Pagan Inscriptions, Christian Viewers

Te Aferlives of Temples and Teir Texts in the Late Antique Eastern Mediterranean

ANNA M. SITZ

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sitz, Anna M., 1988– author.

Title: Pagan inscriptions, Christian viewers : the aferlives of temples and their texts in the late antique Eastern Mediterranean / Anna M. Sitz.

Other titles: Writing on the wall Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2023. | Series: Cultures of reading in the Ancient Mediterranean | Revision of the author’s thesis (doctoral)—University of Pennsylvania, 2017, under the title: Te writing on the wall : inscriptions and memory in the temples of late antique Greece and Asia Minor. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifers: LCCN 2022051689 (print) | LCCN 2022051690 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197666432 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197666456 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Architectural inscriptions—Middle East. | Christianity and culture—Middle East. | Language and culture—Middle East. | Christianity and other religions—Middle East. | Social perception—Middle East.

Classifcation: LCC NA 4050 I5 S58 2023 (print) | LCC NA 4050 I5 (ebook) | DDC 729/.19093—dc23/eng/20221125

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022051689

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022051690

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197666432.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

To my family

So Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: “To the unknown god.” What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you

Acts 17:22–23, English Standard Version

4. Spoliation: Integrating and Scrambling tions-Inscrip

5.

6. Conclusion:

List of Figures

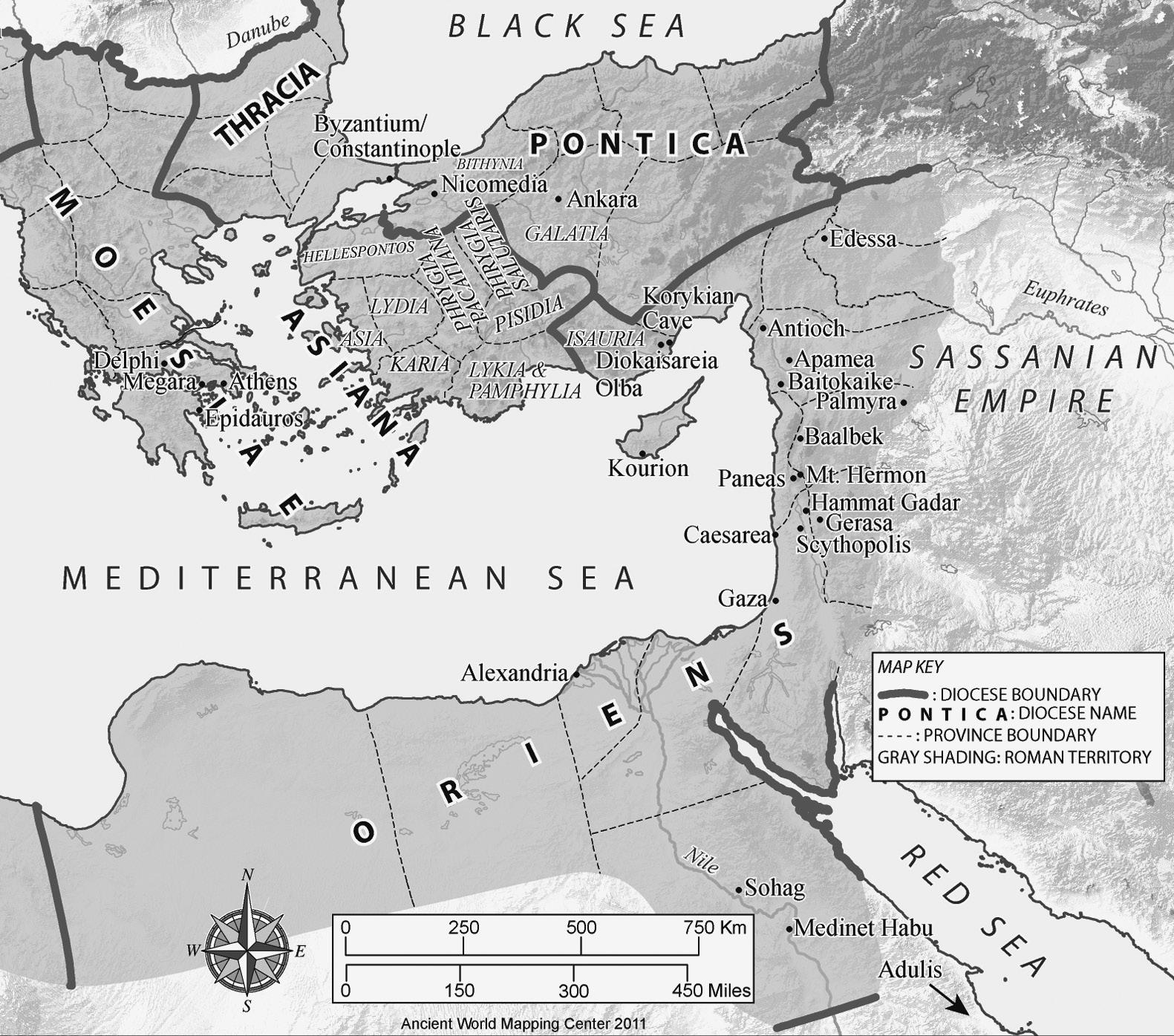

Map 1 Eastern Mediterranean in the time of Diocletian and Constantine, with the province names in western Asia Minor. Ancient World Mapping Center © 2023 (awmc.unc.edu). Used by permission, with modifcations. xxvii

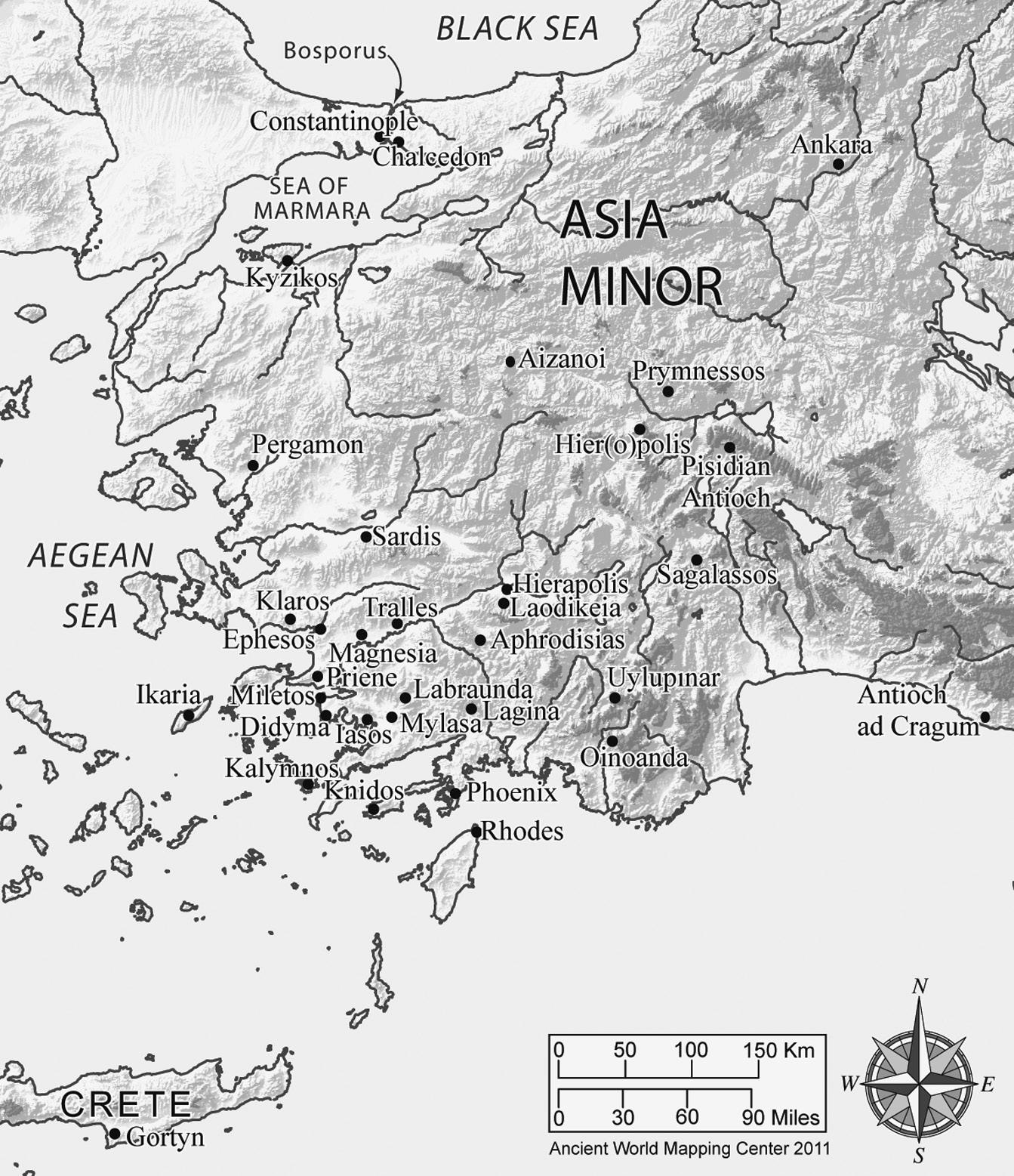

Map 2 Western Asia Minor, with sites discussed in the text. Ancient World Mapping Center © 2023 (awmc.unc.edu). Used by permission, with modifcations. xxviii

1.1 Megara. Late antique inscription (IG VII 53) honoring the Persian War dead with a reinscribed epigram of Simonides of Keos. Wilhelm 1899, 238. 2

2.1 Tralles. Honorifc base for Chairemon (SEG 61.880). Photo courtesy of Murat Aydaş. 36

2.2 Manuscript of Christian Topography by Kosmas Indikopleustes. Illustration of the inscriptions of Abdulis. Ninth century. Vatican Library, Vat. Gr. 699, Folio 15v. © 2023 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, all rights reserved. 40

2.3 Hier(o)polis. Inscription of Abercius (SEG 30.1479). Late second/early third century. Vatican Museum no. 31643. © Governorate of the Vatican City State-Directorate of the Vatican Museums, all rights reserved. 54

2.4 Hier(o)polis. Inscription of Alexandros, son of Antonios (IGR IV 694). 216 ce. Istanbul Archaeology Museum. Ramsay 1897, 721. 57

3.1 Ephesos. Façade of the “Temple of Hadrian” with I.Ephesos 429. Quatember 2017 Pl. 22. Used by permission. 75

3.2 Priene. Dedication of Alexander the Great (I.Priene B—M 149) and following documents on the front of the northeast anta of the Temple of Athena Polias. British Museum no. 1870,0320.88. © Te Trustees of the British Museum. 78

3.3 Priene. Plan of the sanctuary of Athena Polias. Hennemeyer 2013, Fig. 4. Used by permission. 80

3.4 Priene. Marble female head identifed as Ada, found in the Temple of Athena Polias. British Museum no. 1870,0320.138. © Te Trustees of the British Museum. 81

3.5 Mylasa. Temple of Augustus and Roma. Inset detail of the inscribed architrave (I.Mylasa 31). Pococke 1745, Pl. 55, with modifcations. 85

3.6 Mylasa. Plan of the Temple of Augustus and Roma. Approximate locations of I.Mylasa 613 on the podium indicated. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, afer Rumscheid 2004, Fig. 17. 87

3.7 Magnesia on the Maeander. Temple of Zeus Sosipolis, section reconstruction. Humann 1904, Fig. 165. 89

3.8 Magnesia on the Maeander. Temple of Zeus Sosipolis, plan. Humann 1904, Pl. 18. 91

3.9 Delphi. Altar of the Chians. Amandry 1981, Fig. 60. Courtesy of the École française d’Athènes. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Archaeological Resources Fund. 94

3.10 Ankara. Plan of the archaeological remains of the city. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, modifed from Kadıoğlu, Görkay, and Mitchell 2011. 97

3.11 Ankara. Temple of Augustus, current state plan. Author, afer Krencker and Schede 1936, Pl. 2. 98

3.12 Ankara. Temple of Augustus, view of the annex from the exterior (permit no. 64298988-155.02E.218252). Author, courtesy of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 99

3.13 Ankara. Temple of Augustus, section of the exterior southeastern façade. Cross grafti and Byzantine inscriptions (I.Ancyra 497–499) below the Greek Res Gestae are marked. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, modifed from Krencker and Schede 1936, Pl. 6. 108

3.14 Ankara. Temple of Augustus, detail of cast of the exterior southeastern façade. Greek Res Gestae with Byzantine grave text I.Ancyra 498 below. Mommsen 1883, Pl. 9. 108

3.15 Aizanoi. Apse in the proanos of the Temple of Zeus. Rudolf Naumann 1979, Fig. 44. Used with permission. 114

3.16 Aizanoi. Temple of Zeus. Author, courtesy of the Aizanoi Excavations. 115

3.17 Aizanoi. Exterior wall of the Temple of Zeus with grafti, below the Eurykles dossier (OGIS 504–507). Courtesy of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Istanbul (D-DAI-IST-R31242). 116

3.18 Sardis. View toward Temple of Artemis and Chapel M. Author, courtesy of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. 123

3.19 Sardis. Plan of the Temple of Artemis area in late antiquity. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College. 124

3.20 Sardis. Christian grafti on the southeastern door jamb of the Temple of Artemis. Courtesy of the Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University. 124

3.21 Sardis. Nannas Bakivalis monument. Courtesy of the Howard Crosby Butler Archive, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University. 126

3.22 Lagina. Plan of the sanctuary of Hekate with the basilica in grey. Gider 2012, Fig. 1. Used with permission.

3.23 Lagina. General view of propylon, the Temple of Hekate, and the area of the basilica. Author, courtesy of the Stratonikeia Excavations.

3.24 Lagina. Grafti on the stylobate of the Temple of Hekate. Author, courtesy of the Stratonikeia Excavations.

3.25 Medinet Habu. View of church in the temple, before 1903. Antonio Beato, Yale University Art Gallery.

3.26 Didyma. Church in the adyton of the Temple of Apollo. Wiegand 1924, Pl. 2.

3.27 Didyma. Masons’ marks on wall (south wall, eastern part). I.Didyma, Fig. 51. Used with permission.

3.28 Miletos. Erzengelinschrif (“archangel inscription”) on a wall of the theater. Photo: E. Steiner. Courtesy of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Istanbul (D-DAI-IST-Perg.86/311-1).

4.1 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Section showing the sinkholes and the opening of the cave system, as well as the chapel and the temple-church. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, afer Bayliss 2004, Fig. 109.

4.2 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Clifop temple-church plan. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, afer Bayliss 2004, Fig. 110.

4.3 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Clifop temple-church plan, detail. Inscribed faces (A, B, and C) of the anta marked. Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, modifed from Bayliss 2004, Fig. 110.

4.4 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Clifop temple-church, anta, inscribed faces A, B, and C. Author, courtesy of Hamdi Şahin.

4.5 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Drawing of the three uppermost courses of the inscribed faces of the Clifop temple anta (A, B, and C, I.Westkilikien Rep. Korykion Antron 1). Heberdey and Wilhelm 1896, 73, Fig. 10.

4.6 Sagalassos. Façade reconstruction of the Temple of Apollo Klarios with I.Sagalassos 20. Lanckoroński 1892, Pl. 25.

4.7 Sagalassos. Plan of the temple-church with Lanckoroński’s proposed placement of the architrave (dotted lines). Author and Yasmin Nachtigall, modifed from Lanckoroński 1892, Fig. 123.

4.8 Aphrodisias. Site plan. Courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias (Harry Mark).

4.9 Aphrodisias. Composite plan showing the Temple of Aphrodite and the temple-church. Courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias (Harry Mark).

129

130

131

137

141

142

143

157

159

160

161

162

167

169

173

176

4.10 Aphrodisias. Tabulae ansatae (marked) with inscriptions on the north colonnade of the temple-church (I.Aphrodisias 2007 1.4–1.8). Author, courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 177

4.11 Aphrodisias. Door lintel of the northern entrance into nave with I.Aphrodisias 2007 1.102. Courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 179

4.12 Sardis. Plan of the synagogue, fourth phase. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College. 189

4.13 Sardis. Epichoric inscription in an unknown Anatolian language found in the synagogue. Sardis IN63.141. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/ President and Fellows of Harvard College. 190

4.14 Labraunda. Interior of Andron A with I.Labraunda 137 marked. Courtesy of the Labraunda Excavations. 193

4.15 Labraunda. Upper surface of the stone with I.Labraunda 137, showing original and later cutting marks. Courtesy of the Labraunda Excavations. 194

4.16 Phoenix. Doorway into the nave of the Kızlan Deresi church with a dedication to Apollo (detail); the dedication to Eleithya is below it. Author, courtesy of the Phoenix Archaeological Project. 198

5.1 Aphrodisias. Bust of Alexander the Great with cut mark on the neck. Author, courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 210

5.2 Perge. Statue of a Grace (Antalya Museum Inv. 2018/133) with damage to the pubic area and breast. Author, courtesy of the Antalya Museum. 213

5.3 Burdur Museum. Inscribed spolia (I.Mus. Burdur 184) in a baptistery from Uylupınar (permit no. 51544244-155.02-E.158017; 64298988-155.02E.156523). Author, courtesy of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 222

5.4 Aphrodisias. Northeast gate with erased and replaced inscription (I.Aphrodisias 2007 12.101ii). Courtesy NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 224

5.5 Aphrodisias. Teater with skene architrave and frons pulpiti marked. Author, courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 226

5.6 Aphrodisias. Chiseled relief of Aphrodite from the Sebasteion, with cross added at lower lef. Author, courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 228

5.7 Aphrodisias. Door lintel from the Temple of Aphrodite (I.Aphrodisias 2007 1.2), reused at the main entrance into the nave of the temple-church. Author, courtesy of NYU Excavations at Aphrodisias. 229

5.8 Labraunda. Site plan with the South Propylaea and fnd area of the architrave blocks marked in dashed lines. Courtesy of the Labraunda Excavations. 234

5.9 Labraunda. Architrave of the South Propylaea (I.Labraunda 18), unerased and erased blocks. Photos: Arthur Nilsson, Labraunda Excavation 1949, courtesy of the Labraunda Archives, Uppsala University Library (LabArP:1949:399 and LabArP:1949:328). 235

5.10 Aizanoi. Säulenstraße, erased and unerased sections of the Artemis architrave (SEG 45.1708). Photos: D. Johannes, courtesy of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Istanbul (D-DAI-IST-Ai-93-454 and D-DAI-IST-Ai-93-342). 238

5.11 Aizanoi. Säulenstraße, partially erased dedication to Zeus and Nero (SEG 45.1711). Photo: D. Johannes, courtesy of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Istanbul (D-DAI-IST-Ai-94-1). 239

5.12 Antioch ad Cragum. Northeast Temple block with dice oracle inscription (I.Westkilikien Rep. Antiocheia epi Krago 19). Bean and Mitford 1965, no. 43. 242

5.13 Korykian Cave (Kilikia). Clifop temple-church, I.Westkilikien Rep. Korykion Antron 1, partially erased. Author, courtesy of Hamdi Şahin. 246

5.14 Pisidian Antioch. Fragments of the Res Gestae divi Augusti. Ramsay and von Premerstein 1927, Pl. 11. 251

6.1 Ankara. Temple of Augustus within the Hacı Bayram complex in 1881 or 1882. Photo: John Henry Haynes (HayAr.239 AKP160). Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University. 275

Preface

Why are the famous Parthenon marbles currently sitting in the British Museum? Because of Lord Elgin, of course. But Elgin could only take down the pedimental statues and reliefs from the Parthenon because they were still in place up to his time: because a series of decisions had been made centuries earlier. In late antiquity—sometimes called the early Christian period—the decision was made not to remove or edit much of the fgural imagery of this pagan temple at the heart of Athens, even when it became a church in approximately the seventh century, nor to dismantle the temple completely. Te Parthenon is ofen lauded as a remarkable instance of the tolerance of early Christians toward ancient statuary, although some fgural reliefs were chiseled away (at an uncertain time). In sanctuaries and cities throughout the late Roman empire, the relationship of Christians to older carved fgural images can perhaps best be described as “it’s complicated.” Some statues were destroyed or edited even as others were preserved in place or sought out as desirable elements—and these decisions were informed by the discourses on statuary taking place in the literature and homilies of the day.

Marble statues were not the only elements of the ancient world to remain prominent in our period. For decades, scholars of late antiquity have attempted to document and understand the enduring value of the classical past in this new era of “Christianization.” Tey have pinpointed the ways that ancient Greek and Roman myths, oratory, histories, and poetry infected Christian texts and thought-worlds. St. Jerome (c. 342–420) may have claimed to give up Cicero for Christ (Ep. 22), but his writings remained permeated with classical rhetoric—and he could not resist praising the pious Christian Paula for her ancestry leading back to the Gracchi, to the Scipiones, and even to Agamemnon himself (Ep. 108). Te most famous Greek poet of all, Homer, was still read, emulated, adapted, annotated, and illustrated in our period; St. Basil of Caesarea (330–379) encouraged his students to seek virtue in the verses or sayings attributed to Homer, Hesiod, and Solon (Ad adulescentes). Herodotos’ tale of Kroisos and the oracle at Delphi appears in the proem of the ffh-century Miracles of St. Tekla as a foil for the more reliable (and less tricky) wisdom of the Christian saint. Prokopios’ literary

style in the sixth century is founded on the tradition of classicizing histories stretching back to the same Herodotos and to Tucydides. He claimed that the late antique population of Rome took great care of their classical patrimony—even keeping the ancient ship of Aeneas on view. Meanwhile, at Gerasa in Jordan, a Christian priest bearing the name Aeneas put up an inscription that quoted from the Iliad, but at the same time denigrated the pagan rituals that had formerly taken place at the site of his church. Late antique pagan intellectuals—who came to be called Hellenes (“Greeks” or “pagans”) by their Christian contemporaries—likewise built upon and grappled with the ideas of ancient poets and philosophers.

Not only in the discursive sphere, but in the physical one as well, late antique individuals made the decision to keep monuments of the classical past front and center in cities and landscapes. Older buildings with their classical façades continued to stand and be maintained throughout the empire. Greek and Roman architectural marbles from disassembled or destroyed buildings were repurposed in new structures as spolia. Objects both elite, such as the mid-fourth-century silver Projecta casket bearing an image of Aphrodite, and banal, such as wine fasks emblazoned with Dionysos, drew on classical iconography. Some ancient deities, such as river gods and winged Victory, were relegated to the realm of “personifcations” and continued to appear in explicitly Christian art for centuries.

Aesthetically, materially, and conceptually, then, the late antique world was deeply indebted to its classical forebear, even as fundamental paradigms shifed. Te continued vitality of Hellenism, as well as Roman and local or indigenous cultures, has been well documented in numerous works of scholarship. Tere are now few researchers who would countenance the portrayal of the early Christian period as a fundamental and complete break from the classical past, regardless of where one fnds oneself in the debate on decline and fall.

When I started my research for this project, I thought that just about every iota of evidence for late antique attitudes toward the classical past had been examined. Short of newly excavated fnds or newly deciphered papyri, we are limited in the data set we can use to interrogate “Christianization” or the reception of classical culture in our period. Certainly, there is still a need to re-examine old evidence with fresh eyes, with new and diverse theoretical perspectives or in innovative combinations. But I was surprised to realize that a signifcant body of evidence for the late antique reception of the classical past has been largely overlooked: the fates of ancient inscriptions.

Whereas the reading of Greek and Roman literature in late antiquity has been widely acknowledged and analyzed, the reading of Greek and Roman inscriptions has not—never mind that, in the telling of Acts 17:22–23, St. Paul himself initiated the use of an ancient inscription (“to the unknown god”) in the Christian world-building project. So too has the study of reusing ancient architectural marbles proven to be a rich space in which to tease out attitudes toward the past, but this has not been the case for inscribed marbles. I am not presenting in this book truly new evidence, in the sense of unpublished or re-edited inscriptions, but I am collecting and bringing this data set to bear on questions of reception and attitudes toward the Greek, Roman, and local pasts for the frst time in a comprehensive way. I do this by examining the discourses surrounding inscriptions—carved in a variety of eastern Mediterranean languages, legible and illegible—in the late antique literary sources, and by examining the fates of the physical inscribed stones themselves at various archaeological sites. Inscriptions were not very likely to receive the kind of scholia that clues us in to the reception received by Homer, for example, nor to receive the lengthy theorization in treatises and hagiographies that ancient statuary did. But if our evidence is more taciturn than that for the reception of ancient literature and art, it only means that we have to listen to it more closely.

Abbreviated Epigraphic Corpora

Abbreviations follow the SEG

AE 1888–. L’Année épigraphique, Paris.

CIG 1828–1877. Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, Berlin.

CIJud Frey, J. B. 1936–1952. Corpus inscriptionum Judaicarum, Vatican.

CIL 1863– Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, Berlin.

F.Delphes III 1909–1985. Fouilles de Delphes III. Épigraphie, Paris.

I.Ancyra Mitchell, S., D. French. 2012–2019. Te Greek and Latin Inscriptions of Ankara (Ancyra), Munich.

I.Aphrodisias 2007 Reynolds, J., C. Roueché, and G. Bodard, eds. 2007. Inscriptions of Aphrodisias (2007), http://insaph.kcl.ac.uk/iaph2007/ index.html.

I.Byzantion Łajtar, A. 2000. Die Inschrifen von Byzantion, Bonn.

ICG Breytenbach, C., K. Hallof, U. Huttner, P. Hommel, S. Mitchell, J. M. Ogereau, M. Prodanova, E. Sironen, M. Veksina, and C. Zimmermann, eds. 2016. Inscriptiones Christianae Graecae: A Digital Collection of Greek Early Christian Inscriptions from Asia Minor and Greece, http://repository.edit ion-topoi.org/collection/ICG.

I.Chr. Macédoine Feissel, D. 1983. Recueil des nscriptions chrétiennes de Macédoine du IIIe au VIe siècle, Paris.

I.Cret. Guarducci, M. 1935–1950. Inscriptiones Creticae, Rome.

I.Didyma Rehm, A., R. Harder. 1958. Didyma II Die Inschrifen, Berlin.

I.Ephesos 1979–1984. Die Inschrifen von Ephesos, Bonn.

I.Ethiopie Bernand, E., A. J. Drewes, and R. Schneider. 2000. Recueil des Inscriptions de l’Éthiopie des périodes pré-axoumite et axoumite. Vol. 3, Les inscriptions grecques. Paris.

I.Gerasa Welles, C. B. 1938. “Te Inscriptions” in Gerasa. City of the Decapolis, ed. C.H. Kraeling, New Haven, CT, 355–494.

IG 1873–. Inscriptiones Graecae, Berlin.

IGLS 1929– Inscriptions grecques et latines de la Syrie, Beirut.

IGR 1906–1927. Inscriptiones Graecae ad Res Romanas Pertinentes, Paris.

I.Iasos Blümel, W. 1985. Die Inschrifen von Iasos, Bonn.

xxiv Abbr eviated Epigraphic Corpora

I.Ikaria Matthaiou, A. P. and G. K. Papadopoulos. 2003. Ἐπιγραφὲς Ἰκαρίας, Athens.

I.Knidos Blümel, W. 1992–2019. Die Inschrifen von Knidos, Bonn.

I.Kibyra Corsten, T. 2002. Die Inschrifen von Kibyra, Bonn.

I.Kourion Mitford, T. B. 1971. Te Inscriptions of Kourion, Philadelphia.

I.Labraunda Crampa, J. 1969–1972. Labraunda. Swedish Excavations and Researches 3: Greek Inscriptions, I–II. Lund.

I.Laodikeia Lykos Corsten, T. 1997. Die Inschrifen von Laodikeia am Lykos, Bonn.

I.Lindos Blinkenberg, C. 1941. Lindos. Fouilles et recherches. Vol. 2, Fouilles de l’ acropole. Inscriptions, Berlin.

I.Magnesia Kern, O. 1900. Die Inschrifen von Magnesia am Maeander, Berlin.

I.Milet 1997–2017. Milet VI. Inschrifen von Milet, Berlin.

I.Mus. Burdur Horsley, G. H. R. 2007. Te Greek and Latin Inscriptions in the Burdur Archaeological Museum, London.

I.Mus. Iznik Şahin, S. 1979–1987. Katalog der antiken Inschrifen des Museums von Iznik (Nikaia), Bonn.

I.Mylasa Blümel, W. 1987–1988. Die Inschrifen von Mylasa, Bonn.

I.Pergamon Fraenkel, M. 1890–1895. Altertümer von Pergamon VIII Die Inschrifen von Pergamon, 1–2, Berlin.

I.Perge Şahin, S. 1999–2004. Die Inschrifen von Perge, Bonn.

I.Phil.Dem. Grifth, F. L. 1937. Catalogue of the Demotic Grafti of the Dodecaschoenus, Cairo.

I.Priene B—M Blümel, W., E. Merkelbach. 2014. Die Inschrifen von Priene, Bonn.

I.Rhodische Peraia Blümel, W. 1991. Die Inschrifen der rhodischen Peraia, Bonn.

I.Sagalassos Eich, A., P. Eich, and W. Eck. 2018. Die Inschrifen von Sagalassos, Bonn.

I.Sardis I Buckler, W. H., D. M. Robinson. 1932. Sardis VII. Greek and Latin Inscriptions, Part 1, Leiden.

I.Sardis II Petzl, G. 2019. Sardis. Greek and Latin Inscriptions. Part 2, Finds from 1958 to 2017, Cambridge, MA.

I.Stratonikeia Şahin, M. Ç. 1981–2010. Die Inschrifen von Stratonikeia, Bonn.

I.Westkilikien Rep. Hagel, S., K. Tomaschitz. 1998. Repertorium der westkilikischen Inschrifen nach den Scheden der Kleinasiatischen Kommission der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschafen, Vienna.

MAMA 1928–2013. Monumenta Asiae Minoris Antiqua, London.

Abbreviated Epigraphic Corpora xxv

OGIS Dittenberger, W. 1903–1905. Orientis Graeci Inscriptiones Selectae, Leipzig.

RIB 1965–2006. Te Roman Inscriptions of Britain, Oxford.

SEG 1928–. Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecae, Leiden.

TAM 1901– Tituli Asiae Minoris, Vienna.

Tit. Calymnii Segre, M. 1952. Tituli Calymnii, Athens.

Map 1 Eastern Mediterranean in the time of Diocletian and Constantine, with the province names in western Asia Minor. Ancient World Mapping Center © 2023 (awmc.unc.edu). Used by permission, with modifcations.

Map 2 Western Asia Minor, with sites discussed in the text. Ancient World Mapping Center © 2023 (awmc.unc.edu). Used by permission, with modifcations.