Enhanced photo-Fenton degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by 2, 5-dioxido-1, 4-benzenedicarboxylate-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) Mingyu Li

https://ebookmass.com/product/enhanced-photofenton-degradation-of-tetracycline-hydrochlorideby-2-5-dioxido-1-4-benzenedicarboxylatefunctionalized-mil-100fe-mingyu-li/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Americanist Approaches to The Book of Mormon Elizabeth Fenton

https://ebookmass.com/product/americanist-approaches-to-the-bookof-mormon-elizabeth-fenton/

5 Steps to a 5: 500 AP Physics 1 Questions to Know by Test Day, Fourth Edition Inc. Anaxos

https://ebookmass.com/product/5-steps-to-a-5-500-apphysics-1-questions-to-know-by-test-day-fourth-edition-incanaxos/

5 Steps to a 5: 500 AP Physics 2 Questions to Know by Test Day, Second Edition Christopher Bruhn

https://ebookmass.com/product/5-steps-to-a-5-500-apphysics-2-questions-to-know-by-test-day-second-editionchristopher-bruhn/

500 AP Physics 2 Questions to Know by Test Day (5 Steps to a 5), 2nd Edition Christopher Bruhn

https://ebookmass.com/product/500-ap-physics-2-questions-to-knowby-test-day-5-steps-to-a-5-2nd-edition-christopher-bruhn/

Children and the European Court of Human Rights Claire Fenton-Glynn

https://ebookmass.com/product/children-and-the-european-court-ofhuman-rights-claire-fenton-glynn/

Trapped: Brides of the Kindred Book 29 Faith Anderson

https://ebookmass.com/product/trapped-brides-of-the-kindredbook-29-faith-anderson/

Nelson English: Year 4/Primary 5: Workbook 4 Sarah Lindsay Wendy Wren

https://ebookmass.com/product/nelson-englishyear-4-primary-5-workbook-4-sarah-lindsay-wendy-wren/

Happily Ever After: Books 1 and 2 (Blossom in Winter Book 5) Melanie Martins

https://ebookmass.com/product/happily-ever-afterbooks-1-and-2-blossom-in-winter-book-5-melanie-martins/

100 Books You Must Read Before You Die [volume 2]

Multiple Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/100-books-you-must-read-before-youdie-volume-2-multiple-authors/

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envres

Enhanced photo-Fenton degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by 2, 5-dioxido-1, 4-benzenedicarboxylate-functionalized MIL-100(Fe)

Mingyu Li a, b , Yuhan Ma a, b , Jingjing Jiang a, b , Tianren Li a, b , Chongjun Zhang c , Zhonghui Han a, b , Shuangshi Dong a, b, *

a Key Laboratory of Groundwater Resources and Environment, Ministry of Education, Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, Jilin, China

b Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Water Resources and Environment, Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, Jilin, China

c Engineering Lab for Water Pollution Control and Resources Recovery of Jilin Province, School of Environment, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130117, China

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

H2DOBDC-Functionalized MIL-100(Fe)

Photo-Fenton

Contaminant removal

Degradation mechanism

ABSTRACT

Heterogeneous photo-Fenton technology has drawn tremendous attention for removal of recalcitrant pollutants. Fe-based metal-organic frameworks (Fe-MOFs) are regarded to be superior candidates in wastewater treatment technology. However, the central metal sites of the MOFs are coordinated with the linkers, which reduces active site exposure and decelerates H2O2 activation. In this study, a series of 2, 5-dioxido-1, 4-benzenedicarboxylate (H2DOBDC)-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) with enhanced degradation performance was successfully constructed via solvothermal strategy. The modified MIL-100(Fe) displayed an improvement in photo-Fenton behaviors. The photocatalytic rate constant of optimized MIL-100(Fe)-1/2/3 are 2.3, 3.6 and 4.4 times higher compared with the original MIL-100(Fe). The introduced H2DOBDC accelerates the separation and transfer in photo-induced charges and promotes Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle, thus improving the performance. •OH and •O2 are main reactive radicals in tetracycline (TCH) degradation. Dealkylation, hydroxylation, dehydration and dealdehyding are the main pathways for TCH degradation.

1. Introduction

Emerging contaminants in wastewater, such as dyes, pesticides, microplastics, pharmaceutical and personal care products, have caused severe damage to the health of the animals and humans (Cantoni et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020). Developing effective treatment technology is essential to mitigate the growing concern of water pollution. Heterogeneous Fenton, as a kind of typical advanced oxidation process, has attracted tremendous attention. However, the practical process in Fenton reaction is limited by the sluggish Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle (Liao et al., 2019; He et al., 2019a; Ren et al., 2020). An introduction of visible light is an efficient strategy to promote the production of photogenerated electrons, promote Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle and improve the degradation efficiency of pollutants (Wu et al., 2020; Ahmad et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2020). However, the rational design of efficient and durable Fenton-like photocatalysts is of great significance but remains a big challenge.

Metal-organic frameworks are regarded to be promising candidates in photo-Fenton reaction (He et al., 2019b; Hu et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2022). Compared with the semiconductor

photo-Fenton catalysts (Jiang et al., 2020; Ozores Diez et al., 2020), Fe-based MOFs (Fe-MOFs) display the superiority of their controllable topology and large surface area, which is beneficial for the regulation of structure and transfer of charge carrier (Yi et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022a; Dai et al., 2022). Besides, the non-toxicity and abundant reserves of the central iron are promising for practical applications (Jiang et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2018). Furthermore, Fe-MOFs exhibit superior visible light adsorption, which originates from both the ligand-to-metal charge transfer and Fe–O cluster charge transfer (Wu et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). The photo-generated electron is transferred from O(II) to Fe(III), leading to the acceleration of Fe(II)/Fe(III), which is critical to trigger the heterogeneous photo-Fenton reaction (Wang et al., 2022b). The charge carrier separation and migration performances could be flexibly tuned through rational introduction of functional groups in the organic linkers of MOFs (Marleny Rodriguez-Albelo et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Vermoortele et al., 2013). The charge carrier separation and migration performances could be flexibly tuned through rational introduction of functional groups in the organic linkers of MOFs. It was found that the introduction of –Br and –NO2 in terephthalic acid was beneficial for the

* Corresponding author. Key Laboratory of Groundwater Resources and Environment, Ministry of Education, Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, Jilin, China. E-mail address: dongshuangshi@gmail.com (S. Dong).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113399

Received 22 January 2022; Received in revised form 23 April 2022; Accepted 28 April 2022

Availableonline10May2022

0013-9351/©2022ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

improved Fenton activity of MIL-88B(Fe) (Gao et al., 2020). The reduced electron density of central iron with the electro-withdrawing substituent was conductive to the acceleration of Fe(II)/Fe(III), thus leading to an enhanced Fenton performance. Amino-grafted MOFs were also demonstrated as superior candidate in photo-Fenton system. The photo-induced electron generated by –NH2 and Fe–O excitation promoted the Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle and the •OH production (Liu et al., 2022). Moreover, –OH could also work as intramolecular hole scavenger in hydroxyl modified UiO-66 to promote Cr(VI) reduction (Shi et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021). The addition of desirable molecules to the MOF system could also facilitate the charge transfer and increase the stability. It was demonstrated the introduction of anthraquinone in zirconium MOFs resulted in acceleration of charge transfer (Liu and Thoi, 2020). Besides, the involved benzothiadiazole in Co-doped MOF also promoted separation and migration of photo-induced charge carriers (Lv et al., 2020). Moreover, the coordination of the phenolic-inspired lipid molecule with central metal could improve the water resistance and stability (Zhu et al., 2018). However, little research has been explored by guest molecule functionalization of Fe-MOFs for the enhancement of photo-Fenton performance. Besides, the relationship between the structure regulation and photo-Fenton performance has not been considered.

Herein, a series of 2, 5-dioxido-1, 4-benzenedicarboxylate (H2DOBDC)-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) was successfully constructed via solvothermal strategy. The photo-Fenton property was explored by removal of tetracycline (TCH) and carbamazepine (CBZ). The regulation of the structure and the performance of photo-Fenton degradation efficiency were investigated to explore the relationship between the structure and performance. The reactive oxidation species (ROS) participated in photo-Fenton process were clarified by electron spin resonance (ESR) technique and radical scavenger experiments. Liquid chromatographymass spectrometry (LC-MS) equipment and quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) were applied to evaluate the main pathways and product toxicity assessment for TCH degradation, respectively.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and ferric chloride hexahydrate

(FeCl3•6H2O) were ordered in Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. H2DOBDC was ordered in Jilin CAS-Yanshen Technology Co., Ltd. 1, 3, 5-Tricarboxybenzene (H3BTC) was bought from Aladdin. Deionized water was used during the experiments with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ using a Millipore Direct-Q System.

2.2. Synthesis of the Fe-MOFs

2.2.1. Construction of MIL-100(Fe)

A one-pot solvothermal strategy was applied for the synthesis of MIL100(Fe) as described previously (Ahmad et al., 2019). 675 mg of FeCl3•6H2O (2.5 mM) and 525 mg of H3BTC (2.5 mM) were dissolved in DMF with a volume of 50 mL, which was then heated in Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave at 150 ◦ C for 12 h. The as-prepared precipitate was then centrifuged by DMF and ethanol for many times after cooling down to room temperature. Finally, the MIL-100(Fe) powder was synthesized after dried at 80 ◦ C overnight.

2.2.2. Construction of H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe)

H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) was constructed via similar process as mentioned above, except that 99 mg, 297 mg and 495 mg of H2DOBDC was solved into the solution of FeCl3•6H2O and H3BTC (Mei et al., 2017). The as-made catalysts were named to be MIL-100 (Fe)-1/2/3, separately.

2.3. Characterization

Microstructures and morphologies of the catalysts were observed via emission-scanning electron microscopy (XL30 FEG). A D8 Advance Xray diffractometer was applied for the collection of powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping was carried out in Oxford instruments X-MAX. A VERTEX 70 FTIR Spectrometric Analyzer was applied to obtain the Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. An Al Kα radiation excitation source ((h = 1486.6 eV, Thermo ESCALAB 250) was used to measure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra. The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were collected at 77 K via an ASAP 2020 physisorption analyzer. The calculation of the specific surface area was by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. Persee TU-1901 spectrometer was applied to measure UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS). The

Fig. 2. (a) XRD patterns, (b) FT-IR spectra (c) Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms (d) XPS survey spectra of the original MIL-100(Fe) and modified MIL-100 (Fe)-1/2/3.

photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded on Edinburgh instruments FS5 fluorescence spectrophotometer at 320 nm excitation. A Bruker EMX/Plus spectrometer was applied to measure ESR spectra with a dual-mode cavity. Leaching of the iron ions was monitored with atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Shimadzu AA-6000CF).

2.4. Degradation experiments

The as-obtained catalysts were applied for the removal of CBZ and TCH in photo-Fenton system. 2 mg of original MIL-100(Fe) and modified MIL-100(Fe)-1/2/3 was added into TCH solution (20 mL, 50 ppm) for a typical degradation procedure. The suspension was mixed well for 30 min without light irradiation. After that, 25 mM of H2O2 was dropped to the suspension. Next, the solution was irradiated with the Xenon lamp, and the ultraviolet light was filtered by a cut-off filter of 420 nm. Equivalent samples were taken every 2 min by a syringe and filtrated through 0.22 μm membrane to remove the catalyst. The amount of the contaminant was obtained with a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260) and UV–vis (TU-1901). Tert-butanol (tBuOH, 300 mM), Formic acid (FA, 10 mM), L-histine (L-his,10 mM), 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidine (TEMP, 1 mM) and KBrO3 (20 mM) were used to capture •OH, h+ , 1O2, •O2 and electron, respectively. The scavenger experiments were carried out by similar procedures, except for the addition of radical capture agent after adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Moreover, the ESR measurements with TEMP or 5,5dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) were performed to investigate the main active radicals involved in photo-Fenton reaction.

2.5. Electrochemical measurements

A CHI660C electrochemical workstation was applied to achieve the photocurrent and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests. A standard three-electrode system was used in a 0.2 M Na2SO4 electrolyte by using Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode, sample-coated FTO plate as a working electrode and Pt sheet as a counter electrode. The EIS measurements were operated with a frequency varying between 10 1 and 105 I-t curves were acquired on the open voltage potential using a UVlight cut-off filter equipped Xenon lamp.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterizations

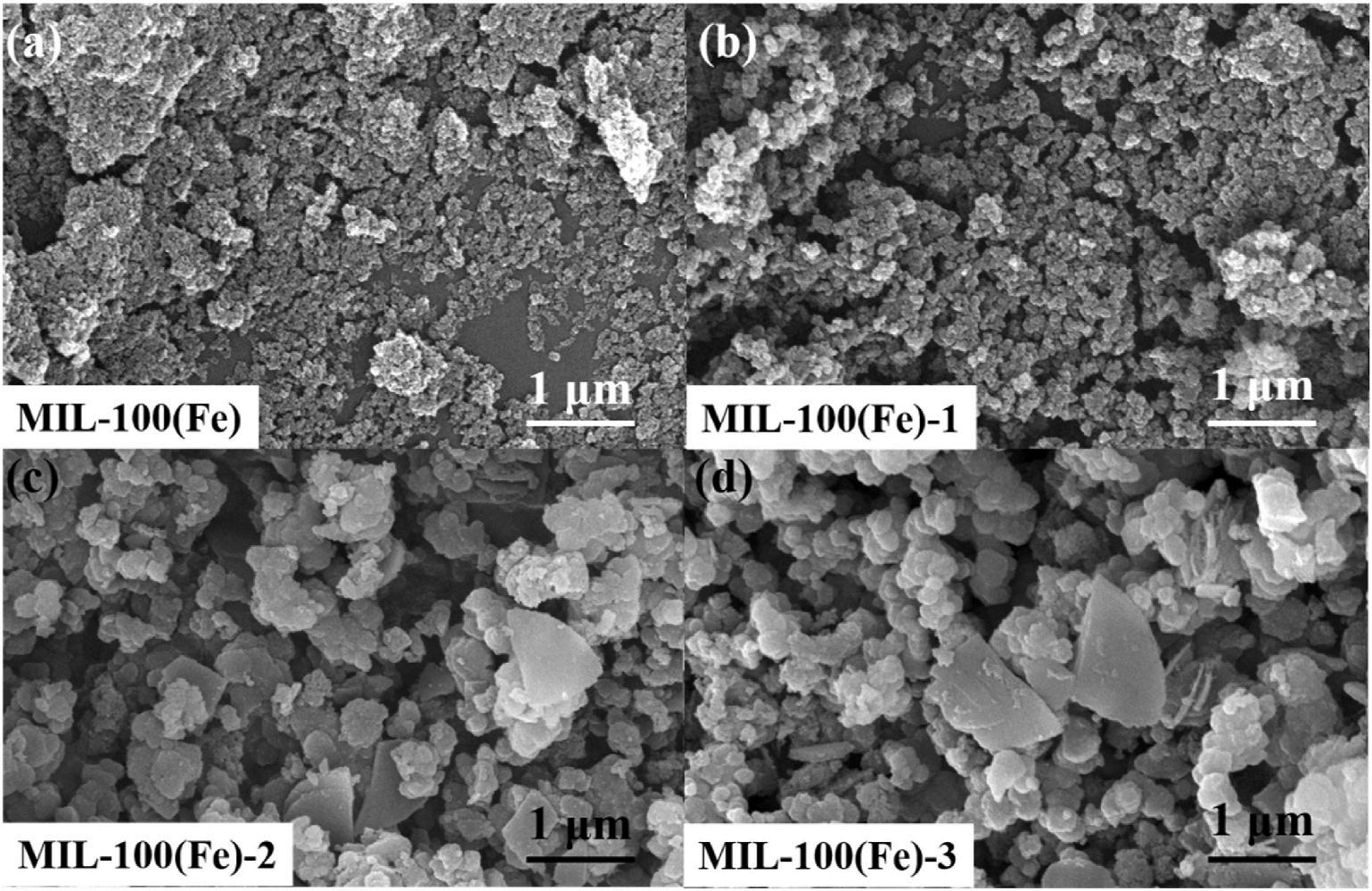

A particle-like architecture with a diameter of ca 29 nm was observed in the as-prepared MIL-100(Fe) (Fig. 1). The respective EDS elemental results in the as-prepared MIL-100(Fe) reveal that Fe, Cl, O and C species are existed (Figure S1). Chloride ions tend to coordinate with unsaturated iron sites in the framework, and the result are in accordance with the reported literature (Wu et al., 2020). After the introduction of H2DOBDC, the diameter of MIL-100(Fe)-1 varies from ca. 40 nm–72 nm (Figure S2). Except for the particle-like structure, shape-like structure appears at MIL-100(Fe)-2/3. An average diameter varies from ca 180 nm and ca 190 nm was obtained, respectively. It is obvious that the introduction of H2DOBDC could effectively control MIL-100(Fe) morphology by modulating its growth, and the size distribution is broadened with the increased amount of H2DOBDC. Moreover, EDS mapping results in H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) demonstrate the uniform distribution of C, O and Fe elements

Fig. 3. High-resolution XPS (a) C1s, (b) O 1s and (c) Fe 2p spectra in MIL-100(Fe) and MIL-100(Fe)-1/2/3.

(Figure S3).

X-ray power diffraction (XRD) characterizations were executed for clarifying crystal structure in the Fe-MOFs (Fig. 2a). Typical

characteristic diffraction peaks are existed in original and modified FeMOFs, and the patterns are similar to the ones reported elsewhere, indicating the successful synthesis of the basic structure (Zhong et al.,

Fig. 5. (a) Leached iron after equilibrium and degradation process; (b) The stability test and the leached iron in each cycle; (c–d) XRD patterns and XPS spectra before and after stability test in MIL-100(Fe)-1.

2020). With the increase of H2DOBDC content, additional small peaks appear in MIL-100(Fe)-2/3. The slight change in peak character is originated from the difference in crystal selective growth with an addition of H2DOBDC, which matches with SEM images in Fig. 1 It could also be seen that the crystallinity of MIL-100(Fe) decreased with the increase in amount of H2DOBDC. Similar results were observed in other reported MOFs (Zheng et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019). However, the main peaks of H2DOBDC-grafted MIL-100(Fe) are in agreement with the original one, which indicates an introduction of H2DOBDC has little influence to the whole crystal structure of MIL-100 (Fe).

It could also be noted the bands located at 1720, 700 and 460 cm 1 belong to stretching vibration of C–– O in –COOH groups, C–H bending vibrations in benzene ring and Fe–O stretching vibration in the FT-IR spectra, separately (Fig. 2b). The band from 1660 cm 1 to 1360 cm 1 belongs to skeleton vibration in benzene. Typical peaks in FT-IR spectra of MIL-100(Fe)-1/2/3 match with MIL-100(Fe), which results from similar absorption peaks of the grafted-H2DOBDC and H3BTC linker. N2 physisorption was measured to explore the specific area of the samples (Fig. 2c). All curves are the typical type-IV isotherms, which demonstrates the existence of mesoporous structure. Besides, the incorporation of H2DOBDC could decrease the specific surface area of MIL-100(Fe) (Table S1). The reduced surface area might be attributed to that the functionalized H2DOBDC molecules block the pores of the MIL-100(Fe)1 with structural collapse, thus leading to a decline of surface area (Mei et al., 2017).

XPS spectra were collected to acquire the composition and chemical states of the catalysts. The XPS survey spectra demonstrate the composition of Fe, C and O, which matches with that of the EDS analysis (Fig. 2d). The high-resolution XPS spectra in C1s are fitted with C–H/ C–– C and C–– O in the linkers, separately (Fig. 3a). As for O 1s spectra in Fig. 3b, two deconvoluted peaks at 531.4 and 532.6 eV are in

correspondence with the carboxylic groups in linkers and Fe–O in Fe3μ3-oxo cluster. Fe 2p spectra show two deconvoluted peaks at a binding energy of 711.7 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and 725.1 eV (Fe 2p1/2), separately (Fig. 3c). The distance of these two peaks is 13.4 eV, which matches well with α-Fe2O3 (Wu et al., 2020; He et al., 2019b). The XPS results further demonstrate the valence of Fe in as-prepared MIL-100(Fe) is trivalent.

3.2. Photo-Fenton performance

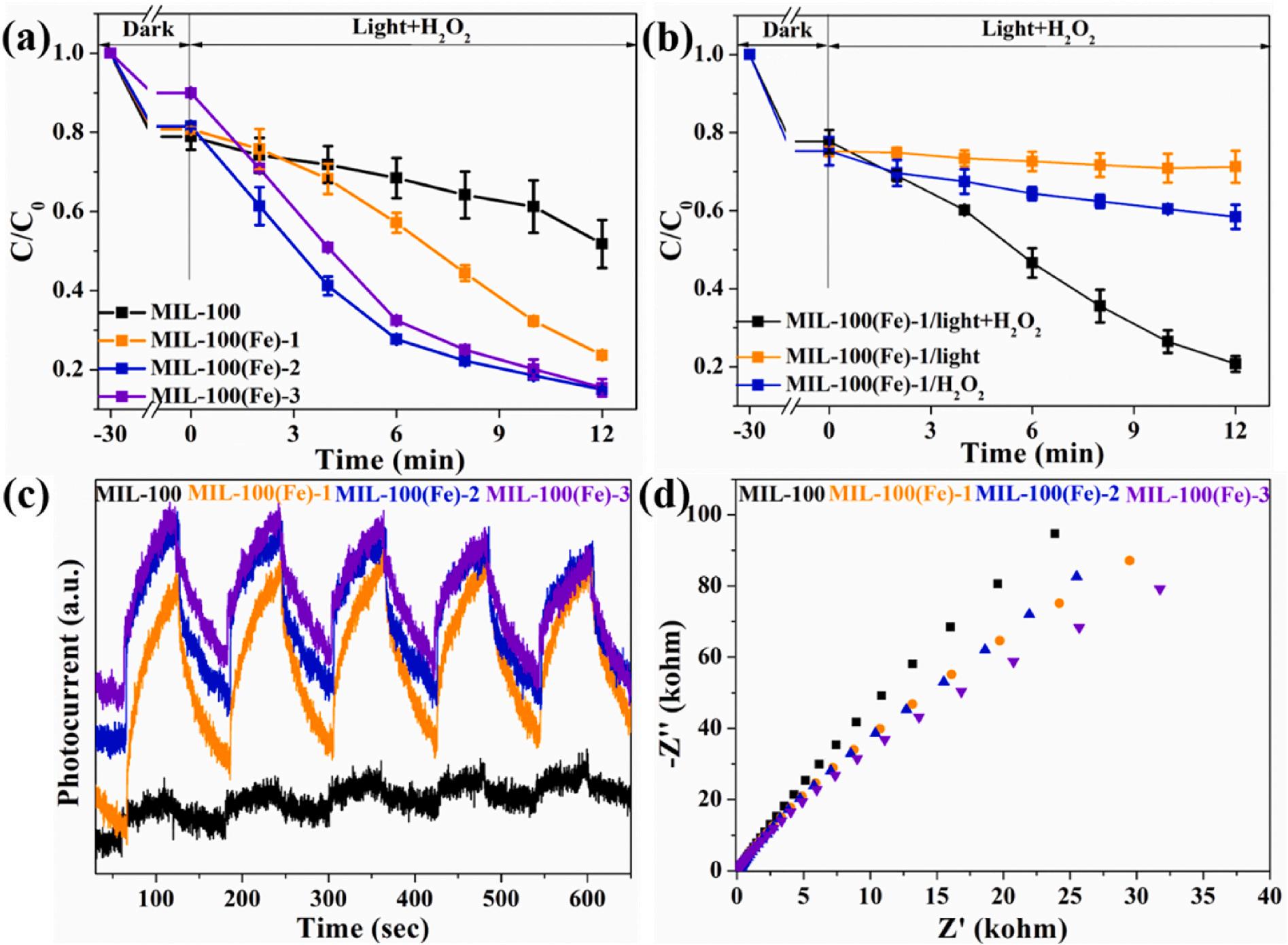

TCH removal experiments were measured to explore the photoFenton degradation property for as-made catalysts. The adsorption/ desorption equilibrium could be achieved in 30 min for all samples (Figure S4). The adsorption performance decreases with the increase of the H2DOBDC, which matches well with the results in specific surface area. The photo-Fenton efficiencies for TCH degradation were 48.2%, 76.3%, 85.0%, and 84.6% in original MIL-100(Fe) and modified MIL100(Fe)-1/2/3 within 12 min, respectively. The corresponding degradation rate constants for MIL-100(Fe)-3/2/1 and MIL-100(Fe) are 0.17062 min 1 , 0.14456 min 1 , 0.10379 min 1 and 0.03139 min 1 , separately (Fig. 4a–S5). The degradation experiment with visible light or H2O2 only was also carried out to clarify the synergistic effects between photocatalysis and Fenton reaction. The degradation efficiencies were 22.1%, 42.9% and 79.2% for photocatalysis, Fenton and photo-Fenton reaction in 12 min (Fig. 4b). This demonstrates that the involvement of visible light accelerates the oxidation reaction of TCH in heterogeneous Fenton process. The modified MIL-100(Fe) also exhibits enhanced photo-Fenton performance in CBZ degradation (Figure S6).

PL measurements were applied to clarify the effectiveness of photoinduced carrier separation (Figure S7). It could be seen that MIL-100 (Fe)-1 shows much lower PL intensity than that in pristine MIL-100 (Fe), indicating that an introduced H2DOBDC is in favor for the separation of charge carrier and the enhancement of photocatalytic

Fig. 6. (a) ROS scavenger experiments in photo-Fenton TCH degradation for MIL-100(Fe)-1. (b–d) ESR spectra of MIL-100(Fe) and MIL-100(Fe)-1 in photo-Fenton system (b) •OH-DMPO in water (c) •O2 -DMPO in methanol (d) 1O2-TEMP in water.

efficiency.

The photocurrent measurements were executed to clarify the migration abilities of photo-induced charge carrier. (Fig. 4c). MIL-100 (Fe)-1/2/3 shows increased photocurrent intensity than MIL-100(Fe) with a grafting of H2DOBDC. MIL-100(Fe)-1 shows ca 16 times higher in transient photocurrent response (TPR) intensity than that of MIL-100 (Fe) during several on-off cycles in visible-light illumination. An enhancement of photocurrent signal reveals an acceleration of the photo-induced charge transfer after the functionalization of H2DOBDC (Li et al., 2021). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots also demonstrate the enhanced charge transfer performance in H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe)-1/2/3 (Fig. 4d).

3.3. Reusability and stability of H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe)

The reusability and stability of the MIL-100(Fe)-1 was clarified by measurement of the concentration of leached iron ions. After adsorption-desorption equilibrium, the concentrations of leached iron for MIL-100(Fe)/-1/2/3 in reaction liquor were 0.13, 0.15, 0.15 and 0.23 mg L 1 , separately, which demonstrates the stability of original and modified MIL-100(Fe). However, the stability dramatically decreases with an increased amount of H2DOBDC ratio in H2DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe), and the concentration of leached iron reaches 5.06 mg L 1 in MIL-100(Fe)-3 (Fig. 5a). Fig. 5b shows that there is no significant decrease in efficiency over 3 cycles for MIL-100(Fe)-1. Besides, XRD and XPS results in the MIL-100(Fe)-1 reveal the negligible change after 3 cycles (Fig. 5c and d). SEM images and EDS mapping results could further confirm the superior stability of MIL-100(Fe)-1, as the iron content shows negligible changes varying from 16.75 wt% to 15.73 wt%

(Figure S8).

3.4.

Degradation mechanism in photo-Fenton reaction

Scavenger experiments were carried out to explore the ROSs involved in photo-Fenton reaction (Fig. 6a). The degradation performance decreases after the addition of t-BuOH, TEMP, FA and L-his, which demonstrates the participation of •OH, •O2 , h+ and 1O2 in photoFenton process. ESR measurements were further carried out to explore the ROSs involved in different systems. The ESR results show that the DMPO-•OH, DMPO-•O2 and TEMP-1O2 adduct signals could be observed in MIL-100(Fe) and MIL-100(Fe)-1 after visible light irradiation, and the ROS intensity were further enhanced with the introduction of H2O2 (Fig. 6b–d). The photo-induced electron generated by Fe–O excitation and separated by the hole scavenger promoted the Fe(II)/Fe (III) cycle, Therefore, the amount of produced reactive oxidation species was enhanced in H2DOBDC modified MIL-100(Fe) consequently (Figure S9). The modified MIL-100(Fe)-1 shows a obviously stronger ROS intensity than original MIL-100(Fe), indicating its enhancement in photo-Fenton reactivity.

The original MIL-100(Fe) exhibits the same valence band potential (EVB) edges of 2.73 eV with modified MIL-100(Fe)-1 according to VBXPS spectra results. Besides, the valence band potential (ECB) values were identified as 0.17 and 0.23V vs. Ag/AgCl by Mott-Schottky measurements in pristine MIL-100(Fe) and modified MIL-100(Fe)-1 (Figure S10). As a result of the ROSs scavenger experiments, ESR results and the band position analysis, the reactive species in MIL-100(Fe)1 are produced by the following steps:

Fe3+ +H2 O2 → Fe2+ +HO2 +H+ (1)

Fe2+ +H2 O2 → Fe3+ + ⋅OH + OH

100(Fe) 1 + hv → h+ + e

e + Fe3+ → Fe2+

HO2 ⋅ ↔ ⋅O2 + H+

⋅OH +H2 O2 → HOO + H2 O

HOO + HOO → 1 O2 + H2 O2

OH + ⋅O2 + 1 O2 + TCH→ Degraded products (8)

It could be inferred that the reactive •O2 could not be produced by photogenerated electron reduction of oxygen. The reason is both MIL100(Fe) and the modified MIL-100(Fe)-1 exhibit higher oxidation and reduction potentials than redox potentials in O2/•O2 with the value of 0.33 eV vs. NHE) and •OH/OH with the value of 2.38 eV vs. NHE, respectively. Reactive •O2 could not be produced by photogenerated electron reduction of oxygen. Therefore, the active species of •O2 and 1O2 could only be generated by the conversion of •OH (eqs. 1-2 and 5-7).

The introduction of visible light accelerates the generation and transfer of photoinduced electron from O(II) to Fe(III). The produced Fe(II) reduced by Fe(III) initiates Fenton reaction, which further promotes the oxidation of contaminants (eqs. (3) and (4)). Since MIL-100(Fe) exhibits similar valence band positions with MIL-100(Fe)-1, so the enhancement of degradation efficiency results from the promotion of Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle, and the transfer and separation of photo-induced charge carrier after the H2DOBDC modification.

3.5. Degradation pathways and toxicity assessment

The TCH and its degradation products were identified by LC-MS

measurement (Figure S11), and possible degradation pathways were shown in Figure S12. P2 (m/z = 436) and P3 (m/z = 428) were obtained by dealkylation and hydroxylation reaction of TCH (m/z = 445) (Yu et al., 2020). Through the reaction of deamination and dealkylation, P4 and P5 with m/z = 397 and m/z = 414 could be achieved. An intermediates of P6 (m/z = 319) and P7 (m/z = 296) were also observed by dehydration (Liu et al., 2021), alcohol oxidation and deamination of P4 and P5. P8 and P9 with the m/z value of 264 and 256 were produced by the dealkylation and dealdehyding reaction (Guo et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2019). Further degradation of P8 and P9 by dealkylation and dehydration resulted in the production of P10 (m/z = 249), P11 (m/z = 234) and P12 (m/z = 217). Furthermore, all intermediates will be degraded into smaller molecules, CO2, and H2O (Li et al., 2020).

The Toxicity Estimation Software Tool was applied to evaluate the acute toxicity, bioaccumulation factor and developmental toxicity of TCH and corresponding intermediates by QSAR predication (Sun et al., 2021). Two methods were used to evaluate the actual toxicities, i.e., the LC50 of fathead minnow (half lethal dose for the intermediates to fathead minnow after 96 h) and daphnia magna (half lethal dose of the intermediates to daphnia magna after 48 h). According to biological resistance to contaminants, the acute toxicity is classified to be “very toxic” , “toxic” , “harmful” and “not harmful” , respectively (Fig. 7a and b). It could be seen that the values of most LC50 are higher in intermediates compared with the TCH for fathead minnow. In daphnia magna, equivalent intermediates show increased/decreased toxicity. The developmental toxicity and bioaccumulation factor were also evaluated. The results show that most of the intermediates show lower developmental toxicity and higher bioaccumulation factor than that of the original TCH (Fig. 7c and d). These findings reveal that TCH could be effectively degraded to low toxic products.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have designed H2DOBDC modified MIL-100(Fe) via

a solvothermal route. The photocatalytic rate constant of MIL-100(Fe)3/2/1 is increased by 4.4, 3.6 and 2.3 times in contrast to the original MIL-100(Fe), separately. The enhanced degradation performance is attributed to an improvement in Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle and an improvement of separation and migration of photo-induced charges. Besides, MIL-100(Fe)-1 exhibits superior stability and reusability with less iron ion leaching. This work paves a novel pathway for effective synthesis of modified-MOFs, it will also provide theoretical basis in MOF-based catalysts for contaminant removal field.

Author contributions

Mingyu Li: Data curation, writing - original draft. Yuhan Ma: Methodology, conceptualization. Jingjing Jiang: Resources, investigation. Tianren Li: Validation. Chongjun Zhang: Software. Zhonghui Han: Writing - review & editing. Shuangshi Dong: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52100087, 52170079), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (cstc2021jcyj-msxmX1032, cstc2021jcyjmsxmX0954), and the Programme of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B16020), China.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113399

References

Ahmad, M., Chen, S., Ye, F., et al., 2019. Efficient photo-Fenton activity in mesoporous MIL-100(Fe) decorated with ZnO nanosphere for pollutants degradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 245, 428–438

Ahmad, M., Quan, X., Chen, S., et al., 2020. Tuning Lewis acidity of MIL-88B-Fe with mix-valence coordinatively unsaturated iron centers on ultrathin Ti3C2 nanosheets for efficient photo-Fenton reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 264, 118534. Cantoni, B., Penserini, L., Vries, D., et al., 2021. Development of a quantitative chemical risk assessment (QCRA) procedure for contaminants of emerging concern in drinking water supply. J. Water Res. 194, 116911

Cao, H.-L., Cai, F.-Y., Yu, K., et al., 2019. Photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline antibiotics over CdS/nitrogen-doped–carbon composites derived from in situ carbonization of metal–organic frameworks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 10847–10854

Dai, Y., Yao, Y., Li, M., et al., 2022. Carbon nanotube filter functionalized with MIL-101 (Fe) for enhanced flow-through electro-Fenton. Environ. Res. 204, 112117

Fan, J., Chen, D., Li, N., et al., 2018. Adsorption and biodegradation of dye in wastewater with Fe3O4@MIL-100 (Fe) core–shell bio-nanocomposites. Chemosphere 191, 315–323

Gao, C., Su, Y., Quan, X., et al., 2020. Electronic modulation of iron-bearing heterogeneous catalysts to accelerate Fe(III)/Fe(II) redox cycle for highly efficient Fenton-like catalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 276, 119016

Guo, F., Huang, X., Chen, Z., et al., 2020. Prominent co-catalytic effect of CoP nanoparticles anchored on high-crystalline g-C3N4 nanosheets for enhanced visiblelight photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 395, 125118

He, D., Niu, H., He, S., et al., 2019a. Strengthened Fenton degradation of phenol catalyzed by core/shell Fe-Pd@C nanocomposites derived from mechanochemically synthesized Fe-metal organic frameworks. Water Res. 162, 151–160

He, L., Dong, Y., Zheng, Y., et al., 2019b. A novel magnetic MIL-101(Fe)/TiO2 composite for photo degradation of tetracycline under solar light. J. Hazard Mater. 361, 85–94. Hu, H., Zhang, H., Chen, Y., et al., 2019. Enhanced photocatalysis degradation of organophosphorus flame retardant using MIL-101(Fe)/persulfate: effect of irradiation wavelength and real water matrixes. Chem. Eng. J. 368, 273–284

Huang, Y., Kong, M.H., Coffin, S., et al., 2020. Degradation of contaminants of emerging concern by UV/H2O2 for water reuse: kinetics, mechanisms, and cytotoxicity analysis. Water Res. 174, 115587

Jiang, D., Zhu, Y., Chen, M., et al., 2019. Modified crystal structure and improved photocatalytic activity of MIL-53 via inorganic acid modulator. J. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 255, 117746

Jiang, J., Wang, X., Liu, Y., et al., 2020. Photo-Fenton degradation of emerging pollutants over Fe-POM nanoparticle/porous and ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheet with rich nitrogen defect: degradation mechanism, pathways, and products toxicity assessment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 278, 119349

Li, H., Sun, S., Ji, H., et al., 2020. Enhanced activation of molecular oxygen and degradation of tetracycline over Cu-S-4 atomic clusters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 272, 118966

Li, Y.-H., Yi, X.-H., Li, Y.-X., et al., 2021. Robust Cr(VI) reduction over hydroxyl modified UiO-66 photocatalyst constructed from mixed ligands: performances and mechanism insight with or without tartaric acid. Environ. Res. 201, 111596

Liao, X., Wang, F., Wang, F., et al., 2019. Synthesis of (100) surface oriented MIL-88A-Fe with rod-like structure and its enhanced Fenton-like performance for phenol removal. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 259, 118064

Liu, B., Thoi, V.S., 2020. Improving charge transfer in metal-organic frameworks through open site functionalization and porosity selection for Li-S batteries. Chem. Mater. 32, 8450–8459

Liu, L., Chen, Z., Wang, J., et al., 2019. Imaging defects and their evolution in a metal–organic framework at sub-unit-cell resolution. Nat. Chem. 11, 622–628

Liu, F., Cao, J., Yang, Z., et al., 2021. Heterogeneous activation of peroxymonosulfate by cobalt-doped MIL-53(Al) for efficient tetracycline degradation in water: coexistence of radical and non-radical reactions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 581, 195–204

Liu, H., Yin, H., Yu, X., et al., 2022. Amino-functionalized MIL-88B as heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalysts for enhancing tris-(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP) degradation: dual excitation pathways accelerate the conversion of Fe-III to Fe-II under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard Mater. 425, 127782

Lv, S.-W., Liu, J.-M., Zhao, N., et al., 2020. Benzothiadiazole functionalized Co-doped MIL-53-NH2 with electron deficient units for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of bisphenol A and ofloxacin under visible light. J. Hazard Mater. 387, 122011

Marleny Rodriguez-Albelo, L., Lopez-Maya, E., Hamad, S., et al., 2017. Selective sulfur dioxide adsorption on crystal defect sites on an isoreticular metal organic framework series. Nat. Commun. 8, 14457

Mei, L., Jiang, T., Zhou, X., et al., 2017. A novel DOBDC-functionalized MIL-100(Fe) and its enhanced CO2 capacity and selectivity. Chem. Eng. J. 321, 600–607

Ozores Diez, P., Giannakis, S., Rodriguez-Chueca, J., et al., 2020. Enhancing solar disinfection (SODIS) with the photo-Fenton or the Fe2+/peroxymonosulfateactivation process in large-scale plastic bottles leads to toxicologically safe drinking water. J. Water Res. 186, 116387

Ren, Y., Shi, M., Zhang, W., et al., 2020. Enhancing the Fenton-like catalytic activity of nFe2O3 by MIL-53(Cu) support: a mechanistic investigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5258–5267

Shi, L., Wang, T., Zhang, H.B., et al., 2015. An amine-functionalized iron(III) metalorganic framework as efficient visible-light photocatalyst for Cr(VI) reduction. Adv. Sci. 2, 1500006

Sun, X., He, W., Yang, T., et al., 2021. Ternary TiO2/WO3/CQDs nanocomposites for enhanced photocatalytic mineralization of aqueous cephalexin: degradation mechanism and toxicity evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 412, 128679

Vermoortele, F., Bueken, B., Le Bars, G., et al., 2013. Synthesis modulation as a tool to increase the catalytic activity of metal–organic frameworks: the unique case of UiO66(Zr). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11465–11468

Wang, J.-S., Yi, X.-H., Xu, X., et al., 2022a. Eliminating tetracycline antibiotics matrix via photoactivated sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation process over the immobilized MIL-88A: batch and continuous experiments, 431, 133213

Wang, F.-X., Wang, C.-C., Du, X., et al., 2022b. Efficient removal of emerging organic contaminants via photo-Fenton process over micron-sized Fe-MOF sheet. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 132495

Wu, Q., Yang, H., Kang, L., et al., 2020. Fe-based metal-organic frameworks as Fentonlike catalysts for highly efficient degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride over a wide pH range: acceleration of Fe(II)/Fe(III) cycle under visible light irradiation. J. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 263, 118282.

Yang, L., Zhao, T., Boldog, I., et al., 2019. Benzoic acid as a selector-modulator in the synthesis of MIL-88B(Cr) and nano-MIL-101(Cr). Dalton Trans. 48, 989–996

Ye, Z., Padilla, J.A., Xuriguera, E., et al., 2020. Magnetic MIL(Fe)-type MOF-derived Ndoped nano-ZVI@C rods as heterogeneous catalyst for the electro-Fenton degradation of gemfibrozil in a complex aqueous matrix. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 266, 118604

Yi, X.-H., Ji, H., Wang, C.-C., et al., 2021. Photocatalysis-activated SR-AOP over PDINH/ MIL-88A(Fe) composites for boosted chloroquine phosphate degradation: performance, mechanism, pathway and DFT calculations. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 293, 120229

Yu, J., Cao, J., Yang, Z., et al., 2020. One-step synthesis of Mn-doped MIL-53(Fe) for synergistically enhanced generation of sulfate radicals towards tetracycline degradation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 580, 470–479

Zhao, T., Yang, L., Feng, P., et al., 2018. Facile synthesis of nano-sized MIL-101(Cr) with the addition of acetic acid. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 471, 440–445

Zhao, F., Liu, Y., Hammouda, S.B., et al., 2020. MIL-101(Fe)/g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalysis toward simultaneous reduction of Cr(VI) and oxidation of bisphenol A in aqueous media. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 272, 119033

Zheng, X., Qi, S., Cao, Y., et al., 2021. Morphology evolution of acetic acid-modulated MIL-53(Fe) for efficient selective oxidation of H2S. Chin. J. Catal. 42, 279–287

Zhong, Z., Li, M., Fu, J., et al., 2020. Construction of Cu-bridged Cu2O/MIL(Fe/Cu) catalyst with enhanced interfacial contact for the synergistic photo-Fenton degradation of thiacloprid. Chem. Eng. J. 395, 125184

Zhu, W., Xiang, G., Shang, J., et al., 2018. Versatile surface functionalization of metalorganic frameworks through direct metal coordination with a phenolic lipid enables diverse applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1705274

Zhu, C., He, Q., Yao, H., et al., 2022. Amino-functionalized NH2- MIL-125(Ti)-decorated hierarchical flowerlike ZnIn2S4 for boosted visible-light photocatalytic degradation. J. Environ. Res. 204, 112368

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

The

Project Gutenberg eBook of Music after the great war, and other studies

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Music after the great war, and other studies

Author: Carl Van Vechten

Release date: May 21, 2024 [eBook #73668]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: G. Schirmer, 1915

Credits: Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries) *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MUSIC AFTER THE GREAT WAR, AND OTHER STUDIES ***