ListofIllustrations

0.1. LaSaladelConsigliodeiDieci,GabrieleBella.Reproducedwith permissionoftheFondazioneQueriniStampaliaOnlus,Venice10

2.1. TheEntryoftheFrenchAmbassadorinVenicein1706,LucaCarlevarijs. ReproducedwithpermissionoftheRijksmuseum,Amsterdam 67

2.2. IlBroglioelaPrimaVestizionedellaToga,GabrieleBella.Reproduced withpermissionoftheFondazioneQueriniStampaliaOnlus,Venice 70

3.1. LaSaladeiTreCapidelConsigliodeiDieci,GabrieleBella.Reproduced withpermissionoftheFondazioneQueriniStampaliaOnlus,Venice 91

4.1.CharlesVCryptogram,AgostinoAmadi©ArchiviodiStatodiVenezia130

4.2.LettereDiabolicheandotheralphabets,AgostinoAmadi©Archivio diStatodiVenezia 131

4.3.PietroPartenio’sFirstCipher©ArchiviodiStatodiVenezia 149

4.4.PietroPartenio’sSecondCipher©ArchiviodiStatodiVenezia 151

5.1. TheSpy or Curiosity,FrancescoPianta.ScuolaGrandediSanRocco, Venice.©CameraphotoArte 159

5.2. Spy,CesareRipa 160

5.3. TheRainbowPortrait,IsaacOliverorMarcusGheeraertstheYounger. ReproducedwithpermissionoftheMarquessofSalisburyHatfield House,Hertfordshire,UK/BridgemanImages 161

6.1. TribunaleSupremo,GabrieleBella.Reproducedwithpermission oftheFondazioneQueriniStampaliaOnlus,Venice 192

Introduction

OntheeveofthefourthOttoman-VenetianWar(1570–3),amanclaimingtobea fugitiveslaveontherunfromtheOttomanstravelledtoVenicetoinformthe authoritiesofsomealarmingnews.HehaddiscoveredthattheTurkisharmada wasstockinguponmunitionsanddisgorginglargewarfarereservesinAnamur,a fortressonthesoutherncoastofTurkey.Itwasfearedthattheseostensibly militarypreparationswereintendedforanattackonCyprus,aVenetiancolony ashortsailawayontheoppositeshore.Anxioustomake ‘appropriateprovisions forthedefenceoftheisland’,thenoneofVenice’smostprizedpossessionsinthe Mediterranean,theCouncilofTen thegovernmentalcommitteeresponsiblefor thesecurityofVeniceanditssprawlingdominion tookthefollowingactions: withgreaturgency,theypostedtheinformant’swrittendeclarationtothegovernorofCyprus,orderinghimtoverifythewrittenclaimsbysendingoutspiesto confirmthepresenceofamilitarybuild-upinAnamur.Theyalsodemandedthat thegovernorreportback,insecret,throughletterssentbybothlandandsea.¹ Then,theycontactedtheVenetianenvoyinConstantinopleknownasthe bailo² askinghimtoconductaparallelsecretinvestigation.Inparticular,theywere keentoknowwhethertheinformantcouldbetrusted.Toascertainthis,they instructedthe bailo toidentifyandinterviewotherslavesintheOttoman capital.Moreover,the bailo wasentrustedwiththesensitivedetailthatthe VenetianambassadortotheHolyRomanEmperorhadalsolearned,through hisownsources,ofanimminentOttomaninvasionofCyprus.³Asaresultofthis

¹ASV,CX, DeliberazioniSecrete,Reg.9,c.33r.(21Oct.1569).

²OntheVenetianBailoinConstantinople,seeVincenzoLazari, ‘Cenniintornoallelegazionivenete allaportaottomananelsecoloXVI’,inEugenioAlbèri(ed.), Relazionidegliambasciatorivenetial Senato,SeriesIII,Vol.III(Florence:SocietàEditriceFiorentina,1855),pp.xiii–xx;TommasoBertelè, IlpalazzodegliambasciatoridiCostantinopoliaVenezia (Bologna:Apollo,1932);PaoloPreto, ‘LerelazionideibailiaConstantinopoli’ , IlVeltro 23(1979),pp.125–30;CarlaCocoandFlora Manzonetto, BailivenezianiallaSublimePorta:Storiaecaratteristichedell’ambasciatavenetaa Constantinopoli (Venice:StamperiadiVenezia,1985);EricR.Dursteler, ‘TheBailoinConstantinople: CrisisandCareerinVenice’sEarlyModernDiplomaticCorps’ , MediterraneanHistoricalReview 16, no2(2001),pp.1–30;StefanHanß, ‘BailiandAmbassadors’,inMariaPiaPedani(ed.), IlPalazzodi VeneziaaIstanbuleisuoiantichiabitanti/İstanbul’dakiVenedikSarayı veEskiYaşayanları (Venice: EdizioniCa’ Foscari,2013),pp.35–52;EmrahSafaGürkan, ‘LayingHandson ArcanaImperii: VenetianBailiasSpymastersinSixteenth-CenturyIstanbul’,inPaulMaddrell,ChristopherMoran, IoannaIordanou,andMarkStout(eds.), SpyChiefsVolumeII:IntelligenceLeadersinEurope,the MiddleEast,andAsia (WashingtonDC:GeorgetownUniversityPress,2018),pp.67–96. ³ASV,CX, DeliberazioniSecrete,Reg.9,c.33r./v.(21Oct.1569).

Venice’sSecretService:OrganizingIntelligenceintheRenaissance.IoannaIordanou,OxfordUniversityPress(2019). ©IoannaIordanou.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198791317.001.0001

intricatewebofintelligencecollectionandexchange,theTen’sworstfearswere sooncorroborated.Shortlyafter,the bailo sentalettertotheTenconfirming thegruesomenewsthattheOttomanswere,indeed,feverishlypreparingtoinvade Cyprus.Nowonawarfooting,theTencontactedtheirambassadorinSpain,to solicitsupportfromthepowerful recatholico,PhillipII.⁴

ThisepisodeisredolentoftwosignificantconceptsthatarecentraltoRenaissanceVenice’seconomic,political,andsocialconductandtothisbook:intelligenceandorganization.Intermsofthe firstconcept,itisrepresentativeofwaysin whichsensitiveinformation primarilyofmilitaryandpoliticalvalue wascommunicatedsecretlybetweentheVenetianauthoritiesandtheirformalstaterepresentativesstationedoverseas.Buttowhatextentisthistypeof ‘sensitive’ informationanditsclandestinecommunicationindicativeof intelligence,its practiceandcraft,intheRenaissance?Thisquestionencapsulatesthefundamentalissuesassociatedwiththestudyofearlymodernintelligence,whichare,infact, morecomplicatedthanascholarofmodernintelligencemightenvisage.Aswill becomeapparentthroughoutthisbook,definingintelligenceasahistoricalphenomenonisproblematic.Indeed,whatexactlyconstitutesintelligencethroughout history?Isitastateaffairoraprivateinitiative?Aprofessionalserviceoracivic duty?Anactofinstitutionalloyaltyorof financialneed?

Intheearlymodernperiod,intelligencewasamultivalentterm,entailingallof theabove.ForVenetians,theword intelligentia meant ‘communication’ or ‘understanding’ betweenaminimumoftwopeople,sometimesinsecret.Within thecontextofstatesecurity,itindicatedanykindofinformationofpolitical, economic,social,orevenculturalvaluethatwasworthyofsecrecy,evaluation,and potentialcovert(attimesevenovert)actionbythegovernmentinthenameof statesecurity.⁵ Inessence,then,thereweretwoaspectstotheterm ‘intelligence’ . The firstdenotedthesystematicprocessofsecretlycollecting,analysing,and disseminatinginformation.Thesecondrelatedtoa ‘“policeandsecurity” dimension’,whichcouldmanifestbothoffensivelyanddefensively.⁶ Thesede finitionsof ‘intelligence’ willbeusedthroughoutthisbookinanefforttoexplorethemeaning andpurposeofthiswordfordifferentactorsinthatperiod.Buthowwassuch informationdisseminatedtoitsintendedrecipientsintheearlymodernera?

Thisleadsustothesecondcentralconceptofthisbook,organization.Asthe Anamurepisodedemonstrates,inearlymodernVenice,thesystematicorganizationofthecollection,communication,andevaluationofsensitiveinformation wasadministeredbytheCouncilofTen,thegovernmentalcommitteeoverseeing thesecurityoftheVenetianstate.AsVenice’sspychiefs,inanexemplarydisplay

⁴ Ibid.,c.37r./v.(26Oct.1569).

⁵ InhisstudyoftheStuartregimeinearlymodernEngland,AlanMarshalloffersasimilar definition.SeeAlanMarshall, IntelligenceandEspionageintheReignofCharlesII,1660–1685 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1994),p.3.

⁶ Ibid.

ofpoliticalandorganizationalmaturity,theCouncilofTendevelopedand administeredanelaboratesystemofinformation flowwithandbetweentheir informantsandotherunderlings.Toachievethis,theyoversawandmanageda far-flung,yetinterconnectednetworkofprivateinformantsandpublicservants whoserolewastosupplythemwithvitalintelligenceforthepoliticaland,by extension,economicconductoftheVenetianRepublic.⁷ Infact,whileinmost ItalianandEuropeanstatesintelligenceoperationswereorganizedbypowerful individualsintheireffortstosecureandconsolidatepoliticalpowerandcontrol,⁸ theVenetianCouncilofTencreatedandsystematizedoneoftheworld’searliest centrallyorganizedstateintelligenceservices.Thisproto-modernorganization resembledapublicsectorbodythatoperatedwithremarkablecorporate-like complexityandmaturity,servingprominentintelligencefunctionssuchasoperations(intelligenceandcovertaction),analysis,cryptographyandsteganography, cryptanalysis,andeventhedevelopmentoflethalsubstancessuchaspoison.

Tothisday,nosystematicattempthasbeenmadetoanalysetheorganizationof Venice’ssecretservice.PaoloPreto’sworkonVenice’sspiesandsecretagentsand JonathanWalker’sgraphicaccountofoneofhermostinfamousspymastersare amongstthefewscholarlyoutputsonVenice’sintelligenceandespionagepursuits.⁹ Comprisingaremarkableabundanceofarchivalevidenceandanecdotal nuance,Preto’sworkiscomposedofasystematiclistofcasestudiespresentedin basicthematiccategories.Producedinthisformat,athoroughanalysisand evaluationofRenaissanceVenice’sintelligenceorganizationanditsroleinthe Republic’spolitics,economy,andsocietyseemtobebeyondthescopeofPreto’ s work.Walker ’sstudyprovidesacreativeaccountofoneofVenice’smostinfamousspymasters,GerolamoVano.Inaspiritednarrativethatearnedthebookthe characterizationof ‘the firsttrueworkof “punkhistory”’,¹⁰ theauthortakesthe readeronanenthrallingjourneythroughVenice’salleywaysandcircuitous calli, relatingVano ’sgarishfeatsandpeccadilloes.Yet,whilethebookuncoversthe surreptitiousunderworldofespionageinseventeenth-centuryVenice,larger

⁷ IoannaIordanou, ‘TheSpyChiefsofRenaissanceVenice:IntelligenceLeadershipintheEarly ModernWorld’,inMaddrelletal., SpyChiefsVolumeII,pp.43–66;SeealsoIordanou, ‘WhatNewson theRialto?TheTradeofInformationandEarlyModernVenice’sCentralizedIntelligenceOrganization’ , IntelligenceandNationalSecurity 31,no3(2016),pp.305–26.

⁸ OntheItalianstatesingeneral,seetheessaysinDanielaFrigo(ed.) PoliticsandDiplomacyin EarlyModernItaly:TheStructureofDiplomaticPractice,1450–1800 (Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress,2000).OnexamplesofEuropeanstates,see,amongstothers,Marshall, Intelligence andEspionage;CarlosJ.CarnicerGarcíaandJavierMarcosRivas, EspíasdeFelipeII:Losservicios secretosdelImperioEspañol (Madrid:Laesferadeloslibros,2005);JacobSoll, TheInformationMaster: JeanBaptisteColbert’sStateIntelligenceSystem (AnnArbor,MI:TheUniversityofMichiganPress, 2009);JohnP.D.Cooper, TheQueen’sAgent:FrancisWalsinghamandtheCourtofElizabethI (London:FaberandFaber,2011).

⁹ PaoloPreto, IservizisegretidiVenezia:SpionaggioecontrospionaggioaitempidellaSerenissima (Milan:IlSaggiatore,1994);JonathanWalker, Pistols!Treason!Murder!TheRiseandFallofaMaster Spy (Melbourne:MelbourneUniversityPress,2007).

¹

⁰ Walker, Pistols!Treason!Murder!,frontcoverendorsementbyIanMcCalman.

questionspertainingtotherolethatsystematizedintelligenceplayedinthecity’ s internalandexternalsecurityremainunasked.Inshort,whileimpressivein archivaldetailandnarrativerichness,boththeseworksexposespecificintelligence operationsandsecretagentsbutfallshortofabroaderanalysisofVenice’ s intelligenceorganizationanditswiderimpactontheVenetianstate’sinternal andexternalsecurity.Asaresult,RenaissanceVenice’ssecretservicestilllingersin theshadowsofhistoriography.

Thisisnotaccidental,consideringthat,accordingtoconventionalwisdom, systematizedintelligenceandespionageare ‘modern ’ phenomenathatspan largelyfromtheeveoftheGreatWartothepresent.¹¹Thisdoesnotmeanthat historianshavenotmadeworthwhileendeavourstoexplorethelargelyuncharted territoryoftheearlymodernera.¹²Indeed,somesigni ficantscholarlyefforthas beenexpendedonthediplomaticand,byextension,theintelligenceoperationsof earlymodernstateslikeEngland(andlaterBritain),¹³France,¹⁴ theDutchRepublic,¹⁵ theOttomanandHabsburgempires,¹⁶ Portugal,¹⁷ Spain,¹⁸ andseveral prominentItalianstates,¹⁹ eventhoughsomeoftheseworksarepremisedon

¹¹Thebibliographyonthistopicisvast.Foranoverview,seePhilipKnightley, TheSecondOldest Profession:SpiesandSpyingintheTwentiethCentury (London:Deutsch,1987).

¹²Infact,afreshscholarlytrendhasstartedtoexplorethedevelopmentofintelligencefromancient times.Forasweepinghistoricaloverview,seeChristopherAndrew, TheSecretWorld:AHistoryof Intelligence (London:Penguin,2018).

¹³MildredG.Richings, TheStoryoftheSecretServiceoftheEnglishCrown (London:Hutchinson, 1935);PeterFraser, TheIntelligenceoftheSecretariesofStateandtheirMonopolyofLicensedNews (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1956);PaulS.Fritz, ‘TheAnti-JacobiteIntelligenceSystem oftheEnglishMinisters,1715–1745’ , HistoricalJournal 16,no(1973),pp.265–89;RichardDeacon, AHistoryoftheBritishSecretService (London:PantherBooks,1990),esp.pp.16–22;Marshall, IntelligenceandEspionage;PatrickH.Martin, ElizabethanEspionage:PlottersandSpiesintheStruggle betweenCatholicismandtheCrown (Jefferson,NC:McFarlandandCompany);Marshall, ‘“Secret Wheeles”:ClandestineInformation,Espionage,andEuropeanIntelligence’,inJeroenF.J.Duindam, MauritsA.Ebben,andLouisSicking(eds.), BeyondAmbassadors:Missionaries,ConsulsandSpiesin Pre-ModernDiplomacy (Leiden:Brill,forthcoming).

¹

¹

⁴ LucienBély, EspionsetambassadeursautempsdeLouisXIV (Paris:Fayard,1990).

⁵ KarlDeLeeuw, ‘TheBlackChamberintheDutchRepublicduringtheWaroftheSpanish SuccessionanditsAftermath,1707–1715’ , HistoricalJournal 42,no1(1999),pp.133–56.

¹

⁶ EmrahSafaGürkan, ‘Espionageinthe16thCenturyMediterranean:Secrecy,Diplomacy,MediterraneanGo-BetweensandtheOttomanHabsburgRivalry’,UnpublishedPhDthesis(Georgetown University,2012);Gürkan, SultanınCasusları:16.Yüzyılda İstihbarat,SabotajveRüşvetAğları (Istanbul:KronikKitap,2017).

¹⁷ FernandoCortésCortés, EspionagemeContra-EspionagemnumaGuerraPeninsular1640–1668 (Lisbon:LivrosHorizonte,1989).

¹

⁸ CarnicerGarcíaandMarcosRivas,EspíasdeFelipeII;GeoffreyParker, TheGrandStrategyof Philip II (NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress,1998).ForanoverviewoftheliteratureonSpanish intelligence,seeChristopherStorrs, ‘IntelligenceandtheFormulationofPolicyandStrategyinEarly ModernEurope:TheSpanishMonarchyintheReignofCharlesII(1665–1700)’ , Intelligenceand NationalSecurity 21,no4(2006),pp.493–519.

¹⁹ OnVenice,seePreto, Iservizisegreti;Iordanou, ‘WhatNewsontheRialto?’.OnVeniceand Genoa,seeRomanoCanosa, Alleoriginidellepoliziepolitiche:GliInquisitoridiStatoaVeneziaea Genova (Milan:Sugarco,1989).OnSavoy,seeChristopherStorrs, War,DiplomacyandtheRiseof Savoy,1690–1720 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1999).OnMilan,seeFrancescoSenatore, ‘Unomundodecarta’:formeestrutturedelladiplomaziasforzesca (Naples:Liguori,1998).Onthe Italianstatesingeneral,seetherelevantessaysinFrigo, PoliticsandDiplomacy

theregurgitationofoldmythsratherthantherealitybehindthem.²⁰ Nevertheless, limitedefforthasbeeninvestedinexpoundinghowsystematizedintelligence influencedanearlymodernstate’ssecurityand,byextension,politicaldecisionmaking,economicvigour,andevensocialconduct.Thisisastonishing,as, contrarytothemethodologicalimpedimentstotheaccessofcontemporary sources,²¹archivalrecordsoftheearlymodernperiodcanyieldawealthof evidenceabout ‘thedarkunderbelly ’ ofearlymodernpolitics.²²

Aimingtorectifythisissue,thisbookattemptsthreefeats.Firstly,challenging thewidelyacceptedviewthatsystematizedintelligenceandstate-organizedsecurityarecharacteristicofthemodernstate,developedtoservemilitary-political purposes,²³thebookarguesthatorganizedintelligencealreadyexistedintheearly modernera,and,inthecaseofacommercialpowerlikeVenice,italsoundergirdedeconomic-commercialinterests.Undeniably,earlymodernintelligencewas notastechnologicallyastuteasinthetwentiethcentury.Throughasystematic analysisofthefunctionandinstrumentalityofRenaissanceVenice’sintelligence pursuits,however,thebookrevealstheindisputableimpactofcentrallyorganized intelligenceonanearlymodernstate’spolitical,economic,andsocialsecurityand prosperity.Forthisreason, Venice’sSecretService movesbeyondsimplisticnarrativeaccountsofsecretagentsandoperations,castingthefocus,notonthe revelatoryvalueofclandestinecommunicationandmissionsbutonthesocial processesthatgeneratedthem.Inconsequence,Venice’scentralintelligence apparatusisexploredandanalysedasanorganization,ratherthanasthecapriciousintelligenceenterpriseofagroupofstatedignitaries.

Secondly,thebookpostulatesthecoreclaimthatRenaissanceVenicewasone oftheearliestearlymodernstatestohavecreatedacentrallyorganizedstate intelligenceorganization.Thiscomprisedspecialistexpertiseonasinglesite the imposingDoge’sPalaceoverlookingtheVenetianlagoon andunderthedirectionofspecificgovernmentalcommittees,primarilytheCouncilofTen,who oversawandadministeredinterwovenwaysofworkingwithinandbeyondthe palace ’swalls.JustliketheVenetiandiplomaticcorpus,Venice’sintelligence organizationwasa ‘branchofthecivilservice’,adistinctannexofabroadand structuredbureaucraticapparatusthatformedpartofaratheringloriousareaof

²⁰ See,forexample,Deacon, AHistoryoftheBritishSecretService

²¹Foradetaileddiscussiononthedifficultiesimposedbyarchivalsources,oreventheclaimthat secretactivitieswereallegedlyexcludedfromhistoricalrecords,seetheessaysinChristopherAndrew andDavidDilks(eds.), TheMissingDimension:GovernmentsandIntelligenceCommunitiesinthe TwentiethCentury (Champaign,IL:UniversityofIllinoisPress,1984).

²²Marshall, IntelligenceandEspionage,p.2.

²³See,amongstothers,BernardPorter, PlotsandParanoia:AHistoryofPoliticalEspionagein Britain, 1790–1988 (London:UnwinHyman,1989);HenryA.Kissinger, Diplomacy (NewYork:Simon& Schuster,1994);RichardC.Thurlow, TheSecretState:BritishInternalSecurityintheTwentiethCentury (London:Wiley,1994);WilliamO.WalkerIII, NationalSecurityandCoreValuesinAmericanHistory (NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress,2009).

governmentwithinthepanoramaofinternationaldiplomacy.²⁴ Toexaminehow thisorganizationwasstructured,thebookdescribesandanalysesthevarious departmentsthatcomprisedit,aswellasthecompositesystemofmanagerial delegationthatwasdevelopedtomanageitsfar-reachinggripacrossEurope,the NearEast,andevenNorthernAfrica.Particularemphasisisplacedonthetwo distincttypesofworkforceengagedbythisorganization:theformallyappointed diplomatsandstateservantsandthecasuallyand moreoftenthannot selfappointedrecruits.

Thirdly,thebookexploresthedevelopmentofsystematicintelligencenotonly throughapoliticallensbutalsothroughasocio-economicone.Mostintelligence studiestodateareconductedwithanoverwhelmingemphasisonmilitary, political,anddiplomatichistoryandinternationalrelations. Venice’sSecretService particularlyfocusesontheVenetianRepublic’scommercialandbusinessacumen andexploresthehypothesisthatthiswasoneofthemaindriversbehindits systematicorganizationofdiplomacy,bureaucracy,and,ultimately,intelligence. Forthispurpose,thebooknotonlyrevealsandanalysesVenice’sclandestine missionstoprotectcitiesofprimeeconomicsignificanceagainstthepredatory proclivitiesofenemies(especiallytheOttomans),butshowcasesseveralinstances ofVenetianmerchantsstationedinortraversingtheMediterraneanwhoundergirdedVenice’sintelligenceoperationsinordertoprotecttheRepublic’sand,by extension,theirowneconomicinterests.For,asHansKisslingaptlynoted, ‘inthe eyesofthemercantilestate,itwasobviousthatVenetiansubjectsfelttheneedto serveitatalltimes,especiallywhileabroad’.²⁵ Moreover,thebookshowshowthe CouncilofTencommodifiedintelligenceandstatesecurityoperations.Itdidsoby incentivizingordinaryVenetians,whowerecategoricallyexcludedfrompolitical participation,topartakeinpoliticizedactsofstatesurveillanceandespionageasa symbolofdutifulcontributiontotheVenetiansociety.Throughthislens,early modernintelligenceemergesasbotharigidtop-downandavariablebottom-up practice.

Thebook’sultimatepurposeistoexaminethetime-specificmeaningand functionsofintelligenceinasocietyandforastatethataredecisivelydifferent fromthoseinwhichmodernintelligenceoperates.Forthisreason,intelligenceis examinedasa flexibleactivitymadeupofaconglomerationofsocialprocesses thatdeterminedwhatwassharedwithwhom,whowasexcluded,andhowthe secretcommunicationofknowledgewascontrolledandregulated.Consequently, thebookfocusesontheparadoxicalnatureofsecretcommunicationthat,onthe

²⁴ AndreaZannini, ‘EconomicandSocialAspectsoftheCrisisofVenetianDiplomacyinthe SeventeenthandEighteenthCenturies’,inFrigo, PoliticsandDiplomacy,pp.109–46(herep.110).

²⁵ HansJ.Kissling, ‘VeneziacomecentrodiinformazionisuiTurchi’,inHansG.Beck,Manoussos Manoussakas,andAgostinoPertusi(eds.), VeneziacentrodimediazionetraOrienteeOccidente(Secoli XV–XVI).Aspettieproblemi (Florence:LeoS.Olschki,1977),pp.97–109(herep.99).

onehand,erectsbarriersbetweenthose intheknow andthose inthedark²⁶ and, ontheother,demolishesbarriersthatwouldotherwisehavetoexistifknowledge transferwasnotconcealedandprotectedthroughsecrecy.Fromthisperspective, secrecy,astheongoingpracticeofintentionalconcealment,isexploredasan enablingknowledge-transferprocesscontingentuponsocialinteractionsthat formedidentities,alliances,anddivisions.

Stemmingfromtheabove, Venice’sSecretService servesseveralpurposes. Speci fically,itis:

• abookaboutearlymodernintelligence:Asitwillbemadeclearinthe followingpages,theearlymodernperiodplayedadecisiveroleinthe evolutionoforganizedintelligence.Lackingthetechnologicaladvancesof thetwentiethcentury,RenaissanceVenicewasemblematicinthecreationof arobust,centrallyorganizedstateintelligenceapparatusthatplayedapivotal roleinthedefenceoftheVenetianempire.Officialinformantsandamateur spieswereshippedacrossEurope,Anatolia,andNorthernAfrica,conducting Venice’smanifoldintelligenceoperations.Whilerevealingaplethoraof secrets,theirkeepers,andtheirseekers,thebookwillexplorethesocialand managerialprocessesthatenabledtheirexistenceandfurnishedthefoundationforthecreationofoneoftheworld’searliestcentrallyorganizedstate intelligenceservices.

• abookaboutpre-industrialorganizationandmanagerialpractices:Employingatransdisciplinaryperspective,thebookwillshowthatorganizational entitiesandmanagerialpracticesexistedlongbeforecontemporaryterminologywascoinedtodescribethem.Combiningthenarrativeconstructionof theoreticalconceptsfromthedisciplinesofsociology,management,and organizationstudieswitharchivalrecordsandsecondaryhistoricalsources, RenaissanceVenice’ssecretserviceisanalysedasaproto-modernorganizationwithdistinctmanagerialstructuresthatenabledthecoordinationof uniformpatternsofworkingacrosslongdistances.Aswillbecomeapparent inthefollowingchapters,theVenetianintelligenceorganization,madeupof geographicallydispersedstaterepresentativesandstateofficials,menofthe militaryandthenavy,in-houseandexpatriatewhite-collarstatefunctionaries,aswellascasuallysalariedspiesandinformers,allheadedbytheCouncil ofTen,was,ultimately,asocialstructureheldtogetherthroughcommonly acceptedrulesandregulations thepurestformoforganizationaccordingto MaxWeber,² ⁷ the ‘fatheroforganizationscience’ andoneofthefoundational

²⁶ Onanauthoritativesociologicaltheorizationofsecrecy,seeGeorgSimmel, ‘TheSociologyof SecrecyandSecretSocieties’ , AmericanJournalofSociology 11,no4(1906),pp.441–98,transl.Albion Small.

²⁷ MaxWeber, EconomyandSociety:OutlineofInterpretiveSociology,Vol.1,ed.GuentherRothand ClausWittich(Berkeley,CA:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,1978),p.51.

thinkersinmanagementstudies.²⁸ Morespecifically,thecommonlyaccepted patternsofworkingwithinthisorganizationwerebasedontraditional authority theCouncilofTen andtheallocationofhumanresources throughlegal-traditionaladministration astringofformaldecreesthat authorizedtheTen’spowerofcommand.Consequently,throughthelens ofearlytheoriesoforganizationandmanagement,Venice’ssecretservice emergesasaprimordialintelligenceorganizationwhosegovernancestructuredoesnotdivergegreatlyfromcontemporaryorganizationalentities.

• abookabouttheVenetianempireinthesixteenthcentury:Muchasthefocal pointofthebookisthecentralorganizationofRenaissanceVenice’ssecret service,anendeavourismadetoabstainfromfocusingdisproportionatelyon aninward-lookingrepresentationofthe Dominante,whichhasperpetuated thepredominanthistoriographicalinterpretationofVeniceas ‘agreatcity’ , an ‘enduringrepublic’ , ‘anexpansiveempire’,and ‘animposingregional state’.²⁹ Instead,asystematicattemptismadetoredressthebalancein VenetianhistoriographybyexploringtheTen’soperationsbothwithinthe cityand,importantly,inthegeographicallydispersedterritoriesofthe Terraferma Venice’spossessionsontheItalianmainland andthe Stato daMar theVenetianoverseasempire.Onthewhole,asVenice ’ssystematizedintelligencepursuitscrossedborders,traversingtheEuropeancontinentandtheLevantandeventheshoresofNorthernAfrica,thebookwill endeavourtopresentaquasi-globalhistoryofVenice ’ssecretservice.

• abookabouttheVenetianCouncilofTen:Asweshallseeinthefollowing section,theCouncilofTenwasanauthoritativecommitteeresponsiblefor thesecurityoftheVenetianstate.Asoneofthemostpowerfulinstrumentsof governmentinRenaissanceVenice,theTenhavebeentheobjectofsubstantialstudywithinthewidercontextofVenice’spoliticalhistory.³⁰ Thisbook broadensanddeepensthehistoricalunderstandingoftheCouncilofTenby revealingandanalysingtheirconcertedeffortstoclay-modelandspearhead Venice’ssecretserviceastheRepublic’sspychiefs.Castingasidenormative representationsoftheTenasafear-inducinggovernmentalcommittee,the

²⁸ StephenCummings,ToddBridgman,JohnHassard,andMichaelRowlinson, ANewHistoryof Management (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2017),p.119.Forawell-roundedreviewofthe significanceofMaxWeber’sworkonorganizationandmanagementstudies,seeStephenCummings andToddBridgman, ‘TheRelevantPast:WhytheHistoryofManagementShouldBeCriticalforour Future’ , AcademyofManagementLearning&Education 10,no1(2011),pp.77–93;Cummings, Bridgman,Hassard,andRowlinson, ANewHistoryofManagement,esp.Chapter4.

²⁹ JohnMartinandDennisRomano, ‘ReconsideringVenice’,inJohnMartinandDennisRomano (eds.), VeniceReconsidered:TheHistoryandCivilizationofanItalianCity-State,1297–1797 (Baltimore, MD:JohnsHopkinsUniversityPress,2002),pp.1–35(herep.1).OnacritiqueofAnglophone historians’ propensitytopaydisproportionateattentiontoVenicecomparedtoitscolonies,seeMartin andRomano, VeniceReconsidered,pp.xi,6,7,27.

³⁰ OntheCouncilofTen,seeMauroMacchi, IstoriadelConsigliodeiDieci (Turin:Fontana,1848); RobertFinlay, PoliticsinRenaissanceVenice (London:ErnstBenn,1980).

bookwillpresentafreshimageofthemasagroupofintelligenceleaders deeplyweddedtothesecurityoftheVenetianstate,itssubjects,anditssecret operatives.³¹

• abookonpeople’shistory:Asitwillbecomeapparentintheensuingchapters, Venetiancitizensandsubjectsofallwalksoflifewereinvitedtocontributeto RenaissanceVenice’sstatesecurityundertakingsbyparticipatinginrisky operations.Avarietyofincentiveswereofferedforsuchendeavours,ofwhich monetarysums,theopportunitytoreducepoliticalsentences,andincome derivingfromstateserviceswerethemostprevalent.Numeroussuch instancesrelatedinthisbookdemonstratethat,intheearlymodernera, systematizedintelligencewasnotanoutcomeofarigidtop-downprocessof authorityandcontrol.Onthecontrary,bottom-upcontributionsoflay individualsaresuggestiveofintelligence ‘frombelow’ thatisfundamental forourunderstandingofearlymodernintelligence.Seeninthisway,the studyofearlymodernintelligenceisasmuchapeople’shistory,asitisa historyofelites.

Onthewhole, Venice’sSecretService investigatesandevaluatesthefunctionof Venice’sstateintelligenceapparatusfromapolitical,socio-economic,andorganizationalperspective.Accordingly,itisabookofpolitical,economic,andsocial historyasmuchasitisabookofintelligenceandorganizationalhistory.Ultimately,thebookoffersafreshvistaonsystematizedintelligenceinthelong Renaissance,addingtheconceptof ‘organization’ tothestudyofearlymodern politics,economy,andsociety.AtthetopofthisorganizationsattheCouncilof Tenandtheirsubsidiary,theInquisitorsoftheState.

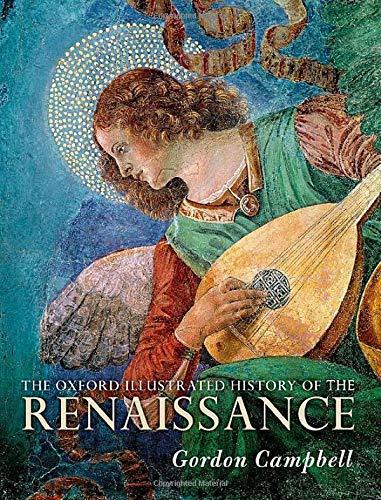

TheCouncilofTenandtheInquisitorsoftheState

Venice’scentralintelligenceorganizationwasengineeredbytheCouncilofTen (ConsigliodeiDieci:seeFig.0.1).Establishedin1310,intheaftermathofBaiamonteTiepolo’sfailedattempttooverthrowthereigningDoge,PieroGradenigo, theCouncilofTenwastheexclusivecommitteeresponsibleforthesecurityofthe Venetianempire.Thecouncilwasactuallymadeupofseventeenmen,including tenordinarymemberswhoservedannualterms,theDoge’ssixducalcounsellors,

³¹ForananalysisoftheCouncilofTen’sleadershipendeavoursastheheadsofVenice’sintelligence andstatesecurityoperations,seeIordanou, ‘TheSpyChiefsofRenaissanceVenice’.Forageneral overviewofthefunctionofleadershipinIntelligence,seePaulMaddrell, ‘WhatisIntelligence Leadership?ThreeHistoricalTrends’,inMaddrelletal., SpyChiefsVolume II,pp.5–42;Christopher Moran,IoannaIordanou,andMarkStout, ‘Introduction:SpyChiefs:Power,SecrecyandLeadership’ , inChristopherMoran,MarkStout,IoannaIordanou,andPaulMaddrell(eds.), SpyChiefsVolumeI: IntelligenceLeadersintheUnitedStatesandtheUnitedKingdom (WashingtonDC:Georgetown UniversityPress,2018),pp.1–20.

Fig.0.1. LaSaladelConsigliodeiDieci,GabrieleBella.Reproducedwithpermissionof theFondazioneQueriniStampaliaOnlus,Venice.

whodidnothavevotingrights,andtheDogeastheceremonial figurehead.³² EverymonththreeordinarymemberstookturnsatheadingtheTen’soperations. Theywerecalled Capi,theHeadsoftheTen.³³Initially,theTenweretaskedwith protectingthegovernmentfromoverthroworcorruption.Progressively,however, theirpoliticalandjudicialpowersextendedtosuchadegreethat,bythemidfifteenthcentury,theyencompasseddiplomaticandmilitaryoperations,control oversecretaffairs,publicorder,domesticandforeignpolicy.³⁴ Bythe firstdecade ofthesixteenthcentury,thepoweroftheCouncilofTenhadincreasedtosucha degreethatthecommitteeassumedthedimensionsofa ‘crypto-oligarchy’.³⁵ Crucially,muchoftheTen’ssupremacywaspremisedontheirorganizationand systematiccontroloftheVenetianintelligenceapparatusthatoperatedwithinthe city,across,andbeyondtheVenetiandominion.

³²GaetanoCozzi, ‘AuthorityandtheLaw’,inJohnR.Hale(ed.), RenaissanceVenice (London:Faber& Faber,1973),pp.293–345(herep.308).

³³Macchi, IstoriadelConsigliodeiDieci

³⁴ GaetanoCozzi, ‘LadifesadegliimputatineiprocessicelebraticolritodelConsigliodeiDieci’,in LuigiBerlinguerandFlorianaColao(eds.) Crimine,giustiziaesocietàvenetainetàmoderna (Milan: Giuffrè,1989),pp.1–87;BerlinguerandColao, ‘Venezianelloscenarioeuropeo’,inGaetanoCozzi, MichaelKnapton,andGiovanniScarabello(eds.), LaRepubblicadiVenezianell’etàmoderna.Dal1517 alla finedellaRepubblica (Turin:UnioneTipografico-EditriceTorinese,1992),pp.3–200.

³⁵ AlfredoViggiano, ‘PoliticsandConstitution’,inEricR.Dursteler(ed.), ACompaniontoVenetian History,1400–1797 (LeidenandBoston,MA:Brill,2013),pp.47–84(herep.56).Ontheincreaseofthe CouncilofTen’sresponsibilitiesandjurisdictionfollowingVenice’sterritorialexpansion,seeMichael Knapton, ‘IlConsigliodeiXnelgovernodellaTerraferma:Un’ipotesiinterpretativaperilsecondo Quattrocento’,inAmelioTagliaferri(ed.), AttidelConvegnoVeneziaelaTerrafermaattraversole relazionideiRettori (Milan:Giuffrè,1981),pp.235–60.

Intrepidandimperious,fromearlyontheTendisplayedanindomitablepolitical appetiteforsystematizingVenice ’ sintelligenceoperations,whichmaterializedin adistinctandrelativelycontinuousfundingline,and,importantly,inanef ficient administrativesystemthatenabledtheVenetianstate’scentralintelligence organization.Suchweightyresponsibilities,sopivotaltothecity ’ sgovernance, meritedaprominentpositioninthecity ’ stopography.TheTen,therefore,were housedinoneofthemostimpressivestateintelligenceheadquartersoftheearly modern(and,admittedly,eventhemodern)world,the PalazzoDucale,overlookingtheVenetianlagooninSaintMark ’sSquare.ThereintheTenorganized andadministeredoneoftheworld’ searliestcentrallyorganizedstateintelligence services.Asweshallsee,thisresembledakindofproto-modernpublicsector organizationthatoperatedwithremarkablecomplexityandmaturity.This servicewasalsosupportedbyseveralotherstateinstitutions,includingthe Senate(theVenetiangovernment’ sdebatingcommitteeandprimarylegislative organ,especiallyupuntilthemid-sixteenthcentury),the Collegio (theSenate’ s steeringcommittee),andtheofficeofstateattorneys( AvogariadiComun ),as wellasthelocalauthoritiesoftheVenetianterritoriesinItaly,theAdriatic,and theMediterranean.³ ⁶

AnattempttorestrainttheTen’sprominentroleinthegovernmentofthe Venetianstatetookplacein1582,whenareform(correzione )imposedbythe MaggiorConsiglio (GreatCouncil) theassemblyoftheentirebodyofmale Venetianpatricians³⁷—attemptedtoreducetheirpowerandmakethemmore accountabletothe Collegio .³⁸ TheautocraticwayinwhichtheTenwieldedtheir powertarnishedtheirreputationandenvelopedtheminanauraoffear-inducing authority,attimeseventyrannicalsuperciliousness.³⁹ Theirinfamouseruptions werecommittedtoinkbyseveralcontemporaneouschroniclers,suchastheinveteratediaristMarinoSanudo(1466–1536).⁴⁰‘ThisCouncilimposesbanishmentand

³⁶ OnasynthesisoftheinnerworkingsoftheVenetianpoliticalsystem,especiallyinthesixteenth century,seeViggiano, ‘PoliticsandConstitution’

³⁷ Onthe MaggiorConsiglio,especiallytherequirementsforadmissionanditsprerogatives,see GiuseppeMaranini, LacostituzionediVeneziadopolaserratadelMaggiorConsiglio (Venice:LaNuova ItaliaEditrice,1931),esp.pp.41–6and78–102.

³⁸ Ondifferinginterpretationsofthe correzione oftheCouncilofTen,seeAldoStella, ‘La regolazionedellepubblicheentrateelacrisipoliticavenezianadel1582’,in Miscellaneainonoredi RobertoCessi,Vol.II(Rome:EdizionidiStoriaeLetteratura,1958),pp.157–71;GaetanoCozzi, Ildoge NicolòContarini.Ricerchesulpatriziatovenezianoagliinizidelseicento (VeniceandRome:Istitutoper lacollaborazioneculturale,1958),pp.2–51;MartinLowry, ‘TheReformoftheCouncilofTenin 1582–3:AnUnsettledProblem?’ , StudiVeneziani 13(1971),pp.275–310;GiacomoFassina, ‘Factiousness,FractiousnessorUnity?TheReformoftheCouncilofTenin1582–1583’ , Studi veneziani,n.s.54(2007),pp.89–118.

³⁹ FocusingonVenice’ s ‘anti-myth’,nineteenth-centuryhistoriography,influencedbyPierreDaru’ s HistoiredelaRépubliquedeVenise,presentedVeniceasahotbedofmoralcorruptionandunrestrained aristocraticsupremacyoverseenbytheubiquitousCouncilofTen.Foranuanceddiscussionofthe ‘anti-myth’ andnineteenth-centuryhistoriographyonVenice,seeClaudioPovolo, ‘TheCreationof VenetianHistoriography’,inMartinandRomano, VeniceReconsidered,pp.491–519.

⁴⁰ OnVenetiandiaristsandtheiruseofcorrespondence,seeChristianeNeerfeld, ‘Historiaperforma didiaria’.LachronachisticavenezianacontemporaneaacavallotrailQuattroeilCinquecento (Venice: IstitutoVenetodiScienzie,LettereedArti,2006);MarioInfelise, ‘From Merchants’ Lettersto

exileuponnobles,andhasothersburntorhangediftheydeserveit,andhas authoritytodismissthePrince,eventodootherthingstohimifhesodeserves’ , heoncewroteinhisaccountofVenice’squotidianexistence.⁴¹TheTen’sunbending authoritystemmedfromrespectfortwofundamentalVenetianvirtues:order thatwasachievedbysecrecyandmaturitythatwasguaranteedbygerontocracy. Boththesevirtuesweredeemedparamountforstatesecurity. ⁴²Itisnota coincidence,therefore,thattheTen’sstringentregulationsdidnotexcludethe Council’sownmembers.Asthegoverningbodyresponsibleforstatesecurity, failuretoactspeedilyonissuesthatimperilleditcouldrenderthemliabletoa 1,000-ducat fi ne, ⁴³aheftysum,consideringthataVenetianpatricianservingas anambassadorinthesixteenthcenturyearned2,400to7,200ducatsannually. ⁴⁴

Inaway,theTenseemedtoespouseMachiavelli’smaximthataruler ‘must notworryifheincursreproachforhiscruelty,solongashekeepshissubjects unitedandloyal.Bymakinganexampleortwo,hewillprovemorecompassionatethanthosewho,beingtoocompassionate,allowdisorderswhichleadto murderandrapine’ . ⁴⁵ Nevertheless,whatemergesfromtheTen’ssecretregisters istheimageofanunabashed,yetdigni fiedcommitteethat,attimes,wentto greatlengthstoensurethesafetyandwelfareofthoseintheiremployandthose directlyaffectedbytheirpolicies.Suchactionsincludedorderingtheprotection ofanimperilledVenetiancourier,⁴⁶ providing financialsupporttothefamilyofa deceasedcovertoperativewhofellinserviceoftheRepublic,⁴⁷ andreleasing erroneouslyarresteddetaineesandrestoringtheirconfiscatedpossessions.⁴⁸ In otherwords,thestudyofthecovertandclandestineoperationsoftheCouncilof Tenrevealsthat,whileimperiousandauthoritative,ithadapropensitytoactina justandevenbenevolentmanner ‘forthedignityofourSignoryandthe preservationofpublictrust’ . ⁴⁹

DespitetheCouncilofTen’sgraduallyassumingconsiderablepowerofthe Venetiangovernmentinthesixteenthcentury,itsautocraticproclivitieswerenot leftuncontrolled.TheextraordinarymaturityoftheVenetianpoliticalsystem

HandwrittenPoliticalAvvisi:NotesontheOriginsofPublicInformation’,inFranciscoBethencourt andFlorikeEgmond(eds.), CorrespondenceandCulturalExchangeinEurope,1400–1700,Vol.3of CulturalExchangeinEarlyModernEurope,ed.RobertMuchembledandWilliamMonter(Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,2007),pp.33–52.

⁴¹DavidChambersandBrianPullan(eds.), Venice:ADocumentaryHistory (London:Blackwell, 1992),p.55.

⁴²Finlay, Politics,p.189.

⁴³SamueleRomanin, StoriadocumentatadiVenezia,Vol.VI(Venice:PietroNaratovich,1857), p.530.

⁴⁴ Zannini, ‘EconomicandSocialAspects’,p.127.

⁴⁵ NiccolòMachiavelli, ThePrince,transl.GeorgeBull(London:Penguin,1999),p.53.

⁴⁶ ASV,CX, DeliberazioniSecrete,Reg.14,c.60v.(21March1601).

⁴⁷ Ibid.,Reg.9,c.198v.(15Dec.1571). ⁴⁸ Ibid.,Reg.7,c.9r.(2Oct.1559).

⁴⁹ Ibid.,Reg.9,c.198v.(15Dec.1571).

endeavouredtocontainanypotentialautocracy,atleastinprinciple.Theinstitution ofthe zonta (theVenetianlinguisticvariationof aggiunta or addizione,meaning ‘addition’)wasthemechanismputinplaceforthispurpose.The zonta wasan adjunctcommissionofinitiallytwentymen reducedto fi fteenafter1529,even thoughthisnumbervarieddependingonthecircumstances ⁵⁰—whoparticipated inallimportantassembliesoftheCouncilofTen. ⁵¹Eitherelectedorco-opted, theyplayedtheroleofanimpartialrefereewhosedutywastorecognizeand combatoccurrencesofnepotismandcronyism.Itwasusuallymadeupof patricianswhohadnotsecuredelectiontotheothergoverningbodies.The zonta,therefore,wasa ‘constitutionalshortcut ’ forthosenoblemenwhowished toactivelyparticipateintheVenetianoligarchybuthadnotachievedthenecessarybacking.⁵²

Bythebeginningofthesixteenthcentury,severalpivotalstateaffairs,suchas continuouswarswiththeOttomansandthespectreofthenewPortuguesespice route,renderedtheprotectionofstatesecretsamatterofurgency.Asaresult,in 1539,theCouncilofTen withtheblessingoftheSenateandtheGreatCouncil decidedtoestablishacounter-intelligencemagistracy.⁵³Thistookshapeinthe institutionoftheInquisitorsoftheState(InquisitoridiStato),adistinctcommitteethatshouldnotbeconfusedwiththe SantoUfficio,theVenetianInquisition.⁵⁴ Initiallyentitled ‘InquisitorsagainsttheDisclosuresofSecrets’,the Inquisitori wereaspecialtribunalmadeupofthreemen,twofromtheranksoftheTenand oneoftheDoge’sducalcounsellors.⁵⁵ Theyheldanannualtenure,uponcompletionofwhichtheycouldseekre-election.⁵⁶ Theirrolestemmedfromamedieval judicialtraditionthatenabledboththeChurchandtheStatetoinitiatesecret investigationsandtrials exofficio, ‘makingguilteasiertoproveandevidenceless opentodiscussion’ . ⁵⁷ Whilethe Inquisitori wereprimarilyresponsiblefor counter-intelligenceandtheprotectionofstatesecrets,graduallytheiractivity encompassedallaspectsofstatesecurity,includingconspiracies,betrayals,public

⁵⁰ Ibid.,Reg.2,c.5r./v.(18May1527). ⁵¹Canosa, Alleorigini,p.23.

⁵²Finlay, Politics,pp.185–90.

⁵³Followingthetraditionchartedbyeminenthistoriansofearlymodernintelligence,Ihavetaken thelibertyofusingmodernterms,suchas ‘counter-intelligence’ , ‘secretservice’,and ‘intelligence organization’.See,Bély, Espions;CortésCortés, EspionagemeContra-Espionagem;Preto, Iservizi segreti;CarnicerGarcíaandMarcosRivas,EspíasdeFelipeII;Gürkan, ‘Espionageinthe16thCentury Mediterranean’;Gürkan, ‘TheEfficacyofOttomanCounter-Intelligenceinthe16thCentury’ , Acta OrientaliaAcademiaeScientiarumHungaricae 65,no1(2012),pp.1–38.

⁵⁴ OntheInquisitorsoftheState,seeSamueleRomanin, GliInquisitoridiStatodiVenezia (Venice: PietroNaratovich,1858);Canosa, Alleorigini,esp.pp.19–85;Preto, Iservizisegreti,pp.55–74;and SimoneLonardi, ‘L’animadeigoverni.Politica,spionaggioesegretodistatoaVenezianelsecondo Seicento(1645–1699)’,UnpublishedPhDThesis(UniversityofPadua,2015).Ontherelevantfounding decrees,seeRomanin, Storiadocumentata,Vol.VI,pp.122–4.

⁵⁵ Romanin, GliInquisitoridiStato,p.16;Romanin, Storiadocumentata,Vol.VI,pp.78–80 (Deliberationof20Sep.1539).

⁵⁶ Romanin, Storiadocumentata,Vol.VI,p.78.

⁵⁷ FilippoDeVivo, InformationandCommunicationinVenice:RethinkingEarlyModernPolitics (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2009),p.34.

order,andespionage.⁵⁸ Allthesewereexpectedtobeconcealedunderathick mantleofsecrecybut,unquestionably,oughttobecommunicatedtotheTen.

BeyonditsorganizationandmanagementofVenice’sintelligenceinfrastructure, itisalsoworthpointingoutthattheCouncilofTenwasmorebroadlyresponsible formilitarypreparednessanddefence,bothwithinandbeyondthecityofSaint Mark.⁵⁹ Thisinvolvedbuilding,reinforcing,andoccasionallyrepairingthedominion’scitywallsandfortificationsinordertorenderVeniceanditspossessions impregnabletoassault.Forexample,in1583,followingintelligenceofanimminent Ottomanattack,theTenorderedtheconstructionofawallaroundtheVenetian townofNovigrad,pluscavalryreinforcements,forthe ‘maximumsecurityofthe inhabitants’ . ⁶⁰ TheywerealsoanxioustoensurethatthegatesofVenetianstrongholds,especiallyinthe Terraferma,wereconstantlyguarded,sothatthelocal authoritiescouldmonitorthoseenteringandexitingtheurbanterrain.⁶¹

Aparticularsecurityconcernwasthe Arsenale,theproductionsiteforthe renownedVenetiangalleysthatcontributedtotheRepublic’scommercialand militarymight.⁶²AsthenucleusofVenetiannavigation,the Arsenale wasof geostrategicsignificancetoVenice.Forthisreason,theTentookitsmaintenance incrediblyseriously.When,intherunuptothethirdOttoman-VenetianWar, forinstance,itcametotheirattentionthatVenetianmerchantsweretrading hemp avitalrawmaterialforshipbuildingandnavigation,whoseproduction withintheVenetiandominionwasdwindling⁶³ theyurgentlyorderedtheir navalchiefstobringbacktothe Arsenale anyhempdiscoveredoncommercial galleystraversingtheAdriatic,evencompensatingthemerchantsfortheirloss.⁶⁴ Periodicinspectionsofthestateshipyards,delegatedtothe Provveditoriall’Arsenale,werealsopartofthemeasuresemployedbytheTentomaintainthesecurity oftheVenetianstate. ⁶⁵ Alas,thelargenumberofmeasurestheyintroduceddid

⁵⁸ SeeLonardi, ‘L’animadeigoverni’

⁵⁹ OnthemilitarypreparationsoftheVenetiansfortheWarofCyprus,seeMichaelMallettand JohnR.Hale, TheMilitaryOrganizationofaRenaissanceState:Venice c.1400to1617 (Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1983),pp.233–41.

⁶⁰ ASV,CCX, LetteredeiRettoriediAltreCariche,b.284(2Feb.1583).

⁶¹Oncitygatesassitesofurbanpower,exclusionandinclusion,seeDanielJütte, TheStraightGate: ThresholdsandPowerinWesternHistory (NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress,2015),esp. Chapter5.

⁶²ThebibliographyontheVenetianArsenalissubstantial.SomenotableworksincludeMarioNani Mocenigo, L’ArsenalediVenezia (Rome:ArtiGraficheUgoPinnarò,1927);FredericC.Lane, Venetian ShipsandShipbuildersoftheRenaissance (Baltimore,MD:JohnsHopkinsUniversityPress,1934); RobertC.Davis, ShipbuildersoftheVenetianArsenal:WorkersandWorkplaceinthePreindustrialCity (Baltimore,MD:JohnsHopkinsUniversityPress,1991);IoannaIordanou, ‘MaritimeCommunitiesin LateRenaissanceVenice:TheArsenalottiandtheGreeks’,UnpublishedPhDThesis(TheUniversityof Warwick,2008),esp.Chapter2.

⁶³OnthesignificanceofhempfortheVenetianRepublic,seeFredericC.Lane, ‘TheRopeFactory andHempTradeofVeniceintheFifteenthandSixteenthCenturies’ , JournalofEconomicsandBusiness History IV,supplement(1932),pp.830–47;RuggieroRomano, ‘EconomicAspectsoftheConstruction ofWarshipsinVeniceintheSixteenthCentury’,inBrianPullan(ed.), CrisisandChangeintheVenetian EconomyintheSixteenthandSeventeenthCenturies (London:MethuenandCo.,1968),pp.59–87.

⁶⁴ ASV,CX, DeliberazioniSecrete,Reg.4,cc.32v.–33r.(14July1534).

⁶⁵ Ibid.,Reg.6,c.51v.(26Aug.1550).

notpreventadevastating firethatwhippedthroughthe Arsenale andobliterated thestockpileofmunitions,togetherwithseveralgalleysoftheRepublic’ sreserve fleet,onthenightof10September1569.Arsonoraccident,rumoursragedfor daysthattheculpritwaseitherJosephNasi,anadvisertoSultanSelimII,⁶⁶ ora Turkishsaboteur.⁶⁷ Undersimilarlysuspiciouscircumstances,perhapsinretaliation,twoweekslatera fireengulfedtheArsenalinConstantinople,wreckingthe JewishquarteroftheOttomancapital. ⁶⁸

ScholarshiphasexploredtheCouncilofTenasanoligarchicgovernmental committeewithacompositemixtureofexclusivejudicialandpoliticalprerogativesthatintensifiedinthecourseofthesixteenthcentury.⁶⁹ TheTen’ssubsidiary, theInquisitorsoftheState,havereceivedconsiderablylessattentionfromcontemporaryscholars,withtheexceptionofarecentstudyfocusingontheiractivity inthe1600s,primarilyduetothesurvivingdocumentation,whichisscarceforthe sixteenthcenturybutplentifulfortheseventeenth. ⁷⁰ Consideringthatboth committees’ jurisdictiveauthoritieswerecontingentupontheirorganizationand systematiccontroloftheVenetianintelligenceapparatusthatbranchedoutacross Europe,Anatolia,andevenNorthernAfrica,whereVenicehaddiplomaticand commercialrepresentation,ananalysisandevaluationoftheirintelligenceorganizationislongoverdue.Inviewofthemeteoricriseinhistoriographyofcontemporaryintelligenceandespionage,especiallyintheAnglosphere,overthelast thirtyyears,⁷¹suchascholarlyendeavourcouldnotbemoretimely.

WhyVenice?

Inherpioneeringbookentitled PoliticalEconomiesofEmpire ,MariaFusaro postulatedthebold,yetaptpropositionthat ‘itistimetostartconsideringthe Venetianstateinitsentirety terra and mar blendingtogetherdifferenthistoriographicalstrandsandtraditions,aimingataholisticapproachtothetopicof

⁶⁶ Gürkan, ‘Espionageinthe16thCenturyMediterranean’,pp.287,378.

⁶⁷ KennethM.Setton, ThePapacyandtheLevant (1204–1571),VolIV:TheSixteenthCenturyfrom JuliusIIItoPiusV (Philadelphia,PA:TheAmericanPhilosophicalSociety,1976),p.944;seealso BenjaminArbel, TradingNations:JewsandVenetiansintheEarlyModernMediterranean (Leiden: Brill,1999),pp.55–63.OnJosephNasiingeneral,seeCecilRoth, TheHouseofNasi:TheDukeofNaxos (NewYork:GreenwoodPress,1948);OnNasiasaspymasterandinstigatorofthe1570–3OttomanVenetianwar,seeGürkan, ‘Espionageinthe16thCenturyMediterranean’,pp.377–84.

⁶⁸ Ibid.

⁶⁹ Macchi, IstoriadelConsigliodeiDieci;Cozzi, ‘AuthorityandtheLaw’;Cozzi, ‘Lapoliticadel dirittonellarepubblicadiVenezia’,inGaetanoCozzi(ed.), Stato,societàegiudizianellaRepubblica Veneta(sec.XV–XVIII) (Rome:Jouvence,1981),pp.15–151;Cozzi, RepubblicadiVeneziaestati italiani:PoliticaegiustiziadalsecoloXVIalsecoloXVIII (Turin:Einaudi,1982).

⁷⁰ Preto, Iservizisegreti,pp.55–74;Lonardi, ‘L’ animadeigoverni’

⁷¹ForBritain,seeChristopherR.Moran, ‘ThePursuitofIntelligenceHistory:Methods,Sources, andTrajectoriesintheUnitedKingdom’ , StudiesinIntelligence 55,no2(2011),pp.33–55.Forthe USA,seeKaetenMistry, ‘NarratingCovertAction:TheCIA,Historiography,andtheColdWar’,in ChristopherR.MoranandChristopherJ.Murphy(eds.), IntelligenceStudiesinBritainandtheUS: Historiographysince1945 (Edinburgh:EdinburghUniversityPress,2013),pp.111–28.