Acknowledgements

Thisvolumebeganasmydoctoralthesis,writtenandcompletedatNewcastle Universitybetween2012and2015.Ithashadalongperiodofgestationand expansionsincethoseearlydaysandthereare,therefore,manypeopleand institutionstothankforits finalshapeandpublication.

IwasoriginallydirectedtoPhilipVandPolybiusmanyyearsagobyLene Rubinstein,whoselecturesanddissertationsupervisionduringmyBAandMAat RoyalHollowayfuelledmyinterestintheancientworldandparticularlyancient MacedoniaandtheHellenisticperiod.Itwas,however,undertheenthusiastic, patient,andwiseguidanceofmydoctoralsupervisor,FedericoSantangelo,that theproject firstdevelopedandcametogether,andtowhomIofferthemost profoundthanksforguidingmyacademicdevelopment.Oursupervisionmeetingswerealwaysarewardingexperience,andIcameawayfromthembuoyedup withself-beliefandaneagerreadinesstotakeonthenextchallenge.Thelate ProfessorJohnMoles,mysecondsupervisor,wasequallyfundamentalformy knowledgeofhistoriographicalmattersandGreeklanguage.Gratitudemustalso gototheSchoolofHistory,ClassicsandArchaeologyatNewcastleUniversityfor theirawardofanArtsandHumanitiesResearchCouncilPh.D.Studentship, withoutwhichthisprojectwouldhavebeenimmenselymoredifficult.ThePh.D. communityatNewcastlebetween2012and2016wasafertileplaceforburgeoning academicaspirationsandfriendships(andstillis),andtheexperiencewouldnot havebeensorewardingwithoutthecompanionshipofAliChapman,Fiona Marsh,ChrisMowat,DavidLowther,LizzieCooper,FionaNoble,Frances Roberts-Wood,andVickyManolopoulou.TheInstituteofClassicalStudiesin Londonwasafrequenthomeformanyofmyundergraduateandpostgraduate years,andIcontinuetobeeternallygratefulforthisvastrepositoryofancient knowledgeandthewisdomofitsstaff.ManythanksalsogototheDeutscher AkademischerAustauschdienst(DAAD)andBorisDreyeratFriedrichAlexander-UniversitätErlangen-Nürnbergforthechancetotraveltoandstudy inGermanyinthe finalmonthsofthethesis’swrite-up,toFelixMaierinFreiburg forourconversationsaboutPolybius,andtoSabina,Johannes,andChristinafor theirwarmwelcome,continuousfriendship,andadventureswhileinBavaria (Franconia!).Ialsothankmyexternalexaminers,AndrewErskineandBrian McGing,notonlyformakingmyvivainDecember2015arewardingand constructiveexperience,butalsoforofferinginvaluableadviceaboutturningthe thesisintothepresentvolume.

BruceGibson,LisaHau,NikosMiltsios,andNicolasWiaterwereinspirations toafreshlycompletedandexhaustedPh.D.atthe ‘PolybiusandhisLegacy’ conferenceattheAristotleUniversityofThessalonikiinMay2016.OurdiscussionsaboutPolybiushavehelpedintheadaptationandexpansionofthethesis intothevolumeitistoday.TheUniversityofEdinburghshapedthenextyearin bothresearchandteachingmatters(2016‒17):thethesistookits firsttentative stepstowardbookhood,andmycolleagues,KimCzajkowski,BenediktEckhardt, AndreasGavrielatos,ChristianDjurslev(andTaylor),andEmanueleIntagliata madethe firstyearsofanacademiccareerimmenselymorerewarding.The UniversityofExetergenerouslyallowedmetocontinuemyacademicjourneyin 2017,andI(andthisbook)havegreatlybenefitedfromthebrilliance,passion,and strengthofmycolleaguesinthedepartmentofClassicsandAncientHistory,as wellastherigourandrichnessofitsresearchenvironment.Iamthankfultomy colleaguesLynetteMitchell,NevilleMorley,andDanielOgdenfortheirsupportof myHellenisticandAntigonidambitions,toElenaIsayevforherwiseandenergeticadvice,toRebeccaLanglandsforherkindnessandeverreadysupport,andto NicoloD’Alconzo,MariaGerolomenou,RichardFlower,ConsueloManetta,Irene Salvo,andCharlotteTupmanfortheirfriendship.Also,tomyPh.D.students, JuliusGuthrie,CharlotteSpence,andSorchaRoss,fortheirjoyofresearchand ourlongconversations.Youwillnodoubtgoontogreatthings.

Inthelastfewyears,andduringthepandemic,ithasbeentheAntigonid Networkthathashelpedtoshapethisbookandmythoughtsononeofthelast kingsofMacedonia.Ouronlineseminarsmadetheworklessthanklessinthe unendingdaysathome.Thanksaredueespeciallytomyco-directorAnnelies CazemierforherassistanceinsettingupanddevelopingtheNetwork,butalsoto MonicaD’Agostini,MichaelKleu,SheilaAger,PatWheatley,JohnThornton,and RobinWaterfield,forurgingmetocompletionandfuellingthethought-process.

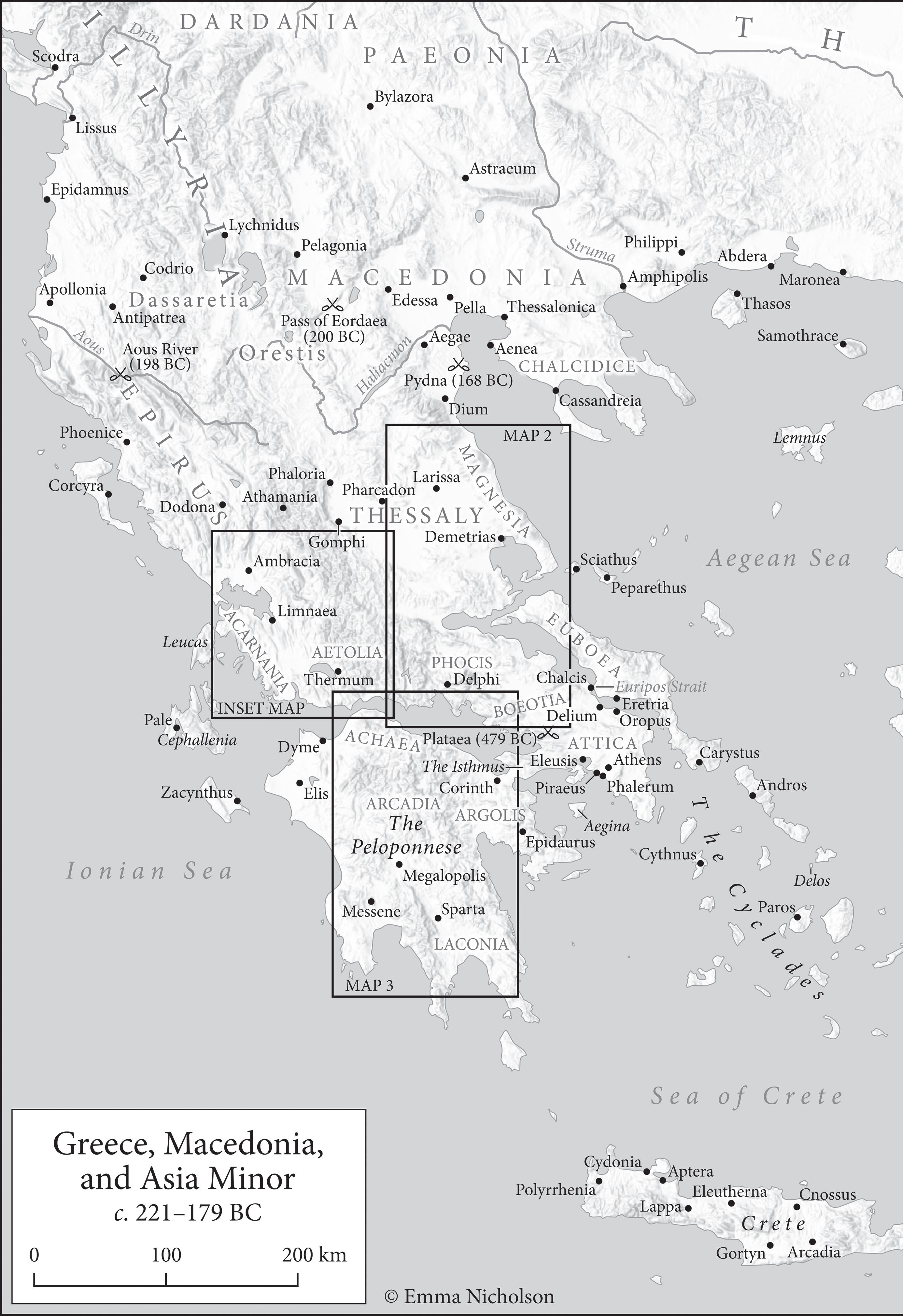

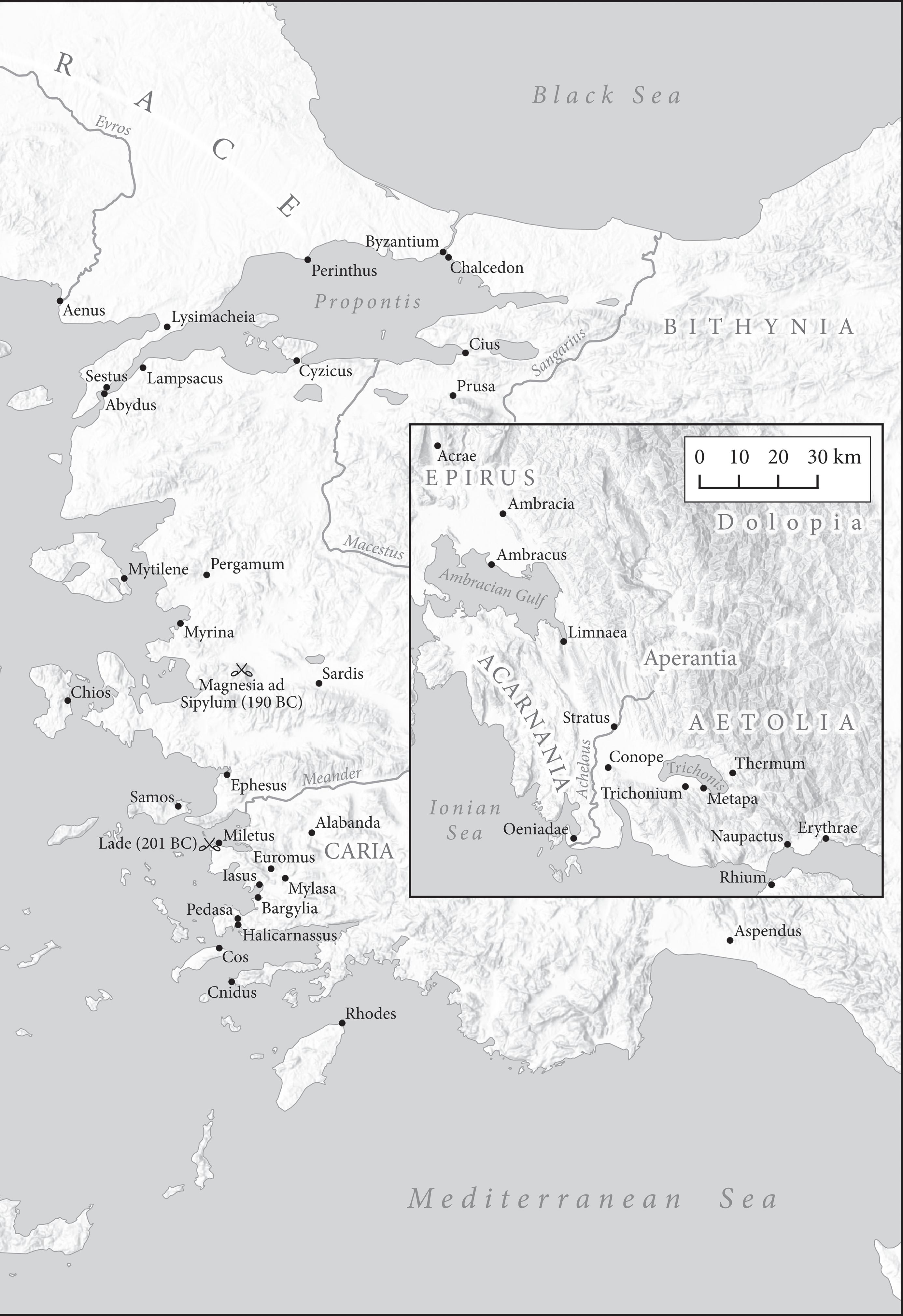

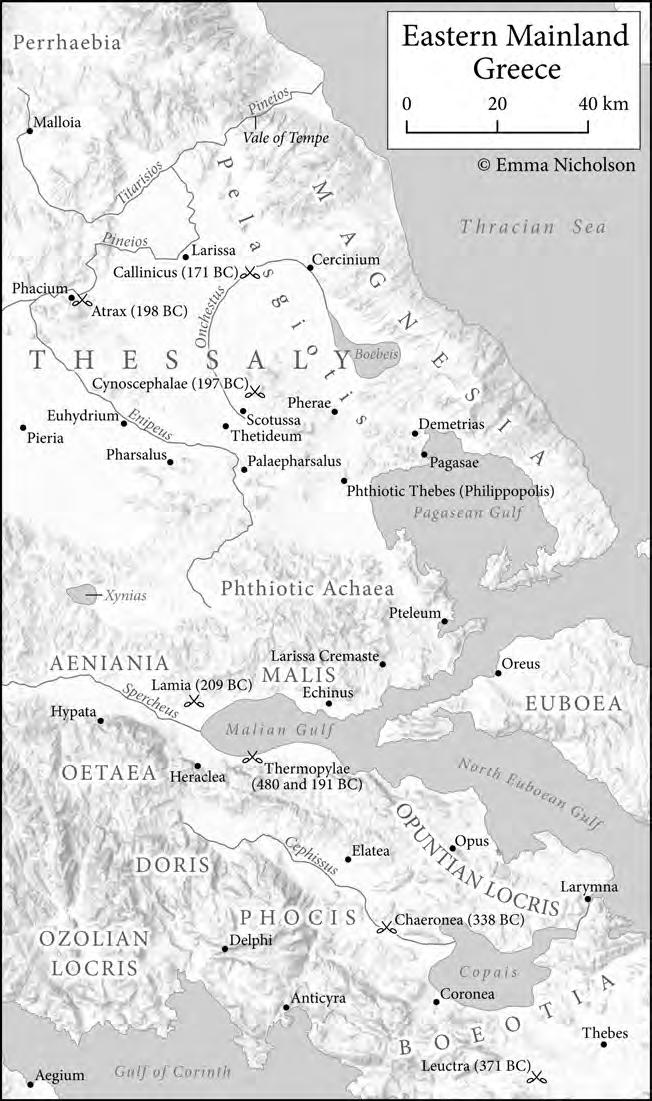

Ithanktheanonymousreviewersfortheirinsightfulcommentsandsuggestionswhichturnedthisbookintoamuchbetterwork.ThankyoualsotoMichael Athansonforhisbeautifulmaps,toCharlotteLoveridgeforagreeingtopublish thisbookandformakingtheprocessafairandfruitfulone,andtoJamie Mortimer,VaishnaviSubramanyam,andSaranyaRaviforpullingitalltogether attheend.

Finally,toKorra,whosatatmyfeetinthemanuscript’slaststagesandkeptme saneduringlockdownandcomfortedwhileill.TomyMumandDadfortheir constantencouragementandpatience,forcheeringmeonateverybattleand celebratingeveryvictory.Tomybrotherandsisterfortheirnever-endinglove, support,andwillingnesstolisten.Andtomyhusband,Ollie,whohasstoodbyme throughitall,readfartoomanyversionsofthisbook,andkeptmehealthywith hisspectacularfoodandadventures.Thiswouldnothavebeenpossiblewithout yourunwaveringbelief,trust,andlove.

Contents

Maps

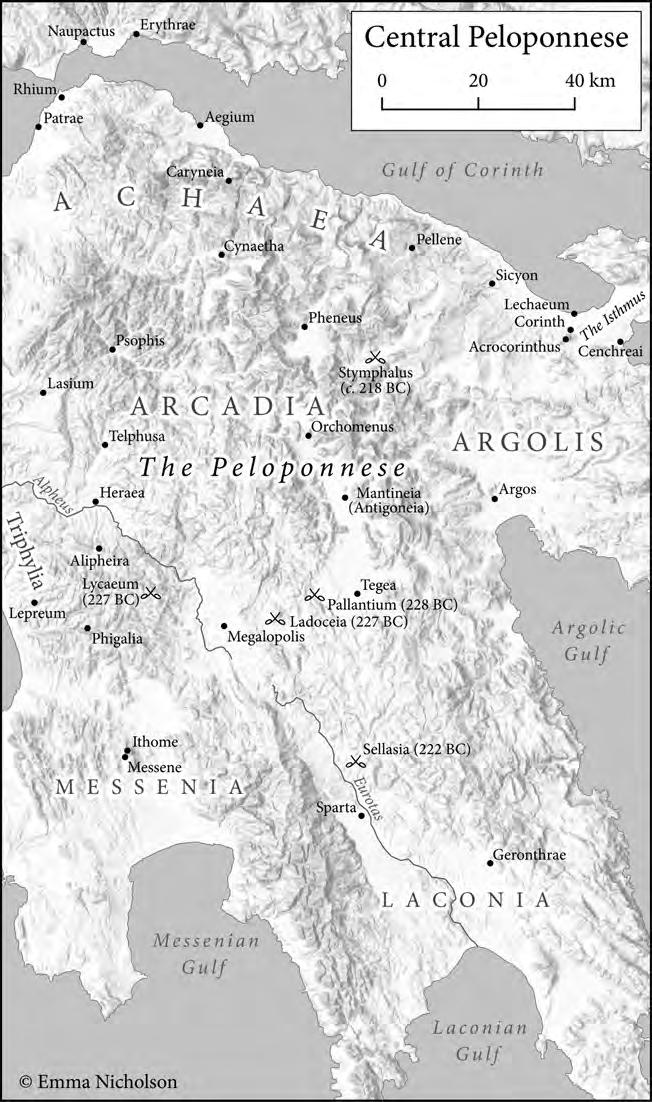

Greece,Macedonia,andAsiaMinor, c.221‒179 x EasternMainlandGreecexii CentralPeloponnesexiii

ListofAbbreviations xv

Introduction1

PhilipVandtheAntigonidDynasty2 PolybiusofMegalopolis4

FurtherHistoriographical,Literary,andDocumentaryEvidence forPhilipV7

TheStateoftheField:PhilipV12

TheStateoftheField:Polybius13

Polybius’ Purpose,Methodology,andAudience18

Tyche:The ‘Director’ ofthe Symploke andtheFateofMacedon23 TheStructureandAimofThisVolume25

1.ConstructingMacedonandtheWorldThroughanAchaean Perspective27

Part1:Polybius’ AchaeanPerspective27

Part2:TheRelationshipBetweenAratus,Achaea,and AntigonusDoson48 Conclusion57

2.TheDarlingoftheGreeksTurnsintoaTyrant59

Part1:TheAttackonThermum,218 61

Part2:TheAttemptonMessene,215 81 Conclusion99

3.PhilipVandHisGreekAllies101

TheSourcesandtheQuestionof ‘theGreeks’ 102

Part1:Philip’sTreatmentofHisAlliesBeforeMessene (220‒215 )107

Part2:Philip’sTreatmentofHisAlliesAfterMessene (215‒196 )118

Part3:TheLoyaltyandDefectionofPhilip’sGreekAllies151 Conclusion162

4.PhilipandtheRomans164

Part1:PolybiusandtheMacedonian–RomanQuestionin theSecondCentury 165

Part2:HellenicRome,BarbaricMacedon182

Part3:TheWaragainsttheBarbarian:TheSecondMacedonian War(200‒196 )205 Conclusion:ReversalsofConduct223

5.ATragicKing228

Part1:Polybius’ AccountofPhilip’sFinalYears(183‒179 )229

Part2:TheTragicModeofPhilip’sLastYears249 Conclusion265

6.WovenHistory,WovenLives267

Part1:PolybiusonBiographicalMaterialinHistory270

Part2:OneManAmongMany281

Part3:AComparisonofPhilip’sPortraitwithOtherKings (andHannibal)285 Conclusion324

Map1. Greece,Macedonia,andAsiaMinor, c.221‒179

Map2. EasternMainlandGreece ©EmmaNicholson

Map3. CentralPeloponnese

©EmmaNicholson

Introduction

AccordingtoPolybius, PhilipVofMacedonwasthebestandworstofkings.He wasabrilliantandbenevolentmonarchinhisearlyyears,the ‘darlingofthe Greeks’ andtheirprotectoragainsttheRomanbarbariansinthewest.Inhismidtwenties,however,hetookasuddenturnfortheworseandtransformedintoa vicious,irrational,and fickletyrant,pushinghissuccessestoofarandturninghis alliesandsubjectsagainsthim.HewassubsequentlypunishedbyFortuneforhis crimesagainstmenandgods,sufferingdefeatatthehandsoftheRomansand ultimatelybringingaboutthedownfalloftheMacedonianroyalhouse.Hetragically fellintomadnessinhislastyearsashisdomesticpoliciesrippedtheMacedonian stateapartandhissonsplottedagainsteachother,resultingintheexecutionofthe younger.Polybius’ Philipistheultimatetyrant,thedestroyeroftheMacedonian empire,theloseragainstRome,andawarningagainstirrationalityandpassion.

TheancientandmodernhistoricaltraditionsurroundingthisMacedonianking isheavilydependenton,andindebtedto,thisultimatelynegativeandtragic pictureofPhilipV.Yet,evenwithinhisnarrativePolybiusacknowledgesthat othersviewedandwroteaboutPhilipinamoreneutralandevenpositivelight (Plb.8.8).Theseopposingaccountsdonotsurvivethough,andPolybiusstands almostaloneintheextanthistoricalrecordofthemiddleHellenisticperiod;we areleft,therefore,torelyonhisportraitoftheking.WhilePolybiushaslonghelda reputationforbeingoneofthemostreliableoftheancientGreekhistorians,his impressionofthekingisone-sidedandcontrivedandaninvestigationofthis portraitwouldnotonlyrede fineandadvanceourknowledgeofPhilipV,butalso furtherthestudyofPolybiusandhis Histories.Throughtheanalysisoftheking’ s portrait,wewillbeinabetterpositiontounderstandthewaythatPolybiuswrote, conceived,andconstructedhis Histories,andtoappreciatethepolitical,historiographical,literary,andideologicalinfluencesandagendathatinformedthisvast work.Wemight ‘read ’ it,orpartsofit,inavarietyofwaysbeyondthehistorical:as apologia,diplomacy,andbiography.

Itshouldbenotedthatwhilethisvolumeintendstoquestionourhistorical understandingofPhilipV,itisnotahistoricalbiography.FrankWalbank’s1940 (revisedin1960)treatise, PhilipVofMacedon,remainsthesolecomprehensive historicalinvestigationofPhilip’slifeandcareerfrombirthtodeath,althoughitis nowoutdatedinanumberofrespects.Therehavebeenreconsiderationsof variousproblemsinsubsequentyears,aswellasnewworkontheepigraphic, numismatic,andarchaeologicalevidencerelevanttohim.Thismonograph,

however,aimstocontributetotheadvancementofthestudyofPhilipVfroma historiographicalandliteraryperspective.

PhilipVandtheAntigonidDynasty

PhilipV(238–179 ),sonofDemetriusIIandPhthia,andsuccessortohisuncle AntigonusIIIDoson,ruledMacedonfrom221to179 .¹Hewasthepenultimate kingoftheAntigonidempireandthe firstHellenistickingtocomeintoconflict withRomeinitsgradualpenetrationintotheeasternMediterraneanattheendof thethirdandearlysecondcenturies .Thatclashhadepoch-makingimplications.Philipisprimarilyrememberedforhisill-fatedconfrontationwiththe Italianpowerandforcausing(ifindirectly)hiskingdom’sdefeatanddestruction byRomanhandsinthereignofhisson,Perseus.Hewasthedefeatedpowerinthe fightforsupremacyintheMediterraneanandthisfacthasoftenlefthiman understudiedandunderratedindividual,especiallybythosemoreinterestedin Rome’ssuccessanddevelopmentintoaworldpower.Yet,despitetheconsequencesofhisreign,Philipcanbecreditedasoneofthemostsuccessfulofhis predecessorsafterAlexandertheGreat.Heruledforforty-twoyears,thelongest rulingperiodofaMacedoniansincePhilipII,and,beforeRomanintervention, wasalsoeffectiveinre-establishingcontroloverGreeceandexpandingMacedon beyondhertraditionalbordersintoIllyria,Thrace,andtheAegean.Whilethe greaterlengthandsuccessofhisreignmaypartlybeduetostabilizingconditions intheHellenisticworld,aswellasthedwindlingnumberofsuitableusurpers, bothareremarkablefeatsconsideringtheviolentandvolatileconditionsof Hellenistickingship.ItwouldthereforebehardtobelievethatPhilipcouldhave beensolong-lastingwithoutpossessingqualitiesthatrenderedhimeffective.

PhilipVwasthesixthkingoftheAntigoniddynastyandthefourthtoruleover theterritoryofancientMacedonia.AfterthechaosoftheSuccessorWars, AntigonusIIGonatas(319–239 ;reigned277–239 )had finallygained controloftheregionin276/5 .²HethendefeatedPyrrhusatArgos(272 ), installedpro-MacedoniantyrantsinPeloponnesiancities,gainingavaluable footholdinGreece,andsuccessfullycrushedresistancefromAthensandSparta intheChremonideanWar(263 ).In243 ,however,AratusofSicyon,a leading figureoftheAchaeanLeague,compromisedthegrowingMacedonian

¹ForhistoricalbiographiesofPhilipV,seeWalbank(1940)andD’Agostini(2019)fora re-evaluationofhisearlyyearsuntil212 .ForPhilip’smother,seeTarn(1924)17–23;Hammond &Walbank(1988)338;Ogden(1999)179–82;Carney(2000)190–1;andD’Agostini(2019)13–16.For Philip’swife,seeD’Agostini(2022)45–64.

²ForAntigonusIIGonatas(319–239 )seePlb.2.43–5,9.29,34,Plut. LifeofDemetrius 39–40,51, 53,Just.17.2,24.1,25.1–3,26.1–3.ForscholarshiponGonatas,seeWalbank(1984a)221–55,(2002) 258–76;Hammond&Walbank(1988)259–316;andGabbert(1997)forabiography,andWaterfield (2021)forafreshtakeonhislifeandcontext. 2

presenceinthePeloponneseby(re-)capturingtheAcrocorinthus,astrategically importantfortificationcontrollingtheIsthmusandaccesstothePeloponnese, andremovingitsMacedoniangarrison.Whilethisencouragedanumberof PeloponnesiancitiestodefectandjointheLeague,MacedonstillretainedinfluencethroughoutmuchofGreece.In239 ,afterthirty-eightyearsonthethrone andattheadmirableageof80,AntigonusGonatasdiedleavingthekingdomtohis son,DemetriusIIAetolicus(275–229 ;reigned239–229 ).Demetriusonly ruledfortenyears,yethewasalsosuccessfulinexpandingMacedonianinfluence throughoutBoeotia,Euboea,Magnesia,andThessaly,despitethecombined effortsofanAchaean–Aetolianallianceagainsthim.³Hewaskilledin229 fightingtheDardaniansandlefthis9-year-oldson,Philip,andtheruleof MacedoniaundertheguardianshipofhiscousinAntigonusIIIDoson.Inthe eightyearsthatDoson(263–221 ;reigned229–221 )heldthethrone,he defeatedtheDardanians,putdownarebellioninThessaly,endedtheconflict betweenEpirusandtheAchaeanLeague,andformedanagreementwiththelatter in224 .InreturnforhismilitarysupportagainsttheSpartanking,Cleomenes, theAchaeansallowedhimtoreinstateaMacedonianpresenceinthePeloponnese bytherepossessionoftheAcrocorinthusandbytheestablishmentofthe Symmachy(orHellenicAlliance).Doson’sdiplomaticandmilitaryskillproved vitalinstabilizingMacedon’sstrength,anditwasintothisperiodofgrowing securitythatPhilipVcametopower.

Philipwasonly17whenhesucceededhisuncle,⁴ youngereventhanAlexander hadbeenwhenhesucceededhisfather.Yet,despitehisyouth,Philipsoonproved himselftobeacompetentandsuccessfulmilitarycommander,aswellasareliable partnerandbenefactortohisGreekallies.Hisearlypoliciesrevolvedaround securinghispositionandinfluenceinMacedoniaandmainlandGreece,andthe SocialWarfoughtinaidofhisGreekalliesagainsttheAetolians(Plb.4.26–37, 4.57–5.105;Just.29.1).Attheendofthiswarin217 ,havingsecuredGreeceto theSouth(Plb.5.104–5;Just.29.2–3),Philipwasabletopursuehisownambitions ofconquest.Itwaswhenhisgazeturnedwestthathebecameembroiledinconflict withRome;conflictwhichwouldeventuallyleadtotheFirstandSecond MacedonianWars(211–205and200–196 respectively).⁵ Afterhisdefeatat

³ForDemetriusIIAetolicus,seeJust25.4,26.2–3,28.1–3;andalsoTreves(1932)168–205,Walbank (1984b)446–67,andHammond&Walbank(1988)317–36.ForAntigonusIIIDoson,seeJust.28.3–4, 29.1;andTreves(1935)381–411,Piraino(1952–3)301–75,Welwei(1967)306–14,Walbank(1984b) 446–67,Hammond&Walbank(1988)337–64,andnotablyLeBohec(1993)foradetailedbiographical account.

⁴ Plb.4.2.5,4.5.3–4,Just.28.4.16,29.1.1.Justin’sclaimthathewasonly14uponhisaccessionis incorrect,asPhilipwasbornin238 andcametothethronein221 (Plb.4.2.5).SeeFine(1934) 100andWalbank HCP I290,450.ForPhilip’sfamily,ascenttopower,andrelationshipwithDoson, seeD’Agostini(2019)13–29,39–41.

⁵ FortheFirstMacedonianWar,211–205 :Plb.9.18–11.7;Livy26.24–29.10;App. Mac. 1–3.The SecondMacedonianWar,200–196 :Plb.16.27–18.48;Livy31.1–33.35;App. Mac. 4–9.4,Just. 30.3–4.

thebattleofCynoscephalaein197,Philip’srelationshipwithRomebecamemore cooperativeforatimeasheaimedfortherecoveryofMacedonianstrengthand resources,evenaidingthevictorsintheirwaragainsttheSyriankingAntiochus III(Plb.21.3;Livy36.4–38.40;App. Mac. 9.5–6).Inhislateryears,however,this friendshipbrokedownasPhilipaimedyetagainforexpansion,thistimein ThraceandDardania,andRometriedtocurtailhisambitionsandmovements. Relations finallyworsenedin184tosuchanextentthatthekingissaidtohave thoughtwarinevitableandactivelybeganpreparationsfortheconflict(Plb. 22.13–14;Livy39.35;App. Mac. 10).Thekingdied,however,beforewarerupted andhissonPerseuscontinuedhisfather’spoliciestorecoverthestrengthof MacedonandprepareforwaragainstRome(Plb.22.18.10,25.3.1,25.6;Livy40.57, 42.11,42.48;cf.App. Mac. 11.1,8,Just.32.3–4).WhiletheMacedonian–Roman relationshipwasstableatthebeginningofPerseus ’ reign,however,severalyears lateritalsoturnedhostileasthenewkingacquiredwidespreadsupportthroughoutGreeceandbegantoexpandintoterritorybelongingtoRomanallies.The ThirdMacedonianWarbetweenPerseusandRome,andtheking’sdefeatat Pydnain168(Plb.29.17–18;Livy44.42;Plut. Aem. 19;Just.33),wouldmark theendoftheMacedonianmonarchyandthebeginningofRomancontrolover theregion.

PolybiusofMegalopolis

MuchofourknowledgeofPhilipandthisperiodcomesfromliterarysources,the mostimportantofthesebeingPolybiusofMegalopolis’ Histories.Itisthrough Polybius’ narrativethatwearepresentedwithourfullestpictureofthekingand ourowninterpretationsofhimhavebeen,andstillare,greatlyinfluencedbythis reliance.Whilelaterauthorsrevealafewalternativeperspectivesandattitudes towardsPhilipV,thosethatsurvivealsoremaingreatlyindebtedtoPolybius’ largelynegativeaccountofhim(seebelowforfurtherdetails).Anyconsideration oftheMacedoniankingmustthereforeengagewiththislimitation.

Polybius’ mainobjectiveinwritinghis Histories wastorecordhowandbywhat means,inthespaceof fifty-threeyears,Romereachedadominantpositioninthe Mediterranean(Plb.1.1.1;3.1.4).Itwasavastenterprisewhichtookupforty books,coveringthewholeMediterraneanand,withtheinclusionofhisintroductiontotheperiod,extendingoverahundredyears.Itisaworkofgreatdetailand carefuldeliberation.Itspotentiallyunwieldytopicishandledwithintelligence, producinganarrativewithdiscernibleunityandcoherence.Hisoriginalthirtybookplanintendedtonarrateeventsfrom221,continuingfromhispredecessor Aratus’ narrative(4.2.1)andbeginningwiththesuccessionofseveralnewleaders totheworldpowers,uptothedefeatofMacedonin168 (3.1.9,3.3.8–9).This event,inhismind,markedtheendofRome’srisetopower:shehaddestroyedthe

CarthaginianandMacedonianempires,theSeleucidsweresubdued,andEgypt wasstillrelativelyweak(3.2–3).However,Polybiusdecidedtoextendhisnarrative downtothedestructionofCarthageandCorinthin146 ,addinganotherten bookstohisalreadyvastwork(3.4).Thiscontinuationallowedhimnotonlyto covereventsatwhichhehimselfwaspresent(3.4.13;4.2.2),butalsotoincludea discussionabouttheconsequencesofthisnewhegemonicpowerandthecorrect waystogovernandruleanempire.⁶ Itwascomposedalmostcontemporaneously withPhilip(238–179 )fromabout150 onwards,andPolybiushimselfwas aneyewitnesstothedefeatofPhilip’ssonPerseusintheThirdMacedonianWar in168 (3.4.13).Polybius’ personalparticipationineventsnodoubtplayeda crucialroleinshapinghistreatmentoftheperiodanditsextension,aswellas influencinghisunderstandingandinterpretationofaffairsandcharacters.

Born,accordingtothemostreliableestimate,⁷ in208or200 ,Polybiuswasa citizenoftheprominentArcadiancityMegalopolis,locatedinthenorth-central PeloponneseandamemberoftheAchaeanLeaguefromthethirdcentury onwards.⁸ ThisconfederationofPeloponnesianstatesPolybiusdescribesinglowingtermsintheintroductiontohisnarrative(seeChapter1)andclaimswas primarilyconcernedwithmaintainingindependenceandfreedomfrom MacedonianandRomancontrolinthethirdandsecondcenturies (Plb. 2.37.9–11).Thehistoriancamefromawealthy,politicallyactivefamilyandhe himselfrecordshowhisfatherLycortasservedas strategos ,thehighestofficeofthe AchaeanLeague,andwasinvolvedintheLeague’sdealingswithRomefrom187 onwards.⁹ Fromhisyouth,PolybiuswasequallyenmeshedinAchaeanpolitics andin170/69 ,ataroundtheageof30,waselectedtothesecond-highestoffice oftheLeague, hipparchos (28.6.9).

Itwasduringthistermofoffice,however,thatPerseuswasdefeatedbythe RomansandtheMacedoniankingdomwasbrokenupandplacedunderRoman control.ThisdefeataffectedPolybiuspersonally,alongsideathousandotherproMacedonianorneutralAchaeans,ashewasdeportedtoRomeasahostage toensurethecomplianceoftheAchaeanLeague.¹⁰ Polybius’ politicalcareerwas cutshort.Yethedidnotallowthisturnoffatetoforcehimintoalifeofinactivity.

⁶ Foradiscussionofthenature,purpose,anddateofcompositionofthecontinuationofPolybius’ originalplananditsrelationtowiderancienthistoriography,seeWalbank(1985c)325–43andMehl (2013)25–48.

⁷ TheevidenceforPolybius’ birthisunfortunatelyindecisive.See ‘Polybius’ byThornton(2012)in the EAH.Somescholarsbelievehewasbornasearlyas208–207 :Pédech(1961)145–56putshisbirth asearlyas208 ,Musti(1965)381–2in205,Dubuisson(1980)72–82in208;Ferrary(1988)283n.69 in207.Othersplaceitcloserto200:Cuntz(1902)20–1,75–6;Ziegler(1952)1445–6;Walbank HCP I1–6(1959)1n.1and(1972)6–7;andEckstein(1992)387–406.

⁸ ForanoverviewofPolybius’ life,works,andlegacy,seeDreyer(2011)andNicholson(2022);for moredetailedexplorationofhisbackground,education,andpoliticalactivities,seeThornton(2020b).

⁹ Cf.Plb.2.40;22.3,12–16;23.12,16–17;24.6,10;28.3–6;29.23–25;36.13;37.5.

¹

⁰ Cf.Plb.30.13.6–11,32.1–12;31.2,11–15;32.3.14–17;33.1.3–8,3,14;Livy45.31.9;Paus. 7.10.11–12.Foranoverviewofhisdetainment,seeErskine(2012)17–32.

Hewasfortunateenoughtoremainwithinthecityandsoonmadelifelong connectionswithanumberofprominentRomans,mostnotablythevictorat Pydna,PubliusScipioAemilianus,sonofLuciusAemilianusPaullus,andhis circle(Plb.31.23–4,29.8).¹¹ItwasprobablyduringhisinternmentthatPolybius beganhisvasthistoricalenterprise.Havinggainedthetrustofthecurrent generationofRomanpoliticalleaders,Polybiusheldaprestigiousposition whichnotonlyaffordedhimaccesstoGreekandRomansourcesforhis Histories,butalsoenabledhimtocollectinformationfromeyewitnessaccounts andpublicrecords,andexplorethegeographicalfeaturesofprominentsitesand locationsbyextensivetravel.¹²HewasamentorandcompanionofScipio AemilianusinhistravelstoNorthAfrica,Spain,andGaul(Plb.3.59.7),crossing theAlps(Plb.3.48.12),andevenstandingbytheRoman’ssideatthedestruction ofCarthagein146(Plb.38.21–2).¹³Hemayalsohavesailedalonebeyondthe PillarsofGibraltarintotheAtlantic,perhapsvisitingBritain(Plb.34.15.7;Pliny Nat.Hist. 5.9,forBritainseePlb.34.10.7),andtoAlexandriaandSardis,although thedatesofthesetwolattertripsareuncertain(Alexandria34.14.6;Sardis 21.38.7).FollowingthedestructionofCorinth,Polybiuspersonallyfacilitated thepoliticalsettlementofGreeceunderRomeandreceivedmultiplecivichonours fromhisnativecityandanumberofothersinthePeloponnese(Plb.39.5.4;Paus. 8.9.1f.;8.37.1f.;8.30.8;8.44.5;8.48.8).¹⁴ Workonhis Histories continueduntilthe endofhislife.Hediedaround118 afterfallingfromahorseattheageof82 (Ps.-Lucian, Macrobioi, 23;cf.Plb.3.39.8withareferencetotheViaDomitialaid downin118 ).¹⁵

WhilePolybiusremainsourmostimportantsourcefortheperiod,oneofthe primaryissueswithhisaccountisthatthemajorityofitisfragmentary.Ofthe originalfortybooks,onlyBooks1–5surviveintheirentirety,Books17and40are

¹¹TheexistenceoftheScipionicCircle,anintellectualphilhellenicgroupwhichcontributed substantiallytowardsthespreadofGreekcultureinRome,haslongbeenacontroversialissue.For thosewhohaveaccepteditsexistenceasreal,seeGruen(1968)17,Christ(1984)92–102,Ferrary(1988) 589–602,andDreyer(2006)81–3.Thetideisrunning,however,withthosewhoseetheCircleasa literarydeviceprovidingahistoricalframeworkforthedialoguebetweenGreeceandRome:see Strasburger(1966)60–72,Astin(1967)294–306,Zetzel(1972)176–7,andForsythe(1991)363and Sommer(2013)307–18.

¹²SeeWalbank(1972)74–7forPolybius’ roleinthiscommunity.Forthefreedomaccordedto Polybiustoresearchandtravel,seeMioni(1949)13,Walbank HCP I4–9and(1972)76,Pédech(1964) 524–5,Champion(2004)17andMcGing(2010)140,whoclaimthathewasallowedtomovearound ItalyandtothewestwithScipiobeforehisdetentionhadended.Forviewsassertinghewasmore restrictedinhismovementsbeforehisreleasein150,seeCuntz(1902)55–6andErskine(2012)28–30.

¹³Walbank HCP II382.

¹

⁴ HonorificportraitsandstatueswereerectedatCleitor,theshrineofDespoinaatLycosoura, Mantinea,Megalopolis,atOlympiabytheEleans,Pallantium,andTegea.Cf.Henderson(2001)29–49; Ma(2013)279–84.

¹⁵ Cf.n.7abovefortheissueofPolybius’ birth.Dubuisson(1980)objectstotheuseofbothPs.LucianandPlb.3.39.8,referringtotheViaDomitia,asevidenceforthechronologyofPolybius’ life. Eckstein(1992)387–406convincinglyrefutesDubuisson’sargumentsandstandsby118 for Polybius’ death.

completelylost,andtheremainingthirty-threearefragmentarytovarying degrees.¹⁶ Thisposesconsiderableproblemswhenwewishtospeakaboutthe contentofthelatterbooksandthehistorian’sdevelopmentofnarrative,characters,andthemes.Inourcase,wearefortunatetohaveacompleteaccountofPhilip V’searlyyearsupto216 inBooks4and5;yet,whilewehaveareasonable amountofnarrativematerialuntilhisdeathinBook25,theaccountsofmany importanteventsofhislife(forinstancehispactwithAntiochusIIIin203andthe detailsofhislastyears)areentirelylostandmustbeinferredfromotherpassages inthe Histories orsupplementedbytheworkofothers.Nonetheless,aswillbe discussedinthenextchapter,Book2andthedescriptionoftheAchaeanLeague containedwithinitproveusefulinunderstandingPolybius’ attitudetowardsand depictionofMacedonandPhilip.

FurtherHistoriographical,Literary,andDocumentary EvidenceforPhilipV

CertainareasofPolybius’ Histories canbesupplementedbyotherancient works.ThemostnotableandhelpfuloftheseisLivy’ s AbUrbeCondita.Livy (64/59 – 17)recordedthehistoryofRomefromitsearliestbeginningstothe historian’sowntimein142books,yetonlyaquarterofthisvastworkremainsto ustoday.Weare,however,fortunatethatLivy’saccountbetween211and167 (Books26–41),thesecondhalfofPhilip’sreignandthatofhisson,ispartofwhat survives,andheusedPolybius’ Histories extensivelyasasourcefortheseevents. DespitecertainGreekandMacedonianaffairsbeinggreatlycompressedand temporallydisplacedwhenRomehaslittleinvolvementinthem(forexample, Philip’sAegeancampaignintheyears205–201),Livy’shistoryhelpsustocheck Polybius’ accountwhentheydooverlap(forinstance,intherecordingofthebattle ofCynoscephalae)and fillsinimportantfragmentaryormissingepisodes,andat timesalmostquotesPolybiusverbatim(forinstance,thedefectionoftheAchaean LeaguetoRomein198 andthedisputebetweenPerseusandDemetrius).¹⁷ Livy willprovetobeausefulsupplementtoPolybius’ accountinthefollowing investigation,therefore,particularlyinChapters3and6inreconstructingthe historicaleventsleadinguptoandduringtheSecondMacedonianWarandthe endofPhilip’slife.

¹⁶ ForthemanuscripttraditionofPolybius,seeMoore(1965)andSacks(1981)11–20.

¹⁷ ForLivy’suseofPolybius’ narrativeforGreekeventsinBooks31–45andhiscarefuladaptation andrearrangementofitforhisownliterarypurposesseeespeciallyTränkle(1977)and(2009)476–95, andBriscoe(2013)117–24.ThisviewisinoppositiontotheoldertraditionthatLivywas ‘carelessand casualinhisscrutinyofhissources’,advocatede.g.byWalsh(1958)355–75.SeealsoEckstein(2015) 407–22forhispreferenceforPolybiusoverRomanannalists.

Theworkofthe first/second-century biographerPlutarchwillalsobe helpfulforourinvestigationofPolybius’ portrayaloftheAchaeanLeague,its leaders,andtheirearlyrelationshipwiththeMacedonianking.Plutarch ’ s Aratus isouronlyothersurvivingliterarysourcebesidesPolybius’ Histories todescribe (andcelebrate)thecareeroftheAchaeanpolitician,AratusofSicyon,who oversawthere-admittanceofMacedonianinfluenceintothePeloponnesein224 andwholaterbecameanimportant figureatPhilipV’scourt.¹⁸ Whilewemust becautiouswhenusingPlutarch’ s Lives forhistoricalpurposesandrecognizethat hisaimwastoillustratecharacterratherthanpreservehistoricalaccuracy,his accountprovidesacounterbalancetoPolybius’ biasedandselectiveaccountof Aratusandreveals,aswewillexplore,agreatdealabouttheMegalopolitan historian’sworkingsandtheextenttowhichpoliticsaffectstheportraitsof individualsinhis Histories.¹⁹ Plutarch’ s Aratus and AemiliusPaullus alsosupply somebriefinformationonPhilipandMacedonandareexcellentexamplesofhow differentinterpretationsofonecharactercanbeproducedbythesameauthorin twodifferentcontexts.Plutarch’spictureofPhilipVinhis Aratus ishighly negativeandrestsonthemoredisreputablepartsofPolybius’ accountofthe king(Plut. Arat. 46–54:hisattemptonMessene,hischangeintoalasciviousman andpernicioustyrant,andhispoisoningofAratus),butthePhilipthatissketched inthe AemiliusPaulus isfarmorepositiveandalmostentirelyfreeofnegativity (7–8:PlutarchrelatesthehighhopesPhilipinspiredinGreeceandMacedonia,his humblepostureafterhisdefeatbyRome,andhisclevernessinpreparingforwar againstRomeinhislateryears).Thedifferentperspectivesandliteraryrequirementsofthesetwo Lives arewhatchangesthepictureofPhilipinthem:inthe Aratus, theeponymousheroiskilledbyPhilipandsotheultimateimageofthe kingneedstobethatofavillain;inthe AemiliusPaulus Philipismentionedina morepositivewaytoheightentheincompetenceofhisson,Perseus,whohas recentlybeendefeatedbyAemiliusPaulus.WhilePolybius’ depictionofPhilipis farmorecomplexthanPlutarch’sandfocusedmoreonhistoricalaccuracyand completeness,wewillseethroughthecourseofthisvolumethathetooshapesthe king’scharacterinsimilarwaystosupporthisownwiderpoliticalleanings, rhetoricalarguments,andinterpretationofhistoricalevents.

OtherauthorssuchasAlcaeusofMessene,DiodorusofSicily,Appianof Alexandria,Justin,andJoannesZonarasalsosupplyliterarymaterialrelatingto

¹⁸ Koster(1937),Porter(1937),andManfredini,Orsi,&Antelami(1987)offerhistoricalcommentariesforthis Life.SeealsoPelling(2002)288–91andStadter(2015)161–75forhistoriographical discussions.

¹

⁹ SomescholarsstillconsiderPlutarchahistorian,however,ashisworkisgenerallycloserto historiographythanencomiaorbiographicalnovels;cf.Wardman(1974)1–18andPelling(2002) 147–52.ForPlutarch’sadaptationofsourcematerial,seePelling(2002)91–106,143–70,aswellas Russell(1971/2001)100–16andWardman(1974)1–37,153–89forhisattitudetowardstruth, fiction, andhismanipulationofhisnarrative.ForPlutarch’sconstructionofcharacter,seeWardman(1974) 105–44. 8

PhilipVandMacedon,althoughwiththeexceptionofAlcaeus(whowasa contemporaryofPhilip)theirworkswerecomposedmuchlaterthantheevents recorded,andPolybius’ influenceisoftenquiteplain.Alcaeus(latethirdtoearly secondcenturies )isourearliestliterarysourceforthekingwith fiveofhis twenty-twosurvivingepigramsdirectlyaddressingPhilip.²⁰ Whilethepoetic genreandhostilenatureofthesepoemsmakehistoricaluseofthemproblematic, theydoonoccasionofferadditionaldetailsthathavenotsurvivedinPolybius’ or Livy’sworks(forinstance,Philip’sattackontheThracians)andarehelpfulin elucidatingcontemporaryGreekattitudestowardsPhilipV,hispursuitofexpansion(see Anth.Pal. 9.518),andhisconflictwithRome(see Anth.Pal.5).The MacedoniankingalsofeaturesintheimmenseuniversalhistoryofDiodorus, althoughtheportionoftheworkthatpertainstothethirdandsecondcenturies andPhilipisgreatlyfragmented(forPhilipsee25.18;28.1–12,15;29.16,25–30; 30.5;31.8)andthefewsurvivingexcerptspertainingtothekingarebriefand clearlyderivativeofPolybius.²¹ThesameistrueofAppian ’sportraitofPhilipin his MacedonianWars (recordingtheeventsbetween215and167 ),whichagain survivesinapitifulstate.²²ForthePunic,Macedonian,andSyrianwars,Polybius’ Histories wasakeysource(cf.thereferencetotheHellenistichistorianat Pun. 132.628–31),althoughAppianalsohadaccesstoothersources(cf.theSibylline booksat Mac.2)andtemperedPolybius’ hostileviewofPhilipwithamoreneutral one.²³Justin’sepitomeofPompeiusTrogus’ voluminous first-century history oftheMacedonianmonarchy(HistoriaePhilippicaeettotiusmundiorigineset terraesitus)remainsavaluabletextforitscontinuousifbriefdescriptionofthe complicatedperiodafterAlexander’sdeath.PolybiuswasalsoasourceforTrogus/ Justininrecordingthethirdandsecondcentury,²⁴ yethisdepictionofPhilip differsmarkedlyinthatthekingispresentedinafarmorefavourableandactive

²⁰ These fiveepigramswerewrittenbetween219and196andinclude Anth.Pal. 7.247,9.518,9.519, 11.12,16.5and16.6.FordiscussionofhisepigramsonPhilipV,theirtoneandmeaning,seeDeSanctis (1923)1,9;Walbank(1942)134–45and(1943)1–13;Momigliano(1942)53–64=(1984)431–46; Edson(1948)116–21;Gutzwiller(2007)117;andJones(2014)136–51.

²¹SeeEckstein(1987b)332–4and(1995b)225–9,232,268n.117,Sacks(1990)33–54,and Baronowski(2011)108–13forDiodorus’ useandadaptationofPolybius’ work.Foracomparisonof theirworkingmethodologiesinwritinguniversalhistory,seeSheridan(2010)41–55,Sulimani(2011) ch.1,andHau(2016)73–123.

²²ForaninvestigationofAppian’saccountofPhilipV,seeD’Agostini(2011)99–121;forhis accountoftheMacedonianwars,seeMeloni(1955);forAppian’suseandadaptationofPolybiusinhis Syriake seeRich(2015)65–124;andforhisaccountoftheThirdPunicWarandrelationshipwith Polybius,seeMcGing(2018)341–56.

²³ FRH 46.

²⁴ Just.29.1.1–8closelyparallelsPolybius’ statementat3.2.4–11thatallthekingdomsoftheworld underwentchangeatthistime,29.3.1correspondstoPolybius’‘cloudsinthewest’ speechat5.104,and 30.4.12preservesPolybius’ observationsaboutPhilip’syouth,althoughplacesitmuchlaterinthe mouthofFlamininusatCynoscephalae(Plb.4.2,3,5,22,24,77).

light.²⁵ Justin’sepitomepreserves,therefore,thevestigesofalosttraditionfrom the firstcentury thatwasfarmorepositivetowardsPhilipV.²⁶ Thisonly reinforceshowmuchPhilip’sancientandmodernlegacyisbeholdentothe negativeandpoliticallyloadedimageofthekingproducedbyPolybius,and whyreassessmentofthisportraitissonecessary.Yet,likeDiodorusand Appian,Justin’scontributiontothehistoricalreconstructionofPhilipVislimited (28.3–4,29.1–31.1,32.2–4):hisepitomeisextremelycondensed,lacksdetailand omits,forexample,thedistinctionbetweentheFirstandSecondMacedonian Wars,Philip’scampaignintheAegean,andhiscooperationwithRomeintheir waragainstAntiochusIII.The finalliterarysourcetocontaininformationabout PhilipVisZonaras’ twelfth-century EpitomeofHistories.Muchofhisaccount ofthehistoryoftheRomanRepublicisderivedfromthelost RomanHistory of CassiusDio,whichseemstohavecontainedareasonablydetailedaccountofthe period.Yetagain,whilePhilipV’sinteractionswithRomearepreservedinBooks 8and9ofZonaras,thereislittletoaddtotheearlieraccountsofPolybiusand Livy.BecauseoftheirrelianceonPolybiusandlimitedcontributiontothehistory ofPhilip,theworksoftheselaterauthorswilltakeonlyacursoryroleinthe followinginvestigation.

Inadditiontotheliterarysources,overthelast fiftyyearstherehasalsobeenan increasingamountofepigraphicandnumismaticevidencerelatingtoPhilip Vcomingtolight.Intermsofthestudyoftheepigraphicmaterial,thesurvival ofanumberofPhilip’slettersand diagrammata allowsusaninvaluableglimpse intotheking’sself-presentationasabeneficentandpiousmonarch,hismediationswithandbetweencitiesandMacedonianagents,aswellashismilitary, economic,andreligiouspolicies,andfamily.²⁷ Thesecondvolumeof

²⁵ ItisPhilip,forinstance,whourgestheGreekstofollowhimonaPanhellenicventureagainst RomeatNaupactus,notAgelaus(29.2.8–3.5);theRomansaresaidtobewaryofPhilipbecausethey recognizetheancientvalouroftheMacedoniansandthenewking’senergyandambition(29.3);the responsibilityforstartingthewarfallsontotheRomanswho,itissaid,keeptryingto findapretenceto attackPhilip(30.3.1,6);andtheMacedonianandRomanarmiesappearfarmoreevenlymatchedinthe battleofCynoscephalaein197 (30.4)SeeD’Agostini(2015)121–44forfurtherdiscussionofPhilip VinJustin.

²⁶ SeealsoPolybius’ ownacknowledgementofamorepositiveviewofPhilipVatPlb.8.8.3–6.

²⁷ Thelettersinclude:Philip’smediationbetweenthecityofMylasaandhisagentOlympichus (I.Labraunda 4,5,and7;Hatzopoulos(2014)107–10;andD’Agostini(2019)152–4);hisconfirmation tothecitizensofAenusinAmphipolisofhissupportforAenianexiles(Hatzopoulos(1996)II30–1,no. 9);hisinterventionincitizenshipreformsinLarissa(Syll.³ 543= IG IX2,517;cf.Lolling(1882)61–76; Robert&Mommsen(1882)467–83;Hannick(1968)97–104;Bertrand(1985)469–81;Habicht(2006) 67–75,Oetjen(2010)237–54;Hatzopoulos(2014)99–120;Mari&Thornton(2016)139–95;and D’Agostini(2019)147–51);hiseconomicandpoliticalconcessionstotheAbaeans,Nisyriens,and Amphipolitans(Syll.³ 552, Syll.³ 572,and SEG 46(1996)716respectively);hisreligiousobservances inhiscorrespondencewiththeAtheniansatHephaistiaonLemnus(SEG 12399.Robert BE (1944) no.150;(1953)no.162;Fraser&McDonald(1952)81–3;cf.Gastaldi&Mari(2019)193–224),andwith thePanamarians(I.Stratonikeia 3)andtheChalcidians(I.Magnesia 47);hislettertoDiumendorsing the asylia ofCyzicus(SEG 48785;Hatzopoulos(1996)IIno.32,whodatesitto180 , contra Rigsby (1996)342whodatestheasyliaofCyzicusto c.200 );andhisfulfilmentofthedemandsofhis Macedoniancitizen-soldiersatEviestes(Hatzopoulos(1996)II41–2,no.17)andRhodes(Meadows

Hatzopoulos’ MacedonianInstitutionsundertheKings (1996)remainsareliable collectionofknowninscriptionsfortheMacedoniankings,includingthosefor PhilipV,andLeBohec(1996)helpfullysuppliesasurveyoftheinscriptions specificallypertainingtoPhilip.²⁸ Thesestudieshavealsobeensupplementedin recentyearsbyaseriesofarticlesbyHatzopoulosonmilitaryregulations, decision-makingvocabulary,theephebiclawatAmphipolis,ManuelaMarion localandnationalcultsinMacedonianroyallettersand diagrammata,city institutionsofpre-RomanMacedonia,andAntigonidchanceryactivity,and D’AgostinionPhilip’smilitarycode.²⁹ Suchanalyseshaveprovenfruitfulin outliningtheintricaciesoftheHellenisticMacedonianmonarchicsystem,the relationshipsbetweenthekingandassociatedcitiesandpeople,andhaveultimatelyshownPhiliptobeazealousandorganizedadministratorlookingtosecurea stableandprosperousfutureforhiskingdom.³⁰

AccompanyingthisgrowingcollectionofepigraphicmaterialonPhilipVisa sizeablehoardofsilverandbronzecoinage,showingapreferredconnectionwith AthenaAlcidemus,Zeus,andPerseusamongotherdeities,heroes,andimages, andassociatedscholarship.ThemostcomprehensivestudiesofPhilip’scoinage remainthosebyMamrothinthe1930s,althoughBurrer ’s2009studyoffersa moredetailedanalysisanddiestudyofPhilip’ssilvertetradrachms.Kleuhasalso morerecentlyreassessedtheimageryandsignificanceofthecoinhoardfoundat Selciin1880forPhilip’sactivitiesinLissusandScodra,D’Agostinihasdiscussed Philip’scelebrationofhisvictoryatThermumin218 withbronzecoinage,and Kremydihasinvestigatedthemintingofnon-regal, ‘autonomous’ coinagebythe Macedonians,Botteatai,andAmphaxiansinthereignsofPhilipVandPerseus.³¹ (1996)251–65).Thesurviving diagrammata revealconcernformilitaryregulations(Hatzopoulos (2001)151–3,nos.1.1and1.2;(1996)II153–65,nos.2.1,2.2,3;and(2016a)203–16;and D’Agostini(2019)48–55),fortheregistrationofathletesincompetitionsatgymnasia(Hatzopoulos (1996)II40–1,no.16.),forthepropertreatmentofreligiouspropertyatThessalonica(Hatzopoulos (1996)II39–40,no.15),andforthepreservationoftraditioninrequiringtheHuntersofHeracles Cynagidastoweartraditionalattire(SEG 56625).FortheidentificationofPolycratiaasPhilip’ squeen, see I.Stratonikeia 3;Cousin, BCH 28(1904)345–6,no.1;Holleaux, BCH 28(1904)354–6,no.1; BE (1906)48; BE (1952)3;andD’Agostini(2022)45–64fordiscussion.Notealsoanewassessmentof Philip’sdedicationatLindosfollowingasuccessfulattackontheDardanians(andperhapsMaedians) recordedintheLindianChronicle(Blinkenberg(1941)no.42,ll.127–131;Higbie(2003)no.42,ll. 127–131)byIliev(2021)74–82.

²⁸ ArgyroTataki’ s MacedoniansAbroad (1998)alsooffersavaluablecontributiontothelimited prosopographicalworkonMacedonia.

²⁹ SeeHatzopoulos(2000)825–40;(2001);(2009)47–55;(2013)61–70;(2014)99–120;(2015–16) 145–71;(2016a)203–13;(2016b);Mari(1999)627–49;(2006)209–25;(2008)219–66;(2017)345–64, and(2018)283–311,andD’Agostini(2019)147–56.

³⁰ Bertrand(1985)469–82,O’Neil(2000)424–31,andMa(2002)115–22and(2003)177–95have, forinstance,usedepigraphicevidenceconcerningdiplomaticaffairstoexploretherelationship betweentheHellenistickingsandtheGreekcities,andofferedagreaterunderstandingoftheprocesses involvedintheseinteractionsandtheirnegotiatorynature.

³¹Mamroth(1930)277–303and(1935)219–51;Burrer(2009)1–10;Kleu(2015)63–8;Kremydi (2018);andD’Agostini(2019)87–91,and figs.3–5.ForearlierdiscussionsoftheSelcicoinhoard,see Evans(1880)269–80;May(1946)54n.36;Hammond(1968)18,(1988b)399,409;andEckstein(2008)

ForapreliminaryinvestigationofthedifferingpictureofPhilipinboththe literaryandepigraphicrecords,Hatzopoulos’ 2014articleoffersanexcellent beginningandhighlightsastrikingdisparityofpresentationinthetwotypesof sources.D’Agostini’s2019analysisofPhilip’searlyyearsalsooffersthe first synthesisofthedocumentaryevidenceintoacoherentnarrativewhilecontesting historiographicalclaims.

TheStateoftheField:PhilipV

Foroverhalfacentury,Walbank’smonograph PhilipVofMacedon (1940and revisedin1960)hasbeenthemostcomprehensiveandinfluentialhistoricalstudy oftheMacedonianking.Fordecadesafterthisground-breakingtreatise,Philip Vreceivedonlycursoryattentionwithinbroaderhistoricalworksfocusedonthe riseofRomeandRomanimperialism,ormorenarrowlyinarticlesdealingwith specificquestionsofchronologyandforeignanddomesticpolicy.³²Thislimited attentionwasinpartduetothefactthattheAntigonidmonarchshaveconsistentlybeenovershadowedbythestudyoftheirpredecessors(PhilipIIand AlexandertheGreat)andtheotherHellenistickingdoms(thePtolemies, Seleucids,andAttalids),aconsequenceofthescarcityofsurvivingsourcematerial pertainingtothemandaprevailingperceptionoftheirinsignificance.Whilethe AntigonidswerekeyplayersintheeasternMediterraneanfromthefourthto secondcenturies andconsideredoneofthekeyimperialstructuresofthe Hellenisticagebyancientsourcesatthetime(e.g.Plb.1.2;althoughcondemned andignoredbytheRomans),theyhaveoftenbeenconsideredlittledifferentin theirrulingstyleandimperialstrategiesfromtheArgeadsbymodernscholars, andtherefore,oflimitedinterest,particularlyinthefaceofthemoreobviously differentformsofkingshipseeninthePtolemaicandSeleucidmonarchicsystems. Thisattitude,however,obscurestheimpactandcomplexityofthisdynastyinthe contextoftheancientMediterraneanandassumesastaticnaturetoMacedonian rulership;itdeniestheserulersagency,intelligence,andinnovation;itignoresthe kingdom’scrucialroleinshapingthepost-Alexanderworld.

87n.38.ForthecelebrationofPhilip’svictoryatThermumincoinage,seealsoMamroth(1935)no.4; Head(1911)232–4;andWalbank(1940)42.SeealsoPanagopoulou(2021)foranewstudyofthe coinageoftheearlyAntigonids;Merker(1960)39–52forthecoinageofAntigonusGonatasand AntigonusDoson;Dahmen(2010)41–62andKremydi(2011)159-78forsurveysofcoinageinancient Macedonia;andProkopov(2012)forthesilvercoinageoftheMacedoniansbyregion.Seealsoanew projectbegunin2020,TheAntigonidCoinsOnline(<http://numismatics.org/agco/>).

³²ForchronologyseeBerthold(1975)150–63.Forforeignpolicyseee.g.Gruen(1973)123–36 discussingtheallegedalliancebetweenPhilipandRome;Fine(1936)99–104andOost(1959)158–64 forhispoliciesinIllyria;Errington(1971)336–54,Thompson(1971)615–20,Walbank(1993)1721–30 =(2002)127–36,Meadows(1996)251–65andEckstein(2005)228–42forhispoliciesintheAegean andCaria.Forhisdomesticpolicies,seeGruen(1974)221–46,Piejko(1983)225–6,andOetjen(2010) 237–54.