Intimate Strangers—Peripheries in Global Literary Networks

. . . more kings and princes have written of his deeds [Alexander the Great] than other historians have written of any king or prince that has ever been; that even today the Mahometans who despise all other biographies accept and honour his alone by a special dispensation.

Michel de Montaigne1

When Michel de Montaigne praises Alexander the Great as one of the three most outstanding of men, he notes Muslim reverence for Alexander as proof of his wide influence, suggesting the easy translatability of such stories into other kingdoms, cultures, and religions.2 Alexander’s gests spread so widely they were retold in Southeast Asia even before European arrival. The Southeast Asian Alexander, however, was a Muslim conqueror, transmitted to the region through a Perso-Arabic literary tradition. Furthermore, he was claimed as an honored ancestor in royal genealogies, and several sultans took his Arabic name, Iskandar. When in the early modern period Europeans started arriving in numbers in Southeast Asia, subsumed under the catch-all term East Indies, they encountered this alternate Alexander tradition. Shortly after Afonso de Albuquerque’s stunning victory in capturing the key port city of Melaka in 1511, the Minangkabau people from the highlands of nearby Sumatra sent an embassy; the report notes that they incorporated Alexander into their royal traditions:

And just at this very juncture there arrived at Malaca three pangajaoas [boat propelled by oars] from the kingdom of Menamcabo [Minangkabau], which is at the point of the island of Çamatra [Sumatra] on the other side of the south, and brought with them a sum of gold, and they came to seek for cloaths of India, for which there is a great demand in their country. The men of this kingdom are very well made, and of fair complexion; they walk about always well dressed, clad in their silken bajus [Malay dress], and wearing their crisis [kris, a Malay short sword with a wavy blade] with sheaths adorned with gold and precious stones in their girdles.

1 “On the most excellent of men,” Essais II:36, Montaigne 1991: 854.

2 For Montaigne’s knowledge of the Ottoman Empire, see Rouillard 1941: 363–74.

These are a people of good manners and truthful character; they are Hindoos [gentios, Gentiles]; they have a great veneration for a certain golden head-dress which, as they relate, Alexander [the Great] left there with them when he conquered that country.3

Instead of absolute alterity, the Portuguese found commensurability in shared literary history. The report emphasizes likeness in the antipodeans, describing them as “white” (alvos) and in such positive terms as “well habituated and true” (bem acostumada, e verdadeira). The Minangkabau’s “high esteem” (grande estima) for Alexander –translated as “great veneration” in the nineteenth-century edition—suggests they fall on the near side of the civilized–barbarian divide. Not fully understanding that the people they met were Muslim, the Portuguese classified them as gentios (Gentiles, meaning pagans)—(mis)translated as “Hindoos”—of another nation, non-Christian. But like Montaigne, they found Alexander revered by strangers, and over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as they came into greater contact with Islamicate societies, Europeans became increasingly aware of this other reception of Alexander.

Alexander’s notable translatability should alert us to the connectedness of literary cultures of East and West, guiding our understanding of early modern literary cultures and cross-cultural interactions. The Alexander stories—fascinated with strangers and marvels, thematizing travel and cross-cultural contact, and featuring an imperial conqueror as protagonist—offered not only shared motifs for divergent imperial self-definitions but also provided ways for peoples across Europe and Asia to conceptualize their place in the world. The Alexander legends spread through economic and political networks connecting the world’s different regions and became a means of imagining these linkages.

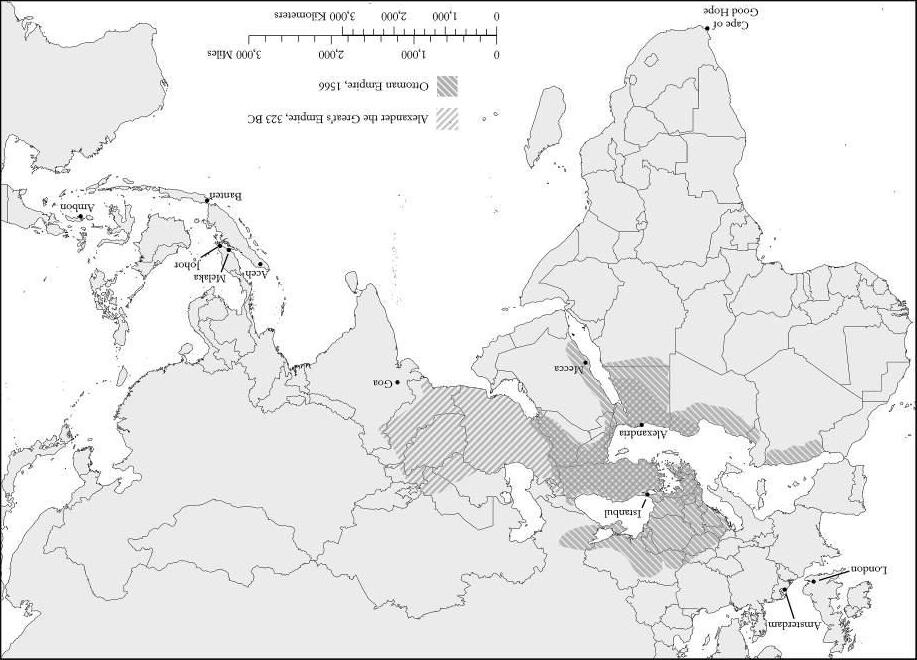

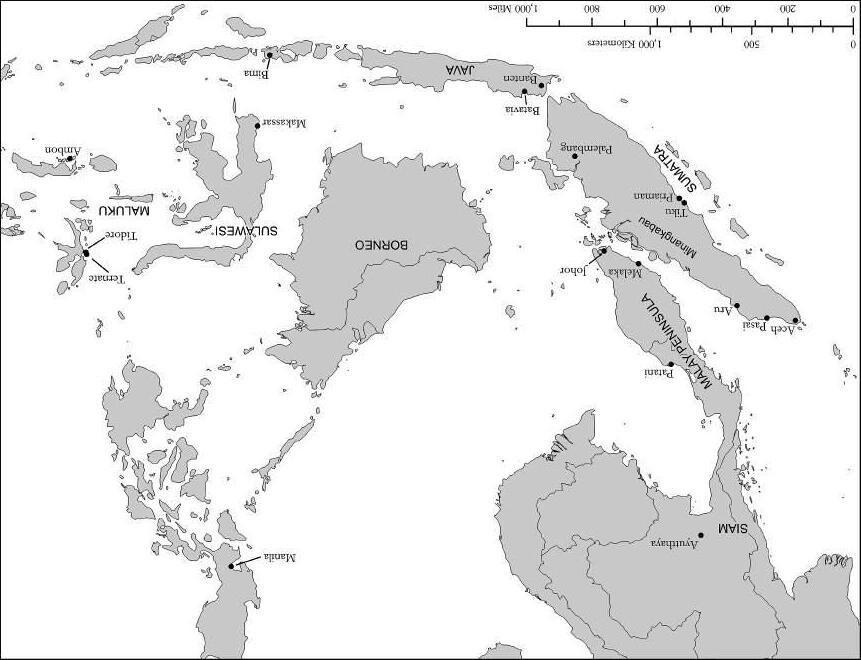

My particular foci are the cultures of Britain and Southeast Asia in the early modern period of direct contact as Europeans entered the Indian Ocean sphere in search of spices, with their ultimate goal the Spice Islands (the Moluccas or Maluku) of eastern Indonesia. Myriad versions of Alexander offer many points of entry into this transnational body of literature, but the unprecedented meeting of cultures from the two ends of Eurasia makes early modern Southeast Asia a particularly acute locus to “map the labyrinth” of a global literary network.4 Of places to find Alexander, Britain and Southeast Asia are some of the most distant culturally and linguistically. As the regions came into contact, classical presences in both shaped ideas of empire, of trade, and of contact with foreigners. In this early modern encounter, their “connected

3 Albuquerque 1964: 3.161–2. The report is included in the narrative compiled by Afonso’s son Braz and published in Lisbon in 1557: “e neste tempo chegáram tres pangajaoas do reyno de Menamcabo, que he na ponta da ilha de Çamatra da outra banda do sul a Malaca, e trouxeram somma de ouro, e vinham buscar pannos da India, de que tem muita necessidade na sua terra. Os homens deste reyno sáo muito bem dispostos, e alvos, andam sempre bem tratados, vestidos em seus bajus de seda, e crisis com bocaes de ouro, e pedraria na cinta. He gente bem acostumada, e verdadeira. São gentios. Tem em grande estima huma carapuça de ouro, que dizem que lhes ali deixou Alexandre, quando conquistou aquella terra” (Albuquerque 1923: Parte 3, Capitulo 37, 2. 133–4).

4 The phrase is from Akbari 2013: 20.

histories”—Sanjay Subrahmanyan’s term to refer to “supra-local connections,” wherein “ideas and mental constructs, too, flowed across political boundaries” so that histories are recognized as “not separate and comparable, but connected”5—included a literary dimension: the flows of Alexander stories. Given the significance of the early history of Asia’s interactions with Europe, their connected literary histories of Alexander constitute an important exemplar for cultural translation.

This book explores parallel literary traditions of the mythic Alexander in Europe and Southeast Asia. They share a common ancestry as cousins springing from the same classical sources and shaped by mutual contact with Middle Eastern Islamicate societies, both in the shared inheritance of medieval Arabic literature and in contemporary trade and diplomatic relations, particularly with the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, these parallel traditions were shaped by cross-cultural encounters arising from trade and exploration that were starting to connect Britain and Southeast Asia. The economic stimulation of long-distance trade gave rise to state centralization, including forceful incorporation of surrounding provinces. The expansionist kingdoms in both archipelagoes were empires of trade. And out of these cross-cultural interactions they produced parallel discourses of empire. These imperial discourses pivoted around Alexander the Great (356–323 bce), whose name has long been synonymous with empire. The historical Alexander waged war so successfully—and brutally—that in a short lifetime he subdued an immense territory. Pushing further into Asia than any Greek before him and overthrowing the great Achaemenid empire, Alexander’s conquests turned him into a figure of myth. Yoking together East and West—especially in the symbolic unification of the Susa weddings where he and his men took Persian brides—Alexander, seemingly, created a universal empire. Even after death, Alexander became the object of imitation by Roman emperors and many others, including Southeast Asian sultans.

In the age of early modern exploration Alexander became associated with trade. European travelers to Asia saw themselves as another Alexander in the East. They couched the pursuit of long-distance trade in the rhetoric of imperial conquest. Southeast Asians turned to the example of Alexander to understand their diplomatic relations with the West, which for them also included the Ottoman empire. Their Alexander romances tentatively explore Alexander’s role in encouraging East–West trade; later fictions invoking Alexander in moments of cross-cultural encounter use him as model first for monarchs and then for merchants. By the eighteenth century, Pierre Briant has shown, Enlightenment authors—especially Montesquieu in his influential Spirit of the Laws (De l’esprit des loix, 1748)—developed a full theory of Alexander’s “commercial revolution,” depicting him as the discoverer of the Indian Ocean who opened up the East for trade; justifying European imperialism, they saw in Alexander a “sovereign guided by reason, exercising power based on knowledge, and able to introduce harmony and peace in a new world made up exchanges and communications,” in short,

5 Subrahmanyam 1997b: 747–48.

the rational Western ruler reviving a supposedly stagnant “orient.”6 While the image of Alexander as “conqueror-civilizer” would become a prominent strand in European Enlightenment discourse at a time when an ascendant Europe was colonizing Asia, elements of this discourse were already present in earlier representations of Alexander.7 British and Malay versions of the Alexander Romance depict Alexander as a conqueror who institutes civilization; their literatures associate him with the values, positive and negative, of contemporary empires of trade.

As trade and exploration expanded knowledge of the world, English and Malay literary traditions evinced increasing awareness of each other. Their literary traditions incorporated images of the other in their representations. The literatures of maritime empires adapted Alexander to reflect local ideas of empire, outsiders, trade, and marvels; he functioned as a transcultural icon through which various cultures mediated their relationship to the foreign. Reading the varied discourses of Alexander in English and Malay literatures, this book examines what Barbara Fuchs calls “mimetic rivalries”: while focusing on “European dynamics of imperial competition,” she notes that rivalries “extend across hemispheres because of Rome’s contested nature as imperial exemplum and predecessor. Thus, Ottomans and Incas engage with a Roman imperial imagery as they argue for their imperial status.”8 My book turns to Britain and Southeast Asia’s imperial claims to examine their mimetic rivalries in a shared imitatio Alexandri. Their retailing of Alexander stories did not happen in a closed system; rather, increased cross-cultural contact and the consequent need to assimilate new knowledge generated by that contact made Alexander an especially attractive figure as a conceptual bridge to the outside world.

The existence of shared literary elements and traditions suggests that the character of cross-cultural encounters was not the civilizational clash of utterly alien Others but rather a meeting of distantly-related cultures with overlapping interests and history, and these parallel traditions (and the interactions between them) shaped major canonical works in both traditions. Comparative literature has long focused on the study of influences, sources, and allusions, which provide insight into how individual authors read and wrote; however, study of literary traditions should go beyond influence and imitation to consider unstated assumptions that define the period’s crucial ideas. Historicizing the parallel receptions of Alexander traditions in Britain and Southeast Asia, this book shows how borrowings from a transcultural literary tradition fashioned imperial self-definition.

Traffic in Books

Europe’s eastern “trafficking” focused particularly on Southeast Asia, especially the famed Moluccas (Maluku) or Spice Islands in eastern Indonesia, whose “ownership, possession navigation and trade” was the direct cause of a series of negotiations

6 Briant 2017: 158, 150. 7 Briant 2017: 118. 8 Fuchs 2015: 412; see also Fuchs 2001.

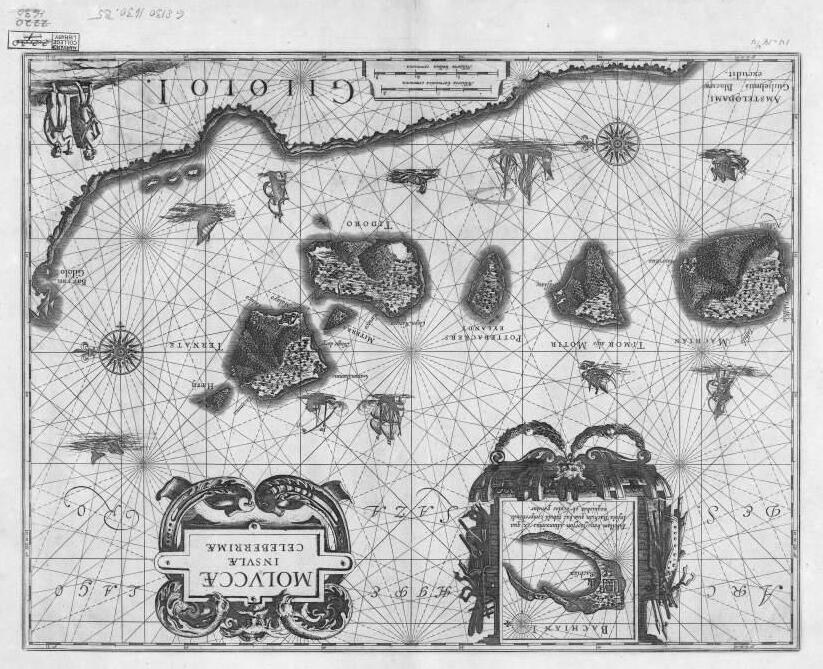

between Portugal and Spain that finally ended in the Treaty of Tordesillas.9 The poet Edmund Spenser praises Queen Elizabeth’s glory by alleging that it extended to the “margent of the Moluccas,” while John Milton compares Satan to East India ships sailing from “the Isles / Of Ternate and Tidore, whence Merchants bring / Thir spicie Drugs.”10 Ternate and Tidore are two islands of the Moluccas (Maluku) or Spice Islands, whose importance as the only source of nutmeg and cloves far exceeded their size; two pages are devoted to these tiny islands in Willem Blaeu’s Atlas Maior (1665), the earlier Atlantis Appendix (1630), and other Blaeu atlases (Figure 0.1). European intervention in the islands’ local politics served as matter for William Shakespeare’s successor with the King’s Men, John Fletcher, whose play The Island Princess (1619–21) was so popular it was adapted four times in the Restoration.11

Southeast Asia’s centrality in European imagination may be discerned from Portuguese traveler António Galvão’s view of European discoveries as simultaneous expansion eastward and westward to meet in the Pacific anti-meridian of the Treaty of Tordesillas, offering, as Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam suggest, “a worldview in which the imagined centre lies in fact in the Moluccas.”12 The Spice Islands were the new hub of a globalizing economy, as Europeans found a sea route that rounded the Cape of Good Hope to obtain spices directly from the source; however, the historical and cultural center lay westward, in the area defined by Mecca, Jerusalem, Rome, and Constantinople. How trading kingdoms of the East and West reimagined themselves in relation to the old cultural center, the theme of this book, is traced in the elliptical orbits of world literature.

Literary journeys took circuitous paths along trade routes. Trade was not just in silk, spices, porcelain, and silver but also in books and manuscripts. Asian texts were acquired for European collections and in the early modern period collections of eastern works were dearly sought after. One such collection came available in 1625: the famed Arabist Thomas van Erpe (Erpenius, 1584–1624)’s library of “oriental” manuscripts. In November 1625, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, was at the Hague in the Low Countries in November 1625 pawning England’s crown jewels to raise funds in support of a Protestant alliance to recover the Palatinate lost to the Spanish in the Thirty Years’ War. It was an unpopular cause, exacerbated by royal high-handedness: having ascended the throne only in March that year when his father James I died, already in August Charles I dissolved Parliament when he was refused further subsidies for the war. But in 1625, the worst of the crises were yet to come, and Villiers had leisure to pursue cultural interests. An influential patron and collector of art, while abroad he purchased Erpenius’ manuscript collection for the sum of 500 pounds, thwarting Leiden University’s months-long effort to acquire it. This collection, which came to Cambridge University Library in 1632 when Buckingham’s widow finally donated it to fulfill his intent to build up the library when he was appointed Chancellor in 1626,

9 Brotton 1998: 132. 10 Spenser 2007: 5.10.3; Milton 1998: Paradise Lost 2.638–40.

11 Sprague 1926: 49, 74, 82–6, 123. 12 Alam and Subrahmanyam 2011: 340.

Harvard Map Collection, Harvard Library.

Figure 0.1 Map of the Spice Islands by Willem Jansz. Blaeu, Molvccae insvla celeberrimae, Amsterdam, 1630?

included six Malay manuscripts. One is a commentary on the Qur’ān identifying the figure of Dhū’lqarnayn from Sura 18 (Sura of the Cave) as Alexander the Great.

The transfer of Alexander in a Malay work to Cambridge was part of a larger early modern movement of material objects, luxury goods (spices, silk, and porcelain), ideas, and even people from what was then known as the “East Indies” into Europe. Exploration had a profound effect: it opened up new natural worlds for scientific study while material and knowledge exchanges with Asia through commerce led to the development of medicine and natural history.13 This “trafficking”—a term Jonathan Burton proposes, from the early modern word “traffique,” to signify not just trade but also wider, multidirectional forms of cultural intercourse and exchanges14—not only transformed European material culture—drinking tea from china or spicing foods with pepper—but also left its mark on art and literature.15 Trafficking with Asia left not only traces in literary representations and images of the exotic, but also on English literary forms. Eastern imports—as Miriam Jacobson shows with the imagery of sugar, horses, bulbs, “orient” pearls, and the concept of zero—modified classical reception to give English verse a “materially inflected Eastern poetics.”16

The path taken by the idea of Alexander in the Cambridge manuscript, MS Or. Ii.6.45, Tafsīr sūrat al-Kahfi, reveals the complexity of intertwined literary and trade networks in the early modern era that connected Southeast Asia with Europe and the Middle East. The manuscript itself, a duodecimo of 134 pages, presenting Arabic verses in rubrication interspersed with Malay commentary in black ink, is one of the earliest extant Malay works of Qur’ānic exegesis. The work’s two major sources, al-Khāzin (d. 741/1340)’s Lubāb al-ta’wīl fī ma‘ānī al-tanzīl (The Core of Interpretation in the Meanings of Revelation) and al-Baydāwī (d. 685/1286)’s Anwār al-tanzīl wa asrār al-ta’wīl (The Lights of Revelation and the Secrets of Interpretation) show reliance on Middle Eastern traditions of Qur’ānic commentary that identified Alexander as Dhū’lqarnayn. In addition, the manuscript shows traces of transcultural traditions of Alexander, for its commentary on Dhū’lqarnayn (verses 83–98) offers rival Greek and Persian genealogies. The name is first mentioned in verse 83, in which the Jews ask prophet Muhammad for the story of Dhū’lqarnayn journeying to the East and West. The exegesis of the second half of the line, running to about four and a half eleven-line pages, offers varied opinions on his identity:

Kata Moghaser bahawa nama Dhū’lqarnayn itu Marzaban anak Marzazabah al-Yunani daripada anak Yafith. Yafith [sic] itu anak Noh. Kata setengah nama[nya] Iskandar anak Filis cucu Qaylasuf Rumi dan Parsi. Kata setengah raja mashrik dan maghrib bahawa raja besar dalam dunia. Mengata orang dua orang raja Islam dua orang raja kafir. Maka Islam itu Dhū’lqarnayn dan Sulaiman. Maka yang kafir itu Namrud dan Tajta Nas ar dan al-Dhūlqarnayn itu salah. [Moghaser says that the name Dhū’lqarnayn [refers to] Marzaban the son of Marzazabah al-Yunani, who is the son of Japheth. Japheth is the son of Noah. Some say his name is Alexander

13 Cook 2007. 14 Burton 2005: 15–16. 15 Jardine and Brotton 2000; Brotton 2003.

16 Jacobson 2014: 14.

the son of Philip the grandson of Qaylasuf, a Roman and Persian. Some say it is the king of the east and west that is the great king in the world. People say that two are Muslim kings and two infidel kings. The Muslims are Dhū’lqarnayn and Solomon. The infidels are Nimrod and Tajta Nas ar and not Dhū’lqarnayn.]17

Competing exegeses, whether of Dhū’lqarnayn’s identity as Persian or Greek, or of Alexander’s genealogy, offer varied interpretations. Alexander’s father is Philip, from the Greek tradition, but he is identified as Roman and Persian. The name Dhū’lqarnayn has multiple meanings as well: the “two-horned” refers either to world conquest in its associations with the compass points of East and West, or to a world divided between two Muslim kings and two unbelievers. The commentary thus weaves together histories from several traditions: Greek, Persian, and Hebraic. For the history of Qur’ānic exegesis in Southeast Asia, the manuscript’s importance lies in representing the kind of writing produced in early seventeenth-century Aceh in northern Sumatra, its place of composition, before the period when many exegetical works were destroyed by the cleric Nuruddin al-Rānīrī, who tried to purge the land of heretical (sufistic) works.18 But its significance goes beyond a local reception of cosmopolitan forms: the manuscript is only extant today because of the connected history of European trade in Southeast Asia.

Several of the Cambridge Malay manuscripts came into Erpenius’ hands through the collecting activities of an East India merchant, Pieter Willemsz. van Elbinck, known in English records by his maternal surname, Peter Floris. He was already in Southeast Asia by 1604. One of the Cambridge manuscripts, MS Or. Dd.5.37, a Malay version of the history of the biblical Joseph (Hikayat Yusuf), concludes with a note indicating that the copyist was Floris in October 1604, and another, MS Or. Gg.6.40, includes in the fourth part a Malay-Dutch vocabulary with the note that the Malay was written in Arabic letters by Peter Willemsz. van Elbinck on 1 June 1604 in Aceh.19 Initially employed by the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie), Floris chafed at their restrictions on private trade, complaining, “I cannot imagine what the Hollanders meane, to suffer these Maleysians, Chinesians and other moores of these contries, and

17 Cambridge MS. Or. Ii.6.45, f. 105v. For the commentary tradition on the name, see Nöldeke et al. 2013: 115 n. 137. Regarding the name Dhū’lqarnayn, Ibn Kathīr mentions Marzaban: “Scholars disagreed regarding his name. It has been narrated in a Hadith that he was from the tribe of Himyar and that his mother was Roman, and he was called the Philosopher for the excellence of his mentality. However, As-Suhaili said: his name was Marzaban Ibn Marzabah. This was mentioned by Ibn Hisham who mentioned in another location that his name was: As-Saʿb Ibn Dhi Mar’id who was the grandfather of the Tababiʿah and it was him who gave the verdict to the benefit of Ibrahim” (Ibn Kathīr 2001: 130–1). See Arthur Schaade’s German translation, Ibn Kathīr 1908. If the first letter of the name Qaylafus were fah (ف) instead of qaf (ق), the word might be فوسليف, or philosopher.

18 Riddell 1990: 33, which published verses 1–3, 9, 17, 34, 47–9, 75–9; Riddell 2001: 154–60; Riddell 1989; Riddell 2014. I would like to thank Peter Riddell for sending me a copy of the last article; in an email, he mentioned that he is completing a full study of the manuscript. The earliest notice of this manuscript appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, van Ronkel 1896: 9, 47–9. Malay manuscripts may have been collected in Aceh by Peter Floris (Pieter Wilemsz. Floris van Elbinck) (see also Iskandar 1996: 315).

19 MS Or. Ii.6.45 does not indicate provenance; it is probably acquired by Floris.

to assiste theym in theyr free trade thorough all the Indies, and forbidde it theyr owne servants, contryemen and bretheren uppon payne of death and losse of goods.”20 In 1609 he sought employment with the English East India Company, and led an expedition on board the Globe, the East India Company’s seventh voyage, that left in January 1611 to trade first on the Coromandel coast of India, next Bantam (Banten) in Java, then Patani on the northern Malay Peninsula, and finally Siam. He died two months after his return to London in 1615, leaving a journal of the voyage, written in Dutch and translated into English, of which extracts were printed by Samuel Purchas in his continuation of Richard Hakluyt’s work, Hakluytus posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes (1625).

It is worth pausing briefly over Peter Floris’s biography, a man whose many translations reveal the complexities of the early modern transculturated sphere. In name and identity, he was translated from Dutch merchant to “English” (even as his surname van Elbinck suggests an origin on the Baltic coast), entailing the crossing of national lines. His East Indies travels meant further crossings of political boundaries, not only from the European sphere to Southeast Asia, but also from polity to polity within Southeast Asia. Aptly, this much-translated man would himself be engaged in copying and translating foreign texts. These geo-political crossings resulted in the transformation of his tongue, as his facility in Malay and interest in its literature show.

Floris’s transculturated European in the Malay world is by no means unique, as attested by East Indies archives. Europeans learnt Malay and other local languages out of commercial necessity. Malay was particularly important as the region’s lingua franca. In the early sixteenth century, António Galvão writes that in the East Indies “the number of languages is so great that even neighbours do not, so to speak, understand each other. Today they use the Malay tongue, which most people speak, and it is employed throughout the islands, like Latin in Europe.”21 Two centuries later, Malay’s importance has not waned: in 1725 François Valentijn, vicar of the Dutch Reformed Church in Ambon, testifies to its importance: “Certainly Portuguese and the Malay language are two languages with which one can reach all peoples directly, not only in Batavia, but indeed through the whole Indies up to Persia.”22 English factors posted in Java or the Moluccas, the Spice Islands, in archipelagic Southeast Asia learnt Malay to conduct business. At the English factory in Banten, Floris met Augustine Spaulding, who was also fluent in Malay. An interpreter for the factory, having lived in Banten for over a decade, Spaulding, like Floris, was interested in the study of Malay, translating the Frankfurter Gothard Arthusius’ Latin translation of Dutch Frederik de Houtman’s

20 Floris 1934: 44.

21 Galvão 1971: 75. The original reads: “São tamtas he tão desvairadas, que quasy se não emtemde[m] os vezinhos huns ha outros, por omde parece que fforão povoadas de companhas entranhas. . . . Prezão-se aguora do malayo e os mais ho ffalão e servem-se dela por toda terra como latim na Eyropa” (74).

22 The original quotation reads: “Dog de Portugeesche en de Maleitze taal zyn de twee taalen, waar mede men niet alleen op Batavia, maar zelf door gansch Indiën, tot in Persiën toe, met allerlei volkeren te recht kan raken” (Valentijn 1724–6: 4.1:367).

handbook of conversational Malay to which is given the title Dialogues in the English and Malaiane Languages (1614).23 This work of translation was promoted by the East India Company: their 22 January 1614 minutes mentions “a book of dialogues, heretofore translated into Latin by the Hollanders, and printed with the Malacca tongue, Mr. Hakluyt having now turned the Latin into English, and supposed very fit for the factors to learn, ordered to be printed before the departure of the ships.”24 Even in Japan, the English relied on translation through Malay: John Saris, who opened up Japan for English trade in 1613, employed an interpreter who translated from Japanese into Malay: Saris writes that his “Linquist [sic], who was borne in Iapan, and was brought from Bantam to our ship thither, being well skild in the Mallayan tongue, wherin he deliured to me what the King spoke vnto him in the Iapan language.”25 By the early eighteenth century, European grammarians would recommend works like the Malay Alexander romance, Hikayat Iskandar Zulkarnain, for the study of good Malay.26

Examples like Floris and his compatriots, Bertrand Romain argues, break down the divide between amateur collectors and professional philologists.27 The work of collecting eastern manuscripts depended on efforts of overseas merchants. The Bodleian Library saw its collection of Arabic manuscripts grow with the patronage of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, Chancellor of Oxford from 1630 to 1640, who donated over a thousand manuscripts between 1635 and 1640—including works in Malay such as the Hikayat Seri Rama, a Malay version of the Ramayana—amassed in part through a royal letter he obtained to require the Levant Company to bring back

23 Arthus 1614, a translation of Houtman 1603.

24 Calendar SPC/EIC, I, Doc. no 682 (January 22, 1614); quoted in Bertrand 2013: 144.

25 Saris 1900: 84. When the former daimyo of Hirado, Matsura Hōin, governing as regent for his young grandson, gave John Saris a diplomatic letter, the latter brought it to Java to be translated into Malay: “I procured Lackmoy and Lanching, two Chinesa Merchants, to translate the Letter which the King of Firando in Iapan had deliuered mee to carry to our King James. It was written in China Character and Language; they translated it into the Malayan, which in English is as followeth, viz.” (195).

26 In his introduction to Tweede Deel van de Collectanea Malaica Vocabularia of Maleische WoordboekSameling, Peter van der Vorm says, “’t boek genaamd hhikaΛjat Λiskander dzuw Λ-lcarnajn, of de geschiedenis van Alexander de Groot, is niet alleen van een seer goed mallays, maar ook van een klaare / en gemakkelijke stijl / buiten dat het met weynig vreemde woorden opgetooyd is / en dierhalven om de taal te leeren voor ieder nut” (The book named Hikayat Iskandar Dhū’lqarnayn, of the history of Alexander the Great, is not only [composed] in very good Malay, but also in a clear and easy style, except that it is embellished with a few foreign words and therefore useful for learning the language for everyone) (Vorm 1708: 8); and George Hendrik Werndly, Maleische Spraakkunst: “De Historie van Alexander den Groten. De stoffe van dit boek is gericht om te tonen dat Alexander de Grote, een heer van ‘t Westen en van ‘t Oosten geworden zynde de gansche wereldt heeft trachten te brengen tot de rechtzinnige lere des geloofs in den Godsdienst van den propheet Gods Abraham van den vriendt Gods over wien vrede zy! Dit boek is in zeer goed Maleisch geschreven en met zeer weinig vremde woorden opgetooid als mede van een zeer klaren en gemakkelyken styl en deshalben zeer nut om daar uit de taal te leren” (The History of Alexander the Great. The matter of this book aims to show that Alexander the Great, who became a lord of the West and of the East, has attempted to bring the whole world to the orthodox teaching of faith in the religion of God’s prophet Abraham, the friend of God, upon whom be peace! This book is written in very good Malay, embellished with very few foreign words, as well as in a very clear and simple style, and therefore it is very useful to learn the language from it) (Werndly 1736: 345); my translations.

27 Bertrand 2013.

a manuscript on each ship.28 Other Southeast Asian manuscripts were similarly acquired: in 1627 two palm-leaf manuscripts in Javanese and Old Sundanese came to Thomas James, the Bodleian’s first librarian, through his mercantile relatives trading in Java, while in 1629 another Javanese work—a version of the popular Persian tale of Amir Hamzah—was donated by William Shakespeare’s patron, William Herbert, the third Earl of Pembroke, probably acquired through the East India Company, which Herbert joined in 1611 and of which he became director from 1614.29 These works came to furnish significant national cultural institutions by way of the circuits of East Indies trade. National cultural innovations—the Bodleian Library only opened in 1602—were deeply implicated in exchanges with the East.

It is this sort of collecting and engagements with Asia—the cultural translatio of books and knowledge—that historian Robert Batchelor argues was instrumental to London’s rise to a global city and influenced its modern developments. Noting the transmission of manuscripts to London from Southeast Asia—including Malay works such the Hikayat Bayan Budiman collected by Edward Pococke from Borneo, Laud’s Hikayat Seri Rama, or William Herbert’s Javanese Amir Hamzah, Caritanira Amir Batchelor says, “almost a century before the Arabian Nights became popular in France and England, collections of stories and plays that circulated widely in Asia in multiple languages were arriving in London from the port cities of Southeast Asia, suggesting transcultural models of linguistic exchange.”30 Intriguingly, he suggests that such exchanges not only affected the development of ideas in London but also in Southeast Asia: briefly mentioning Southeast Asian works, including those discussed in this book, he argues, “New strategies of collecting and new kinds of history writing in Southeast Asia in part responding to English and Dutch activities . . . all suggested not an imposition of European models in Asia but complex emerging practices of history writing and archiving.”31 As scholars start doing justice to the full range of materials in early modern libraries and collections, we need to go beyond simply noting the presence of so many Asian materials in Western scholars’ hands to reading and analyzing the texts themselves. Historical revisionism calls for a corresponding literary comparatism. As imported eastern books filled the shelves of English libraries newly revived after the depredations of the Reformation, eastern matter came to transform English books, even literary works. Cambridge MS Or. Ii.6.45’s relation to English culture does not simply have to do with the amassing of libraries; its citation of Alexander’s Arabic name is, in a striking convergence, consonant with similar enunciations in English poetry. This convergence can be seen in Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (1612, 1622), a work of chorography, which though describing British lands—and thus has largely been read as a writing of nation—is also inflected by the East.32 Far from an inwardlooking parochialism the genre implies, Poly-Olbion’s celebration of England expands

28 Wakefield 1994: 130.

29 For Thomas James, see Batchelor 2011: 122–3. See description of the Amir Hamzah manuscript in Gallop and Arps 1991: 74–6; Noorduyn 1985: 58–64.

30 Batchelor 2014: 127. 31 Batchelor 2014: 127–8.

32 Helgerson 1992: 117–24.

outward to the globe, viewing eastern places, including key locales in Southeast Asia, as the proper stage for English action. At the same time, its interest in antiquarianism takes a global perspective by suggestively linking England to the Islamic East through the citation of Alexander’s Muslim name, Dhū’lqarnayn, from none other than the father of English poetry, Chaucer.

Drayton’s ambitious Poly-Olbion was so lengthy a work that while he settled on a plan by 1598, the first part was not published till 1612 and a second only appeared in 1622.33 Although the poem, as Drayton says, “delivered by a true native Muse,” is devoted to Britain, it is a Britain connected to the East. The first book of the second part, “The Nineteenth Song,” on Essex and southern Suffolk, coastal counties north of London, ventures far beyond Britain’s borders, as its Muse “poynts directly to the East” to celebrate “Our Brittish brave Sea-voyagers” (“Argument,” 19th Song). One of the earliest explorers, Ralph Fitch (1550–1611), was the first Englishman to visit Portuguese Melaka in 1588:

With Fitch, our Eldred next, deserv’dly placed is; Both travailing to see, the Syrian Tripolis.

…

On thence to Ormus set, Goa, Cambaya, then, To vast Zelabdim, thence to Echubar, agen Crost Ganges mighty streame, and his large bankes did view, To Baccola went on, to Bengola, Pegu; And for Mallacan then, Zeiten, and Cochin cast, Measuring with many a step, the great East-Indian wast. (Song 19.237–46)

The numerous foreign place names, including Southeast Asian Melaka, Pegu (Burma), and Cochin (Vietnam), displace English ones to signal England’s considerable investment in the overseas trade. Drayton was not the only poet to turn English voyages into verse. His friend, William Warner wrote a poem of English history, Albions England (1597), that extols English voyagers, telling the reader to read in Hakluyt “Of These, East-Indian Goa, South & South-east People moe, / And of their memorable Names those Toyles did vnder-goe.”34 Richard Hakluyt’s accounts in his Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discouveries of the English Nation (1589–1600) were matter for poetry, influencing William Shakespeare, who alludes to Fitch in Macbeth (1609): “Her husband’s to Aleppo gone, master o’th’ Tiger” (1.3.6). The new geography, as John Gillies argues in the case of Shakespeare, was central to English poetic imagination, but he rightly observes that classical geography continued to be influential, not the least the enduring fascination exerted by classical others populating the margins of the new maps, and that poets like Shakespeare and Marlowe “combine ancient and Renaissance forms.”35

33 J. William Hebel, “The Preface” to Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (Drayton 1961: 4.viii–ix). Quotations are from this edition and given parenthetically.

34 W. Warner 1597: 297, chap. 71.

35 J. Gillies 1994: 182, 60.

This combination is strikingly brought together by Drayton’s Poly-Olbion, interested in both geography and antiquarianism. Poly-Olbion’s antiquarianism moves beyond places into linguistic and literary concerns to include Arabic printing: a crude woodcut of Alexander’s Arabic name. Drayton’s “Chorographicall Description,” as his subtitle calls it, not only describes the land but also retells ancient stories associated with place. Thus Drayton asked his friend John Selden, hailed by Milton as “chief of learned men,” to provide annotations explaining historical allusions.36 Notable in Selden’s preface, which discusses the reliability of sources, is his long digression on Chaucer. Complaining that Chaucer’s “Learned allusion” has been misunderstood, he proceeds to argue that Chaucer (acknowledged in the early modern period as the fount of English literature) was master of Arabic learning, thus making the English literary tradition entwined with eastern traditions from its imagined origin.

This surprising claim is based on a gloss on a neologism in Troilus and Criseyde (c.1382–5) from lines spoken by Criseyde: “I am till God mee better mind send / At Dulcarnon right at my wits end.”37 Selden rejects the medieval theologian Alexander Neckam’s derivation of “Dulcarnon” from Latin to identify it instead as Arabic:

It is not Necham, or any else, that can make mee entertaine the least thought of the signification of Dulcarnon to be Pythagoras his sacrifice after his Geometricall Theorem in finding the Squares of an Orthogonall Triangles sides, or that it is a word of Latine deduction; but, indeed, by easier pronounciation it was made of يننرقلاوذ .i. Two horned: which the Mahometan Arabians vie for a Root in Calculation, meaning Alexander, as that great Dictator of knowledge Joseph Scaliger (with some Ancients) wills, but, by warranted opinion of my learned friend Mr. Lydyat in his Emendatio Temporum, it began in Seleucus Nicanor, XII. yeares after Alexanders death; The name was applyed, either because after time that Alexander had perswaded himselfe to be Jupiter Hammons sonne, whose Statue was with Rams hornes, both his owne and his Successors Coines were stampt with horned Images: or else in respect of his II. pillars erected in the East as a Nihil ultra of his Conquest, and some say because hee had in Power the Easterne and Westerne World, signified in the two Hornes.38

Chaucer’s Criseyde’s expression of perplexity in the linguistic borrowing is the earliest attestation of Alexander’s Arabic appellation, Dhū’lqarnayn, the two-horned, to appear in English, though Marco Polo mentions it.39 The term, as Chaucer’s sixteenth-century

36 Milton’s praise of Selden appears in Areopagitica (Milton 1953–82: 2.549).

37 Chaucer 1987: Troilus and Criseyde 3.930–1; Selden modernizes the verse.

38 John Selden, “From the Author of The Illustrations,” in Drayton 1613: sig. A3–A3v.

39 Marco Polo also mentions dhū’lqarnayn in his account of Badashan or Badakhshan (Balascian in Latin, situated in today’s southeast Tajiskistan and northeast Afghanistan): “Badashan is a Province inhabited by people who worship Mahommet, and have a peculiar language. It forms a very great kingdom, and the royalty is hereditary. All those of the royal blood are descended from King Alexander and the daughter of King Darius, who was Lord of the vast Empire of Persia. And all these kings call themselves in the Saracen tongue ZULCARNIAIN, which is as much as to say Alexander; and this out of regard for Alexander the Great” (Polo 1903: 1.157). By the time of early modern print editions, dhū’lqarnayn seems to be dropping out of the texts. One of the earliest from Venice has this description: “Balassin e una prouincia econtrada laqual ha lingua per si & adora macometo. Lo regno de Balassia egrande e ua per heredita; questi re sono descesi da lo re Alexandro e da lo re Dario de Persia: e quelli fi appelladi Recultari & ea dir

editor, Thomas Speght, notes, is the name for Euclid’s Book 1, 47th proposition, the Pythagorean Theorem, showing that a square constructed on each side of any right triangle would have the largest square equal in area to the sum of the smaller two: the figure looks as if it has two horns sticking out. In Troilus and Criseyde, Pandarus wrongly associates it with the 5th proposition, known as fuga miserorum: he asserts, “Dulcarnon called is ‘fleminge of wrecches’ ” (3.933). Previous attempts to explain the term fell short of the mark. The first English translation of Euclid, published 1570, offers the explanation of Pythagoras’ sacrifice of oxen, which Selden rejects in the passage above.40 Only in the nineteenth century did Walter William Skeat in his edition of Chaucer point to Selden’s commentary to clear up scholarly perplexity about the word’s origin.41

Selden’s comments on Chaucer go even further. Praising him for the term “dulcarnon” ’s aptness in describing Criseyde’s dilemma, Selden imputes to Chaucer a wider knowledge of Arabic science: “How many of Noble Chaucers Readers never so much as suspect this his short essay of knowledge, transcending the common Rode? and by his Treatise of the Astrolabe (which, I dare sweare, was chiefly learned out of Messahalah) it is plaine hee was much acquainted with the Mathematiques” (xi*). Skeat concurs with Selden’s assessment of Chaucer’s familiarity with Messahalah—the Latin name of Māshā’allāh ibn Atharī, an eighth-century astronomer from Persia, whose work was known in medieval Europe—suggesting the poet’s indebtedness to Māshā’allāh’s work in Latin translation, Compositio et operatio astrolabii (13th century), a standard teaching text in the following centuries.42 Engaged in far more than simply source study, Selden linked the origin of English poetry to Arabic science.

One of a pan-European group of “orientalists,” like his compatriot Thomas Lydiat and Lydiat’s Leiden opponent Joseph Justus Scaliger, Selden’s historical research was profoundly comparative. Two years after the first part of Poly-Olbion, Selden published his Titles of Honour (1614), aiming to collect together all the world’s sovereign titles. Selden’s research was based on correspondence from foreign monarchs, including those from Southeast Asia, to England mediated through the East India Company; using the help of friends with mercantile contacts—Archbishop Laud, Thomas Erpenius, among others—he constructed, as Robert Batchelor calls it, his “globally comparative

in lingua nostra Alexandro amor de re Alexandri grandi” (Polo 1496: sig. c iiiiv). The first English print edition, John Frampton’s translation, omits entirely the sentence about what they call themselves (Polo 1579: 29, sig. C.iii). In the same year, Frampton translated an account of Portuguese voyages to the East Indies and China that he said confirmed Polo’s account (Frampton 1579).

40 H. Billingsley’s translation of Euclid’s Geometry notes: “This most excellent and notable Theoreme was first invented of the greate philosopher Pithagoras, who for the exceeding joy conceived of the invention thereof, offered in sacrifice an Oxe, as recorde Hierone, Proclus, Lycius, & Vitruvius. And it hath bene commonly called of barbarous writers of the latter time Dulcarnon” (Euclid 1570: f. 58, sig. Q.ii).

41 Chaucer 1894: 479–80 n. 931. For dulcarnoun as mathematical architecture for Troilus, see Hart 1981: 129–70. Incidentally, Skeat’s son, with the same name, was an anthropologist of Malaya.

42 Chaucer 1872: xxiv–xxvi.

work on notions of aristocratic authority and sovereignty.”43 Thirty years prior, Scaliger’s innovative work, De emendatione temporum (1583), which Lydiat challenged unsuccessfully, showed what comparative analysis can do, ranging across the geographical scope of ancient history beyond Greece and Rome to include Persia, Babylon, and Egypt, and the Jewish nation.44 Scaliger’s note on dhū’lqarnayn exemplifies the cutting-edge comparative philology of the day in assimilating Arabic sources:

Sed Arabes Muhammedani vocant

. Sic vocatur in Alkorano Surath

sic] Therik dhilkarnain. hoc est

. Nam Alexandrum vocant

. Et ibidem paulo inferius:

, id est, O Alexander. Et auctor valde bonus Geographiae in prima parte Climatis tertij ita scribit: ردنكسلا

. Notum est, quomodo ille Rex credi voluit filius Ammonis. Ab eo igitur Bicornis potius Alexander, quam proprio nomine a barbaris illis vocatus est. Nam nullus est ex media faece Arabum, qui non potius agnoscat Alexandrum de cognomine Bicornis, quam de proprio nomine.45

[But the Arab Muslims call tārikh dhylqarnayn, that is the epoch of the two-horned, either tārikh al-yunānayn or al-yunānayān epoch of the Greeks. For they call Alexander dhūlqarnayn, that is two-horned. Thus is he named in the Qur’ān Sūrah al-Kahf [the Cave]. And in the same place a little later: yā dhūlqarnayn o two-horned, which is, O Alexander. And the very good author of Geography in the first part of the third Climate wrote thus: dhūlqarnayn ya’ani Iskandar o two-horned, that is to say Alexander. It is noted, in which manner that king was able to believe [himself] the son of Ammon. . . . From this, then, he is called rather Two-horned than Alexander, the proper name, by those barbarians. For there is no one from the common dregs of the Arabs who would rather not recognize Alexander from the surname Two-horned than from his proper name.]

As he moves from Latin to Greek to Arabic, Scaliger’s immense erudition is on full display. Showing how Alexander acquired the appellation from his self-representation as the son of Ammon with ram’s horns, found on coins, he emphasizes Muslims’ other name for Alexander, citing for proof the Qur’ān and the author of a Geography, perhaps Muhammad al-Idrīsī (published in Arabic in Rome in 1592, and translated into Latin in 1619), and noting almost universal Muslim use of the appellation. Although he prefers Lydiat’s authority, later in his edition of Egyptian patriarch of Alexandria, Eutychius (Sa’id ibn Batriq, d. 940)’s universal history, Selden grudgingly cites Scaliger’s De emendatione temporum. 46 In incorporating multilingual, and especially eastern, sources, Selden followed Scaliger’s lead.

43 Batchelor, London, 122. See 282 n. 54 on manuscript evidence for Selden’s notes on royal correspondence and other sources that came by way of the East India Company.

44 Grafton 1975 notes that Scaliger was not the first to combine Near Eastern and Classical studies, but in doing so more thoroughly than anyone before he pioneered methodological innovations. The authoritative work on Scaliger’s life and work is Grafton 1983–93.

45 Scaliger 1598: 400–1, sig. Ll 2v–Ll 3. Scaliger spells dhūlqarnayn variously.

46 J. Selden 1642: 159–60. The Arabic word نرق also means “century.”