Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-research-methods-for-social-wo rk-9th-edition-ebook-pdf/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Empowerment Series: Essential Research Methods for Social Work 4th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-essentialresearch-methods-for-social-work-4th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Research Methods for Social Work 9e Edition Allen Rubin

https://ebookmass.com/product/research-methods-for-socialwork-9e-edition-allen-rubin/

Empowerment Series: Direct Social Work Practice: Theory and Skills 10th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-direct-socialwork-practice-theory-and-skills-10th-edition-ebook-pdf/

The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-handbook-of-social-workresearch-methods-ebook-pdf-version/

Empowerment Series: An Introduction to the Profession of Social Work 5th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-an-introductionto-the-profession-of-social-work-5th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Empowerment Series: An Introduction to the Profession of Social Work Elizabeth A. Segal

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-an-introductionto-the-profession-of-social-work-elizabeth-a-segal/

Survey Research Methods (Applied Social Research Methods Book 1) 5th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/survey-research-methods-appliedsocial-research-methods-book-1-5th-edition-ebook-pdf/

Empowerment Series: The Reluctant Welfare State 9th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-the-reluctantwelfare-state-9th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

Empowerment Series: Social Work with Groups: Comprehensive Practice and Self-Care 10th Edition Charles Zastrow

https://ebookmass.com/product/empowerment-series-social-workwith-groups-comprehensive-practice-and-self-care-10th-editioncharles-zastrow/

Toourwives CHRISTINARUBIN SUZANNEBABBIE CONTENTSINBRIEF PART1

AnIntroductiontoScientificInquiryin SocialWork1

Chapter1 WhyStudyResearch?2

Chapter2 Evidence-BasedPractice24

Chapter3 FactorsInfluencingtheResearch Process43

Chapter4 Quantitative,Qualitative,andMixed MethodsofInquiry66

PART2

TheEthical,Political,andCulturalContextof SocialWorkResearch81

Chapter5 TheEthicsandPoliticsofSocialWork Research82

Chapter6 CulturallyCompetentResearch112

PART3 ProblemFormulationandMeasurement139

Chapter7 ProblemFormulation140

Chapter8 ConceptualizationinQuantitative andQualitativeInquiry162

Chapter9 Measurement191

Chapter10 ConstructingMeasurement Instruments218

PART4

DesignsforEvaluatingPrograms andPractice241

Chapter11 CausalInferenceandExperimental Designs243

Chapter12 Quasi-ExperimentalDesigns272

Chapter13 Single-CaseEvaluationDesigns292

Chapter14 ProgramEvaluation320

PART5 DataCollectionMethodswithLargeSources ofData347

Chapter15 Sampling349

Chapter16 SurveyResearch378

Chapter17 AnalyzingExistingData:Quantitative andQualitativeMethods403

PART6 QualitativeResearchMethods433

Chapter18 QualitativeResearch:General Principles434

Chapter19 QualitativeResearch:Specific Methods455

Chapter20 QualitativeDataAnalysis478

PART7 AnalysisofQuantitativeData503

Chapter21 DescriptiveDataAnalysis504 Chapter22 InferentialDataAnalysis528

PART8

WritingResearchProposalsandReports551

Chapter23 WritingResearchProposals andReports552

AppendixA UsingtheLibrary577

AppendixB StatisticsforEstimatingSampling Error584

AppendixC CriticallyAppraising Meta-Analyses593

Glossary 596 Bibliography 617 Index 637

CONTENTSINDETAIL Prefacexvi

PART1

AnIntroductiontoScientificInquiryinSocial Work1

Chapter 1

WHYSTUDYRESEARCH?2

Introduction 3

AgreementReality3

ExperientialReality4

TheScientificMethod 4

AllKnowledgeIsTentativeandOpento Question4

Replication5

Observation5

Objectivity6

Transparency6

OtherWaysofKnowing 6

Tradition7

Authority8

CommonSense8

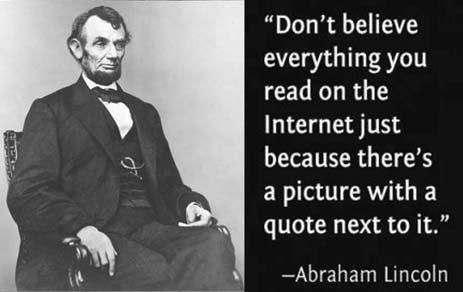

PopularMedia8

RecognizingFlawsinUnscientificSourcesofSocial WorkPracticeKnowledge 10

Overgeneralization10

SelectiveObservation10

ExPostFacto Hypothesizing12

EgoInvolvementinUnderstanding12

OtherFormsofIllogicalReasoning13

ThePrematureClosureofInquiry14

Pseudoscience14

TheUtilityofScientificInquiryinSocialWork 16

WillYouEverDoResearch?16

ReviewsofSocialWorkEffectiveness 17

EarlyReviews17

StudiesofSpecificInterventions17

TheNeedtoCritiqueResearchQuality 19 PublicationDoesNotGuaranteeQuality19 DistinguishingandFacilitatingMoreUseful Studies19

CompassionandProfessionalEthics 19

UtilityofResearchinAppliedSocialWork Settings 20

ResearchMethodsYouMaySomedayUseinYour Practice20

NationalAssociationofSocialWorkersCodeof Ethics21

MainPoints 21

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 22

InternetExercises 22

Chapter 2

EVIDENCE-BASEDPRACTICE24

Introduction 25

CriticalThinkinginEBP 25

EBPImpliesCareer-LongLearning 26

StepsintheEBPProcess 27

Step1.FormulateaQuestiontoAnswerPractice Needs27

Step2.SearchfortheEvidence29

Step3.CriticallyAppraisetheRelevantStudiesYou Find33

Step4.DetermineWhichResearch-Supported InterventionorPolicyIsMostAppropriatefor YourParticularClient(s)33

Step5.ApplytheChosenIntervention34

Step6.ProvideEvaluationandFeedback35 DistinguishingtheEvidence-BasedProcessfrom Evidence-BasedPractices 35

ControversiesandMisconceptionsaboutEBP 37

EBPIsBasedonStudiesofAtypicalClients37

EBPIsOverlyRestrictive37

EBPIsJustaCost-CuttingTool38

EvidenceIsinShortSupply38

TheTherapeuticAllianceWillBeHindered38

CommonFactorsandtheDodoBird 38

Real-WorldObstaclestoImplementingEBPin

EverydayPractice 39

AlleviatingFeasibilityObstaclestoEBP40

MainPoints 40

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 41

InternetExercises 41

Chapter 3

FACTORSINFLUENCINGTHERESEARCH PROCESS43

Introduction 44

ThePhasesoftheResearchProcess 44

TheoryandValues 47

UtilityofTheoryinSocialWorkPractice andResearch47

SocialWorkPracticeModels48

AtheoreticalResearchStudies49

PredictionandExplanation49

TheComponentsofTheory50

TheRelationshipbetweenAttributes andVariables51

TwoLogicalSystems:ComparingDeduction andInduction 53

ProbabilisticKnowledge 56

TwoCausalModelsofExplanation 57

UseofNomotheticandIdiographicResearch inSocialWorkPractice58

IdeologiesandParadigms 59

ContemporaryPositivism61 Interpretivism62

EmpowermentParadigm63

ParadigmaticFlexibilityinResearch63

MainPoints 64

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 65

InternetExercises 65

Chapter 4

QUANTITATIVE,QUALITATIVE,ANDMIXED METHODSOFINQUIRY66

Introduction 67

ObjectivityandSubjectivityinScientific Inquiry 67

AComparisonofQualitativeandQuantitative MethodsofInquiry 68

MixedMethodsofInquiry 70

TypesofMixed-MethodsDesigns71

ThreeBasicMixed-MethodsDesigns74

ThreeAdvancedMixed-MethodsDesigns77

ReasonsforUsingMixedMethods77

MainPoints 78

Practice-RelatedExercises 79

InternetExercises 79

PART2 TheEthical,Political,andCulturalContext ofSocialWorkResearch81

Chapter 5

THEETHICSANDPOLITICSOFSOCIAL WORKRESEARCH82

Introduction 83

InstitutionalReviewBoards 84

VoluntaryParticipationandInformed Consent85

NoHarmtotheParticipants86

AnonymityandConfidentiality87

DeceivingParticipants90

AnalysisandReporting90

WeighingBenefitsandCosts91

RighttoReceiveServicesversusResponsibility toEvaluateServiceEffectiveness92

NationalAssociationofSocialWorkersCode ofEthics93

IRBProceduresandForms94

TrainingRequirement94

ExpeditedReviews94

OverzealousReviewers97

FourEthicalControversies 98

ObservingHumanObedience98

TroubleintheTearoom100

“WelfareStudyWithholdsBenefitsfrom800 Texans” 101

SocialWorkerSubmitsBogusArticletoTestJournal Bias102

BiasandInsensitivityRegardingSex,Gender Identity,andCulture 105

ThePoliticsofSocialWorkResearch 106

SocialResearchandRace107

MainPoints 109

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 110

InternetExercises 111

Chapter 6

CULTURALLYCOMPETENTRESEARCH112 Introduction 113

ResearchParticipants113

Measurement113

DataAnalysisandInterpretation114

Acculturation115

ImpactofCulturalInsensitivityonResearch Climate116

DevelopingCulturalCompetence 116

RecruitingandRetainingtheParticipation ofMinorityandOppressedPopulationsin ResearchStudies119

ObtainEndorsementfromCommunity Leaders119

UseCulturallySensitiveApproachesRegarding Confidentiality120

EmployLocalCommunityMembersasResearch Staff120

ProvideAdequateCompensation120

AlleviateTransportationandChild-Care Barriers121

ChooseaSensitiveandAccessibleSetting121

UseandTrainCulturallyCompetent Interviewers121

UseBilingualStaff122

UnderstandCulturalFactorsInfluencing Participation122

UseAnonymousEnrollmentwithStigmatized Populations122

UtilizeSpecialSamplingTechniques123

LearnWheretoLook123

ConnectwithandNurtureReferralSources124

UseFrequentandIndividualizedContacts andPersonalTouches124

UseAnchorPoints125

UseTrackingMethods125

CulturallyCompetentMeasurement 126

CulturallyCompetentInterviewing126

LanguageProblems127

CulturalBias128

MeasurementEquivalence 130

LinguisticEquivalence130

ConceptualEquivalence131

MetricEquivalence131

AssessingMeasurementEquivalence132 MethodsforImprovingMeasurement Equivalence133

TheValueofQualitativeInterviews133 ProblematicIssuesinMakingResearchMore CulturallyCompetent 133

MainPoints 135

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 137

InternetExercises 137 PART3 ProblemFormulationandMeasurement139

Chapter 7

PROBLEMFORMULATION140 Introduction 141

PurposesofSocialWorkResearch 141 Exploration141

Description141

Explanation142

Evaluation142

ConstructingMeasurementInstruments143

MultiplePurposes 143

SelectingTopicsandResearchQuestions 143

NarrowingResearchTopicsintoResearch Questions 145

AttributesofGoodResearchQuestions 146

Feasibility147

InvolvingOthersinProblemFormulation 149

LiteratureReview 150

WhyandWhentoReviewtheLiterature150

HowtoReviewtheLiterature151

SearchingtheWeb152

BeThorough152

TheTimeDimension 156

Cross-SectionalStudies156

LongitudinalStudies156

UnitsofAnalysis 158

MainPoints 160

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 161

InternetExercises 161

Chapter 8

CONCEPTUALIZATIONINQUANTITATIVE ANDQUALITATIVEINQUIRY162

Introduction 163

ContrastingQuantitativeandQualitative Conceptualization 163

ConceptualExplicationinQuantitative Inquiry 164

DevelopingaProperHypothesis165

DifferencesbetweenHypothesesandResearch Questions166

TypesofRelationshipsbetweenVariables166

ExtraneousVariables167

ModeratingVariables168

Constants169

MediatingVariables169

TheSameConceptCanBeaDifferentTypeof VariableinDifferentStudies170

OperationalDefinitions 172

OperationallyDefiningAnythingThatExists173

Conceptualization174

IndicatorsandDimensions175

ClarifyingConcepts176

TheInfluenceofOperationalDefinitions178

SexandCulturalBiasinOperational Definitions178

OperationalizationChoices 179

RangeofVariation179

VariationsbetweentheExtremes180 ANoteonDimensions180

ExamplesofOperationalizationinSocial Work 180

ExistingScales 182

OperationalizationGoesOnandOn 186

LevelsofMeasurement 186

ConceptualizationinQualitativeInquiry 187

MainPoints 189

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 190

InternetExercises 190

Chapter 9 MEASUREMENT191

Introduction 192

CommonSourcesofMeasurementError 192

SystematicError192 RandomError195

ErrorsinAlternateFormsofMeasurement195

AvoidingMeasurementError 197

Reliability 199

TypesofReliability200

InterobserverandInterraterReliability200

Test–RetestReliability201

InternalConsistencyReliability201

Validity 202

FaceValidity203

ContentValidity203

Criterion-RelatedValidity204

ConstructValidity206

FactorialValidity207

AnIllustrationofReliableandValidMeasurement inSocialWork:TheClinicalMeasurement Package 208

RelationshipbetweenReliabilityandValidity 211

ReliabilityandValidityinQualitative Research 214

MainPoints 216

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 217

InternetExercises 217

Chapter 10

CONSTRUCTINGMEASUREMENT INSTRUMENTS218

Introduction 219

GuidelinesforAskingQuestions 219

QuestionsandStatements220

Open-EndedandClosed-EndedQuestions220

MakeItemsClear221

AvoidDouble-BarreledQuestions221

RespondentsMustBeCompetentto Answer221

RespondentsMustBeWillingto Answer222

QuestionsShouldBeRelevant222

ShortItemsAreBest222

AvoidWordsLike No or Not 222

AvoidBiasedItemsandTerms223

QuestionsShouldBeCulturallySensitive223

QuestionnaireConstruction 223

GeneralQuestionnaireFormat223

FormatsforRespondents225

ContingencyQuestions225

MatrixQuestions227

OrderingQuestionsinaQuestionnaire227

QuestionnaireInstructions228

PretestingtheQuestionnaire229

ConstructingScales 229

LevelsofMeasurement230

SomeProminentScalingProcedures231

ItemGenerationandSelection232

HandlingMissingData234

ConstructingQualitativeMeasures 235

MainPoints 237

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 238

InternetExercises 238

PART4 DesignsforEvaluatingPrograms andPractice241

Chapter 11 CAUSALINFERENCEANDEXPERIMENTAL DESIGNS243

Introduction 244

CriteriaforInferringCausality 244

TimeSequence245

Correlation246

RulingOutAlternativeExplanations246

StrengthofCorrelation246

PlausibilityandCoherence246

ConsistencyinReplication248

InternalValidity 248

PreexperimentalPilotStudies 252

One-ShotCaseStudy252

One-GroupPretest–PosttestDesign252

Posttest-OnlyDesignwithNonequivalentGroups (Static-GroupComparisonDesign)253

ExperimentalDesigns 254

Randomization259

Matching259

ProvidingServicestoControlGroups261

AdditionalThreatstotheValidityofExperimental Findings 262

MeasurementBias262

ResearchReactivity262

DiffusionorImitationofTreatments264

CompensatoryEqualization,CompensatoryRivalry, orResentfulDemoralization266

Attrition(ExperimentalMortality) 266

ExternalValidity 268

MainPoints 270

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 271

InternetExercises 271

Chapter 12

QUASI-EXPERIMENTALDESIGNS272

Introduction 273

NonequivalentComparisonGroupsDesign 273

WaystoStrengthentheInternalValidityofthe NonequivalentComparisonGroups Design 274

MultiplePretests275

SwitchingReplication276

SimpleTime-SeriesDesigns 276

MultipleTime-SeriesDesigns 279

Cross-SectionalStudies 280

CaseControlStudies 283

PracticalPitfallsinCarryingOutExperiments andQuasiExperimentsinSocialWork Agencies 284

FidelityoftheIntervention285

ContaminationoftheControlCondition286

ResistancetotheCaseAssignmentProtocol286

ClientRecruitmentandRetention286

MechanismsforAvoidingorAlleviatingPractical Pitfalls287

QualitativeTechniquesforAvoidingorAlleviating PracticalPitfalls 288

MainPoints 290

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 290

InternetExercises 291

Chapter 13

SINGLE-CASEEVALUATIONDESIGNS292

Introduction 293

OverviewoftheLogicofSingle-CaseDesigns 293

Single-CaseDesignsinSocialWork 295

UseofSingle-CaseDesignsasPartofEvidenceBasedPractice 296

MeasurementIssues 298

OperationallyDefiningTargetProblems andGoals298

WhattoMeasure299

Triangulation299

DataGathering 300 WhoShouldMeasure?300

SourcesofData301

ReliabilityandValidity301

DirectBehavioralObservation301

UnobtrusiveversusObtrusiveObservation302

DataQuantificationProcedures303

TheBaselinePhase303

AlternativeSingle-CaseDesigns 306

AB:TheBasicSingle-CaseDesign306

ABAB:Withdrawal/ReversalDesign307

Multiple-BaselineDesigns309

Multiple-ComponentDesigns312

DataAnalysis 313

InterpretingAmbiguousResults314

AggregatingtheResultsofSingle-CaseResearch Studies315

BandB+Designs 316

TheRoleofQualitativeResearchMethods inSingle-CaseEvaluation 317

MainPoints 318

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 319

InternetExercises 319

Chapter 14 PROGRAMEVALUATION320

Introduction 321

HistoricalOverview 321

TheImpactofManagedCare322 Evidence-BasedPractice323 PlanninganEvaluationandFosteringIts Utilization 323 LogicModels324

PurposesandTypesofProgramEvaluation 327

SummativeandFormativeEvaluations327 EvaluatingOutcomeandEfficiency328 Cost-EffectivenessandCost–BenefitAnalyses329 ProblemsandIssuesinEvaluatingGoal Attainment330 MonitoringProgramImplementation331 ProcessEvaluation332

EvaluationforProgramPlanning:Needs Assessment333 FocusGroups336

AnIllustrationofaQualitativeApproachto EvaluationResearch 337

ThePoliticsofProgramEvaluation 339 In-HouseversusExternalEvaluators340

UtilizationofProgramEvaluationFindings342

LogisticalandAdministrativeProblems343

MainPoints 344

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 345

InternetExercises 346

PART5

DataCollectionMethodswithLargeSources ofData347

Chapter 15

SAMPLING349

Introduction 350

PresidentAlfLandon351

PresidentThomasE.Dewey351

PresidentJohnKerry352

NonprobabilitySampling 352

RelianceonAvailableSubjects353

PurposiveorJudgmentalSampling355

QuotaSampling356

SnowballSampling356

SelectingInformantsinQualitativeResearch 357

TheLogicofProbabilitySampling 357

ConsciousandUnconsciousSamplingBias357

RepresentativenessandProbabilityof Selection358

RandomSelection359

CanSomeRandomlySelectedSamplesBe Biased? 360

SamplingFramesandPopulations360

NonresponseBias362

ReviewofPopulationsandSamplingFrames363

SampleSizeandSamplingError 363

EstimatingtheMarginofSamplingError363

OtherConsiderationsinDeterminingSample Size365

TypesofProbabilitySamplingDesigns 366

SimpleRandomSampling366

SystematicSampling366

StratifiedSampling368

ImplicitStratificationinSystematicSampling369

ProportionateandDisproportionateStratified Samples369

MultistageClusterSampling 371

MultistageDesignsandSamplingError372

StratificationinMultistageCluster Sampling373

Illustration:SamplingSocialWorkStudents 374

SelectingthePrograms374

SelectingtheStudents374

ProbabilitySamplinginReview 375

AvoidingSexBiasinSampling 375

MainPoints 376

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 376

InternetExercises 377

Chapter 16

SURVEYRESEARCH378 Introduction 379

TopicsAppropriatetoSurveyResearch380

Self-AdministeredQuestionnaires 381

MailDistributionandReturn381

CoverLetter382

MonitoringReturns384

Follow-UpMailings384

ResponseRates385

IncreasingResponseRates386

ACaseStudy386

InterviewSurveys 387

TheRoleoftheSurveyInterviewer387

GeneralGuidelinesforSurveyInterviewing388 CoordinationandControl390

TelephoneSurveys 392

TheInfluenceofTechnologicalAdvances393

OnlineSurveys 394

OnlineDevices394

InstrumentDesign395

ImprovingResponseRates395

Mixed-ModeSurveys 396

ComparisonofDifferentSurveyMethods 397

StrengthsandWeaknessesofSurveyResearch 398

MainPoints 400

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 401

InternetExercises 401

Chapter 17

ANALYZINGEXISTINGDATA:QUANTITATIVE ANDQUALITATIVEMETHODS403

Introduction 404

ACommentonUnobtrusiveMeasures 404

SecondaryAnalysis 405

TheGrowthofSecondaryAnalysis405

TypesandSourcesofDataArchives406

SourcesofExistingStatistics407

AdvantagesofSecondaryAnalysis407

LimitationsofSecondaryAnalysis410

IllustrationsoftheSecondaryAnalysisofExisting StatisticsinResearchonSocialWelfare Policy413

DistinguishingSecondaryAnalysisfrom OtherFormsofAnalyzingAvailable Records415

ContentAnalysis 415

SamplinginContentAnalysis417

SamplingTechniques418

CodinginContentAnalysis418

ManifestandLatentContent418

ConceptualizationandtheCreationofCode Categories419

CountingandRecordKeeping420

QualitativeDataAnalysis421

QuantitativeandQualitativeExamplesofContent Analysis422

StrengthsandWeaknessesofContent Analysis424

HistoricalandComparativeAnalysis 424

SourcesofHistoricalandComparative Data425

AnalyticTechniques428

UnobtrusiveOnlineResearch 428

MainPoints 429

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 430

InternetExercises 430

PART6 QualitativeResearchMethods433

Chapter 18

QUALITATIVERESEARCH:GENERAL PRINCIPLES434

Introduction 435

TopicsAppropriateforQualitativeResearch 435

ProminentQualitativeResearchParadigms 436 Naturalism436

GroundedTheory436

ParticipatoryActionResearch440

CaseStudies441

QualitativeSamplingMethods 443

StrengthsandWeaknessesofQualitative Research 446

DepthofUnderstanding446

Flexibility447

Cost448

SubjectivityandGeneralizability448

StandardsforEvaluatingQualitativeStudies 449

ContemporaryPositivistStandards450

SocialConstructivistStandards451

EmpowermentStandards452

ResearchEthicsinQualitativeResearch 452

MainPoints 453

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 454

InternetExercises 454

Chapter 19

QUALITATIVERESEARCH:SPECIFICMETHODS455

Introduction 456

PreparingfortheField 456

SearchtheLiterature456

UseKeyInformants456

EstablishInitialContact456

EstablishRapport457

ExplainYourPurpose457

TheVariousRolesoftheObserver 457

CompleteParticipant457

ParticipantasObserver459

ObserverasParticipant460

CompleteObserver460

RelationstoParticipants:EticandEmic

Perspectives 460

EticPerspective461

EmicPerspective461

AdoptingBothPerspectives461

Reflexivity 461

QualitativeInterviewing 462

InformalConversationalInterviews463

InterviewGuideApproach465

StandardizedOpen-EndedInterviews467

LifeHistory 467

FeministMethods 468

FocusGroups 468

Sampling468

TypesandSequenceofQuestions469

Advantages469

Disadvantages471

RecordingObservations 471

VoiceRecording473

Notes473

AdvancePreparation473

RecordSoon473

TakeNotesinStages475

DetailsCanBeImportant475

Practice475

MainPoints 475

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 476

InternetExercises 477

Chapter 20

QUALITATIVEDATAANALYSIS478

Introduction 479

LinkingTheoryandAnalysis 479

DiscoveringPatterns479

GroundedTheoryMethod480

Semiotics481

ConversationAnalysis483

QualitativeDataProcessing 483

Coding483

Memoing487

ConceptMapping488

ComputerProgramsforQualitativeData 489

QualitativeDataAnalysisPrograms489

LeviticusasSeenthroughQualrus491

N-Vivo493

MainPoints 501

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 501

InternetExercises 502

PART7

AnalysisofQuantitativeData503

Chapter 21

DESCRIPTIVEDATAANALYSIS504

Introduction 505

Coding 505

DevelopingCodeCategories505

DataEntry 507

DataCleaning 507

UnivariateAnalysis 508

Distributions508

ImplicationsofLevelsofMeasurement509

CentralTendency510

Dispersion512

BivariateAnalysis 514

InterpretingBivariateTables514

InterpretingMultivariateTables 515

ConstructingTables 516

TableTitlesandLabels516

DetailversusManageability517

HandlingMissingData518

PercentagingBivariateandMultivariate Tables518

MeasuringtheStrengthofRelationships 519

Correlation519

EffectSize520

Cohen’s d 521

DescriptiveStatisticsandQualitative Research 522

MainPoints 525

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 526

InternetExercises 527

Chapter 22

INFERENTIALDATAANALYSIS528

Introduction 529

ChanceasaRivalHypothesis 529

RefutingChance531

StatisticalSignificance 531

TheoreticalSamplingDistributions531

SignificanceLevels533

One-TailedandTwo-TailedTests534

TheNullHypothesis537

TypeIandTypeIIErrors538

TheInfluenceofSampleSize540

InterpretingRelationshipStrength 540

Strong,Medium,andWeakEffectSizes541

SubstantiveSignificance 542

StatisticalPowerAnalysis 543

SelectingandCalculatingTestsofStatistical Significance 546

Meta-Analysis 547

MainPoints 548

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 549

InternetExercises 549

PART8

WritingResearchProposalsandReports551

Chapter 23

WRITINGRESEARCHPROPOSALS ANDREPORTS552

Introduction 553

WritingResearchProposals 553

FindingaFundingSourceandRFPs 553

Large-ScaleandSmall-ScaleRFPsand Proposals554

GrantsandContracts554

BeforeYouStartWritingtheProposal556

ResearchProposalComponents557

CoverMaterials557

ProblemandObjectives557

LiteratureReview558

ConceptualFramework559

Measurement559

StudyParticipants(Sampling)560

DesignandDataCollectionMethods560

DataAnalysis563

Schedule564

Budget564

AdditionalComponents564

WritingSocialWorkResearchReports 565

SomeBasicConsiderations565

OrganizationoftheReport 570

Title570

Abstract570

IntroductionandLiteratureReview570

Methods571

Results571

DiscussionandConclusions572

ReferencesandAppendices573

AdditionalConsiderationsWhenWriting QualitativeReports 573

MainPoints 574

ReviewQuestionsandExercises 575

InternetExercises 575

Appendix A

USINGTHELIBRARY 577

Introduction 577

AccessingandExaminingLibraryMaterials Online 577

GettingHelp 577

ReferenceSources 577

UsingtheStacks 578

Abstracts 578

ProfessionalJournals 580

Appendix B

STATISTICSFORESTIMATINGSAMPLING

ERROR 584

TheSamplingDistributionof10Cases 584

SamplingDistributionandEstimatesofSampling Error 585

ConfidenceLevelsandConfidenceIntervals 591

Appendix C

CRITICALLYAPPRAISINGMETA-ANALYSES 593

PotentialFlawsinMeta-Analyses 593

ConflictsofInterest593

LumpingTogetherStrongandWeak Studies593

ProblemsinRatingsofMethodological Quality594

FileDrawerEffect594

WhattoLookforWhenAppraising Meta-Analyses 595

Transparency595

MethodologiesofIncludedStudies595

UnpublishedStudies595

Comprehensiveness595

Conclusion 595

Glossary 596

Bibliography 617

Index 637

PREFACE Aswithpreviouseditionsofthistext,thisnintheditioncontainssignificantimprovementstokeepup withadvancesinthefieldandrespondtotheexcellentsuggestionsfromcolleagues.Oneofthethings thathasn’tchangedisourpresentationofboxesto illustrateconceptsthatbringresearchcontenttolife andillustrateitsrelevancetosocialworkandits utilityininformingsocialworkpractice.Inthat connection,wehaveaddedsomenewboxesinthis edition.Herearesomeofourothermostnoteworthychangestothisedition.

CSWEEPASCoreCompetencies.Aswewere writingthisnewedition,theCouncilonSocial WorkEducationwasintheprocessofrevisingits EducationalPolicyandAccreditationStandards (EPAS)CoreCompetencies.Accordingly,wehave changedthewayweshowhowthecontentsofour bookpertaintothosecorecompetencies.

BookLength. Inresponsetoreviewerconcerns aboutthelengthandcostofthebook,westrivedto shortenthiseditioninwaysthatwillnotsacrifice oneofitschiefvirtues:itscomprehensivenessand useofmanysocialworkpracticeexamplesand illustrations.Althoughtheshorteningrevisions occurredinmanychapters,theyaremostnoteworthyinthecontentoninferentialstatistics,inwhich twochapterswereshortenedandcombinedintoone (Chapter22).

SignificantAdditions. Atthesametime,we mademanyadditionsthroughoutthebook.The mostsignificantadditionsareasfollows:

• Expandedcoverageofmixed-methods

• NewcontentonLGBTQpopulationsinseveral chapters

• Expandedcontentonscaledevelopment

• Newcontentoncriteriaforinferringcausality inepidemiologicalresearch

• Moreemphasisonhowtoconductsuccessful programevaluations

• New,updatedcontentonhowadvancesin technologyareaffectingsurveysandqualitative research

• Newcontentonhowtoconductfocusgroup interviewing

• AnewAppendixoncriticallyappraisingmetaanalyses

Belowisachapter-by-chapterdescriptionofour mostnoteworthychanges.

• Chapter1.Severalreviewersofferedusefulrecommendationsregardingtheneedtoshorten thislengthychapter.Weagreedwithandfollowedtheiradvice.Atthesametime,however, wemanagedtoaddahumorousphotoanda newboxlistingsomeinterventionswithstrong researchsupport.

• Chapter2.Throughoutourdiscussionofevidence-basedpractice(EBP),wehaveincreased contentshowinghowEBPappliestothemacro andpolicylevelsofsocialworkpractice.Also throughoutwehavereplacedwordingabout EBP guiding practicewithwordingaboutEBP informing practicedecisions.Wereplacedthe modelofEBPinFigure2-1withanupdatedversionofthemodel.Weelaboratedourdiscussion ofsystematicreviewsandmeta-analysesand addedFigure2-2oncriteriaforcriticallyappraisingthem.WealsoupdatedourboxonGoogle Scholarresults.

• Chapter3.Inresponsetosuggestionsfromour reviewersandothercolleagues,extensivechanges weremadetothischapterinanefforttomakeit lessoverwhelmingandmorerelevanttosocial workstudents.Inparticular,wehaveshortened thecoverageofphilosophicalissues,madeitless esoteric,andmodifieditsothatinsteadofdwellingonparadigmwarsitputsmoreemphasis ontheflexibleuseofeachparadigm,depending ontheresearchquestionandstudypurpose.

Inkeepingwiththisnewemphasis,wehave renamedthechapter,replacingphilosophyand theoryinthetitlewith “FactorsInfluencingthe ResearchProcess.” Thephilosophicalcontentno longerappearsatthebeginningofthechapter. Instead,thechapterstartsbycoveringthephases oftheresearchprocess,movingcoverageofphilosophicalissuesfromtheendofChapter4inthe previouseditiontothestartofChapter3inthis one.Thepreviousfigurediagramingtheresearch processhasbeenreplacedwithonethatisless clutteredandcomplex onethatwethinkstudentswillfindmorerelevantandeasiertofollow. Oneofthesuggestionswehavereceivedfrom colleaguesistoaddmoreLGBTQcontenttovariouspartsofthebook.Inthatconnection,we havealteredthewaywecoversexandgender variablesinthischapter.

• Chapter4.Wehavereceivedenthusiasticpraise forthischapterfromvariouscolleagues,who haveaddedthatthey’dliketoseethecontenton mixed-methodsexpandedabit.So,wehave expandedourdiscussionofmixed-methods,includingcoverageofadditionaltypesofmixed methodsdesignsandanewboxprovidinga caseexampleofapublishedmixed-methods studyofclientsandpractitionersinachildwelfareagency.

• Chapter5.Weaddedcontentongetting informedconsenttovideorecord,elaborated onIRBdebriefingrequirementswhendeception isinvolvedintheresearch,addedcontenton federalregulationsregardingvulnerablepopulations,andmodifiedoursectiononbiasand insensitivitytobetterdistinguishtheconcepts ofsexandgenderidentityandthusmakethe sectionmoreappropriateregardingLGBTQ people.Alsobolsteringthechapter’sattention toresearchethicsconcerningLGBTQpopulations,weaddedaboxtitled “IRBImperfections RegardingResearchwithLesbian,Gay,and BisexualPopulations.” InadditiontoillustratingmistakesthatIRBboardmemberscan make,thatboxshowshowbesttorespondto suchmistakestoenhancechancesforeventual IRBapproval.Inresponsetorequestsfrom reviewers,weshortenedsomewhatthevery lengthysectiononpolitics,reducingtheamount ofattentiongiventoobjectivityandideology. Wethinkthatnowstudentswillbebetterable

tocomprehendandappreciatetherelevanceof thatsection.

• Chapter6.Wehaveaddedsubstantialcontent regardingculturalcompetencewithregardto LGBTQindividuals.

• Chapter7.Inresponsetoareviewer’srequest formorecontentonresearchquestiondevelopmentwe’veaddedanewboxillustratingthe processofformulatingagoodresearchquestion. Inkeepingwithouroverallefforttoshortenthis bookwithoutlosingisessentialcomprehensiveness,wealsohaveimplementedreviewersuggestionstomakethecoverageofunitsofanalysis lessextensiveandlessdetailed.Insodoing,we thinkstudentswillfindcoverageofthattopic morerelevantandeasiertocomprehend.

• Chapter8.Weclarifiedwhatismeantbytruisms.Weaddedaboxprovidingmoreexamples ofspuriousrelationships.Wesimplifiedsomewhatourdiscussionofconceptionsandreality andclarifiedthattheconsequencesofabstract constructsarereal.Inresponsetosuggestions fromcolleagues,wehavemovedupthesection onlevelsofmeasurementfromChapter21to thischapter.Contentontheimplicationsof levelsofmeasurementforstatisticalanalysis remainsinChapter21.

• Chapter9.Weaddedabriefexplanationofthe term correlation tothesectiononinterraterreliabilityandanewboxtofurtherillustratethe differencebetweenreliabilityandvalidity.

• Chapter10.Wesignificantlyexpandedourdiscussionofscaledevelopment,includingalarge newsectionongeneratinganinitialpoolof itemsandhowtoselectitemsfromthatpool. Wealsoexpandedsomewhatourdiscussionof double-barreleditems,partlytoenhancereader understandingofsomeofthenuancesinvolved andpartlytocompensatefortheremovalofthe outdatedboxonthesubject.Inresponseto reviewer suggestions,andalsototrytoreduce thelengthandcostofthisedition,wereplaced one3-pagelongandsomewhatoutdatedfigure ofacompositeillustrationwithamuchshorter (one-halfpage)figureandreplacedthe4.5page figuredisplayingexcerptsfromalengthystandardizedopen-endedinterviewschedulewitha briefsummaryofthatscheduleandareproductionofjustoneitemfromit.

• Chapter11.Wesignificantlyexpandedourdiscussionofcriteriaforinferringcausality,especiallyinregardtoadditionalcriteriausedin epidemiologicalresearch,suchasstrengthof correlation,plausibilityandcoherence,and consistencyinreplication.Wealsoaddedsome commentsaboutethicsandIRBapprovalin regardtocontrolgroups.

• Chapter12.Ourcolleaguesexpressedpraisefor thischapterandhadonlyafewminorsuggestionsfortweakingit.Onefoundthebriefbox nearthebeginningofthechaptertobeunnecessary.Weagreedanddeleteditinkeepingwith ourefforttoreducethelengthandcostofthe book.

• Chapter13.Witheachneweditionofthisbook wereceiveconsistentlypositivefeedbackabout thischapter.Wefoundlittleneedtoupdateor otherwisemodifythischapter,withoneexception.Oneofourreviewerspointedouttheneed toaddresstheimplicationsofdisagreements amongtriangulateddatagatherers.Sowe addedthatforthisedition.

• Chapter14.Thiswasoneofourmoreextensivelyrevisedchapters.Therevisionswere primarilyintheorganizationandtoneofthe chapter,althoughsomenewcontentwas added,aswell.Whilekeepingmostofthepreviouscontentonthepoliticsofprogramevaluationandthedifficultiesthatcanposefor evaluators,wewantedtoimprovethechapter’s emphasisonhowtoconductsuccessfulevaluations.Inthatconnection,wemovedmostofthe politicscontenttowardthebackofthechapter, clarifiedthatitpertainsmainlytooutcomeevaluations,andmovedothersectionsclosertothe front.Logicmodels,forexample,previouslyappearedinthepenultimatesectionofthechapter andnowappearearlyinit,rightafteramovedupsectiononplanninganevaluation.Wealso updatedandshortenedourcoverageofthe impactofmanagedcare.Asectiononevidencebasedpracticewasaddedtoourhistorical overview.Itintroducesreaderstotheutilityof meta-analysesandeffect-sizestatistics concepts coveredmorecomprehensivelyinlaterchapters. Wealsoexpandedourdiscussionofsummative andformativeevaluations.

• Chapter15.Ourcolleaguesappeartoberelativelypleasedwiththischapter.Weimplementedseveralminortweaksthattheysuggestedas wellasarequestbysomeforamoresubstantial revision:ashortenedandlesscomplexdiscussionofmultistageclustersampling.

• Chapter16.Thischapterreceivedextensive revisionstotrytokeeppacewithnewtechnologicaladvancesaffectingtelephoneand onlinesurveys.Wealsoreferreadersto sourcesforkeepingabreastofthesedevelopments.Fournewsectionswereaddedregarding:(1)theimplicationsoftheseadvancesfor telephonesurveys;(2)instrumentdesignfor onlinesurveys;(3)improvingresponserates inonlinesurveys;and(4)mixed-modesurveys combiningonline,telephone,andpostalmail methods.

• Chapter17.Thisisanotherchapterwithnew contentregardingthewaysinwhichour onlineworldisaffectingresearch.Themain changeistheadditionofasectionononline unobtrusiveresearch,whichincludesexamples ofstudiesthatmonitorsocialmediapoststo identifywordsandphrasesthatarepredictive ofactualsuicideattemptsandotherself-harm behaviors.

• Chapter18.Varioustweaksweremadeinthis chapter,assuggestedbyreviewers;however, therewerenomajoradditionstoit.

• Chapter19.Themainrevisionstothischapter wereasfollows:(1)theadditionofasectionon thetypesandsequencingoffocusgroupquestions,and(2)anewboxsummarizingafocus groupstudy publishedinthe Journalof GerontologicalSocialWork thatassessedthe psychosocialneedsoflesbianandgayeldersin long-termcare.

• Chapter20.Themainrevisioninthischapter wasanexpansionofcontentonopencoding.

• Chapter21.Wemademanysignificantchanges toourchaptersonquantitativedataanalysisin anefforttoshortenandsimplifythiscontentin waysthatbetterfithowmostinstructorshandle itintheircourses.Inthischapter,forexample, weremovedmostofthecontentonlevelsof measurementinlinewithrequeststomove

thatcontentuptoChapter8(seeabove). What’sleftisthecontentontheimplications ofthoselevelsforthekindsofdescriptivestatisticsthatareappropriatetocalculate.Aspartof ourefforttocollapseourtwoinferentialdata analyseschaptersintoonechapterandreduce theoveralllengthandcomplexityoftheinferentialcontent,wemovedthecoverageofmeasuresofassociationfromChapter22intothis chapter.Wealsoexpandedourcoverageof tableconstructionandreplacedseveraltables withonesfocusingonillustrationsofmore directrelevancetosocialwork.

• Chapter22.Inkeepingwithoureffortto improvethefitbetweenourcoverageofinferentialdataanalysisandhowthatcontentiscoveredinmostresearchmethodscourses,we removedthecontentthatismuchmorelikely tobecoveredinstatisticscourses.Insodoing, wewereabletocollapseandcombineourprevioustwochaptersonthiscontentintoone chapter.Asmentionedabove,wemovedmost ofthecoverageofmeasuresofassociationup intoChapter21,retaininginthischapteronly thepartdealingwiththeinterpretationofrelationshipstrength.Wemovedthecoverageof statisticalpoweranalysisupfromChapter23 intothischapter.Wecutmostofthecontent ontestsofsignificanceandmoveditupinto thischapter,aswell,althoughweaddedabox thatidentifiesthepurposeofsomesignificance testscommonlyusedinoutcomestudiesrelevanttoevidence-basedpractice.Alsomoved upisourcoverageofmeta-analyses.Wetook thecontentonhowtocriticallyappraisemetaanalysesoutofthischapterandputan expandedversionofthatcontentinanew Appendix.

• Chapter23.Inthischapter(whichusedtobe Chapter24),wehaveaddedasectioncomparinglarge-scaleandsmall-scaleRFPsandproposals,includinganewboxillustratingasmallscaleRFPaimedatstudentswhowantto conductresearchonLGBTfamilyissues.

• AppendixA.We’veupdatedtheappendixon usingthelibrarytomakeitmoreconsistent withtoday’sonlineworld.

• AppendixB.Weupdatedthediscussionof selectingrandomnumbersinregardtogeneratingrandomnumbersonline.

• AppendixC.Thisnewappendixcontains expandedcoverageoncriticallyappraising meta-analyses.

ANCILLARYPACKAGE MindTap ResearchMethodsforSocialWorkcomeswith MindTap,anonlinelearningsolutioncreatedto harnessthepoweroftechnologytodrivestudent success.Thiscloud-basedplatformintegratesa numberoflearningapplications(“apps”)intoan easy-to-useandeasytoaccesstoolthatsupportsa personalizedlearningexperience.MindTapcombinesstudentlearningtools-readings,multimedia, activitiesandassessmentsintoasingularLearning Paththatguidesstudentsthroughthecourse.This MindTapincludes:

• Entireelectronictext

• Additionalreadingstofurtherexplorechapter topics

• CaseStudies

• VideoExamples

• Quizzing

• Flashcards

OnlineInstructor’sManual

TheInstructor’sManual(IM)containsavarietyof resourcestoaidinstructorsinpreparingandpresentingtextmaterialinamannerthatmeetstheir personalpreferencesandcourseneeds.Itpresents chapter-by-chaptersuggestionsandresourcesto enhanceandfacilitatelearning.

CengageLearningTestingPoweredby Cognero

Cogneroisaflexible,onlinesystemthatallowsyou toauthor,edit,andmanagetestbankcontentas wellascreatemultipletestversionsinaninstant.

Youcandelivertestsfromyourschool’slearning managementsystem,yourclassroom,orwherever youwant.

OnlinePowerPoint ThesevibrantMicrosoft® PowerPoint® lecture slidesforeachchapterassistyouwithyourlecture byprovidingconceptcoverageusingimages,figures,andtablesdirectlyfromthetextbook.

SocialWorkCourseMateWebsitefor ResearchMethodsforSocialWork

Accessibleat http://www.cengagebrain.com,the text-specificCourseMatewebsiteofferschapterby-chapteronlinequizzes,chapteroutlines,crosswordpuzzles,flashcards(fromthetext’sglossary), reviewquestions,andexercises(fromtheendsof chaptersinthetext)thatprovidestudentswithan opportunitytoapplyconceptspresentedinthe text.StudentscangototheCompanionSiteto accessaprimerforSPSS17.0.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Weowespecialthankstothefollowingcolleagues whomadevaluablesuggestionsforimprovingthis edition:

NikolaAlenkin,CaliforniaStateUniversity,Los Angeles

JuanAraque,UniversityofCalifornia

KathleenBolland,UniversityofAlabama

AnnaleaseGibson,AlbanyStateUniversity

SusanGrossman,LoyolaUniversity

RichardHarris.UniversityofTexas,San Antonio

MaryJaneTaylor,UniversityofUtah

DanielWeisman,RhodeIslandCollege

MollyWolf,StateUniversityofNewYork, Buffalo

AllenRubin EarlR.Babbie

Science isawordeveryoneuses.Yetpeople’simages ofsciencevarygreatly.Forsome,scienceismathematics;forothers,scienceiswhitecoatsandlaboratories.Thewordisoftenconfusedwith technology orequatedwithchallenginghighschoolorcollege courses.

Ifyoutellstrangersthatyouaretakingacourse dealingwithscientificinquiryandaskthemtoguess whatdepartmentit’sin,theyarealotmorelikelyto guesssomethinglikebiologyorphysicsthansocial work.Infact,manysocialworkersthemselvesoften underestimatetheimportantrolethatscientific inquirycanplayinsocialworkpractice.Butthisis changing.Moreandmore,socialworkersarelearninghowtakingascientificapproachcanenhance theirpracticeeffectiveness.

Althoughscholarscandebatephilosophical issuesinscience,forthepurposesofthisbookwe willlookatitasamethodofinquiry thatis,a wayoflearningandknowingthingsthatcanguide thedecisionsmadeinsocialworkpractice.When contrastedwithotherwaysthatsocialworkpractitionerscanlearnandknowthings,scientificinquiry hassomespecialcharacteristics mostnotably,a searchforevidence.

Inthisopeningsetofchapters,we’llexaminethe natureofscientificinquiryanditsrelevanceforsocial work.We’llexplorethefundamentalcharacteristics andissuesthatmakescientificinquirydifferentfrom otherwaysofknowingthingsinsocialwork.

InChapter1,we’llexaminethevalueofscientificinquiryinsocialworkpracticeandhowithelps safeguardagainstsomeoftherisksinherentinalternativesourcesofpracticeknowledge.

Chapter2willdelveintoevidence-based practice amodelofsocialworkpracticethat emphasizestheuseofthescientificmethodandscientificevidenceinmakingpracticedecisions.

Chapter3willexaminetheresearchprocessin socialworkandvariousfactorsthatcaninfluence thewaythatprocessiscarriedout.Chapter4will provideanoverviewofandcomparethethreecontrastingyetcomplementaryoverarchingmodelsof socialworkresearch:onethatusesquantitative methodstoproducepreciseandgeneralizablestatisticalfindings;onethatusesmoreflexible,qualitative methodstodelveintodeeperunderstandingsofphenomenanoteasilyreducedtonumbers;andonethat integratesquantitativeandqualitativeapproaches withinthesamestudy.

1 WhyStudy Research? INTRODUCTION

THESCIENTIFICMETHOD

OTHERWAYSOFKNOWING

RECOGNIZINGFLAWSINUNSCIENTIFIC SOURCESOFSOCIALWORKPRACTICE KNOWLEDGE

THEUTILITYOFSCIENTIFICINQUIRY INSOCIALWORK

REVIEWSOFSOCIALWORKEFFECTIVENESS

THENEEDTOCRITIQUERESEARCHQUALITY

COMPASSIONANDPROFESSIONALETHICS

UTILITYOFRESEARCHINAPPLIEDSOCIAL WORKSETTINGS

MAINPOINTS

REVIEWQUESTIONSANDEXERCISES

INTERNETEXERCISES

EPASCompetenciesforThisChapter

Competency1 DemonstrateEthicaland ProfessionalBehavior: Youwilllearnwhystudying researchispartofpreparingtobeethicalandprofessional inyoursocialworkpractice.

Competency4 EngageinPractice-Informed ResearchandResearch-InformedPractice: Asa researchtextthatemphasizespracticeapplications,allof itschaptersaddressaspectsofthiscompetency.

Competency9 EvaluatePracticewithIndividuals Families,Groups,Organizations,andCommunities: Youwilllearnwhystudyingresearchisanessentialpartof evaluatingpractice.

WhatYou’llLearninThisChapter Youmaybewonderingwhysocialworkstudentsare requiredtotakearesearchcourse.We’llbegintoanswer thatquestioninthischapter.We’llexaminethewaysocial workerslearnthingsandthemistakestheymakealong theway.We’llalsoexaminewhatmakesscientificinquiry differentfromotherwaysofknowingthingsandits utilityinsocialworkpractice.Wewillprefacethisand theremainingchaptersofthisbookbylistingthe competenciesrelevanttoeachchapterthatstudentsare expectedtodevelopaccordingtotheCouncilonSocial WorkEducationEducationalPolicyandAccreditation Standards(EPAS).Eachcompetencywillbeaccompanied byabriefstatementonitsrelevancetothechapter.

INTRODUCTION Socialworkers likedoctors,lawyers,nurses,or anyothertypeofprofessional needtoknow thingsthatwillmaketheirprofessionalpractice effective.Althoughitseemsreasonabletosuppose thatallsocialworkerswouldagreewiththatstatement,theywouldnotallagreeaboutthe best ways togoaboutlearningthethingstheyneedtoknow. Somemightfavorlearningthingsbyrelyingon whatmostoftheirteachers,supervisors,andmore experiencedsocialworkersingeneralagreeto betrue.Othersmightassertthatlearningthings throughwhattheyobserveandexperienceintheir professionalpracticeisatleastasvaluableasis learningaboutwhatotherrespectedsourcesagree tobetrue.

Bothofthesetwowaysofknowingthingshave valuenotonlyinguidingsocialworkpracticebut alsoinguidingdecisionsthroughoutourpersonal lives.Aswegrowup,wemustrelyonwhatthepeoplewerespecttellustokeepussafeandhealthy.We shouldn’tanddon’thavetoexperiencetheharmful orpainfuleffectsofdoingunsafeorunhealthythings beforewelearnnottodothem.Atthesametime,we learnotherthingsthroughourdirectexperienceand observation.

Thetwowaysofknowingthingsthatwe’ve beendiscussingaretermed agreementreality and experientialreality.Althougheachisinvaluablein guidingourpersonalandprofessionalbehavior, let’snowlookathowrelyingonthemexclusively canberisky.

AgreementReality Mostofwhatweknowisamatterofagreement andbelief.Littleofitisbasedonpersonalexperienceanddiscovery.Abigpartofgrowingupinany society,infact,istheprocessoflearningtoaccept whateverybodyaroundyou “knows” isso.

Youknowthatit’scoldontheplanetMars. Howdoyouknow?Unlessyou’vebeentoMars lately,youknowit’scoldtherebecausesomebody toldyouandyoubelievedwhatyouweretold.Perhapsyourphysicsorastronomyinstructortoldyou itwascoldonMars,ormaybeyoureadaboutit somewhere.

However,relyingexclusivelyonagreementrealitycanberiskybecausesomeofthethingsthat

everyoneagreesonarewrong.Forexample,at onetimeeveryone “knew” thattheworldisflat. Throughoutthehistoryofthesocialworkprofession,therehavebeenthingsthatmostsocialworkersandothermentalhealthprofessionalsagreedon thatwerenotonlywrongbutalsoharmful.

Inthemid-20thcentury,forexample,therewas widespreadagreementthatthemaincauseofschizophreniawasfaultyparentingorotherdysfunctional familydynamics.Havingwhatwascalleda schizophrenigenicmother waswidelyseenasamainreason whyachild perhapslaterasanadult eventually cametohaveschizophrenia.Suchmotherswereportrayedascold,domineering,andoverprotectivein waysthatdidnotpermittheirchildrentodevelop individualidentities.Nocompellingresearchevidence supportedtheseconcepts,buttheywerenonetheless widelyacceptedbymentalhealthpractitioners.Asa result,socialworkersandothermentalhealthprofessionalsoftendealtwiththefamilyasacauseofthe problemratherthandevelopatreatmentalliance withthefamily.Manyparentsconsequentlyreported feelingsofself-recriminationfortheillnessesoftheir offspring.Asyoucanimagine,thiswaspainfulfor manyparents.

Scientificresearchstudiesduringthe1970sand 1980sdebunkedthenotionthatschizophreniais causedbyschizophrenigenicmothersorotherdysfunctionalfamilydynamics.Somestudiesuncovered thebiologicalbasisofschizophrenia.Otherstudies showedhowpractitionerswhowereguidedbythe notionoffaultyparenting(orotherdysfunctional familydynamics)whentreatingpeoplewithschizophreniaandtheirfamilieswereactuallyincreasing theriskofrelapseandunnecessarilyexacerbating theburdenthatsuchfamilieshadtobearwhencaringfortheirsickrelative(Rubin&Bowker,1986).

Anotherexampleofineffectiveorharmfulprofessionalpracticesthatwereguidedbyagreement realityincludes “ScaredStraight” programs.These programswereoncepopularasaneffectivewayto preventfutureviolationsofthelawbyjuveniles.It wasthoughtthatbyvisitingprisonsandinteracting withadultinmates,juvenileswouldbesofrightened thattheirfearwoulddeterthemfromfuturecriminalbehavior.Butvariousscientificresearchstudies foundthatScaredStraightprogramsnotonlywere ineffectivebutactuallyincreasedtheriskofdelinquency(Petrosino,Turpin-Petrosino,&Buehler, 2002).

ExperientialReality Incontrasttoknowingthingsthroughagreement, wecanalsoknowthingsthroughdirectexperience andobservation.However,justasrelyingexclusivelyonagreementrealitycanberisky,socan relyingexclusivelyonexperientialreality.That’s becausesomeofthethingsthatweexperienceare influencedbyourpredilectionsthatarebasedon agreementsthatmayormaynotbeaccurate.

Let’stakeanexample.Imagineyou’reata party.It’sahigh-classaffair,andthedrinksand foodareexcellent.Youareparticularlytakenby onetypeofappetizerthehostbringsaroundona tray.It’sbreaded,deep-fried,andespeciallytasty. Youhaveacouple,andtheyaredelicious!You havemore.Soonyouaresubtlymovingaround theroomtobewhereverthehostarriveswitha trayofthesenibbles.

Finally,youcan’tcontainyourselfanymore. “Whatarethey?” youask. “HowcanIgetthe recipe?” Thehostletsyouinonthesecret: “You’ve beeneatingbreaded,deep-friedworms!” Your responseisdramatic:Yourstomachrebels,andyou promptlythrowupalloverthelivingroomrug. Awful!Whataterriblethingtoserveguests!

Thepointofthestoryisthatbothfeelingsabout theappetizerwouldbereal.Yourinitiallikingfor them,basedonyourowndirectexperience,wascertainlyreal,butsowasthefeelingofdisgustyouhad whenyoufoundoutthatyou’dbeeneatingworms. Itshouldbeevident,however,thatthefeelingofdisgustwasstrictlyaproductoftheagreementsyou havewiththosearoundyouthatwormsaren’tfitto eat.That’sanagreementyoubeganthefirsttime yourparentsfoundyousittinginapileofdirtwith halfawrigglingwormdanglingfromyourlips. Whentheypriedyourmouthopenandreached downyourthroattofindtheotherhalfofthe worm,youlearnedthatwormsarenotacceptable foodinoursociety.

Asidefromtheagreementswehave,what’s wrongwithworms?They’reprobablyhighinproteinandlowincalories.Bitesizedandeasilypackaged,they’readistributor’sdream.Theyarealsoa delicacyforsomepeoplewholiveinsocietiesthat lackouragreementthatwormsaredisgusting. Otherpeoplemightlovethewormsbutbeturned offbythedeep-friedbread-crumbcrust.

Analogiestothiswormexamplehaveabounded inthehistorysocialworkpractice(aswellasinthe

practiceofotherhelpingprofessions).Decades ago,forexample,practitionerswhobelievedinthe schizophrenigenicmotherconceptwerelikelytobe predisposedtolookfor,perceive,andinterpret maternalbehaviorsinwaysthatfittheiragreement reality.Wehaveknownclinicalpractitionerswho willlookforandperceiveevenfairlyinconsequential clientbehaviorsasevidencethattheirfavoredtreatmentapproachisbeingeffectivewhileoverlooking otherbehaviorsthatmightraisedoubtabouttheir effectiveness.Laterinthischapter,we’lldiscussthis phenomenonintermsoftheconceptofselective observation,whichisonecommonwayinwhich ouragreementrealityinfluencesourexperiential reality.

Reality,then,isatrickybusiness.Although whenwestartoutinlifeorinourprofessional careers,wemustinescapablyrelyheavilyonagreementrealityandexperientialrealityasstarting pointsfor “knowing” things,someofthethings you “know” may notbetrue.Buthowcanyou reallyknowwhat’sreal?Peoplehavegrappled withthatquestionforthousandsofyears.Science isoneofthestrategiesthathavearisenfromthat grappling.

THESCIENTIFICMETHOD Scienceoffersanapproachtobothagreementrealityandexperientialreality.Thatapproachiscalled the scientificmethod*.Whensocialworkersquestionthingsandsearchforevidenceasthebasisfor makingpracticedecisions,theyareapplyingthescientificmethod.Let’snowexaminethekeyfeatures ofthescientificmethod,beginningwithaprinciple thatrequireskeepinganopenmind.

AllKnowledgeIsTentativeandOpen toQuestion

Inourquesttounderstandthings,weshouldstrive tokeepan openmind abouteverythingthatwe thinkweknoworthatwewanttobelieve.In otherwords,weshouldconsiderthethingswecall “knowledge” tobe tentative and subjecttorefutation.Thisfeaturehasnoexceptions.Nomatterhow longaparticulartraditionhasbeenpracticed,no

*Wordsinboldfacearedefinedintheglossaryattheendofthe book.

Welearnsomethingsbyexperience,othersbyagreement.Thisyoungmanseems tobeintopersonalexperience.

matterhowmuchpoweroresteemaparticular authorityfiguremayhave,nomatterhownoblea causemaybe,nomatterhowcherisheditmaybe, wecanquestionanybelief.

Keepinganopenmindisnotalwayseasy.Few ofusenjoyfactsthatgetinthewayofourcherished beliefs.Whenwethinkaboutallowingeverythingto beopentoquestion,wemaythinkofold-fashioned notionsthatweourselveshavedisputedandthus patourselvesonthebackforbeingsoopenminded.Ifwehavealiberalbent,forexample,we mayfancyourselvesasscientificforquestioning stereotypesofgenderroles,lawsbanninggaymarriage,orpapaldecreesaboutabortion.Butarewe alsopreparedtohaveanopenmindaboutourown cherishedbeliefs toallowthemtobequestioned andrefuted?Onlywhenabeliefyoucherishisquestioneddoyoufacethetoughertestofyourcommitmenttoscientificnotionsoftheprovisionalnature ofknowledgeandkeepingeverythingopentoquestionandrefutation.

Replication However,itisnotonlyourbeliefsthatareopento question;alsotentativeandopentoquestionarethe findingsofscientificstudies.Becausethereareno foolproofwaystoguaranteethatevidenceproduced byscientificstudiesispurelyobjective,accurate, andgeneralizable,thescientificmethodalsocalls forthereplicationofstudies. Replication means duplicatingastudytoseeifthesameevidenceand conclusionsareproduced.Italsoreferstomodified replicationsinwhichtheproceduresarechangedin certainwaysthatimproveonpreviousstudiesor determineiffindingsholdupwithdifferenttarget populationsorunderdifferentcircumstances.

Observation Anotherkeyfeatureofthescientificmethodisthe searchfor evidencebasedonobservation asthe basisforknowledge.Theterm empirical refersto thisvaluingofobservation-basedevidence.Aswe

EarlBabbie

willseelater,onecanbeempiricalindifferentways, dependingonthenatureoftheevidenceandthe waywesearchforandobserveit.Fornow,rememberthatthescientificmethodseekstruththrough observedevidence notthroughauthority,tradition,orideology nomatterhowmuchsocialpressuremaybeconnectedtoparticularbeliefsandno matterhowmanypeoplecherishthosebeliefsor howlongthey’vebeenproclaimedtobetrue.It tookcouragelongagotoquestionfiercelyheld beliefsthattheEarthisflat.Scientificallyminded socialworkerstodayshouldfindthesamecourage toinquireastotheobservation-basedevidencethat supportsinterventionsorpoliciesthattheyaretold ortaughttobelievein.

Socialworkersshouldalsoexaminethenature ofthatevidence.Tobetrulyscientific,theobservationsthataccumulatedtheevidenceshouldhave been systematic and comprehensive.Toavoidovergeneralizationandselectiveobservation(errorswe willbediscussingshortly),the sample ofobservationsshouldhavebeen large and diverse.

Objectivity Thespecifiedproceduresalsoshouldbescrutinized forpotentialbias.Thescientificmethodrecognizes thatweallhavepredilectionsandbiasesthatcan distorthowwelookfororperceiveevidence.It thereforeemphasizesthe pursuitofobjectivity in thewayweseekandobserveevidence.Noneofus mayeverbepurelyobjective,nomatterhow stronglycommittedwearetothescientificmethod. Nomatterhowscientificallypristinetheirresearch maybe,researcherswanttodiscoversomething important thatis,tohavefindingsthatwillmake asignificantcontributiontoimprovinghumanwellbeingor(lessnobly)enhancingtheirprofessional stature.Thescientificmethoddoesnotrequirethat researchersdeceivethemselvesintothinkingthey lackthesebiases.Instead,recognizingthatthey mayhavethesebiases,theymustfindwaysto gatherobservationsthatarenotinfluencedby theirownbiases.

Suppose,forexample,youdeviseanewinterventionforimprovingtheself-esteemoftraumatizedchildren.Naturally,youwillbebiasedin wantingtoobserveimprovementsintheselfesteemofthechildrenreceivingyourintervention. It’sokaytohavethatbiasandstillscientifically inquirewhetheryourinterventionreallydoes

improveself-esteem.Youwouldnotwanttobase yourinquirysolelyonyourownsubjectiveclinical impressions.Thatapproachwouldengenderagreat dealofskepticismabouttheobjectivityofyour judgmentsthatthechildren’sself-esteemimproved. Thus,insteadofrelyingexclusivelyonyourclinical impressions,youwoulddeviseanobservation procedurethatwasnotinfluencedbyyourown biases.Perhapsyouwouldaskcolleagueswho didn’tknowaboutyourinterventionorthenature ofyourinquirytointerviewthechildrenandrate theirself-esteem.Orperhapsyouwouldadminister anexistingpaper-and-penciltestofself-esteemthat socialscientistsregardasvalid.Althoughneither alternativecanguaranteecompleteobjectivity, eachwouldbemorescientificinreflectingyour efforttopursueobjectivity.

Transparency Finally,thescientificmethodrequirestransparency byresearchersinreportingthedetailsofhowtheir studieshavebeenconducted.All proceduraldetails shouldbespecified sothatotherscanseethebasis fortheconclusionsthatwerereached,assesswhether overgeneralizationandselectiveobservationwere trulyavoided,andjudgewhethertheconclusions areindeedwarrantedinlightoftheevidenceand thewaysinwhichitwasobserved.

Thebox “KeyFeaturesoftheScientific Method” summarizesthesefeaturesandprovidesa handymnemonicforrememberingthem.

OTHERWAYSOFKNOWING Thescientificmethodisnottheonlywaytolearn abouttheworld.Aswementionedearlier,for example,wealldiscoverthingsthroughourpersonalexperiencesfrombirthonandfromthe agreed-onknowledgethatothersgiveus.Sometimes thisknowledgecanprofoundlyinfluenceourlives, suchaswhenwelearnthatgettinganeducationwill affecthowmuchmoneyweearnlaterinlifeorhow muchjobsatisfactionwe’lleventuallyexperience. Asstudents,welearnthatstudyinghardwillresult inbetterexaminationgrades.

Wealsolearnthatsuchpatternsofcauseand effectareprobabilisticinnature:Theeffectsoccur moreoftenwhenthecausesoccurthanwhenthey areabsent butnotalways.Thus,studentslearn

KEYFEATURESOFTHESCIENTIFICMETHOD Amnemonicforrememberingsomeofthekeyfeaturesofthescientificmethodistheword trout.Thinkof catchingoreatingadelicioustrout,1 anditwillhelpyourememberthefollowingkeyfeatures:

TTentative: Everythingwethinkweknowtodayisopentoquestionandsubjecttoreassessment, modification,orrefutation.

RReplication: Eventhebeststudiesareopentoquestionandneedtobereplicated.

OObservation: Knowledgeisgroundedinorderlyandcomprehensiveobservations.

UUnbiased: Observationsshouldbeunbiased.

TTransparency: Allproceduraldetailsareopenlyspecifiedforreviewandevaluationandtoshowthe basisofconclusionsthatwerereached.

1Ifyouareavegetarian,youmightwanttojustpicturehowbeautifulthesefishareandimaginehowmanyoftheirlivesyou aresaving.

thatstudyinghardproducesgoodgradesinmost instancesbutnoteverytime.Socialworkerslearn thatbeingabusedaschildrenmakespeoplemore likelytobecomeabusiveparentslateron,butnot allparentswhowereabusedaschildrenbecome abusivethemselves.Theyalsolearnthatseverementalillnessmakesonevulnerabletobecominghomeless,butnotalladultswithseverementalillnesses becomehomeless.

Wewillreturntotheseconceptsofcausalityand probabilitythroughoutthebook.Aswe’llsee,scientificinquirymakesthemmoreexplicitandprovides techniquesfordealingwiththemmorerigorously thandootherwaysoflearningabouttheworld.

Tradition Oneimportantsecondhandwaytoattemptto learnthingsisthroughtradition.Wemaytesta fewofthese “truths” onourown,butwesimply acceptthegreatmajorityofthem.Thesearethe thingsthat “everybodyknows.” Tradition,inthis senseoftheterm,hasclearadvantagesforhuman inquiry.Byacceptingwhateverybodyknows,you aresparedtheoverwhelmingtaskofstartingfrom scratchinyoursearchforregularitiesandunderstanding.Knowledgeiscumulative,andaninheritedbodyofinformationandunderstandingisthe jumping-offpointforthedevelopmentofmore knowledge.Weoftenspeakof “standingonthe shouldersofgiants”—thatis,ontheshouldersof previousgenerations.

Atthesametime,traditionmaybedetrimental tohumaninquiry.Ifyouseekafreshanddifferent understandingofsomethingthateverybodyalready understandsandhasalwaysunderstood,youmay beseenasafool.Moretothepoint,itwillprobably neveroccurtoyoutoseekadifferentunderstanding ofsomethingthatisalreadyunderstoodand obvious.

Whenyouenteryourfirstjobasaprofessionalsocialworker,youmaylearnaboutyour agency’spreferredinterventionapproaches.(If youhavebegunthefieldplacementcomponent ofyourprofessionaleducation,youmayhave alreadyexperiencedthisphenomenon.)Chances areyouwillfeelgoodaboutreceivinginstructions about “howwedothingsinthisagency.” You mightbeanxiousaboutbeginningtoworkwith realcasesandmightberelievedthatyouwon’t havetochoosebetweencompetingtheoriesto guidewhatyoudowithclients.Inconformingto agencytraditions,youmightfeelthatyouhavea headstart,benefitingfromtheaccumulatedpracticewisdomofpreviousgenerationsofpractitionersinyournewworksetting.Indeedyoudo. Afterall,howmanyrecentlygraduatedsocial workersareinabetterpositionthanexperienced agencystafftodeterminethebestintervention approachesintheiragency?

Butthedownsideofconformingtotraditional practicewisdomisthatyoucanbecometoocomfortabledoingit.Youmayneverthinktolookfor evidencethatthetraditionalapproachesareor

arenotaseffectiveaseveryonebelievesorforevidenceconcerningwhetheralternativeapproaches aremoreeffective.Andifyoudoseekandfind suchevidence,youmayfindthatagencytraditions makeyourcolleaguesunreceptivetothenew information.

Authority

Despitethepoweroftradition,newknowledge appearseveryday.Asidefromyourpersonalinquiries,throughoutyourlifeyouwillbenefitfrom others’ newdiscoveriesandunderstandings.Often, acceptanceofthesenewacquisitionswilldependon thestatusofthediscoverer.Forexample,you’re morelikelytobelievetheepidemiologistwho declaresthatthecommoncoldcanbetransmitted throughkissingthantobelievealaypersonwho saysthesamething.

Liketradition,authoritycanbothassistand hinderhumaninquiry.Inquiryishinderedwhen wedependontheauthorityofexpertsspeakingoutsidetheirrealmofexpertise.Theadvertisingindustryplaysheavilyonthismisuseofauthorityby havingpopularathletesdiscussthenutritional valueofbreakfastcerealsormovieactorsevaluate theperformanceofautomobiles,amongsimilartactics.Itisbettertotrustthejudgmentoftheperson whohasspecialtraining,expertise,andcredentials inthematter,especiallyinthefaceofcontradictory positionsonagivenquestion.Atthesametime, inquirycanbegreatlyhinderedbythelegitimate authoritywhoerrswithinhisorherownspecial province.Biologists,afterall,cananddomakemistakesinthefieldofbiology.Biologicalknowledge changesovertime.Sodoessocialworkknowledge, asdiscussedearlierregardingdebunkednotions aboutthecauseandtreatmentofschizophrenia.

Ourpointisthatknowledgeacceptedonthe authorityoflegitimateandhighlyregardedexperts canbeincorrectandperhapsharmful.Itistherefore importantthatsocialworkpractitionersbeopento newdiscoveriesthatmightchallengethecherished beliefsoftheirrespectedsupervisorsorfavorite theorists.

Alsokeepanopenmindaboutthenewknowledgethatdisplacestheold.It,too,maybeflawed, nomatterhowprestigiousitsfounders.Who knows?Perhapssomedaywe’llevenfindevidence thatcurrentlyout-of-favorideasaboutparental causationofschizophreniahadmeritafterall.

Thatprospectmightseemhighlyunlikelynow givencurrentevidence,butintakingascientific approachtoknowledge,wetrytoremainobjective andopentonewdiscoveries,nomatterhowmuch theymayconflictwiththetraditionalwisdomor currentauthorities.Althoughcompleteobjectivity maybeanimpossibleidealtoattain,wetrynotto closeourmindstonewideasthatmightconflict withtraditionandauthority.

Bothtraditionandauthority,then,aretwoedgedswordsinthesearchforknowledgeabout theworld.Theyprovideuswithastartingpointfor ourowninquiry.Buttheymayalsoleadustostartat thewrongpointorpushusinthewrongdirection.

CommonSense Thenotionof commonsense isoftencitedas anotherwaytoknowabouttheworld.Common sensecanimplylogicalreasoning,suchaswhen wereasonthatitmakesnosensetothinkthatrainbowscauserainfallsincerainbowsappearonlyafter therainstartsfallingandonlywhenthesunshines duringthestorm.Commonsensecanalsoimply widelysharedbeliefsbasedontraditionandauthority.Theproblemwiththissortofcommonsenseis thatwhat “everyoneknows” canbewrong.Long ago,everyone “knew” thattheEarthwasflat.It wasjustplaincommonsensesinceyoucouldsee nocurvaturetotheEarth’ssurfaceandsincehell wasbelowthesurface.Atonepointinourhistory, agreatmanypeoplethoughtthatslaverymade commonsense.Manypeoplethinkthatlaws againstgaysandlesbiansmarryingoradoptingchildrenmakecommonsense.Mostsocialworkers thinksuchlawsmakenocommonsensewhatsoever.Althoughcommonsensemightseemrational andaccurate,itisaninsufficientandhighlyrisky alternativetoscienceasasourceofknowledge.

PopularMedia Muchofwhatweknowabouttheworldislearned fromthenewsmedia.Wefirstlearnedaboutthe September11,2001,attackonthetwintowersof theWorldTradeCenterfromwatchingcoverageof thattragiceventontelevisionandreadingaboutit innewspapersandmagazinesandontheInternet. Thesamesourcesinformedusofthevictimsand heroesinNewYorkCity,Pennsylvania,and Washington,D.C.Theyprovidedinformationon

theperpetratorsoftheattackandagreatmany relatedissuesandevents.Wedidnothavetoconductascientificstudytoknowabouttheattackor havestrongfeelingsaboutit.Neitherdidweneed traditionorauthority.Wedidnothavetoexperiencetheattackfirsthand(althoughwereallydid experienceit andprobablywereatleastsomewhat traumatized bywhatwesawandheardonour televisionsets).

Althoughwecanlearnalotfromthepopular media,wecanalsobemisledbythem.Witness,for example,disagreementsbetweensomecablenews networksastowhichnetworkisreallymoretrustworthy,fair,andbalanced.Althoughmostjournalistsmightstriveforaccuracyandobjectivity,theyare stillinfluencedbytheirownpoliticalbiases some morethanothers.Somealsomightseekoutthe mostsensationalaspectsofeventsandthenreport theminabiasedmannertogarnerreaderinterest orappealtotheirprejudices(ratingsaffectprofits!).

Evenwhenjournalistsstriveforaccuracyin theirreportage,thenatureoftheirbusinesscan impedetheirefforts.Forexample,theyhavedeadlinestomeetandwordlimitsastohowmuchthey canwrite.Thus,whencoveringtestimonyatcity hallbyneighborhoodresidents,someofwhomsupportaproposedneweconomicdevelopmentplanin theirneighborhoodandsomeofwhomopposeit, theircoveragemightbedominatednotbyfolks likethemajorityofresidents,whomaynotbeoutspoken.Instead,theymightunintentionallyrelyon theleastrepresentativebutmostoutspokenand demonstrativesupportersoropponentsoftheproposeddevelopment.

Thentherearejournalistswhosejobsareto delivereditorialsandopinionpieces,nottoreport storiesfactually.Whatwelearnfromthemiscoloredbytheirpredilections.Theintentofsuchwritingisnottoprovideabalancedapproachbutto persuadereaderstosharetheirpositiononthe issues.

Thepopularmediaalsoincludefictionalmovies andtelevisionshowsthatcaninfluencewhatwe thinkweknowabouttheworld.Somefictional accountsofhistoryareindeededucational,perhaps informingusaboutAfricanAmericanswhofought fortheUnionduringtheCivilWarorsensitizingus tothehorrorsoftheHolocaustorofslavery. Others,however,canbemisleading,suchaswhen mostmentallyillpeopleareportrayedasviolentor

whenmostwelfarerecipientsareportrayedasAfricanAmericans.

Moreandmorethesedays,manyfolksget muchoftheirinformationfromtheInternet. DespitethewondersoftheInternetandtheimmediateavailabilityofatremendousarrayofuseful informationtherein,informationavailableonunscientificsitesisnotriskfree.PerhapsmostnoteworthyinthisregardistheWikipediawebsite. Wikipediaisafreeonlineencyclopediathatanyone canedit.AhumorousillustrationoftherisksinherentinallowinganyonetoedittheinformationavailableatthatsitewasreportedbyEveFairbanks (2008,p.5).InFebruary2008,duringtheheat ofthebattlebetweenHillaryClintonandBarack ObamafortheDemocraticParty’spresidential nomination,somebodyaccessedClinton’sWikipediapageandreplacedherphotowithapictureof awalrus.Perhapsinretaliation,thenextmonth,a ClintonsupporteralteredObama’sbiosothatit calledhim “aKenyan-Americanpolitician.” Also thatmonth,somebodyreplacedClinton’swhole pagewith “IthasbeenreportedthatHillary RodhamClintonhascontractedgenitalherpesdue tosexualintercoursewithanorangutan.” Obviously,theaboveWikipediaexampleis extreme,andunlessitsreadersdespisedClintonor wereimbibingsomethingpeculiarwhenaccessing theabovewebsite,theywouldnotbelievethatthe walruswasreallyClintonorthatshehadintercoursewithanorangutan.Butitdoesillustrate thatdespitethetremendousvalueoftheInternetandthefactthatwecanlearnmanyvaluable thingsfrompopularmedia,theydonotprovide anadequatealternativetoscientificsourcesof knowledge.

RECOGNIZINGFLAWSIN UNSCIENTIFICSOURCES OFSOCIALWORKPRACTICE KNOWLEDGE Scientificinquirysafeguardsagainstthepotential dangersofrelyingexclusivelyontradition,authority,commonsense,orthepopularmediaasthe sourcesofknowledgetoguidesocialworkpractice.Italsohelpssafeguardagainsterrorswe mightmakewhenweattempttobuildourpracticewisdomprimarilythroughourownpractice experiencesandunsystematicobservations.Scientificinquiryalsoinvolvescriticalthinkingsothat wecanspotfallaciesinwhatothersmaytellus abouttheirpracticewisdomortheinterventions theyaretouting.Let’snowlookatsomecommon errorsandfallaciesyoushouldwatchoutforand atsomeofthewaysscienceguardsagainstthose mistakes.

Overgeneralization Whenwelookforpatternsamongthespecific thingsweobservearoundus,weoftenassumethat afewsimilareventsareevidenceofageneralpattern.Probablythetendencytoovergeneralizeis greatestwhenthepressureishighesttoarriveata generalunderstanding.Yetovergeneralizationalso occurscasuallyintheabsenceofpressure.Wheneveritdoesoccur,itcanmisdirectorimpede inquiry.

Imagineyouareacommunityorganizerand youjustfoundoutthatariothasstartedinyour community.Youhaveameetingintwohours thatyoucannotmiss,andyouneedtoletothers atthemeetingknowwhycitizensarerioting. Rushingtothescene,youstartinterviewingrioters,askingthemfortheirreasons.Ifthefirst tworioterstellyoutheyaredoingitjustto lootsomestores,youwouldprobablybewrong inassumingthattheother300areriotingjust forthatreason.

Tofurtherillustrateovergeneralization,imagine yourpracticeinstructorbringsinaguestlecturerto talkaboutapromisingnewinterventionthatsheis excitedabout.Althoughshehasasizablecaseload andhasbeenprovidingtheinterventiontoquitea fewclients,supposeherlecturejustfocusesonan

in-depthreportofoneortwoclientswhoseemed tobenefitenormouslyfromtheintervention.You mightbewronginassumingtheinterventionwas equallyeffective oreveneffectiveatall withher otherclients.

Scientistsguardagainstovergeneralizationby committingthemselvesinadvancetoasufficiently largesampleofobservations(seeChapter15). Thereplicationofinquiryprovidesanothersafeguard.Aswementionedearlier,replicationbasicallymeansrepeatingastudyandthencheckingto seeifthesameresultsareproducedeachtime.Then thestudymayberepeatedunderslightlyvariedconditions.Thus,whenasocialworkresearcherdiscoversthataparticularprogramofserviceina particularsettingiseffective,thatisonlythebeginning.Istheprogramequallyeffectiveforalltypesof clients?Forbothmenandwomen?Forbothold andyoung?Amongallethnicgroups?Woulditbe justaseffectiveinotheragencysettings?Thisextensionoftheinquiryseekstofindthebreadthandthe limitsofthegeneralizationabouttheprogram’s effectiveness.

Totallyindependentreplicationsbyother researchersextendthesafeguards.Supposeyou readastudythatshowsaninterventiontobeeffective.Later,youmightconductyourownstudyof differentclients,perhapsmeasuringeffectiveness somewhatdifferently.Ifyourindependentstudy producedexactlythesameconclusionastheone youfirstread,thenyouwouldfeelmoreconfident inthegeneralizabilityofthefindings.Ifyou obtainedsomewhatdifferentresultsorfoundasubgroupofclientsamongwhomthefindingsdidn’t holdatall,you’dhavehelpedtosaveusfrom overgeneralizing.

SelectiveObservation Onedangerofovergeneralizationisthatitmay leadtoselectiveobservation.Onceyouhaveconcludedthataparticularpatternexistsanddevelopedageneralunderstandingofwhy,thenyou willbetemptedtopayattentiontofutureevents andsituationsthatcorrespondwiththepattern. Youwillmostlikelyignorethosethatdon’tcorrespond.Figure1-1illustratesthecircularfashionin whichovergeneralizationcanleadtoselective observationandselectiveobservationcanleadto overgeneralization.Thisfigureintroducesyouto