A NOTE ON NAMES

North and South

The history of Sudan—or The Sudan, or the two Sudans—is one of contested identities. Geographical descriptions are always political. Academics argue any concept of ‘South Sudan’ before the mid-20th century, or even for many decades later, is inaccurate. Before independence in 2011, the bottom half of Sudan was referred to as southern Sudan. As the days towards separation narrowed, that became Southern Sudan, and then finally, South Sudan. After independence, the rump state in the north was known simply as Sudan. I have used the terms North and South even before they became separate states, for sake of clarity.

People,Tribes and Clans

The terms are not interchangeable and have been intensely debated, not least because ‘tribe’ has pejorative connotations of colonial classification. It is, however, what many call themselves. In swift summary, ‘people’ refers to a wider ethnic group with shared language and culture, as well as potentially referring to all member citizens of a formal sovereign state. ‘Tribe’, and the smaller subset of clan within that, is a political grouping—but one rooted in geography and ethnicity.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is the history of how a country was made, but I did not set out to write that story. I came to South Sudan as a reporter, a bystander covering the end of one long war who became caught up in a new one.

Wr iting such a narrative history brings with it many challenges. There is the obligation to record; I have seen how factual reports I made just a few years ago have subsequently become twisted into new and dangerous narratives. Memories are not fixed, but can change in time as a consequence of the suffering people have endured.

But the story is also a personal one; I wanted to share what I saw and heard. The stories told are selective and subjective. I recorded eye witness testimonies of key events—often for the first time—but there are still so many voices missing. This is the story of what I witnessed and the people I was privileged to meet.

Recording suc h stories meant including graphic violence of the most brutal kind. Retelling them risks reliving the trauma for those who have suffered. Yet to gloss over the details would be a betrayal of the courage of those who came forward to entrust a stranger with the darkest moments of their lives. To understand what has happened is the only way there can be hope of solutions. Reconciliation requires forgiveness, forgiveness an acknowledgement of what happened.

For South Sudan, the legacy of the last few years will echo far into the future. The understanding of those years will define what the very nature of the country means to its people.

PREFACE

In the dry season, when the grass grew yellow and thin and crackled underfoot, the bones bleached under the sun poked through the undergrowth. Twisted creepers curled up between the eye sockets of the skulls, some so small they must have been children.

It was July 2011, days before South Sudan would declare independence as the world’s newest nation. I had come to the army barracks in Juba, the capital-to-be, to see the place that for so many symbolised why they voted overwhelmingly to split from Khartoum in the North, to divide Sudan and form their own country.

People called the barracks the White House, and there were few places in South Sudan that evoked as much terror. For over two decades, this was the government in Khartoum’s main torture and execution site in the South. It was where it dealt with those it believed supported rebel forces: activists and aid workers, priests and nuns, doctors and nurses, academics, students, civilians and soldiers. Security officers would march them out of their work, homes, or off the streets. They were removed without question, trial, or need to account for them. Thousands vanished.

The bones were left where the bodies had been dragged and dumped. You could see them from the edge of the dirt track that wound its way along the gentle sloping hillside. Soldiers said there were more piles deeper into the field, but you couldn’t go further, even if you wanted to. Red skull and crossbones signs tied onto thin poles were pushed into the hard earth. They warned of landmines once laid to defend the base, or artillery and mortar shells which had failed to explode.

PREFACE

‘That was the place of our nightmares,’ college student Mabil William had told me before I visited the barracks, as we drank tea on a roadside stall. ‘If you heard someone was taken there, you had said goodbye to them already. They were not coming back.’ William’s father, a teacher, had been accused of backing the rebels and was taken at night by soldiers. He was bundled into a pickup truck that was last seen heading towards the White House. He was never heard of again.

‘When I voted for separation, to say bye-bye to Khartoum, it was places like that we were waving an end to,’ William added, a quiet and shy young man. He wanted to be a teacher like his father had been.

Nor thern soldiers had left the White House only weeks before, the last units to depart before the division of Africa’s biggest nation. For the first time, Southern soldiers—and a journalist—accessed the complex; I had spent several hot days persuading the men in black suits from national security to allow me in.

The bar racks are a scattered collection of low brick buildings with tin roofs on a wide hillside a short walk from the University of Juba, just south of the city centre. The official title of the barracks is Giada derived from the Arabic for ‘the commanders’—but the entirety of the feared complex gained its popular name from the feature most visible from the vantage point of the road, a couple of two-storey whitepainted hospital buildings. I was taken to a low, grass-covered bunker. Our shoulders pushed the heavy metal door open, and I used my phone to light the steep concrete steps down into the darkness. The air was chokingly hot. It took time to see into the gloom, before someone found the switch to turn on a bare hanging bulb, pulsing with the erratic surge of electricity from a generator.

The soldier s and security men who supervised me were as grimly interested in seeing these rooms as I was. As Southerners, they had not been here during the torture, but had heard the stories. The air was thick and intense, heavy with fuel fumes. The burly national security minder rested his hand on my shoulder and peered over my head. Large sacks of rubble lay in the corner. ‘These ones they used when you were brought here,’ he said, prodding one of the bags with his shiny long-pointed shoes. ‘They would lie you down, and then put this one on your back, maybe two of them, maybe even three,’ he added, trying to heave one up in his hand, but finding it too heavy.

‘The only time the door opened was when somebody was being taken out to be killed,’ he said, turning to me with a strange grin. Then he pointed upwards. A pair of handcuffs still dangled from the metal girder in the roof, and he moved them open and closed like a jaw, with a grating squeak. ‘They would hang you here for days,’ he said. ‘I doubt if any other journalist has ever been down here before.’

His companion, silent until then, chipped in. ‘If they did, they didn’t come out alive,’ he said.

We left minutes later, glad for the fresh air outside. Eyes adjusting to the bright sunlight, we walked the short distance through the barracks to another building, a whitewashed series of fetid storerooms, now used as basic dormitories for soldiers, where grey mosquito nets were draped over simple metal cots. The paint was peeling and smeared with dark stains. When the North was in charge, prisoners dragged out of the dungeon would be taken here and executed. For the soon-to-be independent South Sudan, the torture chambers offered the starkest of warnings that the future must not be like the past.

Major-General Mar ial Chanuong Yol Mangok was the new commander of the barracks, a towering man with a shaved head, dressed smartly in a scarlet beret and broad epaulettes with loops of gold wire on his uniform. His fleshy hand gripped mine in welcome, and he continued to hold onto it as he guided my tour around the buildings. ‘In the past, this place was a place of torture, of pain,’ Mangok said. ‘They killed a lot of our people here.’

He looked straight at me, staring uncomfortably and holding my gaze, saying the barracks should be set up as a memorial to remember the crimes of the past. Hundreds if not thousands of bodies lay here, too many for anyone to know, he said. ‘This is a graveyard—a mass graveyard. We need it to be kept as a historical place in the future,’ he said. ‘No more White Houses in the South, so that it will be a free country, where justice and freedom is everywhere.’

I believed him. At the time, there was hope. You heard optimism at every corner, a sense that change had come at last. The dead lying in the grass around the White House might have had their names forgotten and their deaths unmarked, but perhaps they had not suffered in vain.

PREFACE

Two and a half years later, I tried to visit the White House again. Soldiers at a roadblock pointed guns at my motorbike long before I could even reach the gates of the barracks. A stench of rotting flesh drifted on the wind. Smoke rose above the buildings.

On 15 December 2013, after simmering arguments within the ruling party erupted into fury, fighting broke out in the same barracks between Dinka and Nuer members of the presidential guard. The White House, where the torture that had blighted South Sudan was meant to end, would be where the next round of war would start— and this time it was a battle of Southerner against Southerner.

The battles kicked off a civil war of horrific proportions. Revenge and retribution forced people to divide along ethnic lines. Scores were shot in the streets, bodies lay scattered on the roads. Hundreds were rounded up and forced into a room in a police station. The officers opened fire with AK-47 assault rifles.

I’d also hear Mangok’s name again. Now head of the Presidential Guard, a 4,000-man strong Special Forces unit known as the Tiger Division with distinctive striped camouflage uniforms, he led Dinka troops in massacres against Nuer comrades. ‘He executed orders to disarm Nuer soldiers and then ordered the use of tanks to target political figures in Juba,’ the United Nations Security Council wrote as they ordered sanctions against him, including freezing his bank accounts and a travel ban. ‘In the initial operations in Juba, by numerous and credible accounts, Mangok’s Presidential Guard led the slaughter of Nuer civilians in and around Juba, many who were buried in mass graves. One such grave was purported to contain 200–300 civilians.’1

That was just the start. The people fled massacres, ethnic killings and deliberate starvation. A man-made famine was declared. The UN warned of the risk of genocide. It has become one of the most dramatic failures of the international community’s efforts at state-building. Just three years after independence, South Sudan was ranked worst in the world in the list of failed states.2 The war would descend to levels of depravity few could ever have imagined.

Independence was won but freedom was lost, for the new leaders repeated the crimes of those they had ousted. The unity of purpose to achieve separation broke down, and divisions and hatreds were unleashed. Hope turned to disaster. Euphoric ideals collapsed with the bloody, bitter reality of their implementation.

This is the history of a dream. Many have fought. South Sudan did the impossible and won.

It is also the story of a nightmare. For countries are forged not born, and making a nation takes more than unfurling a flag.

‘Khawaja!’ shouted Joseph Bading, calling out the Sudanese name for foreigner as he beckoned me over, waving a carved ebony stick. An elderly gentleman with thin white hair, the primary school teacher was dressed in a ragged yet neatly pressed shirt.

The civil war that had begun in 2013 was raging, and I was lost. It was three years after South Sudan had declared independence and the world had celebrated. The memories of joining the crowds on the streets dancing in delight at their new nation seemed so far away. Now I stood filthy and knee-deep in the stinking sewage that washed down a side street of the UN base in Bentiu, a camp city of thatch and plastic shacks housing over 125,000 South Sudanese civilians. They were crammed together, sheltering from the violence outside, protected by high earth walls topped with razor wire. UN peacekeepers in watchtowers stood guard with machine guns. It felt like a prison.

‘Khawaja,’ he called again. ‘Why do you write? You make the reports, and then you go, but nothing changes,’ he said wearily. ‘We need more food, more medicine. We need all this to end, so tell them that.’

I mumbled the foreign correspondent’s awkward mantra: that I had no power to make change, but those who read the story would understand the situation better, and that might help. He had already been in the camp for more than a year, and he sighed with a deep seen-it-allbefore tiredness. ‘It is okay,’ he said, softening his speech. ‘The khawaja are always writing, it is what they do. We need someone to write all this down, so that what has happened is not forgotten.’

Sometimes the stor ies of suffering you are told can merge into one, and past pains bleed into the present. The horrors done are recounted with a sickening, resigned shrug of exhaustion: this has been done before; now it has happened to me; it will happen again. Tales are told as though in a cave crowded with echoes. Old histories reverberate in the politics, psyche and power struggles of today.

Khawaja, as Joseph Bading dubbed me, is a word taken from the 19th century Ottoman slave raiders for ‘master’.

PREFACE

So much of the story of South Sudan has been one of violence. Far into the past, great leaders rose and fell, as people migrated into new lands and built communities, jostling against each other for control. Then came waves of outsiders.

In the 19th century, foreign forces led large-scale slave raids, treating the people of the South as a raw resource to exploit. The slave raiders set up fortress camps from which to attack, and then to control. They laid the groundwork for rule by a repressive minority whose power was based on using the human capital of people, swapping slaves to purchase loyalty and expand their personal empires of blood.

Next came British officers. They too used military force to break those who opposed them. In speeches they spoke of offering protection, but they subjugated the people to do their will for London’s imperial dreams, and expand hardnosed geo-political ambitions to yoke Africa under their control. The paternalistic colonial policies treated the South like a land unchanged since time began, as though it were a living museum—or more darkly, a human zoo—to be preserved.

The British handed power to an elite in Khartoum. In turn, they built on that repressive state with staggering cruelty, developing a leadership whose survival depended on using the people and land for their narrow pursuit of power. Such dark history cannot simply be buried and forgotten.

Yet at independence, international experts came bearing proposals and plans to fix a land as though it was a blank slate to write upon, swept up in the euphoria of hope for the future. A new round of foreign forces arrived, once again looking at the land either as a wilderness to be explored and exploited, or the canvas upon which to paint themselves as the heroes who saved it.

For while South Sudan was a new nation in name, the past cast a long shadow. It struggled to make a fresh start, and the new leaders followed in old footsteps. Generals who had led the long fight on slogans of freedom bartered the future of the people for themselves. They used them as pawns for their own goals.

Beneath the rhetoric of democracy, freedom, equality and justice, there was no social contract between the government and the people. Instead, there was a simple system where the military men in charge bought the loyalties and services they needed from cash taken from oil.

That money should have developed the nation for all. Instead, it funded a brutal capitalist dictatorship of greed where the people’s dreams were squandered for power. It was less of a government, more of a business conglomerate.3

For a while, the system seemed to work. Yet appetites expanded as the men gorged at the feast. The numbers of people to be paid off grew, as did their expectations and demands. The system that once made South Sudan’s leaders strong would also be their undoing. The resources were finite, and when the cash ran out and people grew angry, the house of cards collapsed. Those left outside the luxuries of power rose up to take what they needed by force.

Today, leaders and rebels alike look to see what they can sell or loot to fund their constituency and keep their power afloat.

For three years, in the run-up to separation in 2011, my sign-off went out across the fledgling nation-to-be on crackly shortwave radios: ‘For the BBC, this is Peter Martell in Juba, South Sudan.’ Technically, the script sent to London was ‘south Sudan’—without a capital letter—to ensure the BBC remained impartial in the independence referendum. Yet such nuances are lost on radio, and Southerners who tuned in heard it very differently. The BBC, they said, backed their dream of a separate nation. In the newspaper debates on what the new nation might be called—Azania, Juwama, Kush, Nile Republic and New Sudan were all suggested—editorials said that if a BBC correspondent called it South Sudan, then that name seemed a sound choice too.

In Juba, I first lived in an oven-like canvas tent that leaked in the rain. Then I moved to a crumbling tin-roof bungalow without electricity or running water, shared with a dozen others. In the day, it served to amplify the hot sun beating down. In the sweats of the night, I’d wake to the thump of plump mangoes hurtling onto the roof, thinking it was gunfire.

I stayed in some of the dustier corners: decaying hotels, army tents, hospitals, aid agency offices and thatch huts. I was sheltered from the sun in mosques and churches. At times, I slept simply on the ground beneath the moon, the curling smoke from cattle dung fires keeping the mosquitoes away. I travelled by motorbike, truck and foot, by bat-

tered boat and canoe, barely-there airplanes and terrifying helicopters. I met leaders and guerrillas, ate with rich and poor, stayed with fighters and farmers. I heard how they saw this land, and how they dreamed it could be.

Today, the foreigners who come to South Sudan stay for ever shorter periods. Institutional knowledge and experience shrink. Even the aid workers with their branded utility vest uniforms and flags have adopted the language of the military and speak of being ‘on mission in the field’. They cross days off the calendar until they jet back out on leave or the next R&R (‘Rest and Recuperation’) holiday cycle. A rare few say they actually live in South Sudan.

For outsiders, it can be hard to see where one round of violence ends and another one starts. The seemingly endless cycle of violence can make it appear that the problems of the South are unsolvable. People call it a ‘tribal’ battle as a lazy shorthand explanation, as though it were a primordial conflict from time immemorial. Yet the reliance that people have on their community is not the cause of violence but, rather, because of it. It is the only security network that is durable enough to survive. Without a government who offer support, people have to care for themselves.

Increasingly, security fears mean that many foreigners rarely venture far beyond the bubble of guarded compounds, except for the briefest of trips. When the UN peacekeepers emerge from their base in their blue helmets and flak jackets, they peer out from the slits of armoured combat vehicles. The visiting diplomatic envoys stepping out from airconditioned Land Cruisers come with analyses written by foreigners, based on security reports of the previous few months. The technocrats who make the decisions on policy and aid sit in Nairobi, Washington or New York. The businessmen who buy the oil, the politicians who pocket the money, or those who sell the guns drink the profits in faraway luxury homes.

I am an outsider too, of course. Strict word limits or two minutes on air meant my stories often provided simplistic summaries: a war between tribes; a rivalry between two men; a conflict between an Arab Muslim north and African south of traditional belief and Christianity, fought over race, religion, land and oil.

Yet as a foreign reporter, I was also privileged with access many did not have. I was able to cross front lines to interview those in power and

their victims, to travel both to war zones and the extravagant hotels of peace talks. I could open the door to other foreigners, whose aid, money, weapons and diplomacy—deliberately or not—helped sustain the conflict. I gathered the stories of those who have not spoken of them before.

Most of all I met ordinar y people, the kind men and women who shared their food, offered me shelter, and looked after an outsider in their land. For the grim lists of statistics fail to mention that in the midst of gloomy broad brushstroke assessments there are children who grow up happy and live life with a smile, men who don’t kill, women who die in peace. There is suffering, yes, but people also live. Parents raise families, go to work, make love, drink and laugh.

The story of South Sudan is not only one of war. I have wanted to show, through laying out the long history, that peace is possible. These are horrifying times today, but there have been horrifying times in the past. They too were overcome. This is not a definitive history; that must be told by the South Sudanese themselves. It does, however, tell the story of how a nation emerged, and of how, for a moment, there was hope.

JUST DIVORCED

‘A long journey of more than 5,000 years.’ John Garang, 2005 peace agreement.

Freedom came at midnight and the people went wild. Tens of thousands of people crammed the streets. Cars careered down potholed tracks of the new capital Juba hooting horns, and arcs of flames spewed out from aerosol cans. Gunfire rattled the hot night with shot after shot aimed at the moon. ‘We are free! We are free!’ screamed mother-offour Mary Okach, waving a flag around her head, the material swirling. She gave a high-pitched ululating cry of joy. It was 8 July 2011, and rule imposed from Sudan’s faraway capital was coming to an end. ‘Byebye Khartoum, hello happiness!’ she wailed. She danced holding hands with her sister, spinning in the centre of the main road.

Next to them was soldier Daniel Bol, dressed in green army fatigues and thumping a makeshift drum of an empty cooking oil can, leaping from one foot to another. ‘Fifty years fighting for independence and if this is freedom, then this is great,’ Bol said, a barrel-chested 30-yearold captain who grew up fighting in war. He bent down to me, offering a beer-soaked bear hug. Down the road came men carrying a giant flag stitched out of bed-sheets in front of a convoy of buses blaring raucous rumba music, the green, red and black rippling as they danced. ‘Junub Sudan, oyee!’ they shouted. ‘South Sudan, oh yes!’

An electronic countdown sign mounted on a metal telegraph pole on a roundabout in the city centre flashed out succinct but misspelled messages in red lights: ‘CONGRATULATION. FREE AT LAST. SOUTH SUDAN.’ One car dragged tin cans on strings, carrying a sign on its back bumper that read: ‘Just divorced.’

Dancing at the base of the countdown clock, 67-year-old mechanic Andrew Amum was breathless in the sweltering night, panting his words out in euphoria, as cars hooted around him and people sang. ‘We have struggled for so many years and this is our day,’ Anum said. ‘You cannot imagine how good it feels.’ Like tens of thousands of the millions who had fled war, Amum had come back after decades abroad to celebrate independence and rebuild his long destroyed home. He’d returned from a Kenyan refugee camp in time to vote in the referendum for independence, which saw a landslide 98.83 percent choose to separate from Sudan. More and more joined the party on the street, shouting in the darkness at the spreading trees above. ‘THANK YOU FOR FREEDOM,’ the flickering screen now read, with a computergenerated flag flapping alongside.

As the people danced, the faraway voice on the faint phone line I’d hooked up via satellite dish to the BBC’s World Service radio could hardly make out a word I said. The final minutes crept towards the first strokes of 9 July when after the longest of wars, Africa’s biggest nation would become two. Not since the age of empires had a new African nation been so created—and none with such international goodwill.

‘What is the mood? Have celebrations begun?’ asked the calm BBC presenter in London. There was only one possible answer; broadcasting the screams of joy live to the world. I held my microphone up to the crowd. The seconds edged towards the pips at midnight, and the countdown clocked ticked to zero. The street exploded in cries.

‘Freedom!’ shouted a man in a military smock festooned with ammunition pouches, clutching one-handed the back of a packed pickup truck speeding past, a beer in his other fist. ‘South Sudan! South Sudan!’ Midnight had come, and a new nation was made.

A few hours later, my motorbike’s weak headlights picked the way home carefully through the capital’s Hai Malakal district, a series of

decrepit bungalows and occasional mud and thatch hut compounds. Only the curious fox-like street dogs seemed awake, the road theirs for now, padding quietly along, scavenging for scraps. I followed them on my bike, bouncing down the bumpy, sandy backstreets to avoid the worst of the drunken soldiers on the checkpoints posted on the main roads. The night air was cooler, though it was still some time off dawn. Formal independence would be later in the day, when the flag of Sudan was lowered at a ceremony with heads of states, marching bands and military parades.

Softly, in the darkness, the candle stubs flickered. Away from the parties, each candle was lit in a spontaneous, unorganised memorial for the millions who had died, placed outside homes on the edge of the track. They offered a more sombre memory of the war’s cost. They were a remembrance of the past, and prayers for the future.

South Sudan had been at war for as long as most people could remember. With each round of conflict, the weaponry and devastation it caused became more intense, from spears to rifles, to artillery, then tanks, fighter jets and helicopter gunships. As I pushed my motorbike into the sandy courtyard of my tin-roof home, the deserted street outside was marked by a line of glittering flames.

President Salva Kiir pushed his black cowboy hat up and rubbed his forehead wearily when I asked about the challenges ahead. There was a deep sigh, then a long pause. South Sudan’s first independent leader, an ex-rebel general who had fought two civil wars to reach this point, looked exhausted before the task of forging a nation had even begun. Decades of war had left everything broken. He stared back at me from the head of the enormous table of the Council of Ministers, deflecting questions as to whether the land was ready to break free. ‘We are not rebuilding this country,’ Kiir said, through his thick beard. ‘We are building it from the beginning.’

The UN creates long lists of indicators of a country: health, economic, education and development rankings. At freedom, South Sudan shot straight to the bottom rung of almost all, with some of the worst development indicators of any nation on earth. The wars had forced millions of people into exile and left those who stayed destitute.

When the country split, the rump state of Sudan in the north saw its position on paper move upwards. The situation in the South was so bad that it had dropped beneath a nation accused of carrying out genocide in Darfur. A 15-year-old girl in the South had a higher chance of dying in childbirth than completing school. In fact, if you looked at statistics of how many mothers died in childbirth, conditions were actually significantly better in Afghanistan under the Taliban.1

With oil providing 98 percent of government income, South Sudan was the most oil-dependent nation in the world. Yet there was little infrastructure beyond wells and pipelines. For the 10 million people, just one percent had access to a regular electricity supply. Even in Juba, power came from smoky diesel generators or solar panels.2 For villages in the oil zones, often the only impact they saw was the filthy drinking water covered in scum, that tests showed to be riddled with toxins.

‘When the assembled presidents and prime ministers board their official planes to return home, the challenges that remain will be daunting indeed,’ UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said, hours before the flag of the united Sudan was lowered and South Sudan’s was raised. ‘On the day of its birth, South Sudan will rank near the bottom of all recognised human development indices. The statistics are truly humbling.’

Those in South Sudan at independence could see the risks ahead. ‘The world’s first pre-failed state,’ cynics quipped. For there were few places on earth as badly damaged, undeveloped and destroyed as South Sudan.

Yet the warnings didn’t put off the people; this was a party a long time coming. ‘When you’re being beaten by your husband, you have to leave the marriage,’ said Mercy Zamoi, a single mother who, after the new flag was raised, gave birth to a tiny, struggling, wailing baby. She called her daughter Independence.

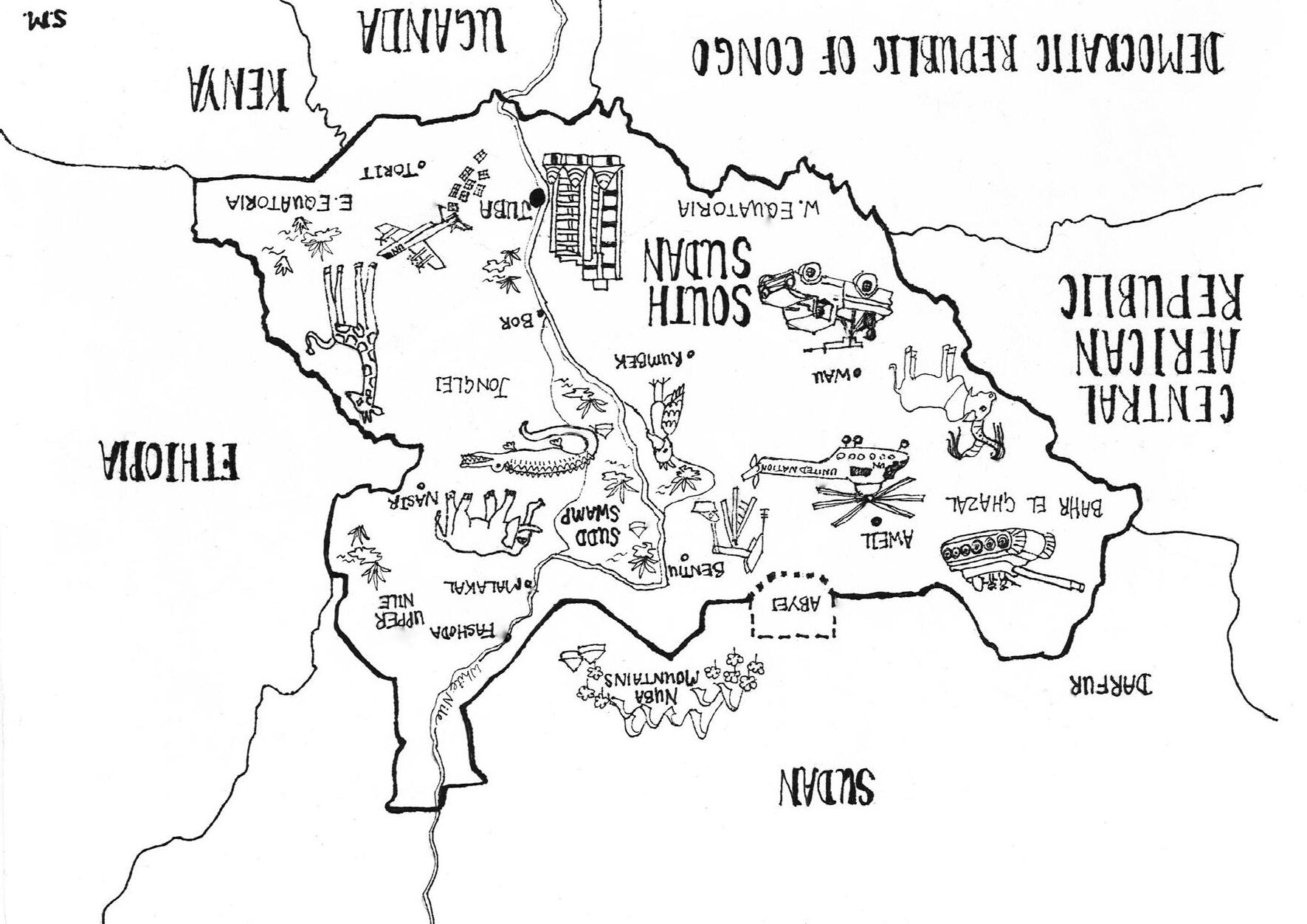

It is a vast land. The two Sudans, North and South together, are the size of the United States east of the Mississippi. Transpose a map of the Sudans onto Europe, and they stretch from France to Russia, Norway to Turkey. The South alone, which made up about a quarter of the total of a united Sudan, is the same as Spain and Portugal combined.

Distances become multiplied by difficulty. Going by road from Khartoum in the North to Juba in the South isn’t really viable, except