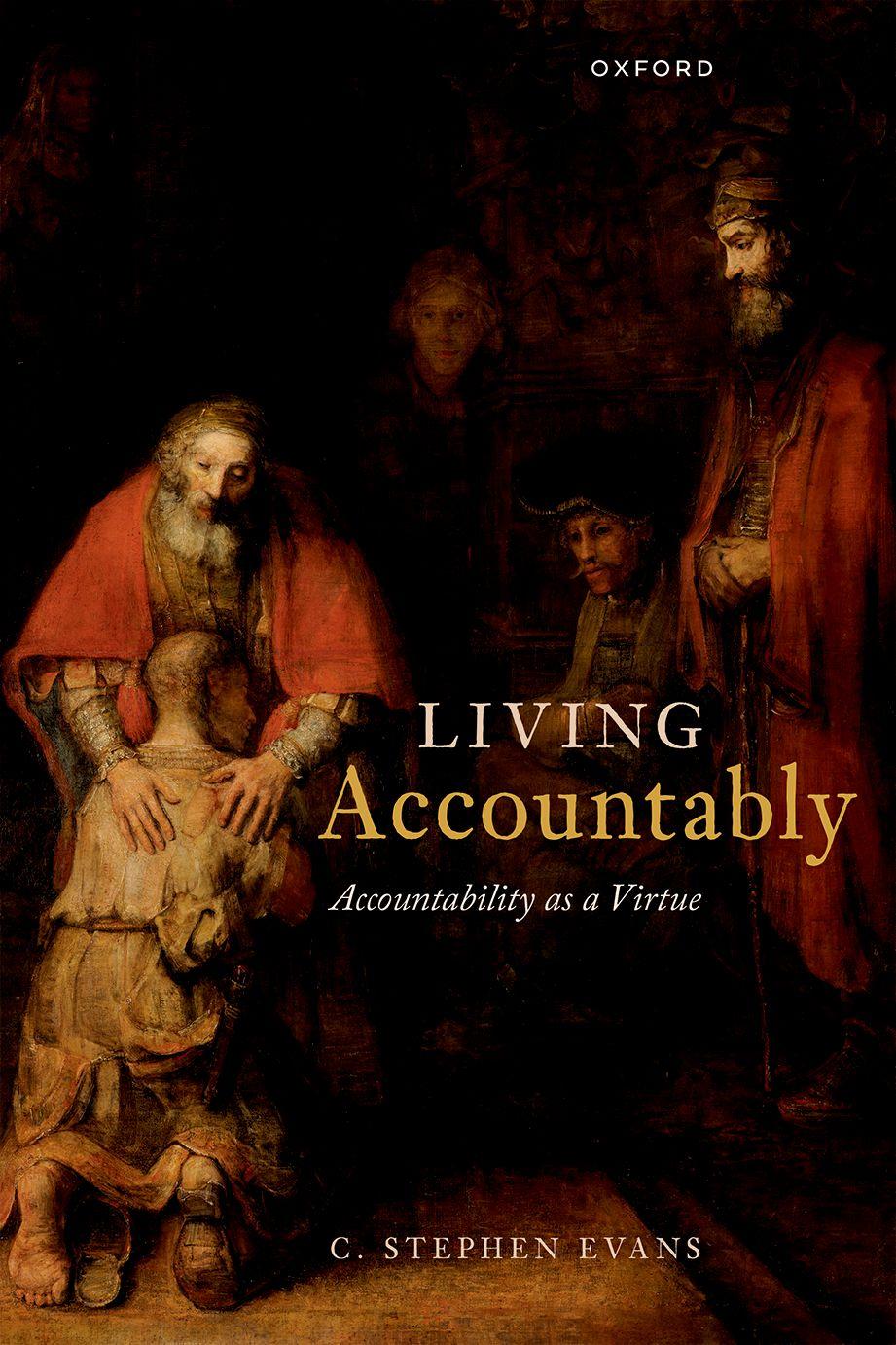

EVANS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© C. Stephen Evans 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2023

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022939915

ISBN 978–0–19–289810–4

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898104.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface and Acknowledgments

The origins of the book can be traced back to three different, seemingly disconnected happenings or elements in my personal history that occasioned some reflection. The first is that I began to notice the constant, almost ubiquitous occurrence of the word “accountability” (and its variants) in the news. Often these stories were connected to scandals of various types. I will not even bother trying to list political scandals, which seem to appear almost daily. There were a number of scandals that involved religious leaders in the USA and elsewhere, including notable figures such as Jerry Falwell, Jr., who was president of Liberty University at the time, and Ravi Zacharias, who headed up a large international ministry, RZIM, prior to his death. Another notable scandal involved physician Larry Nasser, who was team doctor for the United States gymnastics team for eighteen years, where he sexually abused hundreds of girls and young women, ultimately leading to his criminal conviction.

When these scandals were initially reported, there was an immediate outcry that the offenders needed to be held accountable, which usually meant that they needed to be punished. It occurred to me that some of these scandals might have been prevented if there had been someone holding the perpetrators accountable all along. Perhaps the misdeeds could have been detected much earlier, or perhaps the offenders would never have done some of the things they did had they known they would have to account to someone for what they were doing.

One characteristic of evildoers is that they fear transparency and want to cloak their actions in secrecy. However, virtuous people are not like this. They are people who welcome transparency and feel they do not need to hide what they are doing from others. Such people do not fear accountability; perhaps they even welcome it. We could say that they are people who strive to live accountably. They have an excellent quality (a virtue) that we could also call accountability. The need and desire to hold people accountable in a negative and punishing way points to a lack of this virtuous quality.

These reflections linked up with my own scholarly journey as a philosopher. In 2013 I had published God and Moral Obligation, a defense of the claim that moral obligations are best understood as God’s laws for humans, a traditional view that is not very popular among philosophers or intellectuals today. It struck me that the negative view our society takes of accountability as a kind of punishment might be partly why my view seemed unappealing to so many. The idea that moral obligations are grounded in God’s law implies that humans are accountable to God as the source of the law, just as citizens are accountable to human

governments for keeping human laws. It is not surprising that this picture of morality is unattractive if we think of God primarily as enforcing laws by punishing lawbreakers. No one likes being punished, and one might think that this view of morality actually destroys moral goodness by reducing morality to carrots and sticks. To see my view of morality as attractive, I needed to find a way to see being accountable to God as itself attractive. Perhaps the way to do this was to think more about this virtue I was beginning to call accountability. Under what conditions might someone see being accountable to God as a good thing?

This brings me to the third strand in the origin of this book. I realized that this welcoming of accountability to God was precisely the attitude of those devout ancient Israelites who left us the Hebrew Bible, which Christians accept as the Old Testament. Especially in the Psalms, we find poem after poem in which the authors celebrate being accountable to God, seeing God’s laws as a gracious gift that enable human freedom rather than diminish it. This in turn helped me towards a possible understanding of one of the most puzzling (to us) features of the Hebrew Bible: the insistence that “the fear of the Lord” is a virtue. In fact, it is a central virtue, the “foundation of wisdom.” Perhaps when those ancient Israelites spoke of the fear of the Lord they had something like what I was thinking of as the virtue of accountability in mind. They saw the exercise of this virtue in relation to God as supremely important.

Once these strands came together, I began to see accountability as one of a number of important virtues that have application in both the moral life and the religious life. Other virtues in this category include gratitude, which can be exercised both in relation to God and our fellow human beings, and forgivingness, a trait which we must exercise in relation to our fellow humans but is often seen as something God offers to his creatures. Perhaps the virtue of accountability, like these other relational virtues, could be studied from many different perspectives: philosophically, theologically, and empirically, as has been the case in recent decades with gratitude and forgivingness. Accountability in particular can help us to see how a healthy spiritual and religious life can connect to the moral life.

With support from the Templeton Religion Trust, I was able to assemble an interdisciplinary team to carry out research on accountability, and this book would not have been possible without the help of this team. So I must gratefully acknowledge the help of this team, who assisted me as Principal Investigator at so many points I cannot even say now which individuals may have been the source of various insights. However, I would like here to list all the members of the team, some of whom worked with me for over three years, though others joined the team for shorter periods.

Here are the names of those who helped me and their current affiliations, listed in no particular order: Charlotte Van Oyen Witvliet, Lavern and Betty DePree Van Kley Professor of Psychology, Hope College; John Peteet, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Andrew Torrance, Senior Lecturer in

Theology, University of St. Andrews, Scotland; Robert Roberts, Distinguished Professor of Ethics, Emeritus, Baylor University; Byron Johnson (Co-PI), Distinguished Professor of the Social Sciences and Director of the Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University; Sung Joon Jang, Research Professor of Criminology, Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University; Joseph Leman, Post-doctoral Fellow, Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University; Matt Bradshaw, Research Professor of Sociology, Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University; Brendan Case, Associate Director for Research, the Human Flourishing Program, Harvard University. Brandon Rickabaugh also served a crucial year as a postdoc, and now is Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Research Scholar of Public Philosophy at Palm Beach Atlantic University in Florida.

I am very grateful that the Templeton Religion Trust (TRT) was able to see the promise of this line of research and provided the financial support to allow the team to do the work. I thus gratefully acknowledge that this publication was made possible through the support of TRT grant #0171. Naturally, the views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Templeton Religion Trust.

I would also like to thank the participants in a one-week summer workshop at Calvin University in August of 2021. I will not list all the names, but I learned a great deal from our discussions. I do want to express particular thanks to Professor Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung, of Calvin University, a pre-eminent figure in virtue ethics, and to Professor Lindsey Root Luna, a psychologist from Hope College, who both participated in the whole week, offered presentations, and were a great help.

The Institute for Faith and Learning at Baylor University, directed by Darin Davis, also deserves thanks for hosting a large interdisciplinary conference on the theme of “Living Accountably,” in late October of 2021. This event served as a kind of culminating celebration for the team, and it also provided a venue for scholars from many disciplines to contribute their reflections on the virtue of accountability.

In addition to the members of my team, I would like to thank Christian Miller of Wake Forest University. Christian helped me understand the important relation between accountability and the virtue of honesty. However, he also provided some very helpful insights on how to think about and defend a “neglected virtue.” I also want to thank Michael Bailey, my Research Assistant at Baylor, who compiled the initial draft of the “Works Cited,” and Dan Kemp, who prepared the Index.

Last, but certainly not least, I must thank my beloved wife for both intellectual and emotional support through more than fifty years of marriage, but particularly for her support of this project. I simply could not have written this book without her. It is a joy to be part of a marriage in which the partners are mutually accountable. This relationship is surely one of the ways that I learned that being accountable is something to be welcomed and embraced.

1 Introduction

Accountability as a Relationship and a Virtue

Thinking of Accountability as a Virtue

Our time is one where there is much talk of accountability. When a politician provides special favors for big donors at the expense of the common good, there is a cry to hold the politician accountable. If university officials tolerate sexual harassment on the part of faculty or administrators, there is an immediate demand to hold these officials accountable. And rightly so. People should be held accountable for their behavior. When we talk about accountability in this way we are referring to a relationship in which one party is “held accountable” by another. This talk of accountability has a past temporal direction. In these contexts, holding someone accountable, especially if the relationship is hierarchical in nature, often boils down to punishing the person for misdeeds. It is therefore not surprising that the term “accountability” is sometimes viewed negatively, as something that people who are being held accountable want to avoid. Even when there is no misbehavior, most of us do not enjoy knowing that someone is looking over our shoulder, and that we will have to report to someone about our actions. To be sure this is not always the case; we may be happy to give an account to someone when we have accomplishments we are proud of and want others to know about.

Nevertheless, even if we do not always like being accountable, most of us will also admit that, in many cases, knowing we are accountable changes our behavior for the better. Even though we may not like having to report to someone, if we are honest we will admit that it is often a good thing that someone holds us accountable. Knowing that students will evaluate my classes does provide some additional motivation for me to teach as well as I can, even though I would want to teach well even if I were not evaluated in this way. Knowing that I must provide an endoftheyear report to my department chair and dean about my scholarly activity does provide some additional motivation to finish that journal article and send it off, even though I likely would want to bring my work to completion anyway. Since I know that being held accountable does provide additional motivation for doing the right thing, I have reasons to welcome being held accountable, at least under normal conditions.

Perhaps I will not welcome being accountable to someone if I believe that the person will treat me unfairly and does not really care about my good. However, if I report to a fairminded supervisor, who wants to help me succeed in the common project in which we are both engaged, it seems good that I am held accountable, and therefore it also seems right for me to welcome being held accountable.

Some people are better than others at recognizing the good of being held accountable and welcoming accountability in this way. We might say that people who are able to do this consistently, when the circumstances warrant it, are people who live accountably. The excellences displayed in this case have a forward direction. We can imagine a spectrum of different attitudes towards being held accountable. On the one end of the spectrum is the person who very much dislikes being held accountable, and therefore seeks whenever possible to avoid scrutiny by others. On the other end is the person who, while perhaps not always enjoying being held accountable, consistently recognizes its value and sincerely welcomes being held accountable, and thus lives accountably in a rich way. Perhaps most of us lie somewhere between these two poles, not really welcoming accountability, but at least grudgingly accepting it because we know it makes us better people. I suggest that those who lie at the positive end of this spectrum are displaying a virtue.

The accountability relationship involves two roles, the role of holding someone accountable and the role of being held accountable. (Although, as we shall see, there is almost always an element of mutuality in a healthy accountability relationship, so that those who are holding others responsible are in turn rightfully held responsible by those they are holding responsible.) Both roles in the relationship can be played in better or worse ways.

Most of us have some idea about what it is to be good at holding others responsible. Those who have had the experience of working for a good boss as well as one who is not so good certainly can recognize the difference between the person who characteristically holds others accountable in reasonable ways, and those who abuse their authority by making unreasonable demands or by focusing more on their own rewards and status than on the goals they should be seeking. So there are certainly excellences that can be displayed by those who hold others responsible, as well as corresponding vices.

However, there is value in looking at the excellences that can be displayed by the person who is being held accountable as well. The virtue linked to accountability probably has no generally accepted name today in our culture, but I shall call it “accountability” as well, so as to emphasize the close connection between the virtue and the relationship. It is the virtue of someone who lives accountably, who welcomes and embraces being accountable to others, and consequently displays excellence in playing the role of being an accountable person.

I will here try to give a preliminary account of this virtue, an account that is fairly abstract and will be fleshed out later. Let’s start with the role played by the

accountable person. It should be clear that the role of the accountable person is not defined solely in terms of a requirement to give an account. When an account is required, the account must deal with a set of underlying expectations or requirements. One is accountable to someone, but one is also accountable to that person for something. The virtue of an accountable person does not consist simply of providing accounts, even excellent accounts, when one is required to do so. In fact, people are often held accountable without any kind of account having been provided or even requested. One is accountable to someone when the following three conditions hold:

(1) The person to whom one is accountable (whom I shall call the accountor) has standing to expect or even require certain actions from the person who is accountable.1

(2) Included among the actions that may be required of the person who is accountable (whom I shall call the accountee) is providing an account of how well the accountable person has fulfilled those underlying requirements.

(3) The accountor has the standing to evaluate the accountee with respect to the required actions by rendering some kind of judgment, which in some cases may result in sanctions or rewards, regardless of whether this judgment is based on an explicitly given account.

Assuming that these conditions spell out the role of the accountable person, a preliminary definition of the virtue can be given: The person who has the virtue of accountability reliably plays the role of being accountable in an excellent way by being sensitive to the expectations and requirements that come with the role and conscientiously seeking to fulfill them. We could also say that the person who has the virtue of accountability knows and welcomes the fact that he or she may have to give an accounting for how those expectations have been fulfilled. It seems clear that the person who embraces or welcomes being accountable will be more likely to fulfill those expectations in an excellent way.

Obviously, having the virtue of accountability is not sufficient to guarantee that a person will fulfill the underlying expectations in an excellent way. Here is an example: Suppose that I am a poor writer, but that I somehow find myself obligated to write speeches for a politician I work for, who will evaluate me as a speechwriter. It is obvious that I may not last long in such a position because I am unlikely to write very good speeches. If I have the virtue of accountability, this means that I am more likely to produce the speeches when required, and that the

1 The language of “accountor” and “accountee” was suggested by to me by Andrew Torrance and Charlotte Van Oyen Witvliet, both members of my research team. Witvliet found the terms had already been used in the following: Harald Bergsteiner and Gayle C. Avery, “Responsibility and Accountability: Towards an Integrative Process Model,” International Business & Economics Research Journal 2, no. 2 (2003), 31–40.

speeches I do produce will probably be better than they would have been had I not conscientiously welcomed feedback from the one to whom I am accountable. Perhaps if I have a modicum of writing talent over time I may even learn to write acceptable speeches, but I may never be an excellent speechwriter if I lack the requisite writing skills and am unable to acquire them. Accountability does not guarantee good performance; it is just conducive to good performance within the limits of what is possible for an individual.

Of course it may be that not many people possess this virtue in a strong, robust sense. As already noted, many of us do not like being accountable to others, even though we know that in many cases it is for our good. However, the fact that a virtue is somewhat rare does not mean it is not a virtue. Some virtues are difficult to achieve, and the Greeks had a proverb about this: “All things noble are as difficult as they are rare.” If the virtue is rare, this may help explain why it has not been given a lot of attention in our culture. In saying that the virtue is underrecognized, I do not mean it is totally unknown. In Chapter 8 I shall show that the virtue is widely recognized in a number of fields, including the business world, even though it is not always described using the language of virtue. We shall see that this trait is sometimes recognized but called different things by different people. However, even though the virtue is sometimes recognized, it usually does not receive the attention and emphasis it deserves. Our culture is one that emphasizes holding people accountable, but it focuses mainly on accountability as punishment for bad actions.

The virtue of accountability, like other virtues, has a forward temporal direction, in that individuals who have the trait see themselves as responsible to live accountably. This virtue could also be called “responsibility,” as in “being a responsible person,” and this label might be a good term for the virtue I have in mind. However, I have chosen to call the virtue “accountability” for several reasons. First, “responsibility” (to my ear at least) could suggest simply causal responsibility, but causal responsibility and moral responsibility are distinct and do not always go together. I might be causally responsible for a car crash if my brakes fail and I hit the car in front of me, but I am not morally responsible, at least if we assume I have conscientiously maintained my car’s brakes. Second, responsibility is also sometimes understood as a purely individual property, a property that a person can exercise alone without any relation to others. A person who is deeply committed to acting on moral principles could be described as a responsible person, but the virtue I want to describe is one that, though possessed by individuals, is exercised in social relationships. If I am accountable, I must be accountable to someone.2 Nevertheless, I recognize that these arguments may not be decisive, and the virtue

2 We shall see in Chapter 7 that this claim is not a platitude, in that some thinkers maintain that one can be accountable to an ideal or principle rather than a person. However, I shall argue in that chapter that such a view faces difficulties.

could perhaps be termed “responsibleness” or “answerability.” It is not the word that is important but the concept. However, it seems best to go with a particular term for the concept and I have opted for “accountability.”

In order to understand the virtue of accountability and grasp its importance, we need to appreciate in a rich way the social character of human persons. We need to see that it is a good thing to be held accountable by others, at least when certain conditions are met, and we need to strive to become the kinds of people who want to be accountable. In this book I will try to make it clear when I am referring to the condition or relation of being accountable and when I am speaking about the virtue. Obviously, the two are related, since it is only when one is in a relation of accountability that one will have an opportunity to exercise the virtue. Some may worry about whether accountability in some way is in tension with autonomy, usually regarded as an important moral quality. I shall argue at several points in this book that this is not the case, and that accountability and autonomy, at least the kind of autonomy worth having, are complementary qualities.

Relational Virtues

I believe that the virtue of accountability is one of a number of virtues that have this feature: while possessed by individuals they can only be exercised in characteristic relationships. These virtues could be called relational or social virtues. Think for example of gratitude. Most people agree that we should be grateful when someone does something nice for us, for example, by providing us with a gift of some sort. Some people are much more apt to appreciate the gifts and generosity of others; they have the virtue of gratitude. This virtue has been studied extensively by psychologists and it has turned out to have amazing power to benefit the life of a grateful person.3

There is another human relationship which is closely linked to a muchneeded virtue; the relationship is one in which forgiveness is needed. The need for forgiveness is pervasive in human life. In marriages, friendships, and even business relationships, people often see that it is good to forgive others who have wronged them. This is so for a number of reasons, including preventing the destruction of valuable relationships.

3 The leading expert on the scientific study of gratitude is Robert A. Emmons, the founding editor of The Journal of Positive Psychology. For a good introduction to his work that is accessible to nonpsychologists, see his Thanks: How Practicing Gratitude Can Make You Happier (New York: HoughtonMifflin, 2008). Some of the benefits of gratitude are quite surprising. In a study students randomly assigned to do a “gratitude journal” not only were happier but exercised more and slept better than a control group.

Humans who live together sometimes hurt one another in various ways, sometimes intentionally, sometimes unintentionally. When we are harmed by someone, it is natural to feel resentment, perhaps even to desire revenge or retribution on the offender. Such situations can lead to cycles in which the revenge taken against the offender leads to a sense of being wronged in the original wrongdoer, leading to more cycles of resentment and perhaps more retaliation. The best way to end such destructive cycles and allow humans to live together with a modicum of peace is for people to forgive each other. Yet forgiveness is often very difficult, and some people seem to be much better at forgiving than others. Those who can do so have a virtue, one that is sometimes called “forgivingness,” or just forgiveness. Once more this virtue has been studied extensively by psychologists, and it has been shown to have profound beneficial effects, not just for the person forgiven but for the one who forgives as well.4

I believe that what I am calling the virtue of accountability is a similar relational virtue that deserves to be studied, both because it is good in itself, but also to see if it will have a positive impact on human life. This virtue has at least one other similarity to the virtues of gratitude and forgiveness: all three of them have applications to the religious life as well as ethical life. Religious people from the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), as well as many from other faiths, usually think that it is important to have the virtue of gratitude, which can and should be directed both to human benefactors and to God, who is, from the perspective of the Abrahamic faiths, the source of all goods. Similarly, religious people from those faiths typically see forgiveness not only as something that needs to be exercised in human relations but as something to be sought from God and accepted from God.

The virtue of accountability is also one that is relevant both to the ethical life and the religious life. It is obvious that humans are accountable to each other in all kinds of ways and in many different contexts. People who have faith in a God typically believe that there is also at least one relationship of accountability that holds for everyone all the time. It is fundamental to the Abrahamic faiths to see human beings as accountable to God for their whole lives, in addition to being accountable at various times to their fellow human persons. I shall call the condition in which people are accountable for their lives as a whole “global account ability.” The condition of being accountable to God (or some other transcendent reality) I shall call “transcendent accountability.” Adherents of the Abrahamic faiths typically believe in both global accountability and transcendent account ability. They believe they are accountable for the whole of

4 Perhaps the main pioneer in the scientific study of forgiveness is Everett L. Worthington, Jr. Worthington has published many articles and books; a good starting place to understand his work is his Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2006). Just as is the case for gratitude, the case for the benefits of being a forgiving person are surprising and extend to physical as well as mental health.

their lives and account able to God. Christians, for example, typically believe in a last judgment, where all will be asked to account to God for their lives as a whole. Christians believe that all humans live their lives coram Deo (before God) and that we are accountable to God both during our lives and in eternity. However, though global and transcendent accountability often go together, it is conceivable that they might be distinguishable. One can imagine being accountable to God for only part of one’s life, and one can imagine being accountable for the whole of one’s life but not to God.5

This is not merely a logical possibility. The sense of being accountable for the whole of life is not limited to religious believers. There are some people, whom I shall discuss in detail in Chapter 6, who do not believe in God, but who seem to have a similar belief that they are accountable for their lives as a whole and thus believe in global accountability. Some of these people understand global accountability as directed to some transcendent reality other than God, but this is not always the case. There are those who think they are accountable for their lives as a whole but accountable only to themselves and/or other humans.

I shall argue that at least the Abrahamic faiths understand the embrace of global accountability as a particularly important virtue. In Chapter 4 I will suggest that this virtue is similar to the biblical concept of the “fear of the Lord,” which plays a prominent role in the Hebrew Bible, a virtue trait that is there praised as “the beginning of wisdom.” In Chapters 6 and 7 I will provide discussions and evaluations of various ways global accountability might be understood. I have already distinguished between the relation of accountability, including the situation in which a person is held accountable, and the virtue of accountability. I now want to distinguish yet another related concept, one that will figure strongly in Chapters 6 and 7: the sense of accountability. By “sense of accountability” I mean a kind of recognition of oneself as accountable, a recognition that often comes through an experience. The sense of accountability is most clear in people who see themselves as accountable in the global sense, accountable for their lives as a whole.

Types of Accountability Relationships

In addition to the kind of global accountability that many believe attaches to a person’s life as a whole, it is obvious that there are many particular relations of accountability humans have to other human persons, and all such relations would seem to provide occasions for the exercise of the virtue of accountability. Those who reject the idea of global accountability, and think we are only accountable to

5 These possibilities will be explored in Chapters 6 and 7.

other humans, do not lack for occasions to exercise the virtue of accountability. As I said above, to be in a relation of accountability someone must have the proper standing to expect or require things from us, including requiring an account as to how we have satisfied these expectations. Many such relations are hierarchical in nature. Children are accountable to parents. Students are accountable to professors. Professors are accountable to department chairs, deans, provosts, and presidents.

However, it is vital to recognize that not all accountability relations are hierarchical in nature, and even those that are normally involve a kind of mutuality. There is also accountability to those who are peers and to those who are subordinates. Friends may promise to hold each other accountable, as do participants in “12step” programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Professors are accountable in some ways to their students, as well as to their colleagues. Business executives are accountable to their employees in some ways. This kind of accountability is of course somewhat different from accountability to superiors. My students have a right to ask me why I give the kinds of assignments I give, but not the right to order me to test them in a particular way. Still, they have what a law court might describe as the proper standing to ask me for an account, and I have a responsibility to listen to them and respond.

Accountability relationships thus do not have to be “upward” in character (exercised in relation to a superior), but they can be “downward” (exercised in relation to a subordinate) as well as “horizontal.” This horizontal character is usually present when the relations are voluntary in character. For example, mutual accountability would seem to be an ingredient in a healthy egalitarian marriage.

Philosopher Stephen Darwall has argued that accountability is part of a family of “secondpersonal” concepts that are central to the moral life as a whole.6 On his view, which I will discuss in some detail later, both in Chapter 2 and in Chapter 6, accountability is central to defining what we might call the human moral community. If Darwall is right, or even partly right, there may be a sense in which all humans may be thought to be accountable to all other humans insofar as those other humans are part of and can represent “the moral community.” If that is the case, then in addition to the accountability that is linked to the specific roles we occupy in relation to each other, there is a kind of accountability that humans owe to each other simply as humans.

As I have already said, what is common to all these kinds of accountability is the notion of someone having “standing” or a “right” to expect some things from someone else, including the right to ask for an “account” from the person being held accountable, where this accounting ranges over the underlying legitimate expectations or requirements. It is crucial to recognize that this concept of

6 See Stephen Darwall, The Second-Person Standpoint: Morality, Respect, and Accountability (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006), particularly Part II.

standing is itself a normative or moral one.7 One does not acquire such standing simply by force. In hierarchical accountability relations, and perhaps in others as well, the person who receives the accounting (the accountor) often expresses a judgment that can involve sanctions or even punishment towards the one giving the account (the accountee). However, this fact should not obscure the essentially normative character of the status the accountor must have. I am not properly accountable to a bully. No one acquires the requisite moral standing to hold someone accountable solely by threats backed up by the power to harm. Of course I may indeed, on grounds of prudence, try to satisfy a bully or someone who is blackmailing me, but the fact that I might in some cases acquiesce to the requests of such a person does not legitimize the demands of the bully or the blackmailer. This point is so important I will provide a more extended discussion of it in Chapter 3, which provides a more finegrained account of the virtue of accountability. In the concluding chapter I shall argue that the virtue of accountability is quite distinct from the practice of punishment.

If we suppose that there is a God, what would be the relation between accountability to God and accountability to our fellow humans? Of course, adherents of different theistic religions might answer this question somewhat differently, but I think there will be some fundamental similarities in the answers believers in God will provide. Most would agree that it is not the case that accountability to God replaces or supplants human accountability relationships. Being accountable to God hardly means that a person is freed from being accountable to other humans, whether they be superiors or peers or those whom they direct or supervise.

In the case of Christian faith, I think the relation between accountability to humans and accountability to God is somewhat paradoxical. I say this because accountability to God, if there is a God to whom we must answer, is a relation that both makes human accountability relations less than ultimate and yet at the same time deepens these human accountability relations. On the one hand, accountability to God must take priority over all other accountability relationships. The first disciples of Jesus, Peter and the other apostles, when commanded by human authorities to act against their conscience, are reported to have said we “must obey God rather than humans” (Acts 5:29). Similarly, Socrates, when on trial for his life in Athens, tells the court that if they offer to acquit him of the charge if he agrees to stop philosophizing, he must refuse the offer. Socrates says he has been ordered by “the God” to do his philosophical work, and he must “obey the God” rather than the orders of the people of Athens.8 Thus, those who believe we are accountable to God see their obligations to other humans as ones that, however

7 For an excellent analysis of this moral sense of standing, see James Edwards, “Standing to Hold Responsible,” Journal of Moral Philosophy 16 (2019), 437–62.

8 Plato, Apology 29, c–d. Translation by Hugh Tredennick, found in Plato: The Collected Dialogues, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), 15.

important, cannot have ultimate and absolute significance. Christians (and presumably other theists) should say that we dare not obey a human authority if it means disobeying our Creator.

However, at the same time that it relativizes human accountability, accountability to God also deepens those forms of human accountability. The reason for this is that we must see the situations in which we have been placed in the light of God’s providential ordering of our lives. The New Testament provides another excellent illustration of this. In 1 Peter 2:13 we are told to “submit . . . for the Lord’s sake to every authority instituted among men . . .” Obviously, in light of the passage in Acts, this submission is not absolute for Christians. But it does mean that for the Christian believer (and something similar will be the case for Jews and Muslims) there is an additional weight and seriousness present even in human accountability relations. When such believers obey an earthly authority, it is not merely fear of human sanctions that motivates them. There may be many reasons to obey a human authority, but the fact that we are ultimately accountable to God even for the ways in which we live out our accountability to each other provides another significant reason to honor human authorities for those who think of themselves as accountable to God.

Philosophizing About Virtues

Before embarking on a more detailed investigation of the virtue of accountability, I want to conclude this introductory chapter with some general thoughts about the variety of ways philosophers have approached the topic of virtue. In both ancient and medieval western philosophy, philosophical thinking about ethics was largely focused on the virtues. However, for reasons that I believe are still not fully understood, in modern philosophy, from the eighteenth century until late in the twentieth century, this focus on the virtues gradually diminished. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (at least up until the last few decades of the twentieth century), philosophical debates in ethics revolved almost exclusively around questions about actions. The focus was not primarily on the character of agents, but on what agents were allowed to do, or required to do, or prohibited from doing.

Kantians, for example, argued that there was a supreme principle of morality, the categorical imperative, from which humans could derive moral principles of action that held universally. Utilitarians, following Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, argued that the supreme principle of morality was the “principle of utility,” which measures moral actions solely by the consequences or results of actions. Both seemed to see the goal of ethics as establishing some supreme, overarching principle which would be the foundation of ethics. Those philosophers known as “ethical intuitionists,” such as W. D. Ross, differed somewhat, in that they argued that there were a number of different principles that govern the moral

character of human actions, and they focused, as the name implies, on an epistemological view that moral knowledge is at least partly immediate in character. Still their focus was also on actions. The character of the agent was seen as “virtuous” if the agent properly followed the principle or principles that determine what was moral. However, though there was talk of “virtue,” little attention was paid to concrete virtues, such as wisdom, courage, and temperance.

Beginning in the last few decades of the twentieth century this situation changed. Under the influence of such thinkers as Elizabeth Anscombe, Phillipa Foot, and Alasdair MacIntyre, philosophers rediscovered the virtues, and today the discussion of virtues is clearly part of the mainstream. There are, however, many different projects that are going on. So before embarking on the task of explaining and defending the virtue of accountability, I need to say something about my own view of the virtues, an understanding that will provide context for the project.

Many ethics textbooks present “virtue ethics” as a type of ethical theory, which is to be contrasted with “deontological” and “consequentialist” theories, which were regarded as the main contenders prior to the emergence of virtue ethics, understood in this sense as a rival ethical theory. The deontological type of theory makes the concept of duty or obligation central to ethics, and it is prominently represented by followers of Immanuel Kant. Kant, as was just noted, tried to ground all of ethics in one supreme principle, the “Categorical Imperative,” which was supposed to provide a test to determine what principles of duty should be followed. Consequentialist theories, in contrast, make the idea of maximizing value central to the ethical life, and are classically represented by such utilitarians as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who tried to ground the whole of the moral life in the “principle of utility,” which says one should always act so as to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Classical utilitarians understood the good as pleasure and the absence of pain, though many contemporary consequentialists have different views on what is the good to be maximized. When virtue ethics is contrasted with these types of ethical theories, which try to ground all of ethics in one concept or one supreme principle, it tends to take on a similar reductionist character, attempting to ground all of ethics in virtue concepts, sometimes called “aretaic concepts,” from the Greek word for virtue (arete). Thus, Michael Slote characterizes a virtue ethic as one that is “agentbased” and says that such a view “treats the moral or ethical status of acts as entirely derivative from independent and fundamental aretaic (as opposed to deontic) ethical characterization of motives, character traits, or individuals .”9 Christine Swanton defends what she calls a “pluralistic view” of virtue ethics, and thus provides a less reductive and monolithic characterization than Slote, but she still affirms that a

9 Michael Slote, Morals from Motives (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 5.

recognizable “virtue ethic” will be one that claims that “the notion of virtue is central in the sense that conceptions of rightness, conceptions of the good life, conceptions of the ‘moral point view’ and the appropriate demandingness of morality, cannot be understood without a conception of relevant virtues.”10

This book does not assume anything like such a “virtue ethic” in this sense. My approach is pluralistic in a stronger sense than Swanton’s. I believe that the concepts of value, duty, and virtue are all fundamental to ethics. Although these concepts are clearly interconnected in various ways, I see no reason to believe that any of the members of this set of concepts can be reduced to or grounded in any others of the members of the set. I thus agree with the wellknown claim of Bernard Williams that we have reason to think that ethical truth is complicated and messy, not able to be captured in a simple theory:

If there is such a thing as the truth about the subject matter of ethics—the truth, we might say, about the ethical—why is there any expectation that it should be simple? In particular, why should be it be conceptually simple, using only one or two ethical concepts, such as duty or good state of affairs, rather than many?11

The present book is therefore not an example of “virtue ethics,” in this sense of trying to make virtues central to the whole of ethics. It is rather an exploration of a particular virtue, the one I am calling accountability. As such it must assume some view of what virtues are, how they are recognized, and how they are developed. One could hardly build a case for accountability as a virtue without having some understanding of what a virtue is. But this kind of concrete exploration of a particular virtue does not require any commitment to a “virtue ethic” in the sense of a reductive theory that attempts to make the virtues foundational to the whole of ethics.

Julia Driver has offered a distinction between what she terms “virtue ethics” and “virtue theory.”12 Virtue ethics is understood as in my last two paragraphs, a distinctive approach to ethics that is a rival to deontological and consequential approaches. However, a virtue theory would just be an account of the virtues, and such an account can be and has been given by Kantians and utilitarians, and not just virtue ethicists. In some sense, what I will be offering presupposes what could be called a virtue theory in Driver’s sense, but even this is somewhat misleading. First, the focus will not be on virtues in general but on one particular virtue. Second, though I will certainly assume or defend certain views about

10 Christine Swanton, Virtue Ethics: A Pluralistic View (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 5.

11 Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy (London: Fontana/Collins, 1985), 17. To be fair to Christine Swanton, she also affirms what Williams says, and she tries to develop a form of virtue ethics that, while making virtue concepts central, sees those concepts as complicated.

12 See Julia Driver, “The Virtues and Human Nature,” in Roger Crisp (ed.), How Should One Live? Essays on the Virtues (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 111–29.

virtues, I shall strive to provide an understanding of accountability as a virtue which is consistent with a variety of views about the virtues. This project is therefore better described as a contribution to what Robert Adams has called “the ethics of virtue” than “virtue ethics.”13

Of course as philosophy this undertaking aims at understanding and it is an intellectual endeavor. However, my ultimate aim in trying to understand accountability as a virtue is the kind of aim found in such classical ethical thinkers as Plato and Aristotle, who believed that philosophy, as the love of wisdom, should contribute to human flourishing. Gaining a better understanding of accountability is something that should help us become wiser and live better lives, even if the wisdom and health it provides is partly the Socratic wisdom of recognizing how far from being wise we are.14 If it does not help us in this way, then the understanding has little value.

What is a Virtue?

A virtue is an excellence, and in previous times it was common to speak of virtues of all sorts that belonged to all kinds of things. A knife that can be sharpened and holds its sharp edge well has the virtue of sharpness, and in the ancient world a person with good eyesight was thought to have a virtue, the “ocular virtue.” However, the term has come to mean excellences that belong distinctively to humans, and among those human excellences, it has come to refer particularly to excellences that have a moral character or at least a moral dimension. (This may be changing, since recently there has been a great deal of work on intellectual virtues.)

The excellences in view are in some sense character traits; that is, they are not simply actions and certainly not just things that happen to a person. One does not describe a person as having the virtue of honesty because the person told the truth on one occasion. Nor does one acquire a virtue in the way one might “catch” an illness such as the flu. There is much disagreement about both the scope and the duration of such traits, as well as about how common the possession of such traits is.15 However, whether virtues are seen as global in scope and

13 See Robert Adams, A Theory of Virtue: Excellence in Being for the Good (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 6.

14 For a vigorous defense of thinking about the virtues as a way of enhancing human life, along with some pointed criticisms of the mindset that seeks monolithic theories, see Robert Roberts, “Varieties of Virtue Ethics,” in James Arthur, David Carr, and Kristin Kritjansson (eds.), Varieties of Virtue Ethics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 17–34.

15 The socalled “situationist” critique of virtue ethics holds that robust virtues are almost nonexistent. For a good statement of this criticism see John M. Doris, “Persons, Situations, and Virtue Ethics,” Nous 32, no. 4 (1998), 504–30. For a discussion of replies see Robert Adams, A Theory of Virtue: Excellence in Being for the Good (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 115–43, and Christian Miller, “Social Psychology and Virtue Ethics,” Journal of Ethics 7 (2003), 367–95.

long in duration, or more specific and modular in scope and perhaps more unstable in duration, they must have some degree of scope and some degree of stability over time to count as virtues.

I am attracted to Robert Adams’s definition of a virtue: a “persisting excellence in being for the good.”16 This definition is obviously highly abstract and therefore somewhat vague; there are likely many different forms of the good, and also many different ways of being “for” the good. Nor does Adams say how long a virtue trait must persist to be a genuine virtue. However, just because the definition is abstract, it may capture many different forms of moral excellence.

Many philosophers writing about the virtues are Aristotelians, and many of them follow Aristotle in seeing virtues as traits that are conducive to human flourishing, happiness, or eudaimonia. Aristotelian accounts of the virtues often connect human flourishing to an account of human nature. To understand what it is for a thing to flourish, it seems natural to think that one must pay attention to what kind of a thing we are asking about. After all, the virtues of a knife are linked to the knife’s nature and purpose. If we know what a knife is for, then we probably know what it is to be a good knife. Similarly, perhaps if we know something about human nature we can say something about what it is to be a good human. This seems plausible if we can agree on the basics of human nature, and especially if we see human nature as having some kind of purpose or telos. The Aristotelian view of the virtues seems to have more content than Adams. However, perhaps we can see Aristotelian virtues as fitting the Adams definition as well. If virtues are qualities that help humans to achieve the good for humans, these Aristotelian excellences would also be ways of being for the good, and thus would count as a species of virtue in the Adams sense.

I doubt that all virtues can be understood as Aristotelian, even if the Aristotelian ones are an important kind of virtue. It is not obvious that all forms of human excellence, even moral excellence, are good only because they lead to human flourishing or happiness. Some human excellences may be good in themselves, not just good because of their function in fostering happiness or some other human goal. It may also be excellent to be for the good even when the good is not merely human good. The Adams definition leaves open this possibility, which is important, since one of the questions about the good we may want to ask is whether there are goods that are absolute or categorical in nature. That is, we may want to know whether it is good (categorically) that there are human beings that are good as humans. The goods we want to be for may include goods that are unconditionally good, not just things that are “good of their kind” or “good for their kind.”

16 Adams, A Theory of Virtue, p. 11. In the context it is clear that Adams is assuming that these will be traits of character of persons.

In any case it is not hard to provide more of a story about virtues that will make the Adams account more concrete, by supplying accounts of the good and what it means to be for the good. Christine Swanton’s “pluralistic” account of the virtues is helpful here. Like Adams, she provides an account of the virtues that does not require them to fit the Aristotelian model. Like Adams, she provides an account of the virtues that sees them as oriented to the good, with the goods connected to a particular virtue seen as linked to a “field” or domain linked to that virtue. Thus, a virtue is “a disposition to respond to or acknowledge, in an excellent (or good enough) way, to items in the field of a virtue.”17 Swanton then goes on to show how this leads to a plurality of virtues, since there will be not only different fields for virtues, but different modes or forms of response to those items in the fields, different forms of goodness in those items, and different ways in which those responses can be seen as both good and/or right.18 I shall follow Adams and Swanton in my account of the virtue of accountability, arguing that this virtue is both excellent in itself but also seems likely to contribute to human flourishing in a number of ways.

A Sketch of the Road Ahead

A brief road map of what is to follow may be helpful for the reader. In Chapter 2 I will give some arguments for the reality and importance of accountability as a virtue, defending the view that it plays a large role in the moral life as a whole, and thus that its importance is not limited to its role in hierarchical accountability relations. In Chapter 3 I will try to become clearer about the nature of this virtue, and also describe how it is manifested in human life. In Chapter 4 I will look in a brief way at the history of the concept, so as to understand how it has been perceived in other times and in other cultures, as well as how it continues to be recognized and described today. This will give us deeper insight into the virtue and perhaps help us understand why it seems to have been somewhat eclipsed in contemporary western cultures. In Chapter 5 I will examine the relation between the virtue of accountability and a number of other virtues, such as honesty, gratitude, and humility, and also look at vices that are opposed to the virtue. In Chapter 6 I will begin to examine global accountability, that is, accountability for our lives as a whole. What forms can the virtue of accountability take when it is exercised in this global way? Chapter 6 will look closely at what I call secular accountability, which attempts to make sense of global accountability without appeal to God or any transcendent reality. In Chapter 7 I will then look at views of global account ability

17 Swanton, Virtue Ethics, p. 1. 18 Swanton, Virtue Ethics, pp. 1–2.

that are robustly metaphysical: theistic accountability, karmic account ability, and what I will call ideal accountability. Collectively, I term these forms of transcendent accountability. In Chapter 8 I will try to show the importance of accountability for actual human life. I will discuss empirical evidence for the existence of the virtue, both the evidence already available from various arenas of human life and research that has recently been done or is in process. It is import ant to determine what evidence we have as to how the presence of the virtue of accountability might make a difference to human existence. In the concluding chapter I will try to summarize what has been accomplished in the book as a whole. I will also say a little about how the virtue could be developed. In the last part of the conclusion I will argue that recognizing the virtue of accountability could make a profound difference to human life in a number of areas. I will take as a prime example our system of criminal justice. In the USA this system is in crisis, and the virtue of accountability could play a key role both in developing alternatives to incarceration and in making our prisons more humane and more effective at helping offenders change their lives.