Thepurposeofenergystorage systems

2.1 Introduction

Beforewetakeadeeperlookatthemathematicaldescriptionandmodellingofstorage systems,wefirstwanttoinvestigatehowandwherestorageisused.Therearealarge varietyofapplicationsforenergystoragesystems.Infact,thereishardlyanyareain ourliveswhereenergystorageisnotused.

WestartinSection 2.2 withadiscussionaboutthereasonstorageisneededatall, anddescribethebasicapplicationsofstorage.Sinceenergystorageiscloselyrelated totheconceptofenergyandpower,weaddressthisaspect.Wealsodescribehow storagesystemscanbecharacterizedbytwoquantities:powerandenergydemand.

InSection 2.3 weinvestigatethedifferentapplicationsofstoragesystems.Westart withverysmallsystems,whichareusedmainlyineverydaymobileobjects.Wethen takealookatmobilityapplicationssuchaselectrifiedorhybridizedvehiclesandmobile workingmachines.

Inmobileapplications,energyisusuallystoredbeforethejourneybeginssothat thisenergycanbeusedduringthetrip.Theenergystorageisusedasafoodrationfor thejourney.InSection 2.3.3,welookatanotherlargeclassofapplications:stationary storagesystems.Theiruseiscloselylinkedtoourelectricitygridanditscharacteristics. Therefore,atthispointweexplainthestructureofthepowergridandthevarious waysinwhichenergystoragesystemscanbeusedinit.

2.2 Whatstorageisusedfor

Storingthingsisacommonprincipleinnature.Plantsstorewatertosurvivedry periods.Squirrelsgatherfoodtofallbackoninwinter.Otheranimalsdonotstore theirprovisionsinhiddenplaces,butcarrythemaswinterfatdirectlyintheirbodies. Thisensuresthattheirbodiescansurviveduringtimesofseasonalfoodshortage.

Wehumans‘store’moneythatwedon’tneednow,tospendlater.Wefillupthe tankofourcarbeforewestartalongtripand,unfortunately,wealsoputonsome bodyfatwhenweeattoomuch,becauseourmetabolismwantstomakesurethat westillhaveenoughenergyreservesinbadtimes.Whatalltheseexampleshavein commonisthattheprocessofstoringisalwayslinkedtothegoalofusingasurplus

Thepurposeofenergystoragesystems

ofsomethinginthepresenttocoverashortageinthefuture.Withstorage,therefore, onecanseparateproductionandconsumptionintime,butspatialseparationisalso possible:ahealthybreakfastathomecoverstheenergydemandwhilewework.Thecar isfilledupatthegasstationandconsumestheenergyofthefuelwhiledrivingacross thecountry.

Thereisalsoathirdapplication.Ifthechosenmethodoftransportdoesnotallow thetotalamountofsomethingtobetransportedimmediatelyandcompletely,then thedifferencecanfirstbestoredtemporarilysothattheactualtransportprocesscan takeplaceinseveralsteps.

2.2.1 Energyandpower

Inthisbookwelookatstoragesystemsthataredesignedtostoreenergy.Firstofall, energyisaphysicalquantitythatprovidesinformationabouthowmuchpowercanbe extractedoraddedintoaphysicalsystem.Considerasystemwhichhastheenergy content E0 at t =0s.Duringaperiodfrom t =0s until t = T s,powerisaddedand extractedfromthissystem.Thetimeseriesdescribingthisprocessis P (t).Adding time t = T s,theamountofenergyofthesystemcanbecalculatedby:

Exercise2.1 Consideramobilephonewhichalreadyhasastateofchargeof 24Wh.The mobileischargedduringthenight(8h)with 15W anddischargedovertheworkingday (12h)with 10W.Whatistheenergycontentofthemobilebattery?

Solution: Usingeqn(2.1)theenergycontentequals:

E(T )=24Wh+8h 15W 12h 10W=24Wh+120Wh 120Wh=24Wh

Therearethreegroupsofenergythatwewillencounteragainandagain:electricalenergy,mechanicalenergy,andthermalenergy.InTab. 2.1 belowwehavelisted descriptionsofeachofthese.

However,thedefinitionofenergypresentedineqn(2.1)showsthatinprinciple everyphysicalsystemtowhichanenergycanbeassignedisalsoakindofenergy storage.Forthistobethecase,wejustneedtobeabletoaddenergytothesystem atsometimeandsubtractenergyatadifferenttime.Infact,notallphysicalsystems canalsoserveasanenergystorage.Thisisbecauseitisalsonecessaryfortheenergy tobestoredforasufficientlylongperiod,asthefollowingexampleillustrates.

Whatstorageisusedfor 5

Table2.1 Differenttypesofenergydiscussedandusedinthisbook,includingtheirdefinitions.

Potentialenergy Epot = mg∆h

Kineticenergy Ekin = 1 2 mv2

Rotationalenergy Erot = 1 2 Jω2

Theenergyneededtoliftamass m from height h1 to h2. g isthegravitationalacceleration,whichdependsonthelocation. ∆h = h2 h1 istheheightdifference.

Theenergystoredinamass m,havinga velocityof v

Theenergystoredinarotatingbody. J isthemomentofinertia,whichreflectsthe massdistributionaroundtherotatingaxis. ω istheangularvelocityoftherotating body.

Electricalenergy Eel = UIt

Energyofcapacitor EC = 1 2 CU 2

Energyofaninductance EL = 1 2 LI2

Theenergyneededtoprovideacurrent flow I onagivenvoltagelevel U overa timeperiod t

Theelectricalenergystoredinacapacitor,withthecapacitance C andthevoltage levelof U .

Thetotalelectricalenergystoredinaninductancewiththeinductivityof L,whilea currentof I flowsthroughtheinductance.

Exercise2.2 Wewanttostore 3Wh intheformofkineticenergyinanobjecthavinga massof 12kg.Wewanttoextractthestoredenergyafteroneday.Whatdistancehasthe objecttravelledinthistime?

Solution: Thekineticenergyisgivenby

Theobjectthereforehasavelocityof

Thelongerthisenergyisstoredintheobject,thelongertheobjectwillmoveat 151.2 km h . Iftheenergyistoberetrievedafteroneday,theobjecthasalreadytravelledadistanceof 3,628 8km.Thus,translationalenergyismoresuitableforstoringenergyoverashorttime.

2.2.2 Efficiency:Thecostoftransformation

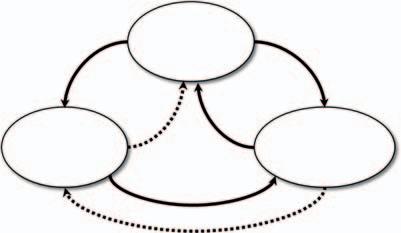

AsExercise 2.2 shows,noteveryformofenergyisequallysuitableforeverystorage application.Hence,theremaybeaneedtotransferenergyfromonetypeofenergy intoanother,moresuitableone.Inthisbookthemaintypesofenergyare:mechanical energy,beitintheformofkineticenergy,rotationenergy,orpotentialenergy;electricalenergy—thatis,currentandvoltage;andthermalenergy.Thesedifferentforms ofenergycanbeconvertedintoeachother(Fig. 2.1).

Noteverytypeofenergycanbetransformedwellintoanothertypeofenergy. Electricalandmechanicalenergy,forexample,canbetransformedintoeachother

Fig.2.1 Storagesystemsdealwiththestorageofmechanical,electrical,andthermalenergy. Theseenergiescanbetransformedintoeachother.Sometransformationsarequiteefficient, i.e.onlyasmallpartofthetransferredenergyislost.Thesolidlinesmarktheseefficient transformations.Thedottedlinesmarktransformationswhichshowgreaterenergylosses; thesearenotcommonlyusedinenergystoragesystemapplications.

verywell,becausethemovementofamagnetcangenerateanelectricalcurrentvia theLorentzforce.Withthehelpofanelectricmotor,movementcanbegenerated fromanelectriccurrentandelectriccurrentfromamovement,ifamagneticfieldis available.InSection 5.2.6 wewilllookatthisinmoredetailanddescribethenecessary technicalcomponents.

Electricalenergycanalsobeeasilytransformedintothermalenergy.Thermalenergyarisesbyitself,becauseeveryelectriccurrentgeneratesheatviatheresistanceof aconductor.

Fortheconversionofthermalenergyintoelectricalenergy,thethermoelectriceffect canbeused,inwhichtheheatingofaconductorcausescurrenttoflow.However, thiseffectisverysmall,sotheconversionusuallytakesplaceviatheintermediate stepofconvertingthermalenergyintomechanicalenergy.Anexampleofthisisthe combustionofcoalorgastogenerateelectricalenergy,Inthiscase,theheatcauses watertoevaporateandthissteamisusedtodriveaturbine.Therotationofthe turbinedrivesagenerator,whichproduceselectricalpower.

Thequalityofthesevariousconversionsisdescribedbytheefficiency.Theefficiency istheratiobetweentheenergy Ein,whichwewanttoconvertortransfer,andthe energythatisactuallyavailableafterwards, Eout:

InSection 3.2.1 wewilllookattheefficiency η anditsmathematicaldefinitionin moredetail.Theefficiency η isanimportantelementthatweneedfordescribingand designingenergystoragesystems.

Inordertodescribeanenergystoragesystem,wemustthereforebeclearabout whichtypesofenergyoccurandhowtheyaretransferredintoeachother.Theefficiency isanimportantcriterionfordecidingwhichtypesaretherightchoice.Inpractice,the applicationalreadydetermineswhichtypesofenergyarepresent.Ifwelookatavehicle withanelectricorhybriddrive,thetypesofenergyusedarealreadydetermined:the combustionengineisusedtoconvertheatintomechanicalenergy.Themechanical energyisusedtorotatetheaxleandthussetthecarinmotion,whichcorrespondsto atransformationofthermalenergyintomechanicalenergy.

However,theinternalcombustionenginecanalsodrivetheaxleofagenerator, whichusesthemovementtoproduceelectricitythatchargesabatteryordrivesan electricmotor.Inthiscase,thermalenergyisthustransformedintokineticenergy, thenintoelectricalenergy,andthenintokineticenergy.

Ifthecombustionengineisnotused,butonlythebatteryandtheelectricmotor, storedelectricalenergyisconvertedintokineticenergy.

Forthedesignofthevehicle’ssystemcomponents,thequestionnowarisesasto whichlossesoccurduringtheseconversions.Theseareinfluencedbythetechnical realization.

Exercise2.3 Wewanttodesignapowertrainofanhybridvehicle.Twodifferentsetsof components, A,B,areavailableforthecombustionengine,theelectricmotor,andthebattery. Thecomponentshavedifferentefficiencies.

InTab. 2.2 theefficienciesareshown.Themostefficientsystemconfigurationisnowto bechosenforthedesign.Itshouldbetakenintoaccountthattheshareofutilizationofthe combustionengineandtheelectricdrivecanbedifferent.Forthispurpose,theweighting factor α shallbeused,whosevaluerangeliesbetween 0 and 1 α =1 correspondstothesole useofthecombustionengine.If α =0,thevehicleisdrivenexclusivelyelectrically.

Solution: Thetotalefficiencyistheweightedsumoftheindividualefficiencies: η

where i =(A,B) istherespectiveconfiguration.InFig. 2.2 theefficiencycurvesforthetwo configurationswithdifferentweightsisshown.Configuration A isbetterthanconfiguration B at α =1.Thisisnotsurprising,becauseathigh α theuseofthecombustionengine predominatesandthecombustionengine A ismoreefficientthanengine B.At α =0, however, B isbetter:heretheuseoftheelectricdrivetraindominates,andthisismore efficientat B than A.

Table2.2 Efficienciesoftheavailable vehiclecomponents.

SystemcomponentEfficiency

Combustionengine Aηcomb =43%

Combustionengine Bηcomb =39%

Electricdrive A ηdrive =74%

Electricdrive B ηdrive =81%

Fig.2.2 Efficiencyoftheconfiguration A and B asafunctionof α

2.2.3 Theinfluenceofcharginganddischargingpower

WelearnfromExercise 2.3 thattheusageofthevehiclehasanimportantinfluenceon itsdesignconsideration.Ifitisprimarilydrivenbythecombustionengine,adifferent configurationisbetterthanforthecasewherethevehiclecanbeoperatedcompletely electrically.Inavehiclethathasintegratedbothsystemcomponents,forexamplean electricpowertrainandaninternalcombustionengine,twovariablesdeterminehow muchdrivingisdoneelectricallyandhowmuchwithaninternalcombustionengine: theenergycontentofthevehiclebatteryanditscharginganddischargingcapacity.

Theenergycontentdealswiththequestionofhowmuchenergyisneededbetween twochargingprocesses.Thisis,ofcourse,followedbythequestionsofvolume,weight, andcost.Sincestoragealwaysbringsadditionaleffortandcosts,wealwaystrytomake thecapacityonlyaslargeasisreallyneeded.Inourexample,thesizeofthebattery influencestheproportionofjourneysmadewiththeelectricmotororthecombustion engine.Ifthebatteryisempty,thedriverhastorelyondrivingwiththecombustion engine.Alargebatteryisthereforeassociatedwithasmallvaluefor α.Asmallbattery meansthat α becomesone.

Thecharginganddischargingpowerindicateshowmuchenergycanbeaddedtoor removedfromthestorageinrelationtoaparticularamountoftime.Thisparameter alsohasaninfluenceonthequestionofhowlargetheshareofuseofthecombustion engineandtheelectricdriveis:ifthebatteryisdesignedinsuchawaythatitcan onlybeoperatedwithlowdischargingpower,thecombustionenginemustbeserved asasupportwhenhigheraccelerationsarerequired.Wheneverthedriver‘stepsonthe gas’,thecombustionenginewillthenprovideadditionalpowertosupporttheelectric motor.Thisofcoursehasaneffecton α,whosevaluewouldshifttowardsone.But thereisanothereffect.Anelectricmotorworksbothasamotorandasagenerator— thatis,itisabletochargethebatterybyconvertingkineticenergyintoelectrical energy.Butifthebattery’smaximumchargingpowerislimited,notallofthepower thatcouldbeservedtochargethebatteryduringabrakingmanoeuvrecanbeused. Dependingonthedesignofthevehicle,theportionthatcannotbestoredisconverted intofrictionandheatbyamechanicalbrakeorconvertedintoheatwiththehelpofa brakeresistor.Thechargingpowerthereforealsohasaninfluenceonthevalueof α Ifthechargingpowerissmall,lessbrakingenergyistransferredbackintothebattery andhastobeburned.Thisreducestheamountofpureelectricdrivingandshiftsthe valueof α towardsone.

Storagesystemsandtheirapplicationscanthereforebedescribedbythreeaspects: whichformsofenergyoccurandarestored?Howlargeistheenergycontentthatthe storagesystemmustprovidetomeettheapplication’srequirement?Whatcharging anddischargingpowerisrequiredfortheapplication?Inthefollowingsection,we willusethesethreequestionstocharacterizedifferentapplicationsofenergystorage systems.

2.3 Applicationsofenergystoragesystems

Energystoragesystemshaveaverywiderangeofapplications.Inthissectionwe lookatsomeoftheseanddescribethemusingthethreecriteriadescribedinSection 2.2:energycontent,charginganddischargingpower,andwhichtypesofenergyare

used.Westartwithmobileapplications,thenlookattheelectrificationofvehicles andmobilemachinery.Bothfieldsofapplicationarecharacterizedbythefactthat theyaremobileapplications—thatis,thestoragesystemismoved.Thenwelook attwostationaryapplications.Inthesecases,thestoragesystemisnotmovedand canthereforebesignificantlylarger.Thefirstareawedealwithisbuildings,bothin connectionwithapowergridandasacomponentofaself-sufficientenergysupply. Thelastareadealswiththepossibilityofusingenergystoragetosupportthepower grid.

2.3.1 Mobileapplications

Inthissectionwelookattheuseofstorageformobileapplications,andmorespecificallyconsumerelectronics,tools,andgardeningequipment.Attheendofthetwentieth century,theenergyandpowerdensitiesofprimaryandsecondaryenergystoragedevicesbecamesohighthatitwaspossibletoequipdevicesthatpreviouslyhadtobe connectedtoapowergridwithbatteriesaswell.Toolsthatcouldpreviouslybeserved withacablehavenowbecomecordless.Cordlessdrillsandcordlessscrewdriversare examplesofthis.

Atthesametime,themarketformobileconsumerelectronicsdeveloped.Laptops andmobileswereconstantlydevelopedfurtherandbecametechnologydriversforthe increaseofenergyandpowerdensityofenergystoragedevices.Theusecaseisalways aspatialandtemporalshiftintheusageofenergy.Wechargeourmobilesovernight athometobereachableanywhere,anytime,duringthedayviaemail,phone,online messenger,tobeabletowatchkittyvideosanytimeandanywhere,ortobeableto listentoourfavouritesongfromourrecordcollectionorplaylist.Thestorageinthe laptopischargedinthelibraryordockingstationtobeservedinalectureortransit fromoneworkplacetoanother.Thankstocordlesstechnology,itisnowpossibleto servetheelectricscrewdriverinplaceswithoutapowersocket.Andanyonewhohas tomowalawnwithlotsoftreesandshrubsplustablesandpaddlingpoolsappreciates nothavingtofusswithacordorconstantlyrefillthefuel.

Ifwewanttodevelopanenergystoragesystemforamobiledevice,wehavetofind asolutionfortheconflictingproductrequirementsofportability,priceandoperating time,anddurability.Thesmallertheenergystoragesystem,thehighertheportability ofthedevice.Volumeandweightincreaseiftheenergycontentincreases.Anincrease intheavailablepoweralsoincreasesthevolumeandweight.Althoughthetechnical reasonsaredifferent,thesameappliestotheprice.Themoreenergyorpoweristobe available,thehighertheprice.

Operatingtimeandservicelifeareinfluencedbythechoiceofstoragetechnology. Butwiththesamestoragetechnology,theinfluencingvariablesareessentiallyreduced tothecapacityoftheenergystoragesystem.Thelargerthecapacity,thelongerthe unitcanbeoperatedforbeforeitneedstoberecharged.Thisalsoextendstheservice life,asittakeslongerforausertobecomeawareofanage-relatedreductioninstorage capacity.Buttheincreaseinstoragecapacitygoeshandinhandwithanincreasein costandvolume.Thismeansthatwehavetwocontradictoryrequirementsthatmust beweighedagainsteachotherappropriately.

Fig.2.3 Energyandpowerrequirementsofvariousmobileapplications.

Thediversityofusecasesisalsoreflectedintherequirementsforenergycontent andpowerdemand.InFig. 2.3,theseareshownfortheapplicationsmentionedabove. Inthisfigurethepowerandtheenergydemandareshownforthedifferentapplications. Notethattheaxisisonalogarithmicscale:thisallowsabettercomparisonbetween applicationswherethedifferenceinenergyandpowerdemandismorethanoneorder ofmagnitude.

Theapplicationswiththehighestpowerrequirementsarethemobiletools.Cordless screwdriversanddrillsrequirepowerrangingfrom 750W to 2000W.However,this powerisnotappliedpermanently.Ascrewdriveronlyneedsthepowerforashorttime, duringtheinsertionorremovalofthescrew.Thisprocesscanbebetween2and 30s dependingonthelengthofthescrew,thenatureofthepartbeingassembled,andthe skilloftheuser.

Exercise2.4 Acordlessscrewdriverhasastorageof 5 4Wh.Forscrewingorunscrewing screws,apowerof 100W isrequiredfor 2s.Inordertoassembleawallshelf, 25 screwsneed tobescrewed.Howmanywallshelvescanbeassembledwiththescrewdriverifnomistakes aremade?

Solution: Theenergycontentofascrewdrivingoperationis

100W · 2s=200Ws= 200Ws1h 3,600s =0 05Wh

Lawn mower

Cordless screwdriver

Cordless drill

Thus,withoutrecharging,thefullychargedscrewdrivercandriveapproximately N = 5 4Wh 0 05Wh =108 screws.Thiswouldbeenoughforaboutfourwallshelvesinarow.

Inthecaseofthedrillandthescrewdriver,thepowerrequirementnaturallydependsverymuchonthespecificapplication.Ittakesdifferentamountsoftimeto screwinascrewthatis10cmlong,dependingonwhetherthematerialissoftorhard. Hence,thepowerrequirementisdifferent.However,itisessentialinthisapplication thattheloadisnotpermanentlyapplied.Bothdevicesaredesignedforworkwhichis regularlyinterrupted,allowingtheelectronicsandbatteriestocooldown.

Forthebattery-poweredlawnmower,thepowerrangeoftheenergystoragesystem isbetween20and 1,600W andtheavailablestorageis20–160Wh.Thelawnmower isanapplicationhavingacontinuousoperationwithasteadydischarge.Thepower requirementdependsontheenvironmentalconditions.Wet,tallgrassdemandsmore powerfromthelawnmowerthanshort,drygrass.Thisisalsoareasonwhyrobotic lawnmowersmowthelawneverydayandnotjustonceaweek.Thepeakperformance ofalownmowerisveryrarelyrequested.

Theenergyandpowerrangecoveredbylaptopbatteriesoverlapswiththelower rangeofthelawnmower.Thisisnotsurprising,becauseoftennotonlythesamestorage technologyisused,butalsothesamecomponents:lithiumionbatteriesusinground cellsofthe16850type(seeSection 8.4).Theelectronicsmarketreliesheavilyontheuse ofcomponentsthatareinstalledinhighquantitiesindifferentdevices,whichmeans thattheenergystoragesystemsfordifferenttypesoflaptopsareverysimilartoeach otherintheirtechnicalproperties.Thesamecanbeobservedwithmobilephones. Thedatasheetsoflaptopbatteriesshowthesamevoltagerangeandthesameelectro chemistry.Theadvantageisthatthecostsforanenergystoragesystemarereduced duetothehighernumberofunitsandlowerproductdiversity.

Forthelaptop,theenergycontentisbetween 45Wh and 75Wh.Here,too,wehave tofindacompromisebetweenvolume,weight,operatingtime,andprice.Theoperating timedependsontheuseofthelaptop.PlayingaCDorcontinuouslydownloadingfiles requiresabout 18W.Ifthelaptopisusedfor3Dgamingornumericalsimulations, thepowerdemandvariesfrom 21W to 30W (MahesriandVardhan,2004).

Thepictureformobilephonesissimilartothatforlaptops.However,theenergy contentandpowerdemandisconsiderablylower.Theavailablecapacityis 4Wh to 13Wh.Thepowerdemandis 0.4W to 1W (Carroll etal.,2010; Ardito etal.,2013; Tawalbeh etal.,2016).

Mobilephonesareatleastonstandbyallofthetime,toassurethattheycanreceive callsandtheusercanbeinformedaboutthelatestinformationfromtheinternetatin anytimeandinanyplace.Thismeansthattheenergystoragesystemiscontinuously discharged.Sincethesizeandvolumeofamobilephoneislimited,alotofdevelopment workhasbeenputintoreducingthepowerdemandandincreasingtheenergydensity ofthebattery.

Thepurposeofenergystoragesystems

Energystorageapplicationscanbedividedintotwocategories:energyapplications andpowerapplications.Themobilephoneandthelaptopareenergyapplications— thatis,theirstorageisservedtoprovideenergyoveralongperiodoftime.The screwdriverisapowerapplication:itsstorageisusedtocalluphighpowerforashort time.Therefore,itdoesnotcontinuouslymakelow-powerrequests,butinsteadhas intermittenthighpowerdemands.

The2DdivisionofapplicationsintoenergydemandandpowerdemandinFig. 2.3 unfortunatelydoesnotallowthesetwoapplicationstobeeasilydistinguishedbetween. Characterizationisnotsosimpleatfirst.ThisiswheretheE-Ratehelpsusbyallowing ustodifferentiatebetweenenergyapplicationsandpowerapplications.

TheE-Rateistheratioofthepowerdemandandtheavailablestoragecapacityof anapplication.TheseratesareshowninFig. 2.4 below.E-Ratesaboveonearereferred toaspowerapplications;forexample,heretheenergystoragesystemservestoprovide power.E-Ratesbelowone,ontheotherhand,arereferredtoasenergyapplications; forexample,herethestorageservestoprovideasmuchenergyaspossibleoveralong periodoftime.

TheE-RatesshowninFig. 2.4 confirmthepreviousobservations.Mobilephones andlaptopsarebasicallyenergyapplications.Thepowerdemandisreducedsothat theenergystoragesystemcanprovideitsenergyoveralongperiodoftime.Cordless screwdriversandcordlessdrillsarepowerapplications.Highpowerisrequiredover ashortperiodoftimeinrelationtotheenergycontent.Lawnmowersrepresentan applicationthatliesbetweenthesetwoareas.Therearelawnmowersthataredesigned forlowpoweroveralongperiodoftimeandthereareproductsthatcanalsoprovide peakpowerintermittently.WhatissurprisinghereistherangeofvaluesoftheERates.Shouldonewishtopurchasealawnmower,Fig.2.4teachesusthatwemust lookverycarefullyatwhichE-Ratethelawnmowerprovides.Otherwise,wemaybuy itforapowerapplication,butfindthatinsteadwehaveanenergyapplication.Inthis case,wewillneedtoplanformanychargingbreakswhilemowingthelawn.

2.3.2 E-Mobilityandmobilemachinery

Inthissectionwelookattheapplicationofenergystoragesystemsforvehiclesand mobilemachines.Similartomobiledevices,inthesesystemsenergyischargedinto storagetobeconsumedatanotherlocation.Mobilityisfocusedonusingtheenergy togetfromoneplacetoanother.Withmobilemachines,thereisalsotheaspectof work.Mobilemachinesnotonlyservetogetfromoneplacetoanother,butalsoneed todoajobonthespot.

Westartourinvestigationswithvehicleswhoseapplicationistotransportpeople orgoods.

Therearevariouspossibilitiesforpoweringavehicle.Thesearebasicallyderived fromtheformsofenergyandtheirtransmissionthatwehavepresentedinFig. 2.1:to driveavehicle,electricalenergyorthermalenergyistransformedintokineticenergy. Ifwewanttouseelectricalenergy,weuseanelectricmotorthatdrawsitsenergy fromabatteryorafuelcell,forexample.Ifwewanttousethermalenergy,we useacombustionengine.Inbothcases,theenergyistransferredtoapowertrain.

Fig.2.4 E-Ratesfordifferentmobileapplications.

Therearefourwaystocombinethesetechnologies.InFig. 2.5,wehaveillustrated these.Historically,A),theconversionofthermalenergyintokineticenergywasthe firstformofmobility.Originally,thiswasrealizedbysteamengines.Today,internal combustionenginespoweredbyfossilfuelareacommonoccurrence.Thedisadvantage ofthistechnologyisthatkineticenergycannotbeconvertedbackintothermalenergy. Theenergyflowalwaysgoesinonedirectiononly.Ifthespeedistobereduced,then brakesmustbeapplied.Thisalsoreleasesthermalenergy,butthisenergyislostand isnotreturnedtothefueltank.

InapproachB),anelectricpowertrainisused.Thisconsistsofanelectricalenergysource,anenergystoragesystem,andanelectricmotor.Theadvantageofthis approachisthatmechanicalenergycanbeconvertedbackintoelectricalenergy.Ifa storageunitisavailable,itisdischargedduringtheaccelerationphaseandcharged duringthebrakingphase.Thisprocessiscalledrecuperation.

Unfortunately,electricalenergystoragesystemshavenotyetreachedtheenergy densityoffossilfuels.Petrolhasanenergydensityof 8 8kWh/l,whereasalithiumion batteryhasanenergydensityof 0 4kWh/l.However,theefficienciesarealsodifferent. Theconversionofpetrolintokineticenergyviaaninternalcombustionenginehasan averagedefficiencyofabout η =30%.Apurelyelectricpowertrain,ontheotherhand, hasanaveragedefficiencyof η =85%.

Fig.2.5 Overviewofdifferentpowertrainconceptsofvehicles.A)correspondstothedrive withtheaidofaninternalcombustionengine.B)isafullelectricdrive.C)andD)representhybriddriveconcepts.InC)bothdrivescanpowerthevehicleseparately.InD)the combustionenginegenerateselectricalenergy,whichisservedbyanelectricmotorforthe drive.

Exercise2.5 Thestorageofavehicleistobedesignedsothatitcanconvert κ =400kWh kineticenergy.Howmuchvolumeisrequiredfortheenergystoragesystemifpetrolwith anenergydensityof ρV =8 8kWh/l oralithiumionbatterywithanenergydensityof ρV =0 4kWh/l isused?Theefficiencyofthecombustionengineis η =30%,andthatofthe electricdriveis η =85%.Recuperation,i.e.thepossibilityofstoringkineticenergyagain,is nottobeconsideredinthistask.

Solution: Thevolumeisgivenbytheformula

= κ η · ρV

Thetargetcapacity κ iscorrectedbytheefficiency.Asaresult,ifthedriveislessefficient, thestoragemustbelarger.

Ifpetrolisservedastheenergysource,weneedavolumeof:

V = 400kWh 30% · 8 8kWh/l =151l.

Inthecaseofalithiumionbattery,thevolumeis:

V = 400kWh 85% 0.4kWh/l =1,176l.

Thelithiumionbatteryneeds10timesasmuchvolumeforthesameenergycontent.

Butbecareful!Incontrasttotheinternalcombustionengine,alithiumionbatterycan storebrakingenergy,i.e.therangeofthevehiclewouldbeconsiderablygreater,asthe storageunitwouldonlyhavetocompensateforthebrakingandfrictionlossesthatoccur whiledriving.

ThecalculationinExercise 2.5 showsthattheenergystoragesystemwithfossil fuelstakesupsignificantlylessvolumethananelectricalenergystoragesystem.For thisreason,mixedformshavealsobecomeestablishedinpractice.Thesewanttoensure alongrangebyusingthecombustionengine,butatthesametimeoffertheadvantage ofrecuperationbyintegratinganelectricdrive.ConceptC)inFig. 2.5 representsa hybriddriveinwhichbothelectricalenergyandthermalenergyareservedforthe drive.

InconceptD),incontrast,theinternalcombustionengineservestogenerateelectricalenergy.Thebasicideaisthatthecombustionengineisoperatedattheoptimal operatingpointsothattheefficiencyisimproved.Diesel-poweredlocomotiveswork withthisconcept.Recuperationisnotprovidedforinthisconcept,unlessthereisstill abatteryontheelectricpowertrain.

Whenconsideringtheenergyrequirementsofavehicle,itmustbetakeninto accountthatthedischargeisneededfortheaccelerationphase.Duringtravel,onthe otherhand,onlyfrictionneedstobecompensated.Ifitispossibletostorekinetic energyduringabrakingprocess,thiscanleadtoaconsiderableincreaseinrange.

Exercise2.6 Onevehiclehasaninternalcombustionengineandanotherhasafullelectric drive.Theelectricvehiclehasastoragecapacityof κ =40kWh.Thevehiclewiththe combustionenginehasatankwithacapacityof 30l.Thefuelusedispetrolwithanenergy densityof ρV =8 8kWh/l.Bothvehicleshavethesamemass, m =1,500kg

Thevehicleistoaccelerateto 50 km h withinoneminuteandthendrivestraightahead for10min,requiringanaveragepowerof 500W tocompensateforfrictionlosses.Thisis followedbyfullbraking,whichlastshalfaminute.

Howmanyofthesedrivingcyclescanbedrivenwiththecombustionengineandhowmany withtheelectricdrive?Forsimplicity,weassumethatthemassofthevehicleisindependent ofthefillinglevelofthetank.Furthermore,weassumethatrecuperationhasanefficiencyof ηEV =90%.Thecombustionenginehasanefficiencyof ηICE =30%.

Solution: Ataspeedof v =50 km h ,thekineticenergyis:

,699 1J=40 18Wh=0 0402kWh

Thepurposeofenergystoragesystems

Duringtravel,frictionlossesof Ploss =500W mustbecompensated.Theenergyrequired forthisisgivenby: Eloss = t=T t=0 Plossdt = Ploss · T =500W 10min =5,000Wmin=0.083kWh.

Sincetheinternalcombustionenginevehiclecannotrecoverenergyduringbraking,we candeterminethenumberofpossibledrivingcyclesbasedonthisdata.Theenergycontent ofthetankis:

Thenumberofdrivingcyclesthenresultsin:

N = κICE Ekin + Eloss = 79kWh 0 0402kWh+0 083kWh =641 23 ≈ 641

Inthecaseoftheelectricvehicle,energyisrecoveredduringthebrakingprocess.This energyis:

Erekub = Ekin ηEV =0.0402kWh 90%=0.036kWh.

Theenergydemandfor N cyclesis

EN = Ekin +(N 1) Ekin (1 ηEV)+ NEloss

Thenumberofcyclesisobtained(with EN = κEV)from:

N = κEV ηEVEkin (Ekin (1 ηEV )+ Eloss ) = 20kWh 90% 0.0402kWh (0.0402kWh 10%+0.083kWh) =459.249 ≈ 459.

Althoughtheelectricvehiclehasabout50%lessstoragecapacity,itsrangeisabout71%of therangeoftheinternalcombustionengine.

Thesizeoftheenergystorageandthecharginganddischargingcapacityvaries greatlydependingonthetypeofvehicle.InFig. 2.6 theenergycontentandpower levelareshownfordifferentvehicles.Thepeakpowerwasusedforthepowerdemand. Peakpowerreferstothemaximumpowerdraw.Note,thatthepeakpowercannotbe drawnpermanently.Thisisbecausethecomponentsofthestorageunitorthedrive trainarenotdesignedforacontinuousloadofthispowerrate.

AscanbeseeninFig. 2.6,thediagrambreaksdownintotwoareas.Belowapower of 5,000W areapplicationswithsmallorlightvehicles:roller,scooters,andbicycles withelectricauxiliarydrive.Abovethislimitarecars.

ThepowerandenergyrangeofeScooters,eBikes,andeRollersisinthesamerange asthatofthelawnmowerfromFig. 2.3.Thisisbecausethetechnicalcomponents

Fig.2.6 Energycontentsandpowerlevelofvehicleapplications.Incaseswherebothfossilandelectricalenergystoragewereused,theelectricalenergystoragewasalsoentered separately.

aresimilar.Forexample,thesametypeofbatterycellsareusedforthestoragetechnology.Thereasonforthisisthattherequirementsintermsofvolume,price,and weightarecomparable.

eScootersandeBikesaretypicallynotusedforlong-distancetravel.Thedriving time—ifnotrackingtoursareundertaken—isintherangeofminutesorhours.Strictly speaking,bothvehiclesarehybriddrivesystems.Whiletheydonotuseacombustion enginethatservesfossilfuels,theydousehumanmusclepower.

Thehighestpowerdemandoccurswhenavehicleisstartingup.Here,inaddition torollingfriction,staticfrictionmustalsobeovercomeandthemassofthevehicle andloadmustbeacceleratedtoatargetspeed.WitheScootersandeBikes,therider helpswiththeirmusclepower.Duringtheride,thestoredenergyonlyservestocompensateforfrictionlosses.Thedischargerateisconsiderablylowerandisadditionally compensatedbytheassistanceoftherider.Therefore,eScootersandeBikesaremore ofanenergyapplicationthanapowerapplication.

WithaneScooter,thesecondenergysourceisomitted.eScootersarenothybrid driveapplications.Here,theentirepowerisdrawnfromtheelectricstorageunit.As canbeseeninFig. 2.6,theenergycontentbutalsothepowerdemandofthesevehicles isgreaterthanthatofeBikes.

Aboveapowerof 10kW arethepassengercars.Apartfromvehiclespoweredby aninternalcombustionenginealone,therearefourcategoriesintowhichcarswith alternativedrivesaredivided:electricvehicle,mildhybrid,plug-inhybrid,andfull hybrid.

Thepurposeofenergystoragesystems

TheelectricvehiclecorrespondstoapproachB)inFig. 2.5.Anenergystorage systemstoreselectricalenergy,whichthensuppliesanelectricmotor.Asshownin Fig. 2.6,thedifferentpowerclassesofelectriccarscoverarelativelylargeenergyand powerdemand.Theuseofanelectricpowertrainwithanelectricstoragesystemallows recuperation—thatis,thereturnofkineticenergyintoelectricalenergyforbraking thevehicle.Thismechanismhasapositiveeffectontherangethatcanbeachieved bythesevehicles.

ThemildhybridrealizestheconceptC)inFig. 2.5.Thepowertraincanbedriven byboththecombustionengineandtheelectricstorage(Fig. 2.6:‘Mildhybrid(el. storage)’).Thestoragecapacityis 300Wh–1500Wh,whichislowcomparedtoan electricvehiclewithastoragecapacityof 10Wh–100kWh.However,theavailable powerof 10kW to 20kW isinthelowerpowerrangeofanelectricvehicle.Itistherefore apowerapplication.Thesmallstorageunitofthemildhybridservesforshort-term charginganddischarging.Here,theapplicationistosupportthecombustionengine whenstartingandtorecuperatekineticenergywhenbraking.

Likeallvehicleswithaninternalcombustionengine,mildhybridsalsocarryanother energystoragesystem:thetankfortheirfossilfuel.Thepowerandenergycontent ofthecombustionenginearealsoshowninFig. 2.6 (‘Mildhybrid(fossilstorage)’. Sinceinamildhybridthemajorityofthepropulsionpowerandenergyconsumption isprovidedbythecombustionengine,thestoragecapacityandthepowerthatcanbe calledupareintheupperrangeofthisfigure.

Plug-inandfullhybridsalsorealizeconceptC),butbothhaveahigherelectrical storagecapacityandelectricalpower.Theyareinasimilarpowerrangetothatofthe electricvehicle,at 100kW to 250kW.However,thestoragecapacityofafullhybridis significantlylower,with 1kWh to 2kWh.Thestorageofbothvehiclesislargeenough toallowpurelyelectricdriving.Duetothelargerstorage,thisoperationislongerfor aplug-inhybridthanforafullhybrid.Inbothtypesofvehicle,theelectricstorageis alsousedtoreducetheloadonthecombustionengineindrivingconditionsinwhich itisnotworkingefficiently.

Fig. 2.7 showstheE-Ratesinthemobilityapplicationarea.eScootersandeBikes areintheboundaryareabetweenenergyapplicationandpowerapplication.This cannotbeexplainedbythetypeofapplicationalone,becausegreaterpowerisonly neededwhenstartingup.Here,itismorethecostpressurethatcomesintoplay.The storageisdesignedtobesosmallthatitismoreofapowerapplication.

Inthecaseofcars,electricvehicles,mildhybrids,andplug-inhybridsallfallinto thecategoryofpowerapplication,ifoneconsiderstheelectricalstoragesystemalone. Thefossilfuelpowertrain,ontheotherhand,isconsideredanenergyapplication.Fossil fuelshaveahigherenergydensity—thatis,moreenergycanbetransportedinavehicle tank.Theeffectisthatthestoragetankislargerinrelationtotherequiredpower. Thiseffectisveryclearinthemildhybridandthefullhybridvehicle.Bothsystems arecharacterizedbyarelativelysmallbattery—thatis,thetankcanbedesignedto becorrespondinglylarger.Withtheplug-inhybrid,whichhasalargerbattery,the tankissomewhatsmaller,andtheE-Rateshiftsinthedirectionofpowerapplication.

Sofar,wehaveonlylookedatvehiclesthatareessentiallytransportingpeople. NoneofthevehiclesdescribedinFig. 2.7 areconsideredworkingmachines.Onlythe

Fig.2.7 E-Ratesfordifferentmobilityapplications.

transportofweeklyshoppingorholidayluggageisaworkingapplicationforthese vehicles.Furthermore,theyarenotdesignedforcontinuousoperation.Apassenger carisdesignedforaservicelifeof10to20years.Itisassumedthatthesevehiclesare simplystationarymostofthetime,andneithertheirstoragenorthedrivetrainare usedduringparking.Thisassumptioncanbeeasilyunderstood.Workingcommuters drivetoworkinthemorning,thenworkonsitewithoutusingthecar,andthendrive homeagain.Inthisexample,thecarisnotusedformorethanabouttwotofour hours.

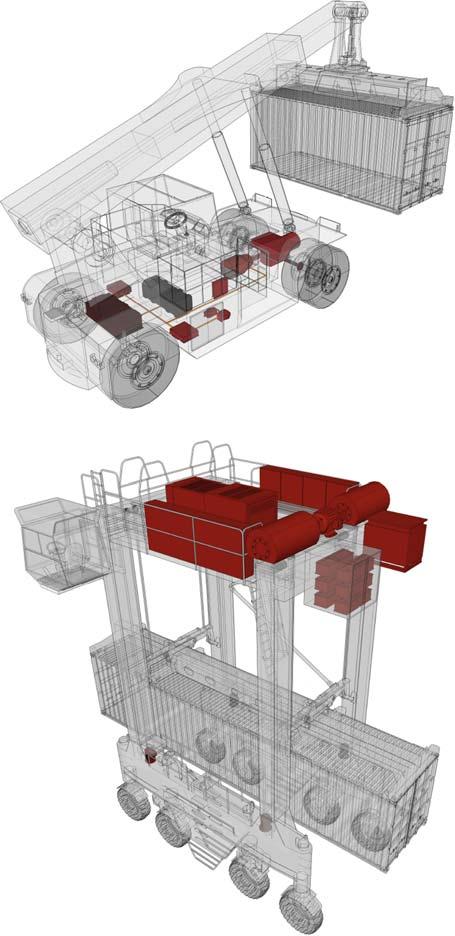

Thesituationiscompletelydifferentwhenvehiclesareusedtoperformwork.Vehiclesandtheircomponentsareusedmoreintensivelyandcontinuously.Mobilemachinesalsodifferfromthemobilityapplicationsmentionedsofar,inthatthevehicles arenotonlyusedfortransportation,butalsoforperformingwork.InFig. 2.8,two examplesareshown.Oneisareachstackerandtheotherisastraddlecarrier.Both vehiclesareservedinportstotransportcontainersfromoneplacetoanother.Both vehicleshaveenginesthatareusedtomovethemandtheyhavecomponentsthatserve tolifttheloads.Duringtheliftingprocess,kineticenergyisconvertedintopotential energy.

Areachstackercanbasicallyusethesamedrivesfortraction—thatis,movement fromAtoB—asareusedinmobility.Aswithcars,however,internalcombustion enginesdominatehere.Forlifting,lowering,andpickinguploads,ahydraulicdrive trainisoftenusedhere.Ahydraulicsystemconsistsofapumpthatbuildsupveryhigh pressureinafluid.Oilsthatcanabsorbthispressurewellareusedforthispurpose. Thispressurizedfluidisstoredinatank.Soherewehaveaconversionofkineticenergy (thepump)intopotentialenergy(thecompressedliquidthatwantstoexpandagain).

Fig.2.8 Twoexamplesofelectrifiedmobileworkingmachines:areachstacker(top)anda straddlecarrier(bottom).Bothvehiclesareisusedtotransportcontainers.Theyhavean electricdrivetrain(markedinred)thatisusedtomovethevehiclefromAtoB.Thereach staggerusesanhydraulicsystemtolifttheloads,whilethestraddlecarrierusesanelectrical motortoliftthecontainer.(Source:REFUdrive)

Applicationsofenergystoragesystems 21

Toraiseandlower,youopenavalve,andyouusethepressureoftheliquidtomove acylinder.Thestoredpotentialenergyisconvertedbackintokineticenergy.

Justaswithtraction,thepumpcanbeoperatedpurelyelectricallyorbyaninternalcombustionengine(Immonen etal.,2013; Immonen etal.,2016; Zhang etal., 2019).Fortheefficiencyassessmentofthisdrivetrain,differentefficiencieshavetobe considered:ontheonehand,wemustlookattheefficiencyofthepumpdrive.This iscomparabletotheefficiencyofadrivetrain.Inaddition,thereistheefficiencyof thepump,whichturnskineticenergyintopotentialenergy.Theefficiencyisabout ηpump =80%.Thevalveandhosesystemalsogeneratelosses.Theefficiencyhereis ηvalve,hose =55% (Immonen etal.,2016).

Exercise2.7 Acommercialvehicleistobeprovidedwitheitherahydraulicoranall-electric powertrain.Thehydraulicdrivelineispoweredbyaninternalcombustionenginewitha 100l tank.Theelectricpowertrainisequippedwithastoragecapacityof 250kWh.Theefficiencies ofthedriveinverterandtheelectricmotorare,respectively, ηinverter =96% and ηmotor =86%. Whatistheusablekineticenergythatcanbeextractedfromeachofthetwodrivetrains?

Solution: Theelectricpowertrainhasanoverallefficiencyof:

Thisgivesausablekineticenergyof: Ekin. = ηel.powertrain · 250kWh=206 25kWh

Forthehydraulicpowertrain,thetotalefficiencyequals:

825

Theusablekineticenergyistherefore: Ekin = ηhydraulicpowertrain 100l 8 8 kWh l =116 16kWh

Exercise 2.7 showsthathydraulicpowertrainshavealoweroverallefficiencycomparedtoelectricpowertrains.Therefore,thereareeffortstopartiallyorfullyelectrify thesepowertrains(Immonen etal.,2013; Ponomarev etal.,2015; Zhang etal.,2019). Althoughhydraulicpowertrainshavelowefficiency,fullyelectrifiedmobilemachinesarenotcommon.Purediesel-poweredanddiesel–electricvehiclesdominate.In Fig. 2.9 below,theenergiesandpowerofmobilemachinesareshown.Inthecaseof hybridmachines,theusableenergyhasbeenshown:wehavenotshowntheenergy contentofthedieselhere,buthavealreadyincludedtheefficienciesofthedrivemotor, pump,andvalvesystem:

MachineswithpurecombustionenginesarenotshowninFig. 2.9.Sincethemachines ofthesevehiclesdonotdifferindesignfromthoseofthediesel–electricmachines,the