ListofAbbreviations

APCActsofthePrivyCouncilofEngland,1542–1631,45vols,ed.

J.R.Dasent etal (London,1890–1964).

Besse, Sufferings J.Besse, ACollectionoftheSufferingsofthePeopleCalledQuakers... from1650,to...1689,2vols(London,1753).

BLBritishLibrary,London.

BLARSBedfordshireandLutonArchivesandRecordsService,Bedford. BloomandJamesJ.H.BloomandR.R.James, MedicalPractitionersintheDiocese ofLondon...1529–1725 (Cambridge,1935).

Bodl.BodleianLibrary,Oxford.

Boyle, CorrespondenceTheCorrespondenceofRobertBoyle,edsM.Hunter,A.Clericuzio andL.M.Principe,6vols(London,2001).

Cal.Rev.CalamyRevised.BeingaRevisionofEdmundCalamy’sAccountof theMinistersandOthersEjectedandSilenced,1660–2,ed. A.G.Matthews(Oxford,1934;reissued1988).

CCALCanterburyCathedralArchivesandLibrary,Canterbury.

CLROCorporationofLondonRecordOffice,London.

CSPDCalendarofStatePapers,Domestic.

CULCambridgeUniversityLibrary,Cambridge.

DCNQ DevonandCornwallNotesandQueries.

DHCDorsetHistoryCentre,Dorchester.

DRODevonRecordOffice,Exeter.

DWLDoctorWilliams’ Library,London.

EROEssexRecordOffice,Chelmsford.

ESkROEastSuffolkRecordOffice,Ipswich.

ESxROEastSussexRecordOffice,Lewes. Ewen, WitchHunting C.L’EstrangeEwen, WitchHuntingandWitchTrials.The IndictmentsforWitchcraftfromtheRecordsof1373AssizesHeld fortheHomeCircuitA.D.1559–1736 (London,1929).

FHLFriendsHouseLibrary,London.

FirthandRaitC.H.FirthandR.S.Rait(eds), ActsandOrdinancesofthe Interregnum,1642–1660,3vols(London,1911).

FosterJ.Foster(ed.), AlumniOxonienses:TheMembersoftheUniversity ofOxford,1500–1714,3vols(OxfordandLondon,1891–2).

FSLFolgerShakespeareLibrary,WashingtonDC Green, CPCC M.A.E.Green(ed.), CalendaroftheProceedingsofThe CommitteeforCompounding,&c,1643–1660,5vols(London, 1889–92).

GROGloucestershireRecordOffice,Gloucester.

HALSHertfordshireArchivesandLocalStudies,Hertford.

HenningB.Henning(ed.), TheHistoryofParliament:TheHouseof Commons,1660–1690,3vols(London,1983).

HLROHouseofLordsRecordOffice,London.

HMCHistoricalManuscriptsCommission

InnesSmithR.W.InnesSmith, English-SpeakingStudentsofMedicineat theUniversityofLeyden (Edinburgh&London,1932).

InnesSmithMSSInnesSmithMSS,EdinburghUniversity.

KHLCKentHistoryandLibraryCentre,Maidstone.

LAOLincolnshireArchivesOffice,Lincoln.

LMALondonMetropolitanArchives,London.

Locke, Correspondence DeBeer,E.S.(ed), TheCorrespondenceofJohnLocke,7vols (Oxford,OUP,1976–82).

LPLLambethPalaceLibrary,London.

LRROLeicestershireandRutlandRecordOffice,Leicester.

MunkW.Munk, TheRolloftheRoyalCollegeofPhysiciansof London,1518–1800,3vols(London,1878).

NNkRONorwich&NorfolkRecordOffice,Norwich.

NRONorthamptonshireRecordOffice,Northampton.

ODNBOxfordDictionaryofNationalBiography,60vols(Oxford, 2004).

Oldenburg, CorrespondenceTheCorrespondenceofHenryOldenburg,edsA.R.and M.B.Hall,13vols(Madison,Milwaukee,London& Philadelphia,1965–86).

RaachJ.H.Raach, ADirectoryofEnglishCountryPhysicians, 1603–1643 (London,1962).

RCPL,AnnalsAnnals,RoyalCollegeofPhysicians,London,3vols.

SALSocietyofApothecaries,London.

SHCSurreyHistoryCentre,Woking.

SUL,HPSheffieldUniversityLibrary,HartlibPapers.

TCDTrinityCollege,Dublin.

Thurloe, StatePapersACollectionoftheStatePapersofJohnThurloe,Esq., ed. T.Birch,7vols(London,1742).

TNATheNationalArchives,Kew,London.

VCHVictoriaCountyHistory.

VennJ.VennandJ.A.Venn(eds), AlumniCantabrigienses... fromtheEarliestTimesto1751,4vols(Cambridge,1922). Wal.Rev.WalkerRevisedBeingaRevisionofJohnWalker’ s Sufferings oftheClergyDuringtheGrandRebellion1642–60,ed. A.G.Matthews(Oxford,1948).

Wood, Ath.Ox. AnthonyWood, AthenaeOxonienses,4vols,ed.P.Bliss (London,1813–20).

Wood, Fasti seeWood, AthenaeOxonienses. WROWorcestershireRecordOffice,Worcester. WSAWiltshireandSwindonArchives,Chippenham. WSkROWestSuffolkRecordOffice,BuryStEdmunds. WSxROWestSussexRecordOffice,Chichester.

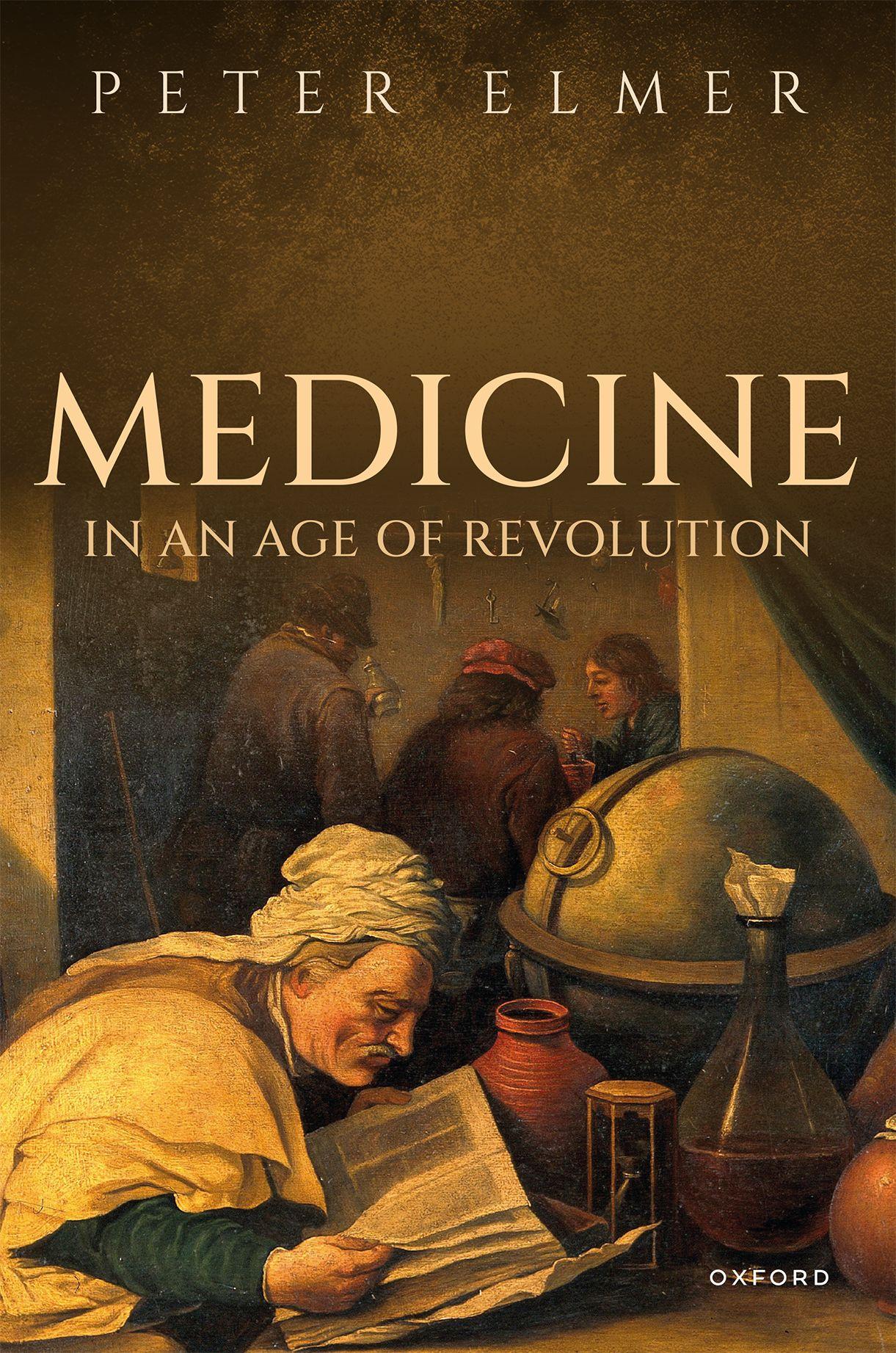

Introduction

Theideathatmedicinetodayisinextricablylinkedwithdevelopmentsinthe widerworldofpoliticsrequireslittleexplanation.Eversincethemid-nineteenth century,thetwoworldsofmedicineandpoliticshavegrownevercloserasthe governmentsofnationstateshavestriventofosterimprovementsinthehealthof theirsubjectsandcitizens.InBritain,ofcourse,thecreationofastate-funded NationalHealthServiceattheendofWorldWarTwomarkedtheculminationof thisprocessandcontinuestogeneratemuchheateddebateinpoliticalcircles.The ever-spirallingcostofmedicaltreatments,exacerbatedbythepaceoftechnologicalchangeandmedicalinnovation,hasinevitablysparkedmuchdiscussionas tohowgovernmentscancontinuetoaffordsuchasystemofhealthcare,but regardlessofthedebate,fewquestiontheoverallroleofthestateinsuchmatters. Issuessurroundingthehealthofthenationdominatepoliticaldiscussion,and medicalpractitioners,eitherasindividualsorthroughorganizationssuchasthe BMAornursingunions,makealargecontributiontothatdebate.Andwiththe onsetofamajor,globalpandemicintheshapeofCovid,theconnectionbetween governmentandmedicinehassimplyintensified.ItisimpossiblehereintheWest atleasttoseehowmedicinecouldeverbediscussedorunderstoodwithoutresort toawider,politicalcontext.

Itwasnotalwaysso.InBritain,priortothemid-nineteenthcentury,traditional historiographyaccordsaverylimitedroletotherelationshipbetweenmedicine andpolitics.Thedominantparadigmdescribesahealthsystemthatwasshapedby whathasbeendescribedasa ‘medicalmarketplace’ inwhichconsumers(patients) purchasedcuresandremediesfromarangeofproviders(healers),whomthey chosewithfewconstraints.¹Politicians,whetheratlocalornationallevel,hadlittle interestorsayinsuchday-to-daymattersandwerelargelysilentonissuessuchas theregulationofhealthcareoreducationandtrainingofmedicalpersonnel.At thesametime,thoseactiveinprovidingarangeofmedicalservicesrarelyargued forawiderroleforthestateinsuchmatterswiththenotableexceptionofstatefundedsupportformedicalassistancetotheever-expandingarmiesandnaviesof pre-modernBritain.Theapoliticalnatureofthemedicalworldofearlymodern BritainisperhapsbestcapturedintherecentworkofMargaretPelling,whohas arguedthatphysiciansinthisperiodlargelyexemptedthemselvesfrompolitical office-holdingatalllevelsofgovernance areflectionoftheambiguouslygenderednatureofthemedical ‘profession ’ atthistime.²

Whilethetwoworldsofmedicineandpoliticsmayhavecollidedinfrequently inthisperiod,historianshavenonethelessdetectedbroaderideologicalpatternsat workinearlymodernBritishmedicine.Theground-breakingworkinthisrespect wasundoubtedlyundertakenbyCharlesWebster,whoin1975,putforwarda compellingcaseforpuritanismastheprimemotorofscientificandmedical changeinmid-seventeenth-centuryEngland.³Buildingontheworkofanearlier generationofhistoriansofsciencewhohadarguedthatProtestantismingeneral, andpuritanisminparticular,weremostcongenialtoinnovationinthenatural sciences,Webster’swork,despiteitscritics,continuestoinformmuchgeneral debateastotheplaceofmedicineandscienceinthisperiod.Ithasalsoproved highlyinfluentialinshapingtheapproachoflatergenerationsofhistorianstospecific aspectsofthemedicalhistoryofearlymodernBritain.Inwhatfollows,IwishtoreexaminesomeofthesuppositionsthatliebehindtheWebsterthesisandtoaddressa rangeofsubsidiaryquestionsrelatedtotheplaceofmedicineandmedicalpractitionersinthewiderpoliticalcultureofearlymodernEngland.Websterhimself concludedthattheapocalypticmiddledecadesoftheseventeenthcentury,theperiod oncedescribedasthe ‘puritanrevolution’,witnessedadramaticshiftinattitudes towardsmedicineandnaturalphilosophythatamountedtonothinglessthana ‘great instauration’ oflearningonthelinesforeseenbytheEnglishpolymathFrancisBacon (1561–1626).ThisgreatawakeninghadcomeaboutasadirectresultoftheEnglish civilwarsinwhicharesurgentandforward-lookingpuritanismhadprovidedthe ideologicalunderpinningforamovementthatsawthecollapseofthe ancienrégime intheshapeoftheStuartsandthecreationofagodlyrepublic.

Itisnotmyintentionheretodisputethesignificanceoftheeventsthathelped tobringabouttheintellectualrevolutionthatWebstersoelegantlychartedinhis masterpiece, TheGreatInstauration.TheEnglishcivilwarsundoubtedlymarked agreatturningpointinthehistoryoftheBritishIsles,unleashingpowerfulforces thatwould,bytheendoftheseventeenthcentury,fullytransformtheBritishstate. However,theideathatpuritanismprovidedthevitalideologicalsparktofuel scientificandmedicalchangeinthesecondhalfoftheseventeenthcentury,as adumbratedbyWebsterandothers,isquestionableandopentodebate.Thekey pointatissueislargelyadefinitionalone,apointacknowledgedbyWebsterin 1986whenhesoughttoanswercriticsofthepuritanism-medicinehypothesiswho werecriticalofwhattheyperceivedastheall-encompassingandexcessivelybroad definitionofpuritanismadoptedin TheGreatInstauration. Websternowconcededthatthepuritansofmid-seventeenth-centuryEnglandwere ‘ neveracompletelyunifiedgroup’,thattheyrepresented ‘awholespectrumofattitudes’,and thatpuritanismitselfwas ‘inaconstantstateof flux ’.Henonethelessremained committedtotheideathatpuritanism,especiallyitsmoreradicalmanifestations, constitutedtheessentialcatalystformedicalprogressintheseventeenthcentury.⁴ Webster’sfocusontheiconoclasticandanti-authoritariannatureofthepuritan movementreflectsanapproachtothesubjectthathasbeenlargelydiscreditedby

mostrecentworkinthe field.BuildingontheworkofscholarssuchasNicholas TyackeandPatrickCollinson,historiansofreligionnowtendtoemphasizethe innateconservatismofpuritanism,withitscharacteristicemphasisonorderand hierarchy.⁵ Atthesametime,like-mindedscholarspositedtheviewthatpuritanismrepresentedaconstantlyevolvingandfracturingentity,forgedinthewhite heatofdebateoverthenatureoftheEnglishChurchfromthe1560sonwards. Some,likePeterLake,havestressedtheinclusivenatureofthatChurch,which allowedforaspectrumofopinionswhileatthesametimeimputinginnovationto theLaudianArminians.⁶ Othershavefocusedonpuritanism’sinnate, fissiparous tendencies,especiallyafter1640.Thisinturnhasencouragedtheideathat puritanismisbestseenasamovementsplitbetweentwoirreconcilableparts, radicalandconservative,thatwerepolesapartonmostsocial,religiousand politicalissues,particularlymattersofchurchgovernance.Theradicalwingof themovementthuscategoricallyrejectedtheideaofastatechurchwhileamuch larger,conservative, ‘mainstream’ groupsoughttoremodel,butnotdestroy,the AnglicanChurch.Thisnewscholarlyconsensus,however,hasalsoprovenfragile. TheworkofDavidComoonantinomianism,forexample,anditsrelationshipto ‘mainstream’ puritanism,hasonceagaincalledintoquestionanysimpledichotomythatmightreducepuritanismtooneoftwomutuallyexclusivecategoriesof religiousbelieforidentity.⁷

Oddly,thesedevelopmentshaveimpactedlittleonrecentaccountsofthe ideologicalrootsofthescientificrevolutionandmedicalreforminearlymodern England.⁸ Webster’swarningthatscholarsmightbestavoidarecoursetohead countingtoascertaintherelativecontributionofwell-definedreligiousgroupsto scientificandmedicaladvancehas,byandlarge,beenheeded.Generalhistoriesof theseventeenthcenturycontinuetoallocateaprominentroletopuritanismasa dynamicforceinscienceandmedicine.Andwhilefewnowrefertothemiddle yearsoftheseventeenthcenturyastheageofpuritanrevolution,moststillidentify theperiodfrom1640to1660asacriticalmomentintheemergenceofnewideas andpracticesintherelated fieldsofscienceandmedicine.Inwhatfollows,Iseek tore-examinethesedevelopmentsinthelightofrecentresearchintheburgeoning fieldofthesocialhistoryofmedicine,aswellasamassofnewevidencegleaned fromavastrangeofsources.Inparticular,thisstudyisindebtedtoresearch undertakenaspartofaWellcomeTrust–fundedprojectaimedatcreatinga databaseofallmedicalpractitionersinEngland,WalesandIrelandbetweenthe earlysixteenthandeighteenthcenturies.Theadvantagesofprosopographyare manifold.Inpiecingtogether,fromavarietyofsources,thedetailedbiographiesof thousandsofearlymodernhealers,itispossible, pace Webster,tomakeamore accurateanddetailedassessmentofthewaysinwhichreligiousandpolitical identitiesimpingeduponattitudestomedicalpracticeandbeliefs.Critically, suchanapproachalsofacilitatesgreaterunderstandingofthecomplexwebof networksthatmedicalpractitionersinhabited,andthusallowsonetomake firmer

judgementsastotheideologicalrootsofmedicalinnovation.Technology,asnever before,nowallowsthehistoriantogathervastamountsofhistoricaldata,with relativeease.Inutilizingthesedevelopments,itispossibletoprovideamuchfuller pictureofthestateofthemedical ‘profession’ inearlymodernEngland,andto detectunderlyingthemesinthelivesandcareersofthoseengagedinthehealing arts.Italsoallowsforamajorre-assessmentoftherelationshipbetweenmedicine, religionandpoliticsinEngland,whichformsthecoreofthisstudy.⁹

Oneoftheoverarchingassumptionsofthisstudyisthatthemiddledecadesof theseventeenthcenturyinEnglanddidindeedwitnessaseachangeinattitudesto medicineandhealing.Whilemanycontinuetoquestiontheideologicaloriginsof theEnglishRevolution,particularlyitsdebttotheiconoclasticzealofapuritan minority,fewwoulddisputetheextentoftheimpactofthecivilwarsuponall aspectsofBritishsocietyafter1640.Medicineanditspractitionerswerenot immunefromthewindsofchangeunleashedbymilitaryconflictandpolitical andreligiousupheavalwhichcontemporariesbelievedhad ‘turnedtheworld upsidedown ’.Thedesireforwholesalereformoftheorganizationandpractice ofmedicineaswellassupportfornewapproachestomedicalthinkingpermeate muchpublicandprivatediscourseinthisperiod.Evidenceforagrowingengagementwithmedicineandmedicalissuesisevidentfromavarietyofsources. Publicationofmedicalbooksandpamphlets,ofteninthevernacular,tookoff after1649,encouragedinpartbythecollapseofcensorshipinthewakeofmilitary conflict.¹⁰ Asweshallseeinchapter2,thelanguageofmedicineandhealing permeatedreligiousandpoliticaldiscussionofthecrisisengenderedbycivilwar, bothatthelocalandnationallevel,areflectioninpartofthegeneralpopulace’ s mindsetgroundedintheRenaissancecommonplaceofthebodypolitic.Medicine formanyheldthekeyastohowbesttoexplainandreacttothepoliticalcrisis unfoldinginthe1640s,theword ‘crisis’ itselfrepletewithmedicalconnotations.

Thedesirefor ‘healing’ waswidespreadandmayhaveprovidedamotiveforsome toengagemorecloselywithmedicine,includingactiveparticipationinthe provisionofmedicalcare.Thecollapseofthesystemofecclesiasticallicensing acrossEnglandandtheinabilityoftheCollegeofPhysicianstoexertitscustomary powersovermedicalinterlopersinLondonalmostcertainlyfacilitatedthisprocess.Moreover,thereislittledoubtthatthecivilwarsofthe1640s,followedbythe growingmilitarydemandsoftheEnglishstateinthe1650s,werecriticalin encouragingnewentrantsintothemedical ‘profession’.Asweshallsee,manyof thesenewrecruitswerekeentoexplorenovelavenuesofmedicalresearchand practice.Atthesametime,theemergenceofthe fiscal-militarystate,whichgrew exponentiallyhereafter,provided,asweshallsee,arangeofopportunitiesfor medicalpractitionerstoacquireenhancedsocialstatusandprofessionalcredit, moreoftenthannotthroughtheassumptionoflucrativegovernmentpostsand office-holding.¹¹Apothecariesandsurgeons,frequentlydepictedbefore1640as subservienttotheuniversity-educatedphysician,wereparticularlywellplacedto

capitalizeonthissuddenupsurgeindemandformedicalservices.Butotherstoo wereequallyattractedbythelureofacareerinmedicine.Thisisespeciallytruefor thosesonsofthegentryand ‘middlingsort’ whooptedforauniversityeducation. AsRobertFrankhasshown,thenumberofstudentsgraduatingwithmedical degreesatOxfordspiraledafter1640andcontinuedtogrowthereafter.¹² MedicineprovedequallypopularinInterregnumCambridge.Towhatextent thisgrowthinthenumbersofuniversity-educateddoctorscanbeunderstoodas aresponsetothegrowthindemandfortheirservicesisdifficulttodetermine.But therecanbelittledoubtthattheyearsafter1640witnessedamarkedupsurgein interestinmedicalstudy,bothwithinandoutsideacademia,whichultimately transformedearlymodernattitudestomedicine,naturalphilosophyandsociety.

Thegrowthinnumbersofmedicalpractitionersofalltypesafter1640was matchedbyaconcurrentgrowthofinterestinexploringnewchannelsofresearch invarious fieldsofmedicalenquiryincludingphysiologyandchemistry. Developmentsinboth fieldsweretosomeextentacontinuationofearlierinterests anddiscoveries mostnotablyHarvey’sdiscoveryofthecirculationoftheblood. After1640,however,thepaceofchangeandinnovationacceleratedasitbecame increasinglyentrenchedinthemedicalfacultiesofOxfordandCambridge. Medicalstudentswerenowlessweddedtothestudyofthetraditionalcurriculum whichemphasizedthecentralityofGalenichumoralismandweremoreopento newideasaboutthefunctioningofthebodyanditspotentialimpactuponthe treatmentofillness.¹³Oneby-productofthismedicalrenaissancewasagrowing focusuponthestudyofindividualdiseases,sparkedinpartbyaconcomitant revivalofinterestinHippocraticmedicinerecastasempiricismandepitomizedby theworkofThomasSydenham(1624–1689).Another,whichcanbefoundboth withinandoutsidetheuniversities,wasthevastupsurgeofinterestintheideas andpracticesoftheiatrochemistsorchymicalphysicians,particularlyParacelsus andvanHelmont,whichpromisedatvarioustimestotoppleGalenandGalenic medicinefromitsaccustomedpedestal.¹⁴ Thesedevelopmentsthushelpedto spawnwhatsomehaveseenasacoordinatedmedicalreformmovementinthe 1650scomposedofagroupoflike-mindedscholarsandenthusiastsfocusedon theremarkable figureofthePolishémigréSamuelHartlib(d.1662).

TherecanbenodoubtastothesignificanceoftheworkofHartlibandhis supportersandassociatesinraisingawarenessofboththeneedandpotentialfor wholesalemedicalreforminmid-seventeenth-centuryBritain.Hartlib’sEuropean connectionsfacilitatedacriticalexchangeofideaswhichallowedEnglishadvocatesofmedicalchangetolearnfrom,andadaptto,developmentsonthe continent.Atthesametime,home-grownradicalswereincreasinglycallingfor theimplementationofarangeofsocialreformsmanyofwhichfocusedonthe shortcomingsofcontemporarymedicineanditsimpactuponthoseleastableto payfortheservicesofmedicalspecialists.Thedesireforroot-and-branchchange isepitomizedbythecareerofNicholasCulpeper(1616–1654)whobecamethe

standardbearerforanewformofmedicalprovisionwhichdeliberatelyundercut theclosedshopoperatedbythephysiciansoftheCollegeinLondon.Areligious radicalandarepublicanwhohadfoughtinthecivilwars,Culpeperutilizedthe powerofprinttocastigatetheprivilegedphysicianwhileatthesametime empoweringthepatienttotakegreatercontroloverthewellbeingofhisor herbody.¹⁵ Theseedsofmedicalreformwerethuswellandtrulyplantedin InterregnumEngland,butthefailureofthevariousschemesoftheHartlibians andotherstocometofruitionsuggeststhatthegodlyauthoritieswhonowruled Englanddidnotsharethemedicalreformers’ zealforchange.Whilesomepuritans, broadlydefined,wereclearlyeagerforinnovation,others,particularlythosein positionsofauthority,werenot.Atthesametime,asIhopetodemonstratein whatfollows,variouselementsofthemedicalreformprogrammeweretoprove especiallyappealingtomedicsandothersdrawnfromtheranksofthepuritans’ staunchestreligiousandpoliticalopponents.ItisforthisreasonthatIargueherefor thecriticalroleoftheperiod,ratherthanspecificreligiousgroupings,increatinga conduciveatmosphereforthepromotionofmedicalchange.TheEnglish Revolution,medicallyspeaking,transformedthewholepopulation,regardlessof religiousandpoliticalaffiliation,andintheprocesscreatedanopportunityforallto speculatefreelyastothemeritsofawiderangeofmedicalinitiatives.

Itnonethelessremainstrue,Ibelieve,thatindividualmembersofthemedical reformmovementweresubject,likethegeneralityofthepopulation,tointense politicizationbecauseoftheeventsofthecivilwaranditsaftermath.Iusethis phrasefrequentlyinthisstudy, firstlyinthegeneralsenseofapeoplemademore awareoftheimpactofpoliticallifeandeventsontheirlivesandcareers.But secondly,todenotethewayinwhich,especiallyafter1660,politicaldifferences anddivisionsbecamepolarizedandfacilitatedtheemergenceoftwodistinct medicalcommunities.Noneofthisistoarguethatmedicinewasentirelyfreeof politicsbefore1640.Therecentstudyofthefuroresurroundingthedeathor ‘murder’ ofJamesIin1625isapowerfulreminderofthetightropethatroyal physicianswereforcedtowalkwhenconfessionalpoliticsintrudedontheirdaily work.¹⁶ NoramIseekingtodevalueordenigrateotherstudiesinthesocialhistory ofmedicinewhichhaveadoptedabroaderdefinitionoftheterm ‘political’ to incorporateissuessuchasgenderandtheirincorporationinthewiderliteratureof theperiod.¹⁷ Myusagehereharkensbacktoearlierstudieswhichsoughtto demonstratehow ‘high’ politicsmayhaveshapedthemedicallandscapeofthe seventeenthcentury.Thisstudyis,aboveall,anattempttoputpoliticsbackinto medicineandtoshowhowthelatterwasbothshapedbythepoliticaldebatesand divisionsoftheperiodwhileatthesametimesuggestingwaysinwhichmedicine mayhavecontributedtocontemporaryunderstandingofpoliticalbeliefand practices.

Inchapter2,Ibeginthisstudybynotingtheextenttowhichcontemporariesin the1640s,facedwiththecalamitousprospectofcivilwar,articulatedtheir

approachtotheseeventsthroughtheprismofanearlymoderncommonplace,the bodypolitic.Britishhistorianshave,byandlarge,tendedtoassumethatitdiedon thescaffoldalongwithCharlesIin1649whentheactofregicidefatallyexposed thefallacyofapoliticalsystembuiltontheideaofdivineright.¹⁸ Here,however, Iarguenotonlyforitscontinuingvitalityafter1649butalsoforitsremarkable abilitytosurviveandadaptinaworldwherepolitical,medical,philosophicaland scientificdevelopments,includingtheonsetofHobbesianmaterialismand Cartesianism,posedagrowingchallengetotheoldorder.Atthesametime, Iargue, pace Walzerandothers,thatpuritanismitselfwasnotinherentlyill disposedtoorganicistconceptsofthestate.Onthecontrary,Iarguethatitwas thecontinuingfascinationwiththeideaofasingle,unifiedandorganicbody politicthatencouragedpuritancommentators,includingthosewithamedical background,toengagewithahostofpoliticalissuesascontemporariesstruggled tocometotermswiththeconsequencesofcivilwarandreligiousandpolitical upheaval.Medicineandpoliticswerethusnaturalbedfellowsinaprovidential worldinwhichGodfrequentlyspoketomenandwomenthroughtheanalogyof thehumanbody.¹⁹

Therevivalofinterestintheideaofthebodypolitic,spawnedbythedebatesof thecivilwaryears,providesoneexplanationforthepoliticizationofhealersand healingafter1640.Inchapter3,Idiscussthemanifoldformsthatthisprocess took.Medicalpractitionerswere,ofcourse,activeinprovidingsupporttothetwo sidesinthepoliticalconflictonthebattlefield.Suchsupportwasnotrestricted, however,tovolunteeringto fightandserveintherespectivearmiesofParliament andKing.Ontheparliamentaryside,medicalmenwerealsoactiveinarangeof spheres,supportingthevariousregimesofParliamentandcommonwealthina rangeofcapacities,includingaspamphleteers,propagandistsandservantsofthe state.Many,significantly,optedforthe firsttimetostandforpoliticalandjudicial office,bothatnationalandlocallevel,aprocessinmarkedcontrasttothe apparentpoliticalapathyofmedicalpractitionersbefore1640.Indoingso,they frequentlybenefited,acquiringmedicalposts,status,wealthandproperty,includingchurchandcrownlands,inreturnfortheirunstintingsupportforthecause theparliamentarycause.Likewise,thosemedicalmenwhofoughtforandsupportedtheKing,andremainedloyaltotheStuartcause,wereequallypoliticized bytheeventsofthe1640sand1650s.Inthecaseofloyalmedicsorprospective medics,defeatengenderedarangeofresponsesincluding,atitsmostextreme,a willingnessamongsometoexploittheuniquepatient–practitionerrelationshipas anopportunitytoengageinespionageandplottingonbehalfoftheroyalistcause. Othersturnedtomedicinethrougheithernecessity,asinthecaseofthoseclergy wholosttheirlivings,orchoiceasisevidentfromthelargenumbersofloyalist studentswhooptedtostudyforamedicalratherthanaclericalcareerinthe 1650s.Thereislittledoubtthatasaresultofsuchdevelopmentsmedicineitself underwentacutepoliticization.

Nonetheless,inthischapterandelsewhere,Iargueagainsttheorthodoxview espousedbyCharlesWebsterandotherswhohavedepictedthemedicalrevolutionofthe1640sand1650sasaby-productofpuritanism.InlinewithPatrick Collinson’sviewofpuritanismasinherentlyconservative,Isuggest,withsome caveats,thatthecauseofmedicalreform,bothintermsofpracticeandtheory,was largelythepreserveofradicalgroupstothe ‘left’ ofthepuritanmainstream,who instinctivelyfavouredde-regulationofthemedical ‘profession’ combinedwitha deep-seatedantipathytowardGalenichumoralism.Thegrowinginterestinnew medicaltheoriesofthebodyanditscure,especiallythosebasedonthetenetsof ParacelsusandvanHelmont,werenot,however,limitedtoaradicalfringe.During thecourseofthe1650s,asmanyroyalistsandloyalAnglicansembarkedupon medicalstudy,oftenasanalternativetoaclericalcareer,theallureof ‘chymistry’ wastoproveespeciallyattractivetotheenemiesofthe ‘goodoldcause’ .

Inchapter4,Idiscussthesedevelopmentsfurtherwithamajorre-evaluationof alandmarkmomentinseventeenth-centuryEnglishmedicine,namelythe attemptin1665tooverthrowtheregulatoryauthorityoftheCollegeof PhysiciansinLondonandtoreplaceitwithanewbodythatfavouredtheuseof chemicalmedicinesandde-regulation.Ifsuccessful,theSocietyofChemical Physicianswould,inallprobability,haverevolutionizedmedicalpracticeinthe capitalandencouragedchangethroughouttherestofthecountry.Itsprincipal aimwastocreateafreemarketinmedicineinLondon,untrammelledbythe regulatorypowersoftheCollegeofPhysicians,andtounderminethehistoric dependenceofthemedicaleliteuponGalenichumoralism.Themembersofthe Society,whoclaimedthebackingofanimpressivenetworkofpowerfulnoblemen, courtiersandseniorclericsatthecourtoftherecentlyrestoredCharlesII,agitated tointroduceanewapproachtomedicineandhealingbasedupontheradical tenetsofParacelsus,vanHelmontandtheiriatrochemicalfollowers.Critically, suchaspirations,whichenvisagedthetruephysicianasboththecreatorand supplierofchemicallypreparedmedicines,threatenedtoerodethetraditional relationshipbetweendoctorsandapothecaries.Notsurprisingly,theiropponents respondedbydepictingthe ‘chymists’ asradicallysubversive,theheirsofthose religiousenthusiastswhojustafewyearsearlierhadthreatenedtoturntheworld upsidedown.Intheevent,theiatrochemistsfailedintheirobjective,despitethe factthatforthemostpartthemajorityoftheirmembersweremenwithimpeccableloyalistcredentialsandthatthebulkoftheirinfluentialsupporterswere drawnfromthehighestechelonsofRestorationsociety.Here,Idiscussthereasons forfailure,butalsoprovideanimportantpostscripttothiscriticalmomentin Englishmedicalhistoryintracingthecontinuingencouragementprofferedbythe Kingandseniorcourtiers,includingGilbertSheldon,archbishopofCanterbury, fortheaimsofthechymistsintheperiodafter1665.

OneimportantaspectoftheaffairoftheSocietyofChemicalPhysicianswasthe degreeofsupportofferedtothechymistsbyarchbishopSheldonandothersenior

clergymen,which,Iargue,waspartlyinspiredbySheldon’santipathyforthe puritandominatedCollegeofPhysicians,anditscovertsupportfornonconformistphysiciansinandoutsidethecapital.Assuch,itprovidesagoodexampleofthe wayinwhichmedicineandthemedical ‘profession’ after1660hadbecome polarizedandpoliticizedasaresultoftheeventsoftheprevioustwodecades.In chapters5and6,Idiscussthesedevelopmentsinmoredetailsoastodemonstrate howallfacetsofmedicalpracticeandthinkinghadfallenpreytopolitical imperatives.Aboveall,Iwishtoshowhowsuchaprocesswasincreasingly creatingamedicalworlddividedintotwocampsthatweredefinedbyreligious andpoliticalallegiance.Inchapter5,Iexaminethisprocessbyfocusingonthe impactoftheRestorationsettlementuponnonconformistmedicalpractitioners, manyofwhomweredrawnfromtheranksofejectedpuritanministersortheir families.Many,moreover,discouragedorpreventedfromacquiringamedical educationinEngland,wereincreasinglyattractedtothemedicalschoolsofthe UnitedProvinces(modern-dayNetherlands),wheretheynotonlyencountered thelatestmedicalthinkingbut,inmanycases,werealsoinveigledintosupporting variousplotstooverthrowtheStuarts.Indeed,manyofthealliancesforgedby EnglishmedicalstudentsofadissentingbackgroundinHollandatthistimewere latertoprovelong-lastingandsignificantformanyyearstocome.Followingthe GloriousRevolutionof1688,mostreturnedhomeandmanyweredrawninto politicaldisputeswiththeirToryandhighAnglicancolleagues,thusfurther encouragingtheprocessofpoliticizationintheeraofthe ‘rageofparty’

Inchapter6,incontrasttothecreationofwhatsomehavetermeda ‘dissenting medicaltradition’,Ifocusontheemergenceofapro-AnglicanandTorymedical establishmentinthefourdecadesafter1660.²⁰ Here,inparticular,Icharttherapid risetopowerofthepoliticallyactiveToryphysician,whocanbefoundingrowing numbersinhabitingthecorridorsofpowerinlateseventeenth-centuryEngland. Thisisespeciallyevidentattheleveloflocal,corporategovernment,where university-educatedphysicianswereincreasinglyactiveascommoncouncilmen, aldermenandmayorsandsharedinthejudicialaswellaspoliticalfunctionsof provincialoffice.Asdoctors,theywereideallysuitedtoprovideadviceand expertiseinrelationtowhatconstitutedgoodgovernance,frequentlycomparing theoperationsofthebodypolitictothatofthehumanbodyaswellasproviding suitablecuresforwhatmanyperceivedasthedesperatediseasesthen flourishing inEngland’scorporations.Someofthemoreeminentmembersoftheprofession wentonestagefurtherbyproducinglengthyanddetailedpublicationsdefending thepoliticalstatusquo,oftenwiththesupportandencouragementofthecrown whichfacilitatedaccesstothestate’sarchives.Bytheendoftheseventeenth century,then,physiciansofaTorybentwerefullyembeddedwithinthepolitical andreligiousestablishmentinawaythatwasinconceivablebefore1640.Inthe remainderofthechapter,Iexplorefurtherthenatureofthesenetworksandtheir impactonbothmedicineandpoliticsinthefourdecadesaftertheRestoration.

Finally,inchapter7,Ibrie flytouchonhowthepoliticizationofmedicineafter 1660,andtheemergenceoftwocontendingcampsdefinedbydifferingreligious andpoliticaloutlooks,impactedonmedicineitself.Oneaspectofthisprocess, whichIhavediscussedmorefullyelsewhere,relatestodivergentattitudesamong medicstotheage-oldproblemoftherelationshipbetweenmindandbody,or matterandspirit.Theexactnatureofthisrelationshipwasbothcomplexand controversial,particularlygiventhematerialisticassumptionsofmuchGalenic medicineincludingGalen’srejectionoftheideaofanimmortalsoul.However, sincetheMiddleAges,philosophers,physiciansandothershadreachedacompromise,wherebytheroleofspiritualentities,includingthesoul,withinthe humanbodywaspreserved.Adelicatebalanceofmaterialandspiritualforces wasgenerallyunderstoodtopertain,onewhichcameunderincreasingstrain followingtheoutbreakofcivilwarinEnglandinthe1640s.Thereensuedwhat onemightterma ‘crisisofspirit’ whichengulfednotonlytheintellectualworldbut alsothatimpingeduponallaspectsofreligiousandpoliticallife.Anglicanloyalists andsupportersofdivinerightruleincreasinglydepictedpuritanicalreligionasa formof ‘enthusiasm’ inwhichexcessiveweightwasallocatedtotheroleofspiritor spiritualenlightenmentintheattainmentofgodliness.Nonconformistsweresubsequentlysaidtobesufferingaformofmadness,which,invokingtherecent neurologicaldiscoveriesofThomasWillis,waswidelyconstruedasaformof physicalillness.Fortheirpart,puritansandtheirsuccessorsafter1660wereequally keentopreservetheroleofspiritineverydaylife,includingphysicalaffliction, preferringavarietyofalternativeexplanations,includingbewitchment,toaccount fortheirsufferings.AsMichaelMacDonaldpointedoutaslongagoas1981,mental breakdownandmadnesstendedto flourishincommunitiesandsocietieswhere conflictratherthanconcordprevailed.Itismycontentionherethatthosesuffering religiouspersecutionafter1660,nonconformists,werealsomostpronetoarangeof whatonemightlooselyterm ‘spiritualafflictions’,whichinturnwerebesttreatedby ‘spiritualphysicians’ drawnfromamongtheranksoftheejectedclergy.Incontrast, Anglicanphysicians,suspiciousofanyclaimontheroleofspiritindisease,were increasinglydrawnto ‘safer’ materialisticexplanationsforthesameailments.The Restoration,itmightbesaid,hadmademenandwomensick,butphysiciansnow differedashowbesttotreatsuchailmentsdependinguponwhichsideofthe politicaldividetheynowoccupied.

Notes

1.Theideaofamedicalmarketplacewas firstpopularizedbyearlymodernscholarsinthe 1980s.However,theideaisnotwithoutitscritics;seeforexampletheintroductoryessay andotheressaysinM.S.R.JennerandP.Wallis(eds), MedicineandtheMarketin EnglandandItsColonies,c.1450–c.1850 (Houndmills,Basingstoke,2007).

2.M.Pelling, ‘Politics,Medicine,andMasculinity:PhysiciansandOffice-bearinginEarly ModernEngland’,inM.PellingandS.Mandelbrote(eds), ThePracticeofReformin Health,MedicineandScience,1500–2000 (Aldershot,2005),81–105.

3.C.Webster, TheGreatInstauration:Science,MedicineandReform1626–1660 (London, 1975).

4.C.Webster, ‘Puritanism,SeparatismandScience’,inR.L.NumbersandD.C.Lindberg (eds), GodandNature:HistoricalEssaysontheEncounterbetweenChristianityand Science (Berkeley,CA,1986),192–217.Forarejoinder,seeW.J.Birken, ‘Merton Revisited:EnglishIndependencyandMedicalConservatismintheSeventeenth Century’,inE.L.Furdell(eds), TextualHealing:EssaysonMedievalandEarly ModernMedicine (Leiden&Boston,MA,2005),259–83.

5.Thereis,ofcourse,anenormousliteratureonthissubject.Forthecurrentdebate surroundingthemeaningoftheterm ‘puritan’ anditsvariousmanifestations,see especiallythevariousessaysinJ.CoffeyandP.C.H.Lim(eds), TheCambridge CompaniontoPuritanism (Cambridge,2008).I firstoutlinedmyreservationswith regardtothepuritanism-medicinehypothesisin ‘Medicine,ReligionandthePuritan Revolution’,inR.FrenchandA.Wear(eds), TheMedicalRevolutionoftheSeventeenth Century (Cambridge,1989),10–45.

6.See,forexample,P.Lake, ‘TheLaudianStyle:Order,UniformityandthePursuitofthe BeautyofHolinessinthe1630s’,inK.Fincham(ed.), TheEarlyStuartChurch, 1603–1642 (Basingstoke,1993),161–85.

7.D.R.Como, BlownbytheSpirit:PuritanismandtheEmergenceofanAntinomian UndergroundinPre-Civil-WarEngland (Stanford,2004),especiallychapter1,which containsaveryusefulandsuccinctsummaryofthelong-runningdebateovertherole andnatureofpuritanisminearlymodernEngland.

8.Itseemstelling,forexample,thatthecollectionofessaysinfootnote5abovecontains noessayon,orreappraisalof,therelationshipbetweenpuritanism,medicineand naturalphilosophy.

9.ExeterUniversity, ‘TheMedicalWorldofEarlyModernEngland,WalesandIreland, c.1500–1715’.The firstfruitsofthisresearchcannowbefoundontheprojectwebsiteat practitioners.exeter.ac.uk.Morecompletebiographiesofallthemedicalpractitioners discussedinthisworkwillappearonthesiteinduecoursealongsidethethree appendicescitedthroughout.

10.Webster, GreatInstauration,264–73.Forthebroadercontextinwhichmedical publishingtookplace,seeE.L.Furdell, PublishingandMedicineinEarlyModern England (Rochester,NY,2002).

11.ForinnovationinmedicalprovisionforcombatantsinEnglandduringandafterthe civilwars,seeE.GrubervonArni, JusticetotheMaimedSoldier:Nursing,MedicalCare andWelfareforSickandWoundedSoldiersandTheirFamiliesduringtheEnglishCivil WarsandInterregnum,1642–1660 (Aldershot,2001).Forrecentevaluationofmedical provisionandpersonnelinthatconflict,seeespeciallyI.Pells, ‘ReassessingFrontline MedicalPractitionersoftheBritishCivilWarsintheContextoftheSeventeenthCenturyMedicalWorld’ , HistoricalJournal,62(2019),399–425.

12.R.G.FrankJnr, ‘Medicine’,inN.Tyacke(ed.), TheHistoryoftheUniversityofOxford. VolumeIV.SeventeenthCenturyOxford (Oxford,1997),505–58,esp.511–13.Frank

estimatedthatbythe1650sOxfordwasattractingeightto fifteentimesasmany recruitstomedicineasitdid fiftyyearsearlier;ibid.,513.

13.Ibid.,527–34.

14.Theold-fashionspellingof ‘chymist’ and ‘chymistry’ ispreferredthroughoutthisstudy inlinewithcurrentscholarlythinkingwhichseekstoacknowledgethesomewhat anachronisticsenseofthemoremodernterm;seeespeciallyL.Principeand W.Newman, ‘AlchemyvsChemistry:TheEtymologicalOriginsofaHistoriographic Mistake’ , EarlyScienceandMedicine,3(1998),32–65.

15.ForabriefbiographyofthelifeandachievementsofCulpeper,seethearticlebyPatrick Curryin ODNB.

16.A.BellanyandT.Cogswell, TheMurderofKingJamesI (NewHaven&London,2015).

17.See,forexample,E.Decamp, CivicandMedicalWorldsinEarlyModernEngland: PerformingBarberyandSurgery (London,2016).

18.See,forexample,R.Zaller, ‘BreakingtheVessels:TheDesacralizationofMonarchyin EarlyModernEngland’ , SixteenthCenturyJournal,29(1998),757–78;M.Schoenfeldt, ‘ReadingBodies’,inK.SharpeandS.N.Zwicker(eds), Reading,SocietyandPoliticsin EarlyModernEngland (Cambridge,2003),232–3.

19.Forthepoliticizationofroyalphysicians,utilizingthenotionofthebodypolitic,inthe wakeoftheFrenchWarsofReligionatthecourtofHenriIV,seeJ.Soll, ‘Healingthe BodyPolitic:FrenchRoyalDoctors,History,andtheBirthofaNation1560–1634’ , RenaissanceQuarterly,55(2002),1259–86.Sollrelatesthisprocesstothehumanist endeavoursofRenaissancephysicianstowrite historiae ornarrativesofspecific illnesseswhichencouragedamedicalpreoccupationwithhistoryandwritingabout thepast.Idiscussthisdevelopmentmorefullyinchapter6inrelationtoloyalistand ToryphysiciansaftertheRestoration.

20.Fortheconceptofa ‘dissentingmedicaltradition’,seeW.J.Birken, ‘TheDissenting TraditioninEnglishMedicineoftheSeventeenthandEighteenthCenturies’ , Medical History,39(1995),197–218.

ThePrematureDeathofaRenaissance Commonplace

TheBodyPoliticinPuritanEngland,1640–1660

Introduction

Theideaofthebodypolitichasalonghistory.Indeed,thelanguageofclassical medicine,whichinformeddiscussionofthebodypoliticformuchofourperiod, continuestoshapethewaywetalkaboutpoliticstoday,evenifthemeaningof everydaytermssuchas ‘constitution’ , ‘crisis’ and ‘purging’ havelosttheiroriginal associationswiththephysicalbody.Inthesixteenthandseventeenthcenturies,it isgenerallyacknowledgedthatrecoursetotheanalogyofthebodypoliticrepresentedanessentiallyconservativepoliticalstance.Theorderlyandhierarchical organizationofthehumanbodywassaidtoactasbothamodelfor,andtoimitate, theharmoniousoperationsofthewidercosmos,includingtheworldofpolitics.¹

Notsurprisingly,itbecamewidelyassociatedwithmonarchicalformsofgovernment,inwhichtheroleoftheKingwasparalleledinthehumanbodybythatof theheadorheart.Lesserorganscarriedoutthefunctionsofminorofficesofstate andgovernment,whilethepartplayedbytherestofthepopulationwasreserved forthehands,feetandstomach.Theorganicconceptofthestate,whichwas mirroredatalllevelsofgovernmentinearlymodernBritain,thusprovideda blueprintforpoliticiansandpoliticalcommentatorsandanoverarchingmetaphysicalandanalogicaljustificationformaintainingthestatusquo.Inanagein whicheducatedmenandwomen,aswellasmanyoftheirilliterateinferiors,were wellversedinthelanguageofhumoralmedicine,recoursetothelanguageofthe bodypoliticwasubiquitousandcanbefoundinparliamentarydebatesand privatediaries,aswellastheburgeoningcultureofprintanddailynewsletters.

Mosthistorianswhohavefocusedonthelegitimatingauthorityofideasdrawn fromthebodypoliticinearlymodernBritishpoliticaldiscoursehave,however, tendedtoconcentratealmostexclusivelyonitsrelevancefortheperiodbefore 1640.Thefateoftheconceptofthebodypoliticaftertheonsetofcivilwarandthe executionofitshead,CharlesI,in1649,hasevokedlittlecomment.Moreover, whenhistorianshavecommentedonsuchmatterstheyhavegenerallyassumedas amatterofcoursethattherevolutionaryforcesunleashedinBritaininthe1640s

precipitatedthedemiseoforganicistformsofdiscourseandtheirreplacementby newwaysofspeakingaboutgovernmentandthegoverned.Typicalofthiswayof thinkingistheapproachtakenbyMichaelWalzerinhishighlyinfluential,though nowsomewhatoutdated,studyofcivilwarpolitics, TheRevolutionoftheSaints, firstpublishedin1966.²Walzerportrayedthepuritanpoliticiansandpreachersof thecivilwareraasharbingersofanewpoliticalorder.Theoldveritiesand commonplaces,basedonanorganicimageofthestate,heldnoplaceintheir metaphysicalorpoliticalworldview.Instead,puritanismwasdepictedbyWalzer asaradicalandprogressiveideologyandthepost–civilwarperiodasaneraof reconstructioninwhichanewkingdommodelledonthebiblicalarchetypeofthe NewJerusalemreplacedmoretraditionalformsofgovernmentbasedondivine rightmonarchy.Theoutcome,despitethesetbackoftheRestoration,wasabrave newworldinwhichtheradicalideasofMilton,HobbesandLocke flourishedto thedetrimentofoldernotionsofpoliticalorderbasedonnaturalcorrespondences andbodilymetaphors.

Despitearevolutioninhistoricalthinkinginthelastthirtyyearsinrelationto theoriginsoftheEnglishcivilwar,mosthistorianscontinuetosubscribetothe viewthattheeventsofthe1640smarkedthedemiseoftheimageoftheorganic state.EvenrevisionistssuchasKevinSharpe,whohasdonemorethanmostto resuscitatetheimageofCharlesIasanableandreform-minded,ifmisunderstood,headofstate,continuetopromotetheviewthattheperiodfrom1642to 1660markedadecisivebreakinthecultural,politicalandintellectuallifeofthe nation.Sharpethuscontendsthatthisperiodwitnessedanendtotheoldverities, analoguesandmetaphorsthatconstruedpre–civilwarpoliticalthinking,destroyedastheywerebytheinnateradicalismofthepuritanagenda.³Likewise, culturalhistoriansofthebodyhavebeenquicktodatethedeathofthebody politictothemiddledecadesoftheseventeenthcentury,evenif,asinthecaseof JonathanSawday,thisprocesshasbeenattributedtoscientificandphilosophical developmentsratherthanthehurlyburlyofcontemporarypoliticalevents. ⁴ Here, Iwouldliketosuggestthatthedeathofthebodypoliticandrelatedformsof politicaldiscourse,likethedemiseofMarkTwain,hasbeensomewhatexaggerated.Beliefinanorganicandhierarchicalstate,shapedbypopularunderstanding oftheworkingofthehumanbody,continuedtoinformawidespectrumof opinion,both ‘elite’ and ‘popular’,intheperiodfrom1640to1660.Mostcrucially, suchideaswereinvokednotjustbyStuartapologistsandsequestratedAnglican ministers,buttheywerealsoactivelypromotedbymanypeopleassociatedwith thepuritanmainstreamorthose ‘churchpuritans’ whoeagerlysoughttopreserve theideaofasingle,unifiedstatechurch.

Onwhatbasisthenhavehistoriansconsignedtheconceptofthebodypoliticto thedustbinofhistoryby1660?Twomainargumentshavebeenputforwardto explainitsdemise.Firstly,followingWalzer,thereisthesuggestionthatorganicist notionsofthestateheldnoplaceinapuritanpoliticalworldviewthatwas

essentiallyradicalandiconoclastic.Suchviewsgainedwidecurrencyinthe1960s and1970s,especiallyintheworkofMarxisthistoriansofthe ‘EnglishRevolution’ suchasChristopherHillandhavecontinuedtoinformtheworkoflaterwriters concernedwiththepoliticallegacyofthe ‘puritanrevolution’.Integraltothis explanationistheexceptionalemphasisthatpuritanpreachersandpropagandists arethoughttohaveplaceduponthenotionofasocialcontractbetweengovernor andgoverned,itselfaproductoftheCalvinistpreoccupationwithcovenant theology.Accordingtothisview,puritanssawbothchurchandstateas ‘artificial institutions,createdbyanactofwilloftheirindividualmembersandsubjectto changebythem’.Here,theemphasisisplacedupontheoriginofpoliticalrelations forwhich ‘organicanalogiesseemeddeficient’ . ⁵ Asecondexplanationforthe demiseofthebodypolitichasfocusedontheroleofthenewscience,especially Cartesianmechanism,indismantlingthescientificpropsofaworldviewbasedon structuralcorrespondencesandanalogouspatternsofbehaviourinthecosmos. Thisviewhasbeenputforward,forexample,byJonathanSawday,whohas accordinglydatedthedemiseofthebodypolitictothesecondhalfofthe seventeenthcentury.⁶

Inmanyrespects,itishardtodenythevalidityoftheseclaimsinthefaceofthe growingimpactoftheScientificRevolutioninthesecondhalfoftheseventeenth century.Someimportantcaveats,however,areworthyofconsideration.In the firstplace,thereislittleevidenceonthegroundtosuggestthatresorttothe languageofthebodypoliticandsimilaranalogicalthinkingwaslimitedinthe immediateaftermathoftheRestorationtotheconservativepoliticaldiscourseof triumphantroyalistsandAnglicanministers.Onthecontrary,organicistpolitical thinkingcontinuedtoappealtoabroadcrosssectionofthepublicafter1660, includingmanywhohadformerlyservedorsupportedParliamentandthe Cromwellianstateintheprevioustwodecades.Thedesireforreligiouspeace andpoliticalharmonywasbothgenuineandwidespreadintheyearsimmediately followingthereturnofCharlesII,andtheimageofthebodyprovidedcommentatorsofvariousbackgroundswithacommonlanguagetoexpresssuchaspirations.⁷ Itwouldbeamistake,however,toassumethatthecontinuedrecourseto organicistpoliticalideasrepresentedaconservativereactiononthepartofsuch menandarejectionoftheirformercommitmenttotheradicaloverhaulofsociety. AsmuchrecentworkontheoriginsoftheEnglishcivilwarshassuggested, puritanismwasnot, pace Walzerandothers,aninherentlyrevolutionaryideology. Norweremostpre– andpost–civilwar ‘puritans’ intentondestroyingpolitical consensusandtheideaofanintegratedandunitarystate.Indeed,theircommitmenttothevaluesofahierarchicalandorganiciststatewereevidentbeforethe outbreakofcivilwarin1642,continuedthroughoutthe1640sand1650s,and resurfacedagaininthe1660sand1670swhentheirspokesmenconsistently appealedforthere-establishmentoftraditionalpoliticalformsbasedonthe ancientconstitutionofking,aristocracyandcommons.

Itwouldbewrong,however,toinferfromthisthatpuritansubscriptiontothe consensuallanguageofthebodypoliticmeantthattherewerenodifferencesof opinionoremphasiswiththeirreligiousandpoliticalrivalsinchurchandstate.As KevinSharpehasnoted, ‘acommonsharedlanguagecouldarticulatedifferent, evencontrarypositions’ . ⁸ Aboveall,itisnecessarytoacknowledgethatthe citationofharmonistthinkingandparallelsdrawnbetweenhumanandpolitical bodiesmightaseasilyarticulatecriticismofthestatusquoasmuchasrepresent slavishacceptanceofthetraditionalpoliticalorder.Asearlyas1614,thecourt preacherandCalvinistJohnRawlinsonremindedJamesIofhisdutytohis subjectsbyrecoursetotheanalogyofthebodypolitic.Worriedbytheeffectof excessivetaxationonthepoor,RawlinsonwarnedtheKingthat ‘[s]houldthehead inthenaturallbodydrawallthebloud,andmarrow,andsubstanceoftheother memberstoitselfe,itmustneedsturnetothedestructionoftheheadeitselfe.For howshouldtheheadcontinuewithoutabody?’⁹ Priorto1640,however,itwas rareforpreachers,puritanorotherwise,tocriticizetheheadofthebodypoliticin thisfashion.Moreoftenthannot,theangerofdissidentsorcriticswasdirected towardsotheragentsofthestate,suchaslawyers,whointhewordsofthe LancashirepuritanChristopherHudsonshouldbe ‘thePhysitiansnotthehorseleechesorblood-suckersofyeComonwealth’.¹⁰ Hudson’sviewsechoedthoseof anotherpuritanministerandradicalcriticofthegovernment,ThomasScot,who in1623laudedthelegalprofessionas ‘thePhysitiansofthebodypolitique’ while atthesametimecondemningmanyoftheirpractices.¹¹

Significantly,bothHudsonandScotusedthepublicplatformofthecounty assizesasanopportunitytoexpresscriticismofthegovernmentofthebodypolitic undertheearlyStuarts.Similartacticswereemployedbythepuritanlecturer, ThomasSutton,whoin1622admonishedthejudgesofthehomecircuitby remindingthemthat ‘[o]fallthepartsinthebodyNaturallthebraineismost subjectuntodiseases,andofallpartsinthebodyPolitiquetheMagistratemost obnoxioustoslipsandfalls’.Preachedinaperiodofrelativepoliticalcalm, Sutton’ssermonwasnotpublisheduntil1631whenthechangedcircumstances broughtaboutbyCharlesI’srejectionofParliamentandonsetofthePersonal Rulegavehiswordsaddedbiteandmenace.¹²Thepulpitonoccasionssuchas theseenabledpuritancriticsoftheregimetopropagatetheirowndistinctive versionofthebodypolitic,whichdifferedinemphasisratherthankindfromthat espousedbytheiropponentsinchurchandstate.Inalltheexamplescitedand countlessothers,thepuritanemphasisconsistentlyreiteratedtheneedtopreserve order,hierarchyandunityinthegodlycommonwealth.Thisentailed,aboveall,a profoundrespectforthedoctrineofcallings,wherebyallwereexpectedto performtheirallottedroleinsocietyinmuchthesamewayasthevarious membersorpartsofthebodywereallocatedtheirparticularfunctions.¹³ Puritanrespectforsocialorderwasnevermoreapparentthaninthesanctity bestoweduponthethreeprofessions:thechurch,lawandmedicine.Typically,

ThomasSuttonidentifiedthethreeprincipalmembersofthebodypoliticasthe magistrate,lawyerandphysician,whichhecorrelatedwiththeroleplayedinthe humanbodybythebrain,liverandheart.¹⁴ Otherswidenedthistrinitytoinclude theclergy.TheNorthamptonshirepuritan,JosephBentham,forexample,invoked theanalogyofthehumanbodytoexplainwhyitwasessentialthatlaymenandthe unlearnedshouldnotintrudethemselvesintotheclericalsphere:

Inabodyallmembershavenotthesamevigour,neitheraretheguiftsgrantedto allinthemysticallbody.Bodilymembersintrudenotintoeachothersoffice: neitherinthemysticallbodyshouldtheythrustthemselvesintoanother’ s calling.¹⁵

Suchconcernfororderandobediencetothedoctrineofcallingspermeated puritandiscoursepriorto1640.Itwasnoticeablypresentintheattitudeofpuritan physicianstointerlopersintheprofessionofphysick.BothJohnCottaandJames Hart,puritanswhopractisedinNorthamptoninthe firsthalfoftheseventeenth century,declaimedinprintagainstthosewhoregularlyinvadedthemedical sphereandcalledforgreaterpolicinginthisarea.Insodoing,theyalsoechoed anothercommonrefrainofpuritanpreacherswhorepeatedlywarnedagainstthe dangersofexcessivecuriosityandtransgressingtheboundsofone’sdivinely allottedcompetence.¹⁶ Suchrespectfortraditionalvalueswastypicalofpuritan socialthinkinginthisperiod,andcontrastswiththeverydifferentpicturepainted byWalzerandothers.Thoughpuritanministersandlaymenmayhavecriticized aspectsofthevariouspoliciesofthegovernmentofCharlesIintheyears immediatelypriortotheoutbreakofthecivilwar,theydidsoinlargepartwith adeferentialattitudetoauthorityingeneralandinaspiritofconservatismaimed atpreservingratherthanoverturningtheexistingsocialorder.Theinequalitiesof theCommonwealth,sofrequentlylikenedtodifferencesinotheraspectsofthe divinecreation,wereseenbypuritancommentatorsasanaturalby-productofa hierarchicallyorderedcosmosinwhichthehumanbodyactedasaprime exemplar.

Recoursetosuchmodesofthinkingcontinuedtopermeatepuritandiscourse throughoutthetroubledyearsofthe1640sand1650s.Indeed,asWalzerhimself noted, ‘[m]edicalterminologyprovidedoneofthekeythemesoftherevolutionary period’,apointunderlinedbyDavidCressyinhisin-depthstudyofthecritical yearsbetween1640and1642.¹⁷ Now,however,thestresswasondiagnosisand cureandtherewasnoshortageofvolunteers,onbothsidesofthegrowing politicaldivide,tooffermedicallyinformedadvicetothose ‘statephysicians’

whoresidedatcourtandsatinParliament.InthecaseofthepuritanicaloppositiontotheCarolinechurchandstate,recoursetosuchideaswasmostevidentin thatseriesoffastsermonspreachedbeforeParliament,andimitatedelsewherein England,throughoutthe1640s.AsearlyasNovember1640,thepopularpuritan preacherStephenMarshallhadcomparedParliamentto ‘aColledgofPhysicians ’ towhom ‘itmayseemunfittoprescribe ...awayof cure ’.¹⁸ Itdidnottakelong, however,forhisclericalcolleaguestogatherupthecouragetooffertheirobservationsandremediesfortheailingbodypolitic.InFebruary1643,JohnMarston, preachingbeforealargeauditoryatStMargaret’s,Westminster,includingnumerousmembersoftheHouseofCommons,expandedonMarshall’sanalogicaltrain ofthoughtwhenhedeclaredthat ‘theStatehathlonglainesickofafeavour,and wehavehadmorethenaColledgeofPhysitiansinthisblestParliament ’.Alluding totheexecutionofStrafford,hewentontoclaimthat ‘toassuagetheheatofthis distemper,theyhaveletitblood,butdiscreetlyinonevaineonely,lestitbleedto death’.¹⁹ Asamoderateandsomewhatreluctantsupporterofthewar,Marston andotherslikehimwarnedagainstexcessiverecoursetophlebotomyorbloodshedinresolvingtheproblemsofthebodypolitic.²⁰ Otherswerelessfastidious whenitcametosupportingthecallforgreaterbloodletting,andmanyresortedto medicalanalogiesinordertovindicatethestanceofParliament.Themilitant PresbyterianJohnBrinsley,forexample,inafastsermonpreachedbeforethe godlycorporationofGreatYarmouthinDecember1642,warmlysupportedthe warbylikeningGod’sroleinorchestratingtheoutcomeoftheconflicttothatofa physiciansuperintendingasurgeon.Inprescribingadetailedaccountofthe necessaryprocedurestobefollowed,Brinsleywasatpainstoabsolve Parliament,intheguiseofthesurgeon,fromsomedegreeofresponsibilityfor theescalatingconflictbysuggestingthatitwasultimatelyGod,intheroleofthe physician,whowasresponsibleforwieldingthelancet.Healonedecided ‘what personsitshallstrike,whatincisionitshallmake,howdeepitshallgo,howmany, notonlyounces,butdroppsofblooditshalldraw’.²¹

Theanalogyofthebodypoliticwasaremarkably flexibletoolofpolitical analysisinthe1640sandwasreadilyadaptedtoprovidevaryingdegreesof comfortandunderstandingforthoseseekingtomakesenseof,andtorespond to,thegrowingconflictbetweenKingandParliament.Thosewhowishedtoseea militantresponsetothepoliticalcrisis,suchastheExeterpuritan,JohnBond,thus resortedtocondemningtemporizersandmoderatesbycomparingtheirwords andactionstothosepatientswhoshun ‘violentremedies’ andarguethat ‘such physickistoocorrosive,andmayendangerthewholepolitickebody’.Inpreferencetotheir ‘Lenitives,coolingjulepsandpalliations’,Bondprescribedasawas the ‘bestsalve’ foragangrene,acourseofactionwhichdisallowedfurtherand dangerousprevarication.Fouryearslater,reflectingontherecentsiegeofparliamentarianExeterbytheroyalistarmiesofthewest,Bondonceagainresortedto thelanguageoftheconsultingroomwhenhecomparedthecitytoabodythatwas

assaultedwitha ‘doubledisease’,fromwithoutby ‘astrong,crafty,pestilential enemie’ andwithin ‘withaMalignantputridfeverinherowneblood’.²²Other puritanministers,suchasAnthonyTuckney,invokedtheimageoftheruleras physiciantogentlychidethoseinauthority,includingtheKing,tousetheirpower tohealtheinfirmitiesofthebodypolitic.InasermondeliveredbeforeParliament inAugust1643hethusobserved,ontheauthorityofGalen,thatinformertimes kingsandemperorsprescribedmedicinestotheirsubjectswiththeirownhands. Thecontemporaryresonanceofthisallusionwasnotlostonhisaudience,forhe wentontosaythat ‘althoughallMonarchesnowcurenottheKingsevil;yetall bothKingsandMagistratesshould,asoccasionandneedshalbe,havebothskill andwilltocuregreaterandmoredangerousdiseasesinthebodyPolitick ’ . AlludingtothetimeoftheprophetIsaiah,heconcluded,somewhatcaustically, ‘thatinthosetimesalthoughRulersandHealersweretwowords,yettheymade accountthattheyshouldbeeanddoeoneandthesamething:andsoeindeedif Godbewiththem,theybothareanddoeaccordingly ’.²³

Onoccasions,godlyministersostensiblyonthesamesideinvokedtheanalogy ofthebodypolitictoarticulateandsupportconflictingcoursesofaction.Thiswas apparent,forexample,atthecriticalmomentinearly1645whenthe ‘peaceparty’ inParliament,supportedbytheirScottishallies,madeonelastditchattemptto cometotermswiththeKingatUxbridge.Thepeacenegotiationsheldthere, however,provedhighlycontentiousandwereopposedbymanywithin Parliamentwhowishedtoseethewarfoughttoamilitaryconclusion.Thetwo opposingviewswereadumbratedintwocontrastingsermonspreachedat Uxbridgeonconsecutivedays.The first,afastsermondeliveredbyJohn Whincop,setouttheaimsandwishesofthe ‘peaceparty’,whohopedtoseea truceandanegotiatedsettlementwiththeKing.Accordingly,Whincopcautioned MPs,whomheaddressedas ‘ourPhysitians’,toproceedslowlyandcarefullyinthe cureofthenation, ‘assickapatient ...as everanyhad,apoorekingdome,allina desperatemalignantburningfever’.Animmediatecurewasoutofthequestion, butifthelifeofthepatientwastobesaved,Whincopassuredhislisteners,thenit mustproceedwithoutfurtherbloodletting.TheTreatyofUxbridgethusresembledapotentialdeath-bedscene:

Inallhumanepossibility,thisisoneofthelastgentlehealingmedicinesthatever thisLandisliketohave:purg’d...andbloudiedithathbeenoftbefore.How manyouncesshallIsay,orpounds?Howmany flouds,howmanyriversnay,seas ofbloudhathpooreEnglandlostwithinthese fiveyears?(itisnowgrownfaint, veryfaint(Godknows)agoodcordiall,anhappieAccommodation,werethe likeliestPhysickintheWorld,tosetitrightagain’.²⁴

Incontrast,thefollowingdaythePresbyterianChristopherLovepreachedat Uxbridgeasermonradicallydifferentintone,butonethatnonethelessresorted