Introduction

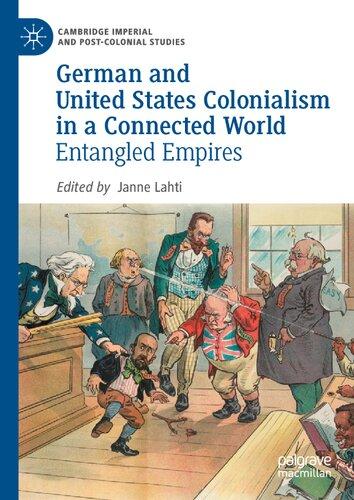

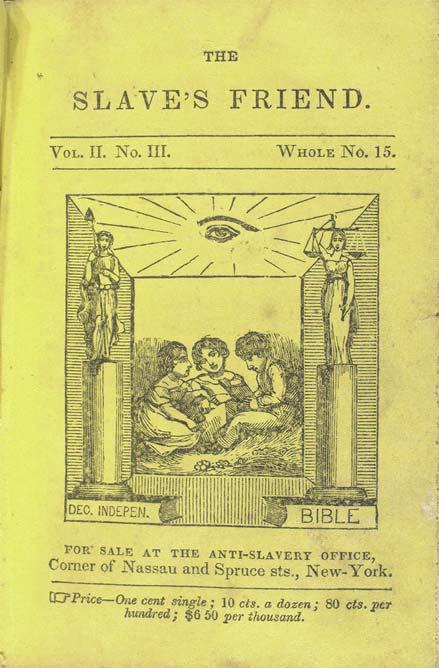

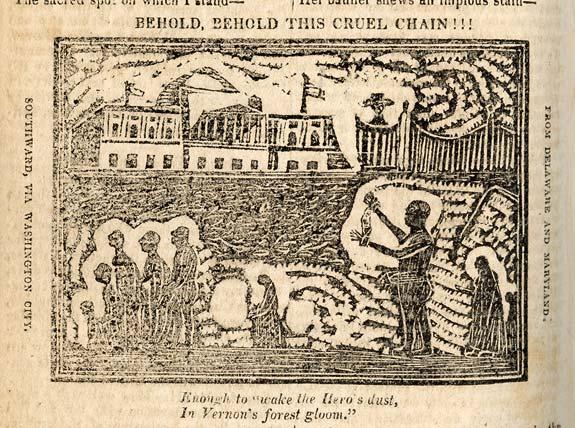

IntheFebruary1837issueof TheSlave’sFriend, theeditorsreportedthatthe magazine’soriginalfrontispiece,“agoodmanteachingaschool,wasnearly wornout”andhadbeenreplaced.Inthenewfrontispiece(seeFigure I.1),the editorsexplained,“Youseethreelittleabolitionistsaresittingdown,whileone ofthemisreadingtotheothers.OnonesideisacolumnwiththefigureofJusticeonit,andontheothercolumnisthefigureofLiberty.YoucanknowJustice bythescales,andLibertybythecap.”1 PublishedbytheAmericanAnti-Slavery Societyfrom1836to1839, TheSlave’sFriend wasanabolitionistperiodical aimedatchildren.2 Despitetheperiodical’sdidactictone,theeditorsneglect tomentionperhapsthemoststrikingfeatureofthenewfrontispiece:theeye floatingabovetheentirescene.ThisimageoftheEyeofProvidenceisafamiliarone,appearingonthereverseoftheGreatSealoftheUnitedStates,on modernone-dollarbills,andinthesinisterlogooftheUSInformationAwarenessOffice.3 IntheSlave’sFriendfrontispiece,God’sall-seeingeyepresumably watchesovertheyoungabolitionists,observingtheirgoodbehavior,yetthe artisthasrenderedtheeyelookingdirectlyatthereader,notdownatthe childrenbelow.Thisiconofdivinesurveillancethusdisciplinesthereader, remindinghimorherthatnosecretisconcealedfromGod’seye.4

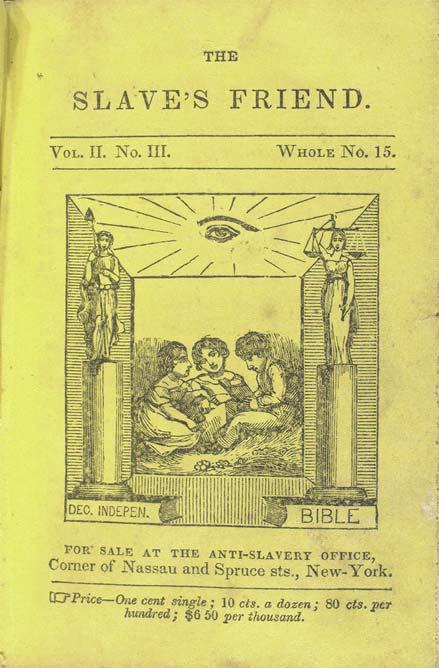

WhereasGod’seyewatchesfromabovein TheSlave’sFriend’sfrontispiece, theNovember1823issueofanotherearlyantislaveryperiodical, Genius ofUniversalEmancipation, includesanimageof“sousveillance”—aconcept developedbySteveManntodescribewatchingfrombelow.5 Thelowertwothirdsofthiswood-blockprintdepictsaslavecofflebeingmarchedpastthe USCapitolbuilding,whichoccupiesthetopthirdoftheframe(seeFigureI.2). Becausetheartisthascompressedtheforegroundandbackground,itappears thattheenslavedpeopleareliterallyunderground.Thisimagejuxtaposestwo looks:thesupervisorygazeofamaninablackhat,whomtheaccompanyingtextidentifiesasa“member[]ofCongress,”andtheresistantlookofthe enslavedmanliftinghiseyesandhismanacledhandstowardtheCongressionaloverseer.6 AsTeresaGoddupointsout,“thestandingslave,despitethe coarsenessoftheimage,hasanidentifiableeye…[that]look[s]uptowardthe promiseoffreedomonthehorizon.”7 BycommandingtheCongressmanto “Behold,behold,thiscruelchain”(thecaptionabovetheimage),theenslaved mandirectsthewhiteoverseer’sgazetofocusonhisfetters.Drawingattention

Fig.I.1 SchomburgCenterforResearchinBlack Culture,Manuscripts,Archives,andRareBooks Division,TheNewYorkPublicLibrary.“Three childreninatemple.” TheNewYorkPublicLibrary DigitalCollections. 1837.FromTheNewYorkPublic Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ 510d47da-7554-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

totheenslavedman’seyeandhandsbysurroundinghisupperbodywithwhite spaceandmakinghimthelargesthumanfigureintheillustration,theartist portraysthemanasanactiveagent,lookingbackatthegovernmentthatpermitstheinstitutionofslaveryandprotestinghiscaptivity.If TheSlave’sFriend encourageditsreaderstointernalizeGod’sall-seeingeyeasamonitortoshape theirbehavior, Genius embodiesanoppositionallookinthefigureofaBlack manwhodefiantlychallengestheracializedsurveillanceofAfricanAmericans.

Fig.I.2 “Behold,BeholdThisCruelChain”; GeniusofUniversal Emancipation (1821–1839),Vol.3,Iss.7(Nov1823):4(misprinted as68inoriginal).CourtesyofOberlinCollegeArchives,Oberlin, Ohio.

AstheillustrationinGeniusindicates,untiltheopencombatoftheCivilWar theconflictbetweenenslaversandenslavedpeoplewaswagedprimarilyvia methodswenormallyassociatewithsurveillance.WhereasthetitleofMichel Foucault’sfoundationalworkonsurveillance, SurveilleretPunir,isusually translatedintoEnglishas DisciplineandPunish,theexaminationofracializedsurveillanceintheantebellumslavesystemthatthisstudyundertakes remindsusthat surveiller literallymeans“tooversee.”Theoverseer’spanopticaleyewatchingthefieldtokeepeveryoneworking,biometricdataadvertised inrunawaynotices,slavepatrollers’searchesofslavecabinstofoilincipientrebellion:theseexamplesofsurveillanceindicatethecontextofvisibility shapingenslavedlives.Surveillance,however,wasmutual:justasoverseers werewatchingenslavedworkers,theworkerswerewatchingthem,learningto detectanypatternsofbehaviorthatmayeventuallyproveusefulinday-to-day resistanceaswellasinlargeractsofinsurrection.Insistingonrace’scentrality tosurveillancetheory,SimoneBrownehasidentifiedthisfacultyofdetection as“darksousveillance.”8

Informedbythisdialecticofracializedsurveillanceandsousveillance,Slavery,Surveillance,andGenre tracestheemergenceofanantebellumliterature

ofsurveillancethatincludesmultiplegenres,fromslavenarrativesandthe AfricanAmericangothictocriminalconfessionsanddetectivefiction.The genresconstitutingthisliteratureofsurveillance,Icontend,allengagewith asociallyandhistoricallyspecificconflict:theracialpowerdynamicsofthe antebellumslavesystem.RecentgenretheoristsincludingWaiCheeDimock, JeremyRosen,andTravisM.Fosterunderstandgenrenotasastatictaxonomybutasafluidsetofconventionsthat“makevisiblethesocialfunctions ofliterature,theroleofliteraryformsinarticulatingbroadersocialandideologicalformations.”9 Oneofthekeycontentionsofthisnewgenretheory isthatgenreschangeovertime:“Aesthetic,formal,andthematiccharacteristicsbecomenewlyfamiliargenericgroupingswhentheyfulfillafunction fortheirparticularpresentandtheirparticularaudience,fadingoncethat functionlosesitsurgency.”10 Thetaskofgenreanalysis,then,istoidentifytheseconstellationsofcharacteristicsandexaminethefunctionsthey fulfill.

ThenarrativegenresIanalyzeshareathematicconcernwiththesurveillanceofracializedbodiesandformalexperimentationwithwhatIcall“modes ofdetection”(waysoftellingastoryinwhichcertaininformationiseither renderedvisibleorkepthidden).11 Eachgenreturnsthosedynamicstodramaticallydifferentends,however.Forexample,whereasslavenarrativesilluminatesubversivepracticesofsousveillancetochallengetheslavesystem’s pretenseoftotalsurveillanceandtoadvocateforpoliticalandsocialchange, detectivefictioncreatesafantasizedwhitefigureofnonreciprocalsurveillanceinresponsetothethreatofsousveillance,likeEdgarAllanPoe’sDupin. WhiteauthorsaswellasBlackauthorstakeuptheseissuesintheirwriting, thoughtheirrepresentationalgoalsdifferwidely—fromcalmingwhitefears ofenslavedrebelliontoabolishingslavery.12 Althoughitmayseemcounterintuitivetocollocateinthesamestudygenreswhoserhetoricalfunctionsare atsuchmarkedcross-purposes,Idosobecausetheycollectivelydemonstrate theantebellumperiod’sprevailingconcernwiththeagencyandmobilityof Blackpeople.Theliteratureofsurveillanceisa“fieldofassociation,”asAlastair Fowlerproposesweshouldconceiveofgenre,andbycomparativelyexaminingthegenreswithinitIamtakingtoheartJohnFrow’sclaimthatgenres“are neitherself-identicalnorself-contained.Eachgenre’sformisrelativetothose ofallothergenresinthesamesynchronicsystem,anditchangesasthatsystem evolves.”13 Thismethodologyenablesustoperceivetheliteraryfunctionsthat sousveillanceanddetectionperformedfordifferentantebellumauthorsand readingpublicsaswellasthewaysthesegenrescross-fertilizedoneanotherin surprisingways.

Criticsoftheolder,prescriptivemodelofgenrefrequentlyemploythe metaphorofthe“genrepolice”toindicatethat“genreisanagentofsocial domination,”inBruceRobbins’sphrase.14 Genre,onthismodel,isahierarchicalsortingsystem,witharbiterswhodecidewhatbelongsandwhatdoes not.Toputthisconceptintotermsmorepertinenttomyproject,then,the traditionalmodelofgenreisaformofsurveillanceakintoOscarGandy’s “panopticsort”:theprocessesbywhichdataisamassedandusedtoidentify, classify,andcontrol.15 WhileIsharethesecritics’senseoftheflawswithinthis authoritarianmodelofgenre,Icontinuetothinkthatgenrerevealsimportant dimensionsoftherelationshipamongauthors,texts,andreaders.Recentgenre theoryencouragesscholarstoinvestigatethe“functionofagenericforminits institutionalcontexts,illuminatingtheactionsofvariousinstitutionalagents andthecontestedvaluesthatshapethefieldsinwhichtheyact.”16 Ratherthan enforcinggenrecategoriesasatoolfornormativeclassification,Iusegenre analysistoilluminatethedifferencebetween,forinstance,fugitiveslavenarrativespublishedinthe1820sand1830s,beforetheriseoftheinstitutional abolitionistmovement,andthosepublishedinthe1840sandafterward.The laternarratives,asmanyscholarshaveshown,wereshapedbytheabolition movement’srhetoricalandpoliticalagenda,whichframedenslavedpeople’s storiesasevidencefortheprosecutionofthecaseagainstslavery.17 Theearlierfugitiveslavenarratives,Iargue,takeupothergenericconventionsbesides eyewitnesstestimonytocrafttheirstories.Oftenpublished“forthebenefitof” thenarrator,andthusmorefocusedontheidiosyncraticcontoursofanindividual’sexperiencethanoncompilingrepresentativeproofofslavery’scruelty, these1820sandearly1830snarrativesuseespionagetropestopresenttheindividualasanactiveagentwithexpertiseaboutslavery’ssurveillancesystem. Thisexampledemonstrateshowinstitutionalcontextsstructurethesituations towhichauthorsrespondandhowthesecontextschangeovertime,thereby modifyingthefunctionofgenericforms.

Inkeepingwiththisnonauthoritarianapproach,Iattendtothewaysthat thesegenresareemergingandtransforming,andparticularlytohow“[t]extual procedurescirculateacrossculturalgenres.”18 ForRosen,“Anaccountthat doesnottrytoreducethecomplexityofahistoricalphenomenondemands acknowledgmentofitsunstablebordersandoverlapwithothergenres.”19 All ofthetextsIstudy,centrallyconcernedastheyarewiththeconflictbetween racializedsurveillanceandsousveillance,experimentformallywithwaystotell storiesthatrendercertaininformationvisibleorinvisible.Tropesofespionage, captivity,secrecy,andrevelationthatcharacterizeearliergenres,primarily gothicnovels,aretransformedwhentheyareusedtoshapenarrativesabout

fugitiveenslavedpeople,forwhomcriminalitywastheonlysociallyrecognizedformofagency.Whenfugitiveslavenarratorsusethesetropesto describethecrimeof“stealingthemselvesaway,”thesetropesbecomestrongly associatedwithcrimeandpunishment.Fugitiveslavenarrativesthusanticipatewhatlaterbecomerecognizedasconventionsofthedetectivenovel.Itrace themigrationoftheseconventionstoPoe’sfictionsofdetectionandbeyond, asvariousantebellumauthorstakeupthemodesofseeing,beingseen,and avoidingbeingseenthatstructurefugitiveslavenarratives.HermanMelville’s andFrederickDouglass’snovellasabouthistoricalslaverebellionstoldfrom theperspectiveofwhitesurveillantsdramatizethedisillusionofwhiteoversight:thefantasyofwhiteinvisibilitythatsousveillancepunctures.Harriet Jacobs’sandHannahCrafts’snovelizedautobiographiesharnessthepowerof surveillancetoenvisionanopenfuturefortheirprotagonists,therebyreversingthecustomarytemporalityofthegothic,withitsemphasisonhowthe pasthauntsthepresent.Bringingtogetherthesemultiplegenresofantebellumliterarysurveillance,thisprojectdemonstratesslavery’scentralitytothe developmentofcrimeliterature.

RacializedSurveillanceandSousveillanceinthe AntebellumUnitedStates

In DisciplineandPunish,FoucaultsituatestheshiftfromspectacularpunishmenttodisciplinarysurveillanceinParisandotherEuropeanmetropolisesat theturnofthenineteenthcentury.Becausemetropolitanpoliceforcesdevelopedonlyinthemid-nineteenthcenturyintheUnitedStates,thesurveillant penaleconomyhasseemedalatearrivalintheUnitedStates.20 Theovervaluationofthecityhasled,howeverinadvertently,totheundervaluationofthe plantationasakeysitefortransformationinUSpunishment.AsBryanWagnerhasshown,however,intheBritishcoloniesand,later,theUnitedStates, enslavedpeoplewereregulatedandcontrolledbythepolicepowerlongbefore thecreationofthe“police”asa“specificdepartmentchargedwithstoppingor detectingcrime.”IntheBritishcoloniesandtheUnitedStates,Wagnerstates, slavelawswere“policemeasures…concernedwiththeslave,firstandforemost,asapotentialthreat”thatrequiredsocietytoinvokethepolicepoweras self-defense.Moreover,undertheslavesystem,“thepowertopolicewasconsiderednotasastateprerogativebutasaracialprivilegeofallwhitesover allblacks,slaveorfree.”21 UnlikethetransitionfrompunishmenttodisciplinethatFoucaultidentifiesinearly-nineteenth-centuryEurope,however,

thebiopoweroftheUSslavesystemalwaysreliedonbothphysicaland disciplinarycoercion—onesupplementingtheother.22 NicholasMirzoeffhas tracedthehistoryofimperialism’sauthorizinggaze,whichhecallsvisuality, arguingthatits“firstdomainsweretheslaveplantation,monitoredbythe surveillanceoftheoverseer,operatingasthesurrogateofthesovereign.This sovereignsurveillancewasreinforcedbyviolentpunishmentbutsustaineda moderndivisionoflabor.”23

Theplantationhascontributedanunappreciateddiscourseofdetectionand policing,primarilythroughtheramificationsofsousveillance.Longbefore thenorthernUnitedStatesestablishedpoliceforces,thesoutherncoloniesof BritishNorthAmericaand,subsequently,thesouthernUnitedStates,relied onthepolicepower(intheformoftheoverseer,slavepatrols,slavecatchers,andmanyotherformsofoversight)tocontrolandrecaptureenslaved AfricanAmericans.24 Beyondthescopicrealm,racializedsurveillancetechnologiesintheantebellumperiodincluded“negrodogs,”identitydocuments, andbiometrics.25 Thoughthesenineteenth-centurytechnologieshavebeen digitizedandnetworkedintheageofdataveillance,thecontinuityofpracticesisremarkable.Electronicsniffermachineshavesupplementedtrained bloodhounds,buttheextensionofhumansensorysurveillance,whethervia biotechnologyormassspectrometry,remainsakeywayofmonitoringand controllingbodies.26 Thewrittenpass(and,later,badge)systemwasaninformationtechnologythatfacilitatedthe“surveillanceofblackbodiesbyway ofidentitydocuments.”Brownearguesthat“thetracking,accounting,and identificationoftheracialbody,andinparticulartheblackbody…forman important,butoftenabsented,partofthegenealogyofthepassport.”27 Brandingandscarringfromcorporalpunishmentweretwoofthemostwidespread waysthatenslaversmarkedthebodiesofAfricanAmericans.Thesemarkers were,inturn,usedtoidentifyenslavedAfricanAmericansinsuchdocuments asslavepasses,cargoinventoriesofslaveships,truancyandrunawaynewspapernotices,wantedposters,andplantationledgers.Thedetailedbiometric descriptionoffugitivesinrunawaynoticesconstitutesthetechnologyofvisual identificationanddocumentationintheprephotographicage.28

Furthermore,longbeforetheadventoftheinternet,antebellumslavecatchersreliedonacommunicationnetworkthatincludedplantationowners, overseers,“boatcaptains,mates,companyofficials,jailers,sheriffs,constables, andotherslavehunters.”29 Enslaversandtheiragentsusedthiscommunication

systemtosharenewsofescapees,towarnotherstobeonthelookoutfora particularrunaway,andtorequestinformation.Theyalsocultivatedastableofinformersanda“corpsofspies,”asJohnPope,sheriffofFrederick, Maryland,putitin1855.30 DrawingananalogybetweentheUnderground RailroadthathelpedfugitivesescapetofreedomintheNorthandthe“reverse UndergroundRailroad”thatkidnappedAfricanAmericansintheNorthand traffickedtheminto(orbackinto)slaveryintheSouth,RichardBellasserts “Participantsinbothnetworksreliedonfalsedocuments,fakeidentities,and disguiseandundertookconsiderablelegalandphysicalrisktotravelundetectedandundisturbedovervastdistances.…AfricanAmericansoccupied front-linepositionsinbothtraffickingnetworks,moresothanhascommonly beenacknowledged.”31 Southernerscontinuedtorefineandstrengthenthis systemuntiltheCivilWar;and,asDouglasBlackmonhasshown,itpersisted undernewterminologylongafterthewar’send.Moreover,thankstotheFugitiveSlaveActsof1793and1850,Southernstatesensuredthattheirracialized policesystemcouldoperatethroughoutthenorthernUnitedStatesandthe Westernterritories.

Racializedsurveillancehaddifferenteffectsforenslavedwomenand enslavedmen.Historianshavedistinguishedbetweenthemore“contained” natureofenslavedlaborforwomen,“whowereheldmorefirmlythanmen withinplantations,”andthe“somewhatmoreelastic”natureoflaborfor enslavedmen,whowereassigned“theworkthatprovidedopportunitiesto leavetheplantation.”32 Therelative“elasticity”ofmen’slaborgavethemgreater familiaritywiththesurroundinglandscape,includingplacestohideandroutes toescape.Women’s“containment”ontheplantationorwithinthehome madethemsubjecttopervasivescrutiny.Inparticular,enslavedwomenwho workedasdomesticsratherthaninthefieldwereinescapablyundertheeye ofwhitesupervisors.Describingtheconditionofenslavedwomanasone of“hypervisibility,”SaidiyaHartmanstressesthat“Withintheprivaterealm oftheplantationhousehold,[theenslavedwoman]wassubjecttotheabsolutedominionoftheowner.”33 AsJacobsdemonstrates,thisscopicdominion encompassedsexualabuseaswellaspoweroverlaborandmobility.

Racializedsurveillanceandsecuritymeasuresintheantebellumperiod cannotbeadequatelyaccountedforbyfocusingontop-downsurveillance, however.Recenttheoriesofsurveillance,particularlyBrowne’swork,have providedadialecticalmodelforanalyzingthereciprocityofwatchingfrom aboveandbelowintheantebellumslavesystem.34 Brownepositionsrace atthecenterofsurveillancestudies,examiningthe“interrelated…conceptualschemesof…racializingsurveillanceanddarksousveillance.”Dark

sousveillance,forBrowne,includes“notonly…observingthoseinauthority (theslavepatrollerortheplantationoverseer,forinstance)butalso…[using] akeenandexperientialinsightofplantationsurveillanceinordertoresistit.”35 Whileenslaversaimedforandoftenimaginedtheirsurveillancetobepanoptical,sousveillancefalsifiesthisfantasy.AsFoucaultsoinfluentiallydescribes it,“ThePanopticonisamachinefordissociatingthesee/beingseendyad: intheperiphericring,oneistotallyseen,withouteverseeing;inthecentral tower,oneseeseverythingwithouteverbeingseen.”36 Byconcentratingon thepracticesandinsightsofthosewatchingfrombelow,mystudydemonstratesthatsurveillantsarenottheunseenobserversinthecentraltowerbut arethemselvestheobjectsofscrutiny.

Incontrasttotop-downsurveillanceaimedatmaintainingwhitewealth andcontrol,sousveillancepracticedbyenslavedmenandwomenwasnecessaryforsurvivalunderthedehumanizingslavesystem.Covert“daytoday resistance,”likeworkslowdowns,sabotage,andtruancy,challengeddominationwithoutriskingone’ssurvival.37 Inthisway,thesemethodsresonate withthestrategicinvisibilitythatJasmineNicholeCobbhastheorizedasa tacticBlackpeopleusedtosubvertandunderminethevisuallogicsofslavery.38 AsIdemonstrateinChapter 1,slavenarrativesfromthe1820sand 1830sarefullofexamplesofenslavedsousveillance,notonlyduringescape attemptsbutalsowithinthecontextofdailylife.Enslavedpeoplespied, eavesdropped,andsharedinformationtocreateopportunitiesforreligious practice,toprotectthemselvesandothersfrompunishment,andtoslipaway tovisitlovedones,amongahostofotherreasons.Theycovertlyalertedother enslavedpeopletodangerthrough“counterveillancesongs,forexample,the folktune‘Run,Nigger,Run,’whichwarnedofapproachingslavepatrols.”39 Althoughresearchhasfocusedonextraordinarysituationssuchasescapes andinsurrections—becausethosearebetterdocumentedthanmundanelife— readingtheliteratureofslaveryandabolitionthroughasousveillancelens revealshowthoroughlyandconstantlyenslavedpeoplewerewatchingfrom below.

Occasionally,enslavedmenandwomenengagedinopenopposition,sometimesevenviolentrebellion,thatexplicitlydisputedthepremisesoftheslave system.Thesemomentsofrupturerevealtheillusorynatureofthedominant group’sstabilityandsecurity.Coordinatedresistancelikeinsurrections(which IdiscussinChapter 3)andtheUndergroundRailroaddependedonsousveillanceaswellasoninformalcommunicationnetworkssuchasthegrapevine telegraph.40 AnearlyhistorianoftheUndergroundRailroad,whowashimself aconductor,assertedin1915that“theAnti-SlaveryLeagueoftheeast…hada

detectiveandspysystemthatwasfarsuperiortoanythingtheslaveholdersor theUnitedStateshad.”41 Heportraysrailroadagentsasundercoveroperatives, explaining

Theybelongedtoanyandallsortsofoccupationsandprofessionsthatgave themthebestopportunitytobecomeacquaintedandmixwiththepeopleand gainaknowledgeofthetraveledwaysofthecountry.…Thesespieswereloud intheirpro-slaverytalkandwereinfullfellow-shipwiththosewhowerein favorofslavery.Inthiswaytheylearnedthemovementsofthosewhoaided theslavemastersinhuntingtheirrunawaysandwereenabledoftentoput themonthewrongtrackthushelpingthosewhowerepilotingtherunaways toplacethembeyondthechanceofrecapture.42

WilliamStill,whose1872historyoftheUndergroundRailroadremainsa vitalsource,observesthatoneUndergroundRailroadoperativespecialized incounterintelligence:“Sometimestheabolitionistsweremuchannoyedby impostors,whopretendedtoberunaways,inordertodiscovertheirplans, andbetraythemtotheslave-holders.DanielGibbonswaspossessedofmuch acutenessindetectingthesepeople,buthavingdetectedthem,henevertreated themharshlyorunkindly.”43 ReflectingontheUndergroundRailroadat theendofthenineteenthcentury,thesechroniclersrecognizedtheparallels betweenantebellumfreedomoperativesandthefictionaldetectivesthathad becomeamassculturalphenomenoninthedimenovelsofthepostbellum period,aswellastheirreal-lifecounterparts.

Perhapsthemostwell-knownantebellumliteraryrepresentationofsurveillanceandsousveillanceintheslavesystemappearsinthemostfamousnovelof theera,HarrietBeecherStowe’sUncleTom’sCabin(1852).Stowedepictswhite surveillanceasafusionofofficialpolice,privateslavehunters,andthepublicat large.TheslavecatchersTomLokerandMarks,tippedoffbyHaleyaboutthe valuablefugitiveElizaandhersonHarry,trackhertotheQuakersettlement whereshehasreunitedwithherhusband,George.ThefugitivesfleethesettlementwiththehelpofPhineasFletcher,buttheyarepursuedby“Lokerand Marks,withtwoconstables,andaposseconsistingofsuchrowdiesatthelast tavernascouldbeengagedbyalittlebrandytogoandhelpthefunoftrapping asetofniggers.”44 Although,asIwillpositinChapter 2,PoehasslavecatchersinmindwhenhecreatesthecerebralcharacterofDupinin“TheMurders intheRueMorgue,”Stowe’sslavecatchersareanimalistic;shedescribesthe posseas“hotwithbrandy,swearingandfoaminglikesomanywolves”(168). AlludingtotheFugitiveSlaveLawof1850,whichbuttressedenslavers’power

torecapturefugitivesandmandatedthatNorthernersassistinthiseffortor befined$1,000andimprisonedforuptosixmonths,oneoftheconstables adjuresthefugitivestosurrender,remindingthemthat“we’reofficersofjustice.We’vegotthelawonourside,andthepower,andsoforth;soyou’dbetter giveuppeaceably,yousee;foryou’llcertainlyhavetogiveup,atlast”(170). Infact,LokerandMarksareactingillegally,astheyneitherownElizanordo theyactasherenslaver’sagent;theyplantokidnapher,lieaboutbeingher legalowner,andsellherforahugeprofitinNewOrleans.Kidnappinggangs throughouttheborderstatesprofitedfromtheadvantageousprovisionsofthe FugitiveSlaveLawtowardenslavers’propertyrights,whichmadeiteasyfor slavecatcherstotransportfreeBlacksandescapedslavestotheSouthandsell thembeforeadefensecouldevenbemounted.45

However,Stowealsoportraysthesesurveillants’adversaries,theconductors andstationmastersoftheUndergroundRailroad.AfterElizaandherhusband, George,arereunitedattheQuakersettlement,SimeonHallidayexplainsthat Fletcher,anotherQuaker,“willcarrytheeonwardtothenextstand,—thee andtherestofthycompany.Thepursuersarehardafterthee;wemustnot delay”(123).Georgeisanxioustoleaveimmediately,butSimeonassureshim thatitissafertowaituntildark:“Thouartsafeherebydaylight,foreveryone inthesettlementisaFriend,andallarewatching”(123).Simeon’semphasisonthecommunity’ssousveillance,“all…watching”forslavecatchers,is borneoutbytheextantrecordsoftheUndergroundRailroad’sactivities,as wellasbyfugitiveslavenarratives,whichcontinuallydepictthelife-or-death stakesofwatchingandlisteningfrombelow.Indeed,Fletcherprovesanexpert sousveillantwhodetectsLokerandMarks’splotandensuresthefugitives’ safety.Fletcher,thenarratornotes,wears“anexpressionofgreatacutenessand shrewdnessinhisface…likeamanwhoratherprideshimselfon…keepinga brightlook-outahead”(162).Thisdispositiontobeonthelookoutbearsfruit whenFletcher,hiddeninthecornerofatavernunderabuffaloskin,eavesdropsontheslavecatchers’plans.Fletcherexplainsthathisabilitytogather thisintelligence“showstheuseofaman’salwayssleepingwithoneearopen, incertainplaces,asI’vealwayssaid”(162).ArmedwithFletcher’sinformation,thefugitivessetoutaheadoftheslavecatchersandareabletomounta defensewhentheirpursuerscatchuptothem.Stowe’srepresentationofthe contestbetweenslavehuntersandUndergroundRailroadoperativesdemonstratestheimportanceofsousveillanceinprotectingvulnerablefugitivesfrom enslavers’detection.

Asthisanalysisof UncleTom’sCabin suggests,literaturewasacrucialsite forexploringthesignificanceandconsequencesofaculturecharacterized

byracializingsurveillanceandsousveillance.Thoughsurveillancehasbeen along-standingsubjectforthesocialsciences,therehasbeenasignificant lackofattention,beyondexpertsincontemporaryfiction,tothewaysthat surveillancestructuresliteraryandotheraestheticworks.Recently,inthecognatefieldthatJohannesVoelzhasdubbed“literarysecuritystudies,”scholars includingRussCastronovo,Voelz,andMatthewPotolskyhavebeguntoremedythisimbalancebydevelopinga“criticalpoeticsofsecuritization”that attendstoaestheticworkscreatedbeforethetwentiethcentury.46 Myproject underscorestheimportanceofracetothisemergingfieldbyaddressingthe effectsofsurveillanceonliteraryexpressionintheUnitedStatesduringthe eraofslavery.ThoughindebtedtoBrowne’spath-breakingworkonracialized surveillanceanddarksousveillance,myprojectfurtherrevealsthatthisbinary oppositionbreaksdowninliteraryworksoftheantebellumperiod.Inthese imaginativeengagementswiththereal-lifebiopoliticsofsurveillance,authors upendtheschemaofwhitesurveillantsandBlacksousveillants.Instead,they demonstratehowsurveillanceandsousveillancearetoodeeplyimbricatedto disentangle:racialidentitiescanbemisalignedwithpositionsofpower,the samepersoncanbesimultaneouslyasurveillantandasousveillant,andtechniquescanbelearned,shared,orappropriatedbypeoplewithdiametrically opposedgoals.

ConsiderPoe’s TheNarrativeofArthurGordonPym (1838),inwhichthe whiteprotagonistlearnstosousveilbyexperiencingfugitivityandcaptivity,anexperiencethatneverthelessdoesnotleadhimtosympathizewith theBlackTsalalians.47 Instead,afterPymavoidsbeingmassacredbythe morecunningandingeniousTsalalians,hereliesonsousveillancetoescape withhislife.Grotesquelyinvertingthepowerdynamicsofantebellumracializedsurveillance,Poe’snovelexplorestheefficacyofsousveillancewithout acknowledgingitsethicalimperative.Ontheotherhand,theAfricanAmericanprotagonistsofCrafts’s TheBondwoman’sNarrative (writtenbetween 1853and1860,published2002)andJacobs’s IncidentsintheLifeofa SlaveGirl (1861)areBlacksurveillants,exaggeratingthetechniquesofthe South’soppressivesurveillanceregimeinordertosurviveandresistit.Unlike Poe,theseauthorsareacutelyawareofthelife-or-deathstakesofsurveillance.Thoughtheconceptualframeworkthatdifferentiatessurveillanceand sousveillanceaccordingtothepositionsofpoweroccupiedbytheobserver breaksdownintheliteratureIanalyze,itneverthelesshelpsustoperceivehow antebellumauthorswerevariouslyinverting,destabilizing,andrecombiningthetechniquesofracializedsurveillanceandsousveillanceinprovocative ways.

AntebellumGenresofSurveillance

Acrossfourchapters, Slavery,Surveillance,andGenreinAntebellumUnited StatesLiterature arguesfortheexistenceofdeep,oftenunexamined,interconnectionsbetweengenreandracebytracinghowsurveillancemigratesfrom theliteratureofslaverytocrime,gothic,anddetectivefiction.InChapter 1,I considerslavenarrativesfromthe1820sand1830s,atransformationalperiod duringwhichUSabolitionactivistsbegandemandingimmediate(ratherthan gradual)emancipationanddevelopingnationalinstitutions(ratherthana loosecollectionoflocalgroups).Slavenarrativesfromthesedecades,including MosesRoper’sANarrativeoftheAdventuresandEscapeofMosesRoper (1837) andCharlesBall’s SlaveryintheUnitedStates (1837),increasinglydetailed themechanismsofsurveillancewithintheslavesystem,alongwiththevaried andcreativewaysenslavedpeopleresistedthispervasivesurveillance.With theturninthe1820sfromreligioustolegalisticabolitiondiscourseandthe efforttodefineslaveryasanationalcrime,ex-slavenarratorsandtheireditorsinthe1820sand1830stestedoutdifferentwaystoframetheirnarratives. BuildingonJeannineMarieDeLombard’sargumentthattheslavenarrative genre“was,attimes,coextensive[with]crimeliterature,”48 Ipositthatnarrativesfromthesedecadespositionedtheex-slavenarratorasaspybefore thefamiliar“slaveaseyewitness”tropebecameconventional.Whenweread slavenarrativesthroughthissurveillantlens,wecanperceivetheiremphasis oncrimeandpunishment,evidence,andrevelation:thesameconcernsthat wouldbecomecentraltodetectivefictionadecadelater.

Inthesecondchapter,IpairastoryofdetectionembeddedinBall’snarrativewithPoe’s TheNarrativeofArthurGordonPym andhisDupintales ofthe1840stodemonstratethewaysurveillancemigratesfromslavenarrativestotheemerginggenreofdetectivefiction.Though Pym hasnever beenreadasdetectionfiction,Poeexplicitlyengageswiththeprocessesof investigationanddeductionthroughoutthenovel, aworkthatpredateshis Dupintales,whicharegenerallycelebratedasthefirstdetectivestories.I showthatPoeexperimentsinthenovelwithdifferentmodesofdetection— “conspicuous”and“inconspicuous”—whichdivergeintheirportrayalofthe perspectivefromwhichonedetectsandintheaimsofdetection.Conspicuousdetectiondeflectsattentionfromsystemiccrimesbyatomizingdetection tofocusonanindividualmastermind’snonreciprocalsurveillanceofanindividualcriminal.Inconspicuousdetection,bycontrast,rejectsthepanoptical modelofsurveillanceandrevealstheefficacyofcovert,cooperativesousveillancetoaddresssystemicinjusticessuchasslaveryandcolonialism.Ball’s

narrativeprovidesaharrowingexampleofboththemodeandthelife-or-death stakesofinconspicuousdetection,asBall’sdetectionbothsolvesthecrimeand saveshimfromatorturousdeath.ThoughPoeincreasinglyeffacestheracializedpowerdynamicsofsurveillanceineachsubsequentDupintale,taking intoaccountthefullscopeofPoe’sliterarydetectionrevealshisinitialembroilmentwiththeracializeddynamicsofpower.Ultimately,Poe’sengagement withthecontestbetweensurveillanceandsousveillanceleadshimtocreatethe exemplaryconspicuousdetective:C.AugusteDupin,theconsummatefantasy ofnonreciprocalsurveillance.

Iturnnext,inthethirdchapter,totwonovellasthatdepictthedestruction ofthiswhitefantasyofseeingwithoutbeingseen.Douglass’s TheHeroicSlave (1852)andMelville’s BenitoCereno (1855)bothconcernviolentmoments ofenslavedrevolt,inwhichthe“mask[is]tornaway,”asMelville’snarrator putsit,andsousveillanceismadevisible.Toldfromtheperspectiveofwhite surveillants,notenslavedrebels,thesenovellasdramatizethewhitecharacters’realizationthattheyarenotinvisiblebutthattheytooareobjectsof surveillance.49 Evenastheemerginggenreofdetectivefictionwasimaginingthepotencyofnonreciprocalsurveillance,DouglassandMelvillewere strippingawaythecomfortthatthisillusionofinvisibilityprovidedtowhites. Readingthesenovellasthroughthelensof TheConfessionsofNatTurner (1831),Iexaminehowwhitesurveillants’recognitionofdarksousveillance rupturestextualform.Thedirectexchangeofglancesbetweenwhitesurveillant(ThomasR.Gray)anddarksousveillant(NatTurner)causesGraytolose rhetoricalcontrolofhisaccountoftheSouthamptonslaveinsurrection.In thefirstthreepartsof TheHeroicSlave, Douglassportraysadifferentpath thatawhitesurveillantcouldtakewhenheisconfrontedwiththeexistence ofdarksousveillance.Douglassdramatizesawhiteally’stransformationfrom surveillanttosousveillantashelearnsthetechniquesandethicalobligationof sousveillancefromaBlackfugitive.Inthefinalpart,however,Douglasscontortstheformofhisnovella,abruptlyshiftingtoanewfocalcharacter,the Creole’swhitefirstmate,whonarratesthestoryoftherebellion.LikeGray, thiswhitesailorattemptstomaintainwhitesupremacyevenashedisseminatesastoryofBlackresistance.Similarly,MelvilleregistersAmasaDelano’s resistancetotheimplicationsofdarksousveillancebyabandoningthefree indirectdiscourseofthefirstsectionandpresentingthe SanDominick’shistorythroughthelegaldiscourseofBenitoCereno’sdeposition.Takentogether, theseformalstrategiesdemonstratehowhistoricalnovellasaboutslaverebelliongrapplewiththeproblemoftestimonythatdestroystheformofthe novellaitself.

Ifliteraryrepresentationsofsurveillanceblurthedistinctionbetweensurandsousveillance,thisproductiveconfusionisaugmentedwhenweconsider thegenderdynamicsofwatcherandwatched.Theemphasisonfugitivity, escape,andrevoltthatcharacterizesthefirstthreechaptersofSlavery,Surveillance,andGenre privilegesmaleauthors.ManyscholarsincludingElizabeth Fox-Genovese,StephanieM.H.Camp,andStephanieLihavedescribedhow women’sresistancetoenslavementtendedtoaimatpreservingsocialnetworks ratherthanachievingindividualliberty.50 Liremindsusthatwhile“flightand armedinsurrectionmayprovidetheclearestindicationofresistance,theease withwhichwemayidentifysuchoppositiondoesnotimplyalackofactive insurgencyamongthosewhoremainedinandperhapsevenchosecaptivity.”51 TheelevationofDouglass’s1845Narrative,whichpresentsaheroicstoryofan individual’sescapetofreedom,astheexemplarofthefugitiveslavenarrative hasoveremphasizedevasionofracializedsurveillanceratherthanthecompleximbricationofsurveillanceandsousveillancethat Slavery,Surveillance, andGenre highlights.52 Thiscomplexitycanbeseenparticularlyintextsby womensuchasJacobs,whose IncidentsintheLifeofaSlaveGirl “datesher emancipationfromthetimesheenteredherloophole,eventhoughshedid notcrossintothefreestatesuntilsevenyearslater.”53

Ifthefocusonescapeandrevoltintextsaboutslaveryprivilegesmale authorsbecausetheseextraordinaryformsofresistancerequirethecuttingoffamilialandsocialties,thefocusondetectionprivilegesmale authorsforadifferentreason.Thetraditionalor“conspicuous”detective reliesontheCartesianbifurcationbetweenbodiesandminds(atropethat Poeplayswithin“TheMurdersintheRueMorgue,”inparticular).In thisschema,rationality—thedetective’spurview—islinkedtodisembodied visionexclusivelyavailabletowhitemalesubjects,whilewomenandnonwhitepeopleareover-corporealizedandthusbarredfromrationalsubjectivity.54 Thecameraobscurawas,accordingtoJonathanCrary,the“dominantparadigmthroughwhich…[eighteenth-andearly-nineteenth-century thinkers]describedthestatusandpossibilitiesofanobserver.”Byplacingthe observerataremovefromtheexternalworld,enclosedwithinthecamera,this modelofvisionemphasizestheobserver’sdistance,detachment,andinvisibility,andistherefore“afigureforboththeobserverwhoisnominallyafree sovereignindividualandaprivatizedsubjectconfinedinaquasi-domestic space.”55

Giventhecameraobscura’sinfluenceasavisualarchetype,itisperhaps notsurprisingthatcriticshaveidentifieditssignificanceforbothPoeand Jacobs.SusanElizabethSweeneyhasdemonstratedPoe’s“fascinationwith

ocularorgansandopticaleffects,”includingthecameraobscura,arguing thatPoe’sdetectiveprotagonistsinparticularuseopticaltechnology“todiscernsomethingfromadistancewhileshieldingthemselvesfromexposureto it.”56 Poe’sdetectives,inotherwords,exemplifythe“freesovereignindividual”whoremainsinvisibleanddetachedfromtheexteriorworld.Reading Incidents alongsidevisualartistEllenDriscoll’sinstallation“TheLoophole ofRetreat,”MichaelChaneyarguesthatthegarretfunctionsasa“revamped cameraobscura,”which“allows[theprotagonist]Brenttoremaininvisible whilesurveyingthelandscape.”57 Brentinhergarretembodiesthesecondtype ofobserver—“aprivatizedsubjectconfinedinaquasi-domesticspace”—but ChaneyarguesthatJacobsrevisesthecameraobscuramodelby“posit[ing]an embodiedobserverwithinaviewingcontextgenerallyassociatedwithdetachingobservationfromthebody.”58 InheremphasisonBrent’scorporeality, Jacobschallengesthetypeofdisembodied,rationalizedgazethatunderwrites bothconspicuousdetectionandslavespeculation.

Whereastheconspicuousdetective’spowercomesfromhisabilitytocapture,thefemaleprotagonistsIstudyinthefinalchapterharnessthepowerof surveillancetoprotectthemselvesandothersfromcapture.LikePoe’sdetectivefiction,bothJacobs’sautobiography IncidentsintheLifeofaSlaveGirl andCrafts’sunpublishednovelTheBondwoman’sNarrativetakeupthegothic conventionsofsecretsandrevelation,butratherthanconstructingafantasy ofwhitesight,theseAfricanAmericangothictextsportraysousveillanceas future-orientedspeculation.JacobsandCraftsexplicitlycontrastthisenslaved speculationwiththemercilessspeculationinslavesthatdestroyedthelivesof enslavedpeople.Brent,Jacobs’spseudonymin IncidentsintheLifeofaSlave Girl,andHannah,theprotagonistof TheBondwoman’sNarrative,eventually usesousveillancetofacilitateescape,asdidthemaleex-slavenarratorsIconsiderinChapter 1,butthebulkofJacobs’sandCrafts’snarrativesdwellon surveillanceandsousveillancewithintheconditionsofenslavement.Brent’s captivityinthegarret,lookingdownonherenslaverthroughaloophole,ironicallyplacesherintheelevatedpositionofthesurveillant,butthisviewpoint onlyunderscoresherpowerlessness.Shetradestotalinvisibilityfortheability towatchoverherchildren.In TheBondwoman’sNarrative, whichrepurposes materialfromCharlesDickens’sBleakHouse59 (famouslythefirstnoveltofeatureapolicedetective),HannahsurveilsotherBlackpeopleandtriestousethe secretsshediscoverstocreateintimacybetweenherselfandwhitewomenshe hopeswillbeabletoprotecther.Thesetextsbreakdownanycleardivision betweensur-andsousveillanceintheirexplorationofthecontingentpower toprotectconferredbywatchingfrombelow.

Wecanseethecontemporaryrelevanceofthismodelofracializedsurveillanceandsousveillanceintheconflictbetweentwenty-first-centurywhite overseers,whosurveilBlackbodiesandpolicespacesperceivedtobewhite (likeaStarbuckscoffeeshoporauniversitydormitory),andthesousveillantswhofilmviralvideosoftheseencountersandreleasethemonsocial mediatospurpoliticalreform.ThoughSlavery,Surveillance,andGenreentails thesociohistoricalspecificityoftheantebellumslavesystem,itrecognizes thatracializedsurveillancepersistsasan“afterlifeofslavery,”touseStephen Best’sterm.60 Whilesurveillancetheoristsoftenfocusonthetechnologies andpervasivenessoftwenty-first-centurysurveillance,myworkredirectsour attentiontothehumancostsofsousveillance.Inthecoda,Iconsiderwhat wecanlearnfromstudyingtheantebellumliteraryrootsofracializedsurveillance.Thebook’sexaminationofsousveillanceasasetoftacticstoresist, escape,ormerelysurviveracialsubjugationrestoresameasureofagencyto thesurveilled,evenasitalsodemonstrateshowprofoundlyvulnerableisthe watcherfrombelowifsousveillancebecomesvisible.

ThepowerasymmetryintrinsictorelationsofdominationsuchastheUS slavesystemobligedtheenslavedtoconcealtheirresistance.Hartmanelaboratesonthemethodsavailabletooppressedgroups:“Withintheconfines ofsurveillanceandnonautonomy,theresistancetosubjugationproceeded bystealth:oneactedfurtively,secretly,andimperceptibly,andtheenslaved seizedanyandeveryopportunitytoslipofftheyoke.”61 Hartmanemphasizes thefabricationsrequiredtomaintainthefictionthatslaverywasaformof benevolentpaternalism:“Thesimulationofconsentinthecontextofextreme dominationwasanorchestrationintentuponmakingthecaptivebodyspeak themaster’struthaswellasdisprovingthesufferingoftheenslaved.”62 Against thisperformativesimulation,whichimposes“transparencyandthedegrading hypervisibilityoftheenslaved,”concealmentprovidesalimitedformofresistancefortheenslavedperson.63 Thisimperativetoconceal,asJamesC.Scott notes,has“typicallywon[subordinategroups]areputationforsubtlety—a subtletytheirsuperiorsoftenregardascunninganddeception.”64 Asopposed totheenslaver’spower,whichdependedonconspicuoussurveillanceinthe formofoverseersandslavepatrols,enslavedsousveillancehadtoremain concealed—inconspicuous—tobeeffective.65

Thoughthetwenty-first-centuryUnitedStatesshouldnotbesimplistically equatedtothe“contextofextremedomination”thatcharacterizedtheantebellumslavesystem,theprotectivefunctionofinvisibilityforsousveillantsis criticalforanalyzingcontemporaryvisualdocumentationofstate-sanctioned violence.Thehistoricalexamplesofvisibleandinvisiblesousveillancethat

Iconsiderinthisbookofferaframeworkforthinkingaboutthepragmatic caseforconcealingsousveillance.Bystandersfilmingvideosofpolicebrutalitywhoareseenrecordingbypoliceareoftentargetedforharassmentorarrest themselves,and,iftheiridentityisrevealed,theyarefrequentlymetwithdeath threats.Nevertheless,observerscontinuetoputthemselvesinharm’swayin ordertorevealthecontinuingviolencefacedbypeopleofcolor.66 Bytracing theantebellumliteraryrootsofsousveillance,Slavery,Surveillance,andGenre highlightsthelongandongoinghistoryofresistancetoracializedsurveillance andpolicing.