Prologue

“Languageisthemostmassiveandinclusiveartweknow,amoun-

tainousandanonymousworkofunconsciousgenerations.”

EdwardSapir,1921,p.235

“Deathandlifeareinthepowerofthetongue.”

Proverbs18:21

Weembarkedonthisendeavortoshowhowlanguagedevelops‘beyondagefive,’ fromchildhoodtoadolescenceandsubsequently.1 Psychologistsandlinguists,like parents,havealwaysbeenfascinatedbytheappearanceofachild’sfirstwords andhowrapidlychildrenturnintotalkers,somuchsothatumpteenbookshave beenwrittenontheirearlylanguage.Oursisabookonolderusersofalanguage. Itdealswithhowschoolchildrenandadolescentsemploylanguageindifferent communicativesettingsandfordifferentpurposes—totellstories,engageinconversations,speculateaboutthefuture,speakmetaphorically,makejokes,reflect onlanguagestructure,andevenwriteacademicessays.

Themiracleofearlylanguageissoamazingthatmanyphilosophersandlinguistsregarditasaninnateendowment,agiftthatmustbeinthegenes.Howcan languagebealearnedbehaviorgivenwhattheycall‘thepovertyofthestimulus’?2 Parentsalmostneverspeakincompletesentences,theyconstantlyrepeatthemselves,theyoftendon’tcorrecttheirchildren’smistakes.Besides,children,like grownups,saythingstheyhaveneverheardbefore.

Wewillargue,instead,thatthereisabundantevidencethatpovertyofinput makeschildrenpoorlanguageusers,whiletheoppositeistrue—arichlinguisticenvironmentmakesforbettertalkersandwriters.Inotherwords,theidea oflanguageasaninborn,geneticendowmentneedstobemodulatedbyexternalfactorsofenvironmentandculture—ambientlanguage(s),homebackground, schooling,socio-economiccircumstances,andsoon.Acrossthebook,weinvoke bothinternalandexternalfactorsasinteractinginlanguagedevelopment:genes, environment,andthenatureofthetask.Theseinvolvewhatspeakersinheritby beinghuman,thesocioculturalhabitatinwhichtheyareraised,andthepurposes forwhichtheyuselanguage,likewritingadiary,chattingatthefamilydinner table,ordecidingiftwowordsmeanthesame.

Theauthorsofthisbookarelinguists,originallytrainedinbothstructuralist (European)andformal(American)linguistics.Forthelastfiftyyears—yes,weare pre-boomerwomen—wehaveattemptedtoexplainhowlanguageoutputschange

withage.Overtheyearsofourscholarlycareers,eachofushasframedanapproach tolanguagedevelopmentinthecontextofgeneralcognitivedevelopment.Rather thantakingeitherdomain—languageorcognition—asprerequisitefortheother, weconceiveofthemasinconstantinteraction,supportingoneanotheralongthe lifespan.However,untilrecently,referencestocognitionandaffectwererather vague,andthebrain—thesiteofcognitionandemotion—waslargelymissing frominquiryintolanguagedevelopment.Currentadvancesinneurobiologyhave enabledustointegratethebrainforprovidingadeeperexplanationof(someof the)developmentalchangesweobserveintheuseoflanguage.Forexample,whyis storytellingsuchanaddictiveactivity?Whydoadolescentsdevelopsuchapeculiar vocabulary?Whyaremetaphoricalmeaningsgraspedbeforeironicones?Howis itthat7-year-oldsareunabletodefinewhatisaword,eventhoughtheyhavebeen usingallkindsofwords(appropriately)sincetheageof2?Howisitthatchildren writebeforetheyread?

Toachieveourgoalofilluminatinglanguageuseanddevelopmenthelpedby neurobiology,ourbookbeginswithanoverviewofthepropertiesofthe working brain,stressingthatthecapacitytolearnandmemorizeaswellastopredictand correcterrorsremainsplasticatleastinto,possiblybeyond,lateadolescence.The factthatcrucialdevelopmentstakeplaceinnearlyeveryaspectoflanguageuse afterearlychildhoodjustifiesthescopeofourinquiry.Thisinitialoverviewon thebehaviorofthebrain,whatitdoesordoesnotenableustoknowanddowith language,providesthesettingfortherestofthebook.Subsequently,(ineachof Chapters2to7),wecommentontheneurobiologicalunderpinningsofparticular facetsoflanguageuse,andtheskillschildrenneedtodeveloptoexpressthemselves adequatelyindifferentrealmsofexperience.

Thenextthreechaptersmovealongatimeline:Chapter2trackslanguageusage intheworldof pastexperiences,howpeoplerecounteventsfortellingstoriesin thenarrativegenre;Chapter3looksathowpeoplewieldlanguagein theactual world ofthepresent,forinteractingwithfamilyandpeersordescribingentities andpresentingarguments;Chapter4considersthewayspeoplereflectonpossible worldsandalternative eventualitiesinthefuture.

Wethenmovetotheclustersoflinguisticandcognitiveabilitiesrequiredfordifferentdomainsoflanguageuse.Chapter5takesustotheworldof imagery,where peoplespeakidiomatically,inculturallyfixedways,combiningwordsthatmake nosenseonthesurface,likesayingthatsomeonewhodied kickedthebucket adomainwherepeoplecommunicatebyimplication,indirectspeechacts,and figurativeusages.

Chapter6traceshowpeopleuselanguagetotalk about language,howlanguage isturnedfromameansofcommunicationtoanobjectofreflection.Finally,before movingontoourconcluding‘Afterthoughts,’Chapter7tacklestheworldof literacy,fromdigitaltextingtoacademicessays,wherepeopleusewritingandreading asawayofthinking—andwedistinguishbetweenscript-literacyasmasteringthe

physicalelementsofawritingsystemandtext-literacyasbeingabletohandle differenttypesofwrittendiscourse.Eachofthesixusage-basedchapters(2to7) opensbysurveyingwhatphilosophers,cognitivescientists,and/orhistorianshave hadtosayaboutthetargeteddomains,proceedstooutliningthelinguisticmeans ofexpressionthatcharacterizethemandtheirneurologicalunderpinningsin thebrain,andconcludeswiththedevelopmentaltrajectoriesthatchildrenand adolescentstraverseineachoftheserealmsofexperience.

Runningacrossthebookasawholeareseveralmotifs.

(1)Development:Akeythemeisdevelopment—inthesenseoflanguagechange inthelifeofindividuals.3 Inlinewithmainstreamlinguisticapproaches,weagree thatbeforeage5 everynormalchildisalinguisticgenius. Thebookthatheralded thecomingofageofdevelopmentalpsycholinguisticssomefiftyyearsago(Brown, 1973)endeditsstudywhenthethreechildrenwhosespeechwasrecordedhadnot yetreachedfouryearsofage.Otherstudiesclaimtoshowthatbyage3,“children haveacquiredthebasicphonological,morpho-syntactic,andsemanticregularitiesofthetargetlanguage,irrespectiveofthelanguageorlanguagestobelearned” (Weissenborn&Ho¨hle,2000,p.vii).4 Hereweaimtoshowthat,ateachpoint indevelopment,children(andadults,too)needtocopewithdifferentproblems ofverbalcommunication,forwhichtheyconstantlyneedtodevelopfreshstrategiesofadaptationanddiverseformsofexpression.Forexample,textingpeers requires(linguistic)survivalstrategiesthatdifferfromthoseforconversingata familydinnertableoransweringaquestioninclass—andeachofthesehasits owncharacteristicsamonggrade-schoolerscomparedwithteenagers.

Optimaldevelopmentofanorganismdependsonitsadaptationtovariedsurroundingsratherthansolelyonafull-blownfinalenvironment(Lehrman,1953), sothatallspeciesoforganismshaveevolvedtoadapttotheiruniquenichesateach pointindevelopment.Hereweattempttoconveytoourreadershowchildrenand adolescentsadapttoparticularnichesatdifferentpointsintheirdevelopment,by relyingonrecentadvancesinneurobiologythatdemonstratebrainplasticityand thelengthydevelopmentof executivefunctions. 5

Fourmaintimespanscanbeidentifiedinlanguagedevelopmentingeneral. Startingwith movingintolanguage frombirthto3years,childrencrosstoa psycholinguisticfrontier atlatepreschoolage(around4to5years).Subsequently,at aroundage6to12years,they‘goconventional,’adaptingtothenormsofthe ambientsocietyintheiruseoflanguageasinotherdomains.Laterstill,around ages13to19years,youngpeopleshifttoincreasingautonomyandindividuality ofexpression,withadolescenceawatershedinthetransitionfromchildhoodto adulthoodinlinguisticproficiencyasinsexualmaturationandsocialbehavior.6 Ingoing‘beyondage5,’ourbookfocusesonthelattertwostages.

(2) Neurobiologicalperspectives:Weadopta neoconstructivist approach (Karmiloff-Smith,1992)asadistinctiveframeworkinneurobiologythatshapes ourviewoftherelationshipbetweengeneticendowment,brainstructuring,and

experience,andisrelevanttolearningculturalobjectssuchaswritingormathematics.Thishighlightsseveralpropertiesofthedevelopmentofbrainstructures towardincreasingspecialization,agrowingcapacityforattendingtodifferent aspectsofataskinparallel,andgreaterskillinanticipatingoutcomesbasedon previousexperience.Otherimportantneurobiologicalfactorsinlanguagelearning andusearethehierarchicalorganizationofthebrainthatenablescognitivecontrolanditslong-lastingpowerforlearning,asanenduringcapacitythatmotivates ourinterestinlanguagedevelopmentbeyondearlychildhood.

(3) Formandfunction:FollowingpsycholinguistslikeKarmiloff-Smith(1979, 1992)andSlobin(1973,2001),ourconcerniswiththeinterrelationsbetweenlinguisticformsandtheirdiscoursefunctionsratherthanwitheitheroneortheother. By linguisticforms,werefertothestructuralelementsoflanguage—morphemes, words,clauses,sentences.Andforusaslinguists,ratherthanpedagoguesor purists, grammar referstotheprinciplesthatgovernhowpeopleactuallyuse languagewhentheyspeakandwriteratherthanrulesof correct usage. 7 Across languages,grammaticalformsfallintodifferentinteractingstructuraldomains: Phonology—howthesoundsofalanguage,itsconsonantsandvowels,itsintonationpatternsandtones,arepronouncedandhowtheyarecombinedtoform wordsandgroupsofwords; Morphology—howwordsarebuiltupinalanguage fromelementslikeroots,stems,prefixes,andsuffixes;andSyntax—howwordsare combinedtogethertoformphrases,clauses,andsentences.8

Weapproachthegrammaticalstructuresoflanguageanditslexicon(people’s mentalword-stock,theirvocabulary)infunctional terms:wequeryhowlinguistic formsareemployedindifferentcommunicativecontextsandforvariedpurposes. Thatis,ourconcerniswith authenticuse oflanguage.

(4) Languageknowledgeandlanguageuse:Awell-knowndistinctionpopularizedbyChomsky-inspiredlinguisticsisthedichotomybetweenso-called competence and performance.Performance,thewaypeoplenaturallytalkindifferentcircumstances,isconsideredastheexternalrealizationofanunderlying competence.Theperformancefacetoflanguagemaycontainhesitations,mistakes, orspeechfragments,whereascompetenceisviewedasintact,reflectingthesystemofformalprinciplesknownby“anidealspeaker-listener,inahomogenous speech-community”thus“unaffectedby[performancelimitations]”(Chomsky, 1965,p.3).Werejectthisdichotomysinceforus,whatpeopleknowabouttheir languageisnotonlymanifestedinitsuse,itisalso shaped byhowtheyuseitfor differentpurposes.9 Peoplecannotknow,andchildrencannotlearn,alanguage withoutusingit,andthemoreandbettertheyuseit,thericheranddeepertheir knowledgeofit.Besides, how weuselanguageisaffectedbythesocialsituation ofcommunication(athomeorschool,withfriendsorcolleagues,inintimatepersonalcontactorformalsettings).10 Languageusealsodependsontheparticular genreofdiscourse—conversations,jokes,stories,lectures,essays,scientificarticles, etc.Genrehasapowerfulimpactonhowpeoplespeakorwrite.Fromayoungage,

childrenemploylanguagedifferentlyinconversingwithfriends(thegenreof peer talk),whentellingastory(the narrative genre),orwhenexpoundingonatopic (an expository genre).

Comprehension(interpretingwhatapersonhearsorreads)andproduction (formulatingwhatapersonsaysorwrites)arebothfacetsoflanguageuse—though somemistakenlyidentifycomprehensionwithcompetence.Fromearlychildhood throughoutthelifespan,comprehensiontypicallyprecedesandexceedsproduction(Campbelletal.,1982;Keenan&MacWhinney,1987).Peopleunderstand morewordsthantheyproduceintheirownspeechorwriting(theirreceptiveversusproductivevocabulary),andweallunderstandcomplexsyntactic constructionsthatwemightneverourselvesproduce.

Thisbookdealsmainlywithproduction,sincecomprehensionstudiesaretypicallyexperimentallystructuredanddealwithisolatedlinguisticformsratherthan text-embeddedusageinauthenticcontexts.Weareinterestedintheunconsciously internalizedknowledgethatspeaker-writersrecruitwhentheyuselanguageto chat(orallyorbytexting),toargue,ortoanalyzeatopic.Butwealsoconsiderthe factthatpeoplecanbringthisunconsciousknowledgetothesurfacebyexplicit mentionofanalyticalfeaturesoftheirlanguagebymeansof meta-linguistic commentary(Chapter6).Thismighttaketheformofachildsaying“Iknowwhy elephant issuchalongword,becauseanelephantisbigandamouseissmall”; andahigh-schoolstudentwillrecognizethatawordthatsoundsthesamemay havedifferentspellings(Chapter7),differentmeanings,anddifferentsyntactic functions(e.g.,theverbs RODE, ROWED,andthenoun ROAD).11

(5)Literacy:Becomingliterateisanintegralpartoflaterlanguagedevelopment, bothtobeafullyfunctioningmemberofone’scommunityandasafactorthat changespeople’sknowledgeandperceptionoftheirlanguage.Wechallengethe typicaloppositionbetweenlanguageacquisitionasa natural processandliteracy asaninstructionaloutcome:languageisneitherstrictlynaturalnorislearningto readandwritestrictlyinstructional,suggestingthatwemayneedtoreassessthe notionof natural processes.

Individualsraisedinliteratesocietiesoftodayneedtoadapttoconstantly changingcommunicationtechnologiessoastoparticipateactivelyintheirsocioculturalenvironment.Atthesametime,literatepeopleneedtoadapttothe socio-culturalandrhetoricalconventions oftheirculture.12 Inmanytraditional cultures,agoodstorymustcarryamoral;infood-gatheringsocieties,narratorstellingastoryaboutaquestwillprovidedetailsoftheroutetakenbythe participant(s),highlightingthescriptofpathsinexpeditionsaimedatfinding food.Incontrast,narratorsraisedingoal-orientedWesterncultureswilldescribe thesame situationintermsoftheendpointgoaloftheprotagonist(s),showing culture-bounddifferencesinwhatpeopleconsiderrelevantorimportanttoconveytoothers.Thisvariationisalsodevelopmentallymodified,sincethe content oftextsproducedbyyoungerchildreninagivensocietydiffersfromthatoftheir

elders,affectedbothbytheirsharedsocio-culturalbackgroundandbythecognitiveboundariesoftheirworldknowledge.Weshowthat,withage,narratorsshift tomoreabstractandesoterictopics,forexamplebydescribingconflictinterms ofphysicalfightingtodisagreementsinprinciple,bytalkingabouttheftofconcretepossessionstoplagiarizingofideas.Andwealsoqueryhowsuchvariation isaffectedbydifferentrhetoricaltraditions(ContinentalversusAnglo-American, say)thatshapelanguageuseforacademicpurposesinthecontextofglobalization andthehomogenizingimpactoftheinternet.13

(6) Filteringbylanguage:Languagedevelopmentis filtered bythesetoflexicalandgrammaticaloptionsprovidedbytheparticularlanguagethatisbeing acquired(Berman&Slobin,1994,pp.517–533).LearnersofEnglishfaceadifferenttaskfromlearnersofthesameageandbackgroundacquiringHebrewor Spanishasafirstlanguage.Thisdoesnotmeanthatitismoredifficulttobecome anativespeaker inonelanguagethananother;onthecontrary,thepathtobecominga proficientspeaker inone’sfirstlanguagefollowsasimilartimelineinZuluor Portuguese,inGermanorTurkish.Butthewayspeakersformulatetheirideasin thedomainsofourconcernhere(tellingastoryorajoke,arguingaboutthecurrentstateofaffairs,orrelatingtofuturepossibilities)willdependontheparticular lexicalelementsandgrammaticalstructuresoftheirnativelanguage.

Theideaoffilteringcanalsorefertoanindividual’sperspectiveinusinglanguage indifferentcircumstances.Thesituationswetalkorwriteaboutdonotpresent themselvestousaspre-encodedverbally.The same experiences,events,andideas arefilteredbyspeakers’worldknowledgeandtheperspectivetheyselectfortalking aboutagivenstateofaffairs.Twopeoplemightrespondcompletelydifferentlyto beinginisolationduringtheCOVID-19pandemic:SpeakerA:“Itwasawelcome time-outfromthehassleandbustleofmyordinarylife”;SpeakerB:“Itsentme intoastateoftotalclaustrophobia.”Besides,howweencodetheworldverbally dependsonthe linguisticchoices wechoosetomake.Thisisbecause“different lexico-grammaticalchoicescanbemobilizedtorealizethesamerhetoricalgoals equallyconvincingly”(Chang&Schleppegrell,2011,p.148).Peoplecananddo usedifferentwordsandgrammaticalconstructionstoexpressthesameidea.14

Apuzzlehereishow,ifatall,languagedevelopmentisaffectedbywhethera languagehasdedicatedgrammaticalmeansformarkingagivenconceptualdistinction.Forexample,Englishhastwodifferentformsfortalkingaboutsituations thatareinprocessatthetimeofspeakingasagainsthabitualstatesofaffairs:compare‘she istalking Russian/she talks Russian’(Chapter3).ButnotallEuropean letaloneSouth-EastAsianlanguagesmakeanovertdistinctionbetweenthetwo. Thesameistrueofthedifferencebetweenhypotheticalandcounterfactualconditionalsentences: Ifyoutriedharder,youwouldsucceed/Ifyouhadtriedharder, youwouldhavesucceeded (Chapter4).Doesthismeanthatspeakersofsomelanguagesdonotunderstandthedifferencebetweenwhatisgoingonrightnowor whatisgenerallytrue?Orbetweenapossibilitythatcanstillberealized(youcould

stillsucceed)andonethatisnolongerpossible(youdidn’ttryhardenoughsoyou didn’tsucceed)?Wedoubtthatthisisso.Ontheotherhand,“ifalinguisticformis highlyaccessible,itsfunctionaldevelopmentmaybeaccelerated”(Slobin,2001,p. 624),sothathavinganovertlyavailableformmaymakeagivendistinctionconceptuallymoresalientforspeakersingeneral.Hereweareleftwithwhatwefind tobestillalargelyunresolvedpuzzle.

Slobin’spath-breakingstudyonuniversalandparticularinlanguageacquisition (1982),comparingthelinguisticperformanceofchildrenaged2to4years,native speakersoffourdifferentlanguages(English,Italian,Serbo-Croatian,Turkish), showedthatthe2-year-oldswereallalikeintheirverbalabilities,andclearlyless proficientthantheolderchildren.YetallthespeakersofEnglishwerelinguisticallymorelikeoneanother,andmorelikeadultEnglishspeakers,thanwerethe Italian,Turkish,or(then)Serbo-Croatians.Thisinsighthasledustoavoidan Anglo-centricbiastoarguethatthefactorsofage(development)andtargetlanguage(typology)interactacrossthelifespaninmovingfrominitialtoadvanced statesoflinguisticknowledgeandlanguageuse.

Thechildrenandyoungpeoplethatpopulateourbookaregenerallyso-called mainstream studentsraisedinIsrael,theU.S.,andSpain,althoughthroughoutwe alsogiveexamplesfromotherlanguages.Theyaretypically-developingchildren andadolescents,whodonotsufferfrominternaldisordersorlanguage-related physicaldisabilities.Werecognizethecriticalimportanceofatypicaldevelopmentforsheddinglightonlanguageknowledge,development,anduse(Thomas &KarmiloffSmith,2003).Butthepresentvolumewouldhavedoubledinsizehad wegiventhisdomainitsdue.

Finally,thebookisdedicatedtothelateAnnetteKarmiloff-Smith—colleague, teacher,andfriend.Ourapproachislargelyinspiredbyherideasondevelopment, hercontributionstoneuro-constructivistthinking,andherneithernativistnor empiricistconceptualizationofhumancognition.Sheissorelymissedbyusboth andwouldhavebeenaninvaluableconsultantatallphasesofourworkonthis book.

Notes

1. TakenfromthetitleofKarmiloff-Smith’s(1986a)chapter‘Somefundamentalaspects oflanguagedevelopmentafterage5.’

2. ThetermwascoinedbyNoamChomskyinhis1980“replytoPiaget.”

3. Thenaturalsciencesdistinguishbetween ontogeny—theoriginanddevelopmentof anorganismusuallyfromthetimeoffertilizationoftheeggtoadulthoodacrossthe lifespan—asagainst phylogeny—thestudyoftheevolutionarydevelopmentofgroups oforganismsbasedonsharedgeneticandanatomicalcharacteristics.Thisperspectiveisbeyondthescopeofourundertaking,nordowetakeintoaccount diachronic linguistics,concerningchangesinagivenlanguageacrosstime.

4. Thisledto(re)namingthefield‘languageacquisition,’intheviewthatlanguageis acquirednaturally,withoutspecialinstruction,ratherthan‘languagelearning,’which impliessomeinstructionorconsciouslearningratherthanspontaneousprogression ofknowledge.

5. Executivefunctions arethecognitiveprocessesnecessaryforselectingandsuccessfullymonitoringbehaviorsthatfacilitatetheattainmentofchosengoals,intheform ofmentalabilitieslikeworkingmemory,flexiblethinking,andself-control.

6. Acrossthebook,wherechronologicalagesarementioned—e.g.,12months,age3;6,15 to16years—thesearegrossapproximationssomewherearoundtheaverageormedian agerangeforagivenphenomenonasdocumentedinresearchonlanguagedevelopmentaroundtheworld.Whenmeanageincludesyearandmonths,thetwovaluesare separatedbyasemi-colon(e.g.,6;8 = sixyears,eightmonths).

7. ThetermenteredEnglishfromOldFrench grammaire viaLatinfromGreek grammatikē(tekhnē) ‘(art)ofletters,’from gramma, grammat- ‘letterofthealphabet, thingwritten,’withgrammaroneofthethreepillarsofMedievalscholarship,together withrhetoricandlogic.Tothisday,manyidentifyitwith‘correctusage’(whateverthat means),takingtheclassicallanguagesasmodels,andconsideringthevernacularsof everydayspeechbeneaththedignityofformalstudy.Inmodernlinguistics,incontrast, grammar referstothe structural aspectsoflanguage,howlinguisticelementsarebuilt upintolargerunits,frommorphemestowordsandontophrases,clauses,andupto fullsentences(again,whateverismeantbycommontermslike‘word’or‘sentence’). Infact,thenotionof sentence islargelyanartifactofformalgrammarsorlinguistic scholarshipratherthanaviableconstructforactualusageinspeech(Halliday,1989) oreveninwriting(Chafe,1994).

8. Forexample,theEnglishword elephant cantakethegrammaticalinflection-s toform itsplural,andthederivationalsuffix -ine changingitfromanountoanadjective elephantine.

9. Thisdichotomyhasbeenqueriedonseveralgrounds.ThesociolinguisticWilliam Labov(1972a)remarks:“Itisnowevidenttomanylinguiststhattheprimarypurpose ofthe[performance/competence]distinctionhasbeentohelpthelinguistexcludedata whichhefindsinconvenienttohandle….Ifperformanceinvolveslimitationsofmemory,attention,andarticulation,thenwemustconsidertheentireEnglishgrammarto beamatterofperformance”(pp.109–110).

10. Someresearchers(e.g.,DeBusser&LaPolla,2015)gosofarastoarguethattheextralinguisticenvironmenthasaneffectnotonlyonhowlanguageisusedindifferent circumstances,butalsoonthegrammaticalstructureoflanguages.

11. Wordsthatsoundthesamebutarespelleddifferently,like road, rode, rowed,or write, rite,and right,arecalled homophones;wordsthatarespelledthesamebuthavemore thanonemeaning,like watch, adder, battery,arecalled homonyms.

12. Unlikeinancienttimes,weusetheterm‘rhetoric’initscontemporarysense,toapply tothelinguisticandstylisticresourcesutilizedbyaspeaker/writerfororganizingand deliveringapieceofdiscourse.

13. Aleitmotifofourworkisthedistinctionbetween grammaticalforms asrequiredby thestructuralconstraintsofagivenlanguage(itsphonology,morphology,andsyntax)

andrhetoricaloptionsthatpeopleselectoutofthisrepertoireofformswhenexpressing themselvesinspeechorwriting.

14. PerhapsLewisCarrollputthisbestin ThroughtheLookingGlass (1871,pp.364–365).

“‘WhenIuseaword,’HumptyDumptysaidinratherascornfultone,‘itmeansjust whatIchooseittomean—neithermorenorless.’

‘Thequestionis,’saidAlice,‘whetheryoucanmakewordsmeansomanydifferent things.’

‘Thequestionis,’saidHumptyDumpty,‘whichistobemaster—that’sall.’”

Brainsforlanguage(andeverythingelse)

Thelittleboyisnearly14monthsold.Hisparentsareecstatic:Juantalks!Heproducedafewsoundssqueezedtogether,somethinglike‘awhe’thatsoundedlike agua,theSpanishwordforwater.Yethisparentsaresoconvincedoftheinevitabilityoflanguagedevelopmentthatifsomemonthspasswithoutnewoutputsfrom theirchild,theywillbegintoworry.Infact,Juanwasabletocommunicatewith othersevenearlier:hecouldshowhewantedtoreachanobjectbypointing,he couldbabbleusingmeaninglessbutlanguage-likesyllables,andwouldshowanger orpleasurebyfacialexpressionsandbodylanguage.But,asparentsknowintuitively,linguisticdiscourseissomethingelse.Indevelopingalanguage,children appropriateasystemofelementscalledspeechsoundsthatcombineinendlesswaystoconveymeaninginincreasinglydiversecontexts.Communication enabledbylanguageisatoncehighlyregulated(noteverycombinationofelementsismeaningful)yetopen-ended:peoplecantalkandwriteaboutanything conceivable.

Childrenlearnearlyonwhatcombinationsaremeaningfulintheambientlanguageand,overtime,cometouselanguagefordifferentpurposesandindifferent scenarios.Thistransformsthewaypeoplethinkanduselanguageinavirtual cycle,an‘iterativebi-directionalinteractivity’betweenthinkingandusinglanguage.1 Learningalanguagemeansenteringthiscycle.Beforetheystartschool, normallydevelopingchildrenhavemasteredmuchofwhatthereistoknowabout theirlanguage.2 However—andthisisthe leitmotif ofthisbook—theywillcontinuebuildingandcruciallychangingthisknowledgeuntiltheirteenageyearsand beyond,inconstantinteractionwithothers.

Whatdoparentsconsidertheirchild’s firstword?Anysequenceofsounds s/heproducesthatresemblesaknownword,liketheEnglish doi for‘doggie,’ theSpanish wawa for agua ‘water,’ortheHebrew aba for‘Daddy,man.’These expressions—thoughfarfromconventionaladulttermsinpronunciationorthe entitiestheyapplyto—reflecttheuniquelyhumanabilityofmatchingstrings ofsoundstomeanings.Thishugecognitiveandcommunicativeleapoccursat aroundage1year,from8–9monthstoaround18months,among typicallydeveloping children.(Forouruseoftheterm‘age,’seenote4inthePrologue.) Thismarksthebeginningofalongandfascinatingjourneyconnecting words toworlds,firstreferringtoobjectsineverydaysurroundings,like kabo ‘pig’in theKalulilanguageofPapuaNewGuinea.Astheygrowolder,thewaychildren

talkchangessimilarlyindifferentcultures:theirpressed-togethersoundsbecome increasinglylikewordsintheambientlanguage(s);andbyage2years,children willcombinetheseitemsintoutterancesthatexpressdesires(gimmeball, more milk),complaints(soretummy),anddescriptionsofstatesofaffairs(allgonebaby milk, thassabigball).3

Bylatepreschool,childrenwillbeabletostringutterancestogethertotellstories (Ronnyhitme,soItoldtheteacher,andshesaidhe’sanaughtyboy),subsequentlyto discussabstractpossibilitiesinthefuture(Idon’tknowwhenDaddywillcome,but hetoldmehe’dbringmeapresentfromhistrip),touselanguageformetaphor,for writingandreading,andthemanyotheractivitiesperformedbyliteratemembers oftheirspeechcommunity.

Thesethreefacts—(i)emergenceofspeechatsimilaragesindifferentlanguages andpartsoftheworld,(ii)unstoppable(non-pathological)developmentinapredictabledirection—fromwordsviaword-combinationstoextendeddiscourse, and(iii)useofspeechthatisattunedtoaspecificlanguageenvironmentandto particularcommunicativeintentions—indicatethatlanguagedevelopmentispart ofourmaturationashumanbeings,thatithasageneticunderpinning.Yet,wewill argue,languagedevelopmentisatthesametimestronglydependentontheenvironment.Anditalsodependsonthe task facingalanguageuser—quarrelingwith aclassmate,takingpartinfamilyget-togethers,tellingastory,orwritinganessay.

Elizabeth Bates(1979) putitclearly:“Theformofthesolution[totheproblemofbehavioraluniversals]isdeterminedbytheinteractionof three sources ofstructure:genes,environment,andthenatureofthetask”(p.17).Genesand environmentprovidethematerialandrelevantinputstosolvingthetask,while socio-cognitivegrowthandexperiencewithlanguageuseprovidetherestofits solution.

Ourview,then,encompassesbothinternalandexternalfactorsimpingingon thedevelopingorganism.Thegoalofthisbookistoshedlightonwhenand howtheenvironmentinfluenceslanguagedevelopmentandhowgenetic,environmental,andtask-relatedfactorsinteractbeyondtheearlystagesoflanguage acquisition.

Afterreadingthischapteryouwillbeacquaintedwith:

• ourmotivesfortakinganeurologicalperspectiveonlanguage,tounderstand thegeneticandneurologicalcapacitiesunderlyinglanguageuseanddevelopment,bymeansofashortjourneythroughthepartsofthebrainthatlearn language;

• howresearchershavearguedforthebiologicalcomponentoflanguage acquisition—suchasbyprovingtheexistenceofa criticalperiod,anagelimit forthecapacitytoacquirelanguagenatively;

• thefactthatmuchofthebrain’sfunctioningisnotaccessibletoconscious control,byconsideringtheprocessesof priming and relearning;

• theneuro-constructivistapproach,asadistinctiveframeworkinneurobiologythatsupportsourviewoftherelationshipbetweengeneticendowment,brainstructuring,andexperience;

• themainpropertiesofthedevelopingbrain:(i)itsincreasingspecialization; (ii)itsgrowingcapacityforparallelprocessing;(iii)itsfunctioningasan anticipatorymachinebasedonsensory-motorexperience;(iv)itshierarchicalorganizationenablingcognitivecontrol;and(v)itslong-lastingcapacity forlearning,acharacteristicthatmotivatesourinterestinlaterlanguage developmentswellbeyondearlychildhood;

• thecrucialchangesthattakeplaceinlearninganduseoflanguageinfour distinctperiodsoflife:frombirthto3years,whenchildrenmoveintolanguage;age4to5years,asapsycholinguisticfrontierbetweenearlyandlater languageacquisition;age6to12,whenchildren‘goconventional’;andage 13to19,whenyoungpeoplebecomeautonomousand(sometimes)creative individuals.

1.1 Aneurobiologicalperspectiveonlanguage

In1969thepsychologistEricLennebergproposedthat“thedevelopmentof languageinchildrencanbestbeunderstoodinthecontextofdevelopmentalbiology”(p.635).Headvancedthehypothesisofalimitedtime-spanin whichbrainsareuniquelyattunedtoacquiringlanguage(orlanguagesinthe caseofearlybi-ormulti-lingualism).Hedefinedthisasa criticalperiod fornative-likeacquisitionoflanguage,occurringduringthefirstfewyearsof life.Subsequentresearchhasextendedtheideaofbiologicaldeterminismin relationtoacriticalperiodfornativelanguageacquisitioninvariousways (Knudsen,2004).

ThediscoveryofGenie,theferalchildwhohobbledintoaLosAngelescounty welfareofficein1970,providedunhappyevidenceforLenneberg’s criticalperiod hypothesis.Atage13,havingbeendeprivedoflanguageinput,Geniedidnottalk, andeffortstoteachhertodosoprovedlargelyfutile(Curtiss,1977).Othersources ofevidencealsopointtoacriticalperiodafterwhichnativelanguageacquisition isinhibited(J.L. Locke,1997).ThepsycholinguistElissa Newport(1990) applied twosuchmethodstotestbiologicaldeterminism.Sheexaminedwhathappens tothelanguageofdeaforhearing-impairedchildrenwholackearlyexposureto spokenorsignedlanguage;4 andsheobserveddevelopmentofasecondlanguage (L2)inchildrenwholackedearlyexposuretotheL2.Heranalysesofhowlanguage develops—inchildrenexposedtoAmericanSignLanguage(ASL)frombirthcomparedwiththosewholearnitonlylater,andinchildrenwhoacquireEnglishasa nativelanguagecomparedwiththosewhostartlearningitlaterinlife—revealed whatmostofushaverealizedatsomepointinourlives:ifonestartslearninga

newlanguageafterschool-age,itwillbeverydifficulttobetakenasanative,even afteryearsofstudy.

Adifferentpictureemergesfromathirdwayoftestingclaimsforacritical period:byexaminingtheconsequencesof braindamage.Theso-called‘lesion method’isatraditionalresearchstrategyinneurologyandneuropsychology.5 Analyzinghowmentaloperationsbreakdownafterbraininjuryallowsresearchers toidentifytheoperationsthatunderliecognitiveprocesses.Whenappliedto brain-damagedadults,thisilluminateshowbrainstructuresrelatetofunctions withintheneurocognitivesystem(Stilesetal.,2012).Forexample,autobiographicalmemoriesfromanindividual’spersonalhistory,whicharesupportedbybrain structuresthatunderliestorytelling(asdiscussedinChapter 2),arelimitedin brain-damagedpatientstomemoriesacquireduptoorshortlybeforetheonset oftheirinjury(Young&Saver,2001).

Whenappliedto children,thelesionmethodmayshedlightonquestionsof neurocognitiveplasticityanddevelopmentaladaptation(Stilesetal.,2012).If researcherscandemonstratethatotherareasofaninjuredbraincanmakeupfor thedamageincurred only whentheinjurytakesplaceatanearlyage,theywill haveprovedthatthereisacriticalperiodlimiting compensation,asasignofbrain plasticity.

Whenlesionsoccurinspecificareasinthelefthemisphere(LH)beforeor justafterbirth,atimeofspecialreadinessforacquiringlanguage,childrenshow markeddeficitsinacquiringtheirinitialvocabulary(Stilesetal.,2005).Theseearly impairmentsarenolongernoticeablebyaroundage5years,suggestingthatthe immaturebraincancompensateforsuchdeficits.Incontrast,adultswithdamage insimilarlanguageareasshowconsiderablelanguageimpairmentwithvariable, oftenatbestonlymoderate,recovery(Damasio,1992; Lazar&Antoniello,2008).

RajaBeharelle(RajaBeharelleetal.,2010)comparedright-handedadolescents whohadsustainedpre-orperinatalleft-hemispherestrokeswiththeirintactsiblings.Theyusedfunctionalmagneticresonanceimaging,fMRI,toexaminethe brainactivityofparticipantsperformingacategoryfluencytask,i.e.,namingitems inacertaincategory(likeanimalsorfoods).Healthyadolescentsshowedstrong activityinleftandlessinrighthemisphere(RH)structures.Incontrast,onthe sametask,patientswithearlyinjurymobilizedactivityeitherintherightorin bothhemispheres,withmarkedindividualdifferences.Itseemsthatourbrain findsdifferentwaystocompensatefordamage.

Theseandrelatedfindingsunderminetheconstrainingroleofthecriticalperiod ofbrainplasticity.Itturnsoutthatlanguagelearningisenabledbyabiological readinessatseveralanatomicalsites,andthatthislearningcapacityisimprovedby therequiredexperienceattherighttime.Wherethisisnotthecase,asinlateexposuretosignlanguagefordeafchildren,oranewtargetlanguageforL2learners, thebrainaltersitscapacitytolearnfromexperience.Butthiscapacitydoesnotdisappear:it changes.L2learnersmaynotattainanative-likelevelofcommand,but

theyarestillcapableoflearninganotherlanguage,althoughwithmarkedindividualdifferences.Besides,whentheanatomicalsiteinchargeofenablinglanguage learningsuffersdamageduringthecriticalperiod,otherbrainsitesarerecruited toaccomplishthelanguage-learningtask.Thatis,thereareotherpotentialbrain organizationsforimplementinglanguageafterearlyLHbraininjury,afactthat reflectssubstantialplasticity.

Theseandrelatedevidenceforearlyplasticityofthebraininthefaceofchangingenvironmentalinputhasledresearcherstotalkabouta sensitive ratherthan acriticalperiodinemergingneuralorganizationandassociatedbehaviorduring thelifespan.InSection 1.4.1,weshowhowlearning-associatedinputshapespatternsofconnectivityandrefinestheneuralsystemsinthebrain,makingthem morespecializedforprocessingparticularinputs.Aslearningproceeds,patterns ofconnectivityintensify,andfunctionswithinaregionbecomemorespecifically defined.Theendofthesensitiveperiodmaythussignaltheendofthelearning processitself,thestabilizingofaneuralsystemonceexpertiseisacquiredinaskill area(Johnson,2005).

CurrentresearchonL2learning,basedonmorethantwomillionlearners ofEnglishasasecondlanguage,proposesextendingthesensitiveperiodtoage 17–18(Hartshorneetal.,2018).ThestudyalsoindicatesthatearlyL2learnersare notsuperiortoadultlearnersoverall,rathertheycopebetterwithdifferentfacets ofthetask:earlylearnersoutdoadultsinpronunciation,butadultsarebetterwith syntacticfeatureslikewordorder.Thisdifferencehastodowithdifferentialattentiontoelementsofthenewlanguage:childrengraspmultiwordstrings,guidedby theirintonation,whereasliterateadultstendtoprocessL2inputwordbyword. Theadvantageofearlylearners,then,isnotsimplyduetothedeclineofasensitive period,butalsotodifferencesinhowtheylearn(Havron,2017).

Then,too,theadventoftechnologiesthatenableresearcherstolookinsidethe livinghumanbrainhasradicallychangedthewaywethinkaboutbraindevelopment.Theydemonstratethatnoteverythingthatiscrucialaboutlanguagereaches maturationduringtheearlyyears,callingintoquestiontheconvictionofthebulk ofresearchonchildlanguagethattothisdayislargelyconfinedtothespeechof infants,toddlers,andpreschoolchildren,oftennolaterthanage3years(Brown, 1973;Weissenborn&Ho¨hle, 2000).Againstthisbackground,wenowproceedto howthefunctioningofourbrainsupportslifelonglearninganduseoflanguage.

1.2 Unconscioussteering

Althoughourbrainregulatesthe typeofattention wepaytotheworld,controlof thisattentionusuallyescapesconsciousaccess.Forexample,wedonotattendto soundsthatourbraincannotprocess,althoughtheymaybeaccessibletoourdog orcat.Similarly,adultspeakersofEuropeanlanguagescannotprocesstheclicksof

Bantulanguagessincetheyarenotpartoftheirworld,buttheymaybediscernable toinfantsbornintonon-Bantuspeakingenvironments.6 Theworldsthatweexperiencedependonthetypicallyunconsciousprocessingcapabilitiesofourbrain, whichchangeasaconsequenceofdevelopmentanddifferinginputsfromtheenvironment.Everydomainofexperience—speech,space,time,number—undergoes bothmacroandmicrochangesinprocessingcapabilities;andsodoestheworld asweperceiveandunderstandit.

Imagineyouhavereadastoryaboutrabbitsandarethenaskedtowritetheword hair.Youwouldlikelywrite HARE.Readingaboutrabbits(interactionwithinput fromtheenvironment)haspreparedyourbraintofocusonthe“rabbit”meaning of hare,activatingawordpronouncedthesamebutspelleddifferentlyfromthe oneelicited.Orimagineyouoncelearnedthelyricsofasongbyheart,butnow canonlyrememberabitofit.Inabilitytoretrievesomethingdoesnotmeanthat itiscompletelygonefromyourlong-termmemory.Lateron,relearningitwill bemuchquickerbecauseyourpreviouslearningofthesonghasmodifiedyour currentabilitytolearnit.

Therabbitandthesongexamplesillustratethepsychologicalphenomena of priming and relearning (Bargh&Morsella,2008). Primingistheactivation ofcertainassociationsandmemory,evenwithoutawarenessofwhatevokes them;relearningreferstothefacilitatingeffectofpreviouslylearnedmaterial. Bothdemonstratehowspecificinputfromthesurroundingsmaychangefurther perceptionofandinteractionwiththeenvironment,andhowthesechangesoccur.

Asaninstanceof priming,theactivationof HARE insteadof HAIR forreaders oftherabbitstorycameaboutwithoutawareness.7 Similarly,for relearning in thesongexample,althoughthelearningprocessingwasexplicit(throughsuccessiverehearsals),whatremainedofit(retainedinlong-termmemory)wasstored implicitly.Partofwhatwedo,think,andfeelcanbebroughtintoconsciousnessand,insomecases,canbenamedandverballyexplained.Yetmostofwhat weknowaboutourlanguagehasnotbeenexplicitlytaught,anditsuseisnot consciouslycontrolled.

Ourbrainprocessesdifferentkindsofinput—music,pictures,writtenand spokenlanguage—throughoursenses.Andwedependonthisprocessingfor understandingtheworldandourselves.Butthebrain“runsitsownshow,”soto speak.Decision-making,planning,predicting,learning,andalsoforgettingrun deepinourneuralinnercosmos,accountingforthewaywemoveinspace,grasp objects,solveproblems,approachpeople,and—ourmainconcern—uselanguage totalk,read,andwrite.Weprocessfeaturesofourlanguagethatareimplicitly depositedandstoredinourbrainafternon-consciousrehearsal.Eagleman(2011) putitwell:“Yourconsciousnessislikeatinystowawayonatransatlanticsteamship, takingcreditforthejourneywithoutacknowledgingthemassiveengineering underfoot”(p.4).

Consider,forexample,acommonbehaviorduringlanguageuse.Whenpeoplechat,tellastory,orgivedirections,theyoftenmakechangesintheirspeech, whetheraword(1)orpartofasentence(2).

(1) Turnrightatthe first thethirdcorner

(2) Turnrightthen don’tturnright betternot

These self-repairs usuallyimprovethemessagethatspeakersareattemptingto conveyandtheresultingexpressioniscomprehensible,eventhoughtheadjacentstringsofwordsmaynotstrictlyfollowtherulesofgrammar—asin(1) and(2).

Peopleareusuallysurprisedwhentheyheartherepairstheyhavemadeand arehardputtoexplainthem,althoughtheycanidentifythemwhenaskedto judgewhatotherpeoplesay.Yetlinguistsandpsychologistshavefoundhidden treasuresinstudyinghowspeakersidentify,produce,andexplainself-repairs, correctingtheirspeechoutputastheygoalong.From6to7yearsofage,childrencan detect differentkindsofspeechrepairs,butexplicitcontrolandprovisionofverbalexplanationsfortheserepairstakeuntiladolescencetoacquire. Withage,childrendevelopincreasingawarenessaboutdifferentaspectsoflanguage(seeChapter 6).Forexample,theywillrecognizethat,inthecaseof hair/hare,thesamestringofsoundshastwodifferentmeaningsandisspelled intwodifferentways.Yetnumerousfeaturesremaininaccessibletoconsciousness,whilesomerequiretheinterventionofthewrittenmodalitytobeaccessed. InChapters 6 and 7,wediscusshowformalinstructionmodifieschildren’slinguisticinput,enablingthemtoreflectonlanguageandpromotingmetalinguistic understanding.

1.3 Thebrainthatdoeslanguage—alongwitheverythingelse

AlkmaionKrotonietes,Pythagoras’syoungdisciple,wasthefirsttosuggestthat thebrainisthelocusofourmind,whereasAristotlebelievedthehearttoplaythis role.Nowadays,scholarsandlay-peoplealikerecognizethatwethinkwithour brains.8 Wecanevenexplainwhycertaintasks—likeproducingasentencewith severaldependentclausesorcomposinganessaythatmakessensefrombeginning toend—aremoredemandingthanothers.

Whatarethepropertiesofthisdevicethatgeneratesthehumanmind?How doesit do language?AndhowdothesepropertiesexplainwhatThomas Suddendorf(2013) definesas“thepeculiarityofthehumanmind:…ouropen-ended capacitytocreatenestedmentalscenariosandourdeep-seateddrivetoconnectto

otherscenario-buildingminds”(p.276).Toaddressthesequestions,wealignwith theneuro-constructivistviewthatunderstandingcognitivedevelopmentrequires knowinghowtheneuralsubstratasupportingmentalrepresentationsareshaped (Westermannetal.,2006).

Recentdecadeshaveseenimpressiveadvancesintechniquesforpinpointingthe structuralandfunctionalcharacteristicsofthebrainatdifferentspaceandtime scales,atrestandwhenperformingvarioustasks.Someapproaches,underthe umbrella-term neuro-emergentism,addressdevelopmentalconcernsbymeansof imagingprocedurestoclarifythebasesoflanguageandcognitioninthebrain (Hernandezetal.,2019).Ofthese,neuro-constructivismfocusesonfactorsthat impingeontheemergenceanddevelopmentof representations inthebrain—as patternsofneuralactivationthatcontributetotheindividual’sadaptivebehaviorin theenvironment.Thismeansthatdevelopmentofneuralsystemsisconstrainedby multipleinteractingfactors,bothintrinsicandextrinsic,thataffectthedeveloping organism(Westermannetal.,2006).

Althoughcastinadifferentterminology,thisconceptualframeworkechoesa majorthemeoftheSwissepistemologistJeanPiagetbackin 1936,thatcognitive development—thedevelopmentof intelligence inPiagetianterms—proceedsas aninteractionbetweenbiologicalendowmentandenvironment(Piaget,1952). ForPiaget,cognitivestructuresareneitherinnatenortheunconstrainedresultof experience;theyareconstructedinteractively.Twobiologicalprocesses,present ineverylivingorganism—assimilationandaccommodation, andtheequilibrium betweenthem—explainbothcognitivegrowthandcognitivestability.

• assimilation istheprocessbywhichanaspectoftheenvironment(aperturbation,anewobject,ornovelsituation,say)isintegrated,combinedwith, orabsorbedintoanexistingscheme(physiological,metabolic,muscular, sensorimotor,perceptual,reflexive,etc.);

• accommodation istheprocessbywhichaschemeorstructure(physiologicalorcognitive)ismodulatedortransformedtosubsumeanasyetnot assimilatedaspectoftheenvironment;

• equilibration istheprocessbywhichagivencognitiveorbiological organization—asaresultofprocessesofassimilationandaccommodation— reachesanewformoforganizationalstability.

Neuro-constructivismrecapturestheinteractionsproposedbyPiaget.Itconceives ofdevelopmentasapathor trajectory shapedbyinteractingconstraintsatdifferentlevelsoftheorganism,fromgenestoculturalsettings.Neuralactivityyields behaviorthatmodifiesthephysicalandsocialenvironment,leadingtonewexperiencesandinvokingnewpatternsofneuralactivity.Cognitivedevelopmentcan

becharacterizedinessenceas mutuallyinducedchanges betweenthebrainand themind.

Thisviewcallsintoquestiontwoideasrootedintwentieth-centurylinguisticsandcognitivescience:David Marr’s(2010) notionofindependentlevelsof descriptionandtheideathatlanguagelearninganduseissupportedexclusively byprespecifiedbrainregionsthatrespondselectivelytoverbalinput.

Marr,aBritishneuroscientistwhoworkedonvision,conceiveditasaninformationprocessingsystemthatcanonlybeunderstoodifanalyzedatthefollowing threelevels:

• computational:whatdoesthesystemdo,whatproblemsdoesitsolve?

• algorithmic(orrepresentational):howdoesthesystemdowhatitdoes,what representationsdoesituse,andwhatprocessesdoesitemploy?

• implementational(orphysical):howisthesystemphysicallyrealized,what neuralstructuresandactivitiesimplementthesystem?

Marr’slevelsofanalysisunderliethecommondistinctionbetweenbehavioral, psychological,andbiologicallevelswhich,inmarkedcontrasttoaneuroconstructivistview,haspermeatedthestudyoflanguagedevelopmenttothis day.

In 2012,thirtyyearsafterthepublicationofMarr’s Vision,hiscoauthorTomaso Poggioaddedtwofurtherlevelstoexplainhowprocessingsystemsfunction:a leveloflearninganddevelopmentandalevelofevolution. Poggio(2012) argued thatitisnotenoughtoknowhowtransistorsandsynapseswork,andwhichalgorithmsareusedforcomputations;wealsoneedtounderstandhowachildcan learnthealgorithmsandhowtheselearningmechanismsemergedinthecourse ofevolution.Developmentintheindividualandevolutioninthespeciesmust bothbetakenseriouslytounderstandthefunctioningofend-stateorganisms,or ofanyprocessingsystemforthatmatter.

Thesecondideathatisqueriedbyneuro-constructivismisofspecificareasof thebrainthatsupportlanguage.Fromaneuro-constructivistview,circumscribed regionsofthebrainhaveabiologicallydetermined readiness toprocessacertain input(inthiscaselanguage)ratherthanafixedprespecifiedfunction(Elsabbagh &Karmiloff-Smith,2006).Withdevelopment,thankstointeractionwithspecific inputs,thisinitialreadinessbecomesincreasinglyspecialized.Again,development isnecessarytounderstandanend-state,inthiscase,thespecializationofcortical regionstoperformaparticularfunction.

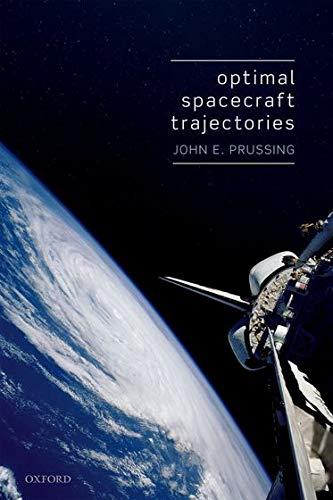

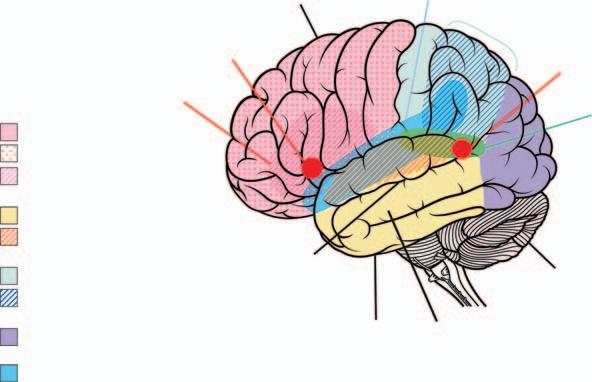

Belowwediscusstheanatomicalandfunctionalpropertiesofourinformation processingsystemandillustratehowthesepropertiesmayvarydevelopmentally. Figure 1 displaysthebrainsiteswementionintherestofthischapter,asdetailed inGlossaryIandII.

CEREBRAL CORTEX

Lateral view of the Left Hemisphere

Area

Inferior Frontal Gyrus

FRONTAL LOBE

Perfrontal Cortex

Inferior Frontal Cortex

TEMPORAL LOBE

Superior Temporal Gyrus

PARIETAL LOBE

Posterior Parietal Cortex

OCCIPITAL LOBE

Perisylvian Region

Figure1 Majorlanguage-relatedsitesinthehumanbrain.

Wernicke’s Area

Temporoparietal Junction

Source:Figurecreatedbytheauthors,basedonanimagebyTaleseedum/stock.adobe.com

1.4 Fundamentalpropertiesofthegrowingbrain

Fivedevelopmentalpropertiescharacterizethefunctioningofthebrain: (i)increasingspecialization;(ii)growingcapacityforparallelprocessing;(iii)predictivecapacitybasedonsensory-motorexperience;(iv)hierarchicalorganization forcognitivecontrol;and(v)long-lastingpowerforlearning.Thebrainisnota staticentity,itsprocessingcapacitiesmayvaryacrossshortperiodsoftime(asin primingandrelearning),oracrossthecourseofourlives.Onesuchvariationconcernsthebrain’sdegreeof specialization,sincecertainfunctionsareperformed incircumscribedareasofthebrain.Wehaveseenthatifabrainareareadyto processlanguageisdamagedearlyindevelopment,otherareascancompensate. Overtime,however,thebrain’scorticalareasbecomemorespecializedinthe stimulitheyareabletoprocessandlessaccessibletocompensationfromother areas.9

Alongwithitsincreasingspecialization,thebraindevelopsthecapacitytowork inparallel ondifferentaspectsofthesamestimuli.Thisenablesus,forexample,to attendatoneandthesametimetothesounds,meanings,andgrammaticalfeatures ofwordsandtothecontentoflanguage-driveninteractions.Differentcorticaland subcorticalregionsareactivated,revealingadistributionofworkforlanguageprocessing.This distributedprocessing enablesfunctionalconnectivity,ajointstate ofmultiplebrainelements(axons,neurons,areas,etc.),tosupportataskacross variousbrainregions(Pessoa,2014).

Medial Prefrontal Cortex Perisylvian Region Precuneus

Cerebellum Fusiform Gyrus

Medial Temporal Lobe

Broca’s

Superior Temporal Sulcus

Bothmacroandmicrovariationsinthebrain’sprocessingcapabilitiesaredue tointeractionsthatareatoneandthesametimeinternalandexternaltotheorganism.Memorykeepstrackoftheseinteractionsandimprovesthebrain’s predictive capacity.Itfacilitateshumangoal-directedbehavior,enablingustodetecterrors, improveourpredictions,andmodifyouractions.Everyinteractionbetween organismandenvironmentthroughthesensoryorgansisregisteredinthecerebral cortexassequencesofelectricalandchemicalsignals.Theseimplicitsensory-motor schemas thatthecortexformsacrossthelifespanarethebasicbuildingblocks ofhumanknowledge(Gilboa&Marlatte,2017).10 Eventhemoreabstractand explicithumanabilities(likecreatingmathematicalmodelsorconstructinglinguistictheories)stemfromtheseearlyandlessexplicitformsofsensory-motor organization.Thecortexis hierarchicallyorganized,withsomeregionscontrollingothers.Controlisexertedbi-directionally:top-downfromthegoalorexpected stateofaffairstotheactionsandperceptionstheserequire,and bottom-up from sensoryinputstothesesameactions,perceptions,andanticipatedgoals.These respectively feedforward/feedback processesenableourbraintominimizeerrors ofpredictionandfacilitatereachingourgoals.

Finally,justifyingthescopeofourinquiry,thecapacitytolearnandmemorize, andtopredictandcorrecterrors,remainsplasticatleastthroughandpossibly beyondlateadolescence.This plasticity provideslong-lastingopportunitiesfor experiencetoshapedevelopment.

Belowweportraytheworkingbraininthelightofthesefivefacetsofits functioning.

1.4.1 Increasingspecialization

Theyear 1835 sawthetranslationintoEnglishofFranzJosephGall’s OntheFunctionsoftheBrainandofEachofItsParts:WithObservationsonthePossibilityof DeterminingtheInstincts,Propensities,andTalents,OrtheMoralandIntellectual DispositionsofMenandAnimals,bytheConfigurationoftheBrainandHead.

Thelongtitleisself-explanatory.Theatlasofthebraintracedby Gall(1835) containedthirty-seveninstincts,propensities,andtalentslocalizedfollowingthe bumpsandunevengeographyofthehumanskull.In1861,PaulBrocaidentified aregionofthebrainthatservestoarticulatespeech.Subsequently,CarlWernicke detectedthepartresponsibleforreceptivespeech,andGustavFritschandEduard Hitzigdiscoveredthatstimulatingdifferentpartsofthecerebralcortexproduces movementindifferentareasofthebody.

AvastgulfseparatesGall’sphrenologicalapproach,basedonthesurfaceshape oftheskull,andBroca’sapproachfromtheinside,basedonpostmortemautopsiesofindividualssufferingfromspeechimpairments.Gall’smethodlednowhere, whereasBroca’sfurnishedthefirstanatomicalproofofthelocalizationofbrain function,andremainstothisdaythemostpopularmethodforinquiringintothe

relationbetweenbrainandbehavior.Bothapproachespavedthewayto theories oflocalization,counteringthethenacceptedviewofbrain equipotentiality proposedbyKarlSpencer Lashley(1950) thatallareasofthebrainareequallyableto performagiventask.

TheviewsofearlyneurologistslikeBrocaandWernickeprovidedanundisputedmodelforthelocationoflanguageinthebrain.Itlocatedhumanlanguage intheleftcortexaroundtheSylvianfissure,withWernicke’sareaintheleftsuperior temporalgyrusheldtoberesponsibleforcomprehensionofspeech,andBroca’s areaintheleftinferiorfrontalgyrus(lIFG)tosupportlanguageproduction.Inthis divisionoflaborbetweenthefrontalandtemporalregions,thearcuatefasciculus wasseenasconnectingthetwoareas.

Morerecentbehavioralstudiesshowthatthecortexstartsouthighlyinterconnectedintheyounginfant,andthatlocalizationandspecializationofbrain functionoccuronlygradually(Huttenlocher&Dabholkar,1998; Johnson,2001). Increasingspecializationmeansagrowingselectivityoftheregionsperforminga particularfunction.Ascogentlydepictedin Karmiloff-Smith’s(2009) metaphor, “oneversionofevolutionarypsychology…maintainsthatthehumanbrainhas evolvedintotheequivalentofaSwissarmyknifeinwhicheachinnatelyspecifiedmoduleisexquisitelyadaptedforeachspecific,independentfunction….(The analogyignoresthefactthatmostusersoftheSwissarmyknifeactuallyemployfor allpurposesonlyafewofthenumerousspecial-purposetools)”(p.56).Inthecase oflanguage, lateralization indicatesaspecializationofstructuresintheleftrather thantherighthemisphere—likeprocessingutterancessaidoutloudorcopyinga writtenpassage.LanguageispredominantlyprocessedbytheLHinmostrightandleft-handedpeopleearlyinlife.11 Evenbreastfedbabiesactivateperisylvian brainareasintheLHwhenlisteningtotheirmothers’speech(Dehaene-Lambertz etal.,2002).Thissuggeststhattheinfantcerebralcortexhasalreadydifferentiated functionalareas,oneofwhichisreadyforlanguageperception.Innewborns,as inadults, listeningtospeech activatesasetoftemporallobeareasmainlyinthe LH.Yetadulthoodrevealsadevelopmentalshiftinfunctionalconnectivity,with increasinglateralizationtoLHpredominance.Childrenshowastrongconnectivity between hemispheres,mainlyamongsuperiortemporalregions,whereasin adultsconnectivityisstronger inside theLH,betweenthefrontalandtemporal regions(Friedericietal.,2011).

Thechangefrombilateraltowardincreasinglylateralizedrepresentationapplies tospeaking,too.Imagingstudiesfromchildhoodtoadolescencerevealchanges fromabilateraltoanincreasinglylateralizedrepresentationinthepremotorarea oftheprefrontalcortex(PFC)(Hollandetal.,2001; Lidzbaetal.,2011).Importantly,themajorchangesinlateralizationoccurinthecaseofmorecomplextasks likestoryprocessingthataremasteredinmiddlechildhood.Studiessuggestthat, althoughsomedegreeofhemisphericspecializationispresentinyoungerchildren, itislesswelldefinedthanlaterinlife(Vannestetal.,2009).Further,improved

linguisticabilitiesareassociatedwithincreasedlateralizationoflanguagefunctionsintheLH.Forexample,betweenages7and12years,bettersyntacticskills arerelatedtoanincreaseinlIFGactivationandadecreaseinrightinferiorfrontal gyrus(rIFG)activation(Nuñezetal.,2011).

Topinpointthesignificanceofbrainlateralization,someresearchershaveproposeda‘lateralityindex,’measuredasthedifferencebetweenthenumberof activatedpixels(unitsofspecialresolution)intheLHandRHdividedbythetotal numberofactivatedpixels.Computationsindicatethatthecognitivefunctionwith thehighestlateralizationindexesintheLHislanguage(Schmidtetal.,1999).The increasedlateralizationoflanguageintheLHwithagecorrelateswithgrowing myelinationofthecorpuscallosum(CC),aconnectingstructureofthetwocerebralhemispheres.Thesizeofthecorpuscallosumincreasesuptothemid-20swith amorerapidgrowthrateintheearlyyearsandslowergrowthinsubsequentyears (Pujoletal.,1993).TheCCplaysanimportantroleinskilledreadinganddevelops differentlyinliterateversusilliterateindividuals,demonstratingthatliteracyisa factorinbrainlateralization(seeChapter 7).

Insum,brainactivationduringlanguageusemovesfrombilateralearlyinlife tounilateral,predominantlyleft,inyoungadults.Thisasymmetricorganization ofthebrainismodifiedbyexperience,withgreaterLHlateralizationforlanguage anindexofmaturation.

Why,indefaultcircumstances,doesoneregionandnototherstakeoncertain functions?Littleisunderstoodaboutthisissue.Inthecaseofauditoryspeech, nervecellsintheareasituatedontheSTGhavemoresynapsesintheleftthanin therighthemisphere;butwhythisasymmetry?Mostofthewiringinthebrain isspecifiedbygeneticprograms,yetitsfinalwiringalsodependsonsensory informationfrominputduringearlychildhood.Arguably,innormalcircumstances,Broca’sareamaybecomespecializedforlanguageprocessingnotbecause itisspecificallydesignedforlanguage,but,inpartatleast,becauseitpossesses computationalpropertiesparticularlysuitedtodealingwiththedomain(Elman etal.,1996).Thus,adomain-relevant regionbecomesdomain-specificoverdevelopmentaltime(Karmiloff-Smith,1998).Itmayinitiallycompeteforprocessing certaininputs,butitsparticularcomputationalpropertieswillultimatelytake over.Thatis,specializedbrainnetworksaretheemergentoutcomeofprogressively changingprocessesthatinteractdynamically,withenvironmentalinputovertime eventuallygivingrisetothefullystructuredadultbrain.

Experience-dependent plasticity appearstobeahallmarkofthehumanbrain. Butthisdoesnotmeanthattheneonatebrainisablankslatewithnostructure;nordoesitmeanthatanygivenpartofthebraincanprocessanyinputs. Thesetwoinsightsareparticularlyrelevanttoourconceptofdevelopmentsince, innon-pathologicalsituations,whilebrainregionsbecomeprogressivelyspecialized,somemaybecome repurposed inthecourseofdevelopment(Wolf,2018). Thishappensinlearningtoreadandwrite,whenregionsgeneticallydesignedfor