Generating artificial sensations with spinal cord stimulation in primates and rodents Amol P. Yadav & Shuangyan Li & Max O. Krucoff & Mikhail A. Lebedev & Muhammad M. Abd-El-Barr & Miguel A.L. Nicolelis https://ebookmass.com/product/generatingartificial-sensations-with-spinal-cordstimulation-in-primates-and-rodents-amol-p-yadavshuangyan-li-max-o-krucoff-mikhail-a-lebedevmuhammad-m-abd-el-barr-miguel-a-l-nicolel/

Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Elsevier Weekblad - Week 26 - 2022 Gebruiker

https://ebookmass.com/product/elsevier-weekbladweek-26-2022-gebruiker/

Jock Seeks Geek: The Holidates Series Book #26 Jill Brashear

https://ebookmass.com/product/jock-seeks-geek-the-holidatesseries-book-26-jill-brashear/

The New York Review of Books – N. 09, May 26 2022

Various Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-york-review-ofbooks-n-09-may-26-2022-various-authors/

Calculate with Confidence, 8e (Oct 26, 2021)_(0323696953)_(Elsevier) 8th Edition Morris Rn Bsn Ma Lnc

https://ebookmass.com/product/calculate-withconfidence-8e-oct-26-2021_0323696953_elsevier-8th-edition-morrisrn-bsn-ma-lnc/

1 st International Congress and Exhibition on Sustainability in Music, Art, Textile and Fashion (ICESMATF 2023) January, 26-27 Madrid, Spain Exhibition Book 1st Edition Tatiana Lissa

https://ebookmass.com/product/1-st-international-congress-andexhibition-on-sustainability-in-music-art-textile-and-fashionicesmatf-2023-january-26-27-madrid-spain-exhibition-book-1stedition-tatiana-lissa/

Cortical Evolution in Primates: What Primates Are, What Primates Were, and Why the Cortex Changed Steven P. Wise

https://ebookmass.com/product/cortical-evolution-in-primateswhat-primates-are-what-primates-were-and-why-the-cortex-changedsteven-p-wise/

Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord,

and

ANS 3rd Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/clinical-anatomy-of-the-spinespinal-cord-and-ans-3rd-edition/

Can Artificial Intelligence Do Better than Humans at Leadership? M A P Willmer

https://ebookmass.com/product/can-artificial-intelligence-dobetter-than-humans-at-leadership-m-a-p-willmer/ Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology in Medicine Visakh P. M.

https://ebookmass.com/product/nanomaterials-and-nanotechnologyin-medicine-visakh-p-m/

BrainStimulation14(2021)825 836

Contentslistsavailableat ScienceDirect

BrainStimulation

journalhomepage: http://www.journals.elsevi er.com/brain-stimulation

Generatingartificialsensationswithspinalcordstimulationin primatesandrodents

AmolP.Yadav a, b, *,ShuangyanLi e, m, n,MaxO.Krucoff j, k,MikhailA.Lebedev d, l , MuhammadM.Abd-El-Barr c,MiguelA.L.Nicolelis c, d, e, f, g, h, i

a DepartmentofNeurologicalSurgery,IndianaUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Indianapolis,IN,46202,USA

b PaulandCaroleStarkNeurosciencesResearchInstitute,IndianaUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Indianapolis,IN,46202,USA

c DepartmentofNeurosurgery,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

d CenterforNeuroengineering,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

e DepartmentofNeurobiology,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

f DepartmentofBiomedicalEngineering,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

g DepartmentofPsychologyandNeuroscience,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

h DepartmentofNeurology,DukeUniversity,Durham,NC,27710,USA

i EdmondandLilySafraInternationalInstituteofNeuroscience,Natal,59066060,Brazil

j DepartmentofNeurosurgery,MedicalCollegeofWisconsin & FroedtertHealth,Wauwatosa,WI,53226,USA

k DepartmentofBiomedicalEngineering,MarquetteUniversity & MedicalCollegeofWisconsin,Milwaukee,WI,53233,USA

l SkolkovoInstituteofScienceandTechnology,30BolshoyBulvar,Moscow,143026,Russia

m StateKeyLaboratoryofReliabilityandIntelligenceofElectricalEquipment,SchoolofElectricalEngineering,Tianjin,300130,PRChina

n TianjinKeyLaboratoryBioelectromagneticTechnologyandIntelligentHealth,HebeiUniversityofTechnology,Tianjin,300130,PRChina

articleinfo

Articlehistory:

Received24December2020

Receivedinrevisedform

1April2021

Accepted30April2021

Availableonline18May2021

Keywords:

Spinalcordstimulation

Neuroprosthetics

Somatosensation

Artificialsensoryfeedback

Non-humanprimates

abstract

Forpatientswhohavelostsensoryfunctionduetoaneurologicalinjurysuchasspinalcordinjury(SCI), stroke,oramputation,spinalcordstimulation(SCS)mayprovideamechanismforrestoringsomatic sensationsviaanintuitive,non-visualpathway.Inspiredbythisvision,herewetrainedrhesusmonkeys andratstodetectanddiscriminatepatternsofepiduralSCS.Thereafter,weconstructedpsychometric curvesdescribingtherelationshipbetweendifferentSCSparametersandtheanimal'sabilitytodetect SCSand/orchangesinitscharacteristics.Wefoundthatthestimulusdetectionthresholddecreasedwith higherfrequency,longerpulse-width,andincreasingdurationofSCS.Moreover,wefoundthatmonkeys wereabletodiscriminatetemporally-andspatially-varyingpatterns(i.e.variationsinfrequencyand location)ofSCSdeliveredthroughmultipleelectrodes.Additionally,sensorydiscriminationofSCSinducedsensationsinratsobeyedWeber'slawofjust-noticeabledifferences.These findingssuggest thatbyvaryingSCSintensity,temporalpattern,andlocationdifferentsensoryexperiencescanbe evoked.Assuch,wepositthatSCScanprovideintuitivesensoryfeedbackinneuroprostheticdevices.

© 2021TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierInc.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Lackofsensoryfeedbackfromabrain-controlledactuatoror prostheticdeviceisamajorhindrancetosuccessfulintegrationof theneuroprosthesisinactivitiesofdailylifeandrehabilitative protocols[1 3].Thesomatosensorycortex(S1)andthalamushave beenproposedaspotentialtargetsforneurostimulationthatcould producenaturalisticsomatosensorypercepts[4 10].However,

* Correspondingauthor.DepartmentofNeurologicalSurgery,IndianaUniversity SchoolofMedicine,Indianapolis,IN,46202,USA.

E-mailaddress: apyadav@iu.edu (A.P.Yadav).

stimulatingthesebrainareasrequiressurgicalimplantationofdeep intracranialelectrodes aprocedureassociatedwithsignificant risks.Whileperipheralnervestimulationprovidesalessinvasive alternative,sensationsevokedwiththismethodarehighlylocalized,andthuslimitedintheirapplicabilityasageneral-purpose sensoryinputpathwaytothebrain[11 13].Previously,ina proof-of-conceptstudyitwasdemonstratedthatelectricalstimulationofthedorsalsurfaceofthespinalcordcanbeusedto transmitsensoryinformationbetweenmultiplerodentbrains[14]. Buildingonthispreviouswork,hereweexploredwhether nonhumanprimatescanlearntodetectanddiscriminateartificial sensationsgeneratedwithdorsalthoracicepiduralspinalcord

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.04.024 1935-861X/© 2021TheAuthor(s).PublishedbyElsevierInc.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ).

stimulation(SCS).TounderstandtherelationshipbetweenSCS parametersandsensorydetection whichiscriticalforthe developmentofnovelneuroprostheticdevices weperformeda robustpsychophysicalevaluationoftheanimals'abilitytodetect sensationswhileSCSparameterswerealtered.Wealsoexamined howsensorydiscriminationchangeswhenSCSparametersare variedinbothrodentandprimatemodels,andweaskedwhether animalscanlearntodiscriminatesensationsgeneratedbySCS patternsthatvaryinfrequencyandspatiallocation.Aftertraining theanimalstodiscriminateSCSpatterns,wedeterminedwhether artificialsensationsevokedbySCSofvariablefrequencyfollow Weber'slawofjust-noticeabledifferences(JND)-acriticalproperty definingsensorydiscrimination.

Results

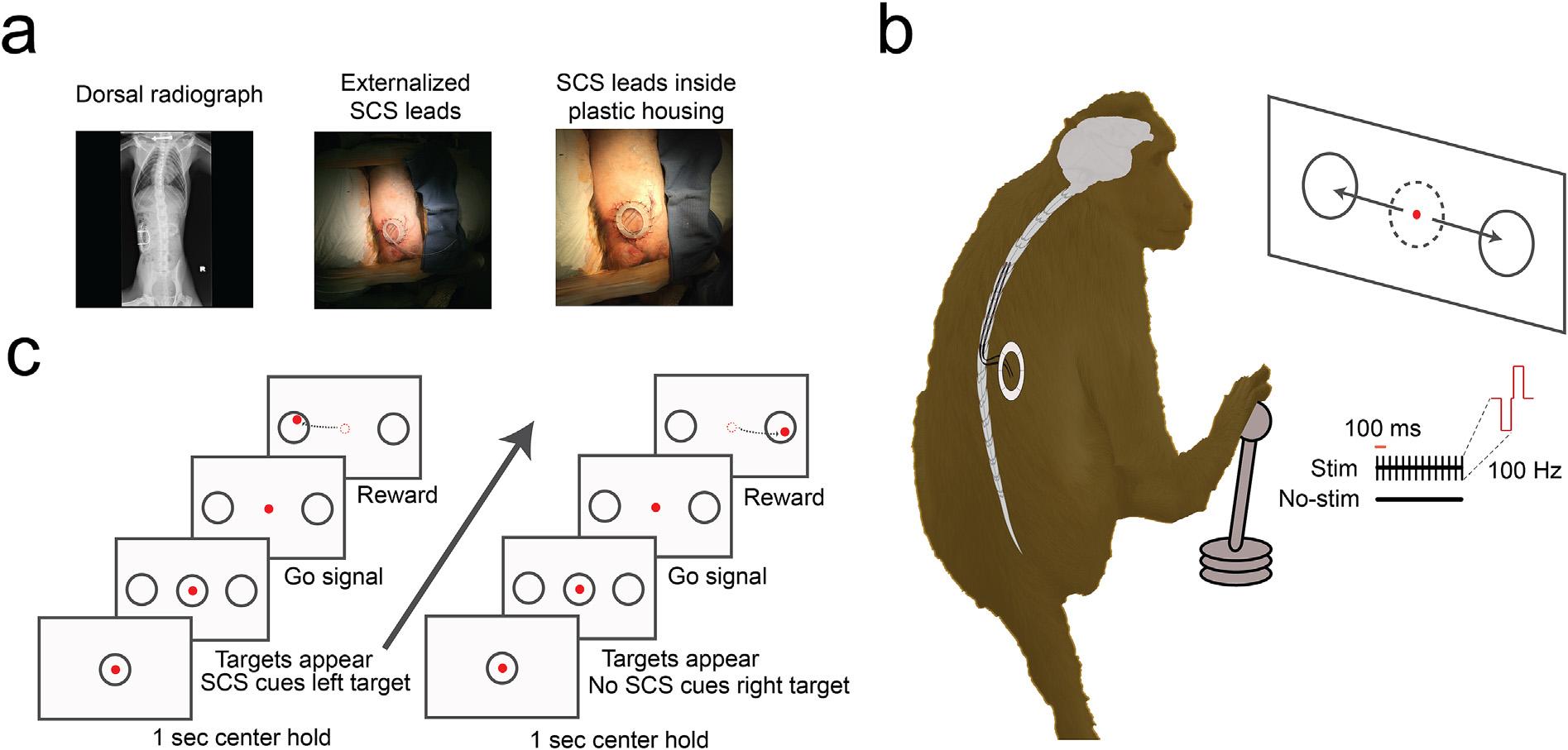

Weimplantedthreerhesusmonkeyswithpercutaneous epiduralSCSelectrodesatthedorsalthoracicspinalleveland trainedthemtoperformatwo-alternativeforcedchoicetask (2AFC)usingajoystick-controlledcursor(Fig.1a, Supplementary Figure1).Inatypicalexperimentalsession,amonkeywasseated inachairinfrontofamonitorthatdisplayedtask-relatedcues.The animalsmovedahand-heldjoysticktocontrolacursoronascreen (Fig.1b).

Atypicaltrialconsistedofabrief1scenterholdperiodafter whichtwotargetsappeared.Afterabriefpreparatoryperiodof 100 1000msduringwhichatrialcuewaspresented,themonkeys hadtomovethecursorintooneofthetargetstoobtainajuice reward.Monkeyswereinitiallytrainedtoidentifythecorrecttarget usingavisualcue;however,duringtheexperimentalsessions,no visualcueswerepresented,andtheyselectedatargetbyinterpretingSCScuesalone.Inthedetectiontask,monkeyshadtoselect thelefttargetifSCSwasdeliveredduringthepreparatoryperiod andrighttargetifnoSCSwasdelivered(Fig.1c).Inthe

discriminationtask,monkeyshadtoselectthelefttargetforthe 100Hzstimuliandrighttargetforthe200Hzstimuli(frequency discrimination)andthelefttargetforelectrodepair1andright targetforelectrodepair2(spatialdiscrimination).

MonkeyslearnedtodetectSCSstimuli

MonkeysM,O,andKlearnedtodetectSCS-inducedsensory perceptsevokedusingpercutaneousdorsalthoracicepidural electrodes(T7formonkeyM,T5-T6formonkeyO,T5-T6for monkeyK).Performanceofallmonkeysstartedbelowchance levelsof50%andreachedabove90%afterlearning(Fig.2a).MonkeyMstarteddetectionperformanceat49%andreacheda maximumof93%in16days;monkeyOstartedat49%andreached amaximumof97%in10days;andmonkeyKstartedat41%and reachedamaximumof90%in8days.

Electrodethresholdsandelectrodemapping

OncethemonkeyslearnedtodetectSCSsensations,weused psychometricanalysistodeterminethedetectionthresholdsfor differentelectrodecombinations(Fig.2b).Weobservedthatthe detectionthresholdsvariedfrom315.6 mAto340 mAformonkeyO and197 mA 748 mAformonkeyKfordifferentcathode-anode electrodepairs(Fig.2c,right).Onceelectrodethresholdswere determined,wemappedthebipolarelectrodepairstolocationson themonkey'sbodybystimulatingatsuprathresholdamplitudes andobservingstimulation-inducedminormuscletwitchesorskin flutter.Weobservedthatmuscletwitches/skin flutterwereelicited inthetrunkandabdomenareaonlyatsuprathresholdvaluesbut notatsensorythresholdvalues(Fig.2c).Wealsonotedthatinboth monkeysKandOexperimentallydeterminedsensorythresholds werealwayslowerthantheobservedmotorthresholdsforeach cathode-anodeelectrodepair(SupplementaryFigure3b).

Fig.1. Surgeryandexperimentaltasksetup.a)Weimplantedthreenon-humanprimates(rhesusmonkeys)withSCSpercutaneousleadsovertheT6-T10dorsalepiduralsurfaceof thespinalcord.Leadswereexternalizedfromthelowerbackareaandsecuredinsideacustomplastichousing.Leadsweremanuallyaccessedbytheexperimenterfordailytraining andconnectedtoacustompulsestimulator.b)Monkeyswereseatedinaprimatechairinfrontofacomputermonitorwithaccesstoahand-controlledjoystick.Theyparticipated inatwo-alternativeforcedchoicetask(2AFC)bymovingthejoystickcontrollingacursoronthescreeninordertoreceiveajuicereward.c)Oneachtrial,monkeyshadtoholdthe cursorinsidethecentercirclefor1s.Afterthat,targetsappearedontheleftandrightsideofthecenter.Monkeyswerepresentedwith ‘SCS-ON’ (biphasic,100Hz,200 ms,1s)cueor ‘SCS-OFF’ cuewhenthetargetsappeared.Afterabrief,variableholdperiod(100 1000ms),thecentercircledisappearedwhichindicatedthemtomovethejoystick.Monkeyshad tomovethecursorinsidethelefttargeton ‘SCS-ON’ trialsandinsidetherighttargeton ‘SCS-OFF’ trials.Correctresponseresultedinjuicereward.IntheSCSdiscriminationtask, stimulationwasdeliveredat200 msfor1s.Monkeyshadtoselectlefttargetfor100Hzstimulusandrighttargetfor200Hzstimulusinthefrequencydiscriminationtask.Forspatial discriminationtask,monkeyshadtochooselefttargetwhenstimulationwasdeliveredatelectrodepair1andrighttargetforstimulationatelectrodepair2.

A.P.Yadav,S.Li,M.O.Krucoffetal.

Sensitivitytodetectionofsensoryperceptsinprimates

Thereafter,weinvestigatedthepsychophysicalrelationship betweenstimulationparametersanddetectionofsensorypercepts byvaryingstimulationamplitudesalongwithstimulationfrequency,pulse-width,ordurationofstimulationwhilekeepingthe othertwoparametersconstant.

Wevariedamplitudefrom50 mAto800 mAforpulse-widthsof 50 ms,100 ms,200 ms,and400 msformonkeyK,andpulse-widthsof 100 ms,200 ms,and400 msformonkeyO.Frequencyanddurationof stimulationwereheldconstant(Fig.3aand3e,and Supplementary Figure2a).Weobservedthatstimulusdetectionthresholdsignificantlydecreasedwithincreasingstimulationpulse-width(p < 0.05, repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA)forbothanimals(Fig.3h).

Wevariedamplitudefrom50 mAto800 mAforfrequenciesof 10Hz,20Hz,50Hz,100Hz,200Hz,and500HzformonkeyK,and frequenciesof20Hz,50Hz,100Hz,200Hz,and500Hzformonkey Owhilekeepingpulse-widthanddurationofstimulationconstant (Fig.3band3f,and SupplementaryFigure2b).Weobservedthat stimulationdetectionthresholdsignificantlydecreasedwith increasingstimulationfrequency(p < 0.05,repeatedmeasuresonewayANOVA)forbothanimals(Fig.3i).

Wevariedamplitudefrom50 mAto600 mAfordurationof 50ms,100ms,500ms,and1000msformonkeyK,andamplitude between50 mAand700 mAfordurationof50ms,100ms,and 500msformonkeyO,whilekeepingpulse-widthandfrequencyof stimulationconstant(Fig.3cand3g,and SupplementaryFigure2c). Weobservedthatstimulationdetectionthresholdsignificantly decreasedwithincreasingstimulationduration(p < 0.05,repeated measuresone-wayANOVA)forbothanimals(Fig.3j).

InmonkeyK,wevariedbothfrequencyanddurationofstimulationwhilekeepingamplitudeandpulse-widthofstimulation constant.Weobservedthatasthefrequencyofstimulation increased,thedurationofstimulationtoreachdetectionthreshold decreased(Fig.3dand3k).MonkeyKwasabletodetectasensory perceptgeneratedbymerelytwostimulationpulsesdeliveredat 1000Hz.

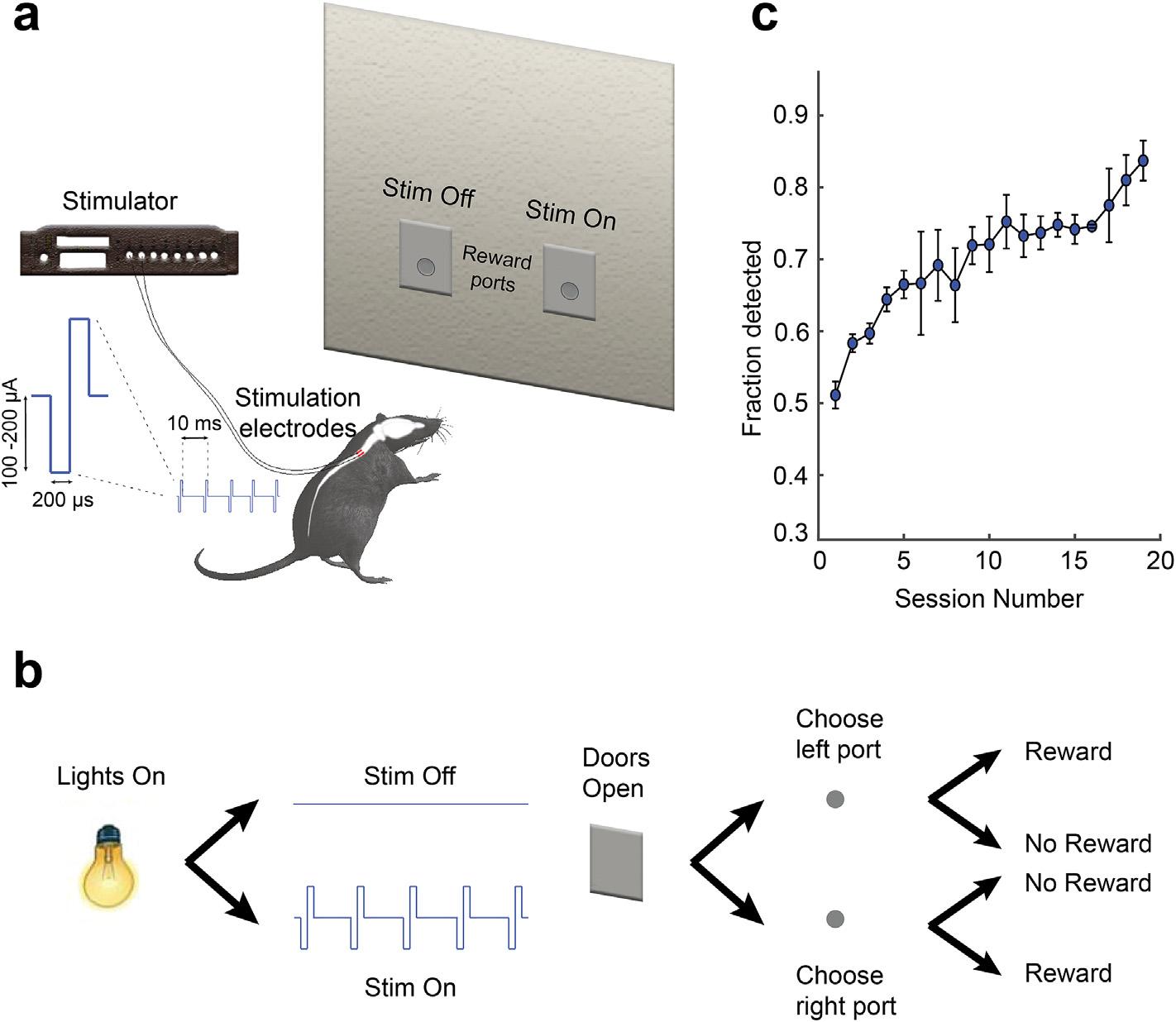

Sensitivitytodetectionofsensoryperceptsinrats

Inaproof-of-principlestudy,wepreviouslyshowedthatrats learntodetectsensationsgeneratedbySCSdeliveredatT2spinal level[14].Inordertostudythepsychophysicalperformanceofrats pertainingtosensorydetection,initiallywetrainedratstodetect

Fig.2. MonkeyslearnedtodetectSCSstimuli.a)Learningcurves(sigmoidal fits)formonkeysM,O,andKshowingbehavioralperformance(fractioncorrecttrials)asafunctionof trainingdays.b)PsychometricfunctionshowingfractiontrialsdetectedasafunctionofstimulationamplitudeinmonkeyO.Detectionthresholdis definedasamplitudeatwhich monkeysachieved75%performanceondetectiontask.c)Mappingofbipolarelectrodepairs(asindicatedbypairsof±signs)onmonkeyK'sbodywherestimulationonright-side electrodeatsuprathresholdamplitudeelicitedminormuscletwitchesorskin flutter.Mappedareaiscolorcodedbyelectrodepairsandcorrespondingsensorythresholdsshownon right.MonkeybodyshapeisadaptedfromRef.[15].

Fig.3. PsychophysicalevaluationofSCSsensorydetectionwithvaryingstimulationparametersinprimates.OncemonkeyslearnedtodetectSCSstimuliatthestandardparameters (frequency:100Hz,pulsewidth:200 ms,duration:1s),weallocateddifferentblocksofsessionswhere(pulsewidth & amplitude;panels ‘a’ and ‘e’);(frequency & amplitude;panels ‘b’ and ‘f’);and(duration & amplitude;panels ‘c’ and ‘g’)werevariedwhilekeepingotherparametersconstant.InmonkeyK,inaseparateblock,frequencyanddurationwasvaried withotherparametersconstant(pulsewidth:200 msecandamplitude:325 mA).Psychometriccurvesina-garesigmoidal fits.Panelsa drepresentpsychometriccurvesformonkey K,whilepanelse grepresentpsychometriccurves fittedtodataaveragedacrossmonkeysKandO(circlesanderrorbarsaremean ± sem).Panelsh,i,j,indicatenormalized

SCSstimuliusinga2-AFCtaskinaslightlymodifiedbehavioral chamber(Fig.4aand4b).Wetrained fiveratstodetectSCSstimuli deliveredattheT3spinallevel(frequency:100Hz,pulse-width: 200ms,duration:1sec,biphasicpulsesat243.7±57.9mA, Fig.4c).

Onceratslearnedthebasicdetectiontask,wevariedstimulation parameterssuchas:pulsewidth(50 400 ms);frequency (10 500Hz);andduration(50 1000ms)independentlywith stimulationamplitude(Fig.5a,5d pulsewidth;5b,5e frequency;and5c,5f duration).Similartotheresultsinmonkeys, weobservedthatstimulationdetectionthresholdssignificantly decreasedwithincreasingpulse-width(Fig.5g,p < 0.0001, repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA),frequency(Fig.5h, p < 0.0001,repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA)andduration (Fig.5i,p < 0.05,repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA)forallrats.

Sensorydiscriminationinprimates

WethentrainedmonkeysKandOtodiscriminateSCSthat variedinfrequencyaswellaslocationofstimulation.Onfrequency discrimination(100Hzvs200Hz, Fig.6a),monkeyO'sperformance improvedfrom29%onday1to96%onday17oftraining,while monkeyK'sperformanceimprovedfrom74%onday1to81%onday 11(Fig.6b).Spatialdiscriminationwasachievedbystimulating electrodepair1versuselectrodepair2(Fig.6c),wheremonkeyO's performanceimprovedfrom46%onday1to97%onday11and monkeyK'sperformanceimprovedfrom74%onday1to86%onday 7(Fig.6d).

SensorydiscriminationandWeber'slawinrats

Inaproof-of-principlestudy,wehadpreviouslyshownthatrats canlearntodiscriminateuptofourdifferentpatternsofstimulation[14].Inourcurrentwork,wetrainedratstosystematically discriminateSCSstimuliwithspecificfrequenciesusingthesame behavioralsetupthatwasusedforthedetectiontask (SupplementaryFigure5a).Inthebasictraining,ratslearnedto discriminatebetween10Hzand100Hzofstimulationdeliveredat pulse-widthof200 msec,anddurationof1s(Supplementary Figure5b).Thereafter,westudiedwhetherdiscriminationofsensationsinducedbydifferentstimulationfrequenciesfollowsthe rulesofWeber'slaw[16],whichstatesthatJust-NoticeableDifferences(JNDs)betweenastandardfrequencyandcomparisonfrequencyshouldlinearlyincreasewiththestandardfrequencyof stimulation.Tothisend,wedeterminedJNDsatdifferentstandard frequencies(10 100Hz)wherethecomparisonfrequencywas higherthanthestandard(Fig.7a).WeobservedthatJNDshada significantlinearlyincreasingrelationshipwiththestandardfrequencyofstimulation(Fig.7b,p < 0.0001,linearregressiontest). Afterthat,wekeptthestandardasahigherfrequencyvalue (100 400Hz)anddecreasedthecomparisonfrequencyrandomly fromthatvalue(Fig.7c).Inthiscasealso,weobservedthattheJNDs forlowerfrequencycomparisonsignificantlyincreasedlinearlyas thestandardfrequencyincreased(Fig.7d,p < 0.0001,linear regressiontest).TheseresultssuggestthattheJNDruledefinedby Weber'slawholdstrueforsensorydiscriminationofSCS frequencies.

Discussion

Inthisstudy,wefoundthatrhesusmonkeysandratscanlearn todetectanddiscriminateartificialsensationsinducedbySCS followingseveraldaysofexposure.ThethresholdfordetectingSCS decreaseswithincreasingpulsewidth,frequency,anddurationof thestimulus.Wealsodocumentedtheabilityofmonkeysto discriminatesensationsthataregeneratedbystimulationpulses withvaryingfrequencyandspatiallocation.Inrats,weshowedthat thejust-noticeabledifferences(JNDs)fromaperceivablestimulus frequencywerelinearlyrelatedtotheperceivablefrequencywhen itwascomparedwithastimulusthathadeitherhigherorlower frequency.TheseresultsdemonstratedtheuniqueabilityofSCSasa noveltransmissionchanneltothebraintoencodehighlycontextualsensoryinformation.

Ourresultsonbehavioralsensitivitytodetectionofsensationin rodentsandprimateswerecomparabletothoseobservedwith IntracorticalMicrostimulation(ICMS)ofS1[5,17].Notably,sensitivitytostimulusamplitudeincreasedwithincreasingpulsewidth, frequency,anddurationofstimulation.However,longerpulses neededsignificantlyhigherchargetoreachthresholdinbothprimates(SupplementaryFig.4a,4b,and4c,p < 0.05 repeated measuresone-wayANOVA)androdents(SupplementaryFig.4d, 4e,and4f,p < 0.0001 repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA), similartothatobservedintheICMSstudy[5].ICMSamplitude usingcurrentlyFDA-approvedUTAHarraysisusuallyrestricted below~100 mAduetothepossibilityofbraintissuedamage,which limitstheamplituderangeforneuroprostheticapplicationsbetweendetectionthresholdsof20 50 mAandmaximumallowable safeamplitudeof~100 mA.InourSCSstudy,detectionthresholds hadawiderrangefrom200to800 mAatdifferentstimulation settingsandalldetectionthresholdswereconsistentlyonthenondamagingsideoftheboundarybetweendamagingandnondamagingstimulationdelineatedbyShannonequation [log(D) ¼ k log(Q),withk ¼ 1.85]onlogchargedensityversuslog chargeperphaseplot(SupplementaryFigure3a)[18].Assuminga commerciallyacceptedmaximumchargedensityof30 mC/cm2 and minimumpulse-widthof50 ms[19],itcouldbeestimatedthat maximumSCScurrentof~80mAinmonkeysand~3mAinrats couldbedeliveredusingelectrodecontacts(monkeys:0.1319cm2; rats:0.005cm2)reportedinourstudywithoutcausingtissue damage.

Frequencymodulationhasbeenhistoricallyconsidereda promisingmethodforprovidingsensoryfeedbackwithseveral studiesshowingthatanimalsarecapableofdiscriminatingICMS frequenciesandthatfrequencymodulationobeysWeber'slaw. [4,20 22],WhileICMSamplitudemodulationinmonkeysfailedto followWeber'slaw[5],experimentsinratsshowedthatmodulationofperceivedintensitybyamplitudeandpulse-widthmodulationfollowedWeber'slaw[17].Inourstudy,weinvestigated whetherratsandmonkeyscouldlearntodiscriminateSCSfrequencies.AlthoughmonkeysOandKlearnedtodiscriminate 100HzSCSfrom200Hz,aftertakingacloserlookattheirlearning curvesitwasevidentthattheydisplayeddifferentlearningbehaviorsinthefrequencydiscriminationtask(Fig.6b).MonkeyO startedatlowerdiscriminationperformanceatearliertraining sessionsbutreachedhigherlevelofperformancetowardtheendof training,whereasmonkeyK'sperformancestartedhigherthan chanceandimprovedmarginallyasthetrainingprogressed.These

detectionthresholds(normalizedbymaximumamplitudeusedintheexperimentblockofeachindividualmonkey)averagedacrossbothmonkeys(mean ± sem).Detection thresholdwerecalculatedas75%fractiondetectedatthestimulationparametersshowninpanelsa c(monkeyK)and SupplementaryFig.2 a-c(monkeyO).P-valueswere calculatedusingrepeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVA.Panelkshowsthresholddurationobtainedas75%detectionfromcurvesinpaneldasafunctionoffrequency.

Fig.4. BehavioraltasksetupandratslearnedtodetectSCSstimuli.a)Theexperimenttaskconsistedofaclosedbehavioralchamberwithtworewardportsononesideofthe chamber.Theportswerecoveredwithverticalslidingdoors.FiveratswereimplantedwithbipolarstimulationelectrodesonthedorsalsurfaceofthespinalcordattheT3spinal level.b)Taskconsistedofahouselightturning ‘on’,followedbysensorycuesfor1s.DuringthecueperiodSCSwaseitherdeliveredornotdelivered.Afterthecueperiodboth rewarddoorsopened,andtherathadtomakeanosepokeresponseineitheroftheportstoreceivewaterreward.IfSCSwasdeliveredratshadtopokeinsidetheleftportandifnot delivered,thentheyhadtopokeinsidetherightrewardport.Pokinginthecorrectrewardpokeinitiatedawaterreward,whileincorrectpokeswerenotrewarded.c)Ratslearned todetectSCSstimulioveraperiodof15 25daysasindicated learningcurveshowingtaskperformanceindicatedbyfractiontrialsdetectedasafunctionoftrainingsessions. Circlesanderrorbarsindicatemean ± sem.

differencesinlearningbehaviorcouldbeattributedtothefactthat monkeyOwasstimulatedatconstantamplitudeforbothfrequency values(100Hzand200Hz)whilemonkeyKwasstimulatedateach frequency'sthresholdamplitude.ItisquitepossiblethatmonkeyO wasdiscriminatingdifferencesinperceivedmagnitudesofthe sensoryperceptswhilemonkeyKwasdiscriminatingdifferencesin thequalitativenatureoftheperceptsinduced.Ratsarecapableof discriminatingtemporalpatternsofSCSwhenthenumberofpulses arekeptconstantbutthefrequencyofstimulusisvaried[14].In additiontothat,ourcurrentresultsindicatethatJNDsassociated withSCSfrequencydiscriminationinratsclearlyfollowWeber's lawbecauseJNDslinearlyincreasedwithstandardstimulation frequency(Fig.7band7d).Itcouldbesurmisedfrom Fig.7bthat therewereatleastthreediscriminableperceptsbetween10Hzand 200Hz; firstperceptat10Hz,secondperceptat60HzbecauseJND at10Hzwas~50Hz;andthirdperceptat180HzsinceJNDat60Hz was~120Hz.Itcanbearguedthatapplyingfrequencymodulation simultaneouslywithamplitudeandpulse-widthmodulation wouldpotentiallyincreasethenumberofdistinctdiscriminable perceptsthatarepossiblewithintheamplituderangeallowedon currentSCSelectrodes.Therefore,furtherexperimentsexploring therelationshipbetweensensorydiscriminationandfrequency, pulse-width,amplitude,anddurationofstimulationarenecessary tounderstandhowtheseparametersrelatetoperceivedintensity andqualityofsensationevokedbySCS.

AmajoradvantageofSCSisitsabilitytotargetmultipledermatomessimultaneouslywithasingleelectrodearray.Inparticular,asingle,commerciallyavailableSCSleadwithmultiple

contactscanevokesensationsinmultipledermatomessimultaneouslyduetothebilateralsensoryrepresentationoftheentire lowerbodyintheascendingdorsalcolumn fibers.Itisquite apparentfromourresultsthatmonkeyscanlearntodiscriminate thespatiallocationofthesensationsevokedbySCS(Fig.6d).This suggeststhatwecantakefulladvantageoftherostro-caudal somatotopyrepresentedinthedorsalcolumn fibersincombinationwithspatiotemporalstimulationpatternstoelectricallyinduce targetedtactileorproprioceptivesensationsinthebody.Thisview isalsosupportedbyevidencefromcomputationalstudieswhich indicatethatepiduralSCSactivatesdorsalcolumn fibersuptoa depthof0.2 0.25mmfromthedorsalsurface[23 27].However, additionalworkonminiaturizingelectrodecontactsandaccurate medio-lateral/rostro-caudalmappingofSCS-inducedsensations needstobeperformedtobeabletoelicitprecisesensations.In addition,theabilityofSCStomodulateneuronalactivityin supraspinalbrainstructuresisquitedesirablefromaneuroprostheticaswellasatherapeuticapplicationstandpoint [14,28 31,34].Amajorlimitationofourstudyistheshortexperimentaltime(SupplementaryFigure1)wehadavailableforprimates maximumof5months duetotheriskofinfection associatedwithexternalizedSCSleads.Afullyimplantablestimulationsystem,liketheoneimplantedinchronicpainpatientscould potentiallyextendourstudyindefinitelyandallowustoperform longerexperimentsinmonkeys.Nevertheless,inrodentswewere abletoperformlongerpost-implantexperimentsbecausethe electrodesandtheirwireswerefullyenclosedinsidethebody.

Fig.5. PsychophysicalevaluationofSCSsensorydetectionwithvaryingstimulationparametersinrats.OnceratslearnedtodetectSCSstimuliatthestandardparameters(frequency:100Hz,pulsewidth:200 ms,duration:1s),weallocateddifferentblocksofsessionswhere(pulsewidth & amplitude;panel ‘a’);(frequency & amplitude;panel ‘b’);and (duration & amplitude;panel ‘c’)werevariedwhilekeepingotherparametersconstant.a,b,c)Psychometriccurvesfromrepresentativeratsshowingaleftwardshiftofcurvesas thepulse-width(rat4),frequency(rat2),andduration(rat5)ofstimulationincreased.d,e,f)Psychometriccurveswithaverageddataacross fiveratsindicateleftwardshiftas pulse-width,frequency,anddurationareincreased.X-axisrepresentsrelativeamplitudevalues(foreachratrawamplitudevaluesweresubtractedbyminimumamplitudeandthe differencewasdividedbyamplitudestepsize).Circlesanderrorbarsaremean ± semacross fiverats.Curvesinpanels ‘a-f’ aresigmoidal fits.Panels ‘g’ , ‘h’,and ‘i’ indicate normalizeddetectionthresholds.Thresholdswerecalculatedas75%fractiondetectedatdifferentstimulationparametersconsistentwithpanels ‘a-f’ andthennormalizedby maximumamplitudeusedintheexperimentalblockofeachrat.Circlesanderrorbarsaremean ± semacross fiverats.P-valueswerecalculatedusingrepeatedmeasuresone-way ANOVA.

Inconclusion,wehavesuccessfullydemonstratedthatSCScan generatediscerniblesensoryperceptsinbothratsandmonkeys andalltogetherourstudystronglyshowsthepotentialofSCSto encodesensoryinformationinthebrain.Additionally,ourbehavioralexperimentsserveasatestbedforfutureanimalstudies

whichcouldelucidatetheneuralmechanismsunderlyingSCSbasedsensorydetectionanddiscrimination.WeenvisionthatSCS canbedevelopedasanartificialsensoryfeedbackchannelfor deliveringtargetedtactileandproprioceptiveinformationtothe brain.

Fig.6. MonkeyslearnedtodiscriminateSCSstimulivaryinginfrequencyandspatiallocationofelectrodes.a,b)MonkeysKandOlearnedtodiscriminateSCS stimulideliveredat thesameelectrodelocationbutvaryinginfrequency(100Hzvs200Hz).MonkeyOwasstimulatedatsameamplitudewhilemonkeyKwasstimulatedattherespectivethreshold amplitudefor100Hzand200Hz.c,d)MonkeysKandOlearnedtodiscriminatestimulationdeliveredatelectrodepair1(T6-T7spinallevel)vselectrodepair2(T7-T8spinallevel). Curvesinpanelsbanddindicatesigmoidal fitstofractioncorrecttrialsdisplayedasafunctionoftrainingdays.

Methods

AllanimalprocedureswereapprovedbytheDukeUniversity InstitutionalAnimalCareandUseCommitteeandinaccordance withNationalInstituteofHealthGuidefortheCareandUseof LaboratoryAnimals.Threeadultrhesusmacaquemonkeys(Macaca mulatta),monkeys ‘M’ , ‘O’,and ‘K’ and fiveLongEvansrats (300 350g)participatedintheexperiments.

Monkeyspinalimplantsurgery

MonkeysM,K,andOwereimplantedwith8-contactcylindrical percutaneousleads(Model3186,diameter1.4mm,contactlength 3mm,spacing4mm,AbbottLaboratories)bilaterallytothespinal mid-lineinthedorsalepiduralspaceatT6 T8spinallevel. MonkeyMhadtwoleadswith8stimulationcontactseach,monkey Ohadtwoleads,onewith8contacts(rightside)andonewith4 contacts(leftside,Model3146,similarelectrodecontactdimensionsasModel3186),andmonkeyKhadtwoleadswith8 stimulationcontactseach.Experimentalproceduresformonkeys M,O,andKlastedapproximately45,135,and150dayspostimplantafterwhichtheleadswereexplanted(Supplementary Figure1).

Implantsurgerywasperformedundergeneralanesthesiausing standardprocedurestypicalofhumanimplantation(fordetailssee supplementaryinformationand Fig.1a).Onceleadswere

implantedintheepiduralspace,asmallholewascreatedinthe skinoff-midlinetoexternalizethedistalendofthelead.Externalizedleadswereenclosedinacustomplasticcapwhichwas suturedtotheskin(Fig.1a).Theplasticcapallowedforaccesstothe leadsbytheresearcherbutprotectionfromtheanimal.Theanimal woreaprotectivevestaftersurgeryandthroughouttheexperimentalperiodwhichpreventeditsaccesstotheplasticcapsutures toitsback.

MonkeySCSdetectiontask

Monkeysweretrainedtoperformatwo-alternativeforced choicetaskwheretheywereseatedinachairfacingacomputer monitorwhichindicatedtrialprogression(Fig.1b).Oneachtriala centertargetappeared,andthemonkeyhadtomoveacursor whichwasjoystick-controlledinsidethecentertarget(Fig.1c). Afterabriefholdperiodof1sinsidethecentertarget,twotargets appearedoneithersideofthecentertarget.Eachmonkeyhadto holdthecursorinsidethecentraltargetforabriefperiodof 100 1000ms.Duringthisholdperiodsensorycueswerepresented.IfSCSwaspresented(charge-balanced,cathode-first,200 msbiphasicsquarepulsesat100Hzfor1susingcustommicrostimulator[32]),thenthemonkeyhadtomovethecursortotheleft targettoobtainajuicereward.IfSCSwasabsent,thenthemonkey hadtomovethecursorinsidetherighttarget.Attheendofthe holdperiod,thecentertargetdisappeared,thuscuingthemonkey

Fig.7. DiscriminationofhigherandlowercomparisonfrequencyobeysWeber'sLaw.a)Fractionoftrialscorrectlydiscriminatedfromstandardfrequencyof10Hz,20Hz,40Hz, 60Hz,80Hz,and100Hz,whencomparedtoarangeofhigherfrequencystimuli.c)Fractionoftrialscorrectlydiscriminatedfromstandardfrequencyof 110Hz,220Hz,310Hz, 380Hz,and400Hz,whencomparedtoarangeoflowerfrequencystimuli.Circlesanderrorbarsin ‘a’ and ‘c’ indicatemean ± sem.Curvesindicatesigmoid fitstothedata.Justnoticeabledifference(JND)isconsideredasthecomparisonfrequencyvaluethatachieves75%discriminationability.b,d)Just-noticeabledifferenceasafunctionofstandard frequencyisindicatedbyblackcirclesanderrorbars.Blacklineislinearregression fittothedataandpinkboundsindicate95%confidenceboundoftheregressionline.JNDs associatedwithhigherfrequencyandlowerfrequencycomparisonweresignificantlylinearlyrelatedwithstandardfrequency.P-valueswerecalculatedusinglinearregressiontest.

toinitiatecursormovementtowardthereward.Incorrecttarget reacheswerenotrewarded.Initiationofmovementpriortotheend oftheholdperiodterminatedthetrialwithoutrewardandablank screenwasdisplayed3sbeforestartingnexttrial.Thelearning performanceofmonkeyswasstudiedusingpercentagecorrect(PC) trials.

Monkeypsychometricevaluationofdetectionthresholds

Oncemonkeysweretrainedonthedetectiontaskandtheir performancewasabove85%,detectionthresholdsweredeterminedfordifferentelectrodecombinationsusingpsychometric testing.Particularly,during ‘StimulationON’ i.e. ‘lefttargetrewarded’ trials,thestimulationamplitudewasrandomlyvariedfrom 50 mAtoamanuallydeterminedupperlimitwhichwasbelowthe motorthreshold.Onlylefttargettrialswereanalyzedandapercentagecorrect(PC)performanceateachstimulationamplitude valuewasdetermined.Asigmoidcurvewas fittothePCvaluesand 75%wasconsideredasdetectionthreshold.Thiswasrepeatedfor severalelectrodecombinations.

Monkeyelectrodemapping

InmonkeyK,oncesensorydetectionthresholdsweredetermined,wemappedthelocationofelectrodepairstolocationonthe monkey'sbodybysedatingthemonkeyandstimulatingthose electrodesabovethesensorythresholdvalues.Areasonthebody surfacethatelicitedminormuscletwitchesorskin flutterwere marked(Fig.2c,left)andthemotorthresholdswerenoted.In monkeyO,theseobservationswerenotmadeundersedationbut whileitwasseatedintheprimatechair.

Monkeydetectionthresholdsasstimulationparametersvary

Duringsetsofconsecutivesessions,wevariedamplitudeand frequencyoramplitudeandpulse-widthoramplitudeandduration ofstimulationwhilekeepingotherparametersconstant(forstimulationparameterranges,see SupplementaryTable1).Thestandardparametersthatremainedconstantwhileotherswerevaried werefrequency:100Hz,pulsewidth:200 msec,andduration:1s.In monkeyK,wevariedfrequency(10 1000Hz)andduration (1 2000ms)ofstimulationsimultaneouslywhilekeepingpulse widthandamplitudeconstantat200 msand325 mArespectively. Detectionthresholdsforeachmonkeywerenormalizedby maximumamplitudeusedintheexperimentblockofthatmonkey beforestatisticalanalysis.

Monkeysensorydiscrimination

Inthefrequencydiscriminationtask,eachmonkeywas instructedtomovethecursorinsidethelefttargetfor100Hzand righttargetfor200Hzrespectively(Fig.6a).Inthespatial discriminationtask,themonkeywasinstructedtomovethecursor insidethelefttargetforelectrodepair1andinsiderighttargetfor electrodepair2respectively(Fig.6c).

Ratpre-trainingandSCSelectrodeimplantation

Moderatelywaterdeprivedratswereplacedinsidethebehavioralchamberfor2daystoacclimatizetothebehavioralenvironment.Thebehavioralchamberhadtwodoorsononesideofthe wallswhichenclosedwaterrewardports(Fig.4a),slightlymodified fromtheonepreviouslydescribed[33].Ratsweregraduallytrained toreceivewaterrewardfromtheports.Initially,bothrewarddoors werekeptopenandratslearnedtoreceivewaterbylickingatthe

waterdispensingspout.Later,thedoorswerekeptclosedand wouldopenafewsecondsafterthehouselightturnedon.In subsequentsessions,leftandrightdoorswouldopenonalternate trialsandratslearnedtoobtainrewardfromeachportalternatively.Thepre-surgicaltrainingperiodlastedapproximately8 10 days.

ThereaftercustomdesignedSCSelectrodes(1mm 0.5mm contactsarrangedtransverselyinabipolarconfigurationwith 0.25mmspacingusinga0.025mmthicknessplatinumfoil, GoodfellowCambridgeLimited,England)wereimplantedintothe epiduralspaceunderT3vertebraasdescribedinourprevious article[29].Aftertheratsrecoveredfromthespinalsurgicalprocedures,cathodeleadingstimulationpulsetrainsweredeliveredat theSCSelectrodesusingamulti-channelconstantcurrentstimulator(Master-8,A.M.P.I,Jerusalem,Israel)atstimulationsettings whichweredetermineddependingonthebehavioraltaskunder consideration(Fig.4a).

Ratsensorydetectiontask

Afterrecoveryfromsurgery,ratswereintroducedtoatwoalternativeforcedchoicetask(2AFC)tolearndetectionofSCS stimuliinthechamber(Fig.4b).Atthebeginningofeachtrial,a lightinthechamberwasturnedonfor1sasareminderforthe animalstopayattention.Afterthelightturnedoff,theratsreceived asensorycuefor1s.Thesensorycueeitherconsistedofcathodeleadingbipolarsquarepulsetrains(pulsewidth:200 ms,Frequency: 100Hz,duration:1s)ornostimulationpulses(interval:1s)ateach trial.Afterabriefdelayof0.5sbothrewarddoorsopened,andrats hadtorespondbychoosingtheleftdoorfor ‘SCSON’ trialsandright doorfor ‘SCSOFF’ trials.Incorrectresponseswerenotrewarded. Duringthelearningofthisbasicdetectiontask,theintensityofthe deliveredcurrentwasdeterminedbeforeeachsessionandsetusing proceduresdescribedbefore[14,29,31](mean ± std,intensityat 100Hzwas243.7 ±57 9 mA).

Ratsensorydetectionpsychophysics

Onceratslearnedthebasicsensorydetectiontaskandtheir performancewasabove80%,stimulationparameterswerevariedin asystematicmannerduringtheSCS-ONtrials.Indifferentexperimentalsessions,stimulationparameterssuchasfrequencyand amplitude,pulse-widthandamplitude,andpulsetrainduration andamplitudewerevariedwhileotherparameterswerekept constant(standardparameters:pulsewidth:200 ms;Frequency: 100Hz;duration:1s),andsensorydetectionthresholdamplitude wasdetermined(forstimulationparameterrangessee SupplementaryTable1).Foralltheconditions,thedetectablelevel oftheamplitudewasdefinedas75%accuracyofbehavioralperformance.Detectionthresholdsforeachratwerenormalizedby maximumamplitudeusedintheexperimentblockofthatrat beforestatisticalanalysis.

Ratsensorydiscriminationtask

Ina2AFCtask,ratswerepresentedwitheitheralowfrequency stimulusorahighfrequencystimulusduringthesensorycue periodinthebehavioralchamber.Foreitherfrequency,thestimuluswasdeliveredatthesameamplitude(determinedateach session),pulsewidth(200 ms),andduration(1s).Afterabriefdelay periodfollowingsensorycuepresentation,ratshadtochoosethe leftdoorforhigherfrequencystimulusandrightdoorforlower frequencystimulustoobtainreward(Fig.4a).Initially,ratswere trainedtodiscriminatebetween10Hzand100Hzfrequency. Incorrecttrailswerenotrewarded.

Weber'slawandsensorydiscrimination

Onceratslearnedtodiscriminate10Hzstimulusfrom100Hz stimulus,demonstratedbyconsistentdiscriminationperformance above80%,thelowerfrequency(standardfrequency)waskept constantduringrightdoortrialswhilethehigherfrequency (comparisonfrequency)wasrandomizedbetween20Hzand 110Hzduringleftdoortrials.Sensorydiscriminationperformance betweenastandardfrequencyandcomparisonfrequencywas determinedasthefractionoftrialssuccessfullydiscriminatedfor thatparticularstandardandcomparisonpair.Thus,fractiontrials discriminatedwasplottedasafunctionofcomparisonfrequencyto obtainJust-NoticeableDifferences(JNDs)determinedas75%value onthecurve.Thesameexperimentwasrepeatedfordifferent standardfrequencyvaluessuchas20Hzvs(40 220Hz),40Hzvs (60 240Hz),60Hzvs(85 310Hz),80Hzvs(110 380Hz),and 100Hzvs(130 400Hz)toobtainJNDsforeachstandardfrequency valueandtotestforWeber'slaw.

Similarly,theexperimentwasrepeatedfordiscriminationofa low-frequencycomparisonstimulusfromahigh-frequencystandardstimulus.Thestandardfrequencyvalueswere110,220,310, 380,and400Hz,whilethecomparisonfrequencywasrandomized from(100 10Hz),(200 20Hz),(285 60Hz),(350 80Hz),and (370 100Hz)respectivelyforeachofthestandardfrequency values.JNDswerecalculatedforeachofthestandardfrequency valuesasexplainedbeforetotestforWeber'slaw.

Statisticalanalysis

Repeatedmeasuresone-wayANOVAwasusedtotestthesignificanceofrelationshipbetweenstimulationparametersand sensorydetectionthresholdsinbothratsandmonkeys(Fig.3h,3i, 3j,5g,5h,5i,and SupplementaryFig.4cand4f).Totestwhether JNDsweresignificantlylinearlyrelatedtostandardfrequencyinthe sensorydiscriminationtask,thelinearregressiontestwasused (Fig.7band7d).

CRediTauthorshipcontributionstatement

AmolP.Yadav: Conceptualization,Methodology,Software, Investigation,Formalanalysis,Fundingacquisition,Supervision, Writing originaldraft,Writing review & editing. ShuangyanLi: Methodology,Investigation,Formalanalysis,Writing review & editing. MaxO.Krucoff: Conceptualization,Methodology,Funding acquisition,Writing review & editing. MikhailA.Lebedev: Conceptualization,Writing review & editing. MuhammadM. Abd-El-Barr: Methodology,Writing review & editing. Miguel A.L.Nicolelis: Resources,Fundingacquisition,Supervision,Writing review & editing.

Declarationofcompetinginterest

Theauthorsdeclarenocompeting financialornon-financial interests.

Acknowledgements

WethankGaryLehewforassistancewithexperimentalsetup, TamaraPhillipsforassistancewithmonkeyhandling,Paul Thompsonforassistancewithprimatetasksoftware,LauraOliveira andSusanHalkiotisfortechnicalassistance,andJosephO'Doherty forcommentsonpreviousversionofmanuscript.Thisresearchwas supportedbyDukeInstituteforBrainSciencesGerminatorAward andDukeNeurosurgeryResearchSupportawardedtoAmolP. Yadav,NIHR25awardedtoMaxO.Krucoff,RSFgrant21-75-30024

awardedtoMikhailA.Lebedev,andHartwellFoundationgrant awardedtoMiguelNicolelis.

AppendixA.Supplementarydata

Supplementarydatatothisarticlecanbefoundonlineat https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.04.024

References

[1]LebedevMA,NicolelisMA.Brain-Machineinterfaces:frombasicscienceto neuroprosthesesandneurorehabilitation.PhysiolRev2017;97(2):767 837. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00027.2016.PubMedPMID:28275048.

[2]KrucoffMO,RahimpourS,SlutzkyMW,EdgertonVR,TurnerDA.Enhancing nervoussystemrecoverythroughneurobiologics,neuralinterfacetraining, andneurorehabilitation.ARTN584FrontNeurosci2016;10. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnins.2016.00584.PubMedPMID:WOS:000390598100001.

[3]BensmaiaSJ,MillerLE.Restoringsensorimotorfunctionthroughintracortical interfaces:progressandloomingchallenges.NatRevNeurosci2014;15(5): 313 25. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3724.PubMedPMID:24739786.

[4]O'DohertyJE,LebedevMA,IfftPJ,ZhuangKZ,ShokurS,BleulerH,NicolelisMA. Activetactileexplorationusingabrain-machine-braininterface.Nature 2011;479(7372):228 31. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10489.PubMed PMID:21976021;PMCID:3236080.

[5]KimS,CallierT,TabotGA,GauntRA,TenoreFV,BensmaiaSJ.Behavioral assessmentofsensitivitytointracorticalmicrostimulationofprimatesomatosensorycortex.49.In:ProceedingsofthenationalacademyofSciencesof theUnitedStatesofAmerica.vol.112;2015.p.15202 7. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1509265112.PubMedPMID:26504211;PMCID:4679002.

[6]TabotGA,DammannJF,BergJA,TenoreFV,BobackJL,VogelsteinRJ, BensmaiaSJ.Restoringthesenseoftouchwithaprosthetichandthrougha braininterface.PNatlAcadSciUSA2013;110(45):18279 84. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1221113110.PubMedPMID:WOS:000326550800062.

[7]FlesherSN,CollingerJL,FoldesST,WeissJM,DowneyJE,Tyler-KabaraEC, BensmaiaSJ,SchwartzAB,BoningerML,GauntRA.Intracorticalmicrostimulationofhumansomatosensorycortex.Epub2016/11/01SciTranslMed 2016;8(361):361ra141. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8083 PubMedPMID:27738096.

[8]HemingE,SandenA,KissZH.Designingasomatosensoryneuralprosthesis: perceptsevokedbydifferentpatternsofthalamicstimulation.JNeuralEng 2010;7(6):064001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2560/7/6/064001 .PubMed PMID:21084731.

[9]SwanBD,GaspersonLB,KrucoffMO,GrillWM,TurnerDA.Sensorypercepts inducedbymicrowirearrayandDBSmicrostimulationinhumansensory thalamus.BrainStimul2018;11(2):416 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.brs.2017.10.017.PubMedPMID:29126946;PMCID:PMC5803348.

[10]DadarlatMC,O'DohertyJE,SabesPN.Alearning-basedapproachtoartificial sensoryfeedbackleadstooptimalintegration.Epub2014/11/25NatNeurosci 2015;18(1):138 44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3883.PubMedPMID: 25420067;PMCID:PMC4282864.

[11]StraussI,ValleG,ArtoniF,D'AnnaE,GranataG,DiIorioR,GuiraudD, StieglitzT,RossiniPM,RaspopovicS,PetriniFM,MiceraS.Characterizationof multi-channelintraneuralstimulationintransradialamputees.Epub2019/12/ 19SciRep2019;9(1):19258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55591-z . PubMedPMID:31848384;PMCID:PMC6917705.

[12]PetriniFM,ValleG,BumbasirevicM,BarberiF,BortolottiD,CvancaraP, HiairrassaryA,MijovicP,SverrissonAO,PedrocchiA,DivouxJL,PopovicI, LechlerK,MijovicB,GuiraudD,StieglitzT,AlexanderssonA,MiceraS,LesicA, RaspopovicS.Enhancingfunctionalabilitiesandcognitiveintegrationofthe lowerlimbprosthesis.Epub2019/10/04SciTranslMed2019;11(512). https:// doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aav8939.PubMedPMID:31578244.

[13]PetriniFM,BumbasirevicM,ValleG,IlicV,MijovicP,CvancaraP,BarberiF, KaticN,BortolottiD,AndreuD,LechlerK,LesicA,MazicS,MijovicB, GuiraudD,StieglitzT,AlexanderssonA,MiceraS,RaspopovicS.Sensory feedbackrestorationinlegamputeesimproveswalkingspeed,metaboliccost andphantompain.Epub2019/09/11NatMed2019;25(9):1356 63. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0567-3.PubMedPMID:31501600.

[14]YadavAP,LiD,NicolelisMAL.Abraintospineinterfacefortransferring artificialsensoryinformation.Epub2020/01/23SciRep2020;10(1):900. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57617-3 .PubMedPMID:31964948.

[15]BellancaRU,LeeGH,VogelK,AhrensJ,KroekerR,ThomJP,WorleinJM. Asimplealopeciascoringsystemforuseincolonymanagementoflaboratoryhousedprimates.Epub2014/02/28JMedPrimatol2014;43(3):153 61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmp.12107.PubMedPMID:24571509;PMCID: PMC4438708.

[16]EkmanG.Weberlawandrelatedfunctions.JPsychol1959;47(2):343 52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1959.9916336 .PubMedPMID:WOS: A1959CAK1200020.

[17]BjanesDA,MoritzCT.Arobustencodingschemefordeliveringartificial sensoryinformationviadirectbrainstimulation.Epub2019/08/24IEEETrans NeuralSystRehabilEng2019;27(10):1994 2004. https://doi.org/10.1109/ TNSRE.2019.2936739.PubMedPMID:31443035.

[18]MerrillDR,BiksonM,JefferysJG.Electricalstimulationofexcitabletissue: designofefficaciousandsafeprotocols.Epub2005/01/22JNeurosciMethods 2005;141(2):171 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.020 PubMedPMID:15661300.

[19]CoganSF,LudwigKA,WelleCG,TakmakovP.Tissuedamagethresholds duringtherapeuticelectricalstimulation.Epub2016/01/23JNeuralEng 2016;13(2):021001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2560/13/2/021001 PubMedPMID:26792176;PMCID:PMC5386002.

[20] RomoR,HernandezA,ZainosA,BrodyCD,LemusL.Sensingwithout touching:psychophysicalperformancebasedoncorticalmicrostimulation. Neuron2000;26(1):273 8.PubMedPMID:10798410

[21]O'DohertyJE,ShokurS,MedinaLE,LebedevMA,NicolelisMAL.Creatinga neuroprosthesisforactivetactileexplorationoftextures.43.In:Proceedings ofthenationalacademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica.vol.116; 2019.p.21821 7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908008116 .Epub2019/10/ 09,PubMedPMID:31591224;PMCID:PMC6815176.

[22]CallierT,BrantlyNW,CaravelliA,BensmaiaSJ.Thefrequencyofcortical microstimulationshapesartificialtouch.2.In:Proceedingsofthenational academyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica.vol.117;2020. p.1191 200. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916453117 .Epub2019/12/28, PubMedPMID:31879342;PMCID:PMC6969512.

[23]HolsheimerJ,BarolatG.Spinalgeometryandparesthesiacoverageinspinal cordstimulation.Neuromodulation:J.Int.Neuromod.Soc.1998;1(3): 129 36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.1998.tb00006.x.PubMedPMID: 22150980.

[24]BarolatG,MassaroF,HeJ,ZemeS,KetcikB.Mappingofsensoryresponsesto epiduralstimulationoftheintraspinalneuralstructuresinman.Epub1993/ 02/01JNeurosurg1993;78(2):233 9. https://doi.org/10.3171/ jns.1993.78.2.0233.PubMedPMID:8421206.

[25]HolsheimerJ,BuitenwegJR.Review:bioelectricalmechanismsinspinalcord stimulation.discussion70Neuromodulation:J.Int.Neuromod.Soc. 2015;18(3):161 70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12279 .PubMedPMID: 25832787.

[26]NorthRB,SierackiJM,FowlerKR,AlvarezB,CutchisPN.Patient-interactive, microprocessor-controlledneurologicalstimulationsystem.Epub1998/10/01

Neuromodulation:J.Int.Neuromod.Soc.1998;1(4):185 93. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1525-1403.1998.tb00015.x .PubMedPMID:22151030.

[27]HolsheimerJ.Whichneuronalelementsareactivateddirectlybyspinalcord stimulation.Epub2002/01/01Neuromodulation:J.Int.Neuromod.Soc. 2002;5(1):25 31. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1403.2002._2005.x .PubMed PMID:22151778.

[28]YadavAP,NicolelisMAL.Electricalstimulationofthedorsalcolumnsofthe spinalcordforParkinson'sdisease.MovDisord2017;32(6):820 32. https:// doi.org/10.1002/mds.27033.PubMedPMID:28497877.

[29]YadavAP,FuentesR,ZhangH,VinholoT,WangCH,FreireMA,NicolelisMA. Chronicspinalcordelectricalstimulationprotectsagainst6hydroxydopaminelesions.SciRep2014;4:3839. https://doi.org/10.1038/ srep03839.PubMedPMID:24452435;PMCID:3899601.

[30] YadavAP,BordaE,NicolelisMA.Closedloopspinalcordstimulationrestores locomotionanddesynchronizescorticostriatalbetaoscillations[abstract]. MovDisord2018;33

[31]Pais-VieiraM,YadavAP,MoreiraD,GuggenmosD,SantosA,LebedevM, NicolelisMA.Aclosedloopbrain-machineinterfaceforepilepsycontrolusing dorsalcolumnelectricalstimulation.SciRep2016;6:32814. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/srep32814.PubMedPMID:27605389;PMCID:PMC5015048.

[32]HansonTL,OmarssonB,O'DohertyJE,PeikonID,LebedevMA,NicolelisMA. High-sidedigitallycurrentcontrolledbiphasicbipolarmicrostimulator.Epub 2012/02/14IEEETransNeuralSystRehabilEng2012;20(3):331 40. https:// doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2187219.PubMedPMID:22328184;PMCID: PMC3502026.

[33]Pais-VieiraM,ChiuffaG,LebedevM,YadavA,NicolelisMA.Buildingan organiccomputingdevicewithmultipleinterconnectedbrains.SciRep 2015;5:11869. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11869.PubMedPMID:26158615; PMCID:4497302.

[34]RahimpourS,GaztanagaW,YadavAP,ChangSJ,KrucoffMO,CajigasI,etal. FreezingofGaitinParkinson’sDisease:InvasiveandNoninvasiveNeuromodulation.Neuromodulation:TechnolNeuralInterfac2020. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/ner.13347.PubmedPMID:33368872.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd: