Hercules Seneca

Edited with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary by

A. J. BOYLE

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© A. J. Boyle 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022944326

ISBN 978–0–19–885694–8

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Athena, Helen, and James

Let Hercules himself do what he may, The cat will mew, and dog will have his day.

Shakespeare, Hamlet V.i.286–7

Preface

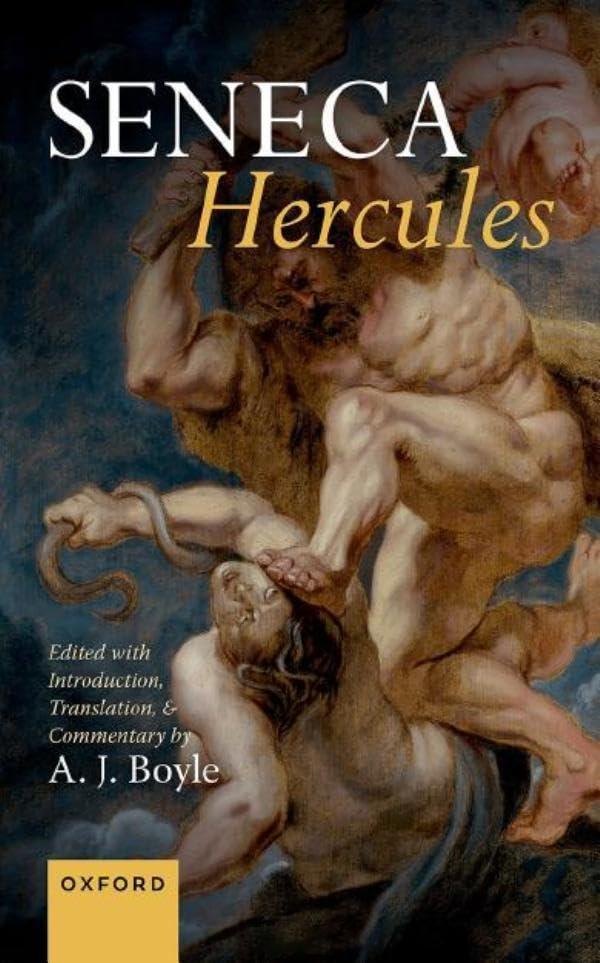

The painting featured on the front cover of this book, ‘Hercules as Heroic Virtue Overcoming Discord’ (c.1632–3: MFA, Boston, Accession No. 47.1543), is a study for a panel on the Rubens ceiling of the Banqueting House, Whitehall, London, the only part of the Whitehall Palace inhabited by the Stuart monarchs that still survives today. The panel was one of nine paintings celebrating the reign of James I, commissioned from Rubens in 1629 by Charles I two decades before the latter’s execution. To twenty-first-century viewers of the panel and presumably to some members of the Carolingian court the question posed by the panel is or was ‘What is heroic virtue?’ That question is at the heart of Seneca’s Hercules, and Rubens’s presentation of that question through the image of violence inflicted on the body of a woman by Hercules’ club will be matched in the action of Seneca’s play. There was also an ironic match in history. Several Roman political figures, including Sulla, Pompey, Antony, Caligula, Domitian, Commodus, and Maximian, associated themselves with Hercules for the purpose of political selffashioning; so, too, the Florentine Medici and a plethora of early modern European rulers. The English monarch, Charles I, through this panel associated the Herculean myth with himself—only to meet, like most of the named Roman predecessors, with premature death. To unite Charles’s death with Seneca’s play, the great English poet of the mid seventeenth century, John Milton, cited Hercules’ sentiment at Herc. 922–4 to describe the king’s beheading (see Comm. ad 918–24). A similarly bloody end was to befall Seneca’s pupil and imperial master, Nero, who, as fate would have it, sang in the last years of his reign many tragic roles, including that of ‘Hercules the Mad’. The play edited, translated, and commented upon in this book was subject to an unusual degree of imbrication with both literature and history. Seneca’s Hercules (entitled thus in the ‘Codex Etruscus’, but Hercules Furens in several branches of the A MS tradition), has been dated plausibly to c.53–4 ce , at the intersection of the Claudian and Neronian principates. It appears almost certainly to have been written between Agamemnon and Thyestes. Foreshadowed perhaps by the final choral ode of Agamemnon on Hercules’ birth and ‘labours’, the play prefigures—through its dramatization of the sacrificial slaying of children—the more elaborate description of this

Preface

horror in Thyestes. Hercules is a complex and important drama, examining a complex and important cultural figure, the legendary founder of one of Rome’s earliest religious monuments (the Ara Maxima), occupier of several of the city’s shrines, and a major Roman paradigm of human achievement: monster-slayer, pacifier, and civilizer, for whom divinity was part reward, part birth-right, and who was explicitly associated with imminently ‘divine’ Roman emperors from Augustus onwards (Virg. Aen. 6.791–803, Hor. Carm 3.3.9–12, 4.5.33–6). But Hercules was a model, too (Hor. Carm. 1.3.36), of hybristic ambition, a murderous thug and violent transgressor of boundaries, whether provided by gods, nature, or humankind. Celebrated and castigated in ancient myth, religion, literature, history, and art, Heracles/Hercules was also a significant figure in philosophy from the fifth century bce onwards (Prodicus), becoming prominent in Cynicism and Stoicism, where his violence was sometimes taken as a force for good. Seneca himself exploits the paradoxical status of Hercules. In his philosophical works he proclaims him ‘unvanquished by adversity, a despiser of pleasure and conqueror of every terror’ (De Constantia Sapientis 2.1) and ‘an enemy of the wicked, defender of the good, and bringer of peace to land and sea’ (De Beneficiis 1.13.3); yet he focuses in his tragedy, Hercules, on the hero’s bloody killing not only of a violent enemy but of his own innocent children and wife.

That focus generates a tragedy of great theatrical, literary, social, and cultural value. Among the major issues explored: violence and its psychological, familial, and social consequences; the imperatives of family and of self; sanity and madness, identity and place; the possibility of moral redemption; the human longing for immortality; the empire of death. The presentation of Hercules’ mind is at the heart of the play. For some scholars partial illumination may be found in modern discussions of PTSD, ‘combat trauma’, and ‘family annihilators’. One central issue, of which both dramatic action and dramatic script constitute a prolonged examination, is the one mentioned at the start of this preface: the nature of ‘heroic virtue’, indeed the nature of uirtus, ‘virtue’, simpliciter, the (ideal) property or properties of being a uir, a ‘man’—a core value of Roman Stoicism and of Roman elite male identity. Hercules is very much a Roman play, perhaps the most Roman of the Senecan ‘eight’.

Hercules is also potent drama. Seneca presumably learned from Euripides the thematic and dramatic power of casting the same actor as the violent, tyrannical Lycus and as his conqueror Hercules. Hercules is a play with strong theatrical qualities throughout, in which the choral lyrics are not only among the most moving and intellectually engaging in Senecan tragedy (even Eliot praised the fourth ode’s final lines), but are always dramatically

functional. The tragedy features a fiery, monumental god-prologue (the only one in Senecan tragedy), impassioned prayers and speeches, meditative entrance soliloquies/monologues, trenchant dialogue (with some quick-fire stichomythia and antilabe), a failed wooing scene with an impressive afterlife in Tudor drama, an innovative quasi-messenger episode, involving a lengthy ecphrastic dialogue on the world of death and a climactic narrative of Hercules’ abduction of the hell-hound, Cerberus. It features, too, a spectacular ‘madness scene’, in which wife and children are slaughtered, and an emotionally turbulent, non-violent finale, a spectaculum perhaps ‘worthy of a god’ (De Prouidentia 2.8), in which the instinct for self-punitive suicide is thwarted by the claims of kinship and the acceptance of intolerable suffering—suffering juxtaposed with an apparent offer of moral cleansing and redemption. The play had a substantial influence on early modern European literature and drama and beyond. Apparent debtors include: Garnier, La Taille, Legge, Rare Triumphs of Love and Fortune, Kyd, Hughes, Marlowe, Greene, Shakespeare, Locrine, Marston, Fulke Greville, Chapman, Jonson, Prévost, Rotrou, L’Héritier de Nouvelon, Milton, Racine, Lee, Young, Voltaire, Glover. Eliot’s twentieth-century The Waste Land and Marina seem also to manifest a debt, as do several twentieth- and twenty-first-century works on the Heracles/Hercules theme (see Introd. §VIII).

But despite all this—and notwithstanding earlier, distinguished editions of the play (see below)—Seneca’s Hercules has been relatively understudied in modern criticism and scholarship, and has been performed rarely even in translation or adaptation. There is but one ‘recent’ performance reported on the website of the Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama (APGRD): at the Théâtre de Gérard Philipe de Saint-Denis in Paris 1996. The same website does not, however, record a vigorous, PTSD-oriented adaptation of Seneca’s Hercules Furens in Los Angeles in 2011 and 2013.

The present edition of Seneca’s Hercules offers a substantial introduction, a new Latin text (with over eighty different readings and many other changes from the Zwierlein Oxford text of 1986: see pp. 262–5 below), an English verse translation designed for both performance and serious study, and a detailed commentary on the play which is exegetic, analytic, and interpretative. The format is identical to that which I adopted in my editions of Octavia (Oxford, 2008), Oedipus (Oxford, 2011), Medea (Oxford, 2014), Thyestes (Oxford, 2017), and Agamemnon (Oxford, 2019). The aim again has been to elucidate the text dramatically as well as philologically, and to locate the play firmly in its contemporary historical and cultural context and in the ensuing literary and theatrical tradition. I am aware of the interpretative

nature of all aspects, including the philological, of any modern reconstruction of an ancient text, and have endeavoured to provide the grounds for my textual, literary, and cultural judgements. It is hoped that the resulting edition may prove useful to drama students, to Latin students at every stage of the language, to professional scholars of Classics, Theatre, and Comparative Literature—and to anyone interested in the cultural dynamics of literary reception and the interplay of theatre and history. The aim has been to encourage a greater and more intense engagement with Seneca’s play at the scholarly, critical, and theatrical levels.

There are many debts to acknowledge. Like all new editions of classical texts the present one owes much to previous scholarship. There are several editions and translations of Seneca’s Hercules to which I am indebted, as will be clear from the Commentary, but I want specifically to name the distinguished, large-scale editions of Fitch (1987a) and Billerbeck (1999a), to the fine scholarship of which I have constantly turned in moments of aporia. My debts to them go beyond the many passages in the Introduction and Commentary where their names may be found. Of much older works I have found the early fourteenth-century commentary of Nicholas Trevet and the early seventeenth-century edition of Thomas Farnaby interesting and helpful. Most of this book was written and reviewed in the long years of the Covid 19 pandemic, during which much of the professoriat ‘languished’. I am deeply appreciative of the unsuppressed energy and commitment exhibited by my readers, friends, colleagues, and students in their unstinting efforts to help me produce a better book. I owe a special debt to five friends and colleagues who read earlier drafts of this book and offered advice: Joseph Smith (San Diego State University) commented critically (often acerbically) and in detail on a preliminary draft of the whole book and saved me from both omissions and errors; Hannah Čulík-Baird (University of California, Los Angeles), John Henderson (King’s College, Cambridge), Stefano Rebeggiani (University of Southern California), and Christopher Trinacty (Oberlin College) commented on later versions with enviable insight and acuity. I thank them most sincerely. My principal research assistants on the project, Melina McClure and Madeline Thayer (both USC), performed text, translation, and commentary proofing and other duties with admirable expertise and acumen. Thanks are also due to several other friends and colleagues who helped in diverse ways, including Peter Davis (Universities of Tasmania and Adelaide), Lucas Herchenroeder (USC), Sara Lindheim (University of California, Santa Barbara), Gesine Manuwald (University College London), Robert Morstein-Marx (UCSB), Emma Stafford (Leeds

University), and Ryan Prijic, the USC Classics Department’s administrator, who was unfailing in response to my research and printing needs. Erica Bexley (Durham University) kindly sent me the proofs of her 2022 book on Senecan drama in advance of publication. Finally two graduate seminars at USC (Spring 2020, Fall 2021) provided a fertile, critical context in which to explore Seneca’s Hercules and its rich semiotics. I thank the students in those classes for two pleasurable and intellectually illuminating semesters, which shone the more brightly because of the dark clouds of Covid encompassing them.

I should again like to record my gratitude to the Classics editorial staff at the Oxford University Press, who have been a pleasure to work with on this and earlier commentaries. Responsibility for mistakes of fact and judgement stays firmly with me. I should also like to thank Routledge for permission to include rewritten material from my Tragic Seneca (London, 1997) and Roman Tragedy (London, 2006) and Francis Cairns Publications for permission to include material from my Seneca’s Troades (Leeds, 1994) in various parts of the Introduction. I have not hesitated to make use, where appropriate (especially in the Introduction and Commentary), of material from my previous OUP Senecan editions. Sections I–IV, IX, and X of the Introduction are updated and recalibrated versions of the similarly numbered sections in earlier Introductions. Finally profound gratitude is due to the University of Southern California, whose many years of institutional and collegial support have assisted immeasurably. The book is dedicated to three people without whom it could not have been written.

A.J.B.

USC, Los Angeles Nones of March 2022

INTRODUCTION

I. Seneca and Rome

Quasi in tutte le sue tragedie, egli avanzò (per quanto a me ne paia) nella prudenza, nella gravità, nel decoro, nella maiestà, nelle sentenze, tutti i Greci che scrissero mai.

In almost all his tragedies he surpassed (in my opinion) in prudence, in gravity, in decorum, in majesty, in epigrams, all the Greeks who ever wrote.

Giraldi Cintio Discorsi (1543)

Life and Works

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was born in 1 bce or shortly before in Corduba (modern Córdoba or Cordova) in southern Spain, the second of three sons to Helvia, the mater optima (‘best of mothers’) of Seneca’s ‘Consolation’ from exile, and the cultivated equestrian, Annaeus Seneca (c.55 bce to c.40 ce praenomen probably also Lucius), author of a lost history of Rome and surviving but badly mutilated works on Roman declamation, Controuersiae and Suasoriae. The youngest son, Mela, became the father of the epic poet Lucan. Brought to Rome as a young child and given the standard ‘elite’ education in language, poetry and rhetoric, Seneca had become by the early years of Tiberius’ principate (14–37 ce ), while still in adolescence, a passionate devotee of philosophy. He studied Stoicism with the philosopher Attalus, but was drawn also to Sextianism, a local, ascetic form of Stoic-Pythagoreanism with a strong commitment to vegetarianism, taught by the philosophers Papirius Fabianus and Sotion. Before long he had been dissuaded from Sextian practices by his father (Ep. Mor. 108.17–22). During his youth and throughout his life Seneca suffered from a tubercular condition, and was impelled on one occasion to contemplate suicide when he despaired of recovery. He records that only the thought of the suffering he would have caused his father prevented his death (Ep. Mor. 78.1–2).

Ill health presumably delayed the start of his political career, as did a substantial period of convalescence in Egypt during the twenties under the care of his maternal aunt. He returned to Rome from Egypt in 31 ce (surviving a shipwreck in which his uncle died), and entered the senate via the

quaestorship shortly afterwards, as did his elder brother, Gallio. By the beginning of Claudius’ principate (41 ce ) he had also held the aedileship and the office of tribune of the people (tribunus plebis). During the thirties, too, he married (although whether it was to his wife of later years who survived him, Pompeia Paulina, is uncertain), and he achieved such fame as a public speaker as to arouse the attention and jealousy of the emperor Gaius, better known as Caligula (Suet. Gai. 53.2, Dio 59.19.7–8). By the late thirties Seneca was clearly moving in the circle of princes, among ‘that tiny group of men on which there bore down, night and day, the concentric pressure of a monstrous weight, the post-Augustan empire’.1 His presence in high places was initially short-lived. He survived Caligula’s brief principate (37–41 ce ) only to be exiled to Corsica in the first year of Claudius’ reign (41 ce ). The charge was adultery with Caligula’s sister, Julia Livilla, brought (according to Dio: 60.8.5) by the new empress, Claudius’ young wife, Messalina.

Seneca’s exile came at a time of great personal distress (both his father and his son had recently died: Helu. 2.4–5), and, despite pleas for imperial clemency (see esp. Pol. 13.2ff.), lasted eight tedious years. During those years Rome’s dominion expanded. The emperor’s power depended upon his control of Rome’s army and, during Seneca’s exile, that army was put to work, acquiring five new provinces for the empire (two Mauretanias, Lycia, Britain, and Thrace) in a period of rapid imperial expansion. In 48 ce Messalina was executed after her treasonous ‘wedding’ to the consul-elect, Gaius Silius. In the following year Seneca was recalled to Rome by Claudius’ new wife, Agrippina (great-granddaughter of Augustus, another of Caligula’s sisters and Claudius’ niece—Seneca was later accused of having been her lover: Tac. Ann. 13.42.5, Dio 61.10.1), and was designated praetor for 50 ce . His literary and philosophical reputation was now well established (Tac. Ann. 12.8.3), and, towards the end of 49 (Tac. Ann. 53.2) or in 50 ce (following Claudius’ adoption of Nero: Suet. Nero 7.1), he was appointed Nero’s tutor. This appointment not only placed Seneca again at the centre of the Roman world, but brought him immense power and influence when Agrippina (allegedly) poisoned her emperor-husband and Nero acceded to the throne (54 ce ).

Throughout the early part of Nero’s principate Seneca (suffect consul probably in 56 ce )2 and Afranius Burrus, the commander of the praetorian guard, acted as the chief ministers of the young emperor, whose speeches Seneca initially wrote, but whom they were increasingly unable to control.

1 Herington (1966: 429). For the Cinthio citation in the epigraph, see e.g. Crocetti (1973: 184).

2 On the date of Seneca’s suffect consulship, see Griffin (1976: 73–4).

During this period Seneca became extremely wealthy. Nero’s matricide, however, in 59 ce , to which it seems likely that neither Seneca nor Burrus were initially privy,3 but for which Seneca wrote a post factum justification (Tac. Ann. 14.11), signalled a weakening of the ministers’ power. When Burrus died (perhaps poisoned) in 62 ce , Seneca, although his requests to quit public life were officially rejected by Nero (Tac. Ann. 14.53–6, 15.45.3), went into semi-retirement.4 In 65 ce he was accused of involvement in the Pisonian conspiracy against Nero and was ordered to kill himself. This he did, leaving to his friends ‘his one remaining possession and his best— the pattern of his life (imaginem uitae suae)’ (Tac. Ann. 15.62.1).

Apart from a body of epigrams (many of which are certainly spurious) and a prose-verse Menippean satire on Claudius’ deification, Apocolocyntosis (the ‘Pumpkinification’), Seneca’s extant writings can conveniently be divided into the prose works and the tragedies. The prose works comprise Naturales Quaestiones (‘Natural Questions’), the Dialogi (twelve books of so-called ‘Dialogues’, which include the three books of De Ira, ‘On Anger’), De Clementia (‘On Clemency’—addressed to Nero on his accession), De Beneficiis (‘On Benefits’), and Epistulae Morales (‘Moral Epistles’—addressed to his friend Lucilius). Lost works include a biography of Seneca the Elder, speeches, ethnographical and geographical treatises on India and Egypt, treatises on physics, and several philosophical works (among them De Amicitia, ‘On Friendship’, De Matrimonio, ‘On Marriage’, and De Immatura Morte, ‘On Premature Death’). The prose works focus on practical ethics and the progress to virtue. They are infused to a greater or lesser extent with Stoic ideas concerning fate, god, virtue, wisdom, reason, endurance, self-sufficiency and true friendship, and are filled with condemnation of the world of wealth and power (to which Seneca belonged) and contempt for the fear of death. Central to their conception of the world is the Stoic belief in divine reason/ratio as ‘the governing principle of the rational, living and providentially ordained universe’, in which ‘only the Stoic sage (sapiens) . . . can achieve virtue . . . and live the truly happy life’.5 Seneca’s philosophical writings cover a considerable period of time—from the thirties ce to their author’s death. Among the earliest to be written was Consolatio ad Marciam, composed under Caligula (37–41 ce ); among the last were Naturales Quaestiones and Epistulae Morales, written during the years of Seneca’s ‘retirement’ (62–5 ce ).

3 See Barrett (1996: 189).

4 Tac. Ann. 14.52: mors Burri infregit Senecae potentiam,‘Burrus’ death shattered Seneca’s power’.

5 Williams (2003: 4).

Ten extant plays have come down under Seneca’s name, eight of which are agreed to have been written by him: Hercules, Troades, Phoenissae, Medea, Phaedra, Oedipus, Agamemnon, and Thyestes. Such are their titles in the E branch of the MS tradition. In the A branch Hercules, Troades, Phoenissae, and Phaedra are respectively entitled Hercules Furens (still in general use), Tros, Thebais, and Hippolytus. Of the eight only Phoenissae, which lacks choral odes, is (probably) incomplete. The remaining two plays are a tragedy, Hercules Oetaeus, and the tragic fabula praetexta, Octavia. The former is almost twice as long as the average Senecan play and seems to many—on stylistic, linguistic, thematic, and dramaturgical grounds— non-Senecan.6 The latter, in which Seneca appears as a character and which seems to refer to events which took place after Seneca’s death, is missing from E and is certainly not by Seneca.7 Each of the eight tragedies is marked by dramatic features which were to influence Renaissance drama: vivid and powerful declamatory and lyric verse, psychological insight, highly effective staging, an intellectually demanding verbal and conceptual framework, and a precocious preoccupation with theatricality and theatricalization. Composed presumably in the second half of Seneca’s life, the plays cannot be dated with certainty. Many commentators accept a terminus ante quem of late 54 ce for Hercules on the grounds that Apocolocyntosis (probably dated to November/December 54 ce )8 seems to parody it. And, though the parody theory is clearly not certain, I have adopted a working hypothesis of a date of c.53–4 ce for this play. The earliest unambiguous reference to any of Seneca’s plays is the Agamemnon graffito from Pompeii, of uncertain date but obviously before the catastrophe of 79 ce .9 The next is a citation from Medea by Quintilian, writing a generation after Seneca’s death (Inst. 9.2.8; see also Inst. 8.3.31). Seneca, although he refers to tragedy and the theatre in his prose works, makes no mention there of his own plays. Some commentators assign them to the period of exile on Corsica (41–9 ce ) during the principate of Claudius; others regard it as more likely that their composition, like that of the prose works, was spread over a considerable period of time. The important stylometric study of Fitch not only supports the latter position but attempts to break the plays into three chronologically consecutive groups: (i) Agamemnon, Phaedra, Oedipus; (ii) Hercules, Troades,

6 See Boyle (2006: 221–3).

7 It is most plausibly dated to the early Flavian period: see Boyle (2008: xiii–xvi).

8 Griffin (1976: 129).

9 CIL iv. Suppl. 2.6698: idai cernu nemura, ‘I see the groves of Ida’ = Ag. 730.

Medea; (iii) Thyestes, Phoenissae.10 The groupings and implied chronology are by no means agreed, but most modern scholars would probably accept that on stylometric, dramatic, and other grounds Thyestes and Phoenissae are Seneca’s final extant tragedies. The present editor also accepts that these final tragedies are probably Neronian.11

The relationship between the tragedies and the prose works continues to be debated. Although the tragedies are not referred to in the prose works, they are still sometimes regarded as the product of Stoic convictions and the dramatization of a Stoic world-view. Certainly they abound in Stoic language and moral ideas (many of them evident in the prose works), and their preoccupation with fate, with human emotion, psychology, and action, and the destructive consequences of passion, especially anger, is deeply indebted to the Stoic tradition.12 But this Stoicism is no ideological clothing but part of the dramatic and critical texture of the plays.13 And to many, including the present editor, the world-view of most of the plays is decidedly unStoic, even an inversion of Stoicism, cardinal principles of which are critically exhibited within a different, more disturbing vision.14

Julio-Claudian Rome

Although Seneca was born only a few years after Horace’s death he inhabited a different world. Horace (65–8 bce ) lived through Rome’s bloody transformation from republic to empire; he fought with Brutus and Cassius at

10 Fitch (1981).

11 A Tiberian or Caligulan date for Seneca’s plays, though theoretically possible, is most unlikely, given Tiberius’ hostility to the theatre and reported execution of at least two tragic dramatists and the ‘volatile and dangerous atmosphere’ of Caligulan Rome. Several Senecan tragedies are perhaps to be assigned to the Claudian principate. Under Claudius imperial support for the dramatic festivals came without the oppressive control of a Caligula. The consular tragedian, Pomponius Secundus, with whom Seneca debated tragic language, was active in Claudian Rome. The stylistic differences, however, noted by Fitch, suggest a considerable gap between the earlier plays and Thyestes and Phoenissae (perhaps even late Neronian: see Boyle 2017: xix n. 11).

12 See e.g. De Ira (for an analysis, see Boyle 2019: lvii–lxiv). For Stoic language and ideas in Hercules, see Comm. ad 162–3.

13 Cf. Trinacty (2015: 38): ‘Stoicism is not the key by which one can unlock the single meaning of Seneca’s tragedies but rather one of many keys that help us to uncover the myriad associations that these works suggest.’

14 The question of the relationship between Seneca the philosopher and Seneca the tragedian has tended to privilege the former. But what is clear is that Seneca’s philosophical mode is itself essentially theatrical. His letters and ‘dialogues’ are filled with scripted voices (of others and himself) and his prime philosophical position is that of spectator/audience—spectator of others and of himself. Senecan philosophy ‘stages ethics’ (cf. Gunderson 2015: 105).

Philippi (42 bce ). Seneca never knew the republic. Born under Augustus and committing suicide three years before Nero’s similar fate, he lived through and was encompassed by the Julio-Claudian principate. Throughout Seneca’s lifetime—despite the preservation of Rome’s political, legal, moral, social, and religious forms—power resided essentially in one man, the princeps or emperor, sometimes (as in the case of Caligula) a vicious psychopath. Political and personal freedom were nullities. Material prosperity increased (for all Romans, not simply for the upper classes), but for the social elite the loss of political power brought with it a crisis of collective and individual identity. In Rome and particularly at the court itself, on which the pressure of empire bore, nothing and no one seemed secure, the Roman world’s controlling forms used, abused, and nullified by the princeps’ power. Servility, hypocrisy, corrupting power indexed this Julio-Claudian world.

Or so at least the ancient historians would have us believe, most notably Tacitus, whose Annales, written in the first decades of the second century ce , documents the hatreds, fears, lusts, cowardice, self-interest, selfabasement, abnormal cruelty, extravagant vice, violent death, the inversion and perversion of Rome’s efforming values and institutions—and, more rarely, the nobility and heroism—which to his mind constituted the early imperial court. Tacitus’ indictment of the Julio-Claudian principate is as clear as it is persuasive. In the case of Nero, for example, the emperor’s debauchery (Ann. 15.37), fratricide (Ann. 13.16–18), matricide (Ann. 14.8–10), uxoricide/sororicide (Ann. 14.60–4) are melodramatically portrayed. Witness the murder of Octavia, sister, step-sister, and ex-wife in 62 ce (Ann. 14.64):

ac puella uicesimo aetatis anno inter centuriones et milites, praesagio malorum iam uitae exempta, nondum tamen morte adquiescebat. paucis dehinc interiectis diebus mori iubetur, cum iam uiduam se et tantum sororem testaretur communisque Germanicos et postremo Agrippinae nomen cieret, qua incolumi infelix quidem matrimonium sed sine exitio pertulisset. restringitur uinclis uenaeque eius per omnis artus exsoluuntur. et quia pressus pauore sanguis tardius labebatur praeferuidi balnei uapore enecatur. additurque atrocior saeuitia, quod caput amputatum latumque in urbem Poppaea uidit.

So the girl, in her twentieth year, in the midst of centurions and soldiers, already cut off from life by the foreknowledge of suffering, still lacked the

quietude of death. After a few days’ interval she is ordered to die, although she pleaded that she was now an ex-wife and only a sister and evoked the shared lineage of the Germanici and lastly the name of Agrippina, under whom, while she survived, she had endured an unhappy but non-fatal marriage. She is bound, and her veins are opened in every limb; then, because her blood flowed too slowly, checked by fear, she is suffocated with the steam of a boiling bath. There is an additional, more savage cruelty: her head was cut off and taken to Rome, where it was viewed by Poppaea.

And the corollary of imperial vice and power: the black farce of Roman servility. Witness the city’s ‘joy’ in the aftermath of the failed conspiracy of Piso in 65 ce (Ann. 15.71):

sed compleri interim urbs funeribus, Capitolium uictimis. alius filio, fratre alius aut propinquo aut amico interfectis, agere grates deis, ornare lauru domum, genua ipsius aduolui et dextram osculis fatigare.

Meanwhile funerals abounded in the city, thank-offerings on the Capitol. Men who had lost a son or brother or relative or friend gave thanks to the gods, bedecked their houses with laurel, fell at the feet of Nero and kissed his hand incessantly.

Indeed the ‘farce’ of Roman aristocratic behaviour, its theatricality, is a major focus of Tacitus’ vision of the Julio-Claudian principate.15 Roman political life had always been theatrical.16 To the author of Annales, however, imperial Rome was the unacceptable apogee of earlier political theatre, a profoundly histrionic culture, in which role-playing had become the dominant behavioural mode and acting the emblematic metaphor. In his account of the principates of Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero the distinction between play and public reality disappears. Nero’s initial ‘mimicries of sorrow’ (tristia imitamenta, Ann. 13.4), for example, at the funeral of his adoptive father, Claudius, led into insistent attention not only to the emperor’s appearances on the stage but to the political and social

15 Tacitus is not alone. For self-dramatization and theatricality at the Caligulan court, for example, see Philo Leg. 79, 93–7, 111, Suet. Gaius 11, 15.1, 31, 36.1, 54.1, 55.1, Dio 59.5.5, 26.6–8, 29.6. On the theatricality of early imperial Rome, see Rudich (1993: xvii–xxxiv), Bartsch (1994: passim), Boyle (2006: 160–88).

16 See Boyle (2006: 3–23). On theatricality in the late republic, note Cicero’s analysis of the individual in terms of four personae: Off. 1.107–15.

imperatives of role-playing in the theatricalized world of imperial Rome, where citizens mourn what they welcome (Ann. 16.7), applaud what they grieve (Ann. 14.15), offer thanksgivings for monstrous murder (Ann. 14.59, 64), and celebrate triumphs for national humiliation or horrendous and impious sin (Ann. 15.18, 14.12–13). In the narrative of Nero’s notorious matricide there is a focus not only on role-play and sets, but props, dialogue, stage directions, and tragic structure (Ann. 14.1–13). The theatrics are overt and highly allusive. Agrippina’s ‘final words’ even draw Seneca’s Jocasta into the text, as Nero’s mother reveals herself as the theatrical, incestuous figure she had always been.17

Nor does Nero’s death end the political theatre. The description in Tacitus’ Historiae of the people’s reaction to Otho’s conspiracy in 69 ce or to the bloody fighting between the Vitellian and Flavian armies at the end of the same year parades the theatricality of their behaviour (Hist. 1.32 and 3.83):

uniuersa iam plebs Palatium implebat mixtis seruitiis et dissono clamore caedem Othonis et coniuratorum exitium poscentium ut si circo aut theatro ludicrum aliquod postularent. neque illis iudicium aut ueritas, quippe eodem die diuersa pari certamine postulaturis, sed tradito more quemcumque principem adulandi licentia adclamationum et studiis inanibus.

The whole populace together with slaves now filled the palace, demanding with raucous cries the death of Otho and the destruction of the conspirators as if they were calling for some show in the circus or theatre. They had neither sense nor sincerity (for on the same day they would clamour for the opposite with equal passion), but followed the convention of flattering whoever was emperor with unlimited applause and empty enthusiasm.

aderat pugnantibus spectator populus utque in ludicro certamine hos rursus illos clamore et plausu fouebat.

The people attended the fighting as the audience for a show, and, as with a stage battle, supported now this side, now that with shouts and applause.

Seneca’s prose works provide contemporary testimony of this theatricalized world.18 Nature herself is said to have created us as ‘spectators for the great

17 See Boyle (2011: lxxxi–lxxxii).

18 For the many allusions in Seneca’s prose works to ‘le théâtre et les spectacles’, see Aygon (2016: 13–140).

spectacle of reality’ (spectatores nos tantis rerum spectaculis, Ot. 5.3), Cato is paraded as a moral ‘spectacle’ (spectaculum, Prou. 2.9ff.), Lucilius is exhorted to do everything ‘as if before a spectator’ (tamquam spectet aliquis, Ep. Mor. 25.5; cf. Ep. Mor. 11.8ff.), ‘human life’ is declared ‘a mime-drama, which assigns parts for us to play badly’ (hic humanae uitae mimus, qui nobis partes quas male agamus adsignat, Ep. Mor. 80.7). Though the Stoic goal is the single part, ‘we continually change our mask (personam) and put on one the very opposite of that we have discarded’ (Ep. Mor. 120.22). Indeed Seneca’s addressees are sometimes specifically instructed to ‘change masks’ (muta personam, Marc. 6.1), or to stop performing: for ‘ambition, decadence, dissipation require a stage’ (ambitio et luxuria et impotentia scaenam desiderant, Ep. Mor. 94.71). In life, as in a play (quomodo fabula, sic uita), what matters is not the length of the acting but its quality (Ep. Mor. 77.20). Stoicism as a philosophy abounds in theatrical tropes, as both Greek Stoic writings and Seneca’s own Epistulae Morales testify,19 demanding from its heroes a capacity for dramatic display and exemplary performance. And Stoicism was a philosophy of regular choice for the Roman imperial elite. It was not primarily Stoicism, however, which turned Rome’s male elite into actors. Few educated Romans would have found either theatrical selfdisplay or a multiplicity of personae difficult. On the contrary, rhetorical training in declamation (declamatio), including mastery of the ‘persuasionspeech’ or suasoria, which required diverse and sustained role-playing, gave to contemporary Romans not only the ability to enter into the psychic structure of another, i.e. ‘psychic mobility’ or ‘empathy’,20 but the improvizational skills required to create a persona at will.21 As works such as Petronius’ Satyricon exhibit, the cultural and educative system had generated a world of actors. So, too, the political system. The younger Pliny’s depiction of Nero as ‘stage-emperor’, scaenicus imperator (Pan. 46.4), catches only one aspect of the theatricality of the times. Nero’s public appearances onstage late in his principate seem to have been designed in part to parade his familial crimes as acts of theatre. Among the tragic roles which he is reported by Suetonius (Nero 21.2–3) as singing, sometimes ‘wearing the tragic mask’ (personatus), were ‘Niobe’, ‘Canace in Labour’ (Canace Parturiens), ‘Orestes the Matricide’

19 See e.g. Ep. Mor. 74.7, 76.31, 115.14ff.; also Marc. 10.1. On Stoicism and self-dramatization, see Rosenmeyer (1989: 47ff.).

20 Terms used by the sociologist Lerner, quoted by Greenblatt (1980: 224ff.), in his detailed discussion of the Renaissance capacity for ‘improvisation’.

21 For this ‘rhetorical fashioning of the self and others’ in Roman education, see Bloomer (1997: 59) and also §III, 33–8 below.

(Orestes Matricida), ‘Oedipus Blinded’ (Oedipus Excaecatus), and ‘Mad Hercules’ (Hercules Insanus). Juvenal (8.228–9) adds the roles of Thyestes, Antigone, and Melannipe, and Dio (62.9.4, 22.6) those of Thyestes and Alcmaeon.22 That some of the masks he wore were made to resemble either his own features and those of women with whom he was in love (Suet. Nero 21.3, Dio 62.9.5) further confounded the distinction between illusion and reality, between Rome’s theatre and Rome’s world. But Nero’s stage performances made not only himself but the audience an actor and object of spectatorial attention.23 Degrees of enthusiasm, adverse responses, indifference, and absence were noted in the audience by Nero’s claques and military staff (Tac. Ann. 16.5).

Upper-class Romans seated in the theatre were well fitted for the required role of approving, adoring spectator, as for many others. Even private iconospheres—at least so the evidence from Herculaneum and Pompeii and from Nero’s own Domus Aurea suggests—were theatrical. The walls of the houses not only of the elite seemed regularly to have been adorned with theatrical paintings, pre-eminently of subjects drawn from tragic myth. It is arguable that in early imperial Rome’s confounding culture the distinction between persona and person began to collapse. Certainly the distinction between ‘reality’ and ‘theatre’ dissolves conspicuously within the theatre/amphitheatre itself, where buildings burn, actors bleed, spectators are thrust into the arena, human and animal bodies dismembered, and pain, suffering, death become objects of the theatrical gaze and of theatrical pleasure.24 In the year after Nero’s death the emperor Vitellius sought popular support by joining ‘the audience at the theatre, supporters at the circus’ (in theatro ut spectator, in circo ut fautor, Tac. Hist. 2.91) only to become later the spectacle itself.

Tacitus’ account of imperial Rome’s distemper is prejudicial, in part myopic. The author of Annales had experienced at first hand the human degradation at the centre of the early principate, the paralysing nightmare of a tyrant’s court (in his case that of Domitian). As had Seneca. And, as in Tacitus, it shows. Indeed for Seneca late Julio-Claudian Rome was not simply a theatricalized, but a self-consciously dying, world. A world in which death was a source of aesthetic pleasure (NQ 3.18) and the death-wish (libido moriendi, Ep. Mor. 24.25) a paradigmatic emotion, as individuals

22 Philostratus Vit. Apoll. 5.8 mentions the role of Creon. Suetonius also records that Nero towards the end of his life intended to ‘dance Virgil’s Turnus’ (saltaturumque Vergili Turnum, Nero 54).

23 See Bartsch (1994: 2ff.).

24 Strabo 6.2.6, Suet. Gaius 35.2, Nero 11.2, 12.2, Mart. Spec. 7, 8, Epig. 8.30, Dio 59.10.3.