In-situ growth of CoP wrapped by carbon nanoarray-like architecture onto nitrogendoped Ti3C2 Pt-based catalyst for efficient methanol oxidation W. Zhan & L. Ma & M. Gan

https://ebookmass.com/product/in-situ-growth-ofcop-wrapped-by-carbon-nanoarray-like-architectureonto-nitrogen-doped-ti3c2-pt-based-catalyst-forefficient-methanol-oxidation-w-zhan-l-ma-m-gan/

Download more ebook from https://ebookmass.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Winterberries-like 3D network of N-doped porous carbon anchoring on N-doped carbon nanotubes for highly efficient platinum-based catalyst in methanol electrooxidation Tong Wang

https://ebookmass.com/product/winterberries-like-3d-network-of-ndoped-porous-carbon-anchoring-on-n-doped-carbon-nanotubes-forhighly-efficient-platinum-based-catalyst-in-methanolelectrooxidation-tong-wang/

Achieving uniform Pt deposition site by tuning the surface microenvironment of bamboo-like carbon nanotubes Meng Jin

https://ebookmass.com/product/achieving-uniform-pt-depositionsite-by-tuning-the-surface-microenvironment-of-bamboo-likecarbon-nanotubes-meng-jin/

Elsevier Weekblad - Week 26 - 2022 Gebruiker

https://ebookmass.com/product/elsevier-weekbladweek-26-2022-gebruiker/

Calculate with Confidence, 8e (Oct 26, 2021)_(0323696953)_(Elsevier) 8th Edition Morris Rn Bsn Ma Lnc

https://ebookmass.com/product/calculate-withconfidence-8e-oct-26-2021_0323696953_elsevier-8th-edition-morrisrn-bsn-ma-lnc/

Structure of the in situ produced polyethylene based composites modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes: In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and differential scanning calorimetry study Coll.

https://ebookmass.com/product/structure-of-the-in-situ-producedpolyethylene-based-composites-modified-with-multi-walled-carbonnanotubes-in-situ-synchrotron-x-ray-diffraction-and-differentialscanning-calorimetry-study-coll/

Pt-based (Zn, Cu) nanodendrites with enhanced catalytic efficiency and durability toward methanol electrooxidation via trace Ir-doping engineering Kai Peng & Weiqi Zhang & Narayanamoorthy Bhuvanendran & Qiang Ma & Qian Xu & Lei Xing & Lindiwe Khotseng & Huaneng Su https://ebookmass.com/product/pt-based-zn-cu-nanodendrites-withenhanced-catalytic-efficiency-and-durability-toward-methanolelectro-oxidation-via-trace-ir-doping-engineering-kai-peng-weiqizhang-narayanamoorthy-bhuvanendra/

GaN transistors for efficient power conversion Third Edition De Rooij

https://ebookmass.com/product/gan-transistors-for-efficientpower-conversion-third-edition-de-rooij/

Fabrication of 3D interconnected porous MXene-based PtNPs as highly efficient electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation Qiang Zhang & Yuxuan Li & Ting Chen & Luyan Li & Shuhua Shi & Cui Jin & Bo Yang & Shifeng Hou

https://ebookmass.com/product/fabrication-of-3d-interconnectedporous-mxene-based-ptnps-as-highly-efficient-electrocatalystsfor-methanol-oxidation-qiang-zhang-yuxuan-li-ting-chen-luyan-lishuhua-shi-cui-jin-bo-yang/

Jock Seeks Geek: The Holidates Series Book #26 Jill Brashear

https://ebookmass.com/product/jock-seeks-geek-the-holidatesseries-book-26-jill-brashear/

MaterialsTodayChemistry26(2022)101041

Contentslistsavailableat ScienceDirect

journalhomepage: www.journals.elsevier.com/ma terials-today-chemistry/

In-situgrowthofCoPwrappedbycarbonnanoarray-likearchitecture ontonitrogen-dopedTi3C2 Pt-basedcatalystforefficientmethanol oxidation

W.Zhan,L.Ma*,M.Gan**

CollegeofChemistry & ChemicalEngineering,ChongqingUniversity,Chongqing400044,PRChina

articleinfo

Articlehistory:

Received21April2022

Receivedinrevisedform 9June2022

Accepted10June2022 Availableonlinexxx

Keywords: MXene 3Darchitecture MOFs Nanomaterialcatalyst abstract

1.Introduction

Herein,wereportanefficientbottom-upapproachtoconstructthecarbonencapsulatedCoPnanoarraylikearchitecturesontothenitrogen-dopedTi3C2 MXenePt-basedcatalyst(Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2)by employingmetal-organicframeworks(MOFs)asthesacrificialtemplate.Benefitingfromthecatalytic effectformetalsintoMOFsandsynergisticeffectofTi3C2 substrate,homogenousnanotubesnanoarraylikestructureisobtainedonTi3C2 nanosheet.Theuniqueheteroatom-doped3Dconnectedstructure endowsthecatalystwithdistinctstructuralmerits,suchasthecarbonandnitrogen-enrichedstructures, largespecificsurfaceareasandexcellentconductivity,leadingtothehighdispersionofultrafinemetallic Ptandefficientelectronic/masstransfer,contributingtomoreexposedactivesitesofPtsurface.The fabricatedCoPanddopednitrogenespeciallyforthoselatticenitrogenderivedfromthepristineMOFs canpresentexceptionalco-catalyticeffect,resultinginobtainingstronganti-COpoisoningcapacityfor catalyst.Therefore,theultrahighcatalyticactivityofperPtactivesiteformethanoloxidation reactioncanbepreserved.Besides,owingtothestrongstabilityofcarrier,thecatalystdeliversareliable long-termstabilityduringthetest.Thisworkgivesnewidealforthedesignofnovelcost-effective3D Ti3C2-basednanomaterialcatalystwithexcellentcatalyticactivityformethanoloxidation. © 2022ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Facingwitheversurgingdemandforcleanandefficientenergy, moreandmoreattentionisbeingpaidtovariousrenewableenergy devicelikefuelcells[1 3],energystoragebattery[4,5].Among them,gettingbenefitfromitshigh-powerdensityandfacilityfor storage,directmethanolfuelcellsisarisingasanappealingenergy device.Nevertheless,rationallydesigninganodecatalystisbelieved tobethekeyfactorforitspromisingelectrochemicalperformance. Inthepastdecades,platinum(Pt)wasmostutilizedcatalystfor anodemethanoloxidationreaction(MOR)attributingtoitsexcellentcatalyticalactivity[6,7].However,consideringtheslowkinetic processtowardMORandseriouspoisoningcausedbytheintermediatesCOforPtnanoparticles(NPs), findingawaytospeed upcatalyticreactionforPtwhiledecreasingitsamountofuseis obviouslyprofitable.

* Correspondingauthor.

** Correspondingauthor. E-mailaddresses: mlsys607@126.com (L.Ma), mlsys404@126.com (M.Gan).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.101041 2468-5194/© 2022ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Profitedbyextensiveefforts,somestrategiesareproposedto constructstate-of-artPt-basedcatalyst.Introducingforeignmetalto fabricatePtalloyisthemostcommonwayforthisaim[8 10]. However,theirhighpricesandcomplexpreparationarefarfrom large-scaleapplicationlevel.Recentyears,co-catalystlikemetal carbides[11 13],nitrides[14 16],phosphides[17 19]havestimulatedintensifiedinterestingduetotheirexcellentco-catalyticeffectforMOR.Withinthesecompounds,metalphosphideshave madeagreatprogressforimprovedmethanoloxidationperformance.Forexample,Changetal.havedevelopedacarbonblack supportnickelphosphidePt-based(Pt Ni2P/C)catalyst.Benefiting fromtheexcellentco-catalyticeffectofnickelphosphidebroughtby strongelectronicinteractionbetweennickelphosphideandPtand itsabilitytodissociatewateratlowerpotential,thecatalystdisplays stronganti-COpoisoningcapacity.Andthebestactivitywasobtainedwithaloadingof30%Ni2P,whichwas fivetimeshigherthan thatofthecommercialPt/Ccatalyst[20].Unfortunately,thechallengeremainstoexerttheexcellentandstableco-catalyticeffectfor thesemetalphosphides.

ChoosinganidealcarrierforPtdepositingisanotherissueinthe caseofobtaininghighlydispersionofPtNPswithmoreaccessible

exposedactivesitesremainedarestillchallenged.Inthepast, carbon-basedsubstrateslikecommercialcarbon,carbonnanotube, andgraphitewereexploitedincaseoftheirhighconductivityand stabilityaswellastheirabundantanchorsitesforPtloading [21 23].Foraninstance,Wangetal.haveconstructedan3D graphene carbonnanotubecompositefordepositingPt.Givingthe credittoitsperfectelectricalconductivityandporousstructure, highlydispersionofPtRuparticlesontocarrierwereobtainedand theresultingcatalystthusshowedremarkablecatalyticactivity[24]. Despitesuchappealingpropertiesofthesecarbonmaterials,their stabilityandelectrochemicalactivityforlong-termtestingarenot satisfiedduetotheirsevereelectrochemicalcorrosion.Thus, corrosion-resistantmaterialscouldbefascinatingalternativesforPt loading[25].Thesedays,TheMXenefamily,especiallyforthe Ti3C2Tx obtainedbyselectivelyexfoliationfromMAXphase,have madesignificantachievementinthe fieldsofcatalysisonaccountof theexcellentstabilityandconductivityaswellasitsuniquesurface properties[26,27].However,thesevereoxidationeffectofTi3C2 and itsabundantstructuraldefectsgeneratedduringthepreparationof Ti3C2 hybridcouldgreatlyaffectitselectricalconductivity.Inaddition,theporouscarbonsites,especiallyforthoseheteroatom-doped defectivesites,arebelievedtobethestableanchorsitesforPt deposition.Therefore,thelowerspecificsurfaceareasanditssevere oxidationdegreeleadlessanchorsitestobepreserved[28].Hence, improvingitselectricalpropertiesaccompaniedwithabundant stableanchorsitesremainedcouldbevaluableforoptimizingthe MORperformance.

Onthebasicofaboveconsideration,forthe firsttime,weproposetheCoPresidesinmesoporouscarbonnanotubearray-like structuresupportedbythenitrogen-Ti3C2 MXenePt-basedcatalyst(Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2)throughinsuitgrowthofCoZn-ZIF onTi3C2Tx nanosheetcombinedwiththecalcinationandphosphatingprocedures.Andsubsequentlybeingtreatedwiththe NaBH4 reductionprocessforobtainingtheresultingcatalyst. BenefitfromtheopensurfaceofTi3C2 andthecatalyticeffectof reducedmetalsathightemperature,onlytheresultingcatalyst Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 isendowedwiththehomogenouscarbonnanotubearray-likestructure.Thosecarbonandnitrogenenrichedstructuresensuretheenhancedoverallconductivityand contributetohighlydispersionofPtNPs.Besides,theCoZn-ZIF deliversabundantnitrogensources,renderingtheformationof dopedlatticenitrogenintotheTi3C2 duringtheannealingtreatment.Thislatticenitrogencouldsufficientlyalterthesurface propertiesofTi3C2 suchasthespecificsurfaceareas,itselectronic structure,resultinginexcellentco-catalyticeffectcombinedwith thefabricatedCoP.Moreimportant,thestronganti-electrochemical corrosionofthecarrierprovidesthebasisforitshighcatalytic stability.Thus,thecatalystisentitledwithsuperhighMORactivity andexcellentstability.

2.Experimental

2.1.Materials

Allchemicalagentswereanalyticgrade.Ti3AlC2 (400mesh,purity:98%)wasobtainedfrom11TechnologyColtd.Cobaltnitrate hexahydrate(Co(NO3)2 6H2O),zincnitratehexahydrate(Zn(NO3)2 6H2O),methanol,hydrochloricacid,trisodiumcitratedehydrate,2Methylimidazole,andsodiumborohydride(NaBH4)wereallpurchasedfromChuandongChemicalReagentCompany(Chengdu, China).Lithium fluorideandNafionsolutionweregainedfromthe AladdinColtd.HighpurityN2 ( 99.99%)wasgainedfrom ChongqingRuixingCoLtd.

2.2.SynthesisofCoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2Tx

AsforthefabricationofTi3C2Tx,itwentthroughtheprevious reportedprocedure[29],whichcanbesummarizedasfollows: first, about0.5gTi3AlC2 MAXphasewasdissolvedintothe9Mhydrochloricacid(10mL)mixturecontaining0.5gdissolvedLithium fluoridewithconstantmagneticstirringfor24hat35 C.Afterward,theabovemixturewassubjectedtothecentrifugalandultrasoundtreatmentforobtainingtheTi3C2Tx MXene.

TopreparetheCoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2Tx composite,50mgTi3C2Tx was shiftedtothe50mlmethanolsolutioncontainingdissolved1g2Methylglyoxaline.Then0.26gCo(NO3)2$6H2O(about1mmol)and 0.26gZn(NO3)2 6H2O(about1mmol)weredissolvedinto6ml methanolsolution.Afterward,theabovemetalsaltssolutionwas dropwiseinjectedintotheTi3C2 mixturewithmagneticstirringfor 3h.Followedbythecentrifugaltreatment(10000p.m.for10min) andbeingdriedat60 Covernightinvacuumdryingoven,The CoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2Tx compositewasfabricated.Forothercomposites, theyweresynthesizedunderthesameconditionandnamedasZIF67/Ti3C2 andCoZn-ZIF.

2.3.SynthesisofCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2

About200mgCoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2 compositewasputintoaporcelainboatwithcarbonizationtreatmentat900 C(2 C/min)for2h. Thenanotubesnanoarray-likestructurecouldbeformedatthis processandthenitrogensourcewaspartlydopedintothecrystal structureofTi3C2 fortheformationofnitrogen-dopedTi3C2.The obtainedsamplewaslabeledasCo@CNTNA/N Ti3C2.Asforthe phosphatingprocess,about30mgCo@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 and 800mgNaH2PO2 weretransferredintotwoseparatelyboatswith phosphatingtreatmentunder400 C(2 C/min)for2h.CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2 wasnamedafterthecompositeandothersamples wereacquiredunderthesamecondition.Theywerelabeledas CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 andCoP@NC.

2.4.SynthesisofPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2

PtNPsdepositedontoCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 carrierwasobtainedbysodiumborohydridereductionprocedure[30].Primarily, 20mgCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 wasshiftedintodeionizedwater (20mL)keepingstirringfor0.5h.Afterward,dissolvingtrisodium citratedehydrate(24.5mg)intoDIwater(5mL)withultrasound for0.5h.Meanwhile,sodiumborohydride(2.5mg)wasdispersed into4.3mLH2Oforattainingtheaqueoussolution.Then, 0.525mLH2PtCl6-EG(0.0488M)solutionwascarefullydropped intothetrisodiumcitratedehydratesolutionwith0.5hsonication togaintheslurry.Subsequently,beingaddedwithborohydride aqueoussolutionintoaboveslurry,PtNPsweredepositedon CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 composite.Finally,thecatalystwascollected withwashinganddriedovernightat60 C.Withregardtoothers, theywerefabricatedthroughthesameprocedure.

2.5.Electrochemicalcharacterizations

ElectrochemicalmeasurementwasperformedusingaCHI760E electrochemicalstationequippedwiththree-electrodesystem:a platinumwirewasactedascounterelectrode,aglassycarbon electrode(4mmindiameter)servedastheworkingelectrodeand saturatedcalomelelectrodewasreferenceelectrode[31].Allthe electrochemicaltestswereinregardtosaturatedcalomelelectrode.

Forobtainingcatalystinks:2mgsamplewasimmersedintoa mixturecontaining475 mLethanol,475 mLwater,and50 mLnafion

W.Zhan,L.MaandM.Gan

solution(5wt%)withsonicationfor0.5h.Afterthat,ink(5 mL)was drippedontoglassycarbonelectrodesurface.Beforeinitiatingthe procedure,solutionsweresaturatedwithN2 forabout20min.

Forthecyclicvoltammetrymeasurement,itperformedinthe N2-saturated0.5MH2SO4 þ 1.0MCH3OHsolutionwith50mV/s. Thechronoamperometryexperimentwasconductedwiththepotentialat0.6Vfor3600s.TheaveragesizeofPtNPsontosubstrate wasobtainedbyaveragingtheparticlesizeof100PtNPs.Andmore specificexperimentinformationcanbeseeninsupportingInformation.Allexperimentswereproceededattheroomtemperature.

2.6.Physicalcharacterizations

X-raydiffractionwasconductedontheRINT2000apparatus (Rigaku)andthemicroscopicmorphologyofcatalystswasinvestigatedusingthescanningelectronmicroscopy(JEOLJSM-7001). Thetransmissionelectronmicroscopy(TEM)imageswereperformedonafield-emissiontransmissionelectronmicroscope(FEI TalosF200S).Thechemicalstatesandcompositionforcatalysts weremeasuredbytheX-rayphotoelectronspectroscopy(JPS-9010 TR(JEOL)).Thespecificsurfaceareasofcompositeswereexamined bythelowtemperaturenitrogenadsorption/desorptionexperiment.ICP-OES(iCAP7200)measurementwasexploitedtodetect themassloadingofPtforcatalysts.TheRamancharacterization wascarriedoutusingLabRamHR800spectrometer,andtheelectricalconductivityforallcatalystswastestedusingFour-probe meter(ST-2722).

3.Resultsanddiscussion

3.1.Characterizationofelectrocatalysts

Thesynthesisprocessisillustratedasfollows(Fig.1a): first,the CoZn-ZIFwasin-situgrewontotheTi3C2Tx MXenenanosheet throughthecoordinationeffectbetweenthesurfacetermination groups(-OH, O)andorganicligands ‘2-Methylimidazole’.Subsequentlybeingtreatedwithannealingandphosphidingprocedures, themesoporouscarbonencapsulatedCoPnanoarray-likeunique structuresupportedbyN-dopedTi3C2 MXenenanosheet(CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2)wasfabricated.FollowedbydepositingwithPtparticlesthroughtheNaBH4 reductionprocedure,theresultingcatalystwasthereforeobtained.

Theirrepresentativemorphologiesareshownin Fig.1.Itcanbe observedthattheTi3AlC2 MAXphase(Fig.1b)presentsthebulkand stackstructure.WhiletheTi3C2Tx (Fig.1c)obtainedfrometching revealsits2Dlayerarchitecturerangingfromhundredsofnanometerstoseveralmicrons,demonstratingthesuccessofetching procedure.ThiscanbefurthersupportedbytheresultsofRaman measurement(Fig.S1),wheretheoriginalcharacterizationpeaks(I, II,III,IV)ofTi3AlC2 hasbeendemolishedaftertheexfoliationprocess[32].AfterbeingcoatedwiththeMOFs,thenanosheetis completelycoveredbyMOFscrystalsforCoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2Tx (Fig.1d) andZIF-67/Ti3C2Tx composite(Fig.1e).Whentheaboveprecursors aresubsequentlytreatedwithannealing,theirintrinsic3Dhybrid structurehasbeenchanged.Asisdepictedin Fig.1f,forCo@CNT NA/N Ti3C2 composite,itsformerMOFspolyhedralcrystalshave beenvanishedandconvertedtothecarbonnanotubenano-array likearchitecture.Anditiscleartoseetheexistenceoftubular structuresandtheNPs(Fig.1g),verifyingthesuccessfulderivation ofcarbonnanotubes.Fouriertransforminfrared(FTIR)characterization(Fig.S2)showstheadventofterminalgroups(-OH, F, O) generatedduringtheetchingprocess,disclosingthesuccessful synthesisofTi3C2Tx.However,thedecreaseoftransmittanceis observedforCo@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 comparedwiththatofTi3C2Tx duetothedecompositionofgroupsathightemperature.Therefore,

theT3C2 isusedtonameafterthecompositesaftercalcination treatmentinsteadofusingword ‘T3C2Tx’.Additionally,characteristicpeakofTi Oatlowerposition(near500cm 1)isalsotraced, ascribingtotheinevitablyoxidizedduringthecalcinationprocess. Moreover,fordeterminingtheexistenceoflatticeN,FTIRofthese twocompositesarealsoperformed(Fig.S3).Asisshownin Fig.S3, comparingwiththeTi3C2Tx,twoFTIRpeaksareobservedinthe Co@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 sample.Thepeaksat1410and1360cm 1 are ascribedtothevibrationsoftheTi Nbond,demonstratingthe successfulformationforlatticeN[33,34].Itisworthnotingthat, duringthecalcinationprocess,nitrogencouldbeintroducedby partlydecomposingCoZn-ZIFitself,leadingtodopingofnitrogen intothebulkstructureoftheTi3C2 fortheformationofTi Nbond, whichcouldsufficientlyalteritselectrochemicalproperty.Notably, forCo@NC/N Ti3C2,onlyfewnanotubesareobserved(Fig.S4)and mostofreducedCoparticlesjustattachedontoMXenenanosheet surface.TheeffectofZnintoMOFstopologystructureaccountsfor thisdiversity,wheretheZnevaporatesathightemperatures(above 800 C)mayacceleratethecatalyticprocessofthereducedCoand facilitatestheradialgrowthalongthenanosheetforcarbonlayers [35].Therefore,promotingthegrowthofthecarbonnanotubes. Moreover,asforCo@NCcomposite,whichderivesfromCoZn-ZIF (Fig.S5),onlyfewnanotubesareemerged.Thismaybeascribed tothefunctionofTi3C2 MXenenanosheet,whichprovidesvast roomsforthegrowthoflargenumberofCoZn-ZIFcrystalsand moreCointhenodescouldgetaccesstoeachotherduringthe calcinationprocess.Onthisaccount,strengtheningthecatalytic formationofcarbonnanotubes.Afterbeingsubjectedtothe phosphidingprocedure,theCoparticlesareconvertedtotheCoP forCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (Fig.1h)withoutsignificantdamageto thenanostructureevenunderthetoughtreatmentofphosphiding. AsfortheresultingcatalystPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (Fig.1i),the robustcarbonnanotubesarealsopreservedafterthedeposition process.

Forinvestigatingthepropertiesofporousstructureforcatalysts, theBETcharacterizationwasutilized.Fromthe Fig.S6a,wecansee thattheCo@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 carrierhasaclearadsorptionhysteresisloop,indicatingthepresenceofmesopores.Whilenosignificant hysteresisloopisobservedforCoP@NC/N Ti3C2 composite, implyingitsmicropore-dominantcharacteristics.TheBETsurface areasforCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 andCoP@NC/N Ti3C2 aremeasured tobe220.5cm3 g 1 and159.3cm3 g 1,respectively.Theincreased specificsurfaceareaforCoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 ismainlycausedby theevaporationofZnathightemperature(above800 C),which leadstotheformationofmoreporouscarbonnanotubes.Additionally,presentedin Fig.S6b,theporesizeforCoP@CNTNA/ N Ti3C2 isconcentratedat6nmandforCoP@NC/Ti3C2 iscloseto 2nm.ThankstothesynergisticeffectofZn,largesurfaceareasand moremesoporousstructurescanbeformed,triggeringthehighly dispersionofPtNPsandfastermasstransfer.

Characterizationofstructuralcompositionforthoseprecursors wascarriedoutbyX-raydiffraction(Fig.2).

ForTi3AlC2 MAXphase(Fig.2a),remarkablediffractionpeaks belongingtotheTi3AlC2 areobserved[36].Thesignificantphase separationoccurredforTi3C2Tx aftertheetchingtreatmentcompared withthatofTi3AlC2 [37],demonstratingthepossiblefabricationof Ti3C2 nanosheet.AfterbeingcoatedwiththeMOFscrystals(Fig.2b), manysharppeaksatlowdiffractionangles,referringtotheexclusive peaksofCoZn-ZIF[38],havebeenfound,proofingthesuccessful growthofMOFscrystals.Notably,someadditionalpeaksat39.20 , 42.34 ,70.43 ,and73.65 areshown,assigningtothe(040),(221), (332),(004)planesofTiO2,respectively.Andthepeakat60.84 is indexedwiththe(710)planeofTiO2 (PDF#46 1238),attributingto theeasilyoxidizednatureofTi3C2 [39].FortheCo@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 compositewhichobtainedbythecalcinationofZIF-67/Ti3C2Tx,the

W.Zhan,L.MaandM.Gan

Fig.1. Fabricationproceduresofthecatalyst(a),SEMimagesofTi3AlC2 MAXphase(b),exfoliatedTi3C2Tx nanosheet(c),CoZn-ZIF/Ti3C2Tx (d),ZIF-67/Ti3C2Tx (e),Co@CNTNA/ N Ti3C2 composite(f)anditslocalenlargedimages(g),CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (h)andPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalyst(i).CNT,carbonnanotube;SEM,scanningelectron microscopy.

peaksat44.22 ,51.52 ,and75.85 arematchedwiththe(111),(200), and(220)planesofCo,respectively.Accompaniedwiththephosphidesprocess,allcompositesdisclosethedistinctdiffractionpeaksof CoPandthepeaksat31.6 ,36.31 ,48.13 ,and56.36 arecorrespondingtothe(011),(111),(211),and(212)planesofCoP,demonstratingthevictorioussynthesisofthephosphides.Andsome additionalpeaksareobserved,wherethepeaksat42.57 and42.65 areattributedtothe(202)and(121)planesofTi2O3 (PDF#43 1033) andTiO2,individually.SubsequentlybeingtreatedwithNaBH4 reductionoperation,itcanbeseentheadventofthecharacterization peaksofPtforallcatalysts.Andthepeakslocatedatthe39.76 ,46.24 , 67.45 ,and81.29 areindexedwithits(111),(200),(220),and(311) planes,whichindicatethe fineloadingofPtNPsontothesubstrates. Additionally,manyextracrystallineplanesarefound,wherethepeaks locatedat27.68 iscorrespondingto(104)planeofC(PDF#22 1069) andtheoneat54.20 isassignedtothe(320)planeofTiO2 for Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 andPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2.

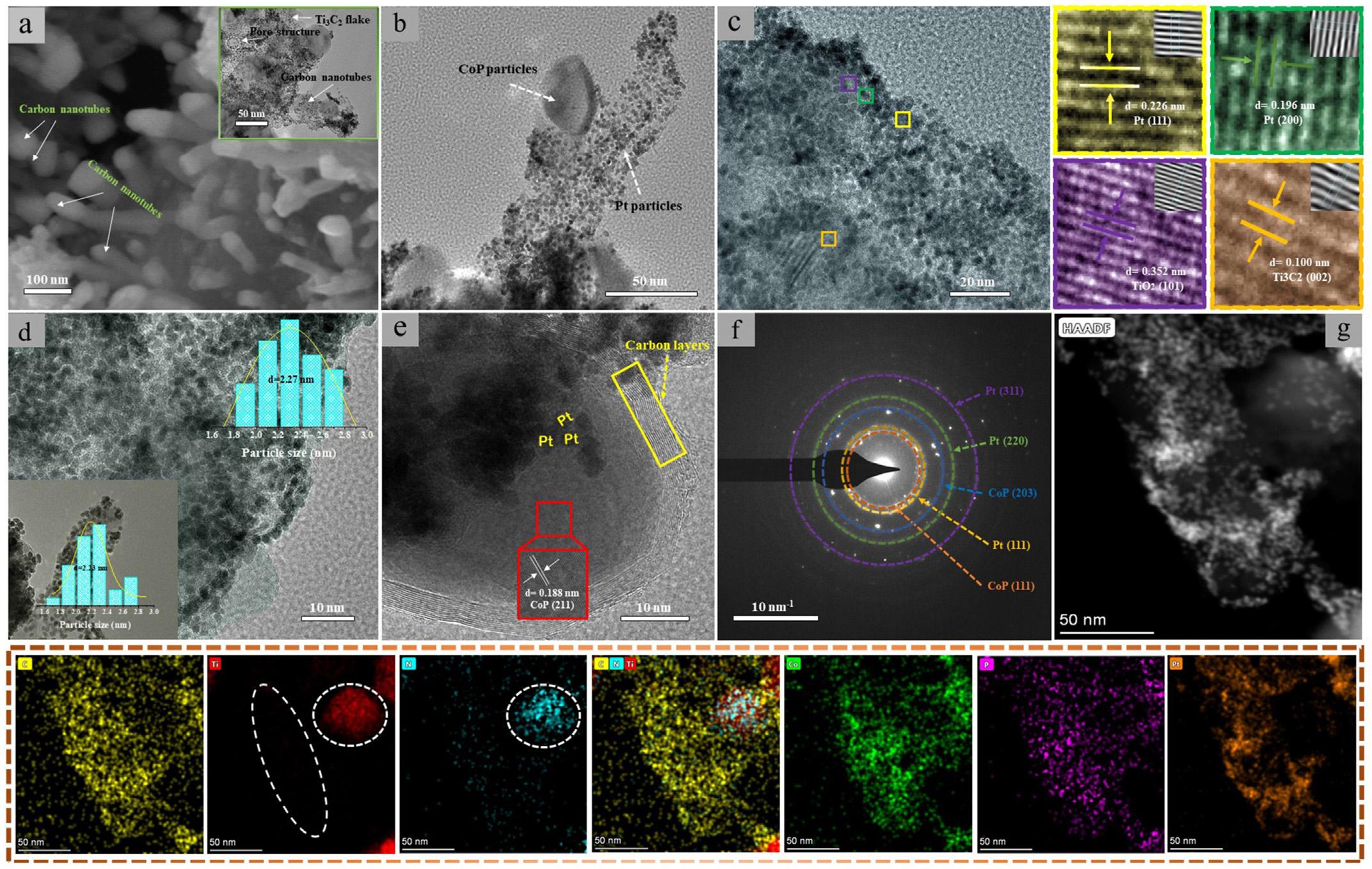

Withanaimoffurtheridentifyingthemicroscopicmorphology ofcatalysts,TEMwasintroducedtocharacterthem(Fig.3).

Aspresentedin Fig.3a,itiscleartoseetheexistenceofnanotubeswhichgrewradialalongtheTi3C2 flakesandtheTi3C2 flakes canbeeasilyobservedfromthelocalamplifiedTEMimage(Fig.3a). Inaddition,somelargerporestructuresareclearlyvisiblein Fig.3a duetoharshetchingtreatmentandtheeffectoflatticenitrogen, whichpartlybrokethepristineTi3C2 structureandgeneratesome porestructures.Theseremainedlargeholestructures,tosome extent,couldgivemorethreephaseboundariesandarebeneficial forthemasstransferprocess.Fromthe Figs.3bandc,itcanbeseen

theadventoftheCoPNPsandthePtNPsishomogenously distributedontothenanotubeandTi3C2,certifyingthe finefabricationofthesecomponents.Asillustratedin Fig.3c,theinterplanardistancesof0.226nmand0.196nmarematchedwith (111)and(200)planeofPt,demonstratingthesuccessfulloadingof PtNPs.The0.100nmcanbelabeledasthe(002)planeofTi3C2. Moreover,the0.352nmoflatticespacingisalsoobserved,referring tothe(101)planeofTiO2.ForcarbonlayerscoatedCoP(Fig.3e),the carbonlayers(redsquareframe)areeffortlesslyobservedandits correlatedlatticespacingcanbefound,inwhichthedistanceof 0.188nmisassignedtothe(211)planeofCoP,provingthe fine formationofCoPNPs.Particularly,attributingtotheanchoreffect ofporouscarbonlayers,manyPtNPs(yellowlabelin Fig.3e)sited atthesurfaceofthecarbon-coatedCoParedetected,whichmay provideabasisforthepossibleinteractionbetweenPtNPsandCoP. TheSAEDpattern(Fig.3f)isconsistentwithaboveresults,where thediffractionringsofCoPandPtaredetectedandtheircorrespondingEDSelementcontentsarelistedin Fig.S7.Forthepurpose offurtherexaminingthestructuralcompositionofcatalyst,the elementmappingwasconducted(Fig.3g).FromtheHAADFimage, thenanotubularstructurederivedfromCoZn-ZIFiscleartoseeand itselementmappingrevealsthepresenceofcorrespondingelements(Ti,C,N,Co,P,andPt).ItisnoteworthythatnoTielement (theregionremarkedbythewhitedottedline)istracedinthe regionwherethenanotubeislocated,whichprovidesstrongevidenceforitscatalyticderivation.Furthermore,itcanbeobserved thatNelementisnotonlydistributesinnanotubularregionbut alsoenrichesinthesameregionasTi(whitedottedline),which

Fig.2. XRDpatternsforprecursors(a),(b),phosphides(c),andfabricatedcatalysts(d).XRD,X-raydiffraction.

probablycanbeconsideredastheevidencefortheformationof dopednitrogen.ForPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (Fig.S8)andPt/Ti3C2 (Fig.S9)catalysts,correlatedelementsarealsodetected,revealing thesuccessfulfabricationforthosecatalysts.Asanimportant parameter,theparticlessizeofPtisinvestigated.Forthesakeof preciselyevaluatingthesizeofPtNPs,wehavesurveyedthePt particlesizeonthecarbonnanotubesandtheTi3C2 itselffor Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2.Asisdepictedin Fig.3d,thePtNPsis evenlydistributionontheTi3C2 andthenanotube.Theaveragesize ofPtNPsontoTi3C2 (displayedin Fig.3d)is2.27nm.Whilethe averagesizefortheseonthenanotubeare2.23nm.Therefore,its finalcalculatedsizewasmeasuredtobe2.25nm.Withrespectto thePt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (Fig.S10a)andPt CoP@NC(Fig.S10b), theaveragesizeiscalculatedtobe2.82nmand2.86nm,individually.AsforthePt/Ti3C2 catalyst(Fig.S10c),itiseasilyobservedthe seriousagglomerationofPtNPsonTi3C2 flakecausedbytheunavoidableoxidationofTi3C2 andtheaveragesizeofPt/Ti3C2 is 3.13nm.ThesmallerparticlesizeofPtforPt CoP@CNTNA/ N Ti3C2 ismainlyduetothehigherspecificsurfaceareasand strongerinteractionofPtwithsubstrateprovidedbythecarbon andnitrogen-enrichedstructure,whichareconductivetomore exposedactivesitesforPtNPs.

Togiveinsightintochemicalcompositionsandstatesforcatalysts,X-rayphotoelectronspectroscopy(XPS)characterizationwas exploited.

Fig.S11 disclosestheshowingofC,Ti,Co,N,P,andPtelements forthePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 andtheirhighresolutionspectra aredisplayedin Fig.4.ForC1s,thespectracanbedividedintoC C, C N,andC Ti,resultingfromthespin-orbitsplittinglocatedat

284.45eV,285.1eV,and282.6eV,respectively[40].AsforTi2p,the peaksat464.2eV,461.5eV,458.6eV,456.9eV,456eV,and 455.2eVarecorrespondingtotheTi O2p1/2,Ti3þ 2p1/2,Ti O2p3/2, Ti3þ 2p3/2,Ti N,andTi C,individually[41].ThepresenceofTi N bondcanberegardastheindicationfordeterminingtheexistence ofdopedlatticeN,whichdopeintothebulkphasestructureofTi3C2 andformnewchemicalbonds,thussignificantlyimprovingits catalyticproperties. Fig.4gshowsitsschematicdiagramofthe N Ti3C2 anditcanbeobservedthatsomepristineatomsare replacedbyNfortheformationofTi Nbond,thereforebroking originalstructureandintroducingsomestructuraldefectivesites. ForthespectraofCo2p,theCo N,Co3þ 2p,Co2þ 2p,andCosatellitepeaksaretraced,inwhichthepeaksat802.3eV,797.9eV, 785.4eV,783.7eV,and781.7eVareassignedtotheCo2þ 2p1/2, Co3þ 2p1/2,Co2þ 2p3/2,Co N,Co3þ 2p3/2,separately.Andthepeaks at804.9eVand787.3eVrefertotheCosatellitepeaks.The observedCo3þ/2þ 2paremainlyderivedfromtheformationofCoP. TheP2pforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (Fig.S12a)exhibitsthree predominantpeakssitedat134.15eV,129.5eV,and130.4eV, ascribingtotheP O,P2p3/2,andP2p1/2,respectively[42].For Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (Fig.S12b),thesimilarthreetypepeaksofP 2parealsodetected.

Threepeaksat400.8eV,399.6eV,and397.8eVforN1sare emerged,whicharecorrespondingtotheGraphiticN,PyrrolicN, andlatticeN,respectively[43].Theresembletypesofpeaksarealso foundforPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (Fig.S13a).SincethelatticenitrogencouldbedopedintotheTi3C2,thoseTi3C2-basedcatalystsexpressdifferentN1speaksthanPt CoP@NC(Fig.S13b),wherethe PyridinicNisobservedonlyforPt CoP@NC.TheshownN1sfor

W.Zhan,L.MaandM.Gan

Fig.3. HighresolutionSEMandTEMimagesofPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (a),(b),highresolutionTEMimage(c),(e),particlesizedistributionofPtNPs(d),SAEDpatternforthe catalyst(f),HAADFandcorrespondingelementsmappingforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (g).CNT,carbonnanotube;NP,nanoparticle;SEM,scanningelectronmicroscopy;TEM, transmissionelectronmicroscopy.

Fig.4. XPSspectraofC1s(a),Ti2p(b),Co2p(c),N1s(d),Pt4fforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (e),Pt4fforallcatalysts(f),schematicdiagramofN Ti3C2 (g),andrelativeratioof threetypesNforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2,andPt CoP@NCcatalysts(h).CNT,carbonnanotube;XPS,X-rayphotoelectronspectroscopy.

thesecatalystsdemonstratethepossibledopingofNintothecarriers.Theircorrespondingrelativeratioandbindingenergyfor thesetypesNareshownin Fig.4hand TableS1.Ithasbeentested thattherelativecontentofNinallelementis6.45%,6.12%,and

6.36%forPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2,and Pt CoP@NC,respectively.AnditcanbeobservedthatPt CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2 andPt CoP@NCpresenthigherrelativeratioofPyrrolicNbutlowerrelativeratioofGraphiticN.Thiscouldbeascribed

totheevaporationofZnatcalcinationstep,whichfavorsthegenerationofmoredefectivesites,thereforecontributingtodopingof thePyrrolicN.TheRamanspectraresults(Fig.S14)supportthe aboveconclusion,whichunveilthehigherdegreeofdefectsfor Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (ID/IG ¼ 1.02)andPt CoP@NC(ID/ IG ¼ 1.03)thanPt CoP@NC(ID/IG ¼ 0.98),demonstratingtheeffect ofZnfortheformationofhigherdefectivestructure.Itisworth notingthatthecatalystwithabundantamountofdefectiveNcan strengthentheinteractionbetweencarrierandPtNPs,facilitating thehigherdispersionofPtNPs.

ThePt4fforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalystcanbedeconvolutedintotwotypesofPt[44].Theintensepairofdoublepeaksat 70.72eV,74.07eVreferstothePt(0)speciesandthetwopeaksat 71.70eVand75.10eVareindexedwiththePt(II)species,which maybebroughtbytheoxidationofPtsurface.Othercatalystwas alsosurveyedforcomparison(Fig.S15)andhavebeenlistedin Table1.Itshowsthatthephosphides-containingcatalystshold highercontentofPt(0)thanPt/Ti3C2 catalyst,whichmaybedueto thattheexistingelectroniceffectbetweenPtandCoPaswellas dopedlatticeNcouldstablethePtNPs.ThiscanbefurtherdeterminedbythehighresolutionXPSspectraofPt(Fig.4f).Itcanbe noticedthatthosephosphides-containingcatalystsexhibita remarkabledownshiftofBEcomparedwiththePt/Ti3C2.To circumventtheeffectofplatinumloading,ICP-OESwascarriedout fordeterminingtheloadingofPt.Theresultshowsthatthemass loadingofPtis19.15%,19.07%,19.47%,and18.95%forPt CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC,andPt/Ti3C2, separately,whichareveryclosetothetheoreticalvalue(20%). Strikingly,thePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 andPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 catalystsshowmoredownshiftthanPt CoP@NCandPt CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2 displaysthemostnegativeshift(0.58eV)thanthatof Pt/Ti3C2.Itcanbeinterpretedastheeffectoflatticenitrogen,in whichthedopedlatticeNsufficientlyalterthesurfacepropertyof Ti3C2 andimproveitselectronicinteractionwithPtNPs.This conclusionisagreedwiththeXPSspectraofN1s(Fig.S16),where thepositiveshiftofN1sforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 and Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 comparedwiththatofPt CoP@NCare observed.ThenegativeshiftforPt4fisbeneficialforthedownshift ofd-bandcenter,weakeningthepoisoningeffectforPt-based catalyst.Therefore,thehighercontentofPt(0)andintenseelectroninteractionforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 couldboosttheMOR.

3.2.Electrocatalyticproperties

Forevaluatingtheanti-COpoisoningcapacityforthesecatalysts, theCO-strippingexperimentwasintroduced[45].Asisshownin Fig.5,thePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 submitsthelowestonsetpotential(0.575V)thanPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (0.576V),Pt CoP@NC (0.604V),Pt/C(0.609V),andPt/Ti3C2 (0.670V).Furthermore, Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 alsoremainsmuchlowerpeakpotential (0.627V)thanPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (0.637V),Pt CoP@NC (0.674V),Pt/C(0.692V),andPt/Ti3C2 (0.712V),provingitssuperb

Table1

ThecorrespondingratiosoftwotypesofPt4f.

resistanceagainstCOpoisoning.Particularly,thePt/Ti3C2 andPt/C catalystsshowmuchhigherpeakpotentialthanothers,indicating theco-catalyticeffectofCoP,whichprovides-OHads atlowerpotentialfortheoxidationofCOandachieveselectronicinteraction withPt.Meanwhile,itcanbeobservedthatthoseN-dopedTi3C2 catalystsexhibitmorelowerpeakpotentialthanPt CoP@NC catalyst,suggestingthatlatticeNisinfavoroffurtherdownshiftof d-bandcenterandthusreducestheCOpoisoning.Aboveoxidation processisfurtherillustratedbythemechanismdiagram,inwhich thelatticeandformedCoPcouldsynergisticallydecreasethedbandcenterofPtsothattheadsorptionintensityforCOads couldbe reduced.Furthermore,theCoPcandissociatethewateratlower potentialfortheformationof-OHads.Therefore,reactingwith adsorbedCOonthesurfaceofPtandenhancingitsresistance againstCO.

Forthesakeoffurtherexaminingtheiranti-COpoisoningcapacity,thechronopotentiometric(CP)measurementwascarried out[46].Asisdepictedin Fig.S17,theCOads speciesareaccumulatedontheactivesitesofPtandhinderitssubsequentelectrochemicalreaction.Whenthecatalystsarefurtherpoisoned,the MORcouldbestopped.Tocontinuetheelectrocatalyticreaction, thepotentialmustclimbtothehigherpotential.Itcanbenoticed thatPt FeCoP/NCNTandPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 catalystscanhold thepotentialforthelongertimeofabout672sand400.4swhen comparedwiththatforPt CoP@NC(365.2s),andPt/Ti3C2 (113s) catalysts,confirmingtheirexceptionalpoisontolerance.The increasedresistanceagainstCOpoisoningcomparedwiththatof Pt CoP@NCmayderivefromtheeffectoflatticeN,whichunderminetheadsorptionofCO-intermediatethroughtheinteraction withPtNPs.

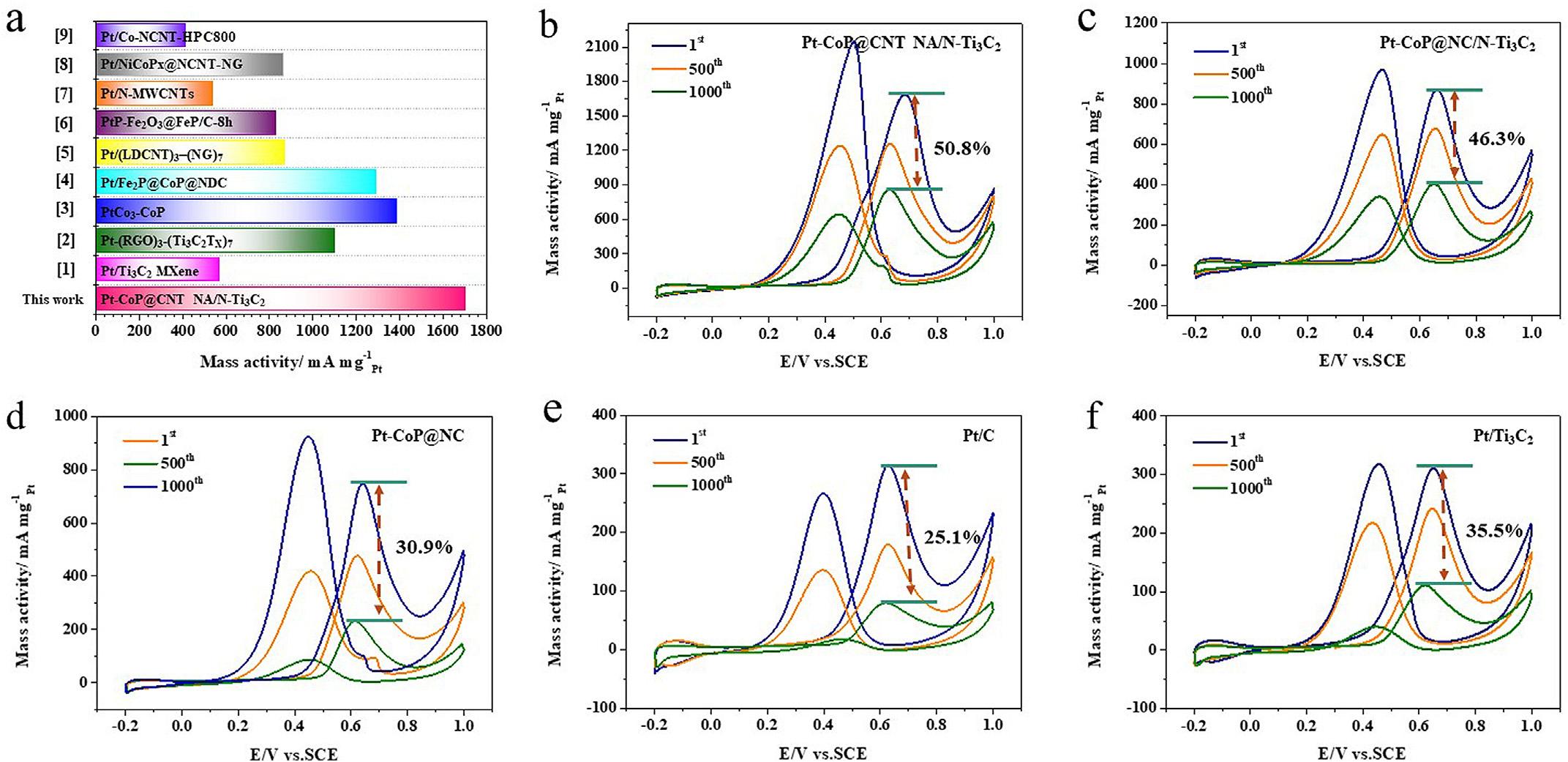

Toexploretheelectrochemicalperformanceforcatalysts,the cyclicvoltammetrytestwasperformed.Asispresentedin Fig.6a, allcatalystssubmitthecharacteristicpeaksofPtatrelativelylow potentialandtheirelectrochemicalsurfacearea(ECSA)are computed(TableS2).Itcanbeclearlyobservedthatthe Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 possesshigherECSA(97.70m2 g 1)than Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (69.95m2 g 1),Pt CoP@NC(42.83m2 g 1), Pt/C(43.95m2 g 1),andPt/Ti3C2 (22.02m2 g 1).ThehighestECSA forPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalystisattributedtothehighly dispersionofultrafinePtNPs,whichfavorsthemoreexposedactive sitesofPtsurface.AsforthelowestECSAofPt/Ti3C2 catalyst,itmay betheresultofitsfeweranchorsitesforthedepositionofPt,giving risetotheunevendistributionoflargerPtNPsonTi3C2.For obtainingtheirelectrocatalyticactivity,thesecatalystswerefurther immersedin0.5MH2SO4 þ 1MCH3OHsolution.Asispresentedby Fig.6band TableS2,Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 exhibitsmuch highermassactivity(1704mA/mgPt)thanPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (868.78mA/mgPt),Pt CoP@NC(618mA/mgPt),Pt/C(479.4mA/ mgPt),andPt/Ti3C2 (291.85mA/mgPt)owingtoitsremarkablecocatalyticeffectofCoPandlatticeNaswellasthemoreaccessible activesitesonthePtsurface,manifestingitssuperbcatalyticactivity.Toexamineitsabilitytoremovethecarbonaceousspecies,

SamplePt(0)Pt(II)

Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2

Bindingenergy(eV)Ratio%Bindingenergy(eV)Ratio%

70.7234.5871.7012.34 74.0745.1775.107.91

Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 70.7730.9971.7710.43 74.1843.5276.0915.05

Pt CoP@NC70.8430.5671.7810.18 74.2545.7676.2813.50

Pt/Ti3C2 71.1921.4672.0714.98 74.6544.2876.9619.29

Fig.5. COstrippingcurve(a)andcorrespondingonsetandpeakspotential(b)forallcatalystsanditspossiblemechanismforoxidationofCO.

Fig.6. CVcurve(a),massactivity(b)performedin0.5MH2SO4 þ 1MCH3OHsolution,specificactivity(c)andtheircorrespondingspecificvalues(d),CAcurve(e),theirrelative retainedmassactivityandretainedratio(f)forallcatalysts.CA,chronoamperometric;CV,cyclicvoltammetry. W.Zhan,L.MaandM.Gan

theIf/Ibvaluewascalculated.Asisdepictedin TableS3,wecansee thatPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 presentshigherIf/Ibvaluethanthat ofPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC,andPt/Ti3C2,indicatingits enhancedabilitytoremovethosecarbonaceousspecies.Whilefor thehighvalueofPt/C,itmightbethatthefeweradsorbedintermediates(smallerECSAvalue)areeasiertoremove,therefore exhibitinghigherIf/Ibvalue.Furthermore,thespecificactivity,as animportantfactor,wasalsoinvolved(Fig.6c)andthespecific activityarecalculatedtobethe1.76mAcm 2Pt,1.44mAcm 2 Pt, 1.33mAcm 2Pt,1.24mAcm 2Pt,and1.09mAcm 2Pt,withrespect toPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2,Pt CoP@NC, Pt/CandPt/Ti3C2,respectively,indicatingtheexcellentcatalytic performanceofperPtactivesiteforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2. Additionally,toverifytheadvancednatureofthecatalyst,other recentlyreportedMORcatalystswereintroducedforcomparisonin Fig.7aand TableS4.ItiseasilyfoundthatPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalystsubmitsmuchhigherMORactivitythanthosecatalysts, verifyingitspotentiallyexcellentcatalyticperformanceformethanoloxidation.

Stabilityforcatalystswasthenexaminedbychronoampero metrictest,whichweredisplayedin Fig.6e.Itcanbeseenthesteep degradationofmassactivityoccurredatthebeginningduetothe

poisoningeffect.Afterward,thisdownwardtrendbecomes flatand themassactivitykeepsstablenearthe3600s.Theretainedmass activityandcorrespondingretainedratioforallcatalystsareshownin Fig.6f.ItdisplaysthatthePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 remainsthe higherretainedmassactivity(313.5mA/mgPt)andretainedratio (21.6%)thanPt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 (169.2mA/mgPt,19.7%), Pt CoP@NC(54.7mA/mgPt,9.9%),Pt/C(13.3mA/mgPt, 3.1%),andPt/ Ti3C2 (21.97mA/mgPt,10%).TheimpressivestabilityforPt CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2 canbetracedbacktoitsstronganti-COpoisoningcapacityandstructuralstabilityofcarrier,whichdeliversthestrong anti-electrochemicalcorrosionability.ChronoamperometricresultingforPt/Ti3C2 furthersupportstheideal,wherethePt/Ti3C2 holds thehigherretainedratiothanPt/Cbecauseofitsstrongantielectrochemicalcorrosioncapacity.

Goingafurthersteptoexaminetheirstability,accelerated durabilitytest(ADT)wasthereforeinvestigated.Aspresentedin Fig.7,allthecatalystsshowpredominantdegradationofactivity consideringthestrongelectrochemicalcorrosionforlong-term testing,causingthecollapseofthecarrier,andpossibleshedding ofplatinum.Asexpected,thePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalyst manifeststheperfectdurabilitywith50.8%massactivityremained. Meanwhile,Pt CoP@NC/N Ti3C2 possesseshigherretainedratio

W.Zhan,L.MaandM.Gan

Fig.7. Massactivityforrecentlyreportedcatalysts(a),ADTcurves(1000cycles)immersedin0.5MH2SO4 þ 1MCH3OHsolutionforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (b),Pt CoP@NC/ N Ti3C2 (c),Pt CoP@NC(d),Pt/C(e),andPt/Ti3C2 (f).ADT,accelerateddurabilitytest;CNT,carbonnanotube.

(46.3%)thanPt CoP@NC(30.9%),Pt/C(25.1%),andPt/Ti3C2 (35.5%), suggestingtheexcellentstructuralstabilityforthoseN Ti3C2basedcatalysts.ItshouldbenoticedthatthePt/Ti3C2 isprovided withthehigherratiothanPt/CandPt CoP@NC,provingthe excellentstabilityofTi3C2 carrier.

TogetinsightintotheMORkineticprocessesandthestatusof impedanceforcatalysts,electrochemicalimpedancespectros copywasconducted(Fig.8).Fromthe Fig.8a,wecanseethatall catalystsexhibitthetopicalNyquistplots.Toobtainmoreunderlie information,equivalentcircuitwasproposedto fittheplots.As

Fig.8. Electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy(EIS)andcorrespondingequivalentcircuitforcatalysts(a),theEISbeforeandafterADTforPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (b),Pt/C(c) andPt/Ti3C2 (d).ADT,accelerateddurabilitytest;CNT,carbonnanotube;EIS,electrochemicalimpedancespectroscopy.

demonstratedin Fig.8a,theRct representsthechargetransfer resistancewhilethestraightlineatlowfrequencyzerostandsfor thewarburgimpedance(W),whichreflectsthesemi-infinite diffusionofionsatthecatalyst/electrolyteinterface[47,48].Listed in TableS5 arethecorrespondingparametersthatwereusedto producethesimulated fittingcurves.Ingeneral,thesmallerRct valueindicatesthefastercatalytickineticrateatthecatalyst/electrolyteinterfaceandthehigherWusuallyshowsfasterdiffusionof ionsattheinterface.Apparently,thePt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 withthesmallestRct value(3.927 U cm 2)unfoldsitsfasterreactionratethanothers,whichisinaccordancewiththeaboveelectrochemicalresults.Inaddition,Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 catalyst alsoexhibitsthehighestwarburgimpedance,whichismore conductivetothediffusionofionstothecatalyticinterface.The possiblereasonsforthisresultcanbesummarizedasfollows:the defectsandporous-enrichedstructuremakemorethree-phase interfacepreserved,whicharebeneficialforthemasstransfer. Besides,thehighlydisperseofultrafinePtNPsandstrongresistanceagainstCOpoisoningcontributetoenhancedcatalyticperformanceforperactivesitesofPtsurface,whichcouldoptimizethe catalytickineticprocess.Furthermore,thepossibleexcellentconductivityachievedbytheintroductionofnanotubearray-like structureensuresitslowerimpedanceforelectronictransfer. Whatismore,wealsoinvestigatedtheelectrochemicalimpedance spectroscopyofcatalystsafterADT(Figs.8b,c,d)andtheircorrespondingparametershavelistedin TableS6.Itcanbeseenthat thesecatalystspresentincreasedRct duetothecorrosionofelectrochemicalandthePt/Ti3C2 catalystpossessesmuchlargerRct becauseofthepossibleoxidationeffect,whichcouldseverely weakenitsconductivityandstructuralintegration.

Tofurtherexploretheconductivityforcatalysts,thefour-probe metermeasurementwasperformed.Aslistedin TableS7,the electricalconductivityofPt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 (9728S/m)is comparablewiththatofPt/CandthePt/Ti3C2 catalystpossesses lowestelectricalconductivity(737.4S/m),declaringthatintroductionofnanotubesanddopedNcansufficientlyimproveits overallconductivityandreducetheimpactofoxidationonTi3C2. Besides,itcanbeobservedthatthechargetransferresistanceofPt/ Ti3C2 (Fig.8d)afterADTdecreasedmore,indicatingitsoxidation effectduringtheelectrochemicaltest.Thisresultisfurther demonstratedbythefour-probemeterafterADT(TableS7),which displaysmoresharpdecreaseofelectricalconductivityforPt/Ti3C2 thanothers,provingitsoxidationeffectagaintowardtheimpedanceandconductivity.Therefore,Pt CoP@CNTNA/N Ti3C2 with carbonandN-enrichedstructurecanensureitslowerimpedance evenafterlongtimeelectrochemicaltest,whichbenefitthehigh catalyticactivity.

4.Conclusion

Insummary,theultrafinePtNPstabilizedbythecarbon encapsulatedCoPnanoarray-likearchitecturesontonitrogendopedTi3C2TX MXeneisfabricated,inwhichtheCoZn-ZIFserves asthesacrificialtemplateforthederivationofcarbonnanotubes andactsasnitrogensourcesfortheformationofdopednitrogen especiallyforthoselatticeN,renderingthebifunctionaleffect. ThankstotheopensurfaceforTi3C2 itselfaswellasthecatalytic effectofmetals,theCoPencapsulatedbythenanotubenanoarraylikestructureisobtainedonlyforthetargetcatalyst(Pt CoP@CNT NA/N Ti3C2).Theseporouscarbonnanotubescombinedwiththe effectofNareinfavoroftheincreasedconductivityandformation ofmoreanchorsites,leadingtomoreexposedactivesitesofPt surface.Inaddition,theintroducedlatticeNandtheformedCoP canachievetheexcellentco-catalyticeffectthroughtheelectronic interactionwithPt,whichcouldsufficientlyreducetheCO

poisoningandstabilizePtformorePt(0)preserved,giving enhancedcatalyticactivityforperactivesitesofPtsurface.More important,thestabilityofcarriersensurestheirretainedhighcatalyticactivityforlong-termtesting.Therefore,thecatalystdelivers superhighelectrocatalyticperformance.Obviously,thisworkpresentsnovelidealforconstructingTi3C2-basednovel3Darchitecture withexcellentMORactivityandstability.

Authorshipcontributionstatement

WangZhan: Conceptualization,Methodology,Investigation, Software,Writing-originaldraft,Writing-review & editing. LiMa: Investigation,Formalanalysis,Supervision,Writing-review & editing. MengyuGan: Resources,Visualization,Supervision, Fundingacquisition,Validation.

Declarationofcompetinginterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompeting financialinterestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedto influencetheworkreportedinthispaper.

Acknowledgments

ThisworkwassupportedbytheNationalNaturalScienceFoundationofChina(GrantNo.21676034).

AppendixA.Supplementarydata

Supplementarydatatothisarticlecanbefoundonlineat https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.101041.

References

[1] V.Radmilovic,H.A.Gasteiger,P.N.Ross,Structureandchemicalcomposition ofasupportedPt-Ruelectrocatalystformethanoloxidation,J.Catal.154 (1995)98 106

[2] S.Zhao,Y.Yang,Z.Tang,Insightintostructuralevolution,activesites,and stabilityofheterogeneouselectrocatalysts,Angew.Chem.Int.Ed.61(2022), e202110186

[3] K.-H.Wu,Y.Liu,X.Tan,Y.Liu,Y.Lin,X.Huang,Y.Ding,B.-J.Su,B.Zhang,J.M.Chen,W.Yan,S.C.Smith,I.R.Gentle,S.Zhao,Regulatingelectrontransfer overasymmetriclow-spinCo(II)forhighlyselectiveelectrocatalysis,Chem. Catalysis2(2022)372 385.

[4] J.Lee,C.Eickes,M.Eiswirth,G.Ertl,Electrochemicaloscillationsinthe methanoloxidationonPt,Electrochim.Acta47(2002)2297 2301

[5] Y.Gogotsi,R.M.Penner,Energystorageinnanomaterials-capacitive,pseudocapacitive,orbattery-like?ACSNano12(2018)2081 2083

[6] E.H.Yu,K.Scott,R.W.Reeve,AstudyoftheanodicoxidationofmethanolonPt inalkalinesolutions,J.Electroanal.Chem.547(2003)17 24

[7] S.M.Alia,G.Zhang,D.Kisailus,D.Li,S.Gu,K.Jensen,Y.Yan,Porousplatinum nanotubesforoxygenreductionandmethanoloxidationreactions,Adv.Funct. Mater.20(2010)3742 3746

[8] K.Routray,W.Zhou,C.J.Kiely,I.E.Wachs,Catalysisscienceofmethanol oxidationoverironvanadatecatalysts:natureofthecatalyticactivesites,ACS Catal.1(2011)54 66

[9] A.Kongkanand,K.Vinodgopal,S.Kuwabata,P.V.Kamat,HighlydispersedPt catalystsonsingle-walledcarbonnanotubesandtheirroleinmethanol oxidation,J.Phys.Chem.B110(2006)33

[10] Y.Yang,C.Tan,Y.Yang,L.Zhang,B.-W.Zhang,K.-H.Wu,S.Zhao,Pt3Co@Pt Core@shellnanoparticlesasefficientoxygenreductionelectrocatalystsin directmethanolfuelcell,ChemCatChem13(2021)1587 1594

[11] O.T.Ajenifujah,A.Nouralishahi,S.Carl,S.C.Eady,Z.Jiang,L.T.Thompson, Platinumsupportedonearlytransitionmetalcarbides:efficientelectrocatalystsformethanolelectro-oxidationreactioninalkalineelectrolyte, Chem.Eng.J.406(2021)

[12] Z.Yan,G.He,P.K.Shen,Z.Luo,J.Xie,M.Chen,MoC graphitecompositeasa Ptelectrocatalystsupportforhighlyactivemethanoloxidationandoxygen reductionreaction,J.Mater.Chem.2(2014).

[13] C.He,J.Tao,G.He,P.K.Shen,Ultrasmallmolybdenumcarbidenanocrystals coupledwithreducedgrapheneoxidesupportedPtnanoparticlesas enhancedsynergisticcatalystformethanoloxidationreaction,Electrochim. Acta216(2016)295 303

[14] H.Huang,S.Yang,R.Vajtai,X.Wang,P.M.Ajayan,Pt-decorated3Darchitecturesbuiltfromgrapheneandgraphiticcarbonnitridenanosheetsas efficientmethanoloxidationcatalysts,Adv.Mater.26(2014)5160 5165

[15] Y.Xiao,Z.Fu,G.Zhan,Z.Pan,C.Xiao,S.Wu,C.Chen,G.Hu,Z.Wei,Increasing Ptmethanoloxidationreactionactivityanddurabilitywithatitaniummolybdenumnitridecatalystsupport,J.PowerSources273(2015)33 40

[16] M.M.OttakamThotiyl,T.Ravikumar,S.Sampath,Platinumparticlessupported ontitaniumnitride:anefficientelectrodematerialfortheoxidationof methanolinalkalinemedia,J.Mater.Chem.20(2010)

[17] Y.Duan,Y.Sun,L.Wang,Y.Dai,B.Chen,S.Pan,J.Zou,EnhancedmethanoloxidationandCOtolerance29usingoxygen-passivatedmolybdenum phosphide/carbonsupportedPtcatalysts,J.Mater.Chem.4(2016) 7674 7682

[18] J.Zhu,G.He,P.K.Shen,AcobaltphosphideoncarbondecoratedPtcatalyst withexcellentelectrocatalyticperformancefordirectmethanoloxidation, J.PowerSources275(2015)279 283

[19] Z.Yang,Y.Kong,H.Tao,Q.Huang,C.Wang,Z.Pei,H.Wang,Y.Liu,Y.Wang,S.Li, X.Liao,W.Yan,S.Zhao,Cation-vacancy-enrichednickelphosphideforefficient electrosynthesisofhydrogenperoxides,Adv.Mater.34(2022),2106541.

[20] J.Chang,L.Feng,C.Liu,W.Xing,X.Hu,Ni2Penhancestheactivityand durabilityofthePtanodecatalystindirectmethanolfuelcells,EnergyEnviron.Sci.7(2014)

[21] M.Yan,Q.Jiang,T.Zhang,J.Wang,L.Yang,Z.Lu,H.He,Y.Fu,X.Wang, H.Huang,Three-dimensionallow-defectcarbonnanotube/nitrogen-doped graphenehybridaerogel-supportedPtnanoparticlesasefficientelectrocatalyststowardthemethanoloxidationreaction,J.Mater.Chem.6(2018) 18165 18172

[22] J.-P.Zhong,C.Hou,L.Li,M.Waqas,Y.-J.Fan,X.-C.Shen,W.Chen,L.-Y.Wan, H.-G.Liao,S.-G.Sun,AnovelstrategyforsynthesizingFe,N,andStridoped graphene-supportedPtnanodendritestowardhighlyefficientmethanol oxidation,J.Catal.381(2020)275 284

[23]Y.Yang,Y.Yang,Y.Liu,S.Zhao,Z.Tang,Metal OrganicFrameworksfor Electrocatalysis:BeyondTheirDerivatives.SmallSci.1:2100015. https://doi. org/10.1002/smsc.202100015

[24] Y.-S.Wang,S.-Y.Yang,S.-M.Li,H.-W.Tien,S.-T.Hsiao,W.-H.Liao,C.-H.Liu, K.-H.Chang,C.-C.M.Ma,C.-C.Hu,Three-dimensionallyporousgraphene carbonnanotubecomposite-supportedPtRucatalystswithanultrahigh electrocatalyticactivityformethanoloxidation,Electrochim.Acta87(2013) 261 269

[25] Y.Xiao,G.Zhan,Z.Fu,Z.Pan,C.Xiao,S.Wu,C.Chen,G.Hu,Z.Wei,Robust non-carbontitaniumnitridenanotubessupportedPtcatalystwithenhanced catalyticactivityanddurabilityformethanoloxidationreaction,Electrochim. Acta141(2014)279 285.

[26] C.Wang,S.Chen,L.Song,Tuning2DMXenesbysurfacecontrollingand interlayerengineering:methods,properties,andsynchrotronradiation characterizations,Adv.Funct.Mater.30(2020)

[27] A.Lipatov,M.Alhabeb,M.R.Lukatskaya,A.Boson,Y.Gogotsi,A.Sinitskii, Effectofsynthesisonquality,electronicpropertiesandenvironmental stabilityofindividualmonolayerTi3C2MXene fl akes,Adv.ElectronicMater. 2(2016)

[28] S.Zhu,C.Wang,H.Shou,P.Zhang,P.Wan,X.Guo,Z.Yu,W.Wang,S.Chen, W.Chu,L.Song,InsituarchitectingendogenousheterojunctionofMoS2 couplingwithMo2CTxMXenesforoptimizedLi(þ)storage,Adv.Mater.34 (2022),e2108809

[29] C.Yang,Q.Jiang,H.Huang,H.He,L.Yang,W.Li,Polyelectrolyte-induced stereoassemblyofgrainboundary-enrichedplatinumnanowormsonTi3C2Tx MXenenanosheetsforefficientmethanoloxidation,ACSAppl.Mater.Interfaces12(2020)23822 23830

[30] W.Zhan,L.Ma,M.Gan,F.Xie,Ultra-finebimetallicFeCoPsupportedbyNdopedMWCNTsPt-basedcatalystforefficientelectrooxidationofmethanol, Appl.Surf.Sci.585(2022)

[31] X.Zhang,J.Zhu,C.S.Tiwary,Z.Ma,H.Huang,J.Zhang,Z.Lu,W.Huang,Y.Wu, Palladiumnanoparticlessupportedonnitrogenandsulfurdual-dopedgrapheneashighlyactiveelectrocatalystsforformicacidandmethanoloxidation,ACSAppl.Mater.Interfaces8(2016)10858 10865

[32] Y.Zhuang,Y.Liu,X.Meng,FabricationofTiO2nanofibers/MXeneTi3C2 nanocompositesforphotocatalyticH2evolutionbyelectrostaticself-assembly,Appl.Surf.Sci.496(2019)

[33] B.Kong,J.Tang,Y.Zhang,T.Jiang,X.Gong,C.Peng,J.Wei,J.Yang,Y.Wang, X.Wang,G.Zheng,C.Selomulya,D.Zhao,Incorporationofwell-dispersed sub-5-nmgraphiticpencilnanodotsintoorderedmesoporousframeworks, Nat.Chem.8(2016)171 178

[34] Z.Cui,C.Zu,W.Zhou,A.Manthiram,J.B.Goodenough,Mesoporoustitanium nitride-enabledhighlystablelithium-sulfurbatteries,Adv.Mater.28(2016) 6926 6931

[35] L.He,J.Liu,B.Hu,Y.Liu,B.Cui,D.Peng,Z.Zhang,S.Wu,B.Liu,Cobaltoxide dopedwithtitaniumdioxideandembeddedwithcarbonnanotubesand graphene-likenanosheetsforefficienttrifunctionalelectrocatalystof hydrogenevolution,oxygenreduction,andoxygenevolutionreaction, J.PowerSources414(2019)333 344.

[36] M.Naguib,M.Kurtoglu,V.Presser,J.Lu,J.Niu,M.Heon,L.Hultman, Y.Gogotsi,M.W.Barsoum,Two-dimensionalnanocrystalsproducedbyexfoliationofTi3AlC2,Adv.Mater.23(2011)4248 4253

[37] B.Wang,M.Wang,F.Liu,Q.Zhang,S.Yao,X.Liu,F.Huang,Ti3C2:anideal Co-catalyst?Angew.Chem.Int.Ed.59(2020)1914 1918

[38] G.Kaur,R.K.Rai,D.Tyagi,X.Yao,P.-Z.Li,X.-C.Yang,Y.Zhao,Q.Xu,S.K.Singh, Room-temperaturesynthesisofbimetallicCo Znbasedzeoliticimidazolate frameworksinwaterforenhancedCO2andH2uptakes,J.Mater.Chem.4 (2016)14932 14938

[39] F.Xia,J.Lao,R.Yu,X.Sang,J.Luo,Y.Li,J.Wu,AmbientoxidationofTi3C2 MXeneinitializedbyatomicdefects,Nanoscale11(2019)23330 23337

[40] Y.Li,X.Deng,J.Tian,Z.Liang,H.Cui,Ti3C2MXene-derivedTi3C2/TiO2 nanoflowersfornoble-metal-freephotocatalyticoverallwatersplitting,Appl. Mater.Today13(2018)217 227

[41] W.Bao,L.Liu,C.Wang,S.Choi,D.Wang,G.Wang,Facilesynthesisof crumplednitrogen-dopedMXenenanosheetsasanewsulfurhostforlithiumsulfurbatteries,Adv.EnergyMater.8(2018)

[42] L.Yan,B.Zhang,S.Wu,J.Yu,Ageneralapproachtothesynthesisoftransition metalphosphidenanoarraysonMXenenanosheetsforpH-universal hydrogenevolutionandalkalineoverallwatersplitting,J.Mater.Chem.8 (2020)14234 14242

[43] J.Chen,X.Yuan,F.Lyu,Q.Zhong,H.Hu,Q.Pan,Q.Zhang,IntegratingMXene nanosheetswithcobalt-tippedcarbonnanotubesforanefficientoxygen reductionreaction,J.Mater.Chem.7(2019)1281 1286.

[44] H.Liu,D.Yang,Y.Bao,X.Yu,L.Feng,One-stepefficientlycouplingultrafine Pt Ni2Pnanoparticlesasrobustcatalystsformethanolandethanolelectrooxidationinfuelcellsreaction,J.PowerSources434(2019)

[45] H.Li,Y.Pan,D.Zhang,Y.Han,Z.Wang,Y.Qin,S.Lin,X.Wu,H.Zhao,J.Lai,B.Huang, L.Wang,Surfaceoxygen-mediatedultrathinPtRuM(Ni,Fe,andCo)nanowires boostingmethanoloxidationreaction,J.Mater.Chem.8(2020)2323 2330

[46] C.Yang,Q.Jiang,W.Li,H.He,L.Yang,Z.Lu,H.Huang,UltrafinePt nanoparticle-decorated3Dhybridarchitecturesbuiltfromreducedgraphene oxideandMXenenanosheetsformethanoloxidation,Chem.Mater.31(2019) 9277 9287

[47] D.Chakraborty,I.Chorkendorff,T.Johannessen,Electrochemicalimpedance spectroscopystudyofmethanoloxidationonnanoparticulatePtRudirect methanolfuelcellanodes:kineticsandperformanceevaluation,J.Power Sources162(2006)1010 1022

[48] Z.Li,L.Zhang,X.Huang,L.Ye,S.Lin,Shape-controlledsynthesisofPtnanoparticlesviaintegrationofgrapheneand b-cyclodextrinandusingasanoval electrocatalystformethanoloxidation,Electrochim.Acta121(2014) 215 222

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

It was not, however, until I reached Denmark, saw the schools themselves, and talked with some of the teachers—not, in fact, until after I had left Denmark and had an opportunity to look into and study their history and organization—that I began to comprehend the part that the rural high schools were playing in the life of the masses of the Danish people, and to understand the manner in which they had influenced and helped to build up the agriculture of the country.

There are two things about these rural high schools that were of peculiar interest to me: First, they have had their origin in a movement to help the common people, and to lift the level of the masses, particularly in the rural district; second, they have succeeded. I venture to say that in no part of the world is the general average intelligence of the farming class higher than it is in Denmark. I was impressed in my visits to the homes of some of the small farmers by the number of papers and magazines to be found in their homes.

In recent years there has sprung up in many parts of Europe a movement to improve the condition of the working masses through education. Wherever any effort has been made on a large scale to improve agriculture, it has almost invariably taken the form of a school of some sort or other. For example, in Hungary, the state has organized technical education in agriculture on a grand scale. Nowhere in Europe, I learned, has there been such far-reaching effort to improve agriculture through experimental and research stations, agricultural colleges, high schools, and common schools. There is this difference, however: Hungary has tried to improve agriculture by starting at the top, creating a body of teachers and experts who are expected in turn to influence and direct the classes below them. Denmark has begun at the bottom.

One of the principal aims of the Hungarian Government, as appears from a report by the Minister of Agriculture, was “to adapt the education to the needs of the different classes and take care, at the same time, that these different classes did not learn too much, did not learn anything that would unfit them for their station in life.”

I notice, for example, that it was necessary to close the agricultural school at Debreczen, which was conducted in connection with an agricultural college at the same place, because, as the report of the

Minister of Agriculture states, “the pupils of this school, being in daily contact with the first-year pupils of the college, attempted to imitate their ways, wanted more than was necessary for their social position, and at the same time aimed at a position they were unable to maintain.”

All this is in striking contrast to the spirit and method of the Danish rural high school, which started among the poorest farming class, and has grown, year by year, until it has drawn within its influence nearly all the classes in the rural community. In this school it happens that the daughters of the peasant and of the nobleman sometimes sit together on the same bench, and that the sons of the landlord and of the tenant frequently work and study side by side, sharing the personal friendship of their teacher and not infrequently the hospitality of his home.

The most striking thing about the rural high school in Denmark is that it is neither a technical nor an industrial school and, although it was created primarily for the peasant people, the subject of agriculture is almost never mentioned, at least not with the purpose of giving practical or technical education in that subject.

It may seem strange that, in a school for farmers, nothing should be said about agriculture, and I confess that it took some time for me to see the connection between this sort of school and Denmark’s agricultural prosperity. It seemed to me, as I am sure it will seem to most other persons, that the simplest and most direct way to apply education to agriculture was to teach agriculture in the schools.

The real difference between the Hungarian and the Danish methods of dealing with this problem is, however, in the spirit rather than in the form. In Hungary the purpose of the schools seems to be to give each individual such training as it is believed will fit him for the particular occupation which his station in life assigns him, and no more. The government decides. In other words, education is founded on a system of caste. If the man below learns in school to look to the man in station above him, if he begins to dream and hope for something better than the life to which he has been accustomed— then, a social and political principle is violated, and, as the Commissioner of Agriculture says, “the government is not deterred from issuing energetic orders.”

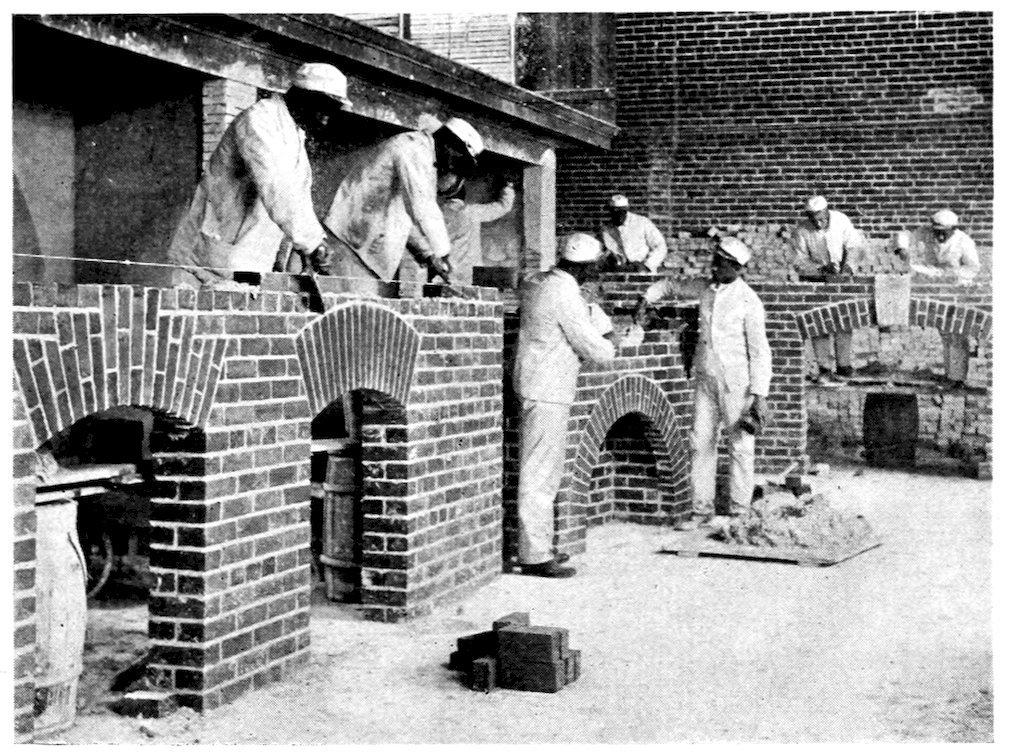

BRICKLAYING AT HAMPTON INSTITUTE

BLACKSMITHING AT HAMPTON INSTITUTE

Of course, the natural result of such measures is to increase the discontent. Just as soon as any class of people feel that privileges granted to others are denied to them, immediately these privileges— whether they be the opportunities for education, or anything else— assume in the eyes of the people to whom they are denied a new importance and value.

The result of this policy is seen in emigration statistics. I doubt, from what I have been able to learn, whether all the efforts made by the Hungarian Government in the way of agricultural instruction have done very much to allay the discontent among the masses of the farming population. Thousands of these Hungarian peasants every year still prefer to try their fortune in America, and the steady exodus of the farming population continues.

The rural high school in Denmark has pursued just the opposite policy. It has steadily sought to stimulate the ambitions and the

intellectual life of the peasant people. Instead, however, of compelling the ambitious farmer’s boy, who wants to know something about the world, to go to America, to the ordinary college, or to the city, the schools have brought the learning of the colleges and the advantages of the city to the country.

The most interesting and remarkable thing about these high schools is the success that they have had in presenting every subject that an educated man should know about in such a form as will make it intelligible and interesting to country boys and girls who have only had, perhaps, the rudiments of a common school education.

The teachers in these country high schools are genuine scholars. They have to be, for the reason that the greater part of their teaching is in the form of lectures, without text-books of any kind, and their success depends upon the skill with which they can present their subjects. In order to awaken interest and enthusiasm, they have to go to the sources for their knowledge.

Most of the teachers whom I met could speak two or three languages. I was surprised at the knowledge which every one I met in Denmark, from the King and Queen to the peasants, displayed in American affairs, and the interest they showed in the progress of the Negro and the work we have been doing at Tuskegee. As an illustration of the wide interests which occupy the teachers in these rural schools, I found one of them engaged in translating Prof. William James’s book on “Pragmatism” into the Danish language.

I have heard it said repeatedly since I was in Denmark that the Danish people as a whole were better educated and better informed than any other people in Europe. Statistics seem to bear out this statement; for, according to the immigration figures of 1900, although 24.2 per cent. of all persons over fourteen years of age coming into the United States as immigrants could neither read nor write, only .8 per cent. of the immigrants from Scandinavia were illiterate. Of the Germans, among whom I had always supposed education was more widely diffused than elsewhere in Europe, 5.8 per cent. were illiterate.

Before I go farther, perhaps, I ought to give some idea of what these rural high schools look like. One of the most famous of them is situated about an hour’s ride from Copenhagen, near the little city of Roskilde. It stands on a piece of rolling ground, overlooking a bay,

where the little fisher vessels and small seafaring craft are able to come far inland, almost to the centre of the island. All around are wide stretches of rich farm land, dotted here and there with little country villages.

There is, as I remember, one large building with a wing at either end. In one of these wings the head master of the school lives, and in the other is a gymnasium. In between are the school rooms where the lectures are held. Everything about the school is arranged in a neat and orderly manner—simple, clean, and sweet—and I was especially impressed by the wholesome, homelike atmosphere of the place. Teachers and pupils eat together at the same table and meet together in a social way in the evening. Teachers and students are thus not merely friends; they are in a certain sense comrades.

In the school at Roskilde there are usually about one hundred and fifty students. During the winter term of five months the young men are in school; in the summer the young women take their turn. Pupils pay for board and lodging twenty crowns, a little more than five dollars a month, and for tuition, twenty crowns the first month, fifteen the second, ten the third, five the fourth, and nothing the fifth. These figures are themselves an indication of the thrift as well as the simplicity with which these schools are conducted. Twenty years ago, when they were first started, I was told the pupils used to sleep together, in a great sleeping room on straw mattresses, and eat with wooden spoons out of a common dish, just as the peasant people did at that time. This reminds me that just about this same time, at Tuskegee, pupils were having similar hardships. For one thing, I recall that, in those days, the food for the whole school was cooked in one large iron kettle and that sometimes we had to skip a meal because there wasn’t anything to put in the kettle. Since that time conditions have changed, not only in the rural high schools of Denmark, but among the country people. At the present day, if not every peasant cottage, at least every coöperative dairy has its showerbath. The small farmer, who, a few years ago, looked upon every innovation with mistrust, is likely now to have his own telephone— for Denmark has more telephones to the number of the population than has any other country in Europe—and every country village has its gymnasium and its assembly hall for public lectures.

I have before me, on my desk, a school plan showing the manner in which the day is disposed of. School begins at eight o’clock in the morning and ends at seven o’clock in the evening, with two hours rest at noon. Two thirds of the time of the school is devoted to instruction in the Danish mother-tongue and in history. The rest is given to arithmetic, geography, and the natural sciences.

It is peculiar to these schools that most of the instruction is given in the form of lectures. There are no examinations and few recitations. Not only the natural sciences, but even the higher mathematics, are taught historically, by lectures. The purpose is not to give the student training in the use of these sciences, but to give him a general insight into the manner in which different problems have arisen and of the way in which the solution of them has widened and increased our knowledge of the world.

In the Danish rural high school, emphasis is put upon the folksongs, upon Danish history and the old Northern mythology. The purpose is to emphasize, in opposition to the Latin and Greek teaching of the colleges, the value of the history and the culture of the Scandinavian people; and, incidentally, to instil into the minds of the pupils the patriotic conviction that they have a place and mission of their own among the people of the world.

There are several striking things about this system of rural high schools, of which there are now 120 in Denmark. The first thing about them that impressed me was the circumstances in which they had their origin. In the beginning the rural high schools were a private undertaking, as indeed they are still, although they get a certain amount of support from the State. The whole scheme was worked out by a few courageous individuals, who were sometimes opposed, but frequently assisted by the Government. The point which I wish to emphasize is that they did not spring into existence all at once, but that they grew up slowly and are still growing. It took long years of struggles to formulate and popularize the plans and methods which are now in use in these schools. In this work the leading figure was a Lutheran bishop, Nicolai Frederick Severen Grundvig, who is often referred to as the Luther of Denmark. The rural school movement grew out of a non-sectarian religious movement and was, in fact, an attempt to revive the spiritual life of the masses of the people.

Rural high schools were established as early as 1844, but it was not until twenty years later, when Denmark, as a result of her disastrous war with Prussia, had lost one third of her richest territory, that the rural high school movement began to gain ground. It was at that time, when affairs were at their lowest ebb in Denmark, that Grundvig began preaching to the Danish people the gospel that what had been lost without, must be regained within; and that what had been lost in battle must be gained in peaceful development of the national resources.

Bishop Grundvig saw that the greatest national resource of Denmark, as it is of any country, was its common people. The schools he started and the methods of education he planned were adapted to the needs of the masses. They were an attempt to popularize learning, put it in simple language, rob it of its mystery and make it the common property of the common people.

Another thing peculiar about these schools is that they were not for children, but for older students. Eighty per cent. of the students in the rural high schools are from eighteen to twenty-five years of age; 12 per cent, are more than twenty-five years of age and only 8 per cent. are under eighteen. These schools, are, in fact, farmer’s colleges. They presuppose the education of the common school. The farmer’s son and the farmer’s daughter, before they enter the rural high school, have had the training in the public schools and have had practical schooling in the work of the farm and the home. At just about the age when a boy or a girl begins to think about leaving home and of striking out in the world for himself; just at the age when there comes, if ever, to a youth the desire to know something about the larger world and about all the mysteries and secrets that are buried away in books or handed down as traditions in the schools— just at this time the boys and girls are sent away to spend two seasons or more in a rural high school. As a rule they go, not to the school in their neighbourhood but to some other part of the country. There they make the acquaintance of other young men and women who, like themselves, have come directly from the farms, and this intercourse and acquaintance helps to give them a sense of common interest and to build up what the socialists call a “class consciousness.” All of this experience becomes important a little later in the building up of the coöperative societies, coöperative dairies,

coöperative slaughter houses, societies for the production and sale of eggs, for cattle raising and for other purposes.

The present organization of agriculture in Denmark is indirectly but still very largely due to the influence of the rural school.

The rural high school came into existence, as I have said, as the result of a religious rather than of a merely social or economic movement. Different in methods and in outward form as these high schools are from the industrial schools for the Negro in America, they have this in common, that they are non-sectarian, but in the broadest, deepest sense of that word, religious. They seek, not merely to broaden the minds, but to raise and strengthen the moral life of masses of the people. This peculiar character of the Danish rural high school was defined to me in one word by a gentleman I met in Denmark. He called them “inspirational.”

It is said of Grundvig that he was one of those who did not look for salvation merely in political freedom. In spite of this fact, the rural high schools have had a large influence upon politics in Denmark. It is due to them, although they have carefully abstained from any kind of political agitation, that Denmark, under the influence of its “Peasant Ministry,” has become the most democratic country in Europe. It is certainly a striking illustration of the result of this education that what, a comparatively few years ago, was the lowest and the most oppressed class in Denmark, namely the small farmer, has become the controlling power in the State, as seems to be the case at the present time.

I have gone to some length to describe the plans and general character of the rural high schools because they are the earliest, the most peculiar and unusual feature in Danish rural life and education, and because, although conducted in the same spirit, they are different in form and methods from the industrial schools with which I have been mainly interested during the greater part of my life.

The high schools, however, are only one part of the Danish system of rural schools. In recent years there has grown up side by side with the rural high school another type of school for the technical training in agriculture and in the household arts. For example, not more than half a mile from the rural high school which I visited at Roskilde, there has recently been erected what we in America would call an industrial school, where scientific agriculture, as well as technical

training in home-keeping are given. In this school, young men and women get much the same practical training that is given our students at Tuskegee, with the exception that this training is confined to agriculture and housekeeping. Besides, there is, in these agricultural schools, no attempt to give students a general education as is the case with the industrial schools in the South. In fact, schools like Hampton and Tuskegee are trying to do for their students at one and the same time, what is done in Denmark through two distinct types of school.

I found this school, like its neighbour the high school, admirably situated, surrounded by beautiful gardens in which the students raised their own vegetables. In the kitchen, the young women learned to prepare the meals and to set the tables. I was interested to see also that, in the whole organization of the school there was an attempt to preserve the simplicity of country life. In the furniture, for example, there was an attempt to preserve the solid simplicity and quaint artistic shapes with which the wealthier peasants of fifty or a hundred years ago furnished their homes. Dr. Robert E. Park, my companion on my trip through Europe, told me when I visited this school that he found one of the professors at work in the garden wearing the wooden shoes that used to be worn everywhere in the country by the peasant people. This man had travelled widely, had studied in Germany, where he had taken a degree in his particular specialty at one of the agricultural colleges.

Perhaps the most interesting and instructive part of my visit was the time that I spent at what is called a husmand’s or cotter’s school, located at Ringsted and founded by N. J. Nielsen-Klodskov in 1902. At this school I saw such an exhibition of vegetables, grains, and especially of apples, as I think I had never seen before, certainly not at any agricultural school.

I wish I had opportunity to describe in detail all that I saw and learned about education and the possibilities of country life in the course of my visit to this interesting school. What impressed me most with regard to it and to the others that I visited, was the way in which the different types of schools in Denmark have succeeded in working into practical harmony with one another; the way also, in which each in its separate way had united with the other to uplift, vivify, and inspire the life and work of the country people.

For example, the school at Ringsted, in addition to the winter course in farming for men and the summer school in household arts for women, offers, just as we do at Tuskegee, a short course to which the older people are invited. The courses are divided between the men and the women, the men’s course coming in the winter and the women’s course in the summer. During the period of instruction, which lasts eleven days, these older people live in the school, just as the younger students do and gain thus the benefit of an intimate association with each other and with their teachers. To illustrate to what extent this school and the others like it have reached and touched the people, I will quote from a letter written to me by the founder. He says: “The Keorehave Husmandskole (cotter’s school) is the first of its kind in Denmark. It is a private undertaking and the buildings erected since 1902 are worth about 400,000 crowns ($100,000). During the seven years in which it has been in operation 631 men and 603 women have had training for six months. In addition 3,205 men and women have attended the eleven-day courses.”

In addition to the short courses in agriculture and housekeeping, offered by the school at Ringsted, some of the rural high schools hold, every fall, great public assemblies like our Chautauquas, which last from a few days to a week and are attended by men and women of the rural districts. At these meetings there are public lectures on historical, literary and religious subjects. In the evening there are music, singing, and dancing, and other forms of amusement. These annual assemblies, held under the direction of the rural high schools, have largely taken the place of the former annual harvest-home festivals in which there was much eating and drinking, as I understand, but very little that was educational or uplifting. In addition to these yearly meetings, which draw together people from a distance, there are monthly meetings which are held either in the high school buildings, or in the village assembly buildings, or in the halls connected with the village gymnasiums. In the cities these meetings are sometimes held in the “High School Homes” as they are called, which serve the double purpose of places for the meetings of young men’s and young women’s societies and at the same time as cheap and homelike hotels for the travelling country people.

In this way the rural high schools have extended their influence to every part of the country, making the life on the farm attractive, and enabling Denmark to set before the world an example of what a simple, wholesome, and beautiful country life can be.

No doubt there are in the country life of Denmark, as of other countries, some things that cast a shadow here and there on the bright picture I have drawn. New problems always spring up out of the solution of the old ones. No matter how much has been accomplished those who know conditions best will inevitably feel that their work has just been begun. However that may be, I do not believe there will be found anywhere a better illustration of the possibilities of education than in the results achieved by the rural schools of Denmark.

One of the things that one hears a great deal of talk about in America is the relative value of cultural and vocational education. I do not think that I clearly understood until I went to Denmark what a “cultural” education was. I had gotten the idea, from what I had seen of the so-called “cultural” education in America, that culture was always associated with Greek and Latin, and that people who advocated it believed there was some mysterious, almost magical power which was to be gotten from the study of books, or from the study of something ancient and foreign, far from the common and ordinary experiences of men. I found, in Denmark, schools in which almost no text-books are used, which were more exclusively cultural than any I had ever seen or heard of.

I had gotten the impression that what we ordinarily called culture was something for the few people who are able to go to college, and that it was somehow bottled up and sealed in abstract language and in phrases which it took long years of study to master. I found in Denmark real scholars engaged in teaching ordinary country people, making it their peculiar business to strip the learning of the colleges of all that was technical and abstract and giving it, through the medium of the common speech, to the common people.

Cultural education has usually been associated in my mind with the learning of some foreign language, with learning the history and traditions of some other people. I found in Denmark a kind of education which, although as far as it went touched every subject and every land that it was the business of the educated man to know

about, sought especially to inspire an interest and enthusiasm in the art, the traditions, the language, and the history of Denmark and in the people by whom the students were surrounded. I saw that a cultural education could be and should be a kind of education that helps to awaken, enlighten, and inspire interest, enthusiasm, and faith in one’s self, in one’s race and in mankind; that it need not be, as it sometimes has been in Denmark and elsewhere, a kind of education that robs its pupils of their natural independence, makes them feel that something distant, foreign, and mysterious is better and higher than what is familiar and close at hand.

I have never been especially interested in discussing the question of the particular label that should be attached to any form of education; I have never taken much interest, for example, in discussing whether the form of education which we have been giving our students at Tuskegee was cultural, vocational, or both. I have been only interested in seeing that it was the kind that was needed by the masses of the people we were trying to reach, and that the work was done as well as possible under the circumstances. From what I have learned in Denmark, I have discovered that what has been done, for example, by Dr. R. H. Boyd in teaching the Negro people to buy Negro instead of white dolls for their children, “in order,” as Dr. Boyd says, “to teach the children to admire and respect their own type”; that what has been done at Fisk University to inspire in the Negro a love of folksongs; that what has been done at Tuskegee in our annual Negro Conferences, and in our National Business League, to awaken an interest and enthusiasm in the masses of the people for the common life and progress of the race has done more good, and, in the true sense of the word, been more cultural than all the Greek and Latin that have ever been studied by all Negroes in all the colleges in the country.