ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

WATSON’S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has been several years in the making, and I would like to acknowledge the support and contributions of the many persons who helped this project come to fruition. First, I would like to thank Kit Wellman and Lucy Randall for their guidance and support as editors. Jessica Flanigan is also owed a huge thank you for being a pleasure to work with, as well as a gracious and generous interlocutor. The anonymous referee for the original manuscript made important and substantive suggestions for improvement, and I am deeply grateful for the referee’s comments.

Christie Hartley and Susan Brison each read the entire manuscript; their comments and contributions improved the final manuscript immeasurably. Melissa Farley provided generous feedback on chapter 3, which improved it greatly. The support and encouragement from Catharine MacKinnon in this project and all my work is a gift that I am so fortunate to receive. I am incredibly lucky to have

a philosophical community full of friendship and inspiration. The following persons have offered their care and support to me over the years, including through the writing of this book, and their work inspires me to be a better philosopher: Elizabeth Barnes, Remy Debes, Robin Dembroff, Clare Chambers, John Christman, John Corvino, Liz Goodnick, Lori Gruen, Sarah Clark Miller, Cindy Stark, and Helga Varden.

While working on this book, I was fortunate enough to present versions of various arguments to generous audiences and hone the arguments in light of their feedback. I would like to thank the hosts and the audience members at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, Georgia State University, Georgetown University, University of Kentucky, University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee, Dartmouth College, New York Society for Women in Philosophy, Society for Analytical Feminism, San Diego State University, the Eastern and Central Divisions of the American Philosophical Association, California State, Los Angeles, and Trinity College.

The support of the University of San Diego, through research grants, helped create the time to finish this project. My colleagues offer continuous and generous support and make my daily life richer through their friendship. And, finally, the constant companionship of Grace, my sweet, sweet dog, made long days of researching and writing this book more bearable through her gentle nudging to stop working in order to play.

Flanigan’s Acknowledgments

Debates about sex work and public policy raise challenging questions about identity, economic justice, political authority, and consent. It is often easy for people who disagree about these questions to talk past each other or to fail to engage with the other side. It is for this reason that I am especially grateful to Lori Watson, who has consistently been a charitable and open-minded interlocutor. I learned a great deal from reading her contribution and from our conversations about the ethics of sex work. I am also grateful to Kit Wellman and Lucy Randall for their guidance and support as editors. In addition, an anonymous referee for the original manuscript provided extensive comments that truly went above and beyond what any author can reasonably expect, for which I am very thankful.

My thinking about this topic benefited from many conversations with Javier Hidalgo, who encouraged me to think more about this topic and provided helpful written comments on a draft of the manuscript. I would also like to thank my colleagues in the Ethics Working Group at the University of Richmond, Ryan Davis, and Matt Zwolinski, who suggested that Lori and I work together on this project. In addition, opportunities to discuss this work in two public debates with Lori improved the manuscript substantially. I would like to thank Andrew I. Cohen for organizing our first debate at Georgia State University and John Alcorn for hosting our second debate at Trinity College and for providing extremely helpful comments on a draft. Audience members at both debates provided helpful comments as well.

While writing this book, I read many sex workers’ accounts of their experiences in the industry and I learned a lot from sex workers who write online. In particular, I would like to thank and acknowledge the writers at titsandsass. com, whose writing has been especially informative and insightful. One thing I learned from reading sex workers’ accounts is that people in the sex industry often feel that academic discussions of sex work abstract away from the complexity of workers’ own lived experiences in ways that obscure the true normative questions involved in everyday sex work. Though some degree of generalization is required to develop an effective normative critique of public policy, I tried to acknowledge the diversity of sex workers’ experiences and include their voices throughout the manuscript. The arguments I develop here build on arguments that sex workers and advocates have been making for years. In recognition of this, I dedicate my contribution to them.

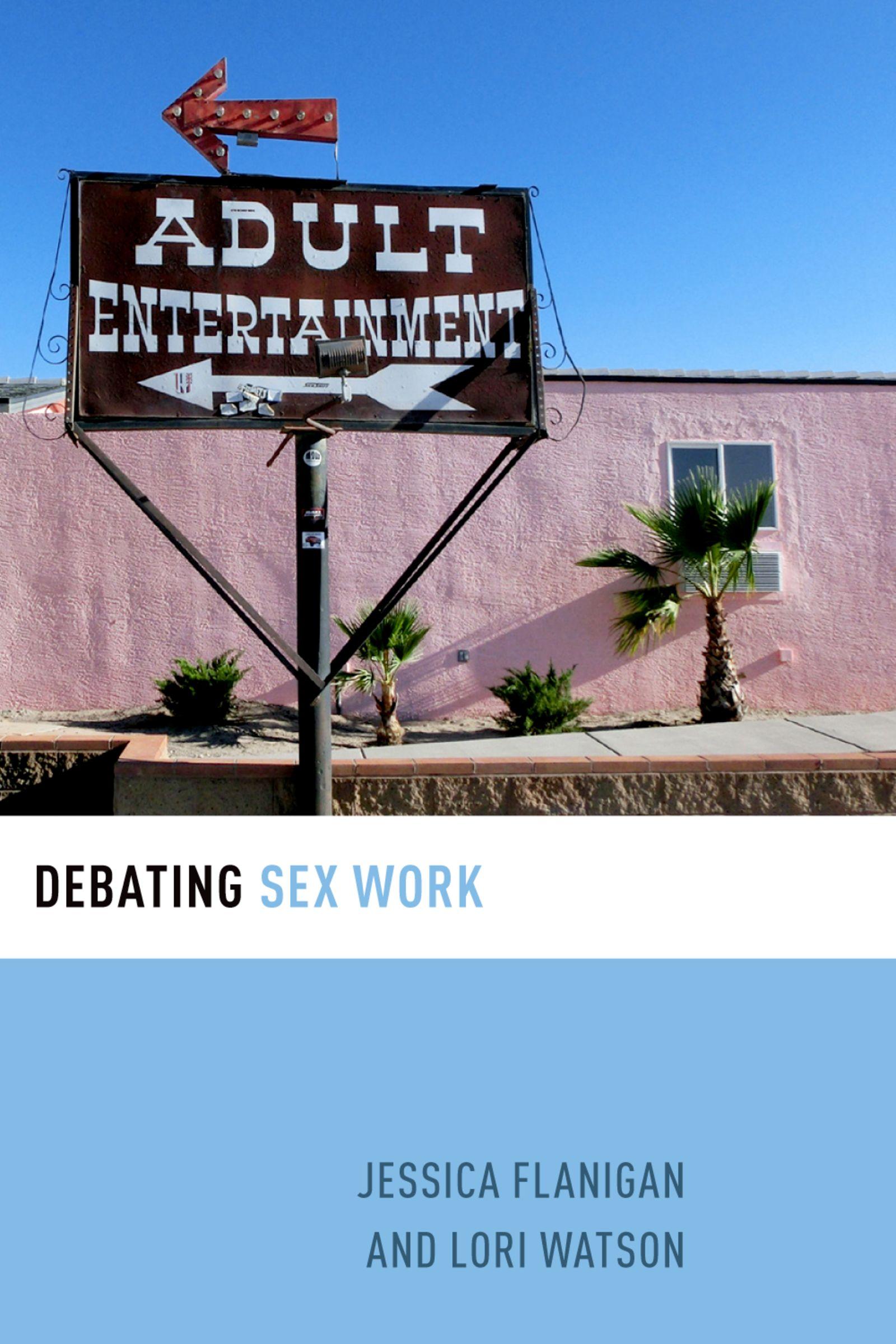

DEBATING SEX WORK

Introduction

LORI WATSON AND JESSICA FLANIGAN

“PROSTITUTION” IS OFTEN SAID TO be “the oldest profession.” Some feminists have argued that this saying is better rendered as “prostitution is the oldest oppression.”1 These feminists analyze prostitution as a form of sexual exploitation, as a form of sex-based inequality in which women are subordinated and used for sex on men’s terms. That prostitution was harmful to women was a foundational aspect of feminist organizing for much of the 20th century.

More recently, in the later part of the 20th century and into the 21st century, some feminists, and others, have come to reject this view of prostitution. In fact, they reject the term “prostitution” itself. Rather than analyzing women selling sex as a form of oppression, or a practice of sex-based inequality, these feminists see selling sex as an exercise of agency, a pathway to liberation from sex-based oppression, and reject analyses that place “sex work,” in their terms, as inherently degrading or unequal. Sex work

1. Catharine A. MacKinnon, Sex Equality, 3rd ed. (St. Paul, MN: Foundation Press, 2016), 1535.

Debating Sex Work. Lori Watson, Jessica Flanigan, Oxford University Press (2020). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190659882.001.0001

is work, like many other forms of work, they claim. In their view, denying this claim rests on unjust stigmatization of sex workers, and such stigmatization is a primary harm that sex workers face, according to these feminists and their allies.

This book aims to put these two contrasting views in conversation with one another. Each author aims to defend a particular analysis of prostitution/sex work, and from this analysis argues for a particular form of regulation. Lori Watson argues that prostitution is not like other forms of work and defends criminalizing the buying of sex while decriminalizing the selling of sex. Jessica Flanigan argues that sex work should be treated like other forms of work and argues for full decriminalization.

I.1 PRELIMINARIES AND DEFINITIONS

A few preliminary caveats are needed prior to providing the overview of the book’s structure. First, the book is primarily concerned with the practice of selling and buying sex, rather than all the activities that may fall under the umbrella of sex work. Pornography, stripping, phone, and Internet sex fall under the wider net of “sexual services” that many call sex work. The core arguments presented here certainly will give guidance and insight about how to think about these other forms of sex work. However, each requires its own full analysis for thinking about public policy and law: for example, pornography potentially raises free speech concerns, and thus any serious analysis of pornography, from a legal standpoint, must engage with such

concerns.2 Likewise, stripping and phone or Internet sex require their own analyses that account for the facts of their specificity, neither of which strictly speaking involves actual sex. Each author will refer to these other forms of sexual services when they are relevant to the arguments; however, this book is about debates concerning legal approaches to the buying and selling of sex.

Second, as noted, this book is primarily about the dominant and most prevalent form of prostitution, where women are the sellers and men are the buyers. Male prostitution exists, of course. However, it is a significantly smaller portion of the market, estimates range between 10% and 20% of all persons in prostitution. And importantly, there are no brothels, in any legal or decriminalized context, where men are for sale. Male prostitution occurs through the Internet, apps, and other contexts, but it is unlike the prostitution of women with respect to brothel prostitution. Nonetheless, many of the same issues that arise in thinking through the best public policy for prostitution apply equally to men and women. For example, men may become sex workers for similar reasons as women, and concerns about bodily integrity, sexual freedom, and equality, as well as occupational health and safety and security from violence, are relevant for women and men. Watson’s and Flanigan’s respective arguments about these matters can apply straightforwardly to all forms of prostitution. Nonetheless, men in prostitution are far less researched than women. As many of Watson’s and Flanigan’s arguments draw on the available

2. See Andrew Altman and Lori Watson, Debating Pornography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

empirical data concerning the costs and benefits of specific public policy and law, and the overwhelming majority of the data concerns women because they constitute the primary persons in prostitution, our arguments are largely focused there.

It is also helpful at this point to define a few terms. There are four forms of regulation of prostitution: criminalization, decriminalization, legalization, and the Nordic Model. Criminalization refers to a system of regulation in which statutes criminalize both the selling and the buying of sex. Additionally, under criminalization regimes, pimping, pandering, solicitation, and so on are criminalized. The severity of the crime and punishments vary across nation- states and jurisdictions. In the United States, the dominant approach to prostitution is criminalization; the only exception in the United States is some rural counties in Nevada in which prostitution is legalized. Most other countries also fully criminalize prostitution, though of course there are a substantial number of countries that either decriminalize or legalize prostitution. Both Watson and Flanigan reject criminalization, on the grounds that it makes women in prostitution worse off in nearly every respect.

The Nordic Model, first developed in Sweden in 1999, decriminalizes the selling of sex but criminalizes the buying. The model is premised on the view that prostitution is a practice of sex inequality that differentially harms and disadvantages women. Additionally, the Nordic Model, based on empirical evidence, rests on the view that demand for sexual services is the driving force of the prostitution market, and so it targets demand reduction as a primary strategy. Further, advocates of the

Nordic Model do not draw any sharp distinction between sex trafficking (typically defined as relying on force, fraud, or coercion) and prostitution (defined by critics as a separate phenomenon and as fully voluntary). In analyzing sex trafficking and prostitution as both part of a system of gender inequality, the advocates of the Nordic Model emphasize that inequality itself functions as a form of coercion and that prostitution is both a site and a cause of gender inequality. In her contribution, Watson defends the Nordic Model.

In contrast, legalization removes criminal laws and penalties for both the sellers and the buyers, but it also consists of a system of prostitution- specific laws. In contrast to what is referred to as decriminalization, legalization typically involves more robust regulation that is prostitution specific. Prostitution is legalized in Germany, the Netherlands, and some counties in Nevada, United States. Under legalization regimes, brothels are permitted and state regulated. Decriminalization entails removing criminal laws and penalties for both the buyers and the sellers of sex. In some places it also involves removal of criminal laws and penalties for pimping or living off the prostitution of another. Many sex workers and sex worker advocates or unions prefer this approach. In the summer of 2015, Amnesty International formally endorsed decriminalization. Although decriminalization is often contrasted with legalization with respect to whether prostitutionspecific regulations are legally instituted, in practice decriminalization often does involve some industry- specific legal regulations. For example, even in New South Wales (Australia) and New Zealand, both of which have decriminalized sex work, there are sex work– specific

regulations such as mandatory health screening and zoning laws. Thus, in practice the line between legalization and decriminalization can be unclear. Still, the decriminalization approach generally favors treating sex work like other kinds of work, acknowledging that some industryspecific regulations may be warranted but rejecting policies that aim to reduce the scope of the industry. In her contribution, Flanigan defends decriminalization.

I.2 THE CASE FOR THE NORDIC MODEL

Watson’s contribution argues in favor of the Nordic Model. She begins her contribution by rejecting the title of the book, “Debating Sex Work,” arguing that the phrase “sex work” is a pernicious cover-up and attempts to legitimize prostitution as “just another form of work.” In the first chapter of her contribution, Watson aims to present the initial positive case for the Nordic Model as a sex equality approach to prostitution. She argues that social conditions of inequality (based on sex, age, class, race) structure the conditions of entry into prostitution and structure it internally. Moreover, prostitution is harmful and constitutes the denial of basic human rights. Legal approaches that tolerate, support, or normalize prostitution violate equality principles. Yet given the asymmetrical inequalities between buyers and sellers, laws concerning prostitution should not treat them the same. Decriminalizing persons in prostitution (those that sell sex) raises their social status, and thus no law against selling sex is justified (for it entrenches inequality). Moreover, persons in prostitution should

be provided state support for their basic needs as well as means for exit, should they choose to exit.

Further, Watson contrasts two methodological approaches to arguments concerning public policy with respect to prostitution. Some theorists approach the questions concerning prostitution from the perspective of ideal theory. Crudely put, ideal theory involves making idealizing assumptions that abstract away from the actual practice under consideration. In contrast, non-ideal theory draws on the wealth of information concerning the ways in which prostitution functions here and now and frames the policy questions at stake in terms of what is achievable (or best) in light of those facts. Thus, Watson argues in favor of a materially grounded approach to thinking about what should be done about prostitution that requires an understanding of the actual facts that structure it as it occurs now, and that includes knowing who is there, why they are there, who benefits from prostitution, and who is harmed.

After providing some initial facts and analysis of sex inequality to further ground the argument for the Nordic model, Watson addresses a series of objections to arguments in favor of restricting markets in sex. Those objections include that any position aiming to curtail prostitution must rest on some form of unjustifiable moralism or paternalism; that prostitution should be understood as a fully voluntary choice and protected as such; that even if prostitution is exploitative, allowing such exploitation makes persons in prostitution better off than they would be otherwise; and, finally, that persons have rights to markets in sex such that any prohibitive policies violate rights.

In chapter 2 of her contribution, Watson critically engages with the often-repeated argument that “sex work

is work, like any other form of work.” Advocates of this argument rely upon it as a basis for either decriminalization or legalization. Watson dismantles this claim by showing that where sex is the “service,” occupational health and safety standards applicable to every other form of work cannot be met. Further, she explores the various ways in which persons in prostitution may be thought of as “workers” and argues that relevant legal standards in the context of discrimination laws and employment law cannot be met in the context of “sex work.” Thus, she shows that the burden of argument falls on advocates of decriminalization to legalization to argue for a series of exemptions from generally applicable laws. However, she argues such exemptions are unwarranted, do not achieve their aims, and would require institutionalizing inequality for persons in prostitution. In the final section of that chapter, Watson explores the possibilities for recognizing “sex contracts.” There she argues that contractualizing sex is incompatible with equality.

After presenting the initial case for the Nordic Model and exposing the flaws of the alternatives, chapter 3 of Watson’s contribution returns to provide the full defense of the Nordic Model. There she presents the evidence that policies of toleration (whether decriminalization or legalization) are proven to increase the trafficking of persons for sexual exploitation. She also presents the evidence that demand reduction is the most effective legal approach to prostitution. Further, recent research on the behaviors and attitudes of buyers is presented to further make the case that targeting demand is central to eliminating the harms of prostitution. Finally, she considers a series of objections to the Nordic Model and replies to them.

I.3 THE CASE FOR DECRIMINALIZATION

Flanigan’s contribution argues in favor of decriminalization. She begins her contribution by arguing that sex work is, largely, just another form of work. In the first chapter of her contribution (chapter 4), Flanigan argues that the Nordic Model violates the rights of sex workers and their clients. Furthermore, decriminalization has better consequences for sex workers, their clients, and the general public than either criminalization or the Nordic Model. In addition, criminalization is profoundly inegalitarian, and in practice the Nordic Model may be as well. In sum, many of the same reasons in favor of rejecting criminalization are also reasons to reject the Nordic Model.

Flanigan then considers objections to decriminalization, focusing on arguments in favor of the Nordic Model in chapter 5. She first considers the possibility that selling sex is not an especially important right, so public officials can restrict people’s ability to sell sexual services on the grounds that selling sex is often insufficiently voluntary, exploitative, or degrading. In response, Flanigan agrees that the sale of non- consensual sex or sex with children ought to be legally prohibited (of course) but that these conditions are not intrinsic to sex work. The fact that a person has poor economic prospects or exists in a state of social marginalization due to her sex, sexuality, race, gender, or citizenship status does not entail that she is incapable of consenting to work or that it is wrong to pay her for her labor. Rather, by enacting policies that limit socio-economically marginalized people’s economic prospects, such as criminalization or the Nordic Model, public officials make members of these

groups worse-off by perpetuating stigmatizing judgments and reducing their bargaining power in the labor market.

Another objection to decriminalization stems from the idea that officials are sometimes justified in treating people paternalistically. On this view, if paternalism were sometimes justified and if the enforcement of the Nordic Model or criminal penalties would promote the well-being of sex workers, then officials could be justified in enforcing these policies. In response, Flanigan argues that officials should generally avoid paternalism but that even if paternalism were justified, paternalistic arguments cannot justify limiting the sex industry because even if sex work is difficult and distressing labor, sex workers are better judges of their own well-being than uninformed public officials who know nothing of their values and experiences that led them to choose sex work.

Watson and others reject decriminalization on egalitarian grounds. They argue that a decriminalized sex industry would entrench or exacerbate existing economic or social inequalities. As an empirical matter, Flanigan rejects the claim that the decriminalization of sex work would make inequality worse. And as a conceptual matter, Flanigan argues that recognizing the legitimacy of sex work needn’t conflict with embracing egalitarian values.

I.4 CLARIFYING THE DEBATE

Though Watson and Flanigan disagree about whether public officials should prohibit citizens from paying for sex and whether sex work should be treated like other forms of work, they agree that any defensible approach to sex work

should not target, stigmatize, or punish sex workers. In this way, Watson and Flanigan broadly agree that the moralistic and punitive approach that characterizes many nations’ approach to prostitution/sex work, including that of the United States is unjust.

The criminalization of prostitution/sex work is unjust for several reasons. First, police officers often enforce the laws against buying and selling unequally. It is women, the sellers, who are targeted and arrested. For example, data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics from 2012, the most recent year in which data are available, report a total of 56,575 arrests for “prostitution and commercialized vice.”3 Of the total number, 18,610 of those arrested were male, 37,965 female. Data from 2010 reports 62,670: 19,480 male and 43,190 female, respectively.4 Given that there are more buyers than sellers, these data especially suggest selective enforcement targeting women.

Even when buyers are arrested or ticketed, depending on jurisdiction, the consequences of arrest are far less severe and burdensome than for prostituted persons. Given the relative social and economic position of buyers as compared with sellers (mainly men compared with women), buyers can much more easily make bail, hire effective lawyers, plead to lesser charges, attend diversion programs, and the like. Women, the sellers, are less likely to make bail, or they may depend on an abusive pimp to bail them out, putting them further in the pimp’s debt. The women are more likely to lack the resources to hire effective lawyers;

3. https:// www.bjs.gov/ index.cfm?ty=datool&surl=/ arrests/ index. cfm#

4. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/aus9010.pdf

have prior criminal convictions for prostitution, which increase the severity of punishment for repeat offenses; suffer greater economic consequences as a result of longer jail time, which may lead to homelessness; be the primary care-givers of children (than buyers) and face state intervention with respect to custody arrangements; and face additional obstacles to “leaving the life” as a result of a criminal record.

Additionally, under criminalization regimes, persons in prostitution have an adversarial relationship with police. Police are known to coerce and extort sex acts from sex workers, using the threat of arrest to force compliance. Moreover, persons in prostitution are reluctant and unlikely to call police for assistance when they are victims of crimes both inside and outside of prostitution. And even when they do, their complaints are often dismissed based on stereotypical thinking that prostitutes cannot be raped or be victims of sexual assault.

Criminalization also makes persons in prostitution/ sex workers more vulnerable relative to buyers (johns) insofar as buyers know that police intervention is unlikely and persons in prostitution are unlikely to rely on police for support, safety, and enforcement. Moreover, there is no evidence that criminalization of both the buying and selling of sex is effective as a deterrent for either buyers or sellers. Its primary purpose does indeed suggest a moral condemnation of prostitution, with no real purpose of improving the lives of persons in prostitution.

Sometimes, in light of profound disagreement, one might conclude that political and philosophical arguments are doomed to fail, that progress is impossible, and that we will never know the truth about which policy is best. But

historically, the criminalization and policing of women’s bodies has been the norm. It is only in the last century that people have begun to see that incarcerating persons in prostitution is unjust. Rather than relying on antiquated moralisms that blame and shame women, in particular, for engaging in prostitution, the debate here, and globally, concerns what is best for women made vulnerable by systems of prostitution. This is, indeed, a radical shift in orientation. Though Flanigan and Watson strongly disagree about which policy is the best approach, both offer arguments framed in terms of the interests of women and drawing on principles of sex equality. A key disagreement between them concerns precisely what taking women’s equality seriously entails, but this debate is a long way from the stigmatizing and shaming of women in prostitution so prevalent in the recent past and sometimes still a part of dominant discourses.