SPYING ON THE R EICH

THE COLD WA R AGAINST HITLE R

R . T. HOWA R D

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © R. T. Howard 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2023

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022940113

ISBN 978–0–19–286299–0

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Abbreviations

AN Archives Nationales, Paris

A/S Au sujet de (‘About’)

CCCA Churchill College Cambridge Archive

DBFP Documents on British Foreign Policy

DDF Documents diplomatiques français

DRC Defence Requirements Committee

EHR English Historical Review

HJ Historical Journal

IMCC Inter-Allied Military Commission of Control

INS Intelligence and National Security

IWM Imperial War Museum, London

ODNB Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

PCO Passport Control Office(r)

PRO Public Record Office

SHD Le Service Historique de la Défense, Paris

SIS Secret Intelligence Service

SR Service de Renseignements

TNA The National Archives, Kew

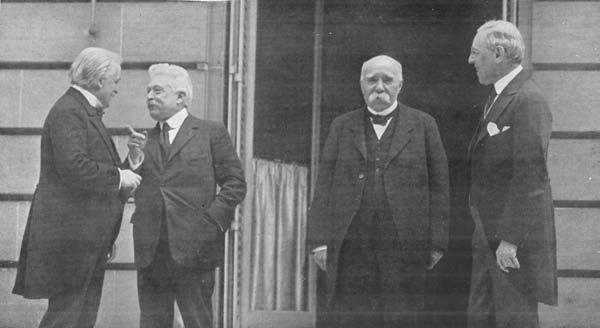

List of plates

Plate 1: The Treaty of Versailles (1919) was formulated at the Paris Peace Conference after World War 1. Pictured here, at the conference, are (from left) David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson.

Alamy: D95YEC

Plate 2: Hitler in Munich in the 1920s.

Alamy: 2BH9G1W

Plate 3: Key units of the German navy assemble at Kiel in 1934.

Alamy: P66WCM

Plate 4: Göring with Charles A. Lindbergh and his wife. Library of Congress: 2002712457

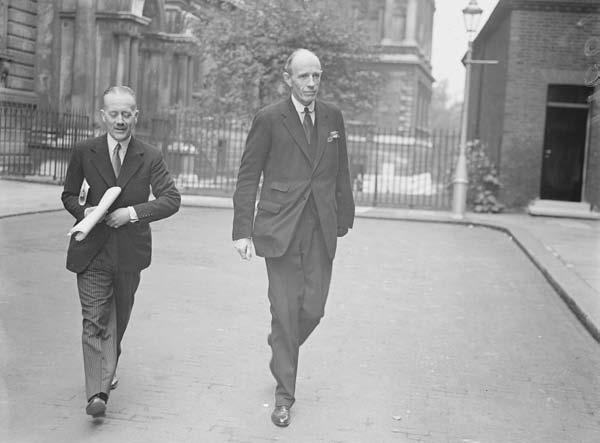

Plate 5: Great Britain’s top diplomats – The 1st Earl of Halifax, on the right, with Sir Alexander Cadogan.

Alamy: 2BW24HB

Plate 6: Sir Stewart Menzies, later head of the SIS, pictured here in the 1920s. Getty: 3140523

Plate 7: Sir Robert Vansittart, a senior British diplomat before and during the Second World War, and a strong critic of the appeasement of Nazi Germany.

Alamy: 2BW8DMN

Plate 8: A Luftwaffe display at the Nuremberg Rally in 1938. The Nazis used these displays to intimidate their opponents, and project an exaggerated image of their military strength.

Alamy: E8PHTE

‘I have an instinctive mistrust of diplomats who want to convey the impression of being well informed, of rumours that are manipulated by private agendas, and of fake news spun out by Goebbels’ press service a piece of information, from a trustworthy source and with value, can be distorted by the time foreign embassies get hold of it and put it onto a secret telegram.’

Paul Stehlin, French Air Attaché Berlin (1936–9)

‘Many intelligence reports in war are contradictory; even more are false, and most are uncertain . . . In short, most intelligence is false.’

Carl von Clausewitz, On War

Map 1. Europe in 1920, after the territorial changes imposed by the Treaty of Versailles

Plate 1. The Treaty of Versailles (1919) was formulated at the Paris Peace Conference after World War 1. Pictured here, at the conference, are (from left) David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson.

Alamy: D95YEC

Plate 2. Hitler in Munich in the 1920s.

Alamy: 2BH9G1W

Plate 3. Key units of the German navy assemble at Kiel in 1934.

Alamy: P66WCM

Library of Congress: 2002712457

Plate 4. Göring with Charles A. Lindbergh and his wife.

Plate 5. Great Britain’s top diplomats – The 1st Earl of Halifax, on the right, with Sir Alexander Cadogan.

Alamy: 2BW24HB

Plate 6. Sir Stewart Menzies, later head of the SIS, pictured here in the 1920s. Getty: 3140523

Plate 7. Sir Robert Vansittart, a senior British diplomat before and during the Second World War, and a strong critic of the appeasement of Nazi Germany. Alamy: 2BW8DMN

Plate 8. A Luftwaffe display at the Nuremberg Rally in 1938. The Nazis used these displays to intimidate their opponents, and project an exaggerated image of their military strength.

Alamy: E8PHTE

Introduction

Early in the afternoon of 1 February 1939, a middle-aged man called Walther Friedrich Marath arrived at the Hebron Hotel in central Copenhagen. He showed the receptionist his passport to prove who he was and then made his way, suitcase in hand, to his comfortable, although simple and sparse, single room on the top floor. To the hotel staff, there was nothing about this guest that seemed unusual, other than the fact that he had a noticeably strong German accent. Such visitors were always coming and going.1

His real name was Felix Waldemar Pötzsch and he was in fact a highly valued British Intelligence agent who was tasked with obtaining vital information about what was happening inside Hitler’s Reich. His spy handler—an Englishman he knew only as ‘Karl’—had provided him with a forged passport that had allowed him to reach Danish shores and get through customs unchallenged. And it was Karl’s substantial cash payment that would pay his expenses over the months ahead.

In return, Karl wanted information about Hitler’s Reich. And alone in his room, Pötzsch looked out to the harbour, a few hundred yards before him, and across to the sea beyond, and began to draw up plans to obtain it.

This was not the first time that the mysterious Englishman had helped him. Over the preceding year, Karl had enabled him to evade the clutches of the Belgian and Dutch governments: both of these neutral countries had come under strong German pressure to crack down

1. This account is based on the proceedings of the Copenhagen City Court. See Københavns Byret. 10. A Afd. Særlige Straffesager. A-1 1939–1967. Retsbog 1939 1 2–1949 12 30.

on the British and French spy rings that operated from this foreign soil against Germany. And in Holland, where the Nazi secret services had infiltrated British Intelligence operations with stunning success, the Gestapo had also been hot on his heels until Karl had once again helped him keep one step ahead and slip unnoticed into Denmark.

There was one simple reason why the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) was prepared to go to such lengths, and to some expense, to help Pötzsch. The British government was desperately short of accurate, up-to-date information about the state of the German armed forces, and it was on this vital matter that this well-networked individual had something to offer.

Born in Bad Schmiedeberg near Wittenberg in Saxony, Pötzsch had joined the German navy in 1911, when he was just 18, and served on the cruiser Emden as a seaman. It was not long before he saw action, for within just months his ship had been ordered to suppress an uprising of native people in the Pacific Islands against German rule, a brief and bloody episode that was by all accounts marred by brutality on the part of the overlords. Later, in the First World War, he took part in pitched sea battles and skirmishes against the Royal Navy in the North Sea.

But Pötzsch had always had another interest besides seamanship. He had joined the left-wing Social Democratic Party when he was a teenager and subsequently became closely involved in its activities, and those of some international Marxist groups, in and around the port of Bremen. Before long, he had been appointed as one of the party’s local representatives, and by the early 1920s was helping to organize strikes, protests, and demonstrations, as well as fighting street battles, against a variety of political opponents, including Adolf Hitler’s fast-growing National Socialist Party.

Hitler’s accession to power, in early 1933, put the fear of God into Pötzsch, who soon fled his homeland, narrowly escaping arrest by crossing firstly into Holland and then, shortly afterwards, to Belgium. But he had no intention of giving up the fight against his political opponents. He immediately made contact with his fellow exiles, who were equally determined to rally domestic opposition to Hitler and to help other political exiles find places to live and work. And he kept in regular touch with his contacts in the German underground back home, sending them anti-Nazi leaflets and pamphlets that they could quietly distribute. But in early 1937 he fell out with his fellow exiles and was expelled from their governing committee.

It was at this point that Pötzsch had become acquainted with a British official called Edward Kayser, who was based at the British Passport Control Office (PCO) in Brussels. In Belgium, as elsewhere, the PCO provided a cover for British Intelligence operations, and in this role Kayser was responsible for recruiting and running agents. Foreign intelligence services generally considered exiles to be a suspect source of information but Kayser was willing to take a chance. He introduced himself as ‘Karl’—Pötzsch never discovered his real name— and the two men soon struck up a good rapport.2

The German exile now became a full-time paid British agent, lured by a tempting amount of money and wanting to do something to undermine Hitler’s regime. He had numerous contacts amongst his friends, family, and comrades back in Germany who were in a position to tell him what he, and Karl, wanted to find out. He would write to them, using a series of post office boxes to make contact and employing a similarly discreet method to pick up the anonymous and carefully worded letters they sent back. Soon he had cast light on some of the Reich’s military secrets, including a number of technical developments the Germans had implemented, notably to the armour plate used by their new battleships.

But Karl’s most pressing priority was to obtain accurate and up-todate information on the state of the German navy, which the SIS had been instructed to ‘make every endeavour’ to find out more about. Nearly two years before, in the summer of 1937, he had instructed Pötzsch to visit Denmark to investigate reports that the Germans were building ports and harbours on the island of Sylt in the North Sea, a capability that would have serious repercussions for the Royal Navy and for British security. Rumours had also long been flying about topsecret aviation experiments that the Nazis were supposedly carrying out in the area [see below Chapter 2]. But if Hitler’s ships were dangerously below the radar, Denmark was a good place to find out more because, as the head of the SIS argued, it was ‘by its geographical

2. Exiles—‘alarmist statements seem to be always prevalent among refugees and/or prominent anti-Nazis’: see ‘Most Secret Memorandum’, 9 Mar 1939, FO 1093/86 TNA. ‘Too much attention should not be paid to the views of emigrés whose connections (in the Reich) are solely with the opposition’—Memo from British consul in Vienna to Kirkpatrick, 19 May 1939, FO 371/23008 TNA.

position . . . very favourably situated’ for intelligence-gathering on Germany.3

Now Karl had asked him to find out more about the specifications and capabilities of the German navy, and to do so, on this second trip, Pötzsch planned to ingratiate himself with some of the German sailors who frequented the Danish ports. He would pose as a salesman, peddling hair tonic, to introduce himself and then buy them drinks and get them talking. Soon he had acquired detailed information about the movements of German vessels and knew exactly when they were due to arrive and depart so that he could appear at just the right moment. At the same time, he wrote cryptic, coded messages to his Bremen contacts and asked them for the information he needed.4

Felix Pötzsch was just one of many foot soldiers of a Cold War against the Third Reich in the years that preceded the Second World War, as their respective governments sought détente with Hitler—‘a settlement in Europe and a sense of stability’—brokered by a policy of appeasement. This Cold War then continued from March 1939, when policymakers surrendered appeasement and instead made threats of war, until the German invasion of Poland on 1 September, when those threats were realized.5

This Cold War was not a campaign of covert destabilization, comparable to the efforts that the American government, for example, waged against the Cuban regime of Fidel Castro in the years that followed the revolution in Havana in 1959. It was instead an effort of intelligence-gathering, as a number of foreign governments scrambled to gauge the threat posed by a regime in Berlin that became increasingly belligerent and hostile but remained highly opaque and unpredictable.

This effort involved gathering accurate information about not just the Nazi regime’s resources and capabilities but also about the mindset

3. ‘Make every endeavour’—Keith Jeffery MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909–1949 Bloomsbury (2011) 279. Sylt—British concern about Sylt becomes clear in WO 190/460 and 474 TNA, and from a parliamentary question in April 1938; https:// api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1938/apr/13/island-of-sylt-naval-airbase>. Denmark—Jeffery 279.

4. Karl’s instructions—Sagsnummer 68.418, Danish National Archives, Copenhagen. Pötzsch was arrested in Apr 1939 and in June sentenced to six months in prison for spying. The German government suspected him of complicity in a series of bombings on German vessels and made numerous attempts to extradite him.

5. Settlement in Europe—Neville Chamberlain, 31 Oct 1938, CAB 23/96 TNA.

and ambitions of its leaders and the attitudes of ordinary people, upon whom even the most tyrannical regime is to some degree ultimately dependent. And although there were moments of relative cooperation between Berlin and some of its neighbouring governments, notably during the ‘honeymoon period’ of the mid-1930s, when the Nazi authorities granted foreign access to some previously restricted installations and factories, this effort of espionage was always undertaken in an atmosphere of mutual suspicion and mistrust, and always at great personal risk to those who stood at its frontline.

The challenge of monitoring and assessing Nazi Germany was one that confronted the whole of Europe, which watched and listened to Hitler and his henchmen with growing alarm and which worked hard to find out more about what was really happening within the borders of the Reich. Even neutral states, such as Switzerland, Sweden, Holland, and Belgium, could not afford to look away from a country that had committed sacrilege against Belgium’s neutrality in 1914, when the German army had used its territory as a convenient gateway into France. European leaders were also well aware that the outbreak of another catastrophic conflict would create waves of refugees who would flood across their borders.

Nor could more distant countries afford to look away. Despite its strictly isolationist approach in the 1930s, the United States government was deeply conscious of the seismic economic damage that another world war would inflict, particularly at a time of global depression, as well as of the strategic realignment that would then eventuate, especially at an hour when Washington might need comrades-in-arms against a communist, ‘Bolshevik’, order that had seized power in Russia in 1917. As the secretary of state, Henry L Stimson, argued in 1935, ‘a great war anywhere in the world today will seriously affect all the nations, whether they go into that war or not’.6

But while spying on the Reich was always an international effort, there were of course some countries that stood closer to the frontline of the Cold War than others.

At the very forefront were Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Romania. Hitler had openly described his ambitions to seize control over stretches of foreign territory where ethnic Germans lived, and he also

6. Stimson—radio broadcast, Oct 1935: transcript in the files of the British Embassy, Washington, FO 115/3408 TNA.

had every reason to cast a rapacious eye upon the raw materials and infrastructure that these other countries could boast but which the German economy, particularly its war machine, painfully lacked. Germany should start its ‘racial fight’, as the dictator once said, against those states which hosted ‘oilfields, rubber, treasures of the earth’. Romania’s massive oil reserves represented a glittering prize, while Czechoslovakia’s giant Skoda munitions plant at Pilsen was also firmly in Hitler’s sights. He had outlined his plans in his 1925 autobiographical manifesto, Mein Kampf, as well as in his unpublished but revealing Second Book, written in 1928.7

But the two countries that mattered most in the Cold War against Hitler were Britain and France. This was not because they had more reason than any other to feel a sense of threat. On the contrary, the Führer consistently reiterated his peaceful intentions towards both countries, prompting some politicians of the time and historians of the present day to even question whether their involvement in the Second World War was ever necessary. Instead, Britain and France matter most in the story of foreign espionage against Germany because of their military and economic might.8

Stricken though both were by economic hardship, and still traumatized by the experience of the First World War, only these two countries had the resources to take effective action against Germany. This was not necessarily military action, although the French possessed a mighty landed army and the British a formidable navy: both could instead also have mounted an economic embargo, sanctioned by the League of Nations (the forerunner of the United Nations), that could conceivably have starved both the people and the economy of Germany. The Soviet Union was the only other European (or semiEuropean) country that could have posed a similar such threat to the Reich in the 1930s, but it was at this time too embroiled in its own internecine struggles, waged by a leader too focused on finding and executing his domestic enemies, real and imaginary, to mount an effective challenge. Josef Stalin was bleeding his own country red. His critics in any case argued that the Soviet military was like a bear

7. ‘Racial fight’—Piers Brendon The Dark Valley Jonathan Cape (2000) 467. Hitler’s Second Book was written in 1928 but was unpublished until 1961. The text was discovered in May 1945.

8. British involvement in WW2, or at least the timing of it, has been questioned by, for example, Peter Hitchens in The Phoney Victory:The World War II Illusion IB Tauris (2018).

defending its home territory, capable of fending off an invader but not of launching an offensive beyond its borders.9

It was the relative might of the two cross-Channel neighbours that makes the relationship between their governments, and their spy services in particular, so integral to the story of the international effort to monitor and understand Hitler’s Germany in the 1930s.

Throughout this decade, this ‘relationship’ was little more than a flirtatious liaison between two partners. The two partners began to embrace only suddenly, in early 1939. And intimate though it latterly became, this relationship was at every stage riven by a state of mistrust and rivalry, characteristic of two countries that had been rivals and adversaries for centuries. Even in the spring of 1938, when Germany posed a strong threat, the French secret services were still closely monitor ing the activities of ‘notoriously anti-French’ and ‘very dangerous’ British intelligence agents, notably in North Africa, where they were judged guilty of secret ‘collusion’ with Spanish nationalists against French interests. At the same time, numerous figures in the British cabinet, including the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, wanted to avoid making a commitment to Paris: there was still time, they argued, for their policy of appeasement to satisfy Hitler’s demands and avoid war.

10

While the political relationship between Britain and France was central to the loose ‘network’ of foreign spy agencies that watched the Reich, several other countries also played their part. In particular, there was also close contact between the French and the Czechs, who had signed a vaguely worded treaty of ‘alliance and friendship’ in January 1924, and the Poles, who had also struck up a similarly worded alliance with Paris in 1921. Other countries also stood at the outer fringes of this loose network, including Holland, which despite its supposed neutrality gave underhand, low-level assistance to the British, as well as to the German, intelligence services.

Each of these countries had their respective spy services whose relations both mirrored but also helped to shape those of their political masters. Sometimes these services pulled closer together because their

9. Royal Navy—see Joseph Maiolo The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany 1933–9: A Study in Appeasement Palgrave Macmillan (1998). Soviet critics—see ‘Military Value of Russia’, 24 Apr 1939, CAB 27/624 TNA.

10. On French suspicions of and rivalry with the British, see ‘Services Spéciaux Britanniques’, 12 Mar 1937 and ‘Anglais en France’, 7NN 2229 SHD.