The Fragments and Periochae

Edited with an Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by

D. S. LEVENE

Volume I

Fragments, Citations, Testimonia

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© D. S. Levene 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023933546

ISBN 978–0–19–888853–6 (Pack)

ISBN 978–0–19–287122–0 (Vol. I)

ISBN 978–0–19–287123–7 (Vol. II)

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Gabrielle and Aurelia

Preface

Zu kurz, zu lang—wer ein End’ da fänd! Wer meint hier in Ernst einen Bar?

Auf ‘blinde Meinung’ klag’ ich allein: sagt, konnt’ ein Sinn unsinniger sein?

Too short, too long, who could find an end there! Who seriously thinks there’s a ‘Section’ here? But my sole complaint is ‘obscure sense’: Tell me, could a meaning be more meaningless?

Richard Wagner, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Act I

Even by the eclectic standards of classical commentaries, this commentary, on what one may roughly refer to as the ‘para-Livian’ material surviving from antiquity (the summaries, the fragments, and, in addition to those, all other places where Livy is explicitly cited or mentioned by name), is eccentric.

A small part of its strangeness comes from its origins: this is a project which, albeit in a very different form, was begun well over fifty years ago. Robert Ogilvie, then Fellow and Tutor at Balliol College, Oxford, was commissioned by Oxford University Press to produce an Oxford Classical Text of Livy Books 41–45, along with the fragments of the lost portions of Livy’s works, in collaboration with A. H. McDonald. Before Ogilvie’s untimely death in November 1981 he had produced a full text and apparatus of the fragments, but neither he nor McDonald appears to have made any progress with the remainder of the work. Ogilvie’s material was passed to Christopher Pelling, who agreed to take on the project in collaboration with Michael Crawford. The plan to include Books 41–45 fell by the wayside, not least because of the superlative Teubner edition of those books produced by John Briscoe in 1986, which seemed (and seems) unlikely to be superseded, since those books depend on a single manuscript. Instead, the idea emerged to combine the fragments with an edition of the Periochae, and also of Obsequens and the Oxyrhynchus Epitome, thus assembling all the evidence for the ‘lost books of Livy’. In 1992 Pelling and Crawford convened in Oxford a seminar of scholars of Roman historiography, of whom I was one, which considered various issues which such an edition needed to address; one conclusion that had emerged by that point was that the problems raised by these texts were sufficiently severe that more annotation and commentary would be required than could be contained within the standard format of an Oxford Classical Text.

Following that seminar, however, little systematic work was done on the edition, since both Pelling and Crawford had a large number of other commitments. After Pelling’s appointment to the Regius Professorship of Greek in Oxford in 2003, he felt that it was unlikely that he would be able to do a large-scale project on a Latin text for the foreseeable future. For that reason, he approached me and invited me to take it over; with Crawford’s agreement, I inherited the material. I began working on it in the summer of 2011.

My original plan was to reproduce Ogilvie’s text and apparatus of the fragments, but to supplement it with a commentary, and to add my own text and commentary on the Periochae and the other summaries. Dr Ogilvie’s wife and daughter very kindly gave me permission to make use of his work as part of my edition. However, as I continued to work with the material, I found myself regularly disagreeing with Ogilvie’s choices, both textual and with regard to the selection and identification of ‘fragments’; under those circumstances it made little sense for me to use his text and apparatus. Moreover, the one part of Ogilvie’s material which was actually published (albeit posthumously), namely his edition and brief commentary on the palimpsest fragment of Book 91 (Ogilvie (1984)), needed to be completely re-edited using the spectacular digital images of the manuscript (in both regular and ultraviolet light) produced by the Vatican since his time. I remain, however, very grateful to Dr Ogilvie’s family, since his notes and other material were of immense help to me as I formulated my own edition, and also to Professors Pelling and Crawford, who likewise gave their working materials to me.

One major change I made to the project I inherited was the decision to add to the fragments and the summaries all other ancient references to Livy, both general references to his work and its reception, and specific references to the surviving books. I have long been of the belief that one cannot make sense of the fragments of the lost portions of an ancient author without a close examination of the citations and references to the surviving portions, which provide the essential context to the way in which those ‘fragments’ are preserved. Accordingly, I decided early on that this project would include all of that material. This edition, therefore, not only treats the ‘lost books of Livy’, but gives as complete a picture of his ancient reception as I have been able to assemble.

This summary of the history of the project should alone be enough to make it clear why this edition is something of a baggy and amorphous monster; but the bulk of the bagginess (and indeed the monstrosity) is the consequence of a number of other choices that I made in the course of writing it. A full commentary (both literary/linguistic and historical) on the fragments was a major desideratum, since that was the core of the project and had never been done previously. There was clearly no need for commentary on the other references to Livy to be anything like as full: if an ancient author accurately refers to a surviving book of Livy, there would appear to be little need for commentary at all, at least from the

perspective of understanding Livy (there might be need for commentary with regard to that author’s own work, but that would be a different project altogether). But a substantial portion of the ancient citations of the surviving books are to a greater or lesser degree inaccurate, and in those cases enough commentary needs to be offered to draw attention to and explain the inaccuracy, since this may well have a bearing on the accuracy or otherwise of comparable references to the lost books.

As for ‘testimonia’ to Livy’s life, work, and reception, it has long been commonplace in editions of ‘fragments’ to eschew commentary on those altogether; but I regard this as an unfortunate practice, since such testimonia not infrequently offer interesting understandings of the reception of the author, and many of them are not transparent in what they tell us about it.

Accordingly, I offer commentary (albeit usually only brief) on over half of the citations of the surviving books of Livy, and also, at a slightly greater length, on around two-thirds of the Testimonia.

The commentary on the Periochae is more variable still. There is a major distinction between the commentary on the parts of the Periochae where Livy’s original text survives, and those parts where it does not. With the latter, I offer a full historical commentary alongside linguistic and literary analysis (I will say more about the nature of that historical commentary below). Where Livy’s original text survives, however, there seems to be little point in offering historical analysis—a reader interested in the history should be reading Livy and commentaries on Livy, not the Periochae and commentaries on the Periochae except in those (not infrequent) cases where the Periochae provides a version of the history at variance with Livy’s own. Where the Periochae’s version is essentially the same as Livy’s, I confine my commentary to linguistic and literary questions, examining both the nature of the author’s choices (i.e. what elements from Livy to select for his summary) and his manner of compressing an episode into a brief notice.

This means that there are some places where the change in the manner of commentary may feel abrupt. This is most obvious in the transition from surviving to lost Livy in Books 10–11, and then back to surviving Livy in Book 21; but it is even more jarring in the commentaries to Books 41 and 43, where a substantial portion of Livy’s original text is lost, and the Periochae becomes a major source both for what was in those books and for the historical events they related. The commentary in those books lurches between the literary and the historical in a way that looks puzzling if it is not appreciated that it correlates to the gaps in Livy’s text.

The nature—and length—of my historical commentary on those parts of the Periochae corresponding to the lost books may also occasion some surprise (and perhaps discomfort). The actual narrative of the Periochae is extremely jejune: my historical commentary is frequently the opposite. What is more, much of the commentary has a somewhat old-fashioned feel, revisiting basic factual questions Preface

Preface

about dates, places, times, and events which do not tend to be the primary interest of most contemporary classicists (myself included). My rationale, however, is very simple. The bulk of the narrative of the Periochae offers bare and ostensibly unadorned factual material about Roman history. A commentator, accordingly, needs to focus on that factual material. This is unproblematic and can be done suitably succinctly when the facts are uncontested. However, with almost all the material corresponding to the Second Decade of Livy (and many of the other decades also), our sources are scanty and the historical information they purport to provide can and should be questioned and challenged. The alternatives I had were (a) to announce ex cathedra the ‘correct answer’ to the historical questions, or (b) to refer readers to someone else’s discussion leading to that ‘correct answer’ (even if that discussion is not necessarily sufficiently nuanced), or (c) to show explicitly the evidence for the different options, along with my own reasoning as to which the most probable answer is. (c) seems to me both the most helpful and the most intellectually honest approach, although also the one which requires the greatest prolixity.

Hence readers will find in my commentary extended discussions of such old chestnuts as the existence of the Treaty of Philinus (I don’t believe in it, though I also don’t believe that all the arguments against it are equally valid, and I have done my best to set out clearly and fairly the arguments on both sides) or the timing of the embassies between Pyrrhus and Rome. Readers will also, perhaps more importantly, find many discussions of questions which should be old chestnuts, but where the questionableness of the information has been forgotten and one version has unjustifiably become canonical. An example is the date of the Lex Hortensia, which was probably not ‘287 bc ’, nor can it even be described properly as ‘c.287 bc ’, although virtually every scholarly reference to it in the last seventy years has characterized it using one or another of those formulations. And the fact that I approach the material via a comparison of the narrative of the Periochae and other parallel narratives allows some reconsideration of questions that are of greater interest even nowadays, such as the nature of the (alleged) social struggle that led to the Lex Hortensia being passed in the first place.

I should also briefly comment on the linguistic data I provide in the commentaries. On many occasions, I refer to some Latin phrase or usage as ‘unparalleled’ or ‘unparalleled except for X’. Despite my authoritative rhetoric, it is often the case that I cannot be sure that this is true, although I have done my best to ascertain it. I have primarily obtained the data from searchable online databases: above all the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) Classical Latin Texts (https://latin.packhum. org/index) and the Library of Latin Texts (https://www.brepols.net/series/llt-o), along with (where available) the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (https://tll.degruyter. com/). All of these have their weaknesses: for example, the Library of Latin Texts has a far more comprehensive set of texts than the PHI database, but is far more restricted in the kinds of searches it permits. Moreover, there are Latin texts from

antiquity that currently appear in neither database, though they have usually been sampled by the TLL. This paragraph should therefore stand as a universal asterisk, qualifying all my dogmatic statements about uniqueness or near-uniqueness in Latin usage.

As usual with projects of this size, I have received support from many organizations and individuals. In 2013 I held a Visiting Fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, and a Global Research Initiatives Fellowship at NYU Berlin; in 2017–18 I was a Visiting Scholar at NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. I am grateful to all of these for their support and hospitality. Much of the edition was produced over successive summers in Rome, where I primarily worked in the superb library of the École Française de Rome, and I would like to thank all of the staff there for their help. I would also like to thank Federica Orlando, who enabled me to gain access to the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana at a time when the Virus looked likely to deprive me of it at a crucial moment.

One person stands out in the assistance that he has provided: Tony Woodman has read, and commented in painstaking detail on, every page of this book, and he has constantly been available for consultation on all questions. I cannot adequately express my gratitude for all he has done. Jane Chaplin and Jim Zetzel have also read substantial portions of the draft manuscript, and I am most grateful to both of them for their acute and critical comments. Other people I have consulted at various times include Roger Bagnall, the late Larissa Bonfante, John Briscoe, Claire Bubb, Eva von Dassow, Andrew Dufton, Robert Kaster, Vanessa Léon, Michael Peachin, Lori Peek, Jeremia Pelgrom, Jonathan Prag, Calloway Scott, David Sider, Jonathan Valk, and Martin Worthington; I greatly appreciate their help. In addition, I have given papers based on this material at New York University (both the Classics department and ISAW), All Souls College, Oxford, the Institute of Classical Studies, London, Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, Brown University, the University of Southern California, the University of Colorado, Boulder, and the Annual Meeting of the Society for Classical Studies; in all cases I am grateful to those in the audience for their comments and criticisms.

My wife and daughter, Gabrielle and Aurelia, have lived with this book as long as I have: indeed, for Aurelia it has formed the backdrop to her entire life. I am immensely grateful to them for their endless patience and support through all the vicissitudes of its writing, and I dedicate the book to them.

Abbreviations

Introduction

ii.

Abbreviations

AE R. Cagnat et al. (eds), L’Année épigraphique (Paris, 1888– ).

BarrAtl R. J. A. Talbert (ed.), The Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Carandini, Atlas A. Carandini with P. Carafa (eds), The Atlas of Ancient Rome (tr. A. Campbell Halavais, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

CIL T. Mommsen et al. (eds), Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1853– ).

CNNM J. Mazard (ed.), Corpus Nummorum Numidiae Mauretaniaeque (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1955).

CS W. W. Hallo and K. L. Younger (eds), The Context of Scripture (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

De Sanctis G. De Sanctis, Storia dei Romani (2nd edn, Florence: La Nuova Italia, 1956–69). [Page numbers of 1st edn in square brackets.]

Degrassi, A. Degrassi (ed.), Inscriptiones Italiae XIII, 2 (Rome: La Libreria dello Fast. Ann. Stato, 1963).

FGrH F. Jacoby (ed.), Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker (Berlin: Weidmann, 1923–30; Leiden: Brill, 1940–58).

FRHist T. J. Cornell et al. (eds), The Fragments of the Roman Historians (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Funari R. Funari (ed.), Corpus dei papiri storici greci e latini. Parte B. Storici latini. 1. Autori noti. Vol. 1. Titus Livius (Pisa: Fabrizio Serra, 2011).

H-S J. B. Hofmann and A. Szantyr, Lateinische Grammatik: Syntax und Stilistik (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1965).

IGRRP R. Cagnat et al. (eds), Inscriptiones Graecae ad Res Romanas Pertinentes (Paris: E. Leroux, 1906–27).

I. Ilion P. Frisch (ed.), Die Inschriften von Ilion (Bonn: Habelt, 1975).

ILLRP A. Degrassi (ed.), Inscriptiones Latinae Liberae Rei Publicae (2nd edn, Florence: Biblioteca di studi superiori, 1963–5).

ILS H. Dessau (ed.), Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae (Berlin: Weidmann, 1892–1906).

K-S R. Kühner and C. Stegmann, Ausführliche Grammatik der Lateinischen Sprache: Satzlehre (Hanover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung, 1914).

LSJ H. G. Liddell, R. Scott, and H. S. Jones, A Greek–English Lexicon (9th edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940).

LTUR E. M. Steinby (ed.), Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1993–2000).

Mommsen, StR3 T. Mommsen, Römisches Staatsrecht (3rd edn, Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1887–8).

MRR T. R. S. Broughton with M. L. Patterson, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (New York: American Philological Association, 1951–86).

OLD Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968–82).

ORF3

H. Malcovati (ed.), Oratorum Romanorum Fragmenta Liberae Rei Publicae (3rd edn, Turin: G. B. Paravia & C., 1953).

Pinkster H. Pinkster, The Oxford Latin Syntax (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015–21).

PIR1

PIR2

E. Klebs et al. (eds), Prosopographia Imperii Romani. Saec. I, II, III (1st edn, Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1897–8).

E. Groag et al. (eds), Prosopographia Imperii Romani. Saec. I, II, III (2nd edn, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1933–2015).

RE A. E. von Pauly et al., Pauly’s Real-Encyclopädie der classische Altertumswissenschaft (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1894–1963).

RRC M. H. Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

Rüpke, FS J. Rüpke and A. Glock, Fasti sacerdotum: A Prosopography of Pagan, Jewish, and Christian Religious Officials in the City of Rome, 300 bc to ad 499 (rev. edn, tr. D. M. B. Richardson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

SIG W. Dittenberger (ed.), Sylloge Inscriptionum Graecarum (3rd edn, Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1915–24).

SVF H. F. A. von Arnim (ed.), Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta (Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1903–24).

TLL

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1890– ).

W-M W. Weissenborn, H. J. Müller, and O. Rossbach, Titi Livi: Ab Urbe Condita Libri (Berlin: Weidmann, 1880–1924, latest edn of each volume reprinted 1965).

Woodcock E. C. Woodcock, A New Latin Syntax (London: Methuen & Co., 1959).

Abbreviations of titles of journals are taken from L’Année Philologique. Abbreviations of ancient texts and authors are taken from LSJ for Greek texts and TLL for Latin, with some adaptations: notably Per. is used as the abbreviation for the Livian Periochae (with P. as its author), and EpOxy to designate the Oxyrhynchus Epitome of Livy. Cassius Dio is abbreviated to Dio, Jerome to Jer., Josephus to Jos., Xenophon to Xen. Also, particular works are sometimes identified by title (for example with Dionysius’ Antiquitates Romanae or Plutarch’s Moralia or Seneca’s Dialogues or Claudian or Priscian) where LSJ or TLL prefers to leave them either unspecified or specified only by number: in those cases I have created my own (I hope reasonably clear) abbreviations for the titles. Conversely, Florus’ so-called Epitome and Orosius’ Historiae Adversus Paganos are abbreviated to ‘Flor.’ and ‘Oros.’ respectively, with the title omitted.

Introduction

i. Introduction

The texts that I have collected for this project represent every1 reference to Livy made between his own time and the end of classical antiquity, which I have (largely—though not entirely—arbitrarily) designated as ad 650; in addition I include later references to him in a handful of cases where the citing author appears to have access to otherwise unattested information from the earlier period. The object is to provide as complete a picture as I can of the evidence both for the three-quarters of Livy that has been lost and for his ancient reputation—even when (as sometimes appears to be the case) that reputation is not based on actual acquaintance with his text—as well as a sense of the way that he was used and read by later writers.

It should not, of course, be assumed that the material here is all that could be adduced for these ends: in particular, there are many places where later historians can be plausibly argued to have employed Livy as a source without citing him explicitly, and also many places where we can detect more or less secure allusions to or adaptations of Livy’s language. But the boundaries of those are fuzzy and contentious. The identification of historical sources has long been a matter for controversy in all but the most clear-cut cases, and the identification of allusions scarcely less so. Moreover, to include even the most secure instances would multiply the scope of this already long project many times over. It is, admittedly, improbable that the references to Livy by name can be used as a simple proxy for the manner in which he is used in the cases where he is not named; but at the same time a comprehensive study of the former is likely to be the closest we will ever come to solid answers about the general reputation and use made of Livy in antiquity.

One class of texts that I am studying in this project consists of the texts which explicitly summarize Livy; three of these survive, one (the Periochae) almost complete, the other two far less so. I shall be discussing these in the Introduction to Volume II. In addition, and to be considered as falling under the same heading, is the Liber Prodigiorum of Julius Obsequens. This does not explicitly represent

1 At least as far as I have been able to discover them. My knowledge of the extensive surviving patristic literature in particular is less good than it should be, and databases and search engines are sometimes less comprehensive than one might expect. I do not imagine that I have overlooked many references to Livy, but I would not be especially surprised to discover that there are one or two which I have failed to catch. I would be grateful for any supplements that readers can send me.

itself as derived from Livy, but a comparison of the places where Obsequens’ text overlaps with Livy shows conclusively that Obsequens has excerpted his material from Livy. Since we do not appear to have the beginning of Obsequens’ work, it is a reasonable hypothesis that he would have acknowledged the relationship there, and even if he did not, the connection is so clear as to set it on a different level from any other text that has been assumed to depend on Livy. One may, for example, contrast Florus, whose MSS describe his work as a Livian epitome (T 50), a claim which does not survive even a relatively cursory comparison between Florus (who never mentions Livy in the body of his work)2 and the surviving books of the Ab Urbe Condita; for further consideration of why Florus might, despite this, have been thought of as an epitome of Livy in later antiquity, see below, xxi–xxii. Hence Florus, and other summary historians of the imperial period whose works show some affinities with Livy’s narrative but are not overtly purporting to summarize him, such as Eutropius or the De Viris Illustribus, have been excluded from consideration, except for comparative purposes.

I have divided other references to Livy into three broad categories, which I refer to as ‘Fragments’, ‘Citations’, and ‘Testimonia’.3

(i) Fragments are perhaps the least surprising category, not least because they have been collected several times by previous scholars. These consist of allusions to the lost parts of Livy—Books 11–20 and 46–142. As is usual with collections of fragments from historical authors (e.g. FGrH, FRHist), I have included all allusions which describe some aspect of Livy’s narrative, not only those which purport4 to quote him verbatim (which consist of only a small minority of these ‘fragments’), and also the fragments from Livy’s writing on rhetoric. I have also included (under the heading of dubia aut spuria) a number of places where it is asserted by the alluding author (or at least by the MSS of that author) that a quotation derives from Livy, but where that is in fact very unlikely to be true.

2 See, however, Hudson (2019), arguing that Florus repeatedly alludes covertly and indirectly to his own brevity and so implicitly contrasts himself with large-scale Latin historiography of the Republic, Livy above all.

3 Note to the reader: these labels, and the divisions between the different categories, do not exactly correspond to those used in other fragment collections. This should not be taken to mean that those other collections are flawed in the modes of selection and division they adopt. The division here is very specifically designed to be useful in this particular project, and to enable me to include all references to Livy in a way that is transparent to the reader while remaining methodologically consistent: other collections are used for other purposes and legitimately adopt different criteria. For general discussion of the concept of a ‘fragment’, and how it has varied in different contexts, see the essays in Most (1997). With regard to the issues raised by historians in particular, Schepens (2000) is especially useful; more recently a powerful and thoughtful set of discussions is found in the ‘Working Papers’ by Pelling (2014), Marincola (2014), Pitcher (2014), and Malloch (2014) (all derived from a panel on the then newly published FRHist at the Classical Association Annual Conference in Nottingham organized by Catherine Steel).

4 I emphasize ‘purport’: from our perspective, ancient habits of supposedly ‘verbal quotation’ often include deliberate as well as accidental alterations to the original (see esp. Whittaker (1989)).

I have, however, excluded from this section references to the general Tendenz of Livy’s work which are not easily pinned down to a single section, although some of these have been categorized as ‘fragments’ in the past;5 these are listed under ‘testimonia’ (see below).6 For similar reasons, I have excluded under this heading the places (mostly from grammarians) which comment on broad aspects of Livy’s word-usage, even when that particular usage is not attested in the surviving part of his work.

(ii) Citations are references to the surviving books of Livy: they are, in effect, passages that would have been considered ‘fragments’ under the definition above, had they come from lost books rather than surviving ones. Except when they are included in a textual apparatus for the purposes of textual criticism, such passages are ignored by most scholars, both in the case of Livy and in those of other ancient authors whose texts are partly but not wholly lost. But they give an essential context to the ‘fragments’: they allow us to see the kinds of distortions that arise with the different citing authors by comparison with Livy’s original text, and so we can assess more precisely how and where references to the lost books may have been similarly distorted. Combining ‘fragments’ with ‘citations’ also gives us a more comprehensive picture of how much Livy was and was not being read in antiquity, and which parts of his work attracted attention.

(iii) Testimonia comprise all references to Livy in antiquity which do not qualify as ‘fragments’ or ‘citations’. They fall into three broad categories. The first is the most traditional kind of ‘testimonium’: factual information about Livy’s life (listed in a rough chronological order of his career) and work which does not offer the kind of specificity about particular parts of the text that is found in the ‘fragments’ and ‘citations’. The second, and largest, group is later references to Livy, either in terms of his general reputation, or by someone who mentions reading or owning his text: these are listed in chronological order of the citing authors. The third group is linguistic; authors (often grammarians) who mention aspects of Livy’s regular vocabulary choices without reference to any particular text in which he uses the words.

These three groups between them, along with the various epitomes, comprise every reference to Livy in ancient sources. The first thing to note, and perhaps the most surprising, is that they are relatively few in number. A precise count is difficult, because it depends on the criteria used to identify a ‘different’ citation or fragment or testimonium.7 But, with that said, we can at least provide a range.

5 For example, both W-M and Jal (1979) treat as a ‘fragment’ the famous reference to Livy’s warmth towards Pompey in Tacitus’ speech of Cremutius Cordus (Ann. 4.34.3 = T 7). It is very hard to see why this should count as a ‘fragment’ when (for example) Hist. Aug. Prob. 2.3–7 (T 32) does not: my suspicion (perhaps unjustified) is that the inclusion was based less on methodological consistency and more on the scholars’ unwillingness to omit so famous a passage from their collection.

6 For a similar procedure cf. FRHist 1.13–14.

7 If Quintilian refers to Livy, and then Charisius refers to Livy, not from any independent knowledge of Livy, but simply copying Quintilian, does that count as two references or one? When two

There are between 81 and 91 fragments of the 107 lost books of Livy, excluding the three preserved directly on parchment and also the ‘dubia aut spuria’, but including the four (or five) fragments of the rhetorical works. There are between 81 and 98 ‘citations’ of the thirty-five surviving books of Livy. There are between 62 and 68 references to Livy of the sort I have characterized as ‘testimonia’, excluding the three inscriptions that probably or possibly refer to Livy and his family, and counting the subscriptions to the MSS of the First Decade (T 37) as a single ‘testimonium’. In other words, there are between 225 and 257 references to Livy in all of post-Livian literature. To give some points of comparison, there are over 550 surviving fragments of the five books of Sallust’s lost Histories, to add to the references to his monographs and many other allusions to him as a writer. FRHist offers over 150 fragments and over 20 testimonia (based on the traditional definition of a testimonium, not the more expansive one I have used here) from the seven books of Cato’s Origines; ORF3 adds more than 250 fragments of Cato’s speeches.8 And this is not even to enter into the uncountably greater number of references in later literature to Virgil and Cicero, Horace and Ovid. The existence of so many summaries attests to a continued interest in Livy—he is not a writer who is overlooked for much of antiquity, in the way that (arguably) Tacitus was— but although he was not forgotten, he also does not appear to have been at the forefront of the minds of later writers to the same degree as Sallust, so often paired automatically with him.9 This requires some explanation.

One relatively simple explanation is that it is the product of a series of chances: certain kinds of texts which offer a large number of quotations from and references to earlier literature happen to have been written by people with little or no interest in Livy. Aulus Gellius, notoriously, does not make a single reference to him, and this is more probably the result of conscious omission than ignorance, since he quotes a story about a Paduan diviner which must have originated with Livy (see Gell. 15.18 with F 47n.); similarly, he is never mentioned by Macrobius. It is an annoying fact that Livy is almost entirely absent from the grammarians (with the important exception of Priscian, the single writer of any period with the most references to him); this is in part the result of his absence from the late antique classroom and also, no less importantly, the perceived lack of eccentricity in his Latin, at least by comparison with Sallust and his archaic predecessors.

separate scholiasts of Horace or Lucan cite the same passage of Livy, is that two fragments or one? When Lactantius mentions a story that combines material from two entirely separate passages from Livy, is that two citations or one? With all of these one could make a case for either version, depending what one is using the data for.

8 Admittedly there is some overlap, since Cato famously inserted some of his own speeches into the narrative of the Origines, and these are contained in both of the fragment collections.

9 Nineteen of the post-Livian references link him to Sallust; that can be increased to twenty if one notes the juxtaposition of Martial’s gift-epigram on Livy (14.190 = T 23) with that on Sallust (14.191).

But even that can only be considered a partial explanation. The second most prolific citer of Livy is Servius,10 who mentions him thirty-one times. But that number is dwarfed by Servius’ references to and quotations from Sallust, which number in the hundreds. Plainly it is neither an entrenched hostility to Livy nor a lack of linguistic relevance which generates the difference. Something discouraged writers from quoting Livy; and it is not hard to guess what that might be. The sheer length of Livy’s text—the same feature that led to his being so frequently abridged and summarized—was a major deterrent to achieving familiarity with the work, in antiquity as it is nowadays. Part of that was the basic economic difficulty of owning or gaining access to a text that in its complete form ran to 142 volumes (see further below); but the economy of time and attention was perhaps at least as important. Symmachus, a highly literate and literary man, who on his own account possessed a complete text of Livy (T 36), shows no sign in his published writings of ever having read any of it (Cameron (2011), 511–12).

Unlike Sallust, moreover, even those parts of Livy which could be separated into discrete and coherent sections (see below) are relatively lengthy, apart perhaps from Book 1, which, unsurprisingly, is by far the most cited part of his work.

Livy is thus a relatively unusual figure among surviving writers from Latin antiquity: an author who is repeatedly mentioned by later writers as one of the two canonical authors of a major literary genre, and yet whose readership is not commensurate with his reputation.11 It is accordingly likely that many of the references to Livy that we do have, like Symmachus’, are more in the manner of paying lip service to his cultural importance rather than showing actual acquaintance with his text or his writing.

Most notably, it appears probable that there was a vague assumption that all traditions of Republican history derived from Livy, whether or not those traditions were actually present in his text. This is, for example, the most natural explanation for Florus, Eutropius, and the De Viris Illustribus all at different times being spoken of as epitomes of Livy (TT 29, 48, 50, 52; cf. C 10), although none of them articulate their works in the same way as he does his, and even though all of them present non-Livian versions of history at innumerable points. It also explains how Servius in particular occasionally ascribes to Livy versions of Roman history that he does not in fact tell (CC 3, 6, 36); the same phenomenon is visible in some other citations from Livy, such as by Pompeius in his commentary on Donatus (C 12), and especially John Malalas (CC 13, 23). The same reasoning helps to explain why even the actual epitomes of Livy which survive, while

10 Here and elsewhere in the introduction ‘Servius’ includes not only Servius’ own commentary, but also ‘Servius auctus’ (a.k.a. ‘Servius Danielis’ or ‘DServius’), an early mediaeval commentary which rewrites Servius partly by fusing his text with elements of an older commentary, very possibly Donatus: cf. also F 5n.

11 Cf. Bessone (1977), 191–3, esp. 193: ‘La fortuna di Livio fu inversamente proporzionale alla conoscenza diretta della sua opera.’

explicitly articulating their narrative around Livian books (in this respect and in many others certainly far closer to him than Florus, Eutropius, or the De Viris Illustribus), regularly introduce details which are not present in Livy’s original text, but which are sometimes widespread elsewhere in the historical tradition. Livy and Republican history became effectively identified.

ii. Patterns of Citation

Citations of Livy are, naturally, not evenly distributed across his work, and, equally naturally, are concentrated in certain authors. This, notoriously, has the potential to lead to major misunderstanding: see above all the fundamental study of Elliott (2013), demonstrating how past scholars have been seduced by the patterns of quotations from Ennius by later writers into believing that they are somehow representative of Ennius’ actual work. Elliott shows that they are massively distorted by the particular interests of the citing authors and, accordingly, that Ennius’ own work may well have had entirely different interests and emphases.12

In the case of Livy, however, we have two alternative methods of assessing the overall run of his work which are not available for Ennius. The first, and most obvious, is the survival of a quarter of it intact, which can, as noted above, be used to check the reliability of the citations from that part, which can then, in principle, be extrapolated to citations by the same author of the lost portions. This is especially important, since there is a significant danger with a prose writer like Livy which does not apply to poets like Ennius (Schepens (2000), 6–7). With poetry the metre usually makes it uncomplicated to distinguish quotation from paraphrase, and to distinguish the poet’s own contribution from that of the citing author. Historians, as noted above (xviii), are more often paraphrased than quoted, which makes it still harder to demarcate the parts that are being cited from the citing author’s commentary or elaboration. The guidance offered by citations of surviving books is, accordingly, invaluable, although here too it can sometimes be difficult to parse.13

Even here, however, one needs some measure of caution. One aspect of Livy’s surviving work which is less often remarked upon than it should be is its extreme variability: the Third Decade is very unlike the First, the Fourth is like neither,

12 For a survey focusing on fragments of historians, far briefer and less detailed but reaching comparable conclusions, see Brunt (1980).

13 Here too Brunt (1980) provides a useful survey. The difficulties can be seen in the case of Athenaeus, who repeatedly cites surviving Greek historians as well as lost works; but there is a good deal of controversy among scholars about how we should assess his reliability overall, about the kinds of markers that might separate reliable citations from less reliable ones, and about the ease of extrapolation from the surviving works to lost ones: for different views, see e.g. Ambaglio (1990), Pelling (2000), Lenfant (2007), Maisonneuve (2007), Olson (2018). See also Lenfant (1999) for a survey of citations of Herodotus by a variety of authors.

and even the Fifth shows some surprising points of difference from the Fourth.14 It is, accordingly, intrinsically probable that Livy’s lost books, especially (but not only) those that relate to events of his own lifetime, will show significantly different features from his surviving work. Naturally, Livy, like any writer, has substantial elements of consistency even across the parts of his work that vary in other respects; but the danger of extrapolation from the surviving part of his work to that which is lost considerably outweighs the danger of falsely assessing the work by the seventy or eighty references to or quotations from the lost portion.

A second check, perhaps even more important, is the Periochae. This provides us with a sketch of the contents of the lost books, enabling us to see the broad run of events represented and their distribution across Livy’s work; in a very crude and rough way, we can get a reasonably reliable sense of Livy’s emphases, at least with regard to the amount of space that he allotted to particular periods of Roman history. But the potential for distortion here is even greater. The author of the Periochae has particular interests and emphases of his own, which are demonstrably not the same as Livy’s; what is more, he does not always provide an accurate representation of Livy’s version of history, not infrequently adding material that was absent from Livy, or substituting other versions of history for Livy’s own (see the more detailed discussion in the Introduction to Volume II). But combining the evidence of the Periochae with the impressions of Livy’s interests and manner in his surviving work gives us a far greater and more useful context for assessing the lost portion than we have for almost any other fragmentary author, although, even with that taken into account, the gaps in our information are massive, and the level of uncertainty about Livy’s manner of treatment is high.

Fragments are, accordingly, vastly less important for Livy than for Ennius in allowing us to determine the overall shape of his work, but they do have the potential to supply a more finely grained sense of particular details than we can get from any other source, and a determination of how reliably they are likely to reflect his text is immensely useful. Two authors between them contribute around half of the citations and fragments, namely Priscian and Servius. Both of these show distinctive patterns.

Priscian’s references map relatively closely onto the surviving books—more closely, indeed, than the bare numbers might suggest. Of his fifty-one quotations, forty-one derive from the surviving books, and of the ten fragments from lost books, five relate to a single issue, namely illustrating the declension of African names ending in -d in Books 112–14 (the only issue concerning which Priscian cites these books at all). It is plausible to assume that Priscian is not citing these five passages directly from a text of Livy, but from the collection of some earlier grammarian, since, had he known those books himself, one would have thought he would have collected other matters of interest from them. The citations from

14 I demonstrated this in Levene (1993); cf. also Levene (2010), vii–viii.

the surviving books are spread fairly evenly across them: eleven from the First Decade, twelve from the Third, seventeen from the Fourth (five of which are from his work De Figuris Numerorum, and hence relate specifically to numbers). There is also one from the Fifth, which is more surprising—it is in fact the only surviving citation of Books 41–45 (see below). In these cases, however, there is no particular reason to doubt that Priscian knew the text at first hand.

As for the remaining five fragments from the lost books, here too there is no reason to infer simply from their content that Priscian is citing them at second hand: there is no particular pattern with regard to the points for which they are cited. But the distribution across books raises some suspicions: they derive from Books 13, 17, 56, and 118, while one where the book number has been corrupted (F 68: see ad loc.) may be tentatively assigned to the Second Decade. This might suggest that Priscian knew the Second Decade directly, but the very uniqueness of the citations of Book 56 and 118 (especially the former, which is a part of the work otherwise almost forgotten in the later tradition: see below) suggests that they are less likely to come from his own readings.

As for Priscian’s accuracy, the vast majority of his forty-one quotations from the surviving books are identical or very close to Livy’s transmitted text, though occasionally he slightly alters the wording or omits words extraneous to the point he is citing Livy to illustrate (he also sometimes appears to be using a text of Livy that is less reliable than our own). There are, however, two exceptions to this (CC 74, 80), both in the same chapter of Priscian, both taken from Livy Books 39–40, and both of which seriously misrepresent his text. It is unclear why Priscian should be so unreliable here and only here, but it is reasonable to assume that the quotations from the lost books (even if, as argued above, most of them are tralatician) are more likely to reflect the reliable majority of his work than the unreliable minority.

Servius’ thirty-one15 citations form a very different pattern. Nearly half—thirteen—come from Book 1 alone, but the remaining eighteen show no particular sign of matching the books’ survival: only six come from extant books (four from the remaining books of the First Decade), as against twelve from the lost books. Of those twelve fragments, four cannot be identified by book, and the remaining eight come from just three sections of Livy’s work: two from the 90s, one from (probably) Book 109, and five from the Second Decade (cited by Servius more often than any other part of Livy except Book 1).

This pattern is best explained from Servius’ interests rather than his reading. Unlike Priscian, whose interests are purely linguistic, in the great majority of instances Servius cites Livy either in order to supply a background narrative to historical figures or historical events which Virgil referred to in passing

15 This figure counts as separate citations the three occasions when Servius twice cites the same passage of Livy (CC 4, 8, 9: all passages in Book 1). If those are considered one citation each, then Servius cites Livy twenty-eight times in total, ten of which are from Book 1.

(sometimes correcting Virgil’s history in the process), or else, along related lines, to provide antiquarian information concerning something that Virgil mentions obliquely; only in a minority of cases (CC 31, 45, FF 69, 73, 76) does Servius cite Livy on a linguistic matter. This explains the focus on Book 1, the part of the work where Livy’s narrative intersects most obviously with Virgil’s, and also the cluster from Book 16, where Livy recounted the foundation of Carthage.

However, with all of Servius’ citations, there must be some suspicion that he does not know the text of Livy at first hand. Admittedly, only a handful of his citations are demonstrably unreliable, but one is spectacularly so—Livy could not possibly have recounted Claudius Pulcher’s failure at the battle of Drepana in anything like the form Servius claims he did: Servius has manifestly conflated Claudius’ story with that of his consular colleague L. Julius Pullus (see F 12n.).

There are also a few cases where Servius attributes to Livy recognizable versions of Roman history, though not the ones which Livy himself happened to tell (CC 3, 6, 36nn.)—these cases, as noted above, are part of a broader pattern of linking Livy to all traditions of early Roman and Republican history. But all of them suggest that, at least some of the time, Livy is not being cited at first hand: Servius (or Donatus, in the case of the citations deriving from ‘Servius auctus’) clearly drew material from earlier Virgilian commentaries, and in that process some of the material was distorted.

It can hardly be proved that Servius did not know Livy himself, and he sometimes purports to quote his words verbatim (though not, as it happens, with any of the citations from the surviving books). And even with those references that are tralatician, that does not mean that they do not represent Livy accurately: given that the great majority of the citations from the surviving books are fair reflections of Livy’s text, it is not unreasonable to extrapolate similar trust to the fragments from the lost books, at least in those cases where we have no independent reason to assume that some form of misrepresentation has taken place.

The third most prolific citer of Livy is Plutarch, who cites him fifteen times,16 though only in limited portions of his work. He mentions Livy twice in the Moralia, both with relation to a single part of his work, namely the opening chapter of Book 6 (CC 32–33)—although, interestingly, Plutarch draws on two very different points from that chapter. Seven of the Lives cite Livy: Camillus, Marcellus (including the comparison with Pelopidas), Flamininus, Cato Major, Sulla, Lucullus, and Caesar. One very revealing moment, however, comes with Marcellus, where Plutarch’s citations are highly inaccurate, and one of them (C 53) is demonstrably derived not from Livy’s own text, but an early epitome (see ad loc.; also Volume II, xii–xiv); the citation in Camillus (C 30) also presents a version of the history which is not found in Livy, but could easily derive from an

16 Or fourteen times, if the two separate citations from Livy 39.42.6–12 (C 75) are treated as a single one.

epitome. This does not mean that Plutarch never consulted Livy at first hand— the two citations from Book 6 concern points of detail that seem extremely unlikely to have been included in an epitome, and the extended account of the Paduan diviner in the Caesar (F 47), with Livy mentioned as an acquaintance of the protagonist, likewise appears to suggest direct knowledge of Livy’s version. But it should not be assumed that Plutarch’s remaining references to Livy are either reliable or based on a first-hand reading of his text.

The last source for a significant number of citations of Livy’s text is the various scholia to Lucan, which offer eleven (counting F 46, which appears in different wording in two separate scholia, as a single citation). All of them offer historical background or corrections to matters that appear in Lucan’s text, sometimes purporting to quote Livy verbatim (their interest is presumably related to the fact that Lucan derived much of his information from Livy,17 so a comparison between their texts is especially revealing). Since (unsurprisingly) none of these citations refer to the surviving books, there is no direct check on their reliability. A few show elements of garbling (FF 31, 46a, 48, 55); and in one case (F 42) an overlap with the language of Orosius in what appears to be a summary of a wider portion of Livy’s text suggests that the scholiast may be deriving its information from an epitome. But the garblings are mostly minor (F 48 is an exception); on the whole, we may tentatively assume that these scholia (or, more precisely, the commentary traditions on which these scholia are drawing) depend on a solid knowledge of the relevant portions of Livy’s text.

No other author cites Livy more than seven times, and so it is hard to discern any patterns to their citations. Sometimes (e.g. John Malalas) it is obvious that the author has no direct knowledge of Livy; in other cases, particularly with the writers from the first and early second centuries ad , it is either a reasonable supposition or a near certainty (as in the case of the elder Seneca’s quotations of Livy on the death of Cicero: FF 61–62) that they are depending directly on his text. But all of these need to be considered on a case-by-case basis, as I have done in the commentary.

Putting all of these citations and fragments together, however, allows us to see patterns of a different sort. The surviving books of Livy are on average cited more than the lost books, but even that is not entirely consistent. Book 1 is cited far more than any other (22–25 times, depending how one counts the double citations by Servius: see above), which is hardly surprising; leaving that book aside, there are approximately equal numbers of citations from the rest of the First Decade (22), the Third Decade (20), and the Fourth Decade (21–22 times, depending how one counts the double citations by Plutarch in C 75)—but that is only because Priscian has a surprisingly large number of citations from the Fourth

17 Lucan’s use of Livy was carefully and systematically demonstrated by Pichon (1912), esp. 51–164. See also FF 40, 44, 45, 49, 53, 55, with notes ad locc.

Decade: without Priscian, there would be just 4–5 (one from Servius, one from Quintilian, the rest from Plutarch). Even the Third Decade is Priscian-heavy, if to a lesser degree: he supplies 12 of the 20 citations. There is only one citation (also from Priscian) from Books 41–45, but those books have an anomalous transmission compared with the other surviving books, since they were unknown through the entire period of the mediaeval and Renaissance copyings, and were only rediscovered in the sixteenth century in the form of a single fifth-century MS with a number of leaves missing.

Moreover, among the lost books there are massive discrepancies. Large portions of Livy are hardly ever cited at all. There are just three citations/fragments— two by Priscian, one by Censorinus—from Books 41–75, although these thirty-five books represent a quarter of Livy’s total text. There are just 5–7 (depending on how one counts double citations by different Horace commentators) fragments from Books 121–142: 3–5 in the commentators on Horace, one each by Censorinus and Apponius. Some of this may be chance, but it would be reasonable to assume that these books were read far less than 1–10 and 21–30, where there is a moderate range of citing authorities. Indeed, it would be reasonable to assume that not only 41–75 and 121–142 but also the surviving books 31–40 were read less than the lost books 11–20, from which we have 12 fragments from a fair selection of authors: it is presumably no coincidence that those books certainly were being copied and read as late as the fifth century ad (cf. below).

So we can see a broad pattern: Book 1 gets cited a lot, the rest of the First Decade relatively widely, the Second less so, the Third and then the Fourth increasingly less, with only Priscian providing a counterbalance that makes the number of citations appear superficially even. Then citations disappear almost entirely for thirty-five books. This is perhaps unsurprising with a long and complex narrative in multiple volumes: vastly more people cite Du côté de chez Swann than Le temps retrouvé, and the vast majority of the people who cite Du côté de chez Swann cite only the first few pages. But the difference with Livy is that citations then pick up: there is a modest spate of fragments in Books 76–83, dealing with the civil wars of the 80s bc , then a far more significant number in Books 91–120, the books covering the last generation of the Republic and Caesar’s dictatorship: 40–44 of them.18 Part of that is the result of the concentrated group of fragments concerning the Civil War in the Lucan scholia (above), but even leaving those aside, this set of books is regularly cited by a wider range of authors than any other set except Books 1–20. The likely reason is that this period of the Republic was as iconic as any in Roman history, and contains a large proportion of the most familiar characters and anecdotes that became central in the exemplary traditions of the Empire. It is hardly surprising that this part of the work of

18 Depending whether one counts the duplicate citations in different scholastic traditions in FF 27, 33, 46, and 56 as separate fragments.

the iconic historian of the Republic would attract particular interest, although here, as elsewhere, the sheer length of Livy’s text did not make him an immediate recourse for most readers.

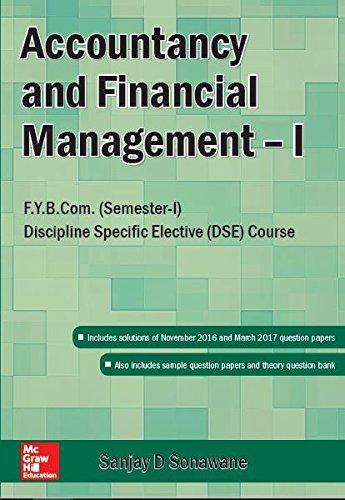

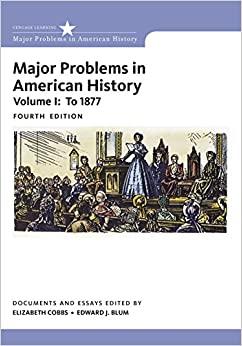

One further issue that is worth mentioning in this context is that the pattern of citation described above very approximately (with some significant exceptions) correlates with the balance of the narrative of the Periochae. I will be discussing in the introduction to Volume II the way in which the Periochae offers a narrative of Livy’s history with a distinctive focus of its own; but despite the author’s particular interests and constraints, it is striking that the pattern among the average lengths of the summaries of the individual books (see Fig. 1) is not entirely unlike the patterns of quotation and citation of Livy set out above. Thus the summaries of the First Decade are relatively long (averaging 256 words apiece);19 those of the Second, Third, and Fourth Decades somewhat shorter (respectively: 139, 226, and 160 words). Those of the later decades are shorter still: Books 121–142 average just 56 words, while Books 61–120 average 110 words apiece, though within that Books 101–120, covering the late Republic and Caesar, are treated a little more spaciously: those books average 120 words. These represent some small differences from the citation patterns: in the Periochae the Second Decade is less generously covered than the Third and the Fourth, and Books 91–100, at 70 words apiece, are more succinctly summarized than any other section apart from Books 121–142. But the huge and surprising anomaly, when one compares the Periochae with the citation patterns of Livy, is the generous treatment allotted to the Fifth and Sixth Decades: averaging, respectively, 262 and 194 words per book. This is partly because of the Periochist’s remarkable interest in the period of the Third Punic War and its preliminaries: Books 48 and 49 are by far the longest books of the entire summary; he also shows a particular interest in the period of the Gracchi and in the career of Scipio Aemilianus (cf. Volume II, xliv–xlv), both of which are completely overlooked by later citers of Livy’s text.

In the earlier discussion I spoke of the likelihood that a good proportion of those citing or referring to Livy were not doing so on the basis of direct acquaintance with his text. This, of course, has no necessary connection with the survival of his text: Plutarch sometimes cites Livy from an epitome (cf. above, xxv), even though MSS of the relevant books were presumably available to him. But although not all tralatician references to Livy are the result of the absence of his full text,

19 Here and elsewhere I take the figures for the book-lengths of the Periochae from my own text, using the ‘word-count’ facility in Microsoft Word. Some minor problems should be noted: there is occasional undercounting (when I have marked a likely lacuna in the text) and overcounting (when the text includes words which I argue should be deleted). These are, however, likely to be negligible in the overall figures, with the exception of the loss of the first half of Book 1, which, if on the scale of the second half, would have made that book closer to 600 words than 300, and would, accordingly, make the average word-length of the books of the First Decade more like 286 words than 256: that decade, therefore, was probably (unsurprisingly) the longest of all. Note also that the average for Books 121–142 excludes the two missing books: 136–137.

Le ngth in Wo rd s

the converse is obviously true: when Livy’s text was not available, he could only be cited at second or third hand, or his name might be (and sometimes clearly was) attached to a narrative which bore little relation to his actual text, on the grounds of his iconic status as the canonical historian of the Republic. To understand the reception of Livy, we therefore need to examine what we know about the early transmission and survival of his text.

With the surviving books, that is relatively unproblematic. All of them manifestly were still in circulation in the fifth century ad . 20 Moreover, some of the lost books were demonstrably being copied at the same time. The surviving parchment scrap of Book 11 (FF 1–2) was written in the middle of that century, and Pope Gelasius I cites ‘the Second Decade’ explicitly at the end of the century, implying that those books were still circulating as a unit (F 4). The fifth-century MS of Books 41–45 ends with the incipit for Book 46, implying that it originally contained that book, and presumably the rest of the Fifth Decade.

The more difficult question is whether the same is true of Books 51–142: whether those books remained in circulation as late as the fifth century. The last clear testimony we have of the survival of the complete history is a letter of Symmachus, dated 401, which mentions his ownership of it, and indeed promises to have a copy made for his correspondent Valerianus (T 36). That copy is presumably the same one as is attested21 as being made around the same time by members of the circle of Symmachus. But it is far from clear whether in the event the copy actually extended to the complete work, and whether Valerianus actually received it.

20 Indeed, we possess fifth-century copies of Books 1–10, 21–30 (forming the archetype of Books 21–25), and 41–45 (the last of which was subsequently lost and only rediscovered in the sixteenth century: it represents our only MS of those books); there are also fragments of Books 31–40 surviving in fifth-century copies.

21 In the subscriptions to most of our MSS of the First Decade (T 37: see ad loc.).

Books of the Periochae

Fig. 1 Length of Books of the Periochae