ListofAbbreviations

ACABQ AdvisoryCommitteeonAdministrativeandBudgetaryQuestions

ATS AntarcticTreatySystem

DAC DevelopmentAssistanceCommittee(OECD)

DANIDA DanishInternationalDevelopmentAgency

ECHR EuropeanConventiononHumanRights

ECtHR EuropeanCourtofHumanRights

ECOSOC EconomicandSocialCouncil

EPTA ExpandedProgramforTechnicalAssistance

FAO FoodandAgricultureOrganization

FRUS ForeignRelationsoftheUnitedStates

GATT GeneralAgreementonTariffsandTrade

IBRD InternationalBankforReconstructionandDevelopment

ICJ InternationalCourtofJustice

IDA InternationalDevelopmentAgency

IHL InternationalHumanitarianLaw

ILO InternationalLaborOrganization

IMF InternationalMonetaryFund

IRS InternalRevenueService(US)

JIU JointInspectionsUnit

MDTF Multi-DonorTrustFund

NIEO NewInternationalEconomicOrder

NORAD NorwegianAgencyforDevelopmentCooperation

OCHA OfficefortheCoordinationofHumanitarianAffairs

ODI OverseasDevelopmentInstitute

OECD OrganizationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment

ONUC UnitedNationsOperationintheCongo

RAF RoyalAirForce(UK)

SADCC SouthernAfricanDevelopmentCooperationConference

SDGs SustainableDevelopmentGoals

SF SpecialFund

SIDA SwedishInternationalDevelopmentAgency

SUNFED SpecialUNFundforEconomicDevelopment

TA TechnicalAssistance

TAA TechnicalAssistanceAdministration

TAB TechnicalAssistanceBoard

TAC TechnicalAssistanceCommittee

UNCDF UnitedNationsCapitalDevelopmentFund

UNCTAD UnitedNationsConferenceonTradeandDevelopment

UNDP UnitedNationsDevelopmentProgram

UNDS UnitedNationsDevelopmentSystem

UNEF UnitedNationsEmergencyForce

UNEP UnitedNationsEnvironmentProgram

UNESCO UnitedNationsEducational,Scientific,andCulturalOrganization

UNFPA UnitedNationsPopulationFund

UNFSSTD UNFinancingSysteminScienceandTechnologyDevelopment

UNGA UnitedNationsGeneralAssembly

UN-HABITAT UnitedNationsHumanSettlementProgram

UNHCR UnitedNationsHighCommissionerforRefugees

UNICEF UnitedNationsChildren’sFund

UNIDO UnitedNationsIndustrialDevelopmentOrganization

UNODC UnitedNationsOfficeonDrugsandCrime

UNOPS UnitedNationsOfficeforProjectServices

UNRRA UnitedNationsReliefandRehabilitationAdministration

UNSC UnitedNationsSecurityCouncil

UN-WOMEN UNEntityforGenderEqualityandtheEmpowermentofWomen

USAF UnitedStatesAirForce

USAID UnitedStatesAgencyforInternationalDevelopment

USUN UnitedStatesMissiontotheUnitedNations

VCLT ViennaConventionontheLawoftheTreaties

WFP WorldFoodProgram

WHO WorldHealthOrganization

WTO WorldTradeOrganization

Introduction

AmongthedocumentsincludedintheUnitedNationsQuadrennialComprehensivePolicyReviewin2016wasareportfromRomeshMuttukumaru,aveteranof theUnitedNationsDevelopmentSystem(UNDS).Thereport’saimwastoproposehowUnitedNationsentitiesmightencouragememberstatestoreducethe conditionstheyplacedonfinancialcontributionstotheUnitedNationssystem. Expansiveuseofthese“conditions”led,forexample,to75percentoftheUScontributionstotheUNDevelopmentProgrambeingusedintwocountries,Iraqand Afghanistan.¹ Itled,forexample,tocontributionsfromtheFrenchGovernment skewingtowarditsformercolonialpossessions(theCentralAfricanRepublic, Vietnam,andHaiti).² Inshort,itoftenledtheUnitedNationstolooklikeacontractagencyforbilateralaid.AmongthepurposesoftheMuttukumaruReport wastodevelopasetofstrategiesthatwouldencouragememberstatestoprovidea largershareoftheircontributionsintheformof“core”resources,withoutstrings attached.

Thetopicwasafamiliarone;by2016,75percentofthemoneyflowingthrough UNDScameintheformof“non-core”resourcesthatwereearmarkedbythedonor foraspecificuse.Forthemostpart,thesewerenotlargepotsofmoneywith multipledonors.Nearly90percentofearmarkedcontributionstoUNDSwere single-donororsingle-projectcontributions.³ DisproportionaterelianceonearmarkedfundinghadbecomeasourceofconcernacrosstheUNsystem.Often expressedwithanaudienceofdonorsinmind,theseconcernsweretypically couchedinthelanguageofeffectiveness.TheJointInspectionsUnit,themainevaluationarmoftheUnitedNationssystem,hadconcludednineyearsearlierin2007 thatearmarkedcontributions“inhibitedsecretariatsoftheorganizationsintheir effortstodelivermandatedprograms.”⁴In2012,theEconomicandSocialCouncil releasedareportstatingthatearmarkedfunding“isoftenseenaspotentiallydistortingprogrampriorities.”⁵ TheWorldFoodProgramreportedthatearmarked aidpreventedtheorganizationfromcomplyingwithitsmandatetoprioritize

¹ UNDP,“TheUnitedStatesandUNDP:APartnershipthatAdvancesUSInterests.”See https:// www.undp.org/funding/core-donors/UnitedStates (accessedJuly11,2022).

² SeeUnitedNationsMulti-donorTrustFundOffice,availableat http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/ donor/00112 (accessedApril7,2020).

³ UnitedNationsMulti-donorTrustFundOffice2016,30.

⁴ Yusefetal.2007,ii.

⁵ UNGeneralAssemblyandECOSOC2012,12.

TransformingInternationalInstitutions.ErinR.Graham,OxfordUniversityPress.©ErinR.Graham(2023). DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198877936.003.0001

least-developedandlow-incomefood-deficitcountries.⁶ AttheOfficeforthe CoordinationofHumanitarianAffairs(OCHA),earmarksledsomeemergencies tobeoverfundedwhileotherswereleftwithoutresources.⁷ AndtheUNDevelopmentProgramitself—thecenterpieceofUNDS—identified“theearmarkednature offunds”as“amajorreasonfornon-deliveryofplannedoutputs.”⁸Eachstatement aimedtocommunicate,explicitlyorimplicitly,thatearmarkedfundingcauseda divergencebetweentheagreed-uponprioritiesofUNprograms,whetherthematic orgeographic,andtheworkthatUNentitiessupportedinpractice.

Thesourceofthisdivergencebetweenmultilateralprioritiesandresourceallocationlayinthegovernanceofearmarkedfunds,whichthevariousreportsalso sometimesmentioned,butoftenintechnical,bureaucraticlanguage.Earmarked fundsare“designedandimplementedoutsidetheorganisations’formalgoverningsystems(…),”⁹ theyare“notsubjecttodirectprogrammaticcontrolbythe governingbodiesofUnitedNationsentities,”¹⁰ andtheyare“notdirectlyregulatedbyintergovernmentalbodiesandprocesses.”¹¹ Reportslikethesetended nottoruminateonwhatitmeantthat75percentofUNDSresourceswere notsubjecttocontrolbyintergovernmentalbodies.Itwasherethatthe2016 MuttukumaruReportwasdistinct.DrawingadirectlinebetweenearmarkedcontributionsandUNgovernance,thereportconveyedtherealityinclearterms:“the continuingerosionofUNDScorefundingandtheresultingdependenceonnoncoreresourcestofinanceevenitsbasicmandatedactivities mayunderminethe multilateralcharacteranddemocraticnatureofthesystemasperitsCharter.”¹²

TheMuttukumaruReportwasnotthefirsttosuggesttheeffectsofearmarked contributionsextendedtofundamentalprinciplesofUNgovernance.In2010, TimoMahnoftheGermanDevelopmentInstituteauthoredabriefingpaper thatbegan:“ChangesinthefinancingofUnitedNationsdevelopmentcooperationaregraduallyerodingthemultilateralcharacterofUNdevelopmentaid.”¹³ Later,in2019,theUNsystemwouldspeakmoreclearlywhenadoptingitsFundingCompactaimedataddressingearmarkedfunds,aboutwhichtheCompact states:“Ultimately,theyunderminethemultilateralnatureofUnitedNations’” supportfordevelopment.¹⁴ Butthe2016Reportwasamongthefirstemanating frominsideTurtleBaytoproposethatwhat,formany,remainedatechnicalissue offundingmodalitieswasalteringthefundamentalnatureoftheUNsystem.Ifthe UNwasreluctanttoacknowledgethelink,itisunderstandable.Themultilateral

⁶ ExecutiveBoardoftheWorldFoodProgram2000.

⁷ Yusefetal.2007,13.JIU/REP/20071.

⁸ ExecutiveBoardoftheUNDP2013,4.

⁹ DANIDA2013,iii.

¹⁰ UNSecretary-General2012,20.

¹¹ UNGeneralAssemblyandECOSOC2012,12.

¹² Muttukumaru2016.Emphasisadded.

¹³ Mahn2012

¹⁴ UNGeneralAssembly2019,3(A/74/73/Add.1-E/2019/4/Add.1).

characteroftheUNisfundamentaltoitsidentity,tohowtheworldseesthe institutionandhowtheinstitutionseesitself.Morethanthat,theUNisidentifiedwithaparticularlyegalitarianvarietyofmultilateralism.OutsidetheSecurity Council,whererulesreflectpowerasymmetries,theegalitarianmultilateralismof theGeneralAssembly—one-country-one-vote—iscarvedinstoneintheUnited NationsCharter.ItisreplicatedacrossUNprogramsliketheUNDevelopment Program(UNDP),theUNEnvironmentProgram(UNEP),theUNChildren’s Fund(UNICEF),andtheWorldFoodProgram(WFP).EgalitarianmultilateralismdistinguishestheUNDSfromitsBrettonWoodscounterpart,theWorldBank, wherevotesaredistributedbasedoneconomicmight.ItalsomakestheUNthe preferredinstitutionalhomefordevelopingstates,whoenjoystrongmajorities, andisoftenaforumtobeavoidedbyitswealthiestmemberstates,whodonot.

TheseconceptionsoftheUnitedNationssystemhavenotchangedsignificantly inpastdecadesineitherthepopularimaginationorscholarlyresearch,yetthe systemhasquietlyundergonearemarkabletransformation.TheegalitarianmultilateralismsofundamentaltotheCharter,andtobasicunderstandingsofwhatthe UN is andhowitoperates,isstillpresentontherulebooksandinthedecisionmakingprocessesofvariousUNgoverningbodies.Butitdoesnotgovernthe vastmajorityofmoneythatflowsthroughthesystem.Multilateralbodiesdonot exercisedirectauthorityoverearmarkedcontributions.Astheproportionofearmarkedfundinggrows,theegalitarianmultilateralismofUNgoverningbodies controlsanever-shrinkingportionoftheUN’soperationalwork.BilateralcontractsnegotiatedbetweendonorsandUNentitiesgovernearmarkedfundsand sidestepegalitarianmultilateralism.

ThenatureoftheUN’stransformationposesaseriesofquestionsforinternationalrelations(IR)scholars.TheUNisoftendepictedasrigidandincapableof change.¹⁵ TheCharterwaslastamendedin1971.Thelegalbarrierstochange, whichrequiretwo-thirdsoftheGeneralAssemblytoapproveandratifyamendments,includingallpermanentmembersoftheSecurityCouncil,areprohibitively high.TheimpressionthattheUNhasnotchanged,andcannotchange,isreflected andreinforcedbyroutinecriticismfromtheUnitedStatesandotherscalling forreformstoimproveefficiencyandcoordinationyearafteryearwithoutever conveyingsatisfactionwiththeresults.Expressingawidelysharedview,onecommentatorquippedthattheCharter“bearslittlemoreresemblancetothemodern worldthandoesaMagellanmap.”¹⁶ YettodayUNfinancingbearslittleresemblancetoCharterrulesthatremainonthebooks.HowdidUNfinancingchangeso

¹⁵ E.g., IdrisandBartolo2000,85–86; Lipscy2017,18; HosliandDo¨rfler2019.HowardLaFranchi, “TheUnitedNations:IndispensableorIrrelevant?” ChristianScienceMonitor,September18,2020.

¹⁶ Citedin Buga2018,298–299.Foranexception,see Schlesinger(1997,50) whocallsthestandard critique,thattheUN“isaninflexibleinstitutionsetinitswaysandunwillingtochange,”a“mythworth exploding.”

radically?Equallyimportant,howwasegalitarianmultilateralism—afundamental principleofUNgovernance—compromisedandsidelinedalmostwithoutnotice?

Thesequestionsmotivatethebook.Iofferaframeworktounderstandtransformationalchangeininternationalinstitutionswheretransformationisdefinedas thereorganizationofrelationshipsamongkeyactorsandprinciplesofgovernance. ToexplaintheUN’stransformationfromaninstitutiondesignedwithrulesthat produceegalitarianmultilateralismtoonethatoperatesasystemofgovernance bybilateralcontract,Idevelopatheoreticalframeworkthatemphasizesthegradual,subterranean,anduncoordinatednatureoftransformation.IntheUNcase, Iarguethatincrementalchangesinfinancingrulesmadeinthelate1940s,and mostimportant,inthe1960s,madepossibleatransformationinUNgovernance inthe2000s.Often,thosewhoactedinearlierdecadesdidnotforeseeorintend theiractionstoenablethistransformation.

Despiteanextensiveliteratureoninternationalorganizations(IOs)inpolitical science,scholarlyinquiryintoquestionsoffinancingisrelativelynew.Thereare exceptions.TheUNfundingcrisisofthe1960s,withtheproximatecausebeingthe SovietUnion’srefusaltopayduesfortwopeacekeepingmissions,provokedscholarlyinterest.ProminentUNscholarChadwickAlgerpersuasivelyarguedin1973 thattheUSpreferredvoluntarycontributionstoenhanceitsinfluenceoverUN programs.¹⁷ DriveninlargepartbythegrowthinearmarkedfundingacrossIOs, sometimesreferredtoasmulti-biaid,non-core,orrestrictedfunding,IOfinancingscholarshipreemergedinthe2010s.¹⁸ Thisresearchilluminatesthebreadthof earmarkingtrendsacrossIOs,andtacklesquestionsaboutwhyearmarkedfundingissooftenthepreferredmodalityofstatesandprivateactors.Forthemostpart, thisliteraturefocusesonexplainingvariationinthecontemporarymomentrather thanchangeovertime.ButconsistentwithAlger’searlywork,manystudiesthat explainvariationinearmarkingbehaviorinagivensnapshotimplyanintuitive hypothesisaboutchange:Donorswantmorecontrolovertheircontributionsto IOsandearmarksareawaytoachievethis.

Onthesurface,thetimingoftheshifttoincreasedearmarkingappearsfavorable tothishypothesis.Moststudiesidentifythe1990sorearly2000sasthedecades earmarkstookoff.¹⁹ ThiscameontheheelsofwaningWesternsupportduring the1980swhentheGenevaGroup—agroupofUNmemberstatesthateachcontributemorethan1percentoftheUNregularbudget—enforcedapolicyofzero realgrowthacrosstheUNsystemformostofthedecade.Earmarksappearto answerwealthystates’frustrationwithwhattheyperceivedasinsufficientcontrol

¹⁷ Alger1973.

¹⁸ E.g., SridharandWoods2013; Graham2015; BayramandGraham2017; EichenauerandReinsberg2017; Graham2017; Michaelowaetal.2017; Reinsberg2017; Reinsbergetal.2017; Eichenauer andHug2018; Baumann2021; GrahamandSerdaru2020; Schmidetal.2021; Thorvaldsdottiretal. 2022.

¹⁹ E.g.,SridharandWoods2013,328–329;JenksandTopping2016;EichenauerandReinsberg2017, 172; Schmidetal.2021,435.

overtheircontributions.Inthistelling,theuptickinwealthystates’behaviorwould reflecttheirdesiretoexertcontrol.Butuponfurtherinterrogationthehypothesis isunsatisfyingintwoways.Itsfirstoversightistoignoretheimportanceofrules inenablingwealthystates’behavior.Thehistoricalrecorddemonstratesthatrule changeprecededsignificantbehavioralchange—bydecades.Voluntaryfunding ruleswerelayeredalongsidemandatoryones.Mandatoryruleswereinterpreted inmorerestrictiveways.Voluntaryrulesinitiallyprohibitedearmarks,butlater cametopermitthem.Inshort,thehypothesisthatpowerfuldonorssoughtto reassertcontrolinthe1990smakessenseasfarasitgoes,butwhywererules altereddecadesearliertopermitdonorearmarks?Didthesamestatespushfor rulechangeatthattime,onlytowaitdecadestotakeadvantage?Thispointstothe secondshortcomingofthehypothesis:theUN’smostpowerfulmemberstatesand largestsuppliersofmandatoryduesduringthetwentiethcentury,liketheUnited States,UnitedKingdom,Japan,andothers,didnotadvocateforrulechangesthat wouldpermitearmarks.Rather,thesechangescameatthebehestofothermember statesandnon-stateactors,oftenthoseassociatedwithapro-UNorientationlike Sweden,theNetherlands,andtheUNOfficeofLegalAffairs.Thesearenotthe actorswewouldtypicallysuspectofconspiringtoupendegalitarianmultilateralismattheUN.Infact,theydidnotconspiretodoso,buttheiractionssubstantially contributedtothatoutcome.

Focusingonpowerfulstates’assertionofcontrolthroughearmarkinginthe 1990smistakestheendoftheUN’stransformationforitsbeginning.Iarguethat theUN’stransformationwasgradual,takingplaceoverdecades.Incontrastto theconventionalnarrativethattracestheriseofearmarkedfundingtothe1990s, Iidentifyincrementalchangestofundingpolicyin1949,reinforcedin1958asthe beginningofagradualchangeprocess.Ilocatethedecadeofthe1960sasthecriticalperiodwheninstitutionalgroundworkthatenableddonors’behavioralchanges waslaid.Thesechangesinthemiddleofthetwentiethcenturycontributedto thetransformationofUNfinancingthatgatheredsteaminthe1990s.Ifurther arguethatthetransformativeprocesswasuncoordinatedovertimewithasubterraneandynamic.Byuncoordinated,Imeanthatactorswhomadedecisionsearly intheprocessthatprovedcriticaltotransformation,didnotforeseeoranticipatea transformativeoutcome,oractivelyworkwithactorswhowouldcarrytheprocess forwardatsubsequentmoments.Theprocessissubterraneanfromtheperspectiveofthosekeyactors.Inretrospect,thosewhoareidentifiedasenactingpivotal changeinthetransformationprocess,can,atthemomenttheyenactchange, genuinelyintendtheacttobe only incremental.Agradual,uncoordinatedchange processallowsthatthosewhosettransformationinmotioncandosounknowingly,andcandosoeveniftheywouldopposethedownstream,transformative effectsofthechangestheyenact.

Thisargumentrestsonaparticularsetofassumptionsaboutinstitutional design,rules,andagents.IncontrasttoprominentapproachesinIRthatfocus onthedesignchallengesposedbyrisk,theframeworkassumesthatinstitutional

architectsoperateindecision-makingenvironmentsthatarealsocharacterizedby genuineuncertainty.Thisassumptionisimportantconceptuallybecauseitrenderspassableunintentionalchangepathwaysthatwouldotherwisebeclosedoffor confinedtotheerrorterm.Buttheassumptionalsosquareswithempiricalreality. Asinternationalinstitutionsage,itbecomesmoredifficulttomaintainanassumptionthatactorswhoinitiallydesignedtherulescouldbereasonablyexpectedto anticipateallrelevantfuturestatesoftheworldandassignprobabilitiestothelikelihoodtheywouldoccur.Mostoftheinternationalorganizationsdesignedinthe periodbetween1945and1949persistinthetwenty-firstcentury,butfewwould maintainthatinstitutionalarchitectsofthateracould see twenty-first-century statesoftheworldfromtheirimmediatepostwarperch.Asearlyas1965,Rupert Emersonwrotethat“TheUnitedNationstwodecadesafterSanFranciscoisavery differentbodyfromtheoneitscreatorsfashioned,anditisareasonablepresumptionthattherewerenoneorvirtuallynonewhopresidedoveritscreationwho foresawevendimlywhatitwouldbecomeinthespanoftwentyyears.”²⁰ When evenamedium-termmetricoftwoorthreedecadesisused,institutionaldesignersoftencannotanticipatetheeffectsoftheirchoices,letalonedesigninstitutions forfuturestatesoftheworldtheycannotanticipate.

Thedownstreameffectsofinstitutionalrulesaresubjecttogenuineuncertaintybuttheyalsocontributetoit.Inadditiontotheirstandardfunctionas constraintsthatregulatebehavior,theframeworkofferedheretreatsrulesasinherentlypermissive.Thispermissivenessisnotonlytheproductofintentionaldesign asaccountsofstrategicambiguitysuggest,butisrootedinanunavoidablelinguisticindeterminacy.²¹ Itisalsoaidedbythepassageoftime;interpretationsand purposesthatwerenotconjuredinitiallycanbeinspiredbylatercontexts.Armed withrulepermissiveness,motivatedagentsarecapableofunpredictableaction. Theyforwardreinterpretationsandredeployrulesinwaysthatservetheircontemporaryendsbutwerenotanticipatedbythosewhodesignedtherulesand mayevenbeatoddswiththepurposestheyintended.

Thissetofassumptionsopensspaceforrethinkinghowinternationalrules change.Inmanyinternationalorganizations,negotiatingtherevision,amendment oroutrightreplacementofformalrulesisextremelydifficult,andnotinfrequently prohibitivelyso.Thesameisoftentrueforbodiesofinternationallaw.Yetinterstatenegotiationinwhichmemberstatesdebate,persuade,coerce,orbribeone anothertoenactmultilateralagreementremainsthedefaultmethodforthinkingabouthowchangeoccursinIOsorinternationaltreaties.Inthistraditional conception,whentherulesonthebooksarenotrevised,amended,orremoved, itiseasytoconcludethattheruleshavenotchanged.Scholarsofinternationallaw

²⁰ Emerson1965,484.

²¹ Greenstone1986; Schauer1991; Putnam2020,32.

pointoutthatempiricallythisissimplynotthecase.²²Thelawchangesmoreoften throughevolutivetreatyinterpretation,andsubsequentpracticethanthrough multilateral(re)negotiation.²³ Ifweexcludethesemechanismsofchangefromour conceptualtoolboxwemaymissnotonlyincrementalchange,buttransformation.

Inchaptertwo,Iintegratemechanismsofchangefrominternationallawwith historicalinstitutionalistthinkingongradualchange.IcontributetothehistoricalinstitutionalistresearchprograminIRbyarticulatingwhyandhowchangeof thissortoftenhasanunder-the-radar,subterraneandynamic.Drawingonmultiplearchivesacrosssixdecadesofthepostwartwentiethcentury,thebooktracks howfinancingruleswereaddedandreinterpretedatdifferentmomentsintime andfordistinctpurposesinwaysthatultimatelyfacilitatedashiftfromegalitarian multilateralismtogovernancebybilateralcontract,allwithoutanyrenegotiation ofCharterrulesthatgovernUNfunding.

WhyFundingMattersforMultilateralism

Pressedforwhichrulesaremostimportantfortheoperationofmultilateralism atinternationalorganizations,mostwouldreplybyfocusingonrepresentation ordecisionrules.²⁴ Inconventionalterms,multilateralisminvolvescollective decision-makingamongagroupofactors.Representationrulesdeterminewhich statesorotheractorsarerepresentedingoverningbodiesandallocatevotesacross representedparties.Decisionrulesdeterminethethresholdthatresolutionsor otherdecisionsrequireforpassage(e.g.,majority,supermajority,unanimity)and indoingsofacilitatecollectivedecision-making.Itisworthnotingthatthetwo pieces—agroupofactorsandcollectivedecision-making—gotogether.Whether onethinks20actorsengagedincollectivedecision-makingis more multilateral than10actorsdoingsoisopenfordebate,butneitherthe10northe20is“doing” multilateralismiftheymakeindependentdecisionsratherthancollectiveones.

Multilateralismiswidelyunderstoodtooperateasa“levelingprinciple”that, whilenoteliminatingpowerpolitics,hasarestrainingeffect.²⁵ Incontrasttoad hocbargaining,votingandrepresentationrulesensurevoiceopportunitiesand influencetoweakeractors.²⁶ Theserulesalsosignalegalitarianandinegalitarian“varieties”ofmultilateralism.²⁷ Egalitarianrulesallocatevotesequallyacross memberstates,regardlessofeconomicmightorotherfactors.Inegalitarianrules, likethoseattheInternationalMonetaryFund,orinternationaldevelopment

²² See Nolte2013,3; Buga2018

²³ Buga2018,4.

²⁴ E.g.,ThisviewispresentinprominentIRscholarshiponinstitutionaldesign,including Koremenosetal.2001,772; BlakeandPayton2015; Kaya2015,9; Lipscy2017,49.

²⁵ Ikenberry2003; Finnemore2005

²⁶ Kahler1992,681–682.

²⁷ Bayeretal.2015; Graham2015; Iannantuonietal.2021.

banks,allocategreatervoicetolargereconomiesandlesstosmallerones.Outside theSecurityCouncil,theUNsystemisamodelofegalitarianmultilateralism. Governingbodiesacrossitsprogramsandspecializedagenciesmakecollective decisionsbasedontheone-country-one-voteprinciple.

Ifrepresentationandvotingrulesaresoobviouslycentraltotheproduction ofmultilateralismatIOs,whydofundingrulesrequireattention?Theansweris thatfundingrulesdeterminewhethermultilateralgoverningbodiescontrolthe resourceallocationprocess.Nofundingruledeniesthatgoverningbodiesoperate inwaysconsistentwithmultilateralism,butwhilesomefundingrulesensurethat thosegoverningbodiescontrolresourceallocation,othersdonot.Inparticular, fundingrulesthatpermitearmarksallowforresourceallocationtobedetached frommultilateralcontrol.Thatcontrolshiftsfromthemultilateralbodytotheindividualdonor,whocandictatehowitscontributionisused.Putdifferently,funding rulesdetermine(andcanlimit)thereachofmultilateralgovernance.Basiclimits ondonordiscretionremain.IntheUNsystem,allfinancialcontributionsmust beusedforpurposesconsistentwiththoseoftherelevantorganizationorprogram,butthisleavesawideberthfordonorstofundbilateralpriorities,whether programmatic,geostrategic,orboth.Aslaterchaptersinthebookwilldemonstrate,rulesthatpermitearmarksdonotensurethatearmarkingitselfwillbea commonpractice.Itremainedrelativelyinfrequentformostmemberstatesuntil the1990s.Butwhilepermissiondoesnotensurethepopularityofthepractice, italsodoesnotlimititsuse.Rulesthatpermitearmarksgenerallydonotrestrict theportionofIOfundsthat can besubjecttoearmarks.Inshort,theymakepossibleasituationinwhichcontroloverresourceallocationistransferredentirely frommultilateralgoverningbodiestoindividualdonors.Suchanoutcomewould beextreme,butmostUNprogramsreceivemorethanhalfoftheircontributions intheformofearmarkedfunding,andforafewtheportionexceeds80percent. EarmarkedfundinglevelsatUnitedNationsagenciesandprogramsexceedthe levelsofotherIOs,includingtheWorldBankGroup.²⁸

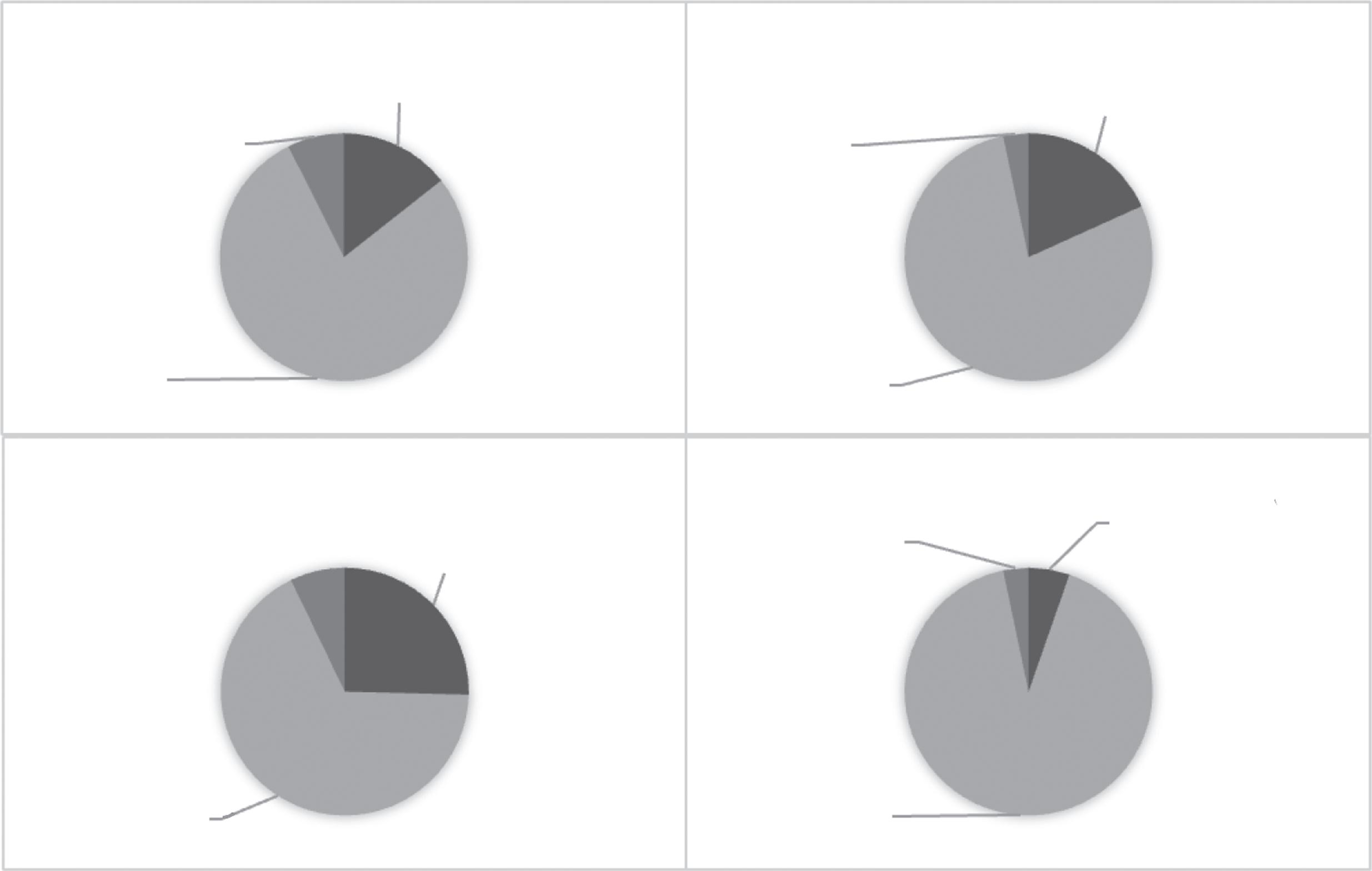

Figure 1.1 depictsfundingatfourmajorUNvoluntaryprograms:UNDP,the UnitedNationsChildren’sFund(UNICEF),theUNPopulationFund(UNFPA), andtheWFP.²⁹ Noneoftheseprogramsreceivesmoneyunderthemandatory assessmentsregimegovernedbyArticle17oftheUNCharter.Allcontributions frommemberstates(orfromotheractors)arevoluntary.Althoughtheportion varies,earmarkedfundingfarexceedsanyotherfundingtypeacrosstheprograms. Itrepresents93percentofallfundingtoWFP,82percenttoUNDP,73percentto UNICEF,and65percentofallfundingtoUNFPA.Itisonlytheremainingportion offunds,acombinationofvoluntarycoreresourcesandfees(7percentatWFP,

²⁸ Weinlichetal.2020,30.

²⁹ DataforFigures 1.1 and 1.2 arefoundin ToppingandJenks2021,31.

Figure1.1 FundingatSelectedUNVoluntaryPrograms.

Source: ToppingandJenks2021,31.

18percentatUNDP,27percentatUNICEF,and35percentatUNFPA)thatis governeddirectlybymultilateralbodies.

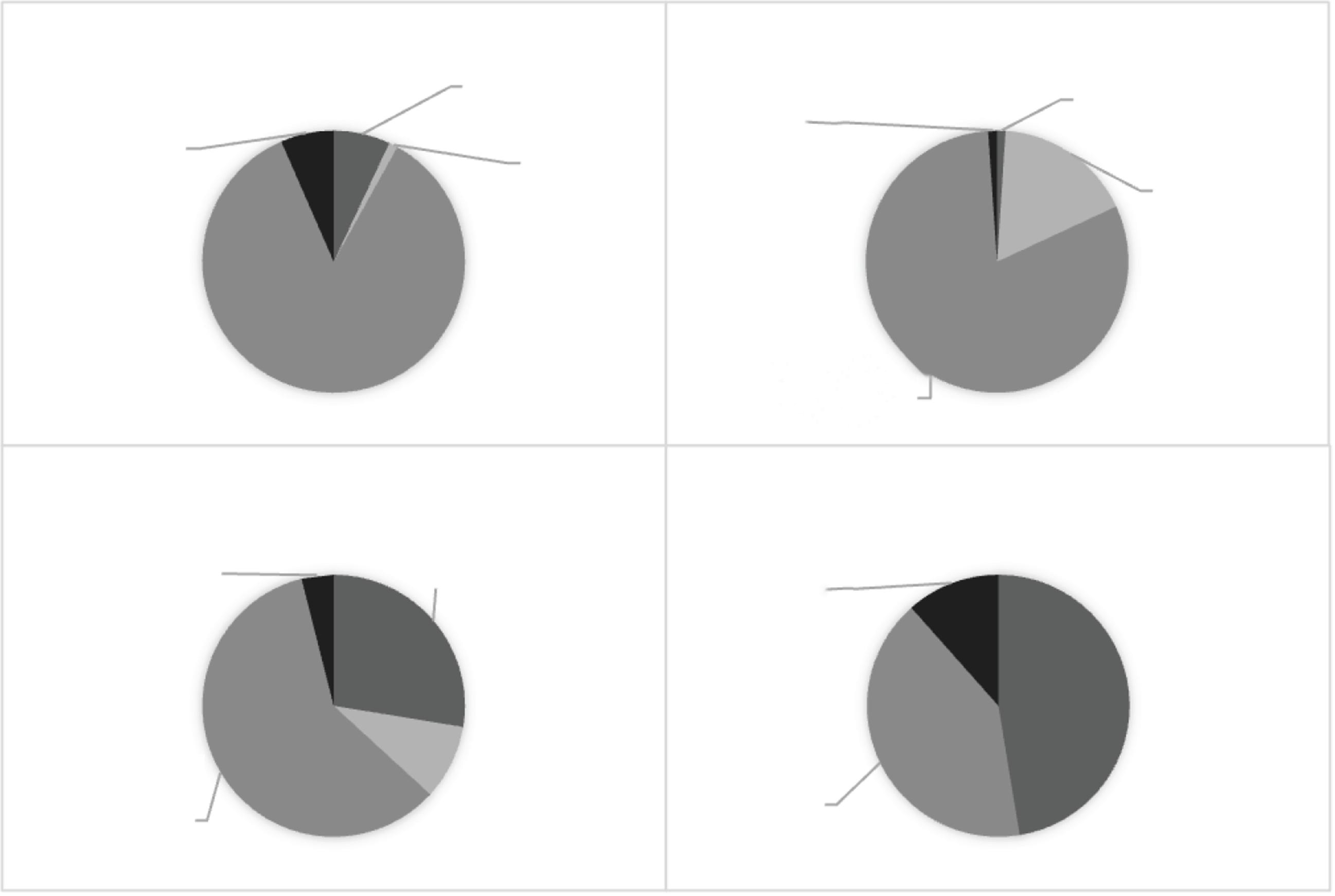

OtherUNprogramsreceivemoneyfromthemandatoryassessmentssystem governedbyArticle17oftheUNCharterbutthisgenerallyrepresentsasmall portionoftheirfunds(seeFigure 1.2).Forinstance,earmarkedfundingrepresents86percentofallcontributionstotheUNOfficeonDrugsandCrime (UNODC),and83percentofthecontributionstotheUNHighCommissioner forRefugees(UNHCR).WhenUNprogramslikeUNODCandUNHCRareeligibleformandatorycontributions,theiruseistypicallyconfinedtoadministrative costsratherthanoperationalactivities.TheUNEnvironmentProgramstandsout; itsproportionofearmarkedfundsstandsatjust57percentalongside33percentin mandatorydues,and9percentfromvoluntarycorecontributions.³⁰ Remarkably, evenattheUNSecretariat,theprimaryrecipientofmandatoryfundsfromthe regularbudget,earmarkedcontributionsaccountfornearlyhalf(48percent)of allfunding.

Thesefiguresmakeclearthatearmarkedfundingisaprevalent,andevendominantfundingmodalityacrosstheUNsystem.TheyalsoclarifythattheUN’s multilateralismgovernsarelativelysmallportionofthemoneythatflowsthrough

³⁰ UNEPremainsasmallprogramrelativetoitsdevelopmentcounterparts($742millionversus $5517millionatUNDP);italsobenefitsfromanagreementbetweentheGeneralAssemblyandthe UNEPGoverningCouncilin2012toreversetheriseofearmarksand“shifttowardsunearmarked funding.”Sincethattime,UNEP’sregularbudgetallocationhasgrownfrom$12.1millionin2012–13 to$247millionin2018–19.

Figure1.2 FundingatSelectedUNProgramsThatReceiveMandatory Contributions.

Source: ToppingandJenks2021,31.

thatsystem.Mostfundsaregovernedbycontractsdesignednotbymultilateral governingbodies,butbydonorsinnegotiationwithUNofficials.Thesearecustomizedtofitthepreferencesofthedonor(ordonors)regardingnotonlythe purposeandproject,butalsotermsofsupport,reportingrequirements,andevaluationmetrics.OfthesametypeofearmarkedtrustfundsattheWorldBank, Reinsbergexplainsthat,“donorshavegreatleverageinthedesignstage(…)donors cannegotiateindicativepreferencesintotheadministrativeagreementthatBank stafftryto(andusuallydo)satisfy.”³¹ Manycomparethegovernanceofearmarked fundingtobilateralaid,essentiallymakingtheUNacontractagencyforthedonor government.ThisisreflectedinthelanguageusedbyUNprogramsanddonor governmentstorefertoearmarkedfunds.Denmark’saidagency(DANIDA)distinguishesbetween“assistancetomultilateralorganizations(corefunding)”and “bilateralassistancethroughmultilateralorganizations(earmarkedfunding).”³²

TheWorldFoodProgramreferstoitsearmarkedfoodaidas“restrictedforusein specificprovincessupportedbilaterallybythedonorconcerned.”³³ Incontrastto multilateralaidwhereresourcesarepooledandtheidentityofindividualdonors disappears,earmarkedfunding“preservesthenationalidentityofagrantor

³¹ Reinsberg2017,91.

³² DANIDA2013,emphasisadded.

³³ ExecutiveBoardoftheWorldFoodProgramme,2000,36.

concessionaryloan.The‘lightofsight’fromsourcetoresultsensuresthatcontributionscanatalltimesbeconnectedtothedonorthroughplanningframeworks, accountabilitymechanisms,andvisibility(…)”³⁴

PermissivefundingrulesareafeatureofthecontemporaryUN’sinstitutional design.Thoserulesmakepossiblethestatusquo:thatamassofindividualized contractsgoverntheworkofUNoperationalprograms.Thiswasnotalways thecase.Technicalassistanceprograms,thepredecessorsof“socialandeconomicdevelopment”workattheUN,wereinitiallyfundedbymandatoryassessmentsundertheregularbudget.WhenearlyUNdevelopmentprograms,likethe ExpandedProgramforTechnicalAssistance(EPTA)andtheUNSpecialFund wereestablishedtorelyonvoluntarycontributions,rulesprohibiteddonorsfrom placingearmarksontheircontributions,ensuringthatmultilateralbodiescontrolledresourceallocation.³⁵ Earmarkprohibitionsbegantodisappearonlyinthe mid-1960s.Thetransitiontodisproportionaterelianceonearmarkedcontributionscamedecadeslater.Thisshiftoccurreddespitenochangewhatsoeverinthe votingandrepresentationrulesthataresocloselyassociatedwiththeproductionofmultilateralismattheUNandotherinternationalorganizations.Thatthe changeoccurredthroughfundingrulesmeantthatitwassubterranean,occurring belowthesurface,whiledecision-makinginUNgoverningbodies—thosebastions ofegalitarianmultilateralism—continuedundisturbed.

RethinkingHowInternationalRulesChange

Thisbookisinterestedintwotypesofchange:changeinformalinternational rules,andthetransformationoffundamentalprinciplesembeddedininternationalorganizations.InconventionalaccountsinIR,internationalruleschange throughnegotiation,followedbyamendmentorreplacement.Forinstance, DeBruyneetal.articulateandoperationalizerulechangeintheconventional way:“Whilethemajorityoftreatiestendtoremainunchanged,othersarerenegotiatedovertime,eithergraduallybytreatyamendmentorabruptlybytreaty replacement.”³⁶HaftelandThompsonsimilarlyequaterenegotiationwithchange: “Whilesomeagreementshaveremainedintactaftertheirinitialconclusion,othersareamended,updated,orreplaced.Whyaresomeinternationalagreements renegotiatedwhileothersremainstable?”³⁷ Inthisconception,changeissynonymouswithamendmentorreplacementandrulesremainunchanged,“stable,”

³⁴ Weinlichetal.2020,27.

³⁵ ECOSOC1949.Resolution222(IX),pp.7–8.August14–15,1949.ECOSOCresolutionadopted bytheGeneralAssemblyestablishingEPTAinResolution304(IV)November16,1949.Seealso:UN Yearbook1948–49,444. https://www.un.org/en/yearbook

³⁶ DeBruyneetal.2020,321.Theconventionalconceptionofhowchangeoccursisoftenimplicit andtakenforgrantedratherthanexplicitlystated.

³⁷ HaftelandThompson2018,25.

whentheseactsdonotoccur.Thechangeprocessisfurthercharacterizedbytwo features,oftentakenforgrantedratherthanexplicitlystated.First,itisunderstood tobeintentional,thatis,actorsdesignandredesignrulesinresponsetoproblems, withtheaimofsolvingormitigatingthoseproblems.Second,theprocessandoutcomearerelativelytransparent.BythisIdonotmeanthatthepublicisprivyto privateconversationsofdiplomatsthatmaymakeorbreaknegotiations,butrather thatrulechangeitselfisvisibleonthepage.Putanotherway,whenwetreatrules asontologicallyclosed,rulemeaningremainsstaticabsentaliteralrewritingof therulesthroughrevisionoramendment.

Ifrulesareinsteadtreatedasinherentlypermissive—ontologicallyopen—then meaningcanchangeevenifthewrittenwordsdonot.Decipheringrulemeaning requiresinterpretationandcannotbededucedfromwordsalone.³⁸ Thismeans boththatasinglewrittenrulecansupportmultipleinterpretationsatanygiven moment,andthatmeaningmaychangeovertime.Equatingchangewithrenegotiationandidentifyingchangeasamendmentorrevisionislikelytomissmuchof theaction.Thistreatmentofinternationalrulesaspermissiveisconsistentwitha newbodyofworkattheintersectionofIRandinternationallawthatunderstands internationallawasunsettled,“momentaryachievements,”thatcan“remainsubjecttocontestation”aftertheyarecodified.³⁹ Itsimilarlyallowsthatthesame rulemightbeusedformultiplepurposes,apremiseofhistoricalinstitutionalist scholarshipontransformationalchange.⁴⁰

Howdomeaningandpurposechangeabsentrenegotiation?Internationallegal scholarshipilluminateshowrulesoftenchangethroughreinterpretationrather thannegotiation.Theseinterpretivetoolsincludeevolutivetreatyinterpretation, subsequentpractice,andreadingonebodyoflawthroughanother.TheUnited NationsCharterincludesjustoneArticle,Article17,thatpertainsexplicitlyto funding.Itgovernsthemandatoryassessmentssystem,obligatingmemberstates topay“theexpensesoftheOrganization.”SubsequentpracticehasbeenparticularlyimportanttoreinterpretingArticle17tolimittheexpansionofthemandatory system.TheViennaConventionontheLawoftheTreaties(VCLT)codifiedsubsequentstatepractice,thatis,statebehaviorrelatedtothelawinquestion,asan interpretivetool.Subsequentpracticeisusedtoinferstatesparties’understandingoftreatyobligations.Ifsubsequentpracticeevolvesovertime,sotoocan treatyobligationsevolvetoreflectstates’understandings,asinferredfromtheir behavior.Subsequentpracticesquareswiththeframework’sassumptions.Asan interpretivetool,itisintendedtobeusedwhenstatespartiesintendtheirbehaviortoreflecttheirunderstandingofthelaw.Inpractice,ofcourse,whetherastate intendeditsbehaviortosignalitsunderstandingofthelawisdifficulttoevaluate.

³⁸ Putnam2020

³⁹ Mantilla2020,9.

⁴⁰ Hacker2002; Pierson2003; Thelen2003, 2004; MahoneyandThelen2010; St.John2018.

Legalanalysisrevealsthatruleinterpreters,whetherinternationalcourts,orstates partiesforwardinginterpretations,makeargumentsandrenderdecisionsbased onsubsequentpracticeevenwhenstatesengagedinthepracticedidnotexplicitly intendtheirbehaviortosignaltheirinterpretation.⁴¹ Legalargumentstojustify withholdingduestotheUN,madetoconsiderablesuccessinthe1970sand 1980sasWesternsupportfortheUNdeclined,reliedonsubsequentpracticeto reinterprettheChartertorestrictthereachofArticle17.Thisconstrainedthe UN’strajectory.Argumentsinfavoroflegalwithholdingeffectivelysealedoffthe mandatoryassessmentssystemasasourceofgrowthfortheUN,makingany futuregrowthreliantonvoluntarycontributionsbydefault.

Permissiveearmarkrulesalsochangedovertime,butrepurposingratherthan reinterpretationservedastherelevantmechanism.Underliningtheimportance ofgenuineuncertaintyinmakingchangepossible,repurposinginvolvesusing existingrulestoachieveendsthatarenewanddistinctfromthoseimaginedby theiroriginaldesigners.AfirststepinthisprocessoccurredwhentheUNOffice ofLegalAffairsrepurposedrulesdesignedtoprovidetheSecretary-Generalwith discretiontoacceptcontributionsforspecificpurposesfromprivateactors,and redeployedthemtoallowtheUNDPtoacceptearmarkedresourcesfromamemberstate.ThesecondstepoccurredwhentheUnitedStatesrepurposedearmark rulesoriginallydesignedtoprovideadditional,supplementaryfundingtoUN programs,toconstrainthoseprogramsandlimitmultilateralcontrol.Thebook makesthecasethatreinterpretationandrepurposingareasimportanttounderstandingchangeininternationalrulesasrenegotiationandrevision.Theydo notinvolvechangesinwrittentext,renderingthemlessvisible,butarenoless importanttoinstitutionaldevelopment.

Ultimately,thebookisinterestednotonlyinchangesinindividualrulesbutin howthosechangestransformedUNgovernance.Itscentralargumentisthatthe UN’stransformationwasmadepossiblebytherelativeinvisibilityoftheprocess. Unlikerepresentationandvotingrules,fundingruleswerenotwidelyperceived tohaveadirectrelationshiptomultilateralism.Inpartbecauseofthis,andinpart becausechangestofundingrules—whetherreinterpretationsofArticle17,the introductionofvoluntaryrules,orthedisappearanceofearmarkprohibitions— wereinitiallymadeforreasonsunrelatedtomultilateralism,thetransformation hadasubterraneandynamic.Itwasnotforeseenuntilitwaswellunderway. Lowvisibilitymeantthatchangestofundingrulesdidnotimmediatelymobilize oppositionfromthosewithastakeinthepersistenceofegalitarianmultilateralismattheUN—agroupthatincludesmostdevelopingcountriesandmakesup

⁴¹ Forthegeneralargumentsee Nolte2013; Buga2018.Forspecificcases: Hassanv.UnitedKingdom (EuropeanCourtofHumanRights); CertainExpensesAdvisoryOpinion (InternationalCourtof Justice).

themajorityofUNmemberstates.Transformationoccurredinpartbecauseit wasunforeseenbythosewhosetitinmotion.

Thisprocessbuildsontheoriesofgradualtransformation,firstdevelopedin AmericanandcomparativepoliticaldevelopmentthatarenowemerginginIR.⁴² Forinstance,inexplainingtheriseofinvestor-statearbitration,TaylorSt.John arguesthatthegroundworkforthetwenty-first-centuryinvestor-statedisputesettlementwaslaiddecadesearlierinthe1960sbyactorswho“didnotintendto create”thesystemasitexiststodayandinfactwouldlikelybe“horrified”byit.⁴³ LikeSt.John’sargument,theframeworkofferedhereisdistinctfromconventionalunderstandingsofinstitutionaltransformationthatemphasizepunctuated change,oftenatmomentsofhistoriccriticaljuncture.Inthosemoments,bold,radicalrevisionispossible.Gradualtransformationdoesnotrequiresuchmoments butthechangeitushersinisnolessradical.

Contributions

Theoretically,thisbookcontributestoagrowingliteraturethatemphasizestiming andsequence,contingency,andcreativityinexplaininginternationalinstitutional originsandchange.Variousstrandsofthisworkwearthelabelsofhistorical institutionalism(HI),practicetheory,andideasscholarship,buttogetherthey shareacommitmenttothestudyoftheprocessthroughwhichoutcomesareproduced.HIhasgainedtractioninIRinthepastdecade,⁴⁴ andthisprojectaims tomoveitforward.IRscholarshaveintegratedusefulinsightsfromtheHItradition,especiallydrawingonargumentsaboutpathdependence,illuminatingwhy internationalinstitutionssooftenresistchange.HIinsightsintohowinstitutions transformhavereceivedlessattention.⁴⁵ Iemphasizethesubterranean,uncoordinatednatureoftransformation.Thetransformativeprocessdoesnotexistassuch forthosewhoparticipateinitsearlyphases.Genuineuncertaintymakespossibleactors’participationinsuchaprocess.Permissiverulesandactors’abilityto exploittheminunpredictablewaysmakespossibleunexpectedturnsinrule-use andinterpretation,andfeedsgenuineuncertainty.

Empiricalaccountsofgradualtransformationofteneschewathoroughdiscussionoftheoreticalfoundationsthatmaketransformationalchangepossible. Convincingempiricalaccountsofgradualtransformationareessential,butthe decisionnottoelaboratetheassociatedtheoreticalfoundationsundercutsthe

⁴² IRscholarshavemoreoftenutilizedHI’sconceptofpathdependencetoexplainpersistencerather thanimportingHIargumentsaboutgradualchange.Forexamplesthatutilizeelementsofgradual changeargumentsfromHI,see St.John2018 and Pouliot2020.

⁴³ St.John2018,4.

⁴⁴ E.g., Fioretos2011; Rixenetal.2016; Fioretos2017

⁴⁵ Exceptionsinclude Posner2009; Chwieroth2014; FarrellandNewman2015; St.John2018.

challengethattheseempiricalstoriesposetorationalisttheoriesofdesignand changethatremainpredominantinthediscipline.Thisbookanswersthecallfrom numerousscholars⁴⁶toforwardacoherenttheoreticalframework.Genuineuncertainty,permissiverules,andcreativeagentsmakepossiblegradual,subterranean transformation,andprovideanalternativetorationalistaccountsinthefield.

Thebookalsocontributesbyintegratinglegalinterpretivestrategieselaborated inInternationalLaw(IL)scholarshipintoHIandIRaccountsofinstitutional change.IRhasbenefitedfromcross-fertilizationwithILresearchgenerally,andIR scholarshiponinternationalcourtsrecognizestheimportanceofinterpretation. Buttheinterpretivetoolsthatinternationallawyersknowtofacilitatechangehave receivedscantattention.⁴⁷ Theseinterpretivetools,especiallysubsequentpractice asoutlinedintheViennaConventionontheLawoftheTreaties,renderbehaviorswethinkofasnon-legal(i.e.,nothavinglegalimplications)relevanttowhat internationalrulesmean.Equallyimportant,interpretiveargumentsthatrelyon thesetoolsareregularlymadebyactorsotherthaninternationalcourts,including statesseekingtolegitimatetheirpositionsthroughlegalarguments.⁴⁸ Learning aboutinterpretivetoolsenrichesIRscholarshiponchangetheoreticallyandalso helpstoclarifythatrulemeaningoftenchanges,sometimesradically,withoutthe negotiationandrevisionprocessenvisionedbyIRscholars.

Empirically,thisisabookabouttheUnitedNations,aboutwhatit is andhow itworks.IntheimmediatepostwarperiodpoliticalscientistspaidampleattentiontotheUN,butasdecolonizationprogressed,UNmembershipexpanded, anditsplaceinUSforeignpolicydiminished,itspopularityasasubjectofIRscholarsdeclined.ThisisparticularlytruefortheUNsystemoutsidetheUNSecurity Council(UNSC),whereaninterestinCouncildecisionsandpeacekeepingkept theUNnamebothintheheadlinesandinscholarlyjournals.⁴⁹ Booksthatdo focusprimarilyontheUNsystemoutsidetheUNSCareoftenprimarilynormative enterprises,oftenwithapolicyfocus.⁵⁰AndmanyofthesefocusonindividualUN programsratherthanthesystemwritlarge.Bycontrast,thisbookanalyzesthegovernancetrajectoryoftheUNfromitsestablishmenttothecontemporaryperiod andtrackssystem-widetrendsinitsfinancingandtheireffects.Basedonarchival research,itshedsnewlightontheUNCharter,andonhowdecolonization shapedtheUNDS.Italsooffersacompellingsolutiontoalong-standingpuzzle ofthepost-1980sUnitedNations.Wealthystates,fedupwithever-increasingregularbudgets,implementedstringentausteritymeasuresontheUNinthe1980s,

⁴⁶ See Fioretos2011; MoschellaandTsingou2013; Pouliot2020,745.

⁴⁷ Forexceptions,seeDunoffandPollack2018; BúzásandGraham2020.

⁴⁸ Murphy2013,83.

⁴⁹ Importantexceptionsincludeworksthatstudy(re)alignmentsininternationalpoliticsbyanalyzingGeneralAssemblyvotingpatternsandrhetoric(e.g., Voeten2000; KentikelenisandVoeten2021) andstudiesfocusedonvotebuying(e.g., Dreheretal.,2008; CarterandStone2015).

⁵⁰ E.g., Murphy2006; Browne2012; Ivanova2021.

withsomememberstatessuggestingtheymightleavetheinstitutionaltogether.⁵¹ Butinsteadofshrivelingup,theUNDSexpandedrapidly.Thebook’semphasis onfinancingdemonstrateshownearlyallpost-ColdWargrowthintheUNsystemispoweredbyearmarkedfunds.WealthystatesdidnotleavetheUN,butmany radicallyalteredtheirengagementbychanginghowtheyprovidefunding.

ThesechangesrendertheUNlargerandstrongerinmanyways,butgovernanceisalsoqualitativelydifferentthantheegalitarianmultilateralismsoclosely associatedwiththeUN.Earmarkedfundingandgovernancethroughbilateral contractaffectfarmorethanresourcedistribution.WithinUNbureaucraciesthey necessitatecapableresourcemobilizationdepartmentstoattractfundingandsupportdonorrelations.TheyimplicatethelegitimacyofUNfundsandprograms. ThelegitimacyofIOsispremisedonbothoutcomesandproceduralcomponents, includingwhetherproceduresare“fair”and“democratic.”⁵² Pouliotemphasizes the“processualadvantages”ofmultilateralismasaninstitutionalpracticethatlend legitimacytopolicyoutcomesoftheprocess.⁵³ Governancethroughbilateralcontractraisestheseconcernsaboutfairnessandparticipationand,morepointedly, aboutdevelopingstateslosinginfluence,andtheseconcernshavegrownasearmarkingpracticesbecomemorewidespread.⁵⁴Theconcludingchapter,Chapter7, laysouttwomodels—onedonordrivenandonedrivenbyagencystaff—for thinkingaboutUNprogramsandagenciesasactorsinworldpoliticstoday.

PlanfortheBook

Chapter2introducesinternationalrelationsliteratureoninstitutionalchangeand identifiesitslimits:itsreluctancetoaddresstheshortcomingsoffunctionalismand itsemphasisonpunctuatedequilibriummodelsinunderstandingmajorchange. Idefinetransformationandofferadistincttheoreticalframeworkforexplaining howitoccursbuiltontheassumptionsofuncertainty,permissiverules,andcreativeagents.IintegrateinterpretivemechanismsfrominternationallawintoanHI frameworktoilluminatehowincrementalrulechangecanproducetransformation.Iarticulateasetofobservableimplicationsthatfollowfromtheframework’s assumptionsandmechanismsofchange.

Thenextfourchaptersillustratehowtransformationalchangeoccurredatthe UNanddemonstratetheframework’sempiricalpurchase.Chapter3centerson negotiationsoverthedesignoftheUNCharterduringandfollowingWorldWarII. ItprovidesanaccountofthecorerulesintheCharterthatproduceegalitarian

⁵¹ OnleavingIOs,see vonBorzyskowskiandVabulas2019.

⁵² ScholteandTallberg2018,7–9.

⁵³ Pouliot2011,23.

⁵⁴ See GrahamandSerdaru2020,694; Weinlichetal.2020.

multilateralism.Iaddressnotmerelywhattherulessay,butalsotheirintended meaningbasedonthearchivalrecord,andmemoirsanddiariesoftheprincipalnegotiators.Thisprovidesanimportantbasisforevaluatinganysubsequent reinterpretationofCharterrules.Chapter3alsoprovidesthefirstopportunityto evaluatetheframework’sobservableimplicationsregardingthedecision-making environment.Ifdesignersoperateinaworldofrisk,theycanidentifypotential downstreamstatesoftheworldthatareassociatedwiththeirrulechoices.Wesee, bycontrast,thatthefuturewasopaquetoUNarchitectsinimportantways;they didnotforeseeaworldinwhichGeneralAssemblycontroloverfinancialmatters wouldbeproblematic.

Chapter4coverstheperiodbetweentheUN’sfoundinganditsfirstmajorbudgetcrisisin1960.Twocriticaldevelopmentsoccurduringthisperiod.Thefirst involvedtheintroductionofvoluntaryfundingrulesforeconomicdevelopment activity.Inretrospect,theserulesprovideaclear,firststepawayfromegalitarian multilateralismembeddedintheCharter.ButIdemonstratehow,atthetime,their introductionwasnotintendedtodrivesuchashift.Instead,voluntaryruleswere introducedtoexpandUNactivitydespiteoppositionfromcriticalstates,especially theSovietUnion.Thisspeaksdirectlytothetheory’semphasisontheimportance ofsmall,technicalchangesingradualprocessesoftransformation.

Chapter5coversthecrucialperiodinwhichpermissiveearmarkruleswere adoptedattheUnitedNationsDevelopmentProgram.Aswiththeintroduction ofvoluntaryrules,permissiveearmarkruleswerenotintendedtotransformUN governanceandwerepursuedbyactorsperceivedtobebenigntothesystem (e.g.,theNetherlandsandSweden).Butthechapteralsousefullydemonstrates how,facedwithconstraints,creativeactorsaccessrulepermissivenesstocreate somethingnew.FacedwiththepredicamentofhowtomaketheNetherlands’contributioncompliantwithUNDPrules,theUNOfficeofLegalAffairsrepurposed afinancialrulethatexistedelsewhereontheUNbooks.ThecreativerepurposingwasconsolidatedintoUNDPrulesinanunremarkableresolutionin1967. Thechapterdemonstratesboththatpermissiveearmarkrulessetthestageforthe UN’stransformationandthatatthetime,transformationwasnotintended.

Chapter6,whichcoversthe1980s,illustratesprocessesofreinterpretationand repurposing,thelatterwithanemphasisonsubsequentstatepractice,articulated inthetheoreticalframework.AstheUN’stransformationispursuedinearnest bytheReaganadministration,thechapterillustrateshowthattransformation emergedgraduallythrough uncoordinatedactions byvariousactorsovertime. Changeisuncoordinatedinthesensethat,forexample,theNetherlandsorthe UNOfficeofLegalAffairshardlyhadtheReaganadministration’sstrategyinmind whenthey“found”awayforUNDPtolegallyacceptanearmarkedcontribution. Nevertheless,USAmbassadortotheUNJeaneKirkpatrickutilizedopportunities createdbytheseactionstwodecadeslater.The1980sendwiththemandatory assessmentssystemeffectivelycappedandearmarkedfundingontherise.