1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bahar, Matthew R.

Title: Storm of the sea : Indians and empires in the Atlantic’s age of sail / Matthew R. Bahar. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018022490 (print) | LCCN 2018025991 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190874254 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190874261 (Epub) | ISBN 9780190874247 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Abenaki Indians—History. | Ocean and civilization. | Indians—First contact with Europeans.

Classification: LCC E99.A13 (ebook) | LCC E99.A13 B245 2019 (print) | DDC 974.004/9734—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022490

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For my parents

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction: Making, Forgetting, Remembering 1

1 The Indians’ Old Sea, to 1500 17

2 A New Dawn on an Old Sea, 1500–1600 39

3 New Waves, New Prospects: Strategizing the Sea, 1600–1677 67

4 Glorious Revolutions, 1678–1699 99

5 Pieces of Eight, Pieces of Empire, 1700–1713 131

6 The Golden Age of Piracy, 1714–1727 159

7 Imperial Breakdown and the Crisis of Confederacy, 1727–1763 187

Conclusion: What the Bell Tolls 213

Notes 221

Select Bibliography 263 Index 279

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Since I began the journey here, many people have come and gone. Others have been there all along. Each shaped this book in their own way, and I happily ran up many debts because of it.

The time and thought Josh Piker generously provided to this project, from start to finish, proved indispensable to its fruition. I can’t thank him enough for the myriad ways he helped sharpen the book’s prose and argument, and for modeling the very best of our profession. Cathy Kelly has also been there from the beginning, offering inestimable encouragement at every step. In formal and informal settings, I learned early on to value her insights on early America, academic publishing, and life in the academy. Jamie Hart’s expertise in Tudor and Stuart England and steady support of my research interests enriched my exploration of early modern Atlantic history. Gary Anderson, Paul Gilje, Sterling Evans, and Karl Offen were also eager to share their time and thoughts. Fellow grad students at OU, especially Dave Beyreis, Patrick Bottiger, and Matt Pearce, provided reliable sounding boards, entertaining diversions, and lasting friendships.

Several other scholars have given generously to this project with their comments on various parts and iterations. I first presented my ideas to wider audiences at a fellows roundtable at the American Antiquarian Society, organized by Paul Erickson, a brown-bag lunch talk at the Massachusetts Historical Society, organized by Conrad Wright, and at Jace Weaver’s “Exploring the Red Atlantic Conference” at the University of Georgia. At each, I was increasingly heartened to learn from participants that I was on to something. The week-long “Atlantic Geographies” workshop at the University of Miami, organized by Tim Watson, helped me interrogate the explanatory power of an Atlantic framework with junior scholars across the disciplines. Since these initial meetings, the project began to assume its present form thanks to the feedback of Colin Calloway, Kelly Chaves, Jeffers Lennox, Andrew Lipman, Daniel Mandell, Andy Parnaby, Jenny Hale Pulsipher, John G. Reid, Joshua Reid, and Daniel Richter. The

year-long fellows at the Huntington Library in 2014–2015 helped me rethink early chapters of the manuscript and push it toward the finish line. That same year I enjoyed the brief but memorable friendship of Carl Degler, whose enthusiastic encouragement of the project in the final months of his life imparted new inspiration to my own.

The research and writing of this book occurred in many places thanks to the financial support of several institutions. The Huntington Library, through the capable hands of their Director of Research, Steve Hindle, provided a longterm NEH fellowship and a paradisiacal setting to continue writing the manuscript. A Legacy Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, an Andrew W. Mellon Research Fellowship from the Massachusetts Historical Society, and a Phillips Fund for Native American Research award from the American Philosophical Society granted me opportunities to conduct archival research throughout New England. In addition, generous support from the University of Oklahoma’s Department of History in the form of a Hudson Fellowship, an A.K. Christian Scholarship, and a Morgan Family Fellowship offered the time and funding to visit archives abroad.

This book found an ideal home with Oxford University Press. Susan Ferber, editor extraordinaire, expressed thoughtful interest in the project at an early stage and has since shepherded it to completion with her pointed advice, deft editing, and kind encouragement. Because of her guidance, and the critical, thorough, and smart reader reports she solicited, the manuscript reached a fuller potential.

My colleagues at Oberlin College, especially in the Department of History, provided a welcoming and supportive environment to finish the book while beginning a career. I’m grateful for their willingness to mentor newcomers through the learning curve that every professor trained at a research university and employed at a liberal arts college experiences. In their stellar teaching and research records, they set a high bar that I hope to someday reach. My students also deserve credit. Their deep and genuine curiosity about the past, along with their eagerness to join me in thinking through issues that inform this book, are just some of what makes liberal arts teaching so rewarding.

Several friends have provided a welcome escape from the all-consuming tendencies of academic research and writing. Chad Boers has been there since we forged an impossible alliance to win Diplomacy in a high school history class (long live Austro-Turkey). The friendship of Francis and Ang Revak is a special gift that words can never describe. John Paul and Regina Cook, Chris Dalton, Sam and Erin Snow, Adam and Casey Theisen, and Michael Ukpong provided a tight-knit and caring family in Norman. Always edifying were fireside chats with Jon Detwiler, which could meander anywhere from hooded mergansers to survival tactics. Mike Parkin provided good company on many summer afternoons

and sage professional advice whenever I needed it. Fr. Bob Franco’s wise and gentle counsel always seemed to arrive at just the right time.

But the most credit goes to my family. Their unwavering confidence in me has been encouraging, to be sure, but it’s their own commitments and achievements, great and small, that offered the most inspiration. Becky, Jared, Cade, and Mackenzie always received me with open arms (and an open camper) on my trips back to Minnesota. Mike and Liane expressed the least interest in my book but had the heart to ask about it anyway, once or twice. I value their sincerity. Caty and Jeb helped sharpen my storytelling skills by affording me countless opportunities to put Landon and Caleb to bed. Allison fostered the beginning and middle of this project but did not see its end. Her grit, patience, and love demonstrated to me time and again what truly matters. I’m just as grateful to craft a new chapter with Julieann, whose balance of good cheer and honest realism I’ve come to depend on. My parents, Gerry and Sue, deserve praise for all those camping trips too numerous to count, and too remote to locate, where I first developed a curiosity about the past. Thank you most of all for showing me that meaningful accomplishments take time and happen in little ways that are best left unspoken.

Introduction

Making, Forgetting, Remembering

The festive autumn day had chilled when they began their conquest. At first the backdrop seemed quaint and familiar: salty breezes, austere Pilgrims, godly melodies, grateful prayers, lofty vessel. The pageant at Plymouth Harbor, Massachusetts, on Thanksgiving Day 1970 celebrated the 350th anniversary of an iconic moment in American history: the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. But tranquility and reverence suddenly gave way to frenzy and profanity. As park rangers guided sightseers aboard Mayflower II, a throng of twentyfive young men “swept aboard” the life-size replica and wrested control. They stormed the decks, scrambled up the rigging, barked commands from the crow’s nest, struck the ensign of St. George’s Cross, tossed pious mannequins overboard, and declared victory. Some prepared to torch their new prize. One of the leaders held up a musket and warned of an impending revolution. Down below, panicky and confused tourists scurried off the gangplanks, and from the security of shore they looked up and beheld the scene. “We made history,” the intruders announced in the wake of their takeover.1

The momentous commemoration at Plymouth Harbor offered a history lesson no one had heard before. The rowdy revisionists received their schooling in the American Indian Movement (AIM), a new coalition of young Indian activists committed to enhancing indigenous sovereignty, self-determination, and economic opportunity. The audience for their interpretive performance included the crowd of bewildered bystanders as well as those who awoke the following morning to headlines of vandalism and theft. Like the recent occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, which included the participation of several Plymouth protesters, the Thanksgiving rally aimed to shock, irritate, and awaken.2

Much of what made AIM’s publicity stunt so successful was that it subverted deeply held beliefs, not only about that historic instant when the Mayflower dropped anchor but also about early American encounters more generally. There

sit wide-eyed Indians in dimunitive canoes and wooded shorelines dwarfed by ships of strangers who will soon descend to make landfall and begin history. Now it was the Indians moving history. It was the Indians towering at ship’s helm and making waves. What could more forcefully galvanize the cause of decolonization than such a radical assault on colonization’s origin story?

Perhaps what is most surprising about the revelry at Plymouth Harbor is that it was surprising at all. No one there was really making much history. Instead they were all animating a scene from another story, unwittingly but precisely. It was a far older tale whose characters had since vanished, whose details lived on only in scattered shards, whose moral no one was left to remember. It took place in a time as old as the footsteps on Plymouth Rock and a place not far from the shelter of Plymouth Harbor. Its cast and plot bore uncanny resemblances to the spectacle of 1970. That everyone gathered on the stage of Mayflower II believed they were experiencing history in the making rather than history already made—history hijacked as activism rather than history as it really happened—reveals just how fully the story had been forgotten in a dark recess of America’s early past.

Over the course of the early modern period, during North America’s imperial age, several Algonquian peoples across the American northeast confronted an invasion of European colonizers by undertaking an extractive and expansionist political project, a campaign of sea and shore that united their communities, alienated colonial neighbors, and stymied English and French imperialism. Their warriors took to the waves in fleets of ships to make tributaries of strangers and men of themselves. Their peacekeepers took to the trail with promises and demands to articulate policies and ensure compliance. Impelling them all were ambitions for a proper social order in which their people exercised dominion and reaped its rewards, while others showed deference and honored its duties. Their communities responded to the strange, the unstable, and the threatening by reimagining it to conform with the recognizable, the balanced, and the sustaining. In the process they forged something new.

This book is about a maritime power built on the backs of two European empires in the waters of the northwest Atlantic, from the arrival of foreign explorers and fishermen in the sixteenth century until the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Out of many hunter-gatherer peoples they became Wabanaki—the People of the Dawn—the first to experience daybreak over an ocean that had captivated their attention and oriented their world long before strangers from the east appeared on its horizon early in the sixteenth century. By then they were making their homes along the major riverways, coastlines, and offshore islands of present-day Maine, eastern New Brunswick, eastern Quebec, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. These Wabanaki subcultures became known as

Abenaki, Penobscot (Penawapskewi), Maliseet (Wolastoqiyik), Passamaquoddy (Pestomuhkati), and Mi’kmaq.3

In the beginning, Gluskap emerged from the ocean’s recesses to breathe life into his people and into the pelagic universe that would sustain them after his departure. The newcomers who later surfaced in his wake appeared to possess a generative power akin to their great culture hero’s, and as such, Gluskap’s children accorded them a place in their world as profitable but compliant neighbors. But by the mid-seventeenth century, as English colonists expanded into the region and struggled to resist their dependent status, circumscribe Native authority, and subjugate Native interests to their own, Wabanaki first looked to one another and then to the ocean for answers. The long campaign they carried out was a century-long effort to build community among themselves and structure relations with outsiders. The campaign sprung from a common vision of a Dawnland ordered, possessed, and ruled by its first people.4

The people pursued their project of dominion through a blue-water strategy designed to manage and manipulate their growing entanglement with two global empires from the mid-1630s to 1763. Discovering their old waters enriched with new wealth brought from afar and their political affairs drawn into a transatlantic game of imperial fortunes, native leaders, diplomats, and warriors turned east to the ocean and invested in a mutually reinforcing complex of diplomatic and militant policies designed to extend control over the sea and shore of their ancestral inheritance. Naval initiatives targeted distant offshore prospects around Atlantic fisheries as well as opportunities closer to home along northeastern coastlines. Some political negotiations addressed regional ambitions, while others postured toward transoceanic possibilities. Some achieved success, while others fell short. All unleashed changes intended and unplanned. Taken together, the centralization of disparate communities into a confederacy, the integration of foreign tributaries into a newly conceived Wabanakia, the punitive and plundering enterprises of sea fighters, and the transatlantic diplomacy of headmen all exemplified a regionally ascendant power whose project of expansion and extraction in the Northeast rivaled the European empires with which its circumstances would always remain intertwined.5

Native leaders aimed to secure international recognition of their sovereignty by engaging in a discourse of power and prestige with European statesmen they believed to be their equals. Sagamores cultivated a judicious appreciation of the opportunities European politics afforded the mission of Wabanaki ascendancy at home. Incorrigible rivalries and thorny dynastic affairs across the ocean, including England’s Glorious Revolution in 1688 and Jacobite Rebellion of 1715, invested the people separating France and England’s North American empires with new power on an international stage. Headmen and their warriors learned to leverage their interests by exploiting this geopolitical advantage with

impunity, counterbalancing each colonial power’s economic and military need for borderland allies.6

The diplomatic initiatives advanced by sagamores and warriors fortified the other pillar of their dominion: maritime power. It was their commitment to extending and enforcing authority beyond the coast that exposed the precarious limits of English and French influence in territory colonists understood as a frontier separating New England and Acadia. Appropriating both conventional and cutting-edge nautical technology, Wabanaki expanded the Dawnland from its long-standing contours encompassing the coasts, highlands, and lowlands of present-day Maine and eastern Canada to the offshore fishing banks of the northwest Atlantic and greater Gulf of Maine. Colonists who flouted Native authority over local waters risked incurring the predatory retribution of warriors eager to enrich their kin, bring honor to themselves, and enhance their seaborne presence. Wabanaki routinely reduced English ships, sailors, and cargoes to perquisites of sovereignty, building a new extractive economy with the broken pieces of wider European Atlantic networks.7

When Anglo-French tensions exploded into open conflict in the War of the League of Augsburg (1689–1697), the War of Spanish Succession (1702–1713), the War of the Austrian Succession (1739–1754), and the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), Indians intensified their seaborne campaigns against a British empire militarily stretched thin. The offensive strategy in turn amplified Natives’ indispensability to their French neighbors. Neither France nor England’s calculus for hemispheric dominance, warriors and sagamores repeatedly demonstrated, could discount the variable of Native sea power.8

A technological revolution of sail around the turn of the seventeenth century fueled Wabanakia’s naval and diplomatic agendas. Native oral traditions and European written accounts concur that ships captivated their interest even before Indians encountered the people and goods traveling aboard them. The appreciation did not fade quickly. Though never supplanting traditional birchbark canoes as the common mode of Native transport, the coastal and oceangoing ships and tackle arriving in northeastern waters during the sixteenth century soon proliferated in a culture that long valued maritime mobility. Already by the 1630s, after only a few decades of steady contact with Europeans, Native mariners had so thoroughly assimilated sailing technology that explorers and colonists instinctively assumed the unmarked ships they spied on the horizon belonged to Indians. By the 1730s, after a century of encounters with indigenous sea power, and after four Indian wars and many years of Indian diplomacy, colonial settlers and fishermen spotting such ships braced for what they feared would follow.

Sailing technology enriched and transformed Wabanaki’s political economy by the turn of the eighteenth century. At the same time that it shortened

technological and spatial distances separating Indians and Europeans, sail enhanced the interface between far-flung Native settlements and fostered recognition of their common experience with colonialism. Ships eroded barriers of geography and communication that had contributed to long-standing divisions between locally minded communities vying for resources. On their decks, beneath their sails, at their helms, Indians from Cape Breton Island in Acadia to the Kennebec River in Maine appeared everywhere in northeastern waters, increasingly in polyglot crews skippered by well-traveled sagamores whose growing kinship networks personified a burgeoning society. Native sailors hunted seals, dispatched envoys, plundered cargoes, transported captives, and destroyed settlements. Indians aboard ships gave lie to European pretensions of new world dominance and implemented their own vision for prosperity. Ships provided the connective tissue of a wider Dawnland confederacy as they enriched the confederacy’s constituent communities.9

Sailing vessels also served as vehicles of social mobility in a culture that privileged masculine valor in the hunt and in combat. Pulling Indians seaward and propelling their ships were the currents of an economic crisis that by the early seventeenth century was transforming the landscape and impoverishing Native villages. As the European fur trade depleted northeastern forests and wetlands, Native men struggled to provide for their kin and communities through the traditionally male work of hunting, trapping, and trading. Without furs to process, women found their own economic contributions increasingly marginalized. The decline of economic prospects onshore precipitated a rediscovery of what had served as the source and sustenance of Native culture for generations prior to the arrival of Europeans. At sea, young men cultivated opportunities to prove their courage and honor, traits that garnered approbation in their communities and gave meaning to their lives. In pursuit of new prey, men executed daring feats of physical strength and mental fortitude, exhibiting martial grit for one another and for the old men, women, and children who eagerly awaited their homecoming. The ocean came to function as a theater for the performance of manhood and the celebration of its attendant honors.10

Because it mobilized young hunter-warriors, sail also stabilized power relations within Native communities. By opening new avenues to social advancement and material wealth, ships provided political ballast to Native leaders eager to shore up their influence and prestige at a community level and keep it in the family. The fur trade crisis compromised the authority of headmen whose leadership, while often inherited through elite lineage, had always been subject to the ongoing consensus of their constituents. As the trade’s diminishing returns strained community cohesion and undermined public trust in its elders, sagamores set sail in search of new wealth that could provide material stability for their kin, political security for themselves, and future privilege for their

children. Headmen took to the sea, sometimes with their adolescent sons in tow, to avert a crisis of confidence at home.

The nautical work of dominion thus served more than a material need within Wabanaki communities. It functioned as a social enterprise as much as an economic pursuit. Appropriating sailing technology, investing in a forceful maritime presence, and raiding vessels for captives and cargoes preserved customary gender roles and authority structures amid the environmental and economic upheavals touched off by colonialism. By the early eighteenth century, a new Wabanaki man had emerged. He was first and foremost a man of the sea. Leading him over the waves was a new Wabanaki sagamore, a decorated captain who commanded his own ships, marshaled naval units, spearheaded plundering operations, and enriched his people with the material and human spoils of war. Together the new men steered the course of their confederacy.11

Indians made room for foreigners in their reconceived homelands and waters but made clear the conditions of their welcome and the costs of transgressing them. In essence, the Native conception of a proper Dawnland order included a

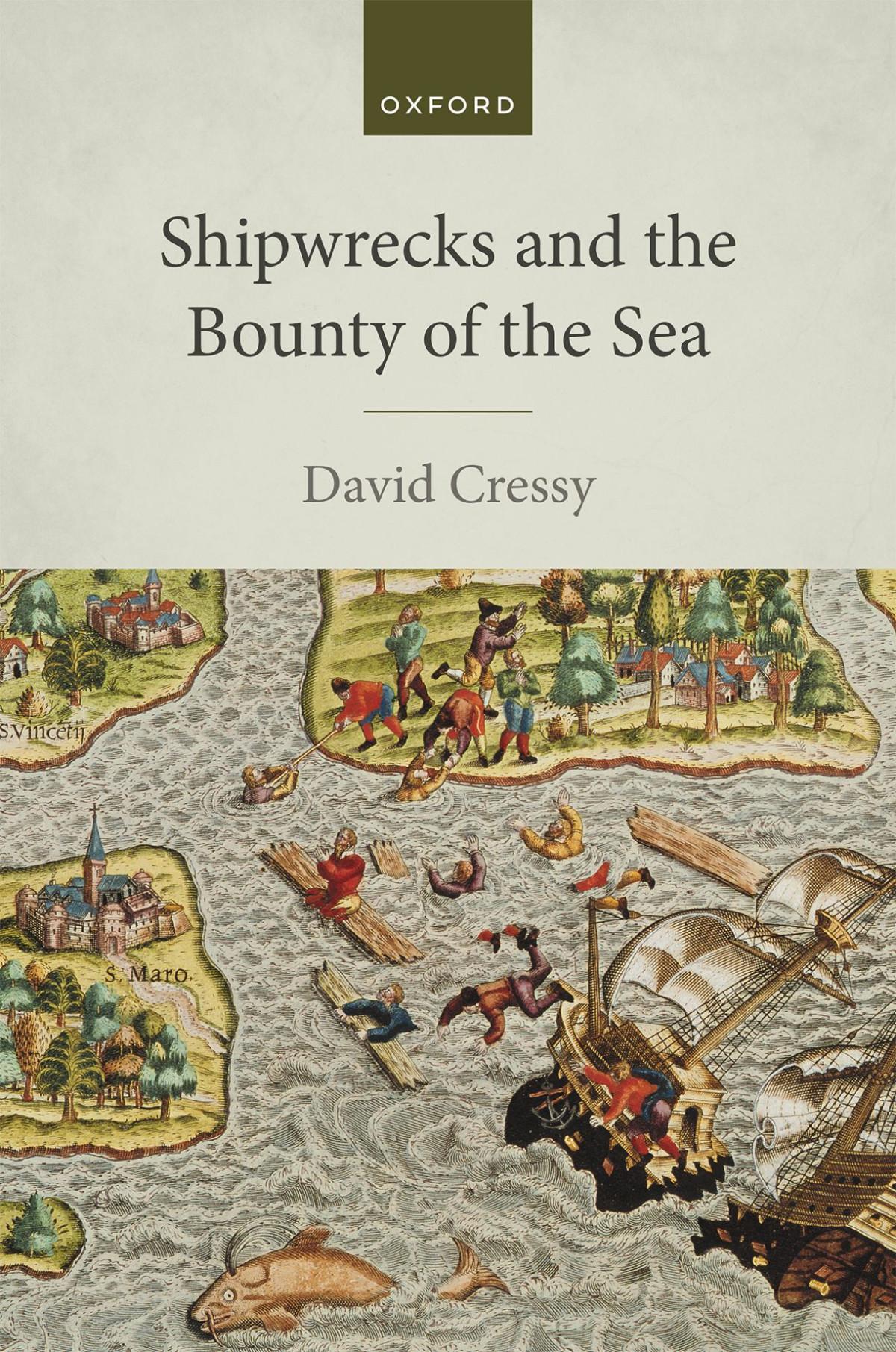

Figure 0.1 Abenaki woman and man, circa 1750, with a style of headwear common throughout Wabanakia. By permission of the City of Montreal, Records Management and Archives, Montreal, Quebec.

profitable, subordinate, and compliant colonial presence scattered across northeastern Massachusetts and Acadia. This expectation would always remain nonnegotiable. Negligent English colonists were periodically reminded of this by Native leaders such as Peter Nunquaddan who, after hijacking a merchant sloop near Minas, Nova Scotia, in 1720, “demanded fifty livres for liberty to trade saying this Countrey was theirs, and every English Trader should pay Tribute to them.” Though Indians achieved their ambition through shrewd diplomacy and calculated violence in the late 1670s and early 1680s, growing numbers of New Englanders began to resist their status and disregard Native assertions of sovereignty.12

Rebellious colonists looked to provincial and imperial leaders for support in their defiance—those whose own claims to supreme authority they hoped were more than a conceit—but mostly they received only disheartening reflections of their own frailty. When they refused to observe their fixed role in Dawnland society, and when they prioritized a foreign power’s hegemonic objectives, English men, women, and children endured punitive and exploitative lashings that reinforced their status in an order determined far from the power circles of Europe. Abandoned to their despair and their Native neighbors, frontier settlers and colonial elites began to see through the fervor of imperial boosters and the paternalism of royal princes to what their empire really was, and they came to accept the fact that they were trapped alone in what Massachusetts militia leader Samuel Penhallow decried as the “storm of the enemy by sea.” The coalescence of a Wabanaki confederacy contrasted sharply with the broken and isolated fragments of English colonialism that it regularly exposed and enveloped in the borderlands.13

Against the bustling but isolated Atlantic fisheries and the secluded coastal habitations of northeastern Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, Indians launched seaborne expeditions to terrify, extract, punish, and coerce. Their tributaries continued to demand relief from Boston, Port Royal, Halifax, and London, imploring authorities to “see the Sea of trouble we are Swimming in,” as Massachusetts residents described it in a petition to their colony’s metropolitan agents in 1690. But the nobles, governors, lawmakers, and soldiers on the receiving end of these requests could never quite rise to the occasion, and their capacity to effect meaningful change proved increasingly doubtful with each new outbreak. It did not matter how loudly or persistently they pled for an end to it all because the reply was always the same. Some felt they had no other choice than to take matters into their own hands. But that never ended well either.14

Colonial leaders in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia sounded their own alarms and sent up their own supplications. They, too, failed to break the troubling cycle. The metropolitan officials in London proved capable of little more than acknowledging the gravity and urgency of a problem everyone on the ground

knew demanded much more. Mired in the increasingly global politics of the day, England’s monarchs, secretaries of state, privy councilors, and Lords of Trade weighed Wabanaki advances against a much wider backdrop. Their decision to invest the empire’s resources elsewhere—in frequent wars with worldwide theaters, in political schemes throughout Continental Europe, in naval patrols around the West Indies—reflected not so much indifference toward two of their colonies but rather the fraught and hydra-headed nature of empire building in the early modern world. Officials had to pick their battles carefully but desperately hoped they were choosing the right ones.

Imperial prioritizing was made more complicated by North American agents who warned that few matters were more critical to the empire than those pertaining to the banks of the northwest Atlantic. The region’s rich stocks of cod and mackerel underwrote England’s expansion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, feeding its booming plantation complex in the West Indies, serving its Royal Navy as “the Nursery of Seamen,” and backing its credit in European markets. New England also owed much of its rapid growth to the fishery. By the outbreak of King Philip’s War in 1675, fish had become so indispensible to the regional economy that officials exempted it from the wartime ban on exports— the only commodity to achieve such status. “The Chief Staple of this Country,” as Massachusetts lieutenant governor William Stoughton referred to the fishery in 1696, continued to flourish over the next century. By the end of the colonial period it constituted the largest sector of New England’s economy, with annual exports totaling over £160,000—roughly half of all exports by value. Far greater was the percentage in Nova Scotia. Though it comprised only one square on the Atlantic chessboard, the North Atlantic fishery figured strategically and decisively in the endgame of supremacy.15

The heart of the ocean powering Britain’s hemispheric ambitions and Wabanakia’s regional ascendancy resided not at the Atlantic’s geographic center but along its periphery. Marine biologists locate the most productive oceanic zones in and around the estuaries, banks, bays, and islands rimming the seas. In the North Atlantic, this edge effect is pronounced in its western and eastern boreal regions where currents intersect over shallows and pull up nutrient-rich water into the sunlight, thus creating an “incubator of life.” After exhausting marine resources around the British Isles by 1500, European fishermen turned their attention to the seemingly limitless waters of the Grand Banks, Georges Bank, and other smaller shoals of the northwest Atlantic. This incubator would come to sustain two competing visions of the ocean and over a century of theft, violence, captivity, and death.16

That both Britain’s imperial fortunes and Wabanakia’s extractive economy relied on a productive fishery was lost on no one. Native seaborne campaigns were not simply a frontier problem; their repercussions spread far beyond

the borderlands to colonial capitals and European centers. Diverse voices throughout the British Empire—from common fishermen, farmers, and traders to military officers, governors, and metropolitan agents—sounded warnings about the micro- and macro-level implications of Indian sea raiding that slowly collapsed Dawnland relations, New England politics, and European empire building into one economic system. The collective outcry communicated a visceral anxiety over local, colonial, and imperial prognoses, for almost all of the afflicted acted on their words and supplemented their pleas with their own desperate solutions. Yet acknowledging the problem and solving it proved stubbornly different matters.17

Neglected by their preoccupied superiors an ocean away, colonial authorities would have to reckon with their problems alone. Massachusetts and Nova Scotia officials struggled to elicit mutual support, but neither proved able to muster the fortitude, resources, and manpower for an intercolonial solution to what clearly was an imperial crisis. Others reached for epidemiological terms and described the plundering operations as plagues, epidemics, and scourges. The dread of infection at once revealed the stealthy and inescapable nature of Wabanaki sea prowess while also exposing a fear of its savage impulses. English colonists exposed to the recurring assaults had good reason to believe that nothing would ever change, and so the cacophony of the settlers and the beseeching of the leaders would fade with the passing of each outbreak as they readied themselves for the next.

Many have forgotten this story, some deliberately, others inadvertently. The process of forgetting began long ago in the unsettled hearts and minds of people central to the events and has carried on for centuries.

English colonists had several reasons to forget. Common fishermen and farmers from Massachusetts and Nova Scotia wished to put behind them their collective experience as victims, which was an identity that defined much of their isolated existence for nearly two centuries. Their struggle to escape the dominion of those who aimed for nothing less than their subjection showed scant signs of hope, reducing them to fixities in a tedious rhythm of extractive and punitive violence. The distress that always accompanied these eruptions sprung from slivers of doubt about the cultural and political feasibility of English imperialism in a North American context.

Governors, legislators, and military officers also had little to gain from remembering. Over time, Massachusetts and Nova Scotia leaders resigned themselves to the fact that they could do very little to stop the never-ending cycle of theft and violence from damaging the people and territory over which they claimed authority in His Royal Majesty’s inviolable name. Each commandeered

ship, kidnapped sailor, impressed crew, slain captain, and razed garrison forced elites to recall the limits of their influence in the imperial competition. In attacks that only grew more elaborate, destructive, and profitable over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Indians exposed the narrow ambit of authority extending from governors’ offices and state houses. The rise of an indigenous dominion proved just how wide, hostile, and unwieldy the Atlantic Ocean could be.

Forgetting also became politically expedient. Britain’s sequence of military victories around the globe in the Seven Years’ War settled a nearly centurylong conflict for imperial domination in North America. By its conclusion in 1763, the war had toppled the tenuous Anglo-Franco equilibrium upon which Wabanaki had staked their own maritime project. Massachusetts colonists would have ample cause to write off the misery of their past failures with a Native confederacy, as their relationship with the mother country deteriorated over the next thirteen years. Quieting the tragic crisis of Indian relations allowed New Englanders to project more forcefully their capacity to flourish beyond the purview of king and parliament. Looking forward and never back made it easier for colonists to believe that they could positively affect the circumstances of their local world, that they were capable of forging a new society unshackled from the endless turmoil of Europe, and that a new American identity supplanted the Britishness they celebrated so fervently for much of the century.18

In the process, Euro-Americans forgot the importance of listening to Indians. English colonists once knew better than to discount Wabanaki voices, but by the end of the Seven Years’ War their descendants saw little reason to take them seriously. Doing so would have offered stark reminders of the story. Many details of the age of dominion have disappeared from Wabanaki discourse, too, in part because of pressure from a dominant culture to dismiss them. But an appreciation of the ocean’s life-giving qualities has endured through material objects and oral traditions.

The amnesia has been perpetuated in the field of early American studies. Though studies of British America’s imperial breakdown are beginning to situate the American Revolution in wider oceanic, hemispheric, and continental frameworks, the literature continues to demarcate the thirteen rebellious colonies from the larger context of British America.19 The empire’s other North American holdings, including Nova Scotia, are consequently relegated to marginalia in the more meaningful history of community building: of provincials from New England to Georgia coming together on a rocky road to revolution and becoming American. The result has been an efflorescence of new perspectives on the revolution’s transatlantic and transcontinental causes and effects, but how and why only thirteen colonies joined together to declare their independence in 1776 remains far less clear. More to the point, by severing the future United States from the future Canada, scholarship on Revolutionary America

has obscured another imperial crisis. This one forced Massachusetts and Nova Scotia together under a shared experience of subjecthood and victimhood before tearing them apart.20

Changing conceptualizations of the Atlantic Ocean further shroud this story. Long accepted as a daunting barrier separating societies, the early modern Atlantic has more recently been appreciated for facilitating movement and enabling contacts. The circulation of commodities, the extension of market capitalism, the diffusion of political ideas, the elaboration of scientific knowledge, and the flow of migrants characterize an oceanic world that links, transmits, and accelerates. Put simply, scholars of this interconnected Atlantic world have stripped the sea of the isolating and inhibiting properties that defined much of its conceptual history and in turn have transformed it into a governable and seamless conduit. The collective effort to Atlanticize four continents has ultimately reduced a disorderly and hostile piece of the historical globe to an organic and rational catalyst of progress.21

Historians have only recently begun to explore Native experiences in maritime spaces, following their canoes along contested coastlines and tracing their migrations aboard Euro-American voyages. Storm of the Sea aims to join this growing corpus while pushing its contours with new insights into the technological, political, economic, and temporal scope of Native maritime power. The advent of sail in the Northeast ushered in a dawn that neither Indians nor Europeans saw coming. By way of their rapid and extensive assimilation of sailing vessels, from ocean-going schooners, sloops, and ketches to lighter single-masted shallops, disparate communities coalesced into a political alliance that for over a century extended and enforced their sovereignty over the heart of the ocean. The Age of Sail fueled the transformation of decentralized huntergatherer bands into a regional Wabanaki confederacy enhanced by the wealth of its tributaries. They took to the sea not merely to preserve, maintain, or resist, not to protect an old relationship to the water, fight for independence, or repel colonialism. Their maritime way of thinking proved far more innovative, opportunistic, and dynamic. Under their sails, Wabanaki endeavored to expand, control, extract, enrich, and thrive as the people.22

Moving the Native seafaring experience beyond traditional canoes and ancestral coasts—thus leaving behind older views of Indians as terrestrial people— allows Wabanaki to be seen where their victims often located them, alongside notorious pirates such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack Rackam, and Black Sam Bellamy. Pirates fast became the talk of the British Empire from 1713 to 1730 when an outbreak of seaborne theft plagued the busiest Atlantic and Indian Ocean shipping lanes and profitable West Indian sugar plantations. The crime spree taxed Britain’s finances and tested its navy’s wherewithal at the same moment that an eruption of Native sea raids roiled waters far to the north. To

New England and Nova Scotia authorities left to reckon with their latest Indian problem, Britain’s highly publicized campaign against piracy offered a winning cause to which they could hitch their historic struggle. Colonial leaders moved quickly to co-opt a proven and expedient rhetoric in their attempt to open another theater of their empire’s war on seaborne crime.23

Early modern Europeans deployed the term “piracy” to describe a specific sort of maritime theft. Pirates were seafaring robbers unaffiliated with a state polity and indiscriminate in their choice of targets. Seaborne plundering was piracy when a victimized nation, determined to police its sovereign territory, said so. An important but sometimes slippery distinction was made between pirates and privateers, seafarers who operated with a license—a letter of marque—from a state sponsor authorizing the attack of enemy shipping, usually during wartime. A privateer was expected to remit the spoils of war to the government, which then compensated him according to prearranged terms. When British victims applied the descriptor “pirate” to Wabanaki raiders, they judged the People of the Dawn to be a pre-political and pre-modern people, primitive individuals whose culture lacked the organizing principles of European empires and the civilized societies those polities built. Indians were people without law and social structure and thus devoid of political community. They were closer to a state of a nature than to the states comprising the international community. In criminalizing and delegitimizing Native sea power, and in accentuating the statelessness of Native society, the rhetorical work of piracy prevented contemporaries from recognizing Indians as political actors.24

Why Wabanaki have since gone undetected as pirates has as much to do with modern conceptions of Atlantic piracy fostered by both Hollywood and academia. Pirates when popularly presented are antiheroes. They are dropouts, rejects, and misfits turned bandits, brigands, and rebels. That they are of European stock, borne of Europe’s civil and economic instabilities, reliant on European trade, and pursued by European courts of law puts them in a decidedly Euro- centric frame. The caricature of the politically and socially primitive outlaw leaves little room to remember Wabanakia’s architects of dominion.25

More familiar histories about American Indians further cloud this story. Vicious tragedies weighing heavily in the Native past—the horrors of epidemic disease, the destruction of European warfare, the violence of US imperialism, the trauma of forced relocation, the poverty of reservations, the racism of white America—have created a paradigm of declension that prevents viewing Native violence as anything more than resistance and regarding Native confederation as anything more than a survival strategy. It reduces Indians to reactionary creatures, always on the defensive, always one step behind the inevitable march of progress.

This book highlights a lingering tendency to read the power dynamics of later periods back into the first two centuries of Indian-European relations. Rather than stressing what ultimately happened to countless Native Americans, it underscores the uncertainty of life in early America, the elusiveness of European agency, and the fluidity of power that render its story deeply foreign and quintessentially colonial.26

The narrative of declension has remained robust in accounts of New England’s early history. Debates about its puritan ancestors aside, the region possesses a rich heritage of lamentation over the supposed decay and disappearance of its Indians. Historians have since recovered a very different Native past, one defined by displacement and loss, adaptation and continuity, and extreme poverty—but also by fierce persistence. These studies have succeeded admirably in exposing the fiction of New England’s “vanishing Indian” trope, but they have neglected part of an indigenous experience that stretched from modern-day Maine to Nova Scotia. While they have recovered an important story of impoverishment, diaspora, intermarriage, and ethnogenesis, they have also left an impression that it is the whole story. The Wabanaki engagement with colonialism diverges sharply from the narrative of marginalization and survival that defines New England’s diverse Indian past.27

The Comanche, Iroquois, and Powhatan remain outliers in a historiographical trend that situates the power politics of Indian country within stubbornly local contexts.28 Though the local turn in Native history has demonstrated that Indian communities can be fruitful units of analysis, it has also contributed to a strong aversion harbored by many Native Americanists toward newer transatlantic and imperial models.29 A reluctance to see Native violence as coherent, coordinated, and systematic, as part and parcel of a political project sanctioned on a scale much wider than the band, the community, and the tribe, explains the highly localized nature of Wabanaki studies. The light shed on individual Wabanaki tribes in Maine and the Canadian Maritimes has left the confederacy as a whole in the dark.30

A counterpoint to perceptions of colonialism as a unidirectional process to a foregone conclusion, Storm of the Sea recovers the experience of indigenous communities that coalesced to achieve stability and growth where Europeans struggled to resist and remain, of Indians who built an economy that grew more elaborate and more profitable over time, always at the expense of Europeans. It is a story of early America in which familiar themes of progress and declension give way to a more human narrative of empire that recalls the unstable, unpredictable, and unmanageable dynamics of power in colonial North America.

The structure of this book reflects its narrative’s disorderly contest for power. While the following chapters are organized chronologically in order to trace the historically contingent changes in Wabanakia’s project of dominion—its successes,

Cape Breton Island

Newfoundland Grand Manan Island

Port Royal/ Annapolis Royal Halifa x Louisbourg Canso Port Toulouse Penobscot Bay Cape Sable Casco

Prince Edward Island Acadia/ Nova Scotia Beaubassin

Minas

Massachuse s Mt. Desert Island

Norridgewock Pemaquid

Boston Ki er y York Wells

Malpec

Miramichi

Machias

Figure 0.2 Map of the northeast, circa mid-eighteenth century. Designed by Bart Wright.

failures, and adaptations—the chapters seek to capture elements of continuity that came to define life in this corner of the Atlantic both for Indians and colonists. The narrative arc commences with the birth of a Dawnland seascape in the beginning of Native time and ends with the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. It aims to convey the dynamism, ingenuity, and evolution that characterized Natives’ blue-water policies while acknowledging the fits and starts that occasionally locked Indians and colonists in a contest for ascendancy.

The book looks eastward, following the lead of the people who have always faced east to meet the dawn. Each chapter begins by reconstructing what Indians would have taken in as they peered into the heart of their ocean. These vignettes assemble shards of evidence subsequently analyzed throughout the respective chapter. The chapter openings envision a Native perspective of the eastern sea in order to reconstitute and remember a more complete and more colonial American history.31

The traces of the past from which this story is retold lie scattered in ethnographies, Native oral traditions, material artifacts, and nearly two centuries worth of French- and English-language sources. It relies substantially on documents written by European settlers, officials, and missionaries, but it attempts to sift through their cultural biases and discern their overstatements by reading them with and against one another and the oral histories, linguistic studies, and archaeological analyses compiled in later periods. Taken together, these multidisciplinary sources afford a more textured portrait of early America, one that foregrounds the perspectives of Natives and common Europeans alongside those of the literate elite.32

Together the People of the Dawn have preserved what most historic cultures of the Eastern Woodlands were forced to relinquish in the nineteenth century. The descendants of Gluskap’s children today—the Penobscot, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Mi’kmaq tribes—maintain a sense of place on ancestral homelands throughout northern New England and the Canadian Maritimes. Though the age of dominion has long since passed, the Dawnland remains and its people carry on at the edge of the ocean.