Sex Differences in Cardiac Disease

Pathophysiology, Presentation, Diagnosis and Management

Edited by

Niti R. Aggarwal, MD, FACC, FASNC

Senior Associate Consultant

Mayo Clinic

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science Rochester, MN, United States

Malissa J. Wood, MD, FACC

Co-director Corrigan Women’s Heart Health Program

Massachusetts General Hospital Boston, MA

Medical Director

MGH Danvers Ambulatory Cardiology Center Danvers, MA

Associate Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School Boston, MA, United States

Elsevier

125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS, United Kingdom

525 B Street, Suite 1650, San Diego, CA 92101, United States

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, United Kingdom

© 2021 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-12-819369-3

For information on all Elsevier publications visit our website at https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: Stacy Masucci

Acquisitions Editor: Katie Chan

Editorial Project Manager: Tracy I. Tufaga

Production Project Manager: Kiruthika Govindaraju

Cover Designer: Christian J. Bilbow

Typeset by SPi Global, India

Niti R. Aggarwal, MD

To my parents, Monica and Ranjit, for their unconditional love, steadfast belief in me, and for teaching me the value of high expectations

Malissa J. Wood, MD

To my late parents, Betty and Bob Wood, for their love and constant support, and for showing me each day how grit, determination, and hard work would be instrumental in helping me reach my goals

Contributors

Beth L. Abramson, MD, MSc, FRCPC

University of Toronto; Division of Cardiology, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Niti R. Aggarwal, MD

Department of Cardiovascular Disease, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, MN, United States

Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Ventricular Arrhythmias

CardioOncology

Cardiovascular Medications

Women’s Heart Programs

Jack Aguilar, MD

Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

Christina K. Anderson, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Rush Medical College, Chicago, IL, United States

Atrial Fibrillation

Zoltan Arany, MD, PhD

Division of Cardiology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy

C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD

Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

Ami B. Bhatt

Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Congenital Heart Disease

Laurie Bossory, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, United States

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Konstantinos Dean Boudoulas, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, United States

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Renee P. Bullock-Palmer, MD

Department of Cardiology, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, NJ, United States

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Sarah Chuzi, MD

Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Daniela Crousillat, MD

Cardiac Ultrasound Laboratory, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Valvular Heart Disease

Anne B. Curtis, MD

Department of Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, United States

Atrial Fibrillation

Esther Davis, MBBS, DPhil

Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Disease

Anita Deswal, MD, MPH

Cardiology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States

Sex Differences in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Mariana Garcia, MD

Emory University, School of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Atlanta, GA, United States Epidemiology and Prevalence

Eugenia Gianos, MD

Northwell Health, Department of Cardiology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New York, NY, United States

Sex Hormones and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Health

Ridhima Goel, MD

Interventional Cardiovascular Research and Clinical Trials, The Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, United States Interventions in Ischemic Heart Disease

Rajiv Gulati, MD, PhD

Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, MN, United States

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection

Sonia A. Henry, MD

Northwell Health, Department of Cardiology, Northshore University Hospital, Zucker School of Medicine at Hoftsra Northwell, Manhasset, NY, United States

Disparity in Care Across the CVD Spectrum

Jeff C. Huffman, MD

Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States Psychosocial Issues in Cardiovascular Disease

Sasha De Jesus, MD

Northwell Health, Department of Cardiology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New York, NY, United States

Sex Hormones and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Health

Deborah N. Kalkman, MD, PhD

Interventional Cardiovascular Research and Clinical Trials, The Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, United States; Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Heart Center, Department of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Interventions in Ischemic Heart Disease

Cynthia Kos, DO

Department of Cardiology, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, NJ, United States

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Yamini Krishnamurthy, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY, United States

Congenital Heart Disease

Gautam Kumar, MD

Division of Cardiology, Emory University School of Medicine; Atlanta VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA, United States

Takotsubo Syndrome

Sonali Kumar, MD

Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute and Emory Women’s Heart Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States Takotsubo Syndrome

Benjamin Laliberte, PharmD, BCCP

Department of Pharmacy, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Unique Features of Cardiovascular Pharmacology in Pregnancy and Lactation

Emily Lau, MD

Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease

Ana Micaela León, BA

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

Takotsubo Syndrome

Jennifer Lewey, MD, MPH

Division of Cardiology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy

Christina M. Luberto, PhD

Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Psychosocial Issues in Cardiovascular Disease

Rekha Mankad, MD

Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States CardioRheumatology

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States Epidemiology and Prevalence

Stephanie Trentacoste McNally, MD

Northwell Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New York, NY, United States

Sex Hormones and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Health

Roxana Mehran, MD

Interventional Cardiovascular Research and Clinical Trials, The Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, United States Interventions in Ischemic Heart Disease

Laxmi S. Mehta, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, United States Acute Coronary Syndrome

Puja K. Mehta, MD

Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute and Emory Women’s Heart Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States Takotsubo Syndrome

Theofanie Mela, MD

Cardiac Arrhythmia Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States Role of ICD and CRT

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS

Division of Cardiology, The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

Jennifer H. Mieres, MD

Zucker School of Medicine at Hoftsra Northwell, Northwell Health, Lake Success, NY, United States Disparity in Care Across the CVD Spectrum

Iva Minga, MD

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Northshore University Health System, Evanston, IL, United States CardioOncology

Anum Minhas, MD

Division of Cardiology, The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

Selma F. Mohammed, MD, PhD

Creighton University; Catholic Health Initiative Heart and Vascular Institute, Omaha, NE, United States Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Sharon L. Mulvagh, MD, FRCP (C) Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada Women’s Heart Programs

Ajith P. Nair, MD

Section of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

Anna O’Kelly, MD

Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease

Tochi M. Okwuosa, DO

Rush University Medical Center, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Chicago, IL, United States

CardioOncology

Elyse R. Park, PhD, MPH

Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Psychosocial Issues in Cardiovascular Disease

Hena Patel, MD

University of Chicago, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Chicago, IL, United States

CardioOncology

Odayme Quesada, MD

Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

Stacey E. Rosen, MD

Northwell Health, Department of Cardiology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New York, NY, United States

Sex Hormones and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Health

Andrea M. Russo, MD

Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, United States

Ventricular Arrhythmias

Amy Sarma, MD

Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Disease

Dawn C. Scantlebury, MBBS

Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, St. Michael, Barbados

Sex Hormones and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Health

Nandita S. Scott, MD

Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Pregnancy and Cardiovascular Disease

Ashish Sharma, MD

Internal Medicine Residency Program, Mercer University School of Medicine Coliseum Medical Center, Macon, GA, United States Takotsubo Syndrome

Garima Sharma, MD

Division of Cardiology, The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

Chrisandra Shufelt, MD, MS

Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

Kajenny Srivaratharajah, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, ONT, Canada

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Juan Tamargo, MD, PhD

Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Instituto de Investigación

Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain Cardiovascular Medications

María Tamargo, MD

Department of Cardiology, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria

Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain

Cardiovascular Medications

Pamela Telisky, DO

Department of Cardiology, Deborah Heart and Lung Center, Browns Mills, NJ, United States Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Marysia S. Tweet, MD

Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, MN, United States

Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection

Birgit Vogel, MD

Interventional Cardiovascular Research and Clinical Trials, The Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY, United States

Interventions in Ischemic Heart Disease

Annabelle Santos Volgman, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Rush Medical College, Chicago, IL, United States

Atrial Fibrillation

Esther Vorovich, MD

Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Janet Wei, MD

Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

Nanette K. Wenger, MD

Emory University School of Medicine; Emory Heart and Vascular Center; Emory Women’s Heart Center, Atlanta, GA, United States

Introduction: Past, Present, and Future of Heart Disease in Men and Women

Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MS

Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Gloria Y. Yeh, MD, MPH

Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Beth Israel Deaconess, Medical Center/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Psychosocial Issues in Cardiovascular Disease

Debbie C. Yen, PharmD, BCCP

Internal Medicine Clinic, 10th Medical Group, United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, CO, United States

Unique Features of Cardiovascular Pharmacology in Pregnancy and Lactation

Evin Yucel, MD

Cardiac Ultrasound Laboratory, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Valvular Heart Disease

Preface

Sex-based differences in cardiovascular disease (CVD) have traditionally been poorly appreciated and understood, with women being underrepresented in research, clinical trials, and publications. Previously, research studies were largely conducted on men, and results were extrapolated to women. Over the past decade there has been an improved appreciation of sex differences and a dramatic increase in data specifically addressing cardiovascular conditions in women and men. Commensurate with this abundant body of literature and research, CVD deaths in both men and women have declined. Despite this progress, disparities in CVD care persist with women being less likely to receive evidence-based medicine and interventions, and often experiencing worse morbidity and mortality. There is a growing recognition that there are biological differences between men and women that contribute to sex-specific differences in risk factors, pathophysiology, presentation, diagnostic algorithms, and response to therapy. There is a clinical need for a comprehensive book consolidating the vast literature addressing sex-specific differences in CVD, and highlighting the areas of unmet need. This book fills that void, and provides a systematic review of current literature addressing these differences in a cohesive and accessible manner. The chapters are written by well-recognized experts in their respective fields. Each chapter includes figures and tables created to provide concise summaries which cover the specific concepts presented in each chapter. Where appropriate, a clinical case is presented at the beginning of each chapter to better highlight the key clinical features of the topic. The authors also provide clear, concise summary points at the conclusion of each chapter. Most chapters conclude with an “Editor’s summary,” an infographic designed by the Editors, highlighting key features of the chapter.

Dr. Nanette K. Wenger graciously authored the Introduction which beautifully sets the stage for the sections and chapters that follow. The book includes 13 sections and a total of 29 chapters.

The second and third sections of the book focus on epidemiology of heart disease (including discussion of risk factors unique to women) and sex differences in ischemic heart disease. CVD continues to serve as the leading cause of death in men and women, and there is an ongoing need to increase awareness of CVD in women (Chapter 2). There exist several barriers to women seeking CVD care, including

the desire to put others before self, caretaker responsibilities, inadequate self-confidence, social stigma, and inadequate financial resources. While there has been a decline in CVD-related mortality among older women, there has been a relative stagnation in mortality among younger women, especially in maternal mortality (Chapter 21). It is now recognized that the traditional risk factors confer a differential risk in women, compared to men (Chapters 2 and 3). For instance, diabetes confers a 45% higher risk of ischemic heart disease in women compared to men. Furthermore, there is increasing recognition of the presence and impact of novel risk factors unique or more common in women, including gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and early menopause and menarche, and incorporated in risk scores (Chapter 3). The presence of chronic autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis also significantly increases the risk of developing premature coronary and systemic atherosclerosis (Chapter 23). Despite the high burden of disease and presence of these risk factors, women often do not seek care even during an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (Chapter 4). Compared to men, women often experience delays in presentation, longer door to needle times, less pharmacotherapy, and fewer revascularizations at the time of hospital discharge after an ACS. Physiologic and anatomic differences in women such as smaller coronary artery size, more coronary tortuosity, less coronary calcification, and presence of higher fractional flow reserve volumes for any given stenosis might contribute to the higher prevalence of adverse events in women undergoing revascularization compared to men (Chapter 6). While obstructive, atherosclerotic CAD remains the most common etiology of acute coronary syndromes overall, less common etiologies of ACS including spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), microvascular coronary disease, vasospasm, and coronary embolism can be seen in both sexes, but are more common in women (Chapters 5, 8, and 9). Recognition of these less common forms of coronary artery disease and evaluation for the full spectrum of ischemic heart disease is imperative due to long-term prognostic significance (Chapter 7).

The fourth section of the book is devoted to sex differences in heart failure. Sex differences persist in the form of heart failure, with women having a lower lifetime risk

of experiencing heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) compared to men (Chapter 10). In contrast, at any given age, prevalence of HFpEF is higher in women compared with men (Chapter 11). HFrEF is associated with higher mortality and higher rates of ventricular assist device usage and heart transplantation in men. Despite these data, women living with heart failure experience worse quality of life compared to men (Chapter 10). Takotsubo syndrome is one form of left ventricular systolic dysfunction with 90% of cases occurring in women (Chapter 13). Although less frequent, men with this cardiomyopathy have a higher rate of out-of-hospital arrest and sudden cardiac death. While the overall risk of death is low, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a significant contributor to the increasing maternal mortality rate in the United States. PPCM disproportionately affects black women, and timely diagnosis and aggressive treatment are essential to reduce the morbidity and mortality of affected women (Chapter 14). Pulmonary arterial hypertension, while more common in women, is associated with a higher overall mortality rate in men (Chapter 12).

Successful strategies utilized in the management of ventricular and atrial arrhythmias include both pharmacologic and procedural interventions. A nuanced approach to management is required given the significant sex- and gender-related differences in responses to these therapies. Atrial fibrillation, the most common sustained arrhythmia, is associated with greater risk of disabling stroke in women. Despite this, women are less likely to be prescribed systemic anticoagulation (Chapter 16). Women have a lower lifetime risk of experiencing sudden cardiac arrest at any age (Chapter 17). Men with sudden cardiac arrest are more likely to present with ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. In contrast, women are more likely to present with pulseless electric activity or asystole. Women are underrepresented in trials of antiarrhythmic drugs and implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy (Chapters 17 and 18).

In addition to being more likely to experience atypical symptoms in the presence of ischemic heart disease and arrhythmias, women with peripheral vascular disease are also less likely to experience symptoms of claudication than are men. Disparities in the care of women with vascular disease include less frequent revascularization and less aggressive medical therapy (Chapter 19).

Given advances in treatment of congenital heart disease, today more adults than children are living with congenital heart disease. These patients require comprehensive teambased care given the cardiac and extra-cardiac complications associated with congenital heart disease. Pregnancy poses a particular risk to women with congenital heart disease (Chapter 20) and it provides a window into a woman’s overall cardiovascular health. Complications of pregnancy, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, portend increased risk of future cardiovascular events and should

be taken into consideration in overall cardiovascular risk assessment. Women with preexisting cardiac disease should undergo a thorough preconception risk assessment and should be managed by a multidisciplinary cardio-obstetric team throughout pregnancy. Clinicians caring for women of reproductive age with cardiovascular disease must familiarize themselves with the safety profiles of medications frequently used in the management of heart disease (Chapters 21 and 22).

Over the past decade, in addition to cardio-obstetrics described above, there has been an emergence and growth of several additional novel cardiovascular disciplines: cardiorheumatology and cardiooncology (Chapters 23 and 24). There has been a rapid increase in the numbers and types of therapies available for treatment of inflammatory conditions and cancer. While many of these therapies are associated with dramatically improved outcomes, many have adverse cardiovascular side effects and impact on overall cardiovascular health. Furthermore, there is also a growing recognition of the common risk factors between coronary artery disease and breast cancer.

In Chapter 25, the authors provide a detailed review of the impact of reproductive hormones on the cardiovascular system. This comprehensive chapter covers reproductive health (contraception and treatment of infertility), menopausal replacement therapy, transgender hormone use, and therapeutic use of hormones in treatment of cancer.

Mounting evidence supports the link between psychological health and cardiovascular disease (Chapter 26). The impact of psychosocial stressors on cardiovascular risk appears to be stronger in women than in men, and has been associated with increased inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, activated hypothalamus-pituitaryadrenal axis, and unhealthy behaviors. Clinicians providing care to patients with or at risk for cardiovascular disease must familiarize themselves with the impact of psychosocial stressors on their patients’ cardiovascular health.

The numbers and classes of medications used in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease increase on nearly a daily basis. Many of these medications have differing pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and side effect profiles in men and women (Chapter 27).

Throughout the book, disparities in cardiovascular care are emphasized in their respective chapters. In Chapter 28, the authors assess the current landscape of cardiovascular care and directly address these disparities. Racial disparities persist with regard to the presence and treatment of hypertension, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure risk factors. Black women often experience worse outcomes compared to age-matched black or white men. These differences are related to both biological differences and socioeconomic determinants of health. We must recognize gaps in care in order to effectively develop strategies to minimize them so that we may provide more equitable

care to all our patients. The book closes with Chapter 29 This chapter contains a detailed discussion of future directions including sex-specific pathways of cardiovascular care. The emergence of women’s heart programs has not only advanced care for women with cardiovascular disease but also raised awareness about sex differences in prevention, presentation, and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Shining a light on and addressing these differences through innovation and modification of our care platforms will hopefully lead to improved outcomes for all of our patients. We were in the midst of editing and reviewing the chapters when we received the news of the impending COVID-19 pandemic. We recognize that the impact of this unprecedented health concern has been felt across the globe. We are so appreciative of all healthcare workers and in particular the authors of chapters in this book. They all continued to take care of patients and their families while writing their contributions to this book. We recognize the increasing evidence that there are sex differences in risk

for and responses to the COVID-19 virus; however, much of this information came to light as this book was going to press. In an effort to keep this book current and to publish it on time, COVID-19-related topics will not be covered in this edition, but will most certainly provide historic perspective of this pandemic in future editions.

We hope the book will help clinicians, researchers, and public health experts to recognize the unique aspects of sex-specific CVD and form a substantial knowledge base and foundation for improved and equitable CVD care in both men and women. We believe this book will be a useful resource for a wide variety of practitioners, cardiologists, oncologists, gynecologists, family practitioners, internists, pharmacists, physician assistants, and respective trainees, who treat men and women with heart disease.

Niti R. Aggarwal, MD

Malissa J. Wood, MD

Introduction: Past, Present, and Future of Heart Disease in Men and Women

Nanette K. Wenger

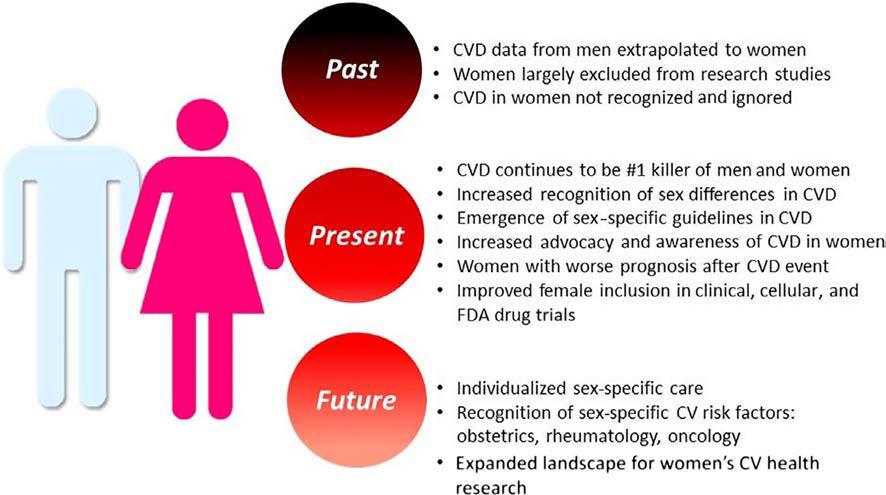

For most of the 20th century, cardiovascular disease was addressed as a problem for men, with coronary disease and myocardial infarction the foremost morbid and mortal problems. Women were widely considered protected from heart disease (absent evidence-based data) by their hormones in the premenopausal years and by the subsequent widespread application of menopausal hormone therapy. Although women in the Framingham Heart Study had a higher incidence of angina, this was overwhelmed by the predominance of myocardial infarction in men, with its attendant 40% hospital mortality. Angina was not viewed as a serious problem. Hypertension had yet to be accepted as a lethal condition, and heart failure prevalence would only increase in subsequent years consequent to the increased survival of both women and men from more acute cardiovascular problems. Not surprisingly, the emergence of clinical research studies and in particular randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular prevention and therapies involved exclusively or predominantly men and typically middle-aged white men. Stroke was considered untreatable and not widely accepted as a common consequence of uncontrolled hypertension. Rheumatic heart disease with its surgically amenable mitral stenosis predominated in women, and the problem of cardiac arrhythmias, and in particular atrial fibrillation, had yet to receive widespread acknowledgment. Ignored was the fact that the more women than men died annually from cardiovascular disease, a statistic that persisted until 2013–2014 (Figure 1).

The 1992 NHLBI Conference: Cardiovascular Health and Disease in Women highlighted the flawed assumption that women did not experience heart disease until elderly age and were not as seriously at risk as men. It presented new information appropriate for clinical application but identified knowledge gaps that impeded quality cardiovascular care for women, displaying a research agenda for the next decades [1]. The importance of sex and gender differences in cardiovascular disease was promulgated by the 2001 IOM report “Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health. Does Sex Matter?” [2], which advocated

Sex Differences in Cardiac Disease. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819369-3.00010-1

the need for the evaluation of sex-based differences in human disease and in medical research, with translation of these differences into clinical practice.

Not until the late 1990s and early 2000s did the randomized controlled trials of menopausal hormone therapy including the Heart and Estrogen Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) in women with heart disease and the hormone trials of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) in healthy women [3–5] identify that menopausal hormone therapy did not prevent incident or recurrent cardiovascular disease and thus was not indicated for primary or secondary prevention. The importance of these trials was the refocusing of attention on established cardiovascular preventive therapies for women.

Yet, as recently as 2003, the AHRQ “Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of CHD in Women” [6, 7] displayed that most contemporary recommendations for the prevention, diagnostic testing, and medical and surgical treatment of CHD in women were extrapolated from studies conducted predominantly in middle-aged men and that there remained fundamental knowledge gaps regarding the biology, clinical manifestations, and optimal management strategies for women.

Advocacy also increased the awareness of cardiovascular disease in women, beginning with the NHLBI Heart Truth Campaign in 2004 and the American Heart Association’s Go Red for Women Initiative in the same year, as well as the work of WomenHeart, the National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

Subsequent clinical research studies provided data specifically for women, such as the Women’s Health Study, showing that aspirin provided stroke protection but not protection from MI [8], contrary to data for men in the Physician’s Health Study.

Gender-specific data derived from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Registry of women with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome [9] demonstrated that the

FIGURE 1 The Past, Present, and Future of Heart Disease in Men and Women. CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDA, Food and Drug Administration. Image courtesy of Niti R. Aggarwal.

prognosis with an acute coronary syndrome was worse in women who incurred an increase in hospital death, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and the need for transfusion. Yet women were less likely to receive coronary interventions and guideline-based medical based therapies despite their high-risk status. The question was raised as to whether the worse prognosis for women was related to their raised baseline risk or to suboptimal admission and discharge therapies: was this biology, bias, or both?

A concept-changing paradigm derived from the NHLBI Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. At the time, women with abnormal noninvasive diagnostic studies, in the absence of obstructive disease of the epicardial coronary arteries at angiography, were considered to represent a “false-positive” noninvasive test, based on the male model of disease [10, 11]. Subsequent data from the WISE cohorts identified that myocardial ischemia was the villain, associated with adverse clinical outcomes in women in the absence of obstructive coronary disease, today termed INOCA [12]. This highlighted the importance of microvascular disease and nonobstructive coronary disease in women, with current research actively targeting the optimal diagnostic procedures to identify this complex pathophysiologic spectrum. Clinical studies are currently underway to attempt to improve the outcome of women with microvascular disease and nonobstructive coronary artery disease, with unimpressive data yet forthcoming [13, 14].

The Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study (WACS) and the Women’s Antioxidant with Folic Acid Study (WAFACS) [15, 16] identified that vitamin C and beta carotene as well as folic acid and vitamin D supplements did not prevent incident or recurrent cardiovascular disease in women and removed these ineffective therapies from the recommended regimens. Shortly thereafter, the AHA Women’s CVD Prevention Guideline 2011 Update [17] highlighted that pregnancy complications, specifically preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm delivery, and small for gestational age infants were all early indicators of an increase in cardiovascular risk, placing a detailed history of pregnancy complications as a routine component of risk assessment for women. At the same time, this guideline identified an increased risk of cardiovascular disease with systemic autoimmune collagen vascular disease, warranting screening for conventional coronary risk factors and interventions as appropriate. The 2011 Update of the Cardiovascular Prevention Guideline also addressed stroke prevention in women with atrial fibrillation, stating that atrial fibrillation increased the stroke risk 4–5 fold and that undertreatment with anticoagulants doubled the risk of recurrent stroke.

More recently, a report from the Get With the Guidelines CAD database [18] showed women to have a doubled STEMI mortality compared with their male peers, 10.2% vs. 5.5%. This was predominantly an initial 24-h increase in mortality and was associated with a decrease in the applica-

tion of early aspirin, beta blockers, reperfusion therapy, and timely reperfusion. It was not that physicians chose to treat their women patients differently, but rather this represented a lack of recognition of ST-elevation myocardial infarction; remediation of this problem offered opportunities to lessen gender disparities in care and improve clinical outcomes for women.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2010 Report on Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise [19] further highlighted that medical research historically neglected the health needs of women, even though there was major progress in reducing cardiovascular mortality. It identified that women were not a homogeneous group, with disparities in disease burden among subgroups of women, particularly those socially disadvantaged because of race, ethnicity, income level, and educational attainment. The IOM highlighted that the lack of analysis and reporting of sex-stratified analyses limited the ability to identify potentially important sex and gender differences, including differences in care, and advocated for translation of women’s health research findings into both clinical practice and public health policies, with effective communication of research-based health messages to women, the public, providers, and policy makers.

The result of the emerging sex-specific research and recommendations was stunning. Until the year 2000, the decline in cardiovascular mortality in the United States occurred predominantly in men, but beginning in 2000, the cardiovascular mortality decline was more prominent in women and, as previously noted, for the first time in 2003–2014 fewer women than men died annually from cardiovascular disease.

But all this may not bode well for the future—since that time there has been a leveling or increase of cardiovascular mortality for both women and men, predominantly in the younger age groups 35–50 years of age, likely reflecting the US epidemic of obesity and sedentary lifestyle.

Women’s participation and data in clinical trials remains a challenge, with a Cochrane review of 258 cardiovascular clinical trials showing that only one-third examined outcome by sex, although among those with sex-based analyses, 20% reported significant differences in outcomes between women and men [20]. Worthy of mention is that the exclusion of elderly patients from clinical trials doubly disadvantages women, who have their predominance of coronary and other cardiovascular events at older age. Promise for the future is offered by HR2101: The Research for All Act of 2015, 114th Congress (2015–2016). In addition to the mandate by the Government Accountability Office to update reports on women and minorities in medical research at both the NIH and the FDA, the National Institutes of Health were legislatively ordered to update guidelines on

the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research. Of equal importance, they were mandated to ensure that both male and female cells and tissues, as well as animals, be included in basic research, with the results disaggregated according to sex and sex differences examined. Similarly, the FDA was mandated to ensure that clinical drug trials for expedited drug approval were sufficient to determine the safety and effectiveness for both women and men, with the outcomes supported by the results of clinical trials that separately examined outcomes for women and men.

The past decade has seen Scientific Statements on women and peripheral artery disease [21]. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Women [22] define sex-specific stroke risk factors including pregnancy, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, oral contraceptive use, menopausal hormone use and changes in hormonal status, as well as risk factors that were stronger or had an increased prevalence in women. The role of noninvasive testing in women for the clinical evaluation of suspected ischemic heart disease received repeated attention [23, 24], as did the sex differences in the cardiovascular consequences of diabetes mellitus showing that the gender advantage of a decrease in cardiovascular events in women compared with comparably aged men was lost in the context of type 2 diabetes [25].

Also highlighted was the intersection of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer, targeting their overlapping risk factors and the risk that current breast cancer treatments may accelerate cardiovascular disease and resultant left ventricular dysfunction, and identifying the need for surveillance, prevention, and secondary management of cardiotoxicity during breast cancer treatment [26]. Most recently, a cooperation between the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [27] cited that 90% of US women have at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease, with women less likely to receive guideline-recommended therapies and advocating that healthy lifestyles and behaviors should be discussed at each OB/GYN visit with enhanced screening for cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors. Shared information should be used to assess risk, initiate interventions, and facilitate significant lifestyle changes.

The ideal vision for women’s cardiovascular health research in the next decade is that the landscape must be expanded to include beliefs and behaviors; local, national, and global community issues; economic and environment issues; ethical aspects; legislative and political issues; public policy; and societal/sociocultural variables. All these can only be ascertained by examining gender differences in cardiovascular disease, with the application of personalized or individualized medicine beginning with sex-based examination of differences.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd: