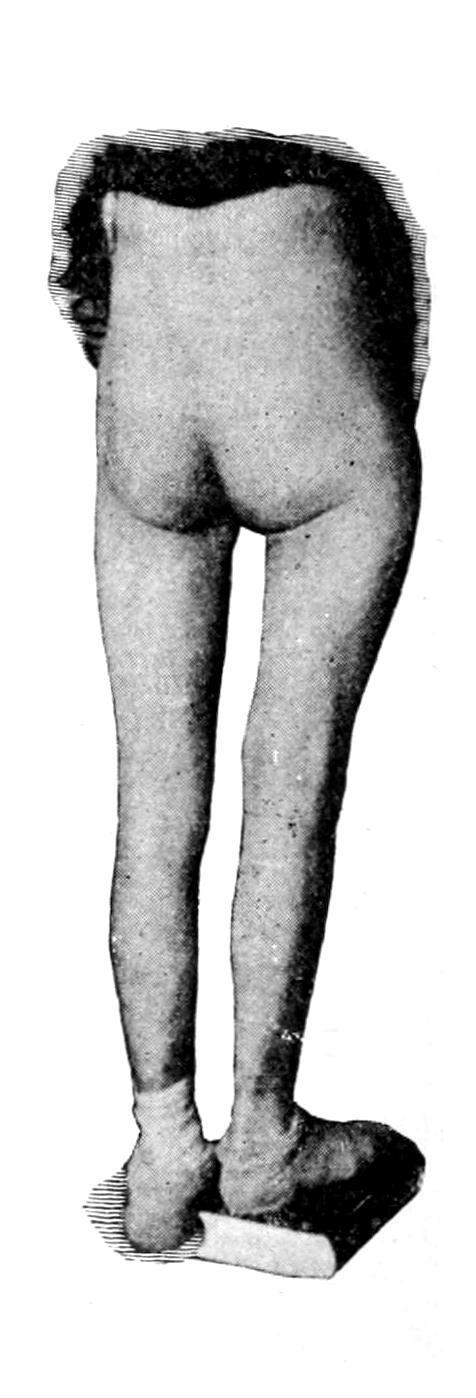

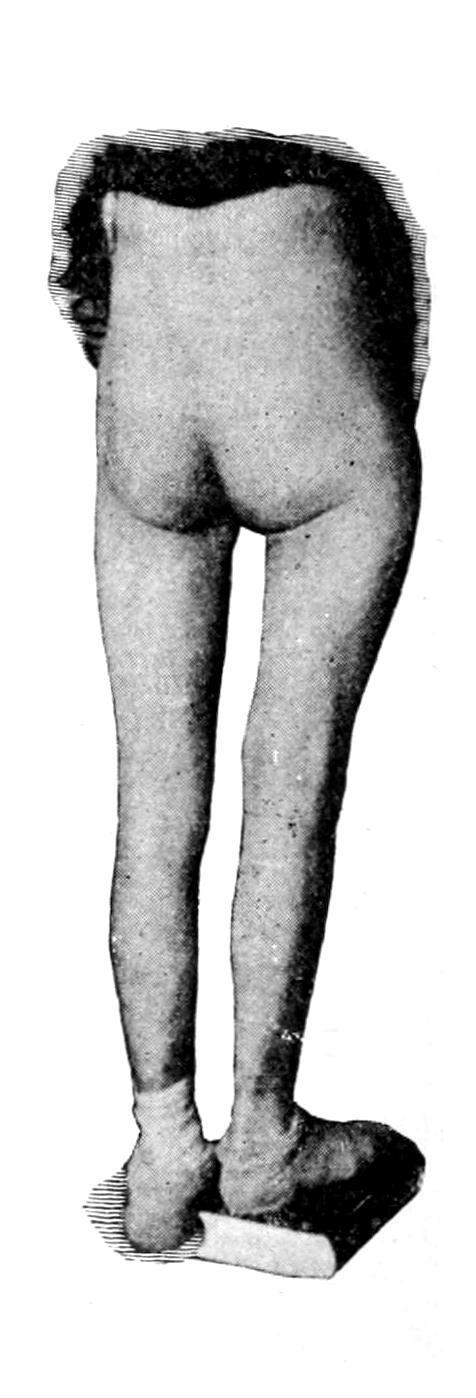

Fig. 309 illustrates a serious complication that ensued in one case after multiple fractures of the pelvis and hip, with synostosis at the hip, as well as extensive deformity following fracture of the shaft of the femur.

Treatment.

—Treatment of pelvic fractures should comprise, first, absolute rest. This means not merely confinement in bed, with traction applied to one or both limbs, but probably fixation of the pelvis and perhaps the thighs, either in a compressing bandage or in a plaster-of-Paris double spica, the pelvic jacket running as high as may be necessary upon the trunk of the body. Cases which seem to permit of operation and suturing are entitled to it, but they will constitute but a small proportion of the total. While patients are so rigidly confined provision should be made for free elimination, and possibly conveniences provided for receiving the evacuations without possibility of infection. Recovery is in many instances complete; occasionally it occurs with considerable displacement. If the viscera escape injury much may

Great deformity after multiple fracture of femur, with synostosis. (From the Buffalo Museum.) be expected in the way of repair of the bones under suitable treatment.

The margin of the acetabulum is occasionally chipped off, sometimes by itself, sometimes as a complication of dislocation of the hip. The posterior margin of the brim is the part which usually suffers. Diagnosis should be made by the ease with which such a dislocation recurs after manual reduction. Sufficient traction to keep the limb from displacing the fragment, and snug bandaging with pressure, especially around the injured hip and above the trochanter, is indicated in such cases.

The coccyx and even the lower portion of the sacrum are occasionally broken loose, either by external violence or during parturition. Here the fragment is drawn forward by the levator ani, displacement is marked, and pain and soreness are great. Should there be doubt as to the nature of the injury, combined manipulation, with a finger in the rectum, will make diagnosis positive. Fibrous union is about all that can be expected in either of these cases. The fragment may be justifiably removed at any time.

FRACTURES OF THE THIGH.

Fractures at the upper end of the thigh are more common than those at the lower. At the upper end there may be fractures of the head, of the neck, those which pass between the trochanters, and epiphyseal separations. All of these are rare except those of the neck.

Fractures of the neckofthefemur occur most commonly in those who have passed the fiftieth year of life. They occur, however, during the middle period and even in children, and, as Whitman has shown, are by no means so rare in the young as was until recently supposed.

The shape and structure of this portion of the bone, and the peculiar changes which occur with advancing years, constitute the explanation for the frequency of this injury in late life. As the jaw begins to change in shape, and the teeth to drop out, there occur

also unseen changes within the cancellous structure of the head and neck of the femur by which the strength of the latter is materially reduced. It is still further weakened by the change in shape which the bone also undergoes as it loses its obtuse angle and becomes set more at a right angle with the shaft. The reduced ability to resist strain produced by these changes is remarkable, and accounts for the ease with which fractures occur, even from so apparently trivial an accident as tripping on the floor. With all the violence directly transmitted there is usually present an element of twist or torsion by which fracture is still further favored.

As between so-called intracapsular and extracapsular fractures surgeons have made distinctions to which unnecessary importance has been attached. Anteriorly the capsule is attached to the intertrochanteric line, while posteriorly it does not extend nearly so far outward; it can thus be seen that many fractures are partly intracapsular and partly extracapsular. These lines vary in different individuals, especially that of the posterior insertion; it is not usually possible to make minute distinctions of this kind. The principal importance which attaches to them is in the direction of prognosis, for if the fragment be absolutely intracapsular it can derive its blood supply only through the ligamentum teres, which is, to say the least, a precarious method of existence and usually disappointing. In general it may be assumed that a fracture close to the head is intracapsular, but that when it occurs well out toward the shaft it may partake of both characters. In this connection the x-rays will afford, usually, more satisfactory information than can be obtained by even extensive or rude manipulation.

Impactionoccurs with considerable frequency in these cases, and, unless accompanied by too much deformity or displacement, is rather a fortunate occurrence, since by it is afforded an automatic splint which it should be the surgeon’s endeavor to not break apart. There can be no doubt, moreover, but that trifling degrees of impaction with incomplete fracture occur, especially in the aged, in many injuries to the hip. It would be the greatest misfortune to the patient in one of these cases to complete the separation, and when assured of the existence of such a lesion it is best to treat the case

as though it were a fracture. I am sure that many cases which have gone into court have been due to incomplete fractures with impaction, where there has been later absorption of bone, by which the femoral neck has been much shortened, so that recognizable deformity as well as more or less disability have resulted. Other changes comprised among those already described in the chapter on Joints, under the section on Arthritis Deformans, may also occur. Callus which has been at one time abundant may also undergo too great absorption.

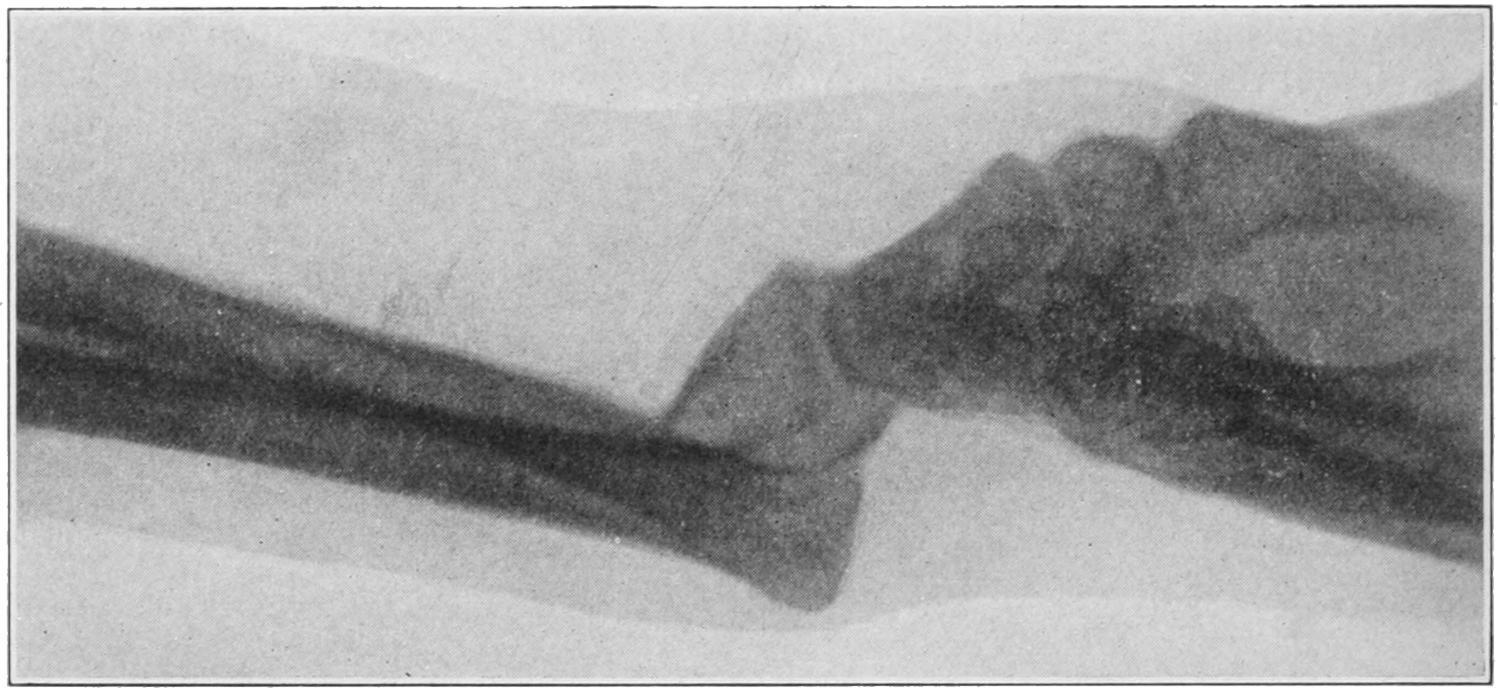

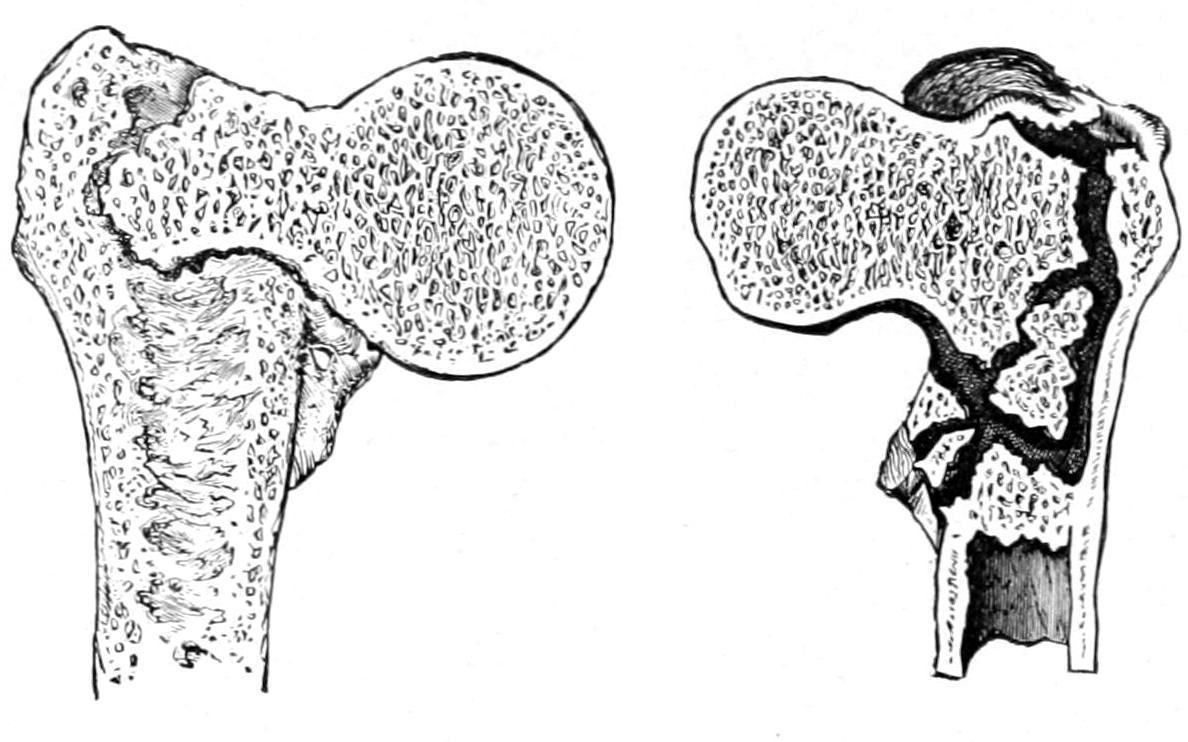

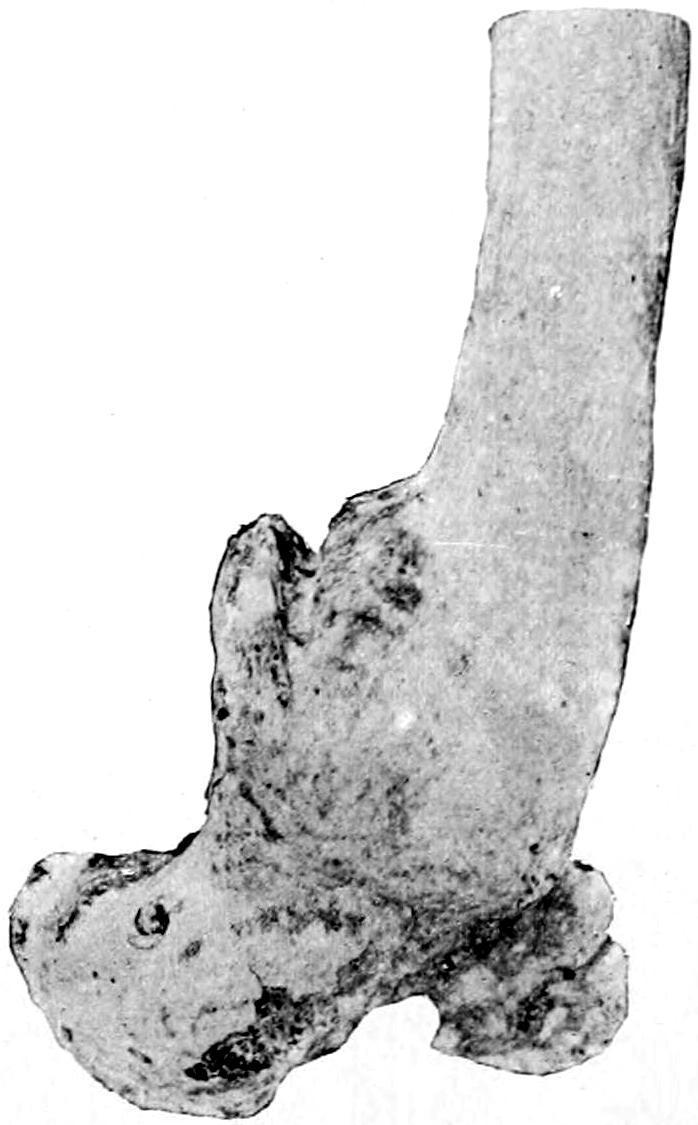

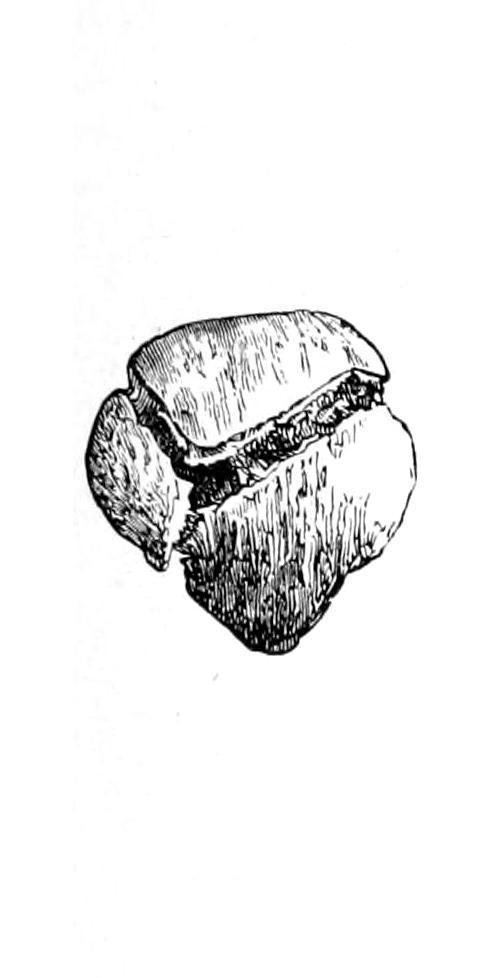

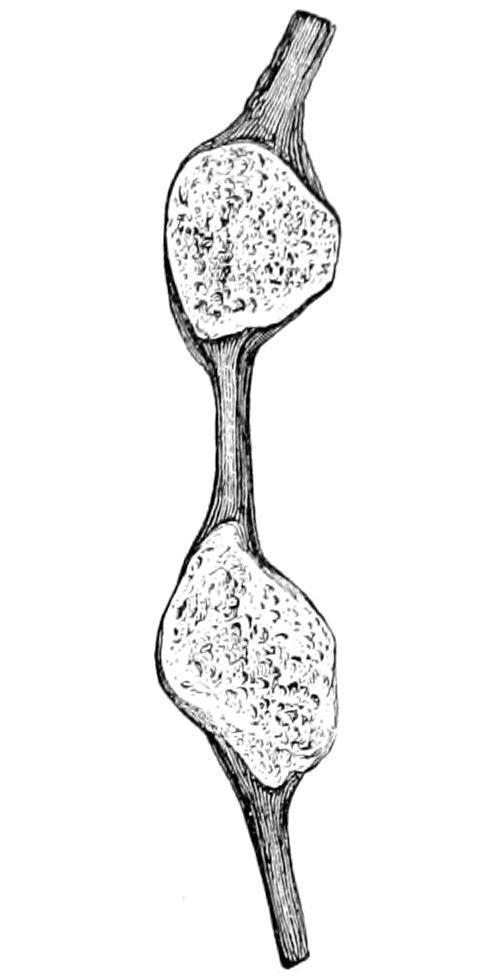

Sections of impacted extracapsular fractures of neck of femur, showing the degree of impaction and of splintering in different cases. (Erichsen.)

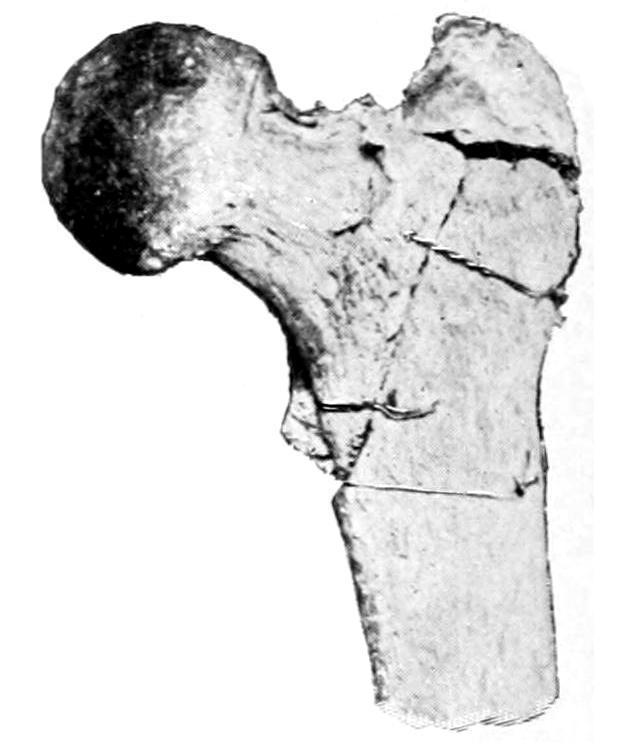

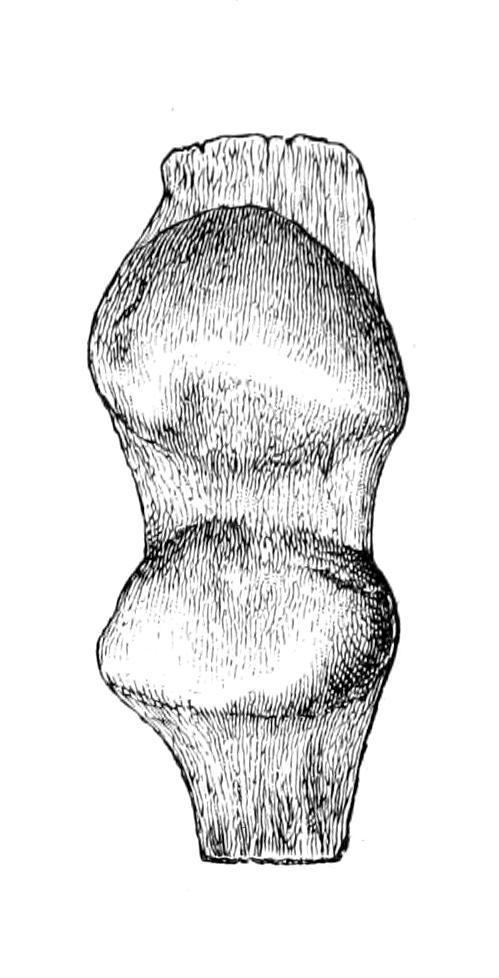

Extracapsular fracture of thigh.

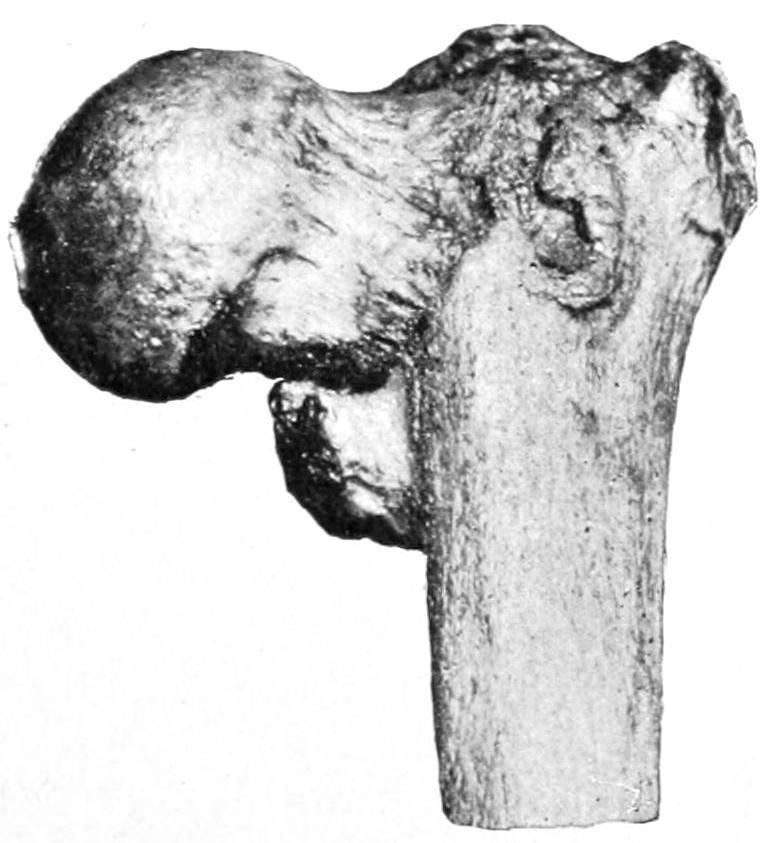

Fig. 311 illustrates extracapsular fracture and comminution. Figs. 312 and 313, also from specimens in the author’s collection, show some of the changes described above, including impaction, displacement, and some osteophytic outgrowth.

Signs of fracture of the neck of the femur of special import are history of injury, pain, loss of function, shortening, rotary displacement, usually eversion, crepitus, relaxationofthefascialata, and disarrangement of the lines oftriangulation between the bony prominences of the pelvis and the trochanter. Diagnosis should be attempted with as little manipulation as possible lest impaction be dislodged. The patient should be placed upon a comfortably hard surface. Anesthesia will sometimes afford important aid. It should be ascertained, first, that there had been no previous injury which could produce shortening. If, then, shortening be apparent it is of itself almost a diagnostic sign. Such a limb is practically helpless, and unless the neck be so driven in upon itself as to produce impaction the foot will be usually everted, while the tension of the fascia lata will be relaxed and there will be fulness in Scarpa’s triangle. Absolute inability to use the limb implies fracture without impaction. Should the patient have been able to help himself or work after the injury, impaction may be safely assumed. The parts are exceedingly tender and pain is easily produced. Shortening is to be assumed only after

Impacted fractures of necks of femurs.

placing the limbs and body in a perfectlysymmetricalposition (the pelvis being at right angle with the spine), after which the measurement most usually made is from the anterior superior spine to the internal malleolus. Nélaton’slineis the shortest line which can be made to pass around the hip, in one plane, from the anterior superior spine to the tuberosity of the ischium. While the line is curved it should lie in the same plane. Normally this passes just over the great trochanter. If there be real shortening the trochanter should rise above this line to an extent corresponding with the shortening made out by other measurements. Still another method of measurement is to hold a straight edge opposite to the superior spine and perpendicular to the surface upon which the patient is lying; the distance between this edge and the great trochanter should be as much less than the distance found by similar measurement on the other side as the amount of shortening measured by the other methods. This is the easiest way to measure the lines included in Bryant’s iliofemoral triangle. Both are illustrated in Fig. 314. Impaction can sometimes be determined by comparing triangles drawn between three points on either side, these points being, respectively, the great trochanters, the anterior spine, and the centre of the pubis, which is common to both. The lower line of the triangle on the injured side should be shorter than on the other, in proportion as the head and the end of the shaft have been driven toward each other.

Nélaton’s line, dark. Bryant’s iliofemoral triangle, dotted. (Erichsen.)

Crepitusis a sign to be elicited with care and gentleness. Up-anddown movements of the thigh upon the side of the pelvis or gentle rotary movements, combined with circumduction of the knee, will yield it if it is to be easily detected. Every effort of this kind disturbs the injured bone and should be minimized as much as possible. One other sign of considerable value is the fact that if the patient be turned upon his face a fractured femoral neck will permit the leg to be hyperextended to a degree not permitted by the normal condition. In making this test the pelvis should be held firmly; it should be made but once, the intent being to disturb the parts as little as possible.

Diagnosis.

—The diagnosis of fracture is often easy, but in some cases it is accompanied by many difficulties. It would

be better to give the patient the benefit of a doubt and treat him for a fracture with rest than to subject him to excessive manipulation. Such an injury is not likely to be mistaken for anything else save a dislocation of the hip, although occasionally separation of the margin of the acetabulum might cause confusion.

Prognosis.

—The prognosis depends upon the age and vitality of the patient, the location and extent of the fracture, the method of treatment, and upon causes which seem at first foreign to the subject. Patients with pulmonary or cardiac trouble, who need frequent change in position, or perhaps absolute rest, are likely to develop something hurriedly which will disarrange ordinary calculations. Sometimes they die suddenly or they may develop pulmonary edema or hypostatic pneumonia. The circulation may be so poor as to lead to early development of bed-sores, while ordinary complications in prostatics, or habitual constipation in the aged, may make care and treatment exceedingly difficult. It should be emphasized, then, that treatment of the fracture alone is by no means all that these patients require, and prognosis means something more than what may merely happen to the bone. In this last respect, however, the better nourished the fragment the more likely is bony union to take place ifgood position can be maintained. When osseous union has failed patients get fairly useful limbs with fibrous or ligamentous union, even with one or two inches of shortening, and such patients may hobble about for years, with a cane or a crutch, with limbs that are semiserviceable.

Treatment.

—Of these cases it may be said that interests of life are paramount to those of limb, and the treatment should be directed to that which the patient can tolerate. Reasonably healthy, muscular people can bear the application of adhesive strips and traction such as the thin and delicate cannot tolerate. The ideal method is that by which sufficient traction is made to overcome all muscle pull which shall produce shortening, the measure of weight to be used in these cases being the effect thereby produced. Thus if twenty pounds be sufficient, well and good; if not, it should be increased to thirty or forty pounds, providing that the patient can tolerate it. At the same time a broad binder around the pelvis may

afford sufficient support with a tractable patient, while many will require a long sidesplint, extending from the axilla to beneath the foot, to which both body and the injured limb should be fastened, in order to more perfectly maintain that physiological rest which is so necessary. This last is the so-called “Physick” splint, which has been variously modified, while the method of traction has been usually spoken of as Buck’s extension. It seems well thus to commemorate the names of the American surgeons who showed the value of these methods. When a long side splint cannot be borne, sandbags 15 in. or 20 in. in length and 3 in. in diameter may be used to give support. Any decided tendency to eversion of the limb should be corrected as well as the shortening. When the long side splint is used the foot can be held in place with it and thus the position of the shaft of the femur controlled. At other times this may be done by flexing the knee and thus preventing upward rotation. In all methods of traction it is advisable to keeptheheelfreefromthebed, in order that the effect of the method may not be lost by the obstruction of the mattress.

Shortening resulting from overlapping. Overlapping fracture of

Fracture of upper third of femur. Vicious union.

femur.

Other methods of treatment of these fractures are common as well to those of the shaft, and will be considered later. These include the single and double inclined plane and the method by anterior suspension. In general the first indication is efficient traction. This should be made as efficiently as possible. When the patient cannot tolerate any of the usual methods, then the double-inclined plane may be used, the knee being hung over its apex, or anterior suspension may be practised. In severe cases patients should be simply made comfortable, with such local treatment as they can bear. It may be even necessary to place them in the semi-upright position in bed, in order to free the lungs, or to frequently change their position to avoid the formation of pressure sores.

—Fractures of the shaft of the femur are usually oblique and accompanied by considerable displacement, because of the powerful thigh muscles which tend to shorten the limb. These fractures are often compound, and occasionally the femoral fragment causes serious damage to important vessels or nerve trunks. When the fracture is just below the insertion of the psoas into the lesser trochanter this muscle tends to not only pull up but to externally rotate the upper fragment. Inasmuch as there is no way of controlling this muscle or the fragment, the fractured limb should be dressed upon an inclined plane, or in anterior suspension, in such a way as to make the axis of the shaft fall into line with that of the fragment. When the fracture is in the middle of the thigh, or lower, there is sufficient length of the upper portion so that pressure can be made upon it, or that psoas activity can be overcome. Fig. 315 illustrates the tremendous deformity that may result from neglect of these precautions. Fig. 316 illustrates a certain degree of overlapping without conspicuous other deformity. Fig. 317 shows the shortening which is often inevitable.

Muscle spasm should be overcome as an essential part of successful treatment, the most important feature in making traction being to use force sufficient to tire out and overcome the irritated muscles.

—Fractures of the lower end of the femur are usually the result of extreme violence, and may be classified as were those of the lower

Fracture of lower end of femur, with great displacement of condyles.

Fractures of the Shaft of the Femur.

Fractures of the Lower End of the Femur.

end of the humerus. When there is a supracondyloid fracture the two heads of the gastrocnemius will help to displace backward the upper end of the lower fragment to an extent permitting injury to the bloodvessels, while there is always marked shortening. Here the patella will be made unduly prominent, and there will be depression above it. Either condyle may be broken loose alone, or there may be intercondyloid or Tfractures which are serious because the amount of force required to produce them may have played serious havoc with the soft tissues. The joint capsule will probably be filled with blood, the ligaments rent, and perhaps the blood supply of the limb compromised. In such a case

as this the joint may be opened, the contents turned out, and the fragments readjusted and wired or fastened in place (Fig. 318). Epiphyseal separations, which may occur up to the twentieth year, are not essentially different, although lateral displacement is perhaps more common, while they are often compound.

Treatment.

—Oblique fractures of the femoral shaft can be more easily adjusted under the influence of powerful and continuous traction than the transverse, where lateral displacement and overlapping tend to occur. A more general application can be made of the method described above when dealing with fractures at the upper end of the shaft, i. e., when the upper fragment cannot be controlled the balance of the limb must be adjusted to it in whatever position it may be required to maintain. By the use of sufficient traction, combined with molded or other splints, a fair result may usually be obtained. In stout individuals it is by no means easy to determine just how the fragments lie, save by the use of the x-rays. If traction be so adjusted as to maintain the limb at equal length with the other the surgeon may feel that, with certain coaptation splints, he is doing the best he can. Application of the same rule given above would lead him to place the limb on a double inclined plane, in case of fracture near the knee-joint, in order that in this position the sural muscles (the calf) may be relaxed and backward displacement of the lower fragment be adjusted. If the apex of this plane be arranged sufficiently high, so that the patient’s knee is practically hung over it, and that the weight of the body makes sufficient countertraction, then the use of weight and pulley may not be necessary. Here, however, pressure which will be efficient may produce numbness, as will any long-continued pressure in the popliteal space, and after a few days it may be necessary to assume some other position. Fractures which loosen the condyles will need lateral pressure, while the position of each condyle may be controlled by the position of the leg, through the medium of the corresponding lateral ligament.

Extension band and foot-piece.

FIG. 320

Same, folded and ready for use.

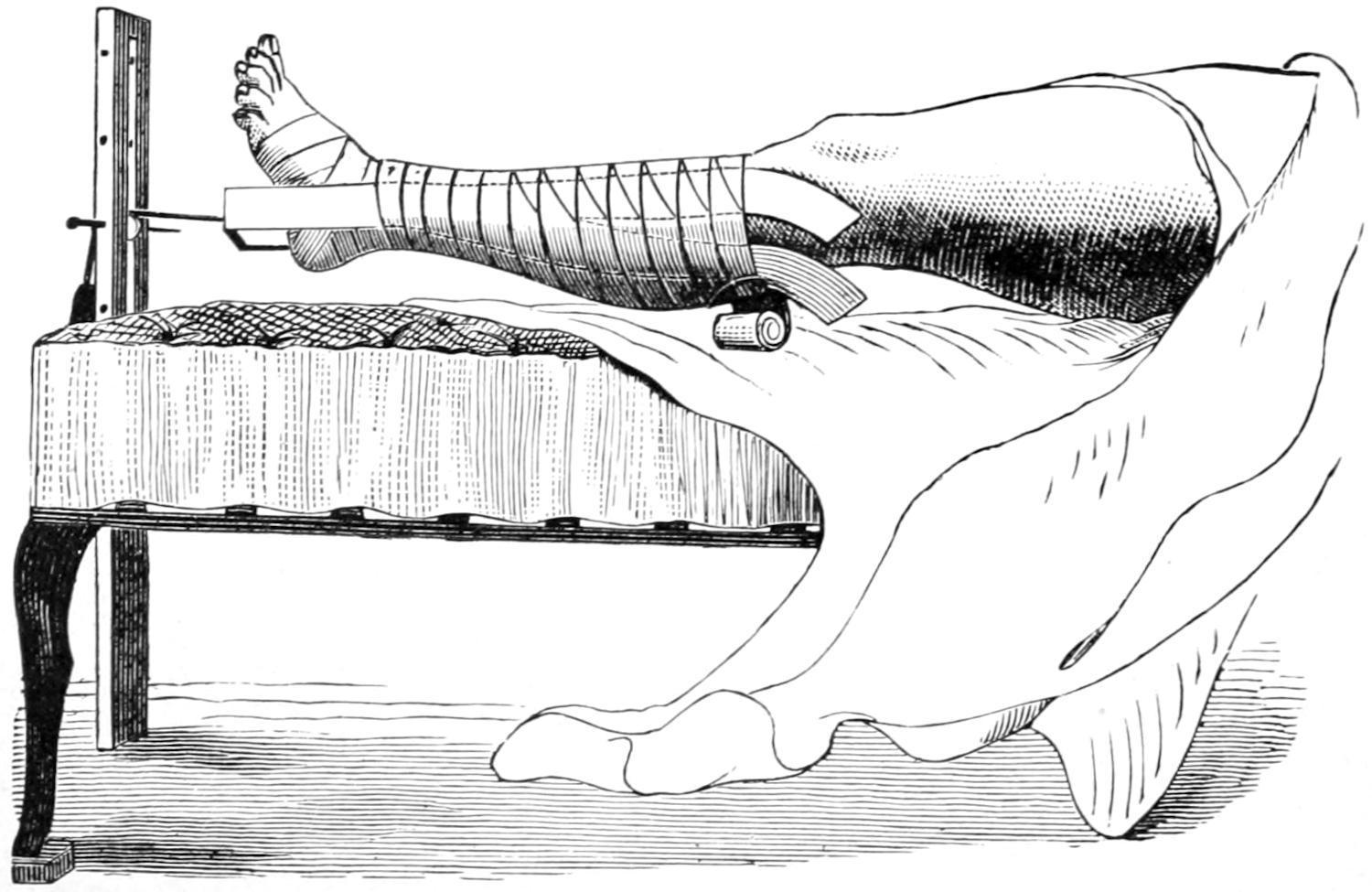

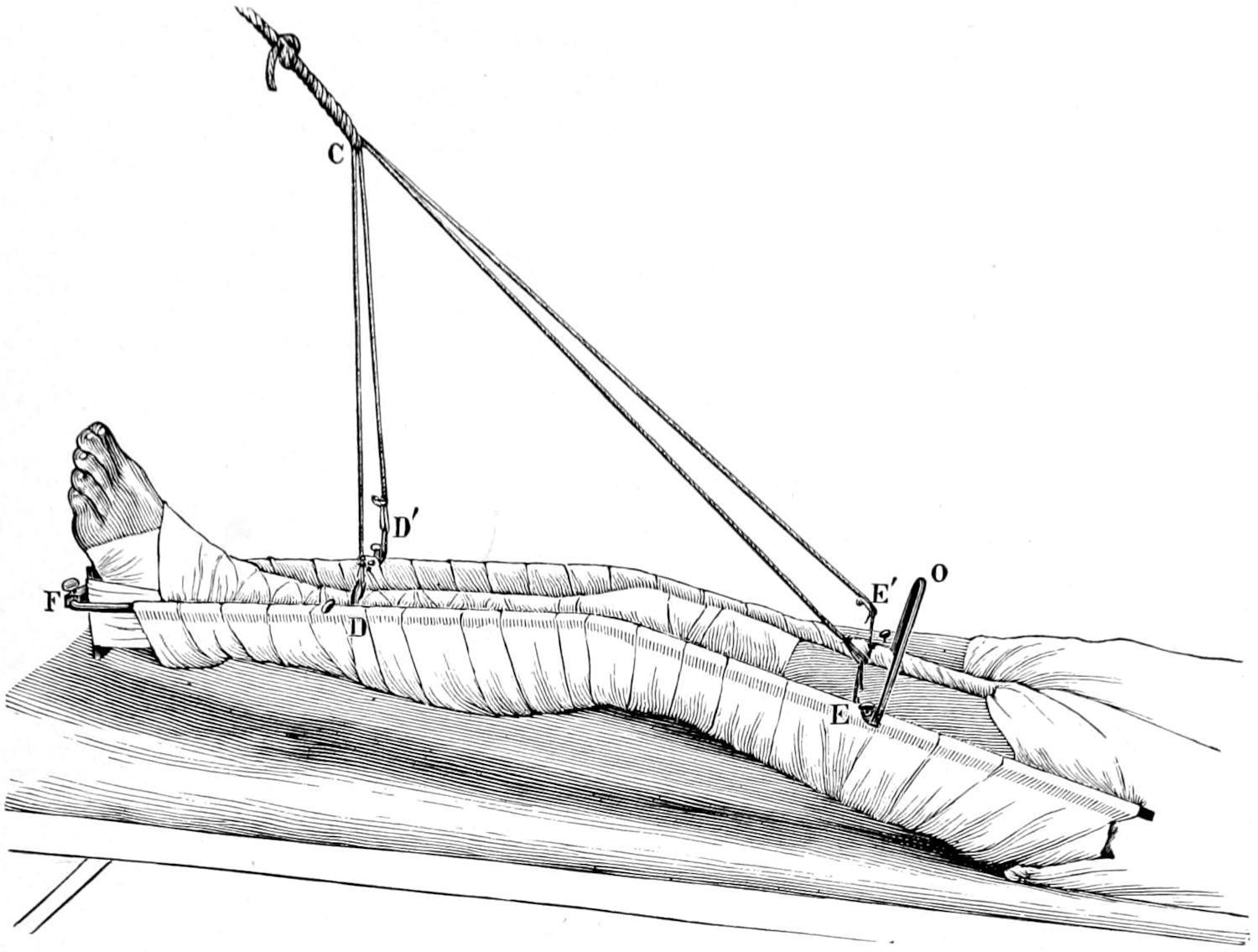

The standard “Buck’s extension” (for which latter word I prefer to substitute the term “traction”), by weight and pulley, with the limb in the extended position, is still the resort of the majority of surgeons, but combined with other support by long side splints or coaptation splints as may be needed. Fig. 321 illustrates the method of its use, except that the ends of the adhesive strips should be extended upward to a point nearly opposite the site of the fracture. The amount of weight to be used should be graduated to the effect produced. From ten to forty pounds, or even more, may be needed. After the muscles are thoroughly tired the amount of weight may be somewhat reduced[41] (Figs. 319, 320 and 321).

[41] Before applying the strips of adhesive, the best for the purpose being that made of moleskin spread with material with which zinc oxide is incorporated, the limb should be carefully washed and shaved and then completely dried. A little cotton should be placed over each malleolus, in order to avoid pressure-sores, while the strip of wood beneath the foot should be sufficiently wide to prevent or minimize this pressure. The heel should be kept off the mattress.

Mode of applying adhesive plaster. (When the dressings are completed the limb should not be allowed to rest on the bed.)

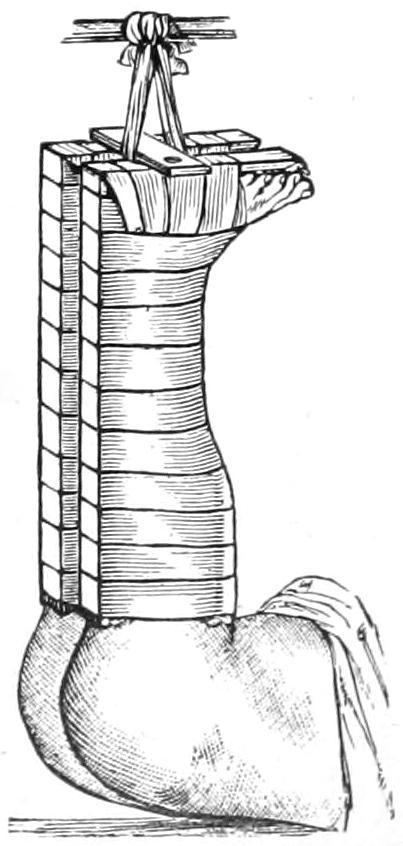

Continuous and anterior traction was devised by Nathan R. Smith, in the use of a so-called anteriorsplint, which was later modified and improved in device by Hodgen. The method of its use is shown in Fig. 322. Adhesive strips are used in this method as well, permitting the leg and foot to be attached to the lower bar of the wire frame. The position of the frame which contains the limb, swung within it upon turns or strips of bandage, is then controlled by a suspension apparatus, as shown, which tends to constantly pull the frame and its attached lower part of the limb away from the patient, the effect being to make a constant but gentle traction. If the point of suspension were placed directly above the limb there would be no traction whatever. The essential feature of the method, then, consists in arranging it as shown, so that the pull shall be oblique,

and that, according to the obliquity of the suspension cords, the amount of traction shall be regulated.

The Hodgen suspension splint.

In this method of treatment there is no violent attempt made at reduction or overcoming displacement, but dependence is placed, at least for two or three days, on the effect of the constant pull and its overcoming muscular activity. After this such added splints or expedients may be adopted as the case may require. The knee is usually flexed at a comfortable angle, the intent being not to lift the foot too high, so as to avoid being compelled to overcome this added weight, but to regulate the tension by the obliquity of the suspending cord.

Fracture of the femur in a child treated by vertical extension. (Bryant.)

This method has found favor in the West under the enduring influence of Hodgen’s teaching. In the East it is not so generally practised. It has, however, several advantages, as follows: (1) Equably perfect and comfortable extension; (2) easy adjustment; (3) easy exposure for inspection; (4) when a fracture is compound it permits of easy application of dressings; (5) adaptability to nearly all fractures of the femur. It is peculiarly serviceable for feeble and aged patients who chafe at restraint. If it be desirable to flex the knee to a considerable degree this can be done, e.g., in fractures near the lesser trochanter.

In fractures of the thigh, patients are frequently disturbed by muscle spasms occurring during sleep. This can usually be obviated or minimized by suitable doses of sulphonal, given early in the evening.

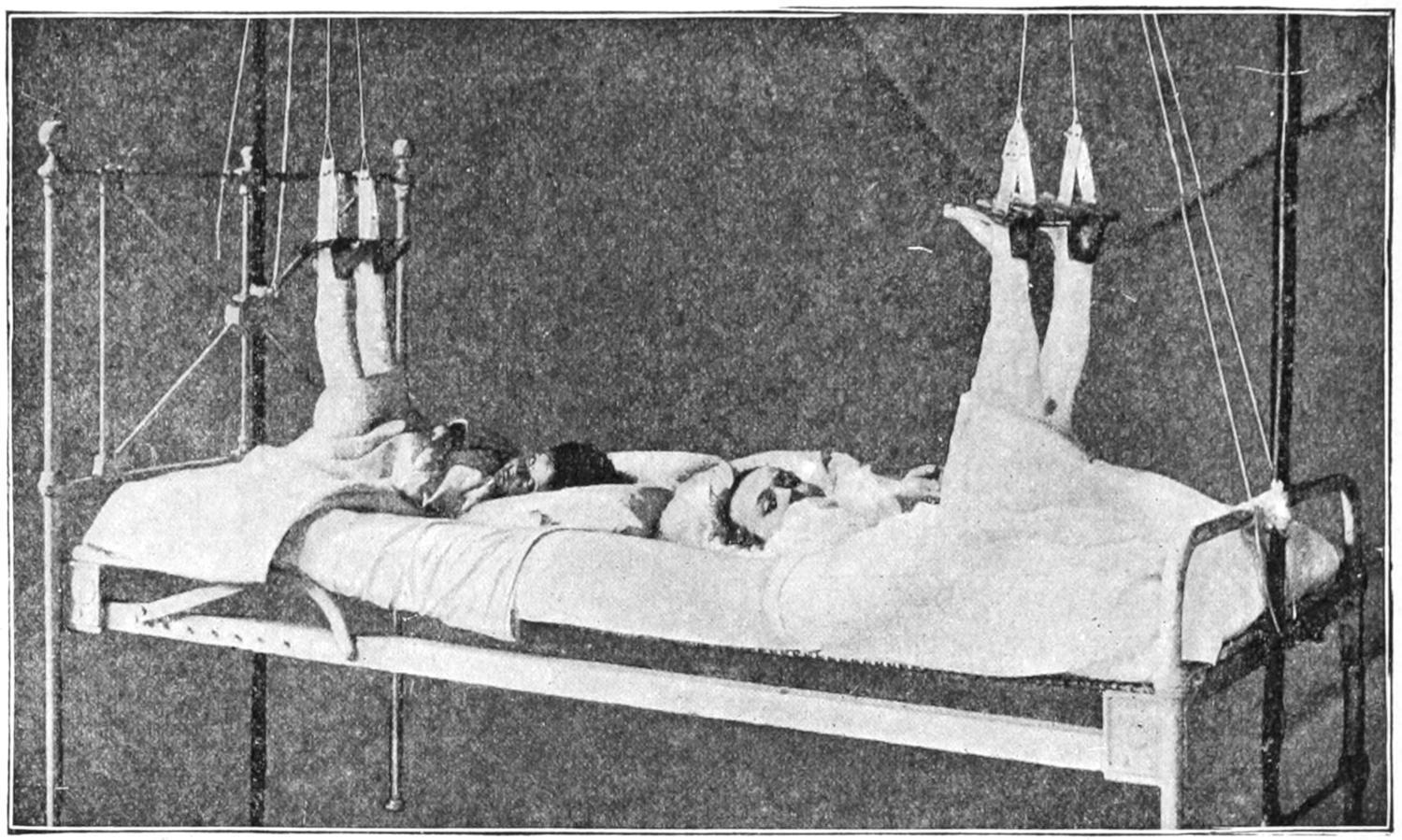

Fractures of the femur in children are not uncommon. In those who still wear diapers, and perhaps in those a little older, these injuries may be best treated by vertical suspension, with sufficient weight to overcome all shortening. Here the adhesive strips and the suspending cords should be attached to both limbs alike, in order to have sufficient access to the perineum, and in order to judge of the effect which we are obtaining. Figs. 323 and 324 illustrate this method.

Plaster-of-Paris dressings for fractures of the thigh appeal especially to those who are most familiar with the use of the material. Some patients with fracture of the neck of the femur may be early put in the erect posture, upon an elevated surface, allowing the injured limb to hang down while the patient rests upon crutches. In this upright position, with the down-hanging leg, to which traction can be made by an assistant, a plaster-of-Paris spica may be applied, extending from the waist-line down to or below the knee. As a limb is thus dressed so it will heal, and it is of importance that complete reduction be effected as a part of the procedure.

FRACTURES OF THE PATELLA.

During the active period of middle life the patella is the bone most frequently broken by muscular violence. In many cases it is practically cracked over the condyles, as one would crack a piece of wood over the knee. If direct force be applied, as by a fall, in connection with the above, the effect is even more marked. In such cases the fracture is sometimes comminuted (Fig. 325), or the line of fracture may run more or less perpendicularly rather than horizontally. Ordinarily, however, these fractures are transverse, while the upper fragment is pulled upward, sometimes to a considerable distance, by the powerful extensors of the leg. When the fracture runs vertically the displacement is very slight. Occasionally these fractures are compound, a most undesirable complication, since the knee-joint is thus exposed to infection, from which it suffers unless first attention be prompt and scientific. There

Fracture of the thigh; vertical suspension. The fracture is compound in the patient on the right. (Stimson).

is usually sufficient hemorrhage to distend the joint cavity, and it may at first be quite impossible to bring the fragments near enough to each other to get crepitus, but the loss of the power of extension and the evident gap between the fragments will serve to make diagnosis positive, at least in all transverse fractures. A vertical fracture without much separation is a milder form of injury which may be regarded in a much more favorable light (Figs. 326, 327 and 328).

In these transverse fractures it is rare that bony union can be secured by non-operative methods. This is not only because of the difficulty in maintaining parts in apposition, but because it is notably the case that fragments of periosteum or other tissue drop in between bony surfaces and tend to prevent their actual contact, no matter how firmly they may be pressed toward each other. Osseous union then may occur without operation, but is rare. The best that can be expected is fibrous union, the intervening fibrous band being short or long, according to the success met with in treatment and to the amount of strain later put upon it by too early use of the limb. Even with two inches of fibrous tissue intervening patients are not completely disabled. The usefulness of a limb under these conditions, however, is seriously impaired. Something will depend, also, on the extent to which the joint capsule and the aponeurosis terminating the vasti muscles may have suffered.

Treatment.

—The non-operative treatment consists in placing such a limb upon a single inclined plane, for the purpose of relaxing the quadriceps extensor group. In this position the limb should be maintained for at least from ten to fourteen days. Some expedient should be added, so soon as swelling has subsided, by which the upper fragment can be coaxed downward toward its fellow. A neatly molded splint, formed out of gutta-percha or of plaster of Paris, may be fitted to the thigh above the fragment, held in position, and then drawn downward by elastic traction on either side of the leg, the principle of traction being thus given a special application. Something of this kind should be done if the fragments are to be approximated to each other.

Comminuted fracture.

Stellate fracture of the patella. (Erichsen.)

Fracture of patella, united by ligamentous tissue. (Erichsen.)

Side view of same.

The more completely mechanical method, partaking of the operative, is afforded by the use of certain hooks, whose points are permitted to pass through the skin above and below the fragments and to engage in the bone. By a screw mechanism these points are drawn toward each other, and thus approximation is effected. This method was first devised by Malgaigne and is usually known under his name, although his device has been much improved. This is far from ideal, and yet has given good results in some cases. The surgeon should constantly guard against infection through the punctures.

By far the most ideal method, when it can be suitably carried out, is the open operation, a transverse incision being made across the