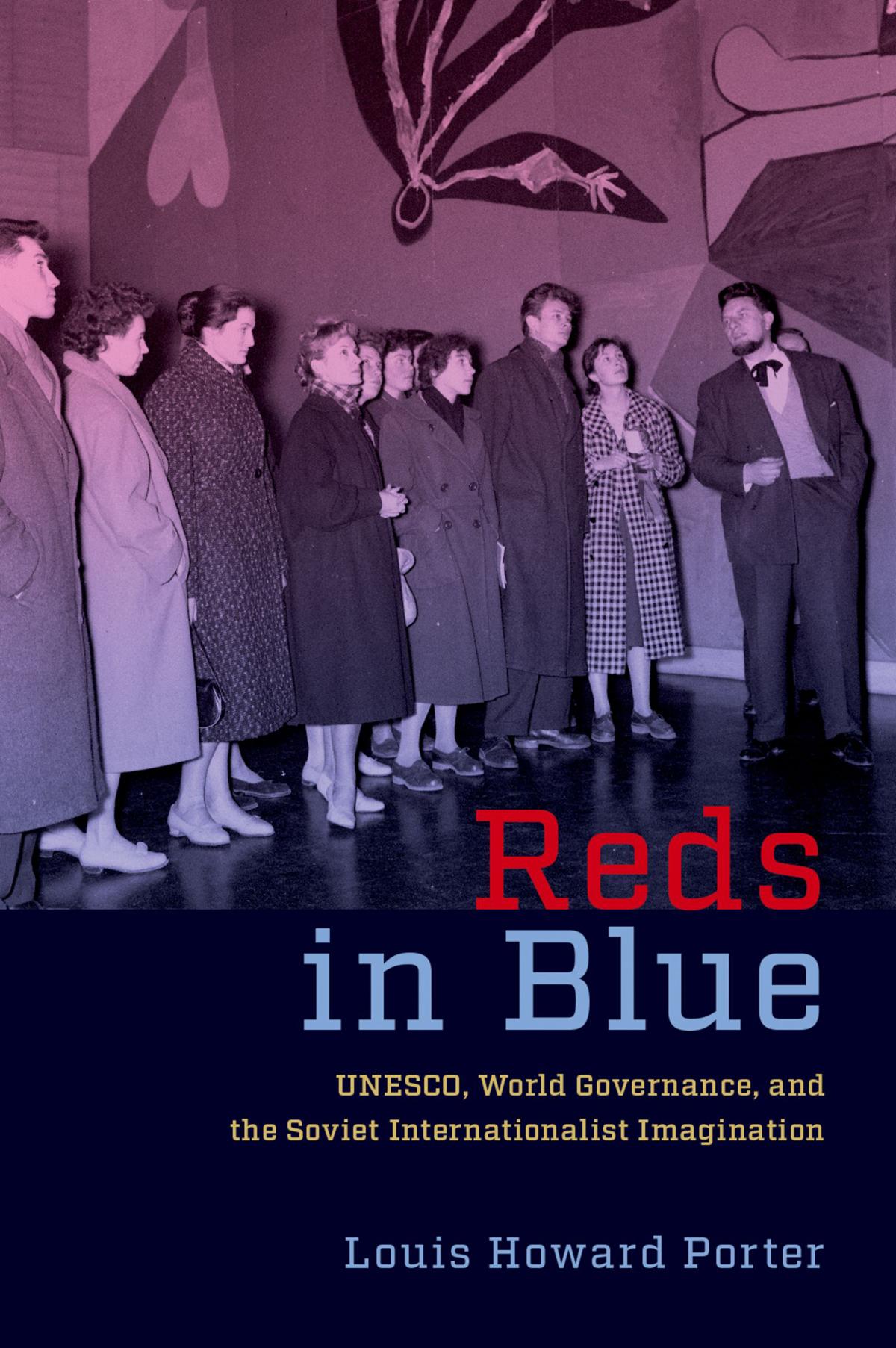

Reds in Blue: UNESCO, World Governance, and the Soviet Internationalist Imagination Porter

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/reds-in-blue-unesco-world-governance-and-the-soviet -internationalist-imagination-porter/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Energy Culture: Work, Power, and Waste in Russia and the Soviet Union Jillian Porter

https://ebookmass.com/product/energy-culture-work-power-andwaste-in-russia-and-the-soviet-union-jillian-porter/

A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, world heritage, and the dream of peace Lynn Meskell

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-future-in-ruins-unesco-worldheritage-and-the-dream-of-peace-lynn-meskell/

Blue Book on AI and Rule of Law in the World (2021) Yadong Cui

https://ebookmass.com/product/blue-book-on-ai-and-rule-of-law-inthe-world-2021-yadong-cui/

God Save the USSR: Soviet Muslims and the Second World War Jeff Eden

https://ebookmass.com/product/god-save-the-ussr-soviet-muslimsand-the-second-world-war-jeff-eden/

Republics of Difference. Religious and Racial SelfGovernance in the Spanish Atlantic World Karen B. Graubart

https://ebookmass.com/product/republics-of-difference-religiousand-racial-self-governance-in-the-spanish-atlantic-world-karen-bgraubart/

Sundarban Mangrove Wetland (A UNESCO World Heritage Site): A Comprehensive Global Treatise Santosh Kumar Sarkar

https://ebookmass.com/product/sundarban-mangrove-wetland-aunesco-world-heritage-site-a-comprehensive-global-treatisesantosh-kumar-sarkar/

The Future of the World: Futurology, Futurists, and the Struggle for the Post Cold War Imagination Jenny Andersson

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-future-of-the-world-futurologyfuturists-and-the-struggle-for-the-post-cold-war-imaginationjenny-andersson/

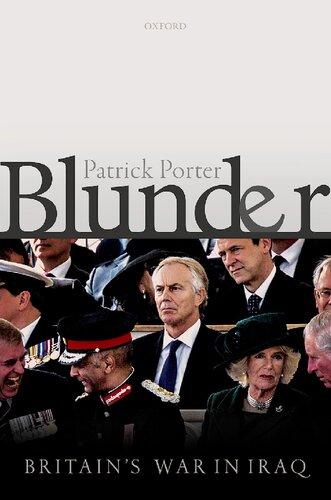

Blunder: Britain's War in Iraq Patrick Porter

https://ebookmass.com/product/blunder-britains-war-in-iraqpatrick-porter/ In Deep Blue Saffire

https://ebookmass.com/product/in-deep-blue-saffire-2/

Reds in Blue

Reds in Blue

UNESCO, WorldGovernance, andthe Soviet Internationalist Imagination

LOUIS HOWARD PORTER

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Publication of this book was made possible, in part, by a grant from the First Book Subvention Program of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–765630–3

eISBN 978–0–19–765632–7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197656303.001.0001

ForL.J.andGeorgia

Contents

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Introduction: Really-Existing World Governance and Soviet Social ism

PART I. CONVERGING INTERNATIONALISMS

1. Dual Power in World Governance: The USSR Out of UNESCO, 19 45–1953

2. The Key to the Whole System: The USSR in UNESCO, 1954–195 9

3. Strange Bedfellows: The USSR and UNESCO in a Changing Worl d, 1960–1967

PART II. EVERYDAY WORLD GOVERNANCE

4. “No Neutral Men”: Soviet International Civil Servants and Life in the Soviet Colony in Paris

5. Working for the World: Soviet International Civil Servants in the UNESCO Secretariat

6. Gathering for One World: Soviet Participation in UNESCO’s Intern ational Public Sphere

7. Reading a Better World: Soviet Participation in UNESCO’s Readin g Public

Conclusion: A University in the Air

Notes

Bibliography Index

Acknowledgments

When I stumbled onto this topic about a decade ago, I had no idea what I was doing or getting myself into. This changed only thanks to the colleagues, friends, and family who helped me figure it out along the way. In its initial form as a dissertation written at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, the project benefited from the thoughtful and compassionate mentorship of my graduate adviser, Donald J. Raleigh, who generously shared his immense knowledge of the field of Soviet history while allowing me the independence to follow my own intellectual journey. His advice on how to navigate the complexities of the historical profession was crucial in ensuring this book’s completion. I also learned a lot from other members of my dissertation committee (Chad Bryant, Louise McReynolds, Eren Tasar, and Susan Pennybacker), all of whom improved the story I tell here by helping me place it in broader chronological and geographical contexts. Before I defended my dissertation before this committee, I presented an earlier version of chapter 5 at the Carolina Seminar: Russia and Its Empires, East and West, where fellow graduate students (including, among others, Dakota Irvin and Virginia Olmsted-McGraw) asked insightful questions.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the summer of 2020, I moved my family halfway across the country to start a new job at Texas State University. Having never spent more than forty-eight hours in Texas and unsettled by the anxieties of lockdown, I could not have foreseen the supportive and vibrant communities that would welcome me in the Lone Star state. Since then, I have had the good fortune of working with an exceptional group of scholars in the Department of History at Taylor-Murphy Hall. The Swinney Writing Group (Margaret Menninger, Carrie Ritter, Elizabeth Bishop,

and other colleagues) workshopped a segment of this book, giving me a better understanding of how I wanted to organize the chapters. More important, the History Department at Texas State has treated me like a human being, offering kindness and empathy when life intervened. It is hard to imagine a better department chair than Jeff Helgeson, whose flexibility and empathy have made the book writing process considerably less stressful. Likewise, the mentorship of Ken Margerison, who continued to offer words of wisdom even after his retirement, has clarified and enriched my time at Texas State. I am also thankful to José Carlos de la Puente for easing me into my service duties in the department, thereby giving me the time needed to put the finishing touches on this book. Last, I have been incredibly lucky to work alongside Miranda Sachs and Justin Randolph, who have extended a helping hand when my family was going through difficult times.

The thinking behind this book has been shaped by diverse feedback from scholars in the field. At the annual meetings of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) and the Southern Conference on Slavic Studies (SCSS), discussants, chairs, co-panelists, and members of panel audiences offered perceptive observations and probing questions that led me to sudden epiphanies. Other scholars have improved my approach to this subject through extensive written reflections. Parts of chapter 7 of this book have been published as “ ‘Our International Journal’: UN Publications and Soviet Internationalism After Stalin,” Russian Review 80, no. 4 (2021): 641–60. As I developed this article, the constructive comments of the Russian Review editorial team (particularly Associate Editor Brigid O’Keeffe) and the journal’s reviewers inspired me to reframe my project and sharpen its arguments.

In the course of conducting research and writing, I received financial and other forms of aid from a variety of sources. The Fulbright US Student Program and various grants from the UNC Department of History kickstarted my archival work in Russia and at the UNESCO Archives in Paris, France. At these archives, I unearthed documents with the assistance of knowledgeable specialists

(particularly archivists Adele Torrance and Eng Sengsavang at UNESCO). In addition, I completed my dissertation with the help of a writing fellowship from the UNC Graduate School; wrote a proposal for the book while living on funds from ASEEES’s Robert C. Tucker/Stephen F. Cohen Dissertation Prize; and used a Research Enhancement Program (REP) grant from Texas State to take a lastminute research trip. As the book became a reality, it also received funds from the ASEEES First Book Subvention Program. Moreover, the inclusion of the photos in this book would not have been possible without the permissions and audiovisual teams at various repositories (UNESCO, Eastview Information Services, Alamy, and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library), while Corinne Schwab graciously assented to my reproduction of an excellent photo taken by her father, Éric Schwab.

At Oxford University Press (OUP), I had the privilege of working with Susan Ferber, who patiently guided me through the process of writing my first book. Her astute comments and incisive edits on the penultimate draft made what follows a much better read. Similarly, the two scholars she selected to review the manuscript offered both encouraging words and gentle criticisms, cajoling me to make important changes that I might otherwise have been too stubborn to make. I also appreciate the hard work of the copyediting, indexing, and other professionals at OUP and appreciate their steering this book through production.

And finally, my family has made possible my career, providing me with the kind of love and support necessary to keep my eyes on the prize. I am thankful beyond words to my wife, Liz, who has put up with the erratic work schedule, long trips abroad, and financial precarity part and parcel to this profession. Her confidence in me has seen me through. My parents, Karen and Lou, are the best anyone could have, having my back and cheering me on during every stretch of this crazy trip called life. I have grown to appreciate their love and guidance even more since the arrival into the world of my two rays of sunshine, Louis James and Georgia Porter. Through rain, wind, and water, seeing their shining faces makes this all worthwhile.

Abbreviations

AN SSSR Academy of Sciences of the USSR

BMS UNESCO Bureau for Relations with Member States

BPM UNESCO Bureau of Personnel and Management

BSE Great Soviet Encyclopedia

BSSR Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

CAME Conference of Allied Ministers of Education

CBS Columbia Broadcasting System

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

COMINFORM Communist Information Bureau

COMINTERN Communist International

CSCE Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

DST Direction de la surveillance du territoire

ECOSOC UN Economic and Social Council

EEC European Economic Community

EPTA UN Expanded Program of Technical Assistance

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FRG Federal Republic of Germany

GDR German Democratic Republic

GKES State Committee for Foreign Economic Relations

GKKS State Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

ICSAB International Civil Service Advisory Board

IDA International Development Association

IIB International Institute of Bibliography

IIL Soviet Foreign Literature Publishing House

IINiT USSR Institute for the History of Science and Technology

IIT Bombay Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay

ILO International Labor Organization

KPSS Communist Party of the Soviet Union

MGPIIIa Moscow State Pedagogical Institute of Foreign Languages

MID USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MINEDEUROPE Ministers of Education of Member States of the European Region

MINVUZ USSR Ministry of Higher and Secondary Special Education

MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NKID USSR People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs

OAS Organization of American States

OAS Organisation de l’armée secrete

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

PRC People’s Republic of China

TAB UN Technical Assistance Board

TsK KPSS Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

UDC Universal Decimal Classification System

Ukrainian SSR Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

UN United Nations

UNCSW UN Commission on the Status of Women

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

UNKRA United Nations Reconstruction Agency, Korea

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

VGBIL USSR All-Union State Library of Foreign Literature

VOKS USSR All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with the Abroad

WHO World Health Organization

Reds in Blue

Introduction

Really-Existing World Governance and Sovie

t Socialism

In August 1974, the American magazine Saturday Review published a special issue, “2024 A.D.—A Probe into the Future.” Released the same month that President Richard M. Nixon resigned from the presidency in the wake of the Watergate scandal, the issue presented essays in which an assortment of American and foreign luminaries (Neil Armstrong, Norman Podhoretz, Kurt Waldheim, Milovan Djilas, and others) predicted the fate of the world in fifty years. Among the contributors to the magazine was nuclear physicist turned disarmament activist Andrei Sakharov, who shared his take on humanity’s prospects from the USSR. In his contribution, the Soviet scientist looked to the future to clarify the problems of the present, enumerating the many “destructive tendencies of contemporary life” in the 1970s, from environmental degradation to the threat of nuclear war. For Sakharov, the fight against these threats necessitated that humanity reverse “the disintegration of the world into antagonistic groups of states” and instead facilitate the “convergence of the socialist and capitalist systems.” In his eyes, an important institutional mechanism for the realization of this convergence already existed. “A major role must be played,” he declared, “by international organizations, such as the United Nations and UNESCO, in which I would like to see the beginning of a world government with guiding principles based on global human rights.”

Sakharov went on to outline “several futurological hypotheses” built on this premise of global integration through world governance. He foresaw in 2024 an earth divided into a “Work Territory (WT)” and “Preserve Territory (PT).” The smaller WT zone, “where people will spend most of their time,” would consist of “giant automated

and semi-automated factories” as well as “super-cities” of apartment buildings with cutting-edge technology. These urban cores would be encircled by sprawling suburbs, which in turn would give way to stretches of farmland producing enough to feed the world’s population. In the air above the WT, “flying cities” powered by solar and nuclear energy would orbit the earth. Beneath the earth’s surface, a “system of subterranean cities for sleep and entertainment, with service stations for underground transportation and mining” would bustle out of sight. Meanwhile, the larger PT zone would function as a world park, “set aside for maintaining the earth’s ecological balance, for leisure activities, and for man to actively reestablish his own natural balance.”

This extravagant prophesy was premised on the emancipatory potential of the global exchange of knowledge and information. Sakharov envisioned the world of the 2020s as not only enjoying the fruits of spectacular technological leaps (such as the replacement of the automobile with “a battery-powered vehicle on mechanical ‘legs’ ”), but also the creation of a “single global telephone and videophone system” as well as a “universal information system (UIS).” The latter, he dreamed, would “give everyone access at any given moment to the contents of any book that has ever been published or any magazine or any fact.” Obviously, Sakharov cautioned, such an advanced information network would not exist until “far in the future, more than fifty years from now.” But once it did appear, the network’s “true historic role” would be “to break down the barriers to the exchange of information among countries and people.”1

Sakharov’s identification of the UN system, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in particular, as the building blocks for this future world order reveals a deeper truth about these institutions and the Soviet experience of them. After the death of Josef Stalin in 1953, Soviet citizens from a range of backgrounds worked in the bureaucracies, attended the conferences, and read the publications of noncommunist international organizations. In the course of participating in these

activities, they experimented with novel ideas and practices based on the premise of world governance. This experimentation, though at times leading to grandiose schemes, remained far more grounded in the realities of the twentieth century than Sakharov’s fantastical reverie. Nevertheless, the discourses and practices in which international organizations included a small but influential part of the Soviet population contained the promise and possibility of a better world in the future. For these Soviet internationalists, the UN method of world governance offered a flawed yet important tool for solving the world’s problems. It encouraged them to declare membership in an international community and to act out of a sense of world civic duty to address these problems. Citizens of the USSR and of the world, Soviet participants in international organizations used these bodies to imagine and work for global change for the benefit of their country and humanity writ large.

This book is a history of these works and imaginations. Examining Soviet participation in UNESCO from the country’s enrollment in the organization in 1954 to the eve of détente in 1967, it chronicles the rich experiences of Soviet citizens in the distinct milieus made by international organizations. Due to a widely held assumption that the world needed to transcend the nationalist belligerence that had led to the massively destructive conflicts of the first half of the twentieth century, the number of international organizations grew exponentially in the postwar era. The rise of this constellation of internationalist entities, which revolved around the newly created UN and its specialized agencies, heralded the advent of multilateral diplomacy as a major tool for solving global issues in every imaginable sphere of human activity. These organizations sought to reform the established order through varying degrees of institutionalized cooperation among peaceful nations. As a result, they extended to the world’s population ideas of world governance, world civic duty, and international community.

Sakharov’s singling out of UNESCO reflects its unique status both within the Soviet Union and the wider mid-twentieth-century world. While the continued rapid growth in the number of international organizations has since marginalized it as just one of many such institutions, this UN specialized agency represented one of the most radical and idealistic inventions of the postwar movement for world governance.2 Founded in 1946 and headquartered in Paris, UNESCO oversaw multilateral diplomacy in the expansive spheres of education, science, and culture. The organization hosted conferences for scholars and other professionals, released publications on a variety of subjects, and provided educational technical assistance around the globe. It operated as both a force in its own right in the fields under its mandate and as an intergovernmental sponsor of dozens of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).3

Before Stalin’s death in 1953, the USSR had, at best, an ambivalent relationship with noncommunist international organizations. Although it had helped found the United Nations, it opposed making the world body much more than a coalition of the great powers that had emerged as victors from the war.4 It refused to join UNESCO and other major UN agencies beyond the Security Council and General Assembly. In these early years of the Cold War, the Soviet state accused UNESCO in particular of spreading “cosmopolitanism,” an epithet drawn from the xenophobic and antiSemitic campaigns inside the Soviet Union that coincided with the ratcheting up of international tensions. After Stalin’s death, however, the new Soviet leadership joined UNESCO and a number of other international organizations, including the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO).5

Soviet entry into these institutions marked a watershed moment in Soviet thinking about world governance. From the 1950s onward, noncommunist international organizations became legitimate options in the toolkit from which the Soviet state drew to conduct diplomacy in areas beyond direct negotiations over war and peace. Although the USSR continued to boycott a handful of these organizations over

specific ideological concerns, the majority of them were redefined as progressive phenomena central to post-Stalinist foreign policy. In 1959, G. A. Mozhaev, an international legal scholar working for the Soviet UNESCO Commission—which oversaw the country’s participation in the UN agency—framed noncommunist international organizations as positive forces on the world stage in a groundbreaking Marxist-Leninist analysis. “The huge increase in international organizations and the enhancement of their role in international life,” he theorized, reflected “the objective process of the further complication and development of international relations, caused by the unprecedented rise of science and technology and the enormous growth of the consciousness of peoples.”

Mozhaev predicted that such institutions would only become more important as the world became more interconnected. “There is every reason to believe that in the future, with the acceleration of social progress, the role of international organizations in the system of world political, economic, scientific-technical, and cultural relations will steadily grow.” Moreover, no international organization had more strategic importance than UNESCO. In Mozhaev’s words, the agency deserved special attention as “the largest and most important international organization in the areas of education, science, and culture.” As an intergovernmental sun around which a multitude of NGOs orbited, UNESCO was also “the key to the whole system of international nongovernmental organizations of an ideological nature.”6

The normalization of Soviet relations with UNESCO after 1953 enabled Soviet nationals to engage in global discussions on topics ranging from their individual professions to worldwide problems. Recent histories of Soviet internationalism have shown the aftereffects at home and abroad of the country’s bilateral cultural diplomacy with countries, blocs, or particular “worlds.”7 But the role of international organizations—and particularly the UN—in the practice of Soviet internationalism remains understudied, even as the world body has attracted renewed interest over the last two decades.8 Scholars have recast the UN as more than an alternative

setting for diplomacy by exploring how it was embedded in and shaped global processes.9

By putting these hitherto siloed scholarships on Soviet and UN internationalisms in conversation, this book provides the first history of the Soviet reception of world governance through international organization. At first glance, the histories of UNESCO’s method of world governance and the socialist internationalism of the Soviet state run on parallel tracks, forming unique intellectual genealogies as dichotomous as the Cold War. The juxtaposition of the symbolic imagery of UNESCO and the USSR illustrates the divergent end-goals of these two internationalist institutions. On the one hand, the hammer and sickle on the red backdrop of the Soviet flag evokes the militant struggle born out of the French revolutionary tradition and aimed at uniting workers of the world to upend the established order under a star pointing to the five inhabited continents.10 On the other hand, the substitution of the “UNESCO” acronym for the columns of the Parthenon on the UNESCO logo is emblematic of the organization’s ambition to serve as the preserver of the culture and knowledge built atop the foundation of the established order. Harkening back to a time before the revolutionary tradition extolled by the Soviet Union, the UNESCO logo manifests the organization’s mission to act as the keeper of the tradition of the Enlightenment and as the reincarnation of the genteel “Republic of Letters” that preceded the upheaval unleashed by the French Revolution.

Figure I.1 These two Soviet stamps from 1976 depict the symbolic imagery of the USSR (left) and UNESCO (right). They reflect how both Soviet and UNESCO internationalisms harbored global aspirations but differed in their self-conceptions as (respectively) disruptor or curator of the established order. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Dreamstime.com. © Bob Suir.

The oppositional end-goals of these two institutionalized internationalisms, however, conceal their critical points of theoretical convergence. Just as Marxism took as self-evident certain presuppositions and frameworks born out of the Enlightenment, Soviet internationalism shared presuppositions and frameworks with the internationalist currents of thought that would inform UNESCO. All such internationalisms rely on specific features of modernity, such as new means of travel and communication, to imagine international community.11 Both Soviet and UNESCO internationalisms also sought to mobilize this international community to international civic action, appealing to a sense of civic duty to make a better world. Both

belong, in other words, to what historian Mark Mazower calls a “larger genus of secular internationalist utopias,” all of which harbored “a vision of a better future for mankind, one that lies within our grasp and power and promises our collective emancipation.”12

More concretely, Soviet engagement with UNESCO continued a tradition of Russian and Soviet experimentation with noncommunist visions of world governance, world civic duty, and international community. Indeed, Soviet enrollment in UNESCO and other UN agencies institutionalized long-standing efforts by Russian and later Soviet citizens to imagine and work for a better world through worldwide civic action and governance. As far back as the late nineteenth century, movements such as the one to globalize Esperanto—an international language invented in the Russian Empire and officially endorsed by UNESCO in 1954—extended to Russian subjects of the Tsar a sense of world civic duty and creative belonging to international community.13 Likewise, historians have traced the kind of popularly mandated world governance that would inform the UN system back to the Russian Empire and its last ruler, Nicholas II, who initiated the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conferences on international law. Unlike earlier instances of great-power multilateralism, these highly publicized “peace conferences” inspired citizens from around the world to imagine themselves as part of an international community with influence over world governance. Members of the Russian educated public readily joined this community, organizing meetings and collecting thousands of signatures in favor of world governance at the Hague.14 In the same spirit, representatives of the Russian Duma, the quasi-parliamentary body created after the 1905 revolution, took an active part before 1914 in the Interparliamentary Union (IPU), the first international organization practicing world governance based on popular representation of an imagined international community.15

The cataclysms of the Great War and the 1917 revolution disrupted the ties between the country and such noncommunist movements for world governance. The new Soviet state refused to

join the IPU, only returning to it in 1955—a year after Soviet enrollment in UNESCO.16 The Soviet state also sat out the League of Nations, the interwar predecessor to the postwar UN, for all but five years of its existence. Consequently, the USSR had a fleeting official presence at UNESCO’s direct institutional predecessor, the League’s International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation.17 Instead, Soviet leaders promoted their own extensive apparatuses for international solidarity, such as the Communist International (Comintern) and the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with the Abroad (VOKS).18

Yet neither the League nor the Soviet diplomatic complex had a monopoly on interwar initiatives premised on world governance, world civic duty, and international community. In fact, UNESCO’s method of world governance through intellectual and cultural exchange had antecedents in other, lesser-known projects for global integration, a number of which earned the support of members of the Soviet educated public from the interwar period.

Before the Second World War, for example, the ambition to put intellectual exchange in the service of world governance took on its most fantastical incarnation in the utopian schemes of Belgian pioneer of information science Paul Otlet. Founder of the International Institute of Bibliography (IIB) in Brussels, Otlet worked to create a “Universal Bibliography,” or a reference database for all printed texts in existence. To organize this universal corpus of knowledge, he developed the Universal Decimal Classification System (UDC), a modified version of the Dewey Decimal System. These ventures constituted the information building blocks of a more far-reaching plan to create a global information “depot” that would house international associations, a library, museum, and “international university.” This “Mundaneum,” as Otlet called it, would also be the seat of a world government that, accompanied by the creation of a world calendar and world language, would facilitate global intellectual integration.19 Otlet’s dream of realizing world government through intellectual exchange anticipated the aspirations that some of its founders brought to UNESCO. Picking up where

Otlet left off, UNESCO would act as a world “depot” for knowledge; serve as an intergovernmental hub for NGOs; and operate as a leading international organization for information and library science. Otlet’s internationalist project also acquired an ardent fan base among Soviet librarians and bibliographers.20 After 1917, his UDC rose to power alongside the Bolsheviks. In the early 1920s, the young Soviet state mandated the use of the UDC in libraries and in the Knizhnaia letopis’, the national bibliography released by the USSR State Central Book Chamber.21

Other interwar predecessors to UNESCO would similarly inspire Soviet citizens. The city of Bruges played host in the 1930s to world congresses calling for international action to protect culture in times of war. These congresses were part of an international grassroots movement inspired by the idiosyncratic ideas of Russian émigré painter Nicholas Roerich. In the late 1920s, Roerich had called for an international pact that would safeguard cultural and intellectual heritage from the mass destruction of war. This proposal culminated in an Inter-American treaty known as the “Roerich Pact,” which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed at a ceremony in the White House in 1935.22

Roerich’s movement was based on a conviction that peace depended on—in the words of one Roerich supporter—“the sensitizing of human consciousness” through global cultural conservation. This belief presaged UNESCO’s core premise that, in the words of its charter, “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed.”23 In addition, Roerich’s international treaty was the immediate predecessor to UNESCO’s various agreements to protect world heritage in the postwar era.24 The Russian émigré’s thinking would also influence Soviet internationalism. After Stalin’s death, Soviet authorities incorporated Roerich’s work into their own message of “world peace,” commemorating his life and activism as part of a shared internationalist tradition.25

Like Roerich and Otlet, UNESCO and the Soviet state practiced “transformative agendas” to reconstruct “the minds of men” through

universal enlightenment. They conceived of intellectual exchange— and the globalization of information, knowledge, and culture in particular—as a means of refashioning subjects of the present into citizens of better worlds to come.26 The hopes of UNESCO’s founders that the organization would act as an intellectual and moral center for the world echoed on a global level the utopian pretensions of the Russian (and later Soviet) intelligentsia to serve “as the conscience of the nation” by exemplifying “the learning of all humanity” and employing this learning to create “new people.” Yet while the Bolsheviks launched campaigns to create a “new Soviet man,” UNESCO aimed to mold a new internationalist man exhibiting an “internationally minded” consciousness.27 If Stalin considered Soviet writers “engineers of the human soul” for socialism, UNESCO viewed itself as an engineer of the human mind for peace. As this book will show, the Soviet experience of the UN agency reflected these homologous utopian premises, which encompassed a spectrum— from red to blue—of internationalist modernity.

The theoretical convergences of Soviet and UNESCO internationalisms translated into similarities in how the two played out in practice. In the end, both Soviet socialism and world governance suffered the same fate—that of idealistic projects realized in institutions (the USSR and the UN) best known for their failures to live up to their promises. As such, they epitomize the chasm between idealistic aspirations and actual implementation. Attempts to bridge this chasm have thus defined the historical scholarship on both institutions. In the case of the Soviet Union, historian Michael David-Fox argues for the field “to move beyond conceptual frameworks that segregate intentions and consequences, ideas and circumstances, political programs and social reality, above and below.” Rather, he advocates an examination of the “interrelationships” of these opposites.28 In the case of international organizations, historian Glenda Sluga similarly notes that “the history of internationalism travels along a characteristic narrative line from

utopia to disillusionment, but no more than the tales that can be told of imagined national communities.”29 This common tension between the ideal and the real opens up an opportunity to write a history of the Soviet encounter with world governance that highlights the convergence of the two projects in practice and elucidates their interrelationship.

In both contexts, the slippage and interplay between the ideal and the real reflected utopian ambitions adjusted to the world as it existed in the twentieth century. For instance, both universalist projects ironically became defenders of the nation as the pillar of world order. For its part, the USSR opposed more maximalist forms of world government and vigorously protected the principle of national sovereignty on the world stage.30 So did the UN. The world body consisted of an inelegant amalgam of great-power diplomacy and multilateral cooperation among nations glued together by institutions mimicking the features of the modern state on a world scale (civil service, branches of government, specialized ministries, etc.). It thus reflected ambitions for varying degrees of world governance mugged by the reality of national sovereignty and greatpower politics.31 Like the “really-existing” (as opposed to idealistic) socialism of the USSR, the UN’s brand of “really-existing” world governance accommodated lofty designs to the real world, emerging out of the collision of diverse visions for global integration with the exigencies of postwar international affairs.

32

Part I of this book is a chronological history that begins at the moment of this collision in the aftermath of the Second World War. As chapter 1 shows, the USSR rejected UNESCO and much of the rest of the UN system during the organization’s formative phase in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This boycott would prove a consequential mistake, allowing the West to shape the burgeoning international organizational system, and hence world governance, in its “really-existing” form. Chapter 2 turns to the years after Stalin’s death in 1953, when the USSR entered UNESCO as part of a broader recommitment to making a better world. Initiated by the new Soviet leader N. S. Khrushchev in the context of his foreign policy of

“peaceful coexistence,” Soviet accession to UNESCO reflected the optimistic faith in the superiority of the socialist system sweeping the country in the 1950s. Inspired by this faith, Soviet officials set out to demonstrate their system’s superiority within the walls of an organization claiming to represent a universal international community inclusive of both sides of the Cold War.

This utopian claim to universality, however, concealed the persistence of the Western biases ingrained in the UN before 1953. The source of these biases lay in the bureaucracies, or secretariats, of the world body and its agencies—the less glamorous core of the international organizational system that has been overlooked in favor of its representative organs in New York (the Security Council and General Assembly) and at its specialized agencies in Western Europe.33 The authority to implement the programs adopted by these representative organs lay in the international archipelago of UN secretariats scattered from Manhattan to Paris and Geneva. Just as the bureaucracy of a nation-state determines the implementation of legislation drawn up by elected officials, the secretariats of the UN system had considerable latitude to flesh out the resolutions passed by the community of nations. Put simply, the delegations of member states to different UN agencies showed up for debates or votes on proposals and then left for their missions. The international civil servants employed by UN secretariats then executed these proposals and kept the organization running from day to day. These bureaucrats acted as the carriers of the institutional memory and culture of the UN. This UN “deep state,” more than any other feature of the UN system, was the most concrete realization of world government achieved by twentieth-century internationalists.34

An analysis of the world body that centers this bureaucratic core reveals another similarity in the interplay of the ideal and the real in the Soviet and UN contexts. Viewed in this way, the UN resembled the USSR as an amalgamation of utopianism and bureaucracy, employing practices and structures of the modern state to realize universalist visions on an international scale. If the USSR amounted to what Michael David-Fox has called an “intelligentsia-statist

modernity,” the UN—and UNESCO in particular—were a much less coercive but nevertheless similar hybridization of intellectual messianism and bureaucracy.35 In the case of UNESCO, the utopian visions of men such as Otlet and Roerich became mired and muddled in the agency’s red tape. Staffed with a ragtag bunch of do-gooder pen-pushers with specialties in every imaginable field of education, science, or culture, the UNESCO Secretariat grounded fanciful intellectualism in the banalities of clericalism. Just as the Soviet intelligentsia represented what historian Martin Malia describes (drawing on Lev Trotsky and Milovan Djilas) as a “ ‘new class’ ” or “ ‘bureaucracy’ ” of “white-collar personnel” shorn of the “ ‘critical’ thought” of their prerevolutionary predecessors, UNESCO’s overwhelmingly Western corps of bureaucratic intellectuals at once personified and betrayed the utopianism of their internationalist forebears.36

This “new class” of bureaucrat-internationalists perpetuated the West’s advantage in UNESCO. As the third chapter makes clear, this remained the case even as the composition of UNESCO representative bodies (the UNESCO General Conference, or its equivalent of the UN General Assembly, and the UNESCO Executive Board, its veto-less version of the UN Security Council) changed as a consequence of the acceleration of decolonization in the 1960s. The induction of new countries as UNESCO member states eroded Western hegemony over these representative bodies. But contrary to the initial hopes of Soviet officials, the diminishment of Western power and the crystallization of a new bloc of nations from the “developing world” throughout the decade did not lead to a strengthening of the socialist bloc in the international organizational system. Instead, the bipolar world gave way to a pluralist one in which this system began to fracture, but only after Soviet internationalism had come to fully embrace UNESCO, and its method of world governance, as staples in its repertoire.

While the UN reflected the realities of the world it sought to govern, the world body nevertheless still bore the traces of its utopian blueprints, continuing to embody the promise and possibility of other forms of world unity not yet in existence. For this reason, anthropologists of international organizations have characterized them as “palaces of hope”—a designation these institutions have lived up to since their founding.37 In the West, the creation of the UN led to widespread anticipation in the early postwar years of a more powerful world state governing a peaceful world community.38 In contrast, the American Right interpreted this prospect as a threat, casting the UN as a proto-totalitarian menace harboring aspirations interchangeable with the Soviet drive for global communism. In 1964, for example, John Stormer used his anticommunist manifesto, NoneDare CallItTreason, to accuse UN Secretary-General U Thant of desiring a “one-world socialistic government financed by the United States” as the ultimate “synthesis” of the dialectic of history.3 9 A decade earlier, Usher L. Burdick, Republican congressman from North Dakota, declared that UNESCO in particular was “the most dastardly undertaking of all that the United Nations had theretofore contrived.” Under the guise of “spreading universal learning” for “mutual understanding,” he charged, the agency conspired to “create public opinion for the coming world government.”40

Unlike Stormer and Burdick, Soviet citizens who participated in UNESCO activities after 1954 did not see in the UN a communist proto-world state. They did, however, recognize the kernel of truth that gave rise to this outlandish conflation—the homologous utopian aspirations of the Soviet and UN projects for one world. As a result, these Soviet citizens embraced “really-existing” world governance because it extended to them a promise of world unity and peace consonant with the core utopian promise of the Soviet state. In this respect, the UN and USSR had in common not only their existence as embers of utopias past, but also their ability to act as sparks for utopias future. Of course, the Soviet state throughout its existence based its legitimacy on keeping this spark alive. From the 1917 revolution onward, it relied on what historian Mark Steinberg calls a

“utopian impulse” to mobilize its citizens to build communism.41 Embedded in “really-existing socialism,” this impulse would take on a new intensity just as the country joined UNESCO in the era of optimism and “romanticism” that saw the launch of Sputnik, the World Youth Festival, and the Cuban Revolution. As many Soviet citizens during this time looked to the country’s past to reignite the global emancipatory potential of the communist project, utopianism pervaded Soviet prophesies of “catching up and overtaking the USA,” the immanency of communism, and the spread of revolution in the decolonizing world.42

Likewise, the UN’s method of world governance presented its own brand of “romantic,” globally minded optimism, inviting Soviet citizens to work toward and imagine a brighter future. It engaged them in utopia as a means and an ends latent in the present.43 Just as Soviet socialism promised the possibility of working to end class conflict, UNESCO promised a way to work for a future without international conflict. And just as socialism promised what theorist Ruth Levitas has described as a “utopia of non-alienation” by means of “the collective action of the working class,” the UN agency offered universal belonging through world civic action.44

For the small but influential group of Soviet citizens active in the UN agency, UNESCO’s visions of peace and international community through enlightenment harmonized with the Soviet conception of historical evolution toward universal futurity. Like the “imaginary West” of the post-Stalin era, UNESCO’s ways of working for and imagining a better world became “reinterpreted” as part of the Soviet internationalist repertoire.45 Through the practice of “reallyexisting” world governance, Soviet UNESCO participants came to support the UN’s method of world governance and repurposed the world body for their own internationalist expression. The reality of the Cold War thus became imbued with practices, visions, and even transient realizations of one-world unity amid the divisions of the present.

Part II of this book turns its focus to these creative Soviet practices of “everyday” world governance.46 Organized thematically,

it tells the stories of members of the Soviet intelligentsia who participated in the three international publics formed by UNESCO. Ch apters 4 and 5 chronicle the lives of Soviet white-collar professionals who worked for world governance as public international civil servants in the UNESCO bureaucracy. Chapter 6 explores the thinking of Soviet scholars and intellectuals who contributed to the international public sphere of UNESCO gatherings and collaborative projects. Finally, chapter 7 illustrates UNESCO’s influence beyond the privileged elite who traveled abroad. It demonstrates how the international reading public of UNESCO publications encouraged Soviet readers deep inside the USSR to experiment with ideas of world governance, world civic duty, and international community.

The well-studied high diplomacy of Cold War confrontation in the UN has for too long overshadowed these day-to-day Soviet experiences of UN world governance. The UN system transformed the lives of a diverse selection of Soviet citizens, who encountered it not as neutral territory but as both a microcosm of world politics and a suigenerisuniverse. Whether engaging with UNESCO in-person or from afar, Soviet citizens navigated the agency as a social, cultural, and ideological complex suffused with an abundance of meanings and power relations.

If the abundance of meanings inspired in Soviet UNESCO participants hope for future world unity and peace, the organization’s complex power relations grounded them in the divisions of the day. Notwithstanding the frustrations arising from the latter, these patriotic Soviet citizens came to view the UN system as a flawed but valid vehicle for the expression of international solidarity and activism for peace and a better world. Coexisting and overlapping with the internationalism of the Soviet state, the UN’s brand of internationalism extended to Soviet internationalists a means of participating in a wider world while preserving their loyalties to the Soviet project. In the process, they lived Cold War reality in its oneworld development.47