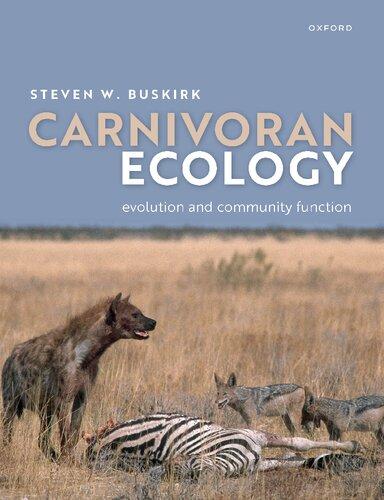

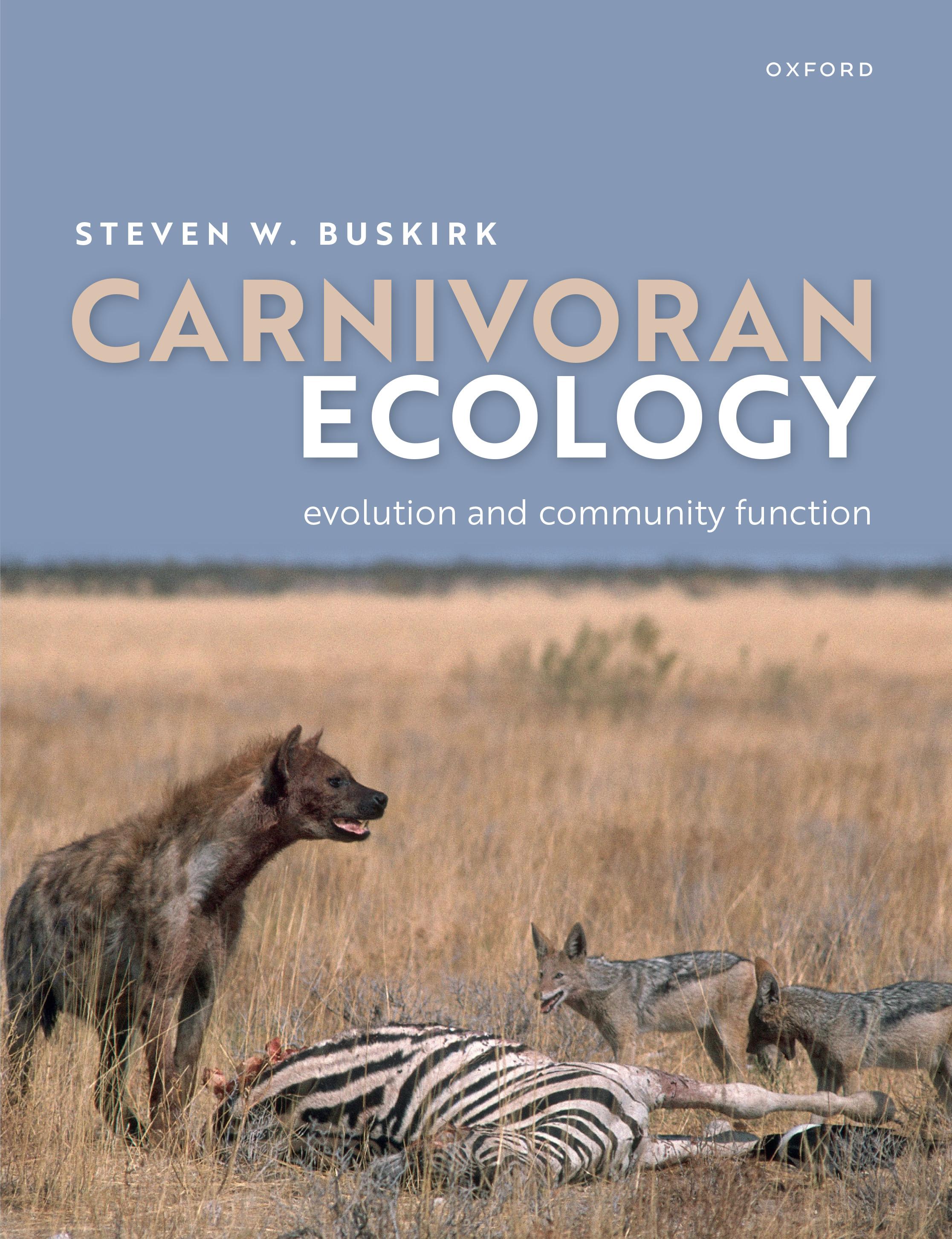

Function of Communities Steven W. Buskirk

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/carnivoran-ecology-the-evolution-and-function-of-com munities-steven-w-buskirk-2/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Carnivoran Ecology: The Evolution and Function of Communities Steven W. Buskirk

https://ebookmass.com/product/carnivoran-ecology-the-evolutionand-function-of-communities-steven-w-buskirk/

The Badgers of Wytham Woods: A Model for Behaviour, Ecology, and Evolution David W. Macdonald

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-badgers-of-wytham-woods-amodel-for-behaviour-ecology-and-evolution-david-w-macdonald/

A Primer of Life Histories: Ecology, Evolution, and Application Hutchings

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-primer-of-life-histories-ecologyevolution-and-application-hutchings/

Ecology of Coastal Marine Sediments: Form, Function, and Change in the Anthropocene Simon Thrush

https://ebookmass.com/product/ecology-of-coastal-marinesediments-form-function-and-change-in-the-anthropocene-simonthrush/

The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution and Ecology, 3rd Edition Douglas E. Facey

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-diversity-of-fishes-biologyevolution-and-ecology-3rd-edition-douglas-e-facey/

Adaptation and the Brain (Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution) Susan D. Healy

https://ebookmass.com/product/adaptation-and-the-brain-oxfordseries-in-ecology-and-evolution-susan-d-healy/

Marine Biology: - Function, Biodiversity, Ecology 1st Edition Jeffrey S. Levintons

https://ebookmass.com/product/marine-biology-functionbiodiversity-ecology-1st-edition-jeffrey-s-levintons/

Vertebrates comparative anatomy, function, evolution 8th Edition Kenneth V. Kardong

https://ebookmass.com/product/vertebrates-comparative-anatomyfunction-evolution-8th-edition-kenneth-v-kardong/

Conquering ACT Math and Science Steven W. Dulan

https://ebookmass.com/product/conquering-act-math-and-sciencesteven-w-dulan/

CarnivoranEcology

CarnivoranEcology TheEvolutionandFunctionof Communities

StevenW.Buskirk ProfessorEmeritus,UniversityofWyoming

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©StevenW.Buskirk2023

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2022944176

ISBN978–0–19–286324–9

ISBN978–0–19–286325–6(pbk.)

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192863249.001.0001

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

Thisbookarosefrommyseveraldecadesofinterest inandresearchoncarnivorans.Likemanyyoung peoplewithnaturalisttendencies,Iwasparticularlyintriguedbymyearlyencounterswithwild carnivorans—theirrarity,elusiveness,andimplicit threattomywell-being.Ivividlyrecallseeingmy firstbeartrackonasolobackpackingtripinthe SierraNevadaofCalifornia,followedbyasleeplessnightspentcontemplatingmyfate.Irecallthe horrorofmyoldersisterwhenIaskedhertostop ourparents’carsothatIcouldretrievearoad-killed domesticcatandadditsskulltomycollection.In thesummersofmycollegeyears,workingasatour guideinMountMcKinley(nowDenali)National Park,Alaska,Iobservedregularinteractionsinvolvingwolves,caribou,brownbears,moose,redfoxes, andotherspecies.Someoftheseobservationswere dramaticandphotogenic,butcuriousaswell.Why did150-kgbrownbearsinvestsomucheffortto capture200-ggroundsquirrels?Whydidwolves givebirthinthesamedensfordecadesonend, eventhoughtheywerewellknownandprone tohumandisturbance?Whywerecoyotesdeathly afraidofbeinganywherenearwolves,whilered foxesmerelystayedoutoftheirgrasp?

MyPhDresearchandsubsequentfaculty appointmentinZoologyandPhysiologyatthe UniversityofWyominggavemeopportunities topursuethesekindsofquestions.Whilemost carnivoranresearchofthattimegravitatedto intraspecificandpredator–preyinteractions, myinterestsrangedmorewidely.Myresearch addressedvariousmechanismsbywhichcarnivoransmightbelimited:thermalenergetics, allometry,toothmorphology,fastingendurance, geneticvariability,andinterspecificcompetition. Ilearnedthatpredator–preyinteractionswere

asmallpartofourgrowingunderstandingof whatlimitsthedistributionsandabundancesof carnivorans.

Duringthoseearlyyears,Idependedonthestandardacademicreferencesoftheday:journalarticles,monographs,bookchapters,theses,dissertations,andR.F.Ewer’s(1973) Thecarnivores.Ewer’s monographwasthedefinitivesourceforcarnivoranbiology—especiallypaleontologyandbehavior. Writingthecurrentaccountnearlyfiftyyearson, Ibenefittedfromawealthofhigh-qualitymaterial facilitatedbytherevolutioninpublishing—aproliferationofjournaltitles,manyofthemopenaccess, expandedopportunitiesforscientistsindevelopingcountriestopublishtheirwork,andmanymore womenworkingandpublishingasscientists.The periodsince2000hasofferedunprecedentedopportunitiestowriteabooksuchasthis,andthepandemicof2020–22gavemyisolationandfocusnew purpose.

Whatqualifiesmetowriteabookaboutallcarnivorans?Iamnotthemostprolificauthorofcarnivoranpapers,northeonewiththebroadestgeographicexperience.Othershavespentmoretime inthefield,oraremorequantitativethanI.However,myinterestsextendinmultipledirections, allofwhichrelatetohowcarnivoranssucceedor failinthewild.Iamasintriguedbyanswersto bigecologicalquestionsasbysolutionstospecific conservationproblems.Iamassatisfiedbyunderstandingofsomeecologicalpuzzleasbywatching alargecarnivorestalkanungulate.Iappreciatenew discoveriesinnaturalhistoryasmuchasIdostudiesoffunctionalgenomics.Ialsovaluethosewho studycarnivoransandsharetheirfindingswithscientistsandthepublic.Thisgroupoverlapsstrongly withthosecommittedtoassuringthepresenceand

importanceofcarnivoransinfuturecommunities. Thisbookisreallyabout,for,andtheresultof theworkofcarnivoranbiologists,conservationists, andnaturalists,bothprofessionalandamateur.It isabouttheirpassion.Lastofall,hopefullyitisa motivationforotherstofollowintheirtracks.

StevenW.Buskirk

ProfessorEmeritus,UniversityofWyoming December10,2022 SilverCity,NewMexico,US

Referencescited

Ewer,R.F.(1973). Thecarnivores.Ithaca:CornellUniversity Press.

Acknowledgments

Manypeoplesupportedandaidedmeinwriting thisbook.MywifeBethencouragedmeatevery stageandtoleratedmanyinterruptionstoourroutinesothatIcouldspendtimewriting.ClosecolleaguesDennisKnightandCarlosMartinezdelRio werereliablediscussantsandsourcesofencouragementearlyintheconceptionandearlywriting phases.HannahSeaseproducedallgraphicarts work,keepingpacewithmyrequeststhroughout hergraduatestudiesingraphicarts.

TheWilliamRobertsonCoeLibraryattheUniversityofWyomingprovidedoutstandingsupport,fillingscoresofrequestsformaterials,andtheJ.Cloyd MillerLibraryatWesternNewMexicoUniversity providedadditionalassistance.Myacademichome, theDepartmentofZoologyandPhysiologyatthe UniversityofWyoming,providedofficespaceand othersupportformostofdurationoftheproject.

Ibenefittedfromreviewsbyoverthirtyscientists,eightofthemcommissionedbyOxfordUniversityPress,andotherssolicitedbyme,who generouslyreviewedchaptersorshortersections: BenjaminAllen,RudyBoonstra,JeffBowman, JosephBump,EmilianoDonadio,JacobGoheen, HenryHarlow,DennisKnight,SergeLariviere, PaulLeberg,JasonLillegraven,CarlosMartinez delRio,SterlingMiller,RobertNaiman,Richard Ostfeld,JonathanPauli,JamesD.Rose,Oswald Schmitz,JohnSchoen,Qian-QuanSun,Blaire

VanValkenburgh,LarsWerdelin,andAndrzej Zalewski.Collectively,thereviewerscorrected errorsoffact,identifiedimportantomissions,providedmorepertinentormorerecentreferences, andimprovedtheorganizationandpresentation. Withouttheirhelptheprojectwouldnothavebeen possible.

Theillustrationsstrengthenthenarrative throughout,andsomeofthefinestartworkand photographywerecontributedgratisorlicensed atreducedrates.IparticularlythankJustinBinfet, DarinCroft,WaltonFord,StanGehrt,DonGutoski, EsperanzaIranzo,JeffreyKerby,JanetKessler, DéboraKloster,SusanMcConnell,ChrisMills, LarissaNituch,VelizarSimeonovski,Alejandro Travaini,JuanZanón,thePhilmontScoutRanch, andKasminGallery.AlthoughIhavetriedto selectphotostakenundernaturalconditions,I cannotassurethatnonewasstagedorinsomeway contrived.

ThestaffofOxfordPressweremostsupportiveandencouraging.IanSterlingwasimmediately receptivewhenIapproachedhimwithmyproposal,andconsistentlyimprovedmypresentation aswellasmyunderstandingsofhowthebookcould bemademostuseful.CharlieBathprovidedexcellentsuggestionsondraftchapters,andKatieLakina shepherdedtheprojectthroughtheeditorialand productionprocesses.

2.6.1Scansorialecomorph

2.6.2Dog-likeecomorph

2.6.3Cat-likeecomorph

2.6.4Scavengerecomorph

2.6.5Semi-fossorialecomorph

3.3Earlycarnivorans

4.1.1Solublecarbohydrates

4.2Dietaryrequirements

4.8.1Generalpatterns

5.1.2Chemosense

5.1.3Hearing

5.1.4Electromagneticradiation

5.1.5Geomagnetic

5.2Brainmorphology

5.2.1Brainsize

5.2.2Brainregionalsize

6.3.3Trophictransmissionandpreybehaviors

6.4Scavengingandaccesstocarrion

6.5Directeffectsonplantlifecycles

7.2.2Interferencecompetition

7.2.3Influencesoninterference

7.2.4Mesopredatorrelease

7.2.5Demographiceffectsofinterference

7.2.6Coexistenceorinterference?

7.2.7Abioticfactorsandinterference

7.2.8Humaninfluenceoninterference

7.3Domesticdogsascompetitorswithwildcarnivorans

7.4Carnivorans:apex,meso-,andother

8.1Whoeatswhom?

8.2Docarnivoranslimitpreyabundance?

8.2.1Bottom-upvs.top-downeffectsonherbivores

8.3Trophicdiversityandlimitingeffects

8.4Howherbivoresavoidpredation

8.4.1Antipredatorstructures

8.4.2Antipredatorchemicals

8.4.3Inducedpredatordefenses

8.5Physiologicalanddemographicresponsestorisk

8.6Carnivoransandpreypopulationcycles

8.7“Prudent”and“wasteful”predators

8.8Apparentcompetition

9.2Trophiccascades

Introductionto CarnivoranEcology

OrderCarnivorarepresentsoneofthemostspeciesrich,phenotypicallydiverse,widelydistributed, andecologicallyinfluentialmammalianlineages. Itsextantmembersliveonallcontinentsandin alloceansandrangefromvole-sized(c.30g) tolargerthanarhinoceros(c.4,000kg).They eatdiversefoodsincludingleaves,fruits,insects, honey,marineinvertebrates,andmammalslarger thanthemselves.Somespecieslivebelowground forweeksatatime,afewlivemostlyinthe forestcanopy,andothersliveatseaformonths onend.Manyarewildernessdwellers,waryof humansandtheiractivities,whilesomenondomesticspeciesthriveinmajorcities,largely dependentonhumansforfood,shelter,orprotectionfromlarger,wildercarnivorans.NoothermammalianorderapproachesCarnivorainthebreadth ofadaptivesuitesshownandecologicalniches occupied.

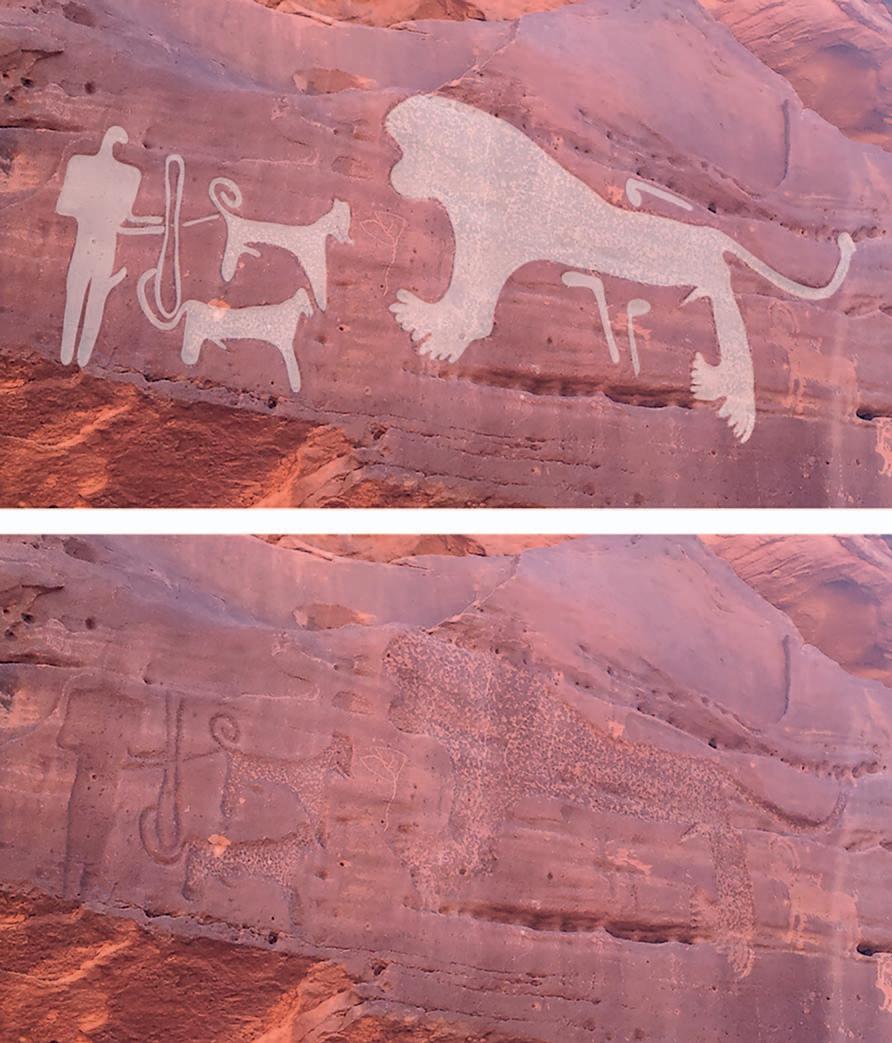

Humanshavealwaysbeenkeenlyinterestedin carnivorans.Ourhomininancestorswerepreyed onbycarnivoransandcompetedwiththemfor food.Bothspecieshuntedthesamepreyanddrove eachotherawayfrompreycarcasses(Figure 1.1) (Espigares etal.,2013).Paleolithichumansconvertedapotentialcompetitor,thewolf,toapartner. Theresultantdogwasthefirstdomesticatedanimal, andbecameessentialtohumanlives,providinga foodsource,vigilanceagainstintruders,transport ofpossessions,andassistanceinhuntingandherding(Figure 1.2).Dogsbecamesoimportanttoearly humansthattheyarecreditedwithshapinghuman evolutionasmuchashumansshapedtheirs(Pierotti andFogg,2017).

Thelife-or-deathnatureofpredationelicitsstrong humanemotions—eitherthepredatoreatsand lives,orthepreyescapesandsurvives.These

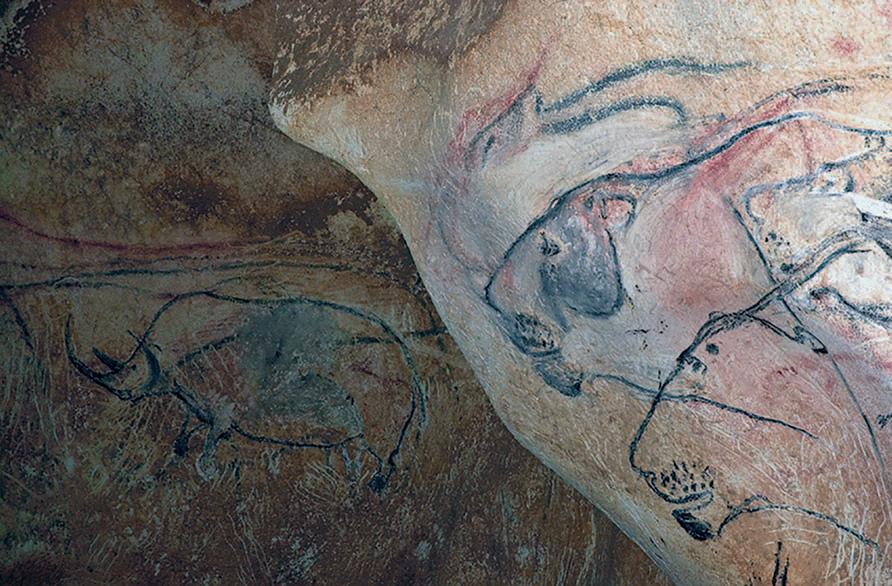

emotionsarestrongerwhenweimagineourselves oranimalsweownasprey.Asaresult,wehavelong imbuedcarnivoranswithspiritualpowerstomatch theirimpressivephysicalabilities,andourancestorsrepresentedcarnivoransinsomeoftheearliest figurativeart(Figure 1.3)(HartandSussman,2008; Azéma,2015).Today,wecontinuetousecarnivoranstosymbolizewildness,ferocity,andindependenceinvisualandliteraryarts.Everypocketand foldofmosthumancultures—languages,parables, spiritualbeliefs,andsymbols—isrichwithcarnivoranreferences.

1.1 “Carnivoran”vs.“carnivorous”

Theterms“mammalianpredator,”“mammalian carnivore,”and“carnivoran”arenotpreciselysynonymous.Predatorsareanimalsthatkillandconsumemulticellularanimals(Taylor,1984),whether oneatatime,orfilteredfromwaterbythethousands.Eagles,dragonflies,andbluewhalesare predators.Bycontrast,acarnivoreconsumesthe fleshofanimals,whetheritkillsorscavengesit;vultures,snakes,andVenusflytrapsarecarnivores and carnivorous.Carnivorans,thesubjectofthisbook, areexclusivelymammalsinOrderCarnivora—a branchofthetreeoflife.Speciesintheorder maypursueandkillvertebrates,eattermitesexcavatedfromsoil,orsubsistentirelyonplantparts (Figure 1.4).“Hypercarnivore”sometimesindicates aspecieswithadietexceedingsomethresholdlevel ofvertebrateprey,typicallykilledratherthanscavenged.Mostmembersofthecatfamily,theFelidae, areconsideredhypercarnivores.Otherterms,such as“mesopredator,”“apexpredator,”and“keystone predator,”haveimprecisemeaningsthatIparseas theyariseinthebook.

Figure1.1 Thefirstcontactbetweenhumansandthesaber-toothed Smilodon inAmerica,interpretedbyVelizarSimeonovski.Carnivoranshave beencompetitorswithandpotentialpredatorsofhomininsfrombeforewebecamehumansthroughtotoday. Painting:©VelizarSimeonovski.

Figure1.2 Lions(right)depictedonthewallsofSalleduFondinChauvet-Pontd’ArcCave,France,datingto32,000–30,000yearsago.Thelions appeartobewatchingarhinocerosonadistantpanel.Carnivoransweresubjectsofsomeoftheearliestfigurativeart.Verticalscratchesinthe lowerrightandontherhinocerospaintingweremadebycavebearstrappedindeepchambers.

Photo:J.Clottesin Azéma(2015),CC4.0.

Asisoftenthecaseinbiology,thedefiningtraits oftheCarnivora—thetraitsheldbyallmembers ofthelineage,bothlivingandextinct—aredifficult tostatewithoutqualification.Traditionally,biologistshavecitedthepresenceofcheekteeththathave shearingfunctions,comprisingtheupperfourth premolar(P4)andlowerfirstmolar(M1).Allliving carnivoranshaveancestorswiththistrait.However, livinggenets,bears,andsealshavesecondarilylost theshearingfunctionofthoseteeth,andatleast onespecieshaslostthoseteethcompletely.Some prehistoriclinagesofothercarnivorousmammals hadshearingcheekteeth,buttheyoccupiedother positionsinthetoothrow,forexampleM1 andM2. Theywerenothomologoustomoderncarnassials, andthelineagesthatexhibitedthemhavenoliving descendants.Thefusedscaphoidandlunatecarpal bones(thescapholunate)aresometimesregardedas

definingthegroup,becauseallmodernspecieshave thattrait,butsomeearlycarnivoransdidnot.

Predatoryplacentalmammals—thosethatprimarilykillotheranimalsforfood—occurinseveral orders,includingshrewsandmoles(OrderSoricomorpha),bats(Chiroptera),whales(Cetacea),pangolins(Pholidota),andhairyanteaters(Pilosa).If webroadenourframeofreferencetoincludemarsupialpredators,severaladditionalordersmust beincludedasmammaliancarnivores.Evensome obligateherbivores,amongthemungulatesand rodents,preyonorscavengevertebratesopportunistically(Boonstra etal.,1990; Dudley etal.,2016). Finally,manyextinctnon-carnivoranlineageswere atleastpartiallycarnivorous.Clearly,OrderCarnivoraisnotuniqueamongmammalsinkillingand eatingvertebrates.Thisbookisaboutamammalian lineage,notaforagingstyleortrophicniche.

Figure1.3 RockartinnorthwesternSaudiArabiashowingdogsresemblingmodernCanaandogsassistingwithlionhunting.Variousglyphs fromthissiteincludetheearliestdepictionsofdogsonleashes,12,000–10,000yearsold.Theupperimageisshadedtoshowreliefthatisless visibleinthelower,unalteredimage.

Photo:Guagninetal.(2018,Figure10)bypermission.

Figure1.4 Venndiagramofthe relationshipsbetweencarnivory,herbivory, andOrderCarnivora.Herbivorousmammals overlapwiththeCarnivora,andthe Carnivoraoverlapwithcarnivorous mammals.Elephantsareherbivorous non-carnivoranmammals.Thegiantpanda isanherbivorouscarnivoran.Thebrown bearisanomnivorouscarnivoran,neither fullyherbivorousnorcarnivorous.Thetigeris acarnivorouscarnivoran,andthekiller whaleisacarnivorousnon-carnivoran mammal.InthisbookIuse“carnivorous”to denotediet,and“carnivoran”todenote phylogeny—inclusioninOrderCarnivora.

1.2 Thecarnivorans—whoandwhere?

Theapproximately287extantspeciesofcarnivoransareorganizedintofifteencurrentlyrecognized families(AppendixI)andoccuronallcontinents,if weincludesealsthathauloutonAntarcticbeaches. Thesenumberschangeaswelearnmoreabout howmammallineagesarerelated.Forexample,the neotropicalolinguitorecentlyhasbeenidentifiedas distinctfromotherolingos,andtheAfricangolden wolfwasjudgedaseparatespeciesfromthegolden jackal,(Gaubert etal.,2012; Helgen etal.,2013).On theotherhand,thelong-recognizedredwolfofeasternNorthAmericaisnowregardedasanancient hybridofthewolfandthecoyote,withuncertain endangeredspeciesstatus(vonHoldt etal.,2016,but see Hohenlohe etal.,2017).Attheleveloftaxonomicfamilies,theskunksandstinkbadgerswere groupedwithweaselsandottersintheMustelidae beforeFamilyMephitidaewasrecognizedaswarrantingrecognition(DragooandHoneycutt,1999). Witheachsuchdiscovery,ourknowledgeofcarnivoranclassificationbecomesmorereflectiveof evolutionaryhistory,asrevealedthroughgenetic andmorphologicalstudies.

Carnivoranspeciesaredistributedunevenly acrosslineagesandcontinents.FamilyMustelidaeholdssixtyspecies,whereastheNandiniidae, Ailuridae,andOdobenidaeholdasinglespecies each.TheFelidae,Canidae,andMustelidaeare

nearlycosmopolitan,foundonallcontinentsexcept AntarcticaandAustraliabeforehumanstransportedthem.Ontheotherhand,theeightspecies ofEupleridaeoccuronlyonMadagascarIsland, theircommonancestorhavingraftedtherefrom theAfricanmainlandaround20millionyearsago (Ma).Thethirty-threeextantspeciesofseals,sea lions,andwalrusmakeupthepinniped(earfoot) group—alineagecomprisingtwoorthreefamilies thatarosefromasingleaquaticancestor.“Fissiped” (splitfoot),ontheotherhand,denotestheremaining,mostlyterrestrial,non-pinnipedcarnivorans.

1.3 Thegrowthofknowledge

Before1900,understandingofcarnivoranecology (asopposedtonaturalhistory)waslimited,often basedonloreandconjecture.Muchofourknowledgeoftheirgenetics,behavior,andreproduction atthattimeresultedfromobservingdomesticcats, ferrets,anddogs,andfarmedminksandfoxes (Figure 1.5).Verylittlescientificknowledgeabout wildcarnivoransexisted,andmostinterestcenteredonthevalueoftheirfursorotherbody partsandthethreattheyposedtoagriculture.They weredifficulttostudydirectlybecauseoftheirlow densities,elusivebehaviors,andconstantpersecutionnearhumans.Wellintothetwentiethcentury, theleadingecologicalquestionsaboutcarnivorans

dealtwithhowmanyungulates,waterfowl,and othervaluedvertebratestheykilledandhowtomitigatethoselosses(Leopold,1933).Inthelatetwentiethcentury,however,perspectivesshifted,tools improved,andecologicalresearchonthisgroup surged.Thenumberofscientificjournalarticles indexedbyWebofSciencewith“Carnivora”asa topicincreasedbyafactorofelevenfrom1992to 2016,comparedwithafactoroffourfor“mammal”andsixfor“Mammalia.”Newunderstandings ofcarnivoranbiology,especiallyecology,beganto unfoldinthe1960s,whencarnivoransgainedsignificanceinconservationissues,eitherasthreatened taxaorasagentsofendangermentofothertaxa orcommunities.Forexample,theseverecontractionindistributionandabundanceofthebrown bearinthecontiguousUnitedStatesfrom1850 to1950resultedingreatlyexpandedresearchin bearbiology,broadlycast.Of159scientificjournalarticleswiththetopics“grizzlybear + Yellowstone”indexedbyWebofScience,allbuttwowere publishedsubsequenttotheinitial1975listingof theYellowstonepopulationundertheEndangered SpeciesAct.Similarly,noarticlesindexedbyWeb ofSciencedealtwiththepopulationgeneticsofthe cheetahbeforethediscoveryby O’Brienandcolleagues(1983) thatcheetahsexhibitedlowgenetic variability.Thisfindinghadsuchstrongconservationimplicationsthat153subsequentarticles

reportedongenetictraitsofcheetahsrelatedto evolutionaryorecologicalprocesses.Geneticdepletioninothercarnivoranspeciesbecamearesearch focusaswell.

TheAmericanminkisanexampleofacarnivoranthathasstimulatedresearchasaresult ofthegreatecologicalharmitcauses.Introduced toEuropeandSouthAmericaduringthetwentiethcenturyforfurproduction,ittodayposes threatsonbothcontinents,spurringintensivestudy (BonesiandPalazon,2007; Crego etal.,2016).Over thepasttwenty-fiveyears,publishedstudieson theecologyofinvasiveAmericanminksoutside ofNorthAmericahavegreatlyoutnumberedthose conductedwithinthespecies’nativerange.

Thisexpansionofknowledgereflectsthat humansneedtoknowmuchmoreaboutcarnivoranecologythantheydidseventyyearsago. Forexample,publichealthplannersnowmust considerwhetherthemostrapidlyemerging infectiousdiseasesofhumansareinfluencedby thediversityandabundanceofwildcarnivorans (Section11.3.1)(Levi etal.,2012, Hofmeester etal., 2017).Thecurrentincidenceandseverityofsuch debilitatingzoonosesasavianandswineinfluenza, Lymedisease,andtick-borneencephalitismay bemediatedbythepresenceandabundanceof predators—manyofthemcarnivorans—thatkill intermediateoralternatehosts(Thulin etal.,2015).

Figure1.5 Farmedblack-phasered foxesatFrommFoxFarm,Wisconsin,US, intheearlytwentiethcentury.Knowledge ofcarnivoranreproductiveandnutritional physiologyduringthateracamelargely fromobservingdomesticatedandfarmed animals.

Photo:FrommHistoricalSociety.

EventheviralpandemicCOVID-19hasbeenlinked totransmissionoftheSARS-CoV-2virusamong variouswildanddomesticmammals—particularly carnivorans—andhumans.Thecarnivoransinclude domesticdogsandcats,captivetigers,andAmericanminks(VinodhKumar etal.,2020; Hammer etal.,2021).

Atthesametime,carnivoransarecredited withperformingvaluableecologicalservicesnot understooddecadesago.InChapter 6 Ishow thatbearsarerecognizedfortransportingmarinederivednutrientsinsalmoncarcassesfromspawningstreamstoneighboringforestsalongtheNorth PacificRim.Leopardsandpumasprotectsome plantsfromoverusebyherbivores.Fruit-eatingcarnivoranstransportseedsawayfromparentplants, insomecasesmoreeffectivelythanbirdsorherbivorousmammals.LeopardsinIndiaevenreceive creditforreducinghumanfatalitiesinflictedbyferal dogs,althoughleopardsthemselveskillasmall numberofhumans.Eachofthesefunctionsand serviceshasbeenrecognizedorbetterunderstood recently,contributingtoamuchricherandmore nuancedpictureofhowcarnivoransaffecthuman livesandwell-being.

1.4 Purposeandorganization ofthebook

Thisbookisintendedasatextforacollegecourse incommunityecologyorpredationecology,and asareferenceforstudents(academicorotherwise) ofecologywhohavesomebackgroundinbiologicalconceptsandvocabulary.Itemphasizesdocumented,mechanisticexplanationsfortheecologyof carnivoransandspeciestheyinteractwith.Importantly,Idonotreviewallbiologicalknowledgethat appliestotheCarnivora—onlythoseaspectsthat setcarnivoransapart;manyaspectsofcarnivoran biologyresemblethoseofothermammalianorders. Forexample,thevibrissaeofcarnivoransarewell developedandimportantfortactilesensation,but theprimaryresearchmodelforthisorganhasbeen thelaboratoryrat,notacarnivoran.Ananalogous situationexistsforgutfermentation—itisrareinthe Carnivoraandisbetterunderstoodfromstudiesof othermammalianorders.Tohelpwithvocabulary issues,Iprovideaglossaryoftechnicalterms.

Becauseofmyfocusoncommunityecology,the readerwillfindonlypassingmentionofsometopicscentraltocarnivoranbiologyinthepast.These includeintraspecificbehavioralinteractions:sociality,matingsystems,parentalcare,andterritoriality. Thesetopicswereattheforefrontofcarnivoranecologyduringthe1970s—theheydayofinterestinkin selection—buttheyareperipheraltocommunity interactions.Ecologicalsystemsarecomplex,with indistinctboundariesbetweencomponents.Predationrelatestocompetition,andcompetitionaffects populationgrowth.Populationdensityaffectsdispersal,which,inturn,drivescolonizationandbiogeography.Thiscomplexitymakesecologydifficult tocompartmentalize,andmychapterorganizationrequiresthereadertonavigatespecifictopics viatheindex,inadditiontothetableofcontents. Forexample,thereaderinterestedinpopulation biologywillfindcarnivoran-inducedchangesin preypopulationscoveredinChapter 8,butthe demographyofcarnivoransthemselvesistreatedin Chapter 10.Dentaladaptationsaremostlycovered inChapter 2,butsomeotheraspectsofdigestive morphologyfitbetterinChapter 4,thechapteron physiology.Theresponsesofpreyspeciestocarnivoranscanbebehavioral,physiological,demographic,orhaveuncertainmechanisms,andthese processesarecoveredinvarioussections,best locatedviatheindex.Chemicaldefensesagainst carnivoransbypreyandothercarnivorans,andby plantsagainstherbivores,aswellasdetoxification ofvenomsbycarnivorans,areeachtreatedseparately,insectionsbestlocatedintheindex.Habitat ecologyisatraditionalandhighlydiffusetopicthat permeateswildlifebiology.Scarcelyasectionofthis bookdoesnothavehabitataspects.However,no aspectofcarnivoranhabitatecologyseemsunique totheorder,soIfolddiscussionsofhabitatinwith others.

Thisaccountisbasedalmostentirelyonthepeerreviewedscientificliterature.Iusebothprimary andsecondarysources,relyingoncommunity-level analyses,meta-analyses,orreviewswherepossible. Ihavetriedtobecomparativethroughout,contrastingcarnivoranfamilieswitheachotherandcarnivoranswithothervertebratecarnivores,includingmarsupials,reptiles,andbirds.Ihavetended toprefermechanisticallybasedstudiestothose

basedonlyoncorrelativeresultsormodelingand havefavoredwidelyaccessiblepublicationstomore obscureones.

WhileIhavetriedtoenhancethegeographicand taxonomicdiversityofthecasestudiesthatIcited, Irecognizethattheliteratureisbiasedtowardstudiesfromdevelopedcountriesandonhigh-profile orendangeredcarnivorans.Therefore,mypresentationnodoubtincludesculturalbiasesthataffect thegeneralityofmyconclusions.Insomecases whereexamplessupportageneralizationandmultiplepublishedexamplesillustratethepoint,Ihave tendedtociteastudyfromaregionorecosystemthatislesswellrepresentedintheliterature, ratherthananequallyillustrativestudyfromNorth AmericaorwesternEurope.

Someunifyingthemesconnectthevariousfacets ofcarnivoranecology,andIreturntothemfrequently.Thesefactorsexplainmuchofthegreat diversityofformandfunctionacrosstheCarnivora, aswellasmanyofthedifferencesbetweencarnivoransandothermammalianorders.Themost importantarebodysize,metabolicrate,andtrophic level.Allometryisthestudyofbodysizeandits consequences,andthereaderwillnotetherecurringimportanceofallometryinmanyprocessesat physiologicalandcommunitylevels(Calder,1984). Metabolicrateisafunctionofbodysize,body temperature,andmitochondrialdensity,andhas strongexplanatorypowerincarnivoranecology. Trophicleveliscorrelatedwiththesefactors;carnivoransthateatlargemammalianpreyexemplify theconstraintsimposedandbenefitsconferredby highmetabolicrateandlargebodies—highforaging costsandmaintenancecosts—butfoodavailability thatismoreseasonallyconsistentthanforherbivoresorpredatorsofectotherms.Bywatchingfor therecurringmentionofbodysize,metabolicrate, andtrophiclevel,thereadercanappreciatehow muchcarnivorandiversityarisesfromonlyafew principles.

1.5 Contextincarnivoranecology

WhileIsearchforpatternincarnivoranecology, Imakescarcelyageneralizationaboutthisgroup withoutaqualificationorcaveat.Contingencies

havecausedthegrouptoradiateintoanastonishingrangeofphenotypes.Trophicnichedetermines dentition,digestiveprocess,andgutpassage.Sizeof preyspeciesaffectshuntingbehavior,frequencyof predationevents,andcompetitiveinteractionswith scavengers.Contextliesattheintellectualcoreof carnivoranecology,andIhaveembraceditfully. Conservationalsoisanappliedarenainwhich contextisall-important.Carnivoransarewidely regardedasoneofthemostthreatenedmammalian lineages,withseverechallengestospecies,subspecies,andpopulationsacrossEarth.Ontheother hand,carnivoransalsocauseorexacerbateconservationproblemsforotherspeciesthatarerare orthreatened.Furthercomplicatingthepicture, humanshavebenefitedsomecarnivoranspecies(or stoppedpersecutingthem),andothersarereoccupyingtheirformergeographicrangeswithorwithouthumanassistance.Carnivoreconservationdoes notmerelyrepresentasadlistofdecline,dysfunction,anddisappearance,butexamples—admittedly anomalous—ofrestorationandindependentrecovery.Ecologicalandsocio-economiccontextdeterminehowcarnivoransarefaringinthemodern world.Alltold,thebiologyoftheCarnivoraisan extraordinarilyrichsubdiscipline,fullofpattern, nuance,contingency,andrelevancetohumancultureandlivelihoods.

1.6 Nomenclature

Forthecurrentscientificnomenclatureofcarnivorans,IhavemodifiedWilsonandReeder(2005) toreflectrecenttaxonomicrevisions(AppendixI). Commonnamesaremoreproblematic,becauseall arelocalorregional,andusingonerequiresselectingfromamongthoseusedbyvariousindigenous groupsorcolonizingnations,orthenativetongue oftheoriginalnamingauthority.BecauseIwritein English,Idefaulttomylanguage,butIhavetried tousethecommonnameappliedmostgeographicallybroadlywherethespeciesoccurs.Forexample, Pumaconcolor occursfromPatagonia,SouthAmericatoYukonTerritory,NorthAmerica,withmany locallyusednamesoveritsrange.However,the commonnameappliedovermostofthegeographic rangeis“puma,”whichIusehere.

References

Azéma,M.(2015)“Animationandgraphicnarrationinthe Aurignacian,” Palethnology,7,pp.256–79.

Bonesi,L.andPalazon,S.(2007)“TheAmericanminkin Europe:status,impacts,andcontrol,” BiologicalConservation,134,pp.470–83.

Boonstra,R.,Krebs,C.J.andKanter,M.(1990)“Arctic groundsquirrelpredationoncollaredlemmings,” CanadianJournalofZoology,68,pp.757–60.

Calder,W.A.III.(1984). Size,functionandlifehistory.Cambridge:HarvardUniversityPress.

Crego,R.D.,Jiménez,J.E.andRozzi,R.(2016)“Asynergistictrioofinvasivemammals?Facilitativeinteractionsamongbeavers,muskrats,andminkatthe southernendoftheAmericas,” BiologicalInvasions,18, pp.1923–38.

Dragoo,J.W.andHoneycutt,R.L.(1999)“Systematicsof mustelid-likecarnivores,” JournalofMammalogy,78,pp. 426–43.

Dudley,J.P. etal.(2016)“Carnivoryinthecommonhippopotamus Hippopotamusamphibius:implicationsfor theecologyandepidemiologyofanthraxinAfrican landscapes,” MammalReview,46,pp.191–203.

Espigares,M.P. etal.(2013)“Homo vs. Pachycrocuta:earliestevidenceofcompetitionforanelephantcarcass betweenscavengersatFuenteNueva-3(Orce,Spain),” QuaternaryInternational,295,pp.113–25.

Gaubert,P. etal.(2012)“RevivingtheAfricanwolf Canis lupuslupaster inNorthandWestAfrica:amitochondrial lineagerangingmorethan6,000kmwide,” PLoSONE, 7,p.e42740.

Guagnin,M.,Perri,A.R.andPetraglia,M.D.(2018)“PreNeolithicevidencefordog-assistedhuntingstrategies inArabia,” JournalofAnthropologicalArchaeology,49,pp. 225–36.

Hammer,A.S. etal.(2021)“SARS-CoV-2transmission betweenmink(Neovisonvison)andhumans,Denmark,” EmergingInfectiousDiseases,27,pp.547–51.

Hart,D.andSussman,R.W.(2008) Manthehunted:primates, predators,andhumanevolution.Expandededn.Boulder: WestviewPress.

Helgen,K.M. etal.(2013)“Taxonomicrevisionoftheolingos(Bassaricyon),withdescriptionofanewspecies,the olinguito,”ZooKeys,324,pp.1–83.

Hofmeester,T.R.,Jansen,P.A.,Wijnen,H.J.,Coipan,E.C., Fonville,M.,Prins,H.H.T.,Sprong,H.,andvanWieren, S.E.2017.Cascadingeffectsofpredatoractivityontickbornediseaserisk. ProceedingsoftheRoyalSocietyB 284:20170453.

Hohenlohe,P.A. etal.(2017)“Commenton‘Wholegenome sequenceanalysisshowstwoendemicspeciesofNorth Americanwolfareadmixturesofthecoyoteandgray wolf’,” ScienceAdvances,3,p.e1602250.

Leopold,A.(1933) Gamemanagement.NewYork:Charles Scribner’sSons.

Levi,T. etal. (2012)“Deer,predators,andtheemergence ofLymedisease,” ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyof SciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica,109,pp.10942–7.

O’Brien,S.J. etal. (1983)“Thecheetahisdepauperatein geneticvariation,” Science,221,pp.459–62.

Pierotti,R.andFogg,B.R.(2017) Thefirstdomestication:how wolvesandhumanscoevolved.NewHaven:YaleUniversityPress.

Taylor,R.J.(1984) Predation.NewYork:Chapmanand Hall.

Thulin,C.-G.,Malmsten,J.andEricsson,G.(2015)“OpportunitiesandchallengeswithgrowingwildlifepopulationsandzoonoticdiseasesinSweden,” EuropeanJournalofWildlifeResearch,61,pp.649–56.

VinodhKumar,O.R. etal.(2020)“SARS-CoV-2(COVID19):zoonoticoriginandsusceptibilityofdomesticand wildanimals,” JournalofPureandAppliedMicrobiology, 14,pp.741–7.

VonHoldt,B.M. etal.(2016)“Whole-genomesequence analysisshowsthattwoendemicspeciesofNorth Americanwolfareadmixturesofthecoyoteandgray wolf,” ScienceAdvances,2,p.e1501714.

Functionalmorphology

Functionalmorphologyconsidershoworgan-and tissue-levelstructureandcolorationarethebasis offunction.Atsmallerphysicalscales,“histology,”“cellstructure,”and“molecularbiology”are morecommonterms.HereIconsiderstructurewith directecologicalrelevance,importantforlocomotion,preyhandling,crypsis,communication,and reproduction.“Ecomorphology”isasynonym,and livingandfossilcarnivoransarewellrepresented assubjects.Thecarnivoran-specificliteratureon thissubjectfocusesmostlyonthreemorphological regions:theskull,theforelimbs,andthehindlimbs. Theskullissignificantbecauseofthegreatrange offunctionsitperformsandthespatialtrade-offs betweenthem.Theforelimbisimportantbecause itsstructurediffersacrosslocomotorandforaging styles:swimming,diggingthroughsoil,sprinting, andclimbingallleavestrongadaptivesignatures. Toalesserextent,thehindlimbalsoreflectsadaptationstolocomotormodes.

2.1 Theskull

Theskullisthebonystructurewiththemostcomplexdesigntrade-offsandconstraintsofanyvertebratebodypart.Incarnivoransitscomponents havekeyfunctionsindisplay-defense,preycapture, mastication,vision,hearing,balance,olfaction,cranialenervation,andendocrinefunction,aswellas housingthebrain.Thelargestbodyofworkdealing withskullmorphology—dentitionaside—concerns howtrophicspecializationaffectsnon-dentalskull features. Moore(2009,p.197)exploredhowthe ancestralcarnivoranjawjointdivergedintwotrajectoriesfordietaryspecializations.Thejawofmost carnivoransfeaturesadeepmandibularfossaon thetemporal(= “squamosal”)bonethatlimitsthe

lateralmotionofthemandible.Theshearingfunctionofthecarnassialsoccursononesideatatime, andthemandibleshiftstowardtheshearingside foranysinglebite.Moreherbivorouscarnivorans— thegiantpandaandspectacledbears—donothave shallowermandibularfossaeasmightbeexpected forthegreaterrangeofmotionrequiredforgrindingleavesandstems.Instead,theirfossaeareeven deeperthanthoseofmorepredaceouscarnivorans andthemandibleshiftslaterallyduringasinglebite toachievethegrindingeffect.Thischewingmotion differsfromthatfoundinallotherherbivorous mammals.

Theadaptivetrajectorytowardkillingpreylarger thanthepredatorrequiresfurthermodificationto theskull.Thisnicheisoccupiedbylargefelids, canids,someursids,andsomehyaenids.Canine teethmayseemremarkablyuniforminshapeacross extantcarnivorans,butinfactshowstrongmodificationforvariousroles.Thesinglemostbiomechanicallychallengingfunctionoftheskullandteethis applyingjawforcetothetipsofthecanineteeth whilehandlingstrugglinglargeprey(Penrose etal., 2020).However,thattaskdiffersacrosscarnivoranfamilies.Slender,sharpcaninesarefoundin taxa(e.g.felids)thatkillbyquickstabstothecervicalregion(dorsalspineorneckvessels).More robustcaninesoccurinpredatorsthattakelonger tokillpreythatstruggle,orthatconsumebony material.Canidstendtohavemorecurvedcanine teeth,plausiblytoholdstrugglingpreyforlonger times(Pollock etal.,2021),andnotonlymustthe canineteethbestout,butalsothejawadductor musclesandassociatedbonystructuresmustbe strengthened—otherwise,thebraincaseisvulnerable.Theseadductors,originatingfromthesagittalcrest,thenuchalcrest,andthezygomaticarch,

areespeciallypowerfulinpredatorsoflargeprey. Thesagittalcrestrunsantero-posteriorlyalongthe dorsalmidlineandisthesiteoforiginforthetemporalismuscle,thelargestjawadductor.Itinserts onthecoronoidprocessofthemandibleandcloses thejaw.Tallandmassivesagittalcrests,resembling thesailsofsailfish—arefoundinseveralcarnivoranlineages:pinnipeds,hyaenids,ursids,andsome mustelids.Themassetermuscle,anotherpowerful jawadductor,originatesfromthezygomaticarch andinsertsontothelateralmandible.Thenuchal crest,whichfollowsthedorso-posteriormarginof theoccipitalbone,isthesiteofinsertionofneck extensormusclesthatoriginatefromthecervical vertebrae,poweringheadmovementsusedinsubduinglargeprey.Amongcarnivoranpredatorsof largeprey,allofthesestructuresarelargerelativetothefloorofthebraincase(Penrose etal., 2016).

Thebonylabyrinthisacomplexstructurethat reflectsfeedingandnon-feedingforces.Encased inthetemporalbone,itcomprisesorgansofbalance(thesemicircularcanalswithampullae)and hearing(thecochlea).Whilenotfeedingstructures perse,thecanalsarekeytomaintainingequilibriumandspatialorientationbymeasuringangularaccelerationinthreeplanes.Itisthereforean importantsenseformammals,especiallycarnivorans,withactivelocomotorandforagingstyles. Thatis,theymuststabilizetheheadinorderto allowthebraintoprocessvisualinputswhilepursuingandsubduingprey.Schwabandcolleagues (2019)showedthatalldimensionsofthesemicircularcanalswerelargerinambushingcarnivorans thaninomnivoresorpouncehunters.Astrong phylogeneticsignalwasapparentaswell.Other skullfeaturesarecloselytiedtosensorymodalities (Section5.1.2).

2.1.1 Dentition

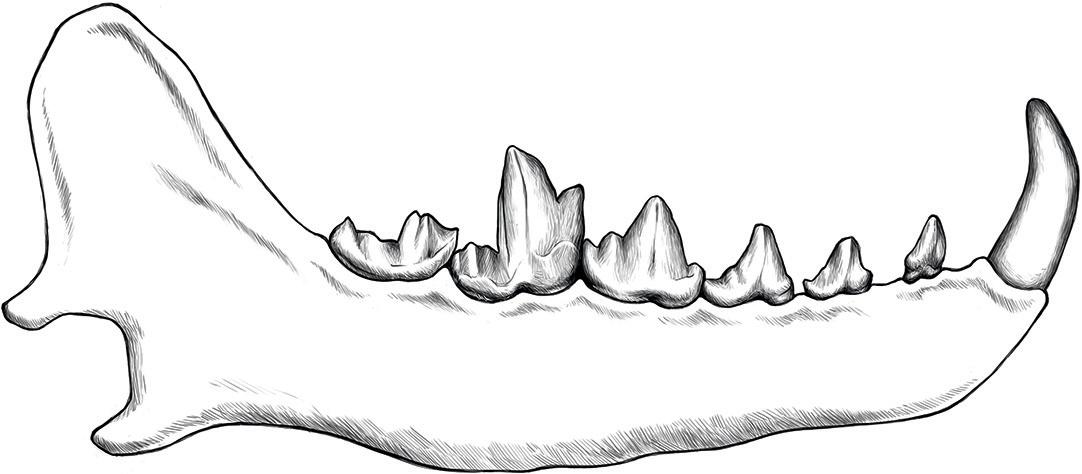

Muchstudyofmodernandprehistoricdietsof carnivoransandothercarnivorousmammalshas concernedpreyhandling(grippingandkilling) andmasticating.Basalcarnivoranshadtheprimitiveeutheriandentalformula—I3/I3,C1/C1,P4/P4, M3/M3—andteethinsomeofthesepositions evolvedmorequicklythaninothers.Alandmark incarnivorandentitionisthecarnassial(shearing)

pair:P4/M1.Thisfeatureallowsseveringofmuscle andconnectivetissue,sothatpartsoflargecarcassescanberemovedandeitherswallowedorconsumedawayfromthepreycarcass,therebyreducingconflict.TheearliestcarnivoranshadlessprominentcarnassialP4/M1 structuresthandomodern predaceousforms.Alldentalevolutioninvolved changesinsizeandshape,aswellassometooth loss;nocarnivoranlineageshowsanincreasein toothnumber.Incisorshaveundergonerelatively littlechangeinmorphologyornumber,andthe caninesareretainedeveninspeciesthatdonotuse themtohandleprey.Thisreflectsthedualfunctionsofcanines:preyhandlinganddisplay-defense. Aardwolves,bat-earedfoxes,andpandas—none ofthemprimarilypredatorsofvertebrates—have caninessimilarinshapeandonlyslightlysmaller tothoseofvertebrate-killingrelatives.Inatleast fivepredaceousmammalianlineages(twometatherian,threecarnivoran),canineteethbecamesoelongatedthattheyextendedoutsidetheoralcavity. Mostofthesetaxashowedthesaber-toothedcondition,usingcaninesforpreykilling,whereasthe oversizedcaninesofwalrusesfunctionprimarilyin displayanddefense.

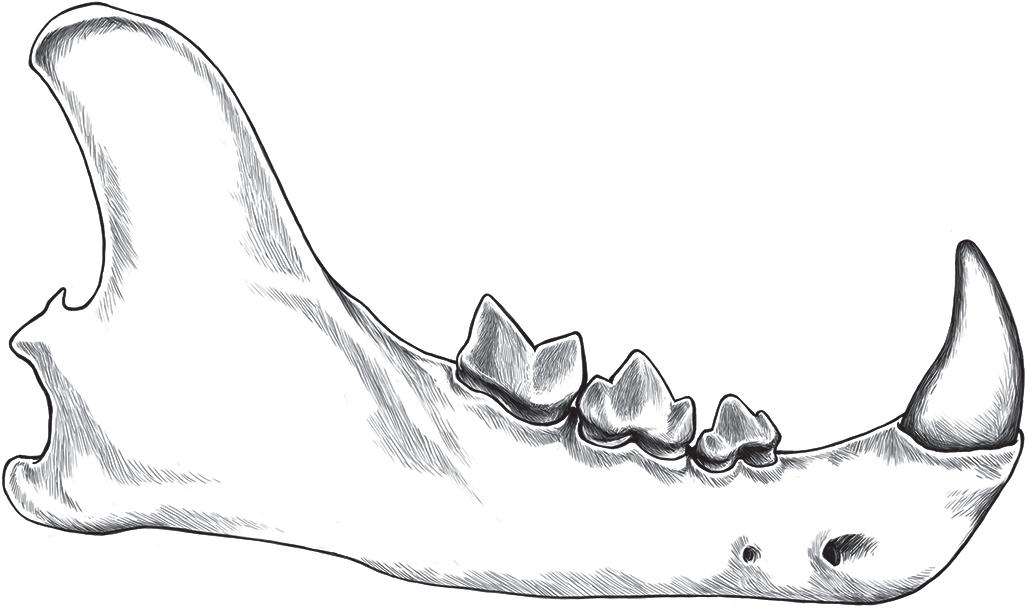

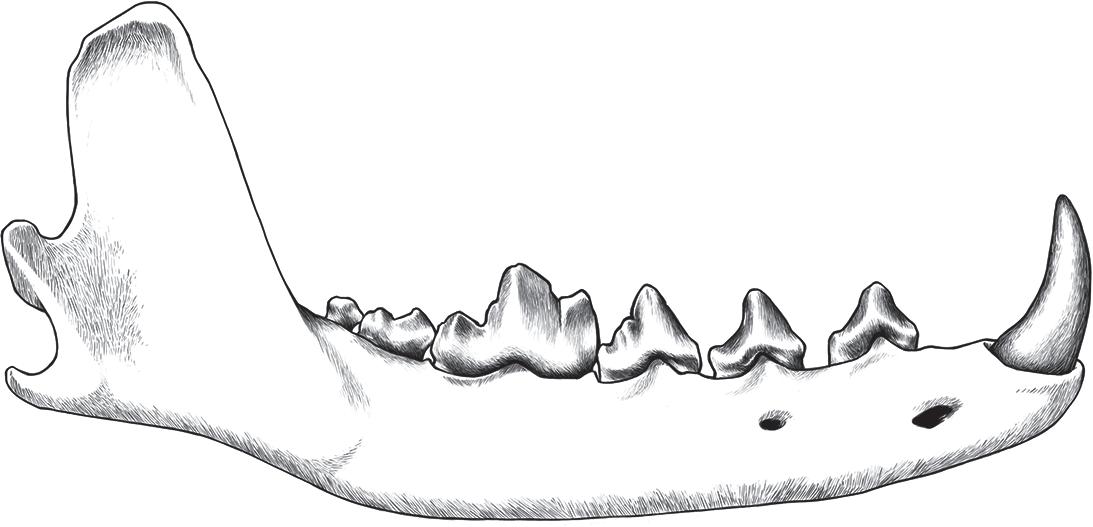

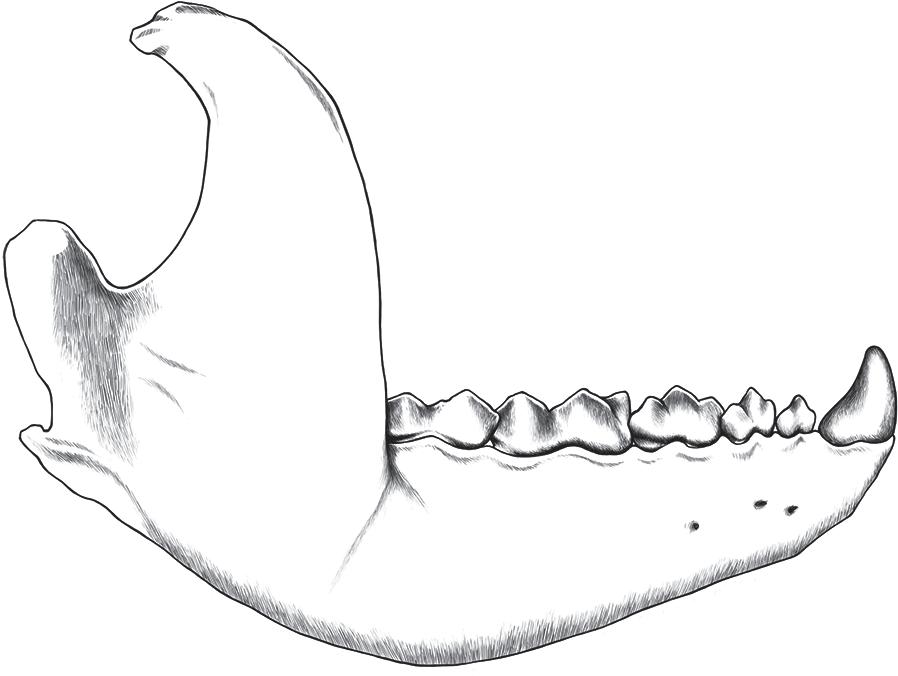

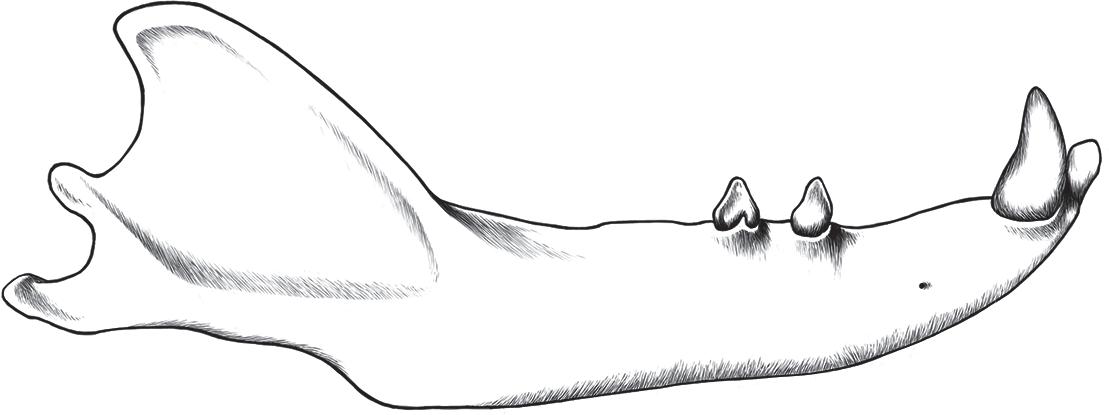

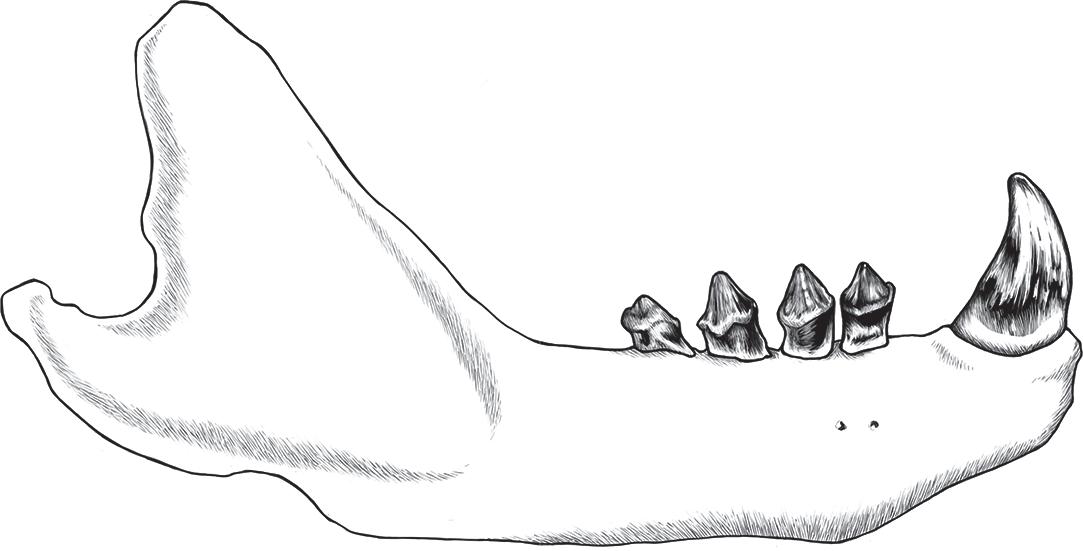

Consistentwithadaptivechangestothecarnassialsthemselves,othertoothpositionsreflectthe importanceofkillinglargepreyvs.othertrophic strategies(Figure 2.1).Withspecializationonpredationandameatdietcamethereductioninsizeand numberofthepost-carnassialteeth(M1−3,M2−3).In felids,thebestextantexamples,premolarsP1−2 and P1−2 arelostaswell,becauseadietofanimalsofttissuerequireslittlemasticationbeforeswallowing— duodenallipasesandpeptidasesaresufficient toinitiatedigestion.Thesecondtrajectory—a trendtowardomnivory,frugivory,andfolivory— retainedthepost-carnassialsandmodifiedthem forgrinding,givingthemmulti-cusped,rounded (bunodont)shapes.Bunodontteethcrushinvertebrateexoskeletonsandshells(e.g.inthewalrus andotter),andcoarselygrindplantmaterial(e.g. inbears).Inthehighlycarnivorousspottedhyena, thepre-carnassialpremolarsareenlargedforbone crushing—importantforascavengeroflargeungulatecarcasses.Piscivorouspinnipedstendtoretain large,sharpcanines,buthavelostthepositionspecificfunctionsofancestralcheekteeth,includingthecarnassialpair(Box 2.1).Instead,theytend

Figure2.1 Lowerdentitionsoftheearliestandmoderncarnivorans,showingenlargement,reduction,andlossofcheekteethwithdiverging diets.A: Protictis (Viverravidae),aninsectivore-carnivoreofthePaleocene(M3 lost).B:Modernlion,astrictcarnivore(M2–3 lost).C:Redfox,an omnivore(M2 retained,bunodont,M3 vestigial).D:Giantpanda,anobligatefolivore(M2–3 bunodont).E:Aardwolf,anobligatetermitivore(M2–3 variablyvestigialorlost).F:Californiasealion,anobligatepiscivore(M2–3 lost,post-caninesreducedandhomodont).

Figure2.1 continued towardgeneralized,nearlyhomodontcheekteeth (Figure 2.1F),consistentwithswallowingfishwhole orseveringthemintolargepieces(KienleandBerta,

2016).Importantly,carnivorandentalspecializationshavetendedtobeirreversibleoverevolutionarytime;theydisappearvialineageextinction,

Box2.1Filter-feedingcarnivorans

Severalpinnipedshaveevolvedhighlyspecializedcheek teeththatfacilitatethefilteringofaquaticinvertebrates.The waterisgulpedintotheoralcavityandpharynx,thenejected pasttheprojectionsonthecheekteeth(Figure 2.2).Thetrait hasarisenseveraltimesinthephocidsandinbothfreshwaterandmarineforms.Itreachesitsmostextremeexpression

inthecrabeatersealoftheAntarcticOcean,whicheats almostentirelyfinger-sizedkrill.TheBaikalsealofRussia showsamoremoderateexpressionofthesametrait—it feedsheavilyonfreshwateramphipods(Watanabe etal., 2020).

Figure2.2 Thecheekteethofthefilter-feedingcrabeaterseal,showingdentalprojectionsthatfilterkrillfromseawater.

Photo:©TePapaTongarewaMuseumofNewZealand.

ratherthanbyrestoringlosttoothfunctions.This issimilartomammaliandentalevolutiongenerally,butcontrastswiththatofsquamatereptiles, inwhichmultipletoothcuspsarosetogrindvegetation.Insomelineages,thesecuspsdisappeared, andcheekteethrevertedtounicuspidformasdiets returnedtocarnivory(Lafuma etal.,2021).

2.2Post-cranialskeleton

Noothermammalianordermatchestherangeof morphologicaladaptationsforlocomotionandforagingobservedintheCarnivora.Severallocomotormodalitiesarerecognizable,andsomespecies exhibitmorethanone.Basalcarnivoranswere