Dedication

Dedicatedto

ProfessorPeteKaiser1964 2016 CoeditorSecondEdition AvianImmunology ValuedAvianImmunologistandSorelyMissedbytheEditorsofthe ThirdEditionof AvianImmunology.

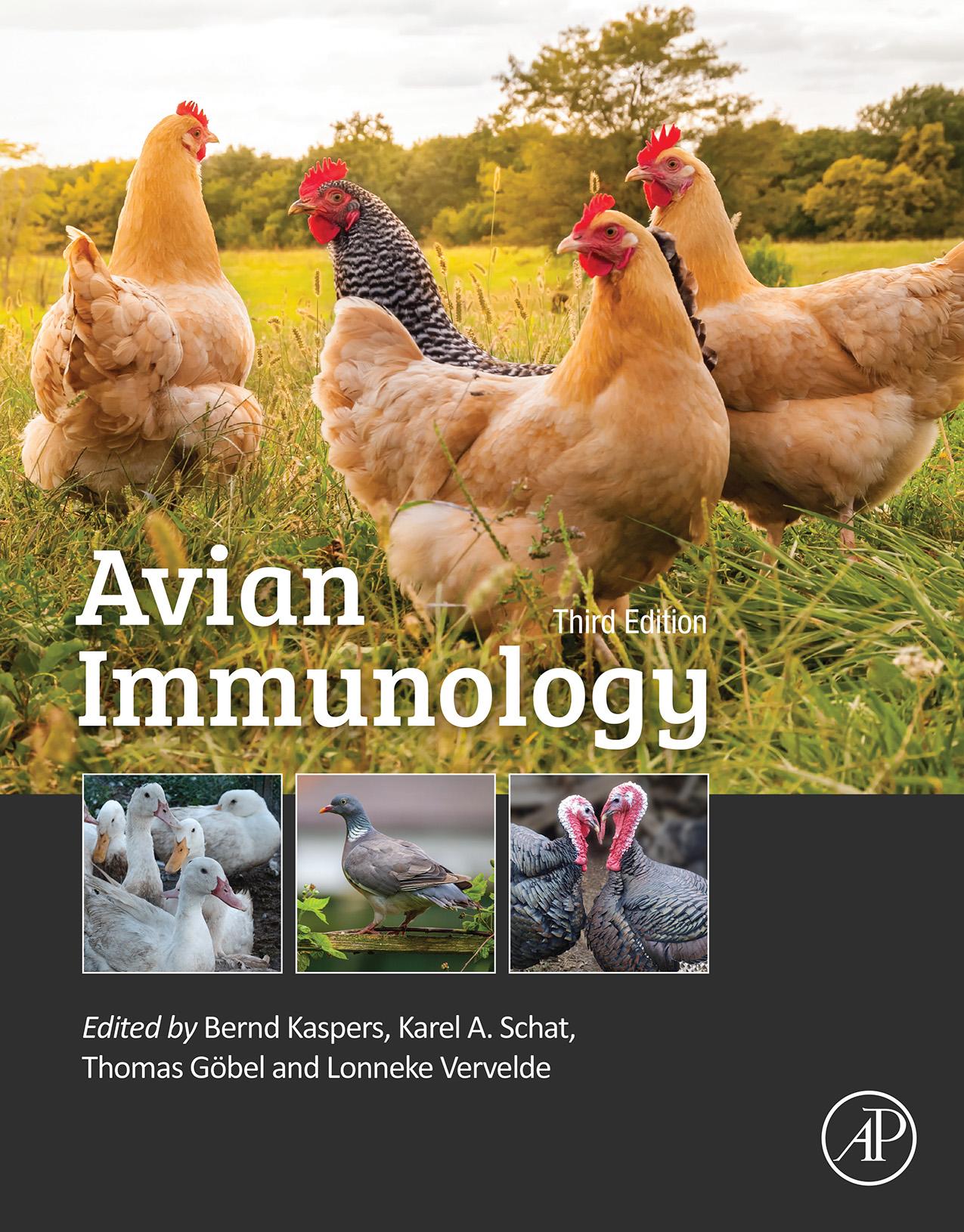

Theimportanceoftheavianimmune systemanditsuniquefeatures 1

1.3ContributionofthebursaofFabricius 2

1.3.1Geneconversionandthebursa4

1.4ThecontributionofthechickenMHC

2.3.11Germinalcenterofthe peripherallymphoidorgans21

2.4Thespleen 22

2.4.1Originandanatomy22

2.4.2Periarteriolarlymphoidsheath25

2.4.3Ellipsoidsandperiellipsoid whitepulp25

2.4.4Themarginal-zoneequivalent andantigenhandling27

2.5Gut-associatedlymphoidtissue 28

2.5.1Follicle-associatedepitheliumor lymphoepithelium30

2.5.2Esophagealandpylorictonsils30

2.5.3Peyer’spatches31

2.5.4Meckel’sdiverticulum31

2.5.5Cecaltonsils32

2.6Harderiangland 33

2.7Murallymphnode 34

2.8Ectopiclymphatictissueandpineal gland 36

2.9Bonemarrow 37

Na ´ ndorNagy,ImreOla ´ hand LonnekeVervelde 2.1Introduction

2.2Thethymus 12

2.2.1Anatomyandhistological organization12

2.2.2Thymiccortex13

2.2.3Thymicmedulla13

2.3ThebursaofFabricius 15

2.3.1Anatomyandhistology15

2.3.2Bursalsurfaceepithelium16

2.3.3Bursalfollicle17

2.3.4Medulla18

2.3.5Bursalmedullaryepithelial cells18

2.3.6Bursalsecretorydendriticcells19

2.3.7Bursalmacrophages19

2.3.8Bursallymphocytes21

2.3.9Cortex21

2.3.10Peripherallymphoidtissueof thebursaofFabricius21

3. Developmentoftheavian hematopoieticandimmune systems 45

LaurentYvernogeau,Na ´ ndorNagy, DominiqueDunon,CatherineRobinand ThierryJaffredo

3.1Introduction 45

3.2Originsandmigrationroutesof hematopoieticcellsusingquail/chicken complementarychimeras 45

3.2.1Lookingforthesourceof hematopoeieticcellsduring development45

3.2.2Macrophageproductionbythe yolksac46

3.2.3TheaorticregionproducesHSCs46

3.3Aorticclustersastheintraembryonic sourceofdefinitivehematopoiesis 46

3.3.1Cellularandmolecular identificationoftheclusters46

3.3.2Theparaaorticfoci46

3.3.3Tracingtheoriginsandfates oftheaorticclusters46

3.4Formationoftheaorta:adorsal angioblasticlineageandaventral hemangioblastslineage 48

3.4.1Twoendotheliallineagesformthe vascularnetworkoftheembryo48

3.4.2Chimericoriginoftheaortic endothelialcells48

3.5Developingan invitro modelof hemogenicendotheliumcommitment andendothelial-to-hematopoietic transition 50

3.6Spatiotemporalemergenceand organizationofthechickenIAHCs 52

3.7Ecsofthelatefetus/youngadultbone marrowharborhemogenicpotential andgeneratemultilineage hematopoiesis 54

3.8Spatialtranscriptomicsinthechicken embryorevealsregulatorsof hematopoiesis 55

3.9TheavianthymusandT-cell development 57

3.9.1Thymicdevelopment57

3.9.2Colonizationofthethymus57

3.9.3T-celldifferentiation57

3.9.4TCRrearrangement58

3.10ThebursaofFabricius,B-cellontogeny, andimmunoglobulins 58

3.10.1Bursaldevelopment58

3.10.2Formationofthebursal epithelialanlage58

3.10.3Hematopoieticcolonization ofthebursalrudimentand folliclebudformation60

3.10.4Developmentofthefollicleassociatedepitheliumandthe follicularcortex62

3.10.5Immunoglobulins63

3.11Lymphocyte-differentiating hormones 63

3.12Developmentoftheimmune responses 64

3.12.1Earlyimmuneresponses64

3.12.2Antibodyisotypeswitching andhypersensitivityreaction64

3.12.3Allograftrejection64

3.13Conclusion

4. Bcells,thebursaofFabricius,andthe generationofantibodyrepertoires 71 MichaelJ.H.RatcliffeandSonjaHartle 4.1Introduction 71

4.2Thegenerationofavianantibody repertoires 71

4.2.1Immunoglobulinlightchains71

4.2.2Immunoglobulinheavychains72

4.2.3GenerationofIgmoleculesby V(D)Jrecombination74

4.2.4GenerationofIgdiversityby somaticgeneconversion75

4.2.5Implicationsofgeneconversion forallelicexclusion77

4.3ThedevelopmentofavianBcells 77

4.3.1PrebursalBcelldevelopment77

4.3.2Colonizationofthebursaby Bcellprogenitors78

4.3.3Colonizationoflymphoid folliclesinthebursa79

4.3.4GrowthofbursalBcellsin bursalfollicles82

4.3.5Developmentofthebursaafter hatch83

4.3.6Roleofcelladhesionmolecules andchemokinesinbursalcell development85

4.3.7Developmentofperipheral Bcellpopulations87

4.3.8ActivationofperipheralBcells89

4.3.9Plasmacelldevelopment90

4.3.10CytokinesinchickenBcell developmentandactivation91

4.3.11ApplicationofBcellcultures92 References 93

5. Structureandevolutionofavian immunoglobulins 101

SonjaHa ¨ rtle,KatharineE.Magor, ThomasW.Go ¨ bel,FredDavisonand BerndKaspers

5.1Thebasicstructureofimmunoglobulins 101 5.2Avianimmunoglobulins 102

5.2.1AvianIgM102

5.2.2AvianIgY(IgG)103

5.2.3AvianIgA104

5.2.4AvianhomologuesofIgD andIgE105

5.2.5Lchains105

5.2.6Genomicorganizationofthe IgHandIgLlocus105

5.3Ighalf-life 107

5.4Naturalantibodies 107

5.5Maternalantibodies 108

5.6Fcreceptors 109

5.6.1ChickenpolymericIgreceptor109

5.6.2ChickenFcRnhomologue110

5.6.3ChickenFcreceptorcluster110

5.6.4ggFcR110

5.6.5CHIR-AB1110

5.7Avianantibodyresponses 110

5.8Thechickeneggasasourceof antibodies 112

5.8.1Avianantibodiesastoolsfor research112

References 113

6. AvianTcells:AntigenRecognition andLineages 121

AdrianL.SmithandThomasW.Gobel

6.1Introduction 121

6.2Tcellreceptorstructureandlineages 121

6.2.1SomaticDNArecombination121

6.2.2OrganizationoftheTcell receptorclusters123

6.3CD3signalingcomplex 125

6.3.1MammalianCD3125

6.3.2ChickenCD3γ/δ andCD3ε 126

6.3.3 ζζ homodimer126

6.3.4Tcellreceptorcomplex—structural models126

6.3.5Tcellreceptorsignaltransduction127

6.4CD4andCD8 127

6.5Costimulatorymolecules 128

6.6Tcelllineages 129

6.7MethodstostudyTcellfunction 130

6.8Perspectives 130 References 131

7. Theavianmajorhistocompatibility complex 135

JimKaufman

7.1Introduction 135

7.2Thebiologyofthemajor histocompatibilitycomplex 135

7.3Themajorhistocompatibilitycomplex: agenomicregionorabiologicalunit? 136

7.4Thechickenmajorhistocompatibility complexandthemajorhistocompatibility complexsyntenicregion 137

7.5Classicalandnonclassicalmajor histocompatibilitycomplexmolecules 139

7.6Chickenclassicalmajor histocompatibilitycomplexmolecules 140

7.7Genecoevolutioninthechicken majorhistocompatibilitycomplex 142

7.8Otherchickengenesimportantfor themajorhistocompatibility complex 144

7.9Polymorphismandtypingchicken majorhistocompatibilitycomplex genes 145

7.10Avianmajorhistocompatibility complexes 146

7.11Immunity,diseaseresistance,andthe majorhistocompatibilitycomplexin wildbirds 148

7.12Sexualselectionandthemajor histocompatibilitycomplexinwild birds 149

7.13Originandevolutionoftheimmune system 150 Acknowledgments 151 References 151

8. Introductiontotheavianinnate immunesystem;properties, effects,andintegrationwithother partsoftheimmunesystem 163

ThomasW.GobelandAdrianL.Smith

8.1 Macrophagesanddendriticcells 167

KateSutton,AdamBalic,BerndKaspersand LonnekeVervelde

8.1.1Introduction 167

8.1.1.1Antigenpresentation167

8.1.1.2Dendriticcells168

8.1.1.3Macrophages169

8.1.1.4Developmentofmyeloid cells171

8.1.1.5Sourcesofavianmacrophages anddendriticcells172

8.1.1.6Avianmyeloidcelllines175

8.1.1.7Cellsurfacemarkersfor avianmyeloidcells175

8.1.1.8Characterizationof macrophagesandDCin tissuesections178

8.1.1.9Functionalpropertiesof chickenmacrophages178

8.1.1.10Macrophagemigration178

8.1.1.11Phagocytosis179

8.1.1.12Respiratoryburstactivity180

8.1.1.13Nitricoxideproduction:a readoutsystemforavian macrophageactivation180

8.1.1.14Cytokineresponseofavian macrophages182

8.1.2Functionalpropertiesofchicken antigen-presentingcells 183

8.1.2.1Maturationfromantigen samplingtoantigen presenting183

8.1.2.2Migration184

8.1.2.3Othernonmyeloid antigen-presentingcells185

8.1.3Concludingremarks 185 References 186

8.2 Aviangranulocytes 197

MichaelH.Kogut

8.2.1Functionalactivitiesofheterophils 197

8.2.2Receptors 198

8.2.3Otherinnateimmunereceptors 199

8.2.4Geneticeffectsonheterophil genotypeandphenotype 200

8.2.5Heterophilisolation 201 References 201 Furtherreading 203

8.3 Thrombocytefunctionsinthe avianimmunesystem 205

JakeAstill,R.DarrenWoodandShayanSharif

8.3.1Introduction 205

8.3.2Avianthrombocytestructure 205

8.3.2.1Physicalcharacteristics205

8.3.2.2Surfaceproteinexpression206

8.3.3Avianthrombocytesandimmune responses 208

8.3.3.1Innateresponses208

8.3.3.2Adaptiveimmuneresponses209

8.3.4Infectionofthrombocytes 210

8.3.5Conclusion 210 References 210

8.4 Naturalkillercells 213

ThomasW.Gobel

8.4.1Potentialnaturalkillercellreceptor families 213

8.4.2Phenotypeofchickennaturalkiller cells 214

8.4.3Naturalkillercellfunction 214 References 215

8.5 Solublecomponentsand acute-phaseproteins 217

EdwinJ.A.VeldhuizenandTinaSørensenDalgaard

8.5.1Solublecomponents 217

8.5.1.1Hostdefensepeptides217

8.5.1.2Collagenouslectins219

8.5.1.3SurfactantproteinAandcLL219

8.5.1.4Mannose-bindinglectin220

8.5.1.5Collectin10,-11,and-12220

8.5.1.6Complement221

8.5.1.7Componentsoftheclassical pathway222

8.5.1.8Componentsofthelectin pathway222

8.5.1.9Componentsofthe alternativepathway222

8.5.1.10Downstreamcomponentsof complement223

8.5.2Theacute-phaseresponse 223

8.5.2.1C-reactiveprotein223

8.5.2.2SerumamyloidA224

8.5.2.3 α1-acidglycoprotein224

8.5.2.4(Ovo)transferrin224

8.5.2.5PIT54225

8.5.2.6Hemopexin225

8.5.2.7Ceruloplasmin225

8.5.2.8Fibrinogen225

8.5.2.9OtherpotentialchickenAPPs225 References 226

8.6 Patternrecognitionreceptors 231

AdrianL.SmithandStevenR.Fiddaman

8.6.1Introduction 231

8.6.2Tissuefluidandsecretedpattern recognitionreceptors 232

8.6.2.1C-reactiveprotein232

8.6.2.2Collectins232

8.6.2.3Mannose-bindinglectin232

8.6.2.4Ficolins233

8.6.2.5Surfactants:surfactant proteinAandsurfactant proteinD233

8.6.2.6Othercollectins233

8.6.2.7Chickenmannose(ormannan)bindinglectin-associatedserine proteaseproteins,linkingsoluble patternrecognitionreceptorto complementactivation234

8.6.3Cell-associatedpatternrecognition receptors 234

8.6.3.1AvianToll-likereceptors234

8.6.3.2TLR1/6/10-relatedmolecules235

8.6.3.3TLR2235

8.6.3.4TLR3235

8.6.3.5TLR4236

8.6.3.6TLR5236

8.6.3.7TLR7andTLR8236

8.6.3.8TheabsenceofTLR9237

8.6.3.9AvianToll-likereceptorwithout mammalianorthologues: chTLR15andchTLR21237

8.6.3.10Toll-likereceptorsignaling pathwaysinchickens238

8.6.3.11Geneticdiversityand evidenceofselectionin avianToll-likereceptors238

8.6.3.12Othertransmembrane patternrecognitionreceptor239

8.6.4Cytosolicpatternrecognition receptor 240

8.6.4.1Nucleotide-binding oligomerizationdomain-like receptors240

8.6.4.2Retinoicacid-inducible gene-likereceptors240

8.6.5Closingcomments:general considerationsinpatternrecognition 241 Acknowledgments 241 References

9. Aviancytokinesandtheir receptors

AndrewG.D.BeanandJohnW.Lowenthal

9.1Introduction 249

9.2Aviancytokineandchemokine families 250

9.3Theinterleukins 250

9.3.1Theinterleukin-1family250

9.3.2T-cellproliferativeinterleukins251

9.3.3T-helperinterleukins252

9.3.4Th1interleukins254

9.3.5Th2interleukins254

9.3.6Th1 Th2paradigm255

9.3.7OtherThsubsets255

9.4Otherinterleukins 257

9.4.1Theinterleukin-10family257

9.4.2Theinterleukin-6family258

9.4.3Otherinterleukins259

9.5Theinterferons 259

9.5.1TypeIinterferon260

9.5.2TypeIIinterferon260

9.5.3TypeIIIinterferon260

9.6Otherfactors 260

9.6.1Thetransforminggrowth factor-β family260

9.6.2Thetumornecrosisfactor superfamily261

9.6.3Colony-stimulatingfactors261

9.6.4Cytokinesandfactorsinother birds261

9.7Chemokines 263

9.7.1XCandCX3Cchemokines264

9.7.2CCChemokines264

9.7.3CXCchemokines265

9.8Cytokineandchemokinereceptors 265

9.8.1TypeIreceptors266

9.8.2TypeIIreceptors266

9.8.3Transforminggrowthfactor-β familyreceptors267

9.8.4Tumornecrosisfactor superfamilyreceptors267

9.8.5Chemokinereceptors267

9.8.6Interleukin-1familyreceptors267

9.9Theimportanceofregulationof cytokineresponses 267

9.10Therapeuticpotentialofchicken cytokines 268

9.10.1Alternativestoantibiotic growthpromoters268

9.10.2Potentialuseofcytokinesas vaccineadjuvants269

9.11Conclusion 270 References 270

10. Immunogeneticsandthemapping ofimmunologicalfunctions 277

SusanJ.Lamont,JackC.M.Dekkers, AnnaWolcandHuaijunZhou 10.1Introduction 277

10.2Geneticsandimmunologicaltraits inthechicken 277

10.3Keygenelociforimmunologicaltraits 279

10.4Detectingquantitativetraitloci 280

10.4.1Linkagedisequilibrium281

10.4.2Experimentaldesignstodetect quantitativetraitloci281

10.5Statisticalproceduresforquantitative traitlocidetection 283

10.6Strategiestousemoleculardatain geneticselection 285

10.6.1Marker-assistedselection285

10.6.2Whole-genomeprediction285

10.7Systemsbiology 286

10.8Transgenicanimals 288

10.9Futuredirectionsforsystems biologyinavianimmunology 289 Acknowledgments 290 References 290

11. Themucosalimmunesystem 299

BerndKaspersandKarelA.Schat References 300

11.1 Theavianentericimmune systeminhealthanddisease 303

AdrianL.Smith,ClairePowersandRichardBeal

11.1.1Generalconsiderations 303

11.1.2Gutstructureandimmune compartments 304

11.1.2.1Chickengut-associated lymphoidtissuestructures305

11.1.2.2Cellularcompositionofthe aviangut-associated lymphoidtissues306

11.1.2.3Theenterocyteaspartof anintegratedgutimmune system306

11.1.3Developmentoftheenteric immunesystem 307

11.1.3.1Developmentofimmune responsestomodelantigens309

11.1.3.2Immunitytoenteric pathogens309

11.1.3.3Developmentofimmunity toentericpathogens309

11.1.3.4Maternalantibodyand protectionoftheyoung chick310

11.1.4Viralinfectionsofthegut 310

11.1.5Bacterialinfectionsofthegut 311

11.1.5.1Salmonella311

11.1.5.2Campylobacter313

11.1.5.3Necroticenteritis314

11.1.6Parasiticinfectionsofthegut 314

11.1.6.1 Eimeria spp315

11.1.6.2Otherparasiticinfections316

11.1.7Concludingremarks 317 Acknowledgments 317 References 317

11.2 Theavianrespiratoryimmune system 327

SonjaHartle,LonnekeVerveldeand BerndKaspers

11.2.1Introduction 327

11.2.2Anatomyoftherespiratorytract 327

11.2.3Theparaocularlymphoidtissue 329

11.2.4Nasal-associatedlymphoidtissue 330

11.2.5Thecontributionofthetracheato respiratorytractimmuneresponses 331

11.2.6Thebronchus-associatedlymphoid tissue 331

11.2.7Theimmunesysteminthe parabronchi 333

11.2.8Thephagocyticsystemofthe respiratorytract 334

11.2.9Handlingofparticlesinthe respiratorytract 335

11.2.10ThesecretoryIgAsysteminthe respiratorytract 335

11.2.11Geneexpressionanalysisasatool toinvestigatehost pathogen interaction 336

References

337

11.3 Theavianreproductiveimmune system 343

PaulWigley,PaulBarrowandKarelA.Schat

11.3.1Introduction 343

11.3.2Thestructureandfunctionofthe avianreproductivetract 343

11.3.3Structureanddevelopmentofthe reproductivetract-associated immunesysteminthechicken 344

11.3.3.1Organizationof lymphocytesinthe reproductivetract344

11.3.3.2Distributionofmacrophages andothercells344

11.3.4Localandsystemicchangestothe immunesystemattheonsetof sexualmaturityinhens 344

11.3.5Theinnateimmunesystemandthe reproductivetract 346

11.3.6Thereproductivetractimmune systemininfection 346

11.3.6.1Bacterialinfectionsofthe reproductivetract346

11.3.6.2Theimmuneresponseto Salmonellainfectionofthe reproductivetract346

11.3.6.3Responsestovaccination inthereproductivetract348

11.3.6.4Thechickenasamodelunderstandingimmunityin ovariancancer349

11.3.6.5Whatdoweneedto know—directionsfor futureresearch?349

11.3.6.6Whatarethefunctions andphenotypesofthecells inthereproductivetract?349

11.3.6.7Howdoestheimmune tissueofthereproductive tractintegratewiththerest oftheimmunesystem?349 References 349

12. Impactofthegutmicrobiotaon theimmunesystem 353

MichaelH.Kogut

12.1Introductiontothemicrobiotaand avianimmunesystem 353

12.2Microbiota,metagenome,and microbiome 354

12.3GItractandimmunesystemofpoultry 354

12.3.1Intestinalbarriersystem354

12.4Influenceofthemicrobiotain immunity 355

12.4.1Germ-freechickens355

12.4.2Antibiotic-treatedchickens356

12.4.3Fecalmicrobialtransplants356

12.4.4Layer-typechickensversus broilerchickens356

12.5Gutmicrobiota immunesystem communication 356

12.5.1Componentsofthemicrobiota357

12.5.2Microbialmetabolites357

12.5.3Microbialepigenetic modifications357

12.6Gutmicrobiota:immunehomeostasis 358

12.7Gutmicrobiota:immunedysfunction: dysbiosisandinflammation 358

12.8Managingthemicrobiomefor immunemodulation 359 References 359

13. Innatedefensesoftheavianegg 365

SophieRe ´ hault-Godbert,MaxwellHincke, RodrigoGuabiraba,NicolasGuyotand JoelGautron

13.1Introduction 365

13.2Eggbasicstructuresandtheirrole ininnatedefense 365

13.2.1Physicochemicalbarriers366

13.2.2Antimicrobialmolecules371

13.3Modificationofeggstructuresduring embryonicdevelopment 373

13.4Embryonicimmunity 374

13.4.1Toll-likereceptors374

13.4.2Macrophages374

13.4.3Heterophils374

13.4.4Dendriticcells375

13.4.5Tlymphocytes375

13.4.6NaturalKillercells376

13.4.7Cytokinesandchemokines376

13.5Extraembryonicstructuresandinnate immunity 376

13.5.1Amnioticsac377

13.5.2Yolksac378

13.5.3Theallantoicsac379

13.6Concludingremarks 380 References 380

14. Avianimmunosuppressive diseasesandimmuneevasion 387

KarelA.SchatandMichaelA.Skinner 14.1Introduction 387 14.2Immunosuppression 387

14.2.1Introduction387 14.2.2Stress-induced immunosuppression388 14.2.3Mycotoxin-induced immunosuppression389 14.2.4Coccidia-induced immunosuppression390 14.2.5Virus-induced immunosuppression390

14.3Mechanismsofimmunosuppression 399

14.3.1Corticosteroidsand stress-induced immunosuppression399

14.3.2Apoptosis,necroptosis,and pyroptosis399

14.3.3Virus-inducedchangesinthe regulationofimmuneresponses400 14.4Immunoevasion 401 14.4.1Introduction401 14.4.2Immunoevasionbyviral proteases401 14.4.3Immunoevasionmechanismsof aviancoronaviruses402 14.4.4Immunoevasionmechanisms oftheavianherpesviruses402 14.4.5Immunoevasionmechanism oftheavianpoxviruses402 14.4.6Immunoevasionmechanism oftheavianorthomyxoviruses404 14.4.7Immunoevasionmechanism oftheavianparamyxoviruses405 14.4.8Immunoevasionmechanism oftheavianreoviruses405 14.4.9Immunoevasionmechanism oftheavianbirnaviruses406 14.5Conclusions 406 References 406

15. Factorsmodulatingtheavian immunesystem 419 TinaSørensenDalgaard,JohannaM.J.Rebel, CristianoBortoluzziandMichaelH.Kogut 15.1Endocrineregulationofimmunity 419

15.1.1Stresshormones:epinephrine, norepinephrine,dopamine, andglucosteroids419

15.1.2Sexhormones420

15.1.3Metabolichormones:thyroid hormone,growthhormone, andleptin422

15.1.4Environmentallyresponsive hormones:melatonin422

15.2Physiologicalstates 423

15.2.1Temperatureandhousingas immunemodulators423

15.3Dietaryeffectsonimmunity 424

15.3.1Contributionofthe microbiome425

15.3.2Immunomodulatorynutrients andfeedadditives425

15.3.3Immunometabolism427

15.4Assessmentofimmunocompetence 428

15.4.1Functionalactivityofthe immuneresponse428

References 429

16. Autoimmunediseasesofpoultry 437

GiselaF.Erf

16.1Generalcharacteristicsofautoimmune diseases 437

16.2AutoimmunevitiligoinSmyth-line chickens 440

16.2.1Introduction440

16.2.2TheSmythlinechickenmodel forautoimmunevitiligo440

16.2.3Characteristicsofthe Smyth-linechicken441

16.2.4Pigmentationandnormal melanocytefunction442

16.2.5Targetcelldefects442

16.2.6Immunologicalmechanisms443

16.2.7Environmentalfactors445

16.2.8Summary446

16.3Spontaneousautoimmune (Hashimoto’s)thyroiditisin obese-strainchickens 446

16.3.1Introduction446

16.3.2Developmentand characteristicsofOSchickens447

16.3.3Immunologicalmechanisms447

16.3.4Targetcell/organdefects448

16.3.5Summary449

16.4SclerodermainUCD200/206chickens 449

16.4.1Introduction449

16.4.2Developmentandcharacteristics oftheUCD200/206lines450

16.4.3Immunologicalmechanisms450 16.4.4Summary452 Acknowledgments

17. Tumorsoftheavianimmune system 457

VenugopalNair

17.1Introduction 457

17.2Tumorsoftheimmunesystem 457

17.2.1Marek’sdisease457

17.2.2Avianleukosis459 17.2.3Reticuloendotheliosis460 17.3Oncogenicmechanismsoftumor viruses 460

17.3.1Oncogenicmechanismsof retroviruses461 17.3.2Oncogenicmechanismsof DNAtumorviruses461

17.4Immuneresponsestooncogenic viruses 461

17.4.1Immuneresponsesto leukosis/sarcomaviruses462 17.4.2Immuneresponsesto reticuloendotheliosisvirus462

17.4.3ImmuneresponsestoMarek’s diseasevirus462 17.5Antitumorresponses 463 17.6Conclusion 464

18. Practicalaspectsofpoultry vaccination 469

J.J.(Sjaak)deWitandEnriqueMontiel 18.1Introduction 469 18.2Vaccinetypes 469

18.2.1Livevaccines469 18.2.2Inactivatedvaccines470 18.2.3Poultryvaccineadjuvants471 18.3Vaccineapplication 471 18.3.1Massapplication471 18.3.2Individualapplications472 18.4Factorsinfluencingvaccine responses 474 18.4.1Statusoftheimmunesystem atthetimeofvaccination474 18.4.2Maternallyderivedantibodies474 18.4.3Vaccinestorage,preparation, andadministration475 18.4.4Ageatvaccination476 18.4.5Durationofimmunity476 18.4.6Interferencebetweenvaccines476

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

principle that a head without a halo is infinitely more desirable than a halo without a head.

While the disorderly Meccan forces were being steadily pressed back by the close-joined Moslem ranks, a furious storm of wind arose. Until this time, Mohammed seems to have been rather sceptical concerning the issue of his prayers; but, now that the foe was beginning to waver, he doubted no longer. “That,” he exclaimed while the tempest raged, “is Gabriel with a thousand angels charging down upon the foe.” Then, stooping and grabbing up a handful of small stones, he rose and hurled them at the Koreish, accompanying his action with the shout, “Confusion seize their faces!” This double assault, timed at the psychological moment, could not fail to have effect. The broken and shaken Meccan ranks—thoroughly discomfited by a lack of discipline, by a merely lukewarm interest in fighting their quondam neighbors and friends, and, as their own satirists abundantly pointed out later, by actual cowardice—cracked apart and fled in complete dismay, to be harassed and killed or captured by the pursuing Moslems. Mohammed lost but fourteen men in the encounter, whereas more than a hundred Koreish were slain or taken prisoners.

Curious scenes followed. A Moslem named Moadh had succeeded in cutting off Abu Jahl’s leg. Just then Moadh, attacked by Abu’s son, had found himself with one of his own arms almost severed; and, realizing that this member was now a useless impediment, Moadh bent over, placed his foot on the injured arm, wrenched it off, and continued to fight. At this moment one Abdallah came running up to assist Moadh, and, overjoyed at his good fortune in stumbling over such a notorious enemy, cut off Abu Jahl’s head and carried it to Mohammed. The Prophet, who was just beginning to celebrate his victory, raised the exultant shout: “The head of the enemy of God! God! there is none other God!” “There is none other!” agreed Abdallah, dropping his gory prize before Mohammed’s feet; and

Abdallah almost fainted from bliss when the Prophet continued, “It is more acceptable to me than the choicest camel in all Arabia.” It happened, also, that Ali had overheard Mohammed praying for the death of Naufal ibn Khuweilid, who had been taken prisoner; so Ali ran up, coolly slaughtered him, and promptly hastened with the good news to the Prophet, who joyously commented that this was doubtless a direct answer to his supplication. The spoil was soon gathered, and a pit was dug into which the Koreishite bodies were tossed; and Mohammed, who stood by watching the proceedings, greeted each corpse by name, adding this question, “Have ye now found true that which your Lord did promise you? What my Lord promised me, that verily I have found to be true.” “O Prophet!” inquired an amazed observer, “dost thou speak unto the dead?” “Yea, verily,” was the reply, “for now they well know that the promise of their Lord hath fully come to pass.”

Next morning, when the prisoners were led before him, he turned a malignant gaze upon Al-Nadr, who had been captured by Mikdad. “There is death in that glance,” the frightened Al-Nadr whispered to a bystander, and he was right; his trembling plea for mercy was rewarded with the response, “Islam hath rent all bonds asunder,” from a prominent Moslem, and with the command, “Strike off his head!” from Mohammed, who also felt moved to add, “And, O Lord, do Thou of Thy bounty grant unto Mikdad a better prey than this!” Another prisoner, Okba—a man well versed in Grecian, Persian and Arabian lore, who is said to have aroused the Prophet’s ire by the observation that, if a fund of good stories entitled a man to call himself a prophet, he was fully as good a candidate as Mohammed himself—was likewise ordered to face his doom. Mohammed, however, first satisfied Okba’s curiosity as to why he had been singled out for destruction with the words, “Because of thine enmity to God and his Prophet.” “And my little girl,” continued Okba, “who will take care of her?” “Hell-fire!” was the swift reply, as Okba was chopped to the ground. The Prophet, surveying the remains,

rejoiced after this fashion: “I give thanks unto the Lord that hath slain thee, and comforted mine eyes thereby.” Yet it should be stated that the defenders of Islam asseverate that Mohammed’s remarks to the Koreishite corpses were intended to express pity rather than hatred, and that the ejaculation “Hell-fire!” was a reference to the fact that Okba’s children were nicknamed “children of fire”—in other words, he implied that Okba’s descendants would be cared for by his relatives.

Whatever the facts may be, it is certain that Mohammed treated the rest of the captives with a kindness rarely matched in the martial history of Arabia. While the implacable Omar made a violent plea for their summary death, and while the easy-going Abu Bekr urged clemency, Gabriel winged his way from Allah’s presence with the gratifying information that Mohammed might do as he wished; but he added the portentous remark that, if the Koreish were spared, a like number of Moslems would perish in battle within the year. Mohammed eventually pleased everyone, except Omar, by announcing that the prisoners would not be slain, but that they could be freed only by ransom, and that those Moslems who might fall as Gabriel had foretold would “inherit Paradise and the crown of martyrdom.” His decision was probably reached on account of several considerations: the ransom for some seventy prisoners might benefit Islam even more than their blood; there was the further chance that some of them might become disciples; and, finally, he may conceivably have been more mercifully minded than his traducers admit.

Joy and thanksgiving were unbounded when the news of the overwhelming victory reached Medina; even the toddling children chased around the streets crying out, “Abu Jahl, the sinner, is slain!” The prisoners were so kindly treated that some of them actually became converts, while the stubborn remainder were ransomed for reasonable sums—except those whose wealth Mohammed’s

abnormally retentive memory still kept in mind. Thus, when the case of the opulent Naufal, Mohammed’s own cousin, came up, the Prophet amazed him with a demand for the thousand spears that he possessed; Naufal was so completely upset by this evidence of what appeared to be supernatural assistance that he is said to have accepted Islam on the spot. Among the prisoners, also, was the Prophet’s rich uncle Al-Abbas, who declined to pay on the ground that he was already a Moslem and that he had been obliged to fight against his conscience. “God knows best about that,” replied his nephew; “externally you were against us, so ransom yourself.” When Al-Abbas demurred, saying that he was now penniless, he was met with the pitiless query, “Then where is the money which, when you left Mecca, you secretly deposited with your wife?” Al-Abbas paid his ransom. Meanwhile a spirited discussion arose as to the way in which the booty—which included about one hundred and fifty camels and horses, together with vast quantities of vestments and armor should be divided; the matter, indeed, was so important that it could be settled only by a heavenly decree, which stipulated that one-fifth should be placed at the disposal of “God and the Prophet” and the remainder equally dispersed among the army.

But these were mere mercenary considerations. The outstanding, overshadowing fact was that a small body of Moslems had utterly routed a force three times their own number. Mohammed might well claim that he had at last performed a veritable miracle, and his subordinates might well have become a little vainglorious too; but the Koran soon placed the credit for the “Day of Deliverance” where it properly belonged. “As for victory, it is from none other than from God; for God is glorious and wise.... And ye slew them not, but God slew them. Neither was it thou, O Prophet, that didst cast the gravel; but God did cast it.” And yet the human side of the encounter was not neglected. The glorious Three Hundred who had fought and conquered such superior odds thenceforth became the peerage of Medina. Until the end of his life, Mohammed was willing to forgive

almost any sort of offence committed by any one of them, for, as he wisely declared, he could not be sure that Allah Himself had not given them free leave to do as they chose.

At Mecca, however, very different scenes were witnessed. The bitter pangs of shame and despair that everyone felt upon learning of the stunning defeat soon gave way to a fiery thirst for vengeance. For a month this frenzy reigned; then human nature intervened and a universal lament for the dead ascended, for almost every home in Mecca had been bereaved. A harrowing yet beautiful story illustrates how the grim self-restraint of the Koreish was finally broken. One night an aged father, who had lost two sons, heard the sound of weeping and thus commanded his servant: “Go see! It may be that Koreish have begun to wail for their dead; perchance I too may wail, for grief consumeth me within.” Informed that it was only a woman who was mourning for her strayed camel, he poured forth an impassioned threnody. “Doth she weep for her camel, and for it banish sleep from her eyes? Nay, if we will weep, let us weep over Bedr weep for Okeil, and for Al-Harith the lion of lions!” Perhaps the Koreish now realized the irreparable and fatal error they had made in deciding to take Mohammed seriously. Had they persisted in their original intention—mocked at him as an idle dreamer and a crack-brained idiot—he might have lived and died harmlessly in Mecca. But persecution had proved to be his best friend: forced to defend himself and to become the head of a little protecting army, he had revealed an unsuspected military acumen that had reduced his hostile kinsmen to this desperate condition. One Spartan couple in Mecca, however, refused to join in the common woe. “Weep not for your slain, mourn not their loss, neither let the bard bewail their fate,” was the stern advice of Abu Sufyan. “If ye lament with elegies, it will ease your wrath and diminish your enmity toward Mohammed and his fellows. And, should that reach their ears, and they laugh at us, will not their scorn be worse than all? Haply the turn may come, and ye may yet obtain your revenge. As for me, I will touch no oil,

neither approach my wife, until I shall have gone forth again to fight with Mohammed.” And when Abu’s wife, Hind, was chided for refusing to wail for her father, brother and uncle, she fiercely responded: “Nay, I will not weep until ye again wage war with Mohammed and his fellows. If tears could wipe the grief from off my heart, I too would weep as ye; but it is not thus with Hind.” Not to be outdone by her husband, she too declared that she would neither use oil nor approach her marital couch until an avenging Meccan army was on the march.

III

Elated at his astounding success, the Prophet occupied the following year in consolidating his gains and extending his influence. Meanwhile he continued to pay an exorbitant amount of homage to Allah, the Giver of all good; but, in starting a universal espionage system in Medina and in assuming an ever more menacing attitude toward unbelievers and Jews, he appears to have acted solely on his own responsibility. Nor were the Koreish idle during this year. As time slowly mitigated their poignant suffering, their business instincts revived and new trade routes were mapped out; the profits that accrued therefrom were stored up against the eagerly awaited day when a fearful retribution should be inflicted upon their murderous kinsmen. Abu Sufyan, who was chafing under the irksome restrictions of his vow, actually succeeded in destroying some enemy property and in slaying two Moslems; but when he joyfully hastened back to Mecca, under the impression that he had earned the dissolution of his oath, he discovered much to his chagrin that Hind did not agree with him. The Moslems, irritated because the Koreish had gained even such a slight success, retaliated by capturing a caravan that yielded one hundred thousand pieces of silver; yet, when the news of this added indignity reached the Meccans, it only

steeled their already inflexible determination—the moment for a swift and terrible vengeance had come.

Plans for a crushing campaign against the Moslems were drawn up; and all the Koreishites strained every nerve to expedite the martial plans and keep them secret all of them, that is, except AlAbbas, who, for some inexplicable reason, still retained a sneaking affection for the hard-hearted nephew who had forced him to pay such a stiff ransom. So it happened that, while Mohammed was communing with Allah in the Mosque during January, 625, a sealed letter, conveying the dreadful news that three thousand Koreish, including seven hundred warriors in armor and two hundred cavalry, were ready to march upon Medina, was handed to him. Despite the strongest efforts of the Prophet to keep this information secret, it leaked out and caused tremendous excitement and confusion. On this occasion, Mohammed’s perpetually-recurring dreams portended a defeat—he imagined that his sword was broken. A public meeting was called to discuss the ominous situation; and, according to some authorities, the Prophet related his dream, which he interpreted thus: “The fracture in my sword portendeth an injury to myself,” adding that it would be wisest to remain within the fortified walls of Medina. The elder Moslems agreed with their leader, but the young Hotspurs arose in violent opposition: they asserted that they would not “sit quietly here, a laughing-stock to all Arabia,” but would “go forth and smite our foes, even as we did at Bedr.” The headstrong impetuosity of youth prevailed, and Mohammed at length acceded. After preaching a strong discourse, in which he assured them, “If ye be steadfast, the Lord will grant you victory,” he retired to his house, whence he shortly emerged dressed in helmet and mail, with a sword hanging from his girdle. This sight deeply distressed the Moslems, for it appeared that their commander was at last going to risk his life on the battlefield; they therefore begged that he would follow his first counsel and remain within Medina’s walls. But he sternly replied: “I invited you to this and ye would not. It becometh

not a prophet, when once he hath girded himself to the battle, to lay his armor down again until the Lord hath decided betwixt him and his enemies. Wait, therefore, on the Lord. Only be steadfast, and He will send you victory.”

The talismanic effect of these words was immediate, and the Moslem army at once took to the field. It is not clear whether Abdallah ibn Obei, at the head of three hundred unbelievers, actually joined this army and then deserted when it was on the march; for some think that he never joined it at all. Mohammed is represented as having forbidden the unbelievers to assist him, saying that he did not desire “the aid of Unbelievers to fight against the unbelieving”; though other accounts maintain that Abdallah and his followers sallied forth with the faithful, but deserted at first sight of the enemy. Again, it is possible that Abdallah never manifested any desire to fight at all—that the tales both of his reprimand and desertion were invented by the Moslems in order to emphasize the smallness of their force. It was small enough, at all events, for barely seven hundred Moslems went forth to face a foe more than four times their own number. The Koreish had meanwhile circled the city, until they drew up for battle near the hill of Uhud, three miles to the north; and there the army of Allah met them.

There can be little doubt that, had the plan devised by Mohammed been followed, a victory, or at least a draw, would have been his. Realizing that success against such overwhelming odds could be gained only by far superior tactics and stratagems, he issued three imperative commands. He instructed fifty sharpshooters to remain, at all costs, on a little hill nearby, and prevent any effort of the Koreishite cavalry to attack from the rear—“stir not from this spot; if ye see us pursuing and plundering the enemy, join not with us; if we be pursued and even worsted, do not venture to our aid”— he enjoined upon his prayer-trained troops the imperious necessity of keeping their serried lines intact; and he forbade them to advance

until he gave the order, for he rightly believed that, so long as his force cohered, it would be impregnable. But the Prophet was destined to learn that, once a body of men has tasted the sweets of pillage and rapine, it is very likely not only to forget its religious professions but to disobey its own commander. When these admirable arrangements had been made, he cautiously donned a second coat of armor and sedately awaited for the foe to make the first move.

It was not long in coming. All at once the whole Koreishite force began to advance, while a group of women, headed by the bloodthirsty Hind and beating timbrels and drums, preceded the men and accompanied their rude music with stirring songs that promised special favors for the brave and threatened unbearable calamities for the timid.

“Daughters of the brave are we, On carpets step we delicately; Boldly advance, and we embrace you! Turn your backs and we will shun you Shun you with disdain.”

Then the Meccan champions, ardently desiring to win favor in the eyes of their martial females, rushed forth and dared individual Moslems to engage them in the customary single combat an invitation that was right gladly accepted. And now the history of Bedr was temporarily repeated, for a succession of Koreishites fell before the superior efficiency of Allah’s favorites. At first dismayed, and then angered, by the swift fate of their leading standardbearers, the Meccan force hurled itself at the Moslem array; but its inflexible front withstood the desperate assault, while the unerring archers, stationed on the little hill, prevented the Koreishite cavalry from disrupting the Moslem left wing. The Meccans wavered, cracked apart, turned irresolutely, and fled in ignominious haste,

while the jubilant Medinese, headed by their two heroes, Ali and Hamza, bounded hotly after the pusillanimous fugitives.

But, just at this moment, the validity of Gabriel’s warning after Bedr became manifest. Certain of their success, the Moslem ranks broke up and began to despoil the enemy camp; and this gratifying spectacle, which was seen by the archers, was too compelling to be resisted. Uttering anticipatory shouts of glee, they deserted their post and came running to join in the general fun. And then the situation speedily changed. No longer held at bay by a withering discharge of arrows, the Meccan cavalry whirled suddenly around and came smashing through the Moslem rear. Among others the great Hamza fell, mortally wounded by a javelin from the hand of a hired assassin. Hind, whose father had been slain by Hamza at Bedr, had bribed her Ethiopian slave, Wahshi, with the promise of freedom should he lay Hamza low; and his body had hardly ceased to quiver before Hind pounced savagely upon it, ripped out his liver, which she tore to pieces with her teeth, and collected his nails and fragments of skin to make bracelets for her arms and legs. The Medinese, taken completely by surprise and terror-stricken at the death of their greatest warrior, incontinently abandoned their arms and stolen property and began to run even faster than the Koreish had done a few moments earlier.

When Mohammed observed this calamitous reversal, he tried to rally his fleeing forces by expostulation. “Whither away?” he shouted; “Come back! I am the Apostle of God! Return!” But the Moslems were much more interested just then in saving their skins than in any number of prophets or gods; so Mohammed, for the first time in his career, was forced to fight for his life. We learn that he discharged arrows until his bow broke, whereupon he madly hurled stones about, and may possibly have killed one Meccan; yet, even in his dire extremity, he did not forget to make vehement promises of an incomparable reward in Paradise to any Moslem who would keep

the foe off his own person. But his under lip was wounded, one of his front teeth was broken, and a furious stroke drove his helmetrings into his cheek. Then, either because he was really stunned or exceptionally clever, he fell to the ground apparently dead, while among the Koreish the glad cry “Mohammed is slain!” resounded far and wide. Complete confusion seized the Moslems when they heard this appalling shout, and in their consternation they shrieked aloud, “Where now is the promise of his Lord?” Yet this very circumstance probably saved them from an utter rout, for the Koreish, certain of the Prophet’s decease, believed that their main object was attained and accordingly failed to take advantage of the victory that lay so easily within their grasp.

For Mohammed, in fact, was still very much alive. When this unbelievably good news spread, his confederates could not refrain from shouting it aloud; but, aware that he was yet in great danger, the Prophet peremptorily checked them. He was borne to a cave near by, where an attempt was made to care for his wounds; the helmet-rings had penetrated so deeply into his face that one poor fellow broke two teeth in a praiseworthy attempt to pull them out. Mohammed’s courage had now come back to such an extent that he essayed to apostrophize his enemies thus: “How shall a people prosper that treat thus their Prophet who calleth them unto the Lord! Let the wrath of God burn against the men that have besprinkled the face of His Apostle with his own blood! Let not the year pass over them alive!” At the same time, however, he deemed it advisable to change armor with another Moslem, in case the Koreish might come to search for him; then, rejoining his followers outside the cave, he glared at the Meccans retreating in the distance.

Just at this moment Abu Sufyan, who, puffed with pride, had remained to taunt his discomfited foes, called out, “Mohammed! Abu Bekr! Omar!” and, hearing no response, shouted, “Then all are slain, and ye are rid of them!” This was too much for Omar to endure with

equanimity; and so, disobeying the Prophet, he bellowed: “Thou liest! They are all alive, thou enemy of God, and will requite thee yet.” Hearing this, Abu Sufyan twitted Omar with these words: “Then this day shall be a return for Bedr. Fortune alternates as the bucket. Hearken! ye will find mutilated ones upon the field; this was not my desire, but neither am I displeased thereat. Glory to Al-Ozza! Glory to Hubal! Al-Ozza is ours, not yours!” It was now Mohammed’s turn to be vexed, though he wisely entrusted his retort to Omar who, properly primed by his chief, exclaimed: “The Lord is ours; He is not yours!” Abu Sufyan, who thought that the argument was becoming rather childish, merely answered, “We shall meet after a year at Bedr.” “Be it so!” growled Omar; and then Abu, together with Hind his spouse, made haste to return home so that they might mutually dissolve their twelve-months’ oath.

Only twenty Koreish had been slain, whereas the stark bodies of seventy-four Moslems were stiffening on the battlefield. Thither Mohammed now betook himself, and, upon seeing Hamza’s defiled corpse, he tugged angrily at his beard and swore that he would treat thirty Koreishite bodies in a similar way; but later he repented of this remark, and indeed issued stern orders forbidding his troops ever to mutilate a fallen enemy. The crumpled Moslem army then set out for Medina, for it was feared that the Koreish might decide to attack the defenseless city; but a scout soon came hastening up, shouting aloud the cheering news that the Koreish were hurrying southward toward Mecca. “Gently,” Mohammed mildly chided him, “let us not appear before the people to rejoice at the departure of the enemy!” For the Prophet was already profoundly absorbed in meditating schemes that would enable him satisfactorily to explain his defeat. But just now the sense of loss excluded every other emotion from the minds of the refugees and allies—the explanations could wait. Mingled with the ubiquitous sorrow was a feeling of helpless insecurity: the Koreish might yet change their minds and retrace their steps; so a watch was stationed at the Prophet’s door, behind

which he went to sleep so soundly that he failed to obey Bilal’s indefatigable call to evening prayers. The Meccans, however, who at this time had another easy opportunity to alter the map of the world, had decided that they had evened matters up with their kinsmen— and besides, they were much more interested in starting their remunerative caravans on the march again than in making or unmaking history.

Faced for the first time by an apparently irretrievable disaster, Mohammed well realized that not merely were his assumptions of sacerdotal preëminence, Allah Himself, and indeed all Islam, in imminent danger, but that his very existence would be at stake unless he proved able to satisfy the querulous clamors of his people and explain just how it was that he had failed. Never did his greatness reveal itself more splendidly than in this emergency; his every action was planned with the utmost care. His public demonstration of grief for Hamza, and his decision to visit the field of Uhud once a year to bless its Moslem martyrs—where, on each occasion, he regularly repeated the safe formula, “Peace be on you for that which ye endured, and a blessed futurity above!”—may have been genuine enough; at all events, such actions would be calculated to impress his underlings with his sincerity. But mutinous murmurs were now rampant: if Allah’s arm had brought victory at Bedr, what was He doing on the day of Uhud? and in any case what was to be thought of the Prophet’s multitudinous promises? Yet these apparently unanswerable complaints were no match for Mohammed’s wily brain. The masterful orator kept silence until the time came when, as was customary on Friday, he made known the latest dispatches from Allah in the Mosque.

And there he held the complainers in the hollow of his hand. The time and the place itself, with its rude but impressive grandeur, its venerable associations, its atmosphere of religious awe, had been chosen with surpassing care; and, before a word had been uttered,

the audience was unconsciously in a passive, hypnotic state. Then the Prophet, loosing every ounce of his tremendous nervous energy, poured forth a harangue in which subtle explanations, reproof, denunciation, self-justification, and finally mild praise and encouragement were blended with superb artistry. If Allah had conferred victory at Bedr, through the instrumentality of “the havocmaking angels,” He had permitted a defeat at Uhud in order to separate the true believers from the hypocrites; then, too, Allah had been with them until they disobeyed the Prophet—“When you ran off precipitately, and did not wait for any one, and the Apostle was calling you from your rear.” The cowardice of those who had stayed at home, as well as lust for loot, had also played a large part in the defeat; but the Prophet himself was blameless, for he had accepted the decision of a majority of Moslems as to where and how the battle should be fought. Nor had the Koreish gained by winning: “We grant them respite only that they may add to their sins; and they shall have a disgraceful chastisement.” Furthermore, was it possible that the Moslems had forgotten that the dead were infinitely better off in Paradise?—where “No terror afflicteth them, neither are they grieved.” And even if Mohammed, being only mortal like other men and “other Apostles that have gone before him,” had been killed, Islam must still continue: “What! if he were to die or be killed, must ye needs turn back upon your heels?” And finally: “Be not cast down, neither be ye grieved. Ye shall yet be victorious if ye are true Believers.”

When it was over, every shamefaced person present was thoroughly convinced that the Prophet, alone among the Moslems, was wholly guiltless, that Allah was more adorable than ever, and that the defeat at Uhud was an excellent example of a remarkably successful strategic retreat.

DEFEAT OF ALL INFIDELS

Another year sped by, until the appointed time came for the Koreish and the Moslems to clash again at Bedr. A prolonged drought, however, had impaired the Meccan finances to such an extent that Abu Sufyan decided it would be advisable to postpone the engagement; so, summoning strategy to his aid, he caused a rumor to be diffused through Medina to the effect that the Koreish had equipped a vast army for the impending conflict. The Moslems, whose spirits had not yet recovered from the shock of Uhud, were so perturbed at this report that they were unwilling to venture forth; but Mohammed, whose espionage system had now penetrated even as far as the confines of Mecca and who, therefore, was probably aware of Abu Sufyan’s ruse, swore a great oath that he would march to Bedr even though he marched alone. Shamed by their leader’s heroism, the Medinese recovered their courage; and the Prophet, at the head of fifteen hundred men, set out for Bedr in the spring of 626. The Koreish also finally scraped up enough tepid enthusiasm to venture forth with an army of over two thousand men; but they soon turned back, so they later declared, because of the lack of provisions. Though the Moslems were by no means sorry to hear of this, they publicly boasted their contempt for the “water-gruel” force from Mecca; then, since it was the time of the annual fairs, they

remained eight days at Bedr profiting greatly from the sale of the abundant wares they had carried in their train.

If, as it now appeared to Mohammed, the Koreish were disposed to keep the peace, the extended lull in hostilities would furnish an admirable opportunity to flaunt the banners of Islam over an ever widening extent of Arabia; for the defeat of Uhud, no less than the success at Bedr, had profoundly convinced him that the ultimate victory of Islam depended upon the sword. The Koran of this period breathes defiance against the enemies of Islam on almost every page; its profuse maledictions, once confined to the evildoers of Mecca, now include all unbelievers everywhere. All other things, even the hitherto unescapable performance of daily prayers, take second place to the relentless promulgation of the faith by military means. “When ye march abroad in the earth, it shall be no crime unto you that ye shorten your prayers, if ye fear that the Unbelievers may attack you.” Such an inducement was remarkably well calculated to win over to the army those numerous believers who had discovered that five highly complicated daily contortions were a little irksome, and the Moslem force therefore grew by leaps and bounds. As a result, during the summer of 626 Mohammed was able to conduct a successful campaign as far north as the border of Syria —an event of incalculable import. For the first time the tentacles of Islam had stretched beyond the bounds of Arabia: the curtain had risen on the first scene of a world-wide drama that still awaits its last act.

It seems probable that these sweeping expeditions at length aroused the Arabians to the danger that threatened them all. At all events, in the early months of 627 it happened that a confederacy of Koreishite, Bedouin and Jewish tribes put an army numbering approximately ten thousand men in the field against Medina. The Prophet well knew that the memories of Uhud, still rankling in the minds of his compatriots, made it highly inexpedient to desert the

city and meet the oncoming foe in the open field. Yet Medina must be defended at all costs—everyone, even the most feeble-kneed, was agreed upon that and feverish counsels were held to devise a plan whereby the city might be made impregnable against assault. At this crucial juncture, a Persian ex-slave suggested that the city be entrenched in the same way as, in his travels, he had observed that the Mesopotamian cities were protected. Acting immediately upon his inspired advice, the Moslems filled in the gaps between their outer line of stone houses with a stone wall; and, at the southeastern quarter, which was entirely defenseless, a deep and wide ditch was dug. After six days of prodigious and incessant labor, the trench was completed. The Prophet threw himself heartily into the work, and, dirty and weary as he was, joined his stentorian voice in unison with the other toilers as they once again intoned the words:

“O Lord! there is no happiness but that of Futurity. O Lord! have mercy on the Citizens and the Refugees!”

The result was that, when Abu Sufyan came marching up at the head of his conglomerate force, all that he could do was to permit his troops to shoot some harmless showers of arrows, pitch his tents, sit down, and wait for the Moslems to come forth. Entrenchments as a military device were entirely unknown in Arabia; so the invaders logically concluded that Mohammed was not a good sport—as on other occasions, he had violated the Arabic code of chivalry by proving that he had brains. “Truly this ditch is the artifice of strangers,” they yelled, “a shift to which no Arab yet has ever stooped!” But the Moslems did not take the hint, and so next day the besiegers made a gallantly unsuccessful attempt to rush the barricade by sheer weight of numbers. Nevertheless, the assault accomplished one very irritating thing: for a whole day the devoutest of the Moslems had been prevented from saying their prayers.

Gratifying amends for this forced neglect of Allah, however, were made when night fell; at that time an individual service was held for each omitted supplication, and Mohammed contributed a special comminatory request: “They have kept us from our daily prayers; God fill their bellies and their graves with fire!” Indeed, while the siege lasted, the Prophet spent most of the hours in protracted prayer, though he managed to find time enough to guard himself against the threatening activities of the Jews and other disaffected Medinese. Nor did his devices stop here. He even tried to buy off the Bedouins by promising them a third of the fruit from Medina’s datetrees; but his leading allies, the Aus and the Khazraj, opposed his trickiness and admonished him to “give nothing unto them but the sword.” Mohammed then played his trump card: if war was but a game of deception, why should he not skillfully divide the enemy against themselves? He instructed a trusty go-between to spread dissension among the foe by persuading the Bedouins and Jews in turn that their interests were mutually opposed. The scheme worked without a hitch, for the attacking forces, already discouraged by the cold, the difficulty of obtaining food, and the protracted delay, were ready to leave on any excuse. As a result, when a chilling storm of wind and rain incommoded them on the fifteenth day, they folded their tents and silently stole away. “Break up the camp and march,” commanded Abu Sufyan. “As for myself I am gone”—and he suited his action to his words by clambering hastily upon his camel and trying to urge it away while its fore leg was still hitched.

Scarcely had the last camel disappeared when the Prophet, after thanking Allah for his timely assistance in sending the storm, was visited by Gabriel. “What!” chided the tireless angel, “hast thou laid aside thine armor, while as yet the angels have not laid theirs aside! Arise! go up against the Beni Koreiza.” This Jewish tribe, which inhabited a fortress several miles southeast of Medina, had been the last to succumb to the blandishments of Abu Sufyan, but had finally yielded and taken part in the assault on Medina; so Mohammed

made haste to obey the celestial behest, even though he had previously borrowed from the Beni Koreiza the picks and shovels with which the trench had been excavated. Heading three thousand soldiers, he immediately marched to the Jewish stronghold where, inasmuch as it was marvelously protected by nature rather than its inhabitants, he found it necessary to keep guard for several weeks. In the end the Jews agreed to surrender on condition that the Aus, their supposed allies, should decide their fate. To this Mohammed agreed, and the Aus, almost with one voice, demanded that the Beni Koreiza should be treated gently; yet they signified their willingness to abide by the decision of their chief, a huge, corpulent fellow named Sa’d.

Now it chanced that Sa’d, suffering from an arrow-wound inflicted during the late siege, was not in a pleasant frame of mind; and it has been surmised that Mohammed may have craftily reckoned on this very fact. “Proceed with thy judgment!” he commanded Sa’d. “Will ye, then,” inquired Sa’d of his tribesmen, “bind yourselves by the covenant of God that whatsoever I shall decide, ye will accept?” After they had murmured their assent, he spoke. “My judgment is that the men shall be put to death, the women and children sold into slavery, and the spoil divided amongst the army.” A torrent of objections was about to be poured forth, when the Prophet savagely commanded silence. “Truly the judgment of Sa’d is the judgment of God,” he declared, “pronounced on high from beyond the Seventh Heaven.” Trenches were dug that night, and next morning some seven or eight hundred men were marched out, forced to seat themselves in rows along the top of the trenches, were forthwith beheaded, and then tumbled into the long, gaping grave; the Prophet meanwhile looked on until, tiring of the monotonous spectacle, he departed to amuse himself with a Jewess whose husband had just perished. But poor Sa’d did not live long to enjoy his revenge; barely had he reached home when his wounds re-opened and he soon breathed his last. As he lay dying, the

Prophet held him in his arms and prayed thus: “O Lord! Verily Sa’d hath labored in thy service. He hath believed in thy Prophet, and hath fulfilled his covenant. Wherefore do thou, O Lord, receive his spirit with the best reception wherewith thou receivest a departing soul!” Mohammed also helped to carry the coffin which, the bearers noted, was remarkably light for so heavy a man; but the Prophet explained the matter to the satisfaction of all. “The angels are carrying the bier, therefore it is light in your hands. Verily the throne on high doth vibrate for Sa’d, and the portals of heaven are opened, and he is attended by seventy thousand angels that never trod the earth before.”

II

Busily occupied though he had been for several years with the gradual subjugation of the Koreish, Mohammed had yet found time to compel a motley group of less important enemies to bow meekly beneath the yoke of Islam. The extinction of the Beni Koreiza had been but one link in the long chain of his conquests. His Meccan kinsmen had naturally been the first to be imperiously brushed aside; but other temporary impediments had occasionally blocked his way.

Among them the few Christians who were scattered here and there throughout Arabia were of least moment. Split asunder as they were into various warring sects—the Monothelites, Jacobites, Melchites and Nestorians—they worried the Prophet but little; he seems to have regarded them with a tolerant and mildly amused eye. Having had scanty intercourse with them, he was probably quite ignorant of their disputatious creeds; therefore, while the Koran always speaks respectfully of the Saviour, Who is invariably designated “Jesus, Son of Mary,” it makes many deplorable errors when it discusses the tenets and theogony of Christianity. It expressly denies that Jesus is the Son of God and completely

repudiates the established doctrine of the Holy Trinity: “Wherefore believe in God, and in the Apostles; and say not, There are Three. Refrain: it will be better for you. Verily the Lord is one God. Glory be to Him! far be it from Him, that there should be to Him a Son.” And Mohammed seems to have made the even more egregious error of supposing that the Trinity which he condemned was composed of the Father, Jesus and Mary; for the Koran utterly fails to recognize the incontrovertible existence of the Holy Ghost. Thus, while it has been reasonably urged that the Prophet both comprehended and hated Roman Catholicism, it may just as plausibly be argued that the conception of the Holy Spirit as a separate and distinct entity was too subtle for his eminently practical mind to grasp.

With Judaism, however, the case was very different. Though the Koran might place Christ on par with Abraham, Moses, David and other Hebrew prophets, it was to the customs and rites of the Jews that Mohammed paid obeisance rather than to those that had clustered around Christianity. Scarcely had he taken up his residence in Medina when he deliberately humbled himself in an effort to placate and win over the Jews; for, knowing their numbers and their power, he strongly desired to enter into a lasting union with them. To that end, he bound himself and his adherents to the Jews in a contract whose obligations were relatively mutual: “The Jews will profess their religion, the Moslems theirs.... No one shall go forth to war excepting with the permission of Mohammed; but this shall not hinder any from seeking lawful revenge.... If attacked, each shall come to the assistance of the other.... War and Peace shall be made in common.” There is also every reason to suppose that the command promulgated by Allah, when the Prophet visited Him in the Seventh Heaven, to the effect that all loyal Moslems must henceforth direct their prayers five times daily toward Jerusalem, was given because Mohammed expected that the Jews, seeing the Moslems thus busily engaged, would be insidiously flattered and insensibly led to look favorably upon Islam. Nor did his efforts stop here. The

period of fasting which he had decreed for the Moslems coincided with that time during which the Hebrews also abstained from food; when Jewish funeral processions passed, the Prophet and his brethren honored them by standing until they had disappeared; and the rite of circumcision—commonly practised by all Arabs out of deference to Abraham, the supposed founder of their holy city, Mecca—was also submitted to by the Moslems to the further pleasure of the Jews, who, however, remained in mystified ignorance as to whether Mohammed himself had undergone that ceremony. It is furthermore likely that the Hebraic horror of Christianity made the Jews look favorably upon this newcomer who, while he might not correspond exactly with the prophet who had been so long and so unsuccessfully anticipated by them, at least appeared to approximate their ideal. What else could be thought of a man who formulated the amazing doctrine that a Jew might synchronously be a devout follower of Abraham and Allah, and might therefore attend both the services of the Mosque and the Synagogue with equal impunity? Indeed, there is much evidence to support the view that, had the Jews saluted Mohammed as the prophet who had at last arrived among them, Islam would have been rapidly absorbed by Hebraism.

But Allah had other plans. A year’s commingled residence in Medina taught the members of both sects many, many things. Inasmuch as the Jews literally owned the city, the needy Moslems were compelled to turn to them for positions, provisions and for money to borrow; and they soon learnt that their creditors were as merciless as they were devout. Abu Bekr, having approached a certain Pinchas with the quaint request, “Who will lend God a good loan?” was rebuffed with the quick retort, “If God wants a loan, He must be in distressed circumstances”; whereupon Abu, who had absolutely no flair for repartee, won some slight consolation by knocking Pinchas down. The Prophet himself—who, even after he began to extirpate the Hebrews, invariably turned to them when his

financial credit was bad—had experiences similar to Abu’s; and it is a matter of interest that he now for the first time began to notice that the odors arising from the Jewish habitations were decidedly offensive to his ever-fastidious nose. Another thing that fanned the rising fires of disaffection was the fact that, for more than a year after the Hegira, no Moslem woman gave birth to a child; and the Jews openly bragged that their secret sorceries and enchantments had produced this barrenness. The Moslems, completely upset over this unheard-of catastrophe, exhausted themselves in the attempt to discover an adequate remedy; and the Prophet was so much concerned that he probably composed two Suras especially designed to frustrate the Jewish spells. Yet, in spite of the Hebraic incantations, a Moslem child was born fourteen months after the flight to Medina, and never again was there any doubt as to the fertility of the Moslem women.

The Jews, too, had experienced a mental revolution. A prophet who, as they had discovered, could not speak Hebrew, and who, when put to the test, betrayed an abysmal ignorance concerning the wealth of intricate information stored in the Pentateuch, did not wholly correspond to their idealized conception of their Messiah. They might blandly admit that his dissertations were satisfactory, but when he pressed his prophetic claims upon them they courteously retorted that their particular prophet must be able to trace his lineage straight back to David. They objected, also, when they noted how great a proportion of his time Mohammed spent in his harem, whereas the Jews, of all people, might well have regarded that harmless idiosyncrasy as a clinching proof that his mission was divine. Again, when the Prophet vainly tried to save the life of one of his earliest converts by cauterizing his sore throat, the Jews poked fun at him. “If this man were a prophet, could he not have warded off sickness from his friend?” they mockingly asked. And all that Mohammed could think of to say was this: “I have no power from my Lord over even mine own life, or over that of any of my

followers. The Lord destroy the Jews that speak thus!” From this time on, instead of sitting up night after night, as he had once done, telling affecting tales about the Children of Israel, he began to belabor their descendants in the pages of the Koran. Where it had once iterated and reiterated the manifold virtues of the ancient Hebrews, it now discussed their manifold vices—their idolatries, backslidings, and betrayals—at even greater length; and an almost Christian fervor breathes from those pages where the Prophet asseverates that the wilful stupidity of the Jews caused them to reject him even as they had previously spurned Jesus.

Some faint-hearted Hebrews, who perhaps suspected what was coming, were diplomatic enough to swallow the new faith entire, thereby winning from Mohammed the appellation of “Witnesses.” Abdallah, son of Salam, was a shining example. Having slyly induced his brethren to give him a character testimonial before they knew that he was about to become a renegade, he presented it to the Prophet who was so pleased that he assured Abdallah he was already in Paradise—even Sa’d, chief of the Aus, had not received a comparable congratulation. But Abdallahs among the Jews were rare. Most of them continued to snicker at the hilarious ignorance and bombast revealed in Mohammed’s homiletical discourses, to disregard Allah’s grim warning that they should repent and turn to Islam “before We deface your countenances, turning the face backwards,” and to wax fat on the miseries of the Moslems. On the other hand, the Moslems themselves no longer made any effort to conceal their desire to hold their noses when they were compelled to approach the Jews on business matters; and the Prophet himself shortly decided to put a summary end to all attempts at reconciliation and brotherhood.

Perhaps the success that attended his decision to fight during the sacred months suggested the idea that he was now strong enough to break definitely with the Jews. One day, not long afterward, while

he stood at prayer in the Mosque with his face turned as usual toward the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, he received a lightning revelation to turn “toward the holy Temple of Mecca. Wheresoever ye be, when ye pray, turn toward the same.” The divine injunction came just after he had prostrated himself twice toward Jerusalem; quick as a flash he reversed himself an action instinctively followed by all the automatons in the audience—and faced toward the south until the service was ended. This symbolic event signalized his determination henceforth to separate himself wholly from the Jews, as well as to gratify the atavistic longings of his zealots who had never quite succeeded in relinquishing their love for the Black Stone and the Kaba; then too, Mohammed had grown very tired of listening to a favorite Hebraic taunt: “This Prophet of yours knew not where to find his Kibla [house of worship] till we pointed it out to him.” The Jews, who fully understood the sinister significance of Mohammed’s sudden right-about-face, were much perturbed; and they had reason to be, for he lost no time in sundering every tie that connected the worship of Allah with Hebraic ceremonies. He commanded the Moslems to keep their fast before or after the Jewish Day of Atonement; he once more followed the Arabic custom of combing his hair instead of letting it drift loose, as the Jews did; he altered the Moslem funeral rites so that they again corresponded to the immemorial Pagan ritual; and he changed the regulations pertaining to the lunar indisposition of females to a system that Moses assuredly would not have approved. For it must be demonstrated that Allah was more powerful than Jehovah; that Mohammed, as the last of a long line of prophets, had an ultimate claim upon the sacerdotal office; and that the superior wisdom which the Jews boasted concerning celestial matters over which he had hitherto asserted his sole jurisdiction would be of no use whatever to them—after they were dead.

The triumph of Bedr encouraged Mohammed to expedite his plans of revenge against his internal foes; directly or indirectly, he stimulated his accomplices to assassinate them. Peculiarly sensitive as he was to the slurring satires and puns which the Jews had aimed against some of his most cherished speeches, and being wholly incapable of retorting in kind, he was only too pleased when the Moslems showed a demoniacal readiness to avenge his wounded honor with sharper-pointed weapons than epigrams. Asma, a poetess strongly on the side of the Jews, composed some verses that castigated the disaffected Medinese for bowing before an interloper whom she represented as hoping that the city would “be done brown” so that he might enjoy a toothsome banquet; shortly afterward, one of the Prophet’s men stole into her room at midnight and, after taking the trouble to remove her nursing baby, thrust his sword through her breast. Next morning Mohammed paused in his prayers at the Mosque long enough to inquire of the murderer, “Hast thou slain the daughter of Merwan?” “Yes,” was the reply, “but tell me now, is there cause of apprehension?” “None,” the Prophet assured him, “a couple of goats will hardly knock their heads together for it.” Then, turning toward the congregation, he shouted: “If ye desire to see a man that hath assisted the Lord and His Prophet, look ye here!” A second satirist, old Abu Afak, a Jewish convert, foolishly attempted to carry on the work begun by Asma. “Who will rid me of this pestilent fellow?” inquired Mohammed; and within a few hours Abu Afak, while carelessly sleeping in a courtyard, was also transfixed with a sword. Both of these deeds were committed within a week after Bedr.

About six months later one Ka’b, another Jewish versifier who, like most satirists of his time, signalized his craft by anointing his hair on one side, allowing his clothes to become disordered, and wearing but one shoe, decided to amuse himself by making public a series of poems that were intimately concerned with the amatory

charms of some of the most generous Moslem women. Of a beauty named Um al-Fadl he wrote:

“Of saffron color is she; so full of charms that if thou wert to clasp her, there would be pressed forth Wine, Henna, and Katam; So slim that her figure, from ankle to shoulder, bends as she desires to stand upright, and cannot.

When we met she caused me to forget my own wife Um Halim, although the cord that bindeth me to her is not to be broken.

I never saw the sun appear by night, except on one dark evening when she came forth unto me in all her splendor.”

Ka’b was also believed to be engaged in double dealings with the Koreish, and so the Prophet offered this public prayer: “O Lord, deliver me from the son of Al-Ashraf, in whatever way it seemeth good unto Thee, because of his open sedition and his verses.” And lest there might be doubt as to how he wished his supplication to be fulfilled, he asked his servants this pointed question: “Who will ease me of the son of Al-Ashraf? for he troubleth me.” Maslama’s son Mohammed, a well-known Moslem libertine, responded, “Here am I —I will slay him.” “Go!” exclaimed the happy Prophet, “the blessing of God be with you, and assistance from on High!” Aided by four conspirators, this Mohammed succeeded in luring Ka’b away from his bride on a moonlight night. Suddenly seizing his long hair, they pulled him to the ground with the shout: “Slay him! Slay the enemy of God!” and immediately stabbed him to death. “Welcome!” said Mohammed on their return, “for your countenances beam of victory.” “And thine also, O Prophet!” they replied, as the victim’s head was tossed down before his feet.

On the following day Mohammed, having decided that the only good Jews were dead or exiled ones, gave the Moslems free leave to kill them upon sight. Muheisa, a converted Khazrajite, at once availed himself of this long-desired privilege by slaughtering the first

Hebrew he chanced to meet; and when his brother Huweisa chided him for his excessive zealotry, he growled: “By the Lord! if he that commanded me to kill him had commanded to kill thee also, I would have done it.” “What!” screamed Huweisa, “wouldst thou have slain thine own brother at Mohammed’s bidding?” “Even so,” was the cool answer. “Strange indeed!” said the aghast Huweisa, “hath the new religion reached to this? Verily, it is a wonderful faith!” And he immediately proclaimed his own conversion to Islam.

Many of the Jews would doubtless have liked to follow his example, but their day of grace was past; no longer could they qualify as “Witnesses” for Mohammed. For indeed his heart was set upon their extermination, or—what was even better—the robbery of their goods; and to that end, like a good general, he proceeded first against those who dwelt in Medina. About a month after Bedr, he went to the wealthy tribe of Beni Kainuka, who practised the goldsmiths’ trade in Medina, and peremptorily announced his errand thus: “By the Lord! ye know full well that I am the Apostle of God. Believe, therefore, before that happen to you which has befallen Koreish!” But they hurled defiance at him, so he decided to wait until he could find a convenient excuse to attack them. He soon found it. As a Moslem girl was trading in a goldsmith’s shop one day, a frivolous-minded Jew sought entertainment by creeping up behind her and pinning the bottom of her skirt to her shoulder; howls of merriment followed and the poor maiden almost died of shame. A Moslem who soon avenged the insult by slaying the sprightly Jew was killed in turn by other Jews; and thus the Prophet was conscientiously able to proceed against the Beni Kainuka—for had they not broken the solemn treaty hitherto contracted between the Moslems and the Hebrews? A fortnight’s siege ended in their abject surrender; their hands were then tied and they were led out to be executed. At this moment Abdallah ibn Obei, who still retained some remnants of power in Medina, approached the Prophet with a plea for mercy. But the only reply was an averted face, so Abdallah seized