ListofFigures

1.1.Shakespeare’sfunerarymonument,HolyTrinityChurch, Stratford-upon-Avon,withdetailsofmemorialplaqueandofobit. 9

1.2.EngravingofShakespeare’sfunerarymonumentbyWenceslaus Hollar,inWilliamDugdale, TheAntiquitiesofWarwickshire Illustrated (1656),withdetailofobit. 10

1.3.EdmondMalone’smanuscriptcorrectionofWilliamOldys’s noteonShakespeare’sbirthdate,inMalone’sinterleavedcopy ofGerardLangbaine, AnAccountoftheEnglishDramatick Poets (1691).©BodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford. 11

1.4.EngravingofShakespearebyWilliamMarshall,frontispiece toJohnBenson’s Poems:WrittenbyWil.Shake-speare.Gent. (1640).©FolgerShakespeareLibrary. 15

1.5.ShakespeareasclassicbyMichaelvanderGucht,frontispiece toallsixvolumesofNicholasRowe’seditionofShakespeare (1709).©BodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford. 31

1.6.CorneilleasclassicbyGuillaumeValletafterAntoinePaillet, frontispieceto LeThéaˆtredeP.Corneille (1664).©Bridgeman Images. 33

2.1. AChartofBiography with2000lifelinesbyJosephPriestley, engravedbroadsheet,2ʹ×3ʹ(1765).©LibraryCompanyof Philadelphia. 40

2.2.TheplaysinchronologicalorderasascertainedbyEdmond Malone,in ThePlaysofWilliamShakspeare,ed.Samuel Johnson,GeorgeSteevens,andIsaacReed,10vols.(1785),I,288. 45

2.3.“ACatalogue,”in Mr.WilliamShakespearesComedies,Histories, &Tragedies (1623).©BodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford. 55

2.4.“ACatalogue,”in Mr.WilliamShakespearesComedies,Histories, &Tragedies (1685).©FolgerShakespeareLibrary. 57

3.1.ThefirstfacsimilesofthesignaturesonShakespeare’swill, in ThePlaysofWilliamShakspeare,ed.SamuelJohnsonand GeorgeSteevens,10vols.(1778),I,after200. 65

3.2.i.Idealizedengravingofpendanttagwithsignatureandseal affixedtotheBlackfriarsGatehousemortgagedeed,in The PlaysandPoemsofWilliamShakspeare,ed.EdmondMalone, 10vols.(1790),I,after192. 67

3.2.ii.PendanttagwithsignatureandsealaffixedtotheBlackfriars Gatehousemortgagedeed(1613).©FolgerShakespeareLibrary. 67

3.2.iii.CopybyWilliam-HenryIrelandoftheidealizedengravingof thependanttag(i.above),inSamuelIreland, Miscellaneous PapersandLegalInstruments (1796),preface. 67

3.3.DrawingbyWilliam-HenryIrelandofthe“Quintinseal” appendantfromtheFraserdeed,W.H.IrelandPapers, 1593–1824,MS,Hyde60(4).HoughtonLibrary,Harvard University. 75

3.4.FacsimilesbyWilliam-HenryIrelandofthe“Original”and “Fictitious”autographsofShakespeare, TheConfessionsof William-HenryIreland (1805)afterpreface. 77

3.5.Chronologicallistofthe“LivesofthePoets,”preparedby EdmondMaloneforhistranscriptionofJohnAubrey’s BriefLives,MS,Eng.Misc.d.26,1v.©BodleianLibraries, UniversityofOxford. 89

3.6.Chronologicallistofthe“LivesofProseWritersandOther CelebratedPersons,”preparedbyEdmondMaloneforhis transcriptionofJohnAubrey’s BriefLives,MS,Eng.Misc. d.26,75v.©BodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford. 91

3.7.SketchbyJohnAubreyoftheescutcheonandhoroscopeofSir WilliamPetty, BriefLives,MS,Aubrey6,f.12v.©Bodleian Libraries,UniversityofOxford. 92

3.8.DraftbyJohnAubreyofhisownLifeandhoroscope, Brief Lives,MSAubrey7,f.3.©BodleianLibraries,Universityof Oxford. 96

4.1.Dedicationpage, Shake-spearesSonnets (1609). 98

4.2.Titlepage,ornamentalheader, Shake-spearesSonnets (1609). 99

Introduction

Foragoodtwocenturiesafterhisdeath,Shakespearehadnobiography.Themakingsofonewerenotavailable.Nochronologyhadbeen devisedbywhichtointegratetheeventsofhislifewiththewritingof hisworks.Norwasthereanarchiveofprimarymaterialsonwhichto baseaLife.Inaddition,theonlyworkbyShakespearewritteninthefirst person,theSonnets,hadyettobecriticallyeditedandincorporatedinto hiscanon.Before1800,thebiographydeemedessentialtoourunderstandingandappreciationofShakespearesimplydidnotexist.Thisbook isaboutShakespeare’ssurvivalforthosefirstmanygenerationswithout one.

HowcouldthereeverhavebeenatimewhenShakespearehadno Life?Surelyafterthepublicationofthegrandfolioof Mr.William ShakespearesComedies,Histories,&Tragedies(1623)readerswouldhave wantedtoknowaboutthemanwhowrotethosethirty-sixplays.How elsetodosobutbyfindingoutabouthislife?Theseventeenth-century noticesabouthimthatcirculatedmaybedisappointinglyscant,recordinglittlemore,forexample,thanthatShakespearewasborninStratford, wroteplays,andwasburiedinthetownofhisnativity.Allthesame, aretheynotthefirststirringsofthebiographicalimpulse?Intheeighteenthcentury,NicholasRoweprefaceshis1709editionofShakespeare withaforty-pageessaymodestlytitled SomeAccountoftheLife,&c.of Mr.WilliamShakespear anditisreproducedthroughouttheeighteenth century.This,too,advancesthebiographicalproject.Notonlydoesthis accountincreasethestoreofwhatRoweterms“PersonalStor[ies],”it alsoforthefirsttimeconsultsanofficialdocument,theStratfordparish register.Shouldn’ttheseearlyeffortsbeviewedassteps,howeversmall andfaltering,inthedirectionofwhatwenowhave:astandardnarrativeofShakespeare’slife,basedondocumentsanddrawingonhis works?

IndeedthatishowthehistoryofShakespeare’sbiographyhasbeen told,andinsuperably,bySamuelSchoenbaum.His Shakespeare’sLives, firstpublishedin1970,hasbeensupersededonlybyhisownrevised editiontwentyyearslater.Itcoversthesametwocenturiesthataremy focushere,butthroughoutitassumeswhatIquestion:theexistence fromthestartofthebiographicalimpulse,whatheterms“thequestfor knowledgeofShakespearetheman.”Inhiscomprehensiveaccount,the fragmentarynoticesandanecdotalclustersoftheseventeenthandeighteenthcenturiesarealladvancingtowardthatknowledge.Thequest takesa“quantumleap”forwardwiththeworkoftheeditorandbiographerEdmondMalonewhosecontributiontoShakespeare’sbiography,accordingtoSchoenbaum,isunrivaled:“Malonefoundoutmore aboutShakespearethananyonebeforeorsince.”Hisfindingsfillupthe 500-pagesofMalone’s“masterly LifeofShakspeare,”intendedasthefirst volumeofhisposthumouslypublishededition, ThePlaysandPoemsof WilliamShakspeare (1821).Atlonglast,aproperbiographyhadarrived toprefacetheworks.Itsarrival,forSchoenbaum,wasnonetoosoon: “[H]owdesperatelyneededthatbiographywas!”1 ShakespearewithoutaLife exemptsthefirsttwocenturiesafter Shakespeare’sdeathfromthatdesperateneed.Nothingresemblinga biographyappearsattheforefrontofShakespeare’s1623folio,reproducedthreetimesduringtheseventeenthcentury.InsteadofaLife, elegiacnoticesofShakespeare’sdeathprecedetheplays.Onlythedate ofhisdeathisgiven,asifitweretheonlyoneofimport.Emphatically posthumous,themassivefoliovolumepresentsitselfasamonument, abibliographic tome thatservesasamonumental tomb preservingthe deceasedpoet’sliteraryremains.Soprefaced,theplaysappeartohave emergednotfromShakespeare’slifebutinconsequenceofhisdeath. EventheDroeshoutengravingonthetitlepageseemsoddlyinanimate, lessaportait,perhaps,thananopen-eyeddeathmask.

Twocenturiesafterthe1623Folio,aneditionofShakespeare’splays andpoemswaspublishedthatplacesanextensiveLifeatitsforefront. Theeditionorderstheplayschronologically,accordingtothedates whenShakespeare,bytheeditor’sreckoning,hadwrittenthem.Not onlythebiographybuttheentireeditionisstockedwithdocuments,

inappendices,addenda,andannotations,allrelatinghowevertangentiallytoShakespeare.Italsoincludesthe1609 Sonnets inanapparatus thatlinksthemtoShakespeare’slife.2 Thisistheposthumous1821editionofMalone,thescholarcreditedwithhavinguniquelyadvancedthe questforbiographicalknowledge.Butbymyaccount,nosuchquest wasyetunderwayforhimtoadvance.Notonlyistherenocontinuity betweentheearlieraccountsandMalone’sbiography:thetwoaremutuallyexclusive.IndeedthebeginningsofMalone’sbiographycanbeseen inhiscopiousannotationstoRowe’s SomeAccountoftheLife inMalone’sfirsteditionofShakespeare(1790)wherehesystematicallyrefutes virtuallyeveryincidentRowerelates.3 Thefacts,dates,anddocuments hehasdeployedtoinvalidateRowe’sreportsin1790formthebasisof the LifeofShakspeare thatheprefixestohiseditionof1821.4

Mychallengeinthisbookistwofold:first,toproposethatwhatwe understandbybiographywasneitherdesirednorattempteduntillate intotheeighteenthcentury;second,todemonstratethatbylookingfor faintintimationsofwhatisnowthenorm,weeffacetheverydifferentprioritiesonceatwork.Eachofmyfourchaptersfocusesonthe earlyabsenceofwhatisnowindispensable:abiographicalnarrative,a chronologyforthelifeandtheworks,anarchiveorprimarymaterials, andacanonwiththe1609 Sonnets atitsheart.Myendthroughoutis tobringintoviewwhatthelaterfixationonbiographyhaseffectively phasedout.

Myfirstchapter,“ShakespearewithoutaLife(1564–1616),”explains whatImeanbya“Life”byreferencingthebiographicalformulamade standardbythe DictionaryofNationalBiography (1885–1900):two datesconjoinedbyanendashandenclosedinparentheses:“Shakespeare,William(1564–1616).”(Thetwodatessymbolizetheendpoints ofthelife,thelongdashthelinearnarrativeconnectingthem,andthe bracketsthefree-standingautonomyoftheunit.)InthecaseofShakespeare,noneoftheserequirementscanbemetuntillongafterhisdeath: thebirthdateislatetobefixed,thechronologicalcontinuumevenlater tobeascertained,andacoherentlinearnarrativenotattempteduntil Malone.Shakespeareisknowninsteadthroughascatteringofundated episodicincidents.Yettheseanecdotesor“traditionalstories”givea strongimpressionofShakespeare.Repeatedlytheycatchhiminan

actoftransgression,breakingthelawsofthelandoroversteppingthe boundsofcivility.Whilenosupportforsuchoffensivebehaviorcanbe foundinthehistoricalrecord,confirmationexistselsewhere:inearly criticismofShakespeare’sstyle.Invariablyinthisearlyperiod,hisplays arecriticizedas“irregular”or“unruly,”theresultofhisrusticeducation thatlefthimshortofthemasteryoftheGreekandRomanmodelsand tonguesexpectedofapoet.Thewaywardnessascribedtohislifeisin keepingwiththesignature“extravagance”ofhisworks—untilthenext century,whenthelatterwasrevalorizedasoriginalityandgeniusandits authorassignedanappropriatelyrespectablecharacter.

Chapter 2,“Shakespeare’sLifeline,”focusesontheeighteenth-century noveltyofthechronologicaltimeline.AseventsinShakespeare’slife couldbedatedbydocumentsandsituatedonacontinuum,so,too,could hisplays,oncethedatesoftheircompositioncouldbeplausiblyascertained.Whenreducedtothecommondenominatorofdates,theplays couldbefittedintotheprogressingtrajectoryofhislifetime.Beforethe playswerechronologized,thepresidingcategoryhadbeentheancient oneofgenre,asforegroundedinboththetitleandtheorganizationofthe 1623Folio.ThatShakespeare’splaysseemedtofloutthegenres,thathistorieshadnoclassicalprecedent,onlymadeformorechallengingcritical debate.Eighteenth-centuryeditionsintroducerefinementstotheFolio’s tripartitedivision,butneverwithregardtowheretheplaysbelonged inShakespeare’slife.Thetragedies,forexample,aresubdividedaccordingtothegenreoftheirsource,sothat“TragediesfromHistory”are differentiatedfrom“TragediesfromFable.”Whenchronologicalorder isobserved,inthetragediesaswiththehistories,itisthatofaplay’s settinginworldhistoryratherthanthatofthetwodecadesinwhich Shakespeareisthoughttohavewrittenhisplays.

Asthechronologicalstructureforabiographicalnarrativewaslacking,so,too,weretheprimarymaterials.Chapter 3,“Shakespeare’s Archive,”concernstheexhaustivesearchattheendoftheeighteenthcenturyformaterialsinShakespeare’sownhand:forautographmanuscripts,correspondence,evenShakespeare’spocketnotebook.Interveninggenerationsarecastigatedfortheirfailuretopreserve andtransmitwhatevenscholarsimagineasaphysicalrepositoryof somekind.Andyetthefantasizedchestneversurfaces—indeeditmost

likelyneverhadexisted—exceptthroughtheinitiallyacclaimedforgeries ofWilliam-HenryIreland.AllthatcouldberecoveredinShakespeare’s handwereseveralvariablesignaturesandassorteddocumentsinthe handsofhiscontemporaries,thelatteratoneremove,asitwere,fromhis ownhand.Butearliermodesofrecord-keepingexisted,thatneitherprioritizedprimarymaterialsnormistrustedmediation,ascanbeseenin GerardLangbaine’salphabetizedinventoryofplays, AnAccountofthe EnglishDramatickPoets (1691)andJohnAubrey’squirkymanuscript collectionoflives,nowknownas BriefLives (c.1676–92).

Thefinalchapter,“The‘deceasèdI’ofthe1609 Sonnets,”concernsthe absenceoftheworkthatbecamethemostcloselyaffiliatedwithShakespeare’sbiography.ItisalsotheonlyworkbyShakespearethatexpressly aspirestoeverlastinglife,ironicallyasitturnsout,foritcamecloseto extinction.The“eternallines”ofthe1609 Sonnets wereoutofprintfora centuryandnotfullyincorporatedintothecanonuntilalmostacentury afterthat.Formostofthatlongstretch,thesonnetswereensconcedin aneclecticmiscellanypublishedin1640, Poems:WrittenbyWil.Shakespeare. Thoughdeemedspuriousandworthlessby1800,thesonnetsin the1640formatenduredlongerthantheyhadintheauthentic1609 quarto.Whatgavethesonnetsintheir1640makeovertheirpowerto endure?Certainlyitwasnotthepromiseofaccesstothelifeofthepoet. Throughitsdistancingandgeneralizingrubrics,the1640miscellany renderedthesonnetsquiteimpersonal.Howthendidthe1640 Poems secure,atleastforatime,afutureforthem?Howdidtheycapturewhat theSonnetspresumeforthemselves:theliteraryattentionofagesyet unborn?AndmighttheSonnetsthemselves,withtheirmanygestures ofself-cancellation,haveimaginedtheirownsurvivalwithout“thehand thatwritthem”?

Allfourchaptersareintendedtodrawattentiontowhatislostwhen thepastisimaginedasanticipatoryofthepresent.Biography,accordingtosuchanexpectation,wasalwaysintheprocessofcominginto being.Theattractionofsuchanapproachisobvious.Onceithasatelos, inthiscaseabiographyofShakespearethatfollowstheprogrammatic (1564–1616)outline,theapproachcastsitsstartingpointasfarbackas possible,heretotheearliestnoticesaboutShakespeare,andextendsits trajectoryforwardtowarditspresentfamiliaruse.Thisconstrualofthe

pastlookswonderfullycomprehensive;everythingbetweenthenand nowtakestheformfirstofincipientandthenofdevelopingversionsof thepresent.Thepastistherebynotonlyostensiblypreservedbutalso maderelevant.Thereis,however,astrictbiastothisapparentinclusivity.Forthetrajectorycarriesforwardonlywhatcanbeconstruedinits owncontemporaryimage.Whatresistsit,fallsbythewayside.

ShakespearewithoutaLife proceedsanotherway.Itlooksnotforearlierindicationsofpresentimperativesbutforwhatthoseimperatives haveoccluded.Whatisthereintheanecdotethatthebiographycannotcapture?Whatcriticalpurchaseislostwhentheorderinwhich Shakespearewrotehisworksreplacesthatoftheclassicaldramatic genres?Whatdocompendiaofferthattheauthorialarchivecannot recognize?Whathappenstotheattractionsofamiscellanyintheinsatiablequestforthefirst-person?Toaskthesequestionsistobeginto loosenthegripbiographyhaslongheldovertheworks.Itistoentertain afactthatotherwiseseemsalmostunthinkable.Foralongspellbetween 1616and1800,Shakespeare’splaysandpoemswerereproduced,discussed,andvaluedwithoutabiographicalnarrative.Notonlywerehis worksnotdesperatelyinneedofabiography;theyweresurvivingthen perfectlywellwithoutone—perhapsallthebetterforthelackofone.

ShakespearewithoutaLife(1564–1616)

Forovertwocenturiesafterhisdeathin1616,ShakespearehadnoLife. LetmebeginbydefiningwhatImeanbyLife:Imeanacontinuous narrativefrombirthtodeath,chronologicallyorganizedandsupported bydocuments.Nosuchnarrativeprefacedthefourseventeenth-century folioeditionsofhiscollectedplays, Mr.WilliamShakespearesComedies,Histories,&Tragedies (1623,1632,1663/4,and1685).Instead,the frontmatterofallfourmassivefoliovolumesdwelledonhisdeath.Not untilthefirsteighteenth-centuryeditionarethefolio’selegiacpreliminariesreplacedwithaprefatoryLife.NicholasRowe’ssix-volumeoctavo editionof TheWorksofMr.WilliamShakespear (1709)openswitha forty-pageessay,SomeAccountoftheLife&c.ofMr.WilliamShakespear, andthatessaycontinuestobereproducedinasuccessionofShakespeare editionsupthroughtheendofthecentury.1 ButRowe’sprefatoryLifeof Shakespeareisquiteunlikethebiographiesthatsubsequentlymadetheir wayintothestandardeditionsofShakespeare’sCompleteWorks.It piecestogetherdiscreteanecdotesandcommentsratherthanattemptingacoherentnarrative,paysscantattentiontochronology,andrelies onwhathasbeensaidaboutShakespearewithoutrecoursetodocuments andrecords.

MydefinitionofaLifecouldbestillmoreconcise.Shakespearehadno Lifethatconformedtothebracketedbiographicalformulathatappears inthischapter’stitle:“(1564–1616).”Theformulaisabstract:twodated endpoints,ofbirthandofdeath,areconnectedbyalongdashthatstands forthelifetimebetweenthem;parenthesessetitoffasaself-contained unit.Theabbreviationisnowstandard,butitbecamesoonlyafterthe publicationof DictionaryofNationalBiography (DNB)attheendof thenineteenthcentury(1885–1900).Eachofthatpublication’s30,000 entriesopenswiththesubject’snamefollowedbytheparentheticallife dates.Theensuingbiographicalnarrativeforeachofthoseentriesisa

dilationofthatformula.Ithasbeentheconventionalabbreviationfor aLifeeversince,includinginthe OxfordDictionaryofNationalBiography (ODNB),completedin2004and,whencombinedwithitsonline supplements,containingalmosttwiceasmanyentriesasthe DNB.

Untiltheturnofthetwentiethcentury,therewasnosuchconvention ofbiographicalnotationinEngland.Itdoesnotfeatureinearlybiographicalcompendia,likeJohnAubrey’s BriefLives,SamuelJohnson’s LivesofthePoets,orthecomprehensive BiographiaBritannicaofEminentPersons,theprecursorofthe DictionaryofNationalBiography. Noristheformulatobefoundonearlymoderntombstonesormonuments.InhisstatelyfoliovolumeofAncientFunerallMonuments(1631), JohnWeeverrecordedsomeonethousandinscriptionsontombsand gravestones,mainlyinsoutheastEngland,buttheygiveonlytheyear ofdeathorburial;thesameistrueoftheepitaphsJohnStowlistsin his TheSurveyofLondon (1598). 2 Insteadofadaterange,wefind hic iacet, quiobit, quisobit,or obiitAnnodomini followedbythedeathdate, oroccasionally aetatis followedbytheageatdeath.Thisiscustomary throughouttheseventeenthandearlyeighteenthcenturies.Ifthebirthdateappears,asisthecaseonEdmundSpenser’smonument,itisthe resultofalaterinscription.3 AnthonyWood’sremarkablefolio Athenae Oxonienses claimsonitstitlepagetogive“TheBirth,Fortune,Preferment,andDeath”ofalltheauthorsandprelateswhohavebeeneducated atOxford,butby“Birth”hemeansnotdateofbirth,butparentage, lineage,orplaceofbirth.4

Birthdatesarelackingduringthisearlyperiodnotbecausetheyare nowheretobefound.AsAdamSmythhasnoted,byThomasCromwell’s edictof1538,therecordingofbothbaptismalandburialdatesinparish registerswasmandatory.5 Thebaptismalandburialdatesforanyparishionerwholivedintoadulthoodwouldalsobeseparatedbyrecordsof interveningparishchristenings,marriages,andburials.Shakespeare’s twodates,forexample,intheStratfordparishregister,areseparated byovereightypages(5rto46v).HisbaptismisenteredinLatinon 26April1564:“GuilielmusfiliusJohannesShakspere”;hisburialin English:“25thofApril1616.”6 Foranyindividualbaptizedandburied

inthesameparish,itwouldhavetakenonlyalittlepatiencetoascertain theextentofalifespanbyconjoiningthetwodates.Butthereappearsto havebeennoincentivetodoso.Thedeathdateiswhatmattered:thedate markingthecut-offpointbetweenthisworldandthenext,betweenlife andafterlife.7 Shakespeare’sburialsitebecamealandmarkshortlyafter hisdeath;thereisnorecordofhisbirthplaceonHenleyStreetuntila surveyornotesitin1759.8

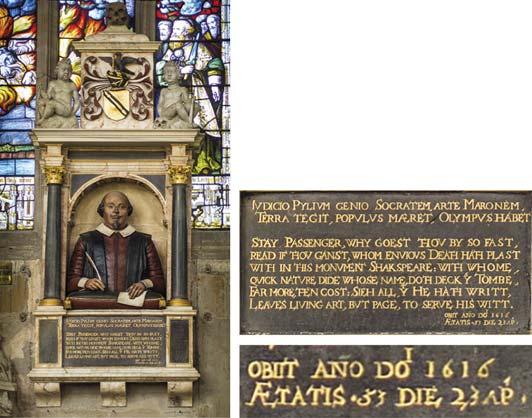

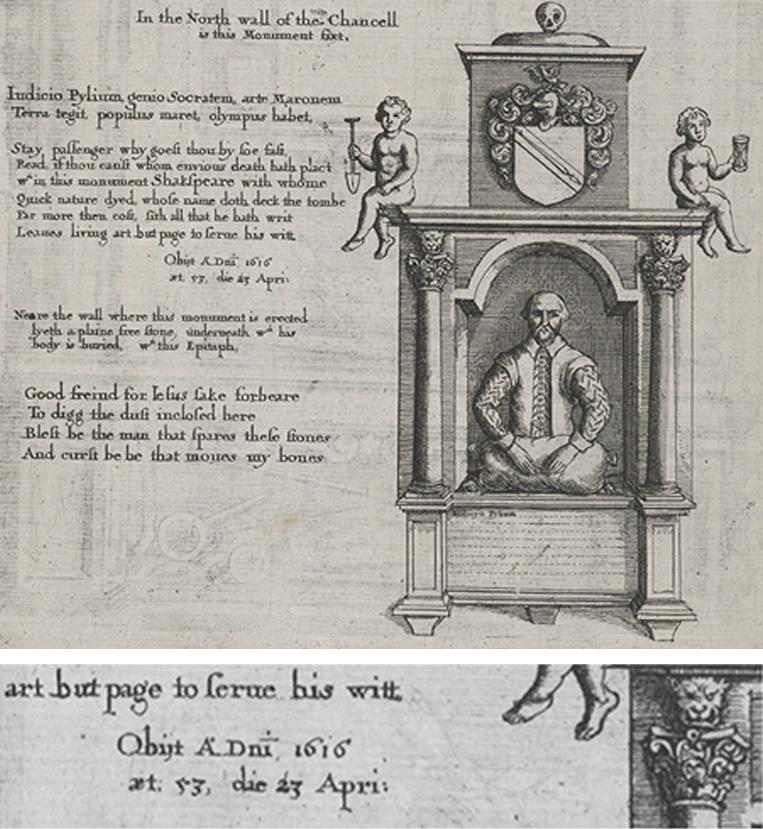

WhilenodatesappearonShakespeare’sgravestoneinHolyTrinity ChurchinStratford,thereisoneonthebronzeplaqueatthebaseofthe funerarymonumentaboveit(Fig. 1.1).

Fig.1.1 Shakespeare’sfunerarymonument,HolyTrinity Church,Stratford-upon-Avon,withdetailsofmemorialplaque andofobit.

Afewdecadeslater,thatinscriptionandthemonumentwerereproducedinanengravingbasedonthedrawingoftheantiquarianWilliam Dugdale(Fig. 1.2).

TheengravingcommemoratesShakespearenotastheWarwickshire poetwholivedfrom1564to1616,butastheonewhodiedin1616at theageof53.HisbirthdatedoesappearonShakespeare’smonument

Fig.1.2 EngravingofShakespeare’sfunerary monumentbyWenceslausHollar,inWilliam Dugdale, TheAntiquitiesofWarwickshire Illustrated (1656),withdetailofobit.

erectedin1741inthe“Poets’Corner”ofWestminsterAbbey,butitwas notaddeduntil1977.

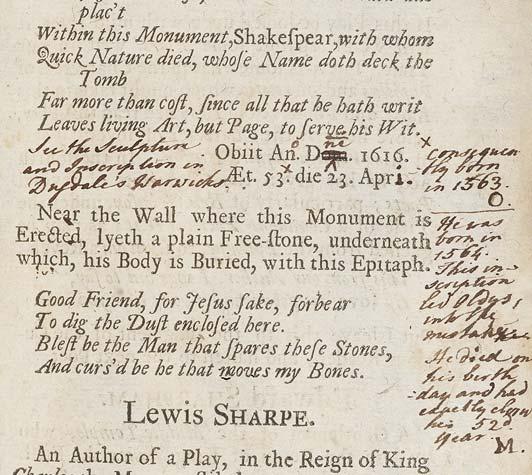

EarlybiographicalentriesforShakespearealsosupplyonlythedate ofdeath.9 Inhis BriefLives,JohnAubreydoeshisbesttoobtaindates ofbirth,forthepurposeofcastinghoroscopesforhissubjects,whathe terms“genitures”or“nativities,”thoughhesucceedsforonlyafraction ofhissubjects.10 Twoearlycompendiaoflivesgivenoyearevenfor Shakespeare’sdeath,onlythecentury.In TheHistoryoftheWorthiesof England (1662)ThomasFullerrecords:“Hedyed AnnoDomini 16… andwasburiedatStratforduponAvon.”11 WilliamWinstanley,inhisThe LivesoftheMostFamousEnglishPoets (1687),reproducesFuller’sellipsis:“ThisourfamousComediandied, An.Dom. 16__andwasburied at Stratford upon Avon.”12 GerardLangbaine,inhis AnAccountofthe EnglishDramatickPoets(1691),liftsShakespeare’sdeathdatefromDugdale’sengraving:“Ihavenownomoretodo,buttocloseupall,withan AccountofhisDeath;whichwasonthe23dofApril,An.Dom.16.…”13

WhenannotatinghiscopyofLangbaine’ssurveyofEnglishdramatists,theantiquaryWilliamOldysnotesthatLangbaine’sentryon ShakespearederivesfromDugdaleandthencalculatesShakespeare’s birthdateonthatentry’sbasis.Bysubtracting“Aet.53”from“ObitAn. Dom.1616,”Oldysarrivesat1563.14 Severaldecadeslater,Edmond MalonetranscribesOldys’snotesintohisowninterleavedcopyof Langbaineandinsertsmanyofhisown,includingacorrectionofOldys’s calculation:“Hewasbornin1564.[Dugdale’s]inscriptionledOldysinto themistake”(Fig. 1.3).15

Fig.1.3 EdmondMalone’smanuscriptcorrectionofWilliam Oldys’snoteonShakespeare’sbirthdate,inMalone’sinterleaved copyofGerardLangbaine, AnAccountoftheEnglishDramatick Poets (1691).©BodleianLibraries,UniversityofOxford.

Bytheeighteenthcentury,theStratfordparishregisterrecordingthe dateofShakespeare’sbaptismhadbeenconsulted.Rowe,inpreparationforwritinghis1709LifeofShakespeare,hadsenttheactorThomas BettertontoWarwickshire“onpurposetogatherwhatRemainshe could”ofShakespeare.ItisinRowe’s SomeAccountoftheLife,&c. that

themonthandyearofShakespeare’sbirthisfinallyfirstmadeknown: “Bornat Stratford upon Avon, in Warwickshire in April 1564.”16

ButMalonewantsthedayofShakespeare’sbirthaswellasthemonth andyear.Thedaysuppliedbytheregister—April26,1564—isof Shakespeare’sbaptism.Fortheabsenceofthisdesiderata,Malonefaults theperiod’srecord-keepingpractices:“Theomittingtomentionofthe dayofthechild’sbirthinbaptismalregisters,isagreatdefect,asthe knowledgeofthisfactisoftenofimportance.”Yetasfarastheparishwas concerned,theimportantdatewouldhavebeenthatinwhichinfants receivedthesacramentthatadoptedthemintotheChristiancommunity.WhatMalonewantswasneverdocumented:theprecisestarting pointofhissubject’slife.Hebegrudginglymusttakethedayofbirthon trust,fromoneofhiscorrespondents,theStratfordvicarandschoolmasterJosephGreene:“WilliamShakespearewasborninStratfordupon Avon, probably onSunday,Aprilthe23d,1564.”Ashelaterreflects,“I havesaidthisonfaithofMr.Green,but quaere, howdidMr.Green ascertainthisfact?”17

ThatMaloneshouldbesokeentofixbothdatesisnoaccident, forheisthefirsttoattemptacontinuous,chronological,anddocumentedLifeofShakespeare,comprehendinghisworksandextendingfromhisbirthtohisdeath.Asweshallsee,hefallsfarshort ofthatidealandhisbiographyconsistingof500denselyannotated pagesoftextandover200pagesofappendices,thoughnodoubtconsultedasareference,wasnotreprinted.18 Thefirstbiographyfully torealizeMalone’saspirationwasbySidneyLeewho,inhiscapacity asfirstassistanttotheeditorofthe DNB andfinallyasitseditor, wroteatotalof870entries.In1898hecontributesaforty-nine-page entryon“Shakespeare,William(1564–1616),”thelongestbyfarin theDictionary. Lee’sentry,organizedchronologically,formsthebasis ofwhathewouldexpandthefollowingyearintohis500-page ALifeofWilliamShakespeare.In1916,afterfiveeditions,hisbiography wasenlarged,revised,andproclaimedthestandardbiography.19 Itisalso theprototypeforthebiographicalaccountsthatprefacemoderneditions oftheCompleteortheCollectedWorksofShakespeare.Butthroughout mostoftheeighteenthcentury,theLifeofShakespeareprefixedtothe workshasnouseforthe DNB’sepitaphicorbiographicformula.Rowe’s

SomeAccountoftheLife,&c. iswithoutcontinuityordevelopmentand nodocumentssubstantiatetheincidentsitrelates.

ThefirstcomprehensivecollectionofShakespeare’splays,the1623 Folioanditsthreeseventeenth-centuryreprints,isprefacednotwith anaccountofShakespeare’slifebutwithseveralnoticesofhisdeath,in proseandverse.20 Thepreliminariesstressthevolume’sposthumousstatus.Consistently,theyseverthedeadauthorfromtheworkshehasleft behind.Thetitle-pageengravingofShakespeare,generallyconsidered “stiff”and“lifeless,”hasbeenlikenedtoaneffigyonasepulchralmemorial.IthasrecentlybeensuggestedthatDroeshout’sportraitisintended toevokeadeathmask,andthatthepoemacrossfromit,“TotheReader,” attributedtoBenJonson,awakenstheetymologicallinkbetweenthe engraveror“Grauer”whocutthebrassandthegravemaker.21 Jonson’s shortekphrasticversedivertsthereader’sattentionfromthegraven imageofShakespearetotheprintedtextofhisbook:“Reader,looke/ NotonhisPicture,buthisBooke.”22 JohnHemingesandHenryCondell, Shakespeare’stheatricalcolleaguesandthecompilersoftheFolio,insist onthesameseparationinboththeirdedicationtotheEarlsofPembroke andMontgomeryandintheiraddresstothereader:theauthorisdead andburied;hisworks,however,liveonwithintheprotectivecoversof thebook.Ideally,thecompilersmaintain,Shakespearewouldhaveoverseenitspublication:“Ithadbeneathing,weconfesse,worthietohave benewished,thatthe Author himselfehadliv’dtohavesetforth,and overseenhisownewritings.”Nothavingdoneso,likeamanwhohasdied intestate,histwocolleaguestakeituponthemselvestosecurethefuture ofhisdramaticlegacy:“hebydeathdepartedfromthatright,weprayyou donotenviehisFriends,theofficeoftheircare,andpaine,tohavecollected&publish’dthem.”HemingesandCondelldutifullyperform“an officetothedead.”Withhisphysicalbodyinterred,theirdutyistosafeguardtheliterarycorpushehasleftbehind.Thecorpusthatsurviveshim hassufferedinhisabsence:“abus’d,”“expos’d,”“maimedanddeformed”: scatteredlikethedismemberedbodyofOrpheusorthemangledremnantsofOsiris.Butthroughhisexecutors’solicitude,thatbrokenand dispersedcorpushasbeenmadewholeagain,“cur’d,andperfectoftheir

limbes,”nowenclosedwithintheprotectivecoversofthemightyFolio, thetombofthevoluminoustome.23

Stillmoreisneededtosecurethesurvivalofhisliteraryremains,and againthepostmortemcaesuraisemphasized.Duringtheauthor’slifetime,thetitleddedicateesofthevolume,theEarlsofPembrokeand Montgomery,hadlookedafterboththeparentauthorandhispoetic issue:backthenthey“prosequtedboth[hisworks],andtheirAuthour liuing.”Butnowwith“ourAuthournolongerliving,”hispatronsmust attendtohissurvivingissue:“wehope,(that[theplays]out-liuinghim, andhenothavingthefate,commonwithsome,tobeexequtortohis ownwritings)youwillusethelikeindulgencetowardthem,youhave doneuntotheirparent.”24 Itisnolongertheauthorwhoneedspatronage,butthepublicationthatwillsecurethesurvivalofhisdramatic issue.Insum,Shakespeareisdeadandgone.Longlive“whathehas left,”the“remainesofyourservantShakespeare”:hisComedies,Histories, &Tragedies.

Bycontributingelegiestothebook’sfrontmatter,thefellowpoets ofthedeceasedalsoperform“anofficetothedead,”mourning Shakespeare’sdeparturewhilewelcomingthesurvivalofhiswriting.The tributesarelesscommendatoryverses,astheyareoftencalled,than commemorative.25 Theyarewritten inmemoriam: “Tothememoryof mybeloued,TheAuthor”(Jonson);“TothememorieofM.W.Shakespeare”(Mabbes);“TothememoryofthedeceasedAuthour”(Leonard Digges).HughHolland’schiasmiclinenicelyencapsulatesthevolume’s premise:“fordoneare Shakespeares dayes:/Hisdayesaredone.”26 The1632Foliointroducestwomoreelegies,bothunattributed,“Upon theEffigiesof…Shakespeare”and“AnEpitaphon…Shakespeare.”27 OntheclosingleafofacopyoftheFirstFolio,itsearlyowner inscribedanadditionalthreeepitaphs:“AnEpitaphonMr.William Shakespeare”;“Anotheruponthesame”;“anEpitaph(vponhisToombe stoneincised).”28

AsthemassivefoliohadcollectedShakespeare’sfar-flungplaysin1623 and1632,soaverysmalloctavo, Poems:WrittenbyWil.Shake-speare, purportedtodothesameonareducedscalewithhispoemsin1640,collectingversesthathadappearedindifferentpublicationsassociatedwith Shakespeare’sname.29 Itspublisher’sdesiretoaffiliatetheoctavowith

theFolioisapparentinitsfrontispiece(Fig. 1.4):anengravingbasedon theDroeshoutportraitontheFolio’sfrontispiece,nowlookingevenless alivethanintheoriginal,withaghostlyaureolebehindhishead:

Fig.1.4 Engravingof ShakespearebyWilliam Marshall,frontispieceto JohnBenson’s Poems: WrittenbyWil. Shake-speare.Gent. (1640). ©FolgerShakespeare Library.

“ThisShadowisrenownedShakespear’s,”readstheinscription.

Likethefolios,too,theoctavoaimstoattendtothe“officesofthedead” bygatheringtheauthor’sliteraryremainssothatthepoemsmightenjoy “proportionaleglory,withtherestofhis everlivingWorkes.”30 Elegiac tributesenclosethepoemsattributedtoShakespeare,twoeulogiesat thefront(byLeonardDiggesandJohnWarren)andthreeattheend (byJohnMilton,WilliamBasse,andananonymouspoet).Here,too, theversesemphasizethedistinctionbetweenthedeceasedpoetandhis survivingworks.InLeonardDigges’seulogy,Shakespearethe“deceased man”issurvivedbyhisworksintheformnotofprintbutofthestage:by

thehostofravishingpersonae,amongthemBrutus,Iago,Falstaff,Beatrice,Benedict,and“Malvogliothatcrossegarter’dGull.”Milton,inhis “AnEpitaph ontheadmirableDramatickePoet,WilliamShakespeare,” imaginestheworkslivingoninstillanotherlocus:inreaders’hearts, wherehislineswillbedeeplyimpressedor“Sepulcher’d.”Thefocus ofthemostwidelydisseminatedoftheelegiesfromeithercollectionis onthelocationofShakespeare’sphysicalbody.WilliamBasse’s“Onthe DeathofWilliamShakespeare,whoDiedinAprill, Anno.Dom.1616” referencesboththeWestminstertombofChaucer,Spenser,andBeaumont,whereShakespearedoesnotlie,andtheStratfordmonument, wherehedoeslie,theelegy’slinesatranscriptionoftheepitaphic requiescatinpace:“Underthiscarvedmarbleofthineowne,/Sleeperare TragoedianShakespeare,sleepealone.”31

Thepreliminariestoboththe1623Folioof Mr.WilliamShakespeares Comedies,Histories,&Tragedies andthe1640octavoof Poems:Written byWil.Shake-speare.Gent. featurenohomagetoShakespeare’slife.Nor doestheonlyfrontmatterofanotherversecollection,the1609quartoof Shakes-peare’sSonnets.AsChapter4willdiscuss,thequarto’sdedication issettoresembleanepitaphinstone,thoughatthetimeofitspublication in1609,Shakespearewasverymuchalive.Allthreepublicationsopenby foregroundingShakespeare’sdecease,markingoffdifferentdestinations forthemanandhiswork,theformerenclosedbythetombandthelatter bythetome.32 Thelifeoftheoneendsin1616,whilethatoftheothers beginswiththedateofpublication:1623,1640,1609respectively. WithoutaprefatoryLife,thereisnoinvitationtoreadtheensuingdramaticandpoeticcontentbiographically.Thekeydateisof publication,thedatewhentheplaysorpoemstakeonalifeinprint; theirdateofissueisindependentoftheirauthorialgenesis.“[N]owthat theauthorisnolongerliving,”astheFolioputsit,hisworkscansurvive ontheirown.Rescuedbytheeffortsoftheirsolicitouscompilersand sanctionedbythetitlesoftheirtwopowerfulpatrons,theplaystaketheir leaveoftheauthor,muchasthesoulafterdeathdepartsfromthebodyin thehopeofcrossingthethresholdtoeternallife.Thepoetryalsoaspires toimmortality,oratleastitsqualifiedworldlyequivalent:survivaluntil doomsday,asthecoupletofsonnet55asserts:“So,tillthejudgmentthat yourselfarise,/Youliveinthis,anddwellinlovers’eyes.”33

Whenwesay“Shakespeare,”wemightintendeitherthepersonor hiscorpus.The1623Folioandthe1640octavo,however,distinguish betweenthetwo:thelifeofoneisover;thelifeoftheotherendures. Ars longa,vitabrevis.Attheportaltotheirpublication,theworksaresevered fromShakespearebydeathratherthansuturedtohimbyaLife.

In1709Shakespeare’sworkswerepublishedforthefirsttimewitha preliminaryLife.NicholasRowe’seditionof TheWorksofMr.William Shakespearbeginswithhisforty-pageessaySomeAccountoftheLife,&c. ButhisLifecertainlydoesnotsatisfymyworkingdefinition.Atthestart ofhisaccountRowegivesthedateofShakespeare’sbaptismfromthe parishregister;atitsendhetranscribeshisageatdeathfromthemonument,butwhatliesbetweenthosedatesisnot“thefirstattemptata connectedbiographyofShakespeare,”asSamuelSchoenbaumclaimsin Shakespeare’sLives. 34 Rowe’sfocusisonShakespeare’sworkinglife,the periodinwhichhewasactive(floruit or fl.),beginningwithhisdeparturefromStratfordtoLondonandendingwithhisreturn.Betweenthese twoundatedterminiareincidentsrelatingtoShakespeare’sencounters inLondon,alsoundated.Rowerelatesthemnotinchronologicalorder, butintheorderofthesocialrankofthepersonsShakespeareencounters. ThefirstistheQueen,thenSouthampton,andthencomethe“privatemen”:Spenserfirst,thenJonsonandhistribe,whosemembersare alsolistedinorderofrank:SirJohnSuckling,SirWilliamDavenant, SirEndymionPorter,theclericJohnHales,andlastofall,BenJonson (onceapprenticedtoabricklayer).Rowe’sanecdotesarenowfamiliar andyettheirstructuralsimilarityhasgoneunremarked.Innoneofthem istheredevelopment.Shakespeare’sbehaviorremainsunchanged—or ratherhis misbehavior:againandagainhebreakssocial,legal,and ethicalprotocols.Andeachoffencehassomeformofliteraryoutcome.

Rowe’sfirstanecdotetellsofthe“Misfortune”thatlaunchesShakespeare’sliterarycareer.InStratfordheiscaughtpoachingdeer,oras Roweputsitlessglamorously,“robbingaPark”or“Deerstealing” inan“illCompany”of“youngFellows”—andrepeatedly,“morethan once”.35 ThelandownerprosecutesShakespeare,whocompoundsthe offencewithadefamatoryballadprotestinghispunishment.Theballad

isso“verybitter”thatthelandownerredoubleshisprosecution,forcingShakespearetofleehisnativeStratfordforLondon.Rowechooses hiswordscarefullytodescribeShakespeare’sinfraction:hecallsit“an Extravagancethathewasguiltyof.”“Extravagance”heresticksclose toitsLatinroots(extra,beyond + vagari, towander),asisevidentin JohnKersey’s ANewEnglishDictionary (1702),whereitisdefinedas “wanderingbeyondtheduebounds”andgiventhefollowingsynonyms: “disordinate,”“irregular,”“wild,”“savage,”“furious.”36 Asweshallsee,in theanecdotesShakespearerepeatedly,indeedchronically,goes“beyond theduebounds.”Bytrespassingandstealing,heoverstepsthelimits ofthelaw,ashedoesagainwithhislibelousballad,conjecturedtobe hisfirstliteraryeffort.37 Thisoccasion,Roweaddswithhisusualdelicacy,temporarily“putaBlemishupon[Shakespeare’s]goodManners” andobligedhimtoleaveWarwickshireand“forsometime,shelterhimselfin London.”SamuelJohnsonismoredirect:“terrourofacriminal prosecution”forcedhisflight.38

AshiswritingcareerbeganwithoffenceinStratford,sodoesitend there,alsoinoffence.“[S]omeYearsbeforehisDeath”(xxxv),Rowe tellsus,inagatheringoffriendsandneighbors,oneofhisclosest, aMr.Combe,wellknownforhis“WealthandUsury”(xxxvi),asks Shakespeare—“inalaughingmanner”—towritehisepitaph,eagerto knowhowhewillberemembered.Shakespeareobliges,buthardlyin thegenialspiritoftherequest.Heextemporizesanepitaphthatgives Combefirstonlyatenpercentchanceofsalvation(theusuriousrateat whichCombehadbeenlending)—“TisaHundredtoTen,hisSoulisnot sav’d”—andthendropsthattonochanceatall,forCombeisalreadyin hell:“IfanyManask,WholiesinthisTomb?/Oh!ho!quoththeDevil, ’tismyJohn-a-Combe”(xxxvi).Itisabreachofdecorum,tobesure,and nodoubtcastsapalloveraconvivialoccasion.Itisalsoaterribleway totreatafriend.Rowecharacteristicallyrefrainsfromdirectcensure, thoughhisconcludingstatementtellswherehissympathieslie:“[T]he SharpnessoftheSatyrissaidtohavestungtheMansoseverely,that heneverforgaveit.”Laterageshavedonetheirbesttoturnbothofthese “personalstor[ies]”(i)toShakespeare’sadvantage,arguing,forexample, thatinstealingdeer,Shakespearewasprotestingenclosurelawsorthat indamningCombe,hewasexcoriatingthepracticeofusury.ButRowe’s

Shakespearehasnosuchpoliticalorsocialconscience.Hiscareerbegins andendsininjurytoothers,resultinginalibelousballadatthestartand ablasphemoussatireattheend.Betweenthesetwotellingoffencesare moreofthesame.

Eventohisqueen,Shakespeareisinsolent,ifnotinsubordinate.She, displeasedwithhishavinggivenhisoldfatroguethenameoftheProtestantmartyrSirJohnOldcastle,“waspleas’dtocommandhimtoalter it.”Hedoesalterit,buttoanameofequalrankandvirtue,anotherSir John,aKnightoftheGarterandwarhero,SirJohnFalstaff.“Thepresent Offencewasindeedavoided,”Roweallows,thoughnotwithoutreservation:“Idon’tknowwhethertheAuthormaynothavebeensomewhatto blameinhissecondChoice”(ix).Shakespearemayhaveobeyedtheletterofhercommand,butcertainlynotitsintentofprotectingherknights’ reputation.

Withhispatron,theEarlofSouthampton,comesanothertaleof immoderation.Inanactof“profuseGenerosity,”Southamptongivesthe dramatistathousandpounds:“ABountyverygreat,andveryrareatany time,”addsRowe.Yetthisinordinatesumisnot,asmightbeexpected fromapatron,toencourageShakespeare’sliteraryendeavors.Rather,it is“toenable[Shakespeare]togothroughwithaPurchasewhich[the Earl]heardhehadamindto.”Roweleavesthereaderwonderingwhat Shakespearemighthavehadthemindtobuyforsuchanexorbitantsum. PerhapsRoweintendstohintatitwhenhetellswhatthesumcould purchaseinhisownday:itis,Rowementions,“almostequaltothatprofuseGenerositythepresentAgehasshewntoFrenchDancersandItalian Eunuchs”(x).39

AmongtheanecdotesnotincludedinRoweisonerecordedin Shakespeare’slifetimebyJohnManningham,thenstudyinglawatthe InnsofCourt.InhisdiaryentrydatedMarch13,1601,hetellshow ShakespearepreemptedRichardBurbage’slatenighttrystwithafemale admirer:William“athisgame”whenRichard’sarrivalwasannounced, justifiedhisprecedencewiththequip,“WilliamtheConquerorwas beforeRichardtheThird.”40 Alateranecdote,firstnotedbyJohnAubrey, alludestoanotherillicitliaison.Shakespeare,accordingtoAubrey, injourneyingtoandfromLondontoStratford,wouldstopoffata tavernwherethevintner’swife,“averybeautifullwoman,andofa

verygoodwittandofconversationextremelyagreable”wasWilliam Davenant’smother.41 Thesecircumstancesgaverisetotherumor, fosteredbyDavenanthimself,thatDavenantwasnotonlyShakespeare’s namesakeandprotégébutalsohisillegitimateson.Thusadulterycould beaddedtothelitanyofShakespeare’soffences:robbery,libel,treason (indisobeyinghismonarch’scommand,andblasphemy.Inthiscontext,itseemsonlyfittingthattheallegedcauseofShakespeare’sdeath shouldbeintemperance.JohnWard,vicarofStratfordparishfrom1662, jottedinhisnotebooksthat“Shakespeare,DraytonandBenJonsonhad amerrymeeting,anditseemsdranktoohard,forShakespearediedof afevertherecontracted.”42 Aningloriousdeath,tobesure,butexcess ofdrinkandhighbloodpressurearecertainlyinkeepingwithalifetimeofincontinence.So,too,perhaps,isthemaledictioncarvedon hisgravestone,reputedtohavebeencomposedbyShakespeareshortly beforehisdeath,damning—inthenameofJesus,noless—whatever haplesssextonweretobechargedwithmakingroomfornewcorpses: “cursedbehethatmovesmybones.”43 Iftheepitaphwereindeedby Shakespeare,itwouldconstitutetheonlywritingwehaveinhisown personbesidestheSonnets.Itwouldalsoqualifyashislastpieceof writing,displacingthemorepropitious TheTempest,longheldtobe Shakespeare’svaledictorywork.44

Butwhatmotivatestheseconsistentlynegativecharacterizations? Certainlynotthedocumentaryrecord.Itsuggestsjusttheopposite, atleastasitisavailableandinterpretednow.AsStephenGreenblatt observes,“Thefactthattherearenopolicereports,noprivycouncil orders,indictments,orpost-morteminquests”suggeststhatShakespeare “possessedagiftforstayingoutoftrouble.”45 (Inshort,hadhebeenless law-abiding,hewouldhaveleftmorerecordsbehind.Unlikesomany ofhisplayhousecohort—Marlowe,Kyd,Nashe,Jonson,Middleton,and Dekkerallspenttimeinprison—Shakespeareavoidedscrapeswiththe law.46 Whendatedbiographicalnarrativesreplacethediscreteanecdotes,Shakespeare’scharactertakesonanewrespectability.Malone’s biography, TheLifeofWilliamShakspeare,intendedfromitsinception “toweavethewholeintooneuniformandconnectednarrative,”sets outtoshowthatShakespeare“fromhisyouthupwards,demonstrated thatrespectabilityofcharacterwhichunquestionablybelongedtohim

inafterlife.”47 Itsaim,atleastintheory,wastofollowatrajectoryin whichhisdevelopingtalentasadramatistismatchedbygradualacquisitionofproperty,literaryacclaim,socialstatus,andappreciationand affectionoffamily,colleagues,andfriends:alifewelllivedandjustly rewarded.

So,thequestionremains:whyistheanecdotalShakespeareatsuch variancefromtheShakespeareoflaternarratives?

Shakespeare’scharacterintheseanecdotesmaybeatoddswiththedocumentaryrecord,butitisverymuchinkeepingwithhiswriting,as assessedbyhisearlycritics.“Extravagant,”“unruly,”and“irregular”crop uprepeatedlyincriticismofhisplays.Roweissolicitousnottobeseen tocontributetothiscritique:“Iwouldnotbethoughtbythistomean, thathisFancywassolooseandextravagant,astobeIndependentonthe RuleandGovernmentofJudgment”(vii).Andyetherepeatedlysuggeststhesame.HenotesthatShakespearetookhisplotsashefindsthem inhissources—ramblingromancesandsprawlingchronicles—without attendingto“thefitDisposition,Order,andConduct”requiredofadramaticplot(xxvii).HechargesTheMerchantofVenicewithoffending“the RulesofProbability”with“thatextravagantandunusualkindofBond” thatstipulatesapoundoffleshfordefaultingonaloan(xx).TheTempest istheexceptiontoShakespeare’slegendaryneglectoftheunities:“the UnitiesarekepttherewithanExactnessuncommontotheLibertiesof hisWriting”(xxiii).OnlywhenShakespearequitsthenaturalworldis hisextravaganceavirtue:thenhe“giveshisImagination anentireLoose andraiseshisFancytoaflight aboveMankindandthe Limits ofthe visibleworld”(xxii,italicsadded).Thus,Roweapplaudsthefaeriesof AMidsummerNight’sDream,thespritesof TheTempest,thewitches of Macbeth,theghostin Hamlet asexamplesofthe“beautifulExtravagancewhichweadmirein Shakespear”(iii),ajudgmentthatastricter neoclassicist,CharlesGildon,foundbafflinglyself-contradictory:“I cannotimagine;nordoIunderstandwhatismeantby Beautiful Extravagance.”Forpoetryunregulatedby“theRulesofArt,”andthereforeexceedingtheboundsofnature,“canneverbe Beautiful but Abominable.”48