CONCLUSION

12. The Bystander Myth and Responses to Violence

Notes

Index

Preface

I have long been puzzled about how the many millions of Germans who were neither enthusiastic supporters nor political opponents or direct victims of Nazism—what I have called the ‘muddled middle’— accommodated themselves to living within the Nazi dictatorship; and how, in the face of escalating violence, so many could become complicit in systemic racism, some even actively facilitating mass murder, and yet later claim they had been merely innocent bystanders. The development of the Third Reich, and the unleashing of a genocidal war, in which millions of civilians were wilfully murdered with the active participation of collaborators and auxiliaries in other countries across Europe, cannot be understood solely in terms of a chronology of Nazi policies, or the actions and reactions of key individuals, groups, and institutions in Germany, important as these are. We also have to understand how far wider groups became involved—and why so many people stood passively by, either unable or unwilling to intervene on the side of victims.

To do this, we need in some way to put together the social history of prewar Nazi Germany with the explosions of violence that began with territorial expansion in 1938 and the invasion of Poland in 1939, and escalated massively in the ‘war of annihilation’ on the Eastern Front from 1941. We have to understand what social changes occurred that made the extraordinary radicalization of violence possible even in the renowned ‘land of poets and thinkers’, and even before murderous violence was exported to the Eastern European borderlands that had so often witnessed bloody pogroms in preceding decades. In short: we need to understand how, in their daily lives, vast numbers of Germans began to discriminate against

‘non-Aryan’ compatriots; and what were the longer-term implications for ignoring, condoning, or facilitating genocide beyond the borders of the Reich.

By exploring individual responses to common challenges, I have sought in this book to evaluate the processes through which people could variously become, to widely differing degrees, complicit in the murderous consequences of Nazi rule. Viewed in this way, it becomes clear that significant changes in German society through the Nazi period are more complex, more messy, than some accounts of the Third Reich would suggest. The long-standing view of ‘German society’ as some monolithic mass subjected to totalitarian rule is clearly inadequate; but so too are summary notions of a ‘perpetrator society’ (Tätergesellschaft), or a ‘consensual dictatorship’ (Konsensdiktatur), or ‘implicated subjects’ that have variously gained in popularity in recent decades. Similarly, appeals to notions such as endemic antisemitism, or obedience to authority, risk drifting off into a disembodied history of ideas, or typecasting ‘the Germans’ with some supposedly persisting characteristics.

I have tried in this book to understand, through personal accounts, the gradual and at first seemingly minimal shifts in people’s behaviours, perceptions, and social relationships within Germany during the peacetime years of Hitler’s rule; and then the rapid, radical reorientation of attitudes and actions as the Reich expanded, and during the genocidal war that Germany unleashed on Europe and the world. Although focussing on individual experiences in selected locations, and exploring the development of complicity in the conflagration of crimes that we call the Holocaust, I have sought to develop a more broadly applicable argument about the conditions for widespread passivity in face of unspeakable violence.

These are huge topics, posing questions that people have grappled with for decades; this horrific history of brutality and mass murder remains in fundamental respects utterly incomprehensible. Yet we have to try to make sense of it in whatever ways we can, in order to develop a fuller understanding of the multiple ways in which the reprehensible and unthinkable ultimately became possible. It seemed to me that the vexed issue of bystanding—of standing

passively by, failing to intervene and assist victims, effectively condoning violence by not standing up to condemn it, even sustaining the perpetrator side by appearing to support public demonstrations of violence—required far more systematic analysis than the various loose uses of the term had so far suggested. It is in principle impossible to try to remain neutral under conditions of persistent, state-sponsored violence. The question then becomes one of why so many people choose to act in one way rather than another, and under what conditions people’s perceptions and behaviour shift, with what (often ultimately fatal) consequences for others.

The argument is developed in this book with respect to German society and the Holocaust. But there are significant wider implications. Passivity, indifference, choosing to ignore the fates of others are not historical givens; they are actively produced and fostered under certain conditions and vary with historical circumstances. In face of persisting discrimination and persecution, and repeated eruptions of collective violence, understanding the production of what I have called a ‘bystander society’ is of continuing and far wider relevance.

Acknowledgements

The research for this book was based in a collaborative research project sponsored by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), with additional funding for impact activities very generously provided by the Pears Foundation. I would like to thank both the AHRC and Trevor Pears for their crucial financial support for the project. I would also particularly like to thank my close academic collaborators for their invaluable support and intellectual stimulation over the course of the research and writing of this book: Stephanie Bird, Stefanie Rauch, Christoph Thonfeld, and Bas Willems. Writing a book is always necessarily a somewhat isolated endeavour, but this was made infinitely more enjoyable by regular interactions with members of the research group, always appropriately both critical and constructive in their comments.

Impact activities relating to the wider collaborative project were greatly enhanced by working on the production of short films with Graham Riach, to whom I am extremely grateful for his seemingly unshakeable good humour—whether tramping around death sites in Lithuania, tracing Nazism through the streets of Berlin, or dealing with rambling academic discussions in my office and on Zoom. Bringing the project to the attention of wider audiences was ably facilitated by our Impact Fellow, Dan Edmonds, also generously funded by the Pears Foundation; and by cooperation with colleagues from the Centre for Holocaust Education in the UCL Institute of Education, particularly Helen McCord, Andy Pearce, and Corey Soper, who assisted in outreach to teachers and schools. Catherine Stokes of the UCL IAS provided invaluable administrative support to our group throughout. I would also like to take this opportunity to

remember the late documentary filmmaker Luke Holland, whose recorded interviews with people who were involved in or close witnesses to the Holocaust played a significant role in our wider project, even though I have not drawn on his material in this book. His commitment and continuing engagement with key issues around those ‘on the side of the perpetrators’ was much appreciated, and his archival legacy will, I hope, encourage and facilitate far more research in this area.

The ideas in this book have been developed and presented in a number of versions over the years. Early stimulation for my own approach came from the 2015 conference on Bystanders organized by Christina Morina and Krijn Thijs in Amsterdam, and I am very glad now to be able to continue the discussion with Christina Morina in a new collaborative project funded by the AHRC and the German Research Foundation (DFG) with a broader pan-European focus. Further impetus for the project came from being asked to deliver a keynote at the Nottingham conference on Privacy and Private Lives in Nazi Germany, organized by Elizabeth Harvey, Johannes Hürter, Maiken Umbach, and Andreas Wirsching. I am also grateful to colleagues at Yad Vashem for their valuable comments on the occasion of my David Bankier Memorial Lecture in 2018. I received helpful input to my thinking specifically on Kristallnacht at the conference held at the University of Southern California to mark the anniversary of this event in November 2018. A further location where I was able to benefit in person from reactions to my evolving ideas was at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver in March 2020; I greatly enjoyed that occasion and was then fortunate to catch virtually the last plane out before airports closed for travel.

Much of my writing took place during the Covid pandemic from spring 2020, with repeated lockdowns. There were some unexpectedly beneficial aspects of this otherwise horrendous worldwide public health crisis. Interacting on screen with colleagues near and far, across the world, in workshops, seminars, and conferences, was a constant source of pleasure, made possible by the wonders of internet technology, even if somewhat constrained by circumstances. I would particularly like to thank members of the

informal regular discussion group on History and Psychoanalysis, with whom I have had so many stimulating and invigorating discussions over the years, first in person and more recently on Zoom; they have sustained this project in many ways. I have also benefitted from the input of members of a seminar group wonderfully hosted by Irene Kacandes that arose from a cancelled Lessons and Legacies conference. The persistent travel restrictions affected the book in less beneficial ways too. Most obviously, the pandemic put a sudden end to further archival research and site visits, and for long stretches of time even access to secondary materials in local libraries was severely restricted. Not least, as for so many other people, family health issues were often severely distracting. Writing was therefore a far more disjointed process than it might otherwise have been.

I am immensely grateful to Jürgen Matthäus for his careful reading and perceptive comments on a full draft of the manuscript, as well as assistance with obtaining images from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). Through coediting and coauthoring with him on another project, I had already come to appreciate his incredible expertise, as well as his sheer good humour, efficiency, and reliability. I would also like to extend particular thanks to David Silberklang for his expert and helpful comments on one of the later chapters, and his assistance with obtaining key photographs from the Yad Vashem archive. Needless to say, I take full responsibility for any remaining errors and infelicities.

My particular thanks go to my agent, Emma Parry, for her enduring encouragement; this means a lot to me. And I am extremely grateful to Tim Bent of Oxford University Press for what he nicely called his ‘meddlesome’ comments in the final stages of editing the manuscript; I really appreciate his close engagement with the text, even if I have neither accepted all his suggestions for stylistic changes nor satisfied his repeated quest for greater statistical quantification in an area that I see as intrinsically characterized by fluidity, ambiguity, and ambivalence.

As always, members of my family have variously sustained, supported, and distracted me throughout the writing of this book. Conrad, Erica, and Carl, and their respective partners, have continued to be wonderful companions in their very different ways, while particular mention should be made of the growing band of lifeenhancing grandchildren on both sides of the Atlantic. Julian has, as ever, unfailingly accompanied me throughout the research and writing, helping me to explore disagreeable places and uncomfortable material, while abandoning any hope that I might one day turn to work on a more congenial subject.

Mary Fulbrook

London, 12 February 2023

Introduction

Bystanders and Collective Violence

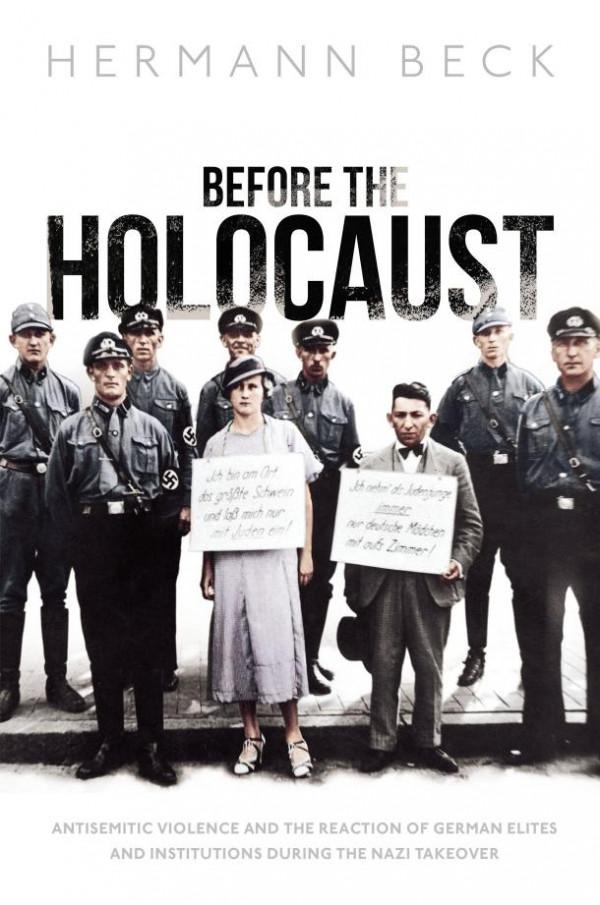

In April 1933, just over two months after Hitler had been appointed chancellor of Germany, a prominent lawyer was forced to parade through the streets of Munich with his clothes in tatters, bearing a placard with the words ‘This filthy Jew shall no longer stand in judgement over us!’ A young businesswoman whom I shall call ‘Klara’ happened to be passing by when she witnessed this public humiliation. Hardly able to believe her eyes, she was overwhelmed by a combination of horror and compassion. She tried to push her way through the crowds in the hope of being able to help in some way—but to no effect. Nor was she able to gain assistance from other bystanders: neither ‘Aryans’ nor Jewish Germans were willing to intervene. Eventually the lawyer was taken to the public square by the railway station, where he was repeatedly kicked on the ground ‘for the pleasure of the gaping masses,’ before finally being allowed to go home. This incident shocked Klara so much that she wrote vividly about it in an essay penned some six years later, in 1939.1

Not only this lawyer, whose name we do not know, but other Jews too were subject to abuse and victimization following Hitler’s rise to power; when Klara ran to get help from Jewish friends, she found that one of them, a rabbi, had himself been arrested. But why did non-Jewish Germans not raise their voices in protest? Why did so many of them watch, whether silently or even in apparent approval? And—the question so many of us ask ourselves in the aftermath of the Holocaust and in the face of violence to this day—what would we have done in these circumstances?

The passivity of bystanders deeply affected Klara, who saw herself as a patriotic German. Her brother had died in active service in the Great War, and she had herself nursed wounded soldiers. She was full of ‘national pride’, coming from a family that had lived in Germany for generations, able to trace ancestors back into the seventeenth century.2 Yet this incident challenged all sense of what it meant to be German. ‘What hurts is not the fact that I witnessed this, but rather that my compatriots, whom I love so much, for whom I joyously gave all that I am, that they allowed this, that is what hurts so unspeakably! I am ashamed for them.’ The fact that her compatriots now supported a regime claiming that Jews were ‘parasites’ on the German people was for Klara ‘far harder to struggle with than the humiliations and injuries that we had to take in our stride’.

It was the apparently enthusiastic and supportive reactions of bystanders, the crowds who gathered to watch the public degradation of the Jewish lawyer, and the fundamental redefinition of what it meant to be German, that caused Klara, a patriotic German Jew, so much distress.3

Taking action, whether by assisting victims or alerting authorities, is widely encouraged in liberal democratic societies. The ‘bystander’—a term that does not translate well, with no direct German equivalent —is generally urged not to remain passive, but rather to ‘stand up’ for what is right—whether by speaking out against bullying; challenging sexist, racist, or homophobic language and behaviour; calling for outside assistance; or providing witness statements to help bring perpetrators to account.4 ‘Standing up’ is often framed in terms of individual courage. Such an approach may be necessary; but the fundamental message of this book is that it is also insufficient. What might be morally laudable stance in a liberal, democratic regime may be, in other circumstances, both ineffective and potentially suicidal.

To understand bystanding under conditions of persisting violence sponsored by those in power, we have to understand more than elements of individual courage or small group psychology. We also,

with respect specifically to Nazi Germany, have to go beyond simplistic assumptions about supposed ‘national character’ or longlasting traditions of antisemitism of obedience to authority. Bystanding is socially constructed and can change over time.

This book argues that certain types of social relations and political conditions produce a greater likelihood of widespread passivity in face of collective violence. In what I call a ‘bystander society’, fewer people are likely to stand up and act on ‘the courage of their convictions’ in face of violence against those ousted from the community and vilified as ‘others’.

In Nazi Germany, as this book reveals, these conditions were historically produced, rather than pre-existent, in a process that developed over several years. It was not intrinsically a ‘perpetrator society’, but over time it became a society in which widespread conformity produced growing complicity in establishing the preconditions for genocide. In wartime Eastern Europe, the more rapid and ever more radical dynamics of violence mean that active involvement in perpetration, as well as complicity, passivity, and resistance, need to be examined in a different way. By exploring the development in more detail through personal accounts, it becomes clear that experiences in the prewar years played a significant role both in the facilitation of ever more radical acts of perpetration during wartime and in wider responses to atrocities among both Germans and local populations.

To embark on this enquiry in historical detail, we need first to clarify some wider, theoretical issues around the concept of bystanders and then also consider some more specific questions about the nature of German society and varying degrees of responsibility for the persecution and murder of European Jews.

First, the more abstract theoretical issues. Inactivity in the face of violence is in itself a form of action, effectively condoning or even appearing to support the perpetrators, and certainly not halting or hindering the violence. Certainly some of the German terms used— Zuschauer (onlookers), even more so Gaffer or Schaulustiger (gawper, rubbernecker)—imply a degree of fascination or enjoyment in watching a spectacle involving violence. Perhaps equally frequent,

though, is not so much gazing at but rather looking away from violence (Wegschauer): pretending not to have seen, not to have registered what is going on, in order to avoid becoming uncomfortable or involved. It is simply easier to have ‘not known’, thereby not having to face any questions of guilt about an outcome that might potentially have been averted.

Passivity therefore raises the question of whether ‘bystanders’ also bear some responsibility for the outcomes of violence, and whether indeed there can be such a thing as the proverbial ‘innocent bystander’. It is perhaps easy enough to pose this question in circumstances where help—police or some kind of official authority may be readily to hand.

People of course vary in their capacity for action, and distinctions have to be made. On one view, the notion of a ‘moral bystander’, to use the philosopher Ernesto Verdeja’s term, allows us to distinguish between, on the one hand, those who do not fully comprehend what is happening or are powerless to act effectively and, on the other, those who are, as Verdeja put it, ‘in a position to intercede and consequently alter the direction of events, and yet fail to act’.5 This approach highlights two crucial features for the interpretation of bystander behaviours: appropriate awareness of what it is that is going on, and the degree to which a person is able to intervene effectively. A child, for example, is less likely to be able to assess the situation or exert effective power and authority than an adult; parents or caregivers may feel it too risky to intervene in a fight between others without putting their own children at risk; a passerby may witness a police officer holding down a man by kneeling on his windpipe, despite protestations that he could not breathe, and wonder whether, since this was an incident where police were already involved, it would really be right to intervene. People happening to witness such scenes of violence could readily be labelled ‘innocent bystanders’, who cannot be held personally responsible for physical injuries or fatal outcomes. Yet these examples also underline the fact that ‘bystanders’ cannot be considered purely at an individual level, without taking into account

the wider context. As the last example indicates, wearing a uniform does not necessarily demonstrate that certain actions are acceptable; and a bystander’s video evidence of the incident in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020 in which a police officer, Derek Chauvin, held his knee on the neck of the dying George Floyd, proved crucial in the trial and murder conviction of Chauvin.6 Circumstances matter.

Accounts of bystanders generally focus on the immediate participants and dynamics of specific incidents of violence, assuming that chance witnesses can at least potentially come to the assistance of victims, whether directly or indirectly. The external environment of the conflict is taken as in some sense neutral, a regime or system committed to upholding ‘law and order’. Even when it is a police officer exerting unwarranted violence, as in the Chauvin case, it is assumed that he can be brought to account. In principle, then, the bystander should be able to intervene in some way.

But bystander support for victims is a very different matter when it is the regime itself that is at the root of the violence: when it is the authorities who have instigated or are actively involved in violence, or wilfully refrain from intervening on behalf of victims. The conundrum people faced in in Nazi Germany arose from the combination of violence actively instigated or sanctioned by the regime and wider, systemic and structural violence that seeped through society in both policy-related and informal ways.

The context is not neutral and needs to be taken into account more explicitly. This is particularly the case when a regime based on violence itself persists over a lengthy period of time. The dynamics of the system change, and people themselves are changed by accommodating themselves to living within such a state. Perceptions change, too, affecting how situations of violence are interpreted and acted upon (or not).

Awareness and capacity for effective action are therefore not just questions of what individuals ‘see’ or their capacity for effective action, as in the somewhat abstract formulations of philosophers, but also of the wider cultural frameworks within which witnesses interpret what they think they are seeing, and the social and political

conditions in which they assess what action they think might be appropriate or effective—or too risky. Some of this may be a matter of prevalent norms, as in unwillingness to speak out in circles where racist, sexist, or homophobic comments are seen as acceptable, or made light of when criticized (as in the dismissive notion of ‘just banter’ or ‘locker room talk’).7 Similarly, the view of victims as in some way to be feared as well as vilified may be more widely shared. Given unequal power relations and a sense that speaking up is futile, critics may be unwilling to share their disquiet, and this is particularly the case if these norms are officially propagated and publicly enforced. So the wider context of both perception and choice of action matters enormously. We have therefore to explore the conditions under which people believe that violent action against particular groups may be justifiable, proportionate, even desirable; or feel that there is little point in speaking up. We also have to understand, by contrast, the circumstances in which individuals feel it necessary or even possible to dispute dominant interpretations. Challenging violence under dictatorial and repressive conditions is a quite different matter from reporting a fight on the street or confronting playground bullying in a democracy, however terrifying the violence may be for unwilling victims in such cases.

The meaning of ‘bystanding’ depends on context and this context can almost by definition be only temporary. People may be ‘neutral’ bystanders when they first witness an event: but within moments, neutrality will no longer be possible, as onlookers variously move in the directly opposite directions of either condoning or condemning the violence, and with differing degrees of activity in each case: indicating sympathy for one side or the other, more actively engaging in support for one side or the other, calling for help, or participating in and benefitting from perpetration. Building in the time dimension, it can even extend to the ambiguous double meaning suggested by former US president Donald Trump in the first presidential election debate of September 2020. When challenged on his refusal to condemn the violent actions of white supremacists and racists, including a right-wing, anti-immigrant group called the Proud

Boys, Trump exhorted the Proud Boys to ‘stand back and stand by’, since ‘somebody’s got to do something about antifa and the left’. ‘Standing by’ was clearly here intended as an injunction to remain quiet for the time being, but to be prepared for future action when conditions were right.8 And, indeed, Trump then unleashed antidemocratic violence by inciting supporters to march on the Capitol on 6 January 2021 to disrupt the formal adoption as president of Joe Biden, the legitimate winner of the election that Trump falsely claimed was ‘stolen’. In the United States, ultimately, democratic institutions and authorities prevailed in 2021, and despite all Trump’s prevarications Biden duly became president. Even so, election ‘denialism’ continued to be a strong force in American politics.

Conditions were of course quite different in Germany under Nazi rule. We know a great deal about Hitler, the Nazi party and movement, and official policies in the Third Reich; victims and survivors have left painful traces and searing accounts with agonizing details about their persecution. But what about members of the wider population? We have a far less precise view of the ways in which those who were not themselves directly perpetrators or victims accommodated themselves and participated in an evolving system of collective violence, or the extent to which members of mainstream society were themselves in part responsible for, or complicit in, the ultimately murderous outcomes of Nazi persecution. After German defeat in 1945, the myth of the ‘innocent bystander’ was born. Refusing to accept the accusation of indifference to the fate of Jewish fellow citizens, people claimed they had been either ignorant or impotent; they would bear no responsibility for what they had allowed to happen in their midst, let alone concede that they had themselves played a significant part in unfolding processes of discrimination and exclusion, the essential precursors to genocide. Was the notion of having been ‘an innocent bystander’ merely a convenient postwar myth?

It is abundantly clear that violence against Jews—as Klara Rosenthal and many others witnessed in the very first months of Nazi rule— was both instigated and sanctioned by the Nazi regime. But it was

the reactions of the wider population—whether enthusiastic or passive—that shocked Klara most of all. It was the response of bystanders—or rather their non-response, their failure to act—that allowed the public humiliation of the prominent Munich lawyer to take place. Although Jews and socialists, often combined in the catch-all pejorative concept of ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’, had been vilified as the ‘enemy within’ at least since defeat in the Great War, Jewish Germans were an integral part of German society as indeed the social status of the Munich lawyer illustrated.

To cast Germans of Jewish descent as ‘other’ required first of all, during the period up to 1938, an active process of social segregation. It should be emphasized, however, that the ultimate goal of Nazi ideology was not to return to any kind of preemancipation status for Jews, nor to bring about a form of segregation along the lines practised in the United States, but rather something far more radical: to achieve an ill-defined, unprecedented, and irreversible aim, the complete removal of ‘the Jewish race’ and all that ‘the Jew’ supposedly stood for; not merely to imagine, but actually to achieve, what has been called a ‘world without Jews’.9 This Nazi ambition took a variety of practical forms on the tangled route to the policy of extermination that the Nazis conceived of as a ‘final solution’ for the ‘greater good’, driven by what Saul Friedländer terms an ideology of ‘redemptive antisemitism’—something on a wholly different and infinitely more murderous scale than the segregation and subordination of an allegedly ‘inferior’ race.10 In the meantime, however, as far as the wider population in Germany was concerned, this first entailed a process of classifying, stigmatizing, and separating out those who were to be targeted—essential in a society where people of Jewish descent were often indistinguishable from compatriots of other backgrounds. The process of segregation transformed the character of social relations and conceptions of identity within Germany in ways that would subsequently facilitate growing complicity, widespread involvement in perpetration, and a capacity to turn a blind eye to mass murder during the war.

This period raises questions about the ways in which conformity can, over time, effectively turn into complicity. Social segregation and the racialization of identities were, crucially, not only a matter of official policies and practices but also involved the everyday actions and attitudes of the wider population. Following decades of increasing assimilation and integration, Germans of Jewish descent, whether or not they were of the Jewish faith, were from 1933 singled out as in some way ‘racially’ different and now there was no possibility of seeing conversion to Christianity as a ‘solution’. Over the course of just a few years, the social dynamics of exclusion consisted in not only the imposition of official policies but also the informal actions of ordinary people in everyday life. Jewish Germans were cast out, losing social contacts and personal friendships as well as citizenship rights, livelihoods, and property; during the peacetime years, even those who escaped direct physical violence suffered what Marion Kaplan, following Orlando Patterson, has called a form of ‘social death’.11 These processes not only created the preconditions for the isolation of victims but also for growing complicity among ‘Aryans’, paving the way for involvement in the ever more radical persecution and perpetration that followed. Once Nazi Germany had unleashed an expansionist and ultimately genocidal war, mass deportations and organized extermination unfolded across Europe; around 6 million Jews, and many millions of other civilians, lost their lives as a consequence of the fatal combination of Nazi initiatives and differing forms of local complicity and collaboration.

Within Germany, the story may readily be—and has already often been—recounted in terms of Nazi policies and Jewish experiences; it is far less easy to understand the significance of changes in the wider society out of which people of Jewish descent were being ripped. Yet in this process, non-Jewish Germans too were changing, shifting their perceptions of themselves and others, and adapting their behaviours and expressed attitudes. Later, the vast majority of those who had been caught up in the violence, willingly or otherwise, would try to distance themselves, claiming variously that

they had ‘known nothing about it’ or had been powerless to act differently.

The role of so-called ordinary Germans was and remains highly controversial. Some commentators and scholars have fallen prey to the temptation to homogenize ‘society’, as though all Germans were in some way similar, even that some persisting underlying ‘mentality’ could be identified. The role of supposedly persisting traditions of antisemitism has been highlighted as a key causal factor. Others, however, have tried to present a more differentiated picture, using the adjective ‘ordinary’ only in relation to specific groups and exploring the reasons for their behaviours within particular historical contexts, which may have had more to do with peer group pressure than ideological motivations.12 Similarly, the radical changes in outlooks and behaviours that were brought about by socialization under Nazism and exposure to brutality in wartime conditions have been emphasized as more important than any supposedly longerterm features of ‘German society’ or mentalities. Even so, there has been a widespread tendency to use terms such as German ‘majority society’ (Mehrheitsgesellschaft) or to talk about Germany as a ‘perpetrator society’ (Tätergesellschaft).

The pre-eminent Holocaust scholar Raul Hilberg explicitly brought to attention the now familiar triad of ‘perpetrators, victims and bystanders’.13 But this somehow suggests discrete actors, leaving out the wider environment within which violent incidents occur, and which crucially shapes the actors’ perceptions, capacity for action, and likely outcomes in any given situation. And classically, Hilberg claimed that in Germany ‘the difference between perpetrators and bystanders was least pronounced; in fact it was not supposed to exist’.14 He was certainly right about the latter point; but, as explored in this book, I am not so sure about the former. Other scholars, in critiquing blanket notions of a ‘perpetrator society’, want to distinguish between ‘acts of murder (or supportive actions directly leading to murder) and social behaviour that goes no further than contributing to social exclusion’.15 This distinction raises serious questions, however, about the longer-term implications of

behavioural conformity ‘contributing to social exclusion’, which may indeed at first be seen by those engaging in it (although less so by their victims) as in some sense sufficiently harmless to warrant the phrase ‘goes no further than’. Ultimately, we have to find some means of making distinctions that allow us to explore the complexity of varieties and degrees of involvement and responsibility, if not outright culpability.

So this remains a highly contentious field, in which not only the concepts but also the sources require intensive and sensitive evaluation.

Klara’s recollections, at the start of this chapter, are taken from a rich archive of personal accounts that provide fascinating insights into the emotional and psychological landscapes of the 1930s, with details of social interactions that would later often be forgotten or overwhelmed by the horrors of war and genocide. In 1939, three Harvard professors were keen to explore what was going on in Nazi Germany—not at the level of political events and policy developments, but rather in terms of everyday life. The three— Gordon Allport, Sydney B. Fay, and Edward Y. Hartshorne— announced a competition for essays to be written under the title ‘My life in Germany before and after January 30, 1933’ (the date Hitler was appointed chancellor), and advertised this competition widely in German-speaking and exile newspapers. They offered a first prize of $500—an attractive sum at that time for anyone, and particularly for penniless refugees or impecunious exiles, although not all essay writers fell into these categories. Even the smallest prizes of just a few dollars could make an enormous difference to someone on the run from Nazi persecution. But the aim of the competition, to understand the massive social and psychological transformations occurring in Nazi Germany, was important in principle even for those not in need of any prize money—including those relatively few respondents who recounted their experiences in order to praise aspects of Nazism.

The three professors came from different disciplines: Allport was a psychologist interested in personality traits; Fay was a historian

who had written a significant book on the causes of the First World War, as well as a classic work on the rise of Brandenburg-Prussia; Hartshorne, who was married to Fay’s daughter, was a young sociologist who had in the mid-1930s spent a year in Germany undertaking research for his doctoral dissertation on German universities under National Socialism. They were united in their determination to understand more deeply what was going on in Nazi Germany and felt that lengthy accounts of personal experiences would give them a better understanding of the impact on people living under Nazi rule than could any observations by diplomats, journalists, or foreign travellers, fascinating though these too might be as external perceptions of changes in Germany under Nazi rule.16

More than 250 essays were submitted to the Harvard competition, written from the late summer of 1939, through the first wartime winter, to the spring of 1940. Nearly two-thirds were written by exiles and refugees living in the United States (155, of whom 96 lived in New York City); roughly one in eight (31) came from the UK; another twenty from Palestine; thirteen from Switzerland; essays also came in from Shanghai, South America, Australia, South Africa, Japan, and a few more from European countries including France, Belgium, Holland, and Sweden.17 Most of the essays were written in German, but a few were penned in the somewhat awkward phrasing of non-native English, producing a slightly more stilted style on occasion.18

A predominance of educated professionals among the authors was to be expected. But the urgency of a desire to communicate experiences and the hope of winning a prize led more people from humble backgrounds to write than might have been predicted. Moreover, although the essays mainly reflected the experiences of Jewish men and women, the collection also includes accounts by non-Jewish individuals who were variously supportive or critical of the regime, as well as individuals whom Nazis defined as of ‘mixed’ descent, and ‘Aryans’ in ‘mixed’ relationships, whose experiences have to date been generally less well explored.19 They were not among the directly persecuted, the primary victims and targets of

Nazi policies; nor were they necessarily active resisters, dissidents, or opponents of Nazism. They were in many ways astute observers of what had been going on in their name, and some had become increasingly uncomfortable with their forcible incorporation into the Nazi ‘national community’ (Volksgemeinschaft). Some émigrés had chosen to leave Germany because of their personal relationships with Jewish loved ones; others left out of a more general sense of discomfort, unwilling to expose themselves or their children to the complicity that they felt living under Nazism entailed. Some were fortunate in having the resources and necessary connections to get out; most were reliant on a combination of luck, determination, and the goodwill of others.

But of course the overwhelming majority of Germans, critical or otherwise, Jewish or gentile, did not leave the Reich—and while German gentiles were mobilized for war, Germans of Jewish descent who had not got out in time were eventually faced with deportation, most of them to their deaths. So the accounts of these predominantly critical essay writers, written at a pivotal moment before Europe was plunged into war and mass murder, have to be supplemented by other sources. Even so, their perceptions of the prewar years are invaluable in trying to understand changing aspects of life under Nazism before the outbreak of war and genocide.

The essays in the Harvard collection provide insights into a diversity of experiences from a range of perspectives, and from different areas across the Reich or territories it later annexed or occupied. Many of them are particularly perceptive about the ways in which the racialization of identity was effected in everyday life. They record how people with whom they had previously interacted socially started to look away, to distance themselves. Those not excluded from the ‘national community’ were increasingly drawn into playing roles that made them complicit in Nazism, effectively sustaining and assisting the escalation of persecution. The essay writers were only too well aware of how others were treating them—including the many who would later claim they had ‘known nothing about it’ and were merely innocent bystanders.

There is a further advantage offered by such material. Opinion reports and surveys, whether by the regime’s own organizations or by opposition groups such as the Social Democratic Party in exile, are of course invaluable sources. But such sources only provide snapshots, with evidence of specific attitudes on particular issues at certain moments; and the individuals whose views are recorded generally remain anonymous, simply seen as representatives of their class, gender, religion, or region.20 This mapping of wider patterns is important.21 But to grasp the transformation of society in Nazi Germany, we need also to explore emotional connections, social relations, and sense of identity and community. For this, personal accounts of experiences over time are invaluable in giving some access to subjectivities and changing relationships with others.

The life stories collected by the Harvard researchers reveal in greater depth the conflicting attitudes and degrees of ambivalence, as well as contradictions between views and behaviours, speech, and actions of individuals, over a period of time. They offer a more rounded picture of the ways in which people led lives marked by conflicting priorities and emotions, and engaged in compromises. They bring together wider analyses of social and political structures with the inner feelings and actions of individuals.

Of course, personal accounts do not tell the whole story, and a worm’s-eye view can provide only a limited perspective from a specific location. But there is more than this affecting the account. Autobiographical memory is always characterized by selective recollection, amnesia, or silencing. Some moments are recalled vividly; long periods are glossed over or sink into obscurity; key incidents are omitted, and others overemphasized. The slant given to the past varies with the context of later telling. Experiences when young—aspiring towards a still-open future—are often cast in a nostalgic light. Each individual has not only specific events to relate but also a wider ‘story’ to tell. In portraying how they dealt with particular challenges, people construct an image of their own selves (resilient, heroic, victimized, and so on). Self-representations are shaped by wider environments and the vocabulary of different

communities, as well as the specific context in which they are produced. In the case of the Harvard essay prize collection, at least some of the essay writers may, in desiring to be a winner, have sought to enhance the literary merits of their narratives—an effort more evident in some essays than others. Yet they were all clearly impelled to convey some sense of their intrinsically dramatic and indeed life-changing experiences. No collection of autobiographical accounts will tell us ‘how it really was’, and they always have to be read as texts produced in a particular place for a particular purpose. They are nevertheless invaluable in illuminating significant subjective experiences and the quality of social relationships—and this before knowledge of the ‘catastrophe’, the Shoah or Holocaust, that was about to engulf European Jews and countless others.

The overwhelming majority of these essay writers were victims or critics of Nazism, while a handful of essays praise what they see as the good points about Nazi Germany. They stand in some contrast, then, to the essays collected by Theodore Abel in 1934, whose appeal for personal accounts was specifically targeted at people who had become Nazi enthusiasts relatively early on.22 The writers of the Harvard essays in 1939–1940 are predominantly either marginalized or self-marginalizing figures. But if read appropriately, this perspective from the margins of mainstream society constitutes a distinctive strength of the material: the authors are all the more acutely aware of the responses of other Germans who were going along with the tide. Their experiences and perceptions illuminate the social processes through which, in the micro-negotiations of everyday life, other people—those often seen simply as ‘neutral bystanders’—in fact played an active role in progressively redefining what it meant to be ‘German’ and stigmatizing those who were to be outcast. The marginalized are, in a sense, the best barometer of the historical significance of bystander passivity, conformity, and growing complicity.

Composing their accounts just as the war was starting, these writers did not yet know the horrific events that would follow. They had some intimations of what was brewing already in the winter of

1939–1940, but most had little inkling of the ‘euthanasia’ programme that had already started and would continue informally even after its official termination in 1941, or the savage ‘resettlement’ policies, mass terror, and murders that had begun to take place following the invasion of Poland in September 1939. It is highly unlikely that they would even be able to imagine the sheer magnitude of the genocide that would erupt from 1941: the ‘Holocaust by bullets’, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, would kill around 2 million Jews, as well as Roma (‘gypsies’), the mentally ill and disabled, and those designated as ‘partisans’, across the Eastern Front; perhaps 2.5 million Jews would be killed in the dedicated extermination camps that started to come into operation from December 1941, reaching a murderous peak in 1942–1943 and continuing in Auschwitz through 1944; another million would die in the extensive system of ghettos, concentration camps and forced labour camps, and the death marches of 1944–1945; these essay writers, in short, did not yet know what would be the horrendous character and scale of the Nazi ‘Final Solution’.23 Any personal account written after these events would inevitably be overwhelmed by their shadow, casting a quite different light on their prehistory. This was not the case for the Harvard essay writers.

For the writers of the Harvard competition essays in 1939–1940, the most significant and worst imaginable changes in their lives had already taken place before 1939: the dropping of friendships; the loss of occupations and livelihoods; the violence and terror of Kristallnacht in November 1938 and incarceration in concentration camps; the suicides, departures, separations from family and friends; the loss of any chance of a civilized life in Germany or Austria, previously such renowned centres of civilization. Precisely because of their limited time horizon, the essay writers have no benefit of hindsight; they do not know how these momentous developments in their lives within Germany were paving the way for organized mass murder across Europe; they paint an all the more detailed picture of social changes in the six prewar years of Nazi rule, from 1933 to 1939, without framing their stories in light of

postwar interpretations, or feeling that everyday experiences before the war were in some way less significant or overshadowed by the mass death and destruction that followed. Their autobiographical accounts are therefore an extraordinary resource for gaining a deeper understanding of how German conceptions of themselves and their relationships with others were changing under Nazi rule during the prewar years. They can help us understand the multiple— and at the time seemingly trivial—ways in which conformity with the Nazi regime could, over time, shift into complicity with racism, paving the way for mass murder.

Curiously, the Harvard professors barely used the essays. There is one significant piece by Hartshorne, essentially more of a pamphlet than a book, in which he selects a few accounts to illustrate the experiences of ‘Aryans’ of different generations, genders, and classes. This essay is more typological than explanatory, but Hartshorne’s concern to explore the experiences of non-Jewish Germans reveals how far they were prepared to compromise.24 Hartshorne was never able to follow up at greater length on these preliminary observations. During the war, he first worked in the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the Psychological Warfare Branch and then returned to Germany during the last months of the war, working in the Psychological Warfare Division. Following German defeat, he took over tasks relating to denazification and the refounding of German universities, building on his academic expertise in this area. In late August 1946, while he was engaged in investigating reports of former Nazis still active in German universities, he was fatally shot in the head by an individual in an overtaking jeep on the autobahn from Munich to Nuremberg. There has been speculation that Hartshorne’s assassination was related to his work in uncovering the tracks of former Nazis, or American attempts to suppress exposure of the ‘ratline’ through which former Nazis were being assisted in escaping via Italy to South America, as part of the American fight against communism; but the evidence remains inconclusive.25