ListofAbbreviations

AAPSSAnnalsoftheAmericanAcademyofPoliticalandSocialScience

ADHIAdministory:ZeitschriftfürVerwaltungsgeschichte

ADÖAußenpolitischeDokumentederRepublikÖsterreich

AdPDWArchivderBundespolizeidirektionWien

AdRArchivderRepublik

AfÖGArchivfürösterreichischeGeschichte

AfSArchivfürSozialgeschichte

AHRAmericanHistoricalReview

AHYAustrianHistoryYearbook

AOKArmee-Oberkommando

AÖRArchivdesöffentlichenRechts

APSRAmericanPoliticalScienceReview

ArZArbeiterinnen-Zeitung

ASAustrianStudies

ASSPArchivfürSozialwissenschaftundSozialpolitik

AVAAllgemeinesVerwaltungsarchiv

AZArbeiter-Zeitung

BoBohemia

BDFABritishDocumentsonForeignAffairs

BGBlBundesgesetzblatt

BJILBerkeleyJournalofInternationalLaw

BMfaABundesministeriumfürauswärtigeAngelegenheiten

BRGÖBeiträgezurRechtsgeschichteÖsterreichs

CASContemporaryAustrianStudies

CBCorrespondenzblattfürdenkatholischenClerusOesterreichs

CDChristlicheDemokratie

CECentralEurope

CEHCentralEuropeanHistory

CJHCanadianJournalofHistory

CPKChristlichsozialerParlamentsklub

CPWChristlichsozialePartei,Wien

CSChristianSocials

CSAZChristlich-sozialeArbeiter-Zeitung

CSPCanadianSlavonicPapers

CVCartellverband

DFDokumentedesFortschritts

DGDemokratieundGeschichte

DGFPDocumentsonGermanForeignPolicy,1918–1945

DHDiplomaticHistory

DNRMDerDonauraum

DÖLZDeutsch-österreichischeLehrer-Zeitung

DÖWDokumentationsarchivdesÖsterreichischenWiderstandes

DRDeutscheRundschau

DReDeutscheRevue

DVDeutschesVolksblatt

DVjsDeutscheVierteljahrsschriftfürLiteraturwissenschaftund Geistesgeschichte

DZDeutscheZeitung

EACEuropeanAdvisoryCommission

ECEEastCentralEurope

EcHREconomicHistoryReview

EEQEastEuropeanQuarterly

EHQEuropeanHistoryQuarterly

EHREnglishHistoricalReview

ERHEuropeanReviewofHistory

ERPEuropeanRecoveryProgram

Eur.J.Int.LawEuropeanJournalofInternationalLaw

Eur.Rev.Econ.Hist.EuropeanReviewofEconomicHistory

FFortschritt

FAFinanz-Archiv

FBFremdenblatt

fl. florin

FMFinanzministerium

FPÖFreiheitlicheParteiÖsterreichs

FRUSForeignRelationsoftheUnitedStates

GGGeschichteundGesellschaft

GHGermanHistory

GLLGermanLifeandLetters

GSRGermanStudiesReview

GuGGeschichteundGegenwart

GVGrazerVolksblatt

HEIHistoryofEconomicIdeas

HEPHigherEducationPolicy

HGSHolocaustandGenocideStudies

HHRHungarianHistoricalReview

HHSAHaus-,Hof-undStaatsarchiv

HJHistoricalJournal

HJbHistorischesJahrbuch

HMHistoryandMemory

HMtmHistoricalMaterialism

HSRHistoricalSocialResearch

HTHistoryandTheory

HZHistorischeZeitschrift

HUSHarvardUkrainianStudies

IAInternationalAffairs

IHRInternationalHistoryReview

IOInternationalOrganization

JbKGJahrbuchfürKommunikationsgeschichte

JbVGStWJahrbuchdesVereinsfürdieGeschichtederStadtWien

JCHJournalofContemporaryHistory

JCWSJournalofColdWarStudies

JEHLJournalonEuropeanHistoryofLaw

JfGJahrbuchfürGeschichte

JfZJahrbuchfürZeitgeschichte

JGPÖJahrbuchfürdieGeschichtedesProtestantismusinÖsterreich

JGVVJahrbuchfürGesetzgebung,VerwaltungundVolkswirtschaftim DeutschenReich

JLNJahrbuchfürLandeskundevonNiederösterreich

JMEHJournalofModernEuropeanHistory

JMHJournalofModernHistory

JMIHJournalofMilitaryHistory

JNSJahrbücherfürNationalökonomieundStatistik

JÖLGJahrbuchderÖsterreichischenLeo-Gesellschaft

JÖRJahrbuchdesöffentlichenRechtsderGegenwart

JPJournalofPolitics

JRPJournalfürRechtspolitik

JRSJournalofRomanStudies

JSHJournalofSocialHistory

JSSJournalofStrategicStudies

JVJuristischeVierteljahresschrift

JZJüdischeZeitung

KDerKampf

KAKriegsarchiv

k.k.kaiserlich-königlich

KPÖKommunistischeParteiÖsterreichs

KVZKonstitutionelleVorstadt-Zeitung

LBYLeoBaeckYearbook

LVLinzerVolksblatt

MCUMinisteriumfürCultusundUnterricht

MdIMinisteriumdesInnern

MIHModernIntellectualHistory

MIÖGMitteilungendesInstitutsfürÖsterreichischeGeschichtsforschung

MJPSMidwestJournalofPoliticalScience

MKFFMilitärkanzleidesGeneralinspektorsdergesamtenbewaffneten

Macht(FranzFerdinand)

MKSMMilitärkanzleiSeinerMajestätdesKaisers

MLRModernLanguageReview

MÖStAMitteilungendesÖsterreichischenStaatsarchivs

MPMorgen-Post

MQRMichiganQuarterlyReview

MSLMitteilungendesSteiermärkischenLandesarchivs

NFPNeueFreiePresse

NLNachlass

NöBNeueösterreichischeBiographie

NÖLANiederösterreichischesLandesarchiv

NPNationalitiesPapers

NPANeuesPolitischesArchiv

NSDAPNationalsozialistischeDeutscheArbeiterpartei

NWJNeuesWienerJournal

NWTNeuesWienerTagblatt

ÖAWÖsterreichischeAkademiederWissenschaften

ÖGBÖsterreichischerGewerkschaftsbund

ÖFZÖsterreichischeFrauen-Zeitung

ÖGLÖsterreichinGeschichteundLiteratur

ÖMHÖsterreichischeMonatshefte

ÖOHÖsterreichischeOsthefte

ÖPZErziehungundUnterricht:ÖsterreichischepädagogischeZeitschrift

ÖRÖsterreichischeRundschau

Oxf.ArtJ.OxfordArtJournal

OxREPOxfordReviewofEconomicPolicy

ÖSÖsterreichischeStatistik

ÖSBZÖsterreichischeStaatsbeamten-Zeitung

ÖVPÖsterreichischeVolkspartei

ÖVZÖsterreichischeVolkszeitung

ÖWÖsterreichischeWochenschrift

ÖZGWÖsterreichischeZeitschriftfürGeschichtswissenschaften

ÖZPÖsterreichischeZeitschriftfürPolitikwissenschaft

PAPolitischesArchiv

PAAAPolitischesArchivdesAuswärtigenAmtes(Berlin)

PERParliaments,EstatesandRepresentation

PJPädagogischerJahresbericht

PLPesterLloyd

PNVStenographischeProtokolleüberdieSitzungenderProvisorischen Nationalversammlung

PPPastandPresent

PrDiePresse

PROPublicRecordOffice

PSQPoliticalScienceQuarterly

PTPragerTagblatt

PVSPolitischeVierteljahresschrift

RAHReviewsinAmericanHistory

RGBlReichsgesetzblatt

RHMRömischeHistorischeMitteilungen

RMReichsmark

RpReichspost

RPReviewofPolitics

SAQSouthAtlanticQuarterly

SDSicherheitsdienst

SdZStimmenderZeit

SEERSlavonicandEastEuropeanReview

SGBlStaatsgesetzblatt

SHPSStudiesinHistoryandPhilosophyofBiologicalandBiomedical Sciences

S:I.M.O.NShoah:Intervention.Methods.Documentation

SiPoSicherheitspolizei

SLRSlavicReview

SMStatistischeMonatsschrift

SOFSüdost-Forschungen

SP(upto1918)StenographischeProtokolleüberdieSitzungendesHausesder Abgeordneten

SP(from1920)StenographischeProtokolleüberdieSitzungendesNationalrates

SPDSozialdemokratischeParteiDeutschlands

SPHStenographischeProtokolleüberdieSitzungendesHerrenhauses

SPKNVStenographischeProtokolleüberdieSitzungender

KonstituierendenNationalversammlung

SPÖSozialdemokratischeParteiÖsterreichs

SRSocialResearch

SRTStaatsrat

SSSchutzstaffel

StředStřed./Centre:JournalforInterdisciplinaryStudiesofCentral Europeinthe19thand20thCenturies

SüASüdostdeutschesArchiv

TAJdGTelAviverJahrbuchfürdeutscheGeschichte

ThPQTheologisch-praktischeQuartalschrift

TRHSTransactionsoftheRoyalHistoricalSociety

UNRRAUnitedNationsReliefandRehabilitationAdministration

UTQUniversityofTorontoQuarterly

VVaterland

VdUVerbandderUnabhängigen

VfSWVierteljahrschriftfürSozial-undWirtschaftsgeschichte

VGABVereinfürGeschichtederArbeiterbewegung

VjZVierteljahrsheftefürZeitgeschichte

VWVolkswohl

VWschrVolkswirtschaftlicheWochenschrift

WDBWienerDiözesanblatt

WEPWestEuropeanPolitics

WGBWienerGeschichtsblätter

WiHWarinHistory

WPWorldPolitics

WPBWienerPolitischeBlätter

WSJWienerSlavistischesJahrbuch

WSLAWienerStadt-undLandesarchiv

WSMZWienerSonn-undMontagszeitung

WWWortundWahrheit

ZDieZeit

ZfGWZeitschriftfürGeschichtswissenschaft

ZfOZeitschriftfürOstmitteleuropa-Forschung

ZfPZeitschriftfürPolitik

ZGZeitgeschichte

ZHFZeitschriftfürHistorischeForschung

ZHVSZeitschriftdesHistorischenVereinesfürSteiermark

ZNRZeitschriftfürNeuereRechtsgeschichte

ZOFZeitschriftfürOstforschung

ZÖRZeitschriftfürdasPrivat-undöffentlicheRechtderGegenwart

ZöRZeitschriftfürÖffentlichesRecht

ZRGZeitschriftderSavigny-StiftungfürRechtsgeschichte

ZVSVZeitschriftfürVolkswirtschaft,SozialpolitikundVerwaltung

TheTermsofAustrianHistory

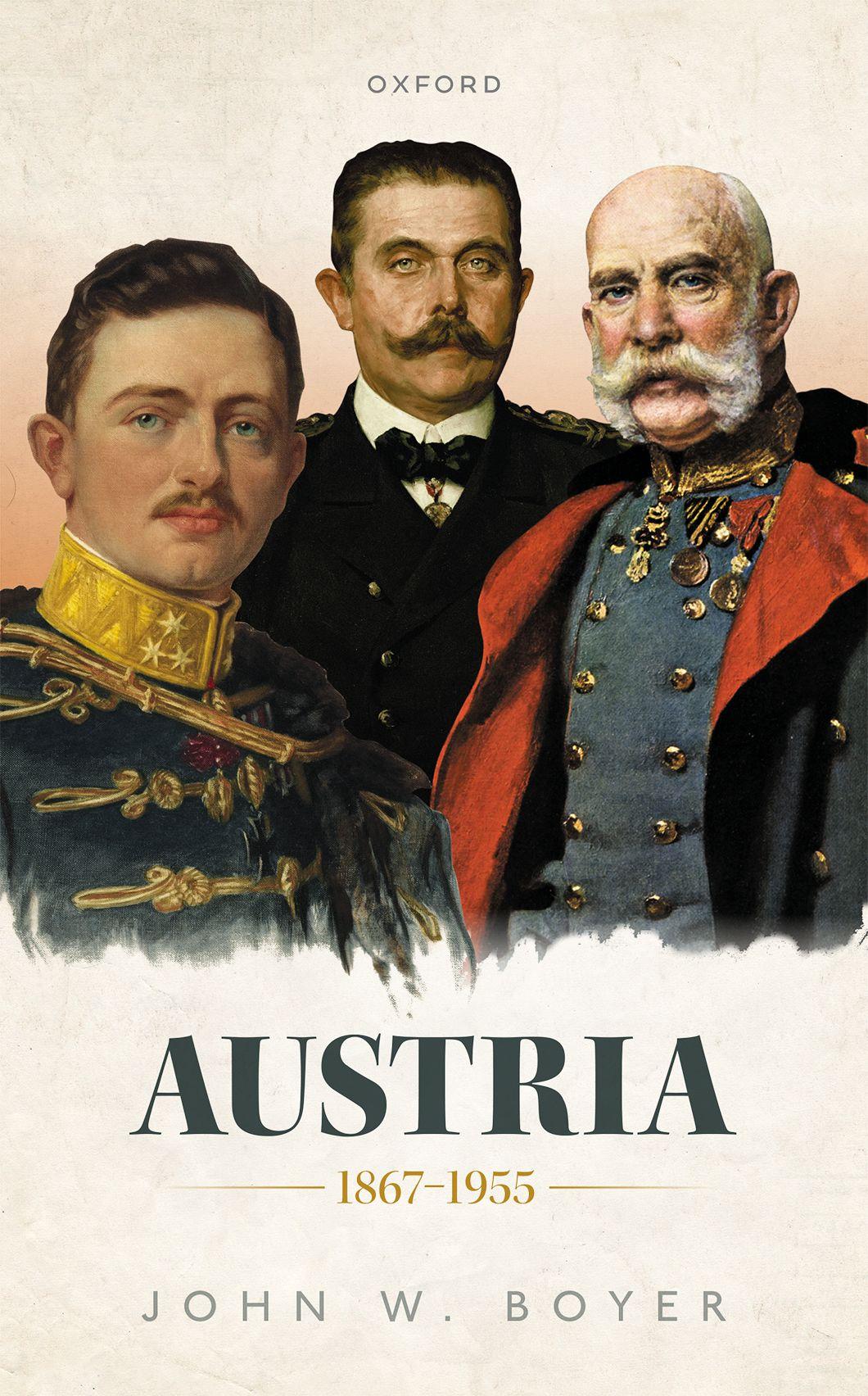

Tobeaskedtocontributethisparticularvolumetothe OxfordHistoryofModern Europe serieswasachallengingassignment,forasLordAlanBullockof St.Catherine’sCollege,OxfordUniversity,observedtotheauthorwhenheissued theinvitationtowritethisbook,theframeworkdependedontheall-important question:whatisAustria?AsBullocktrenchantlyputit,doesonede fi ne Austriafrom1848forward,orfrom1955backward?Giventhatthisbookisa workofselectivesynthesisgroundedin multipleinterpretiveframeworks,it seemedplausibletohonortheoriginalcommissionfromBullock,whowanteda bookthatwouldprovideapoliticalandinstitutionalhistoryofAustriafor thecenturybetween1867and1955,withAu striaexplicitlyreferringtothe German-speakinglandsoftheformerEmpireandespeciallyVienna,buttoset thatstorywithinthecrucibleofdynastic,administrative,andparliamentary institutionsinthegeneralstateandimperialsystem.Hence,thisbooktreats Austriabothasamajorconstitutiveter ritorialelementoftheone-timemultinationalEmpireandasaresoluteand(fromtheperspectiveofthedecadessince 1955)remarkablysuccessfulnationalRepublic,withmanyrupturesandevident disastersconnectingthetworealms.ItwasthuscrucialinAlanBullock ’ smind thatthisbookwouldlinkthecivicwo rldbefore1914withthatwhichcame after1918.Thislinkageisespeciallyim portantnotonlybecausepresent-day Austriaistheresultofacontinuumofin stitutionaltraditionsandpolitical practicesthatpredatethedualwatershedofWorldWarIandtheRevolution of1918,butbecausetheAustriancaseisrelativelyuniqueinthewider landscapeofEuropeinposingthechalle ngeofcreatingandsustainingaliberal andthenaliberal-democraticRechtsstaatinthefaceofbothextremeethnicracialandintensesocial-ideologicaldisharmoniesandcon fl icts.Whenthe youngAustro-Marxisttheoristswroteinthe fi rstissueof DerKampf in1907 that,amongtheirEuropeansocialist compatriots,theyalonehadthetask of “ translatingtheideaofinternationalismintolivingreality, ” whichmade themthe “ constitutionaljuristsoftheInternational, ” theywerealludingto thisdoublecommissionofreconcilin glegalequitywith unyieldingclass andethnicidentities,whilepushingfo rwardstructuresofdemocraticaccess Austria,1867–1955.JohnW.Boyer,OxfordUniversityPress.©JohnW.Boyer2022. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198221296.003.0001

andopportunity.¹Thiswouldbecomethepreeminentandclassicstruggle confrontingtheAustrianstateitselfinthetwentiethcentury.

Thepresentbookhasbeenlongingestationandreflectsmanynewprimary andsecondarysourcesandcompetingperspectivesinvolvingthewiderhistoryof theEmpireandtheRepublic,butitdoesfocusonthestate-levelpoliticsand administrationinandaroundViennaaskeyelementsofitsnarrative.Thehistory ofsmallAustriaafter1918,emergingaspartoflargeAustriabefore1914,mustbe framedinlightofthemanytensionsbetweenempireandnationhoodthat emergedoverthecourseofthenineteenthcentury.Inrecentyearsmanyscholars havetakenupthesetensionsafreshwithnewcontributionsaboutthewaysin whichtheHabsburgEmpirewasde finedbyethnic/nationalregionsthatdepended ontheEmpire’sterritorialunityfortheirrelativeeconomicwell-being,butwith thoseregionsalsogivingbirthtonationalistandpopulistconstituenciesthat, paradoxically,broughttheEmpiretoitskneesin1918.²Inacontributiontothe longstandingdebateaboutthenatureandscopeoftheAustrianpastArno Strohmeyerhaswiselyobservedthat “thereisno ‘single’ Austrianhistoryatthe presenttime,butratherthishistoryhastobeseenfromtheperspectiveofan ensembleofdifferentspatialnarratives,witheachitsowndevelopmentallogicas toitsoriginsandevolution.”³MaciejJanowskihasarguedthattheHabsburg Crownhadaproteancharacter,withtheEmpireasabundleofnormativelegal principlesseekingterritoriallegitimationinaspecialtimeandplace.Theimperial modeloflegitimation finallyadopted stressingdiversityandmulti-ethnicity wasasplausibleasthenation-statemodel,whenviewedfromthestartingpointof thenineteenthcentury.⁴ ThisinterpretationstandsincontrasttothatofIvan Berend,whoviewseastCentralEuropeasmarkedbybackwardness,laggardness,a crisiszonedominatedbyperipheralconcerns,andmanifestinganeastCentral EuropeanSonderweg,barelyabletoachieveparitywithWesternEuropeand Germany.⁵

ThehistoryoftheEmpireinthelaternineteenthandearlytwentiethcenturies presentsaparticularlychallengingassignmentforanyhistorian,sincethemodels

¹ K,1(1907–8):3–4.ForthedualmeaningofAustriaasthetraditional(andlargelyGermanspeaking) “Erblande” ontheonehandandthewholeoftheEmpireontheother,seetheclassicaccount ofR.J.W.Evans, TheMakingoftheHabsburgMonarchy1550–1700:AnInterpretation (Oxford,1979), pp.157–94.

²FocusingonPieterJudson’soutstandinginterpretivehistoryoftheEmpire,publishedin2016,see LaurenceCole, “VisionsandRevisionsofEmpire:ReflectionsonaNewHistoryoftheHabsburg Monarchy,” AHY,49(2018):261–80.

³ArnoStrohmeyer, “‘Österreichische’ GeschichtederNeuzeitalsmultiperspektivische Raumgeschichte:einVersuch,” inMartinScheutzandArnoStrohmeyer,eds, Washeißt “österreichische” Geschichte?Probleme,PerspektivenundRäumederNeuzeitforschung (Innsbruck, 2008),p.185.

⁴ MaciejJanowski, “JustifyingPoliticalPowerin19thCenturyEurope:TheHabsburgMonarchy andBeyond,” inAlexeiMillerandAlfredJ.Rieber,eds, ImperialRule (Budapest,2004),pp.78–80.

⁵ IvanT.Berend, TheCrisisZoneofEurope:AnInterpretationofEast-CentralEuropeanHistoryin theFirstHalfoftheTwentiethCentury (Cambridge,1986),pp.1–21.

associatedwithclassicnation-statehistorydonoteasilyapply.Conventional narrativesthatascribeaSettembrini-likearcofnationalunity,economicprogress, andrationalenlightenmentwithinaslowlyemergentliberalstateinthenineteenthcenturydonoteasilyresonate,becausethemostpopulousandwealthiest regionsoftheEmpirebetween1867and1914weremarkedbyincreasing levelsofbothdemocraticparticipationandilliberalnationalistpartisanship. Instead,otherwaysofimaginingtheunityandthedistinctivenessoftheEmpire havetobearticulatedthatacknowledge itspolitical-ethnicheterogeneity, powerfulregionalisttraditions,anddivergentstylesofreligiousobservance, aswellastheunifyingforceofitscentr aladministrativeapparatusandofits manyinterconnectednetworksofnon-stateeconomicandsocialinstitutions. ⁶ Habsburghistoriographythusbecomesahomewithmanydifferentrooms, somedecoratedinethnic/nationalcolors,butothersdefi nedbystunning regional/localandideologicalhues,withmanydifferentcross-cuttingand connectingpassageways.

TobeginahistoryofAustrialiterallyin1867wouldneglectahostof fascinatingtransformationsthatsetthestageforwhatcameafter,soitiswell toconsidersomepreliminariesinvolvingthereceivedinstitutionalforebearsof themodernAustrianstateanditshistoriographictraditions,aswellassome re fl ectionsontheroleoftheprincipaldynastandtheCourtwhoseextraordinary claimstosupremeauthorityshapedthehistoryofthewholeofthenineteenth andthe fi rsttwodecadesofthetwentiethcentury.Thesethreedomains the administrativestate,its fi nessedandoftencalculatedhistory,andtheselfidentityofitsprimarypoliticalarchitect arenecessaryareasofinquiryfor comprehendingtherupturesandsurprisingcontinuitiesde fi ningthescopeof thisbookandforexplainingwhyAustrianhistorydoesnot fi teasilywithin conventionalhistoricalbookendsandwhyitdoesnotmirrorthemodelsofother majorEuropeannations.

⁶ See,forexample,AndreaKomlosy, “ImperialCohesion,Nation-Building,andRegional IntegrationintheHabsburgMonarchy,1804‒1918,” inStefanBergerandAlexeiMiller,eds, NationalizingEmpires (Budapest,2015),pp.369–427;FranzLeanderFillafer, “Imperiumoder Kulturstaat?DieHabsburgermonarchieunddieHistorisierungderNationalkulturenim19. Jahrhundert,” inPhilippTher,ed., KulturpolitikundTheater:DiekontinentalenImperieninEuropa imVergleich (Vienna,2012),pp.23–53;BálintVarga, “WritingImperialHistoryintheAgeofHigh Nationalism:ImperialHistoriansontheFringesoftheHabsburgMonarchy,” ERH,24(2017):80–95; PeterBecker, “StolpersteineaufdemWegzumkooperativenImperium:BürokratischePraxis, gesellschaftlicheErwartungenundsozialpolitischeStrategien,” inJanaOsterkamp,ed., Kooperatives Imperium:PolitischeZusammenarbeitinderspätenHabsburgermonarchie (Göttingen,2018), pp.23–53;PeterBecker, “DerStaat:EineösterreichischeGeschichte?,” MIÖG,126(2018):317–40; FredrikLindström, “TheStateandBureaucracyasaKeyFieldofResearchinHabsburgStudies,” in FranzAdlgasserandFredrikLindström,eds, TheHabsburgCivilServiceandBeyond:Bureaucracyand CivilServantsfromtheVormärztotheInter-WarYears (Vienna,2019),pp.13–47;andJohnDeak, “TheGreatWarandtheForgottenRealm:TheHabsburgMonarchyandtheFirstWorldWar,” JMH, 86(2014):336–80.

Myvantagepointhereisneither1867nor1955,butrathertheadministrative, legal, fiscal,andreligious-institutionaltemporalitiesandsystemsthatthe Monarchysetinplaceinthemid-tolateeighteenthcentury,whichgenerated structuraldynamicsthatwouldoutlivetheEmpireandinfluencetheSecond Republic.Thecreationofauniversal,enlightenedMonarchycomplicatedthe categoriesandprocessesofstateformationthatweseeelsewhereinnineteenthcenturyEurope neutralizingsomeconflictswhileexacerbatingothers and presupposedakindofnon-nationalcitizenshipthatwasanchoredinan a-nationalbureaucracyandtheethnic-spatialdiversityoftheEmpireitself.The eighteenth-centuryMonarchyalsoestablishedapre-existingdialecticofheterogeneity,centralization,andregionalparticularismsthatshapedthestoryofthe modernAustrianpastafter1867.

TheideaofAustriaasa “compositemonarchy” asarticulatedrecentlyby WilliamGodsey,KarinSchneider,AndreaKomlosy,JanaOsterkamp,andothers acknowledgesthattheEmpireprovidedalegalanddynasticframeworkforahost ofvenerableregionalcommunities,practicingstylesoflocalelite-drivenpolitics thatoverthecourseofthenineteenthcenturywereredefinedinmorepopulistand national-ethnicmodes.⁷ Theregionaldietsandtheiradministrativeelitesplayeda significantroleafter1861inthisrecalibrationoflocalaristocraticpoliticalprivilegeintonational-ethnicpopulisms.The “nation” ceasedtobeaneutralcorporatistvesselofadministrativeandculturalhegemonydefinedbythelandowning Estates,asitwasunderstoodinthemid-eighteenthcentury,andbecameinsteada collectivitydefinedbyethnicidentitiesarticulatedwithinspeci ficregionsand basedaboveallonthepoliticsoflanguageuse.Incontrasttotheethnicneutralism ofAmericanfederalism,whereIllinoiswasnotaPolishstateandWisconsinnota Germanstate,Austrianfederalismoverthecourseofthenineteenthcenturywas definedbytheassumptionthatone’stownorcityorevenruralGemeindewas envelopedinaregionallyarticulatedethnicidentity,anditwaspreciselyinthe cases(suchasBohemia)wherecompetingregionalnationalidentitieshadtoshare thesameterritorialspacesthatthemostfrictionstookplace.

IfthenineteenthcenturyinEuropeanhistorywasacenturyofstrongadministrativeandeventuallyconstitutionallyorganizedstates,itwasalsothesiteof nationsviewedasobjectsandsubjects,processesandends,mythsandrealities. Thenewnationsofthenineteenthcenturydeployedpatternsofcollectivememory andcollectedhistories,arrayedonbehalfofpublicassociationsbasedonthe

⁷ WilliamD.Godsey, TheSinewsofHabsburgPower. LowerAustriainaFiscal-MilitaryState 1650–1820 (Oxford,2018),pp.16,378,392,396;KarinSchneider, “TheAustrianEmpireasa CompositeMonarchyafter1815,” inMichaelBroersandAmbrogioA.Caiani,eds, AHistoryofthe EuropeanRestorations (2vols,London,2019),1:147–55;JanaOsterkamp, Vielfaltordnen:Dasföderale EuropaderHabsburgermonarchie(Vormärzbis1918) (Göttingen,2020),pp.8–18.

imputationofacommonpast,theavailabilityofcommonlanguage,andthe invocationofcommoncivicsentiments.Manyscholarshavelikenedthese nationalsentimentstoquasi-religiousallegiances,andcertainlynationalism’ s emotiveforceanditsdependenceoncollectiveperformance,culticritual,and officialhistorysharedmanyofthesameoperationalfeaturesasmostnineteenthcenturyreligions.Feelingsofattachmenttothesenewlyimaginedorre-imagined publicassociationsbecameapowerfulcomponentofcivicidentityformationin mostEuropeanstatesafter1848andespeciallyafter1870,althoughtheprocesses bywhichnationsascommunitiesofidentityandmemoryandstatesassitesfor theadministrativeexerciseoflegitimatelegalcoercioncametocohabitthesame civicspaceweredistinctiveacrosstheEuropeancontinent.

InmostinstancesinWesternandCentralEuropethenewliberaladministrativestatesandnewnationalcommunitiesconvergedandbecamecoherentcivic organisms.Forexample,towriteGermanhistoryinthelaternineteenthcenturyis towriteahistoryofacentral,elite-sponsorednationalcultureslowlyimposed overamyriadofregionalandlocalculturaldistinctionsthatwasboundedbya newstateadministrativeapparatusafter1871.AsAlonConfinohasargued, “the unificationof1871...joiningtheGermannation,Germansociety,andaGerman statewithinasingleterritory,redefinedthespatialandhistoricaldimensionsof thenation.”⁸ Ultimatelythetwonarratives stateandnation overlappedand Germany’shegemonicreligion,acuriouscombinationofLutheranandCalvinist Protestantism,playedapowerfulroleincementingthetwotogether.AsHelmut WalserSmithhasbrilliantlyinsisted,GermanProtestantismhelpedtoprovidethe foundingcivicideologyofthe1871Reich.⁹

TherelationshipofnationsandnationhoodtostateandcivicculturefunctionedverydifferentlyinAustria.Inanextraordinary,butnowlittleremembered comparativeessayonAustrianandPrussianbureaucracyintheeighteenthcentury,OttoHintzeremarkedthatAustria’shistoricchallengeingovernancewas “muchmoresevere” thanthatofitsPrussianneighborandoftentimesrival.¹⁰ WhereasPrussia’schallengewastouniteagroupofnorthernandwestern Germanterritoriesofdifferentsocialandeconomicconditionsintoaunified state,butbasedonacommonethnic-nationalidentity,Austriawasforcedto constructastatebasedonradicallydifferenteconomicandculturalregionsthat wereinhabitedbyverydistinctnationalities,andtodosoinawaythatwould acknowledgethehistoric, “universalpower ” oftheHabsburgdynasty.Thus,

⁸ AlonConfino, “FederalismandtheHeimatIdeainImperialGermany,” inMaikenUmbach,ed., GermanFederalism:Past,Present,Future (NewYork,2002),p.76.

⁹ HelmutWalserSmith, GermanNationalismandReligiousConflict:Culture,Ideology,Politics, 1870–1914 (Princeton,1995),pp.19–78;aswellasRudolfLill, “Großdeutschundkleindeutschim SpannungsfeldderKonfessionen,” inAntonRauscher,ed., ProblemedesKonfessionalismusin Deutschlandseit1800 (Paderborn,1984),pp.43–7.

¹

⁰ OttoHintze, “DerösterreichischeundderpreußischeBeamtenstaatim17.und18.Jahrhundert. EinevergleichendeBetrachtung,” HZ,86(1901):410–44,esp.403,439–41.

Austrianhistoryencompassedbothadiversesetofregions,withsturdycorporate andethnicidentities,butalsopowerfultraditionalwavesofimperialruleunder theadministrativeaegisoftheHouseofAustria.

ThelattermissionofuniversalruleinspiredtheHabsburgreformerstomake thesearchforadministrativeunity,formanagerialefficiency,andforcentralizing policycoordinationafundamentalfeatureofthepoliticallandscapeofAustriain themid-andlateeighteenthcentury.Thecentraladministrativestateasan abstractprinciple,asadogmainlaw,andasasetofinterventionist fiscal,military, andlegalpracticeswouldleadtoamorerationallyefficientsociety.¹¹Theidealof theCrown’sKammer(itsprivaterightsasapublicauthoritycomprisingthose policyagendasthatdidnothavetobeapprovedbyorconsultedwiththeEstates, suchascustoms,tolls,regalianrights,revenuefromJewsandfromChurch,and somemonopolies)wastransformedintoageneralstateinterest,withtheCrown viewingitselfasresponsibleforthepublicwealofthewholerealm,notjustits dynastichousehold,andtheroleofthedynastasoneofbureaucratizedleadership, notpatrimonialcontrol.¹²Thepenetrationofsystematicandcodifiedformsoflaw and financialregulationsbecameadynamicfeatureoftheciviclandscape,withthe publicgoodincreasinglydefinedineconomicterms.Serfdomcametobeviewed asabarriertoproductivity,leadingtoanintensepreoccupationwiththe peasantry frompeasantprotectionunderMariaTheresatomoreradicalforms ofeconomicameliorationofthepeasantryunderJosephII.TheChurchasahuge semi-privatecorporationwithdeeprootsinBaroqueconfessionalpracticeshadto submittoandadvancetherational,utilitarianwelfarefunctionsofthestateand proveitselfmoresociallyrelevanttothetimes.

Withtheriseoflargestandingarmiesengagedinintenseperiodsofconstant wartheneedemergedformoreeffectivemilitaryrequisitioning,newcategoriesof directtaxation,andnewformsofmilitaryjustice.Bythelate1740sMariaTheresa realizedthattochangetheadministrationofherrealmshehadtochangethe constitution.ThelogicoftheHaugwitzreformsof1749signaledthatthestate bureaucracy’sprimarytaskwastolookoutexclusivelyfortheCrown’sinterests, deployingageneralconceptionoflawandinterveninginlocalsocietieswith courtsandcivilservantschargedwithimplementingtheCrown’slawandusing theCrown ’sdelegatedpowersagainstlocallandedelites.¹³Officialswhoformerly

¹¹FortheemergenceofthelegalideaofaGesamtstaatintheeighteenthcentury,seeMartin P.Schennach, “Die ‘österreichischeGesamtstaatsidee’:DasVerhältniszwischen ‘Gesamtstaat’ und LändernalsGegenstandrechtshistorischerForschung,” inMartinP.Schennach,ed., Rechtshistorische AspektedesösterreichischenFöderalismus:BeiträgezurTagunganderUniversitätInnsbruckam28.und 29.November2013 (Vienna,2015),pp.1–29.

¹²PeterRauscher, “VerwaltungsgeschichteundFinanzgeschichte:EineSkizzeamBeispielderkaiserlichen Herrschaft(1526‒1740),” inMichaelHochedlingerandThomasWinkelbauer,eds, Herrschaftsverdichtung, Staatsbildung,Bürokratisierung:Verfassungs-,Verwaltungs-undBehördengeschichtederFrühenNeuzeit (Vienna,2010),pp.185–211.

¹³Thesedevelopmentshavegeneratedahugehistoricalliterature.Foraconciseintroduction,see CharlesW.Ingrao, TheHabsburgMonarchy,1618–1815 (3rdedn,Cambridge,2019).

workedfortheEstateswerenowsworninasagentsoftheCrown,becoming cameralofficialswhowereveryaggressiveinexpandingtheCrown’spowersin regulatingmarkets,planningroads,developingforestry,pursuinglocallaw enforcement,settinguniformweightsandmeasures,andprotectingpeasantsso theycouldpaymoretaxes.Before1750eachoftheseveralprovincesunderthe ruleofthearchdukesofAustriasawitselfentitledto “anindividuallawcode,with itsownordinances,customs,habits,andinthiswaysoughttosecureandpreserve theinhabitants’ distinctivewayoflife.”¹⁴ Incontrasttoachaosofrivallegalnorms andjurisdictionsbeforethe1740s,thepublicationofcollectionsoflawsinthe 1770sand1780ssignaledthattheregimeexpectedamoreefficientandinterventionistlevelofjurisprudenceandmoreequitablepatternsofenforcement.

TheeighteenthcenturyintheAustrianlandsthuscomprehendedagreat transitionfromaworldinwhichlocalandprovincialgovernments,controlled bynobleEstates,hadclaimedforthemselvespowerfulconstitutionalauthority, becausethosegovernmentsfunctionedascourtsoflawwithgreatinfluenceover judicialprocedureandpropertyrightsandbecausetheycontrolledenormous financialresources,deployingtheminwaystoensuretheirsocialindependence andtheirculturalprivileges.Theycombinedjusticeandadministration,andthey privatizedtheexerciseofwhatlaterreformerswouldclaimtobepublicpower. Oneofthemaineffortsoftheenlightenedreformerswastobreakthisdoublelink betweenadministrationandjusticeandbetweenprivate,corporaterightsandthe rightsofthesovereignking,queen,oremperor,whoactedonbehalfofan imaginedenlightenedcommonweal.Thepowerofthemodernstateasitemerged inthenineteenthcenturyhadmuchtodowithitsabilitytoseparatejusticeand law-makingfromalllevelsofadministration,butalsotoclaimlaw-makingand thepracticeofjusticeasthesoleconcernandrightofthesovereigncentral government,thuscreatinganewrealmofpubliclawthatwasinitiallysubjectto imperialorroyalprerogativebutwaseventuallycontrolledbytheliberalparliamentarystate.¹⁵ Theoriginsofconceptionsofmodernsovereignty,andeventually evenofmoderncitizenship,werethuscloselyconnectedtothepracticesof modernadministrativereformandjudicialreviewinthelateeighteenthcentury.

Inevitably,thesepolicytrendscollidedwiththecustomaryinterestof thelandedeliteswhodominatedtheAustrianregionswellintotheeighteenth century.¹⁶ Between1740and1780theregionalEstateslostmuchoftheirbusiness, witheachprovincegettingaDeputationorRepresentationtooverseemilitary

¹⁴ GreteKlingenstein, “TheMeaningsof ‘Austria’ and ‘Austrian’ intheEighteenthCentury,” in RobertOresko,G.C.Gibbs,andH.M.Scott,eds, RoyalandRepublicanSovereigntyinEarlyModern Europe:EssaysinMemoryofRagnhildHatton (Cambridge,1997),p.429.

¹⁵ FranzLeanderFillafer, Aufklärunghabsburgisch:Staatsbildung,Wissenskulturund GeschichtspolitikinZentraleuropa1750–1850 (Göttingen,2020),pp.388–400.

¹⁶ WalterDemel, “‘Revolutionenvonoben?’ Verfassungs-undVerwaltungsreformeninderZeitdes AufgeklärtenAbsolutismus,” inHochedlingerandWinkelbauer,eds, Herrschaftsverdichtung, Staatsbildung,Bürokratisierung,pp.213–28.

andtaxbusiness,independentofEstatesinterference.Newcourtsofgeneral jurisdictionunderJosephIIoperatedonthe firstandsecondlevelsofadjudication andappealandignoredständischdifferences;allcitizensbecamesubjecttothe samecriminalcode,withlocalinhabitantshavingatheoreticalrightofappeal frommanorialcourtstotheroyalcourts.Localjudgeswereforcedtoknowthe law,sinceappealstoroyalcourtswerewritten,notoral.TheregionalEstateswere nearlypowerlesstoresist theyhadnoarmy,thegreataristocratshadtorn loyalties,andtheprovincesdidnottrusteachother.

TheintellectualmilieuinwhichthereformsofMariaTheresaandJosephII tookplacewasdifferentfromthatofeighteenth-centuryFrance.TheAustrian Enlightenmentwasregulative,governmental,andsubstantiallyinfluencedby rationalistreligiousandadministrativereforms,notlikeFrance’ssecularand liberty-orientedproject.ItdidnotembraceaRepublicofLetterstypeofpolitical culture representedeitherbytherhetoricalsubversionsofthemagistratesofthe pre-1789 parlements orbytheprogrammaticdisruptionsofpublicintellectuals likeTurgotandDiderot orbysanctioningtheparticipationoffreecitizensin decentralizedpoliticalinstitutions.¹⁷ Austria’swasalateEnlightenment,influencedbyItalyasmuchasFrance,andcomingmorefromcentralgovernment servicethanthefreeprofessions,amorestate-functionalistAufklärungbasedon utilitarianreligiouspractices,amixofmercantilistandphysiocraticeconomic ideals,andnaturallawasastatistandscientificsolventtomitigatecorporatist socialprivileges.TheAustrianEnlightenment’sframeworkofnewcodesof “state sciences” wouldspawnnumerousintellectualclientsandprodigiespursuingrival schemesforliberalandconservativecivictransformationswellintothenineteenth century.¹⁸

Institutionalchangeovertheeighteenthcenturyprovokedlinguisticchangeas well.GreteKlingensteinhascarefullyanalyzedmeaningsoftheword “Austria” in thelateseventeenthandeighteenthcenturiesasitexpandedfromthearchduchies ofUpperandLowerAustriaastheterritorialbaseoftheHouseofAustriatomore generalconceptions.¹⁹ Awiderlearned,commercial,andeducationalculture reflecting “auniformandhomogeneoussociety” beyondthepatrimonialworld oftheLänderbegantoemergeinthemiddleoftheeighteenthcenturywithpeople

¹⁷“Joseph’sdeterminationtolimitpopularparticipationingovernmentwasirreconcilablewith somestrandsofEnlightenment,withtheoriginalaimsoftheFrenchRevolution,andwithnineteenthcenturyreformism.” DerekBeales, JosephII:AgainsttheWorld1780–1790 (Cambridge,2009),p.515. JoachimWhaley’srecentassertionabouttheGermanAufklärungthat “therewasnodistinction betweenintellectualsandadministrators” appliestotheAustriancaseaswell.Seehis “The Transformationofthe Aufklärung:FromtheIdeaofPowertothePowerofIdeas,” inHamishScott andBrendanSimms,eds, CulturesofPowerinEuropeduringtheLongEighteenthCentury (Cambridge, 2007),p.158.

¹

⁸ SeenowFillafer, Aufklärunghabsburgisch,esp.pp.67–76,278–302,513–24;andFranzLeander Fillafer, “DieAufklärunginderHabsburgermonarchieundihrErbe:EinForschungsüberblick,” ZHF, 40(2013):35–97.

¹

⁹ Klingenstein, “TheMeaningsof ‘Austria’ , ” pp.423–78.

using “Austrian ” asageneralculturalmarker.ImagesofAustriaasaunified territorial “state” were firstencounteredinschoolbooks,educationalmaps,and guidesfortravelersinthe1780s.Ineconomics,theworkoftheCameralists, attackinginternaltraderestrictions,necessarilyviewedthe “Monarchy” and “Austria” assomethingmorethanacollectionofterritorialEstates.Thedevelopmentandsuccessfulimpositionofnewformsofadministrativemanagementas wellastheformationofnewpan-territoriallawcodes,especiallytheJosephinist CriminalCodeof1787andtheCivilCodeof1811,werecrucialtoextendingthe word “Austrian” toincludethewholegeographicalrangeofterritories.²⁰ Thestate graduallybecameoneandthusinalienable,itsconstituentpartsindivisible. Slowly,assubjects(Untertanen)becamecitizens(Staatsbürger),theword “Austrian” cametobeappliedtothestate’scitizens.

Yetthisnewstateofenlightenedsocialdisciplineremainednameless,forthe patentofAugust11,1804issuedbyEmperorFranzIcreatingthehereditary emperorshipofAustriadidnotconstituteageneralAustrianstateinpubliclawor ingeographicalscope.RatherthepatentreferredtotheHouseofAustriaandits “independentstates” aswellas “independentkingdomsandstates ” whichwould “retainunchangedtheirprevioustitles,constitutions,rights,andconditionsfrom thistimeforward.”²¹Thus,the1804edictcreatedahereditaryAustrianemperorship,butitdidnotstipulateanewunifiedlegaldesignationforthestate,andit leftpowerfulhostagesforthefuture.²²Somescholarsbelievethatwhatsooncame tobeknownineverydayspeechastheKaisertumÖsterreichwas,conceptually andlegally,aunifiedsovereignstate,andnotmerelyacollectionofunruly particularisticunitsboundtogetherbythesentimentandself-reflectionsofthe dynast.Othersviewitasmorefragile,andasa “monarchicalunionofcorporative states” (OttoBrunner)andthusasanabstractensemblemoreinlegalimagination thaninconstitutionalreality.²³Butthestate’sfunctionalsurvivalwasmortgaged toitshistoricidentities,andsincethoseidentitiesweremultiple,Franzwas understandablycautiousabouttheprecisenatureofthemonarchicalunionasit wasreflectedinhistitleofEmperor.Geopoliticalpressuresalsoinfluenced

²⁰ Ibid.,pp.450–1,460,465.

²¹EdmundBernatzik, DieösterreichischenVerfassungsgesetzemitErläuterungen (2ndedn,Vienna, 1911),pp.49–52;IgnazBeidtel, GeschichtederösterreichischenStaatsverwaltung,1740–1848 (2vols, Innsbruck,1896–8),2:70–3.

²²SeeKarinSchneider, “Zwischen ‘MonarchischerUnionvonStändestaaten’ undGesamtstaat:Die Habsburgermonarchieim18.und19.Jahrhundert,” inSchennach,ed., RechtshistorischeAspektedes österreichischenFöderalismus,pp.36–42.FriedrichvonGentzcalledthedecisiononecharacterizedby thecreationofa “namenloseErbärmlichkeit.” AugustFournier, GentzundCobenzl:Geschichteder österreichischenDiplomatieindenJahren1801–1805.NachneuenQuellen (Vienna,1880),pp.128–9.

²³SeeOttoBrunner, “StaatundGesellschaftimvormärzlichenÖsterreichimSpiegelvonI.Beidtels GeschichtederösterreichischenStaatsverwaltung1740-1848,” inWernerConze,ed., Staatund GesellschaftimdeutschenVormärz1815–1848 (3rdedn,Stuttgart,1978),pp.50–2;OttoBrunner, “Das HausÖsterreichunddieDonaumonarchie,” SOF,14(1955):126–7;andThomasWinkelbauer, “SeparationandSymbiosis:TheHabsburgMonarchyandtheEmpireintheSeventeenthCentury,” in R.J.W.EvansandPeterH.Wilson,eds, TheHolyRomanEmpire,1495–1806 (Leiden,2012),pp.167–83.

Habsburgstate-makingfor,asKarlvonAretinandothershaveargued,by1800 AustriawasfarmoreinterestedinthehereditaryErbländerthaninthehistoric Reichitself,whichmeantslowdisengagementwiththeEuropeanWest,andthat thismoreeasternorientationwasasteppingoffpointforAustria’sinternational roleinthenineteenthcentury.²⁴

ThetheoriesguidingthepracticeofJosephinism administrativeabsolutism definedbyenlightenedideals,andtheCrown’sauthoritarian,anti-Estatesstrategy seekingtoimposeuniformityandutilityincivilsociety createdlong-termnotions ofanefficientandequitablestatewhichwerecongenialwithlaterAustro-German liberalideals.AsFranzFillaferhasnoted,memoriesofJosephinismbecameakind ofmarkertoseparateliberalsfromconservativesacrossthe firsthalfofthenineteenthcentury,basedonJosephII’spopularimageasamonarchfor(although certainlynotby)thepeople,eventhoughhisprogressivelegacywasmuchmore complexandtheEmperorhimselfhardlyliberalinrespectingtheideaofcitizen rightstorepresentation.Moreover,Joseph’semphasisonstatecontrolofChurch (Staatskirchentum)mightappealtomodernizingconservatives.²⁵ Incontrastto otherEuropeanstates,inAustriatheideaofacommoncitizenshipunderthe same,rationallawwasnotaweaponofanemergingBürgertumseekingrights againstanauthoritarianstate,butratheradevicecreatedbyJosephinistadministrativeelitesthemselvestoattackcorporatistprivileges.²⁶ Theheritageofthe Josephinisteighteenthcenturyforthenineteenthcenturymightbeseenfromthe vantagepointof1848ashavinginfusedciviclifewithanensembleofnaturalrights, protectedbytheoriesofnaturallaw,inwhichpeasants,reformistpriests,and Germanizingcivilservantswillinglyalliedwithanddependedonthemodernist Crowntoprotecttheirnewlyimaginedrightsagainstoldercorporatistprivileges;or itmightbeseenashavingcreatedaninterventionistandwhollybureaucraticstate (Obrigkeitsstaat)inwhichthevoices,will,andtraditionalculturalpracticesofthe citizenrywerefundamentallyignored,ifnottacitlysilenced.²⁷ Eitherway,a

²⁴ KarlOtmarFreiherrvonAretin, HeiligesRömischesReich1776–1806.Reichsverfassungund Staatssouveränität (2vols,Wiesbaden,1967),1:332–3,506;KarlOtmarFreiherrvonAretin, Das AlteReich1648–1806 (4vols,Stuttgart,1993-2000),1:57–8;2:296–8,468;3:179,299,508–12.Foran excellentoverviewofAustria’srelationstotheoldEmpirebetween1804and1806,seePeterH.Wilson, “BolsteringthePrestigeoftheHabsburgs:TheEndoftheHolyRomanEmpirein1806,” IHR,28 (2006):709–36.

²⁵ Fillafer, Aufklärunghabsburgisch,pp.489–92.

²⁶ HanneloreBurger, “ZumBegriffderösterreichischenStaatsbürgerschaft:VomJosephinischen GesetzbuchzumStaatsgrundgesetzüberdieallgemeinenRechtederStaatsbürger,” inThomasAngerer, BirgittaBader-Zaar,andMargareteGrandner,eds, GeschichteundRecht:FestschriftfürGeraldStourzh zum70.Geburtstag (Vienna,1999),pp.216–17.

²

⁷ FranzLeanderFillafer, “RivalisierendeAufklärungen:DieKontinuitätundHistorisierungdes josephinischenReformabsolutismusinderHabsburgermonarchie,” inWolfgangHardtwig,ed., Die AufklärungundihreWeltwirkung (Göttingen,2010),pp.123–68,esp.140–2;FranzLeanderFillafer, “HabsburgLiberalismsandtheEnlightenmentPast,1790‒1848,” inMichaelFreeden,Javier Fernández-Sebastián,andJörnLeonhard,eds, InSearchofEuropeanLiberalisms:Concepts, Languages,Ideologies (NewYork,2019),pp.44,52.

powerfulandoftenrigidcentralbureaucracy,intrudinguponandregulatingall sectorsofpubliclife,wastheresult.Conservativesseekingtooverturntheruleof whattheydeemedtobeanoppressivecentralbureaucracymightstylizethemselves as “liberal,” eventhoughtheydeploredthesecularculturalnormsandsemiegalitariansocialideasespousedbytheoriginalJosephinistsofthe1780s.

Theevolutionofthisnewinterventioniststateafter1800wasandremains contested.BecauseJosephII’sradicalismcameearlyandoverreached,theEmpire notonlylackedleadersintheaftermathoftheFrenchRevolutionlikeBaronvom SteinandKarlAugustvonHardenberg,butitsharedfewofthepowerfulinstitutionalreformimpulsesinthe1810sthatPrussiacametoenjoy.Austriafounditself throughoutthenineteenthcenturyslowlytryingtobuildoutamodernadministrativestatebyconstrainingnationalprerogativesandsuppressingcollectivistregional loyalties,modesofliberalthoughtwhichmostotherEuropeanstatescoulddeployin supportoftheirconstitutionalprojects.²⁸ InViktorBibl’sclassicview,theVormärz Austrianstatewastheagentandsymbolofgratuitousrepressionanddeliberate non-action,inthefaceofsignificantsocialandeconomicchange,withtheEmpire losingfortyyearsofhistory.²⁹ Morerecenthistorianshavehadamoregenerous view,arguingthattheregimewasneitherascallousandcapriciousnorasinefficient aspreviouslyargued.³⁰ Eitherway,thelackofinstitutionalmovement,theaura offecklesscensorshipandpettyregulations,andthefailuresinpublic financial accountabilityanditsfailuretodealwithunemployment,poverty,andsocialunrest werestunning,andbythe1840sthesenseofaregimedriftingalonginareactive fashionwasoverwhelmingonthepartofeducatedcontemporaries.

Forthosewhoresentedthemanytentaclesofthecentralizedbureaucracy,this wasaregimethat fluctuatedbetweenovertrepressionandsubtleoppression,one thatstifledallmanifestationsoflocalpoliticalwill;andjustbelowthesurfaceofits forcedadministrativeequanimitythereemergedmanycomplaininganddiscordantvoices.Oneofthemostprominentlociforthisdisgruntlementwasthe regionalEstates,whowerepermittedtomeetregularlyduringthereignof JosephIIandhissuccessorsafter1790.Olderscholarshipbysuchscholarsas ViktorBiblandKarlHugelmannandmorerecentinterventionsbyWilliam Godsey,RalphMelville,andFranzLeanderFillaferhaveraisedtheprofileof theseregionalinstitutions.³¹Godsey’sworkhasbeenparticularlyimportantin

²⁸ Hintze, “DerösterreichischeundderpreußischeBeamtenstaat,” pp.403,439–44.

²⁹ ViktorBibl, DieniederösterreichischenStändeimVormärz (Vienna,1911),pp.24–40,andpassim; ViktorBibl, Metternich:DerDämonÖsterreichs (4thedn,Leipzig,1941).Biblgratuitiouslycompared theVormärzwiththeCatholicStändestaat: “dasDollfuß-Schuschnigg-System,dasebendas Metternich-SysteminReinkulturwar” (p.14).

³⁰ AlanSked, MetternichandAustria:AnEvaluation (NewYork,2008);WolframSiemann, Metternich:StrategistandVisionary (Cambridge,Mass.,2019),pp.1–19,518–67,682–715,746–55.

³¹Godsey, TheSinewsofHabsburgPower:LowerAustriainaFiscal-MilitaryState1650–1820, pp.213–357;WilliamD.Godsey, “HabsburgGovernmentandIntermediaryAuthorityunderJosephII (1780–1790):TheEstatesofLowerAustriainComparativePerspective,” CEH,46(2014):699–740; Fillafer, Aufklärunghabsburgisch,pp.30–9.

recallingthesurvivalofpowerfulprovincial fiscalandlogisticalcapacities(loansto theCrown,creditsecurityforemergencygovernmentalexpenditures)thatgave theseprovincialinstitutionsaresiduallevelofauthorityandpublicrespect.

Givenstructuraldifferencesinlandowningpatternsandtheinconsistentsupportforagrarianemancipation thenoblelandownersofLowerAustriawerein favorofurbarialreformsandtheabolitionofpatrimonialsubjectionfortheir peasants,whereastheirBohemianandMoraviancounterpartsweremuchmore skeptical atavisticdisagreementsamongthearistocracyabouttheproperlimits ofsocialandconstitutionalreformwerealwaysevident.³²Howeverresentfulthey mightbeofMetternich ’sautocracy,manyoftheregionalEstatesbefore1848 resistedliberalconstitutionalrevisions,andinBohemiaegotisticforcescoalesced againstallowingbürgerlichstrataaseriousroleincorporatistgovernance.³³Asthe historianAntonSpringerwouldlaterobserveabouttheself-indulgentprotestsof theBohemianEstatesinthe1840s, “morethanoncethemeetingsoftheEstates offeredtheiropponentsconvenientgroundsastotheirrelevanceofthewhole institution.”³⁴ AsMelvillehasnoted,thefactthatlocalaristocratsmightpatronize Czechnationalculturalformsbynomeansmeantthattheywerewillingto supportliberalpoliticalrights,muchlessdemocraticemancipation.Inthissense onemightarguethatständischinstitutionsbythelate1840sweredesolately irrelevant.³⁵

MoreplausiblecurrentsforchangewereevidentinLowerAustriaandinVienna. TheposterboyforprovincialreforminLowerAustriainthelater1840swasBaron ViktorAndrian-Werburgasarticulatedinhistractson Österreichunddessen Zukunft from1843and1847.³⁶ InfluencedbyTocqueville’ s Democracyin America andearlyGermanliberaltheoriesofconstitutionalrepresentation, Andrian-Werburg’sblendofanti-bureaucraticreformwasrootedinEstatesliberties andadmirationforthearistocracy,buthedidadvocateseriousconcessionsto bürgerlichstratawhomightattainvoiceandvoteintheEstates,aswellasfreedom ofthepress,genuineautonomyforlocalgovernment,andmoretransparentmodes ofjudicialreview.³⁷

³²SeeespeciallyRalphMelville, AdelundRevolutioninBöhmen:StrukturwandelvonHerrschaftund GesellschaftinÖsterreichumdieMittedes19.Jahrhunderts (Mainz,1998),pp.22–58,88.

³³Melville, AdelundRevolution,p.87;AntonSpringer, GeschichteÖsterreichsseitdemWiener Frieden1809 (2vols,Leipzig,1863–65),1:526–7.

³

³

⁴ Springer, GeschichteÖsterreichs,1:525.

⁵ See,forexample, “HistorischeStändeoderVolksrepräsentation,” Grenzboten,6(1847):550–61.

³⁶ MadeleineRietra, “ÖsterreichunddessenZukunft:ZurÖsterreich-UtopiedesFreiherrnViktor FranzvonAndrian-Werburg(1815‒1858),” inKlausAmann,HubertLengauer,andKarlWagner,eds, LiterarischesLebeninÖsterreich1848–1890 (Vienna,2000),pp.42–59.

³⁷ ÖsterreichunddessenZukunft (Hamburg,1843),p.202;FritzFellner, “DieTagebücherdesViktor FranzvonAndrian-Werburg,” MÖStA,26(1973):334–6;Bibl, DieniederösterreichischenStände, pp.39–57,320–1.ForAndrianandTocqueville,seeJosefRedlich, DasösterreichischeStaats-und Reichsproblem:GeschichtlicheDarstellungderinnerenPolitikderhabsburgischenMonarchievon1848 biszumUntergangdesReiches (2vols,Leipzig,1920–6),1:Anmerkungen:21,65,73.

ThepowerofsuchclaimswasevidentinthepetitionthattheLowerAustrian EstatessubmittedtotheEmperoronMarch12,1848inwhichtheycalledfora generalmeetingofthevariousprovincialcorporationsandinsistedthat “inthis crisistheStändecanmediatebetweenthegovernmentandchaos.Theycanbring togetherpeoplefromdisparateclasses,andbyincludingtheclassesnotyet represented,helptorestoreconfidenceinthegovernment;theycanhelpto reinfuseaspiritualrevivalandnationalprideandloyalties,whichwillinturn leadtoextraordinaryachievements.”³⁸ ThepathtakenbytheRevolutionof1848 dashedthesehopes,however,giventhattheEmperorwasforcedinMay1848to accedetodemandsforageneral,empire-wideparliament(theAustrianReichstag, whichmetinlateJuly1848)basedonwidespreadmanhoodsuffrage,withno structuralorelectoralconnectionstothepre-1848Stände.³⁹ TheStadionconstitutionofMarch1849similarlyignoredtraditionalcorporatistliberties.⁴⁰ Itwas hardlysurprisingthatAndrian-Werburg,whobefore1848wasanurgentvoicefor reformintheLowerAustrianEstates,evolvedintoastaunchanti-Viennafederalistafter1851,arguingforakindofconstitutionalgovernancebestepitomizedin theconservativeOctoberDiplomaof1860.⁴¹InatractwritteninJune1851but publishedposthumouslyin1859Andrianimaginedarenewed “ständisches Princip,” anchoredinarestorationofprovincialliberties,leadingto “theautonomyoftheLänderinalloftheiradministrativefunctions,whicharenotof necessitypartoftheReichsgewalt,becomingthefundamentalprincipleforthe Empire’sadministrativepolitics.”⁴²

ThefederalismrepresentedintheOctoberDiplomafailedinthefaceof Hungarianintransigeance,buttheresonanceofclaimstostructuralautonomy arrayedagainstthecentralministriesinViennawouldberenewedinthelater

³⁸“AdressederniederösterreichischenLandständevom12.März1848,betreffenddie ZusammenberufungeinesimSinneeinerVolksvertretungverstärktenCentralausschussessämmtlicher Provinzialstände,” in DieniederösterreichischenLandständeunddieGenesisderRevolutioninÖsterreich imJahre1848 (Vienna,1850),p.59.

³⁹ AsMazohlpointsout,theoutcomeinearly1848wasquitedifferentfromwhatAndrianandother aristocraticreformershadwanted.SeeBrigitteMazohl, “‘EqualityamongtheNationalities’,andthe Peoples(Volksstämme)oftheHabsburgEmpire,” inKellyL.GrotkeandMarkusJ.Prutsch,eds, Constitutionalism,Legitimacy,andPower:Nineteenth-CenturyExperiences (Oxford,2014),p.171. UponreadingAndrian’stractin1843,theearlyLiberalleaderJohannNepomukBergerobserved thattheauthorhadaccuratelydiagnosedtheevilsoftheregime,butthatAndrian’snotionthata reformedaristocracyembeddedintheStändecouldhelpresolvethecrisiswasabsurd,since “derAdel isteinabgelebtesInstitut,woernochLebensfähigkeithat,wurzeltseinOrganismusinanderen Verhältnissenundeswäreverkehrt,ihnaufganzheterogenenBodenverpflanzenzuwollen.” Berger, “ErinnerungenanGedanken,TatenundErfahrungenausmeinemLeben,” ÖR,5(1906):483.

⁴⁰ Redlich, DasösterreichischeStaats-undReichsproblem,1:357–61,364.

⁴¹SeeFranzvonSommaruga, “ViktorFreiherrvonAndrian-Werburg,” AllgemeineDeutsche Biographie,1(1875):451–2;FranzAdlgasser,ed., ViktorFranzFreiherrvonAndrian-Werburg: “ÖsterreichwirdmeineStimmeerkennenlernenwiedieStimmeGottesinderWüste.” Tagebücher 1839–1858 (3vols,Vienna,2011).

⁴²ViktorvonAndrian-Werburg, DenkschriftüberdieVerfassungs-undVerwaltungsfragein Österreich (Leipzig,1859),pp.23,29.Foritsgenesisseehis Tagebücher,2:466,entryofJune7,1851.