Acknowledgments

Formeatleast,philosophicalworkisalwaysacollaborativeprocess,andthereis verylittleinthepagesthatfollowthatIhavenotlearnedfromsomeoneelse indeed,moreoftenthannot,from many others many timesover.Theideasthat followweredevelopedoveryearsofconversationwithfriendsandcolleagues,and Iregard(atleastthegoodpartsof)whatfollowstobeasmuchtheirworkasitis mine.Atthesametime,Iknowfrom repeated experiencethatmymemoryforthe sourcesandinspirationsofmyideasisoften veryimperfect.Soletmebeginby apologizingtothoseIhaveforgottenandbyacknowledgingthatmydebtsinthis regardalmostcertainlyfaroutstriptheacknowledgmentshereandinwhat follows.

Suchremarkswouldbeaptwithrespecttoanyofmyphilosophicalwork.But theyareespeciallytrueheresincetheseareideasthat,insomesense,I’vebeen thinkingaboutalmostsinceIbegantostudyphilosophy.Indeed,elementsofwhat followsaredescendedinsomesensefromtheBAthesisonKantandHegelIwrote attheUniversityofChicagounderthedirectionofMichaelForster.Afterleaving Chicago,IspentayearinBerlinonaFulbrightFellowshipworkingonGerman philosophywithRolf-PeterHorstmannandDinaEmundts.AfterBerlin, IreturnedtotheUStodoaPhDatNYUunderthedirectionofThomasNagel, BéatriceLonguenesse,DonGarrett,andDavidVelleman(aswellasSharonStreet andDerekParfit).AlthoughmyofficialPhDprojectwasoncontemporarymoral psychology,inthoseyears,IwasalsoalreadyworkingonthereadingofKantthat follows,andmyworkhereisdeeplyinfluencedbyallofthem,andespeciallyby BéatriceandTom.Indeed,whatfollowsmightbeviewedasmyattempttothink throughsomebasiccommitmentsinthelatter’sphilosophyusingtheframework forthinkingaboutKantthattheformer’sworkprovides.

AversionofChapter6servedasmyjobtalkatmanyinstitutions including Pittsburgh,whereIwasluckyenoughtojointhefacultyuponcompletionofmy PhD.There,Iwasexposedtoanextremelystimulatingenvironmentforthinking aboutthecontinuingrelevanceofKant’sphilosophy,somuchsothatImightbe reasonablyregardedasafellowtravelerofthe “Pittsburghschool.” Afterleaving Pittsburgh,IthenspentaveryhappysixyearsasaprofessoratUCIrvine,where myworkonthisprojectbeganinearnest,beforeleavingforTexaslastyear.Allof theseinstitutionshavemythanksfortheirsupportduringthedevelopmentofthis project,asdoesthePrincetonUniversityCenterforHumanValues,whereIalso spentanextremelyproductiveyearearlyoninthisprocess.

ThelargestinfluenceonthisprojecthassurelybeenthegroupofotherKant scholarsandphilosophersinconversationwithwhomIdevelopedtheseideas. MostnotableinthisrespectissurelyNicholasStang,whoseinfluenceonwhat followscanhardlybeoverstated.Butmuchoftheworkthatfollowsisdeeply influencedbyfeedbackI’vereceivedfromothermembersofthisgroup. HereIwouldsingleoutforspecialacknowledgment atleast thefollowing(in alphabeticalorder):LucyAllais,RosalindChaplin,AndrewChignell,Steve Engstrom,StefanieGrüne,MatthiasHaase,DaiHeide,AaronJames,JimKreines, KathrynLindeman,BarryMaguire,ColinMarshall,SamanthaMathrene,Colin McLear,MelissaMerritt,SashaNewton,TykeNunez,AndrewsReath,Tobias Rosefeldt,TimRosenkoetter,KieranSetiya,HoustonSmit,AndrewStephenson, SergioTenenbaum,ClintonTolley,EricWatkins,andJackWoods.

Butalongtheway,myworkonthesetopicshasalsobenefitedgreatlyfrom many,manyothers,including atleast thefollowing:UygarAbaci,AlpAker,Karl Ameriks,FatmeaAmijee,CarolineArruda,YuvalAvnur,RalfBader,Carla Bagnoli,DavidBarnett,IanBelcher,JohnBengson,SvenBernecker,Selim Berker,ChrisBenzenberg,SimonBlackburn,JochenBojanowski,BobBrandom, ClaudiBrink,MattBoyle,AngelaBreitenbach,SarahBuss,JustinClarke-Doane, AlixCohen,AnnalisaColiva,JimConant,JonathanDancy,StephenDarwall, JanelleDeWitt,CatharineDiehl,SinanDogramaci,DanielaDover,CaseyDoyle, JuliaDriver,MaxEdwards,SonnyElizondo,DavidEnoch,PatricioFernandez, LucaFerraro,JeremeyFix,AntonFord,ChristopherFrey,JenniferFrey,Michael Friedman,PatrickFrierson,KimFrost,MarkusGabriel,AaronGarrett,Gabriele Gava,SamuelGavin,AllanGibbard,MargaretGilbert,LauraGillespie,Jonathan Gingerich,HannahGinsborg,WolframGobusch,ChuckGoldhaber,AnilGomes, SeanGreenberg,AlexGregory,AlexGuerrero,PaulGuyer,AdrianHaddock,Reza Hadisi,GaryHat field,JeremyHeis,JeffHelmreich,BorisHennig,TimHenning, AllisonHills,AlexHinshelwood,UlfHlobil,ThomasHoffman,DesHogan,Ulf Hölbel,DavidHorst,ThomasHurka,DavidHunter,PaulHurley,Alexander Jackson,AnjaJauerning,KarenJones,PatrickKain,PaulKatsafanas,Antti Kauppinen,AndreaKern,ThomasKhurana,IradKimhi,SariKisilevsky, PatriciaKitcher,FranzKnappik,KarenKoch,ChristineMarionKorsgaard, MathisKoschel,RobbieKubala,DougLavin,ThomasLand,DavidLandy, AndreLebrun,BenLennertz,JessicaLeech,JedLewinsohn,ElizaLittle,Errol Lord,RudolfMakkreel,Anna-SaraMalmgren,SusanneMantel,EricMarcus,Julia Markovits,BerislavMarušić,MichelaMassimi,ErasmusMayr,JohnMcDowell, JakeMcNulty,TristramMcPherson,MichaelaMcSweeney,NeilMehta,James Messina,EliotMichaelson,JoeMilburn,JohnMorrison,BeauMadisonMount, EvgeniaMylonaki,MichaelNelson,RamNeta,KarinNisenbaum,Rory O’Connell.DawaOmetto,OnoraO’Neill,LaraOstaric,MichaelOtsuka,Hille Paakkunainen,JapaPallikkathayil,SarahPaul,CarlottaPavese,Christopher Peacocke,DavidPlunkett,DuncanPritchard,IanProops,HsuehQu,Peter

Railton,MichaelRescorla,MikeRidge,NickRiggle,ArthurRipstein,Sebastian Rödl,MichaelRohlf,ConnieRosati,WendySalkin,JackSamuel,JoeSaunders, DavidSaurez,GeoffSayre-McCord,TimScanlon,TamarSchapiro,Mark Schroeder,FrancoisSchroeter,LauraSchroeter,JeffSebo,JanumSethi,Lisa Shabel,JamesShaw,MatthewSilverstein,DanielJ.Singer,NeilSinhababu. JamsheedSiyar,WillSmall,MatthewSmith,MichaelSmith,DeclanSmithies, CurtisSommerlatte,DavidSosa,RobertSteel,MartinSticker,MyriamStihl, ThomasSturm,DanielSutherland,SigrúnSvavarsdóttir,KurtSylvan,Kathryn Tabb,LarryTemkin,PeterThielke,MichaelThompson,EvanTiffany,Markus Valaris,MarkvanRoojen,KennyWalden,AnikWaldow,R.JayWallace,Owen Ware,DanielWarren,SebastianWatzl,WayneWaxman,JonathanWay,Ralph Wedgwood,PeterWiersbinski,EricWiland,MarcusWillaschek,VanessaWills, DanielWodak,AllenWood,MelissaZinkin,andArielZylberman.

Thisworkhasalsobenefitedgreatlyfromtwomanuscriptworkshopsonitat UCSDandToronto,organizedbyEricWatkinsandNicholasStang,respectively.I alsoreceivedagreatdealofincrediblyinsightfulfeedbackonthismaterialfrom theparticipantsinthe10.KantKursinBerlin,convenedbyTobiasRosefeldt, althoughunfortunatelythattookplacetoolateformetotakefulladvantageof thatfeedbackhere.ThanksarealsoduetoaudiencesatSimonFraserUniversity, NewYorkUniversity,UniversityofPennsylvania,HarvardUniversity,Boston University,HumboldtUniversitätzuBerlin,UniversityofMiami,Universityof Wisconsin,ImmanuelKantBalticFederalUniversity,SouthamptonUniversity, UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego,UniversityofCalifornia,Irvine,NewYork University:AbuDhabi,UniversityofToronto,NationalUniversityofSingapore, ErlangenUniversität,UniversitätLeipzig,IowaStateUniversity,Potsdam Universität,OxfordUniversity,UniversityofEdinburgh,St.Andrews University,UniversityofMichigan,UniversityofPittsburgh,andCambridge University.Ialsoreceivedhelpfulfeedbackonrelatedworkatthesummerschool inGermanphilosophyatBonn,theNAKSPacificStudyGroup,theEastern, Central,andPacificAPA,theConferenceonUnityinGermanPhilosophyin MainzandCologne,theonlineworkshoponKant’sfundamentalassumptions,an onlineconferenceonepistemicautonomyhostedbySashaMudd,theCalifornia PhilosophyWorkshop,theConferenceonAgencyandRationalityatUniversityof Campinas(Brazil),theMidsummerPhilosophyWorkshopatCambridge University,theConferenceonConstruction,Constitution,andNormativityin Berlin,theWorkshoponEthicsandPracticalReasoningatDartmouthUniversity, andSPAWN(NormativeRealism)atSyracuseUniversity.

PartsofwhatfollowswasdevelopedwiththesupportofaCharlesA.Ryskamp ResearchFellowshipfromtheACLS/MellonFoundation,anAlexandervon HumboldtResearchFellowship,andaLawrenceS.RockefellerFaculty FellowshipatthePrincetonUniversityCenterforHumanValues,aswellasthe institutionsabove.

SpecialthanksareduetoMaxEdwards,whosewonderfulcopy-editingand incisivephilosophicalcommentshavemadewhatfollowsmuchlesspainfulto readthanitwouldotherwisebe.ManythanksalsotoPeterMomtchiloffforhis consistentsupportandsureandexperiencededitorshipofthisproject,andto HenryClarkeforhishardworkasproductioneditorThanksaswelltoDolarine SoniaFoncecafordirectingthecopy-editingprocess.

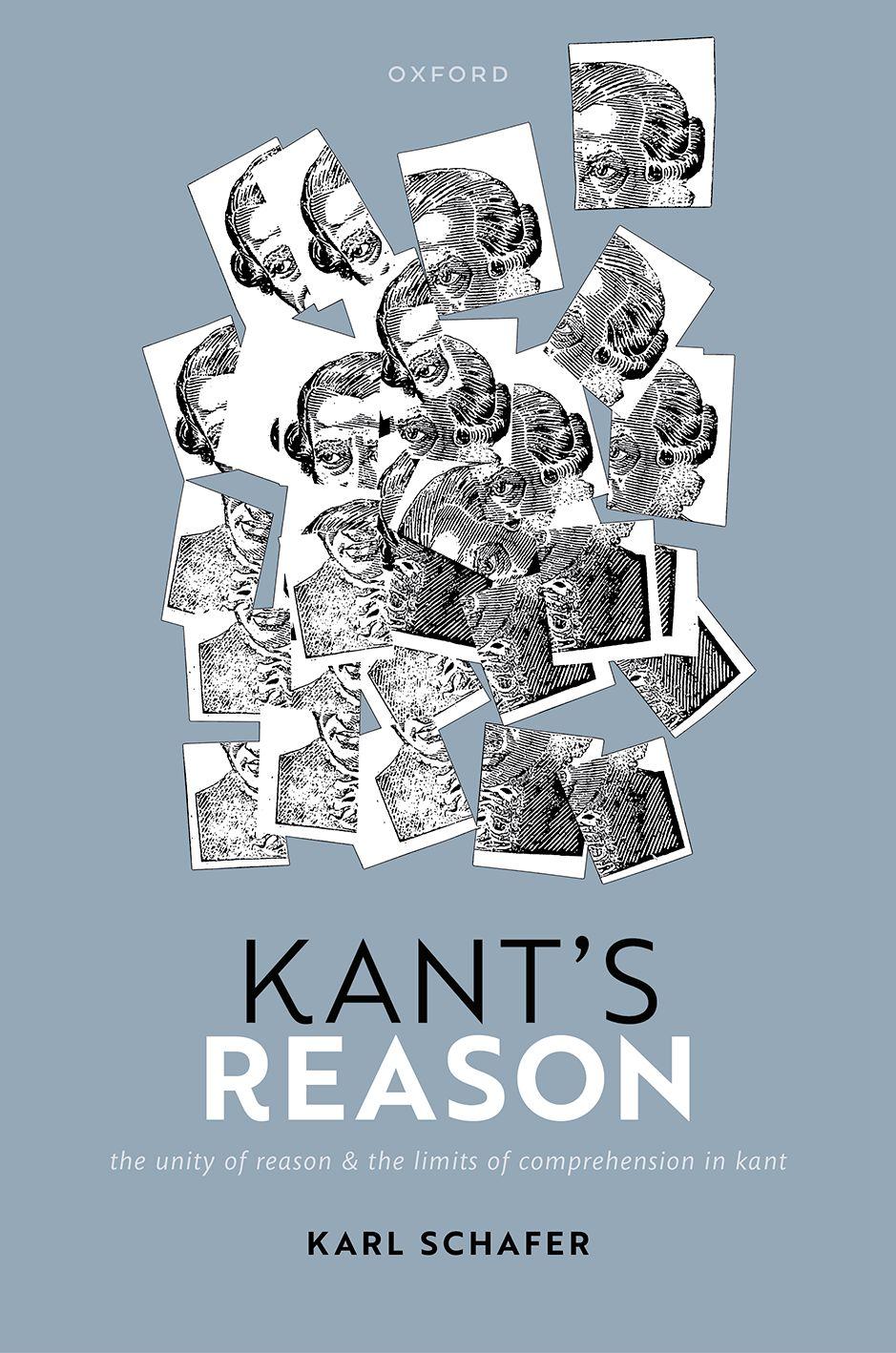

Finally,IwouldliketothankmywifeMauraMurnaneforherquiteprofound supportthroughoutthisprocess.Thisbookwascompletedduringwhatwere easilythemostchallenging,butalsoultimatelymostrewarding,yearsofmylife. Againstthatbackground,itiscompletelytruethatIwouldn’tbeheretocomplete thisprojectifitwasn’tforMaura’ssupport.Ioweliterallyeverythingtoher,not leastofalltheimageonthecover.

Thisbookisdedicatedtothememoryofmymother,whowouldhavegracefully (ifregretfully)acceptedmydesirenevertodiscussitwithher.

Iwouldalsoliketothankthepublishersofthefollowingarticlesforpermissionto reprintmaterialfromtheminwhatfollows:

“KantonMethod,” in TheOxfordHandbookofKant,ed.AStephensonand A.Gomes.Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,forthcoming.

“PracticalCognitionandKnowledgeofThings-in-Themselves,” in Kantian Freedom,ed.D.HeideandE.Tiffany.Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress, forthcoming.

“KantonReasonastheCapacityforComprehension.” AustralasianJournalof Philosophy,forthcoming.

“Kant’sConceptionofCognitionandOurKnowledgeofThingsinThemselves,” in TheSensibleandIntelligibleWorlds,ed.N.StangandK.Schafer.Oxford: OxfordUniversityPress,2022.

“ASystemofFaculties:AdditiveorTransformative?” EuropeanJournalof Philosophy 29.4(2021):918–36.

“TranscendentalPhilosophyasCapacities-FirstPhilosophy. ” Philosophyand PhenomenologicalResearch 103.3(2021):661–86.

“AKantianVirtueEpistemology:RationalCapacitiesandTranscendental Arguments.” Synthese 198(2021):3113–36.

“TheScenicRoute?OnErrolLord’ s TheImportanceofBeingRational ” PhilosophyandPhenomenologicalResearch 100.2(2020):469–75.

“Kant:ConstitutivismasCapacities-FirstPhilosophy.” PhilosophicalExplorations 22.2(2019):177–93.

“ConstitutivismaboutReasons:AutonomyandUnderstanding,” in TheMany MoralRationalisms,ed.K.JonesandF.Schroeter.Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press,2018.

ListofAbbreviations

TitlesofworksofKantareabbreviatedaccordingtotheirGermantitlesandinthestyle recommendedby Kant-Studien.Exceptasnotedotherwise,citationsaretovolumeand pageofthe AkademieAusgabe (AA):

ImmanuelKant, GesammelteSchriften,ed.:Vols1–22 PreussischeAkademieder Wissenschaften,Vol.23Deutsche AkademiederWissenschaftenzuBerlin,from Vol.24 AkademiederWissenschaftenzuGöttingen.Berlin:ReimerthenDe Gruyter,1900–.

Unlessnotedotherwise,KantisquotedaccordingtotheCambridgetranslationsofthe worksofKantspecifiedbelow.Wherenotranslationislisted,theCambridgeseriesdoesnot includeone.

ReferencestoHumeandHegelaresimilarlyformattedasnotedbelow.

A/B

AbbreviationsofKant’sWorks

KritikderreinenVernunft,Aedition(AA4),Bedition(AA3). CritiqueofPureReason.Trans.anded.PaulGuyerandAllenWood. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1998.

Anth AnthropologieinpragmatischerHinsicht (AA7). Anthropologyfromapragmaticpointofview.Trans.R.Louden.In Anthropology,History,andEducation.Ed.G.ZöllerandR.Louden. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2007.

B Briefwechsel (AA10–13).

Correspondence. Trans.anded.A.Zweig.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1999.

EEKU

ErsteEinleitungindieKritikderUrteilskraft (AA20).

FirstIntroductiontotheCritiqueofthePowerofJudgment.In Critiqueof thePowerofJudgment.Trans.anded.P.GuyerandE.Matthews. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2000.

GMS GrundlegungzurMetaphysikderSitten (AA4).

GroundworkoftheMetaphysicsofMorals.In PracticalPhilosophy. Trans.anded.M.J.Gregor.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1996.

HN

HandschriftlicherNachlass (AA14–23).

IAG IdeezueinerallgemeinenGeschichteinweltbürgerlicherAbsicht (AA8). Translationin Anthropology,History,andEducation

Log

KpV

KU

JäscheLogik (AA9).

JäscheLogic.In LecturesonLogic.Trans.anded.J.M.Young.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1992.

KritikderpraktischenVernunft (AA5).

CritiqueofPracticalReason.In PracticalPhilosophy.

KritikderUrteilskraft (AA5).

CritiqueofthePowerofJudgment.Trans.anded.P.Guyerand E.Matthews.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2000.

MAN MetaphysischeAnfangsgründederNaturwissenschaften (AA4). MetaphysicalFoundationsofNaturalScience.In TheoreticalPhilosophy after1781. Trans.anded.H.AllisonandP.Heath.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,2002.

MS DieMetaphysikderSitten (AA6).

TheMetaphysicsofMorals.In PracticalPhilosophy.

O WhatDoesItMeantoOrientOneselfinThinking? (AA8).

In ReligionwithintheBoundariesofMereReason. In Religionand RationalTheology.Trans.anded.A.WoodandG.diGiovanni. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1996.

OP OpusPostumum (AA21–2).

OpusPostumum.Trans.anded.E.FörsterandM.Rosen.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1993.

Prol ProlegomenazueinerjedenkünftigenMetaphysik (AA4). ProlegomenatoanyFutureMetaphysics.In TheoreticalPhilosophyafter 1781.

Refl Reflexionen (AA14–19).

Selectionsin NotesandFragments.Trans.anded.P.Guyer,C.Bowman, andF.Rauscher.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2005.

RGV DieReligioninnerhalbderGrenzenderbloßenVernunft (AA6).

ReligionwithintheBoundariesofMereReason. In ReligionandRational Theology.Trans.anded.A.WoodandG.diGiovanni.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1996.

SF DerStreitderFakultäten (AA07).

TheConflictoftheFaculties.In PracticalPhilosophy V-Anth/Collins VorlesungenWintersemester 1772/3Collins(AA25).

Translationin LecturesonAnthropology.Trans.anded.A.Woodand R.Louden.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2012. V-Lo/Blomberg LogikBlomberg (AA24).

Translationin LecturesonLogic V-Lo/Dohna LogikDohna-Wundlacken.

Translationin LecturesonLogic V-Lo/Wiener WienerLogik

Translationin LecturesonLogic V-Met/Dohna MetaphysikDohna (AA28).

Selectionstranslatedin LecturesonMetaphysics.Trans.anded. K.AmeriksandS.Naragon.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1997.

V-Met/Herder MetaphysikHerder (AA28). Selectionstranslatedin LecturesonMetaphysics.

V-Met/Mron MetaphysikMrongovius (AA29). Translationin LecturesonMetaphysics.

V-Phil-Th/Pölitz PhilosophischeReligionslehrenachPölitz (AA28). LecturesonPhilosophicalDoctrineofReligion.In ReligionandRational Theology.

AbbreviationsofHegel’sWorks

PR GrundlinienderPhilosophiedesRechts ElementsofthePhilosophyofRight.Trans.anded.A.Woodand H.Nisbet.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1991.

PS PhänomenologiedesGeistes ThePhenomenologyofSpirit.Trans.anded.M.BaurandT.Pinkard. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2018.

AbbreviationsofHume’sWorks

T ATreatiseofHumanNature. Ed.D.NortonandM.Norton.Oxford: ClarendonPress,2007.

Introduction

TheUnityofReasoninKantandToday

...theyrightlyoccasiontheexpectationofperhapsbeingablesome daytoattaininsightintotheunityofthewholepurerationalfaculty (theoreticalaswellaspractical)andtoderiveeverythingfromone principle theundeniableneedofhumanreason,which findscompletesatisfactiononlyinacompletesystematicunityofitscognitions.

(KpV5:91)

Kant’sinfluenceoncontemporarydebatesaboutreasonandrationalitywouldbe difficulttooverstate,andthereissurelynoshortageofinterpretativeworkon Kant’sviewsaboutreason,rationality,andrelatedtopics,orofcontemporary treatmentsofthesetopicsinabroadlyKantianvein.Onecouldthusbeforgiven forwonderingwhetherthereismuchleftforKanttoteachusaboutthese questions.Butdespitethisvastliterature,IbelievethatKant’sviewsaboutreason stillhavethecapacitytosurpriseus,andtodosoinphilosophicallyproductive ways.Itseemstomethat,inmanyways,westilllackasystematicaccountofsome ofthemostphilosophicallyvitalaspectsofKant’saccountofreason;indeed,some ofthemostcompellingaspectsofthisaccountwerenotfullydevelopedbyKant himself.SothereremainsmuchworktobedoneinunderstandingthephilosophicalsignificanceofKant’sconceptionofreasoninbothahistoricalandacontemporarycontext.

Inthechapterstofollow,IhopetodevelopareadingofKant’sconceptionof reason,itsunity,anditssignificanceforhisphilosophythathelpstobringout someoftheseaspectsofhisaccount.Indoingso,myfocuswillultimatelybeon twotopics.First,IwillarguethatKantpresentsuswithapowerfulmodelfor understandingthe unity oftheoreticalandpracticalreasonastwomanifestations ofaunifiedcapacityfor understanding (orwhatKantcalls “comprehension”)of bothatheoreticalandpracticalsort.Aswewillsee,thinkingofreasoninthis “understanding-first” or “comprehension-first” mannerallowsustodojusticeto thedeepcommonalitiesbetweentheoreticalandpracticalrationality,without reducingeithertotheotherinthemannerthatmanyattemptstoexplainthe “unityofreason” implicitlydo.Forexample,bythinkingofreasonintheseterms, Kant’sReason:TheUnityofReasonandtheLimitsofComprehensioninKant.KarlSchafer,OxfordUniversityPress. ©KarlSchafer2023.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780192868534.003.0001

wecanseewhytheactivitiesof both theoreticalandpracticalreasonaregoverned byaversionofthe PrincipleofSufficientReason,andthatKant’svariousformulationsofthemorallawarebestunderstoodasattemptstoexpressthisprincipleas itappearsinthecontextofpracticalreason.Butthroughapproachingreasonin thisway,wecanalsoseewhyweshouldbecautiousabouttheusethat(say) rationalistmetaphysicianshavemadeofthisprincipleinattemptingtoconstructa fullydeterminateconceptionofthefundamentalnatureofreality.Thus,by investigatingtheseissuesthroughthelensprovidedbytheideaofreasonasthe facultyforcomprehension,wecanbetterunderstand both therobustprinciples fortheoreticalandpracticalthoughtthatfollowfromthenatureofreason and the limitsthatKant’scriticalphilosophyplacesonouruseoftheseprinciples.

Atthesametime,andthiswillbemysecondmaintheme,IwillarguethatKant alsopresentsuswithacompellingmodeloftherolethatreason(asacapacityor power)shouldplayindevelopingasystematicapproachtofoundationalquestions inphilosophy.Inmakingthispoint,Iwillfocusprimarilyonwhatisnowcalled “metaethics”—thatis,foundationalquestionsaboutthenormativedomain.More precisely,IwillarguethatbythinkingthroughKant’smeta-normativecommitments,wecanarriveatanaccountofthefundamentalnormsthatapplytousas rationalbeingsthattreatsasexplanatorilyfundamental,notasubstantiveconceptionofthe objectivereasonsandvalues thatexist “outthere” intheworld,nora merelystructuralorformal conceptionofthe “requirementsofrationality”,but insteadarobustconceptionofreasonasapowerorcapacity namely,reasonas thecapacityforunderstanding(boththeoreticalandpractical).

Ibelievethatthissortof “ reason-first” or “understanding-first” perspectiveon thenormativedomaininmanywaysrepresentsthemostimportantlegacyof Kant’sphilosophyinmetaethics,alegacythatcontemporaryformsofconstructivism,expressivism, and constitutivismalldrawfrom,albeitindifferentways.¹

WhileIhavediscussedKant’srelationshiptoexpressivismandconstructivism elsewhere,inmydiscussionhereIwillfocusmainlyonKant’srelationshipto constitutivism,arguingthatKantdefendsaformofwhatwemightcall “ reasonfirstconstitutivism” or “rationalconstitutivism” aboutthefundamentalnorms thatapplytous.²

AsIwillexplain,Ibelievethatthisformofconstitutivismmoreelegantly expressesKant’scorephilosophicalcommitmentsinthisareathandothe formsofagency-firstconstitutivismthathavedominatedthecontemporary debate.Buttheresulting “ reason- first” approachtometa-normativequestions mayalsobecontrastedwiththecontemporaryvogueforformsof “ reasons fundamentalism”—thatis,forviewsthattakethenotionofareason qua (roughly)

¹Formorediscussionoftheseconnections,see(Schafer2014a,2015b,2015c,2018b).

²Comparethedefenseofa “dialectic-first” approachtothe first Critique in(Kreines2022).

a “considerationthatcountsinfavor ” asfoundationalfornormativephilosophy.³ Inthisway,theconceptionofreasonanditsplaceinphilosophyIwillbe defendingrepresentsareturntoamoretraditionalviewofthesequestions,one thatseemstomelessmysteriousfromametaphysicalandanepistemological perspectivethancontemporaryformsof “reasonsfundamentalism.” Indoingso, oneofmyaimswillbetovindicateKant’sinsistencethathisphilosophyisnothing moreorlessthantheefforttobringreason’simplicitself-understandingtoexplicit andsystematicself-consciousness theidea,thatis,thatKant’sformof “constitutivism” simplyrepresentsthenormativeself-consciousnessofreason,asthe powerforunderstanding,inaphilosophicalform.

Ifthisisright,thenKant’sconceptionofreasonchallengescontemporary philosophicalorthodoxyalongseveraldimensions.First,indevelopingasystematicpictureofthenormativedomain,ittreatsasfundamental,not reasons or values or rationality or(say) fittingness,butrather reason asacertainsortof cognitivepower.Second,unlikemorefamiliarsortsofconstitutivisminthe philosophyofaction,indoingsoittreatsasfundamental,notour distinctively practical powersas agents,butratherreasonasthepowerforunderstandingof both atheoretical and apracticalsort.Andthird,itcharacterizesthenatureofthis capacityorpower,notinthe “knowledge-first” termsthathavecometodominate contemporaryanalyticepistemology,butratherintermsoftheaimof understanding or makingsenseof things,boththeoreticallyandpractically.Inmotivatingtheseclaims,IhopetodevelopareadingofKant’sphilosophyonwhichthat philosophyiscenteredaroundreasonasa self-organizingpowerforunderstanding, boththeoreticalandpractical.

a.The “UnityofReason” inKant

Inallthesewaysandmore,itseemstomethatKant’saccountoftheseissuesstill hasmuchtoteachus.ButwhileIhopethatthesecommentsgivethereaderataste ofsomeofwhatItakethecontemporarypayoffsofmydiscussiontobe,myfocus herewillnotgenerallybeonthecontemporarydebate.Rather,inwhatfollows, IwillgenerallyforegroundinterpretativequestionsabouthowweshouldunderstandKant’sexplicitand(sometimes)implicitviews.Inconsideringthesequestions,IwilloftenusethephilosophicalpayoffsofKant’sviewsinacontemporary contexttohelpillustratemyreadingofKant,butImakenoclaimtofullydevelop

³See(Parfit2011;Scanlon2014;Kiesewetter2017;Lord2018;Schroeder2021).Forsomecritical discussionofsuchviews,see(Schafer2018a,2020).Anotherinterestingpointofcomparisonhereare viewsthatfocuson “ reason ” asmassnouninthesensediscussedin(Fogal2016),whichprovidean alternativewaytothinkabouttheideaof “respectingreason” Idiscussbelow(p.196).

thesepayoffsinasystematicmannerhere.ThatisataskthatImustleavefor anothertime.

Moreprecisely,inwhatfollows,myfocuswillbeKant’sconceptionoftheunity ofreasonandtherolethatthisconceptionplaysingivingstructuretohis philosophicalproject.Unfortunately,asissooftentruewithKant,merelyto utterthephrase “theunityofreasoninKant” istoinviteconfusion.Forthere are,infact,avarietyofissuesinKant’sphilosophythatmightreasonablybetaken tobetheproperreferentofthisphrase,includingquestionsabouttheunityof reasonasacapacity,theunityofourvariousrationalcapacitiesmorebroadly,the relationshipbetweenthesensibleandintelligibleworlds,andtheunityofphilosophyitself.

AsI’vealreadyindicated,ininquiringintothe “unityofreason”,myfocuswill beonreasonasa unifiedcapacity or power or faculty. ⁴ Butquestionsaboutthe unityofreasoninthissensecanbefurtherbrokendownintoatleasttwosubquestions,forKantuses “ reason ” bothinanarrowandabroadsense.Inits narrowsense,thetermrefersonlytothefacultyofreason inparticular,whereasin itsbroadoneitreferstothewholesystemofallour “higher” intellectualfaculties, including(atleast)reason,theunderstanding,andthepowerofjudgment.

Whenreadinthe first,narrowerfashion,toaskaboutthe “unityofreason” isto inquireintowhatexplainstheunityofreasonasonerationalcapacityamong others.Here,themostpressingquestionwithrespecttoreason’sunityrelatesto theunityofreasonasacapacity acrossthetheoreticalandpracticaldivide.For,as Kantoftenstresses,theideathatasinglecapacityofreasonisresponsibleforboth theoreticalandpracticalreasoningisfundamentaltothecriticalproject:

Irequirethatthecritiqueofapurepracticalreason,ifitistobecarriedthrough completely,beableatthesametimetopresenttheunityofpracticalwith speculativereasoninacommonprinciple,since therecan,intheend,beonly oneandthesamereason,whichmustbedistinguishedmerelyinitsapplication. (GMS4:391)

Butevenifwefocusonreasoninthe first,narrowersense,thisishardlytheonly questionabouttheunityofreasonthatarisesinaKantiancontext.Foronboththe theoreticalandpracticalsidesofthisdivide,Kantprovidesavarietyofdifferent characterizationsofthenatureofreasonascapacity,bothintermsofitscharacteristicaimorfunctionandintermsofitscharacteristicprinciple.Themost famousinstanceof this dimensionofthe “unityofreason” involvesthe

⁴ Kantusesavarietyoftermstorefertomentalcapacitiesorfaculties,including Vermögen, Fähigkeit (generallytranslatedas “capacity” or “ability” andindicatingabroaderclassofabilities than Vermögen),and Kraft.Thereisconsiderablescholarlydebateabouttheexactrelationshipbetween theseterms,butinwhatfollowsIwillgenerallyuse “capacity” , “ power ”,and “faculty” interchangeably torefertowhatKantreferstoby “Vermögen” .

relationshipbetweenKant’svariousformulationsofthesupremeprincipleof practicalreasonorthemorallaw.But,aswewillsee,thisishardlytheonlycase inwhichKant’sclaimsabouttheoreticalandpracticalreasonchallengeusto explainexactlyhowreasoncanbeunifiedinthemannerthatKantclaimsitis. Thus,eveninthisnarrowersense,thestatusofthe “unityofreason ” isanything butunproblematic.

Formuchofwhatfollows,itistheunityofreasoninthis firstsensethatwillbe myexplicitfocus.Butitisimportanttostressthatthisissueiscloselyconnected withquestionsaboutthe “unityofreason” inthesecond,broadersense.Afterall, withrespecttothisseconduseof “ reason ”,wecanalsoinquireaboutthe “unityof reason ”,notwithaneyetowardstheunityofreasonasaparticularrational capacity,butinsteadwithaneyetowardsthesenseinwhich all ourrational capacities,takentogether,formaunifiedsystem.Forexample,onKant’saccount, theoreticalrationalityinvolvesessentialcontributionsfromtheunderstanding (Verstand),thepowerofjudgment(Urteilskraft),and(insomeform)sensibility, inadditiontoreasonproper(Vernunft).Andmuchthesameisalsotrueof practicalrationality.Thus,muchaswecaninvestigatetheunityofreasonasa particularfaculty,wecanalsoinquireaboutwhatunifiesthesevariousrational capacities.Andthistoocanbereferredtoasaquestionaboutthe “unityofreason” ifweuse “ reason ” inthesecond,broadersenseofthisterm.

Aswillbecomeclearinwhatfollows,Ibelievethesetwoquestionsaretightly connected.Forintheend,whatgivesunitytothewholesystemofourrational capacities i.e.reasoninthebroadsense canonlybethehighest(andmost autonomous)ofthesecapacities namely,reasoninthenarrowsense.Inother words,tograsptheunityofallourvariousrationalcapacities,wemustunderstand thesecapacitiesasforminga teleologicalsystem thatisorganizedaroundtheends thataredistinctiveofreasoninthenarrowsense.ForKant,thefullsystemof rationalcapacities(or “ reason ” inthebroadsense)acquiresitsunityprecisely throughbeingthewaycreatureslikeusrealizethedistinctiveaimsof “ reason ” in thenarrowsenseasthehighestofthesecapacities. ⁵ Asthisindicates,inorderto understandthe “unityofreason” inthesecond,broadsense,wemustbeginwith anunderstandingof “ reason ’sunity” inthe first,narrowsense.Toavoidconfusion onthispoint,inwhatfollowsI’llgenerallyreservetheterm “ reason ” forthefaculty ofreasoninthenarrowersenseanduse “rationalfaculties” or “rationalcapacities” torefertothebroadersystemofrationalfaculties.

Unfortunately,thishardlyexhauststhepotentialambiguitieshere,forthereis alsoathird,closelyrelated,senseinwhichthe “unityofreason” mightbetakento pickoutatopicofinteresttoKant.ThisrelatestothecharacteristicallyKantian ideathatthedistinctive aimorfunction ofreasonis(atleastinpart)to bring

⁵ See(Schafer2022a).

systematicunity toour(theoreticalandpractical)cognitions.⁶ Notsurprisingly, thiswillbeacentralcomponentofKant’saccountoftheunityofreasonasa faculty.For,aswewillsee,itpreciselyreason’sdistinctiveinterestinsystematic understanding(or “comprehension”)thatmakessystematicunityincognitionso importantforit.Anditisintheserviceofthissortofsystematicunitythatreason organizesitsownactivities,andthoseofourothercognitivefaculties,intoa teleologicalsystemliketheonejustdescribed.Butthis,ofcourse,raisesfurther questionsaboutKant’saccount.Forexample,itisonlynaturaltoaskwhat explainsorjustifiesreason ’sspecialinterestinthis “projectofunification”;orto wonder,withmanyofKant’scritics,whetherKant’stightassociationofreason withsystematicunitymightbebetterregardedastheexpressionofasortof extremeintellectualneuroticism.⁷

Aswewillsee,manyofthemostpressingobjectionstoKant’sphilosophyrelate insomewaytothisquestion.Andit,inturn,givesrisetoafourthsenseinwhich the “unityofreason ” isanissueofinteresttoKant.Itisthisfourthsenseofthe “unityofreason” thatKantmostoftenuses Vernunftseinheit torefertoinhis criticalworks namely,the “unityofreason” asthatunitywhichreasonseeksto discoverand/orproduceasaresultofitsunifyingactivity:

Iftheunderstandingmaybeafacultyofunityofappearancesbymeansofrules, thenreasonisthefacultyoftheunityoftherulesofunderstandingunder principles.Thusitneverappliesdirectlytoexperiencetoanyobject,butinstead appliestotheunderstanding,inordertogiveunity apriori throughconceptsto theunderstanding’smanifoldcognitions,whichmaybecalledthe ‘unityof reason ’ ....(A302/B358)⁸

Notsurprisingly,thisunitycanalsobeeithertheoreticalincharacter aunitythat characterizesthedomainofnatureundercausallaws;oritcanbepractical that is,aunitythatcharacterizesthedomainoffreedomundertheprinciplesof autonomy;or,mostimportantly,itcanrefertoaunitythatencompassesboth thesedomains thatis,aunityofnature and freedominasinglesystemof principles.

⁶ Compare: “Underthegovernmentofreasonourcognitionscannotatallconstitutearhapsodybut mustconstituteasystem,inwhichalonetheycansupportandadvanceitsessentialends.Iunderstand byasystem,however,theunityofthemanifoldcognitionsunderoneidea.Thisistherationalconcept oftheformofawhole,insofarasthroughthisthedomainofthemanifoldaswellasthepositionofthe partswithrespecttoeachotherisdeterminedapriori” (A832–3/B860–1).Forsomeoftheextensive discussionoftherelationshipbetweenreasonand “systematicunity”,see(Guyer1987,2000,2005, 2006;Neiman1994;Rauscher2010;Willaschek2018;Proops2021).

⁷ Forafamousexpressionofthisconcern,see(AdornoandHorkheimer1997).

⁸ Seealso: “Theunityofreasonisthereforenottheunityofapossibleexperience,butisessentially differentfromthat,whichistheunityofunderstanding” (A306/B363).

Itisthisdimensionofthe “unityofreason” thatseemedmostproblematicto manyofKant’simmediatesuccessors.But,inthecontextofKant’sCopernican Turninphilosophy,itisimportanttostressthatthisunityisbestthoughtofasthe “objectiveface” oftheunityofreasonasacapacity(inthe firstandsecondsenses justnoted).Moreprecisely,aswewillsee,inthecontextofKant’scritical philosophy,thereisasystematicrelationshipbetween(i)theunityofthecognitive subject,(ii)theunityoftheobjectswhichthatsubjectcognizes,and(iii)theunity oftheformsofcognitionthatrelatethatsubjecttotheseobjects.Thus,aswewill see,anyfacultyfor(theoreticalorpractical)cognitioncan,forKant,be(atleast partially)characterizedintermsof each ofthesethreeaspectsofthecognitive unitythatitseeks.Forexample,whilewecancharacterizereason’sinterestin systematicunitythroughcharacterizingthesortofunityitseekstoachievewith respecttoa subject’ s cognitionsorrepresentations,wecanalsocharacterizeits interestinsystematicunitybyfocusingonwhatthe objects ofsuchunified cognitionwouldnecessarilybelike.Orwecancharacterizeitbyfocusingonthe natureofthe relationship betweensubjectandobjectthatittherebyseeksto establish.Giventherelationshipbetweentheselevelsofexplanation,thequestion ofthe “unityofreason” inthisfourthsensecanbeunderstoodastheobjectiveface ofthequestionsabouttheunityofreasonascapacityraisedabove(p.5–6).Thus, bybetterunderstandingtheunityofreasonasacapacity,wecanalsomake progressinunderstandingKant’sprospectsfordevelopingasystematicaccount ofthe “unityofreason” inthisfourthsense.

Finally,thereisa fifthaspectofthe “unityofreason” thatwillalsobeimportant forthediscussiontofollow.Thisdimensionofthe “unityquestion” involves therelationshipbetweentheunityofreasonandtheunityofphilosophy itselfasasystematicbodyofcognition(ascienceor Wissenschaft).Sincewewill beginwiththisquestioninthenextchapter,Iwillpostponefurtherdiscussionofit untilthen.Butplainlyitiscloselyrelatedtothe “unityofreason” inthefourth sense,foragenuinelysystematicphilosophywillonlybepossible,forKant,insofar wecanachieveaunifiedaccountofbothnatureandfreedomwithinasingle system.

b.ExplainingtheUnityofReason PrimacyandUnity

Asthisshouldindicate,allthesevariousdimensionsofthe “unityofreason” are closelyconnected.Nonetheless,myfocusherewillbeontheunityofreasonasa capacity,bothacrossthetheoreticalandpracticaldivide and oneithersideof thisdivide.This,ofcourse,isatopicthathasreceivedconsiderableattention overtheentirereceptionofKant’sphilosophy.Indeed,ithasbeensaidthatthe fundamentalcomplaintoftheGermanIdealistsaboutKant’sphilosophywas preciselythat:

...Kantlacksacommonprincipleforthetheoreticalandpracticalusesofreason thatissuchthatitallows[him]tobringtheoreticalphilosophy(thedomainof thetheoreticaluseofreason)andpracticalphilosophy(thedomainofthe practicaluseofreason)intoaconnectionthatisaccountedforbyreason’ s commandtoachievesystematicunity.(Horstmann2012,67)

Toorientourselves,itwillbeusefultobeginbybrieflydiscussingsomeofthe maininterpretativeoptionswithrespecttothisquestion,withaneyetowards situatingtheaccounttofollow.Todoso,let’sbeginwithafewpointsthatare relativelyuncontroversial.First,itisuncontroversialthatthereissomesensein whichKanttakesthecapacityofreasontobe “unified” acrossthetheoreticaland practicaldivide.Atthesametime,itisalsoclearthatKantstruggledthroughout thecriticalperiodtodevelopafullysatisfyingaccountofthis “unity”.Particularly importantinthisregardisKant’sviewthatthereissomesenseinwhichpractical reasontakes “primacy ” overtheoreticalreason.Forexample,asKantwrites, althoughreasonisfundamentallyunified,itisalsotruethat, “intheunionof purespeculativewithpurepracticalreasoninonecognition,thelatterhas primacy,assumingthatthisunionisnot contingent anddiscretionarybutbased apriorionreasonitselfandtherefore necessary ” (KpV5:121).

Asthisindicates,thereareatleast two questionstoconsiderwithrespecttothe relationshipbetweenthetheoreticalandpracticalreasoninKant namely,(i)the senseinwhichtheyforma unity and(ii)thesenseinwhichonetakes primacy overtheother.Itisusefultoconsiderthesetwoissuesinconjunctionwithone anotherbecausemanyofthemostprominentaccountsoftheunityoftheoretical andpracticalreason,bothwithrespecttoKantandmoregenerally,attemptto explain thesenseinwhichreasonis “unified” byappealingtoanexplanationof howeithertheoreticalorpracticalreasontakes “primacy ” overtheother.We mightcallsuchaccounts “primacy-first” accountsoftheunityofreasonsincethey beginwithapictureofhowoneofreason’smanifestationsispriortotheother, andthenuse this toexplainthesenseinwhichreasonisneverthelessunified.The mostobviouswayofspellingoutaprimacy-firstaccountis via areductionofone ofreason’smanifestationstoaspecialinstanceoftheother,butthereareotherless reductiveformssuchanexplanationmighttake.Whatiscommontoallsuch viewsisthattheyattempttoexplaintheunityoftheoreticalandpracticalreason byexplainingoneofthemanifestationsofreasonintermsofamorefundamental understandingoftheother.Thus,suchaccountsattempttoexplaintheunityof reasonbyassigningadeepandsystematicprioritytoeitherreasoninitstheoreticaloritspracticalform.

Thisgeneralstrategyshouldbefamiliar,bothfromthecontemporarydebate abouttheseissuesandfromrecentscholarshiponKant.Forexample,consider cognitivistsaboutintention.Suchviews,whichattempttoreduceintentionstoa specialclassoftheoreticalbeliefs,canbeseenasattemptingtoreduce(atleast

someformsof)practicalrationalitytoaspecialformoftheoreticalrationality.⁹ Thisstrategycanbeseen,forexample,inVelleman ’saccountofpracticalrationalityintermsofaspecialformofself-realizingpsychologicalself-understanding, orinSetiya’sattemptstoderivetheprinciplesofinstrumentalrationalityfroma cognitivistconceptionofintention.¹⁰ Butitcanalsobeseeninextremeformsof Platonismonwhichourgraspoffactsabout(say)thegoodissimplyoneformof theoreticalknowledgeabouttheworld thatis,aformofknowledgethatis distinguishedfromotherformsoftheoreticalknowledgeonlybythespecial characterofthefactsthataretherebyknown.¹¹

Aswewillsee,thiswayofapproachingthesequestionsisnotcompletelyabsent fromtheliteratureonKant.ForonewaytounderstandKant’sfocusonreasonasa cognitive faculty(inbothitstheoreticalandpracticalmanifestations)istoseehim astreatingpracticalreasonas,insomesense,aspecialcaseoftheoreticalreason.¹² ButKant’sexplicitcommitmenttothe “primacyofpracticalreason” hasmadeit muchmorenaturaltodevelopaprimacy-firstapproachtoKantbytreating theoreticalreason,atleastincertainrespects,asaspecialmanifestationof practicalreason.

Themostnaturalwayofdevelopingthisideaistofocusontheideathat theoreticalreasoningandinquiryarethemselvesactivitieswecanintentionally engageinwithvariousaimsinmind.Thegeneralthoughtisthenthatwecantreat therequirementsoftheoreticalrationalityastheresultofapplyingthegeneral principlesofpracticalrationalitytothespecialcaseoftheoreticalreasoningand inquiry.Inthecontemporaryliterature,suchviewsaremostoftenassociatedwith thevariousformsofinstrumentalismabouttheoreticalrationalityorperhaps withtherecentwaveofinterestinvariousformsof “expectedepistemicutility”.¹³ ButthissortofinstrumentalismhaslittleplausibilityinaKantiancontext.Rather, intheKantliterature,thecentralideabehindsuchaccountshasgenerallybeen

⁹ Tobeclear,notallformsof “cognitivism” aboutintentionshouldbeviewedinthislight.But insofarasaviewreducesrationalityofintentionstotherationalityof theoreticalbeliefs,Ithinksuch descriptionsareapt.

¹⁰ (Velleman2000,2009;Setiya2007).

¹¹Forcontemporarydefensesofsomethinglikethisformofrealism,see(Shafer-Landau2003; Enoch2013;Larmore2021;Bengsonetalforthcoming).Suchviewsareoftenassociatedwiththe influenceof(Murdoch1970).

¹²Somethinglikethisviewmightbeassociatedwith(Engstrom2009),butthatwould(Ithink) involveamisinterpretationofhisviews,althoughsomeofthoseinfluencedbyEngstrommaygo furtherinthisdirectionthanEngstromhimself.Similarly,consider(Merritt2018)’sclaimthat, “moral virtueisaspecificationofgeneralcognitivevirtue,andthatgeneralcognitivevirtueisnothingother thanthenotionofhealthyunderstanding” (8–9).Now,IthinkthereisasenseinwhichwhatMerritt heresaysisquiteright,but,aswewilldiscussbelow,Idon’tthinkherprecisewayofdevelopingthis ideafullycapturesthesenseinwhichKantdoestreatpracticalreasonashaving “primacy” over theoreticalreason.Foraclearerexampleofthistendency,see(Elizondo2013),whichgoesfurtherin thisdirection.

¹³See(Kelly2003)foranimportantcriticaldiscussionofsuchviews;see(Rinard2017)fora prominentrecentdefenseofthem;see(Worsnipforthcoming)forfurtherdiscussion.

thattherequirementsoftheoreticalreasoncanbederivedfromthesupreme principleofpracticalreason namely,someformofthecategoricalimperative.

The locusclassicus forthisreadingisO’Neill’sground-breakingaccountofhow thecategoricalimperativeappliestotheoreticalreasoning.¹⁴ Inherdiscussion, O’NeillarguesthatforKant,reason’sproperfunctioninginboththepracticaland thetheoreticalcasesisfundamentallyamatter not ofaspecialsortofcognitionbut ratherofaparticularsortofautonomousactivity.Particularlyimportantinthis regard,forO’Neill’sKant,aretheactivitiesofcommunication,argument,and negotiationthatoccurbetweendifferentrationalindividuals,activitiesthataimat securingthefreeagreementofallparties.Thus,forO’Neill,notonlyisKant’ s conceptionofreasonfundamentally practical asopposedtocognitiveatitscore,it isalso socialandpolitical throughout.Indeed,thisis so trueforO’Neillthat, accordingtoher,Kant’sconceptionofreasonestablishes “nothing ...aboutprinciplesofcognitiveorderforsolitarybeings.”¹⁵

Aswewillsee,Iamsympathetictoaversionoftheideathatreasonis,forKant, essentiallyintersubjectiveinsomesense.ButIamskepticalofthequasiHabermasianwayO’Neillunderstandssuchclaims.Inanycase,whatisimportant forpresentpurposesislessO’Neill’sparticularproposalthanhergeneralstrategy: O’Neillbeginswithacertainconceptionofthenatureofpracticalreasoningand thenattemptstoaccountfortheoreticalreasoningintermsofthismorefundamentalconceptionofreasonaspractical ratherthan theoretical.Onthispoint, manyotherKantscholarsareinfundamentalagreementwithO’Neill.Forexample,inherclassicstudy TheUnityofReason,NeimanarguesthatKantsecuresthe unityofreasonbyoverturningafundamentallycognitiveconceptionofreason and replacing thiswithapracticalconceptionofthesame.¹⁶ Thus,forNeiman’ s Kant, “Reason’snatureisthoroughlypractical;itsproblemscannotbesecuredby attainingknowledge.”¹⁷ Andalthoughthingsaremorecomplexinthiscase,there arealsosignificantelementsofthisapproachwithinKorsgaard’shugelyinfluential

¹⁴ See(O’Neill1989).Formorerecentdevelopmentsofthislineofinterpretation,see(Cohen2013, 2014)and(Mudd2016,2017).Muddisespeciallyclearontheinterpretativepointhere,statingthat,on herreading, “reasonisa ‘unity’ becauseallourreasoning,includingourtheoreticalreasoning,functions practically” (1).

¹

⁵ (O’Neill1989,27).Compare(Habermas1981).Suchclaimscapturesomethingveryimportant aboutKant’sconceptionofreason namely,thatthisconceptionofreasonisessentiallyintersubjective in some sense.Buttheysecurethisresultonlybypresentingamisleadingandratherone-sidedreading ofit.Forwhileaconceptionof “communicativereason” does follow fromKant’sunderstandingof reason,itdoesnotprovideuswiththemostfundamentalcharacterizationofreasonasKantunderstandsit.Rather,forKant,therationalsignificanceofcommunicationissomethingthatisexplainedby deeperfeaturesofreason,suchastheconnectionbetweenwhatKantcalls “comprehension” (roughly speaking,understanding)andintersubjectivity.Thus,whileO’NeillisrighttostressthatKant’ s conceptionofreasonconstrainstheformsrationalcommunicationandnegotiationcantake,and whiletheyarealsocorrecttothinkthatreason’sabstractdemandscanoftenonlybe madedeterminate throughanactualprocessofcommunicationandpoliticalnegotiationbetweenrealagentsintheworld, theyarewrongtothinkthattheideaofsuchcommunicationiswhatdrivesKant’saccountofreasonor servesasitsfoundation.

¹⁶ (Neiman1994,7).¹⁷ (Neiman1994,7).

treatmentofKantonthe “sourcesofnormativity”,¹⁸ forKorsgaard ’saccountof thosesourcestakesthemtoberootedinournatureas agents.Thus,albeitina somewhatdifferentfashionthanO’NeillandNeiman,Korsgaard’saccountofthe natureofreasonsandrationalityalsotendstoprivilegepracticalrationalityor agencyovertheoreticalrationalityinitsattempttoreconstructKant’sviews.¹⁹

Aswewillsee,therearemanygenuineinsightsinalltheseinterpretations.²⁰ But contrarytothemall,IbelievethatwecannotdojusticetoKant’sviewsby adoptinganyviewonwhichthe “primacyofpracticalreason” ispriortothe “unity” oftheoreticalandpracticalreasonastwomanifestationsofasingle capacity.²¹Indeed,itseemstomethatKant’saccountfunctionsinexactlythe oppositefashion:ForKant,Iwillargue,itisonlypossibletounderstandthesense inwhichpracticalreasonhasprimacyovertheoreticalreasonbydrawingona prior,andmorefundamental,understandingoftheunityoftheoreticaland practicalreason.Insteadofaviewthattreatseithertheoreticalorpracticalreason asmorefundamentalthantheother,IbelievethatwecanonlydojusticetoKant’ s viewsbydevelopingaviewofreasononwhichtheunityofreasonasacapacityis trulyfundamental.Indeed,Ibelievethatoneofthemainphilosophicalattractions ofKant’sphilosophyispreciselythatitpresentsuswithapowerfulmodelfor developingthissortof “unity-first” accountoftherelationshipbetweentheoretical andpracticalreason anaccount,thatis,thatallowsustounderstandthisunity withoutgivingsystematicprioritytoeitherformofreasonovertheother.

c.ThePrimacyofthePracticalandReason’sEnds andInterests

Inthisway,alloftheviewsdiscussedabove,theirmanyinsightsnotwithstanding, seemtometomischaracterizeKant’sattempttorevolutionizehowwethink aboutreason.Forthepointofthisrevolutionisnotto replace afundamentally cognitivemodelofreason with apracticalone;rather,itistoshowusthatthese twomodels,onceproperlyunderstood,arenotjustcompatiblebut mutually

¹⁸ (Korsgaard1996a,2008,2009).

¹

⁹ Forsomeconcernsaboutthisapproach,see(James2007)and(Schafer2018b,2019a,2019b). IthinksimilarconcernsarisewithrespecttoMichaelSmith’slessexplicitlyKantianformofconstitutivismaswell.See(Smith2012,2015,2017).

²⁰ Alsoworthmentioninghereare(K.L.Sylvan2020),whichbeginstodevelopaKantian epistemologythatisfoundedonthevalueofrespectforthetruth.Ithinkthisisamuchmore promisingwayofextendingKant’streatmentofpracticalreasontothetheoreticaldomain,andwill returntoitbelow,butIthinkitdoesdistortKant’sownviewstosomedegreeinsofarasittreats somethingotherthanreason(orrationalnature)asthefundamentalobjectofrespectinboththe theoreticalandpracticalspheres.

²¹Thisisalsostressedby(Guyer2019).Forfurtherdiscussionsee(Guyer1987;Wood1999; Gardner2007;Timmermann2010;Piper2012,2013;Mudd2016).

entailing.²²Inotherwords,tounderstandKant’sconceptionoftheunityof reason,wemust firstgraspthatheaimstoexplainreason ’sunity,notbyprivilegingoneofthesemodelsofreasonovertheother,butbyshowinghow theynaturallyconvergeonasinglemodelofreasonas bothcognitiveandpractical toitscore.

Ifthisisright,thentounderstandKant’saccountoftheunityofreason,we mustlookbeyondtheideathat,asNeimansays, “itispracticalreasonwhich replacesspeculativereason, ” inordertograspthedeeperunitybehindboth reason ’sspeculativeandpracticalmanifestations.²³Onapurelytextuallevel,the basisforthisreadingofKantseemstomestrong.Forexample,whileKantdoes insistthatpracticalreasonhas “primacy ” overtheoreticalreason,indoingso,he makesclearthatthis “primacy ” involves “theprerogativeoftheinterestofone [practicalreason]insofarastheinterestoftheothers[e.g.theoreticalreason]is subordinatedtoit.” Thus,thecentralclaimofKant’sprioritythesisrelates specificallytotherelationshipbetweenthe interests ofpracticalreasonandthe interests oftheoreticalreason:Thethesisholdsthatthe interests ofpracticalreason musttakepriorityoverthe interests oftheoreticalreason.Andwhenwegoonin thispassage,we findthatKantexplicitlycommitshimselftotheviewthatitisthe underlyingunityofreasonasafacultythat explains whypracticalreason’ s interestshaveprimacyinthisway.Forheemphasizesthattheprimacyofthe interestsofpracticalreasonrestsonthefactthat “itisstillonlyoneandthesame reasonwhich,whetherfromatheoreticalorapracticalperspective,judges accordingtoaprioriprinciples” (KpV5:121).Thus,forKant,itwouldbea mistaketotaketheprimacyofpracticalreasontobewhat explains reason ’ s unity;rather,heisquiteexplicitthattherelationshipbetweentheseideasisthe opposite.²⁴ Itistheideaoftheoreticalandpracticalreasonastwoexpressionsof thesinglecapacitythat explains whypracticalreasontakes “primacy ” over theoreticalreason.

Tobegintounderstandwhythisistrue,itwillbehelpfultopauseheretobriefly discusshowKantconceivesofthesortofinternalteleologythatischaracteristicof rationalcapacitieslikereason.Inconsideringthis,itisimportanttostressthat

²²Thisideahasbeenstressedby(Engstrom2002,2009),althoughhedoesnotdevelopitinthe mannerIdo.Forotherversionsofthisidea,see(Kern2006;Reath2010,2013;Rödl2010;Merritt 2018).Ofcourse,theideaofreasonasbothcognitiveandpracticalisnotuniquetoKant.Rather,it extendsthroughmuchofthevaguelyAristoteliantradition.ButIthinkitisfairtosaythat(forKantat least)noneofthese figuresdofulljusticetobothsidesofreason.Forexample,someonelikeAquinas would,byKant’slights,havefailedtofullycapturethepracticaldimensionofreasonpreciselyinsofar ashefailedtodevelopaconceptionofreasonastrulyautonomous.Still,itisfairtonotethatKant’ s revolutiononthesepoints likeatallrevolutions tosomedegreeinvolvesanattempttorecovera traditionforthinkingaboutreasonthathad(atthetimeKantwaswriting)fallenintodisrepute.

²³(Neiman1994,4).

²

⁴ Onthispoint,Iagreewith(Timmermann2010)whenhewritesthat, “thelegitimacyofpractical reason ’ s fillinginthegapsleftopenbytheoreticalreasonisphilosophicallyrespectableonlybecause thereisonlyonefacultyofreason” (195).

throughout thecriticalperiodKantisconsistentindescribingtheactivitiesofsuch capacitiesinteleologicalterms,speaking,forexample,ofthe “ends” and “interests” theypossess.Indeed,aswewillsee,ateleologicalconceptionofourcognitive powersisimplicitinKant’sbasicconceptionofcognitionitself,whichsees cognition(andsoourcognitivecapacities)asstrivingtoperfecttheirrelationship withtheirobjects.Inkeepingwiththis,Kant’sconceptionofreasonisalwaysthe conceptionofacertainsortofself-organizingcognitivepower.Theconceptof suchapowerdoesnot firstappearinhisphilosophywiththethird Critique; rather,theprojectofthethird Critique istoextendKant’spriorunderstandingof theinternalteleologyofrationalpowerssothatteleologicalconceptscan also be usedtothink(insomesense)aboutthingsinnature.Itwouldthusbeamistaketo imaginethatteleologicalconcepts firstenterintoKant’sphilosophywiththe discussionof(say)naturalteleologyinthethird Critique.Kant’sconceptionof reasonisdeeplyteleologicalfromthestart.²⁵

ButwhydoesKantassociate “ends” or “interests” withfacultiessuchasreason inthemannerhedoes?Andwhydoesthisassociationgiverisetoa “primacyof practicalreason” withrespecttothoseinterests?Afullanswertothesequestions willhavetowaituntilChapter4,butwecanbegintointroducesomeofthe importantaspectsofKant’sanswertothembybrieflyconsideringKant’sofficial definitionsof “end” and “interests”.The firstofthesereadsasfollows:

[Anendis]theconceptofanobjectinsofarasitatthesametimecontainsthe groundoftherealityofthisobject.(KU5:180,compareMM6:381)²⁶

Inpassageslikethisone,Kantprovidesanabstractdefinitionofan “end”.So defined,anendisjusttheconcept(orrepresentation)ofanobjectinsofarasthat representationisapotentialgroundoftheexistenceofwhatitrepresents.Asthis makesclear,Kant’sconceptionofwhatanendistiesthisnotioncloselytogether withthesortof “practicalrepresentations” thatfunctiontobringintoexistence whattheyrepresent.We’llreturntothisnotionof “practicalrepresentation” in Chapter2.Butforthemomentthemostimportantimplicationofthisdefinitionis thefollowing:ForKant,toliterallyascribeanendtosomesystemorfacultyisto thinkofthatsystemorfacultyas governedbyarepresentationofthatend,a representationthatfunctionsasapotential ground ofwhatitrepresents.

Sometimesthesegoverningrepresentations(ofasystem’sends)willbeexternal tothesysteminquestion asistrue,accordingtoKant,withartifacts,whoseends

²⁵ Fortheimportantofthispoint,seeLonguenesse’sfoundationalworkonthesetopics,towhich Iwillreturnbelow,andinparticular(Longuenesse1998,2005).

²⁶ SeealsoKant’sdefinitionofa “ purpose ” inthethird Critique: “insofarastheconceptofanobject alsocontainsthegroundfortheobject’sactuality,theconceptiscalledthething’ s purpose andathing’ s conformitywiththatcharacterofthingswhichispossibleonlythroughpurposesiscalledthe purposiveness ofitsform” (KU5:180).

are fixedbytheintentionsofthosewhomakeorusethem.Butthisisnotthecase withreasonanditsends.Rather,liketheendsoflivingthings,theendsofour rationalcapacitiesareinternaltothosecapacities.Rationalpowerslikereasonare thuscharacterizedforKantbyacertainsortof self-organizingcognitiveactivity,a cognitiveactivitythroughwhichtheystrivetorealizethemselvesbybringingform orstructuretothe “matter” thattheyoperateupon.Indeed,aswewillsee,theends ofsuchfacultiesareinternaltotheminamuch stronger sensethananythingthat istrueofnon-rationalanimals,atleastaccordingtoKant.Forinthecaseofour rationalfaculties,afacultyhastheendsitdoespreciselybecauseitsactivitiesare governedbyarepresentationofthoseends whichisitselfinternaltothatvery faculty.²⁷ Inascribingsuchendstoourrationalfaculties,Kantistreatingthe activitiesofthesefacultiesasgovernedbyarepresentationofthoseveryends,and heistreatingthesegoverningrepresentationsasinternaltothefacultiesthemselves.Thus,theideaofsuchfacultiesashavingsuchendsiscloselyconnected,for Kant,withtheideaofthemasguidedbysomesortof(implicitorexplicit) awarenessorrepresentationoftheseveryends.²⁸ Itisthis,aswewillsee,that explainsthetightconnectionthatKantseesbetween,ontheonehand,theselforganizingactivitiescharacteristicofrationalityand,ontheother,theselfconsciousor “apperceptive” characterofrationalthoughtandaction.

Naturallyenough,Kant’sdefinitionof “interests ” buildsuponhisconceptionof an “end” by(effectively)addingafurtherelementtoit:

Thesatisfactionthatwecombinewiththerepresentationoftheexistenceofan objectiscalledinterest.Hencesuchasatisfactionalwayshasatthesametimea relationtothefacultyofdesire,eitherasitsdetermininggroundorelseas necessarilyinterconnectedwithitsdeterminingground.(KU5:204)

Accordingtothisdefinition,tospeakofsomeoneorsomethingas “interested” in somethingistospeakofthemas takingsatisfactioninitsexistence .Such “satisfaction” canbeeitherintellectualorsensibleforKant.²⁹ ButKantgenerally reservestalkof “interests” forcreatureswhoare finiteandsosubjectto needs:

²⁷ Onceagain,inthethird Critique,Kant extends thisaccountoftheconceptofanendtoallowfor an “analogical” useofthisconceptincognizinglivingthingsinnature.Buteventhere,Kantcontinues tomaintainthat insofar aswetreatnaturalthingsasgovernedbycertainends,wetreatthemas governedbysomerepresentationofthoseends.Thisconnectionremainsinforceevenwhenwemakea merelyanalogicalorregulativeuseofsuchascriptions.

²⁸ Ofcourse,theprecisenatureofthisawarenessisthesubjectofmuchdebate.Butlestthisseemtoo arcane,notethatsomeversionofthisideaisfundamentaltoevenbehavioristicattemptstorehabilitate thenotionofteleology.See,forexample,(Rosenblueth,Wiener,andBigelow1943,19): “Allpurposeful behaviormaybeconsideredtorequirenegativefeedback.Ifagoalistobeattained,somesignalsfrom thegoalarenecessaryatsometimetodirectthebehavior.”

²

⁹ Forexample,KantspeaksofGodtakingsatisfactioninhisownworks(V-Phil-Th/Pölitz28:1065). ButwhateversatisfactionGodiscapableofcannotbeamatterofsensiblefeelingsorthelikesinceGod isfreeoftheformsofsensibilityorreceptivityassociatedwithsuchfeelings.

“Allinterestpresupposesaneed[end]orproducesone” (KU5:210).Asaresult, thekindofsatisfactionthatKantassociateswith havinginterests requiresthe possibilityofa need thatonewouldhavean “interest” infulfilling.So,forexample, althoughKantiswillingtospeakofGodastaking “satisfaction” increation,he generallyavoidsspeakingofGodashaving “interests ”.Rather,forKant,talkof “interests ” isreallyonlyappropriatewithrespectto finiteor “needy ” creatures creatureswhotakesatisfactioninachievingtheirends,withouthavingany guaranteethatthiswilloccur.

Forthisreason,talkofinterests(asopposedtoends)isappropriateforKant onlywithrespecttocreaturesthatare both rational and sensiblyconditioned.And whensuchcreaturesaremovedtoactionbytheendstheyhaveset,thismotivation must “ appear ” onthelevelofsensiblefeelingintheirempiricalpsychologyin someway.Inotherwords,inordertomakeadifferencetosuchasubject’ s “motivationalset” ontheempiricallevel,evenpurelyintellectualsourcesof motivation likethemorallaw mustmakeadifferencetohowthatsubject feels onthelevelofempiricalpsychology.³⁰ Forthisreason,evenpurelyintellectualrepresentationslikeourrepresentationofthemorallawcanmoveasensibly conditionedcreaturetoactiononlyinsofarastheyareaccompaniedbysome feeling ofpleasureordispleasure.

Thus,whenKantattributesan “interest” toourfaculties,hemeanstocharacterizethesefacultiesashavingcertainendsbutalsotostressthattheseendsare associatedwithcorrespondingfeelingsofpleasureanddispleasure.³¹Itisthis packageofthefaculty’send,thesatisfactiongroundedinit,andthecorresponding feelingsofpleasureanddispleasure,thatconstitutesthe “interest” ofafacultyfor Kant.Kant’stalkofafaculty’ s “interest” referstothewayinwhichafaculty’ s “ends” necessarilymanifestthemselvesin finite,sensiblyconditionedcreatures likeus.³²

Aswewillsee,itisthisthatexplainswhyKantinsistssostronglythat “all interestisultimatelypractical” andthat(asaresult)theinterest “even...of speculativereasonisonlyconditionalandiscompleteinpracticalusealone” (KpV5:121).Thisistrue,inessence,becauseinattributingendsandintereststo ourpowerofreason,wearealsoattributingthoseendsandintereststoourselves;

³⁰ Itisforthisreason,amongothers,thatKantinsiststhatthemorallawcanonlybemotivationally efficaciousforcreatureslikeusinsofarasitisapotentialgroundofmoralfeelingssuchasthefeelingof respect.Formorediscussionofthesesortsof “rationalfeelings” inKant,see(Wood2007;DeWitt2014; Cohen2020).

³¹PassageslikeA797/B825,whereKantspeaksofthestrivingofreasonas “groundedin” itsvarious interests,mightsuggestaviewonwhichtheseinterestsare “pathological”.ButKant’sdiscussionofthe activitiesofpurepracticalreasonmakesitclearthatmanyoftheseinterestsarenotalways “pathological” inthissense.

³²Asthisindicates,ifone findsitmorenaturaltotranslateKant’sascriptionsofendsandintereststo reasonasacapacityintoascriptionsofthoseendsandintereststothe rationalindividualswhopossess thiscapacity,thatwillgenerallynotcausetoomanyproblems. But,asIdiscussinthenextchapter, thereareprincipledreasonsforKanttofocusonfacultiesandcapacitiesinthemannerhedoes.