Removing

conscientious objection: The impact of ‘No Jab No Pay’ and ‘No Jab No Play’ vaccine policies in Australia

Ang Li a, b, * , Mathew Toll c, d

a Faculty of Medicine and Health, Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

b Sydney Health Economics Collaborative, Sydney Local Health District, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

c Department of Sociology and Social Policy, School of Social and Political Science, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

d LCT Centre for Knowledge Building, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Immunisation coverage

Conscientious objection

Vaccine refusal

Vaccine hesitancy

Non-medical exemptions

Vaccination policy

Financial sanctions

Childcare entry requirements

Immunisation mandates

Interrupted time series

ABSTRACT

Vaccine refusal and hesitancy pose a significant public health threat to communities. Public health authorities have been developing a range of strategies to improve childhood vaccination coverage. This study examines the effect of removing conscientious objection on immunisation coverage for one, two and five year olds in Australia. Conscientious objection was removed from immunisation requirement exemptions for receipt of family assistance payments (national No Jab No Pay) and enrolment in childcare (state No Jab No Play). The impact of these national and state-level policies is evaluated using quarterly coverage data from the Australian Immunisation Register linked with regional data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics at the statistical area level between 2014 and 2018. Results suggest that there have been overall improvements in coverage associated with No Jab No Pay, and states that implemented additional No Jab No Play and tightened documentation requirement policies tended to show more significant increases. However, policy responses were heterogeneous. The improvement in coverage was largest in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage, lower median income, more benefit dependency, and higher pre-policy baseline coverage. Overall, while immunisation coverage has increased post removal of conscientious objection, the policies have disproportionally affected lower income families whereas socioeconomically advantaged areas with lower baseline coverage were less responsive. More effective strategies require investigation of differential policy effects on vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers, and diagnosis of causes for unresponsiveness and under-vaccination in areas with persistently low coverage, to better address areas with persistent non-compliance with accordant interventions.

1. Introduction

Vaccination is among the most effective presentative measures against infectious diseases (Andre et al., 2008). Having a sufficient proportion of the population immunised is required to protect the community through sustained control of vaccine preventable diseases. Although the majority of Australian children are immunised, maintaining high immunisation coverage is imperative to prevent transmission of serious diseases and reduce the risk of local outbreaks (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017). Australia’s national target for childhood coverage is 95%.

With the emergence of global anti-vaccination movements and recent increases in measles cases in Australia, it is important to have

effective vaccination policies to sustain high immunisation coverage. Since the introduction of the National Immunisation Program (NIP) in 1997, childhood immunisation coverage has had substantial increases in Australia. NIP provided free vaccines for eligible people, introduced school-entry immunisation requirements, and offered parental financial incentives for immunisation. Under the NIP, receipt of the Child Care Benefit (CCB) and Family tax Benefit (FTB) part A supplement was linked with childhood immunisation status (Ward et al., 2013).1

During the period when conscientious objection on philosophical or religious grounds was a valid exemption from immunisation requirements for family assistance payments and childcare enrolment, the percentage of children with conscientious objection recorded an increase from 0.23% in 1999 to 1.34% in 2015 (Department of Health,

* Corresponding author at: Faculty of Medicine and Health, Level 2 Charles Perkins Centre D17, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. E-mail address: a.li@sydney.edu.au (A. Li).

1 The CCB replaced previous the Childcare Assistance Rebate and Childcare Cash Rebate in 2000, and the FTB Part A supplement replaced Maternity Immunisation Allowance that discontinued 2012.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106406

Received 18 May 2020; Received in revised form 22 December 2020; Accepted 29 December 2020

Availableonline1January2021

0091-7435/©2020ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

2018). Targeting vaccine objection, the Australian government introduced the No Jab No Pay legislation, implemented in January 2016, that abolished conscientious objection exemptions from immunisation requirements, which was linked to the eligibility for the CCB, Child Care Rebate (CCR) and FTB-A supplement (Parliament of Australia, 201516).2 Only parents of children who are fully immunised on the childhood schedule (see Department of Health (2019b)), on a recognised catch-up schedule, or with approved medical exemptions (e.g. medical contraindications and natural immunity) can receive these payments.

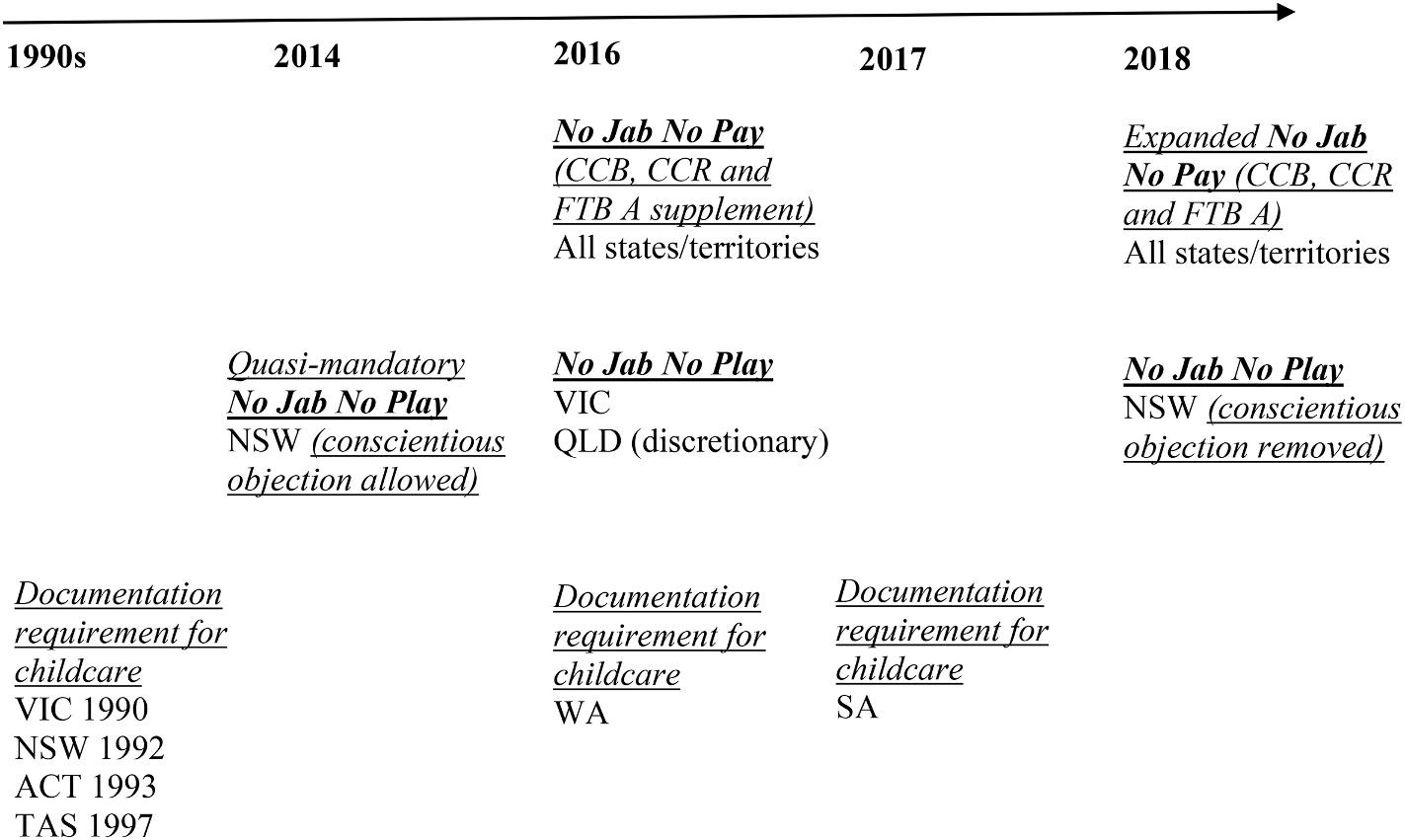

Several state governments augmented the financial penalties with childcare enrolment restrictions under No Jab No Play that applied to approved and licensed childcare centres. In January 2016, Victoria (VIC) prohibited enrolment of unvaccinated children in early childhood services unless they had medical exemptions or on a 16-week grace period for vulnerable families. Meanwhile, Queensland (QLD) allowed childhood services discretion not to enrol unvaccinated children. New South Wales (NSW), which previously required children to be fully immunised or hold an approved exemption to be enrolled in childcare services since January 2014, removed the exemption in January 2018.3 Legislation in the remaining states and territories has been less stringent. A timeline of relevant immunisation policies is displayed in Fig. 1

Evidence on the effectiveness of mandatory immunisation policies on childhood vaccination uptake is limited and mixed (Dub´ e et al., 2015; Omer et al., 2009; Sadaf et al., 2013; Hull et al., 2020). There is scarce evidence on the effectiveness of mandatory immunisation in childcare centres and for countries other than the United States (Lee and Robinson, 2016). Many previous Australian studies lack baseline measurement or control groups (Ward et al., 2012). Adoption of punitive mandates can have unintended negative effects (Leask and Danchin, 2017). Removal of conscientious objection can lead to an increase in numbers of medical exemption claims (MacDonald et al., 2018), reduced equity in childcare access (Beard et al., 2017), and failure to target under-vaccinated groups not registered as objectors (Leask and Danchin, 2017). Australia has consistent geographic clustering of vaccine objection (Beard et al., 2016),

2 These payments altogether could add up to $AU 15,000 a year (Leask and Danchin, 2017). The government expected savings of AU$508.3 millions over five years (Parliament of Australia, 2015-16). Within the 6 month of the introduction of the No Jab No Pay, 5738 children whose parents were receiving childcare payments and claiming vaccination objection had their children vaccinated; and 148,000 previously under-vaccinated children were up-to-date with their vaccination (Commonwealth of Australia, 2016).

3 During 2016–18, an interim vaccination objection form from parents could still be accepted for childcare enrolment.

Fig. 1. Main immunisation policies around financial penalties and childcare enrolment.

Notes: The No Jab No Pay policy abolishes the conscientious objection from immunisation requirements for eligibility of certain government payments. The No Jab No Play policy prevents children who are not immunised from enrolling in childcare centres, not allowing conscientious objection as valid exemption. Documentation requirements are to provide a statement of immunisation status for childcare enrolment. NSW, VIC, QLD, SA, WA, ACT and TAS are states and territories in Australia. Source: Respective Public Health Acts, Public Health Regulations, and Health Amendment Acts across different years in each state and territory; and National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (2019)

which increases risks of outbreaks with unvaccinated clusters in informal childcare arrangements (Leask and Danchin, 2017).

The current study aims to examine the effectiveness of removing conscientious objection that affects government rebates and childcare enrolment on immunisation coverage in Australia. In specific, nonmedical exemptions were removed for government payments (national No Jab No Pay) and childcare enrolment (state No Jab No Play). The impact of these national and state-level policies, largely targeting vaccine refusal, is evaluated using coverage data from the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) linked with regional data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) at the statistical area level 3 (SA3). The study considers coverage rates for the vaccines on the NIP Schedule including Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP), Polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (HIB), Hepatitis B (HEP), Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR), Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, Varicella, and full vaccination at one, two and five years of age.4 Policy response heterogeneity is also examined by area socioeconomic status, median income, numbers of FBT-A recipients and baseline pre-policy coverage, due to potential effect modifying factors (Beard et al., 2016; Beard et al., 2017; Leask and Danchin, 2017; Toll and Li, 2020).

2. Method

Data on childhood immunisation coverage are from the AIR for the period 2014–2018.5,6 The AIR is a national register that records vaccines given to all ages in Australia. Children enrolled in Medicare are registered on the AIR, which constitutes a nearly complete population (Department of Health, 2007). The data contain quarterly vaccination rates at the SA3 level at the milestone ages of one (12–15 months), two (24–27 months) and five (60–63 months), for DTP, Polio, HIB, HEP, MMR, Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, Varicella and full vaccination.

4 Based on the NIP Schedule, DTP, Polio, HIB, HEP, Pneumococcal and fully immunised (Pneumococcal included in December 2013) are assessed at one year of age. DTP, Polio, HIB, HEP, MMR, Meningococcal, Varicella and fully immunised (Meningococcal, and MMR dose 2 and Varicella dose 1 included in December 2014, and DTP dose 4 included in March 2017) are assessed at two years of age. DTP, Polio, MMR and fully immunised (MMR removed in December 2017) are assessed at five years of age.

5 The Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) that recorded vaccinations given to children under the age of 7 was expanded to become the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) that records vaccinations given to people of all ages in September 2016.

6 Data involve only information publicly available and therefore no ethics review was required.

Table 1

Summary statistics for immunisation coverage and regional characteristics, 2014–18.

Notes: There were a few changes in the antigens assessed for the coverage calculation at milestone ages (Department of Health, 2019a). In December 2013, Pneumococcal for children aged 12–15 months was included. In December 2014, Meningococcal and dose 2 MMR and dose 1 varicella (MMRV) for children aged 24–27 months were included. In March 2017, dose 4 DTP for children aged 24–27 months was included. In December 2017, dose 2 MMR for children aged 60–63 months was removed.

There were 358 SA3 regions covering Australia in 2016. SA3s generally have a population between 30,000 to 130,000 people, closely align with Local Government Areas, and represent areas with district identity and similar socioeconomic characteristics (ABS, 2016a). Nonspatial SA3s that cannot be mapped in each state or territory are recorded with one coverage rate in each state or territory at each age group without identification codes. These non-mapped SA3s are not included in the main study but used for robustness checks. Coverage rates for SA3s with fewer than 50 individuals, around 20 SA3s per quarter per age group, were supressed and not included in the study. Data on regional characteristics at the SA3 level were obtained from the ABS and included variables for population, economy, income, education, employment, health, and family.7 The regional data from the ABS were matched with the coverage data from the AIR using SA3 identification for SA3s with more than 50 individuals.

The analytical approach is based on an interrupted time series (ITS) framework. ITS approaches account for pre-intervention trends and are well-suited to studies of population-level interventions occurring at a defined time point. A before and after or ITS method was applied to compare changes in vaccination coverage before and after No Jab No Pay. A difference-in-difference (DID) or controlled ITS method was applied to compare the difference in the changes of vaccination coverage across states and territories with state-level immunisation policies of different degrees of stringency, that is, before and after No Jab No Play and tightened documentation requirement policies.

7 Most measures used in the study are available from 2014 to 2018 and some are only available until 2017, including median income, Gini coefficient, the number of jobs, and the number of private insurance holders. These variables are extrapolated to 2018 using a simple moving average method.

Generalised linear models with a binomial distribution and a logit link function were used to explore the association of immunisation coverage at each age group with policy indicators, adjusting for regional sociodemographic characteristics, states and territories indicators, quarter indicators, and national and state time trends. Standard errors were adjusted for unspecified heteroscedasticity and within-SA3 correlation over time. The specification is as follows:

Coverageijt = f ( Post year1t + Post year2t + Post year3t + Post year1t

× state/territoryj + Post year2t × state/territoryj + Post year3t × state/territoryj + state/territoryj × Tt + state/territoryj × T 2 t + Tt + T 2 t + state/territoryj + quartert + Xijt )

The unit of analysis is at the state-SA3-quarter level. The dependent variables are childhood vaccination coverage rates of DTP, Polio, HEP, HIB, Pneumococcal, Meningococcal, MMR, Varicella and full vaccination for one, two- and five-year olds at SA3 i, state or territory j, and quarter t Linear and quadratic time terms control for secular trends shown in the coverage rates at the national and state or territory level over time. State or territory indicators control for time-invariant unobserved factors common within states or territories, and quarter fixed affects account for any seasonal variations. Estimates are expressed as average marginal effects (AMEs). A series of robustness checks were performed on sample selection and model specification (see Appendix B).

Several coefficients are of interest for policy evaluation. The coefficients on Post year1t, Post year2t, and Post year3t measure the change in the level of coverage post-implementation of No Jab No Pay at the national level in 2016, 2017 and 2018 compared to pre-policy (2014–2015). The coefficients on Post year1t × state/territoryj, Post year2t × state/territoryj, and Post year3t × state/territoryj measure the

difference in the change of coverage after implementation of national and state policies between states and territories.

The regional sociodemographic covariates (Xijt) include proportions of working age population aged 15–64, median age of usual residents, total fertility rates, population density, median total income, Gini coefficient, numbers of FTB-A and FTB-B cases, numbers of jobs for males and females, numbers of taxpayers with private health insurance, and the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) quintiles.8 IRSAD summarises information on income, education, occupation, and dwelling conditions of people and households within an area (ABS, 2016b).

Heterogeneity analyses were also performed according to potential policy effect modifying variables. The model specification included interactions of policy indicators (post year dummies and their interactions with state dummies) and indicators for area socioeconomics, median income, numbers of FBT-A recipients, and baseline coverage in 2014.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of coverage rates

The sample mean and standard deviation of SA3-level immunisation coverage rates for one, two and five age groups and regional covariates from 2014 to 2018 are reported in Table 1. The coverage rates have been high across the country and have improved over time. There are significant variations at the SA3-level with the full immunisation coverage in 2014 ranging from 76.9% to 100%, 73.6% to 100%, and 77.5% to 100% for one, two and five years olds, although the variation in local coverage rates has decreased over time. Regional factors reveal the general social trends in Australia.

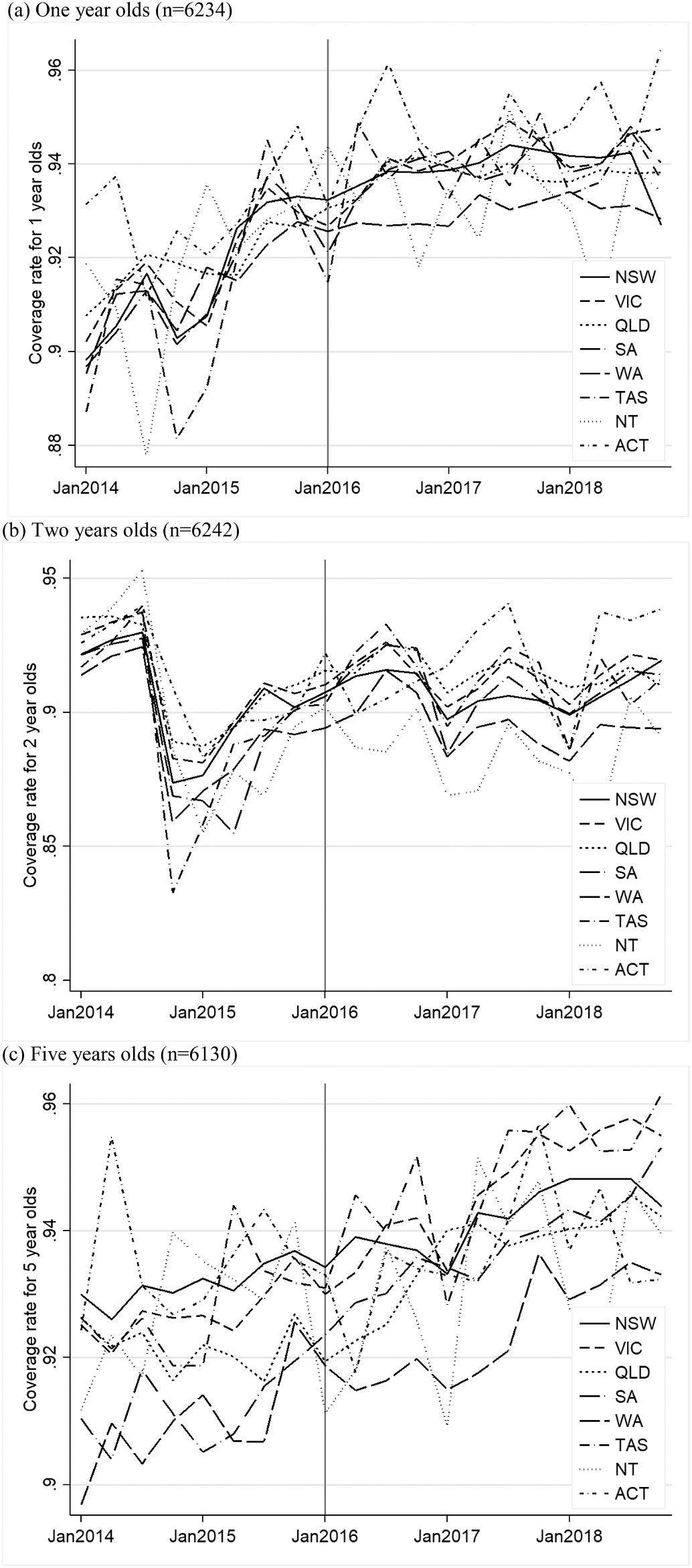

Fig. 2 shows changes in quarterly coverage rates for each state and territory over time by age groups. Quarterly coverage rates are calculated as the weighted mean of coverage rates at each quarter, in each state or territory, and for each age group. Coverage for one year olds shows different rates of change before and after 2016, coverage for two year olds has been increasing at a decreasing rate since September–December 2014, and coverage for five year olds was more linear over time. Coverage rates in ACT and VIC were among the highest across the country.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 present the main policy effect estimates from generalised linear models for the effect of No Jab No Pay, No Jab No Play, and tightened documentation requirement policies related to removal of conscientious objection on childhood vaccination coverage for various vaccines at one (Table 2), two (Table 3) and five (Table 4) years of age, respectively. The results for other covariates (see Table A2, A3 and A4), overall policy effects at the national level (Table A1), and robustness checks (Table B1) are reported in the Appendix. At the national level, there have been significant increases in coverage, with the increase for one and two years olds showing stabilisation in the third year post No Jab No Pay and the increase for five years olds being more persistent (Table A1).

3.2. Vaccine coverage among one-year-old cohorts

Controlling for national and state time trends and state fixed effects, compared to pre policy, No Jab No Pay and No Pay No Play in January 2016 were associated with increases in coverage across vaccines in VIC and QLD by 2–4 percentage points, with QLD showing more significant increases. No Jab No Pay in January 2016 led to an increase in coverage in NSW by around 2 percentage points in 2016, 2.7 percentage points in 2017, and

8 Logarithmic transformations are conducted for population density, median income, the number of FTB cases, the number of private insurance holders, and the number of female and male jobs to adjust for the large scale across observations. The log of population density is constructed as the log of population density plus one to adjust for less-than-one values. Median income is inflated to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index from the ABS.

Fig. 2. Coverage rates of full vaccination among states and territories by age groups, 2014–18.

Notes: NSW, VIC, QLD, SA, WA, ACT and TAS are eight states and territories in Australia. In December 2014, Meningococcal and dose 2 MMR and dose 1 varicella (MMRV) were included in the definition of fully immunised for the 2years-olds, and in March 2017, dose 4 DTP was included in the definition of fully immunised for the 2-years-olds. These changes explained the drops in the 2-year-olds coverage rates (Department of Health, 2019a).

Table 2

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage for one year olds.

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. AMEs times 100% give percentage points. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%.

with the additional No Jab No Play in January 2018, around 3 percentage points in 2018. No Jab No Pay and tightened documentation requirements in 2016 led to a 2.7% increase in 2017 and a 3.8% increase in 2018 in full vaccination for WA.9 Increases in other states have been less significant. Coverage rates have significant upward time trends at the national level that explains some of the increase in the coverage for one year olds over time (coefficients not shown). The increasing time trends likely reflect implementation of a series of government vaccination strategies following the NIP such as state campaigns, reminder systems, financial incentives for providers and parents, and broadened awareness of vaccination among parents.

3.3. Vaccine coverage among two-years-old cohorts

Following No Jab No Pay and No Pay No Play in 2016, QLD had

9 Note the increase in Pneumococcal was partially the artefact of its inclusion for the coverage definition in December 2013.

significant increases in coverage in Polio, HIB and HEP by 0.7–0.9% in 2016 and 1.0–1.2% in 2017, more significant than the increases in VIC. No Jab No Pay in 2016 was associated with increased coverage by around 0.7% in 2016 and 1.2% in 2017 in NSW, and together with No Jab No Play, by around 1.5% in 2018.10

3.4. Vaccine coverage among five-years-old cohorts

No Jab No Pay and No Jab No Play in QLD led to an increase in the full vaccination by 0.8% in 2016, 2.5% in 2017, and 3.0% in 2018. These two policies in VIC led to an increase in the full vaccination by 0.3% (insignificant), 0.8% and 1.4% in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively. No Jab No Pay was associated with a 0.3% (insignificant) increase in 2016 and a 0.7% increase in full vaccination for NSW, and the additional No

10 Note that there were some changes in the coverage definition in DTP in March 2017 and MMR, Varicella and Meningococcal in December 2014.

Table 3

Effects of immunisation

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. AMEs times 100% give percentage points. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%.

Jab No Play was associated with a 1.2% increase in 2018.11No Jab No Pay and tightened documentation requirements in SA and WA brought about 2–3% increases in coverage. In particular, the increase in full vaccination was largely driven by the improvement in MMR. Significant increases in coverage were not observed in the remaining states.

3.5. Regional factors associated with full vaccination coverage

The proportion of working age population, median age of usual residents, population density and Gini coefficient were negatively associated with the full vaccination coverage, while the number of taxpayers who report having private health insurance was positively correlated with full vaccination coverage (see Tables A2-4). Moreover, vaccination coverage significantly decreased as area socioeconomic status increased for one, two and five years olds.

11 MMR was not assessed at five years old since December 2017.

3.6. Response heterogeneity

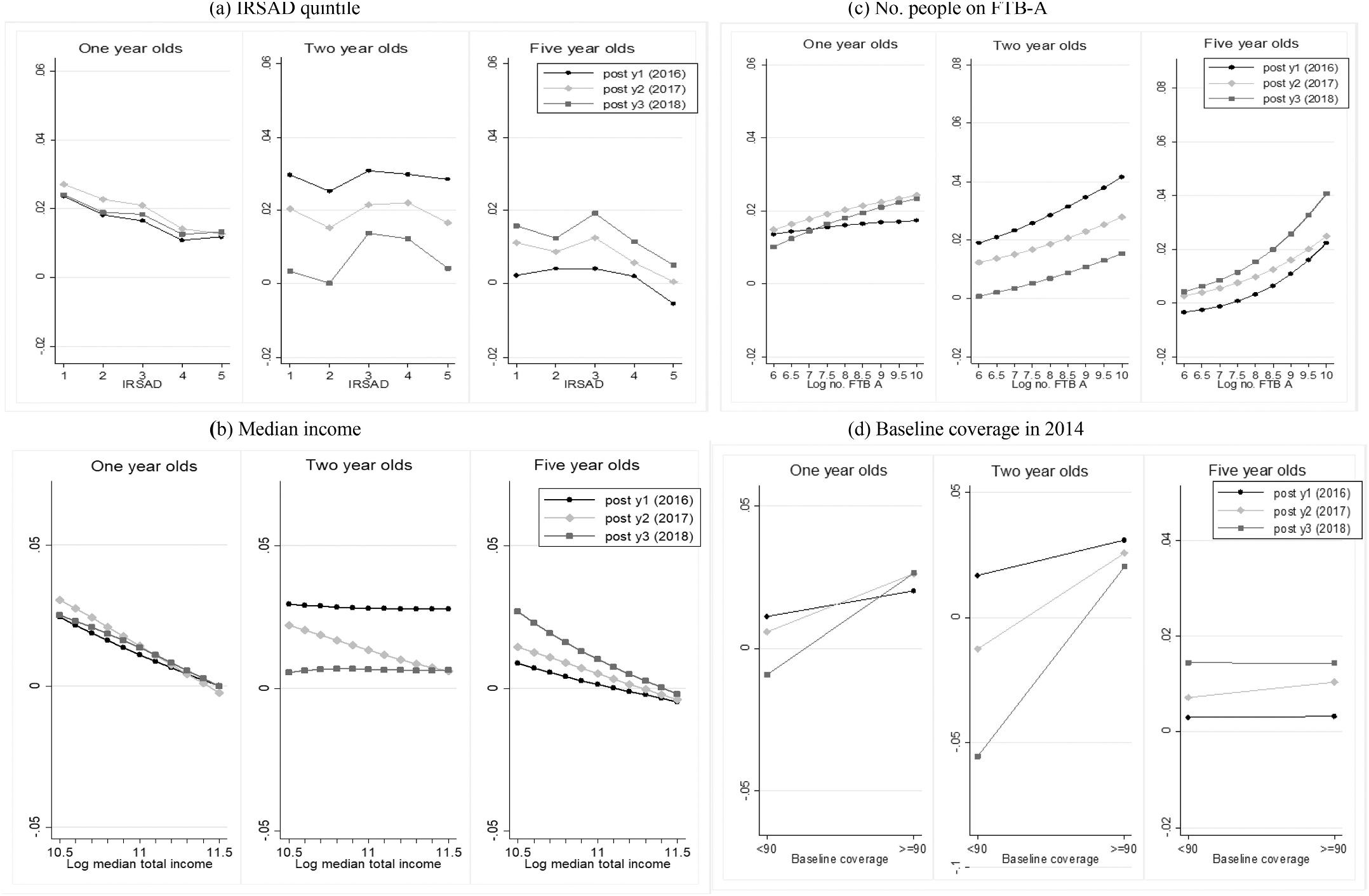

Considering the concentration of recorded objection in more advantaged areas (Beard et al., 2016), the greater effects of the policies on lower-income families (Leask and Danchin, 2017), and the persistent geographic clusters of recorded objection (Beard et al., 2017), the policy response likely varied. The policy response heterogeneity was therefore examined according to area socioeconomics, median income, numbers of FBT-A recipients, and baseline coverage.

Fig. 3 panel (a) examines the overall policy effects on the full vaccination coverage by area socioeconomic status measured by the IRSAD. The increase in coverage associated with the policies was smallest in the highest IRSAD quintile (most affluent and educated) for one and five years olds, and in the second IRSAD quintile for two year olds.12 Overall,

12 Note that the mean of full vaccination coverage rates was highest in the second quintile. The difference in coverage changes across the quintiles are not significant for one year olds.

Table 4

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage for five years olds. DTP Polio MMR Fully

VIC Post y1 vs pre 0.004 0.005* 0.003 0.003 (0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003)

Post y2 vs pre 0.007* 0.007* 0.016*** 0.008* (0.004) (0.004) (0.004) (0.004)

Post y3 vs pre 0.009* 0.009** 0.014*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.005)

QLD Post y1 vs pre 0.010*** 0.010*** 0.008** 0.008** (0.003) (0.003) (0.004) (0.004)

Post y2 vs pre 0.022*** 0.021*** 0.034*** 0.025*** (0.004) (0.004) (0.004) (0.004)

Post y3 vs pre 0.022*** 0.023*** 0.030*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.005)

NSW Post y1 vs pre 0.003 0.003 0.002 0.003 (0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.003)

Post y2 vs pre 0.004 0.003 0.014*** 0.007* (0.004) (0.004) (0.004) (0.004)

Post y3 vs pre 0.005 0.004 0.012*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.004)

WA Post y1 vs pre 0.000 0.001 0.003 0.001 (0.004) (0.004) (0.005) (0.004)

Post y2 vs pre 0.001 0.001 0.019*** 0.004 (0.006) (0.006) (0.006) (0.006)

Post y3 vs pre 0.002 0.001 0.011 (0.008) (0.008) (0.008)

SA Post y1 vs pre 0.013*** 0.013*** 0.017*** 0.014*** (0.005) (0.005) (0.006) (0.005)

Post y2 vs pre 0.015** 0.014** 0.033*** 0.019*** (0.006) (0.006) (0.006) (0.006)

Post y3 vs pre 0.018** 0.017** 0.027*** (0.008) (0.008) (0.008)

TAS Post y1 vs pre 0.006 0.005 0.006 0.003 (0.005) (0.006) (0.006) (0.006)

Post y2 vs pre 0.001 0.000 0.006 0.001 (0.009) (0.009) (0.007) (0.010)

Post y3 vs pre 0.002 0.000 0.006 (0.009) (0.010) (0.010)

NT Post y1 vs pre 0.023* 0.024* 0.019 0.024* (0.013) (0.013) (0.015) (0.014)

Post y2 vs pre 0.029** 0.032** 0.009 0.023* (0.012) (0.013) (0.018) (0.013)

Post y3 vs pre 0.059* 0.064** 0.044* (0.031) (0.032) (0.026)

ACT Post y1 vs pre 0.001 0.001 0.001 0.004 (0.007) (0.008) (0.008) (0.007)

Post y2 vs pre 0.003 0.003 0.017 0.005 (0.013) (0.014) (0.012) (0.012)

Post y3 vs pre 0.004 0.000 0.000 (0.022) (0.021) (0.019)

Other covariates Yes Yes Yes Yes

States, quarters, trends Yes Yes Yes Yes

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. AMEs times 100% give percentage points. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%.

coverage rates were less responsive in more socioeconomically advantaged areas.

Fig. 3 panel (b) shows the policy effects on the full vaccination coverage by logarithmised SA3-level median total income.13 Consistent with the findings for IRSAD gradients, the policy effects generally decreased as the level of median income increased. While the increase in coverage following removal of conscientious objection was around 3 percentage points for areas with the lowest median income, the increase was nearly zero for areas with the highest median income.14 Similarly, the policy effects were insignificant in affluent areas.

Policy effect estimates by the number of FTB-A recipients are

reported in Fig. 3 panel (c).15No Jab No Pay policy linked childhood immunisation to FTB-A supplements (2016–17) and FTB-A (2018-current). Thus, there may be an interaction effect between the policy and the number of FBT-A cases on coverage. It shows that the effect of the policies increased as more people on FTB-A were in the area for one, two and five year old cohorts.

Fig. 3 panel (d) presents the policy responses separately for SA3s with baseline pre-policy annual coverage in 2014 below and above 90%. The largest proportion of low baseline coverage occurred in the highest quintile of the IRSAD, followed by the fourth, third, first, and second quintiles. The increase in areas with baseline coverage above 90% was larger than that in areas with baseline coverage below 90%, and the positive policy effects mostly occurred in areas with higher baseline coverage. That is, the increase in immunisation coverage has been largely driven by SA3s with relatively higher baseline coverage, which tend to be socioeconomically disadvantaged areas.

4. Discussion

The present study examines the associated impact of removing conscientious objection exemptions from children vaccination requirements for access to family assistance payments (No Jab No Pay in 2016), enrolment in childcare (No Jab No Play in VIC and QLD in 2016 and NSW in 2018), and tightened documentation requirements for childcare enrolment (WA in 2016 and SA in 2017). Overall, the results indicate that removing philosophical or religious exemptions was associated with increases in the vaccination coverage at one (approx. 2–4%), two (approx. 1–1.5%) and five (approx. 1–3.5%) years of age. There have been overall improvements in coverage associated with No Jab No Pay, and states that implemented additional No Jab No Play and tightened documentation requirement policies tended to show more significant increases.

Similar to the order of magnitude in this study, studies in the United States examining the removal of nonmedical exemptions from school entry requirements in California found an increase of nearly 3% in kindergartener vaccination coverage in the first year, and a slight decrease of 0.45% in the second year (Bednarczyk et al., 2019; Delamater et al., 2019). The stabilisation of post-implementation trends has also observed for the one and two years olds. The increase in the coverage of five years olds was more persistent and largely driven by MMR, which has been one of the most controversial vaccines since a fraudulent study linked MMR with autism.

However, the policy response was heterogenous. The changes in immunisation coverage post removal of conscientious objection was greatest in areas that were more socioeconomically disadvantaged, more government benefit dependent, with lower median income, and with higher baseline coverage. The policies disproportionally affected lower income families who were less likely to be vaccine objectors (Leask and Danchin, 2017) and have less means to arrange other informal childcare (Helps et al., 2018; Leask and Danchin, 2017). Contrastingly, the improvement in immunisation coverage was smallest in more socioeconomically advantaged areas with lower baseline coverage. Smaller improvement in these areas indicates that low immunisation coverage has been persistent at some local areas.

13 The mean median income is $AU 49,517 with a range of 34,457-92,416. 14 Note that most policy estimates show significance for two and five years olds.

Non-immunising parents are broadly comprised of refusing and hesitant parents who tend to be socioeconomically advantaged and accepting parents who experience access barriers (Pearce et al., 2015; Toll and Li, 2020). The results imply that the areas with large proportions of motivated or persistent vaccine objectors who are affluent tend to have more persistently low vaccination and be less responsive to the elimination of conscientious objection. However, the areas with largely accepting parents whose access issues have not been improved by the policies will also have smaller responsiveness, depending on the size of the policy nudge relative to the barriers they face. These results imply that targeted

15 The mean number of FTB-A recipients is 4950 with a range of 591–19,450.

3. Effects of immunisation policies on full vaccination coverage rates by subgroups.

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link for full immunisation at 1, 2 and 5 years olds are estimated. AMEs on the overall post policy indicators are displayed. AMEs times 100% give percentage points.

strategies, accordant with different causes of under-vaccination, at the national or local area level might be needed to reach persistent noncompliers and reduce risks of local outbreaks.

The study contributes to the literature on the effectiveness of mandatory immunisation policies, including financial sanctions and childcare entry requirements. Australia is among the first few jurisdictions implementing regulations that remove non-medical exemptions to childhood immunisation requirements. With more countries moving towards implementing vaccination mandates, evidence from Australia can assist effective policy designs to achieve high vaccination coverage. Currently, there is a paucity of evidence on mandatory immunisation in high-income regions with relatively high baseline rates (MacDonald et al., 2018). A recent systematic review identifies a gap in studies around immunisation mandates for childcare entry (Lee and Robinson, 2016).

This study provides empirical evidence on the effectiveness of removing conscientious objection exemptions from vaccination requirements linked to receipt of family assistance payments and/or childcare enrolment. The investigation of vaccination coverage was conducted for a range of scheduled vaccines at one, two and five years of age across areas implemented with the policies. One of the key caveats is that the variation in policy effects needs to be considered when implementing mandatory immunisation programs. Given vulnerable families often support vaccination (MacDonald et al., 2018) and many areas with low coverage have been persistent, future immunisation programs can be more

effective if efforts are put in place to diagnose causes of under-vaccination in areas with low coverage and small policy responses, and tailor accordant interventions for for groups or areas with persistent non-compliance.

The study has a few limitations. First, ITS approaches assume that pre-existing trends continue unchanged without the intervention. The availability of counterfactual controls for No Jab No Pay would provide more robust causality inference. Second, while the specification controls for national and state-level time trends and state and quarter fixed effects, there might be some time-varying smaller-scale effects such as client reminder and recall systems, home visits, and campaigns that cannot be separated out from the main policy effects. Third, the study did not assess the effectiveness of the policies separately for parents who are refusing, hesitant, or facing access barriers that require individuallevel data, which would inform more targeted strategies to improve coverage. Fourth, there have been changes in coverage definitions, such as the inclusion of Pneumococcal in December 2013, DTP in March 2017, and MMR and Varicella in December 2014. For these vaccines, the coverage changes post definition revision are mixed with policy effects, although the results using only post definition period and findings for other vaccines are similar.16

5. Conclusion

There has been an improvement in immunisation coverage with implementation of vaccine mandates that remove conscientious

16 In the robustness checks, results for Varicella and MMR using only data after 2015 confirm similar findings (see Appendix B).

Fig.

objection from vaccination requirements for government payments and childcare enrolment. Australia has a high childhood vaccination rate, compared globally, but community immunity is contingent on high coverage to reduce transmission risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Results suggest removing conscientious objection is a policy lever that improves vaccine coverage. However, more effective strategies require an investigation of differential policy effects on vaccine hesitancy,

Appendix A

Table A1

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage rates at the national level.

One year olds

refusal and access barriers, and a diagnosis of causes for lack of response and under-vaccination in areas with persistently low coverage.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Five years olds

Two years olds

quarters, trends

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link for full immunisation at 1,

AMEs on the overall post policy indicators are displayed. AMEs times 100% give percentage points.

Table A2

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage rates for one year olds.

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AME and robust standard error are reported. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%. The models with and without allowing different slopes before and after 2016 had similar results.

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage rates for two years olds.

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. Significant at ***1% **5% and *10%.

Table A4

Effects of immunisation policies on coverage rates for five years olds.

(continued on next page)

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%. The models with and without quadratic trends had similar results.

Appendix B

A series of sensitivity checks are performed to check the robustness of the model specification (Table B1). First, the estimation is applied to a sample containing non-mapped SA3s (column (1)). For this specification, regional variables are not included because these SA3s with no identification codes cannot be matched with the ABS data. Second, the estimation is limited to a sample of SA3s observed consistently for 20 quarters from January 2014 to December 2018 to check the influence of areas with small population (column (2)). Third, the interaction between post-policy indicators, state or territory indicators, and linear trends are included to allow for changes in trends during post-implementation period for different states and territories (column (3)). Fourth, state or territory-level time trends are replaced with SA3-level time trends to allow time trends to vary for different SA3s (column (4)). Fifth, a fixed effect regression is modelled to remove time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity among SA3s (column (5)). Estimations using these specifications produce similar results.

Sixth, the coverage for MMR at two years of age is modelled using the data starting from January 2015 and April 2015 respectively, after the coverage measure amendment in September–December 2014, to obviate the effect of definition changes (column (6)). The estimates are slightly smaller using April 2015 and onwards. Seventh, weights derived from the synthetic control method are applied to states and territories at different age groups to test the effect of No Jab No Play in VIC (column (7)), NSW (column (8)) and QLD (column (9)) using counterfactual controls with similar preintervention characteristics. This approach allows identification of a combination of control units that most closely resembles implemented units. SA, WA, TAS, NT and ACT without No Jab No Play in place are adopted as the donor pool for the evaluation of No Jab No Play for VIC and QLD in 2016 and for NSW in 2018. Regional factors, age-appropriate population, and coverage rates over the pre-intervention period are used as predictor variables. Similarly, the results show that NSW, VIC and QLD have extended policy effects at five years of age. An estimation using NT as the control unit for tightened documentation requirements in WA and SA shows that there is no significant difference between WA or SA and NT, except that SA has larger increases than NT for the five-year-old cohorts (results not shown).

Robustness checks on effects of immunisation policies on full vaccination coverage rates.

Covariates

Table B1

Robustness checks on effects of immunisation policies on full vaccination coverage rates (cont.)

Covariates

Notes: Generalised linear models with a logit link are estimated. AMEs and robust standard errors are reported. AMEs times 100% give percentage points. Significant at ***1%, **5% and *10%.

References

ABS, 2016a. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 1 - Main Structure and Greater Capital City Statistical Areas cat. no. 1270.0.55.001

ABS, 2016b. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Cat.no. 2033.0.55.001. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Andre, F.E., Booy, R., Bock, H.L., Clemens, J., Datta, S.K., John, T.J., Lee, B.W., Lolekha, S., Peltola, H., Ruff, T.A., Santosham, M., et al., 2008. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull. World Health Organ. 86 (2), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.040089

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017. Healthy Communities: Immunisation rates for Children in 2015-16 (doi:https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/ immunisation/immunisation-rates-for-children-in-2015-16/data)

Beard, F.H., Hull, B.P., Leask, J., Dey, A., McIntyre, P.B., 2016. Trends and patterns in vaccination objection, Australia, 2002–2013. Med. J. Aust. 204 (7), 275 Beard, F.H., Leask, J., McIntyre, P.B., 2017. No Jab, No Pay and vaccine refusal in Australia: the jury is out. Med. J. Aust. 206 (9), 381–383 Bednarczyk, R.A., King, A.R., Lahijani, A., Omer, S.B., 2019. Current landscape of nonmedical vaccination exemptions in the United States: impact of policy changes. Exp. Rev. Vacc. 18 (2), 175–190

Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. No Jab, No Pay lifts immunisation rates. In: Media Release by The Hon Christian Porter MP, 31 July 2016 (doi:https://formerministers. dss.gov.au/17462/no-jab-no-pay-lifts-immunisation-rates/)

Delamater, P.L., Pingali, S.C., Buttenheim, A.M., Salmon, D.A., Klein, N.P., Omer, S.B., 2019. Elimination of nonmedical immunization exemptions in California and schoolentry vaccine status. Pediatrics 143 (6) Department of Health, 2007. Immunisation Coverage Annual Report (doi:https://www1. health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-cdi3302c.htm) Department of Health, 2018. National Vaccine Objection (conscientious objection) Data. Australian Immunisation Register (doi:https://www.health.gov.au/resources/ publications/national-vaccine-objection-conscientious-objection-data-1999-to2015)

Department of Health, 2019a. Childhood Immunisation Coverage. Department of Health, Australian Government. Department of Health, 2019b. National Immunisation Program Schedule. Department of Health, Australian Government doi:https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/ immunisation/immunisation-throughout-life/national-immunisation-programschedule#what-is-the-nip-schedule

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

exuberance of my nature, unless it be at the same time the physical need of repairing by a fast from words, by abstinence from outcries and gestures, the terrible waste which the southerner makes of his whole being. Be that as it may, I owe a great deal to those places of refuge for the mind; and no one of them has been more salutary in its effect upon me than that old mill in Provence.”

Here, both in boyhood and in young manhood’s revisitations, Daudet found the “grasshopper’s library,” and in its secret alcoves discovered such delightful stories as “The Elixir of the Reverend Father Gaucher,” “The Three Low Masses,” “The Goat of Monsieur Seguin,” “Master Cornille’s Secret,” and “The Old Folks,” all abounding in naïve character and told with his own delicate charm. Here, too, he learned to take a delight in his craft which waned not with the years; and to find joy in pleasing “the people,” who were ever the subjects of his finest delineations.

Born at Nîmes in 1840, and as a mere lad leaving home for the city of Lyons, Daudet’s public career began with his journey to Paris in November, 1857. The boy of seventeen and a half came possessed of a slender collection of poems which, though the product of so youthful a rhymester, met with no little favor. In manner common to those who must win their way along the precarious paths of letters, he pressed on, until in 1859—he being not yet twenty—Daudet published his first volume of poems, Les Amoureuses, which won high praise from the critics, but is now sought chiefly by collectors. Thus he began to gain confidence, and others of his works followed almost yearly. The pages of Le Figaro were now freely opened to him, and that public by whom he never ceased to be loved began to scan its columns for his fantastic chronicles of Provençal life. In that same journal he began in 1866 to publish his Letters from My Mill, which were collected in volume form in 1869, and constituted his first real popular triumph.

The third period in our author’s life is marked by the sad experiences of the Siege of Paris, in 1870. Just as his life in the south inspired the Letters, so did the grave impressions made by those terrible

days in the French capital during the Franco-Prussian War move him to write the little masterpieces which, in part, appeared in the volume entitled MondayTales, published in 1873. Who that has read them can forget the “piercing pathos” of “The Last Class” and “The Siege of Berlin”? Not only are these human episodes of singularly tender appeal, but they are masterpieces of form, unsurpassed among short-stories of any language. As Daudet’s best work, they deserve further notice here.

At the close of the Franco-Prussian War, Alsace and Lorraine were ceded to Germany by France. One of the edicts issued by the conquerors, with a view to nationalizing the acquired territory, was that the French language should no longer be taught in their public schools. And this furnishes the motiffor Daudet’s “The Last Class.”

The story is simply told in the first person by Frantz, a little Alsatian. Frantz recalls that historic day when he set off for school a little late. Hoping that he might perhaps escape the teacher’s ferrule, he cuts across the public square without even stopping to find out the meaning of the knot of perturbed villagers who are discussing an announcement upon the bulletin board in front of the mayor’s office. As he slips into his seat, hoping to escape observation, he is impressed by the unnatural quiet in the school-room, and also by the presence of a number of the town notables, all solemnly garbed in holiday dress.

The lad marvels that he is not even chided for his lateness, and is more than ever mystified as the schoolmaster proceeds with one lesson and another, all under stress of deep emotion.

By and by the schoolmaster tells his pupils of the cruel edict, and Frantz begins to realize that the worthy master will no longer rule in his accustomed place. He becomes conscious of neglected work, and a whole tide of better resolutions surges in his breast. Finally the master has heard the last class and arising seeks utterance for his farewells. At first he is able to give his pupils some sound advice, but at length no words will come, and with such quiverings of lip as even Daudet tries not to depict, he chokes, swiftly turns to the

blackboard, takes a piece of chalk, and, bearing with all his might, dashes off his final expression of patriotic protest and personal sorrow:

VIVE LA FRANCE!

“Then he stood there, with his head resting against the wall, and without speaking, he motioned to us with his hand:

“'That is all; go.’”

On rereading “The Last Class” for the dozenth time, I find that it is surrounded with an emotional atmosphere which, textually, the story does not contain. I think this must be the aura emanating from the spirit of the story; for a great work of fiction is not only the product of emotion, but it kindles emotion, because it is a creation, an entity, a living being. Doubtless the contention could not be demonstrated that, when properly received, a great work of fictional art will arouse the same emotions in the reader as were first enkindled in the breast of its author when the story was born. None the less, I believe it to be true. What feelings, then, must Daudet have known when he gave forth this little master-story! It must be these that I myself feel, for I do not, by analysis, find them all present in the text, even by suggestion. Happy artist, who can so project the creations of his soul that they henceforth live and expand and communicate their messages to multitudes to him unknown! So all great fiction is alive; so lives the work of Alphonse Daudet.

The emotion in “The Siege of Berlin” is of a different type. It, too, finds its motif in the Franco-Prussian War; this time in the Siege of Paris itself.

An invalided old cuirassier of the First Empire, Colonel Jouve, lies in his room in the Champs-Élysées, fronting the Arc de Triomphe. Day by day his grand-daughter brings to him news of the progress of the war. So fully is his life wrapped up in the success of the French armies that, in order to brighten his closing days, they tell him fictitious stories of his compatriots’ success. But one day, when the enemy’s lines have drawn close about the beleaguered capital and

the end is at hand, it becomes difficult to deceive the old soldier any longer. Still, fresh victories are always supplied by the news-bureau of love, and the old man can scarcely wait for the homecoming of the victorious battalions. So when one day the sound of bugle and drum is heard, and the tramp of marching feet beneath the windows of the upper room, you can picture the delight of this old veteran. With a superhuman effort he leaves his bed and looks out of the window—only to see the Prussian troops instead of the cheering cohorts of his countrymen! And in this last pang of disappointment, the old man dies.

Both of these stories end with the note of disappointment and consequent sorrow. Poe has declared that the tone of beauty is sadness, and surely there is a penetrating beauty as well as a thrill of sublimity in the sadness of these wonderfully-wrought episodes. Here may be seen the beginnings of the realistic method which Daudet later adopted. Yet, as these stories both indicate, he still carried with him the romanticism of his earlier inspirations, untouched by either the too painful naturalism or the sentimentality of some of his later stories.

In still greater contrast than either of these to the other is the story of our present translation, “The Pope’s Mule.” Here are all the joyous satire, the rollicking fun-making, and the picturesque description, of this unexcelled interpreter of southern life. Daudet’s wit and humor, characterization and description, local color, kaleidoscopic pageantry, are at their best, with never a thought of enforcing a moral or of sounding any emotion deeper than that of boyish amusement. It is the creator of Tartarin who now writes, and not the later master of the novelist’s art.

Notwithstanding the success of the fecund and versatile author of Sapho, as a playwright, and his much wider vogue as a novelist, I wonder if after all he did not love best his short-stories and prose fantasies. In his greatest real novels, Froment, Jr., and Risler , Sr.; Jack; TheNabob; KingsinExile; and NumaRoumestan, the episode

often occurs, of which literary form some further words will be said in the treatment of Loti.

Such a temperament as Daudet’s, both introspective and finely sensitive to the impressions of his surroundings, would naturally make much of his fiction biographical, and even autobiographical. Indeed, a close study of his works, read in the light of his life, shows how he has woven into his stories many personal facts. In that exquisite child-document Little What’s-His-Name, we have a rather full record of his boyhood and entrance into Paris. Jack, also, is full of his own early sorrows, while one character after another may be traced to folk whom he knew. His mind, and his heart too, were note-books on which he was always transcribing his impressions of life, and—here is the vital thing, after all—recreating them for use in his own inimitable way.

So Daudet was not an extreme realist—scarcely a typical realist at all —for while he used the realistic method for observation and faithful record, he no more got beyond sympathizing with his characters than did Dickens, to whom more than to any other English-writing novelist he must be compared. Daudet “belonged” to no school, expounded no theories, stood for no reforms. He was just a kindly, humorous, sympathetic, patiently exact maker of fascinating fictions, and as such we shall love him quite in the proportion that we know him. Life, as he saw it, was full of sadness, but that did not make him conclude it to be not worth the living. Happily married, he knew the solaces of home life. Unlike Maupassant, “What’s the use!” was far from being the heart of his philosophy. Disenchanted with life he never was. A disheartening view of sordidness, vice, and misery left him still with open eyes, for he would not close them against truth; but it never prevented his turning his gaze upon the beautiful, the humorous, and the good—a lovable trio ever!—and finding in them some healing for his hurt.

THE POPE’S MULE (LAMULEDUPAPE)

By Alphonse Daudet

DoneintoEnglishbytheEditor

Of all the pretty sayings, proverbs, or adages with which our Provence peasants embroider their discourse, I know none more picturesque or singular than this: within fifteen leagues around about my mill, whenever a person speaks of a spiteful, vindictive man, he says, “That man there—look out for him! He is like the Pope’s mule, who kept her kick in waiting for seven years.”

I hunted diligently for a long time to find out whence that proverb could have come, what was that papal mule, and that kick reserved throughout seven years. No one here has been able to inform me on this subject, not even Francet Mamaï, my fife player, though he has all the Provençal legends at his fingers’ ends. Francet thinks with me that it must be founded upon some old tradition of Provence; yet he has never heard it referred to except in this proverb.

“You will not find that anywhere but in the Library of the Grasshoppers,” said the old fifer to me, with a laugh.

The idea struck me as a good one, and since the Library of the Grasshoppers is at my door, I went and shut myself up there for a week.

It is a marvellous library, admirably equipped, open to poets day and night, and attended by little librarians who constantly make music for you with cymbals. There I passed some delicious days, and, after a week of research—on my back I ended by discovering what I wished to know, that is to say, the history of my mule and of that famous kick saved up for seven years. The story is a pretty one, although a trifle naïve, and I am going to try to tell it you just as I read it yesterday morning in a sky-colored manuscript, which smelled delightfully of dry lavender, and had long gossamer threads for binding threads.

He who has never seen the Avignon of the time of the Popes, has seen nothing. For gayety, for life, for animation, for a succession of fêtes, there never was a city its equal. From morning till night there were processions and pilgrimages; streets strewn with flowers and hung with rich tapestries; cardinals arriving by the Rhône, banners flying, galleys bedecked with flags; papal soldiers chanting in Latin on the public squares; begging friars with their alms-rattles; then, in addition, from roof to cellar of the houses which swarmed humming around the great papal palace like bees about their hive, there were heard the tic-tacof the lace-makers’ looms, the flying of the shuttles weaving cloth-of-gold for vestments, the little hammers of the vasesculptors, the keyboards being attuned at the lute-makers’, the songs of the warpers; and, overhead, the booming of the bells was heard, and always below sounded the tinkle of the tambourines on the river bank by the bridge. For with us, when the people are happy they must be dancing, dancing ever; and since in those days the streets in the city were too narrow for the farandole, fifers and tambourine players took up their post upon the Avignon Bridge, in the cool breezes of the Rhône, and day and night they danced and danced.... Ah! happy time, happy city, when halberds did not wound, and state prisons were used only for cooling wine! No famine; no wars! That shows the way the Popes of the Comtat[11] knew how to govern their people; that is why their people regretted them so deeply!

There was one Pope especially, a good old gentleman whom they called Boniface. Ah! how many tears were shed for him in Avignon when he died! He was such an amiable, affable prince! He would smile down at you so genially from his mule! And when you passed him—whether you were a poor little digger of madder or the grand provost of the city—he would give you his benediction so courteously! A genuine Pope of Yvetot was he, but of an Yvetot in Provence, with something sly in his laughter, a sprig of sweet marjoram in his cap—and not the semblance of a Jeanneton. The only Jeanneton the good Father had ever been known to have was his vineyard—a little vineyard which he had planted himself, three leagues from Avignon, among the myrtles of Château-Neuf.

Every Sunday, on going out from vespers, the worthy man went to pay his court to it, and when he was seated in the grateful sun, his mule close beside him, his cardinals stretched at the foot of the vine stocks all about, then he would order a flagon of wine of his own bottling—that exquisite, ruby-colored wine, which has been called ever since Château-Neuf of the Popes—and he would drink it appreciatively in little sips, and regard his vineyard with a tender air. Then—the flagon empty, the day closed—he would return joyously to the city, followed by all his chapter; and, after crossing the Bridge of Avignon, in the midst of drum-beats and farandoles, his mule, stirred by the music, took up a little skipping amble, while he himself marked the time of the dance with his cap a thing which greatly scandalized his cardinals, but caused all the people to say, “Ah! that good prince! Ah! that fine old Pope!”

Next to his vineyard at Château-Neuf, the thing that the Pope loved best in the world was his mule. The good old man doted on that beast. Every evening before going to bed he went to see if her stable was well shut, if nothing was lacking in the manger; and he never rose from the table without having had prepared under his very eyes a huge bowl of wine àla Française, with plenty of sugar and spice, which he himself carried to the mule, despite the remarks of his cardinals. It must be admitted, however, that the animal was worth the trouble. She was a beautiful mule, black and dappled with

red, glossy of coat, sure of foot, large and full of back, and carrying proudly her neat little head, all decked out with pompons, rosettes, silver bells, and bows of ribbon—all this with the mildness of an angel, a naïve eye, and two long ears, always in motion, which gave her the air of an amiable child. All Avignon respected her, and when she went through the streets there was no attention which she did not receive; for everyone knew that this was the best way to be in favor at court, and that, for all her innocent air, the Pope’s mule had led more than one to fortune—witness Tistet Védène and his prodigious adventure.

This Tistet Védène was, from the very first, an audacious young rascal whom his father, Guy Védène, the gold-carver, had been obliged to drive from home because he would not do anything, and demoralized the apprentices. For six months he could be seen trailing his jacket through all the gutters of Avignon, but especially around the papal palace, for this rascal had long had his eye fixed on the Pope’s mule, and you will see what a villainous scheme it was. One day when his Holiness was taking a walk all alone beneath the shadows of the ramparts with his steed, behold my Tistet approached and, clasping his hands with an air of admiration, said to him:

“Ah! mon Dieu! what a splendid mule you have there, Holy Father! Permit me to look at her a moment. Ah, my Pope, the emperor of Germany has not her equal!”

And he caressed her and spoke softly to her, as to a damsel.

“Come here, my jewel, my treasure, my fine pearl....”

And the good Pope, deeply moved, said to himself:

“What a good little fellow! How gentle he is with my mule!”

And do you know what happened the next day? Tistet Védène exchanged his old yellow jacket for a beautiful vestment of lace, a violet silk hood, and buckled shoes; and he entered the household of the Pope, where never before had any been received but sons of

nobles and nephews of cardinals. There is an intrigue for you! But Tistet did not stop there.

Once in the service of the Pope, the rascal continued the game which had succeeded so well. Insolent with everyone else, he had nothing but attention, nothing but provident care for the mule; and one was always meeting him about the palace court with a handful of oats or a bunch of clover, whose rosy clusters he shook gently and glanced at the balcony of Saint Peter as if to say: “Ha! for whom is this?” And so it went on until the good Pope, who felt that he was growing old, ended by leaving it to him to watch over the stable and to carry to the mule her bowl of wine àlaFrançaise—which was no laughing matter for the cardinals.

No more was it for the mule—it did not make her laugh. Now, at the hour for her wine, she always saw coming to her stable five or six little clerks of the household, who hastily buried themselves in the straw with their hoods and their laces; then, after a moment, a delicious warm odor of caramel and spices filled the stable, and Tistet Védène appeared carefully carrying the bowl of wine à la Française. Then the martyrdom of the poor beast began.

That perfumed wine which she loved so well, which kept her warm, which gave her wings, they had the cruelty to place before her, there in her manger, and let her sniff it; then, when she had her nostrils full of it, it was gone—that lovely rose-flamed liquor all went down the gullets of those good-for-nothings. And yet if they had only stopped at taking her wine; but they were like devils, all these little clerks, when they had drunken. One pulled her ears, another her tail; Quinquet mounted himself upon her back, Béluguet tried his cap on her, and not one of those little scamps reflected that with a single good kick that excellent beast could have sent them all into the polar star, and even farther. But no! It is no vain thing to be the Pope’s mule, the mule of benedictions and indulgences. The children went blithely on, she did not get angry; and it was only against Tistet Védène that she bore malice. But that fellow, for instance, when she felt him behind her, her hoof itched, and truly she had excellent

reason. That ne’er-do-well of a Tistet played her such villainous tricks! He had such cruel fancies after drinking!

One day he took it into his head to make her climb up with him into the clock tower, all the way up to the very top of the palace! And it is no myth that I am telling you—two hundred thousand Provençals saw it. Imagine for yourself the terror of that unhappy mule when, after having for a whole hour twisted like a snail blindly up the staircase, and having clambered up I know not how many steps, she found herself all at once on a platform dazzling with light, and saw, a thousand feet beneath her, a fantastic Avignon: the market booths no larger than walnuts, the papal soldiers before their barracks like red ants, and farther down, over a silver thread, a microscopically little bridge on which the people danced and danced. Ah! poor beast! What panic! At the bray she uttered all the windows of the palace trembled.

“What’s the matter? What are they doing to her?” cried the good Pope, and rushed out upon the balcony.

Tistet Védène was already in the courtyard, pretending to weep and tear out his hair.

“Ah! Holy Father, what is the matter? There is your mule.... Mon Dieu! what will happen to us! Your mule has gone up into the belfry!”

“All by herself?”

“Yes, Holy Father, all by herself. Stay! Look there, up high. Don’t you see her ears waving? They look like two swallows.”

“Mercy on us!” cried the poor Pope on raising his eyes. “But she must have gone mad! Why, she will kill herself. Will you come down, you unhappy creature!”

Pécaïre! She could have asked nothing better than to come down; but how? The stairs—they were not to be thought of: one could mount those things, but as to coming down, one could break one’s legs a hundred times. And the poor mule was disconsolate; but as

she roamed about the platform with her great eyes filled with vertigo she thought of Tistet Védène.

“Ah, bandit, if I escape—what a kick tomorrow morning!”

That idea of a kick restored a little courage to her heart; except for that she could not have held out. At last they succeeded in getting her down, but it was not an easy affair. They had to lower her in a litter, with ropes and windlass, and you may imagine what a humiliation it must have been for a Pope’s mule to see herself hanging at that height, afloat with her legs in the air like a beetle at the end of a string. And all Avignon looking on!

The unhappy beast did not sleep that night. It seemed to her as though she were forever turning upon that accursed platform, with the laughter of the city below. Then she thought of that infamous Tistet Védène, and of the delightful kick that she proposed to turn loose the next morning. Ah, my friends, what a kick! They could see the smoke at Pampérigouste.

But, while this pretty reception was being prepared for him at the stable, do you know what Tistet Védène was doing? He was going singing down the Rhône on one of the papal galleys, on his way to the Court of Naples with a company of young nobles whom the city sent every year to Queen Joanna for exercise in diplomacy and in manners. Tistet was not of noble birth; but the Pope desired to recompense him for what he had done for his mule, and above all for the activity he had shown throughout the day of the rescue.

It was the mule who was disappointed the next day!

“Ah, the bandit! He suspected something!” she thought as she shook her bells in fury. “But it’s all the same; go, scoundrel! You will find it waiting for you on your return, that kick I’ll save it for you!”

And she did save it.

After the departure of Tistet, the Pope’s mule once more found her course of tranquil life and her former habits. Neither Quinquet nor Béluguet came again to her stable. The delightful days of wine àla

Française had returned, and with them good-humor, the long siestas, and the little prancing step when she crossed the Avignon bridge. However, since her adventure she was always shown a slight coldness in the city. Folks whispered together as she passed; the old people shook their heads, the children laughed as they pointed to the belfry. Even the good Pope had no longer quite the same confidence in his friend, and whenever he permitted himself to take a little nap on her back on Sundays on returning from his vineyard, this thought always came to him: “What if I should awake 'way up there on the platform!” The mule discerned this and suffered, without saying a word; only, when any one near her mentioned the name of Tistet Védène, her long ears quivered, and with a little laugh she would sharpen the iron of her shoes on the paving.

Seven years passed thus; then at the end of those seven years Tistet Védène returned from the Court of Naples. His time there was not at an end; but he had learned that the Pope’s chief mustardbearer had died suddenly at Avignon, and, since the post suited him well, he had come in great haste in order to apply for it.

When that intriguer of a Védène entered into the great hall of the palace, the Holy Father had difficulty in recognizing him, so tall had he grown, and stout of body. It must be said, too, that the worthy Pope had grown old and could no longer see well without spectacles.

Tistet was not frightened.

“What, Holy Father, you do not remember me any more? It is I, Tistet Védène!”

“Védène?”

“Why, yes, you know very well—the one who used to carry the wine àlaFrançaiseto your mule.”

“Oh—yes—yes—I remember. A good little fellow, that Tistet Védène! And now, what is it that he wants of us?”

“Oh, a very little thing, Holy Father. I came to ask you—by the way, do you still have your mule? And is she well? Ah, so much the

better! I came to ask of you the post of the chief mustard-bearer, who has just died.”

“First mustard-bearer, you! Why, you are too young. How old are you, then?”

“Twenty years two months, illustrious Pontiff, just five years older than your mule. Ah! that excellent creature! If you only knew how I loved that mule! How I languished for her in Italy! Are you not going to let me see her?”

“Yes, my child, you shall see her,” said the good Pope, deeply moved. “And since you loved her so much, that excellent animal, I do not wish you to live apart from her. From this day, I attach you to my person as chief mustard-bearer. My cardinals will raise an outcry, but so much the worse! I am used to it. Come to meet us tomorrow as we return from vespers, we will deliver to you the insignia of your office in the presence of our chapter, and then—I will take you to see the mule, and you shall come to the vineyard with us two—ha! ha! Go along, now!”

If Tistet Védène was content upon leaving the grand hall, I need not tell you with what impatience he awaited the ceremony of the next day. Meanwhile, they had some one in the palace who was still more happy and more impatient than he: it was the mule. From the time of Védène’s return, until vespers on the following day, the terrible creature did not cease cramming herself with oats and kicking at the wall with her hind feet. She too was preparing herself for the ceremony.

Accordingly, on the morrow, when vespers had been said, Tistet Védène made his entrance into the courtyard of the papal palace. All the high clergy were there—the cardinals in red robes, the advocate of the devil in black velvet, the convent abbés with their little mitres, the church-wardens of the Saint-Agrico, the violet hoods of the members of the household, the lesser clergy also, the papal soldiers in full uniform, the three brotherhoods of penitents, the hermits from Mount Ventoux with their ferocious eyes and the little clerk who

walks behind them carrying the bell, the Flagellant Brothers, naked to the waist, the blond sacristans in robes like judges—all, all, down to those who pass the holy water, and he who lights and he who extinguishes the candles—not one was missing. Ah! That was a beautiful installation, with bells, fireworks, sunlight, music, and, as always, those mad tambourine players who led the dance down by the Avignon Bridge.

When Védène appeared in the midst of the assemblage, his imposing deportment and fine appearance called forth a murmur of approbation. He was a magnificent Provençal of the blond type, with long hair curled at the ends and a small unruly beard which resembled the shavings of fine metal from the graving tool of his father, the carver of gold. The report was current that the fingers of Queen Joanna had now and then toyed with that blond beard; and the Sire de Védène had in truth the haughty air and the absent look of those whom queens have loved. That day, to do honor to his nation, he had replaced his Neapolitan garb by a jacket bordered with color-of-rose, in the Provençal fashion, and in his hood trembled a great plume of the Camargue ibis.

As soon as he had entered, the first mustard-bearer bowed with a gallant air, and directed his steps toward the grand dais, where the Pope awaited him in order to deliver to him the insignia of his office: the yellow wooden spoon and the saffron-colored coat. The mule was at the foot of the staircase, all caparisoned and ready to depart for the vineyard. When he passed her, Tistet Védène had a pleasant smile and paused to give her two or three friendly pats upon the back, looking out of the corner of his eye to see if the Pope noticed him. The situation was admirable. The mule let fly:

“There! You are trapped, bandit! For seven years I have saved that for you!”

And she let loose a kick so terrible, so terrible that at Pampérigouste itself one could see the smoke: a cloud of blond smoke in which fluttered an ibis plume—all that was left of the ill-fated Tistet Védène.

Mules’ kicks are not ordinarily so appalling; but then this was a papal mule; and besides, think of it! she had saved it up for seven years. There is no finer example of an ecclesiastical grudge.

PROSPER MÉRIMÉE, IMPERSONAL ANALYST

Among French masters of the short-story, Prosper Mérimée easily holds rank in the first group. Both personality and genius are his, and both well repay scrutiny.

Stendhal has given us a picture of Mérimée as a “young man in a gray frock-coat, very ugly, and with a turned-up nose.... This young man had something insolent and extremely unpleasant about him. His eyes, small and without expression, had always the same look, and this look was ill-natured.... Such was my first impression of the best of my present friends.”

An examination of at least eight several portraits of Mérimée indicates that Stendhal’s picture is far from flattering, yet no one ever charged Mérimée with being pretty.

Our author was born in Paris, September 28, 1803. His father, Jean François, was a cultivated artist and a writer of some ability. While professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, the elder Mérimée married Anne Moreau, a pupil. She was a successful painter of children, and often kept them in quiet pose by telling them stories. Her grandmother, Madame de Beaumont, had long before endeared herself to children of all time by writing “Beauty and the Beast.” The Mérimée home naturally attracted the artists and celebrities of many

lands, so that Prosper was reared in an air of refinement and inspiration.

Versatile from childhood, Mérimée took to drawing like a fine-arts pupil, passed through college, was successful in his law examinations, and at an early age took up literature as a vocation. His career was seconded by many journeys abroad, where he served his country particularly as man of letters, art critic, and archæologist. At home he received important public recognition, notably membership in the French Academy and appointment as a Senator of France. This latter honor evidenced the warm personal esteem of the Empress Eugénie, whom he had known as a girl in Spain, and at whose court—in the reign of Napoleon III—he was received as an intimate rather than as a courtier. Notwithstanding his reticence, everywhere his friends were many and distinguished, for scarcely any other Frenchman ever labored so brilliantly in capacities collateral with literature and yet attained to such a pinnacle of manysided authorship. He died at Cannes, September 23, 1870, lacking five days of rounding out his sixty-seventh year.

Those who would know somewhat of Mérimée’s spirit must read his Letterstoan UnknownWoman—letters covering thirty-nine years of his life. For the first nine years the correspondents never met, but when at length they did, it was to love; and though during the succeeding thirty years the affection cooled, there never failed a solid attachment, and the last letter to his Inconnuewas penned but two hours before his death. True, in these epistles the author is always the literary artist expressing the moods of a man and a lover, and so is never to be taken quite unawares, yet all his traits are disclosed with sufficient openness to show the real man.

And this real man, who was he? An alert student of history, who yet was so fascinated by its anecdotal phases that he cared not at all for the large philosophy of events in sequence; a linguist who early delved into Greek and Latin, knew English well enough to memorize long passages from the poets, spoke Castilian Spanish as well as several dialects, and translated Russian—Pushkin, Gogol, and

Turgenieff—with rare ability; an epicure in travel, keen for the curious and the novel; a connoisseur in art and archæology of sufficient distinction to warrant his appointment as the national “Inspector of Monuments;” a prejudiced scorner of priests and religion, yet bitterly distrustful of his own inner light; an orderly man, systematic even in his indulgences; a pagan in refined sensualism, which he always checked before its claims impinged too largely upon other domains; an aloof spirit, ironical and cold, yet capable of the warm friendship that made Stendhal happy for two days by receiving one of Mérimée’s letters, constant enough to pour out his best at the feet of his Unknown for more than half a lifetime, and so gentle as to crave with the tender heart of a father the love of little children.

The sum of all this is Enigma. We are not sure which is the real man; but this we know: his was a tender, susceptible heart beating under an outer garment of ironical coldness. To love deeply was to endure pain, to follow impulse was to court trouble, to cherish enthusiasms was to delude the mind—so he schooled himself to appear impassive and blasé. How much of this frosty withdrawal was genuine and how much a protective mask, no man can say.

Mérimée’s literary methods reflected his singularly composite personality, yet the author is not apparent in his work. He delighted to tell his tales in the impersonal, matter-of-fact manner of the casual traveller who had picked up a good story and passed it on just as it was told to him.

“They contain,” writes Professor Van Steenderen, “no lengthy descriptions. There are no reflections, dissertations, or explanations in them. They bring out in relief only the permanent features of a given situation, features interesting and intelligible to men of other ages and climes. They are lucid and well constructed. Their plots turn about a simple action with unique effect. Their style is alert, urbane, discreet, and rich, seeking its effect only through concrete and simple means. They deal but very slightly with lyrical emotion, they deal with passions and the will.”