Tribology

on the Small Scale: A Modern

Textbook on Friction, Lubrication, and Wear C. Mathew Mate And Robert W. Carpick

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/tribology-on-the-small-scale-a-modern-textbook-on-fri ction-lubrication-and-wear-c-mathew-mate-and-robert-w-carpick/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Knowledge and Conditionals: Essays on the Structure of Inquiry Robert C Stalnaker

https://ebookmass.com/product/knowledge-and-conditionals-essayson-the-structure-of-inquiry-robert-c-stalnaker/

eTextbook 978-1118353912 Grease Lubrication in Rolling Bearings (Tribology in Practice Series)

https://ebookmass.com/product/etextbook-978-1118353912-greaselubrication-in-rolling-bearings-tribology-in-practice-series/

The Cabin on the Hill - Box Set - A Riveting Small Town Kidnapping Mystery Boxset Robert J Walker

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-cabin-on-the-hill-box-set-ariveting-small-town-kidnapping-mystery-boxset-robert-j-walker/

The Zero Transaction Cost Entrepreneur: Powerful Techniques to Reduce Friction and Scale Your Business Dermot Berkery

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-zero-transaction-costentrepreneur-powerful-techniques-to-reduce-friction-and-scaleyour-business-dermot-berkery/

Biotribology of Natural and Artificial Joints: Reducing Wear Through Material Selection and Geometric Design with Actual Lubrication Mode

Teruo Murakami

https://ebookmass.com/product/biotribology-of-natural-andartificial-joints-reducing-wear-through-material-selection-andgeometric-design-with-actual-lubrication-mode-teruo-murakami/

Modern C++ for Absolute Beginners: A Friendly Introduction to the C++ Programming Language and C++11 to C++23 Standards, 2nd Edition Slobodan Dmitrovi■

https://ebookmass.com/product/modern-c-for-absolute-beginners-afriendly-introduction-to-the-c-programming-languageand-c11-to-c23-standards-2nd-edition-slobodan-dmitrovic/

Young People and the Smartphone: Everyday Life on the Small Screen Michela Drusian

https://ebookmass.com/product/young-people-and-the-smartphoneeveryday-life-on-the-small-screen-michela-drusian/

Agile Energy Systems: Global Distributed On-Site and Central Grid Power 2nd Edition Woodrow W. Clark Iii

https://ebookmass.com/product/agile-energy-systems-globaldistributed-on-site-and-central-grid-power-2nd-edition-woodrow-wclark-iii/

A SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Strategy Focused on Population-Scale Immunity Mark Yarmarkovich

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-sars-cov-2-vaccination-strategyfocused-on-population-scale-immunity-mark-yarmarkovich/

TribologyontheSmallScale

AModernTextbookonFriction,Lubrication,andWear

SecondEdition

C.MathewMate and RobertW.Carpick

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress2019

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2008

SecondEditionpublishedin2019

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2019941494

ISBN978–0–19–960980–2

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780199609802.001.0001

PrintedinGreatBritainby Bell&BainLtd.,Glasgow

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Frontcoverimage: Moleculardynamicssimulationofanasperitycoveredwithanoxidelayermakingcontact withaflatmetalsurfacewherethecontactareaconsistsofonlyafewatom-to-atomcontacts.Inthisimage, oxygenatomsarerepresentedbybluespheres,oxidizedplatinumatomsbywhitespheres,andmetallicplatinum atomsbygreyspheres.ImagecourtesyofProf.AshlieMartiniandRimeiChenattheUniversityofCalifornia, Merced.

Preface

Theimportanceoffriction,lubrication,adhesion,andwearintechnologyandeveryday lifeiswellknown;theyareencounteredwhenevertwosurfacescomeintocontact,suchas whenyouwalkacrossaroom,pushapencilacrossapieceofpaper,orstrokeyourfavorite pet.Whilemanyexcellentbookshavebeenwrittenontribology,mosthavefocusedon analyzingthemacroscopicaspects,withonlyslightattentionpaidtotherichinterplay betweentheatomsandmoleculesatthecontactingsurfaces,asthesehavehistorically beenpoorlyunderstood.Inrecentdecades,however,manytalentedphysicists,chemists, engineers,andmaterialsscientistshavebeguntodecipherthenanoscaleoriginsof tribologicalphenomena.Giventhetremendousprogressandexcitementgeneratedby thisendeavor,nowseemstheopportunetimeforamoremodernapproachontribology emphasizinghowmacroscopictribologicalphenomenaoriginateattheatomicand molecularlevel.

Thegoalofthisbookistoincorporateabottomupapproachtofriction,lubrication, andwearintoamoderntextbookontribology.Thisisdonebyfocusingonhowthese tribologicalphenomenaoccuronthe smallscale—theatomictothemicrometerscale. Wehopetodemonstratethatfocusingonthemicroscopicoriginsleadstoamore scientificallyrigorousunderstandingoftribologythantypicallyachievedbytribology booksthattakeamacroscopicempiricalapproach.Itisalsohopedthatthereader becomesenthusedwiththesameexcitementasthoseworkinginthefieldhavefor unravelingthemysteriesoffriction,lubrication,andwear,aswellasanappreciation forthemanychallengesthatremain.

Thisbookcoversthefundamentalsoftribologyfromtheatomicscaletothe macroscale.Thebasicstructure—withchaptersontopography,friction,lubrication,and wear—issimilartothatfoundinconventionaltribologytexts.Thesechapterscoverthe microscopicoriginsofthemacroscopicconceptscommonlyusedtodescribetribological phenomena:roughness,elasticity,plasticity,frictioncoefficients,andwearcoefficients. Somemacroscaleconcepts(likeelasticity)scaledownwelltothemicro-andatomicscale,whileothermacroscaleconcepts(likehydrodynamiclubricationandwear)donot. Thisbookalsohaschaptersonsurfaceenergyandsurfaceforces,andcoversothertopics nottypicallyfoundintribologytexts,butwhichbecomeincreasinglyimportantatthe smallscale:capillarycondensation,disjoiningpressure,contactelectrification,molecular slippageatinterfaces,andatomicscalestick-slip.

Tribologyisacontinuallyevolvingfield,andnanoscalestudiesoftribologyhavean especiallyrapidpaceofprogress.Thesefactors,combinedwithfeedbackfrommany readersofthefirstedition,includingstudentsanduniversityteachers,havemotivated thewritingofasubstantiallyrevisedsecondeditionof TribologyontheSmallScale. For thesecondedition,allthechaptershavehadnumerousnewsectionsaddedandtherest

ofthechapterupdatedandrevised.Someofthenewsectionsaddexamplesfromrecent experimentsthatillustratemodernnanoscaletribologicalconcepts.Othernewsections incorporatethemostsignificantadvancementsthathaveoccurredinnanoscaletribology sincethepublicationofthefirstedition,suchasPersson’scontacttheory;thepower spectrumtreatmentofsurfaceroughness;andtheapplicationoftransitionstatetheoryto wear,viscosity,andfriction.Anotherimportantenhancementofthesecondeditionover thefirsteditionistheadditionofproblemsattheendofeachchapter.Theseproblems aredrawnfromclassestaughtatUniversityofPennsylvaniabyProf.Carpick,which werereviewedandimprovedbybothauthors;alsomanynewproblemswerespecifically createdforthesecondedition.

Thisbookisintendedtobesuitableasatextbookfortribologycoursestaughtatthe advancedundergraduateandgraduatelevelinmanyengineeringprograms.Intermsof thescientificandmathematicalbackgroundexpectedofthereader,nospecialknowledge isassumedbeyondthattypicallyencounteredbyscienceandengineeringstudentsin theirfirstfewyearsatauniversity.

Inadditiontocollegestudentslearningabouttribologyforthefirsttime,thisbookis intendedforseveralotheraudiences:

• Academicsandscientistswhowishtolearnhowfriction,lubrication,andwear occuratthemicroscopicandatomicscales.

• Engineersandtechnicianswhodonotconsiderthemselvestribologists,butwho workwithtechnologies(suchasMEMS,diskdrives,andnanoimprinting)wherea goodgraspofhowtribologicalphenomenaoccuronthesmallscaleisessential.

Wewouldliketothankallthosewhoprovidedhelpandencouragementduringthe writingofthisbook:

• OxfordUniversityPressforprovidingustheopportunitytopublishthisbookwith themandfortheirencouragementandpatienceduringthewritingofthefirstand secondeditionsofthisbook.

• ProfessorSteveGranickattheUniversityofIllinois,Urban-Champaignand ProfessorCurtFrankatStanfordUniversitywhohostedoneofus(C.M.Mate) asavisitingscholarattheiruniversitiesduringthewritingofthefirstedition (S.Granick)andthesecondedition(C.Frank).

• Ourcolleagueswhowerekindenoughtocommentonvariousdraftchaptersand provideadviceonparticularaspectsoftribology:

oFirstedition–PeterBaumgart,Tsai-WeiWu,Run-HanWang,RobertWaltman, BrunoMarchon,FerdiHendriks,BernhardKnigge,QingDai,XiaoWu,Barry Stipe,BingYen,ZvonimirBandic,KyosukeOno,andYasunagaMitsuya. oSecondedition–AndrewJackson,RobertSmith,GregRudd,TevisJacobs, JoelLefever,HarmanKhare,AshlieMartini,JackieKrim,NicholasSpencer, MarkRobbins,LarsPastewka,ArupGangopadhyay,andallofthestudentsof ProfessorCarpick’snanotribologyclass.

• Ourfamiliesandespeciallyourspouses,whohavealwaysbeenconstantsourcesof supportandencouragement.

1.2.1Tribologysuccessstory#1:reducingautomotivefriction

1.2.2Tribologysuccessstory#2:solvingadhesioninMEMSdevices6

1.2.3Tribologysuccessstory#3:slider–diskinterfacesindiskdrives9

2.4.2.1Example:

2.4.3Asperitysummitsroughnessparameters

2.4.3.1Example:summitparametersforadiskfroma

3.2.2Elasticdeformationofasingleasperitycontact

3.2.2.1Approximatinganasperitycontactassphereonflat

3.2.2.2Elasticcontactareaforasphereonaflat

3.2.2.3Approximatinganasperitycontactasaflatpunch

3.2.3Elasticdeformationfromtangentialloading

3.3.3Plasticdeformationinthesphere-on-flatgeometry

3.4Realareaofcontact

3.4.1GreenwoodandWilliamsonmodel

3.4.1.1Example:TiNcontacts

3.4.1.2RealareaofcontactusingtheGreenwoodand

3.4.1.3Example:recordingheadonalasertextured

3.4.2Perssontheoryofthecontactmechanicsofroughsurfaces

4.1Amontons’andCoulomb’slawsoffriction

4.1.1Coefficientsoffriction

4.2Physicaloriginsofdryfriction

4.2.1Adhesivefriction

4.2.2Plowingfriction

4.2.3Workhardening

4.3Staticfriction

4.3.1Stick-slip

4.3.1.1Velocity-controlledstick-slip

4.3.1.2Time-controlledstick-slip

4.3.1.3Displacement-controlledstick-slip

4.4Problems

5.1Liquidsurfacetension

5.2Capillarypressure

5.2.1Capillarypressureinconfinedplaces

5.2.2TheKelvinequationandcapillarycondensation

5.2.2.1Example:capillarycondensationofwaterina nano-sizepore

5.2.2.2Example:capillarycondensationofanorganic vaporatasphereonflatgeometry

5.3Interfacialenergyandworkofadhesion

5.4.1Typesofwetting

5.4.1.1Superhydrophobicity

5.4.2.1Contactanglehysteresis

5.5Surfaceenergyofsolids

5.5.1Whysolidsarenotlikeliquids

5.5.2Estimatingsolidsurfaceenergiesfromcontactangles

5.5.2.1Equationofstatemethod

5.5.2.2Surfacetensioncomponentsmethod

5.5.3Othermethodsforestimatingsolidsurfaceenergies

5.6Adhesionhysteresis

5.6.1Mechanicaladhesionhysteresis

5.6.2Chemicaladhesionhysteresis

6.1.1DerivationoftheDerjaguinapproximation

6.2.1Forcebetweenasphereandaflat

6.2.1.1Example:adhesionforcebetweentwopolystyrene spheres

6.2.1.2Example:adhesionforcebetweenapolystyrene sphereandaPTFEflat

6.2.1.3Example:adhesionforceforanatomicallysharp asperity

6.2.2Adhesion-induceddeformationatasphere-on-flatcontact

6.2.2.1TheJohnson–Kendal–Roberts(JKR)theory

6.2.2.2Derjaguin–Müller–Toporov(DMT)theory

6.2.2.3Adhesiondeformationinnanoscalecontacts

6.2.3Effectofroughnessonadhesioninadryenvironment

6.2.3.1Example:effectofroughnessonAFMadhesion

6.2.4Criterionforstickysurfaces

6.2.4.1Examplesofwhensurfacesaresticky 158

6.3Wetenvironment 159

6.3.1Forceforasphere-on-flatinawetenvironment

6.3.1.1Example:lubricantmeniscusforceonanAFMtip 161

6.3.1.2Solid–solidadhesioninthepresenceofa liquidmeniscus 162

6.4Menisciinsandandcolloidalmaterial

6.5Meniscusforcefordifferentwettingregimesatcontactinginterfaces168

6.5.1Toedippingregime 168

6.5.1.1Example:toedippingadhesionwithanexponential distributionofsummitheights 169

6.5.2Pillboxandfloodedregimes

6.5.3Immersedregime

6.6Example:liquidadhesionofamicrofabricatedcantileverbeam

6.7Example:surfaceforcesinbiologicalattachments

6.8Problems

7PhysicalOriginsofSurfaceForces

7.1Normalforcesignconvention

7.3.1VanderWaalsforcesbetweenmolecules

7.3.1.1Retardationeffectsfordispersionforces

7.3.2VanderWaalsforcesbetweenmacroscopicobjects

7.3.2.1Molecule–flatsurfaceinteraction

7.3.2.2Flat–flatinteraction 189

7.3.2.3Sphere–flatinteraction

7.3.3TheHamakerconstant

7.3.3.1DeterminingHamakerconstantsfromLifshitz’stheory191

7.3.3.2Example:vanderWaalsforceonapolystyrenesphere aboveaPTFEflat 196

7.3.4SurfaceenergiesarisingfromvanderWaalsinteractions 197

7.3.5VanderWaalsadhesivepressure 199

7.3.6VanderWaalsinteractionbetweencontactingroughsurfaces200

7.3.6.1Example:stuckmicrocantilevers 202

7.3.7Example:geckoadhesion 204

7.3.8VanderWaalscontributiontothedisjoiningpressureofa liquidfilm 206

7.4Liquid-mediatedforcesbetweensolids

7.4.1.1Example:experimentalobservationofsolvation forcesbyAFM

7.4.2Forcesinanaqueousmedium

7.4.2.1Electrostaticdouble-layerforce

7.4.2.2Hydrationrepulsionandhydrophobicattraction

7.5Contactelectrification

7.5.1Conductor–conductormechanismofcontactelectrification221

7.5.2Metal–andinsulator–insulatormechanismsofcontact electrification

7.5.2.1Electrostaticdischargeandtriboluminescence

7.5.3Example:contactelectrificationinducedforceforaPVC spherecontactingaPTFEflat

8MeasuringSurfaceForces

8.1Surfaceforceapparatus(SFA)

8.2Atomicforcemicroscope(AFM)

8.2.1AFMcantileversandtips

8.3.1VanderWaalsforcesundervacuumconditions

8.3.2Atomicresolutionofshort-rangeforces

8.3.3Capillarycondensationofcontaminantsandwatervapor

8.3.4Bondedandunbondedperfluoropolyetherpolymerfilms

8.3.5Electrostaticdouble-layerforce

9.1Lubricationregimes

9.2.1Definitionandunitsofviscosity

9.2.2Non-Newtonianbehaviorandsheardegradation

9.2.3Eyringmodelforviscosityandshearthinning

9.2.4Temperaturedependence

9.3Fluidfilmflowbetweenparallelsurfaces

9.4Slippageatliquid–solidinterfaces

9.4.1Definitionofsliplength

9.4.2Example:shearstressinthepresenceofslip

9.4.3Example:measuringsliplengthsusingviscousforce duringdrainage

9.4.4Mechanismsforslipatliquid–solidinterfaces

9.4.4.1Theoriesfordefectslip

9.4.4.2Globalslipofpolymermelts

9.4.4.3Apparentslip

9.4.5Whydoestheno-slipboundaryconditionworksowell?280 9.5Fluidfilmlubrication

9.5.1Hydrodynamiclubrication

9.5.1.1Inclinedplanebearing

9.5.1.2Rayleighstepbearing

9.5.1.3Journalbearing

9.5.1.4Cavitation

9.5.2Gasbearings

9.5.2.1Slipflowingasbearings

9.5.3.1Pressuredependenceofviscosity

9.5.3.2Pressureinducedelasticdeformation

9.5.3.3ExperimentalmeasurementsofEHL

10.2.4.1Exampleoftheimportanceofend-groupsina liquidlubricantfilm

10.3.1Disjoiningpressureofaliquidlubricantfilm

10.3.4Meniscusforce

10.3.4.1Example:stictionofarecordingheadslider

10.3.4.2Calculatingthemeniscusforce

10.4Capillarycondensationofwatervapor

10.5Exampleofcoldwelding:whathappensintheabsenceoflubrication340

11.1Conceptofadhesivefriction

11.1.1Cobblestonemodel

11.2.1Frenkel–Kontorovamodel

11.2.2Superlubricity

11.2.2.1Superlubricityofagraphiteflakeongraphite

11.2.2.2Otherexamplesofsuperlubricity

11.2.2.3Impactoffinitecontactareaonsuperlubricity359 11.2.3Exampleofextremeatomisticlocking:coldwelding

11.2.4.1Example:anAFMtipslidingacrossanNaCl crystalatultra-lowloads

11.2.4.2Thermalactivationofstick-slipevents

11.2.5RoleofstiffnessintheFrenkel–Kontorovaand Prandtl–Tomlinsonmodels

11.2.6Moleculardynamic(MD)simulations

11.2.7Whystaticfrictionoccursinreal-lifesituations

11.3.1Frictionofatoms,molecules,andmonolayerssliding oversurfaces

11.3.1.1Quartzcrystalmicrobalance

11.3.1.3Phononicfriction

11.3.1.4Electronicfriction

11.3.1.5Pinningofanabsorbedlayer

11.3.2Frictionaldissipationmechanismsinsolid–solidsliding380

12.6.1.1Example:load–displacementcurvesonsingle

12.6.1.2Example:fractureandplasticityinahardcarbonfilm420

Introduction

Startinginchildhood,weallacquiredasufficientworkingknowledgeoftribologytolead happy,productivelives.Crawlingasinfants,wemasteredthefrictionalforcesneeded togetuswherewewantedtogo.Eventually,wegraduatedfromcrawlingtowalking toschool,whereanoccasionalicysidewalk,ifonelivedinacoldclimate,provideda challenginglessononslippageandtraction.Ifourteacheratschoolaskedustomove ourchairbackwards,weknewintuitivelythatthechairwouldbeeasiertoslideifnoone wassittingonit.Masteringfrictionwasalsoacriticalcomponentinmanyofthegames thatweplayed,whetheritwasgrippingabat,maintainingtractionwhenrunningand stopping,orputtingadevilishspinonaping-pongball.

Inadditiontofriction,wealsoencounteredwearandadhesionatayoungage.The detrimentalaspectsofwearmayhavebeenfirstlearntwhenourfavoritetoysworeout quickerthanwefelttheyshould.Themorepositiveaspectsofwearmayhavebeen firstappreciatedaswesandedourfirstwoodworkingprojectsandpolishedourfirstart sculpturesintotheirfinalartisticshapes.Wealsoquicklylearntthatcrayonsandpencils becomedullwhenrubbedagainstpaper,butcanbesharpenedbackupbygrindingina pencilsharpener.Ourfirstawarenessofadhesionmayhavebeenonahumiddaywhen someonecommentedonhow“sticky”itfeels.Orperhapsitwaswhenwefirstwondered whyspidersandfliescanwalkontheceiling,butdogsandcatscannot.

Onceincollege,scienceandengineeringclassesusuallyonlycoverthetopicsof friction,lubrication,adhesion,andwearatarudimentarylevel.Forfriction,allthatis usuallytaughtisthatstaticfrictionisgreaterthankineticfriction,frictionisproportional tothenormalcontactforcewithdifferentcoefficientsfordifferentmaterials,andviscous frictioninafluidisproportionaltovelocity.Theprinciplesofthinfilmlubricationare coveredonlyinanadvancedclassonfluidmechanicsasanexampleofsolvingReynolds’ equation.Wearisonlybrieflycoveredinspecializedengineeringclassesontribology, despiteitspervasivenessasafailuremechanism,andadhesioniscoveredincidentallyin coursesonchemicalbondingorpolymerphysics.

Consideringhowmuchweencounterthetribologicalphenomenaoffriction,lubrication,adhesion,andwearinourdailylivesandthewideextentofthesephenomena inindustryandtechnology,onemightbepuzzledwhythesetopicsareonlymarginally coveredinourcurrenteducationsystem.Intheauthors’opinion,thefaultliesnotwith collegesanduniversities,butratherwiththeinherentlycomplicatedandinterconnected

physicaloriginsofmosttribologicalphenomena.Thismultifacetednaturehasmade itdifficultforscientistsandengineerstodeveloppredictivetheoriesformosttribologicalphenomena.Instead,empiricallyderivedtrends(forinstance,thatfrictionis proportionaltotheloadingforce)areoftentheonlypredictivetoolsavailable.These empiricalapproacheshavethedrawbackofbeingpredictiveonlyoveralimitedrangeof parameters.Sincetheunderlyingphysicalmechanismsarenotwellunderstood,oftenone doesnotevenknowwhattheimportantparametersareoroverwhatrangetheobserved trendsarevalid.Similarly,ifapurelyanalyticalapproachisattempted,thelackof knowledgeoftherelevantparametersoftenleadstoinaccuratepredictionsoftribological behavior.Thispoorpredictivepowerhasledtothefieldoftribologybeingperceivedin manyscientificquartersasmoreofa“blackart”thanasascientificdiscipline.Thislack ofpredictivepowermayalsobethereasonwhyeducatorsarereluctanttospendmuch timeontribologyconceptswhoseapplicationmaybedubiousinmanysituations.

Forexample,ifonewantedtoanalyzethefrictionforceactingonachairsliding acrossahardwoodfloor,themostexpedientapproachwouldbetotakeadvantageof pastempiricalstudiesthathaveshownthatfrictionisgenerallyproportionaltothe loadingforce(theweightofthechairandthepersonsittingonit)withaproportionality constantcalledthecoefficientoffrictionor μ.Usingthisapproach,thenextstepisto determinefromexperimenthow μ dependsontheparameterssuspectedofinfluencing friction:slidingvelocity,hardnessofthewood,typeoffloorwax,etc.Afterafewhours ofexperiment,onewouldbegintohaveagoodideahowfrictiondependsonthese parameters,butwouldhavetroublepredictingwithoutfurtherexperimentationhowthe frictionmightchangeifnewparameterswereintroduced,forexample,byaddingfelt padstothebottomofthechairlegstopreventthemfromscratchingthehardwoodfloor.

Whilemanytribologyproblemsarestillbestapproachedthroughempiricalinvestigations,thesetypesofinvestigationsarenotthefocusofthisbook.Instead,thefocus isonthephysicaloriginsoftribologyphenomenaandhowunderstandingthesecanbe usedtodevelopanalyticalapproachestotribologicalproblems.Inessence,thegoalisto maketribologylessofablackartandmoreofascientificendeavor.Thiswillbedone byemphasizinghowthetribologicalphenomenaoffriction,lubrication,adhesion,and wearoriginateatthesmallscale.Or,equivalently,howphysicalphenomenaoccurringat theatomictomicronscaleeventuallyleadtomacroscaletribologicalphenomena.The hopeisthat,oncereadershavegainedasolidunderstandingofthenanoscaleorigins oftribologicalphenomena,theywillbewellequippedtotacklenewtribologyproblems, eitherbyapplyinganalyticalmethodsordevelopingbetterempiricalapproaches.

1.1Whyisitcalledtribology?

Thepursuitofthemicroscopicoriginsoffriction,lubrication,adhesion,andwearisnot arecentscientificactivity.Overthecenturies,manyhaveponderedontheseorigins,and inrecentdecadesithasbecomequitefashionableforleadingscientiststotakeupthe challenge.Oneoftheearlypioneersandchampionsofthemicroscopicapproachwas Prof.DavidTabor(1913–2005)ofCambridgeUniversity.Oneofthefrustrationsfaced

byTaborandothersworkinginthisfieldatthattimewasthelackofascientificnamefor theareaofstudyencompassingallthephenomenaoccurringbetweencontactingobjects. Itwasfeltthatthislackofterminologywasdeprivingthefieldofacertainlevelofstatus andrespectwithinthescientificcommunity.(Forexample,someofTabor’scolleagues attheCavendishLaboratoryinCambridgewoulddisparaginglyrefertohisresearch groupasthe“RubbingandScrubbingDepartment”(HahnerandSpencer1998).)To counterthis,Taborcoinedthename tribophysics fortheresearchgroupthatheheaded whileinvestigatingpracticallubricants,bearings,andexplosivesatMelbourneUniversity duringtheSecondWorldWar,whichhederivedfromtheGreekword tribos,meaning rubbing.

In1966,H.PeterJostledaCommitteeoftheBritishDepartmentofEducationand Sciencetoproducethe“JostReport,”whichofficiallylaunchedtheword tribology to describetheentirefieldandwhichwasderivedfromTabor’searlierword,tribophysics (Jost1966).Whiletheliteraltranslationoftribologyis“thescienceofrubbing,”inthe JostReport,thisdefinitionwasadopted:“Thescienceandtechnologyofinteracting surfacesinrelativemotionandofassociatedsubjectsandpractices.”AftertheJost Report,thetermtribologyquicklybecameestablishedasthefield’sofficialname,and thewordnowcommonlyappearsinthetitlesofpapers,books,journals,professorships, andinstitutionsconcernedwiththistopic.

Whilethenametribologyhascertainlyincreasedthecredibilityofthefieldasavalid disciplineofscientificandengineering,thetermremainssomewhatunknownoutside thefield.So,tribologistsneedtobepreparedtoexplainthewordtothosewhohavenot heardofitbefore,orwhomistakeitforthestudyoftribesorofthenumberthree.

1.2Economicandtechnologicalimportanceoftribology

Oneofthegoalsofthe1966JostReportwastodocumentthepotentialeconomicsavings thatcouldbeachievedthroughthedevelopmentandadoptionofbetterengineering practicesforminimizingtheunnecessarywear,friction,andbreakdownsassociatedwith tribologicalfailures.ThepossiblesavingswithintheUnitedKingdomwereestimatedto beroughlyequivalentto1%ofitsGNP.SincetheJostReport,otheragencieshavealso evaluatedpossiblesavings,andtheconsensusviewnowisthatbetween1%and2%of mostindustrializednations’GNPcouldbegainedthroughproperattentiontotribology (Dakeetal.1986,Jost1990,Chattopadhyay2014);forexample,thiswouldcorrespond to$186–$371billionfortheUnitedStatesin2017.

Whilethesepotentialeconomicbenefitshavelongbeenrecognized,thishasnotalways beenfollowedupwiththelevelofinvestmentintribologyresearchanddevelopment felttobewarrantedbymanytribologists.Possiblyamajorfactorinthisreluctanceto backtribologyprojectscomesfromitshistorical“blackart”character,whichtends tocastdoubtonhowsuccessfulaproposedtribologyprojectwillbe.Hopefully,this bookwillhelpdiminishthesedoubtsbydemonstratingarationalandscientificbasisfor approachingtribologicalproblems.Anotherwayofdiminishingdoubtsaboutthescience oftribologyisthroughafewsuccessstories.

1.2.1Tribologysuccessstory#1:reducingautomotivefriction

Improvingthefueleconomyofcarsandtruckshaslongbeenamajortechnologygoal oftheautomotiveindustry(TungandMcMillan2004,Holmbergetal.2012,Leeand Carpick2017).Anobviouswayforimprovingfuelefficiencyisreducingtheenergyloss throughfriction.Fortheaveragepassengercar,theanalysisbyHolmbergetal.(2012) indicatesthatonlyabout21.5%ofthefuelenergygoestoactuallymovingthecaralong theroad,while33%islostovercomingfrictionwithintheautomobile(Figure1.1).

Duetothefairlymaturenatureofautomotivetechnology,generallyonlyincremental improvementsareachievedeachdesigncycle;however,thecumulativeeffectofthese incrementalimprovementshasbeenquitesubstantial.Forexample,from1980to2016, theaveragefueleconomyofcarsandtruckssoldintheUnitedStatesincreasedfrom 19.2to24.7milespergallon,despitetheaveragehorsepowermorethandoublingfrom 104to230(U.S.EnvironmentalProtectionAgency2017).Inaddition,thereductionin automotivefrictionandimprovementsinthewearresistanceofautomotivecomponents hasledtothemedianageofautomobilesontheroadincreasingfrom5.1yearsin1969 to11.6yearsin2016(BureauofTransportationStatistics2017).

AsshowninFigure1.1,automotivefrictionallossescomefrom

• thefrictionwithintheengine,

• thefrictionwithinthetransmissionsystem,

• therollingresistanceandtractionofthetiresagainsttheroad,and

• thefrictionduringbraking.

Eventhoughautomobilespoweredbyinternalcombustionhavebeenaroundforover acentury,theautomotiveindustrystillcontinuestofindwaystolowerfrictionlosses

Figure1.1 Breakdownofhowthefuelenergyintheaveragepassengercarisusedanddissipatedasit isconvertedintousefulworktomovethecar.ReproducedfromHolmbergetal.(2012)withpermission fromElsevier,copyright2012.

Figure1.2 Improvementinfuelefficiencyduetothereductioninenginefrictionachievedthrough changesinengineoilsforgasolinefueled(GF)vehicles.GF-1toGF-5engineoilspecificationscorrespond tochangesinbaseoilandadditivechemistry.Reducingtheoilviscosityfrom5W-30to5W-20provides anadditional0.5%improvement.ThebaselineisEnergyConservingIIengineoilsavailablepriorto 1993.CourtesyofArupGangopadhyayatFordPowertrainResearchandAdvancedEngineering.

inautomotivepowertrainsandtires.AnexampleofthisisshowninFigure1.2,which illustratestheimpactthatimprovedengineoilshavehadonfuelefficiency.From1993 to2010,changesinengineoil,includingreducingtheirviscosity,resultedina1.6% improvementinfuelefficiencythroughthereductionofnon-viscousenginefriction. Alongwiththeimprovementinfueleconomy,thesenewerengineoilsalsoachieve higherwearprotection,higherresistancetooxidation,andlessformationofsludgeand varnishwithintheengines.Overthe1993–2006period,anadditional1%improvement inautomotivefuelefficiencywasachievedbyusinglowerviscositytransmissionfluids andanother1%byusinglowerviscositygearlubricant(Gangopadhyay2006).

Duetothedesiretoreducethetransportationsector’scontributiontoglobalCO2 emissions,theautomotiveindustrycontinuestostrivetoimprovefueleconomy,with furtherreductioninautomotivefrictionstillexpectedtobeanimportantcontributorto thisgoal.Theamountofpossiblegainsinfueleconomythatcouldpotentiallybeachieved byreducingfrictionhasbeenanalyzedbyHolmbergetal.(2012),whoestimatethat frictioncouldbereducedbyupwardsof18%ifonecouldbuildacaroutofcomponents withfrictioncoefficientsaslowasthelowestdemonstratedinresearchlabs.

A2017reporttotheU.S.DepartmentofEnergy(DOE;LeeandCarpick2017, Chapter2)discussesawidevarietyoftechnologicalopportunitiesforfurtherimproving fueleconomyrelatedtotribology.Theseincludefurtherimprovingengineanddrivetrain lubricants,optimizingcomponentdesign(e.g.,throughthinfilmcoatingsandsurface

finishesofparts,orimprovingthedesignofpistons),designinglubricantsintandem withtheengineanddrivetrain,incorporatingadvancedenginesensingandactuation, improvingcomputationally-aideddesignandmodeling,anddevelopingadvancedcoatings,finishesandlubricants.ThisDOEreport“estimatesthatcontinuedeffortsinthis area...couldeasilyachieve2–5%additionalfueleconomygains.”

1.2.2Tribologysuccessstory#2:solvingadhesionin MEMSdevices

Ithaslongbeenrealizedthatminiaturizationofmachinescanresultinmajornewtechnologies.Inrecentyears,themostpromisingwayforfabricatingmicroscalemechanical deviceshasbeentouseprocessesoriginallydevelopedforfabricatingsemiconductor electronicdevices.Byusingthesefabricationprocesses,mechanicalfunctions(such asactuation,fluidflow,thermalresponse,etc.)canbeintegratedonasmallarea ofachipalongwithelectronicsignalprocessing.Amajoradvantageoffabricating these microelectromechanicalsystems (MEMS)withsemiconductorprocessingtechniques isthattheyachieveexcellenteconomiesofscale,sincemanydevicesarefabricated simultaneouslyontoasinglechip.Thislowunitcost,alongwiththeintegrationof mechanicalandelectricalfunctionsintoasmallspace,enableswholenewtypesof technologiestobecomecommerciallyviable.

MEMSdevicescanbecategorizedasfollowsbasedonhowtheirmechanicalconstituentsmoveandcontact(Romigetal.2003):

• ClassI—nomovingparts(e.g.,pressuresensors,inkjetprinterheads,andmicrophones);

• ClassII—movingparts,butnorubbingorimpactingsurfaces(e.g.,accelerometers, gyros,andradiofrequency(RF)oscillators);

• ClassIII—movingpartswithimpactingsurfaces,(e.g.,digitalmicromirrordevices (DMDs),RFcontactswitch);

• ClassIV—movingpartswithimpactingorrubbingsurfaces(e.g.,micromotors).

Theseclassesarelistedinorderofincreasingtribologycomplexity,whichtypically correspondstoanincreasingtendencyforfailurefromtribologicalphenomenasuchas adhesion,friction,mechanicalstress,wear,andfracture.MostoftheMEMSdevices thathavebeensuccessfullycommercializedbelongtoClassIandII,withonlyafewin ClassIII,andnoneinClassIV.Asthelackoftribologicalinteractionscontributesto higherreliability,thebestwaytoavoidatribologyreliabilityissueinaMEMSdeviceis todesignitsothatitmovesaslittleaspossibleandwithoutimpactingcontacts!

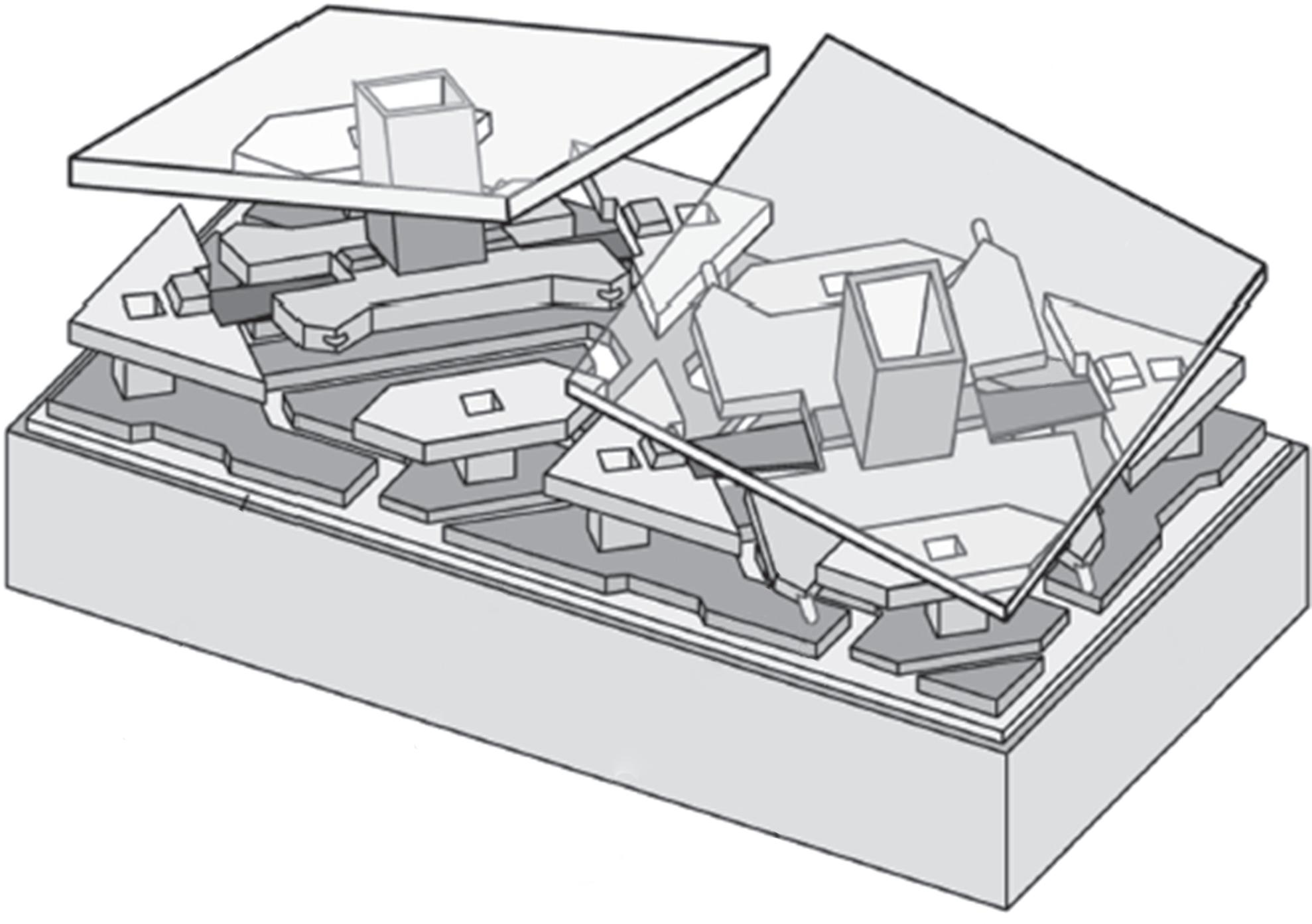

ThemostwidelyusedClassIIIMEMSdeviceistheDMD,developedbyTexas Instruments(TI)andusedindigitallightprocessing(DLP)videoprojectiondevices suchaslargescreentelevisions(Hornbeck2011).ThedevelopmentoftheDMD providesagoodsuccessstoryofhowsolvingmicroscaletribologyissuescanenable

Figure1.3 Twoofthemirrorsinadigitalmicromirrordevice(DMD).Electrostaticattractionisused torotatethemirrors ±10◦ tothemechanicalstopswherethespringtipsmakecontact.Reprintedfrom Hornbeck(2011)withpermissionfromCambridgeUniversityPress,copyright2011.

anewtechnologytogainsufficientreliabilityforcommercialization.InaDMD,an arrayofmirrors,eachabout16 μmacross,isusedtoprojectanimageontoavideo screen.AsillustratedinFigure1.3,theintensityofeachpixeliscontrolledbyrotatingthe individualmicromirrorsthrough ±10◦ byusingelectrostaticattraction.Beforeshipping itsfirstDMDproductin1996,TIcarriedoutextensivereliabilityengineeringand testing(Douglass1998,VanKesseletal.1998),andanumberofreliabilityissueswere addressed:stuckmirrors,fatigueofthemirrorhinge,excessivehysteresisinhingedeflection,mirrorsbreakingasresultofvibrationandshock,andparticlespreventingmirrors fromrotating.Herewefocusonthestickingofthemirrorsagainsttheirmechanicalstop, whichwasapersistenttribologyproblemforwhichtheTIengineersimplementedacombinationofcleversolutionsbasedonathoroughmicro-understandingoftheadhesive mechanism.

InaDMD,theindividualmicromirrorsarerotatedfromtheontooffpositions.To ensurethateachmirrorhasthecorrectangularpositionattheendoftherotation,the mirroryokeisdesignedtocometorestagainstamechanicalstop,asillustratedinFigure 1.3.DuringthedevelopmentoftheDMD,itwasfoundthatadhesiveforcesactingatthis contactwouldsometimesbelargeenoughtoresultinthemirrorstickingagainstthestop, makingitnon-functional.Theseadhesiveforcesoriginatefromthemeniscusforcedue towatervaporcondensingaroundthecontact(discussedinChapter6)andfromvander Waalsforces(discussedinChapter7).Anumberofdesignchangeswereimplemented intheDMDtoreducethemagnitudeoftheseadhesiveforcesandtoimprovetherelease function:

CMOS memory substrate

Spring tip

Yoke Metal 3

Mirror –10°

Mirror +10°

CMP oxide

• TheDMDwashermeticallysealedinadryenvironmenttominimizethecapillary condensationofwater.

• Thecontactingpartswerecoveredwithalowsurfaceenergy“anti-stick”material tominimizethevanderWaalsforce.

• Miniaturespringswereaddedtothepartsofthemirroryokethatmakescontact— the“springtips”showninFigure1.3.Thesespringtipsstoreelasticenergywhen thepartscomeintocontact,whichhelpspushthemirrorawayfromthesurface whentheelectrostaticattractiveforceisreleased.

Thesedesignmodificationsdramaticallyreducedthetendencyofthemicromirrors tostick,greatlyimprovingtheDMDoperatingmargins(Douglass1998,VanKessel etal.1998).From1996to2010,TIsoldover20millionDLPsystemswithDMDs, demonstratingthat,whenproperattentionispaidtothemicroscaletribologyissues,a reliableproductcanincludeaMEMSdevicewithcontactingcomponents.

TheRFMEMSswitchisanotherClassIIIMEMSdevicethatwasfirstcommercializedbyAnalogDevices.TheseMEMSdevicesuseaconductivegoldcantilever thatispulledbyelectrostaticforcesintocontactwithanotherelectrode,therebyclosing anelectronicpathforRFconductivity(Gogginetal.2015).Thesmallsizeofthe MEMSswitchisnotonlybeneficialintermsofspaceandweight,butalsoconsumes farlesspowerthanlargerconventionalswitches,aswellasprovidinganumberofother improvementsinelectricalperformance(Rebeiz2004).

InitialattemptstocommercializeMEMSswitcheswereunsuccessfullargelydueto tribologicalreliabilityissuesofthecontact,whichmustsurvivebillionsofswitching cyclestobecommerciallyviable.Byengineeringthepackagingenvironmenttoinclude hermeticsealingtopreventcontaminationandelectrostaticchargingfromtheenvironmentandbydevelopingmaterialsatthecontactjunctionthatminimizedwearand adhesion,AnalogDeviceswasabletoproduceareliablecommercialdevice.

AsdiscussedinSection1.4.2,miniaturizationofMEMScontactswitchestohave sub-100nmfeaturesizes(ananoelectromechanicalcontactswitch)isbeingdeveloped asanewtechnologyforpotentiallycompetingwithcomplementarymetal–oxidesemiconductor(CMOS)transistors,oncethereliabilityissuesassociatedwiththerepeated contactandthemanufacturingissuescanbesolved.

ForClassIVMEMSdeviceswheresurfacesrubagainsteachother,solvingthe tribologyissuesismuchmorechallenging(WilliamsandLe2006,AchantaandCelis 2015).Forexample,muchfanfarewasmadeaboutthefirstworkingMEMSmicromotor in1988(Fanetal.1989).Whilethesemicromotorsrotatedasdesired,therotors needtosupportedbyabearingthatistypicallymadebysiliconmicrofabrication technologies;thistypicallyresultsinthecontactingsurfaceshavinghighfrictionand wear,severelylimitingthereliabilitylifetimesofthemicromotor.Whilemicromotors havebeendemonstratedwithalowfrictionliquidbearing,agas-lubricatedbearing,a contactlessmagneticbearing,andanelectrostaticbearing(Shearwoodetal.2000,Wong etal.2004,Chanetal.2012,Sunetal.2016),micromotorswithsufficientreliabilityfor commercializationstillhavenotbeendemonstrated.

1.2.3Tribologysuccessstory#3:slider–diskinterfaces

indiskdrives

Theharddiskdrive(HDD)industrymaybethemoststrikingexampleofwherean exponentialimprovementofatechnologyovermanydecadeshasbeensustainedthrough thecontinualsolvingoftribologicalproblems.

Thefirstdiskdrivewasintroducedin1956aspartoftheIBMRAMACcomputer. TheRAMACdiskdrivestoredanimpressive4.4megabytes,foritsday,inaspacethe sizeofasmallrefrigerator.Diskdrivetechnologyhasadvancedtothepointthataterabyte ormoreofdatacannowbestoredonanHDDinalaptopcomputer.Thistremendous increaseinstoragecapacityhascomeaboutlargelyfromtheexponentialgrowthinthe arealstoragedensity(thenumberofbitsthatcanbestoredpersquareinchonadisk surface):from1956to2018,thearealstoragedensityofdiskdrivesincreasedbyafactor of107 ,withthedensityannualgrowthraterangingfrom30to100%.Tosustainthis tremendousgrowthinarealdensityoveraperiodoftimespanningmanydecades,all aspectsofdiskdrivetechnologyhadtobecontinuallyimproved.Herewefocusonthe tribologicalchallengesfacedbythediskdriveindustryintherecentpasttosustainthis rapidriseinarealstoragedensity.

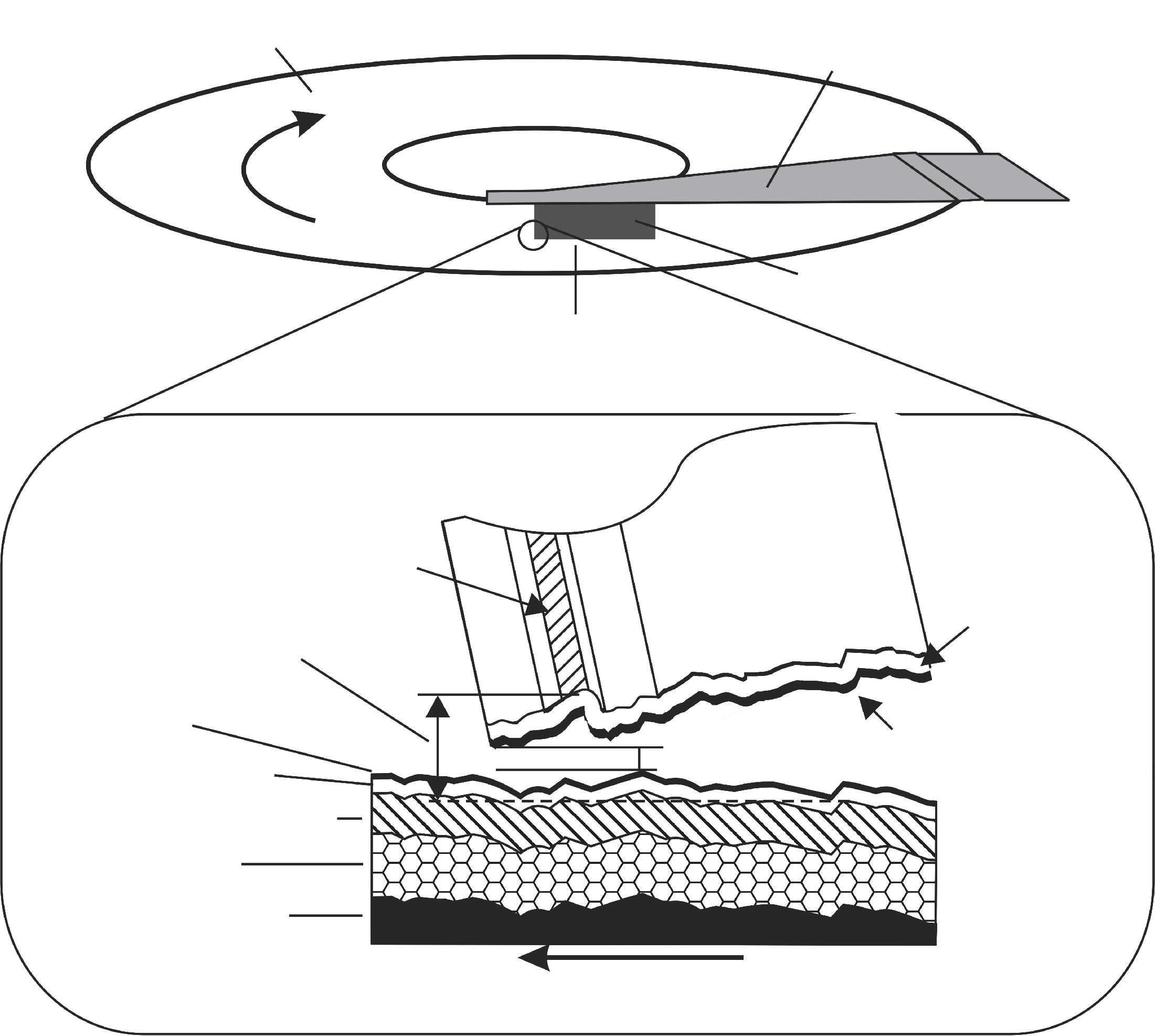

Insideadiskdrive,asliderawithread/writerecordingheadfliesoverarotatingdisk, asillustratedinFigure1.4.Theinformationisstoredasmagneticbitsinathinlayerof magneticmaterialonthedisksurface.Sincethemagneticfieldfromthesebitsdecays rapidlyawayfromthediskmagneticmediumwithadecaydistancethatscaleswithbit size,themagneticspacingbetweentheheadsensorandthemagneticmediumonthe diskneedstoscalewiththelateralsizeofthemagneticbitonthedisk(Marchonand Olson2009):so,asthearealdensitygoesup,thespacingmustgodown.

Sincetherecordingheadsliderfliesathighspeeds(typicallyaround10m/s)witha clearanceofjustafewnanometersoverthedisksurface,carefulattentionneedstobe paidduringtheproductdevelopmentandmanufacturetowardsminimizingtherisks fromhighspeedcontactsbetweentheslideranddisk.Tominimizethenumberofthese contacts,thesliderisdesignedtoflyonanairbearinggeneratedbythediskpullingair underneaththesliderandoveraseriesofstepsandpocketspreciselyfabricatedonto thebottomsurfaceoftheslider.Thesesurfacefeaturesformanairbearingsurface (ABS)thatgeneratesaliftingforce,whichbalancestheloadingforcefromthesuspension enablingtheslidertoflyoverthediskwithitstrailingedgeafewnanometersabovedisk surface.Toprotectagainstoccasionalimpacts,thediskandslidersurfacesarecoated (about3–4nmfor2005drives)withahardmaterial,usuallydiamond-likecarbon.To furtherensurethattheslider–diskinterfaceisnotdamagedbythehighspeedimpacts,a molecularlythinfilmoflubricant(typicallyabout1nmthick)isappliedoverthecarbon overcoateddisk.

Eventhoughthespaceavailablebetweentheheadsensorandthediskmagnetic layerfortheseprotectivelayershasbeenrapidlydiminishing,thedramaticreduction inmagneticspacingfrom96nmin1995to~10nmin2013(Marchonetal.2013)was notachievedthroughanymajortechnologicalinnovations,butratherthroughcareful attentiontotribologicaldetail,inparticular:

Rotating disk

Suspension load beam Slider

Recording head sensors

Magnetic spacing

Lubricant

Disk overcoat

Magnetic medium

Underlayer

Disk substrate

Trailing edge of slider Head overcoat

Air bearing surface (ABS) Clearance 5–50 m/s

Figure1.4 Arecordingheadsliderflyingoverarotatingdisksurfaceinadiskdrive(top).Anenlarged viewofthetrailingedgeofthesliderwheretherecordingheadislocated(bottom).Thecrosssection illustratesthevariouscomponentsoftherecordingheadanddiskthatcontributetothemagnetic spacing,whichisdefinedasthedistancefromthetopofthediskmagneticmediumtothebottomofthe headsensor.Thehigherthearealstoragedensity,thesmallerthemagneticspacingneedstobe.

• introductionofdensercarbonovercoatsthroughchangesincompositionand depositionprocesses;

• designoflubricantsystemsthatpreserveatleastamonolayeroflubricantondisk surfacesoveradiskdrive’slifetime(Mate2013);

• carefulcontrolofdisktopographytoachievesub-nanometerroughness(seeSection 2.4.3.1);

• improvedfabricationprocessesandbettertolerancecontrolforthesliderABS, resultinginbettercontroloftheslider–diskspacing;

• developmentof“flyingheightcontrol”whereasmallheaterisintegratedintothe recordingheadtoactivelycontrolthefinaloftheslider–diskclearance(Suketal. 2005,Mateetal.2015).

Withtheseimprovements,diskdrivesachieveexcellentlongtermreliabilitywhiletheir slidersflyoverthedisksurfacesathighspeedswithincrediblysmallclearances,~1.5 nmfor2013drives(Marchonetal.2013).Thediskdriveindustryplanstocontinue

increasingarealstoragedensities,whichwillmeanreducingthemagneticspacingto lessthan7nm(Wood2000,Mateetal.2005,Marchonetal.2013).However,the variousconstituentsofthemagnetic—overcoats,lubricant,roughness,andclearance— areapproachingtheirphysicallimitsastohowthintheycanbemadeandstillprovide thedesiredlevelofprotection(Mateetal.2005,Marchonetal.2013).Thiswillproveto beparticularlychallengingforthetwonewtechnologiesthatindustryhasbeenintensely developingforachievingfutureincreasesinarealdensity:

• Heatassistedmagneticrecording(HAMR)—InHAMR,asmalllaserandwaveguide areincorporatedintotherecordingheadandareusedtobrieflyspot-heatatiny areaofthedisksurfaceduringtherecordingwriteprocess.Themagneticmediain thisareaistemporarilyheatedabovetheCurietemperature,makingitpossibleto writeanindividualmagneticbitthatisonlyafewnanometersacross(Shiroishietal. 2009).Sincethemagneticmediaisheatedlocallyto >400◦ CduringtheHAMR writeprocess,thishightemperaturecannegativelyimpactthediskdrivetribology bythermallydegradingthecarbonovercoatandlubricant,andbycreatingthermal protrusionsontheheadanddisksurfacesthatgreatlyincreasethefrequencyand severityofintermittentcontacts(Marchonetal.2014,Kielyetal.2018).

• Bitpatternedmedia(BPM)—InBPM,ratherthanstoringthebitsasmagnetic domainsinacontinuousmagneticmediaasisconventionallydone,eachbit isstoredonasmallislandofmagneticmaterial.Theweakmagneticcoupling betweenneighboringislandsmakesitispossibletopackmorebitsintoaunit areainBPMthanwithcontinuousmedia.Thepatterningprocesstofabricatea BPMdisk,however,createsinamuchrougherdisksurfacethanforconventional continuousmedia,makingitdifficultfortherecordingheadslidertoflyoverthe diskwithoutexcessivewearatasmallenoughmagneticspacingtotakeadvantage oftheincreasedarealdensity(Albrechtetal.2015).

1.3Abriefhistoryofmoderntribology

Thepracticeoftribologygoesasfarbackastheprehistorichumans,whofirstusedwear tofashiontoolsandfrictiontostartfires.AncientEgyptianartworkfrom4000years agoshowsslavesdraggingofsledgesbearingheavystatuesandincludesthedepictionof anearliertribologistpouringaliquidattheslidinginterfacetoreducefriction(Dowson 1998,Ayrinhac2016).InChina’sForbiddenCity,thehugestonesthereareconjectured tohavebeentransportedinthefifteenthandsixteenthcenturiesbyslidingthemoveran icepath(Lietal.2013).

ScientificinvestigationoffrictionbeganwithLeonardodaVinciwhorecordedin hisnotebookstheobservationthatfrictionwasproportionaltoloadandindependent oftheapparentareaofcontact.ThislawoffrictionwasrediscoveredbytheFrench physicistGuillaumeAmontons,whopublishedhisfindings,nowreferredtoAmontons’ LawsofFriction,in1699.Amontons’resultsimmediatelyprovokedcontroversyabout

themicroscopicoriginsoffriction,whicheventodayhasnotbeenfullyresolved.The possibleoriginsoffrictionarediscussedinChapter4and11.

Withtheindustrialrevolution,machineryofallsortscameintowidespreaduse andwithitagrowingneedforabettercontroloffriction,lubrication,andwear. Duringthisperiod,theprinciplesofhydrodynamiclubricationwerefirstdiscovered throughtheexperimentalworkofBeauchampTower(1884)andthetheoreticalworkof OsborneReynolds(1886).Thesubsequentdevelopmentofthistheoryofhydrodynamic lubricationenabledreliablebearingstobedesignedforlubricatingthemachineryofthe modernage.LubricationisdiscussedinChapters9and10.

Duringthetwentiethcentury,enormousindustrialgrowthanddevelopmentofnew technologiesfurtherfueleddemandforbettertribology.Tomeetthisdemand,numerous tribologicalengineeringsolutionshavebeendevelopedoverthelastcentury,notably:

• hydrodynamicbearingdesign(Chapter9);

• theoryofcontactmechanics(Chapter3);

• syntheticlubricants;

• solidlubricants;

• wear-resistantmaterials.

Ithaslongbeenthoughtthatalackofunderstandingofthemicroscopicoriginsof tribologicalphenomenahasimpededthedevelopmentofthebesttribologytechnology. Inthemiddleofthetwentiethcentury,severalscientistsconductedpioneeringstudies onthemicroscopicoriginsoffriction,lubrication,andwearproducing:

• 1925—Hardy’sstudiesofboundarylubrication(Chapter10)

• 1940s—BowdenandTabor’stheoryofmolecularadhesionforfriction(Chapter4 and11)

• 1953—Archard’slawforadhesivewear(Chapter12)

• 1966—GreenwoodandWilliamson’sanalysisofmulti-asperitycontactarea (Chapter3)

Sincethelatterpartofthetwentiethcenturytherehasbeenanacceleratedeffortto determinethemicro-toatomicscaleoriginsoftribologyphenomena.Besidesthedesire toreducedetrimentalfrictionandwearintechnologicalapplications,thisefforthasalso beendrivenbynewexperimentalandtheoreticaltechniquesforcharacterizingmaterials atthenanometerscale,facilitatingthediscoveryoftheatomicandmolecularoriginsof friction,lubrication,adhesion,andwear.Thisemergingsubfieldoftribologyhasbeen christened nanotribology asitseekstounderstandtribologyphenomenaattheatomicand nanometerscale.

1.3.1Scientificadvancesenablingnanotribology

Thenatureofcontactmakesitsmicroscopicandnanoscopicoriginsdifficulttostudy. Generallycontactoccursatamultitudeofcontactzonesattheapexesofsmall

protrusionsorasperitiesonopposingsurfaces,asillustratedinFigure1.5(a).Since thesecontactsaresandwichedbetweentwosolids,theyareinaccessibletomostscientific characterizationtechniques.Addingtothisdifficulty,thecontactoccursprincipallyatthe summitsofthesurfaceroughness,meaningthatthematerialvolumeaffectedbycontact tendstobenanoscopicallysmallanddifficulttodetect.Thepushandpulloftheasperities rubbingagainsteachotherfurthercomplicatesmattersasthecontactingmicrostructures arenotstaticbutevolveasslidingprogresses.

Fortunately,numeroustechniqueshavebeendevelopedoverthepasthalfcentury forcharacterizingsurfacesandnanoscaleamountsofmaterials.Thesenewertechniques haveledtoawealthofinformationonhowthestructureandchemistryofsurfacesevolve duringcontactandhowtheyinfluencetribologicalphenomena.

Foronecategoryofsurfaceanalyticaltechniques(illustratedinFigure1.5(b)),the individualsurfacesareplacedinhighvacuumandirradiatedwithelectrons,ions,or X-rays,andthekineticenergyoftheejectedelectronsorionsaremeasuredwithan energyanalyzer.Sinceonlyelectronsorionsnearthesurfacecanbeejectedtoward

Figure1.5 (a)Duetosurfaceroughness,contactbetweentwosolidsurfacesoccursprimarilyatthe summitsofthesurfaceasperities.(b)Vacuumtechniquesforanalyzingsurfacesbeforeoraftercontact. AES:impingingelectrons,energyofejectedelectronsanalyzed;ESCA/XPSorXAS:impingingX-rays, energyofejectedelectronsanalyzed;SIMS:impingingions,energyandcharge-to-massratioofscattered andejectedionsmeasured.(c)OpticaltechniqueslikeRamanspectroscopy,fluorescencespectroscopy, surfaceplasmonresonance,FTIR,andsumfrequencygenerationcannowbeusedtoanalyzeaburied contactinterface.(d)AnAFMtiprubbingagainstasurfacecanbeusedtosimulateasingleasperity contact.

Electron energy analyzer or ion detector

Photodector or spectrum analyzer

AFM cantilever

Incominglight

(a)

(b)

Tip

(c)

(d)

thedetector,theseareverysensitivetechniquesfordeterminingsurfacestructureand chemistry,butthenecessityofvacuumoperationmeansthesetechniquesareonlyused foranalyzingsurfacesbeforeandaftercontact.Someofthevacuumtechniquesvaluable forcharacterizingthechemicalcompositionandmolecularstructureoftribological surfacesinclude:

• Augerelectronspectroscopy(AES);

• electronspectroscopyforchemicalanalysis(ESCA),alsoknownasX-rayphotoelectronspectroscopy(XPS);

• X-rayabsorptionspectroscopy(XAS);

• secondaryionmassspectrometry(SIMS).

FullerdescriptionsofthesetechniquescanbefoundinBriggsandSeah(1990)and Somorjai(1994,1998).

AsillustratedinFigure1.5(c),severalopticalandX-rayprobeshavebeendeveloped thatallowforinsitucharacterizationoftheburiedcontactingsurfaces:

• Fouriertransforminfrared(FTIR)spectroscopy(Mangolinietal.2012);

• fluorescencemicroscopy(McGheeetal.2018);

• surfaceplasmonresonancespectroscopy(Kricketal.2013);

• Ramanspectroscopy(CampionandKambhampati1998,Wahletal.2007);

• sumfrequencygeneration(Shen1994);

• X-raydiffractionandX-rayreflectivity(Mateetal.2000).

Forareviewoftheseandothertechniquesusedtostudyburiedtribologicalinterfaces, seeSawyerandWahl(2008).

Sincecontacttypicallyoccursatthesummitsofasperities,characterizingthetopographyofcontactingsurfaceshasalwaysbeenanimportantstartingpointforcharacterizing atribologicalsurface.Initiallythiswasdonewithstylusprofilometersthatonlymeasured profileswithmicronresolutionalongsinglelines.Nextcamethescanningelectronmicroscope(SEM),whichiscapableofimagingsurfaceswithnanometerlateralresolution,but isunabletoquantifytheheightsofthesurfacefeatures.Opticalinterferometryprovides veryhighverticalresolution,butislimitedbydiffractionto~1μminthelateraldirections. Morerecently,surfacetopographymeasurementshavebeendominatedbyscanning probetechniques—thescanningtunnelingmicroscope(STM)and,moreimportantly, theatomicforcemicroscope(AFM)—whichcangeneratethree-dimensionaltopography imageswithtrueatomicresolution.TheuseofopticalinterferometryandtheAFMfor topographymeasurementsisdiscussedinChapter2.

Inadditiontotopographymeasurements,theAFMisalsoabletomeasurethecontact forcesactingonasingleasperitytip,asillustratedinFigure1.5(d).Consequently,since itsinventionin1986,theAFMhasbecomeoneoftheprincipaltoolsforinvestigating

15 nanoscalecontactandfrictionforces.UseoftheAFMformeasuringcontactforcesis discussedinChapters6,7,8,10,and11.

Thesurfaceforceapparatus(SFA)isanotherimportanttoolformeasuringtheforces betweencontactingsurfaces;inanSFA,theforcesaremeasuredbetweentwoatomically smoothmicasheetsinavarietyofchemicalenvironments.SFAforcemeasurementsare discussedinChapters7,8,and10.

Thedramaticincreaseincomputerperformanceoverthepastfewdecadeshasledto theprevalenceofmanycomputer-basedsimulationtechniquesforpredictingphysical phenomena.Severalofthesesimulationtechniqueshavebeenadaptedtostudying tribologicalphenomena:

• Moleculardynamicssimulationshavebeenusedtodirectlyaddresstheatomic originsoffriction,lubrication,andadhesion,butarelimitedtosmallvolumesand shorttimescales(ThompsonandRobbins1990,Heetal.1999,Gaoetal.2004, Dongetal.2013).

• Finiteelementanalysissimulationsareroutinelyusedtoanalyzethecontact mechanicsofmacro-,micro-,andnanoscalemulti-asperitycontacts.

• Mostmodernfluidfilmbearingsaredesignedusingcomputeraideddesign(CAD) software.Inmanyinstances,analysisprogramshavebeendevelopedtohandle bearingswithsub-microndimensions.

1.4Breakthroughtechnologiesrelyingontribologyatthe smallscale

Perhapsthemostexcitingaspectofmoderntribology’spushtowardsthenanoscaleis thepotentialpayoffthatthisresearchcanhaveforenablingbreakthroughmicro-and nanoscaletechnologies.

Asdevicecomponentsminiaturize,theybecomemoresusceptibletotheforcesand toatomicscalephenomenaoccurringattheircontactingsurfaces.Asaconsequence, establishedengineeringsolutionsthatmightworkwellformacro-tribologysituations tendtobeinadequateformicro-andnanoscaledevices.

Forexample,formacroscopicmachines,fluidfilmbearingsareusedtoprovide lubricationforthemovingparts.Thethicknessofthelubricantfilminthesebearingsis typicallymicronstomillimeters;but,whendevicesareminiaturizedtothesub-millimeter scale,thegapbetweenthemovingpartsofthebearing’slubricantfilmbecomessubmicron.Thissmallgapleadstomorefrequentcontactbetweentheasperitiesonthe movingsurfaces,aswellastoconfinementeffectswithinthelubricantfilmthatcan dramaticallyincreasethelubricant’sviscosity.Boththefrictionandwearfromcontact andtheenhancedviscositycanreducethebearing’seffectivenessifthebearingisnot properlyredesignedforthesmallscale.

Further,asmachinesbecomemicro-sized,thecapillaryandmolecularadhesionforces begintodominateovergravityandinertiaforces.So,whileloadingforcesandbulk

hardnessmaybethemajorfactorsdeterminingfrictionandwearofmacro-sizedobjects runningincontact,theybecomerelativelylessimportantforminuteobjectswhere molecularadhesionforcesarecomparabletoloadingforces.

Previously,wediscussedthetwoexamplesoftheDMDsanddiskdriveswhere successfulproductswereshippedoncesolutionswerefoundtotheproblemsassociated withmicro-andnanoscaletribology.Inthenextfewsections,wediscussafewexciting newtechnologieswhereimplementationisbeingheldupbyproblemsoftribologyon thesmallscale.

1.4.1Nanoimprinting

Drivenbythedifficultiesandhightoolingcostsofextendingphotolithographytechniquestotheproductionofsub-100nmfeatures,atremendousresearcheffortis beingexpendedondevelopingalternativestophotolithographyforfabricatingnanoscale structures. Nanoimprinting isapromisingnewtechnologyforreplicatingfeaturesas smallas <10nminsizeand,duetoitslowcostandsimplicity,shouldbeanattractive alternativetonotonlyphotolithography,butalsotoe-beamlithographyandextreme UVlithography(EUVL)(Chouetal.1996,McClellandetal.2005,Schift2008,Traub etal.2016).

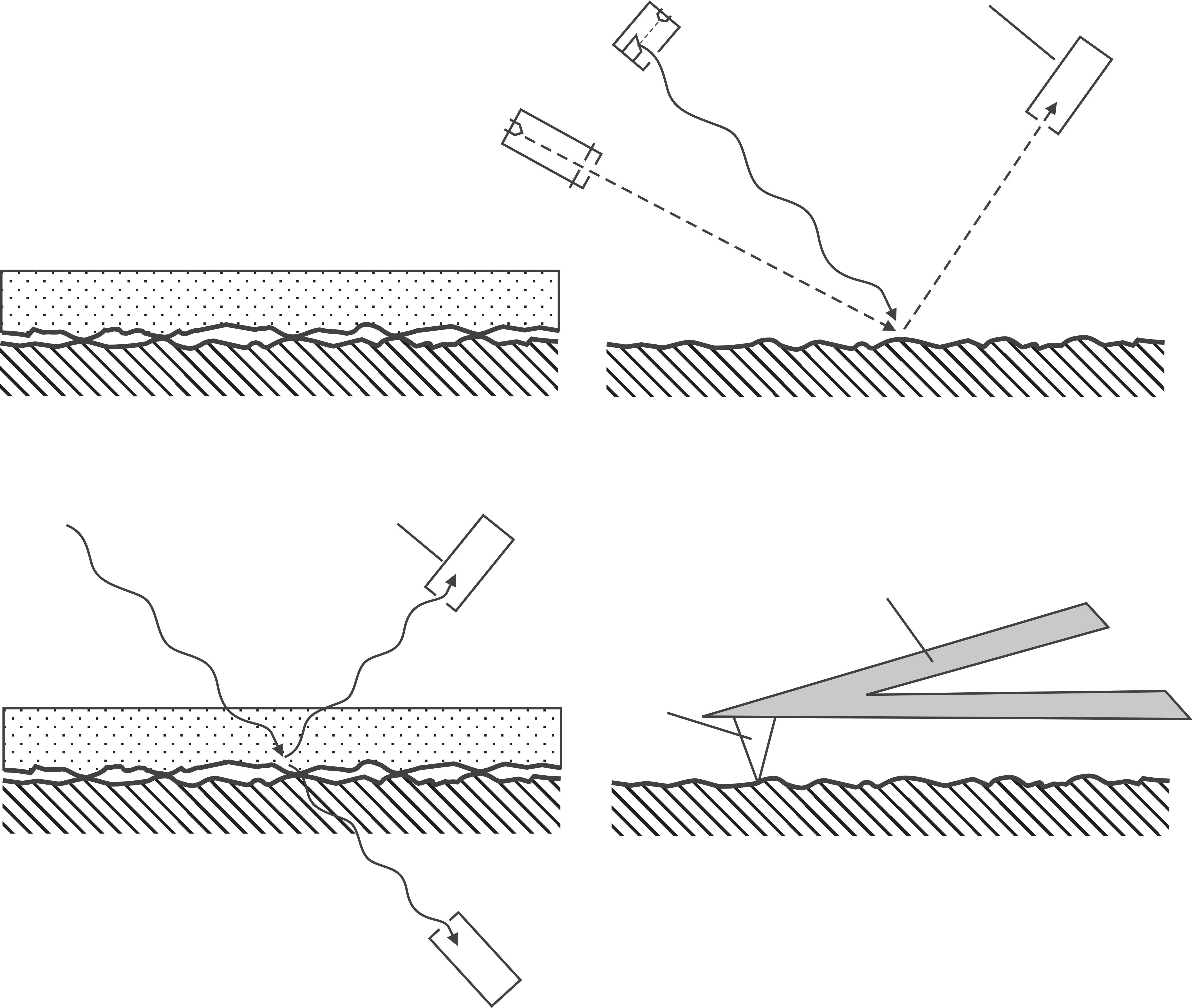

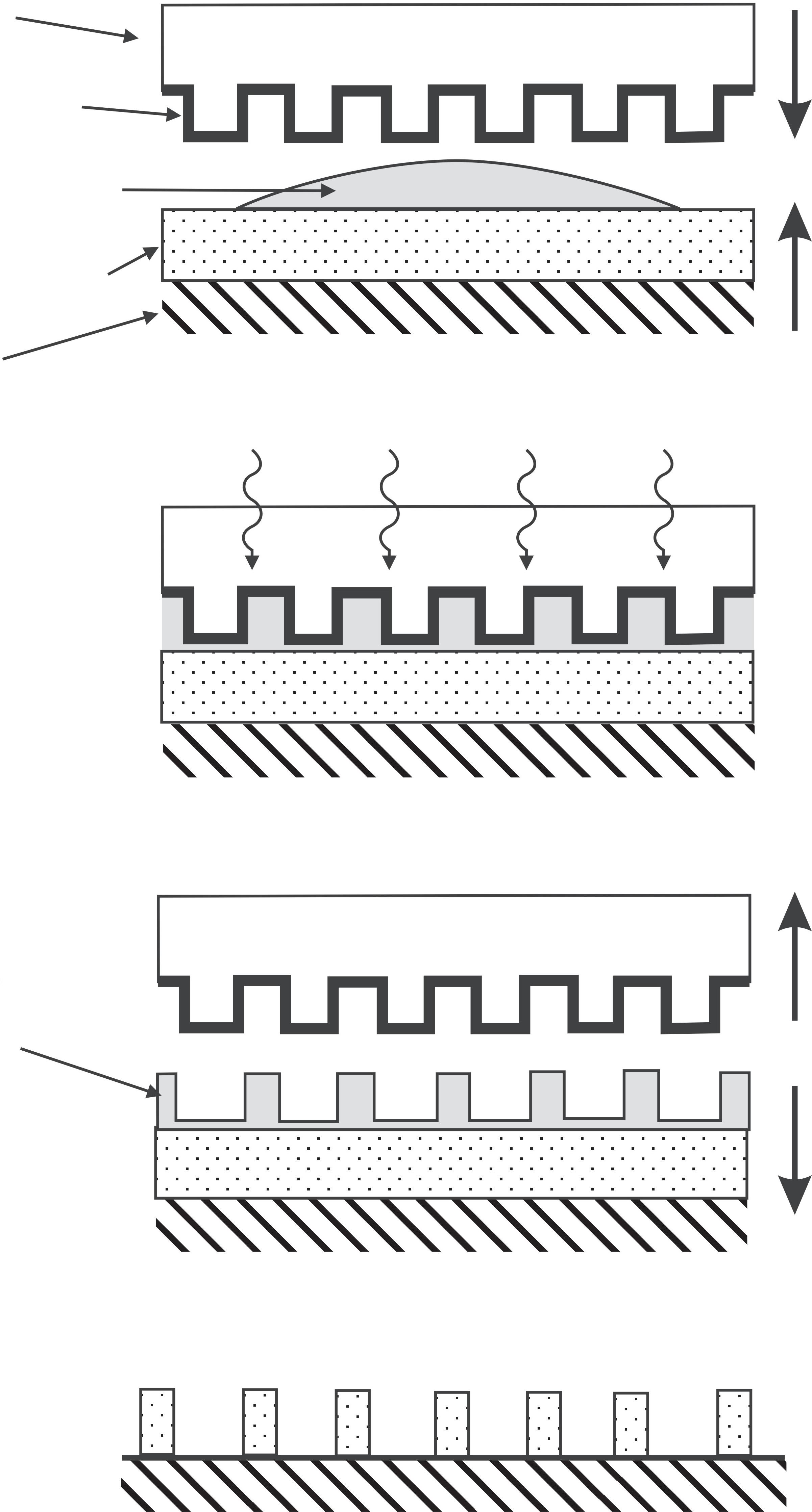

Figure1.6illustratesthetypicalUVnanoimprintlithography(UV-NIL)process.In thistechnique,atransparenttemplatestamp(usuallyquartz)isfirstfabricatedwith thesub-100nmfeaturesthataretheinverseofthestructurestobereplicated.Next, thetemplatestampisalignedoverthesubstrate,andalowviscosity,UV-curableresist materialisinjectedbetweenthem(Figure1.6(a)).Thetemplateandsubstratearepressed together,andtheresistexposedtoUVlightthroughthetemplate(Figure1.6(b)).The templatestampiswithdrawn,leavingthepatternreplicatedintheresistmaterial(Figure 1.6(c)).Finally,thispatternisetchedintothesubstratetocreateapermanentinverse replicaoftheoriginaltemplatepattern(Figure1.6(d)).

Thermalnanoimprintlithography(thermal-NIL)isanotherversionofnanoimprinting.ThismethoddiffersfromUV-NILinthatathermoplasticpolymerisusedasthe resistratherthanaUV-curablepolymer.Afterthethermoplasticpolymerisspin-coated ontothesubstrate,thetemplatestampispushedagainstthepolymerfilmastheyare heatedabovethepolymer’sglasstransitiontemperaturesothatthepolymer’sviscosityis lowenoughforittoflowaroundthetemplatefeatures.Afterthepolymerhascooleddown belowtheglasstransitiontemperature,thetemplateiswithdrawntoleaveapatterned resistreadyfortheetchstep.

Astheoldadagesays“thedevilisinthedetails”and,fornanoimprinting,avery criticaldetailisthelevelofdefectsgeneratedduringtheimprintprocess.Forexample,if featuresarespaced40nmapart,thiscorrespondstoadensityof6.25 × 1010 persquare centimeter.Sincethefeaturesareonlyafewtensofnanometersacross,evenfewcubic nanometersofmaterialgoingastrayeverynowandthencaneasilyadduptoanunacceptablenumberofdefects.Amajorproblemfacedinimplementingnanoimprintingas amanufacturingprocessisminimizingthesedefectstoanacceptablelevel.

Release layer

Uncured resist

Transfer layer

Substrate

Exposure to UV

Cured and patterned resist layer

Figure1.6 SchematicoftheUVnanoimprintlithographyprocess.(a)Alignmentofthetemplatestamp anddepositionofaUVcurableresistmaterialthatwillserveastheetchbarrier.(b)Imprintandexpose toUV.(c)Withdrawalofthetemplatestamp.(d)Afteretchingandremovaloftheresistmask,the substratehastheinversepatternofthetemplate.

ForananoimprintingprocesssuchastheoneillustratedinFigure1.6,therearetwo generalcategoriesofmechanismsthatgeneratetribologyrelateddefects:

1.Whenthetemplatestampandsubstratearepushedtogether,theuncuredresist materialneedstoflowaroundandwetallofthenanoscalefeaturesonthetemplate surface,asanyuncoveredportionbecomesadefectvoidinthereplicatedpattern. Thespreadingoftheuncuredmaterialintothenanoscalefeaturesonthetemplate surfacesisgovernedbytheflowofliquidsintightspaces,whichisdiscussedin Chapters9and10.WettingisdiscussedinChapter5.

2.Whenthetemplatestampiswithdrawn,ithastoseparatewithoutdamagingthe resistmaterial.AsdescribedbySchift(2008),thesewithdrawalrelateddefects include:

Figure1.7 Schematicsofhow,whenthenanoimprinttemplatestampiswithdrawnfromthecured resist,frictionandadhesiononthesidewallscanleadtoadefectbeinggeneratedinthepatternedresist structurebytheelongationofaresistfeature,followedbyitbecomingdetachedfromtheresistand adheringtothetemplatestamp.

• elongationofresistfeatureswiththepotentialtodetachthesefeatures(Figure1.7),

• delaminationofresistfromthesubstrate,

• shrinkageoftheresist,

• generationofrimsontheresistfeaturesduetosidemotionoftemplateduring withdrawal,and

• relaxationofstrainthatwasfrozenintotheresistduringcuring.

Figure1.7illustratesthefirstofthesewithdrawalrelatedmechanismswhereadefectis createdwhenapieceofcuredresistadheressostronglytothetemplateduringwithdrawal thatitelongatesanddetachesfromtherestoftheresist.Thisnotonlycreatesavoid defectforthatparticularreplica,butalsothisdefectcanpropagatetofuturereplicasif theadheredmaterialisnotcleanedoffthetemplatestamp.Acommonwaytoprevent thecuredresistfromadheringtothetemplatestampistocoatthestampsurfacewith athinfilm,calleda releaselayer,whichhasalowsurfaceenergy.Thisreleaselayeris typicallyonemoleculethick,asathickerfilmwouldadverselyimpactthedimensionsof thereplicatednanoscalefeaturesandathinnerfilmwouldprovideinadequatecoverage. Thereleaselayerworksbyloweringtheadhesionenergyactingovertheresist–template surfaceareabelowtheresist–resistandresist–substratecohesionenergy.Thephysical originsofandtheinterrelationshipsbetweenadhesionforceandsurfaceenergyare discussedinChapters5,6,and7.

Evenwithalowsurfaceenergyreleaselayer,properreleaseofthesmallestfeatures canbeproblematicashighfrictionforcesonthesidesofhighaspectratiofeatures candominateovercohesiveforceswithinthecuredresist,whichisalsoillustratedin Figure1.7.Thisoccursasthesurfaceareaofthefeaturesdoesnotscaledownas fastastheirvolume.Thiscombinationofthesurfaceforcesoffrictionandadhesion eventuallybecomeslargerthantheinternalcohesiveforcesasstructuralfeaturesare mademicroscopic.