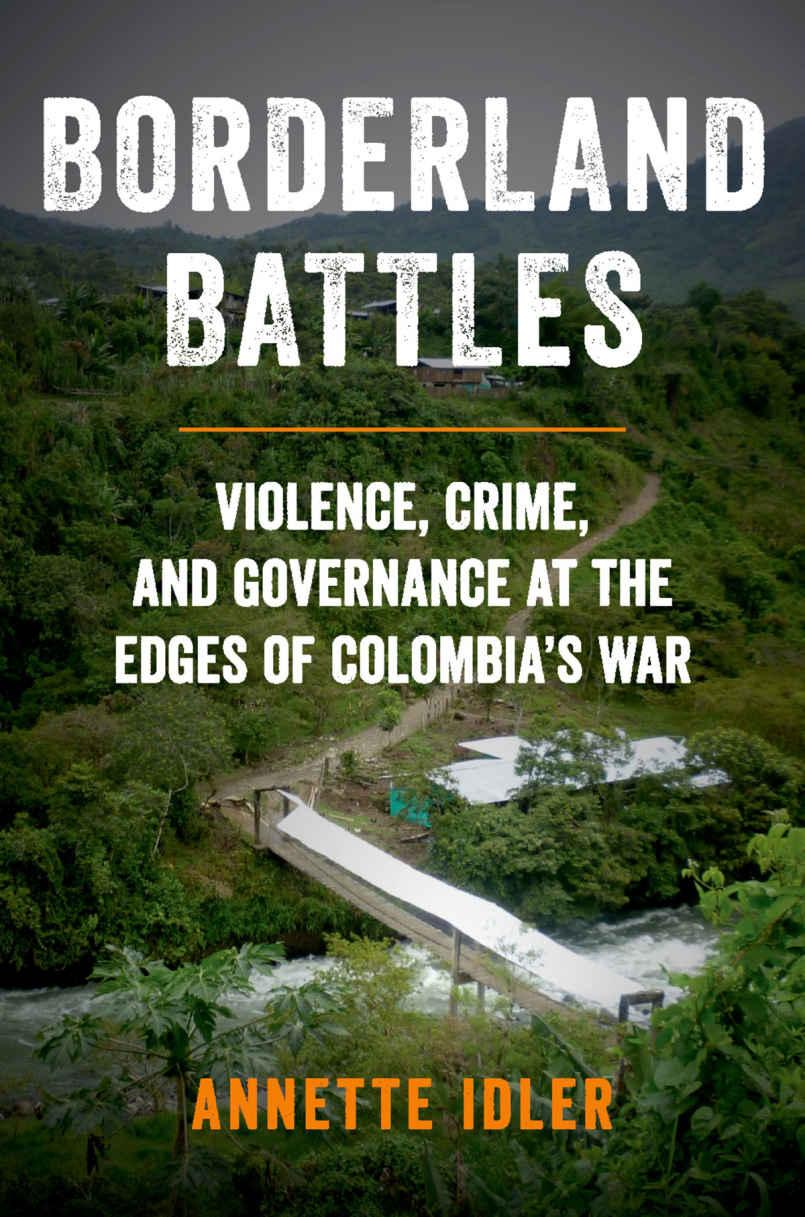

Borderland Battles

Violence, Crime, and Governance at the Edges of Colombia’s War

ANNETTE IDLER

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Idler, Annette, 1985– author.

Title: Borderland battles: violence, crime, and governance at the edges of Colombia’s war / Annette Idler.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018018370 | ISBN 9780190849146 (hard cover) | ISBN 9780190849153 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780190849160 (updf) | ISBN 9780190849177 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Border security—Colombia. | Violence—Colombia. | Insurgency—Colombia. | Crime—Colombia. | Colombia—Boundaries—Ecuador. | Ecuador—Boundaries—Colombia. | Colombia—Boundaries—Venezuela. | Venezuela—Boundaries—Colombia.

Classification: LCC HN310.Z9 V5349 2018 | DDC 355.02/1809861—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018018370

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

To my parents

CONTENTS

List of Tables, Figures, and Maps ix

Acknowledgments xiii

List of Abbreviations xvii

Prologue: Witnessing Insecurity from the Margins xix

Borderland Maps xxv

1. Borderlands: Security through a Magnifying Glass 1

1.1 FROM LOCAL SECURITY TO NON-STATE ORDER AROUND THE GLOBE 7

1.2 CONTRIBUTIONS TOWARD A TRANSFORMATIVE GOAL 23

2. Non- State Order and Security 31

2.1 NON-STATE ORDER 34

2.2 SECURITY 49

2.3 THE ROLE OF THE STATE AND THE REGIONAL CONTEXT 63

3. The Borderland Lens 66

3.1 BORDERS VIEWED FROM THE CENTERS 67

3.2 BORDERLANDS VIEWED FROM THE MARGINS 75

3.3 CONCLUSION 121

4. Violence and Survival 123

4.1 COMBAT 124

4.2 ARMED DISPUTES 146

4.3 TENSE CALM 154

4.4 CONCLUSION 157

5. Crime and Uncertainty 159

5.1 SPOT SALES AND BARTER AGREEMENTS 161

5.2 TACTICAL ALLIANCES 180

5.3 SUBCONTRACTUAL RELATIONSHIPS 203

5.4 CONCLUSION 208

6. Governance and Consent 211

6.1 SUPPLY CHAIN RELATIONSHIPS 212

6.2 STRATEGIC ALLIANCES 229

6.3 PACIFIC COEXISTENCE 233

6.4 PREPONDERANCE RELATIONS 238

6.5 CONCLUSION 247

7. The Border Effect 251

7.1 THE BORDER AS FACILITATOR 253

7.2 THE BORDER AS DETERRENT 271

7.3 THE BORDER AS MAGNET 278

7.4 THE BORDER AS DISGUISE 285

7.5 CONCLUSION 294

8. Global Borderlands: Security through a Kaleidoscope 296

8.1 BORDERLAND BATTLES FOR POSITIVE CHANGE 302

8.2 PUTTING THE MARGINALIZED CENTER STAGE 324

Epilogue: Experiencing Insecurity in the Margins 327

Appendix A: Further Methodological Notes 337

Appendix B: Violent Non-state Group Interactions across the Borderlands 351 Appendix C: Borderland Fieldwork Itineraries 357 Notes 367 Bibliography 423 Index 455

TABLES, FIGURES, AND MAPS

Tables

2.1 Non- State Order and Citizen Security 56

7.1 Border Effect on Violent Non- State Group Interactions and Citizen Security 252

A.1 Spread of Observations across Clusters and Sites 340

A.2 Spread of Selected Observations across Cases 341

A.3 Spread of Interviews across Stakeholders and Sites 347

B.1 Observations of Violent Non-state Group Interactions 352

Figures

2.1 The continuum of clusters of violent non-state group interactions 40

2.2 Citizen security 52

3.1 Homicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants in the Colombian-Ecuadorian and Colombian-Venezuelan borderlands 72

3.2 Percentage of coca cultivation in Colombian border departments, 2016 81

3.3 Plaza of Mocoa, Colombia, 2011 87

3.4 Border river between Colombian Putumayo and Ecuadorian Sucumbíos, 2012 88

3.5 Road between Pasto and Mocoa, Colombia, 2011 90

3.6 Border bridge San Miguel between Putumayo (Colombia) and Sucumbíos (Ecuador), 2012 92

3.7 Informal border crossing between Tufiño (Ecuador) and Mayasquer (Colombia), 2012 96

3.8 Road between Chical and Tulcán, Ecuador, 2012 100

3.9 San Lorenzo, Ecuador, 2012 103

3.10 Harbor of El Viento, Ecuador, 2012 103

3.11 Palma Real, Ecuador, 2012 103

3.12 Border closure at Arauca (Colombia) and Apure (Venezuela), 2016 106

3.13 Border post Boca del Grita, Venezuela, and international border bridge between Puerto Santander (Colombia) and Boca del Grita (Venezuela), 2012 114

3.14 Border police station Castilletes, La Guajira, Colombia, 2012 117

4.1 FARC pamphlet, September 21, 2004 131

4.2 FARC pamphlet, September 30, 2004 133

4.3 FARC pamphlet December 20, 2005 135

4.4 FARC pamphlet, December 2006 136

4.5 FARC pamphlet, April 30, 2007 138

4.6 Violent events, Arauca, Colombia, 2003–2012 139

4.7 Guerrilla graffiti in Arauca, Colombia, 2012 143

4.8 Pamphlet with threats in Ocaña, Colombia, 2012 156

5.1 Queue at gasoline station near San Antonio de Táchira, Venezuela, 2012 172

5.2 Typical car used for gasoline smuggling, Zulia, Venezuela, 2012 173

5.3 Pimpinas stall at the Colombia-Venezuela border, 2012 173

5.4 Funeral procession in Tumaco, Colombia, 2011 192

5.5 Shifting violent non-state group alliances in La Guajira, Colombia 195

6.1 Poor road infrastructure in Bajo Putumayo, Colombia, 2012 239

6.2 Community meeting in Arauca, Colombia, 2012 241

6.3 FARC pamphlet with warning against humanitarian agencies, 2012 245

7.1 Cocaine hideout: Mangroves on the Pacific Coast, 2012 263

7.2 Unofficial border bridge between Carchi (Ecuador) and Nariño (Colombia), 2012 268

7.3 Pamphlet against the “Criminals of the FARC”, 2012 287

8.1 Bullet holes after FARC’s attack on the Colombian army, near Majayura, Colombia, 2016 299

8.2 FARC peace banner in Nariño, Colombia, 2016 324

8.3 House with cacao plant painting in Arauca, Colombia, 2012 325

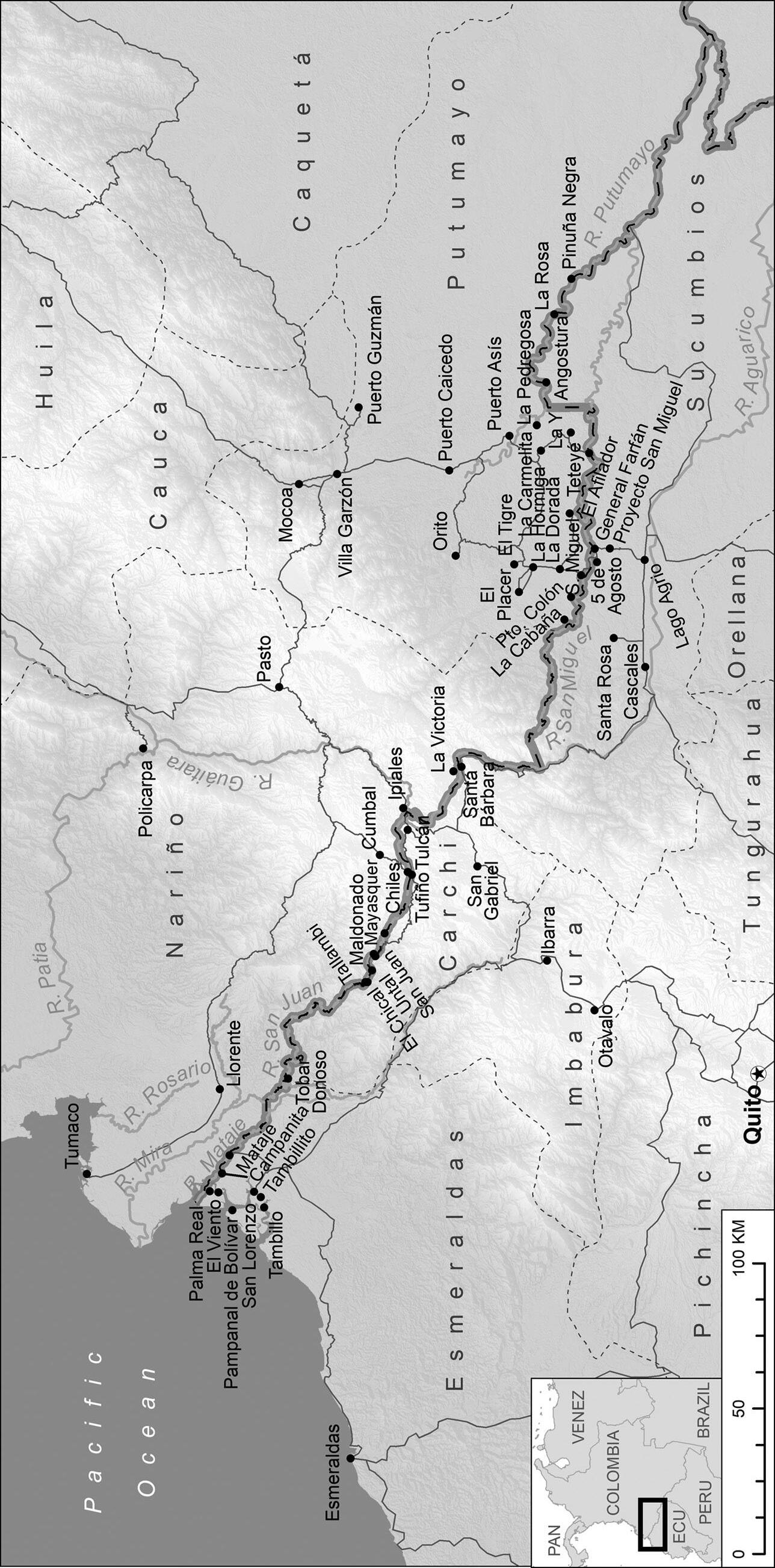

3.1

Maps

Border crossings along the Colombia-Ecuador border 76

3.2 Border crossings along the Colombia-Venezuela border 77

3.3 Regional coca cultivation stability in Colombia, 2007–2015 82

3.4 Main global cocaine flows 84

3.5 Violent non-state group interactions along the Colombia-Ecuador border (2011–2013) 86

3.6 Trafficking flows along the Colombia-Ecuador border 99

3.7 Violent non-state group interactions along the Colombia-Venezuela border (2011–2013) 105

3.8 Trafficking routes through Puerto Santander, Colombia 113

5.1 Drug trafficking routes that start in Llorente, Nariño, Colombia 165

5.2 Gasoline price in USD per container (21 liters) at the ColombiaVenezuela border in 2011 170

5.3 Strategic location of Ocaña (Colombia) for drug trafficking routes 205

7.1 Tracks of supposed cocaine flights in 2010 265

7.2 Persistence of coca cultivation along the Colombia-Ecuador border, 2007–2015 281

7.3 Displacements in Nariño (Colombia) in 2010 291

7.4 Confinement in Nariño (Colombia) in 2010 and 2011 291

C.1 Fieldwork itinerary in Nariño and Putumayo (Colombia) and Carchi (Ecuador) 358

C.2 Fieldwork itinerary in Nariño and Putumayo (Colombia) and Esmeraldas, Carchi, and Sucumbíos (Ecuador) 359

C.3 Fieldwork itinerary in Norte de Santander (Colombia) and Táchira (Venezuela) 360

C.4 Fieldwork Itinerary in Norte de Santander (Colombia) 361

C.5 Fieldwork itinerary in Arauca (Colombia) and Apure (Venezuela) 362

C.6 Fieldwork itinerary in Cesar and La Guajira (Colombia) and Zulia (Venezuela) 363

C.7 Fieldwork itinerary in La Guajira (Colombia) 364

C.8 Fieldwork itinerary in Putumayo (Colombia) 365

C.9 Fieldwork itinerary in Norte de Santander, Cesar, and La Guajira (Colombia) and Táchira (Venezuela) 366

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not exist without the hundreds of people across the ColombianEcuadorian and Colombian-Venezuelan borderlands, and in Bogotá, Caracas, and Quito, who shared their time, knowledge, and experiences with me. I am grateful to them, and especially to the families who welcomed me to their homes and with whom I developed meaningful friendships over the years. Their hospitality and generosity had no limits. They showed me what the social fabric of borderlanders can look like.

There are four women I would like to thank in particular—they know that I mean them. They accompanied me on different parts of my fieldwork journey. Their strength, courage, and leadership do not cease to inspire me. I am confident that with people like them—people who continue to make a difference in their communities, despite the risks that this entails—there is hope for a better, more secure tomorrow in the borderlands. It is my heartfelt desire that one day I will be able to openly thank them and others by name for all they did, and all they continue to do.

The support of many local and international organizations was invaluable for my fieldwork. They made traveling along and across the border so much safer and insightful. I would like to highlight the support by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations Mission Colombia, the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the Mission to Support the Peace Process in Colombia of the Organization of American States, the German Development Cooperation GIZ, the Norwegian Refugee Council, CARITAS, the Jesuit Refugee Service, the Colombian National Peace Observatory, the Ecuadorian Border Network for Peace (Red Fronteriza de Paz), and the Venezuelan Fe y Alegría. I also would like to thank Universidad de los Andes Bogotá, FLACSO Quito, and Universidad Central de Caracas for their academic support in Colombia, Ecuador, and

Venezuela, as well as the Colombian High Commission for Reintegration for facilitating access to former combatants.

I have been privileged to be able to work with, and learn from, so many brilliant minds at the University of Oxford. They have informed my thinking during the writing process for this book, especially at the Changing Character of War Centre, the Department of Politics and International Relations, the Department of International Development, the Latin American Centre, Pembroke College, and St Antony’s College. I am grateful to the participants at the book workshop at Oxford’s Centre for International Studies for their useful feedback, particularly Andrew Hurrell, Robert Johnson, David Keen, Keith Krause, Eduardo Posada Carbó, and Laurence Whitehead. At Oxford, I also would like to thank Alexander Betts, Richard Caplan, Malcolm Deas, Janina Dill, Simón Escoffier Martínez, Jörg Friedrichs, John Gledhill, Halbert Jones, Stathis Kalyvas, Kalypso Nicolaidas, David Preston, Adam Roberts, Diego Sánchez-Ancochea, Felipe Roa Clavijo, Peter Wilson, and Julia Zulver.

I am indebted to Michael Athanson for his excellent mentorship to produce the maps for this book, and I am grateful to Laura Courchesne, Mauricio Portilla, Santiago Rosas, and Andes Zambrano for outstanding research assistance. Outside Oxford, I would like to thank friends and colleagues at the Drugs, Security, and Democracy Program as partners in crime in embarking and sharing insights on such challenging research, especially Peter Andreas, Desmond Arias, Ana Arjona, Adam Baird, María Clemencia Ramírez, Lucía Dammert, Graham Denyer Willis, Angélica Durán-Martínez, Daniel Esser, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Paul Gootenberg, Thomas Grisaffi, Benjamin Lessing, Eduardo Moncada, Susan Norman, Javier Osorio, Winifred Tate, and Ana Villarreal. I am deeply thankful to Arlene Tickner for her support throughout the process.

This work benefited enormously from inspiring discussions and shared conference panels with conflict scholars and Colombia experts, especially Fernando Cepeda, James Forest, Peter Krause, Romain Malejacq, Théodore McLauchlin, Cecile Mouly, Jenny Pearce, Costantino Pischedda, William Reno, Lee Seymour, Henning Tamm, and Michael Weintraub. My thanks also go to David McBride for his excellent guidance and support at Oxford University Press as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

I could not have accomplished this work without financial support from the German Academic National Foundation; the Drugs, Security and Democracy Fellowship Program administered by the Social Science Research Council and the Universidad de Los Andes in cooperation with and with funds provided by the Open Society Foundations and the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada; the Economic and Social Science Research Council Impact Acceleration Award; the UK Higher Education Innovation Funding with the Global Challenges Research Fund; the Santander Award; FLACSO Quito;

and several grants and awards at the University of Oxford, including the Oxford Department of International Development and St. Antony’s College.

My friends and family accompanied me throughout this process. I cannot thank enough Marthe Achtnich, Chloé Lewis, and Ina Zharkevich for their support. My brother Stefan with Sandra and Mathilda were incredible sources of energy. I am most grateful to my parents, Manuela and Thomas, for their love, patience, and support from the inception to the end of this journey. This book is dedicated to them.

ABBREVIATIONS

ACCU Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urabá (Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá)

ADF Allied Democratic Forces

AUC Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia)

BACRIM Bandas Criminales Emergentes (Emerging Criminal Bands)

CODHES Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (Consulting for Human Rights and Displacement)

COMBIFRON Comisión Binacional de Frontera (Binational Border Commission)

DRC Democratic Republic of the Congo

FDLR Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda

FDC Forces de Défense Congolaise

ELN Ejército de Liberación Nacional (National Liberation Army)

EPL Ejército Popular de Liberación (Popular Liberation Army)

ERPAC Ejército Revolucionario Popular Antisubversivo de Colombia (Popular Revolutionary Anti-Terrorist Army of Colombia)

FARC-EP Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo

(Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army)

FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas

FBL Fuerzas Bolivarianas de Liberación (Bolivarian Forces of Liberation)

M-19 Movimiento 19 de Abril (19th of April Movement)

M-23 Mouvement du 23-Mars (March 23 Movement)

UN United Nations

US United States

USD US dollars

PROLOGUE

Witnessing Insecurity from the Margins

This book is the result of a decade of research in and about the shared borderlands of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. It presents an alternative narrative of the recent history of the modern world’s longest internal armed conflict and its embeddedness in a region where violent crime is entrenched—a history of insecurity witnessed from the margins.1

This decade starts on 1 March 2008, when the Colombian armed forces bombed a camp of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia–Ejército del Pueblo—FARC). The bombing took place, however, in Angostura, 1.8 kilometer into Ecuadorian territory. Killing the FARC’s number two in command, Raúl Reyes, the skirmish marked a turning point in Colombia’s internal armed conflict. From the country’s center, it was seen as an iron-fisted message of strength from Bogotá to the FARC. Yet the message to Bogotá was a different one; furious about the violation of their territorial sovereignty through what they considered an unannounced military incursion, Ecuador cut diplomatic relations with its neighbor. Venezuela did so too, and stationed tanks and troops at its border. At that moment, I decided to carry out field research to explore the spillover potential of Colombia’s war to its neighbors in the aftermath of Angostura. I focused my work on the Ecuadorian northern border zone, which was at that time becoming increasingly militarized, securitized, and stigmatized as a result of the attack.2

I then decided to widen my lens of analysis to explore all four sides of the Colombian-Ecuadorian and Colombian-Venezuelan borderlands. This way, I was able to witness the developments in Colombia’s war from the margins, literally and figuratively. Between 2011 and 2013, my research took me not only to Bogotá, Caracas, and Quito but also to numerous towns, villages, indigenous settlements, and lone farms in the Colombian departments of Nariño and

Putumayo, and the Ecuadorian provinces of Esmeraldas, Carchi, and Sucumbíos at the Colombia-Ecuador border; and in the Colombian departments of Arauca, Norte de Santander, Cesar, and La Guajira, as well as the Venezuelan states of Apure, Táchira, and Zulia at the Colombia-Venezuela border (see appendix C). This journey was interspersed with historical political landmarks. Shortly after Reyes’s death, then-FARC leader Manuel Marulanda Vélez died of a heart attack on 26 March.3 The insurgents were hit hard again when Colombian state forces killed Marulanda’s successor, Alfonso Cano, on 4 November 2011.4 I had just left Tumaco, a border town on the Pacific coast, when I heard the news. Although miles away from where Cano himself was killed (in Suárez, Cauca), that week ten military officials were killed in Tumaco by the FARC in the aftermath of Cano’s death, and the people I spoke to voiced their concerns about the recent increase in combat, kidnappings, assaults, and land mines. I then traveled to the remote border department of Putumayo, where locals also felt the violent shockwaves that resulted from Cano’s death. Suddenly, my travels became more risky than they had been before—everyone expected acts of retaliation. Cano’s killing left the FARC weakened. As some analysts argue, it was this position of weakness that eventually brought them to the negotiation table again,5 after previous peace talks under then president Andrés Pastrana between 2000 and 2002 had failed.6

In August 2012, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos Calderón announced the beginning of formal peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC rebels. Around that time, my journey took me across the border from Venezuelan Apure to Colombian Arauca, one of the most war-torn regions of the country. While internationally the announcement was met with praise and optimism, in Arauca it resulted in bomb detonations and gunshots. The department registered a spike in the number of attacks and armed clashes between guerrillas and armed forces—after all, no one wants to be seen as starting negotiations from a position of weakness.

In October of the same year, Hugo Chávez Frías was re-elected president of Venezuela, which many interpreted as the beginning of the country’s shift toward authoritarianism. Carrying out research in Venezuela’s border zone at the time, I joined one of eight Jesuit priests—my hosts—in observing the polling stations in the Venezuelan town of Maracaibo. In this city, the elections not only contributed to the polarization that characterized the rest of the country as well but also fueled fears of a rise in cross-border tensions. Two years later, Chávez would be defeated by cancer, and Nicolás Maduro Moros would become his successor. Since then, Venezuela has been dragged into a downward spiral of economic crisis, political turmoil, and criminal violence.

From the perspective of the Andean margins, the second half of this decade, after 2013, was paradigmatic of a constantly evolving security landscape rather

than a linear pathway toward a horizon of peace. In this five-year period, I carried out several follow-up fieldwork trips. In 2014, I returned to the wartorn Catatumbo region, a powder keg where the FARC, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional—ELN), and the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación—EPL)7 governed territory and its inhabitants, and liaised with multiple right-wing and trafficking groups to benefit from the lucrative illicit drug trade. I listened to worried people who then still lived under the reign of alias “Megateo,” EPL leader and narco-broker. As I discuss in chapter 6, local community members described him as a role model, a “brother” who “understands the people.” He was killed by the Colombian armed forces in October 2015. Triggering mass displacements, this lethal military operation greatly concerned locals, yet Bogotá and the international media hailed it as a success in the global war on drugs. The era of the “Warlord of [a] Rural Cocaine Fiefdom,” as the New York Times dubbed him, or the “most wanted drug lord,” according to the BBC, was over.8

While Colombia continued on its journey between war and peace, three humanitarian crises at Colombia’s borders with Venezuela and Ecuador overshadowed political developments. First, in 2015, Venezuelan president Maduro mandated the unilateral closure of the Colombia-Venezuela border and started to deport Colombians en masse. More than twenty thousand Colombians who had been living illegally in Venezuela crossed back into Colombia, straining local resources and fueling diplomatic tensions between the two countries.9 When I returned to the Colombian side in January 2016, it was still formally closed; I was not able to cross over to Venezuela. I then went back to Arauca, where people were not only concerned about how the border closure undermined their livelihoods—to a large extent sustained through legal and illegal cross-border trade—but also about the prospects of “peace” with the FARC. Due to the ELN’s dominant position in Arauca, the idea that the FARC might demobilize fueled fears of an increase in violence rather than hope for a better life in the region. The second humanitarian crisis took shape further north, in the department of La Guajira, where I returned to in early 2016. State neglect and severe drought produced a situation in which children, particularly indigenous Wayúu, were dying of malnutrition. Given the immediacy of their needs, for community members, the vision of a peace negotiated in Havana did not translate into a lived reality of peace in their territory. The third crisis affected Ecuador. Shortly after the ELN and the Colombian government announced the beginning of peace talks in Quito in March 2016, a deadly earthquake struck the Ecuadorian border province of Esmeraldas. The resulting humanitarian response became a national priority, stalling mediation efforts until early 2017.

The rest of the year continued to be eventful in Colombia. On June 23, 2016, the FARC and the Colombian government agreed to a bilateral ceasefire. In

August, I was in a meeting with the commander of the Colombian army when he received a call from Cuba where the peace talks were underway; after more than fifty years of armed conflict and four years of negotiations, the Colombian government and the FARC had reached a final peace agreement. Yet while it sparked enthusiasm internationally, within the country skepticism was rife. As a taxi driver in Bogotá put it to me on the morning after the announcement of the deal: how could Colombians be sure that ex-FARC combatants would be able to reintegrate into civilian life after decades in the jungle? Would they not use the demobilization as a pretext to continue life as criminals, fueling insecurity in urban areas? These and other concerns that demonstrated people’s mistrust toward peace would go on to contribute to a vote that, while a surprise to many outsiders, was to a certain degree predictable to some of those who were following events closely. Even though on September 26, President Santos and FARC leader Timochenko signed the peace deal, it was rejected in a plebiscite on October 2, 2016. Still, Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on October 7, 2016, perhaps the Nobel Peace Prize Committee’s vote of confidence to the Colombian president.10 In any case, the results of the plebiscite were telling: having suffered most from continued violence, almost all border areas voted in favor of peace, while in less marginalized regions the “no” vote prevailed.11

On November 24, 2016, headlines in Bogotá’s newspapers praised Santos and Timochenko for finally signing a revised peace deal, ending more than five decades of armed conflict—this time, supposedly, for real.12 This revised deal was approved by Congress shortly afterward, paving the way for a new era of peace. The situation on the ground in Colombia’s margins, however, did not reflect a straightforward transition from war to peace. At that time, I was back in Tumaco. Locals expressed unease amid uncertainty over who would fill the power vacuums left by the FARC, should they indeed demobilize. They were also worried because of the most recent killings of that month, supposedly triggered by the assassination of a FARC dissident, as I discuss later in the book. Planning my travels for the following day to Catatumbo in the border department of Norte de Santander, I reviewed social media and was sent photos of roads blocked by explosives, an attack by ELN rebels against a police station, EPL pamphlets announcing the continuation of the armed struggle, a burned ambulance marked with EPL graffiti, and farmers fleeing their homes, scared of being caught in the crossfire.

For the international community, the peace deal ended the FARC’s armed struggle against a democratically elected government. Yet for many marginalized community members, it also ended their informal protection by the FARC from other armed groups: paramilitary successor groups, Venezuelan gangs, Mexican drug cartels, and ELN rebels. The EPL was another source of fear,

as it gained more territory and numbers than the FARC had held in Norte de Santander.13

In early 2017, the FARC began to demobilize in designated transition zones across Colombia, and the ELN formally entered peace talks with the Colombian government in Quito. Meanwhile, Venezuela’s crisis worsened, producing an overwhelming influx of Venezuelans across the border to Colombia. In Ecuador, former president Rafael Correa’s party secured its legacy by winning the presidential elections held in April 2017. By the time I went to some of the demobilization camps in March and April 2017, where FARC members were laying down their weapons, the Colombian president, ministers, and the international press had already visited, reinforcing the narrative of the peace deal’s success to the world. Remarkably, the FARC did complete the process and became a formal political party on September 1, 2017.14 The country’s pathway toward peace seemed to be irreversible now, and gained additional momentum with the ceasefire between the ELN and the government, announced shortly afterward in Quito.

Yet while Bogotá heralded the beginning of a new, more peaceful era, in the borderlands there is still no clear line between war and peace. At the ColombiaVenezuela border, violence continues to be fueled by a brutal war between the ELN and the EPL, the operations of FARC dissidents, and criminals taking advantage of Venezuela’s crisis. At the Colombia-Ecuador border, the murders of three Ecuadorian journalists by dissident rebels, Quito’s decision to revive militarization of the zone, and the stalling of the ELN talks in Quito (then moved to Havana) also present a sobering critique of the narrative of a “peace era.” Across both borders, cocaine production and other illicit businesses are thriving.

Witnessed from the margins, and against the historical backdrop of decades of conflict and crime in the Andean region, perhaps just another decade of insecurity passed by. Yet a perspective from the margins also highlights something else. While the centers have continuously focused their attention on large-scale attacks, as the one with which I started this decade, they have ignored how local communities have been maneuvering multiple kinds of insecurities along and across the border. Listening to their voices and understanding their experiences may not only serve to comprehend why insecurity in the margins has persisted throughout this decade, from 2008 to 2018. Perhaps it can also help change views from the centers, so that in the next decade, peace and security will indeed extend to and across the margins.

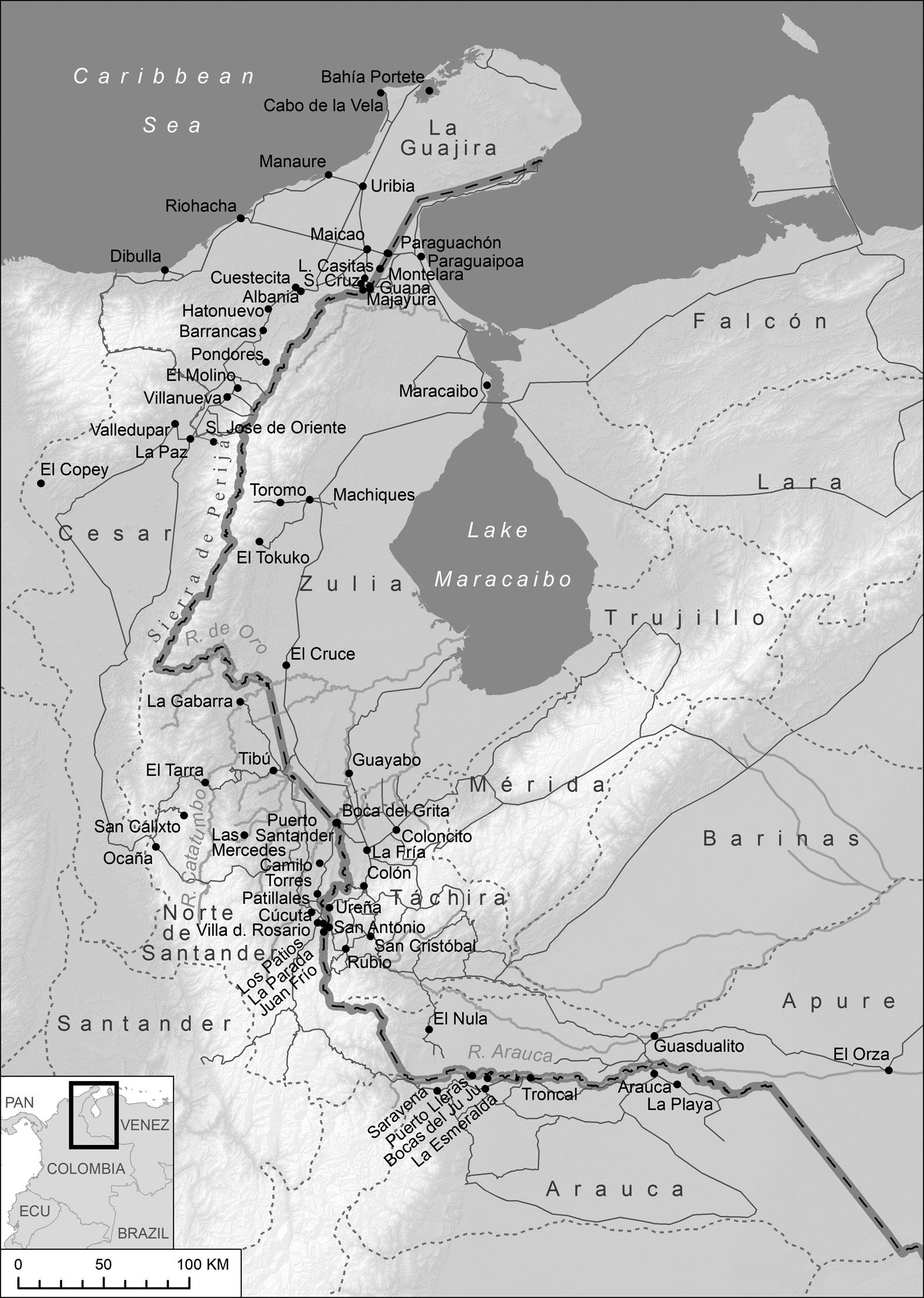

BORDERLAND MAPS

Map 0.1 The shared borderlands of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. Map created by Author.

Map 0.2 The ColombianEcuadorian borderlands. Map created by Author.

Map 0.3 The Colombian-Venezuelan borderlands. Map created by Author.