Pension incentives and labor supply: Evidence from the introduction of universal old-age assistance in the UK Matthias Giesecke & Philipp Jäger

https://ebookmass.com/product/pension-incentivesand-labor-supply-evidence-from-the-introductionof-universal-old-age-assistance-in-the-ukmatthias-giesecke-philipp-jager/ Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

A theological introduction to the Old Testament

Hamilton

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-theological-introduction-to-theold-testament-hamilton/

Hearing the Scriptures: Liturgical Exegesis of the Old Testament in Byzantine Orthodox Hymnography Eugen J. Pentiuc

https://ebookmass.com/product/hearing-the-scriptures-liturgicalexegesis-of-the-old-testament-in-byzantine-orthodox-hymnographyeugen-j-pentiuc/

Sexual Harassment in the UK Parliament: Lessons from the #MeToo Era Christina Julios

https://ebookmass.com/product/sexual-harassment-in-the-ukparliament-lessons-from-the-metoo-era-christina-julios/

New Development Assistance: Emerging Economies and the New Landscape of Development Assistance 1st ed. Edition Yijia Jing

https://ebookmass.com/product/new-development-assistanceemerging-economies-and-the-new-landscape-of-developmentassistance-1st-ed-edition-yijia-jing/

Sonny: The Last of the Old Time Mafia Bosses, John "Sonny" Franzese S. J. Peddie

https://ebookmass.com/product/sonny-the-last-of-the-old-timemafia-bosses-john-sonny-franzese-s-j-peddie/

Religion in the Age of Re-Globalization: A Brief

Introduction Roland Benedikter

https://ebookmass.com/product/religion-in-the-age-of-reglobalization-a-brief-introduction-roland-benedikter/

The International Bureau of Education (1925-1968): "The Ascent From the Individual to the Universal" Rita Hofstetter

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-international-bureau-ofeducation-1925-1968-the-ascent-from-the-individual-to-theuniversal-rita-hofstetter/

Employment and Labor Law 10th Edition Patrick J. Cihon

https://ebookmass.com/product/employment-and-labor-law-10thedition-patrick-j-cihon/

Labor Economics (9th Edition) George J. Borjas

https://ebookmass.com/product/labor-economics-9th-edition-georgej-borjas/

JournalofPublicEconomics203(2021)104516

Contentslistsavailableat ScienceDirect JournalofPublicEconomics

journalhomepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/jpube

Pensionincentivesandlaborsupply:Evidencefromtheintroduction ofuniversalold-ageassistanceintheUK q

MatthiasGiesecke a,1,PhilippJäger b,2,⇑ a FederalMinistryofFinance,RWIandIZA,Germany b RWI,Germany

articleinfo

Articlehistory: Received2December2020

Revised3September2021

Accepted8September2021

Availableonline9October2021

JEL-Classification: D61 H21 H55 J14

J22

J26

Keywords: Old-AgeAssistance LaborSupply Retirement RegressionDiscontinuityDesign

abstract

WestudythelaborsupplyimplicationsoftheOld-AgePensionAct(OPA)of1908,which,forthefirst time,providedpensionstoolderpeopleintheUK.Usingrecentlyreleasedcensusdatacoveringtheentire population,weexploitvariationatthenewlycreatedage-basedeligibilitythreshold.Ourresultsshowa considerableandabruptdeclineinlaborforceparticipationof6.0percentagepoints(13%)whenolder workersreachtheeligibilityageof70.Tomitigatetheimpactofpopulationagingtoday,pensionreforms aimedatincreasingelderlylaborsupply,however,havetoinducemuchlargerbehavioralresponsesthan theOPA.

2021ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

1.Introduction

Manypensionprogramsintendtopreventpovertythrough means-testedincometransferstotheelderly.Alargebodyofliteraturehasdocumentedthatlaborsupplyrespondstomarginal changesinexistingpensionschemes.Littleisknown,however, onthelaborsupplyeffectsofintroducinguniversalold-ageassistanceprogramsforthefirsttime.

ThisarticleassessesthelaborsupplyimplicationsoftheOldAgePensionAct(OPA)of1908thatestablisheduniversalmeans-

q WethankJeffreyClemens(theEditor)andthreeanonymousrefereesfortheir helpfulsuggestionsthatimprovedthepapersubstantially.Wearegratefulto RonaldBachmann,StefanBauernschuster,SebastianBraun,DavidCard,Fabian Dehos,ErikHornung,RobinJessen,AnicaKramer,ChristianProano,LauraSalisbury, HanYeandtheparticipantsofseveralconferencesandseminarsforvaluable commentsandinsightfuldiscussions.JohannaMuffertprovidedexcellentresearch assistance.Allcorrespondencetophilipp.jaeger@rwi-essen.de.

⇑ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress: philipp.jaeger@rwi-essen.de (P.Jäger).

1 FederalMinistryofFinance,Berlin,Germany

2 RWI–Leibniz-InstituteforEconomicResearch,Essen,Germany.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104516

0047-2727/ 2021ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

testedpensionsintheUKattheexpenseofhighertaxesfortop incomeearners.Incontrasttomostoftheexistingliterature,the uniquehistoricalsettingallowsustoestimatethelaborsupply responsewhenmovingfromessentiallynoprogramtoanoldageassistanceschemethatcoveredalargeshareoftheelderly population.3 Usingrecentlyreleasedfull-countpopulationdatafrom theUKcensusin1911,weisolatethecausaleffectoftheprogram alongthelinesofanage-basedeligibilitythresholdthathasbeen introducedbytheOPAattheageof70.4 Thisthresholdinducesadiscontinuityintheretirementprobabilitythatweusetoidentify changesinthelaborforceparticipation(LFP)ratebyadoptinga regressiondiscontinuity(RD)design.

Thehistoricalsetting,besidesbeinginterestinginitsownright, alsoinvolvesseveralotherfeaturesthatstrengthentheempirical

3 In1911,57.5%ofpeoplewhoreachedtheeligibilityageof70didreceivea pensionthatwasadministeredthroughtheOPA.

4 Despitethelowexpectancyatbirth,theUKhadasizableelderlypopulationat thattime(morethanonemillionpeoplewere70andolderinEnglandandWales alone).Conditionalonhavingcelebratedthe70thbirthday,thiscohorthada remaininglifetimeof9yearsonaverage.

M.GieseckeandP.Jäger JournalofPublicEconomics203(2021)104516

analysis.Enactedin1908andeffectivelyimplementedin1909,the OPAwasthelargestmeans-testedold-ageassistanceprogramat thattime5 andservedasanarchetypeforpublicold-ageassistance intheUS.6 AlthoughtheUKwasalargeindustrializedeconomy whentheOPAwasintroduced,itstilllackedacomprehensivewelfaresystem.Privatepensionschemesandothergovernmentprogramsthataddressedolderworkerswereeithersmalland uncommonordidnotexist.Furthermore,programsubstitution towardsunemploymentorhealthinsurancewasimpossiblebecause theseprogramsbecameeffectivein1912/1913andthusafterthe implementationoftheOPA(1909)anddatacollection(1911).

Previousstudieshavesuggestedthattheintroductionofthe OPAhadlittleimpactonlaborsupply(Johnson,1994;Costa, 1998).Thisconjectureisbasedonaggregatelaborforceparticipation(LFP)ratesfromBritishcensuses,suggestingthatthedownwardtrendinLFPratesamongoldermenintheUKdidnot accelerateaftertheintroductionoftheOPA.Usingmoredisaggregateddata,weprovideevidencethatLFPratesofoldermenand womendiddeclinepromptlyandconsiderablyasadirectconsequenceoftheintroductionoftheOPA.

Ourmainfindingsindicatethat,inabsoluteterms,theLFP declineamountsto6.0percentagepointsattheageof70justafter theimplementationoftheOPA.Relativetoaparticipationrateof 46%atage69,theLFPratethusdeclinesby13%whenmovingmarginallyabovetheage-basedeligibilitythreshold.TheLFPdropis predominantlydrivenbyreductionsinworkactivityandmuchless bylowerunemployment.Ourestimatesareconsistentwithsubstitutioneffectsandconstrainedincomeeffects.Themeanstestputs animplicittaxonlaborearnings(i.e.substitutioneffect),which makeslabor(relativetoleisure)lessattractiveandresultsinretirementbunchingatage70.Atthesametime,liquidityconstraints, myopicbehavior,oruncertaintyaboutfuturepensionpolicies mightpreventthatthetransfercomponentofthepension(i.e. incomeeffect)leadstoretirementpriortotheeligibilityage.These marketimperfectionsareplausibleexplanationsforincomeeffects thatmaterializeonlyasadiscretedownwardjumpoflaborsupply attheeligibilityage(andnotbefore).

Laborsupplyresponsesareconsiderablylargerforpeoplein low-earningsoccupationscomparedtohigh-earningsoccupations. WedocumentthattheLFPreductionof15.3%inthelowestoccupationalearningsquartilemorethandoublestheLFPdeclineof 7.2%inthehighestquartile.Thisfindingisconsistentwiththetheoreticalpredictionthatpeoplewithlowearningsshouldrespond morestronglytomeans-testedcashtransfersbecausetheyhave toforgolessearningstopassthemeanstestthanpeoplewithhigh earnings.OurresultsalsoindicatethattheLFPdeclineissmaller forolderworkerswithclosefamilytiesincomparisontoindividualswithout.Thisfindingisinlinewiththehypothesisthatprivate transfersfromchildren,spouses,orotherhouseholdmembers servedasold-ageinsurancewhenpublicpensionswereabsent. Wefurtherprovideevidenceforjointretirementdecisionsofcouples.WedocumentasignificantLFPdropof3.3percentagepoints amongeligiblemenwhentheirspousealsoreachestheeligibility age.

5 Germanyalreadyintroducedapublicpensionschemein1891,butpensionswere basedoncontributionsandnotmeans-tested.Belgium,France,Denmark,New ZealandandpartsofAustraliahadmeans-testedold-ageassistanceprogramsinplace before1909.However,theseprogramsweresmallerwithrespecttotheabsolute numberofrecipientsorthebenefitlevel.

6 AftertheintroductionoftheOPA,publicpensions,whichyetdidnotexistexcept forveterans,alsomadetheagendainseveralUSstates ChamberlainandPierson (1924).Mostofthefollowingpensionlegislationwasbasedonaprovisionknownas ”thestandardbill” BureauofLaborStatistics(1929) whichwasremarkablysimilarto theOPAandencompassedmeans-tested,non-contributorypensionsstartingwiththe ageof70.

TheOPAwasmostlikelywelfareenhancing,despitetheclear laborsupplydecline.TheOPAgeneratedonlymodestefficiency losses,becausethebehavioralresponsestothepensionswere moderaterelativetothescaleoftheprogram.Moreoverfiscal externalitiesweresmallbecauseofthelowtaxratesandlimited othersocialspendingatthetime.Incontrast,thedegreeofredistribution,andhencetheequitygain,wasimmense.Thepolicy redistributedfromtheabsolutetoptothebottomoftheearnings distributioninatimeofhighincomeinequality.7

Thispaperaddstoearlierstudiesonlaborsupplyresponsesto pensionreforms.Theliteraturehasmostlyfocusedonmarginal changesinexistingpensionsystems(e.g. KruegerandPischke, 1992;Börsch-Supan,2000;Mastrobuoni,2009;Liebmanetal., 2009;Brown,2013;Danzer,2013;AtalayandBarrett,2015; ManoliandWeber,2016).Weextendthisstrandoftheliterature bystudyingafirst-timeintroductionofanold-ageassistancesystem,thusinvestigatingthechangefromnoprogramtouniversal coverage.Ourestimatesquantifytheimmediatelaborsupply effectsoftheOPA,startingfromabenefitlevelofzerowithouthavingtorelyonextrapolations.Suchestimatesareinformativefor theintroductionofold-ageassistancesystemsintoday’sdevelopingcountriesandalsoserveasabenchmarkformarginalchanges incontemporaneouspensionprograms.Asimpleback-of-theenvelopecalculationrevealsthatfuturepensionreformsthataim tostabilizetheretiree-to-workerratiohavetoinducemuchlarger behavioralresponsesthantheOPA.

Theonlyexistingevidenceonthelaborsupplyeffectsofintroducingpublicpensionsforthefirsttimestemsfromstudiesonthe USSocialSecurityActof1935(Parsons,1991;Friedberg,1999; FetterandLockwood,2018).IncontrasttotheUSprogramthat wasintroducedduringtheturbulenttimesoftheGreatDepression, old-ageassistanceintheUKwasestablishedinaperiodofstable economicconditionswhichensuresthatourresultsarenotconfoundedbymacroeconomicshocksorthemassiveexpansionof othersocialspending.Moreover,theinstitutionalsettinginthe UKallowsforhighlycredibleandtransparentidentificationbased solelyonanageRD.Ourresearchdesignbuildsonmanyrecent studiesthathaveusedage-basedeligibilitythresholdstoidentify policy-relevanteffects(seee.g. Cardetal.,2008;Battistinetal., 2009;CarpenterandDobkin,2009;Cardetal.,2009;Anderson etal.,2012,2014;CarpenterandDobkin,2015,2017;Fitzpatrick andMoore,2018).

Theremainderofthispaperisstructuredasfollows.Section 2 provideshistoricalandinstitutionaldetailsontheold-ageassistanceprogramintheUKandhowitsintroductioncreatesexogenousvariationthatweuseforidentification.Section 3 outlines theresearchdesignanddescribesthedata.Section 4 presents results,sensitivitychecksandfalsificationtests.Section 5 discussesmechanisms,welfareimplicationsandpolicyimplications oftheprogram.Section 6 concludes.

2.HistoricalBackgroundandInstitutionalDetails

TheOld-AgePensionActof1908(OPA)introducedmeanstested,non-contributoryminimumpensionsforBritishcitizens financedbythecentralgovernment.TheOPAwasamajorsocial policyinterventionandthefirstonetospecificallytargetthe elderlyinatimeofverylimitedsocialprotection.Thelawwas debatedintheBritishParliamentinMay1908,passedthroughin August1908andthefirstpensionswereeventuallypaidoutinJanuary1909.Atthattime,neitherunemploymentnorhealthinsur-

7 In1911,8.4%oftotalincome(beforetaxes)intheUKwenttothetop0.05% comparedto3.4%in2000(Atkinson,2007).

anceexistedbecausebothoftheseprogramsonlybecameeffective in1912/1913.

Giventhatpensionsweremeans-tested,thecoverageofthe OPAwasastonishinglyhigh.In1911,almost60%ofpeoplewho hadreachedtheeligibilityageweregrantedapensioninEngland andWales(613,873outof1,068,486accordingtothe Department ofLabourStatistics,1915 p.184).Thevastmajorityofpension recipients(about93%in1911)receivedthemaximumpensionof 5 shillings perweek.Accordingto Feinstein(1990),thisamounted toapproximately22%ofaverageearningsatthetime.

TheOPAwasaresponsetotheperceivedinadequacyofthe existingpoorreliefsystemthatprovidedonlyverybasicprotection andinvolvedconsiderablesanctions(includingthelossofvoting rights)andsocialstigmaaswellastherequirementtoworkina workhouseunlessthepersoncouldprovetobesufficientlyunfit. Thenewlyintroducedpensionswerenotonlylessrestrictivebut alsoinvolvedmoregenerousbenefitsandthusconsiderablymore olderpeopleappliedforthem.8 Incontrasttothepoorlaw,which wasadministeredandfinancedatthelocallevelgivinglocalauthoritiesalotofdiscretionintheassignmentoffinancialaid,theOPA wasenactedasanation-widerightforolderworkerswhometthe specifiedpensioneligibilitycriteria.Theintroductionofthepension reducedthenumberofpoorreliefrecipientsamongtheelderlysubstantially,however,ithadnoapparenteffectonpoorreliefsupport forpeoplebelowage70.9

Toreducesocialstigma,peoplecouldapplyforpensionsatthe localpostoffice.Decisionsweremadebyapensionofficer appointedbythetreasuryandalocalpensioncommittee.Pension eligibilitywasmainlybasedontwocriteria:ageandinadequate means.10

Olderworkersonlybecameeligiblewhenreachingtheageof 70.Theoriginalproposalforthereform,datingbackto1899,recommendedaretirementageof65,whichwouldhavebeenmorein linewiththeretirementrulesinthefewpre-existingpension schemesthattypicallyspecifiedanagebetween60and65.11 However,theoriginalsuggestionwasconsideredtooexpensive.Proving

agewasstraightforwardforpensionclaimantsinEnglandandWales becausebirthregisters(andthusbirthcertificates)existedatleast since1837.VerificationwasmoredifficultinScotlandandespecially challenginginIreland,makingrejectionsbasedontheagecriterion farmorefrequentinIreland(OldAgePensionsCommittee,1919). Giventhelowlifeexpectancyatbirth(below50formalesin 1911),aretirementageof70seemshighbytoday’sstandards.The lowlifeexpectancy,however,wasmainlydrivenbyhighinfantmortality.Oncereachingtheageof70in1911(birthcohort1841),peoplecouldexpecttoliveanother9yearsonaverage(men:8.5yrs., women:9.5yrs. HumanMortalityDatabase,2018).

Eligibilitywasalsoconditionalonameanstest.Claimantshad toprovethattheirannualmeanswerebelow630 shillings (54% ofaverageannualearningsatthattime)toreceiveanypension. Tobecomeeligibleforthemaximumpension,anincomeofless than420 shillings (36%ofaverageannualearnings)wasrequired.12 Meanswerecalculatedbasedonlaborincome,familytransfersas wellasreturnsonproperty,includinghypotheticalreturnsandthe rentalvalueoflivinginone’sownhouse.Spousalincomewasalso consideredexplicitly.13 Thelawalsoprescribedthatifindividuals intentionallydeprivedthemselvesofresources,thevalueofthese resourceswouldstillbeincludedinthecalculationoftheannual means.However,oneshouldnotoverestimatethestrictnessofthe meanstest,sincemeansweretypicallyself-reported.14 Moreover, thelocalpensioncommittees–themostimportantdecisionmaking authority–wereinclinedtogenerosity(Pugh,2002)andthusmost applications(around90%)wereapproved(Times,1909;OldAge PensionsCommittee,1919)15 andonly3.5%ofpensiondecisions wereappealedin1913(Pugh,2002).

8 In1906,23.3%ofpeopleaged70+inEnglandreceivedsomeformofpoorrelief (Boyer,2016,Table13)comparedto57.5%ofpeople70+thatreceivedapensionin EnglandandWalesin1911.Incontrasttothepension,poorreliefwasoftentiedtoa residenceinaworkhouse.Forinstance,in1908,morethan60%ofelderlypoorrelief recipientsinLondonwererelievedinworkhouses(Boyer,2016,Table7).Forpeople thatwererelievedoutsideofworkhouses,thepoorreliefpaymentsweretypically muchsmallerthanthenewlyintroducedpension.Accordingto Pugh(2002),weekly poorreliefwasonaverage2 shillings and6 pence andhenceonly50%ofthepension.

9 Neitherspendingperpoorreliefrecipientnorthenumberofpoorreliefrecipients belowtheageof70appeartobesubstantiallyaffectedbytheOPA.Accordingto DepartmentofLabourStatistics(1913,p.328-329),meanannualexpenditureper personinreceiptofpoorrelief(outsideofaworkhouse)hasincreasedbylessthan3% from1908to1912(from£7and1 shilling to£7and5 shillings).Atthesametime,the totalnumberofpeoplereceivingpoorreliefinEnglandandWalesdeclinedby 121,720(from772,346to650,626).Thedeclinealmostperfectlymatchesthenumber ofpeopleformerlyrelyingonpoorreliefthatbecameoldage-pensionersinthesame timeperiod(122,415).Moreover,theshareofable-bodiedpoorreliefrecipients relativetothetotalpopulation,whichcanserveasaproxyforyoungpoorrelief recipients,remainedconstant.

10 Moreover,thelawincludedaresidencyrequirementof20years.Iftheclaimant hadsatisfiedallofthetheeligibilitycriteria,heorshecouldstillbedisqualifieddueto thefollowingreasons.First,receivingpoorrelieforhavingreceivedpoorreliefany timebetweenJanuary1908andDecember1910.Second,habituallyfailingtowork accordingtohis/herability.Andthird,beingdetainedinalunaticasylum,orinany placeasarecipientofpoorrelieforacriminallunaticorbeinginjail(ororderedtobe imprisoned)lessthantenyearsago.

11 Small-sizedpensionschemeswithintheboundariesoftherespectivefirmexisted previoustothelarge-scaleintroductionoftheOPA.However,thesepensionswere ratherinformalanddiscretionary.Moreformalizedschemesonlyexistedinveryfew largerfirms,forexampleintherailwayindustry,orthepublicsector.Byfar,these pensionsdidnotreachtheuniversalcoverageratethatwasintroducedthroughthe OPA(see Thane,2000,fordetailsonpre-existingpensionsintheUK).

Thegovernmentexpensesforthepensionwerethereforeconsiderable,despitetherelativelyhighretirementage.Inthebudget year1911,£6.3millionwerespentonold-agepensionsinEngland andWales.FortheentireUK,old-agepensionexpenditures amountedto£9.8million,makingpensionsoneofthelargestsinglespendingitem(5.7%ofoverallexpendituresinthebudgetof 1911, HouseofCommons,1911).Pensionswerefinancedalmost exclusivelybytaxesonhighincomeearners(roughlythetop1% intheUK).16 Forthispurpose,newprogressivetaxbracketswere introduced(HouseofCommons,1911):Themarginaltaxratefor peoplewithannualearningsof£2,000-£3,000increasedbyaround 1.2percentagepoints(to5.0%),for£3,000-£5,000byaround2percentagepoints(to5.8%)andabove£5,00017 byaround4.5percentagepoints(to8.3%).Themarginaltaxrateforthemajorityoftax payersearningbetween£160and£2000wasnotincreasedand remainedat3.8%.18 Mostpeopledidnotpayanyincometaxbecause

12 Intheory,pensionsweregrantedbasedonaglidingscaleasdepictedinOnline AppendixFig.B.1(Abramitzkyetal.,2014;DiamondandSaez,2011;Finkelstein, 2019;Hendren,2020;Spender,1892).However,theoverwhelmingmajority(93%in 1911)receivedthemaximumpensionof260 shillings peryear.

13 Spouseslivingtogetherinonehouseholdhadtofulfilltwocriteria:(1)Theirown incomeand(2)theperpersonincomeofthecouplehadtofallbelowthethreshold. Anexampleprovidedin Casson(1908) clarifiesthisrule:imagineamarriedcouple. Themanearns800 shillings andthewoman200 shillings.Inthiscase,thewoman wouldbeeligibleforapensionandhastoclaimanincomeof500 shillings ((800+200)/2).Theman,however,wouldnotbeeligibleashisownincomeof800 shillings exceedsthethreshold.

14 Newspaperarticlessuggestthatfraudulentclaimsbasedonmisreportedmeans, however,wereindeed(atleastsometimes)legallyprosecuted,indicatingthatthe meanstestwasnotsimplyapapertiger.

15 Themainreasonsfordisapprovalweretheinabilitytoprovetheindividualage (mostrelevantinIreland),afailedmeanstestorreceivingpoorrelief.

16 Otherlessimportantcomponentsofthefinancingsystemweredeathdutiesasa typeofinheritancetaxandstampdutiesoninvestments.Fordetailsonthefinancing sourcesoftheOPA,see Murray(2009)

17 Earningsabove£5,000constitutedthetop0.05%ofearnings,accordingto Atkinson(2005)

18 Thisgroupincludedabout75%oftaxpayers,e.g.750,000outof1,000,000 (Murray,2009).

theirearningswerebelowthetaxationthresholdof£160(2.7times themeanearnings)andwerealsonotaffectedbyincometax changes.19

3.EmpiricalStrategyandData

3.1.ExogenousVariationandResearchDesign

ToidentifythecausaleffectofpensionavailabilityonLFP,we takeadvantageoftheagecutoffthatwasintroducedbytheOPA. Pensioneligibilityatage70createsadiscontinuityinthelocal environmentbetweenage69and70.Alongthelinesofthisage threshold,weadoptanRDdesignwiththeageasassignmentvariable.Theidentifyingassumptionisthattheoutcomeofinterest, LFP,wouldevolvesmoothlybetweenage69and70iftheOPA hadnotbeenintroduced.Anydiscontinuousjumpoftheoutcome attheeligibilitycutoffcanbeattributedtotheavailabilityofthe pensionifotherprogramsdidnotaffectLFPattherespectiveage.

3.2.Estimation

Theobservableoutcome ya isanindicatorofLFPthattakesthe valueoneiftheindividualisinthelaborforceatage a andzero otherwise.Wethusestimatetheequation ya ¼ b0 þ b1 1ða P 70Þþ b

wherethecoefficientofprimaryinterest, b1 ,measuresthepercentagepointdifferenceinLFP,comparingtheshareofpeopleinthe laborforcemarginallyabovetheagecutoff(age70)totherespectivesharemarginallybelowtheagecutoff(age69).Toaccount forthepossibilityofafunctionalrelationshipbetweentheoutcome LFPandtheassignmentvariableage,thefunction f ðaÞ,whichis allowedtovaryoneithersideoftheagecutoff,notonlyincludes agelinearlybutalsoasasecondorderpolynomial.However,graphicalevidencesuggeststhattheage-LFPrelationshipisessentially linearclosetotheage-cutoff.

Toshowthatourresultsareexceptionallyrobustagainst changesinthespecification,weimplementseveralalternativeestimationproceduresthatarecommonintheRDliterature.We extendthebaselineestimationframeworkwithuniformweighting tomoreflexiblelocalnon-parametricestimatesthatputmore weightonobservationsclosetothecutoff(triangularkernel weighting).Wealsopresentbias-correctedpointestimatesassuggestedby Calonicoetal.(2014a,b) andprovidedetailedresultson howtheestimatesdifferbybandwidthchoiceandtheorderofthe polynomial.Finally,weshowthatusingalternativetypesofstandarderrorsdoesnotchangeourconclusions(seeSection 4.3).

3.3.DataandSummaryStatistics

Theanalysisreliesonfull-countindividuallevelcensusdatafor threedecennialUKcensuswavescollectedinthespringof1891, 1901and1911.ThedatasetisarecentreleasebytheIntegrated CensusMicrodata(I-CeM)project(Higgsetal.,2013),distributed byIntegratedPublicUseMicrodataSeriesInternational(IPUMS International MinnesotaPopulationCenter,2018).20 WeuseinformationforEnglandandWales,thusexcludingScotland,Irelandand theChannelIslandsbecausedataisnotavailablefortheother

19 Atthattime,onlyonemillionpeoplepaidincometaxesintheUK(Murray,2009) comparedtomorethan36millionpeoplelivinginEnglandandWalesalone.

20 TheI-CeMprojectcollaboratedwiththewebsitefindmypast.orgtotranscribeand harmonizeseveralhistoricalBritishcensuses,encompassingdatacollectedinthe years1851,1861,1881,1891,1901,and1911.Recenteconomicstudiesthathave usedselectedwavesare,forexample, Arthietal.(2021) and BeachandHanlon (2019)

regionsatallpointsintime.Moreover,birthcertificates,whichsubstantiallyreduceage-misreporting,onlyexistedinEnglandand Walesforasufficientlylongperiod.Finally,weexcludepersonswith unknowngender(lessthan0.1%ofthepopulation)orage(0.2%of thepopulation).

3.3.1.DependentVariable

Ourdefinitionofthelaborforcestatusisbasedonthegainful employmentconceptwhichwasusedbeforetheUKadoptedthe currentlaborforcedefinitionin1961.Incontrasttothecurrent definition,whichcategorizespeoplebasedontheiractivitystatus (workingorseekingwork)inaspecificreferenceweek,thegainful employmentconceptderivesthelabormarketstatusfromthe occupationoftherespondents.Inparticular,weincludepeople inthelaborforce(LFP=1)iftheyspecifyanoccupationorreport tobeunemployed.21 Individualsareconsideredoutofthelabor force(LFP=0)iftheyreportnooccupationorthattheyhaveretired fromaspecificoccupation.22 ThecurrentdefinitionofLFPandthe gainfulemploymentconceptarecloselyrelated. Costa(1998) constructsparticipationratesbasedonthegainfulemploymentconcept fortheUSuntilthe1990s,showingthatthepatternsofbothseries match.Similarly, Johnson(1994) arguesthatthechangeofthedefinitionin1961did‘‘appeartohavehadlittleeffectontheenumerationofolderworkers”(Johnson,1994,p.109).Basedonthis evidence,thetwoconceptsarguablyyieldverysimilarpatternsof LFPovertime.Forourempiricalanalysis,potentialdifferences betweenthetwoconceptsareoflittlerelevancebecausethegainful employmentconceptdidnotchangethroughoutthetimeunder study(1891–1911).Differencesonlyneedtobekeptinmindwhen comparingtheresultstothecurrentLFPconcept.

3.3.2.SummaryStatistics

Usingfull-countcensusdataenablesustozoomindirectlyat theagecutoff. Fig.1 showsthedistributionofobservationsover ageforthe1911census,including150,293individualsatage69 and140,288individualsatage70.Exceptforminorroundnumber bunching23 thesamplesizedeclinesalmoststeadilywithage.While the1911censuscountsmorethan400,000individualsatage50,the numberofindividualsdropsbelow5,000atage90.

Summarystatisticsin Table1 (upperpanel)reportaconsiderabledeclineinLFPbetweenage69and70.Thedroptotalsto7percentagepoints(from46%to39%),whiledifferencesinother observablecharacteristicsarefairlysmall.Atage70,individuals arelessoftenmarriedandtheshareofforeignbornindividualsis slightlyhigher.Thelowerpanelin Table1 reportssummarystatisticsforthebaselineestimationsamplewithfiveage-yearsbelow thecutoff(65–69,N:803,208)andabovethecutoff(70–74,N: 551,100).Includingadditionalage-yearsnaturallyleadstoalarger differentialinmeanLFPratesof48%belowtheeligibilityageand 34%above.

Throughoutthisstudy,weexaminethelaborsupplyresponses jointlyformenandwomen.Sincetheparticipationratesofwomen weregenerallylow,wealsopresentthemainresultsseparatelyfor

21 Wealsoincludepeoplethatreporttobeformerlyemployedinthelaborforce. Recodingthissubgroupasnotinthelaborforcedoesnotaffectourresults.

22 Followingthecensusin1891,retirementwasexplicitlyrecognizedasaseparate categoryandretireeswerenotconsideredeconomicallyactiveanymore(Johnson, 1994),whichisarguablyconsistentwithbeingoutofthelaborforce.Weadjustthe laborforcevariableconstructedbyIPUMSInternationalbydefiningindividualstobe outofthelaborforceiftheystateanoccupationbutaddthattheyhaveretired already.

23 Note,forexample,thesmalldipinthenumberofobservationsatage71.Spikesin thesamplesizeatroundages(‘‘age-heaping”)arecommonin(historical)surveydata. Peoplemightroundtheirageeitherbecausetheyareuncertainabouttheirexactage, orbecausetheyareinnumerateorinattentive.Wediscussthisissueinmoredetailin Section 4.3.3

menandwomen.24 Ingeneralandforbothmenandwomen,the declineofLFPratesoverageevolvedlesssteeplythantoday.Wewill argueinthispaperthatonemajorexplanationforthisphenomenon wasthelowcoveragebysocialsecurityandold-agepensionsinthe early20thcentury.

Themajorityofolderworkers(almostonethird)wasactivein sectorssuchascraftsorrelatedtrades(Table2).Thesecondlargest sectorincludedserviceworkers,followedbyskilledagricultural andfisheryworkandelementaryoccupations.Incontrast,only fewolderworkersearnedalivingasseniorofficialsormanagers, techniciansorotherprofessionals.Weuseoccupationalinformationlater-ontoconstructameasureofoccupationallaborearnings. Thisallowsforestimatesofthelaborsupplyresponsetopension availabilityindifferentregionsoftheoccupationalearnings distribution.

4.TheLaborSupplyEffectoftheOPA

4.1.BaselineResults

Table3 reportsthedeclineinlaborsupplyduetotheOPAfor ourpreferredRDspecification,usingabandwidthof5age-years totheleft(65–69)andtotheright(70–74)oftheagecutoff,alinearagepolynomial25,anduniformweightingonallobservations. TheestimateshowsapreciselymeasureddropinLFPof6.0percentagepointswhenpeoplereachtheage-basedeligibilitythreshold. ContrastingtheLFPdistributionoverageseparatelyforthe1901 andthe1911censuses, Fig.2 revealsthestrikingdifferenceinagespecificLFPpatternsbeforeandaftertheOPAbecameeffectivein 1909.Withoutuniversalcoveragebyold-ageassistancein1901,participationratesdeclinegraduallyoverage.Incontrast,weobservean abruptdropofLFPin1911exactlyattheage-basedeligibilitycutoff. Thesuddendroponlyappearsattheeligibilityageandonlyafterthe OPAhasbeenintroduced.Sincenoothersocialsecurityprograms existedthatwouldinduceLFPchangesbetweenage69and70,the LFPreductioniscausedbytheavailabilityoftheOPA.

Theestimateddeclineissizablebothinabsoluteandrelative terms.Departingfromaparticipationrateof46%atage69,the estimatedabsolutedeclineof6.0percentagepointstranslatesinto arelativedeclineof13%.Giventhescaleoftheprogramandthe limitedsocialsafetynetatthattime,thesubstantialdeclineinparticipationratesisnotsurprising.

24 Table1 indicatesthattheaverageLFPratemarginallybelowtheeligibility threshold(age69)was46%.However,whileonly20%ofwomenwerestill economicallyactiveatthatage,theLFPratesofoldermenwererelativelyhighand totaledto76%(Fig.7).SeeSection 4.2.3 forseparateresultsregardingmenand women.

25 GraphicalevidenceinFig.B.2suggeststhatlinearandquadraticagepolynomials reproducetheLFP-agerelationshipverysimilarlyandthus,forbrevity,wereportthe linearspecificationforallsubsequentRDspecificationsincludingplacebotestsand robustnesschecks.Throughout,theresultsareverysimilarforthequadratic polynomialandareavailablefromtheauthorsuponrequest.

26 Forthisexercise,whichalsoservesasarobustnesscheckforourRDstrategy,we addthecensuswaveof1891inadditionto1901and1911,whichallowsusto graphicallytestthecommontrendassumption.Forthetwoagegroupsatthe eligibilitythresholdsetbytheOPA,thegraphindicatesacommontrendinthepretreatmentperiodbetween1891and1901,showingthatLFPratesofthetwogroups moveintandembetween1891and1901.Thecommontrendisstableforneighboring agesbelowtheeligibilitythreshold(65–69)andabove(70–74),asisevidentfrom Fig.B.3intheappendix.Afterthat,between1901and1911,thetwoagegroups divergeintermsofLFP.TheDiDestimatequantifiestheLFPdifferentialtorange between4.0to4.5percentagepointsdifferencebetweenolderworkersaged69and 70(TableA.1).Iteliminatesanytime-constantunoberservablesthatwouldconfound estimatingtheimpactoftheintroductionoftheOPAonLFP.TheDiDisrobustagainst includinganyavailableobservablecharacteristicssuchasnumberofownchildrenin thehousehold,householdsize,andindicatorsforbeingmarried,foreignborn, disabled,andregion(coveringthe53countiesinEnglandandWales).

TheconsiderableimpactoftheOPAissomewhathiddenin aggregatelabormarkettimeseries.Asnotedby Johnson(1994) and Costa(1998),thedownwardtrendinLFPratesforthegroup ofmenaged65andolderhasnotacceleratedaftertheOPAwas implemented,leadingthemtoconcludethattheOPAhadlittle effect.Asimpledifference-in-differences(DiD)representation26, however,suggeststhat–inabsenceoftheOPA–theLFPdecline forolderworkerswouldhavesloweddownbetween1901and 1911.ThisbecomesevidentwhencomparingLFPtrendsbetween agegroupsjustbelowandabovetheeligibilitythreshold. Fig.3 showsthatparticipationratesofpeoplejustbelowtheeligibility agedecreasedbetween1891and1901butincreasedbetween 1901and1911.Incontrast,forthosejustabovetheeligibilityage LFPrateskeptdecliningovertheentireperiod.ThefactthatLFPrates fortheaggregateofoldermenaged65andoldercontinuedto decreasebetween1901and1911isthereforelikelydrivenbythe OPA.

Ourresultsareconsistentwiththoseof FetterandLockwood (2018),whostudytheintroductionoftheold-ageassistanceprogramintheUS.Theyfindthatthelaborsupplyofmenaged65 to74declinedby8.5percentagepointsbetween1930and1940 asaconsequenceoftheintroductionofold-ageassistancein 1935.OurestimatedLFPdeclineof6.0percentagepointsisslightly smallerinmagnitude,whichismostlyduetotheinclusionof womeninoursample(formoreinformationongenderdifferences seeSection 4.2.3).IncontrasttotheUScase,wherealmosthalfof thedeclinewasexplainedbyexitsfromworkreliefprogramsand unemployment,directtransitionsfromworktoretirementwere moreprevalentintheUK.

Toexaminethelaborsupplyresponseofthepopulationthat retiresdirectlyfromwork,wenowdisregardtheunemployed27 anddeviatefromthemainLFPmeasurebysettingLFP=1only forthosewhoareactuallyworking(andLFP=0foreveryoneelse). Weassumethatthoseindividualsinthedatawhoreportanoccupation(andhavenotretiredyet)areworkingandthatthosewho reporttobeunemployedarenotworking.28 Thisexerciseshowsthat almosttheentiredeclineinLFPisdrivenbypeoplewhostopworking(Fig.4).TheLFPrateamongactiveworkersdeclinessignificantly by5.7percentagepointsattheage-basedeligibilitythreshold (Table4,column1).WhensettingLFP=1forthoseinthelaborforce whoareunemployed,thedropissmall(Table4,column2).The decliningLFPratesarehencestronglydrivenbyolderworkers whodirectlyretirefromwork.

4.2.HeterogeneityAnalysis

4.2.1.LaborSupplyEffectsAcrosstheOccupationalEarnings Distribution

Akeytheoreticalimplicationoftheearningstestisthatlabor supplyresponseswilldifferacrossthelaborearningsdistribution. Substitutinglaborearningswithold-ageassistancebecomes increasinglycostlyaslaborearningsincrease,becausepeoplewith

27 Weconsiderpeopletobeunemployediftheystatetobeformerlyemployed(1.2% ofthepopulationaged50–90)orunemployed(0.1%ofthepopulationaged50–90).

28 Peoplestatinganoccupationarecodedasworking,accordingtotheI-CeMdata codebook(Higgsetal.,2013).However,asnotedinthecodebookthe‘‘boundaries betweenthegroups[peoplewhoareworkingorbeinginactivefordifferentreasons] areratherfluid”,p.203.Inaddition,the1911censuslikelyundercountsunemployment,becauseourowncalculationclassifiesonly0.5%ofworkingagemen(15to69) asunemployedorformerlyemployedwhileasampleoftradeunionmembers quantifiestheunemploymentrateinEnglandandWalesatthetimeofthecensus (April1911)toberather2.8%(DepartmentofLabourStatistics,1913,p.6).Although thismayindicateaslightoverestimationoftheshareofpeopleworking,thetotal unemploymentratewasextremelylowatthetimesuchthatourresult–mostpeople whoretiredwerepreviouslyatleastoccasionallyworking–isveryunlikelytobe drivenbythemis-classificationofunemployedworkersasworking.

M.GieseckeandP.Jäger

high-earningshavetoforgomoreincome(andconsumption opportunities)tobecomeeligible.

Wetestthispredictionusingoccupationalearningsasaproxy forindividualearnings,whicharenotreportedinthe1911census.29 AnobviousapproachwouldbetoestimatetheLFPdropconditionalon(former)occupation.Sinceoccupationalinformationis onlyavailableforaselectedsubsetofretirees,weexploitthediscontinuityintheshareofactivepeople(LFP=1)inoneearningsgroup relativetothetotalpopulation(formoredetails,seeOnlineAppendixC.2). Fig.5 showsthatnegativelaborsupplyresponsesaremore pronouncedatthelowerendoftheoccupationalearningsdistributionthanatthetop.Inthelowestearningsquartile,LFPdeclines by15.3%andthusmorethantwicecomparedtothehighestearning quartile(7.2%).Thelaborsupplyresponsegapbetweenhigh-and low-earnersbasedonindividualearningsdatamightbeevenbigger, sincethesignificantdeclineinthehighestoccupationalearnings groupcouldarguablybedrivenbylow-earningspeopleworkingin high-earningsoccupations.

4.2.2.FamilyBackgroundandOld-AgeInsurance

Thefamilycanfunctionasold-ageinsurance,especiallywhen individualsarecreditconstrainedanddonothaveaccesstosocial security.Theinsuranceargumenthasmainlybeenpointedout withregardtochildren(Leibenstein,1957;Caldwell,1982;Cain, 1983;BoldrinandJones,2002),butpublicold-ageassistancecan replaceanytypeoffamily-relatedtransfers(e.g.fromspousesor otherrelatedhouseholdmembers).ThismechanismwasrecognizedduringthelegislationprocessoftheOPAand,aftersome debates,itwasfinallydecidedthatvoluntaryfamilytransfersmust beincludedinthecalculationoftheannualmeansofapension claimant(Casson,1908).

Giventhatprivatetransfersareconsideredinthemeanstest, familytiesmightaffecteligibilityandthecorrespondinglaborsupplyresponsetotheOPA.Olderworkerswhoreceiveprivatetransfers(e.g.fromfamilymembers)mighteithernotpassthemeans testorhavealreadyusedthefamilytransferstoretirebeforethe ageof70.Consequently,theirlaborsupplyresponseattheeligibilityageisexpectedtobelesspronounced.Incontrast,individuals whodonotreceiveprivatetransfershavetoworkuntilpension benefitsbecomeavailable(iftheylacksavings)andthusare expectedtoreactmorestronglywhentheyreachtheeligibility age.

Althoughwedonothaveinformationonwithin-familycash transfers,wecantestthreedimensionsoffamilytiesbasedon existinglivingarrangementsandmaritalstatus.First,weproxy inter-generationaltransfersfromchildrenbydistinguishingolder workerswithandwithoutownchildreninthehousehold.30 Second,weusemaritalstatustoproxytransfersinspousalrelationships.Andthird,wecomparesingleversusmultipleperson householdsasamoregeneralmeasurefortransfersfromclosely relatedindividuals.

Table5 reportsRDestimatesfromsamplesthatarestratifiedby individualswithandwithoutownchildreninthehousehold.These estimatesindicatethatolderworkerswithoutownchildreninthe householdshowstrongerdeclinesinLFPrates:attheage-based eligibilitythreshold,LFPfallsby6.9percentagepoints.Incontrast, LFPdeclinesbyonly5.1percentagepointsamongolderworkers withchildren(z-statisticofsignificantdifferentdifferences=2.0).

29 Weconstructoccupationalearningsbasedonthereportedoccupationaltitleon thefive-digitoccupationalHISCOlevelintheUK1911censusaswellearningsdataby occupationfromtheUScensusin1950.SeeAppendixCfordetailsincludingthe resultingoccupationalearningsdistributioninFig.B.4.

30 Notethatgiventheageoftheirparentsalmostallchildrenareinworking-age already.Morethan95%ofchildrenare15yearsorolder,morethan90%are20years orolder.

Graphicalevidencein Fig.6 supportstheestimationresults.The findingofstrongerLFPreactionsamongolderworkerswithout childrenisconsistentwiththehypothesisthatchildrenservedas atypeofold-ageinsurancebeforesocialsecuritysystemsexisted.

Theinsuranceargumentisparticularlysalientwhenlookingat solitaireindividuals.Consistentwiththisview,thelaborsupply reductionsamongnon-marriedindividualsarelargercompared tothesub-sampleofmarriedindividuals(Table5, Fig.6)although theseestimatesdonotsignificantlydiffer(z-statistic=0.6).Individualslivingcompletelyontheirown(singlehouseholds)respond verystronglytothepensionincentive.Individualslivingalone showlargeLFPreductionsof9.5percentagepoints,whilethoselivingwithoneormoreotherpersonsreactsignificantlyless(5.7percentagepoints,z-statistic=-3.9).

Oneconcernisthatlivingarrangementscorrelatewithearnings.Infact,wedofindthatoccupationalearningsarelowerin eachofthethreegroupsthatshowmorepronouncedlaborsupply reductions(nochildren,non-married,andlivingalone).However, wearguethattheresultsarenotentirelydrivenbyearningsgaps fortworeasons.First,theoccupationalearningsgapsarerather small(£6to£8onaverage).Second,theoccupationalearningsgaps arenotcorrelatedwiththelaborsupplyresponsegaps.For instance,weseethebiggestoccupationalearningsgapbetween marriedandnon-marriedpeople,butthesmallestLFPresponse gap.Anotherconcernisthatwemightconditiononoutcomevariables,sincethehouseholdcompositionandmarriageincentives couldalsobeaffectedbythepension.Weconsiderthistobea minorconcernsincethesmoothnessanalysisinSection 4.3.1 suggeststhatthereislittleevidenceforasubstantialchangeinmarriageratesandlivingarrangementsatthecutoff.

4.2.3.LaborSupplyEffectsbyGender

Aparticularlyrobustfindingdocumentedintheliteratureon laborsupplyisthatwomenhavemuchlargerlaborsupplyelasticitiesthanmen,especiallyontheextensivemarginoflaborsupply (see Keane,2011,forareview).Oneimportantdifferencebetween menandwomen,inparticularwhenusingdatafromtheearly20th century,isthatalargeshareofwomenwasnotpartofthelabor forcebasedontheprevalentdefinition.Thisalsoholdsinthe cohortsunderstudyhereandisapparentfromcomparisonsof LFPratesbetweenoldermenandwomen(Fig.7).ThefigureindicatesthatLFPratesattheageof69weremuchlargeramongmen (76%)comparedtowomen(20%).RDestimatesonseparatemale andfemalesamples(Table6)showthat,inabsoluteterms,the laborsupplyresponsesarelargeramongmen(7.9percentage points)ascomparedtowomen(3.2percentagepoints).Whenplacingthesmallerfemalelaborsupplyreductionintothecontextof theirsmallerLFPrate,theirrelativereductionof16%ismuchlarger comparedtomen(10%).Thisresultisconsistentwithlargerfemale laborsupplyelasticitiesasdocumentedintheliterature.

RDestimatesacrosstheoccupationalearningsdistributionalso differbetweenmenandwomen(Fig.8).Especiallyinthesecond earningsquartile,womenshowdramaticlaborsupplyreductions ofupto27%.Duetotheirrelativelylowoccupationalearnings31, womenalsohadlowadjustmentcostsintermsofforgoneearnings topassthemeanstest.Thisislargelyinlinewiththeobservation thatthefemalelaborsupplyresponseisparticularlylargeatthe lowerendofthefemaleoccupationalearningsdistribution.

4.2.4.Within-FamilySpillovers

Manyempiricalstudiessuggestthatwithin-familyspillovers playanimportantroleinretirementdecisions(Blauand

31 Themeanoccupationalearningsofwomenin1911are41£,whichamountsto twothirdsofmeanearningsamongmen(60£).

Riphahn,1999;GustmanandSteinmeier,2000;Baker,2002; Atalayetal.,2019;Garcia-MirallesandLeganza,2021).Theinterdependenceofspousalretirementbehaviormightbedrivenbya correlationoftastesforleisurebetweenpartnersortheeligibility rulesofthepensionsystemthattakespousalincomeintoaccount.

TheUKcensusallowsustolinkthelaborforcestatusof spouses.Weusethisinformationtostudywhetherpeoplerespond tothepensioneligibilityoftheirspouse.Wefocusontheimpactof femaleeligibilityonmaleretirementpatterns,becauseLFPratesof marriedelderlywomenatthetimewereextremelylow(around8% intherelevantagerange)whichleaveslittleroomforadditional femaleretirement.Toprovidegraphicalevidence,wefirstplot maleLFPratesagainstspousalage(insteadofownage).Throughouttheanalysis,werestrictthesampleonmenthatareolderthan 70,andthushavealreadyreachedtheeligibilityage,toavoidthat ourresultsaredrivenbysame-agecouplesreachingtheeligibility ageatthesametime.32

Fig.9 (panela)revealsthatmaleLFPratesdroponcetheir spousereachestheageof70andthusalsobecomeseligible.The dropinmaleLFPratesdidnotexistbeforethepensionwasintroduced.Confirmingthegraphicalevidence,RDestimatesin Table7 (column1)reportasignificantLFPdropof3.3percentagepoints amongeligiblemarriedmenwhenevertheirspousebecomeseligible. Table7 alsoshowsthattheseresultssurviveseveralplacebo testsandarerobustagainstvaryingbandwidths.

TomakesurethattheLFPdropisnotdrivenbythefactthat ownagecorrelateswithspousalage,wealsopresentresultsfor ownage-adjustedLFPrates.Similarto Garcia-Mirallesand Leganza,2021,weconstructownage-adjustedLFPratesbyrunningaregressionofLFPonownageandtakingtheresidual.33 Theresultsdepictedin Fig.9 (panelb)andcorrespondingestimates in Table7 (column2)showthattheestimateddropinage-adjusted LFPratescloselyresemblesthenon-age-adjustedLFPdrop.

Weconcludethattheseresultsarestronglysuggestivefor within-familyspilloversandareinlinewithpreviousfindingson jointretirementdecisionsofcouples.OurfindingisfurthercorroboratedbyanecdotalhistoricalevidencesuggestingthattheOPA wasparticularlybeneficialformarriedcoupleswithtwopensions comparedtootherwiseidenticalsinglehouseholdsreceivingone pensionbutwithlesspotentialforsynergies(see Pugh,2002,p.790).

4.3.ValidityandRobustnessoftheRD

Severalsensitivitychecksandfalsificationtestssupportthe validityofourRDdesign.Basedontheseexercises,theestimates presentedabovecanbegivenacausalinterpretation.

4.3.1.SmoothnessAnalysis

WestartverifyingthevalidityoftheRDbytestingwhether observablecharacteristicsotherthantheintroductionoftheOPA canexplainthediscontinuityinLFP.Therefore,wetestwhether pre-determinedcovariatesexhibitadiscontinuityatthethreshold. Oursmoothnessanalysisincludestheshareofindividualslivingin urbanareas,theshareofforeignborn,theshareofdisabledpersons,thenumberofownchildreninthehousehold,theshareof marriedorindividualslivingalone(similartothesummarystatisticsreportedin Table1).Twovariables(shareurban,numberof

32 Fig.B.5intheappendixshowstheaverageageofmarriedmen(panela)andthe samplesize(panelb)conditionalonspousalage.Givetheconstructionofoursample, theaverageageofmarriedmenisalwaysabove70irrespectiveofspousalage.Thus, agedifferenceswithincouplesarelargestforthelowerendofspousalages(panela). Thelargershareofobservationsaroundtheage70threshold(panelb)indicatesthat loweragedifferencesamongcouplesaremorefrequent.

33 Weruntheregressionforallmenaged50to90oncefortheUKcensusin1911 andseparatelyfor1901.Ageinyearsenterstheregressionasarangeofdummy variables.

children)evolvesmoothlyaroundtheage-basedeligibilitythreshold.Fourvariables,however,showstatisticallysignificantdiscontinuities(Table8 andOnlineAppendixFig.B.6).Predominantly, thesediscontinuitiesareeithernegligiblysmall(sharedisabled, sharesinglehouseholds)ornotrobust(sharemarried).34

Theonlydiscontinuitythatseemsrelevantintermsofmagnitudeistheincreaseintheshareofforeignbornpeopleby1.3percentagepoints.However,weareconfidentthatthisdiscontinuity doesnotthreatenthevalidityoftheRDfortworeasons.First andmostimportantly,weseesignificantandsimilar-sizedLFP declinesfornativesaswellasforforeignbornpeople(Online AppendixTableA.2andFig.B.7).Thus,theLFPdeclineisindependentofthenativitystatus.Second,weobserveexactlythesame increaseintheshareofforeignborn(alsoby1.3percentagepoints) atage70in1901beforethepensionwasintroduced.Therefore,the foreignborndiscontinuitydoesnotseemtobedrivenbytheavailabilityofthepensionbutcanbeexplainedbyage-heaping(round numberbunching).OnlineAppendixFig.B.8showsthatthenumberofforeignbornpeopleexhibitsaverypronouncedage-heaping patternin1901aswellasin1911,whichdirectlytranslatesintoan increaseintheshareofforeignbornatroundagesgiventhatageheapingislesspronouncedfornatives.

4.3.2.PlaceboTests

Next,weconducttwoplaceboteststoshowthatLFPeffectsdo notappearatanyarbitrarilychosenagecutoff.First,werunthe baselineRDspecificationonthe1901censustoensurethatthe abruptLFPdeclinemeasuredaftertheintroductionoftheOPAin 1911doesnotoccurin1901. Table9 (upperpanel)indicatesthat thereisnosizableLFPdeclinein1901,consistentwithgraphical evidencein Fig.2 thatindicatesasmoothLFPdeclineoverage beforethepensionwasintroduced. Table9 alsoshowsthatthere isnosubstantialdropinLFPatage60inthe1901census.Since thebirthcohortthatreachedage60in1901eventuallyreached age70in1911,thisrobustnesscheckrulesoutthatindividuals whoplayakeyrolefortheidentifyingvariationintheRDdesign alreadyexhibitedanLFPdeclineatearlieragesbeforetheOPA wasintroduced.

Second,werepeattheanalysisforarbitrarilychosenplacebo agecutoffsin1911.RDestimatesin Table9 (lowerpanel)show thatwedonotobserveasimilardeclineinLFPratesatanyhypotheticalagecutoffotherthanthetrueeligibilitythresholdatage 70.35

4.3.3.ManipulationoftheRunningVariable

Eventhoughwecannotformally36 ruleoutthatagemanipulationaffectsourresults,weconsiderittobeanegligiblethreatto identificationforthreereasons.First,pensionswerenotgranted basedontheageprovidedinthecensus,butontheinformationfrom officialbirthcertificatesthatexistedinEnglandandWalesformore thanseventyyears(sinceatleast1837)whenthepensionwas implemented.PeopleinEnglandandWaleshadthereforelittle incentivetomanipulatetheirageinthecensusinordertobecome eligible.Second,althoughthereissomeevidenceofage-heaping37

34 Thediscontinuityfortheshareofmarriedpeopledisappearsonceweinclude quadraticagepolynomials.

35 Thisresultholdsforanyotherhypotheticalagecutoff.Additionalplacebotestson arbitrarilychosenagecutoffsareavailablefromtheauthorsuponrequest.

36 Wehaveconductedtheformalmanipulationtestproposedby Cattaneoetal., 2018.Basedonthistest,wehavetorejectthenullhypothesisofnodifferenceinthe densityatage70.However,weconsiderthisresulttohavelittleinformationalvalue inourcontext,sincewehavetorejectthenullhypothesisforallage-groupsinour sampleexceptforthreeages(86,77and67).

37 Age-heapingitselfdoesnotresultinsubstantialLFPdiscontinuities,e.g.thereis nosignificantLFPdiscontinuityatage60inEnglandandWalesin1911despitethe substantialage-heaping.

attheeligibilityagein1911,itislesspronouncedcomparedtothe USatthetimeorinEnglandandWalestenyearsearlier(Online AppendixFig.B.9).Thus,thereisnoevidencethattheintroduction ofold-ageassistanceresultedinwillfulage-manipulation.Third, wehaveconductedDonut-RDregressionstotesthowmuchour resultsaredrivenbyobservationsincloseproximitytothecutoff. Ifpresent,age-misreportingshouldarguablybemostpronounced forage-groupscloselybeloworabovetheagecutoff. Table10 shows thattheresultsremainrobustifweexcludetheseobservations.

4.3.4.AnticipatoryEffects

AnotherpotentialchallengefortheageRDisanticipatory behavior.Peoplemayrespondtothepensionbyreducingtheir laborsupplyevenbeforetheeligibilityage(e.g.duetoincome effects),whichcouldbiasourestimates.Neither Fig.2,northe Donut-RDestimatesin Table10 northeDiDrepresentationin OnlineAppendixFig.B.3suggestthatanticipationeffectsarearelevantconcern.Totesttheroleofanticipatoryeffectsinevenmore detail,werunanextendedDiDmodelthatcomparesLFPchanges between1901and1911forallages(50to90)tothereferenceage of69(justbelowtheeligibilityage).Thisexerciseonlyallowsusto detectanticipatorybehaviorthatdiffersbyage.Giventhatwork becomesmoreburdensomewithage,however,wearguethatmost anticipatoryretirementwouldoccurintheagegroupsslightly belowthenewlyintroducedeligibilitycutoff.

Fig.10 revealsthatthereislittleevidenceforanticipatory retirementbeforeage70.Infact,theLFPratesofpeoplefrom50 to69havemovedintandembetween1901and1911.Incontrast, LFPratesofpeople70+haveclearlydecreasedrelativetoLFPrates ofpeopleatage69.Thesedifferencesfadeoutinveryoldage(80+) becauseLFPratesinthisagerangewererelativelylowevenbefore thepensionwasintroduced,leavinglittleroomforadditional retirement.

4.3.5.BandwidthChoice,Polynomials,EstimationTechniqueand Inference

WefinallypresentseveraladjustmentstothebaselinespecificationthathavebeenproposedintheRDliteraturetoverifythe robustnessoftheestimatesandthevalidityofstatisticalinference (Table11).First,theestimatesarenotsensitivetobandwidth choiceandonlychangelittlewhenmakingthebandwidtharbitrarilylarge.Second,changingthepolynomialdegreewhenmodeling LFPasafunctionofagedoesnotindicatesizablechangesinthe coefficients.Third,parametricbaselineestimatesarealsorobust tolocalnon-parametricestimationtechniques(conventionaland bias-corrected)assuggestedby Calonicoetal.(2014a,b).Fourth, insteadofclusteringbythe(discrete)runningvariable,ashasbeen proposedby LeeandCard,2008 andiscommonpracticeinmany empiricalapplications(e.g. Cardetal.,2008,2009),wealsoreport standarderrorsbasedontheBME(boundedmisspecificationerror) proceduredevelopedby KolesárandRothe(2018).TheBMEstandarderrorsareslightlylarger,throughout,butdonotaffectour conclusions.Overall,changesinestimates(andstandarderrors) aremoderateevenwhenundertakingconsiderablechangesin bandwidth,agepolynomials,weightingscheme(uniformvs.triangularkernel)orestimationprocedure.

5.DiscussionandImplications

5.1.Mechanisms

Inthissection,wearguethattheestimatedlaborsupply responsetotheOPAisconsistentwithsubstitutioneffectsandconstrainedincomeeffects.Wecannotruleoutthatnewlyestablished socialnormsalsoplayedarolebutconsiderittobelesslikely.

TheOPAincludesanindirecttax(substitutioneffect)anda transfercomponent(incomeeffect).Theclearestevidenceforthe relevanceofthesubstitutioneffectistheclearandabruptdecline inLFPattheeligibilitythreshold.Atthisage,theOPAcreatesakink inthelifetimebudgetconstraintthatisdrivenbytheexistenceof themeanstest.Themeanstestputsanimplicittaxonlaborearnings,whichmakeslabor(relativetoleisure)lessattractive,and resultsinadditionalretirementstartingatage70.Therelevance ofsubstitutioneffectsforlaborsupplydecisionsinasettingwith earnings-testedretirementbenefitshasrecentlybeendocumented intheUScontext(Gelberetal.,2021a,b).

Therelevanceofthetransfercomponent(incomeeffect)ofthe OPAislessclear.Inamodelwithperfectforesight,theincreasein thelifetimebudgetwouldalsoaffectlaborsupplyatyoungerages. However,theresultsofSection 4.3.4 suggestthatlaborsupply belowtheeligibilityagedidnotrespondtotheOPA.Onecompellingreasonfortheabsenceoflaborsupplyresponsesbefore theeligibilityageareliquidityconstraints.Ifpeoplelackassets tocovertheperiodbetweentheirpreferredlabormarketexit andpensioneligibility–andarenotabletoborrowagainsttheir futurepensionbenefits–theycanonlyleavethelabormarketonce theyreachtheeligibilityage.ThetargetpopulationoftheOPAwas probablyatleastpartlyliquidityconstrainedevenbeforereaching theeligibilityage.Moreover,atthetime,creditmarketswere underdevelopedcomparedtotoday’sstandards.38 Furtherpotential reasonsforthelackofLFPresponsesbeforereachingtheeligibility agearemyopicbehaviororuncertaintyaboutfuturechangestopensionlegislation.Giventheseconstraints,anyincomeeffectwould alsoshowupasadeclineinLFPratesattheeligibilityagemaking itimpossibletoseparatesubstitutionfromconstrainedincome effects.

TheLFPdeclineattheeligibilitythresholdcouldalsobeconsistentwithanewlycreatedretirementnormbutweconsiderthis explanationtobelesscompelling.Recentstudieshaveshownthat retirementbehaviorinlong-standingpensionsystemsisnotonly drivenbyfinancialincentives,butalsobyreferencepoints(see e.g. BehaghelandBlau,2012;Seibold,2021).TheOPAwasasalient reformwiththepotentialtoestablishanewretirementnorm, althoughperhapsthetwoyearsthatlieinbetweentheintroductionoftheOPA(1909)andthedocumentedlaborsupplyresponse (census1911)aretooshorttocreateanewreferencepoint.More importantly,thefindingthatpeopleatthebottomoftheoccupationalearningsdistributionrespondmorestronglytotheOPA(Section 4.2.1)speaksagainstnormsasaplausibleexplanation.If normsweredrivingtheresult,wewouldexpectthattheresponse wouldbemorehomogeneousacrossearningsgroups,orevenmore pronouncedatthetopgiventhefindingby BehaghelandBlau (2012) thatpeoplewithhighercognitiveskillsrespondmore stronglytonewlycreatedreferencepoints.

5.2.WelfareImplications

Apriori,thewelfareeffectoftheOPAisunclear.Ontheone hand,theintroductionofold-ageassistanceloweredsocietalwelfarebydistortinglaborsupplydecisions(efficiencyloss).Onthe otherhand,redistributionfromrichtaxpayerstopoorelderlypeopleincreasedsocietalwelfareifthesocietyvaluedequality(equity gain).

38 AccodingtotheJordà-Schularick-TaylorMacrohistoryDatabase(Jordàetal., 2016),theratioofhouseholdloanstoGDPintheUKwas3.5%in1911,comparedto 68.0%in2017.

Theefficiencylossfromthepensionwaslowfortworeasons.39 First,thelaborsupplyresponsewasmodestrelativetothesizeofthe program.Assumingthat,inabsenceofapension,LFPofpeople 70+wouldhaveevolvedasfor65–69yearold’s,lessthan10%of pensionbeneficiariesretiredasaresponsetotheOPA.Second,only high-incomepeoplepaidtaxes(around1millionoutof36million inhabitants)andforthosetaxesrateswerelow(max.8.3%).Thus, fiscalexternalitiesoftheOPAwerelimited.Thelowerlaborsupply ofpoorelderlypeoplehadarguablylittleeffectongovernmentrevenuesandsubstantialbehavioralresponsesoftop-incomeearnersto increasedtaxationareunlikelygiventhelowtaxrates.

Incontrast,theequalitygainwasimmense.Inatimeofhigh incomeinequality,theOPAgeneratedsubstantialtransfersfrom wealthytaxpayers(annualincome:>£5000)topoorelderlypensionrecipients(annualincomebeforethepension:<£30)(seeSection 2).Therefore,weconcludethattheOPAwaswelfare enhancingevenifthesocietyhadonlyasmallpreferencefor equality.

5.3EffectSizeandPolicyImplications

Wenowconductasimpleback-of-the-envelopecalculationto puttheeffectsizeofourLFPestimatesintotoday’scontext.Specifically,wequantifybyhowmuchareversedOPA-typeintervention wouldoffsetthedemographicpressureonthecurrentpensionsystemintheUK.Forthispurpose,weassumeahypotheticalpolicy thatraisestheLFPrateby6percentagepoints(thereverseeffect oftheOPA)intherelevantagerangeandthenexaminehowthis affectstheratioofretireesrelativetothenumberofpeoplein thelaborforce(retiree-to-LFPratio)until2030and2050.Since theexternalvalidityofourestimatesislimited,wedonotspecify howsuchahypotheticalpolicywouldneedtolookliketodayin ordertoraiseLFPratesaccordingly.

Thecurrent(2019)retiree-to-LFPratiointheUKis31.7,implyingthatthereareabout32retireesaged65andoverforevery100 personsinthelaborforce.40 HoldingLFPratesfixed,theretiree-toLFPratiowillriseto38until2030basedonthemediumfertility variantoftheUNpopulationprojections(UnitedNations,2019)). Tokeeptheratioatits2019level(31.7),itwouldtakealmost2.2 millionpeoplewhoswitchtheirstatusfromretiree(numerator)to laborforceparticipant(denominator)in2030.

WeassumethatareversedOPA-typepolicywouldmostlyaffect theLFPrateofpeopleaged65–74.41 Thisagegroupispredictedto consistof7.8millionpeoplein2030andraisingtheirLFPratebythe (reverse)OPAeffectof6percentagepointsimpliesanexpansionof thelaborforcebyaround0.46millionolderworkers.Thisislessthan onequarter(0.46outof2.2million)ofthesizerequiredtokeepthe retiree-to-LFPratioconstant.

39 SeeAppendixD,foranin-depthwelfareanalysis,includingdetailsforthe underlyingcalculation,basedonthemethodologypioneeredby Hendren,2016and HendrenandSprung-Keyser,2020

40 Wecalculatethisratiobydividingthenumberofpeopleoutsidethelaborforce andaged65+(retirees)overthenumberofpeopleinsidethelaborforceatallages.To obtainthismeasurewecombinestatisticsonLFPrates(OECD,2021))withpopulation statistics(UnitedNations,2019)).Thesizeoftheretiree-to-LFPratioissimilartothe demographic‘‘old-agetoworking-age”ratio(31.7in2019)thatisdefinedbythe numberofpeople65+relativetopeopleinworkingage20to64(OECD,2019,p. 176).

41 ThefactthatthesepeopleareeligibleforaStatePension–asuccessorprogramof theOPA–likelycontributestothecurrentlylowLFPratesinthisagegroup(LFPrate of17%in2019).InlinewithourextendedDiDestimates(Fig.10),weexpectthat changestotheStatePension,suchasthealreadyplannedincreaseintheeligibility agefrom65to68untilthemid2040s,willmostlyaffectthelaborsupplyofpeople thatareintheagerangeclosetothecurrenteligibilityage( 65yearsin2019).

Lookingfurtheraheaduntil2050,areversedOPApolicytargetingtheagegroup65–74wouldonlycompensateoneeighthofthe increaseneededtokeepUK’sretiree-to-LFPratioconstant.42 Our back-of-the-envelopecalculationdemonstratesthatfuturereforms tostabilizetheretiree-to-LFPratiohavetoinducemuchlargerlabor supplyresponsesthantheOPA.

6.Conclusions

Inthispaper,wetakeadvantageofauniquehistoricalreform, theOldAgePensionActof1908intheUK,tostudyhowtheintroductionofmeans-testedold-ageassistanceaffectslaborsupply. Usingrecentlydigitizedfull-countcensusdata,weestimatethe causalimpactofthepolicyonthelaborsupplyofolderworkers byexploitingvariationaroundthenewlycreatedage-basedeligibilitythreshold.

Wefindaconsiderablereductionoflaborsupplyinthelocal environmentoftheeligibilitythresholdafterthepensionwas implemented.Whenreachingtheeligibilityageof70,thelabor forceparticipationratedeclinesby6percentagepointsor13%.This declineisstronglydrivenbyolderworkerswhodirectlyretirefrom work(andnotunemployment).Laborsupplyreductionsarelarger whenoccupationalearningsarelowandwhenfamilyties,asa proxyforprivatetransfers,areweak.Ourresultsarealsosuggestiveforjointretirementdecisionsofcouples.

Thetransparentredistributivedesignofthereformallowsusto studytheoverallwelfareimplicationsoftheprogram.Weargue that,despitetheconsiderablelaborsupplydecline,theintroductionofold-ageassistanceintheUKwaswelfareenhancingifthe societywasatleastslightlyaversetoinequality.Thepensionand itsfinancingviahighertopincometaxratescreatedonlylimited behavioralresponses,relativetotheimmensesizeoftheprogram. Incontrast,equitygainswerelargeasthepolicyredistributedfrom thetoptothebottomoftheearningsdistributioninatimeofrelativelyhighincomeinequalityandonlylimitedsocialsecurity.

Thehistoricalsettingallowsustocrediblyidentifythelabor supplyeffectofanold-ageassistanceprogramandthusextends alargebodyofliteraturethatquantifiestheincentiveeffectsof marginalchangesinexistingpensionschemes.Ourresultsare policy-relevant,notonlyfordevelopingcountrieswithoutuniversalcoveragebyold-ageassistance(e.g.inSub-SaharaAfrica),many ofwhicharealsocharacterizedbyhighincomeinequalityandlimitedpublicwelfarespending.Placingthemagnitudeofthelabor supplyresponseoftheOPAintothecontextoftoday’swellestablishedpensionschemesalsosuggeststhatfuturepension reformsthataimtostabilizetheretiree-to-workerratiohaveto beevenmoreprofoundthantheOPA.Raisingtheretirementage byperhapsoneortwoyears,thus,willhardlybeenoughtomeet thechallengesposedbypopulationaging.

DeclarationofCompetingInterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompetingfinancialinterestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedto influencetheworkreportedinthispaper.

Tables

Tables;1–11

42 In2050,UK’sretiree-to-LFPratiowillhaverisento46(using2019LFPrates)and itwouldthenrequirealmost4millionpeoplewhoremaininthelaborforceinsteadof retiringtokeeptheratioconstant.Theagegroup65–74ispredictedtohavegrown to8.2millionpeople,implyingthatthereverseOPApolicywouldincreasethelabor forceby0.49millionpeople.Thiscompensatesoneeighth(0.49outof4million)of theincreaserequiredtokeeptheratioconstant. M.GieseckeandP.Jäger

AppendixA.Supplementarymaterial

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021. 104516

Table1

SummaryStatisticsbyAge(Census1911).

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: Reportedvaluesformenandwomen.Theupperpanelreportsvaluesmarginallybelowandabovetheagecutoff(69and70). Thelowerpanelreportsvaluesforthebaselineestimationsamplewith5age-yearsbelowthecutoff(65–69)andabovethecutoff(70–74).

Table2 OccupationalComposition(Census1911).

OccupationObservationsPercent LegislatorsandManagers10,7810.8 Professionals17,2621.3 Technicians9,2920.7 Clerks14,5001.1 ServiceWorkers151,52811.2 AgricultureandFishery105,4727.8 CraftsandRelatedTrades170,95912.6 MachineOperatorsandAssemblers39,1432.9 ElementaryOccupations54,3484.0 ArmedForces1,8810.1 Active575,16642.5 Inactive779,14257.5 Total1,354,308100

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: Reportedvaluesonoccupations basedonISCOclassificationatthe1-digitlevelforindividualsaged65–74.

Table3 RDEstimatesofLaborForceParticipationattheAgeCutoff(Baseline).

BaselineRDEstimateRelativeDecline -0.060**(0.006) 13%(-0.060/0.456) Observations1,354,308

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimateofthelaborforce participationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0if age<70;=1ifage>=70).Linearpolynomialsinage.Specificationusesabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69,N:803,208)andtotheright(age70–74, N:551,100)oftheagecutoffanduniformweightingonallobservations.Relative DeclineismeasuredbydividingtheRDestimatebythemeanoftheLFPrateatage 69.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(in parentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.

Table4

RDEstimatesofLaborSupplyResponse.

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1 ifage>=70).Estimatesbasedonseparatedefinitionsoflaborforcestatus:LFP=1forindividualswhoareworking(column1)orLFP=1forindividualswhoare unemployed/formerlyemployed(column2).Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69)andtotheright(age70–74)ofthecutoff,alinear polynomialinage,anduniformweightingonallobservations.RelativeDeclineismeasuredbydividingtheRDestimatebythemeanoftheLFPrateatage 69.**,*denotes significanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.

M.GieseckeandP.Jäger

Table5

RDEstimatesStratifiedbyFamilyBackground.

z-Statistic(SignificantDifferences)2.0* MaritalStatus

z-Statistic(SignificantDifferences)0.6 HouseholdSize

SinglePersonHouseholds 0.095**(0.007)

z-Statistic(SignificantDifferences)-3.9**

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1 ifage>=70).Estimatesforsub-samplesalongthelinesofthreetypesoffamilybackgroundvariables.Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69) andtotheright(age70–74)ofthecutoff,alinearpolynomialinage,anduniformweightingonallobservations.RelativeDeclineismeasuredbydividingtheRDestimateby themeanoftheLFPrateatage69.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatagein years.Testingfor differencesbetweentwocoefficientswithknownvariancesyieldsaz-teststatistic(assumedtobenormallydistributed),where b istheestimatedcoefficientforthe respectivesub-sampleand SE denotesthecorrespondingstandarderrors.Thisyields

0fortestingbetweenchildren/nochildren,

6for testingbetweenmarried/non-married,and

9fortestingbetweensingle/multiplepersonhouseholds.

Table6 RDEstimatesbyGender.

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1 ifage>=70).Estimatesforthesub-samplesofmen(column1)andwomen(column2).Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69) andtotheright (age70–74)ofthecutoff,alinearpolynomialinage,anduniformweightingonallobservations.RelativeDeclineismeasuredbydividingtheRDestimatebythemeanofthe LFPrateatage69.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.Testingfordifferencesbetween twocoefficientswithknownvariancesyieldsaz-teststatistic(assumedtobenormallydistributed),where b istheestimatedcoefficientfortherespectivesub-sampleand SE denotesthecorrespondingstandarderrors.Thisyields z

4 0fortestingbetweenMen/Women.

Table7 RDEstimatesforMarriedMen(Age > 70)bySpousalEligibility.

TrueAgeCutoff:AgeofSpouse P70,Census1911

Bandwidth:5Age-Years(Baseline)

Bandwidth:20Age-Years(quadratic)

Bandwidth:10Age-Years(quadratic)

Observations

Bandwidth:5Age-Years(quadratic)

Observations

Bandwidth:4Age-Years(linear)

Bandwidth:3Age-Years(linear)

PlaceboCutoffs

AgeofSpouse P60,Census1911

AgeofSpouse P65,Census19110.015(0.010)0.013(0.008) Observations

AgeofSpouse P60,Census19010.018(0.011)0.017(0.010)

AgeofSpouse P70,Census19010.012(0.008)0.013(0.07)

Observations

Source: UKCensuswave1901and1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrateofmarriedmen(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheage cutoff(=0ifage<70;=1ifage>=70)oftherespectivespouse.Thesampleisrestrictedonmenhavingreachedtheeligibilityageof70(=menthatareatleast71yearsold). EstimatesarecomputedseparatelyforLFP(1)andLFPadjustedbyownage(2).Allregressions(lowerpanel)useabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleftandtotherightofthe cutoff,alinearpolynomialinage,anduniformweightingonallobservations.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standard errors(inparentheses)are clusteredatageinyears.

M.GieseckeandP.Jäger

Table8 SmoothnessAnalysis.

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesoftherespectiveobservable(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1ifage >=70).Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69)andtotheright(age70–74)ofthecutoff,alinearpolynomialinage,anduniformweightingon allobservations.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.

Table9 PlaceboTests.

AgeCutoffRDCoefficientObservations Census1901

70 0.009*(0.004)1,041,111 600.001(0.003)1,889,492 Census1911

69 0.017(0.012)1,446,757 65 0.004(0.002)1,820,152 600.001(0.002)2,293,676

Source: UKCensuswave1901and1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfordifferentplaceboage cutoffs(asindicated).Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleftandtotherightofthecutoff,alinearpolynomialinage,anduniform weightingonall observations.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.

Table10

Donut-RDEstimates.

ExcludedAgesRDCoefficientObservations

1-year(69,71)

0.077**(0.004)1,063,727 2-years(68,69,71,72) 0.076**(0.003)799,849 3-years(67,68,69,71,72,73) 0.087**(0.000)534,770

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1 ifage>=70).Allregressionsuseabandwidthof5age-yearstotheleft(age65–69)andtotheright(age70–74)ofthecutoff,alinearpolynomialinage, anduniformweighting onallobservations.**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.Standarderrors(inparentheses)areclusteredatageinyears.

Table11 AlternativeSpecificationsandInferencefortheBaselineRD.

ClusteredStandardErrorsBMEStandardErrorsClusteredStandardErrors LinearQuadraticLinearQuadraticConventionalBias-Corrected (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)

Bandwidth(Age-Years)

2

7

Source: UKCensuswave1911andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofthelaborforceparticipationrate(dependentvariable)usinganindicatorfortheagecutoff(=0ifage<70;=1 ifage>=70).Parametricestimatesincolumn(1)–(4)useuniformweightingofallobservations.Localnon-parametricestimatesincolumn(5)–(6)usetriangularkernel weightingthatputsmoreweightonobservationsclosertothecutoff.Estimatesincolumn(6)arebasedonthebiascorrectionproposedby Calonicoetal.,2014a;Calonico etal.,2014b.Standarderrorsareclusteredatageinyearsincolumn(1)–(2)andcolumn(5)–(6),whileboundedmis-specificationstandarderrors(BME)proposedby KolesárandRothe,2018 arereportedincolumn(3)–(4).**,*denotessignificanceatthe1%and5%levelrespectively.

Fig.1. NumberofObservationsbyAge(Census1911).Source:OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS.Note:Theverticallineindicatestheage-based eligibilitythresholdbetweenage69and70thatwasintroducedbytheOPAin1909.

Census 1901Census 1911

Fig.2. LaborForceParticipationbyAge.Source:OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(waves1901and1911)andIPUMS.Note:Theverticallineindicatestheage-based eligibilitythresholdbetweenage69and70thatwasintroducedbytheOPAin1909.

Fig.3. LaborForceParticipationOverTimebyAge-BasedEligibility. Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(waves1891,1901and1911)andIPUMS. Note: Thevertical lineindicatestheintroductionofold-ageassistancebytheOPAin1909.

M.GieseckeandP.Jäger

Fig.4. WorkStatus. Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS. Note: Theverticallineindicatestheage-basedeligibilitythresholdbetweenage69 and70thatwasintroducedbytheOPAin1909.

Fig.5. RDEstimatesAcrosstheOccupationalEarningsDistribution. Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesofLFPby earningsquartileinpercent.ForadditionaldetailsseeOnlineAppendixC.

Fig.6. LaborForceParticipationbyFamilyBackground(1911). Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS. Note: Reportedvaluesarelaborforce participationratesoverage.Theverticallineindicatestheage-basedeligibilitythresholdbetweenage69and70thatwasintroducedbytheOPAin1909.

Fig.7. LaborForceParticipationbyGender(1911). Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS. Note: Reportedvaluesarelaborforceparticipation ratesoverage,separatelyformenandwomen.Theverticallineindicatestheage-basedeligibilitythresholdbetweenage69and70thatwasintroducedbytheOPAin1909.

Fig.8. RDEstimatesAcrosstheOccupationalEarningsDistributionbyGender. Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(wave1911)andIPUMS. Note: RDestimatesof LFPbyearningsquartileinpercent,separatelyformenandwomen.ForadditionaldetailsseeOnlineAppendixC.

Fig.9. LaborForceParticipationofMarriedMenbyAgeofSpouse. Source: OwncalculationsbasedonUKCensus(waves1901and1911)andIPUMS. Note: LFPratesofmarried men(verticalaxis)areconditionalonhavingreachedtheeligibilityageof70(=menthatareatleast71yearsold)andareplottedbyageoftherespectivespouse(horizontal axis).Panel(a)depictsLFPrates,panel(b)depictsLFPratesadjustedbyownage.Theverticallineindicatestheage-basedeligibilitythresholdbetweenage69and70thatwas introducedbytheOPAin1909.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

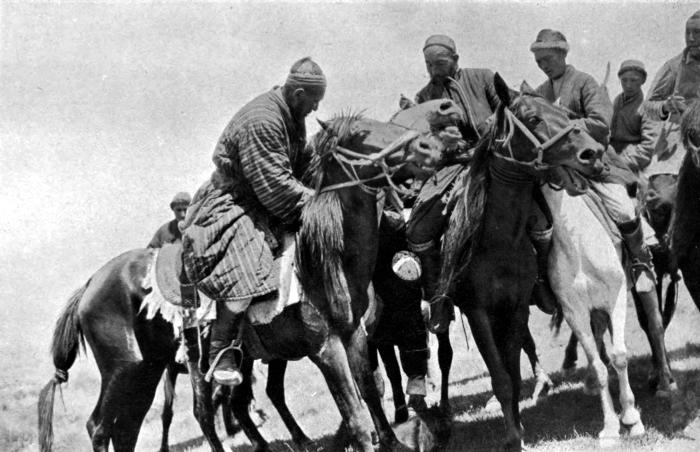

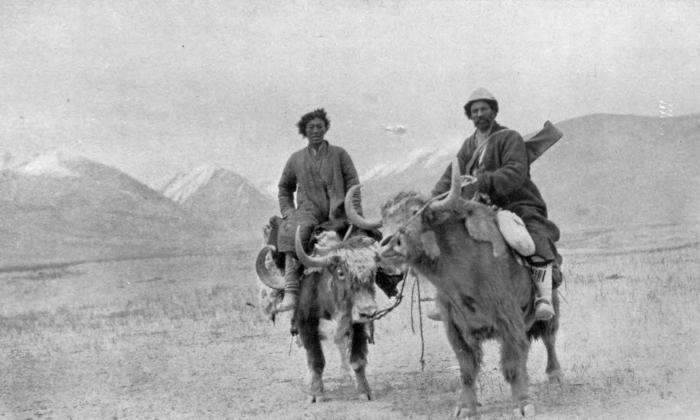

BRINGING IN AN OVISPOLI.

(Nadir with rifle.)

Page146.

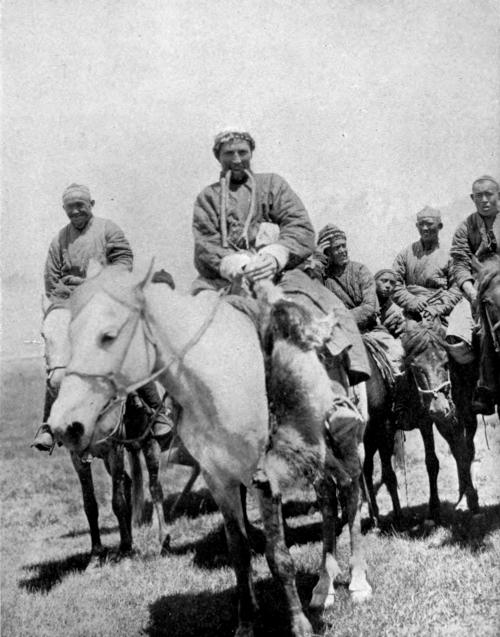

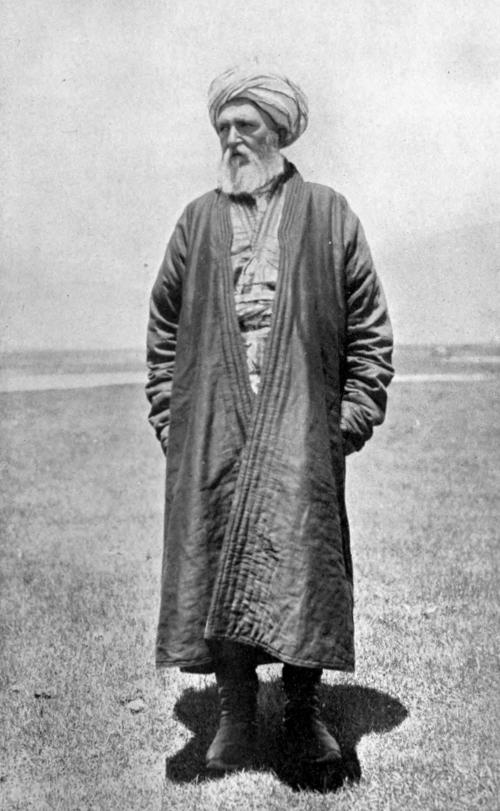

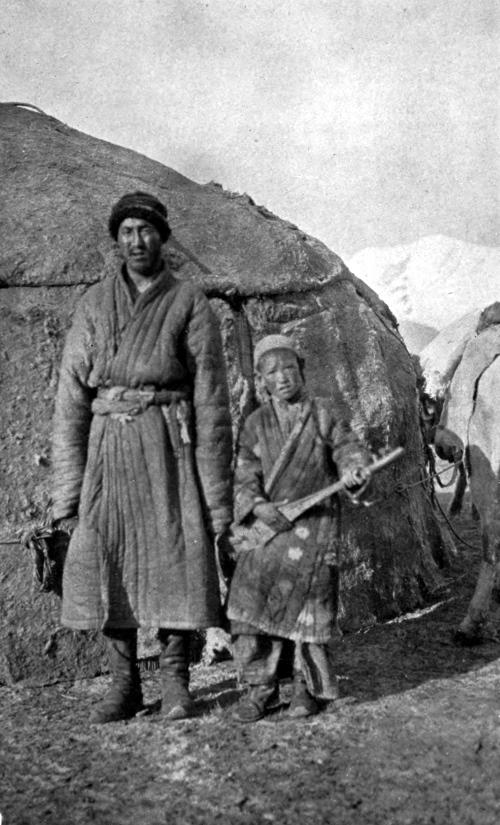

My brother often had some difficulty in arranging the marches, for the Kirghiz have no notion of either time or distance as we understand it, and could never tell us how long a stage would be unless they could compare it with that of the previous day. As a result we seldom knew when we should arrive at our camping ground, the distance being sometimes considerably greater than we had imagined and at other times much less. But such slight drawbacks matter little to the true traveller who has succumbed to the lure of the Open Road, and to the glamour of the Back of Beyond.