CONTRIBUTORS

Stefan Richard Bornstein, MD, PhD

Division of Internal Medicine and Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism

University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus

Technical University of Dresden

Dresden, Germany

Jan Calissendorff, MD, PhD

Senior Consultant

Department of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes

Karolinska University Hospital

Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery

Karolinska Institutet

Stockholm, Sweden

Stuart Campbell, MD, MSc

Resident

Division of Endocrine Surgery, Department of Surgery

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

Tariq Chukir, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism

Weill Cornell Medicine and New York

Presbyterian Hospital

New York, New York

Tara Corrigan, MHS, PA-C

Physician Assistant

Division of Endocrine Surgery, Department of Surgery

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

Henrik Falhammar, MD, PhD, FRACP

Department of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes

Karolinska University Hospital;

Associate Professor

Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery

Karolinska Institutet

Stockholm, Sweden

Azeez Farooki, MD

Attending Physician

Endocrinology Service

Department of Medicine

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

New York, New York

Chelsi Flippo, MD

Pediatric Endocrinology Fellow

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Lane L. Frasier, MD, MS

Fellow, Surgery

Division of Traumatology, Surgical Critical Care & Emergency General Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Vincent Gemma, MD

Major Health Partners

Department of Surgery

Shelbyville Hospital

Shelbyville, Indiana

Monica Girotra, MD

Associate Clinical Member

Endocrine Service, Department of Medicine

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center;

Assistant Clinical Professor

Endocrine Division

Weill Cornell Medical College

New York, New York

Ansha Goel, MD

Endocrinology Fellow

Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism

Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, District of Columbia

Christopher G. Goodier, BS, MD

Associate Professor

Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina

Heidi Guzman, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Columbia University Irving Medical Center

New York, New York

Makoto Ishii, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Neurology

Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute

Weill Cornell Medicine

New York Presbyterian Hospital

New York, New York

Yasuhiro Ito, MD, PhD

Kuma Hospital

Department of Surgery

Kobe, Japan

Michael Kazim, MD

Clinical Professor

Oculoplastic and Orbital Surgery

Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute

Columbia University Irving Medical Center

New York-Presbyterian Hospital

New York, New York

Jane J. Keating, MD

Division of Traumatology, Surgical Critical Care & Emergency General Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Anupam Kotwal, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism

University of Nebraska Medical Center

Omaha Nebraska; Research Collaborator

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Nutrition

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota

Svetlana L. Krasnova, APRN, FNP-C, RNFA

Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

New Brunswick, New Jersey

David W. Lam, MD

Assistant Professor

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Bone Disease

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

New York, New York

Melissa G. Lechner, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism

David Geffen School of Medicine

University of California at Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

Aundrea Eason Loftley, MD

Assistant Professor

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases

Department of Internal Medicine

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina

Sara E. Lubitz, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Medicine

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

New Brunswick, New Jersey

Louis Mandel, DDS

Director

Salivary Gland Center;

Associate Dean, Clinical Professor (Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery)

Columbia University College of Dental Medicine

New York, New York

Hiroo Masuoka, MD, PhD

Department of Surgery

Kuma Hospital Kobe, Japan

Jorge H. Mestman, MD

Professor of Medicine and Obstetrics & Gynecology

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

Department of Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynecology

Keck School of Medicine

University of Southern California

Los Angeles, California

Akira Miyauchi, MD, PhD

Department of Surgery

Kuma Hospital

Kobe, Japan

Caroline T. Nguyen, MD

Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Division of Endocrinology

Diabetes & Metabolism

Department of Medicine

Keck School of Medicine

University of Southern California

Los Angeles, California

Raquel Kristin Sanchez Ong, MD

Endocrinologist, Fellowship Assistant

Program Director

Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey;

Assistant Professor

Department of Internal Medicine

Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine

Nutley, New Jersey

Randall P. Owen, MD, MS, FACS

Chief, Section of Endocrine Surgery

Division of Surgical Oncology

Program Director, Endocrine Surgery Fellowship

Department of Surgery Mount Sinai Hospital

Icahn School of Medicine

New York, New York

Rodney F. Pommier, MD

Professor of Surgery

Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland, Oregon

Jason D. Prescott, MD, PhD

Chief, Section of Endocrine Surgery

Director of Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery

Assistant Professor of Surgery and of Oncology

Department of Surgery

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Ramya Punati, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine

Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism

Pennsylvania Hospital University of Pennsylvania Health System Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Gustavo Romero-Velez, MD

Chief Resident

Department of Surgery

Montefiore Medical Center

Albert Einstein School of Medicine

Bronx, New York

Arthur B. Schneider, MD, PhD

Professor of Medicine (Emeritus)

Department of Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, Illinois

Alison P. Seitz, MD

Resident Department of Neurology

Weill Cornell Medicine

New York Presbyterian Hospital

New York, New York

Alexander L. Shifrin, MD, FACS, FACE, ECNU, FEBS (Endocrine), FISS

Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

New Brunswick, New Jersey; Associate Professor of Surgery

Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine

Nutley, New Jersey; Director of Endocrine Oncology

Hackensack Meridian Health of Monmouth and Ocean Counties

Hackensack, New Jersey; Surgical Director, Center for Thyroid, Parathyroid, and Adrenal Diseases

Department of Surgery

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

Adam Michael Shiroff, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Division of Traumatology, Surgical Critical Care & Emergency Surgery

University of Pennsylvania

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Marius N. Stan, MD

Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Nutrition

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota

Constantine A. Stratakis, MD, D(med)Sci

Senior Investigator

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Christina Tatsi, MD, PhD

Staff Clinician, Pediatric Endocrinologist

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Daniel J. Toft, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor

Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

Department of Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, Illinois

Arthur Topilow, MD, FACP

Department of Hematology Oncology

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

Ann Q. Tran, MD

Oculoplastic and Orbital Surgery

Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute

Columbia University Irving Medical Centery

New York-Presbyterian Hospital

New York, New York

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

When a skin wound exists, it is better to remove the horn and bony fragment, and to apply an antiseptic dressing in order to prevent infection of the frontal sinus.

EXOSTOSES.

SPAVIN IN THE OX.

F��. 12.—Dressing for fracture of the base of the horn.

Exostoses are somewhat uncommon in the bovine species, and when they occur are rarely of great clinical interest. Nevertheless, in cows and old working oxen one sometimes sees metatarsal spavin. Its gravity, however, appears to be very much less than in the horse, on account of its position. Very commonly there is only trifling lameness.

Treatment by application of biniodide of mercury ointment or the actual cautery gives good results. The principal precaution required is to prevent the animals licking the parts.

RING-BONE.

Ring-bones only occur in working oxen, and particularly in aged animals used in hilly regions. They result almost exclusively from wounds, ligamentous and tendinous strains, and articular injuries.

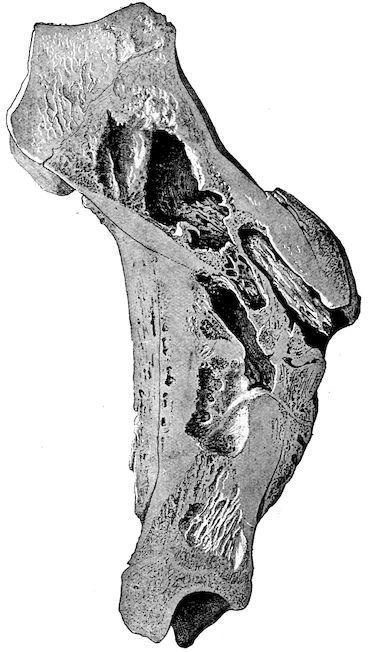

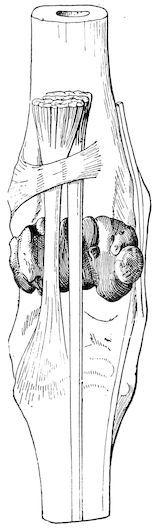

F��. 13. Tibia. Lesions due to open fracture and displacement. Irregular callus formation and segnestrum.

They are preceded (as can usually be proved by dissection of limbs) by fibrous or fibro-cartilaginous induration in or about the coronet or one of the phalanges. These thickenings increase the diameter of the pastern in all directions. Ring-bones are seldom very large; but as they partially or entirely surround the insertions of the lateral ligaments, inter-phalangeal articulations or insertions of the digital extensors, they are painful, and produce lameness of varying intensity.

Diagnosis is easy, partly because the tension of the skin and the fibrous thickening render palpation painful.

Prognosis is grave, because the effect of ring-bone is sometimes to render working animals useless.

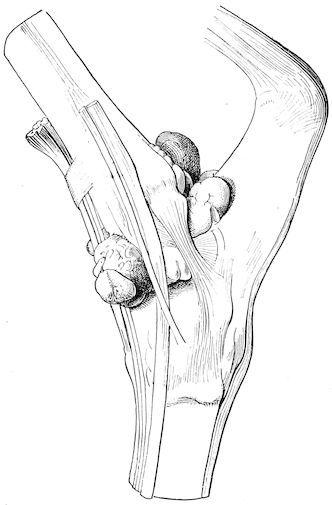

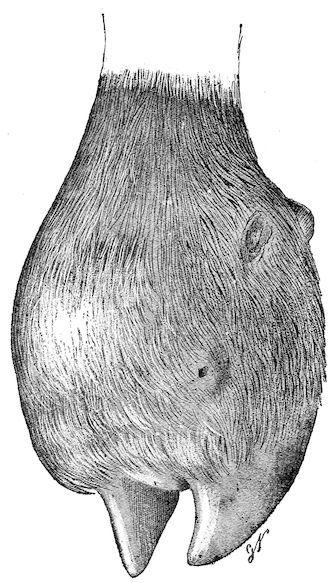

F��. 14.—Sarcoma of the periosteum beneath the scapula.

F��. 15.—Sarcoma of the periosteum covering the upper end of the tibia.

Tr eat me nt. To relie ve the dise ased claw of pres sure due to its beari ng on the grou nd, the shoe shou ld be removed and the claw freely pared. If necessary, the healthy claw of the same foot may be raised by placing a piece of thick leather between the sole and the shoe. It is advisable at once to apply an energetic plaster, or, better still, to resort to firing in points.

SUPPURATING OSTITIS.

In addition to the changes in bone resulting from rachitis, osseous cachexia, tuberculosis, and actinomycosis, one sometimes sees cases of periostitis or ostitis pure and simple. As a result of external injury or direct wounds, the bone may be contused and injured, becoming

the seat of diffused periostitis, necrosis, suppurating ostitis or osteomyelitis. Open fractures may produce the same results.

Treatment comprises disinfection of wounds, antiseptic injection of fistulæ, the application of antiseptic pencils, curettage, the removal of sequestra, and vesicant or resolvent complications. When such conditions extend to neighbouring joints and produce suppurative arthritis, the animals ought to be killed.

BONE TUMOURS.

The only bone tumours of real importance from a practical point of view are malignant growths represented by rapidly spreading epitheliomata or sarcomata, originating in the periosteum. Fortunately such tumours are rare.

They are not difficult to diagnose, as they develop rapidly, are accompanied by pain and lameness ending in diminution or loss of the power of movement, and frequently attack neighbouring lymphatic glands. Even when in good condition, animals lose flesh and appetite, and finally die of general wasting. The diagnosis is sufficiently guided by the deformity of the parts, the bosselated appearance of the tumours, the absence of fluctuation, the hæmorrhage which follows exploratory puncture, the character of the little fragments of tissue removed through these punctures, and finally the leukocytosis, which accompanies the development of malignant tumours.

The prognosis is grave, for it is usually difficult or out of the question to have recourse to removal, resection or amputation, when the tumours have acquired any considerable size. Success is impossible unless intervention is early, and the growth is in a readily accessible part. In other circumstances early slaughter is indicated.

CHAPTER II.

DISEASES OF THE FOOT.

CONGESTION OF THE CLAWS.

Congestion of the claws is not infrequently confused with contusion of the sole. It is, however, essentially different, and presents closer analogies with laminitis. The condition is characterised by congestion of the entire vascular system of the claw and principally of the velvety tissue. Like laminitis, it affects all four limbs; in rare cases the two front or two hind.

Congestion of the claw results almost exclusively from enforced movement on hard, dry and hot ground. It is commoner in animals unaccustomed to walking, and in heavy beasts which have been travelled considerable distances to attend fairs or markets. It is commonest in the bovine and porcine species, and less common in sheep.

The symptoms appear after animals return from a long journey by road. They are characterised by unwillingness to bear weight on the feet and difficulty in movement. Standing is painful, and the animals resist being moved; as soon as released they lie down.

Diagnosis presents no difficulty, though the condition is sometimes mistaken for slight laminitis.

Prognosis is favourable.

Absolute and prolonged rest is always followed by recovery, no internal medication being necessary, though this result is promoted by enveloping the claws in wet compresses or by using cold foot baths, etc.

CONTUSIONS OF THE SOLE.

Contusions of the sole are only seen in animals which work without shoes or in such as are badly shod.

Work on rocky ground, movement over newly metalled roads, and wounds produced by sharp stones, are the principal causes of contusion of the sole. Badly applied shoes, flat or slightly convex on their upper surfaces, may also produce bruising in the region of the sole. The anterior angle of the claw is rarely affected.

Lameness is the first symptom to attract attention. It is slightly marked, unless the bruising has been overlooked until suppuration has set in. It affects only one or two limbs, and is rarely accompanied by general disturbance, such as loss of appetite, fever, exhaustion during work, etc.

Locally the claw or claws affected are abnormally sensitive to percussion of the wall, and particularly to compression of the sole.

The parts are hot to the hand, and thinning the sole with a knife shows little perforations, irregular points and crevices in the horn. One may also find softening, infiltration and hæmorrhage within the horn similar to those of corn in the horse, undermining of the sole over limited areas, and sometimes suppuration, if the animals have been forced to work when lame.

Complications like necrosis of the velvety tissue or of the bone, though comparatively common in the horse, are rare in oxen.

Diagnosis is not difficult provided the history of the case is known. Confusion with laminitis is scarcely possible, for the gait of this lameness and the local symptoms are all different. Examination of the sole will usually dispel any remaining doubt.

Prognosis. The prognosis is favourable. When the horn is simply softened and a blackish liquid transudes, the lesion is trifling; if the discharge is reddish grey the lesion is graver, and implicates all the velvety tissue; finally, separation of the horn from the secreting membrane and the discharge of true pus point to death of the keratogenous tissue or of the bone.

Treatment should be commenced by carefully thinning the sole around the wound and applying moist antiseptic dressings or cold affusions. Removal of loose portions of horn hastens repair by allowing discharge, which has accumulated between the living tissues and the horn itself, to escape freely. The extirpation of

necrotic tissue and the application of surgical dressings are only called for in specially grave cases.

This treatment usually gives good results. The acute complications which are so common and so dangerous in the horse seldom occur in the ox.

Most of these operations can be performed without casting, provided the animal is placed in a trevis or is sufficiently secured.

LAMINITIS.

Laminitis is characterised by congestion, followed by inflammation of the horn-secreting tissues of the foot. It is now rare in oxen and very seldom assumes an acute form. The slow pace at which animals of the bovine species move may sufficiently explain this rarity; nevertheless, prolonged travel on stony roads with heavy vehicles, rapid and repeated marches to towns or important fairs, are sufficient to produce attacks. Before the days of railways, and for some time after their introduction, in Britain cattle were travelled by road, and laminitis was common.

Long journeys in crowded railway trucks may also produce the disease, although the animal has not been forced to walk. Persons engaged in exhibiting cattle at shows are well aware of this. Prolonged maintenance of the standing position will produce the trouble, to which the joltings of the railway journey may also contribute their share. Prolonged standing on board ship may induce laminitis.

“Show condition” and the consumption of highly nitrogenous, and particularly of farinaceous, foods favour the occurrence of laminitis. Breed is also considered to have some influence, and laminitis is said to occur more frequently in animals raised in flat districts, because in their case the space between the digits is larger than in mountain-bred cattle. In this connection the body weight may perhaps play a certain part.

The symptoms vary somewhat, depending on whether laminitis is general and affects all four feet, or restricted to the two front or the two hind feet.

The internal claws always seem more severely affected and more sensitive than the external. In very rare cases the animal remains standing, but usually it lies down, and will only rise under strong compulsion.

When standing, the symptoms are similar to those noted in the horse; the animal appears as though absolutely incapable of moving. If all four feet are affected the animal assumes a position as though just about to rise; if the front feet alone are affected the animal kneels in front whilst it stands on its hind legs, a very unusual position for the ox to assume; finally, if the hind feet alone are affected, the animal seems to prefer a position with the feet under the body both in front and behind. (See Veterinarian, 1894, case by Bayley, and note by Nunn.)

It is always difficult to make the animal move. Walking seems painful, and most weight is thrown on the heels. The body swings from side to side as the limbs are advanced, and each limb is moved with a kind of general bodily effort.

The claws are hot, sensitive to the slightest touch, and painful on percussion.

Throughout the development of laminitis the general symptoms are very marked. The appetite falls off early, fever soon appears, and in grave cases the temperature rises to 105° or to 106° Fahr. Thirst is marked, and the animal seems to prefer cold drinks. The muzzle is dry, the face anxious and expressive of pain. Wasting is rapid.

The ordinary termination is in resolution, which occurs between the eighth and fifteenth day, provided the patient has been suitably treated. The disease rarely becomes chronic. On the other hand, the claw occasionally separates, as a consequence of hæmorrhage or suppuration, between the horn proper and its secreting membrane. Should this complication threaten, the pastern becomes greatly swollen, the extremities become intensely congested, and separation commences at the coronet. Loss of the claws, however, like suppuration, is rare.

Diagnosis. Congestion of the sole, the early stage of infectious rheumatism and osseous cachexia may, at certain periods of their development, be confused with laminitis; but the history and the

method of development of the above-mentioned diseases always allow of easy differentiation.

It should, however, be added that, in certain exceptional conditions (suppurating echinococosis, producing chronic intoxication, tumours of the liver, and tumours of the pericardium and mediastinum), symptoms may be shown that suggest the existence of laminitis, although it is not really present. In these cases pain may possibly be felt in the bones of the extremities.

The prognosis is usually favourable, but necessarily depends on the intensity of the disease. Fat stock always suffer severely.

The treatment varies in no important particular from that prescribed for the horse, and is usually followed by rapid improvement. The chief indications are free bleeding from the jugular, the application of a mustard plaster over the chest, and the administration of a smart purgative (1 to 2 lbs. of sulphate of soda, according to the size of the animal) at first, followed by laxatives. This treatment may be completed by giving salicylate of soda per os in doses of 5 to 8 drams, or arecoline in subcutaneous injection, 1 to 1½ grains. Local treatment consists in cold affusions or poultices to the feet.

Failing cold baths, clay plasters applied to the feet are useful. To ensure success all these methods should be utilised simultaneously. In cases of separation of the claw, antiseptic dressings, with a thick pad of tow placed under the sole, become necessary.

Chronic laminitis may perhaps occur in the ox as in the horse, but, as a rule, oxen are slaughtered before the disease can assume this form. In dealing with fat, or even with fairly well-nourished, oxen it would clearly be more economical to slaughter early, and so prevent wasting and the resulting loss from disease.

SAND CRACK.

Sand crack—that is to say, the occurrence of vertical fissures in the wall of the claw—is not absolutely rare in bovines. It is commonest in working oxen drawing heavy loads, though in very exceptional cases it affects animals which have never worked. (Moussu describes one case in a young ox where four sand cracks existed simultaneously.) It

may also result from injuries to the coronet. In contrast to the case of the horse, and owing to the different conditions under which the ox performs its work, the disease is commoner in front than in hind feet. In drawing, the ox’s front limbs play the principal part, and the animal pivots, so to speak, on the claws of the front limbs.

The position of the crack may vary. It is commonest on the inner surface of the claw, rare at the toe, and still rarer at the quarter. It is often superficial and complete, extending throughout the entire height of the claw, but not throughout its thickness; sometimes it is complete and profound, the fissure then extending to the podophyllous tissue.

The symptoms are purely local in the case of superficial lesions. When the injury is deep seated, or when it originates in a wound of the coronet, lameness is present. Intense lameness, swelling of the coronet, and blood-stained or purulent discharge point to grave injury and probable complications.

Diagnosis is easy. The prognosis naturally varies with the symptoms. It is favourable when the fissure is merely superficial, but becomes grave when it is deep seated and the animal is exclusively used for heavy draught.

Treatment. When the lesion is superficial and unaccompanied by lameness, no surgical interference is necessary. Rest or very light work is alone required. As soon as lameness appears, rest is obligatory. The application of antiseptic poultices, containing 2½ to 3 per cent. of carbolic acid, creolin, etc., usually alleviates pain in a short time, and facilitates healing in the depth of the fissure.

In exceptional cases, where complications have occurred in consequence of suppuration beneath the fissure, suppuration in the coronary region, or necrosis of the podophyllous tissues, an operation becomes necessary, and is of exactly similar character to that performed under like circumstances in the horse.

Over a space of 1 to 1½ inches on either side of the fissure the horn is thinned “to the blood,” and the subjacent dead tissue removed. The claw is then thoroughly cleansed with some antiseptic solution, the wound freely dusted with equal parts of iodoform, tannin and boric acid, and covered with pads of tow or cotton wool, fixed in position by appropriate bandages. After such operations a long rest is

essential for complete recovery, during which, however, the animal may be fattened.

The object of operation is to prevent complications, like chronic suppuration and necrosis, which would endanger the animal’s life, rather than to effect perfect restoration of usefulness for the work previously done.

PRICKS AND STABS IN SHOEING.

The wall of the ox’s claw is so thin that shoeing is always somewhat difficult, more especially as nails can only be inserted in the external wall. Moreover, as very fine nails must be used, they are apt to bend, penetrate the podophyllous tissue, and cause injuries of varying importance. The ox is often very restless when being shod, and, even though firmly fixed, usually contrives to move the foot every time the nail is struck. The farrier, therefore, may easily overlook the injury which he has just caused, and by proceeding and ignoring it may transform a simple stab into a much more dangerous wound.

Symptoms. In most cases lameness appears immediately the animal leaves the trevis, but, although this is more difficult to explain, lameness is sometimes deferred until the day after, or even two days after, shoeing. Though little marked at first, lameness may become so severe that the animal cannot bear the pain caused by the foot touching the ground. When this stage is reached general disturbance becomes marked, fever sets in, rumination stops, and appetite is lost.

These symptoms point to the occurrence of suppuration. The pus, confined within the horny covering of the foot, causes very acute suffering and sometimes grave general disturbance; later it burrows in various directions, separating the podophyllous tissue from the horn, and ends by breaking through “between hair and hoof” in the region of the coronet. In exceptional cases, complications such as necrosis of the podophyllous tissue extending to the bone, and suppuration of its spongy tissue, may be observed.

Diagnosis. When the farrier suspects he has pricked an animal the immediate withdrawal of the nail will remove any doubt, because bleeding usually follows. If the condition is only detected at a later

stage, the early lameness having been misinterpreted, examination of the claw and tapping the clenches of the nails will cause the animal to show pain at a given point, thus indicating the penetration of the nail. Removal of the offending nail is painful, and is often followed by discharge of pus or blood-stained fluid, which clearly points to the character of the injury. In obscure cases the shoe should not be reapplied.

When the horn wall is separated from the sensitive structures, there is marked general disturbance, and pus is discharging at the coronet, it is practically impossible to err in diagnosis.

Prognosis. In cases of simple nail puncture the prognosis is hopeful, provided that the condition is at once diagnosed. The longer it remains unrecognised, particularly if complication like necrosis has occurred, the graver becomes the outlook.

Treatment. In cases of simple puncture the nail should immediately be withdrawn and the animal placed on a perfectly clean bed to prevent the wound becoming soiled or infected. If lameness appear and become aggravated, the shoe should be removed and antiseptic poultices applied. In the majority of cases the lameness will then diminish, and in a few days completely disappear.

In cases of discovery within the first few days the same treatment is applicable, and is often sufficient. If, on the contrary, pus is discharging at the coronet, if lameness is intense and the general symptoms marked, it may be needful to operate.

The stages of operation comprise: thorough thinning of the horn in the shape of an inverted V over the affected portion of the wall, removal of the loose necrosed parts, disinfection of the wound, and the application of a surgical dressing covering the entire claw.

PICKED-UP NAILS, Etc. (“GATHERED NAIL.”)

Penetrating wounds of the plantar region are, as in the horse, usually included under the heading of “Picked-up Nails.” They are only seen in oxen or cows which are not shod. Pointed objects, like nails, harrow teeth, sharp fragments of wood or glass, etc., may produce injuries of the character of that now in question.

In considering the position of such wounds we may for convenience divide the plantar region into two zones, one extending from the toe of the claw to the point of insertion of the perforans tendon, the other comprising the region between this insertion and the bulb of the heel.

Symptoms. Lameness occurs immediately, and varies with the intensity of the existing pain. If the offending body has not remained fixed in the wound, this lameness may in a few moments disappear, either for good or merely for a time. The recurrence of lameness on the following day or a couple of days later marks the commencement of inflammatory changes in the deeper seated tissues. This lameness in many instances is accompanied by a movement suggestive of stringhalt, the foot being kept on the ground only for a very short time, or sometimes not being brought into contact with the ground at all.

The depth to which the offending object has penetrated, and the direction it has taken, may sometimes be discovered by a mere casual examination of the sole. In other cases only the orifice by which it has penetrated can be found. If the injury has existed for several days, the discharge from the puncture will be thin and blackish, purulent, or blood-stained, according to the case. Fever and general systemic disturbance suggest an injury of a grave character.

Diagnosis. The diagnosis is easy, inasmuch as the lameness almost directs examination to the foot.

Prognosis is rarely grave. The direction, the situation and mode of insertion of the flexor tendon, which forms the plantar aponeurosis, ensure this aponeurosis being rarely injured by objects penetrating from without. The points of the offending bodies usually pass either forwards to the phalanx or backwards in the direction of the plantar cushion.

Treatment. The first stage in treatment consists in removing the foreign body and thoroughly thinning the neighbouring horn. An antiseptic poultice consisting of linseed meal saturated with 3 per cent. carbolic acid or creolin solution is then applied. Considerable and progressive improvement usually takes place in a few hours. If lameness persists, surgical interference becomes necessary; in the anterior zone it is confined to removing any dead portions of the velvety tissue and to extirpating the fragment of bone which has

undergone necrosis. In the posterior zone the sinus must be probed and laid open, so that all the diseased parts can be treated as an open wound.

If, as happens in exceptional cases, the plantar aponeurosis is found to be severely injured, the complete operation for picked-up nail, as practised in the horse, may be performed, or the claw may be amputated. In the former operation the horn covering the sole is first thinned “to the blood.”

The stages of operation are as follows:—

(1.) Ablation of the anterior portion of the plantar cushion. Transverse vertical incision at a distance of 1¼ inches in front of the heel; excision of the anterior flap.

(2.) Transverse incision and ablation of the plantar aponeurosis by the same method.

(3.) Curettage of the point of implantation of the aponeurosis into the bone.

(4.) Antiseptic dressing of the claw.

Finally, if the primary lesion, wherever it may have started, has become complicated by arthritis of the inter-phalangeal joint, it will be necessary to remove the claw, or, better still, to remove the two last phalanges, the latter operation being easier than the former, and providing flaps of more regular shape and better adapted for the production of a satisfactory stump.

INFLAMMATION OF THE INTERDIGITAL SPACE.

(CONDYLOMATA.)

Condylomata result from chronic inflammation of the skin covering the interdigital ligament. Any injury to this region causing even superficial damage may result in chronic inflammation of the skin and hypertrophy of the papillæ, the first stage in the production of condylomata.

Injuries produced by cords slipped into the interdigital space for the purpose of lifting the feet when shoeing working oxen are also fruitful causes.

Inflammation of the interdigital space is also a common complication of aphthous eruptions around the claws and in the space between them. Continual contact with litter, dung and urine favour infection of superficial or deep wounds, and by causing exuberant granulation lead to hypertrophy of the papillary layer of the skin. When the animal stands on the foot the claws separate under the pressure of the body weight and the condylomata are relieved of pressure. When, however, the limbs are rested, the claws mutually approach, compress the abnormal vegetations, flatten, excoriate, and irritate them, thus favouring their further development.

The symptoms are easy to detect. The animals appear in perfect health, but have difficulty in walking, and show pain. They walk as though on sharp, rough ground, and lameness is sometimes severe. Locally, the anterior surface of the claws and the interdigital space are markedly congested and sensitive, or painful on pressure. The growths are of varying size, isolated or confluent, bleeding, excoriated, or covered with horn, and are visible between the claws when the animal stands on the limb. In many cases they form a perfect cast of the vertical interspace. When the superficial layers

F��. 16. Condylomata of the interdigital space and sidebones.

have undergone conversion into a horn-like material, lameness diminishes or disappears.

Diagnosis presents no difficulty.

Prognosis is only grave in so far as the condition interferes with animals working, but it may render working oxen entirely useless.

Treatment in the early stages is of a preventive character, and consists in placing animals which have been accidentally injured or attacked with foot-and-mouth disease on a perfectly clean bed.

Surgical treatment is the only reliable method in cases where hypertrophy of the papillary layer is well marked, and is extremely simple.

The animal should be fixed in the trevis, the foot to be operated on separately secured, and the growths completely removed with sharp scissors or with a bistoury and forceps. When bleeding has subsided the wound is covered with a mixture of equal parts of iodoform, tannin, and powdered boric acid, and an interdigital dressing is applied. The dressing is removed after five to ten days, according to circumstances. If the cicatrix shows signs of exuberant growth it is dusted with powdered burnt alum, and the parts are treated as an open wound. When the growths are covered with horn and no longer painful it is not desirable to interfere with them.

CANKER.

Canker—i.e., chronic suppurative inflammation of the podophyllous or velvety tissue—is accompanied by hypertrophy of the papillæ and progressive separation of the horn of the sole. It is much rarer in the ox than in the horse, although it occasionally occurs.

Prolonged retention in dirty stables, where the bedding is mixed with manure and continually moistened with urine, is the principal cause of the disease. Individual predisposition and the action of some specific organism may also have some influence.

Canker in oxen, like the same disease in horses, is recognised by softening and separation of the horn of the sole, and by progressive extension of the process towards neighbouring parts. The usual course consists in invasion of the podophyllous tissue, separation of

the wall and of the heels, and pathological hypertrophy of the hornforming tissues, producing condylomata.

The new growths do not attain the same dimensions as in the horse, but, on the other hand, the disease very frequently takes a progressive course, involving the whole of the claw. A trifling accidental injury may be followed by infection of the subungual tissues, and thus become the point of origin for canker.

Canker may attack only one claw; on the other hand, it may extend to both claws of one foot, or to the claws of more than one foot in the same animal.

Diagnosis. Diagnosis is easy. The separation of the horn, the presence of a caseous, greyish-yellow and offensive discharge between the separated parts and the horn-secreting tissues, the appearance of the exposed living tissues, etc., leave no room for doubt.

Prognosis. The prognosis is grave; for, as in the horse, the disease is obstinate.

Treatment consists in scrupulously removing all separated horn, so as fully to expose the tissues attacked by the disease. The parts should then be thoroughly disinfected with a liquid antiseptic, and a protective pressure dressing applied.

As a rule, cauterisation with nitric acid, followed by applications of tar or of mixtures of tannin and iodoform, iodoform and powdered burnt alum, etc., effect healing, without such free use of the knife as has been recommended in the horse during the last few years.

GREASE.

Grease in the ox seems only to have been described by Morot and Cadéac, and even in these cases the descriptions appear rather to apply to elephantiasis or fibrous thickening of the skin than to grease proper. The descriptions are not sufficiently clear, and the symptoms described differ too much from the classical type seen in the horse to convince us without further confirmation of the occurrence of the disease.

PANARITIUM FELON WHITLOW.

Any injury in the interdigital space or flexure of the pastern may, under unfavourable circumstances, be complicated by death of the skin, necrosis of the interdigital ligament, of the fibro-fatty cushion in the flexure of the pastern, and of the terminal portions of the tendons.

These lesions are sometimes regarded as panaritium. In reality, they correspond exactly to what, in the horse, are known as “cracked heels” and “quittor.” The primary injury becomes infected with organisms which rapidly cause death of the skin or the formation of a deep-seated abscess and necrosis of the invaded tissues.

Causation. Neglect of sanitary precautions and filthy stables constitute favouring conditions, the feet being continually soiled and irritated by the manure and urine. Animals reared on plains, and having broad, flat, widely-separated claws, are more predisposed than animals from mountainous regions, in which the interdigital ligament is stronger and the separation of the claws less marked. Any injury, abrasion, or cut may serve as a point of origin for such complications.

Panaritium may even occur as an enzootic with all the characters noted in isolated cases. In Germany it has received the name of “contagious foot disease.” These enzootic outbreaks of panaritium follow epizootics of foot-and-mouth disease, with lesions about the claws. Through the superficial aphthous lesions the parts become inoculated with bacteria, and the severity of the resulting injury is in some measure an indication of the virulence of the infecting organism.

Symptoms. The first important symptom consists in intense local pain, rapidly followed by marked lameness. The affected region soon becomes swollen; the coronary band appears congested; the skin of the interdigital space projects both in front and behind; the claws are separated, and all the lower portion of the limb appears congested and œdematous. The engorgement usually extends as high as the fetlock, and the parts are hard and extremely sensitive. The patient is feverish, loses appetite, and commences to waste. After five to ten days sloughing occurs at some point—if the ligament is affected, in the interdigital space; if the tendons, or the fibro-fatty cushions, the

slough appears in the flexure of the pastern. The dead tissue may separate and fall away, or remain in position macerated in pus. Separation is generally slow, requiring from twelve to fifteen days, and, unless precautions are taken, complications occur. If only the interdigital ligament or fibro-fatty cushion be necrotic, recovery may be hoped for; but, on the other hand, if the tendons, tendon sheaths, ligaments, or bones are affected, complications like suppurating synovitis, suppurating ostitis, arthritis, etc., supervene, with fatal results. Death may occur from purulent infection, unless the animal is slaughtered early.

The diagnosis is easy. The intensity of the lameness, separation of the claws, swelling of the pastern region, sensitiveness of the swollen parts, and absence of lesions in the ungual region sufficiently indicate the nature of the condition.

The prognosis is grave, for complications may result, in spite of proper treatment.

Treatment. Treatment consists, first of all, in thoroughly cleansing the affected limb and placing the animal on a very clean bed. The parts are next subjected to antiseptic baths containing carbolic acid, creolin, sulphate of zinc, or sulphate of copper. It is often more convenient, and quite as efficacious, to apply antiseptic poultices to the foot and pastern, and to allow them to remain for some days, being moistened several times daily with one of the solutions indicated. The effects are: rapid diminution of the pain, delimitation of the necrotic tissues is hastened, and the abscess is more readily opened.

Many practitioners recommend early intervention in the form of deep scarification in the interdigital space or pastern region. The local bleeding, and the drainage which takes place through the wounds so made, is said to hasten recovery or to prevent complications.

When the abscess has opened, and the dead tissue separated, the abscess cavity or wound should be regularly washed out with a disinfecting solution, to prevent complications, in case fragments of necrotic tissue have been retained. If, however, complications have occurred, no hesitation should be felt in freely incising the parts, and, if necessary, in removing one or both phalanges. When both joints of one foot are affected, and arthritis threatens to or has set in, there is

no object in treating the animal, and early slaughter is to be recommended.

In cases where the disease follows foot-and-mouth disease, and threatens to become enzootic, it can generally be prevented spreading by keeping the foot-and-mouth subjects on very clean beds, and frequently washing the feet with antiseptic solutions. Disinfection of the sheds is also very desirable.

FOOT ROT.

Foot rot is a disease of sheep, and, like canker, is confined to the claws.

Thanks to the progress of hygiene, it tends to become rarer, but is still seen in the enzootic form in some portions of England and Scotland, in the mountains of Vivarais, the Cévennes, and the Pyrenees.

It affects large numbers of animals at once, animals belonging to one flock or to neighbouring flocks in one locality, and when it invades a sheep farm, all the animals may successively be attacked at intervals, according to the local conditions.

Symptoms. The disease develops rather insidiously, and the patients always retain an excellent appetite. It begins with lameness, which is at first slight, later becomes accentuated, and in the last periods is very intense. On examination, the coronet and lower part of the limb as high as the fetlock are found to be swollen. Palpation reveals exaggerated sensibility, and on direct examination, a fœtid discharge is discovered in the interdigital space. This discharge, which is peculiar to the onset of the disease, only continues for a week or two, and is succeeded by a caseous exudate which is always offensive, which moistens and macerates the horn, the skin, the tissues in the interdigital space, and the region of the heels. From the 20th to the 30th day after onset the claw separates above in the interdigital space. The separation extends towards the heel, then to the toe, exposing ulceration of the subjacent podophyllous tissue.

From this time the patients experience very severe pain, and, as in other diseases of the feet, remain lying for long periods. Movement becomes extremely painful, and the animals frequently walk on the

knees. The subungual lesions become aggravated, separation of the claw extends, necrosis of the podophyllous tissue and of subjacent tissue becomes more extensive, and the inter-phalangeal ligaments and the extensor or flexor tendons become involved. Finally, the claws are lost, and synovitis and arthritis are added to the complications already existing.

In an infected locality the development is always the same. The animals lose flesh, become anæmic, and, unless vigorously treated, soon die. The ordinary duration of the disease is from five to eight months, sometimes more. If, however, patients are isolated and well treated they recover.

Causation. The specific cause of foot rot still remains to be discovered, although everything points to the conclusion that it consists in an organism capable of cultivation in manure, litter, etc., for foot rot is transmissible by cohabitation, by mediate contagion through infected pasture, by direct contact and by inoculation.

The chief favouring influences are bad drainage, filthy condition of the folds, and herding in marshy localities.

Diagnosis. The condition can scarcely be mistaken, for the sheep suffers from no other disease resembling it, excepting, perhaps, footand-mouth disease.

Prognosis. The prognosis is grave, for the disease usually assumes a chronic course, affects entire flocks, and the patients require individual attention.

Treatment. The primary essential to success in treatment consists in separating and isolating the diseased animals in a scrupulously clean place and providing a very dry bed.

In the early stages the disease may be checked by astringent and antiseptic foot baths. It is then sufficient to construct a foot-bath at the entrance to the fold, containing either milk of lime, 4 per cent. sulphate of iron, copper sulphate, creolin, etc. Through this the sheep are passed two or three times a week. These precautions rarely suffice when the feet are already extensively diseased; and when the horn is separated to any considerable extent, surgical treatment is indispensable. All loose portions of horn should be removed and antiseptic applications made to the parts.

When a large number of sheep are affected the treatment is very prolonged, but it is absolutely indispensable, and the numerous dressings required necessarily complicate the treatment. It would be valuable to experiment with small leggings, which would retain the dressings in position, and, at the same time, shelter the claws from the action of the litter, while favouring the prolonged action of the antiseptic.

When the lesions are not extensive, a daily dressing is sufficient.

Among the materials most strongly recommended are antiseptic and astringent ointments containing carbolic acid, iodoform, or camphor. Vaseline with 5 per cent. of iodine is very serviceable, and much to be preferred to applications like copper sulphate, iron sulphate, etc. Its greatest drawback is its expense.

CHAPTER III.

DISEASES OF THE SYNOVIAL MEMBRANES AND OF THE ARTICULATIONS.

I.—SYNOVIAL MEMBRANES AND ARTICULATIONS.

SYNOVITIS.

Inflammation of the synovial membranes, or synovitis, may affect the synovial sacs either of the joints or of the tendon sheaths. It may be acute or chronic and occur either idiopathically or follow the infliction of an injury. Its two chief forms are simple, or “closed,” synovitis and suppurative, or “open,” synovitis, the essential distinction between which is that in the latter microorganisms are present, whilst in simple synovitis they are absent. In all cases the disease is characterised by distension of the sac affected.

Synovitis produced by a wound communicating with the outer air may be complicated by suppuration, and if the synovial membrane of a joint be involved the primary synovitis is almost always followed by traumatic arthritis.

The commonest forms of chronic simple synovitis are:—

INFLAMMATION OF THE PATELLAR SYNOVIAL CAPSULE.

Inflammation of the synovial membrane of the femoro-patellar joint is most commonly seen in working oxen as a consequence of strains during draught. It is also found in young animals which have injured the synovial capsule through falls, slips, or over-extension of the limb.

Symptoms. Development is slow and progressive, and injury may not be discovered until the lameness which follows has become fairly

marked. This lesion is characterised by swelling in the region of the stifle. On palpation, fluctuation may readily be noted both on the outer and inner surfaces of the joint. The exudate is sometimes so abundant and distension so great that the straight ligaments, the neighbouring bony prominences, and the ends of the tendons are buried in the liquid swelling.

Lameness, which is at first marked, often diminishes with exercise. The length of the step is lessened.

Diagnosis. The diagnosis presents no difficulty, but the lesions must be distinguished from those due to tuberculosis in this region, rheumatic arthritis, and the specific arthritis seen in milch cows.

The prognosis is grave, for the disease renders animals useless for work.

Treatment. Rest, cold moist applications, and massage constitute the best treatment in the early stages. Should swelling persist, one may afterwards apply a smart blister or even tap the joint aseptically, drawing off the fluid and then applying the actual cautery. Irritant injections must be avoided.

Bog Spavin in the Ox.

Bog spavin is frequent in working oxen and in oxen from three to five years old. It is due to strain in draught or to strain produced in rearing up at the moment of covering. Old bulls, heavy of body, and stiff in their limbs are predisposed to it.

Symptoms. The symptoms usually develop gradually and without lameness, but sometimes declare themselves more rapidly with lameness, accompanied by marked sensitiveness on palpation. At first the hock shows a generalised doughy swelling, soon followed by dilatation of the articular synovial sac. Somewhat later four different swellings appear—two in front, separated by the tendons of the common extensor and flexor metatarsi, and two at the back, extending inside and outside to the flexure of the hock.

Diagnosis. The only precaution required in diagnosis is to avoid confusion with articular rheumatism.

DISTENSION OF THE SYNOVIAL CAPSULE OF THE HOCK JOINT.

Prognosis. The prognosis is rather grave in the case of working oxen, and even of bulls; often slaughter is preferable to treatment.

Treatment differs in no respect from that of distension of the stifle joint. In young bulls aseptic puncture and drainage of the joint, followed by the application of the actual cautery, probably give the best results.

DISTENSION OF TENDON SHEATHS IN THE HOCK REGION.

Like the preceding, this condition is rarely seen except in bulls and working oxen. It is characterised by dilatation of the upper portion of the tarsal sheath, one swelling appearing on the outer side, the other on the inner.

The differential diagnosis is based on the position of these synovial sacs, which are quite close to the insertion of the tendoAchillis, and on the absence of any swelling in front of the joint.

Treatment is identical with that indicated in the last condition.

Massage and cold water applications should be employed at first, to be followed by aseptic puncture and withdrawal of fluid, supplemented if necessary by firing in points.

DISTENSION OF THE SYNOVIAL CAPSULE OF THE KNEE JOINT.

This is one of the rarest conditions now under consideration, because the synovial membranes of the knee joint are everywhere strongly supported by very powerful ligaments. The synovial capsules of the carpo-metacarpal and inter-carpal joints are incapable of forming sacs of any size. On the other hand, the radiocarpal may become moderately prominent in front, especially towards the outside above the superior carpal ligament. When weight is placed on the limb, the excess of synovia is expelled from the joint cavity towards this little sac, which then becomes greatly distended. If, on the other hand, the knee is bent, the sac shrinks or disappears.

Treatment. Treatment is restricted to the application of a blister or to firing in points.

F��. 17.—Front view of the ox’s hock, showing the relations of the tendons and synovial sacs.

DISTENSION OF THE SYNOVIAL CAPSULE OF THE FETLOCK JOINT.

F��. 18.—Side view of the ox’s hock. The synovial sac of the true hock joint has been injected to show the relations of the sacs.

The synovial capsule of the fetlock joint in the ox is strongly supported in front and at the sides, but may protrude under the anterior ligament, producing a swelling behind the metacarpus under the five branches of division of the suspensory ligament and slightly below the sesamoid bones. These distensions, like bursal swellings, are commoner in hind limbs and in old working oxen. Their development is always followed in time by a certain degree of knuckling over. At first the metacarpus and phalanges come to form a straight line, but later the fetlock joint itself is thrust forward. The diagnosis necessitates careful manual examination of the region of the fetlock joint.

The prognosis is somewhat grave, for the disease sooner or later necessitates the destruction of certain animals.

Treatment is practically identical with that used in all such conditions: friction with camphorated alcohol, cold affusions and massage in the earlier stages, followed if needful by blisters or firing in points.

DISTENSION OF TENDON SHEATHS.

Distension of the synovial capsule which surrounds the superior suspensory ligament, like distension of the articular capsule of the fetlock, occurs in working animals, and most commonly affects the front limbs. It is indicated by two swellings, one situated on either side of and behind the branches of division of the suspensory ligament and in front of the flexor tendons. These two swellings extend higher than the articular swellings, which, however, they sometimes accompany. The surface of the fetlock is then swollen, doughy on pressure, and somewhat painful.

These enlargements may produce more or less marked lameness and cause knuckling.

The diagnosis is clear from local examination.

The prognosis is unfavourable, as the animals after a time become useless for work.

Treatment. The beginning of the disease may often be cured by baths of running water, combined with massage. At a later stage, local stimulants, blisters, or firing are necessary. The best treatment probably consists in puncturing the parts with antiseptic precautions, washing out the synovial cavity with an antiseptic, and immediately afterwards lightly firing the surface of the region in points.

DISTENSION OF TENDON SHEATHS IN THE REGION OF THE KNEE.

Any of the numerous tendon sheaths which facilitate the gliding of tendons in the neighbourhood of the knee may become inflamed and give rise to a chronic synovial swelling. The commonest of such swellings is due to distension of the sheath of the extensor metacarpi magnus, which appears as a vertical line in front of the knee, extending from the lower third of the forearm and slightly to the

outer side of the central line. This synovial enlargement arises in oxen working on broken roads, in clay or marshy soils, where the animals are liable to stick fast, and are often obliged to struggle vigorously in order to extricate themselves.

The diagnosis is based on the position and direction of the dilated synovial sheath.

Treatment is identical with that of other cases of chronic synovitis.

DISTENSION OF THE BURSAL SHEATH OF THE FLEXOR TENDONS.

This condition is rare. It is announced, as in the horse, by a dilatation of semi-conical form, the apex of which is situated opposite the lower margin of the carpal sheath, the base extending as high as the infero-posterior third of the radius.

The dilatation is more marked on the inner than on the outer side of the limb.

Distension of the synovial sheath of the common extensor of the digits in the fore limb and of the extensor of the external digit is still rarer than the preceding conditions.

TRAUMATIC SYNOVITIS “OPEN SYNOVITIS.”

When an injury in the neighbourhood of a joint penetrates deeply, it may implicate either the synovial sheath of a tendon or the synovial membrane of a joint. If the body inflicting the wound is aseptic, a condition which in accidental wounds is rare, the wound may have no grave consequences. Usually, however, the body producing the injury is infected, and the infection rapidly extends throughout the tendon sheath or synovial sac. In the first case, traumatic suppurating synovitis of a tendon sheath is the result; in the second, a suppurating articular synovitis arises, which soon becomes complicated with injury of the articular cartilages, ligaments, etc. (traumatic arthritis).

The primary lesion may only affect the periarticular region, not directly extending to the synovial membranes, and only after an

interval of some days may symptoms of suppurating synovitis or suppurating arthritis appear, in consequence of progressive invasion of the parts by specially virulent microbes.

TRAUMATIC TENDINOUS SYNOVITIS.

Suppurative inflammation of the synovial bursæ of tendons in consequence of wounds most commonly affects the sesamoid sheaths of the front or hind limbs; more rarely, the tendon sheaths of the hock or knee; and, exceptionally, the small synovial sheaths of the extensors of the metacarpus and phalanges, etc.

Such inflammation follows injuries with forks, harrow teeth, or any sharp foreign body. It is characterised by the existence of a fistula or wound, indicating the course taken by the body inflicting the injury, from which at first normal synovia escapes. Later, however, the discharge becomes turbid, and after the second day gives place to a clotted, serous, or purulent fluid.

A diffuse, œdematous, warm, painful swelling very rapidly develops around the injury. The animal is more or less feverish and lame. The swelling soon extends throughout the entire length of the infected synovial sheath. The patient loses appetite, and unless treatment is promptly undertaken, complications supervene which often necessitate slaughter. The prognosis is always grave.

Treatment. Continuous irrigation has long been recommended. It is worthy of trial, but in the majority of cases occurring in current practice it cannot be carried out.

Moussu prefers a form of treatment which he claims has always succeeded in horses and oxen—viz., irrigation of the parts, followed by injection of sublimate glycerine solution.

He first washes out the infected synovial cavity with boiled water cooled to 100° Fahr. A counter-opening may become necessary, and the washing should be continued until the escaping water appears perfectly clear. Immediately after each such irrigation he injects from 7 to 14 drams of glycerine containing 1 part in 1,000 of corrosive sublimate. He repeats this treatment daily.

By reason of its affinity for water and for the liquids in the tissues or suppurating cavities into which it is injected, the glycerine

penetrates in all directions, reaching the finest ramifications of the synovial sacs, a fact which explains its superiority over aqueous antiseptic solutions.

Suppuration is rapidly checked and repair becomes regular. The pain and lameness progressively diminish, and recovery may be complete.

It is advisable to assist this internal antiseptic treatment by external stimulants and by the use of a blister. Solutions of greater strength than 1 part of sublimate to 500 of glycerine are only required during the first few days of treatment and until suppuration diminishes. Later, they prove irritant, and interfere with healing.

TRAUMATIC ARTICULAR SYNOVITIS TRAUMATIC ARTHRITIS “OPEN ARTHRITIS.”

It has been described above how primary inflammation of the articular synovial membrane produced by a wound may rapidly develop into suppurating arthritis.

Symptoms. The pain is very marked at the moment when the accident occurs, but this pain, due to the mechanical injury inflicted, diminishes or completely disappears after some hours. Soon, however, synovial discharge sets in, announcing the onset of traumatic synovitis. At first limpid, it soon becomes turbid, then curdled, and finally grumous, purulent and greyish in colour.

Pain then returns, rapidly becomes intense, continuous and lancinating. It produces lameness, sometimes so severe that no weight whatever can be borne on the limb. A diffuse,