PREFACE

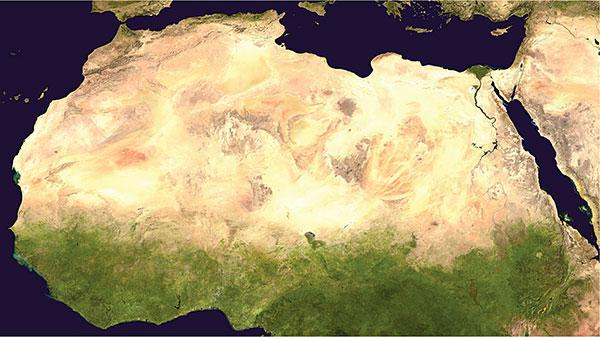

THE Sahara is the greatest of the world’s hot deserts, extending for a distance of 6,000 kilometres across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, creating a formidable barrier between the communities surrounding the Mediterranean and those who inhabited the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. For many scholars in the nineteenth century the desert was seen as an insuperable obstacle preventing the spread of the benefits of Western civilization. Admittedly the Nile created a corridor along which complex and creative societies flourished— Egyptians, Nubians, and others—and the Red Sea allowed traders from the Mediterranean to reach the Indian Ocean, benefiting African polities, like the kingdom of Axum, able to control essential ports on the eastern shore. But all this was consistent with the current belief that the cultural advances and inventions that formed the basis of civilization came from the Near East: the ex orientelux hypothesis as it became known. People living in remote parts of the world didn’t invent things: they simply benefited from the brilliance of others through the process of diffusion.

Overt diffusionism of this kind, still popular in some quarters into the early twentieth century, came under increasing attack as more was learnt of cultural development in different parts of the world through archaeological exploration. Yet it was a view of Africa still widely held well into the middle of the century. To some extent such a perception was understandable. Archaeological endeavour in subSaharan Africa had concentrated on the exciting issue of human

origins and early Palaeolithic developments: there had been little effort spent on exploring the complexity of later sites.

All this was to change in the 1960s, when far more attention began to be focused on the study of settlements, especially in the Sahel—the zone of steppe and savannah lying beyond the southern edge of the Sahara—and in the desert itself. The new data that began to be published threw an entirely different light on questions of social complexity, state formation, and connectivity, allowing more subtle and sophisticated narratives to be presented in the flurry of books on African archaeology published since the 1990s. Understandably these texts have focused on the African achievement and have tended to play down the contribution of the Mediterranean and the Near East. It was a valuable and necessary corrective, but it has created something of a new bias.

Any attempt to write a balanced account of the desert and its surrounding communities comes up against the problem of the disparity of the database. For the Mediterranean and the Near East, including Egypt, archaeological activity since the eighteenth century has produced a massive amount of detailed information about settlements, burials, religious sites, artefacts, and ecofacts. In addition to this, there is a rich historical record, in some instances going back nearly five thousand years. Greek, Phoenician, Carthaginian, and Roman sources provide a detailed picture of the impact of classical civilizations on North Africa, while later, Arab and other medieval texts become increasingly more informative. For subSaharan Africa the situation is very different. The tradition of research excavation had hardly begun by 1960, and thereafter, although there have been major advances in knowledge, the actual number of investigations has been minimal compared to the work undertaken in North Africa. Nor does the documentary record offer much compensation since it does not begin until the Arab traders started to take an interest in the region in the eighth century.

At the time of writing, political unrest throughout much of the Sahel is making archaeological work difficult and dangerous, and elsewhere in the Saharan region, in Libyan territory, the unstable

situation has brought productive fieldwork programmes to a premature close. Since there is little prospect that any large-scale work will resume in the immediate future, the imbalance in the evidence base is likely to remain, at least for a while.

That said, work since the 1960s has enabled us to begin to appreciate the energy and complexity of the communities who lived around and within the desert, and to trace change over time. It has thrown new light on how they responded to changing environmental conditions as the desert margins shifted, and how, gradually, the links between neighbours grew to become a complex pattern of communication routes embracing the entire desert, binding north to south. So, in 1324, Mansa Musa and his entourage, with eighty camels, could set out with little concern across the desert from Mali to Cairo and on to Mecca, to return safely; and in 1591 a Moroccan force of three thousand infantry and fifteen hundred light cavalry, with six cannons, could cross the desert to confront the Songhai empire. Like the ocean, the sea of sand, far from being a barrier, became alive with movement.

This book, then, is about change, connectivity, and the compulsions that made humans challenge the desert. What it sets out to do is to show that Africa and Eurasia are one great landmass bound together by their shared history.

Questions of nomenclature inevitably arise when dealing with a complex area like Africa. Three points need clarification here. The indigenous peoples of much of the northern parts of Africa referred to themselves as Amazigh (pl. Imazighen) in the Tifinagh language, but in the literature they are usually called Berbers, a term used by the Arabs that was originally derived from the Greek barbaroi, meaning ‘those who speak unintelligible languages’. We have chosen to use this more familiar name. ‘Sudan’ is another potentially confusing term. Nowadays we recognize it as the name of a nation state, but strictly it refers to the whole of the sub-Saharan Sahel, coming from the Arabic ‘Bilad al-Sudan’, meaning ‘the land of the blacks’. When it is used as a geographical term in this sense, we will refer to ‘the Sudan’: the political entity will be called, simply, ‘Sudan’.

Finally, a distinction must be made between Mauritania, a modern state in West Africa, and Mauretania, the region of north-west Africa covering much of Morocco which became a Roman province.

B.C.

Oxford

September2022

The Desert, the Rivers, and the Oceans

The Long Beginning

Domesticating the Land, 6500–1000 BC

Creating Connectivities, 1000–140 BC

The Impact of Empire, 140 BC–AD 400

An End and a Beginning, AD 400–760

Emerging States, AD 760–1150

Widening Horizons, AD 1150–1400

Africa and the World, AD 1400–1600

Retrospect and Prospect

AGuidetoFurtherReading

IllustrationSources Index

Bedrock

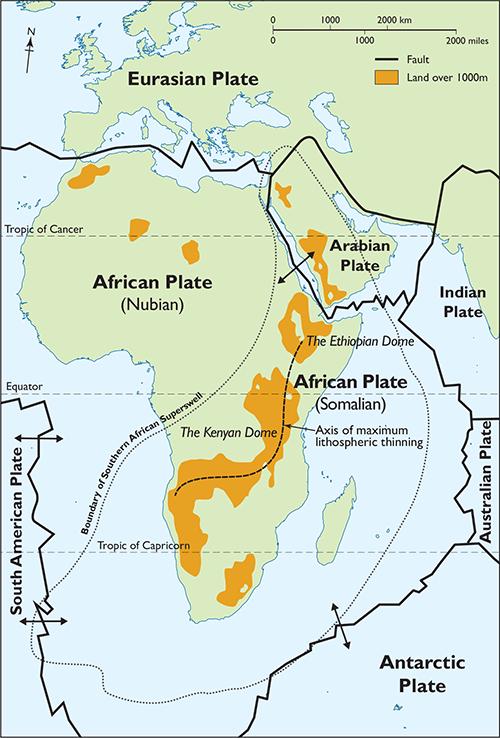

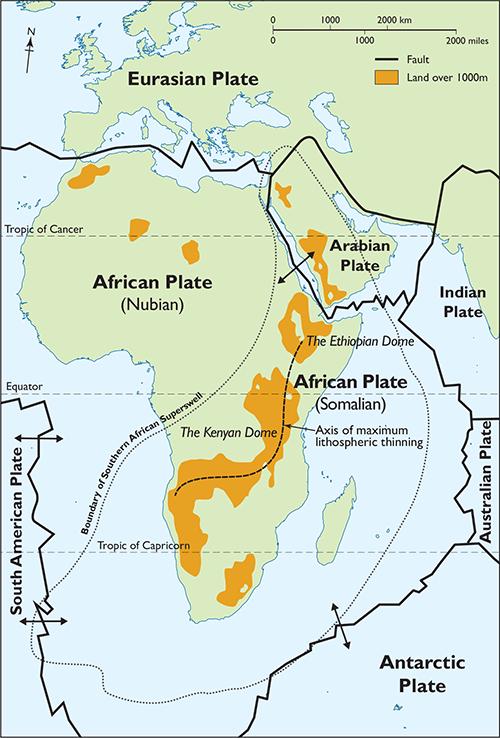

Two hundred and fifty million years ago, in the Permian period, Africa, like all other parts of the world, belonged to a single landmass named Pangaea surrounded by the Ocean. But in the molten magma of the earth’s core, constant currents put stresses on the solid surface crust, causing it to crack into large plates, some of which pulled apart from each other, allowing in the Ocean, while others collided, rucking up the edges to become mountain ranges. By sixty-five million years ago, the great landmass of Africa had torn free from what was to become the American continent, and other plates, later to become India, Australasia, and Antarctica, had broken away from its eastern side, Australia and Antarctica to flow south, while India, along with Africa, moved north, eventually colliding with Eurasia, leaving a narrow arm of the Ocean, called the Tethys Sea (now the Mediterranean), to separate North Africa and Europe.

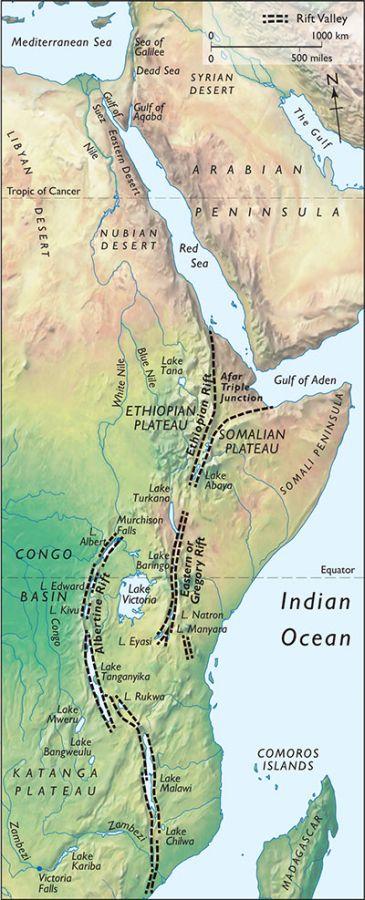

1.2 Africa began to take on its familiar shape when, in the mid Cretaceous period, the great landmass of Pangaea began to break up into plates. Pressure from the earth’s core pushed up the hard crust (lithosphere), causing it to thin and crack. The African plate split into the Nubian and Somalian plates and pulled apart, the cracks creating the rift valleys.

1.3 The rift valleys run from southern Mozambique to the Red Sea, at the northern end joining the wide fissures created by the drifting apart of the African and Arabian plates. The Albertine Rift valley is, for the most part, filled with lakes.

By this stage Africa had more or less achieved its present shape, with the island of Madagascar now broken away, but with the Arabian plate still attached.

In more recent geological times fragmentation has continued, with the Arabian plate pulling away, creating the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Meanwhile, East Africa was experiencing new tensions as the upwelling of the viscous mantle of the earth’s core began to push up the surface crust, creating two great areas of highland, the Ethiopian Dome and the Kenyan Dome. The stress was such that the crust eventually split, forming rift valleys, deep fissures flanked by cliff-like escarpments up to 1,000 metres high. There are three major fracture lines, the Albertine Rift, or Western branch, the Gregory Rift, or Eastern branch, and the Ethiopian Rift. The Albertine Rift is now partially occupied by a succession of sinuous lakes, Malawi, Tanganyika, Kiva, Edward, and Albert, while the Gregory Rift is home to Lake Turkana. The Ethiopian Rift tore through the Ethiopian Highlands to join with the wider parting of the plates, filled now by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The African rifts represent a fracture zone created as the eastern strip of Africa, known as the Somalian plate, pulls away from the rest of the continent, the African (or Nubian) plate.

Many of the characteristics of Africa that were to influence human behaviour were created by the tectonic movements that give structure to the continent. Its coasts, caused by the pulling apart of the plates, were, for the most part, sheer. This has left the country, especially the Atlantic coast, with a dearth of good ports, while the virtual absence of a continental shelf has meant that fish stocks are poor—a disincentive to the development of sailing. The creation of a narrow protected passage, now the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, did, however, provide a convenient route for the maritime trade between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean which began to become more intense in the third century BC, and this encouraged

the growth of ports along the African shore to the benefit of the communities commanding them. The Ethiopian Highlands had a rather different effect. Their elevation ensured heavy rainfall, and it was this that fed the Nile. The river, eroding the uplands as it flowed, generated a heavy load of sediment, which was deposited in the lower reaches of the valley as alluvium, so crucial for maintaining the fertility of the land. It was this upon which the prosperity of the Egyptian and Nubian states depended. The special microclimate of the highlands also supported a distinctive flora, including several plants that could be cultivated for food (p. 77 below).

1.4 The rift valleys are defined, for much of their length, by steep cliffs where the earth’s crust has fractured and the plates have moved apart. The lowlands between provided congenial environments favourable to the evolution of humans, the wide corridors encouraging migration. The image is of the Great Rift Valley in Kenya.

The Ever-Changing Climate

When the German traveller Heinrich Barth made his epic journey across the Sahara to Timbuktu in 1850–4, he was astonished to discover scenes of humans and animals painted and carved on rock surfaces in remote regions of the desert. That the animals depicted were no longer to be found there posed a problem. So too did the authorship. He could not believe them to be the work of uncivilized tribesmen. ‘No barbarian could have graven the lines with such astonishing firmness, and given to all the figures the light, natural

shape which they exhibit.’ The images, he suggested, were probably carved by Carthaginians, but that the animals the artists chose to represent could not possibly have existed in the prevailing desert conditions showed that the climate had once been far more congenial. This was the first indication that the Sahara had not always been a desert. Subsequent work has shown not only very many more images of the kind Barth discovered—so many that one observer has described the Sahara as the largest art gallery in the world—but has provided sound evidence to allow the many changes of climate experienced by North Africa to be carefully charted over the last twenty thousand years.

Climate change is a complex process caused by the interplay of many factors. In the 1920s the geophysicist Milutin Milankovic suggested that the underlying drivers were shifts in the orbital parameters of the earth caused by the gravitational interaction of the earth with the moon and the larger planets. He identified three effects, precession of the equinoxes, obliquity, and eccentricity, each occurring in cycles of different periodicity. Of these, precession of the equinoxes is now known to be the prime cause of major changes in the climate experienced by the Sahara, creating a shift from dry to wet over a span of twenty thousand years, after which the process goes into reverse. Two phases can be recognized, the one related to the wobble of the earth’s axis of rotation, the other to the slow rotation of the earth’s elliptical orbit round the sun. It is during this phase that the northern hemisphere is turned more directly towards the sun and absorbs more heat. Because of the lower thermal inertia of the land, the northern African landmass heats up more than the adjacent Atlantic Ocean, creating an area of low pressure. This draws in moist air from the Ocean, bringing summer monsoonal rains. During the winter the land cools, reversing the winds, returning the land to drier conditions. The greater the angle of the earth, and the more of the landmass that is heated in summer, the further north the monsoonal rains penetrate. As the angle swings back, the process goes into reverse. Thus, precession of the equinoxes directly determines the extent of the greening or the

desertification experienced by the Sahara over a twenty-thousandyear cycle.

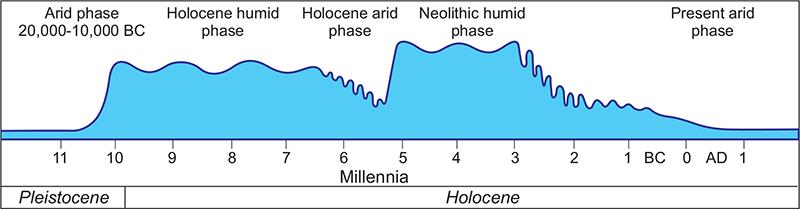

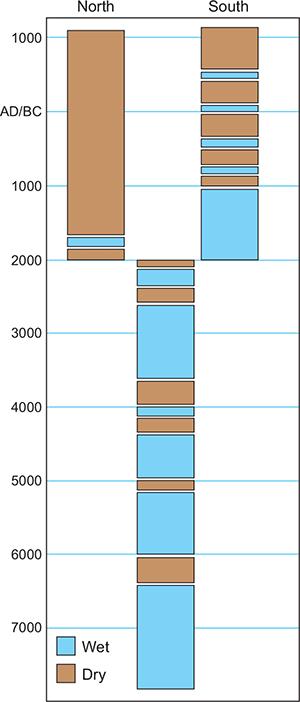

1.5 Changes in climate over the millennia had a dramatic effect on vegetation. Although the factors causing climate change were largely due to cyclic changes in the earth’s orbit and inclination, they impacted on different areas in different ways. The diagram shows changes in humidity in the Fazzan from the end of the last ice age to the present day. For much of that time the climate, with its long humid phases, was far more suited to human occupation than it is now.

The astronomical cycles that control the desert climate also drive the formation and thawing of the ice sheets over the northern part of the hemisphere, so there is a direct chronological relationship between the two phenomena. In the period when the ice sheets were at their greatest, during the Last Glacial Maximum, the Sahara desert was at its most extensive, but as the northern hemisphere began to warm and the ice melted, heralding the beginning of the Holocene period, so the desert became moister. This phase is known as the African Humid Period. The process began around 12,800 BC but was soon interrupted by the onset of a brief cold interlude known as the Younger Dryas period (10,900–9700 BC), triggering the expansion of the desert. Humidification quickly resumed and the Sahara became green again, the phase lasting until about 3000 BC when desertification began once more, by the end of the first millennium BC reaching a state comparable to that of the present day. Through the long humid period, from 9500 to 3000 BC, the climate of North Africa fluctuated, with several hot, dry episodes interrupting the predominant cool, damp norm. One, rather more persistent than the others, began about 6100 BC and lasted for

almost a millennium. As we will see later, it had a significant effect on hunter-gatherer communities (pp. 63–5 below).

Charting the climatic fluctuations of the African Humid Period has challenged the ingenuity of scientists, leading to several quite separate studies being undertaken in different parts of the continent. One looked at changes in lake levels over the last twenty thousand years, the levels relating directly to precipitation. Another measured oxygen isotope concentrations in fossil foraminifera (single-cell organisms with shells) in ocean sediments accumulating in the river Niger outflow. Since the levels are directly related to salinity, and salinity is a factor of the volume of fresh water outflow, oxygen isotope levels are a proxy for rate of precipitation. In a third study, cores taken through the sediments which had accumulated in Lake Tanganyika enabled hydrogen isotopes from fossil leaf waxes to be measured: the higher the reading, the thicker the wax, representing a more arid climate. Finally, ocean cores taken off the west coast of Africa showed a variation in the thickness of the lenses of dust blown offshore from the Sahara, the variation reflecting the changing aridity of the desert. What is particularly satisfying about these varied studies is that the results are very closely comparable, providing a detailed and reliable picture of climate change over the last twenty thousand years.

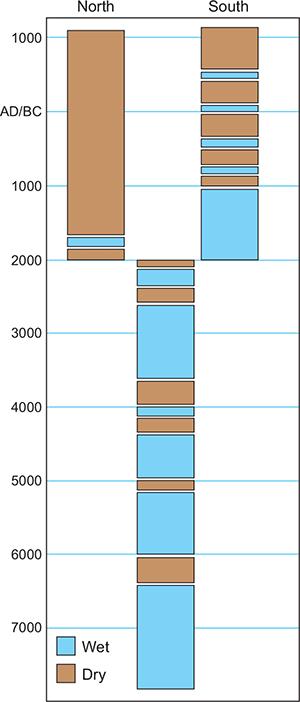

1.6 Even in comparatively small regions like the Western Sahara there were times when the effects of climate change differed from one subregion to another. The diagram shows that after 2000 BC the northern part of the Sahara remained continuously dry while the southern regions enjoyed episodes of more humid weather.

One of the surprising features which all these studies show is the suddenness of the onset of high humidity at the end of the Younger Dryas about 9700 BC. The transition lasted only a few centuries. At the end of the humid period, the change to desert conditions, beginning about 3000 BC, was also relatively rapid but was spread over a longer period of time and the many fluctuations were not exactly synchronous in all parts of the region. In the eastern Sahara, core sediments suggest a more gradual end to the humid period. There are also differences between patterns recorded to the north and south of the desert. In the north the land reverted rapidly to desert and remained so without alleviation. This could be because the area lay in the rain shadow of the Atlas Mountains and westerly airstreams off the Atlantic lost much of their moisture content on the western flanks of the range. In the south there was no impediment to the inflow of moist air from the ocean and the transition to desert was slower.

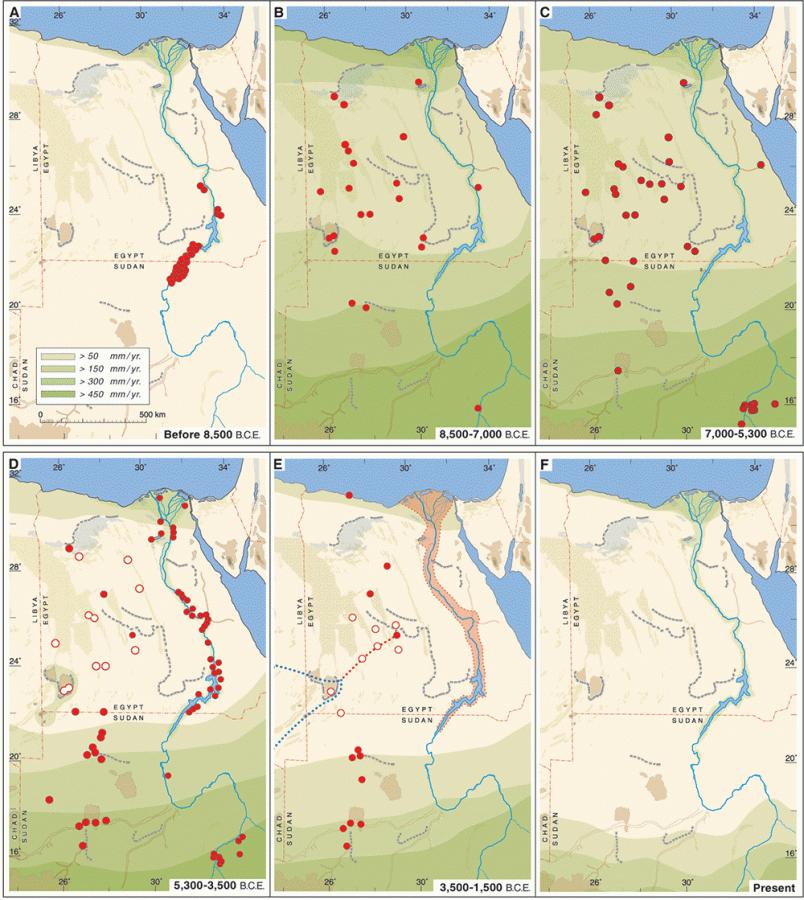

These changes in climate had a direct effect on human settlement and economy. One elegant study, focusing on settlements in the eastern Sahara identified in the course of intensive fieldwork, shows this in a dramatic way. During the Last Glacial Maximum and the late stages of the Pleistocene, up to about 8500 BC, when extreme desert conditions prevailed, the eastern Sahara was totally devoid of settlement except for the valley of the Nile. With abrupt onset of the monsoon rains (8500–7000 BC) heralding the humid period, savannah spread widely across the area that had once been desert and hunter-gatherers followed, colonizing much of the region. As the humid optimum set in (7000–5300 BC), the density of settlement increased, but the higher rainfall meant that the Nile valley was too marshy for human habitation. The retreat of the monsoonal rains and the onset of desertification, beginning here about 5300 BC, saw a retreat of settlement southwards into areas still savannah and into the Nile valley, which had now dried out sufficiently to become habitable once more. The return to full desert conditions about 3500 BC, which restricted the community to the Nile valley, was one of the

factors that drove the changes that led to the emergence of Egyptian civilization.

1.7 A detailed archaeological survey carried out in the eastern Sahara shows how climate change over five thousand years had a dramatic effect on where communities lived. The colours on the maps indicate rainfall zones measured in millimetres of rain per year.

The long African Humid Period was of crucial significance in the development of North Africa. In the ninth millennium BC, it allowed

communities of hunter-gatherers to spread wide throughout a vast region that for long had been a barren desert and to devise economic strategies suited to the environments they chose to inhabit. During this time, people learnt to domesticate plants and animals, and networks of communication became increasingly extensive. Then, around 5300 BC, desertification began to set in, and gradually, over the next two millennia, as the desert expanded, people were forced to move on to find environments where life could be sustained. Some moved north to the Mediterranean coast and the Atlas Mountains, others went south to the narrow corridor of steppe and savannah between the desert and the dense tropical forest, leaving, largely empty, the wide expanse of desert that now separated them. The rest of the story is about the ways in which people re-established connectivity across and around the desiccated waste.

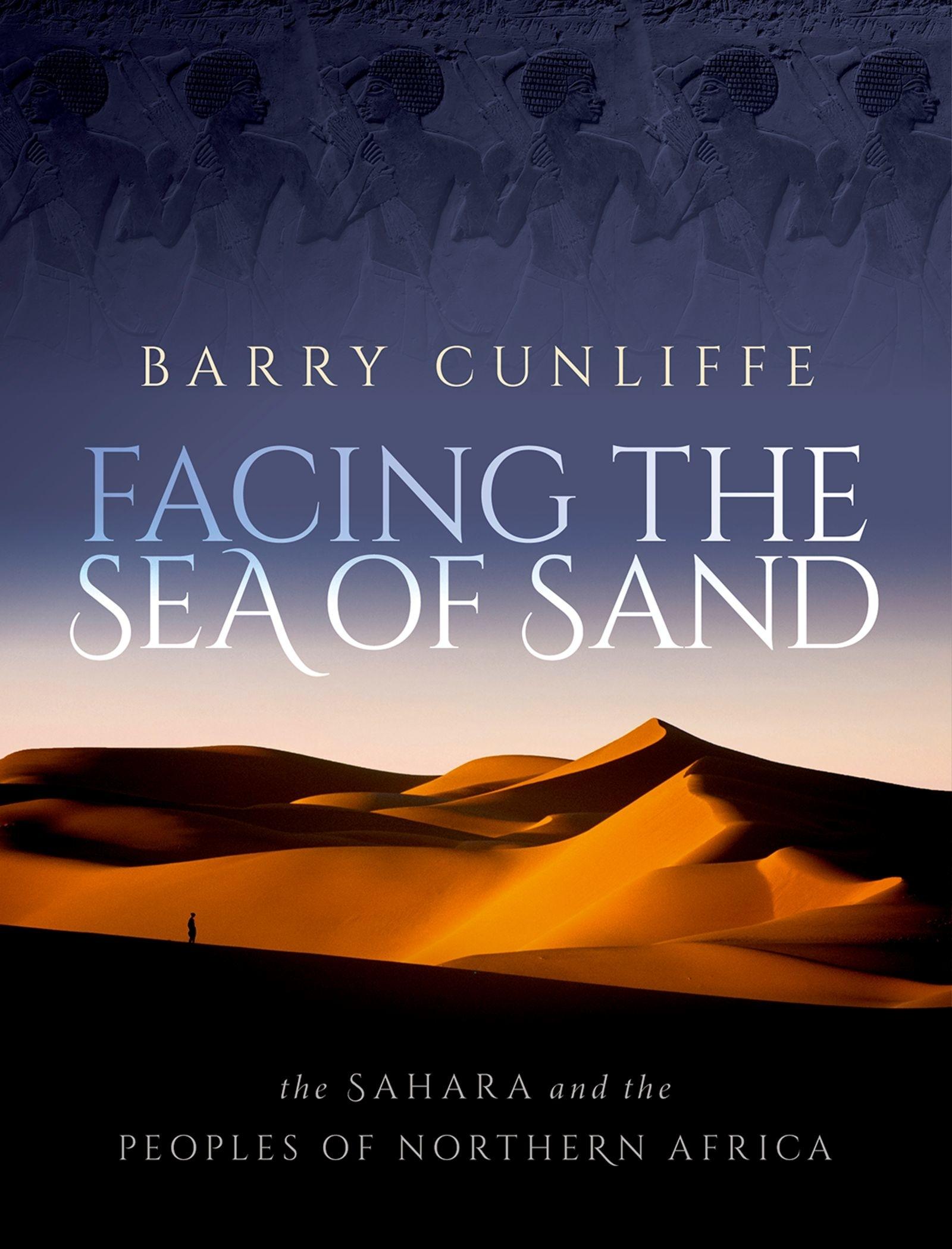

The Desert

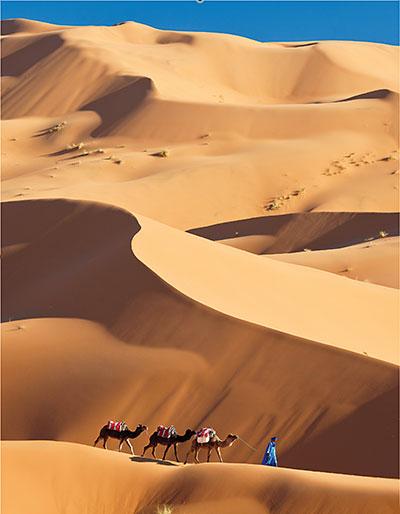

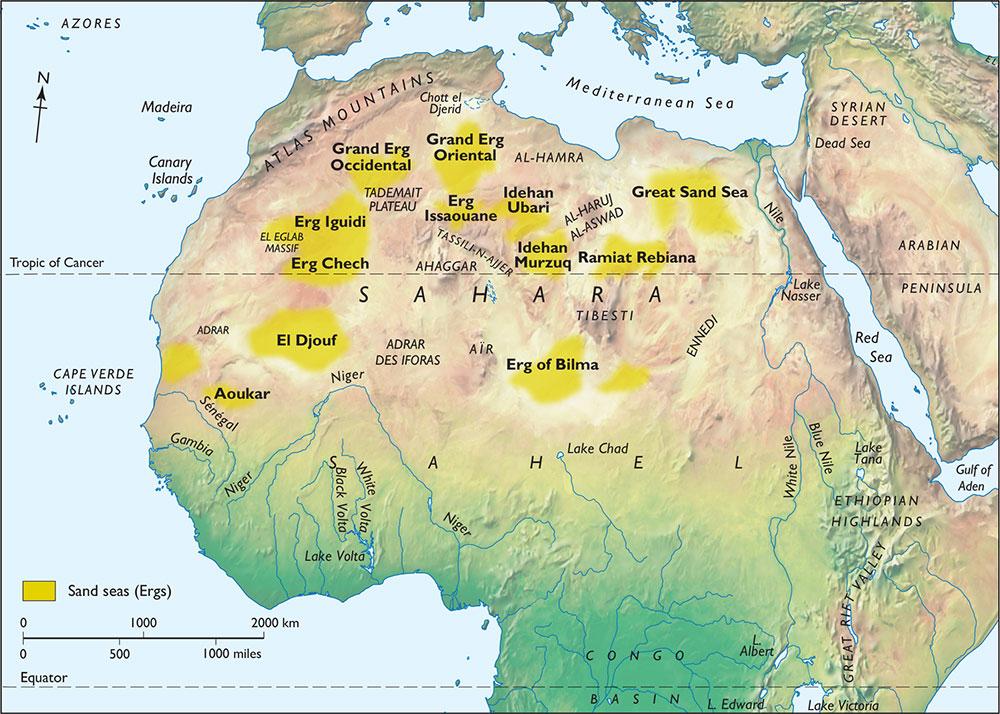

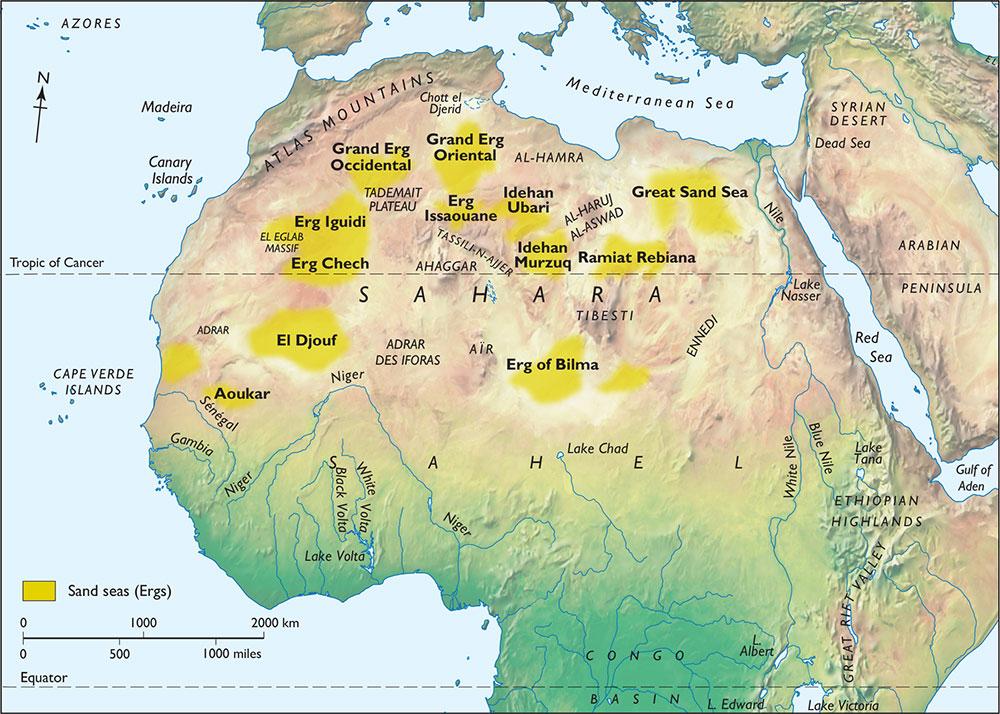

In its present state the Sahara is the largest hot desert in the world, a band of largely desolate, barren waste 1,800 kilometres wide, stretching for 6,000 kilometres across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. In Arabic sahra, meaning desert, was used as a proper noun for the first time by the Egyptian historian Ibn Abd alHakam in the ninth century AD.

For the most part the desert is of comparatively low relief, seldom above 1,000 metres, and is composed of rocky plateaux (hamada), stretching away in an endless monotony, some areas polished by the wind, others (regs) strewn with loose rock and gravel. There are also vast seas of sand (ergs), which in places can be whipped by the wind into dunes 200 metres high. But within all this dun-coloured desolation arise ranges of spectacular mountains where rainfall is sufficient to allow plants and animals, including humans, to survive. The mountain massifs have very different characters. The Aïr

Mountains of Niger are composed largely of granite, creating a plateau 500–900 metres high with high domes rising to 1,800 metres. The Ahaggar Mountains of southern Algeria are composed of metamorphic rocks once penetrated by volcanoes. Subsequent erosion of the cones of soft ash has left the central plugs of lava standing gaunt in the austere landscape up to a height of 2,900 metres. Here rains are sufficient to support a relict wildlife including cheetahs and, until recently, West African crocodiles. In southeastern Algeria the Tassili-n-Ajjer (Plateau of Rivers) is different again, a sandstone upland rising to 2,100 metres dissected, as its name suggests, by river valleys. The highest of the Sahara’s mountains are the Tibesti of northern Chad, rising to the peak of Emi Koussi at 3,445 metres. Much of the range is volcanic, with domes of lava and old craters, one 20 kilometres across, carved by deep canyons created by the intermittent rainfall.

1.8 The Sahara desert is far from uniform. There are mountain ranges sufficiently high to attract precipitation and huge areas of sand sculpted into everchanging dunes by the wind. Between, much of it is barren, rocky lowlands.