Acknowledgments

When I began this project I imagined a narrow, relatively brief study of Vietnam policy during the Nixon years. While there was considerable declassified material available at the time, I was unprepared for the avalanche of material about this presidency that has appeared over the previous fifteen years. The richness of these sources enables more insight into the foreign policy operations of an administration than we are likely to see again. In response, my conception of the topic widened considerably and has taken much longer and required more help from fellow historians, friends, and family than I ever anticipated.

Above all, this book reflects conversations with students. During decades of teaching, I realized the importance of integrating the study of high-level policy with an examination of its impact on people’s lives. Absent that connection, then either subject loses its significance. Additionally, students’ impatience with an exclusive focus on two or three men at the pinnacle of power (in this instance Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger) compelled a wider inquiry: what were the societal and institutional forces that shaped their decision-making? And finally, how did the war in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos fit with broader trends in US foreign policy? Or more precisely, how to explain the paradox of an administration avidly seeking improved relations with Moscow and Beijing, while raining destruction on these smaller nations?

I hope this book will provide some answers to these questions. Without students’ voices in my head, this work would not have been possible.

Among historians in related fields, I have received assistance of various kinds from shared documents, insightful conversations, and close reading of individual chapters. I am especially grateful to: Chris Appy, Andrew Bacevich, Kai Bird, Bob Brigham, Gregory Daddis, the late Todd Gitlin, Jeffrey Kimball, Lien-Hang Nguyen, Arnold Offner, John Prados, David Schmitz, and the late Martin Sherwin. I am especially indebted to Elsa Dixler, an historian, friend and editor, who supported this work from beginning to end, bringing clarity out of fog.

I have been fortunate to have thoughtful, generous friends who were willing to read portions of the manuscript, offer pertinent advice, and reassure me that the content was truly significant. Among them were Fran Dreier, Barbara Epstein, Bill and Marlene Fried, Steve Leberstein, Judith Liben, Daniel and Barbara Pope, Margaret Power, Rosalind Pollak, Martha Saxton and Susan Yohn To concentrate on writing, I spent several summers in Amherst, where I received valuable advice from college friend Randy Ross, who had gone to Vietnam during the war and who was editing an English translation of Madame Binh’s memoirs. Through Randy I was fortunate to meet with Lady Borton, who has lived in Vietnam for years and is a fountain of information and fresh insights.

Sadly, three people who played a vital role in this project are now deceased. Stanley Kutler believed in this work from the beginning, continually reminded me of its importance, readily shared his encyclopedic Nixon knowledge, and assisted me with archival access. A mellow Tom Hayden gave useful advice for my Vietnam trip, shared his insights about Congressional work past and present, and left ringing in my ears his admonition, “Hurry up!” And finally, Marilyn Young, who encouraged this book early on and for the last eighteen months of her life suggested, quipped, nagged, and argued with me never losing her outrage at the destruction and suffering caused by the Vietnam War.

This book would not have seen the light of day without the support of two superb agents: Steve Wasserman, who helped me craft a proposal and to think carefully about “the arc of the story,” and Katherine Flynn, who advised me through the vicissitudes of publication and whose confidence in this manuscript never wavered.

I remain especially indebted to freelance editor Beth Rashbaum, who entered this project at a critical time. Over an extended period, she helped me pare down a too cumbersome, detailed manuscript, while skillfully retaining the intertwined threads that kept this a coherent narrative. Beth’s professionalism in the art of writing is matched by her profound attention to content. She was constantly alert to factual mistakes and did not hesitate to verify claims when they seemed unsupported or contradictory.

Historians rely on their archivists, and I was especially fortunate in having the assistance of John Powers at the Nixon Project in the National Archives, Donald Davis at the American Friends Service Committee Library, and Steve Maxner at the Texas Tech Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Archive.

In Vietnam, the staff at the Vietnam-USA Friendship Society, headed by Bui Van Nghi, were efficient and gracious, facilitating travel for my husband and me, arranging for translators, meetings, and interviews with former officials, veterans, and other participants in the war. Especially helpful was To Ngoc Linh, who served as a guide and translator and in his thoughtful way made the experience more meaningful.

Early in the trip, former Vice President Nguyen Thi Binh (Madame Binh) predicted that I would encounter a welcoming attitude by most Vietnamese. During the war, Ho Chi Minh had emphasized that the American people were not the enemy, only its government. In the postwar period, this perspective was reinforced by the numerous US veterans who had come back to Vietnam to work on humanitarian projects. Throughout our travels we were touched by the friendly response of young people, as well as the eagerness of those from the older generation to tell their stories.

Two Hofstra undergraduates, Ariel Flajnik and Carlos Gonzalez, did valuable research for this book. I am also indebted to Hofstra University for three Special Leaves and several Faculty Research Grants in support of this work. I benefitted as well from a Fellowship at the Cold War History Project, Tamiment Library, New York University, and a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Summer Seminar Directorship. For the latter, an amazing gathering of high school teachers added depth to my inquiries.

During the last two years of this project, Susan Ferber, history editor at Oxford University Press, has assisted me with her confidence, superb judgement, and rapid ability to improve text. Working with her has been a privilege and pleasure.

My work on Fire and Rain has gone on for more years than I like to count long enough to burden even my grandchildren. However, for sheer endurance and loving support special recognition goes to my husband Allan, who has sustained more life disruptions, carried more boxes, and heard more stories about Richard Nixon than any life partner should endure. In important ways, we have traversed this history together from watching the 1968 carnage in Hue on our black-and-white television to visiting the Citadel four decades later, on a bright sunny day, as Vietnamese school children romped in a park.

During these last years of writing, my daughter Lizzy has served as my invaluable technology therapist, constantly reassuring me that “No, we haven’t erased the whole book.” For Lizzy and the others in my immediate

family—Jenny, Annie, Miguel, and Jeremiah—I love you all and am constantly grateful for your joyful presence.

1 Map of Southeast Asia

Map

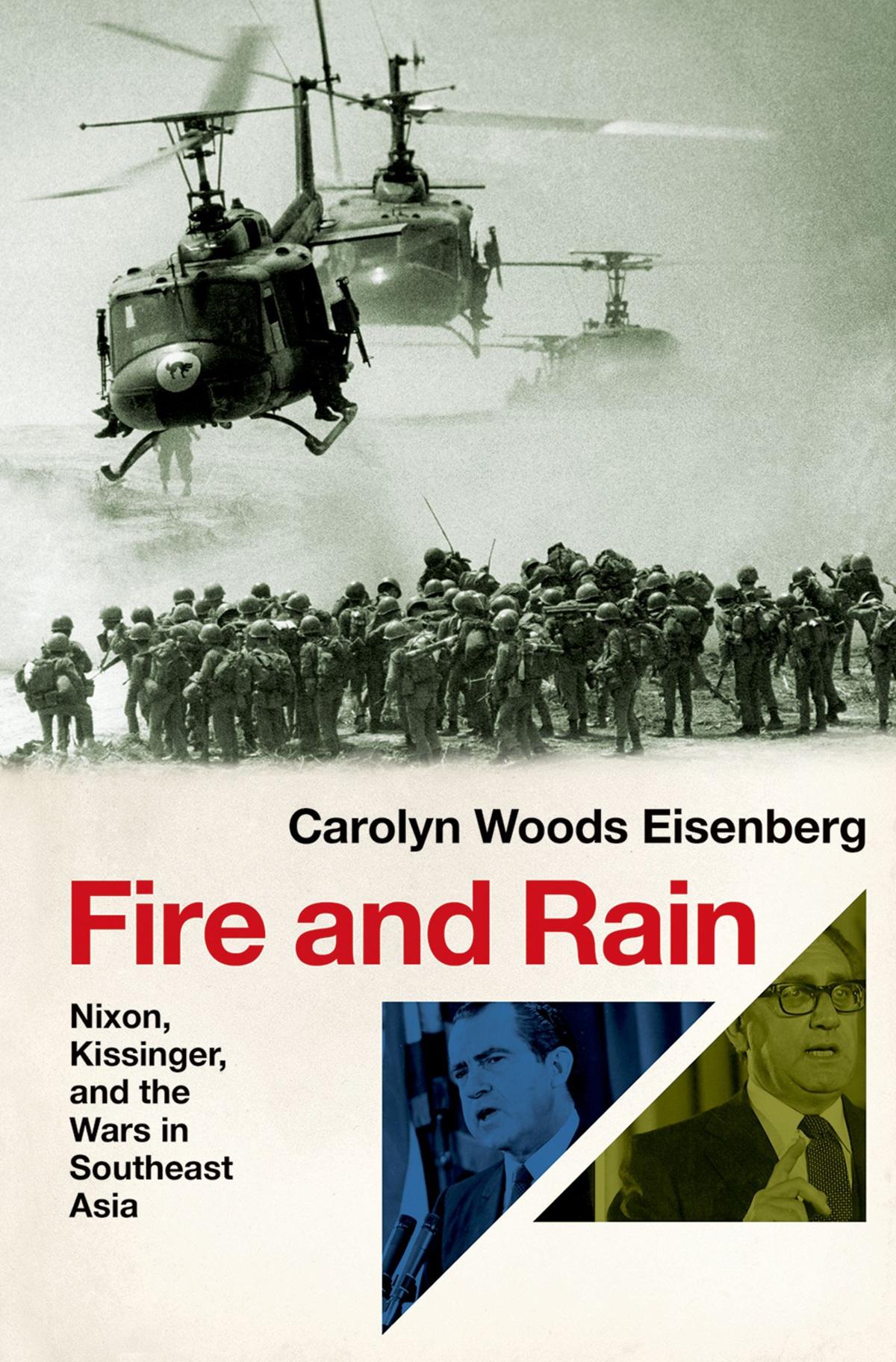

Fire and Rain

Introduction

“This Is Not Frivolous, Mr. Chairman”

It was viewed as an awesome responsibility. For members of the House Judiciary Committee, whatever they had said about Richard Nixon in the past, whether in anger or admiration, a decision to approve articles of impeachment weighed heavily. If approved, it would go to the full House of Representatives for a vote; and if the vote was in favor of impeachment, then the US Senate would decide whether the president was guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” While theirs was only the first step in the process, members of the Judiciary Committee had strong reasons to believe that what they collectively decided could determine the fate of the president of the United States. More than a century had passed since the last time Congress had entertained such a possibility. And it was no small thing to unseat a president especially Richard Nixon, who in his re-election effort had carried every state in the union but one.

From May 9 through July 30, 1974, the Committee (consisting of 36 men and two women) pored over books of documents, questioned witnesses, weighed the arguments of counsel, and debated with one another. Its chairman, Democrat Peter Rodino, wanted to focus on the first three articles of impeachment; seeking to minimize party divisions, he believed those to be the most likely to find some measure of bipartisan support. Each of these three articles pertained to domestic crimes linked in some fashion to the Watergate break-in and subsequent investigations.

Since June of 1972, when seven men were arrested for illegally entering the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate Hotel, there had been a steady drip and then a flood of revelations about the administration’s misuse of power. This break-in, which seemed inexplicable on the surface, had been executed by a “Plumbers” group connected to the White House and specifically to the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP). The “Plumbers,” it emerged, had been responsible for illegal eavesdropping, burglaries, intimidation, and “dirty tricks.”

Because the connection to the White House would be so damaging to Nixon if it came to light, there had been a wide-ranging cover-up designed to insulate him from the crime. During the 1972 election season, White House lawyer John Dean had successfully managed this task. However, since the inauguration the official story had steadily unraveled, and by the spring Dean himself had become a hostile witness. Over the course of the following year, more details had emerged about the administration’s illegal efforts to suppress this and other scandals. By the time the House Judiciary Committee convened, key members of the president’s team were facing felony charges, among them former Chief of Staff H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, Assistant to the President John Ehrlichman, Special Counsel Chuck Colson, and former Attorney General John Mitchell.

Given the weight of evidence, it was no surprise that a majority of the committee voted in favor of the first three articles: Article I, which accused the president of personally acting to obstruct justice in the Watergate case; Article II charging him with persistent misuse of his authority in upholding the country’s laws; and Article III faulting him for defying subpoenas of his records and withholding other evidence pertinent to the impeachment process.1 With their passage, it became unlikely that Richard Nixon would finish out his term of office.

Cast into oblivion were two other articles of impeachment, which were rejected by a majority on the committee. One of these had relatively narrow significance the accusation that the president had underpaid federal income tax and accepted government financing of improvements to his personal homes. But Article IV had a much wider reach and sparked intense debate among committee members. Introduced by Representative John Conyers of Michigan, it charged the president with “the submission to the Congress of false and misleading statements concerning the existence, scope and nature of American bombing operations in Cambodia in derogation of the power of the Congress to declare war, to make appropriations and to raise and support armies.”

For some Americans, any reference to Cambodia could evoke deep emotions. The uproar surrounding the president’s decision to send troops in April 1970 had produced the largest antiwar protest of Nixon’s first term, culminating in an explosion of dissent and some violence on college campuses, most memorably the shooting and deaths of four students at Kent State University.

The US invasion of Cambodia, which had been publicly announced, was not the primary focus of the proposed article. Instead, it was the fourteen months of covert bombing of Cambodia that Nixon had ordered prior to the ground invasion. During this period, B-52 bombers had launched 3,695 attacks on that country, despite the president’s repeated insistence that the United States had never intervened there prior to the invasion.2

The dishonesty of that claim had only garnered attention in July 1973, when retired Major Hal Knight testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that in his capacity as supervisor of radar crews in South Vietnam, he had helped falsify the flight records of at least two dozen missions by disguising American air strikes in Cambodia as attacks inside South Vietnam. In an elaborate arrangement, the real coordinates for the planes were hand-delivered to Knight by a courier from General Creighton Abrams’ headquarters in Saigon, and then given to the pilots. Once the flights returned, there was a dual system of reporting in which fake information was entered into the Pentagon computers while Knight would gather and burn the incriminating documents. To signify a successful mission, he would place a call and report to an anonymous official in Saigon: “The ball game is over.”3

The Senate Armed Services Committee quickly learned that Knight’s experience was part of a larger pattern of falsifying records to hide the bombing of Cambodia from the American public and from Congress. So farreaching was the secrecy surrounding this undeclared war that even the civilian Secretary of the Air Force, Robert Seaman, was not informed.4

Who had orchestrated the elaborate system of deception? In the aftermath of Knight’s testimony, many wished to know. However, one thing was clear: President Nixon had ordered both the bombing and its concealment. By so doing, he had effectively denied members of Congress the opportunity to debate or vote on whether to authorize this military action in an officially “neutral” country.

Unlike the other charges the Judiciary Committee had considered, the veracity of the Cambodia charge was not disputed. Whatever the motive, the Nixon administration had clearly deceived Congress with the intent to sidestep its prerogative to declare war and appropriate funds for that purpose. Conyers wanted the Judiciary Committee to reaffirm that legislative responsibility:

Many people don’t know or have forgotten that the Congress constitutionally has that

sole authority. And so, I would urge that we in an attempt to reassert those powers which we consider vital and precious, if the constitutional form of government is to prevail and continue and improve, that we give the gravest consideration to this article.5

He also contended that it was the desire to hide the bombing that had led to the “unparalleled” use of wiretaps and illegal surveillance of journalists and government officials.

The congressman was referring to events prompted by a May 1969 New York Times article in which Pentagon correspondent William Beecher reported that American B-52s had struck Vietcong and North Vietnamese supply dumps in Cambodia.6 This story had gone nowhere, but had nonetheless infuriated Nixon and Kissinger. So eager were they to identify those who had “leaked” the story to Beecher that, at their behest, the FBI had placed warrantless wiretaps on thirteen government officials, several of whom were on Kissinger’s staff, and on four members of the press. In Conyers’ view, this was “the beginning of a policy of corruption” that had gone on for years.

While he had limited his proposed article of impeachment to the specific lies about Cambodia and the resulting wiretaps, John Conyers saw a direct link between the crimes of Watergate and the administration’s lawless conduct of the Vietnam War. Two years earlier when the Nixon administration had resumed the bombing of North Vietnam and begun the mining of Haiphong Harbor, Conyers and several colleagues had taken out a two-page ad in the New York Times arguing that these were impeachable offenses.7

Partly for this reason, Chairman Rodino and some other Democrats on the Judiciary Committee were worried about Article IV. In their view, drawing too tight a connection between the process of impeachment and opposition to the Vietnam War would be needlessly divisive at a time when they were seeking consensus. Father Robert Drinan, antiwar congressman from Massachusetts and a Jesuit priest, objected to this reasoning. He did not believe “the process for picking articles of impeachment [should be influenced by] whether they will fly” rather than by the gravity of the infraction. The Founding Fathers had recognized that “the ultimate tyranny was war carried on illegally by the Executive without the knowledge or consent of Congress.”8

Yet many on the committee did not agree. As Ohio’s Republican Congressman Delbert Latta stated, “this was a time of war,” when inevitably things happen “that you don’t put on the front page of every newspaper.”9 Nixon’s overriding concern had been to protect American troops and bring them home safely. To the extent that action in Cambodia had contributed to that result, this was a reason for gratitude. Few of Latta’s Republican colleagues went that far, but several maintained that there was shared culpability for the constitutional violations that had occurred during the Vietnam War, and that it was unfair to single out President Nixon. Moreover, it was not only Republicans who had objected to Conyers’ article. Representative Walter Flowers (D-Alabama) thought President Nixon was getting “a bad rap” on this matter. “We might as well resurrect President Lyndon Johnson and impeach him posthumously for Vietnam and Laos.”10

For John Conyers and his newly elected colleague Elizabeth Holtzman (DNY), getting Article IV on the agenda had been an uphill struggle. In allocating staff resources, opportunity for debate, even access to prime-time television, the committee chair had sought to marginalize their concern.11 Up through the final day of the proceedings, Rodino had pressured the Detroit congressman to drop it. Yet Conyers stood by Article IV, maintaining, “This is not frivolous, Mr. Chairman.”

Even those who understood the seriousness of the issue Conyers raised in Article IV did not necessarily want to proceed with it. John Seiberling, who represented the Ohio district of Kent State, acknowledged that “the issue is the falsification of information, the misleading of Congress, the failure to consult Congress on a matter as grave as an act of war.” In his view four students had died because “the President of the United States again abused his power and again invaded Cambodia without consulting the Congress.” Such behavior was reprehensible and must not be tolerated in the future, yet Seiberling contended, “we should not use our impeachment power to impeach” Nixon for “acts of the sort, other Presidents have taken with impunity . . . and for which the Congress bears a very deep measure of responsibility.”12

Proposing to exonerate the president on the grounds that his predecessors had engaged in similar behavior and that past members of Congress had been indulgent was a curious line of argument.13 For those who supported Article IV, however, it seemed clear that it was more important to establish a

precedent for punishing any violation of Congress’ constitutional right and responsibility to make decisions about going to war. Congressman Wayne Owens of Utah expressed his “hope we will set down a standard for Presidents and future wars, that something positive will come out of . . . the history of this sad war in Southeast Asia and the history of this sad proceeding,” In subsequent years, perhaps the American people, acting through their elected representatives, would openly decide questions of war and peace “just like the Constitution requires.”14

Conyers, Holtzman, and several others on the Judiciary Committee considered that secretly bombing a neutral country 3,600 times and lying to Congress about it was so egregious that Article IV article should be approved, so that the entire body of the House could vote on it. Nonetheless, when the roll was called every Republican voted against it, as did nine of their Democratic colleagues.

While members of the Judiciary Committee were casting their historic votes, the New York Times published a set of articles by Sydney Schanberg, who was reporting on the ground in Cambodia. Five years after President Nixon had ordered the bombing of that country, and four and a half years after the overthrow of its head of state, Prince Sihanouk, Cambodia was ravaged by the civil war that had resulted from those events. Writing from the town of Oudong, Schanberg described the aftermath of a battle between the government and the brutal insurgents known as the Khmer Rouge. “Forests have been mowed down, schools, pagodas, mosques and hospitals have been flattened.”15 The same was true of nearby towns Prek Kdam and Kompong Luong, and the villages in between.

Many of the 20,000 inhabitants of Oudang were captured by the rebels when they retreated into the jungle. The rest had escaped to the capital of Phnom Penh. Schanberg described the appalling conditions in this once beautiful capital city. Thousands of homeless children roamed its streets, begging for food. Five years earlier, Phnom Penh had a population of 600,000, but the mass arrival of refugees had swelled that number to more than two million, vastly exceeding the capacity of the residents to absorb them:

Some have wood or plastic as lean-to covers to keep off the weather and some have straw mats to lie on. Others simply live in the open, sleeping in their dirty, tattered clothes on pieces of cardboard. Garbage is often piled nearby, and rats occasionally

slither over sleepers.16

Illness was naturally on the increase. In addition to dysentery and tuberculosis, refugees had a common vitamin deficiency called speuk, which caused a progressive loss of sensation in feet and legs until the person could no longer walk.

With political events of such magnitude occurring in Washington, few people were focused on events in Oudang, Pred Kdam, Kompong Luong, or even Phnom Penh. Ignoring the life-altering consequences of America’s war in Southeast Asia was not unusual for Americans. In voting down Article IV, the members of the Judiciary Committee effectively sanctioned that willful ignorance and denial and ensured that President Nixon would not face responsibility for the tragic events his invasion had set in motion. All the articles of impeachment that would be brought before the House were connected to the domestic crimes brought to light by Watergate. This meant that constitutional issues of the gravest importance would be overlooked in any impeachment proceeding.

During June 1974, one of America’s foremost historians, Henry Steele Commager, had warned against obscuring the deeper constitutional issues that were raised by the administration’s misconduct.17 Nixon had already won a strategic victory, he wrote, “in the realm of public, and perhaps even of Congressional opinion” by successfully “concentrating attention on Watergate and its associated chicaneries.” The minority on the Judiciary Committee who registered their dissent over the exclusion of Article IV expressed similar concerns:

By failing to recommend the impeachment of President Nixon for the deception of Congress and the American public as to an issue as grave as the systematic bombing of a neutral county, we implicitly accept the argument that any ends even those a President believes are legitimate justify unconstitutional means.18

After the fact, one could reasonably argue that the particulars of the impeachment articles made no practical difference what mattered was that the Judiciary Committee had found President Nixon guilty and unfit for office, and this finding had caused him to resign even before the House of Representatives could commence its deliberations. Yet by excluding foreign military activities from these articles, the committee framed how the events of that time have been remembered ever since. Although the illegal actions of

Nixon’s domestic officials were exposed the role of National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger was effectively spared congressional scrutiny or critique.

Shameful as the Watergate offenses were, they were hardly the most serious crimes. Yet they have largely determined the public’s historical understanding. The resulting amnesia has left intact many of the ideas, practices, and institutions that over decades have damaged the United States while inflicting needless suffering on foreign nations and people.

Fire and Rain takes as its subject the Nixon administration’s conduct of the war in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, and the resulting diplomacy with the Soviet Union and China. This reverses more familiar accounts, which assume that US military actions in Southeast Asia were the consequence of Cold War fears of the communist “superpowers.” While that description is arguably relevant to earlier decision-making, it is profoundly misleading when applied to the Nixon years. In fact, the administration’s mounting difficulties in solving its Vietnam problem increasingly shaped interactions with Moscow and Beijing.

Inevitably, the actions and thoughts of President Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger occupy a central place in this narrative. Given the already large and impressive literature on their conduct of foreign policy, an obvious question is why produce another study?19 The answer is paradoxical. On the one hand, the declassification of the extraordinary presidential tapes, along with the transcripts from thousands of Kissinger telephone calls, provides a close-up view of the two decision-makers that is without parallel in other administrations. On the other hand, the opportunity for this intense scrutiny has had the perverse effect of obscuring the role of other actors. To understand US policy during this period requires situating Nixon and Kissinger within the wider context of the people, the social and political institutions, the prevailing ideology, and the existing practices that framed their decision-making.

For all their distinctive qualities, both men were profoundly conventional in having reached their high positions by conforming to Cold War orthodoxy. Once in office, their management of the Vietnam War reflected the preferences of the national security bureaucracies most formidably the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington and the headquarters of General Creighton

Abrams in South Vietnam (Military Assistance Command Vietnam). Over time their close reliance on the career military would weaken, but in the beginning this was the expertise they trusted. Moreover, despite the sobering experience of the 1968 Tet offensive, at the outset of the administration there were no high-level voices within the executive branch pressing for a rapid end to the war. Within the State Department there was a lively interest in peace negotiations, but the advocates of diplomacy retained the hope that an independent. non-communist South Vietnam would emerge. Given that elusive objective, its members were held hostage to the imperatives of warfighting.

While illuminating the forces that propelled Nixon’s and Kissinger’s military measures forward, including an expansion of the US effort in Cambodia and Laos, Fire and Rain also examines the limitations imposed by public opinion and the organized peace movement. The narrowness of his 1968 electoral victory weighed heavily upon Richard Nixon, as did the political demise of his predecessor Lyndon Johnson. Throughout his first term, Nixon was plainly frustrated and angered by antiwar protest while at the time the impact of that protest on administration policy was ambiguous. However, decades of declassified records provide evidence that the waves of mass demonstrations, accompanied by growing resistance inside the military, ongoing electoral activity, and lobbying efforts on Capitol Hill imposed significant constraints on presidential decision-making.

The ensuing narrative pays considerable attention to the pivotal role played by Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird. To the outside world, he appeared to be another “hawk” in the administration’s leadership circle, but behind the scenes he was a relentless advocate of US troop withdrawals. Unlike other national security colleagues, Laird was first and foremost a politician. A reluctant appointee, he had served in the Congress for sixteen years and was, at the time of his selection, chairing the House Republican Conference. Although conservative in outlook, he was also keenly attuned to the mood of the public and was convinced that without major steps to exit the war, the president and his party would pay a steep political price.

To tell this history from the hallways of power in Washington DC, as well as the battlefields of Southeast Asia and the streets of America, this book is divided into two parts reflecting the surprising redirection in US policy during the spring of 1971. Part One: The War is focused on the Nixon administration’s approach to the fighting and the domestic ramifications of its

conduct. While expanding the American effort in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, the administration also adopted a program of “Vietnamization,” vigorously promoted by Secretary Laird. Under this rubric, tens of thousands of US troops were brought home in successive increments, accompanied by efforts to expand, equip, and train the South Vietnamese military so that it might function independently. For Henry Kissinger and top military officials this approach was folly, likely to undermine negotiations with North Vietnam and perhaps lead to defeat on the battlefield. From Nixon’s perspective, these troop withdrawals were a political necessity no matter the pitfalls.

Part I concludes with Lam Son 719, the South Vietnamese incursion into Laos in the spring of 1971. This is a riveting and important story, too often overlooked. The plan was for South Vietnamese troops, aided by American airpower, to cross the border and proceed to the strategically located town of Tchepone, where they would remain for a minimum of two months. If successful, this would cut off the movement of men and supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and prevent a major enemy offensive in the foreseeable future. The operation was regarded as a test case of Vietnamization, since for the first time the highly armed Army of the Republic of South Vietnam (ARVN) would be facing their North Vietnamese enemy without the support of US ground troops.

Despite high expectations, Lam Son 719 was a mortifying failure. Confronted by thousands of North Vietnamese soldiers, those from the South stayed briefly in Tchepone and then hurriedly fled Laos, some clinging to the skids of American helicopters. For administration officials it was an alarming demonstration of ARVN’s inability to fight on the ground, at a time when American air power was still available. From a public relations standpoint, the pictures of the retreating South Vietnamese made a damaging impression on the American public.

The debacle in Laos was closely followed by previously planned antiwar activities, largely focused on Washington. As viewed from the White House, the most theatrical and dangerous development was the appearance of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. During their week-long encampment, this disillusioned group brought their rebellion into the halls of Congress, punctuated by the eloquent address of Lieutenant John Kerry. Although votes were lacking in both the House and Senate to halt the war, it was evident that a continued policy of troop removals was necessary to prevent a majority from coalescing.

Part II: War and Diplomacy focuses on the period after Lam Son 719, when Nixon and Kissinger directed their attention to international diplomacy, and continues through the Paris Peace Agreement in January 1973. With their policy of Vietnamization imploding in Laos, the two went to extraordinary lengths to secure Chinese and Soviet assistance to extricate the United States from the war in a face-saving manner. During this entire time, Henry Kissinger’s negotiations with the North Vietnamese were entangled with his complex dealings in Moscow and Beijing.

“If, when the chips are down, the world’s most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world,” Nixon had famously warned.20 Sharing that apprehension, millions of Americans continued to support his administration and its conduct of the Vietnam War. Yet from the beginning, both Nixon and Kissinger were looking to the Russians for help in the region. Their initial strategy was to delay negotiations on other disputed issues pending Moscow’s cooperation on Vietnam. Yet this coercive approach had quickly proved fruitless. They had also hoped to open a relationship with the People’s Republic of China, but after the US invasion of Cambodia this effort had stalled.

Fortunately for them, in April 1971 the Chinese reversed their position, commencing with an invitation to the US ping-pong team to visit their country. Following this and other overtures, the Soviet government also adopted a friendlier stance. Suddenly, the time seemed ripe for diplomatic breakthroughs. Thus began a series of historic visits, starting with Kissinger’s clandestine trip to Beijing in July of 1971 and extending through two widely acclaimed summit conferences during the next ten months. For the country, these developments offered a welcome respite from the tensions of the Cold War and burnished Nixon and Kissinger’s reputations as international statesmen and men of peace.

In their memoirs, the two convey the impression that, by resisting communist advances in Vietnam and elsewhere, they had established the “credibility” to deal effectively with the Soviets and the Chinese. This was untrue. What the declassified record reveals is the extent to which both men’s positions on a range of issues, including nuclear arms control and the future of Taiwan, was driven by their need for assistance in obtaining a face-saving agreement to end the Vietnam War. Therefore, secrecy was of the utmost

importance. On key occasions, Kissinger chose to exclude American translators from high-level meetings in order to effectively conceal their content from his colleagues. More remarkable was his solicitation of Chinese and Soviet cooperation in deceiving Secretary of State William Rogers and other administration officials.

These efforts notwithstanding, improved relations with Moscow and Beijing had obvious benefits but they did not yield the desired results in Indochina. There is considerable evidence that diplomats from both countries encouraged the North Vietnamese to be more flexible in negotiations. Yet the Soviet and Chinese governments continued to provide substantial military and economic assistance to the North and failed to exert meaningful pressure on their ally.

This curious inversion of means and ends raises the broader question of whether US military and political intervention in Third World countries should be so readily described as a defensive response to an existential threat posed by the communist superpowers. In the specific case of the Vietnam War, the repeated alarms about US “national security” were increasingly at odds with reality. Even without declassified transcripts, the contradiction existed in plain sight: if Nixon and Kissinger were exchanging toasts with communist leaders in Moscow and Beijing, why did the killing in Southeast Asia continue?

Ultimately it was the killing and destruction that remain the heart of the story. During the Nixon period of the war, more than 20,000 American soldiers died, and between one and two million Asians, including Vietnamese North and South, Laotians, and Cambodians Fifty years later vast swaths of land remain poisonous; third and fourth generations of Vietnamese suffer grave birth defects from Agent Orange; and in Laos, the most heavily bombed country in the world, children continue to die from unexploded landmines.21 Some of this damage was inflicted before Richard Nixon became president, but the fire and rain from continuous air strikes and toxic chemicals reached a peak between 1969 and 1973.

While one objective of this book has been to describe and explain the policy choices that were made, a second and equally important objective has been to consider the impact of these choices on the lives of particular people. As vast as it is, the literature on the Vietnam War is oddly bifurcated. Many valuable historical studies of US decision-making exist, as well as a wealth of books that describe the devastating personal experiences of American

soldiers and of Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian civilians. However, telling one story without the other can often obscure the significance of each. In the case of the Nixon years, the vast collection of documents and tapes can seal the historian in the claustrophobic rooms where high officials deliberated, thus replicating their disconnection from the human consequences of their choices.

Much of the critical writing on the Vietnam War emphasizes the intellectual errors and misunderstandings of the otherwise “best and brightest” American leaders.22 However, in examining US policy during the Nixon period, this book argues that a key to the tragedy is less a failure of intellect than the selective vision of people in power. This not only included the president and his national security advisor, but also a host of subordinate officials whose jobs required a certain detachment from the places and people affected by US policy. Not seeing or learning about discomforting realities was often the prerequisite for career advancement.

This realization was brought home to me in an immediate way when traveling through Vietnam. The Cu Chi tunnels dark labyrinths, three layers deep, extending at one time from their origin 40 miles northwest of Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) to the Cambodian border have been turned into a tourist attraction. For decades thousands of Viet Cong moved in and out of these tunnels, launching military operations and retreating, exercising a mysterious political influence in the area that neither the South Vietnamese authorities nor the US military could thoroughly eradicate. How could anyone believe that these resourceful tunnel-dwellers would be intimidated by American military power?

Likewise, the Mekong Delta with its thick foliage threaded by rivers, canals, and streams, populated by hundreds of thousands of farmers and fishermen whose families had been there for generations offered a plethora of places for insurgents to hide. Could pacification work in such a place? And if it was temporarily accomplished, why would anyone expect it to remain permanent?

Of course, Nixon and Kissinger did not visit the stifling Cu Chi tunnels or paddle through the Mekong Delta, nor would either experience have changed their minds. Yet, in all the hours of their taped conversations and the thousands of transcripts and memoranda, there appears no sign of curiosity: What is it like there? What role is the Saigon regime playing in people’s lives? How are the inhabitants experiencing the war? And for the American

soldiers who found themselves in these unfamiliar, treacherous environments, what did counterinsurgency look like? As resistance and demoralization overtook the US Army, what experiences explained this?

In the Oval Office, an inability or unwillingness to imagine the experience of people directly affected by the violence of the war reached epic proportions during those years. It was clear that the bearers of bad news, whether coming from staff of the CIA or the State Department or from knowledgeable journalists, were unwelcome. Nor did Nixon or Kissinger wish to hear any negativity from the military, not even about the weather and its potential impact on bombing operations. Their reluctance to countenance bad news in any form made it nearly impossible for subordinates to provide reliable and urgently needed data. As an example of sheer willful blindness, it is difficult to equal the moment when, as millions of Americans were examining the horrifying photos of the My Lai Massacre, National Security Advisor Kissinger asked the secretary of defense if he should look at them.23

Unlike Kissinger, President Nixon was permanently attentive to the rumblings of the electorate, which was why he accepted Secretary Laird’s formula of Vietnamization. Despite ARVN’s dismal showing in Lam Son 719, the president continued to bring large increments of US troops home. To antiwar activists, it seemed incredible that the American public deemed Nixon a more reliable peacemaker than George McGovern. What many failed to appreciate was that by November 1972, more than half a million US soldiers had been withdrawn, with few combat troops remaining. The challenge for Nixon and his national security advisor was to forge a peace agreement that obscured the significance of the 140,000 North Vietnamese soldiers remaining in the South. As before, both men were prone to selfdeception, so in the post-election phase their moods oscillated between acute anxiety and unjustified optimism. In the case of the president, his assessments were also affected by the darkening clouds of Watergate.

Their self-perceptions notwithstanding, the Nixon administration’s conduct of the war in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia was a failure that yielded a tsunami of personal tragedies for both Americans and Asians. Yet nobody was ever held accountable. Apart from Nixon himself, those who devised and implemented the policy for these places continued in their public careers without significant disruption. One might have anticipated that certain lessons would be learned, such as the folly of invading a foreign country and seeking to impose a way of life and pattern of governance on the people who

live there. Yet this never became a guide to decision-making in the decades following Nixon’s presidency.

Herein lies the most challenging question in this book: How can leaders of a democracy conduct an extended war on behalf of a repressive, unpopular regime when the human costs are enormous and defeat seems likely? The answers are elusive and subject to debate. Hopefully the ensuing narrative will cast fresh light on the problem. But this troubling issue, unfortunately buried in the Nixon impeachment proceedings, remains now, as then, “not frivolous.”