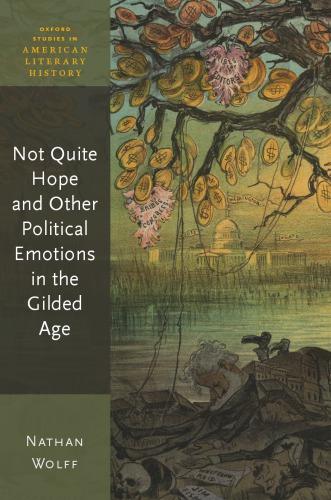

Te Principle of Political Hope

Progress, Action, and Democracy in Modern Tought

LOREN GOLDMAN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goldman, Loren, author.

Title: Te principle of political hope : progress, action, and democracy in modern thought / Loren Goldman.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifers: LCCN 2022030134 (print) | LCCN 2022030135 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197675823 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197675830 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Political sociology. | Hope—Political aspects. | Idealism. | Utopias. | Kant, Immanuel, 1724–1804—Political and social views. | Bloch, Ernest, 1880–1959—Political and social views. | Peirce, Charles S. (Charles Sanders), 1839–1914—Political and social views. | James, William 1842–1910—Political and social views.

Classifcation: LCC JA76 .G566 2023 (print) | LCC JA76 (ebook) | DDC 306.2—dc23/eng/20220816

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022030134

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022030135

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197675823.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

Politics without hope is impossible . . . it is hope that makes involvement in direct forms of political activism enjoyable; the sense that “gathering together” is about opening up the world . . . . Hope is crucial to the act of protest: hope is what allows us to feel that what angers us is not inevitable, even if transformation can sometimes feel impossible. Indeed, anger without hope can lead to despair or a sense of tiredness produced by the “inevitability” of the repetition of that which one is against.

But hope is not simple about the possibilities of the future implicit in the failure of repetition . . . hope involves a relationship to the present, and to the present as afected by its imperfect translation of the past . . . Te moment of hope is when the “not yet” impresses upon us in the present, such that we must act, politically, to make it our future.

Sara Ahmed, Te Cultural Politics of Emotion

Look, I don’t have a lot of hope for this world. In the face of the climate change emergency, the kinds of people that are in the major power positions in our universe . . . the rise of right-wing forces, the miserable corruption and deprivation that neoliberalism has contributed to much of the postcolonial world, the massive pile up of humanity in global slums, and the seeming endurance of capitalism beyond, beyond, so far beyond when it should have given way to something else, it’s hard to have hope. I think we need grit, responsibility and determination instead of hope.

Wendy Brown, “Where the Fires Are”

1. Kant, Practical Belief, and the Regulative Idea of Progress

2. Bloch and Latent Utopia

3. The Logic and Vitality of Ends in Peirce and James

4. Dewey and Democratic Experimentation

Acknowledgments

I have racked up many intellectual debts in the course of writing this book. It began as a dissertation at the University of Chicago, where I had the good fortune of working under the supervision of Patchen Markell, Bob GoodingWilliams, John P. McCormick, and Robert Pippin. Early versions of its claims were vetted in that vigorous intellectual community; I thank Julie Cooper, Wout Cornelissen, John Dobard, Joe Fischel, Tomas Fossen, Andreas Glaeser, W. David Hall, Yusuf Has, Gary Herrigel, Hans Joas, Jonathan Lear, Jennifer London, J.J. McFadden, Chris Meckstroth, Justin Modica, Glenn Most, Sankar Muthu, Jennifer Pitts, Shalini Satkunanandan, Jade Schif, Bill Sewell, Joshua Sellers, Lisa Wedeen, and Linda Zerilli. As a junior fellow at the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion, I learned the value of transcending even without heavenly transcendence; special thanks are due to William Schweiker and Slava Jakelić. Conversations with friends and colleagues elsewhere further informed my perspective; I thank Philip Deen, Steve Fishman, Pauline Kleingeld, Michael Lamb, Daniel Lee, Alex Livingston, Inder Marwah, Lucille McCarthy, and Marc Stears. Even further back, at Yale, Frankfurt, and Oxford, where its seeds were frst planted, I thank Erik Butler, Duncan Chesney, Jerry Cohen (RIP), Michael Freeden, Axel Honneth, Rahel Jaeggi, Boris Kapustin, Owen McLeod, Gillian Peele, Mark Philp, Michael Rosen, Alan Ryan, Martin Saar, Michael Schmelzle, Howard Stern, Kirk Wetters, Andrew Williams, and Allen Wood.

Te work was signifcantly revised and expanded during postdoctoral fellowships at Rutgers University’s Center for Cultural Analysis and the University of California at Berkeley’s Department of Rhetoric, both sites of amazingly fruitful interdisciplinarity. At Rutgers, I thank Steve Bronner, Laura Brown, Richard Dub, Chris D’Addario, Ann Fabian, Jonathan Farina, Jonathan Kramnik, William Galperin, Andy Murphy, Louis Sass, Derek Schilling, and Emily Van Buskirk. At Berkeley, I thank Chris Ansell, David Bates, Mark Bevir, Ari Bryen, Greg Castillo, Marianne Constable, Felipe Gutterriez, Jake Kosek, Leslie Kurke, Su Lin Lewis, Ramona Martinez, Paul Rabinow, Mark Sandberg, Jonathan Simon, Michael Wintroub, and the Townsend Center for the Humanities. At Ohio University, where

I subsequently spent three years as a visiting professor, I thank Sami Abdelkarim, Alyssa Bernstein, Judith Grant, Kyle Jones, Nicole Kaufman (whose intellectual generosity is infnite), Brandon Kendhammer, Tehama Lopez, Andrew Ross, Caitlin Ryan, Kathleen Sullivan, and Julie White.

At the University of Pennsylvania, an earlier version of the book was workshopped with Amy Allen, Joshua Dienstag, and George Shulman, whose questions, objections, and suggestions helped shape its fnal form. My colleagues in political theory are an extraordinary group, full of scholarly brio and critical cheer, and it has been a joy to work alongside Roxanne Euben, Jef Green, Nancy Hirschmann, Ellen Kennedy, Anne Norton, Adolph Reed, and Rogers Smith; Jef, Anne, and Roxanne each read and commented on this book’s complete penultimate draf. Two graduate students deserve special thanks: Troels Skaudhauge acted as the book workshop’s amanuensis and Rosie DuBrin compiled the index; both are formidable minds and regular interlocutors. Tank you also to my other colleagues in political science, especially departmental chairs past and present, Anne Norton, Nicholas Sambanis, and Michael Jones-Correa, as well as Osman Balkan, Warren Breckman, Audrey Jaquiss, Greg Koutnik, Carlin Romano, Sophia Rosenfeld, and Gabe Salgado. It has been humbling to have Bruce Kuklick take me under his wing in pragmatist matters, let alone enthusiastically read and comment on this and other manuscripts. A Fall 2019 visiting fellowship at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin allowed me to put the fnishing touches on the book; thank you to Rahel Jaeggi for the invitation. Matt Shafer is a Covid-era colleague whose presence at Penn, even if mainly virtual, added much to my scholarly life.

Earlier versions of parts of this work were presented at workshops at University of California at Berkeley, Bryn Mawr College, University of Chicago, Leiden University, Ohio State University, Ohio University, University of Pennsylvania, Rutgers University, and University of California at Santa Cruz. Earlier versions of parts were also presented at meetings of the American Political Science Association, Western Political Science Association, Midwest Political Science Association, Association for Political Teory, and the American Philosophical Association, as well as at conferences at the Bufalo Center for Inquiry, Freiburg University, Leiden University, Northwestern University, Penn State University, Princeton University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, the University of Oregon, the University of Wales at Newport, and

the University of Warsaw. Te interlocutors I encountered strengthened this work immensely.

A good deal of chapter 1 was previously published as “In Defense of Blinders: On Kant, Political Hope, and the Need for Practical Belief,” Political Teory 40:4 (May 2012), 497–523. Smaller parts of other chapters have previously appeared in my articles “John Dewey’s Pragmatism from an Anthropological Point of View,” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 48:1 (Winter 2012), 1–30; “Another Side of William James: Radical Appropriations of a ‘Liberal’ Philosopher,” William James Studies 8 (2012), 34–64; “Lef Hegelian Variations: on the Matter of Revolution in Marx, Bloch, and Althusser,” Praktyka Teoretyczna 35:1 (April 2020), 51–74; and “Reading Wendy Brown in Ludwigshafen: Nonsynchronicity and the Exhaustion of Progress,” in Power, Neoliberalism, and the Reinvention of Politics, ed. Amy Allen and Eduardo Mendieta (Penn State, 2022). I thank the editors for permission to reprint parts of those essays.

Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to Susanna Loewy, who read manuscript draf upon draf, sufered through endless queries about phrasing, always had a wise suggestion just as I was about to hit send, and has been an unceasingly supportive and loving partner for years. Hope springs eternal; this book is dedicated to our sons Asher Sphere and Eden Hersch.

Introduction

In 1916, the American philosopher John Dewey confessed to having held a “childish and irresponsible” faith in historical progress. His generation, he writes, confused rapidity of change with advance, and we took certain gains in our own comfort and ease as signs that cosmic forces were working inevitably to improve the whole state of human afairs. Having reaped where we had not sown, our undisciplined imaginations installed in the heart of history forces which were to carry on progress whether or no, and whose advantages we were progressively to enjoy.1

Refecting on the political upheavals of Progressive era America and the avoidable Great War in Europe, he allows that nowadays “never was pessimism easier . . . Tere is indeed every cause for discouragement.”2 Tis belated realization of inhabiting a fool’s paradise of automatic and uninterrupted historical progress need not lead to despair, however. Te rapid social transformations Dewey had taken for progress were real, afer all; changing conditions meant that the conditions for change were at hand. We may maintain hope if we choose to understand the idea of progress “as a responsibility and not as an endowment,”3 as a living ideal, an invitation to act, rather than a resignation to drif. For Dewey, as we shall see, this responsibility to the future is inseparable from the ideal of democracy, a utopian vision of an equitable, open, and decent world in which our political hopes are buttressed not by God, Progress, History, or any other laundered remnant of Geist, but by intelligent and ofen radical experimentation with the institutions and practices of social power.

Following Dewey, this study is written in a pragmatic spirit to give an account of hope as a principle of political action distinct from the facile expectation of optimism and independent of grand notions of progress, for today we fnd ourselves in a similar predicament. Tirty years ago, watching the political disintegration of the Eastern Bloc, Francis Fukuyama famously

The Principle of Political Hope. Loren Goldman, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2023.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197675823.003.0001

heralded the “end of history,” a culmination marked by the universal acceptance of liberal democracy and the exhaustion of all other possibilities.4 Controversial in its own moment, Fukuyama’s claim has aged poorly. While politicians are still wont to invoke the “right side” of history, while hope has been a particular mainstay of American public rhetoric,5 and while there remain occasional cheerleaders for the actuality of Enlightenment progress,6 the present moment is one of palpable crisis. Te recent success of right-wing populists in the United States and across the globe has spelled a retreat from democratic norms and a reversal of gains made toward more open, equitable, and pluralistic societies; at the same time, the continued consolidation of oligarchic and plutocratic rule threatens to turn incomplete democracies into complete Potemkin republics. Te failure of nation-states to adequately address the still raging COVID-19 pandemic as well as movements for economic, racial, and sexual justice, not to mention the ongoing climate catastrophe, raise doubts about the very possibility of efective, let alone transformative, political action.

My primary interlocutors are the German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), the German critical theorist Ernst Bloch (1885–1977), and three canonical fgures of American pragmatism, Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914), William James (1842–1910), and John Dewey (1859–1952). For these thinkers, hope is not an idle, passive afair, akin to the Pollyannish optimism that the world will improve; rather, hope provides a foundation and impetus for social action in the shadow of uncertainty. Kant plays a leading role not only because the subsequent thinkers all wrestle with the consequences of his turning of philosophy inward, away from the objective world and toward the subject’s experience, but also because he makes hope an indispensable aspect of moral and political agency. While rejecting Kant’s metaphysical dualism and his specifc understanding of history, Bloch, Peirce, James, and Dewey recast and refne Kant’s basic insights. Bloch, an exuberant critical theorist whose work revolves around hope, centers his sights on the world’s latent utopian tendencies; Peirce historicizes and (metaphorically) democratizes the creation of knowledge, tethering inquiry to hope; James exhorts the creation of new realities through hopeful action; Dewey, fnally, asserts and exemplifes democratic hope, an experiment in the practical belief that individuals have the capacity to collectively govern themselves.

In presenting political hope as an orientation for action, these thinkers recast the fraught idea of progress, which we now understandably approach with justifed caution, conjuring up as it does specters of epistemological

presumption, triumphant developmentalism, and paternalistic domination.7 Despite its purveyors’ claims to universality, moreover, the idea of infnite historical progress is largely an invention of the European Enlightenment. While there is more diversity of thought among its proponents than current critics ofen allow, there is also no shortage of thinkers in this period who wax enthusiastic over the coming perfection of humanity.8 It is therefore the product of a cultural feld seeded with Christianity’s eschatological time, primed for a messianic rupture with the past, and confronted with unprecedented transformations in material, political, and economic power. In political thought, the idea of progress was double-edged: on the one hand, it provided a scientifc cudgel against traditional religious and absolutist authority; on the other, it ofered a discursive justifcation for paternalism, discrimination, imperialism, and repression, not to mention the everyday cruelties of snobbery and elitism.9 Indeed, Anibal Quijano, Enrique Dussel, and others have argued that the infnite temporality of the Enlightenment myth of progress is inseparable from the colonial imaginary of empty space, a tempus nullius arising out of the false presumption of terra nullius, thereby implicating the linear and unidirectional idea of progress in the hierarchical spatial and racial classifcation of the world’s population.10 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Fukuyama’s inspiration, describes history as the gradual development of metaphysical spirit as freedom in reality, a process that transpires from East to West, reaching its culmination in modern, Christian Europe, “the absolute end of Universal History”; Africa, indigenous America, and the Orient are relegated to an eternal now of prehistory, whose inhabitants can only acquire freedom if civilization is imposed upon them.11 John Stuart Mill, who worked as a British East India Company ofcial for twenty-fve years, from 1823 (aged seventeen) until its dissolution in 1858, is equally emphatic about progress, denying liberal rights to members of “backward states of society” and notoriously describing despotism as “a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided the end be their improvement.”12 In short, a linear, unidirectional notion of history, an understanding of the future as a rupture with the past, new technological abilities and productive capacities, philosophical rationalism, and a cosmopolitan perspective enabled by Europe’s global political domination all conspired to create a particular image of progress that should be jettisoned. Within academic political thought, the pendulum of expectation has swung in the opposite direction, with recent scholars highlighting pessimistic responses to progress and the meliorability of the human condition.13

As Joshua Dienstag explains, pessimism does not necessarily deny the linearity of time, but the presumption of an upward trajectory: “Change occurs, human nature and society may be profoundly altered over time, just not permanently for the better.”14 Dienstag’s rich study of the topic draws on JeanJacques Rousseau, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Miguel de Unamuno, among others, who deny the premise shared by liberalism, socialism, and pragmatism alike, “that the application of reason to human social and political conditions will ultimately result in the melioration of these conditions.”15 Using a similar cast of characters along with Max Weber, Carl Schmitt, Martin Heidegger, and Hannah Arendt, Tracy Strong writes approvingly of what he calls “politics without vision,” linking the acknowledgment of human limitation and fragility to relinquishing hope of creating a better world.16 In an invaluable study of despair in Hegel, Søren Kierkegaard, Teodor Adorno, Frantz Fanon, and Georges Bataille, Robyn Marasco explores what happens when we assume that “there is no end to or exit from the conditions of existence, and no rational hope that a brighter future will repay patient struggle in the present.”17 Following in Michel Foucault’s wake, Wendy Brown writes trenchantly of the “ubiquitous, if unavowed, exhaustion and despair in Western civilization,” in which “most have ceased to believe in the human capacity to craf and sustain a world that is humane, free, sustainable, and above all, modestly under human control.”18 No room remains for those who seek “collaborative and contestatory human decision making, control over the conditions of existence, planning for the future . . . deliberate constructions of existence through democratic discussion, law policy . . . [and] the human knowledge, deliberation, judgment, and action classically associated with homo politicus.”19 Brown closes her Undoing the Demos with a gesture toward a hope rooted in the prospect of three distinct types of “work”: combatting neoliberalist ideology, ofering an alternative to capitalist globalization, and countering this civilizational despair.20 More recently, Brown states in an interview (cited earlier as an epigraph) that “we need grit, responsibility, and determination instead of hope.”21

Pessimism and despair are an understandable reactions to the complicities, rationalizations, and apathies of the blithe optimism in much modern Western thought. To have downcast eyes is not to be blind, however, and we should not confate the loss of traditional banisters for thinking with the loss of vision altogether. As Marasco writes, despair is a “dialectical passion . . . at odds with itself”; it is “no simple absence,” but one that “conserves

and preserves the possibility of what it also denies,”22 defned by what it fails to achieve—a point clear in its etymology, de-sperare, or down from-hope. Despair does not necessarily lead to resignation; on the contrary, it can steel against starry-eyed enthusiasm, hence Brown’s gesture of hope in the concluding pages of Undoing the Demos. Te danger, however, is that it may numb us to the live possibility of the world being other than it is; as Dienstag confesses, “although pessimism does not issue from black moods, it could indeed inspire them.”23 In 1931, Walter Benjamin described one result of this collapse of historical hopes as “lef-wing melancholy,” an attitude of radicalism “to which there is no longer in general any corresponding political action.”24

My concern in writing this book is that the loss of progress and the temptation toward historical melancholy does not rob our political imaginations of the possibility of a better future, especially insofar as the signifcance of any moment in the sweep of passing time changes as it recedes into the past. Indeed, it need not: events are always subject to reinterpretation— contemporaries hold the present in wildly diferent lights, and each scholarly generation writes new histories of previous generations.25 Moreover, as Arthur Danto argued decades ago, if there is any meaning or direction to history, it could be only be ascertained at the end—everything else, so to speak, might just be a prelude.26 Until then, we must plod along with the provisions of narratives we tell ourselves.27 More mundanely, the passing of time in everyday life recursively shapes the past’s meaning in terms of the present’s forward trajectory.28 Bloch writes of “the non-synchronicity of the synchronous” in time, the coexistence of realities from diferent moments of history whose interaction and confict generate novel possibilities and realities.29 Te rejection of grand narratives of progress does not need to foreclose the possibility of a brighter future.

Pessimism risks lending itself to what historian François Hartog terms a “presentist” understanding of history, which sees “the extension, ad infnitum, of an automatic present that is emptied of its contents and sheared from its roots and possibilities.”30 In the presentist frame, a heuristics of fear dominates: the future is seen with foreboding, ethical life is guided by an “imperative of responsibility” that upholds the status quo, and political imagination is stunted by a principle of precaution.31 Presentism and pessimism alike render the world devoid of prognostic structure.32 If history has no “visible, thinkable, or imaginable future,” historian Enzo Traverso writes, we are lef fxated on memory, with the past as present, for “a world without

utopias inevitably looks back.”33 Emancipatory aspirations are replaced by nostalgic fantasies. Pace these presentist pessimists, the thinkers in this study subscribe to a view of history in which diferent futures remain live and vital possibilities. Tey are not, however, guaranteed. Teir prospects depend on a host of factors, most of which are beyond human (let alone rational) control, but for which, as pragmatists insist, intelligent inquiry, action, and experimentation are nonetheless indispensable.

Te hope entertained in this study is thus not optimism, the standard antonym for pessimism. Tis distinction is important to emphasize because the two are ofen confused, and much of the derision aimed at hope mistakes its target for optimism. As its name implies, optimism is (strictly speaking) the conviction that this is the best of all possible worlds, a secular theodicy that translates into the historical inevitability of progress. For the optimist, the future is assured, and there is ever the temptation to take what James calls a “moral holiday,” “to let the world wag in its own way, feeling that its issues are in better hands than ours and are none of our business.”34 Hope, by contrast, is characterized by uncertainty, haunted by the possibility of failure, working to overcome despair. I use “working” intentionally, for one of the key threads of the post-Kantian line of thinking presented here is that social hope does not aford moral holidays precisely because its justifcation is inseparable from the action it underwrites.

Finally, concerning the relationship between the pessimistic outlooks of Schopenhauer, Heidegger, Fanon, and others, and the hopeful visions of the thinkers I employ, it is useful to draw an analogy to Bloch’s distinction between a “cold stream” and “warm stream” of Marxism, the frst soberly explicating society’s objective dynamics, the second orientated toward “prospect-exploration,” of breaking out of the spell of what is assumed to be possible. For Bloch, neither coldness nor warmth can or should dominate, but stand in productive tension, energizing discussion and pushing it forward.35 With much the same intent, James distinguishes “tender-minded” from “tough-minded” thinkers, the former rationalistic, idealistic, optimistic, and dogmatical, the latter empiricist, materialistic, pessimistic, and skeptical.36 My interlocutors all fall on the warm and tender-minded sides of these divides, each insisting on the generative function of ideals in human action. Having a warm temperament does not mean one ignores the cold facts of reality, but that one entertains the possibility that the world is not yet entirely baked. Te eventual future arises, however, out of the intersection of both currents. Marasco, Dienstag, Strong, Brown, and many others have

done invaluable work explicating the cold limits of politics as a response to the failure of univocal progressive history. Te present study aims to complement (and complicate) their narratives with a warm account of political hope as an active principle that disentangles it from metaphysical historical progress and psychological optimism alike, one that reckons with human fragility and fnitude while nonetheless looking toward a better future, taking the horizon as a threshold rather than a limit. Montesquieu defnes a principle as an animating passion that makes one act; following him, Arendt notes its etymological derivation from principium, or beginning.37 As a principle, hope is thus a fundamental basis for both inquiry and action, motivating our vision and inspiring our deeds.

Te Varieties of Hopeful Experience

Te historical specifcity of contemporary critics of the idea of progress notwithstanding, wariness of hope has a well-documented provenance dating to the early ancient Greeks. Indeed, it is ofen forgotten that hope frst appears in Western literature as an evil, in Hesiod’s setting of the Pandora myth in Works and Days, roughly contemporaneous with Te Odyssey. Te word elpis (ἐλπίς) does not—in pre-Christian authors, at least—necessarily convey desire, but refers instead to any orientation toward the future, good or bad (“anticipation” is perhaps better38). Later in the same poem, upbraiding his profigate brother, Hesiod voices the familiar opposition between work and hope, which is “not good at providing for a man in need.”39 Elpis also misleads in politics; the poet Pindar, in an ode celebrating a newly installed city councilor on the island of Tenedos, warns against ambitious civic projects born in thrall of “shameless hope.”40 While not all ancient Greek accounts paint elpis in a purely negative light—Heraclitus enticingly writes that “If one does not hope, one will not fnd the unhoped-for, since there is no trail leading to it and no path,”41 and the fable writer Babrius makes hope a blessing in his later setting of the Pandora myth—but there are exceedingly few rosy assessments, and its commonly associated epithets are “empty” and “blind.”42

Hope for historical progress was not yet on the docket, however. As numerous scholars have noted, ancient Greek thinkers (for the most part) held a cyclical notion of history, and the idea of a fundamental break with the past was barely entertained.43 Christianity displaced this cyclical historiography

in favor of a linear one looking toward the coming moment of messianic rupture.44 A break with the past not only becomes fathomable but central to Christianity; Paul names elpis alongside faith and love as a theological virtue, celebrating the very unworldliness that troubled pre-Christian Greeks.45 Paul expected the second coming of Christ to happen in his own lifetime,46 while subsequent generations of Christians came to accept an indefnite deferral of this messianic break. By early modernity the focus on being plucked out of worldly time gave way to providential writers like Jacques-B énigne Bossuet, who saw in empirical history exhaustive evidence of humanity’s participation in a divine Christian plan. Enlightenment ideologists of progress secularized this vision while stretching it out infnitely, asymptotically, toward a telos of the moral and scientifc perfection of humankind. Many factors fed this transformation, from the previously mentioned advances in scientifc and technological knowledge and the growth of Europe as a global hegemon, to the rationalization of time in everyday life in response to the imperatives of proto-capitalist production.47 In any event, the shaky consensus on the actuality or even desirability of historical progress was not long for the world, and critics were already calling in the nineteenth century for a rejection of progressive temporality in favor of a notional eternal now (in Schopenhauer), or a reprise of ancient cyclicality (in Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence), a position also reached by the infuential twentieth-century philosopher of history Karl Löwith,48 and which lurks to varying degrees in the writings of recent pessimists.

With such an accretion of meanings and temporalities in hope over its long history, the concept operates in numerous contexts. While Kant, Bloch, and the American pragmatists write in the shadow of Christian hope, they nonetheless push back against its monological and otherworldly foundations; like the Greeks, they emphasize its complex practical import for the present. Before discussing political hope in detail, it will be useful to give some provisional bearings in light of the contemporary intellectual landscape. Hope has been addressed from an array of perspectives, including philosophy, psychology, medicine, history, theology, anthropology, literature, aesthetics, African American studies, and journalistic reportage, each of which infects it diferently.49 It therefore has no single defnition, just as there is no single way hope is experienced or felt. As we shall see, despite discussing hope in diferent ways depending on personal temperament and specifc context, the thinkers in this study stress hope’s practical and performative qualities.

In analytic philosophy, hope has conventionally been defned in terms taken from British empiricism as “a combination of the desire for an outcome and the belief that the outcome is possible but not certain,” in the words of philosopher Adrienne Martin.50 Strictly speaking, this defnition is not future-oriented, and in everyday life there are uses of “hope” that regard past events (i.e., hoping that a visitor’s fight arrived on time or hoping that a long-lost pet found a good home). In such cases—as with future-oriented hope—the uncertainty is crucial; one can assume a bad outcome (say, in the pet case) and hope for a good one nonetheless precisely because certainty is unavailable; the hope ends once the outcome becomes known. Tis is also the case with hope for the future: one does not hope for something one knows will happen.51 I belabor the point of uncertainty—already noted earlier when discussing optimism—because of how common it is to underplay it. Jayne Waterworth observes, for example, that the Oxford English Dictionary defnes hope as “desire combined with expectation,” which conveys more confdence than the analytical defnition allows, and argues that “anticipation” is more appropriate, more directly conveying not only uncertainty but also hope’s conative aspect insofar as it derives from the Latin anticipare, “to seize or take possession of beforehand.”52 We can also distinguish between hoping, as a phenomenon concerning possibility, and wishing, concerned with impossibility; voicing a wish to sprout wings is perfectly fne, but expressing a hope to do the same is to engage in magical thinking. In this example, the line between possibility and impossibility is clear: humans cannot spontaneously sprout wings. For the thinkers in this study, the human capacity for creation means that new possibilities can emerge, but not that just any wish can come true. Finally, philosophers have introduced a number of categories to refne and apply the orthodox defnition in practice. Among the most salient for social hope are objective and agent: the frst is the anticipated future state of afairs, the second its orchestrator.53 Hope, of course, has practically limitless imaginable objectives, as it does practically limitless imaginable agents; put in analytical terms, however, political hope concerns the exercise of public power, and democratic hope concerns the exercise of public power mutually orchestrated with others.

While the orthodox defnition captures a large swath of what is understood as hope, it appears inadequate to express other important qualities associated with it. For one, it does not seem to refect the phenomenology of hoping against hope, when the outcome is extremely unlikely, nor does it capture the unique sustaining power hope ofen conveys.54 Furthermore,

hope’s afective and phenomenological textures fall by the wayside. For the Christian existentialist Gabriel Marcel, if we approach hope only from an analytical perspective, we “make it unreal and impoverish it.”55 In experience, hope involves “a fundamental relationship of consciousness to time,”56 and thus cannot be reduced to desiderative-calculative objectives. Hope keeps the future open, holding the promise that the world is not yet fnal: “piercing through time,” it allows the “weaving of experience now in process . . . in[to] an adventure now going forward.”57 As a mood of possibility, hope enables agency, becoming “a vital aspect of the very process by which an act of creation is accomplished.”58 Te philosopher and psychoanalyst Jonathan Lear describes what he calls “radical hope” similarly. What makes hope radical, Lear writes, “is that it is directed towards a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is. Radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it.”59 As such, Lear presents radical hope as an indispensable tool for sustaining ourselves as moral beings, living with others, during moments of deep cultural disruption, when traditional frameworks of meaning no longer hold. While in practice radical hope can admittedly be difcult to distinguish from resignation, capitulation, and even collaboration, the important thing is that it acts for its bearer as its own pragmatic justifcation. In other words, if I believe my radical hope is justifed, and it thereby sustains my ability to ethically persevere in a world with others, it is justifed.

Philosophical accounts ofen treat hope as a mental phenomenon of individual psychology. Scholars in other felds have rendered hope as a common afair, something anchored in the individual self, but which takes living shape only through social performance and interaction. Anthropologist Hirokazu Miyazaki, for example, understands hope as a method of collaborative knowledge formation, “an efort to preserve the prospective momentum of the present” that is “predicated on the inheritance of past hope and its performative replication in the present.”60 From feldwork among the colonially displaced Suvavou people of Fiji, Miyazaki argues that hope for the recovery of ancestral lands both produces and is reproduced through the specifc practices of Suva (Christian) religious ritual, its social power structure, and its political self-identity, refected in its repeated appeals to the Fijian government for redress since soon afer expropriation. In Miyazaki’s account, inspired in part by Bloch, the not-yet is the central category of Suva self-understanding

insofar as their political agency revolves around extrapolating an unfulflled hope in the past and replicating it as hope in the present.61 Importantly, however, because this hope is an “ontological condition” it is inseparable from action; as Miyazaki writes, “it cannot be argued for or explained; it can only be replicated.”62

In related fashion, theater scholar Jill Dolan and cultural theorist Sara Ahmed emphasize hope’s afective, performative, and political aspects in concrete practice. Echoing Bloch and his friend the playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht, Dolan describes the instantiation of hope in live performance, which

provides a place where people come together, embodied and passionate, to share experiences of meaning making and imagination that can describe or capture feeting intimations of a better world . . . Diferent kinds of performance [can] inspire moments in which audiences feel themselves allied with each other, and with a broader, more capacious sense of a public, in which social discourse articulates the possible, rather than the insurmountable obstacles to human potential.63

Te glimpses of utopia Dolan discovers in theater are rends in the fabric of the present, at once a metaphor for and the prefguration of a better future, pointing toward a radical democratic politics. Ahmed describes hope similarly, drawing special attention to its visceral and somatic qualities. In the fuller passage cited earlier as an epigraph, Ahmed writes that hope

makes involvement in direct forms of political activism enjoyable; the sense that “gathering together” is about opening up the world, claiming space through “afective bonds.”64 . . . Hope is what allows us to feel that what angers us is not inevitable, even if transformation can sometimes feel impossible. Indeed, anger without hope can lead to despair or a sense of tiredness produced by the “inevitability” of the repetition of that which one is against . . . hope involves a relationship to the present, and to the present as afected by its imperfect translation of the past. It is in the present that the bodies of subjects shudder with an expectation of what is otherwise; it is in the unfolding of the past in the present. Te moment of hope is when the “not yet” impresses upon us in the present, such that we must act, politically, to make it our future.65

For Ahmed, Dolan, and Miyazaki, hope is both a precondition and result of public performance and collaborative activity. Its desiderative and rational qualities are nested within multiple shifing layers of afect, temporalities, political imaginaries, and collective experience.

Although speaking a diferent conceptual language, Kant, Bloch, and the pragmatists likewise emphasize hope’s creative, generative, and performative qualities leading toward moral personality, concrete utopia, or a genuinely democratic public. Te stage is set by Kant’s description of hope as an orientation underpinning “practical belief” in historical progress. A belief is practical if it is entertained not because of compelling theoretical proof but because it is essential for normativity: while we have no incontrovertible evidence that the will is free, for example, Kant holds we may nonetheless act as if it is for the sake of moral experience. Te same goes for teleological progress in history, albeit, as we shall see, in a typically idiosyncratic manner. Bloch, Peirce, James, and Dewey follow Kant in presenting hope not as rationally justifable on the merits of its content as such, but as an indispensable condition for sustained practical moral and political commitment. Te title of Bloch’s magnum opus is, afer all, Te Principle of Hope.

For these thinkers, moreover, hope does not presume an escape from the conditions of human fnitude, a point ofen obscured by its close association with religion. Bloch speaks of “transcending without any heavenly transcendence,”66 of stepping beyond the bounds of what is now understood to be possible in the world. Tis aspiration refects not a pernicious utopianism but a simple observation about historical change: things once considered impossible do in fact become possible. In politics or any other enterprise that relies on human action and coordination, the adage that “that’s just the way things are” is invariably false. Put otherwise, although political hope does not deny human fnitude, it nonetheless maintains faith in the possibility of miracles in Arendt’s idiosyncratic sense of events that “burst into the context of predictable processes as something unexpected, unpredictable, and ultimately causally inexplicable.”67 For Arendt, human beings are the “miracle worker[s]” of history, for “whether or not they know it, as long as they can act, [they] are capable of achieving, and constantly do achieve, the improbable and unpredictable.”68

In this regard, it is important to acknowledge the prophetic voice heard in this study’s subjects, for its peculiarly Kantian cast anticipates Arendt’s remarks on the miraculous quality of human action in concert. Tat Bloch and the pragmatists engage in prophecy is perhaps to be expected; Bloch’s

initial renown came from his messianic Te Spirit of Utopia (1918), and a number of scholars have documented the powerful and enduring resonance of prophetic rhetoric in American thought.69 For reasons that will become clear in exposition, I hear in these thinkers not an appeal to divine errand but an echo of Kant’s discussion of a prophetic (wahrsagende) history of the future. In Te Confict of the Faculties (1798), he writes that such a mode of inquiry is plausible “if [and only if] the prophet himself brings about and prepares the events that he announces in advance.”70 It is permissible to prophesy, that is, if one also plays a role in the prophecy’s realization. As a call to one’s self and others to act toward an animating ideal, prophecy is intimately bound up with performance. Such a pragmatic, prophetic sensibility is present in all of the authors in this study, manifesting itself in both form and content. James’s renowned essays on moral life, for example, were originally public addresses, and their striking mix of frst-person memoir and second-person exhortation unmistakably enacts his substantive theme of the vitality of philosophical refection; similarly, I argue that Kant’s celebrated essay on perpetual peace—written in the form of a treaty between nations— is itself meant prophetically as an exemplary contribution to the legal foundation of a future pacifst world order.

Perspective and Scholarly Aims

Tis book’s main purpose is to sketch an account of hope that is rooted in political action and democratic experimentation, one that stands independently of the thinkers that guide this study. Te question naturally arises why I cast Kant, Bloch, Peirce, James, and Dewey rather than anyone else whose thought speaks to hope—Augustine, Aquinas, Marcel, Adorno, Arendt, James Baldwin, or Richard Rorty, for example—as my dramatis personae. For one, I cannot escape the fact that due to the contingent circumstances of life, temperament, and academic training, my professional gaze tends to focus on American pragmatists and other inheritors of German idealism.71 Furthermore, excellent recent studies of other signifcant thinkers of hope already exist that are more sensible and insightful than anything I could contribute.72 Tat said, Kant is hardly an arbitrary choice: he exerted (and continues to exert) an outsized infuence on subsequent philosophy, and “What may I hope?” is one of the three questions that explicitly guide his work. Kant’s refections set the stage for the compelling eforts of Bloch, Peirce,

James, and Dewey, who take Kant’s sketch of hope as a working principle to heart but reject his metaphysical dualism, the hard line he draws between subject and object. Each post-Kantian thinker accordingly articulates a distinctive dynamic one-world metaphysics for an ontology of the not-yet, and which gives criteria for distinguishing false hopes from those with traction.

To spell out two further, related convictions shared by Bloch and the pragmatists, the frst is that the world can change; as Brecht wrote, “the contemporary world is describable to contemporary humans only if it is described as a transformable world.”73 Tis transformation of the world goes not simply for the possibility that new possibilities arise in reality, as it were, but also conceptually, that we may ofer new descriptions and vocabularies by which we render our world intelligible, a possibility of special concern to Bloch and Dewey. A second shared conviction, hinted at earlier, is that reality is in process rather than static. With process metaphysics comes the assumption of ontological continuity between subject and object as well as between agency and structure: neither human nature nor the nature of the world is fxed and fnal. Human action—or better yet, following Dewey, “trans-action” with and within an environment74 may bring novel possibilities and hence new realities into being. Tis point deserves emphasis. As James writes, certain practical beliefs can “create [their] own verifcation.” Tis is particularly the case for social and political action: “Wherever a desired result is achieved by the co-operation of many independent persons, its existence as a fact is a pure consequence of the pre-cursive faith.”75 A train robbery will be foiled only if individuals are willing to believe that others will join them in overpowering the villains; to invoke Arendt again, miracles born of human cooperation—like political and social democracy—become possible only because of the willingness to entertain their possibility and accordingly enact them.

Reading these thinkers in the light of anticipation, I defend them all from accusations of optimism and challenge a number of conventional interpretations of each in the process. Te contours of the critical system allow us to see that Kant is not a simple Enlightenment optimist, but a philosopher of action well aware of the tensions between theoretical and practical reason, not to mention the contingency of history. Bloch is not an abstract utopian aesthete, but a philosophical polyglot who predicates concrete hope on an idiosyncratic vital materialism that grounds his ontology of the notyet. Te case is the same with each of the pragmatists in this study: against recent appropriators of Peirce for democratic theory, I show that his

community of inquiry stands against the background of a strongly metaphysical providentialism, not to mention that he explicitly denied the applicability of scientifc epistemology to political matters; James I read as a more slippery and ambiguous political thinker than recent enthusiasts fnd him, largely on account of his psychological and methodological individualism; and Dewey is not the mild pluralist of many recent readers’ imaginations, but a radical internal critic of both liberal democracy and market capitalism. Furthermore, the divergent approaches of Peirce, James, and Dewey put paid to monolithic understandings of pragmatism, just as drawing together this particular cast of characters highlights the legacy of German idealism for both Marxism and pragmatism, the latter of which is too ofen portrayed as a uniquely American invention.

Kant and pragmatism are by now more or less known quantities in political theory. Bloch, by contrast, remains largely neglected, overlooked in the shadows of more luminous Frankfurt School afliates like Adorno and Benjamin. A further aim is therefore to give Bloch his proper due by bringing his fecund work into view for scholars of political thought.76 Insofar as my interpretation of Bloch leans heavily on his (mostly untranslated) writings on the concept of matter, however, it presents a more complete picture of his “open system” than one ofen fnds in readings that approach him mainly as an aesthetic philosopher of utopia.77 To recover Bloch is to recover utopia; thus a fnal aim of this study is to insist that the hope to make the impossible possible is a vital force in political life and political theory.78 Emphasizing the anticipatory aspect of political thought allows us to make sense of political acts as prefgurative instead of merely expressive; participation in voting, electoral politics, protest, aesthetic happenings, and even everyday minor acts of illegality like jaywalking (“anarchist calisthenics,” in James C. Scott’s delightful phrase79), are not merely activities serving instrumental endsin-view but feeting enactments of and preparation for a brighter future.80 Rather than stressing the past and present tenses of the history of political thought, I stress the present progressive and the future.

Plan of the Work

Te motion of this study is propelled by the tension between what might be called “psychological” and “metaphysical” approaches to hope. Te psychological approach, on the one hand, locates the basis for hope in the cognitive

and practical needs of an individual subject. Te metaphysical approach, on the other hand, vests hope in the dynamic processes of the material world, supernatural providence, or some other teleological explanation. Tis distinction efectively amounts to the question of whether hope is a subjective or objective matter. Psychological hope is immune to empirical disappointment, whereas individual psychology is irrelevant to a metaphysically vested hope. In practice, both may be indistinguishable from idiocy or fanaticism. Each of my thinkers, with varying success, negotiates between these heuristic poles and gestures in his own fashion, I argue, toward a pragmatic understanding of hope, in which action translates subjective aspiration into objective possibility. Furthermore, I argue that despite the extraordinary richness and surprises contained in the work of these thinkers, each save for Dewey ultimately tacks toward one or the other ideal type. To preview, Kant and James lean psychological, while Peirce and Bloch lean metaphysical; I argue that Dewey’s understanding of democratic hope as intelligent public practice manages, by contrast, to efectively attend to both poles without falling into the potentially solipsistic rhapsodies of the former or the potentially deterministic apathies of the latter.

Te frst chapter describes Kant’s approach to political hope through a wide-ranging engagement with his work, including his writings on moral theory, anthropology, religion, history, and politics, as well as his three foundational Critiques. I frst explain how Kant turns the lens of philosophy inward, toward human cognition and away from the objective world; rather than asking about the nature of reality, that is, he asks what must be necessary for reality to take the form it does in our experience, as fnite rational beings located in space and time, with moral commitments and practical interests. I then explicate Kant’s notion of “practical belief,” a belief indispensable for normative agency, as the key to grasping his understanding of hope. Kant argues that we cannot know there is progress in history, that is, and its many catastrophes speak against this claim, but we may nonetheless hope for progress insofar as denying its possibility robs humans of the motivation to strive for a better future. I then discuss in detail Kant’s various briefs in favor of the “regulative” idea of progress, including his famous essays on perpetual peace and the idea of universal history as well as lesser-read works like Te Confict of the Faculties, in which Kant rejects Moses Mendelssohn’s view that history neither progresses nor declines—a perspective he calls “abderitism” for rare comic reasons—his writings on religion and anthropology, and his comments of historical teleology in Critique of the Power of Judgment.

Crucial to Kant’s view, I show, is that hope is predicated on action toward one’s end, just as historical prophecy is only permissible if one has a hand in its realization. A fnal section is dedicated to some shortcomings of Kant’s account, chief among which is the ontological dualism the other thinkers in this study reject.

Te second chapter concerns Bloch, the philosopher of utopia. Bloch is ofen thought of as an aesthete, mystic, or even messianic fgure; I stress, however, that his social, religious, and cultural writings operate against an idiosyncratic ontology of matter resting on the generative fecundity of nature. Where Kant ultimately separates hope from empirical events, Bloch puts the world front and center, attuning hope to the utopian possibilities gestating within it. For the sake of clarity in explicating this very challenging thinker, my exposition proceeds in stages through the distinct strands of Kant, Hegel, and Karl Marx that he weaves together, along with his self-described neoAristotelian or Avicennan vital ontology of matter. I argue that this ontology is a linchpin of Bloch’s entire project, for it provides the material basis for the necessary assumption that novel possibilities can arise in reality: even if some utopias are impossible according to what is today taken to be possible, that is, Bloch’s Avicennan understanding of matter lays stress what may become possible. Utopian anticipation relies on the latter “layer of possibility.” I defend Bloch against the common charge that he hereby reintroduces “Nature” as a metaphysical subject, for Bloch is clear that such new possibilities arise out of human action, out of experimentation with the institutions and categories of social life. At the same time, I argue that Bloch’s account does not escape several other problems concerning the relationship of this performative experimentalism to his inevitabilist rhetorical inclinations.

Te second part of the book turn to American pragmatism. Chapter 3 takes up Peirce and James, who lean toward metaphysical and psychological accounts of hope, respectively. Peirce is a key thinker for understanding James and Dewey, both of whom were deeply infuenced by his work: the insistence on the primacy of practice, the idiosyncratic terminology of habit and inquiry, the defnition of belief as a habituation to act, the assumption of the ontological continuity of mind and matter, and even the name “pragmatism,” all rooted in his writings. His infuence in the epistemological defense of democracy is furthermore signifcant, for Peirce’s model of truth as the result of the agreement of a scientifc community was appropriated by James and Dewey, not to mention numerous other more recent political theorists, as a model for the intersubjective and democratic creation of