Introduction:TheMetaphysical SocietyinContext

CatherineMarshall,BernardLightman, andRichardEngland

TheHistoryoftheMetaphysicalSociety(1869–1880)

ThecreationoftheMetaphysicalSocietywassetinmotioninNovember1868 whenthesocietyarchitectandfutureeditorofboththe ContemporaryReview and NineteenthCenturyReview,JamesKnowles,thepoetLaureateLordTennyson, andtheclergymanandastronomerRev.CharlesPritchard,imaginedadebating clubtodiscusstheologicalquestionsusingtherigorousmethodologyofscience. DrawingonthemodelofthefamousCambridgeApostles,thisSocietywould bringtogetheranumberofwell-knownVictoriansinterestedinmakingsenseof thereligiouschangesthatweretakingplaceinmid-VictorianBritaininaspirit offreedomandopenness.Knowlesimmediatelyincludedintheprojectanumber ofreligiousintellectualsfromalldenominations,suchasthehighlyregarded UnitarianJamesMartineau,theCatholicCardinalManning,andthewellknowneditorofthe DublinReview andformermemberoftheOxfordMovement, W.G.Ward.TheyjoinedimportantAnglican figures,includingtheeditorofthe Spectator,R.H.Hutton,theBroadChurchmanDeanStanley,thetheologianDean AlfordofCanterbury,andtheHighChurchbiblicalscholarCharlesEllicott, BishopofGloucesterandBristol.Nevertheless,itsoonbecameclearthatrestrictingthemembershipoftheSocietytobelieverswouldonlystiflerealdebate.Those whorejectedtheexistenceofthesupernaturalinthe1860s,andwhoweresteadily gaininggroundinVictoriansociety,hadtobeallowedtojoin,thebettertoengage usingtheirownmethodologicaltools.

The ‘MetaphysicalandPsychologicalSociety’—itsoriginalname,immediately shortened begantomeetin1869.DuringthelifetimeoftheSociety itslast meetingtookplacein1880 sixty-twoeminentmaleVictorianintellectuals becamemembersandninety-fivepaperswerepresented.¹WhentheSocietywas

¹HenryWentworthAcland,HenryAlford,WalterBagehot,ArthurJamesBalfour,AlfredBarratt, AlfredBarry,MatthewP.W.Boulton,JohnCharlesBucknill,GeorgeDouglasCampbell(Duke ofArgyll),WilliamBenjaminCarpenter,RichardWilliamChurch,AndrewClark,RobertClarke, WilliamK.Clifford,JohnD.Dalgairns,MountstuartElphinstoneGrant-Duff,CharlesJ.Ellicott,

2

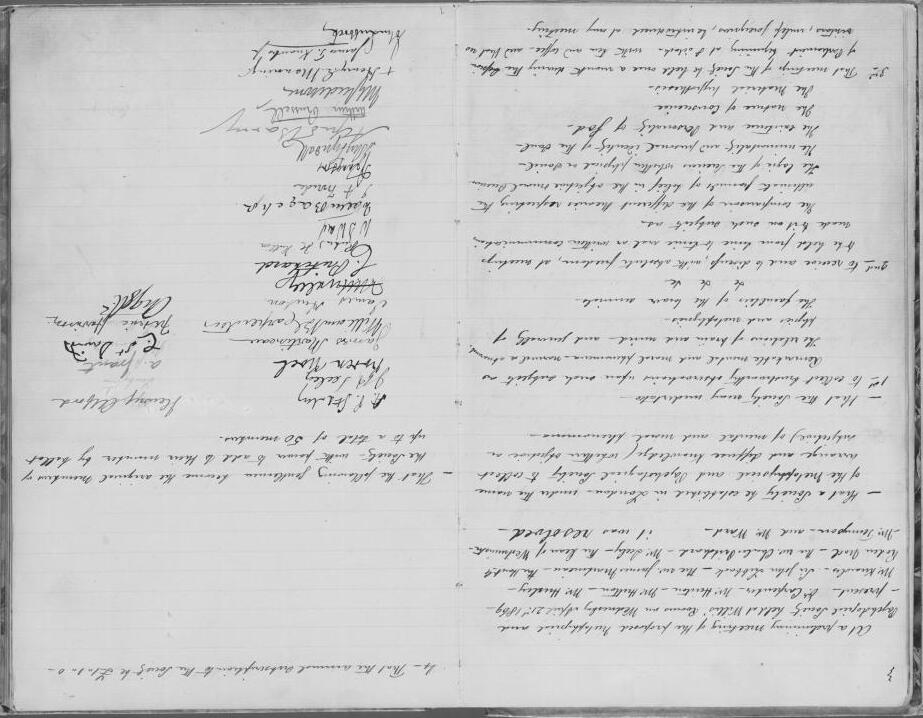

officiallycreatedduringthemeetingof21April1869,thetwenty-sixoriginal foundingmembersoutlineditsgoals.Thenoticeofresolutionstatedthatits primaryaimwasto ‘collect,arrange,anddiffuseKnowledge(whetherobjective orsubjective)ofmentalandmoralphenomena’.TheSocietywasexpectedto ‘collecttrustworthyobservations ’ uponsubjectsrelatedto ‘science ’—essentially natural,empiricalscience and ‘metaphysics’,ortraditionalphilosophicalquestionsaboutthenatureofthingsthatcouldnotbedescribedinanotherway.The secondaimwastoengageinaspiritofwillingnesstolistenrespectfullyandargue freely.Thethirdandfourthaimsstatedthatthemembersweretomeetoncea monthwhenParliamentsatandthatthetotalofthemembersshouldnotexceed fifty(Figure0.1).

Inreality,therewasaconsiderabledifferencebetweenwhatthenoticeof resolutionstatedastheaimsoftheSocietyandthecontentsoftheninety-five paperswhichweregivenovertheelevenyearsofitsexistence.²Forastart,and perhapsmostimportantly,theverydefinitionofthenatureofmetaphysicswas itselfneverfullytackled,leadingtoambiguityaboutthescopeandfocusof discussion.Thediversemembershiphasoftenbeendescribedasagentlemanly eliteofVictoriandebatingamateurs,butthisseemstomisstheimportanceofthe politeatmosphereoftheirgatherings.Thetonethatwasestablishedallowed memberstospeaktheirmindsfreely,butitdidnotresolvetheprofounddisagreementsthatdividedtheSociety.FroudetoldWard ’ssonthatanattitudeofmutual disapprovalexistedintheearliestmeetingsoftheSociety:

Aspeakeratoneofthe firstmeetingslaiddownemphaticallyasanecessary conditiontosuccess,thatnoelementofmoralreprobationmustappearinthe debates.Therewasapause,andthenMr.Wardsaid, ‘Whileacquiescinginthis conditionasageneralrule,IthinkitcannotbeexpectedthatChristianthinkers shallgivenosignofthehorrorwithwhichtheywouldviewthespreadofsuch extremeopinionsasthoseadvocatedbyMr.Huxley.’ Anotherpauseensued,and Mr.Huxleysaid, ‘AsDr.WardhasspokenImustinfairnesssaythatitwillbe

AlexanderCampbellFraser,JamesAnthonyFroude,JosephRaymondGasquet,WilliamEwart Gladstone,AlexanderGrant,WilliamRathboneGreg,GeorgeGrove,WilliamWitheyGull,Frederic Harrison,JamesHinton,ShadworthHodgson,RichardHoltHutton,ThomasHenryHuxley,James Knowles,RobertLowe,JohnLubbock,EdmundLushington,WilliamConnorMagee,HenryEdward Manning,JamesMartineau,FrederickDenisonMaurice,St.GeorgeJacksonMivart,JohnMorley, JamesB.Mozley,RodenNoel,RoundellPalmer,MarkPattison,FrederickPollock,CharlesPritchard, GeorgeCroomRobertson,JohnRuskin,ArthurRussell,JohnRobertSeeley,HenrySidgwick,Arthur PenrhynStanley,JamesFitzjamesStephen,LeslieStephen,JamesSully,JamesJosephSylvester,Alfred Tennyson,ConnopThirlwall,WilliamThomson,JohnTyndall,CharlesBarnesUpton,andWilliam GeorgeWard.Seethebiographicalregisterin ThePapersoftheMetaphysicalSociety1869–1880. ACriticalEdition,editedbyCatherineMarshall,BernardLightman,andRichardEngland(Oxford: OxfordUniversityPress,2015),vol.3,pp.333–48.

²SeeIntroductionin ThePapersoftheMetaphysicalSociety1869–1880.ACriticalEdition, CatherineMarshall,BernardLightman,andRichardEngland,eds.,3vols.(Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press,2015),pp.15–26.

Figure0.1 Thenoticeofresolution.MetaphysicalSociety.Minutebook:manuscript,1869–1880.MSEng1061(vol.1),pp.1–2.Houghton Library,HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,Mass.

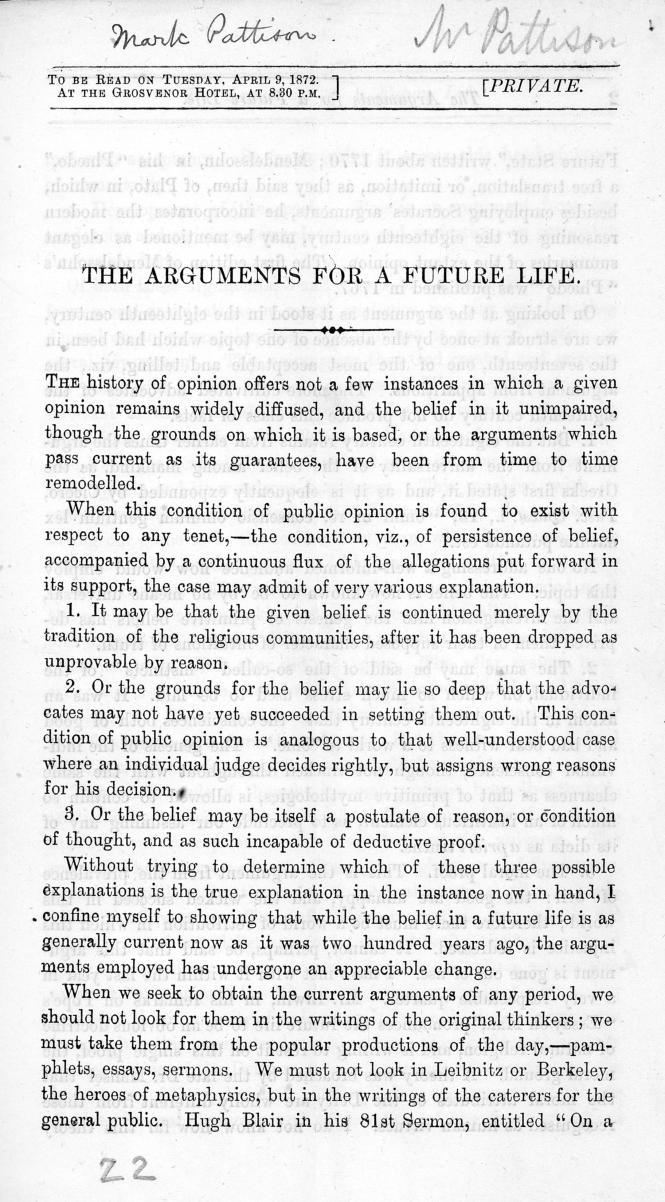

Figures0.2aand0.2b AnexampleofoneoftheSocietypapers.Firstandlastpageof MarkPattison’spapergivenon9April1872andentitled ‘TheArgumentsforafuture Life’.CopyrightclearancekindlygrantedbyHarrisManchesterCollege,Oxford.

Figures0.2aand0.2b Continued

6

verydifficultformetoconcealmyfeelingastotheintellectualdegradationwhich wouldcomeofthegeneralacceptanceofsuchviewsasDr.Wardholds.’ No answerwasgiven;butthesinglespeechoneithersidebroughthomethenand theretoall,includingthespeakersthemselves,thatifsuchatonewereadmitted theSocietycouldnotlastaday.Fromthattimeonwards,saysMr.Froude,no wordofthekindwaseverheard.³

SomethingbroaderthanwasintendedwassetinmotionattheMetaphysical Society ofwhichthemembersthemselveswerenotevenaware thatleftatrace duringandafteritsdemisein1880.

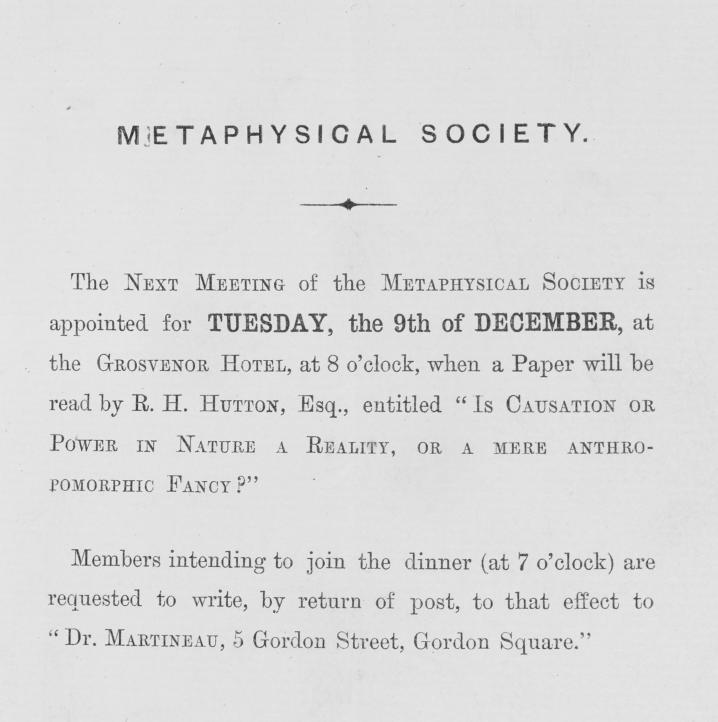

Thethreevolumesofthe2015criticaleditionpresentedtheninety-fivepapers givenattheMetaphysicalSociety.⁴ Mostoftheoriginalpaperswerefoundor retrievedintheirpublishedversion.Thecriticaleditionofthepapersalsodrewon informationminedfromtheMinuteBookoftheMetaphysicalSociety,whichhad beenlostatthebeginningofthetwentiethcenturyandthenlocatedbyRichard EnglandatHarvardUniversity.⁵ TheMinuteBookcontainsarecordofwho attendedeachofthemonthlymeetings.Papersweremarked ‘private’.No nameswereincluded,onlythedate,thetitle,themeetingplace,andtheinstructionsonhowtosendquestionsinadvance(Figures0.2aand0.2b).Thisformat allowedfordiscretionandthereforemoreopendiscussion.Thepaperswere foldedintwoverticallyandsenttoallthemembersbeforethemeetingtoallow questionstobeprepared.Itiseasytoseewhymostofthemwereeitherlostor forgottenasnothinglinkedthemtotheirauthorsortotheMetaphysicalSociety. TheinvitationssentweremorespecificandborethenameoftheSociety,thetitle ofthepapertobegiven,andthenameofitsauthor(Figure0.3).Butveryfew invitationshavebeenfound.

ScholarshavepaidrelativelylittleattentiontotheMetaphysicalSociety,despite theeminentlistofitsmembers.TheonlybiographyoftheSociety,A.W.Brown’ s 1947book,wasperhapstooinfluencedbythecontextofWWIIinitsvisionofthe Societyasamodelforliberalideals.Essentially,therehavebeenveryfewattempts tomakesenseofthemeaningofthepapersasawhole.⁶ Itisonlythroughthework topublishthepapersoftheMetaphysicalSocietybetween2013and2015,thatthe Societycouldbecomethesubjectofnewinterpretations.Onepaperinparticular, ³WilfridWard, WilliamGeorgeWardandtheCatholicRevival (London:Macmillan,1893), pp.309–10.

⁴ Throughout TheMetaphysicalSociety(1869–1880):IntellectualLifeinMid-VictorianEngland, referencestospecificpapersarefrom ThePapersoftheMetaphysicalSociety1869–1880,Richard England,BernardLightman,andCatherineMarshall,eds.Inthosevolumesthepapersarenumbered chronologically.Wesupplythenumberinbracketsforanyreferencestoaspecificpaper.

⁵ SeeMetaphysicalSociety,Minutebook:manuscript,1869–80.MSEng1061(2vols.),Houghton library,HarvardUniversity,Cambridge,MA.

⁶ See ‘Currentscholarship’,inCatherineMarshalletal.,eds., ThePapersoftheMetaphysicalSociety 1869–1880,vol.1,pp.9–14.ForabibliographyofthemostusefulsourcesontheSociety,see ‘Further Reading’,inCatherineMarshalletal.,eds., ThePapersoftheMetaphysicalSociety1869–1880,vol.3, pp.327–32.

Figure0.3 AninvitationtomembersoftheSocietytoattendthemeetingon December9th,1879(#90).PermissiontoreproducegrantedbytheBodleian Library,UniversityofOxford.

BernardLightman’s2013Drakelecture,publishedunderthetitle ‘Scienceatthe MetaphysicalSociety:DefiningKnowledgeinthe1870s’,drewonresearchcarried outonthecollectedworks,andwasthestartingpointofanumberofnewarticles whichhaveshowntheextentoftheresearchstillneededtobedoneinorderto makefullsenseoftheroleoftheMetaphysicalSocietyinthe1870saswellasthe fullextentofitslegacy.⁷ Hemadeclearthatsomethingelsewasatstakewithinthe

⁷ BernardLightman, ‘ScienceatTheMetaphysicalSociety:DefiningKnowledgeinthe1870s’,in The AgeofScientificNaturalism:JohnTyndallandHisContemporaries,MichaelReidyandBernard Lightman,eds(London:PickeringandChatto,2014),pp.187–206;PaulWhite, ‘TheConductofBelief: Agnosticism,theMetaphysicalSociety,andtheFormationofIntellectualCommunities’,in Victorian ScientificNaturalism:Community,Identity,Continuity,GowanDawsonandBernardLightman,eds (Chicago,IL:UniversityofChicagoPress,2014),pp.220–41;CatherineMarshall, ‘Thedebateon vivisectionwithintheMetaphysicalSociety’ , RevueFrançaisedeCivilisationBritannique,Vol19/3,

MetaphysicalSociety,andthiswasthedesireofintuitioniststotakethetoolsof theempiriciststoshowthatwhatwasrevealedcouldalsobetrulyknown.This conflictbetweenthetwosidesoftheargumentwasmuchmoreintensethanwas previouslythoughtandthisiswhatcomesoutofreadingthepapersoneafter another:thestoryoftheMetaphysicalSocietyslowlyunfoldsanditsrealmeaning canberetrieved.Ifthecriticaleditionofthepaperswasa firstmovetomakethe primarysourcesoftheSocietyavailabletoscholars,thisvolumedrawsdirectlyon thepapersthemselvestogivetheMetaphysicalSocietyitsfullplaceinthehistory oftheideasofthe1870s.Thiscollectionalsomakesitclearthatastudyofthe MetaphysicalSocietyisbestdealtwithbyscholarswhocomefromdifferent fields, aswellasdifferentcountries.Onlyaninterdisciplinaryapproachcanmakesense ofthismultifacetedgroupwhosepapersstillhavemanytreasurestoreveal.

TheChapters

Thecontributorstothisvolumeareintellectualhistoriansaswellashistoriansof philosophy,science,religion,andpolitics.TheywereaskedtodevelopindependentstudiesofsomeofthediverseaspectsoftheMetaphysicalSociety’sdynamics, discussions,andcharacters.Thechaptersareorganizedinthreesections,which addressthefollowingquestions.

• HowdidtheSociety’smembersengagewitheachother,thepublic,andwith contemporaryconceptsoffreedomofexpressionandtoleration?

• Howdidtheyrespondtotheclaimthattheuniformityofnaturecouldnotbe interruptedfromarealmbeyondit?

• Towhatextentdidtheepistemologicaldividebetweenempiricismand intuitionismshapetheargumentsamongthemembers,aswellasinform attemptsatreconciliation?

Therearemanywaysthatthechapterscouldhavebeenorganized,butthese centralthemescanhelpusgainnewinsightsintothedynamics,sources,and significanceoftheMetaphysicalSociety.

The firstsection, ‘SocietyandthePoliticsofEngagement’,consistsofstudies rootedintheSociety’sdifferentsocialaspects.BruceKinzer’sessayontheimpact ofJamesFitzjamesStephen’sbluntrhetoricandcombativecourtroommanner showshowhebludgeonedhisRomanCatholicopponents,whomheconsidered

Nov.2014,pp.26–42;CatherineMarshall, ‘La MetaphysicalSociety (1869–1880):Uneassociation discrèteauservicedelasociétévictorienneouuncercled’intellectuelsutopistesvouésàl’échec?’ , Dans lesalléesdupouvoir,sociétés «discrètes »,cerclesderéflexionetgroupesdepression,FrançoisPernotand JulianZarifian,eds(LaPlaineStDenis:Editionsdel’Amandier,2015),pp.43–56.

intellectuallydishonest.Stephen’santipathytoCatholicismwaslinkedtohis nationalismandhismistrustoftheCatholicChurch’sdogmatism.Hismany paperswereconsistentandstronglyargued,butKinzernotesthathisapproach challengedthespiritoftolerationandoptimismthathadinspiredthecreationof theMetaphysicalSociety.

ThisspiritcertainlyhadhelpedtheSocietyfunctionasanetworkforauthors andeditors,aswellasahubforintellectualexchange,asCatherineMarshall explainsinheressay.BrownandothershavenotedthatJamesKnowleswasthe pre-eminenteditorofthegroup,publishingmanyofitspapersinthe Contemporary Review and(later)the NineteenthCentury.Marshallwidensthefocushereby exploringtherangeofinteractionsbetweenthemanyMetaphysicalSocietymembers whowereeditorsandauthorsofpapersthat firstappearedattheirmeetings,and werelaterdisseminatedinoneofmanyjournals.Shealsodrawsattentiontotheways thatthe ‘newjournalism’ oftheperiodwasaffectedbytheSociety’smembers.As Marshallnotes,thereismuchroomforfurtherstudyoftheconnectionsbetweenthe editorsandauthorswhowerepartofthiseliteintellectualclub.

TheSocietyfunctionedinthiswayinpartbecauseofanoriginaldedicationto freedebate,reason,andtoleration,whichBrownidentifiedastheliberalcoreof itsidentity.AndrewVincentraisesquestionsaboutthisclaim,andexaminesthe differentconceptionsofliberalismthatwereexploredbysomeofitsmembers.Contra Brown,heconcludesthatthereweretoomanyvarietiesofliberalismtojustify theclaimthatithadaunifyingfunction,andfurther,Vincentcontendsthatthe veryideaofliberalismwasinastateofconceptualfermentinthe1870s.Setagainstthe backdropoftheevolutionofGladstonianliberalismandradicalism,hemakesa convincingcasethatwhiletheMetaphysicalSocietymighthavebeeninfluencedby diversestrainsofliberalism,itwasnotahomogenouslyliberalenterprise.

TheSociety’sdiversityisalsoexploredinthenextgroupofessays,underthe title, ‘Miracles,UnseenUniverses,andNaturalCauses’.Hereweturnfromthe socialdynamicsoftheMetaphysicalSocietytothemetaphysicalcontentofits debates.TheproblemofmiraclesinitsmodernformhadbeensetoutbyDavid Humeinthelateeighteenthcentury:heheldthatitwouldbeeffectivelyimpossibleforthetestimonyofwitnessestoamiracletooutweightheauthorityofour widespreadexperienceoftheunvaryinguniformityofnaturallaw.Theproblem wasimportanttoVictoriandiscussionsofscienceandreligion,andhadbeenso formanydecadesbeforetheSociety firstconvenedin1869.⁸

Inthe firstessayofthissection,GowanDawsonoffersadetailedaccountofthe sources,compositionandafterlifeofThomasHuxley’sMetaphysicalSocietypaper on ‘TheResurrectionofJesusChrist’.Huxleyfollowedseveralofhiscontemporaries inadvocatingwhatwasknownasthe ‘swoontheory’,theargumentthatChristhad

⁸ SeeRobertMullin, MiraclesandtheModernReligiousImagination (Princeton:PrincetonUniversity Press,1996).

notdied,butmerelylostconsciousnessonthecrossandbeenrevivedthereafter. Huxley’spaperwasnotpublished,althoughtheargumentdid finditswayintoan appendixofhisvolumeon Hume.Thiswasseizeduponbysomefreethinkers,who usedittomockChristianity,confirmingthefearsofsomewhofeltthatHuxley’ s authoritymightbemisappropriatedinthisimpoliteandimpoliticmanner.Huxley’ s rejectionofthemiracleoftheResurrectionrepresentsthehigh-watermarkof respectfulscepticismattheSociety’smeetings,andmanifeststhefundamental assumptionthatscientificauthorityoughttobebroughttobearonanyhistorical orscientificclaimsreligionsmake.

RichardEngland’spapershowshowsuchnaturalisticassumptionswererejected bytwoprominenttheologians.TheUnitarianleaderJamesMartineauandthe ColeridgeanBroadChurchmanFrederickDenisonMauricedidnotdirectlyaddress miracles,butbotharguedthatnatureandnaturallawwereexpressionsofthedivine. Martineauclaimedthattheideaofcausationwasderivedfromourownexperience ofexercisingourwilltoeffectchangeintheworld,andfromthisheconcludedthat allnaturalcausationdependedonthewillofGod.Mauricefoundevidenceofa divinegovernmentbehindnaturethroughaphilologicalreflectiononthewaythat theterms ‘nature’ and ‘supernatural’ areused.Intheend,forbothMartineauand Maurice,naturallawbecomespartofaworldviewinwhichGodistheultimate sourceofboththenaturalandthemoralorder.

Inmoredirectdiscussionsofmiraclestheselargermetaphysicalapproaches weregenerallyabsent,andmuchmoreattentionwasgiventoevidenceandto whichexpertshadtheknowledgeandauthoritytojudgeit.AnnDeWitt’ spaper showsthatwhiletheMetaphysicalSocietyparticipantsagreedthatexpertisewas important,theydifferedonwhichparticularexpertshadarighttospeak,a disagreementwhichmadeproductivedialoguedifficult.Acrossarangeofpapers membersappealedtovariouskindsofexpertise:notonlyscientific,theological,or historical,butalsolegalandartistic.Whilesomeclaimedthatthereweremoral reasonstolistentoparticularkindsofexpertclaims,otherswerecriticaloftheir attempttoseizetheinterpretiveandmoralhighground.DeWitt’spaperidentifies asharedinterestinexpertise,thepracticaleffectofwhichseemstohavebeento providethoseonopposingsidesanothersetofpointstodisagreeabout.

Whiletheargumentsforandagainstmiraclesoftenfocusedonthepossibilityof thesupernaturalinterruptingthenaturalorder,therewasalittle-known ‘third way ’ whicharguedforamorepurelyphilosophicalmethodinconsideringthe relationofphenomenalnaturetoaworldbeyondthephenomenal.William Mander’sessay,ontheratherdifferentapproachesofthephilosopherShadworth HodgsonandthemathematicianWilliamClifford,showstheirfundamentalagreementthataworldbeyondourowncouldbeinferredphilosophically,without restingonorthodoxfaith.Hodgsonheldthattheuniformityofnaturewasnot simplyamatterofexperience,butanapriorilogicalaxiom,whichheconnectedto thenecessaryexistenceofanunseenworldthatlaybeyondtheworldofthesenses.

Clifforddevelopedargumentsformonismandpanpsychism theideathatmind andmatterweredifferentaspectsofthesamefundamentalsubstance:tohimthis demonstratedthatourexperienceofthematerialworldwasonlyoneaspectofa largerreality.Matterhadmindbehindit,andwhileforCliffordthishadnothingto dowiththeology,itdidmakehimabelieverinaknowable,unseenworldofmind thatwastiedtothematerialrealm.WhileHodgsonandCliffordhadlittleimpacton philosophy,theirideaswereingeniousandoriginalcontributionsthatstretched beyondthetraditionalpositionsinthedebateonmiracles.

The finalsectionofthevolumeisdevotedtomappingtheboundariesof empiricism theideathatthesensesandexperiencealoneprovideuswith knowledge andintuitionism theviewthatthehumanmindhasinnatepowers andideasthatdonotdependonexperience.Whilediscussionsofmiraclesandof evolutionarewellknown,theepistemologicalaspectofVictorian ‘scienceand religion’ hasonlyrecentlybeenexploredbyscholars.⁹ Inthelateeighteenth century,Hume’sscepticalempiricismhadprovokedresponsesfromImmanuel Kantandhisidealistfollowers,aswellasfromThomasReidandtheCommon Senseschoolofphilosophy.Bythe1830sand1840s,thedebatecontinued,with JohnStuartMillandComteanpositivistspromotingempiricism,whileWilliam WhewellandWilliamHamiltondefendedintuitionism.Mill’ s ExaminationofSir WilliamHamilton’sPhilosophy (1865),acomprehensiveattackonintuitionist psychologyandphilosophy,ranthroughseveraleditionsandinspiredseveral discussionsattheMetaphysicalSociety.

Astheessaysinthissectionshow,thisconflictplayedoutindiverseways.Ian HeskethrelatestheriseandfallofevolutionaryethicsattheSocietytothedivision betweenthosewhothoughtthatmorality’snaturaldevelopmentmeantthatit couldbeexplainedandjustifiedscientifically,andthosewhoheldthatitwas rootedinfundamentalintuitions,andsocouldnotbereducedtoexperienceand history.Thesepositionsledtodivergentviewsofwhatcountedashistoricaland socialevidencerelevanttothestudyofmorality.Ultimately,themoralphilosopherHenrySidgwickpuncturedthepretensionsoftheempiricistsbypointingout thateveniftheoriginsofethicalbehaviourcouldbedescribed,suchanaccount couldnotjustifythemoralprinciplesitsoughttoexplain.

AnevolutionaryturnalsoinformedtheeffortsofWilliamCarpenter,theprominentUnitarianphysiologistwhosoughttoreconcileempiricismandintuitionism. InpapersgivenattheMetaphysicalSociety,aswellasinhis1872presidential addresstotheBritishAssociationfortheAdvancementofScience,heoffered anexplanationofhowintuitionshadevolved.AsPiersHalediscussesinhis chapter,Carpenterwastryingtoshowthatsciencecouldexplainhowthehuman

⁹ Seeforexample,LauraSnyder, ReformingPhilosophy:AVictorianDebateonScienceandSociety (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,2006),andMatthewStanley, Huxley’sChurchandMaxwell’ s Demon:FromTheisticSciencetoNaturalisticScience (Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress,2014).

mindandcharacterhadformed,andthatthiswouldcomplementreligious explanationsofwhysuchintuitionsweresignificantinthemoralorder.Carpenter didnotconvinceHuxleythathisrapprochementwassuccessful,andhisreligious mentor,Martineau,wasalsodubiousaboutthismove.However,somemembersof theMetaphysicalSociety,suchastheCatholicCardinalHenryManning,weremore receptive,andclaimedCarpenter’sexplanationfortheirowninterpretationofthe importanceofintuition.

WilliamSweetoffersadetailedexaminationofthedevelopmentofManning’ s viewsonintuitionandhisviewoftheirimportanceforreligiousbelief.While Manningheldthatintuitionscouldnot,bydefinition,beprovenorjustified,he alsothoughtthattheycouldbeconfirmedbythelightofreason,andsocould providearationalfoundationforreligiousbelief.Drawingonearlytextsby ManningaswellaspapershecontributedtotheSociety,Sweetshowsthatwhile Manning’sintuitionismwascomplex,andambiguousinplaces,itwasakeypart ofhisworkasaChristianapologist,especiallyashedefendedtheauthorityof Romeagainstliberalsandunbelieversalike.

The finalpaperofthevolumealsofocusesontheCatholiccontributorsto theMetaphysicalSociety.BernardLightmancomparestheworkofCardinal Manning,WilliamWard(thelay-editorofthe DublinReview),andSt.George Mivart,(manofscienceandliberalCatholicessayist).Allthreeheldthatsome basictheisticintuitionswereessential,notonlytoreligiousbelief,butalsotothe scientificenterprise.Theyallattackedscientificnaturalismashavingaweak metaphysicalfoundation,andpromotedtheviewthatCatholicismhadamuch morecoherentandjustifiablephilosophicalbasis.Here,though,theiremphasis differed:Manning’sintuitionismwas flavouredbyhiscommitmenttoaversionof neo-scholasticphilosophy.Wardpreferredtoengagewithcontemporarysceptical thinkers(suchasMill)byarguingforcertainkindsofintuitionwhichwereeither logicallynecessaryorclearlynotjustifiedbyexperience.Mivart,unlikeManning andWard,triedtoreconcileevolutionarytheoryandfreedomofexpressionwith hisfaith.Hisargumentthatatheisticpostulatewasnecessaryforthevaluesthat sustainedsciencewasaimedathisestrangedmentor,Huxley,althoughhefailed towinoverscientificnaturalists,andultimatelyfelloutwiththeultramontane conservatismofRome.Whileallthreewereintuitionists,Lightmanrevealsthe diversecharacteroftheargumentssetforthwithinthissmall,butvocalsectionof theMetaphysicalSociety’smembership.

MovingForward

Asawhole,thiscollectionmovesbeyondAlanWillardBrown ’spioneeringstudy oftheMetaphysicalSocietybyofferingamoredetailedanalysisofitsinner dynamicsanditslargerimpactoutsidethediningroomattheGrosvenorHotel

(inthelastmeetingsin1880,theMetaphysicalSocietymovedtotheGrosvenor Galleryrestaurant).Itcastslightonmanyofthecolourful figureswhojoined theSociety,aswellasthealliancesthattheyformedwithfellowmembers.The collectionalsoexamines,withfresheyes,themajorconceptsthatinformedthe paperspresentedattheMetaphysicalSocietymeetings.Bydiscussinggroups, importantindividuals,andunderlyingconcepts,thechapterscontributetoa rich,newpictureofVictorianintellectuallifeduringthe1870s.

ManyofthechaptersfocusonindividualSocietymembers,usingtheirpapers toprovidenewinsightsintotheirviews.Inthecollectionwehavenuancedstudies ofJamesFitzjamesStephen,Huxley,Martineau,Maurice,Hodgson,Clifford, Carpenter,Manning,Ward,andMivart.Whilesomeofthese figuresarewell knowntoscholars,others,suchasHodgson,Clifford,andCarpenter,have receivedrelativelylittleattention.ThesestudiesmakeclearthattheMetaphysical Societycannotbedividedintotwoclear-cutgroups.Manyscholarshavefollowed Brown’sleadinidentifyingthesetwogroupsastheintuitionists(usuallyChristian believers)andtheempiricists(usuallyinsympathywithscientificnaturalism).But thesituationwasfarmorecomplicated.AsMandershows,HodgsonandClifford wereattemptingtopursueametaphysicalpaththatdifferedsignificantlyfrom theirSocietycolleagues,whileHalepaintsanintriguingpictureofCarpenteras attemptingtobuildbridgesbetweenthescientificnaturalistsandChristianmetaphysiciansinhissearchforatheisticsciencethatweddedreligiousbeliefto modernscience.ManderandHaleremindusthatthereweremorethantwo groupswithintheMetaphysicalSociety,andthatFrankTurner’ s BetweenScience andReligion (1974)continuestoberelevantforunderstandingVictorianintellectuallifeinthesecondhalfofthecentury.¹⁰ Turnerarguedthatintellectuals, suchasAlfredRusselWallace,SamuelButler,GeorgeJohnRomanes,andHenry Sidgwick(theonlymemberoftheSociety)didnotidentifywithscientificnaturalismorChristianity.Futureworkonotherlesswell-known figuresintheSociety, suchasRodenNoel,Hinton,Froude,andBagehotwilllikelyturnupmore individualswhoarenotsoneatlyplacedinthetwomaingroups.

EvenifweputasidethosemembersoftheSocietywhowerebetweenscienceand religionandturnourattentiontothetwogroups Christiansandunbelievers thereisevidencethattheywerenotasunitedasitmightseem.JamesFitzjames Stephenisgenerallygroupedwiththeunbelievers.ButKinzer’sdiscussionof Stephen’saggressivetacticsrevealsthathewasalonewolf.Relishinginthe destructionofhisenemies,especiallytheCatholicswhoheviewedasdishonest, defectivereasoners,hefrustratedtheattemptsbymostSocietymembersto approachtheiropponentswithrespect.AsEnglandpointsout,thereweresignificantdifferencesamongtheunbelievers,whoincludedpositivists,pantheists,and

¹⁰ FrankMillerTurner, BetweenScienceandReligion:TheReactiontoScientificNaturalisminLate VictorianEngland (NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress,1974).

scientificnaturalists.Similarly,hiscomparisonofMartineauandMauricemakes itclearthattheChristians,dividedbytheirdenominationalaffiliations,werea diversegroup,withcommitmentstodifferenttypesofargument.Eventhose withinoneChristiandenominationcoulddisagreeonastrategytopresenttheir position.Lightman’scomparisonoftheCatholics,Manning,Ward,andMivart, highlightsthedifferencesintheirresponsestotheriseofnaturalism.Inthis collection,theMetaphysicalSocietyemergesasevenmorefragmentedthan previouslythought.

Thisfragmentationcanalsobeseeninthedisagreementaboutsomeofthekey conceptsunderlyingthedebateswithintheSociety.Hereagainthecollection raisesquestionsaboutBrown’sdepictionoftheSociety.ForBrown,workinginthe post-WorldWarIIera,oneformofliberalismistheunifyingthemeoftheSociety. If,asBrownargues,theSocietycouldbeneatlydividedintotwocamps,empiricistsandintuitionists,alongepistemologicallines,thenitmightbeexpectedthat theempiricistswereunitedbyasharedcommitmenttoliberalism.However,as Vincentshows,therewasnosingleacceptedconceptofliberalismamongSociety members,eventhosesupposedlywithintheempiricistcamp.Brown’ s ‘essentialism’ overlookshowanumberofliberalismsunderpinnedSocietydebates,includingBenthamitephilosophicradicalism,Millianprogressiveutilitarianliberalism, Spencer’sLamarckianevolutionaryliberalism,thenaturalscience-orientedliberalismofHuxleyandhisallies,Sidgwick’seclecticacademicizedliberalismand FitzjamesStephen’saustereanti-democraticrationalisticliberalism.Similarly, thoseconsideredbyBrownasintuitionistsdidnotshareacommonconceptof intuitionism.SweetarguespersuasivelythatwhileManningandseveralofthe otherChristianmembersoftheSocietyembracedtheterm ‘intuitionist’,there weresignificantdifferencesamongthemthatleadtochallengesinarticulating whatintuitionisminvolved.Sweetconcludesthatthelabel ‘intuitionist’ was adoptedbyManningandotherChristiansmoreasacounterpointtoempiricism ratherthanasafullydevelopedepistemologicalview.LikeEnglandandLightman, Sweetarguesthattherewasadiversityofvoiceswithinthereligiouscamp, developingthepicturepresentedbyJamesLivingstoninhis ReligiousThought intheVictorianAge ofthecomplextheologicallandscapeexistingintheVictorian period.¹¹ThediversityofliberalismspointedtobyVincentismirroredbythe rangeofintuitionismsanalysedbySweet.

InpresentingtheSocietyasmorefragmentedthanusuallyimagined,the chapterspointusinthedirectionofamorenuancedviewofthe1870s.This decade,thecollectionreveals,wascharacterizedbyimmenseconceptualchange, whichpresenteddifficultiesarrivingatanyconsensusonhowtodealwithit. Vincentarticulatesthispointprimarilyinrelationtothecrisisinpoliticalthought,

¹¹JamesC.Livingston, ReligiousThoughtintheVictorianAge:ChallengesandReconceptions (NewYorkandLondon:Continuum,2007).

butherecognizesitappliedequallyacrosstheboard.The1870swereaperiodof ferment,amomentofcrisisofconceptualmeaningsinsocial,political,religious, andscientificthought.Itwasalsoatimeofincreasingspecialization.Hesketh drawsourattentiontohowthedebateaboutevolutionhadshiftedgroundfrom argumentsoveritsscientificvalidityinthesixtiestotheissueofitswidersocial andphilosophicalapplicabilityintheseventies.Formany,thiswasadisturbing developmentthattouchedtheentiregamutofintellectualactivity.AsDeWittand Dawsonshow,anassertionofdisciplinaryexpertisewasnecessaryforclaiming authorityinaperiodofintellectualupheaval.Thedebateovermiraclesinthe MetaphysicalSociety,theyargue,wasalsoadisputeoverissuesofexpertiseand culturalauthority.DeWittdiscusseshowmembersoftheSocietyclaimedauthorityforspeakingaboutmiraclesonthebasisoftheirrespectiveknowledgeof theology,orhistory,orthelaw,orpsychology,orbiology.Dawson’sexamination ofHuxley’snotoriouspaperontheResurrectionmakesitclearthatclaimsto expertisewerenot,intheend,successful.ThestoryofHuxley’ s ‘Evidenceofthe MiracleofResurrection’ demonstratestheincongruitybetweentheSociety’selitist modelofauthorityandtheemergenceofthenewpoliticsofmassdemocracyin lateVictorianBritain.EventhoughtheeditorsoftheMetaphysicalSociety ampli fiedthedebatesthattookplacemonthlyinWillis’srooms,asMarshall asserts,theyalsousedtheirpublicationstotaketheirargumentsoutsidethe Society.Theirdisagreementshadaneditorialvalueanddiffusedtheideasofthe Metaphysiciansintosocietyinwayswhichhavebeenpreviouslyoverlooked.

ThethemesofexpertiseandauthoritybringusbacktoFrankTurner’sscholarship,butthistimetohis ContestingCulturalAuthority.¹²HereTurnerargues that,throughouttheVictorianperiod,theAnglicanclergyandscientificnaturalistsviedwitheachothertobeconsideredtheintellectualleadersofthenation. LikeBrown,TurnerdividestheVictorianintelligentsiaintotwodistinctgroups. Turner’snotionofacontestforculturalauthorityisstilluseful,butitneedstobe rethoughtifwearetounderstandthemorecomplicatedsituation.Asthechapters inthiscollectionshow,thefragmentednatureofintellectuallifeinatimeofgreat fermentisreflectedintheMetaphysicalSocietydebatesandintheirpublications. Ratherthanseeingacontestforculturalauthoritybetweentwocompetinggroups, anexaminationoftheSocietyrevealsthattherewerereallymanydistinctgroups seekingauthoritywhoadopteddiversestrategiestoobtainit.

¹²FrankM.Turner, ContestingCulturalAuthority:EssaysinVictorianIntellectualLife (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1993).