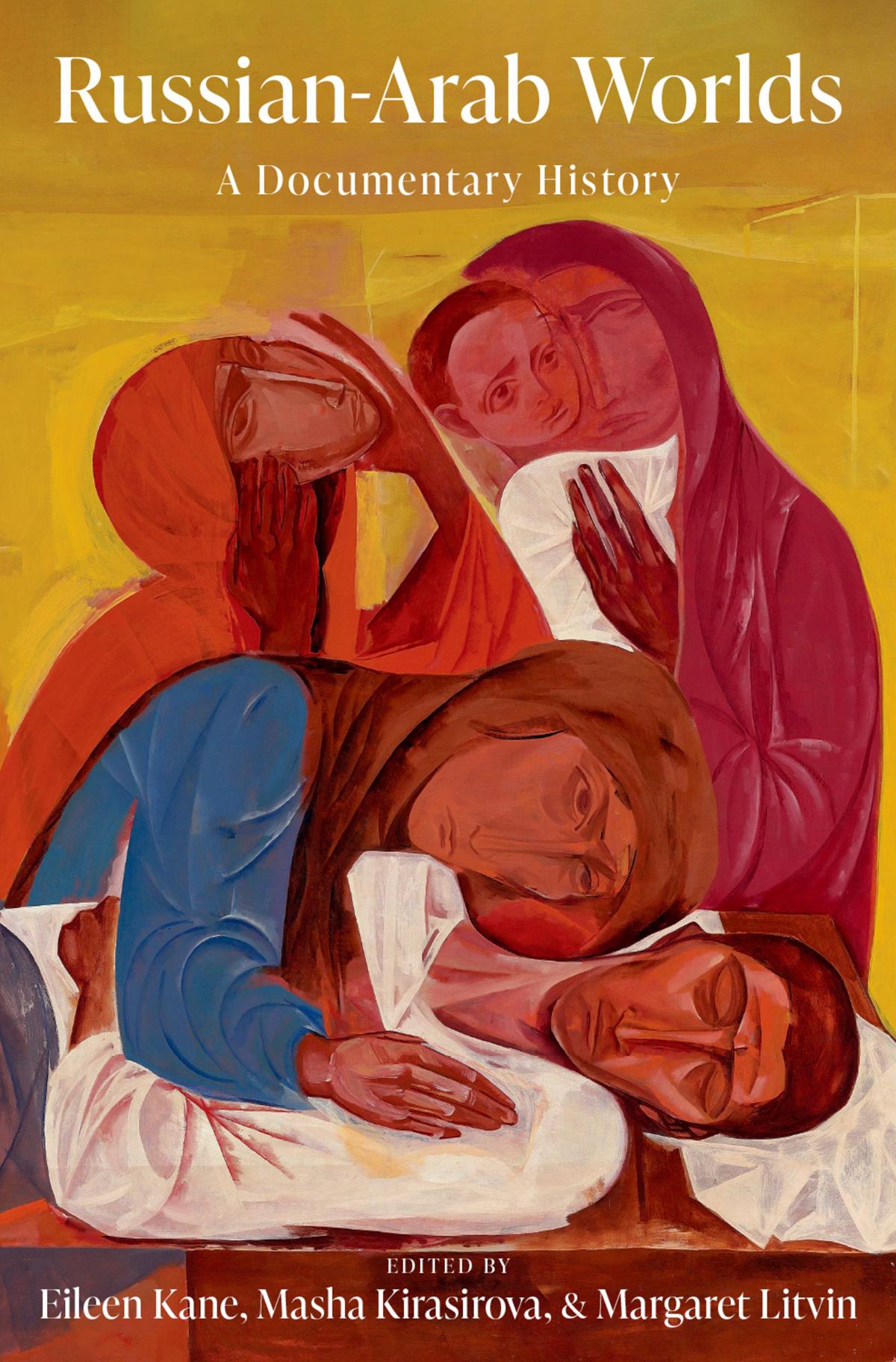

Russian-Arab Worlds

ADocumentary History

Editedby EILEEN KANE, MASHA KIRASIROVA, AND MARGARET LITVIN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978–0–19–760576–9

eISBN 978–0–19–760578–3

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197605769.001.0001

Contents

Acknowledgments

AbouttheCompanionWebsite

Introduction: Reconstructing Russian-Arab Worlds

EileenKane,MashaKirasirova,andMargaretLitvin

1. Witness to a New Era: Sergei Pleshcheev’s DiaryofaJourneyt oSyria(1773)

JohnRandolph

2. Extraterritorial Entanglements: Russian Jewish Migrants in Otto man Palestine (1830s–1850s)

EileenKane

3. Shi‘i Worlds Interrupted: Waqf and Pilgrimage in Russia’s South Caucasus (1863–1876)

ZeinabAzarbadegan

4. An Egyptian Teacher Heads to St. Petersburg: al-Tantawi’s Gift oftheWiseintheAccountoftheLandofRussia(1840)

SuhaKudsieh

5. With the Tsar’s Imprimatur: A Slave Sale Deed from Russia’s No rth Caucasus (1864)

SergeySalushchev

6. Population Transfer: Negotiating the Resettlement of Chechen Refugees in the Ottoman Empire (1865, 1870)

VladimirHamed-Troyansky

7. Russianizing Palestine: Vasilii Khitrovo’s AWeekinPalestine(18 76) and the Charter of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society (1889)

SpencerScoville

8. Manufacturing Russian Attachments to Palestine (1894–1903)

ElenaAstafieva

9. Orthodoxy across Borders: Maps of the Institutions of the Impe rial Orthodox Palestine Society (IPPO)

EileenKane

10. A Reluctant Native Informant: Shakirdzhan Ishaev’s Journey to Mecca (1896)

EileenKane

11. Quarantine Politics and the Hajj: Dr. Zabolotnyi’s Mission to the Red Sea (1897)

EileenKane

12. Saluting Russia’s Islamic Modernists in the Cairo and Beirut Ara bic Press (1899)

RoyBarSadeh

13. Russian and Soviet Oil Exports to the Persian Gulf (1903–1933)

MashaKirasirovaandEileenKane

14. Memo to Stalin: Lev Karakhan’s Argument for Establishing Sovi et Diplomatic Ties with the Hejaz (1923)

MashaKirasirova

15. Soviet Muslims at the Congress of the Muslim World in Mecca (1926)

NorihiroNaganawa

16. Arabic in the Early Soviet Caucasus: Nadhir al-Durgili’s TheDeli ghtofMindsintheBiographiesofDagestaniScholars(1920s–1 930s)

VladimirBobrovnikov

17. From Syrian Communist to Soviet Orientalist: Taha Sawwaf in t he Comintern Files (1935–1953)

MashaKirasirova

18. Wartime Schism in the Iraqi Communist Party: A Coded Letter t o Moscow (1944)

ElizabethBishop

19. Armenian Immigration to the USSR from Arab Countries (1946–1949)

AraSanjian

20. The Abandoned Comrades: Egyptian Communists’ Pleas to the USSR (1953–1954)

RamiGinat

21. Revisiting Russia after Fifty Years: Mikhail Naimy’s BeyondMosc owandWashington(1959)

MariaSwanson

22. From Nazareth to Moscow: Kulthum ‘Awda-Vasilieva’s “Happy Li fe” in Russia (1927, 1937, 1965)

NicoleKhayatandMariaVologzhanina

23. Statistics on Arab Students in the USSR (1959–1991)

ConstantinKatsakioris

24. Should Dormitory Bathrooms Have Doors? Zakaria Turki’s AnU pperEgyptianamongtheRussians(1967–1972)

MargaretLitvin

25. A Communist Mourning Icon: Mahmoud Sabri, Iraqi Art Student in Moscow (1960)

SuheylaTakesh

26. Soviet Yerevan’s Outreach to Armenians in Lebanon (1967–196 9)

AraSanjian

27. LotusMagazine: Soviet-Supported Afro-Asian Literary Transnati onalism (1969–1970)

RossenDjagalov

28. No Soviet Engineer to Walk in Front of an Egyptian One: Youss ef Chahine’s Two High Dam Films (1968 and 1970/2)

AlaYounis

29. Soviet Advisers in Egypt before, during, and after Their “Expulsi on” (1972)

IsabellaGinorandGideonRemez

30. Ba‘thists in Baku: Iraq-Syria Tensions Come to the USSR (1975 –1977)

ÉtienneForestier-Peyrat

31. Two Soviet Responses to Frantz Fanon (1978–1979)

PhilippCasula

32. Aeroflot Routes to Baghdad: Soviet-Iraqi Relations during the Ir an-Iraq War (1980–1981)

StevenE.Harris

33. Aleksandr Yakovlev’s Notes from His Conversation with the Kuw aiti Ambassador to the Soviet Union (November 26, 1990)

MarkKramer

34. “The Intellectual Is a Hybrid Creature”: Khalil Alrez’s TheRussia nQuarter(2019)

MargaretLitvin

Contributors

SelectedBibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

This book, spanning so many fields and languages, has benefited from the engagement of many supporters, colleagues, and friends. For the initial concept we thank the participants in the February 2017 Boston University workshop “Arab-Russian and Arab-Soviet Ties: Literature, History, and the Arts.” For suggesting an unbelievable variety of topics and helping track down sources and images we are grateful to all of our contributors, as well as to several friends of the project: Mark Katz, Alexander Knysh, Nabil Matar, Dana Sajdi, Sana Tannoury-Karam, and audience members at the 2018 conference of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES). Suzanne Ryan, then editor-in-chief for humanities at Oxford University Press, generously workshopped a draft proposal.

We especially thank Nikos Chrissidis for his generous help finding sources (that dazzling magic lantern image from Suvorin!), sharing his extensive knowledge about the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society and Russian Orthodox pilgrimage, and putting us in touch with other colleagues.

For helpful critical readings of draft chapters, and help with translation of obscure terms and tracking down crucial sources, we thank Eugene Avrutin, Vladimir Bobrovnikov, Molly Brunson, Michelle Campos, Sheetal Chhabria, Joshua Donovan, Michael Gordin, Greg Halaby, Peter Holquist, Susan Kashaf (MD), John Randolph, Stephen Riegg, Shira Robinson, Masha Salazkina, Tamir Sorek, Bob Vitalis, and Christine Worobec. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers from Oxford University Press for their perceptive and encouraging comments.

Valuable production support came from our home institutions: a Boston University Center for the Humanities publication production

award and BU Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program grant, a New York University–Abu Dhabi publications grant, and a Connecticut College Research Matters grant. Nicole Khayat and Maria Vologzhanina’s chapter on Kulthum ‘Awda-Vasilieva received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 723718).

For permission to reproduce images we are grateful to the State Museum of the History of Religion in St. Petersburg (GMIR); the Palestinian Museum’s Digital Archive; the Yale University Beinecke Library; Brill Publishing; Christie’s; the Barjeel Art Foundation; and the estate of Youssef Chahine. Special thanks to Petr Fedotov, head of the “Fotonegamultimedia” department at GMIR, for help locating photos; to Salim Abuthaher at the Palestinian Museum for expediting permissions; to Yasmin Ramadan at the Beinecke for help obtaining a scan; and to Victor Dzevanovsky for help identifying the officials pictured with Kulthum ‘Awda at the Kremlin.

We thank our undergraduate students Sbidag Demerjian and Michelle Ramiz for outstanding research assistance. Eileen thanks Nelson Rodriguez for sharing his brilliance with her in the final stages of this book.

It was a real pleasure to work with cartographer Bill Nelson and copyeditor Dan Geist. At Oxford University Press, we are grateful to Nancy Toff for her immediate enthusiasm for this project and her astute guidance on editorial matters, and to Brent Matheny for his help. We thank the OUP production team for their thorough and thoughtful work. Nirenjena Joseph kept the book on track, Timothy DeWerff brought his eagle eyes to the text, and Cindy Coan provided expert indexing help.

Our work on this anthology has frequently and sometimes uncomfortably resonated with present-day concerns, touching issues such as the status of migrants and minorities, the disruptions of study abroad, the public health dangers of global mass mobility, and the far-reaching effects of Russia’s imperial ambitions. While developing this book, completed during the Covid-19 pandemic, we have found both solace and inspiration in conversations with our

transnational array of brilliant friends and colleagues, our families, and each other. We are deeply grateful for the fun and fruitful collaboration this has been.

Introduction Reconstructing Russian-Arab Worlds

Eileen Kane, Masha Kirasirova, and

MargaretLitvin

The Soviet Arabist Kulthum ‘Awda-Vasilieva was born in 1892 to Orthodox Christian parents in Nazareth, in Ottoman Palestine. She died in Moscow in 1965, leaving autobiographical writings that help explain how this unwelcome fifth daughter of Palestinian peasants went on to become a distinguished Arabist in the USSR and possibly the first Arab female university professor anywhere. As she tells it in an essay translated in this book, luck played a role: the opening of an Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society (Russian acronym IPPO) missionary school in Nazareth in 1885 helped lift a girl her own mother considered “ugly” and lacking prospects into a world of educational opportunities and social and geographic mobility.1

After Nazareth, ‘Awda received a scholarship to the IPPO women’s seminary in Beit Jala and mastered Russian. As a young teacher back in Nazareth she met and married Ivan Vasiliev, a doctor at the IPPO hospital. On a summer 1914 visit to Vasiliev’s family in Kronstadt, the couple was stranded by World War I and stayed. After his death during the Russian Civil War the young widow, now called Klavdia Viktorovna Ode-Vasilieva, supported her three daughters by teaching hygiene and Russian literacy to peasants in Ukraine, before moving to what soon became Leningrad to work with the great Arabist Ignatii Krachkovskii. She would live in Russia for the next half century.

‘Awda-Vasilieva’s life story reveals larger histories at work. Her Nazareth school was part of the vast IPPO network of educational and medical institutions that anchored Russia’s presence in Ottoman

Palestine and Syria from 1882 to 1917; its seventeen-acre headquarters outside Jerusalem’s old city gates, pieces of which President Vladimir Putin’s government has reclaimed, is still called the Russian Compound today. (This book maps the IPPO’s network for the first time, based on an alumnus’s 1907 Arabic survey.)

Through a career that crossed the tsarist-Soviet divide and combined Arabic and Russian languages, ‘Awda-Vasilieva was buffeted by the collapse of empires and the political realignments that marked the twentieth century. As a Soviet scholar, she was arrested three times, first in 1930 and again during Stalin’s 19361938 purges, and lived through the Nazi siege of Leningrad; she translated literature, trained three generations of Soviet Arabists, researched Arab-descended Soviet peoples, assisted in Soviet outreach to visiting Arabic-language writers, and was awarded a Medal of Honor and Order of Friendship of the Peoples (Figure I.1).

Meanwhile, as a Palestinian intellectual she bore witness to the Arabic literary revival called the ‘asr jadid, or “new age” (later termed the nahda, or renaissance) and to the 1948 creation of Israel and resulting loss of her homeland. Her life story, while extraordinary for a woman of her place and time, is also emblematic: it reveals larger transregional processes that connected Arabicspeaking societies to imperial Russia, and later the Soviet Union.

Figure I.1 Nazareth- born Soviet Arabist Kulthum ‘Awda- Vasilieva seated next to Leonid Brezhnev at a June 1962 Kremlin celebration for her Medal of Honor and Order of Friendship of Peoples.

Courtesy of the Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, Tawfiq Zayyad Collection.

The roots of the Arab world’s current Russian entanglements reach deep into the tsarist and Soviet periods, but this shared history has been broken apart by scholars’ recent habit of studying the two regions separately, which, in turn, has limited our historical imaginations. Russian-Arab Worlds pieces this rich history back together using primary sources translated from Russian, Arabic, Armenian, Persian, French, and Tatar. These carefully chosen sources include archival, autobiographical, and literary texts, introduced by specialists and in some cases by pairs of scholars with complementary language expertise. Like short stories in an anthology, they offer kaleidoscopic glimpses of the many ways that Russia and the Arab world engaged and helped shape each other over more than two centuries, revealing structures and relationships

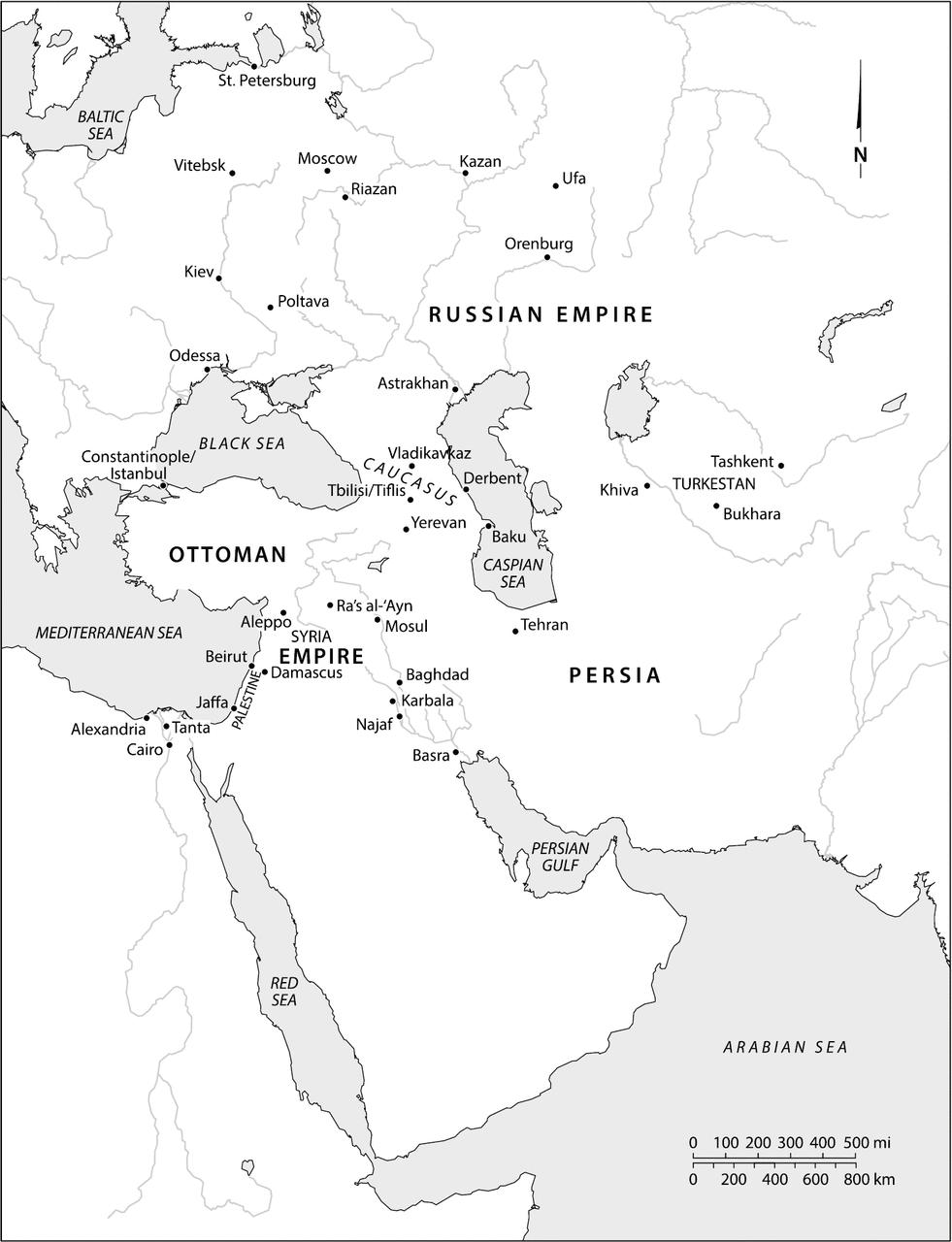

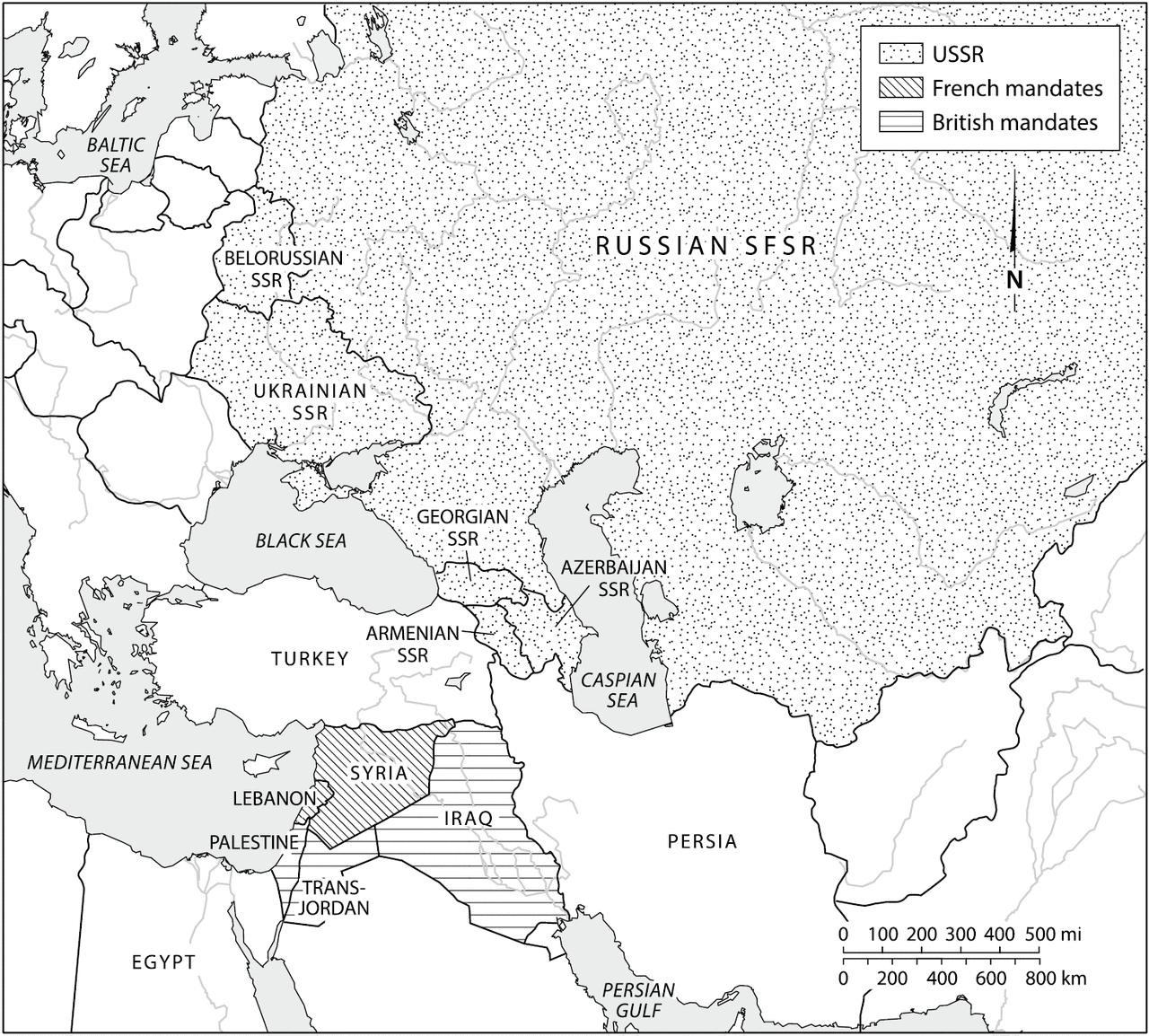

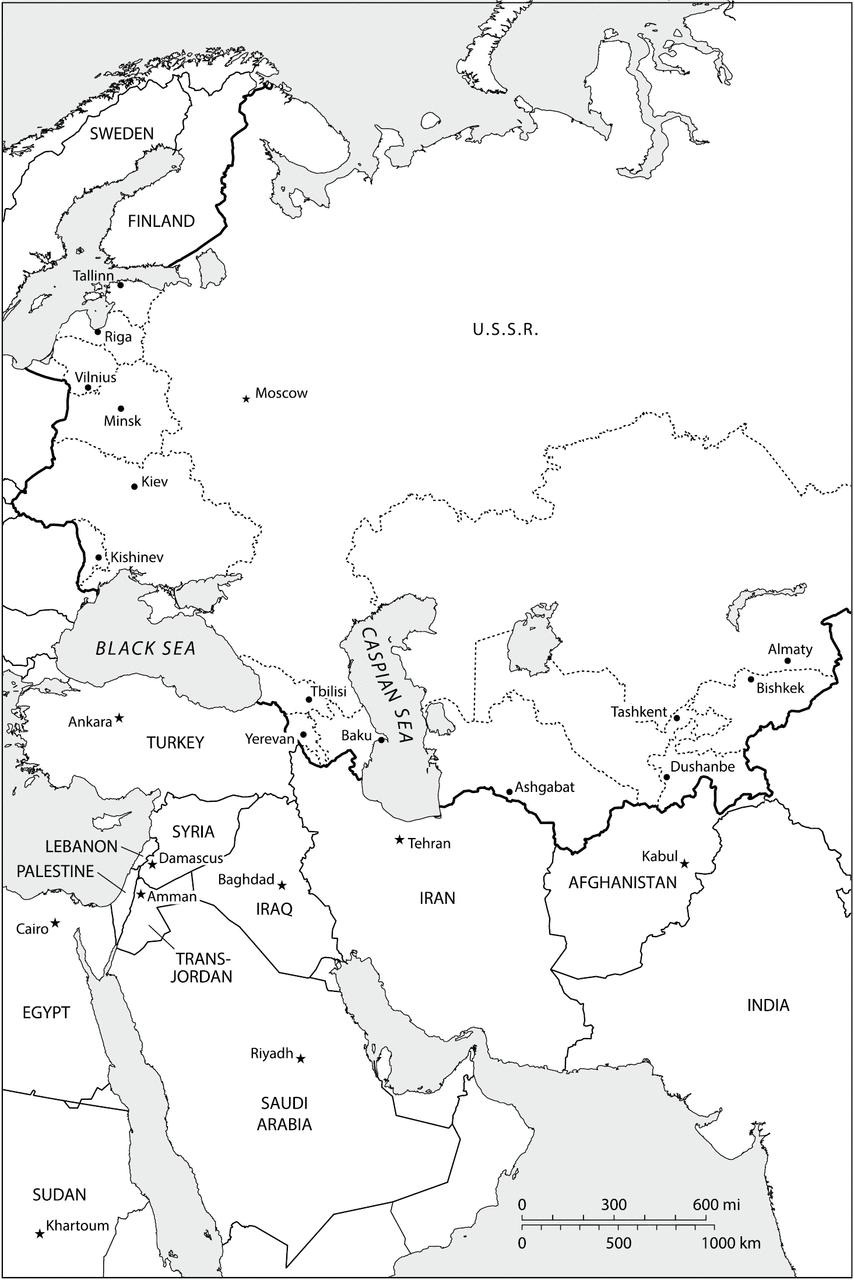

that the fields of area studies and global history have so far failed to see.2 We include a set of new maps to help readers get their geographic bearings amid the expansion and collapse of empires, many border changes, forced transfers of populations, and creation of new nation-states that occurred during the two centuries our sources cover.

The sources and introductions assembled here show how various Russian/Soviet and Arab governments sought to nurture political and cultural ties and expand their influence, often with unplanned results. They illuminate transnational networks of trade, pilgrimage, study, ethnic identity, and political affinity that state policies sometimes fostered and sometimes disrupted. Above all, they give voice to some of the resourceful characters who have sustained, embodied, and exploited Arab-Russian contacts: missionaries and diplomats, soldiers and refugees, students and party activists, scholars and spies.

We have chosen to arrange the chapters in chronological order rather than impose a thematic grouping. Given the many themes that cut across multiple chapters, we believe that different sets of connections will light up for each instructor or reader. As should already be clear from ‘Awda-Vasilieva’s example, the same life can be read from many angles: in her case, as a story about missionary education, interwar migration, Soviet studies of Arabic, gender across cultures, and even (in her ethnographic report from Uzbekistan translated here) the overlap between the USSR’s “domestic” and “foreign” Easts.

Other in-between characters are just as thematically rich. The 1896 hajj narrative of Shakirdzhan Ishaev, a Tashkent-born ethnic Tatar who becomes a Russian consular official in Jeddah, brings into focus Russia’s diplomatic efforts in Muslim societies, its involvement in the hajj (of which Ishaev’s article is the first known Russianlanguage account), as well as the predicament of the trusted Russian Muslim native intermediary disgusted by the “foreign and hostile dark people” whose culture he is assumed to understand. The file of Mecca-born Syrian Communist Taha Sawwaf (aka “Djoni

Vil’iams”), who studied at Moscow’s Communist University for the Toilers of the East (KUTV) in the 1930s, sheds light on Arab communism as well as patterns of study abroad, Soviet broadcasting in Arabic, and differing experiences of race in Syria and the USSR. And visual artist Ala Younis’s photo essay on Youssef Chahine’s two Aswan High Dam films (1968 and 1970) touches on themes of postcolonial Egyptian internationalism, Soviet infrastructure aid to Arab countries, censorship in the film industry, and (because Younis’s work is an artistic reconstruction) contemporary art’s response to all these.

A note on what we mean by “Russian-Arab Worlds”: we use “Russian” in a geographic sense capaciously, to mean not simply lands historically inhabited by Russian speakers, but the wider Eurasian spaces, home to many different ethnic and religious groups, that were conquered by tsarist and then Soviet regimes and ruled from St. Petersburg and Moscow from the 1770s through the 1990s. And by “Arab” we mean the Arab-majority but internally diverse societies that developed in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, which then became post-Ottoman successor states under semi-colonial British and French rule, then independent monarchies or republics. (For reasons of space, we focus solely on the Arab Middle East and not on North Africa, which would merit a documentary history of its own.) In using these terms, we do not mean to project contemporary formations onto the past, or to reproduce the nationalist assumptions of those who would reduce these regions to the majority ethnic groups that have dominated them politically in recent years. In fact, we aim to unsettle these traditional framings.

Each event or relationship described here invites at least three layers of analysis: what geopolitical contexts and big-picture strategic alliances made it possible? In which transregional circulations of ideas or objects does it participate? And how does it show the agency of individuals who move across borders or adapt to new historical frames, refashioning themselves to impress new audiences or simply to survive? By focusing on transregional phenomena—institution-building, exchanges of ideas or

commodities, and the movement of peoples—this book captures historical processes and complex lived experiences that national and regional framings cannot. It raises a set of questions that, we hope, will help map out a coherent interdisciplinary field of inquiry into Russian-Arab worlds.

The stories told by these sources do not fit the standard EuroAmerican periodizations, geographic categories, or assumptions about culture and religion (and about where certain groups of people “belong”) that have shaped the separate fields of Russian/Soviet/Slavic and Middle Eastern studies. It is important to consider the transregional effects of some canonical turning points such as 1774 (Russia’s military triumph over the Ottomans, and the start of its diplomatic expansion into Arab lands), 1882 (both the founding of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society and the first wave of organized Zionist migration from tsarist Russia to Ottoman Palestine), 1917 (the Balfour Declaration and the Russian revolutions), 1922–1923 (the establishment of the Soviet Union and the collapse of Ottoman Empire), 1945 (the approximate start of the Cold War), and even 1991 (the Soviet Union’s dissolution). However, the stories told here also attend to the continuities in Russian-Arab ties, documenting how they have morphed but endured across the tsarist, Soviet, and post-Soviet periods (or, in Middle East studies periodization, across the Ottoman, Mandate, and postcolonial periods). Transregional religious institutions, for instance, lived on as literary movements;3 pilgrimage routes using the newly opened Suez Canal inspired Russia to plant consulates and extend steamship lines carrying commodities such as sugar, matches, and especially kerosene from Baku to the Arabian Peninsula.4 Even post-Soviet Russia’s efforts, such as Putin’s support for Bashar al-Asad’s rule in Syria, have built on a history of military ties (Russia has leased a Mediterranean naval base in Tartus, Syria, since 1971), and their public face draws on a decades-old propaganda tradition touting Arab-Soviet, then Arab-Russian friendship.

Approaching transregional history looking for continuities rather than predictable breaks yields some unexpected insights. First, the

complexities of local agency come into sharper focus. Even in unequal Russian-Arab relationships, with more power flowing from Russia, Arab motivations matter. For instance, Russian naval commander Sergei Pleshcheev’s Diary ofa Journey to Syria (1773), presented in our opening chapter, describes how Russia’s navy entered the eastern Mediterranean Sea even before the 1774 Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca—because Arab allies invited it. A powerful local leader, Shaykh Zahir al-‘Umar al-Zaydani, had allied with Egypt’s enterprising “shaykh al-balad” or Mamluk governor, ‘Ali Bey al-Kabir, to rebel against the Ottomans and establish an independent statelet in northern Palestine.5 ‘Ali Bey went to ask assistance of Russia’s naval commander, Count Aleksei Orlov, in Paros, Greece; Russia’s Empress Catherine II approved. This 1772–1774 Russian naval adventure in Beirut, Haifa, and Jaffa—not, as typically narrated, Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798 invasion of Egypt was the earliest modern European military intervention in the Eastern Mediterranean.6

As for how we, as editors, decided to piece together the story into a larger narrative: our initial idea of studying bilateral exchanges between Russia and Arab societies quickly broke down. When we considered how the collected sources and stories fit together, it became difficult to see a clear boundary between the two regions, which have overlapping populations. Alone among the European colonial powers that sought to dominate Arabic-speaking lands in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Russian Empire and USSR shared border regions and populations with these places. People from a host of minoritized ethnicities—Dagestani Muslims, Tatars, Circassians, Armenians, Georgians, Azeris, Jews—were sometimes persecuted, sometimes courted as intermediaries between officials in St. Petersburg or Moscow and local populations in the Caucasus, Central Asia, or the Middle East.

The Egyptian Mamluk ruler ‘Ali Bey, for example, was by birth a Georgian peasant, from a territory that became a protectorate of Russia in 1783; he and his fellow Mamluk rulers, powerful though technically enslaved Muslim converts from the Caucasus, maintained

ties to their families and communities of origin.7 The Syria that greets Russian naval lieutenant Sergei Pleshcheev in ‘Ali Bey’s war camp is also filled with peoples “from the frontiers of Russia’s empire”: Armenians, Tatars, Ukrainians, Georgians, Greeks, Maronites, Muslims, Cossacks, Orthodox Christians, and Jews. Such diversity served tsarist and later Soviet policy goals in the Arab world, as officials sometimes exploited or even fostered strong religious or ethnic ties between groups in Russian and Arab lands for imperial ends.

Our transregional perspective draws attention to various sets of cross-border networks and the way those networks intersect with state policies. For instance, petitions and memoranda about Shi‘i waqfs (religious endowments) in Yerevan, present-day Armenia, help reconstruct the significance of religious institutions that once connected a large population of South Caucasus Shi‘i Muslims both to Qajar Iran and also to major Shi‘i shrine cities in Ottoman Iraq. After Russia conquered the South Caucasus in 1828, transferring this endowment income from Yerevan to Karbala suddenly became an inter-imperial negotiation involving the Russian, Ottoman, and Qajar empires.

A recurring theme we wish to stress is that religious solidarities are cultivated, not inherent. The clearest example is Russian Orthodox missionary activity in Ottoman Palestine. In the 1774 Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca that ended Ottoman control of the Black Sea, Russia was also, ambiguously, empowered to extend extraterritorial privileges to tsarist subjects in Ottoman lands. European imperial rivalries over the weakening Ottoman Empire had grown into the “Eastern Question,” and Russia felt the need to compete with overlapping French/Catholic and British/Protestant diplomatic and missionary activity in the Holy Land. Therefore, in the name of protecting Arab Orthodox Christians, Russian tsars beginning with Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) oversaw the creation of a large system of consulates, scholarly committees, and ecclesiastical missions to institutionalize Russia’s presence and influence in the region. By the 1830s, Russia had consulates in Alexandria, Aleppo,

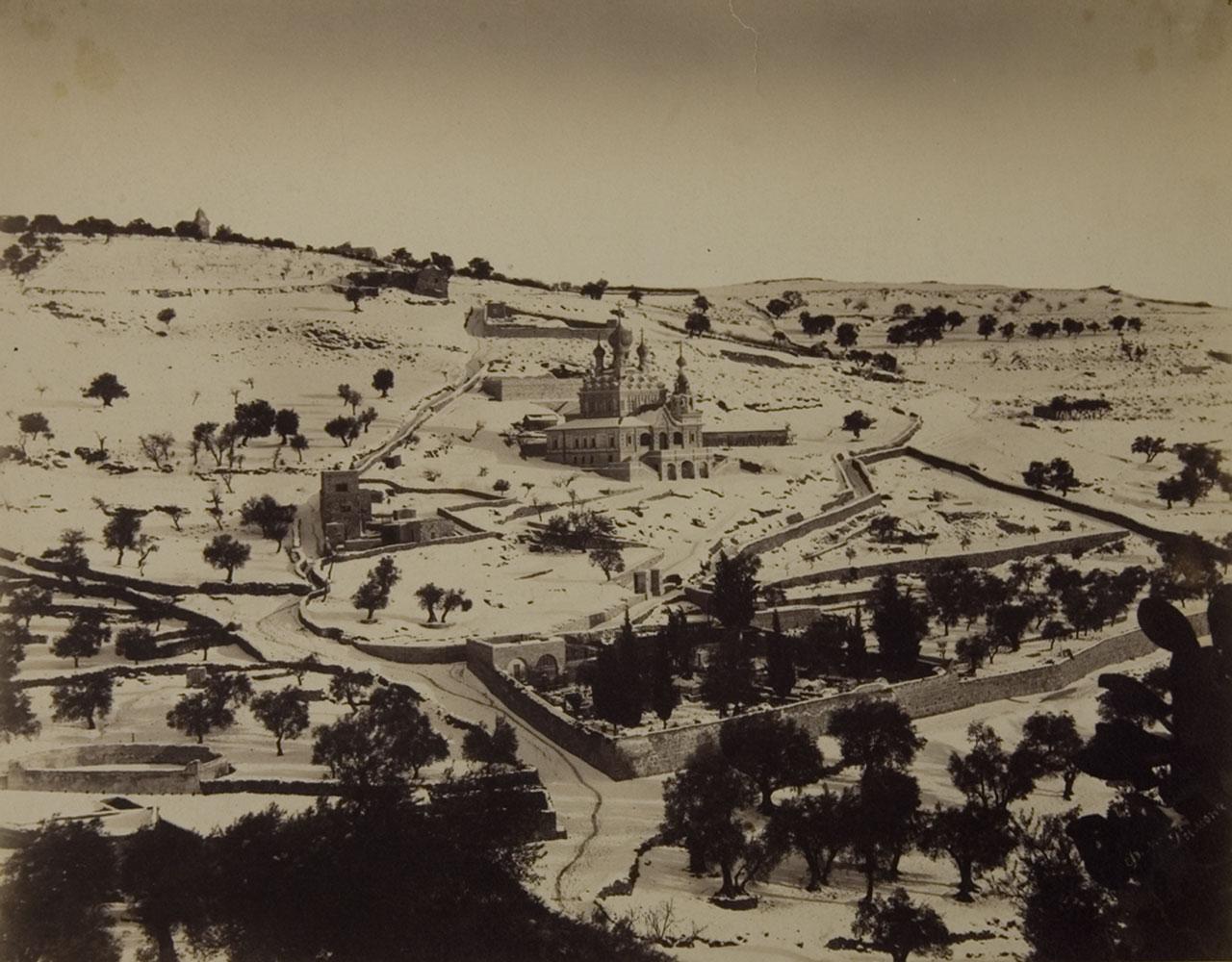

Beirut, Cairo, Damascus, Haifa, and Jaffa.8 The tsarist state also introduced “pilgrim passports” required for its subjects’ travel abroad, in order to gather data on their connections to holy sites in and around Ottoman Jerusalem and tap into these networks to build a Russian presence in Arab lands. And starting in the 1840s, Russian state officials (sometimes disguised as Orthodox pilgrims) surveyed the Holy Land for buildings and land that Russia could claim or buy. Crowds of Russian Orthodox pilgrims showing up in Jerusalem by the late nineteenth century reflected global changes in mobility: modern trains and steamships made pilgrimages of all kinds more accessible than ever before. They also reflected Russia’s success in cultivating cross-border Orthodox religious solidarity—by no means a preexisting feeling—and a more Jerusalem-centric practice of Russian Orthodoxy. The Orthodox Palestine Society was founded as a private group in 1882 largely through the efforts of Vasilii Khitrovo, whose fundraising travelogue and founding charter appear in English here for the first time; taken under government auspices as the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society (IPPO) in 1889, the group worked to streamline the work of several Russian religious institutions that had quickly bought land and begun operating in Palestine, and to cultivate lasting ties with local Christians by building more than 100 new madarismuskubiyya (Russian schools) in major cities and tiny villages throughout present-day Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. Visitors to Jerusalem can still see the results of this tsarist-era project in the built landscape: in the Russian Orthodox Convent of the Ascension atop the Mount of Olives (built between 1870 and 1887); the Russian Orthodox Church of Mary Magdalene, on the side of the Mount of Olives (built in 1888; Figure I.2); and the so-called Russian Compound (al-muskubiya) just outside Jerusalem’s old city walls (built between the 1860s and 1890s). In cities and villages across the Russian Empire, meanwhile, the IPPO carried out a creative and far-reaching propaganda campaign, complete with postcards and “magic lantern” picture shows, to encourage pilgrimage and build ordinary Orthodox Christians’ sympathy for the Holy Land.

Figure I.2 The snow-covered Russian Orthodox Church of St. Mary Magdalene on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, built in 1888.

Photo: Timon, 4 December 1888. Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of Religion, St. Petersburg (GMIR).

The state’s provisions for Christian solidarity could also be used in un-Orthodox ways. For instance, those same pilgrim passports were also used by Jewish families, some fleeing antisemitism in Russia, to migrate to Ottoman Palestine. As early as the 1840s, decades before organized Zionism,9 these “pilgrims” created Russian-affiliated Jewish communities in Palestine. During a dispute with Ottoman authorities in Safed, some of them asked for the consul’s extraterritorial protection as Russian subjects. The migrants intrigued tsarist officials: their passports were expired, but might they be worth protecting anyway? The very traits that had marked Jewish

subjects of the Russian Empire for suspicion (their tight-knit religious networks and perceived cross-border links) made them, once they had emigrated, potentially useful as cultural bridges or spies.

Similar suspicion of trans-imperial loyalties fell on the Russian Empire’s Muslims. In the decade after the 1853–1856 Crimean War, the tsarist government expelled or encouraged the emigration of nearly 900,000 Muslims (including Chechens, Circassians, and Tatars) from the Caucasus and Crimea on the claim that their Muslim solidarities with the rival Ottomans overrode their dynastic loyalty to the tsar.10 This enormous population transfer—missing from most accounts of modern European ethnic cleansing—moved hundreds of thousands of Muslims from Russian to Ottoman rule. The newly created Ottoman Refugee Commission resettled them mainly in Anatolia and today’s Jordan, Israel/Palestine, and Syria. They joined earlier waves of Caucasian Muslims (they called themselves muhajirs, Arabic for emigrants) who had fled the Caucasus on their own during Russia’s invasion and conquest (1817–1864).11 Yet their resettlement was no homecoming. Vladimir Hamed-Troyansky translates one Chechen migrant leader’s plea to the Ottoman Interior Ministry: after surviving Ottoman prison and torture, he is penniless, separated from his family and belongings, stranded without travel papers in a town where, being a farmer, he lacks the skills to make a living.

As nineteenth-century Russia both fought to absorb the Caucasus and pushed into the Holy Land, imperial anxiety and curiosity about Arabic and Islam opened opportunities for yet another sort of border-crossing. The North Caucasus could have provided Arabic teachers aplenty (the language was a lingua franca among polyglot indigenous scholars), but Russian academia looked further afield, inviting Egyptian scholar Muhammad ‘Ayyad al-Tantawi to St. Petersburg University in 1840. Tantawi’s cheerful travelogue, parts of which appear here in English for the first time, frames his journey from Cairo to St. Petersburg (including quarantine periods in both Istanbul and Odessa) as a passage to Europe different from the journey then fashionable in Egypt.12 In his 1848 textbook of

Egyptian colloquial (as opposed to classical) Arabic, one of the first ever written and the first by an Arab, al-Tantawi insists that St. Petersburg bears comparison to Paris:

La Seine est-elle moins large que la Néva?

[Isn’t the Seine as wide as the Neva?]13

The same approaches—seeking continuities in both state policies and social dynamics, seeing borderlands and contact zones rather than nationalist frames—have shaped our contributors’ insights into the period following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The Bolsheviks, as they gathered up the fragments of the shattered Russian Empire, also sought to rebuild its external diplomatic infrastructure, usually without acknowledging the role of any pre-revolutionary agents or structures. In the interwar period, Soviet leaders used diplomatic connections and by-now-traditional solidarities to challenge the power of the West embodied in its imperialist post-Versailles order. To this end, the USSR sought to participate in the interwar project of creating an imagined “Muslim world” by cultivating good relations with leaders of independent Muslim countries.

As in the tsarist period, key diplomatic posts were often held by members of non-Russian minorities. Armenian diplomat Lev Karakhan headed the Eastern Section of the Commissariat or Ministry of Foreign Affairs (NKID). Two Muslim diplomats, Tatar Karim Khakimov and Kazakh Nazir Tiuriakulov, were sent to represent Soviet Russia first to the Hejaz and then to the Kingdom of Najd (after 1932, Saudi Arabia). Karakhan’s characterization of the Hejaz as a “vulnerable site of European imperialism,” an echo of old Russian rivalries with the British Empire, formed the key context for Soviet Muslims to participate in the 1926 Mecca Congress organized by Ibn Saud. They did so with permission from the NKID and Soviet central security (OGPU).

Other in-between populations play prominent roles in developing Russian-Arab ties. Armenians, in particular, both relocated and mediated between the Russian or Soviet state and the Arab Middle