Acknowledgments

This book has been years in the making, and I am so grateful to the many people and institutions that helped me along the way. I became an independent scholar in 2006, when I transitioned from tenured professor to freelance historian. By 2009, I began germinating the idea for this book. The individuals and funders who supported my work as an independent scholar, recognizing the particular challenges of that status, hold a special place in my heart, and I am particularly thankful for their generosity and sustenance.

Three funders provided crucial support with year-long fellowships during which I wrote three of the case studies of this book: the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the American Council of Learned Societies. I am grateful to the Huntington Library for several short-term fellowships, to the UCLA Center for the Study of Women for a steady succession of Tillie Olsen Grants, and to Bill Deverell and Wade Graham of the LA County Almanac project for allocating funds to me to collect 2010 data on LA. Additional thanks to the National Endowment for the Humanities for a grant to the USC Libraries to help make my LA County data accessible to the public, and I am grateful to Andy Rutkowski, Deborah Holmes-Wong, Bill Dotson, and Tim Stanton for their work on this project.

The UCLA Center for the Study of Women and the HuntingtonUSC Institute on California and the West granted me research affiliations, which have been lifelines to me as a scholar. To Bill Deverell, I owe a huge debt of gratitude. He has been a steadfast friend who went above and beyond by ensuring I had uninterrupted library access at USC. Thank you, Bill, for your unwavering support.

Numerous librarians, archivists, city employees, and individuals helped me find sources, gave me access to off-limits rooms,

provided information, and otherwise facilitated my research, and I am grateful to all of them, especially Dan McLaughlin, Mary Carter, Young Phong, and Tiffany Dueñas of the Pasadena Public Library; Anuja Navare of the Pasadena Museum of History; Bill Trimble of the Pasadena City Planning Office; Lilia Novelo of the Pasadena City Clerk’s Office; Anne Peterson and Keith Holeman of All Saints Church Pasadena; Judith Carter of the San Marino Historical Society; Debbie McEvilly, Raquel Larios, and Sonia Guerrero of the South Gate City Clerk’s Office; Bill Grady, Public Information Officer of Lakewood; Sarah Comfort of Iacaboni Library, Lakewood; and Laura Verlaque, Julie Yamashita, Mary Lou Langedyke, and Mike Lawler of the Lanterman Historical Museum, La Cañada.

Students played a pivotal role in this book. Many shared superb insights in my courses on suburban history and a few wrote research papers that enriched my own thinking. I thank students in my classes at UCLA, Claremont Graduate School, and Pitzer College, particularly Graham McNeill, Mercedes González-Ontañon, and Jada Higgins. Over the years, a team of student research assistants compiled the large US Census dataset on LA suburbia, which provided crucial empirical context for this book: Angela Hawk, Ryan Stoffers, Jennifer Vanore, Matthew Bunnett, Sera Gearhart, David Yun, and Desmond Weisenberg. A special thanks to Avi Gandhi for her immense help with the dataset during the late stages of this project. Other students assisted with research and various tasks, including Jean-Paul deGuzman, Allison Lauterbach, Jared Levine, Samantha Oliveri, Crystal Yanez, and Veronica Hernandez. As some have gone on to jobs with the federal government, nonprofits, and universities, I feel fortunate to have worked with them over the course of writing this book, and I am grateful for their invaluable assistance.

I’ve had the opportunity to present or workshop parts of my research on this book at various institutions, and I am indebted to those who made that possible: Margaret Crawford at the University of California, Berkeley; Michael Ebner and Ann Durkin Keating at the Chicago History Museum’s Urban History Seminar; Jo Gill at the University of Exeter; Dan Amsterdam and Doug Flamming at Georgia

Tech; Adam Arenson at Manhattan College; Ken Marcus, Donna Schuele, and Amy Essington at the Historical Society of Southern California; Jem Axelrod at the Occidental Institute for the Study of Los Angeles; and Andrew Sandoval-Strausz at Penn State University. A special thanks to the LA History & Metro Studies Group, where I workshopped chapters. And to my fellow coordinators of that group over the years—Kathy Feeley, Caitlin Parker, Andrea Thabet, David Levitus, Gena Carpio, Alyssa Ribeiro, Monica Jovanovich, Ian Baldwin, Lily Geismer, and Oscar Gutierrez—I am so grateful for your friendship, feedback, and camaraderie.

A number of friends and scholars shared sources, ideas, maps, photos, and/or read parts of the manuscript. I thank you for your generosity and invaluable insights: Jake Anbinder, Steve Aron, Eric Avila, Hal Barron, Brian Biery, Gena Carpio, Wendy Cheng, Peter Chesney, Jenny Cool, Jean-Paul deGuzman, Peter Dreier, Phil Ethington, Lily Geismer, Adam Goodman, Richard Harris, Andrew Highsmith, Greg Hise, Matthew Kautz, Kathy Kobayashi, Nancy Kwak, Matt Lassiter, Bill Leslie, David Levitus, Willow Lung-Amam, Jennifer Mapes (cartographer extraordinaire), Nancy Dorf Monarch, Michelle Nickerson, Mark Padoongpatt, James Rojas, Eva Saks, Kathy Seal, Tom Sitton, Raphe Sonenshein, Michael Tierney, Don Waldie, Jon Weiner, Michele Zack, and James Zarsadiaz. I am grateful to members of the LA Social History Group for reading early work, especially John Laslett, Steve Ross, Frank Stricker, Jennifer Luff, Craig Loftin, and the late Jan Reiff. Members of our short-lived but mighty writing group provided excellent feedback and warm friendship, and I’m grateful to all of you: Elaine Lewinnek, Lisa Orr, Hillary Jenks, and Denise Spooner.

The many individuals who shared their life stories with me through oral histories played a crucial role in the making of this book. Their personal reminiscences filled in the details of everyday life and the emotional experiences of living in changing suburbia. I am immensely grateful to each and every one of them.

My recent involvement with the Erasmus + grant team on “Urbanism and Suburbanization in the EU Countries and Abroad: Reflection in the Humanities, Social Sciences, and the Arts” has been

a truly enriching experience. It has enabled me to share my work with an exceptional group of European scholars and has facilitated the fruitful exchange of insights about the structures and experiences of suburbia transnationally. Thanks to the Erasmus + Programme for funding this initiative, and especially to Pavlína Flajšarová, Jiri Flajsar, Florian Freitag, Vit Vozenilek, Jaroslav Burian, Eric Langlois, Mauricette Fournier, and Franck Chignier Riboulon. And Andy Wiese, thank you for repping the US with me and sharing this adventure in a way that only two suburban history nerds can fully appreciate.

Several friends and fellow scholars went above and beyond during my years engaged in this project, and to them I owe a special debt of gratitude. Denise Spooner, dear friend and companion on this journey, thank you for your love and support. Susan Phillips, I thank you for your extraordinary kindness, love, and social justice leadership. Carol McKibben, your friendship and unflagging encouragement helped me through. I especially thank Erin Alden, Jonathan Pacheco Bell, Barbara Gunnare, Max Felker-Kantor, Jorge Leal, Elline Lipkin, Caitlin Parker, Andrew Sandoval-Strausz, Jen Vanore, and Jake Wegmann for your boundless encouragement and, in many cases, direct help with this book. Tim Gilfoyle and Jim Grossman, I am grateful for your enduring support and friendship. John Archer and Margaret Crawford, you both became my guardian angels when I bolted from academia and became an independent scholar, writing letters of support for funding and otherwise offering moral support over the years. I am truly grateful to you both. I am indebted to Ken Jackson, Betsy Blackmar, and Eric Foner for their intellectual inspiration that began in graduate school and has continued unabated. And a special thanks to Dolores Hayden, whose scholarship set the groundwork for this book.

I also am grateful to two scholars who have passed, Mike Davis and my dear friend Clark Davis, who both deeply influenced my thinking about Los Angeles. One of the last classes Clark taught was an oral history seminar that resulted in the book Advocates for Change, which gave voice to the individuals living through school desegregation. I drew often from that book, which renewed my

appreciation for Clark and the legacy he left behind in his life and work.

Andy Wiese, you have been a treasured friend and intellectual partner since our days at Columbia. I am thankful for your support and friendship, and your willingness to drop everything and talk suburbs when I needed those conversations. Your insights always elevated my understanding and have shaped this book in countless ways. I’m so grateful to have such a kind and brilliant friend. Allison Baker, friend and fellow historian, enormous thanks for sharing your research and personal archive on Lakewood, which you lent me at the start of the COVID shutdown. Your dissertation deeply shaped my understanding of that community, and your tremendous generosity enabled me to finish this book. While I thank my friends and colleagues who have helped me along the way, all errors are my responsibility alone.

To Susan Ferber of Oxford University Press, I owe enormous thanks for everything, starting with the interest you expressed in this project years ago, and continuing with your tireless work in guiding this manuscript to completion. I’m truly grateful for your editorial eye, personal encouragement, and sheer stamina. I am so lucky to have worked with you. I am also grateful to the scholars who reviewed the manuscript for Oxford—Josh Sides, Jerry González, and an anonymous reader—for their excellent feedback and belief in this project.

My family has been my bedrock, sustaining me in every way. For your love and support, thank you Tina Nicolaides, Jean Ramos, Anya Nicolaides, Vicki Lohser, Liz Tekus, George Papas, Sophia Khan, Brad Thornton, Tom Huang, Yvonne and Scott Carlson, and Ron Weisenberg. To my extraordinary brothers, Alex and Louie, your love and rock-solid support have kept alive the spirit of family that we grew up with, and I’m so glad that we still live within eight miles of each other. Thank you for always being there for me. My kids Desmond and Marina have lived with this book for the last dozen years. As they got older, they got more directly involved—Marina taking photos, Desmond compiling data tables and offering input on passages I was struggling with. More than that, they patiently put

up with a mom consumed with this book. I’m so grateful to you both, you are my heart and soul. David, you have the patience and heart of a saint. Your love, humor, sustenance, feedback, ideas, and fortitude truly carried me through. And when I needed it most, you sang “Three Little Birds,” which somehow completely worked. I am eternally grateful to you.

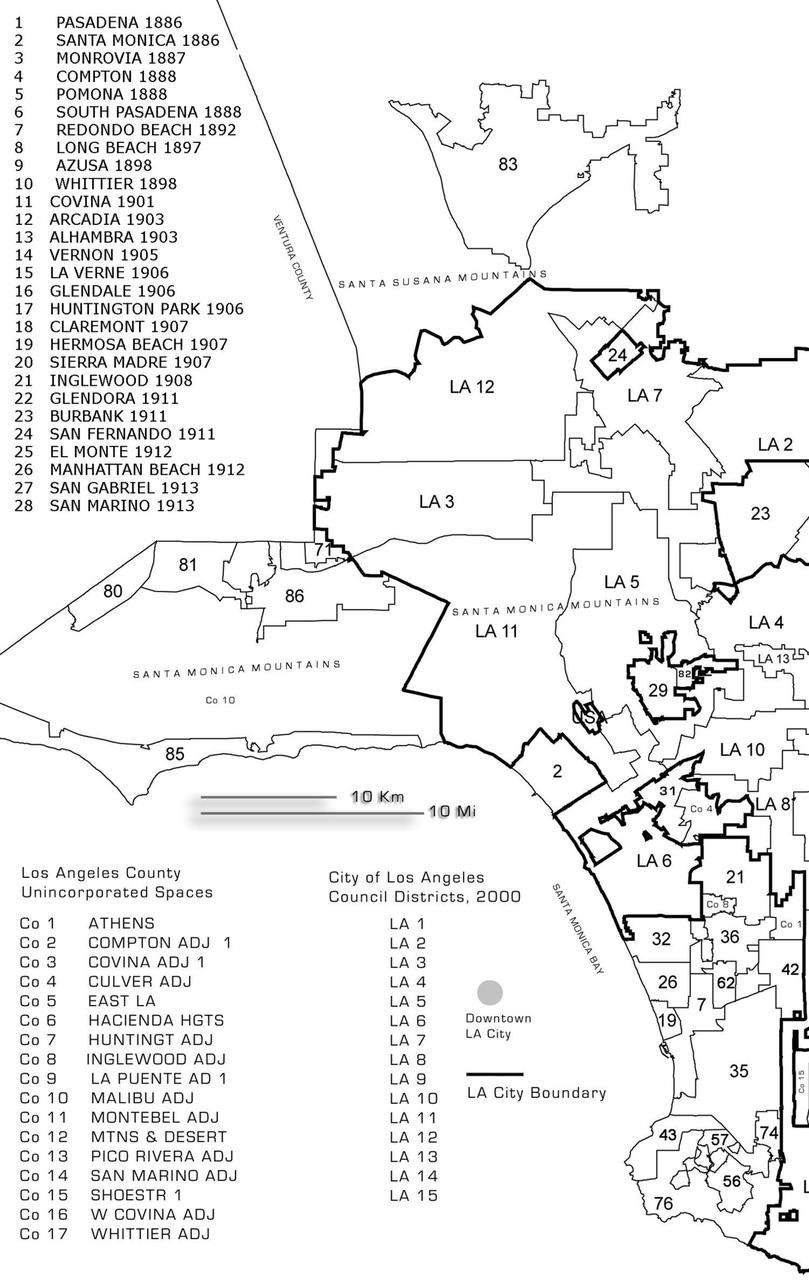

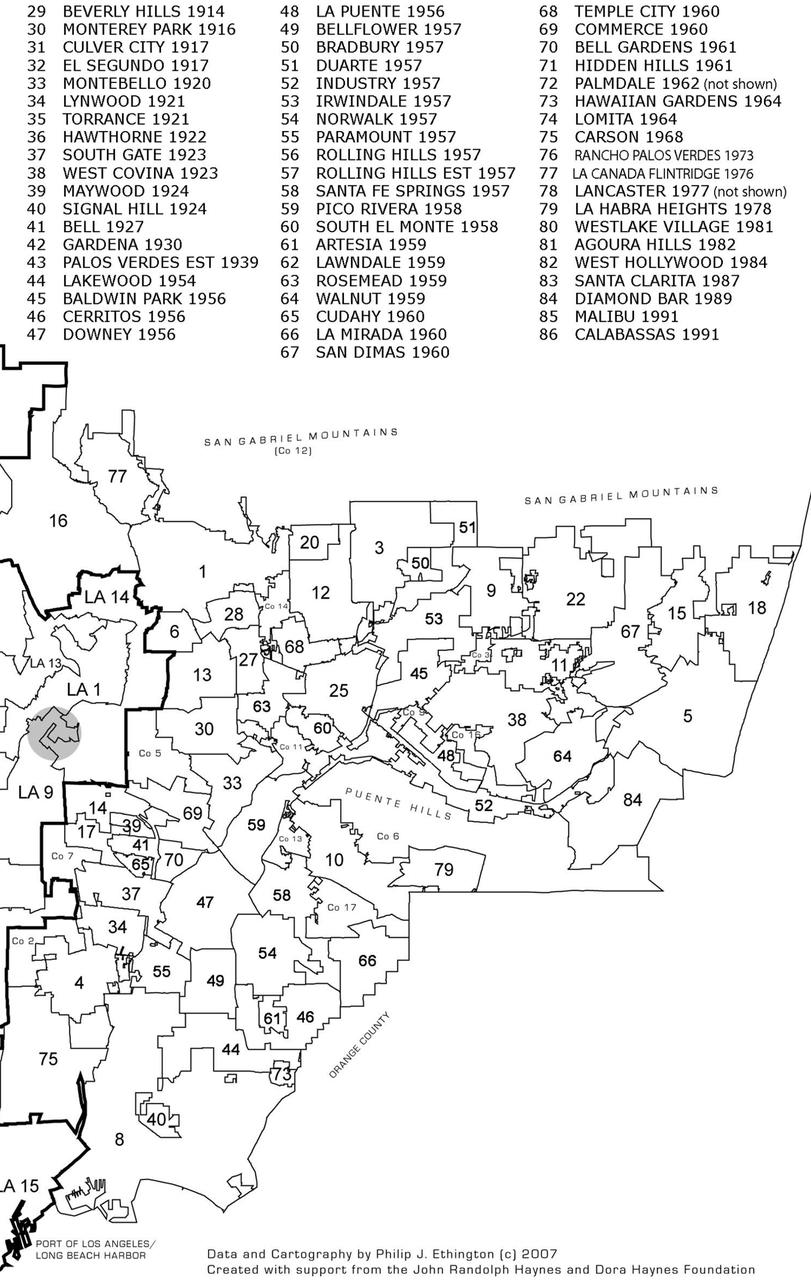

Municipalities and neighborhoods of Los Angeles County. Cartography by Philip J. Ethington ©2007.

Ethington base map edited and augmented by Becky Nicolaides.

The New Suburbia

Introduction

Certain images of the suburbs seem forever etched in our minds. The perfect green lawns. The cookouts. The lily-white suburbanites. But the days of suburbia as a white monolith are over.

This book tells the story of how this came to be. It explores how the suburbs transitioned from bastions of segregation into spaces of multiracial living. The “new suburbia” refers to America’s suburbs since the 1970s, which diversified at an accelerated pace.1 It is the second generation of suburbs after 1945, which transformed from starkly segregated whiteness into a more varied, uneven social landscape. Diversity in the new suburbia refers not just to race, but also to class, household composition, and the built landscape itself. In the new suburbia, white advantage persisted, but it existed alongside rising inequality, ethnic and racial diversity, and new family configurations.

The racial transformation was a particularly dramatic turnaround. From 1970 to 2020, nonwhites living in America’s suburbs rose from just under 10% to 45% of all suburbanites. From another vantage point, looking at the typical experience for Black Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, a majority of each group now lives in the suburbs. Something big has changed. Communities once imagined as “far whiter than most of the nation” have come to look like a cross-section of America itself.2

This matters because the suburb-city divide once defined deep inequalities that rested on racial difference. The suburbs were spaces of white advantage and privilege. For generations, they locked out nonwhites from access to those same privileges, bolstered by a thick web of biased policies. In the process, white suburbanites amassed generational wealth through homeownership, accrued political power from the local to federal level, and enjoyed the advantages of living in safe neighborhoods with good schools,

green spaces, and community amenities. Through long-standing exclusionary practices, suburbia helped produce racial inequality in America.

The rise of diverse suburbia, then, signals an important transformation while also raising crucial questions. Did the Latinos, Asians, and Black Americans who moved to the suburbs enjoy the same privileges as generations of whites? Did they embrace older, white suburban political traditions, including the tendency to exclude? Or did they adopt wholly new suburban ideals, values, and ways of living? Are they remaking the suburbs? Or are the suburbs remaking them?

The New Suburbia explores these questions by tracing the process of suburban change over 70 years, from the 1940s to the early 2000s, traversing the era of postwar white suburbia to the era of diversity. It focuses on Los Angeles, at the cutting edge of this transformation, where trends have happened earlier and more widely. Governor Gavin Newsom likes to call California “America’s coming attraction,” and LA’s suburban story is no exception.3 The stories that are playing out in LA may very well be a bellwether for the nation.

At the heart of this book are stories of the people and their suburban communities undergoing these transitions. In the new suburbia, Asian Americans, Black Americans, and Latinos moved into white suburbs that once barred them. They bought homes, enrolled their children in schools, and began navigating suburban life. They included people like Tao Chia Chi, Sandra Martinez, and Derrick Williams, whose life pathways all brought them to the suburbs of LA.

Tao Chia Chi was born in 1949, in Shanghai, China, the year Mao’s communist regime seized control of the country. Her father, a municipal employee in Shanghai, saw the writing on the wall—get the family out quickly or face certain persecution. Two months after Chia Chi’s birth, her father paid off the right people, disguised

himself as a farmer, and gathered his family—his wife, three young daughters, and a sister—to make their way to a rural village where they awaited a rowboat in the dark of night. When the fisherman arrived and saw Chia Chi, he asked, “Is this a new infant? If she cries, just choke her, otherwise we will all die.” Because many people from the mainland were trying to get out by boat, the waters were heavily patroled by communist soldiers. The girls managed to remain quiet, and the family made its way safely to a nearby island. From there, they hopped a cargo ship to Taiwan. The Taos started new lives and raised their children in Taiwan. At age 22, Chia Chi arrived as a student in the United States, where she eventually married a doctor and raised her own family.

Sandra Martinez was born in 1957, into a poor family in San Pedro Tlaquepaque, a town in Guadalajara, Mexico. Her father was a lawyer but didn’t live with the family. Sandra had 11 siblings. Her mother raised them as a single parent, without financial help, making her living cleaning, cooking, and caring for other people’s children. Without a home of their own, they lived with families willing to put them up, but they were cast out when the burden of housing 13 people became too much. When Sandra and each of her siblings reached the age of 10, they left school to work, cleaning homes or clerking in a shop. Their earnings went into the family pot, which eventually helped them move into their own rental house. When Sandra got older, she worked at a factory in Mexico making Brittania Jeans, a popular brand in the United States. In her early 20s, Sandra came to Los Angeles to join her sisters and marry her long-time boyfriend from Guadalajara.

Derrick Williams was born in 1965 and lived his early years in southwest Philadelphia. In 1972, his family purchased a home in West Oak Lane, an affluent community of Jewish and Italian families. They were one of the first Black families to move in. Derrick enjoyed a carefree childhood in a tight-knit neighborhood, with the freedom to roam and explore his surroundings. Within a 10-year span, however, rapid white flight flipped West Oak Lane from white to Black, and Derrick began experiencing intensive racial conflict at school, in the neighborhood, and in everyday life. As a teen, he was

bussed to an all-white high school across town, where attacks on Black students by neighborhood youth became a daily routine. After graduating, Derrick served in the elite Army Rangers, then moved to Los Angeles after the death of his mother. He met his future wife Pamela while working in IT at Boeing.4

Chia Chi, Sandra, and Derrick all eventually ended up living in the suburbs of Los Angeles—San Marino, South Gate, and Lakewood, respectively. They brought with them rich and disparate life experiences, turning places once stereotyped as bland, predictable, and white into something quite different. They represent the faces of the new suburbia. This book tells their stories and the history of suburban places remade by individuals like them.

With every passing year, more and more Americans live in the suburbs. As of 2020, fully 54.6% of all Americans lived in suburban places, yet another milestone along suburbia’s steady ascendance since World War II.5

As a paradigm of the suburban metropolis, Los Angeles represents an incredibly rich setting for probing suburbia’s recent past. LA pioneered many facets of suburban development in the twentieth century. Its wide array of historic suburban landscapes allows for analysis across a range of built environments. LA stands at the forefront of suburban diversification nationally. From 1970 to 2010, the proportion of all suburbanites in LA who were Black American, Latino, and Asian American rose from 26% to 70%, much higher than national averages. Similarly, in 2010, 60% of LA’s immigrants lived in the suburbs, compared to 51% nationally.6 LA has been experiencing the reverberations of these changes for decades.

Los Angeles has a reputation as a diverse metropolis, but, in the immediate post-World War II years, whites overwhelmingly predominated LA County, especially in the suburbs. In LA, then, the contrast from 1950 to 2010 was dramatic. LA’s suburbs flipped from

being nearly all white to nearly all multiracial. By 2010, the suburbs had more nonwhite homeowners than white ones, and they housed more immigrants and poor people than urbanized areas. Suburbia looked less like an antiseptic haven of segregation and more like a space of multiracial America.

Suburban households also grew more diverse in other ways. In line with national trends, family structure in LA’s suburbs evolved from young, straight nuclear families to more complex households after 1970, including more singles, divorced adults, LGBTQ individuals, cohabitating partners, extended families, and senior citizens. More suburban mothers worked outside the home, shattering earlier images of June Cleaver trapped at home mopping floors. By the end of the twentieth century, the older norm of breadwinner dad, stay-at-home mom, and kids had become entwined with class polarization. That suburban ideal found its fullest realization in the wealthiest suburbs. Despite these trends, the fact remained that married, homeowning families remained dominant in the suburbs; they often held a majority voice, and their vision continued to carry weight even as social realities shifted around them.

At the same time that suburbia’s ethnic, racial, and household profiles were changing, middle-class suburbs were shrinking. As the middle class itself was squeezed by economic restructuring, a new hourglass economy emerged with rising numbers of high- and lowpaying jobs and declining salaried jobs in between. These trends began showing up across suburban space as super-rich suburbs multiplied, as did suburbs of the poor. The gulfs dividing these communities—places like uber-wealthy Bradbury and, just two miles away, working-class Azusa—revealed an emerging suburban disequilibrium. Suburbia came to embody inequality itself. The notion of suburbia as a space of privilege was complicated by these patterns, which were appearing in LA and across the United States.7

Within a generation, the suburbs came to hold a much broader cross-section of people—rich, poor, Black, Latino, Asian, immigrant, the unhoused, the lavishly housed, and everyone in between.

Through it all, the common denominators of suburbia remained— low-slung landscapes of single-family homes and yards, pervasive homeownership, and families seeking the good life. This familiar, recognizable landscape has encompassed a growing array of peoples, social processes, and lived experiences. An American dream endured even as the dreamers changed.

For more than a century, white suburbia has represented a bourgeois utopia, a “white noose” around the urban core, the generator of white generational wealth, the racialized American dream. Historically speaking, racial exclusivity was vital to the appeal of a significant grouping of suburbs. It drove homeowner politics and entitlement claims in the post-World War II years. Suburbia represented a crucial “wage of whiteness” that conferred numerous advantages through property ownership, superior schools, safe neighborhoods, and preferential tax breaks, passed down from one generation of white families to the next. All of this was bolstered by a web of policies—from the local to the federal—that protected those entitlements. These realities created a justified perception of suburbia as a space of white privilege, an idea that took hold in the 1950s and 1960s and retained its power ever since.8

The story that has been told of suburban political culture in the postwar era is one dominated by white, homeowning, taxpaying parents who consolidated their political power from the local to the national level. It was a bipartisan cohort—encompassing suburbanites left, right, and center—united around the shared goals of protecting suburban communities from such threats as racial and ethnic others, the poor, school integration, affordable housing, and challenges to zoning for single-family homes.9 The New Suburbia continues that thread, but builds on stories of Asian, Latino, and Black American suburbanites who also took on suburban identities as homeowning, taxpaying parents. Diversifying suburbs indeed took a

quantum leap forward by accepting nonwhites, but these residents had a range of responses once they found themselves on the inside.

As more and more nonwhites became homeowners, they began benefitting from the advantages of suburban life. Some adopted long-standing homeowner traditions, particularly the inclinations to protect property and community from various threats. In the new suburbia, those threats evolved to encompass the casualties of economic and global change—poor immigrants, the working poor, and the unhoused. At the same time, suburban political culture began to widen along a spectrum ranging from inclusive and progressive on one end, to defensive and exclusionary on the other. Racially diverse residents lived across that spectrum and participated in all of these political cultures.

In many diversifying suburbs, internal divisions surfaced. Homeowners mobilized against renters. Citizens against noncitizens. Long-term homeowners against the newly arrived. Whites against nonwhites. “Diverse” did not always mean integrated. These conflicts played out not just between ethnic and race groups, but also within them. So, in some suburbs, for example, Chinese American residents rebuffed Chinese businesses in an attempt to keep out the “riff raff,” revealing Not in My Back Yard (NIMBY) proclivities toward other Chinese Americans. Suburban community dynamics began to reveal new power dynamics at play. In many places, the wealthiest clung tenaciously to power even as that group became more racially and ethnically diverse. In others, whiteness continued to confer power regardless of class. In other places, citizenship status delineated social divisions.

In some instances, then, new suburbanites of color continued long-lived habits of resisting the poor, the unhoused, the undocumented, renters, even ethnic landscapes—and that resistance became multiracial. They deployed well-developed exclusionary tools to serve their own needs.10 Especially as nonwhite homeownership climbed, residents of color came to hold increasing sway in their towns and helped make decisions about who would be included or excluded. Suburban advantage began to take on new ethnic and

racial hues. Their actions revealed divisions by class, citizenship, and race, in some ways redefining the protective boundaries around suburbia. The end result was persistent inequality across the metropolis, even as the suburbs themselves became much more diverse.

These exclusionary actions can be interpreted in a few ways. One is to see them as part of the politics of racial succession, a phenomenon in which minority groups struggle for their rights and then, after gaining a critical mass, work from the inside to protect the same system that originally marginalized them. As historian Scott Kurashige succinctly put it, “The more power you get within the system, the more you have a stake in upholding the status quo.”11 Working from the inside often included embracing the evolving racial hierarchies that privileged and subordinated different groups. This process played out in the nineteenth century for the Irish, Italians, Jews, and other Europeans once defined as racially inferior, who gained standing in part through differentiating themselves from other racial groups, such as Black Americans and Asians. Their own anti-Blackness, for example, elevated their status. In the post-World War II years, the suburbs themselves played a role in this racializing process. Suburban settlement was widely believed to promote the ethnic and racial assimilation of Italians, Poles, Greeks, Jews, and other European Americans who solidified their identity as “whites” in suburbia. These disparate groups found common ground around shared experiences, aspirations, interests, and racial solidarities in their segregated communities.12

After 1980, suburbia as a space of racial assimilation became murkier. As suburbia increasingly diversified, ethnic and racial identities could persist through the move to the suburbs. The impetus for this came from both without and within. Moving out of urban centers did not automatically erase white racializations of Blacks, Latinos, and Asians, somehow “whitening” them as suburbanization did to European ethnics in the postwar years. Blacks, Latinos, and Asians continued to be relegated to a racial terrain of nonwhiteness—Latinos pegged as illegal aliens, regardless

of birthplace; Asians as inassimilable aliens; and Blacks as racially inferior.13 No geographic move could fully erase those racial designations. At the same time, many Asians, Latinos, and Black Americans embraced their racial and ethnic identity even as they became suburbanites. The emergence of Asian “ethnoburbs” illustrates how this worked. In the ethnoburbs, ethnicity was reinforced through an embrace of ethnic aesthetic designs, businesses, and professional services catering to Asians, and ethnic community institutions. Ethnicity thus persisted in suburbia through proactive community-building and economic development aided by infusions of transnational wealth. These spaces not only complicated suburbia’s relationship to assimilation, but also presented arenas where new divisions might emerge. Some Chinese American suburbanites, for example, rebuffed the touchstones of ethnoburbia —the Chinese language signs, the 99 Ranch Markets, and architectural flourishes on homes—and fought to keep them out of their own suburbs. They favored a more Euro-American appearance, which they believed signified a higher status and a badge of American cultural citizenship. In this way, suburbia became a site of emerging cleavages by class, national origins, citizenship, and race. NIMBYism in multiracial suburbia, then, could strike in many directions—not only between groups but within them.

In diversifying suburbs, as in any multiracial society, the tensions between conflict and solidarity constantly hovered, posing choices to residents. Would they find common cause with other people of color or even neighbors of similar ethnic heritage? Or would divisiveness prevail? With their long-lived cultures of exclusivity and homeownership, the suburbs presented a context that made solidarity something of an uphill battle. Diverse suburbanites often felt compelled to protect their assets, which could foster conflict within communities and a defensiveness against perceived threats by outsiders.

Another way of interpreting the exclusionary tendencies of diverse suburbanites takes into account the total context of suburbia and race. For generations, whites were given unfettered access to

suburban life. Over those same generations, Black Americans, Asians, and Latinos were shut out. Once these groups finally made it in—after years of civil rights struggle—their grasp of the suburban dream represented a racial achievement not to be taken lightly. The right to hold property signified full citizenship. The fragility of this status in a society based on white supremacy, then, perhaps merited a defensive posture to protect their gains, even if it meant excluding others in the process.14 Suburban defensiveness was a hedge against a system that perennially racialized them as subordinate. The attainment of homeownership and access to decent neighborhoods was a seed planted to begin the process of accruing the sort of generational wealth and advantages that whites had enjoyed for decades. For many, suburban advantage was a goal worth defending.

If tendencies toward suburban exclusion persisted, the new suburbia also witnessed the emergence of more progressive, inclusive values that contradicted long-standing suburban norms. These communities embraced what political scientists Tom HogenEsch and Martin Saiz termed the “multicultural suburban dream,” which entailed a shared ethos of small-scale home and business ownership, a belief in the positive benefits of government, support for programs to help renters become homeowners, and encouragement of minority-owned small businesses.15 The New Suburbia, then, probes the range of values embraced by suburbanites—inclusive and expansive in some cases, exclusive and protective in others, even coexisting within certain communities.

The new suburbia invariably stoked white anxiety. Whites, after all, were being challenged to change long-standing ways of doing things, and their hold on power was under threat. Racial segregation had been a long and persistent dimension of suburban life for at least a century, ensuring white residents a high degree of social comfort and insulation. When the racial wall cracked, many whites perceived a sense of loss—of community, of control, and of social predictability. Their response invariably involved efforts to reassert control, whether through maintaining local political power, protecting

the look of their neighborhoods, intensifying calls for law and order, or even withdrawing from public life. This has been a recurrent dynamic as the suburbs become community spaces of difference.

Suburban inequality—not only across suburbs but within them—also defined the new suburbia and deeply shaped the texture of everyday life. Suburban fortunes came to vary radically. Some suburbs, such as South Gate and Van Nuys, were ravaged by plant closures and disinvestment. Others thrived from infusions of transnational capital and wealth, including Chinese ethnoburbs in the San Gabriel Valley. Some affluent suburbs, such as San Marino, drew on the social and fiscal capital of residents to ensure property protection and foster robust communities. Experiences varied widely depending on how larger structural forces—including economic restructuring, globalization, immigration, and rising neoliberalism—were affecting local life. These forces fueled the spread of wealth and poverty across suburban spaces, which in turn influenced how communities grappled with their newcomers.

Suburbia’s transformation occurred at a moment of deep government retrenchment. During the 1980s Reagan era, the federal government passed on the responsibilities of social services, welfare, and even immigration enforcement to states and localities. In this colossal handoff, the suburbs emerged as a new, important locus of authority. They formed policies and asserted new forms of social control, often targeting those most marginalized—the poor, undocumented, and unhoused.16 In California, the passage of Proposition 13 (1978) was another force of retrenchment. That property tax cutting measure was passed on the cusp of suburbia’s massive demographic transformation. One direct impact was LA County’s defunding of its human relations resources, civic initiatives to promote interracial cooperation and “the full acceptance of all citizens in all aspects of community life.”17 Prop 13 cuts left suburbs to fend for themselves when grappling with ethnoracial change.

While well-resourced towns like San Marino and Pasadena managed to form their own human relations entities, many other suburbs, such as South Gate and Lakewood, were left to muddle through on their own.18 This confluence of enhanced authority and fewer human relations resources created yet another dimension of uneven suburban fortunes and prospects for inclusive democracy. These emerging community cultures tended to demarcate who belonged and who didn’t, who had a social place and a civic voice and who did not. Those voices on the inside were the ones shaping local policy and community priorities. This affected not only the potential for democracy at the local level, but also for meaningful, fulfilling community life.

At the heart of this book are social histories that explore how social and civic life evolved in suburbs undergoing significant demographic transitions. How did community traditions evolve? What were people’s everyday experiences like? How did diversity affect involvement in clubs, volunteer work, schools, and other local institutions?

These questions speak to broad assumptions that many observers have made about how suburban life has changed from 1950 to the 2000s. According to conventional wisdom, in the 1950s and 1960s, social life was marked by intensive community engagement, even excessive by the standards of some. Yet, by the 1980s, just one generation removed, suburbia had become a place of fear, social disconnection, privatism, and community decline.19 What’s fascinating about this pendulum swing is that suburban design was often implicated in these radically different social outcomes. The same built environment that was initially thought to foster community connectedness in the early years was blamed for deep social alienation by the 1980s.20 Some observers blamed the decline on suburbia’s social homogeneity and long commuting times, which sapped free time and dampened civic energy.21 Still others blamed

ethnoracial diversity for the disengagement.22 Whatever the reasons, this led to the era of “bowling alone,” as political scientist Robert Putnam memorably described this increasing social disconnection. The New Suburbia questions the simple declension narrative, asking if it truly describes what was happening on the ground. Looking at specific suburbs suggests a mixed picture depending on factors like the class composition of a suburb or a suburb’s position in the regional economy.23 Some evidence suggests that community engagement persisted over the long haul, pivoting especially around suburban children and the schools. In suburbs rich to poor, children and the schools were crucial conduits of social integration, particularly for new immigrant suburbanites, belying the narrative of social breakdown in the post-1980 era.24 While The New Suburbia does not presume to be the last word on the question, it does offer insights that point to arenas of persistent engagement, like the schools, as well as the disparate impacts of structural forces, like political economy, on the prospects for social and civic health in suburban places. It’s unlikely that a design fix can solve the problem. Rather, suburbs that took proactive steps to integrate diverse newcomers seemed to offer the best chances for successful communities.25

Recently, histories of suburban life have emphasized two trends: suburban crisis and suburban regeneration, especially in the years after 1960. They are often told separately, in parallel lanes so to speak. The crisis narrative emphasizes the story of the white American middle class, which experienced a rising sense of victimization. Its crisis mentality arose around suburban issues including crime and drugs, child safety, encroachments on suburban land, and even dysfunctional social life. These concerns impelled white suburbanites to mobilize politically, advancing policies that perpetuated their advantage and interests while subordinating racial