To the Ōuchiandtheir scholars

Contents

Acknowledgments

Conventions

Introduction: The Lost History of Ōuchi Rule

A New Periodization of Japanese History: The Age of Yamaguchi (1477–1551) and the Sengoku Era (1551–68)

Trade, Mining, and Sea Power

The Ōuchi, Korea, and the Question of “Ethnicity”

Religion and Rule

Individuals and Institutions

The Forgetting

Early Scholarship

The Structure of This Book

The Origins of the Ōuchi

Star Cults and Myōken

Three Tatara Lineages in Suō

2.

The Ōuchi Region

The Struggle for Survival, 1331–50

Conclusion

The Founder Ōuchi Hiroyo

Origins

The Conquest of Nagato

Controlling the Straits of Shimonoseki

Ritual Bonds of Lordship

The Mines of Iwami

Ties with the Court

The Planned Settlement of Yamaguchi

Turmoil of the 1370s

3.

Ōuchi Yoshihiro and the Forging of Ōuchi Identity

Quelling “Pirates” and Kyushu Enemies

Enshrining Authority

Yoshihiro in the Capital

Crafting Ōuchi Identity

The Ōei Disturbance (1399)

Sakai

Legacies

4.

5.

The One Who Could See Stars: The Unlikely Rule of Ōuchi Moriakira

Early Life and Lordship

Copper Mines and Trade

Kingly Status

Tripiṭaka (Buddhist Canon)

Ashikaga Rapprochement

Tombs, Kings, and Ōuchi Ethnicity

Conflict, Korean Ties, and Trading Networks

Ōuchi Administrative and Ritual Authority

The Localization of a National Shrine (Usa)

The Departure

Fraternal Succession, Expanding Trade, and Durable Administration

Naming Patterns and Succession Disputes

Pacifying Kyushu and Proselytizing Gods

Expanding Commerce

An Unexpected Death

6.

Trader, Shogun, King, and God

Early Life

Urban Development, Commerce, and Trade

7.

Reasserting Control over Nagato

Korean Ties and Ethnic Imaginations

Recognition of Ōuchi Ethnicity

Delegated and Personalized Authority

Creating a Western Warrior Government

Slouching toward War

Legacies

Ōuchi Masahiro and the Rise of Yamaguchi

Birth and Early Years

The Onset of the Ōnin War

Stalemate, Supply, and Naval Supremacy

Yamana Kuniko’s Defense of Yamaguchi

Ending the War

Divinely Sanctioned Authority

The Depersonalization of Administrative Practices

Economic and Cultural Exchanges

Recalibrating Ōuchi Ethnicity

Forging the Past

The Apotheosis of Ōuchi Norihiro

The Yamaguchi Polity

Turtle Taboos

The Age of Yamaguchi

8.

Early Years

The Meiō Coup (1493) and Its Ramifications

Yoshioki’s Violent Ascension

Harboring a Shogun

Conquering Kyoto

Yoshioki as Commander

Revisiting Myōken in the Capital

Becoming a Courtier

Cultural Patronage

Administering the Capital

Kyoto Currency Regulations

Trade with Korea, China, and the Ryūkyūs

Return to Yamaguchi

Possessing the Ise Gods

Transforming Yamaguchi and the Ōuchi Realm

Turmoil in Iwami and Aki

The Ningbo Incident

Last Battles

9. Yoshioki and the Apogee of Ōuchi Rule (1495–1528)

The Triumphs and Tragedy of Ōuchi Yoshitaka (1528–51)

Birth and Early Years

Succession

Ruling as Governor General of Kyushu (Dazai

Daini)

Trade with Korea

Tally Trade with China

Increasing Copper and Silver Exports

Yoshitaka’s Influential Advisers

Wars in Iwami and Aki

Possessing Itsukushima and Rebuilding Shrines

Yoshitaka’s Ritual Supporters

Consequences of Upholding Court Authority

Selecting a New Heir

Defending Iwami

The Prosperity of Yamaguchi

Turmoil in Kyoto

The Revolt

Conclusion

The Collapse

Ōtomo Hachirō

Appeals to Ōuchi Ethnicity

The Pliant Ruler

Christianity and the Portuguese in Yamaguchi

Becoming Ōuchi Yoshinaga

Turmoil

The Itsukushima Defeat

Prayers, Defeat, and Death

Ruin

Epilogue: Legacies

Ōuchi Nostalgia

Ōuchi Teruhiro’s Gambit

Post-Ōuchi Trade Disruptions

Rewriting and Reordering the Past

Fading Ōuchi Identity

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

A visit to Yamaguchi and a glimpse of its Rurikōji pagoda in the fall of 1995 served as the inspiration of the book. Once I returned from my travels, on 10.22.1995, I wrote to my adviser Jeffrey Mass, “I learned so many fascinating things about the Ōuchi which have come to light over the past few years that I am tempted to devote my next research project to the Ōuchi (but of course, I must first finish the current dissertation!).” As late as 2004, however, I had only drafted a single page sketch of this study. Attendance to the conference “Pieces of Sengoku: Interpreting Historical Sources and Objects from Japan’s Long Sixteenth Century” at Princeton on 4.27.2009, convinced me to embark on this endeavor. After many years, and the support of many people, this research came to fruition. I cannot adequately thank everyone who has helped me.

I was fortunate to have received a Japan Foundation Fellowship in 2011–12, where I spent a year in Japan, and an American Council of Learned Societies grant in 2018–19, which allowed me to complete my research. A 2017 Princeton Humanities

Council Magic Grant also helped me to analyze samples of Naganobori slag.

In Japan I benefited greatly from the pathbreaking research of a myriad of remarkable scholars, first among them Hirase Naoki, who opened me to the world of the Ōuchi and has been an invaluable guide, showing me the city of Yamaguchi and important artifacts and historical sites, and introducing me to researchers in the field, first in 1995 and again in 2011–12 and 2015. Without his guidance and support, this project would have been impossible to complete.

I am extremely grateful to the erudite Wada Shūsaku, who generously answered so many questions about the Ōuchi and their sources and led me on informative and enjoyable tours of Kudamatsu, Taineiji, Sue castles, Iwakuni, and the Nakatsu coin hoards (which were explained by Miura Narihisa, Fujita Shin’ichi, and Kanzaki Susumu), the route of Ōuchi Teruhiro’s invasion of Yamaguchi, and important sites linked to the Yoshimi. I learned more from him than words can convey.

Yamaguchi’s remarkable team of archaeologists, including Kitajima Daisuke, Satō Chikara, and Mashino Shinji, taught me much about Ōuchi ethnicity, roof tiles, trade, the founding of Yamaguchi, and experiments in metallurgy. Always

ready to share their time and knowledge, they have enriched this project immensely. I am particularly grateful to Kitajima Daisuke for his explanations of Ryōunji, and a memorable visit to Kōnomine and Tōshunji. In addition, Maki Takayuki explained Kōryūji Hikamisan, the Yamaguchi shrines, and changes in architecture and urban planning to both me and my students and was always an informative guide and source of good cheer. I have also learned much from Itō Kōji and Saeki Kōji about Kyushu, trade, and the Ōuchi. Both also provided me with valuable monographs, sources, and references.

I owe a great debt to Yoshikawa Shinji, who taught me much about the sources of the Japanese court. His enthusiasm and unstinting support means spurred me on as I researched the attempt to move Japan’s capital to Yamaguchi. He too introduced me to Ikeda Yoshifumi, whose knowledge of Naganobori and its copper has proved transformative and who has generously allowed me to analyze samples of slag and ore. Likewise, our trip to Mishima, Fukawa, and the beaches of Yuigahama, with Hara Hidesaburō and Kuroha Ryōta, will remain a fond memory.

I was able to visit Masuda, the mines at Tsumo, and Iwami Ginzan in June 2015 thanks to the efforts of Hirase Naoki. There I first met Nakatsuka Ken’ichi,

indispensable guide to Masuda, Tsumo, and the sources and history of Iwami. Nakano Yoshifumi and Yamate Takeo explained much about the Iwami Silver Mines, and I remember vividly the tours provided by Shinkawa Takashi, who helped me to fully appreciate the remarkable mines and their secret harbors, and Mr. Hasegawa, tour guide to the Ōkubo mine shafts (mabu). I have learned from and received support many more, and cannot adequately convey my debt, but I list them here—Ōzaki Chika, Egaitsu Michihiko, Furuya Yūko, Arikawa Nobuhiro, Kawamura Shōichirō, Amino Yukari, Ebara Masaharu, Kurushima Noriko, Matsui Naoto, Hagihara Daisuke, Harada Masatoshi, Nagasawa Kazuyuki, Nakagi Sayumi, Itō Hajime, Mori Michihiko, Hori Daisuke, and Minami Takao.

Horikawa Yasufumi, while here at Princeton, advised me in translating Ōuchi laws, while Patrick Schwemmer provided invaluable insights and translated the Portuguese version of the 1552 document. Special thanks too to Christina Lee.

Furthermore, Horikawa Yasufumi and Oka Mihoko of the Historiographical Institute, the University of Tokyo, and Lucio de Sousa of the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies helped me to secure images of this record, and Benita Ferreira transmitted them to me, for which I am grateful.

My knowledge of sixteenth-century culture sources and insights into sources would not be complete without many informative discussions with Andrew Watsky. He and Alexandra Curvelo helped me to better understand much about Sakai. Likewise, Peter Shapinsky helpfully introduced me to the Riben Yijian. Christopher Mayo has been an invaluable resource for all things pertaining to the Ōtomo. Peter Kornicki informed me of Korean books with an Ōuchi King of Japan seal (9.5) and I want to thank him, Kate Wildman Nakai, Linda Grove, and Shinozaki Yōko for all their help in securing these images. For other image permissions, I am grateful to Wada Shūsaku of the Yamaguchi monjokan, Kitajima Daisuke of the Yamaguchi-shi kyōiku iinkai, Harayama Eiko of the Masaki Museum of Art, Yamada Minoru of the Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum of Art, and Inoue Mayu of the Yonezawa-shi Uesugi Museum. Special thanks to Mikami Yasushi for showing the statues of Yōkōji, Anne Rose Kitagawa and Carrie Simonds for giving me the opportunity to view the 1510 Tale of Genji album in person in 2005, Rachel Sanders for insights into silk used for this album, Dorinda Neave for her research about the monk Chikai, Xiaojin Wu for explaining the value of bamboo paper, Shimao Arata for the Ōuchi role in disseminating Chinese paintings to the Ashikaga,

Louise Cort for pottery found in Hagi, and, in the seas near Bermuda, the first mate of the Celebrity Summit for insights about stars and navigation.

Crafting this narrative has proved time-consuming, and in reading an early draft of my manuscript, my debt to three friends is especially great. Email exchanges about caltrops led to a fruitful partnership with Royall Tyler. From discussing translations to exploring issues of style and interpretation in this text, which he read repeatedly, I have learned much from Royall, who is an exemplar in so many ways. Also, I would like to thank Philippe Buc and Jaqueline Stone for reading earlier versions of this manuscript and providing excellent advice. Philippe taught me to approach Japan from a comparative perspective and appreciate aspects of Japan I would have otherwise overlooked. Jacqueline Stone, with her deep knowledge and good cheer, is an inspiration.

David Lurie helped me with my understanding of ancient kabane, and thanks to Michael Como, I came to appreciate the importance of immigrants to ancient and medieval Japan. Morgan Pitelka, David Spafford, and Noda Taizō have encouraged me to explore Warring States history, while David Robinson has taught me much about Ming military and diplomatic history. Ashton Lazarus offered insights concerning passages of the Kanmon nikki. Nam-lin

Hur of the University of British Columbia is a wellspring of information regarding Japanese and Korean connections. During my years at Bowdoin, I was fortunate to have stimulating intellectual exchanges with John Holt, Allen Wells, Olufemi Vaughan, Sree Padma, Lawrence Zhang, Ya Zou, and Paul Friedland. Adam Clulow has imparted his knowledge of maritime trade and offered me encouragement at important times. Suzanne Gay and James Dobbins have also immeasurably improved this work. Special thanks too to Bridget St. Clair for giving me the opportunity to explore Japan and Korea in the Le Soléal and to better understand the Ōuchi realm from the seas. Finally, I want to thank Nancy Toff, Cynthia Read, and Chelsea Hogue at Oxford University Press for their invaluable help in publishing this manuscript and Mary Mortensen for indexing this work.

I had the opportunity to present my preliminary findings at Princeton’s East Asian Department Colloquium Series, a Works in Progress lecture at the Davis Center, IAS Princeton, as well as the University of Cambridge, Yale University, Columbia University, the Seattle Art Museum, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of British Columbia, the University of Vienna, and the Central European University at Budapest, and at Yamaguchi for the

thirteenth Ōuchi shi rekishi bunka kenkyūkai lecture. I am grateful to the many who invited me and attended these talks and regret that I do not have the space to personally thank them all in these acknowledgments. In particular, I would like to thank Benjamin Elman, who encouraged me to use the model of a “segmented polity,” Federico Marcon, who taught me much about coins, currency, and the concept of the historian as a redeemer of the past, as well as Sue Naquin and Jennifer Rampling for insights on matters related to metallurgy and alchemy. Brian Steininger and Tom Hare provided many insights regarding Japanese literature and culture and Bryan Lowe has been a great resource for ancient Japan. Helmut Reimitz and Willard Peterson helped me to hone my understanding of Ōuchi identity, Ksenia Chizhova introduced important Korean sources and concepts, Amy Borovoy gave the gift of a rare Ōuchi related book, Sheldon Garon provided probing comments on chapter 5, Xin Wen and Buzzy Teiser illuminated the world of Central and East Asia, and William Chester Jordan imparted upon me the wise words of Lawrence Stone, to “make sure that history is never boring.”

Princeton’s graduate students have provided me with great intellectual stimulation, and here let me thank those who directly aided me in this project.

Megan Gilbert, David Romney, and Nate Ledbetter have taught me more than they can know. Megan, for her skepticism, erudition, critical spirit, and precision in writing; David, for his immense knowledge of things relating to Yoshida Shinto; and Nate, an intrepid explorer of the military documents of Kyushu. I would also like to especially thank Gina Choi for her great help in translating articles about copper and for teaching me much about Ōuchi/Korean interactions in the 1540s. I am deeply indebted to Soojung Han, who helped me to use Korean databases and taught me much about Korean history and notions of East Asian ethnicity.

At Princeton, Setsuko Noguchi helped me to purchase two Ōuchi Yoshioki documents for Princeton’s library, as well as a treatise on copper smelting. Hyoungbae Lee aided me in explaining the principles of Korean romanization and checking over my transliterations. I received great help in translating my research into Japanese thanks to the efforts of Yoshikawa Itsuko in Japan and Megumi Watanabe at Princeton. And I am grateful to my son George, who helped me to scale the steep slopes of Kōnomine and shared so many important journeys, my wife Yūko for her patience and good cheer, and our dog Rosie, my loyal and happy companion to the end.

Conventions

Macrons will not be used for common place names (Honshu, Kyushu, Kyoto) unless they are part of official titles, names of books, articles, and publishers.

Dates will be reproduced in the month, date, year format, with years in the CE format. Dates from the lunar calendars of Japan and Korea will not be translated to the Julian or Gregorian calendar, but will be referred to numerically (first month, second month).

Chinese characters (kanji) will not be used unless the meaning of the character is particularly difficult to decipher for researchers proficient in Japanese.

All ages will be according to the traditional Japanese count, where year one begins at the time of birth and the second year is determined by the new year. Thus, a child born on New Year’s Eve would be two years old on New Year’s Day.

The McCune-Reischauer system will be used for romanizing Korean, Pinyin will be used for Chinese, and Modified (Revised) Hepburn will be used for Japanese.

Unless otherwise indicated, the place of publication is Tokyo.

Introduction

The Lost History of Ōuchi Rule

Much that was has been forgotten. The vicissitudes of time, the fragility of sources, and the destruction of regimes, institutions, and cultures have caused much of the human past to disappear. This story of the Ōuchi, a family all but extinct, attempts to recover one such lost history.

The Ōuchi ruled western Japan for centuries, until a 1551 coup led to the death of nearly all the Ōuchi and their core supporters. After 1569, memories of all facets of Ōuchi rule—their culture, modes of governance and ritual practice, trade policies and international ties, and even their distinct ethnic identity—faded. Nevertheless, enough Ōuchi architectural monuments, cultural artifacts, and administrative documents survived to afford, through determined effort, a glimpse into their world.

This book traces the history of the Ōuchi and explores how they amassed power and influence from the fourteenth through the mid-sixteenth centuries. It is organized on biographies of Ōuchi leaders to reveal the structural advantages and limitations each ruler

confronted and aims to show how they variously met with success, failure, and, almost invariably, unintended consequences. Focus on these individuals allows for the creation of a totalizing history, as coverage of both long-term processes and specific events can be combined in a single, encompassing narrative. However, it is neither a familial nor a regional history. Rather, it takes the Ōuchi as a starting point to investigate neglected areas and to revise received understandings of the history of medieval Japan. It aims to destabilize the standard political narrative of medieval Japanese history that portrays Kyoto, Japan’s capital, as the economic, cultural, and political center of Japan. The intent is not to show how a “periphery” interacted with a “center,” but rather to suggest that the political and economic core of Japan migrated from the capital to the western tip of Honshu during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.1 This approach affects accepted views of Japan and East Asia. Japan has, for most of its history, been portrayed as a relatively isolated polity, but this new view from the west shows that Japan was politically, culturally, and economically integrated with the rest of East Asia. The study will explore the cultural, economic, and political underpinnings of Ōuchi rule, highlighting the unique features of their culture, institutions, and policies, and

emphasizing a new understanding of Japan’s political history.

The Ōuchi founded the settlement Yamaguchi in the fourteenth century, at a time when urbanization was rare in Japan. Whereas earlier efforts at urban development had been limited to the establishment of capitals such as Kyoto or Nara in the eighth century, or the organic rise of regional and trading outposts that grew up around important shrines located near excellent harbors in the eleventh and twelfth (Kamakura and Hakata), Yamaguchi was not linked to either. Instead, it was founded around the dwelling of the Ōuchi lord. Previously, no one had planned a comparable settlement, laying out its roads asymmetrically at an unremarkable crossroads, far from a useful harbor or an old and prominent site of worship.2 This city was the first of several palace settlements, which would be founded throughout Japan over the course of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, although in terms of size, age, and influence, Yamaguchi was unique.3

Yamaguchi had access via river and road to the Japan Sea in the north, and the Inland Sea in the south. Roads from the east led to silver mines, while those to the west ran by copper mines. All ended at serviceable harbors. The site was selected to facilitate exchange and trade. It is located on the western tip of Honshu, thirteen miles north of Ogōri, the nearest

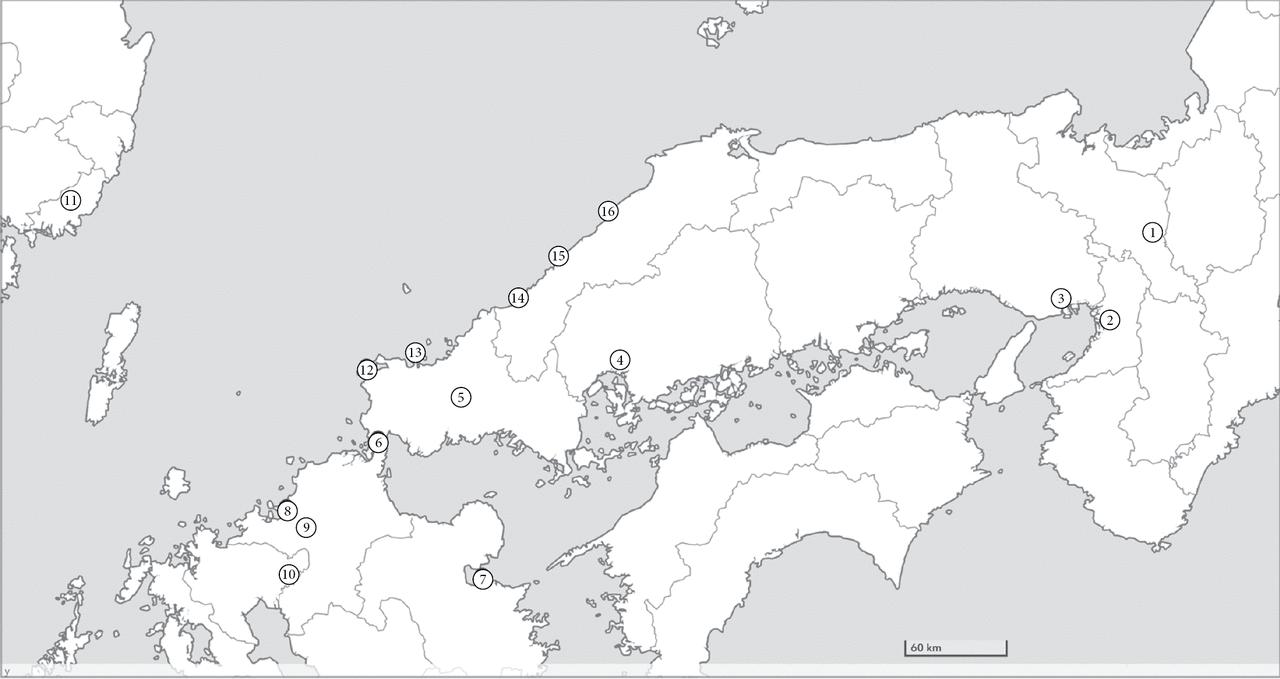

harbor on the Inland Sea, twenty-four miles to the south of the nearest port on the Japan Sea, forty-two miles to the east of the Straits of Shimonoseki, the western tip of Honshu (Figure I.1).

Figure I.1 Map of Major Cities and Harbors of Central, Western Japan, and Korea. 1.Kyoto, 2.Sakai, 3.Hyōgo (harbor), 4.Tōsai (harbor), 5.Yamaguchi, 6.Moji (harbor), 7.Funai (city and harbor), 8.Hakata (city and harbor), 9.Dazaifu, 10.Kanzaki (harbor), 11.Pusan (city and harbor), 12.Hijū (harbor), 13.Senzaki (harbor), 14.Masuda (harbor and city), 15.Hamada (harbor), 16.Nima (harbor).

Ultimately, this unfortified settlement thrived, becoming urban in the mid-fifteenth century. By then it boasted many temples and important shrines, and merchants, warriors, and artisans congregated there. Located next to the central crossroads, the residence of the Ōuchi lord expanded over time, as did its

gardens. People might enter and gawk at the lords or climb walls to gaze at buildings or processions. The Ōuchi lords would keep the town clean, establish curfews and public toilets, and regulate nearby hot springs. The town, which remained unfortified, prospered, and its people built large floats for Gion festivals. These circulated through the town, attracting raucous crowds.4 Such festivities were not confined to Yamaguchi, since they had spread from Kyoto to Hakata as well.

In the early sixteenth century the Ōuchi relied on geomancy to claim that Yamaguchi abided by the norms expected of a capital. The establishment of large temples there, as well as the moving of major shrines, made what had been a small palace settlement an imposing regional center.

While Yamaguchi flourished, Kyoto withered and burned. The penultimate Ōuchi lord Yoshitaka (r. 1528–51), aware of the turmoil in Kyoto, tried to bring the emperor to Yamaguchi and make it Japan’s capital. He failed, however, and was overthrown. The city was sacked, resulting in widespread destruction and depopulation. The wealth of Yamaguchi flowed elsewhere, and the fact that it had overseen a trading empire was forgotten.

A New Periodization of Japanese History: The

Age of Yamaguchi (1477–1551) and the Sengoku Era (1551–68)

The present study challenges the accepted notion that the period from the Ōnin War (1467–77) to 1568 constituted an age of civil war. One reads that during this time “the body politic of Japan was undergoing a collapse” as “the central organs that had given vitality to the old governing order—the imperial court and the shogunate—were exhausted and powerless.”5 In reality, however, Japan did not fragment into shifting coalitions of warring states (sengoku) from 1467 through 1568. Instead, the imperial court, supported by the Ōuchi, functioned well until 1551. During the Ōuchi heyday, Japan constituted a segmented polity, governed by two complementary cities, the trading city of Yamaguchi, which served as the economic core of Japan, and Kyoto, the old capital, which remained the focus of emperor-centered rites. For this reason, much of the era hitherto classified as the Sengoku Age could better be seen as the Age of Yamaguchi. This focus on the two complementary cities of Yamaguchi and Kyoto rehabilitates the role of a court long thought to have been politically supine and economically enervated.6 It suggests that the court, which became a junior governing partner with the Ashikaga bakufu (1338–1573), rebounded after the

implosion of that warrior government during the latter half of the fifteenth century. Court officials reached out to the Ōuchi to ensure that the rites of state would continue to be performed, albeit increasingly in the Ōuchi territories rather than the Kyoto region. In turn, the Ōuchi first occupied Kyoto for a decade (1508–18) in order to stabilize central Japan. They then abandoned that endeavor and, in 1551, attempted to move the court to their city of Yamaguchi, thereby making it the capital of Japan.

Most studies of this period focus on the turmoil of the mid-sixteenth century. John Hall, for example, argued that “it is clear that by 1550 Japan had reached a state of political and social instability that could only be brought under control by a militarily powerful autocrat.”7 This study does not dispute Hall’s statement, but instead of seeing 1550 as the nadir of a long period of decline, it suggests that the Ōuchi controlled areas of western Japan experienced relative stability, and then all of Japan experienced a sudden political collapse in 1551. It argues that the Yamaguchi heyday lasted until 1551, and that the period of intense civil war, which is usually thought to have lasted until about 1568, began only then. The Sengoku era was a century shorter than has commonly been assumed.