CONTENTS

List of Figures

List of Abbreviations

Edition and Translation: Alcuin’s Epitaph for Pope Hadrian I (by David R. Howlett)

Introduction: Charlemagne and Italy

Renaissance Rome: Hadrian’s Epitaph in New St Peter’s

The ‘Life’ and Death of Pope Hadrian I

Alcuin and the Epitaph

Recalling Rome: Epigraphic Syllogaeand Itineraries

Writing on the Walls: Epigraphy in Italy and Francia

Black Stone: Materials, Methods, and Motives

Aachen and the Art of the Court

Charlemagne, St Peter’s, and the Imperial Coronation

List of Manuscript Sources

Bibliography

Index

LIST OF FIGURES

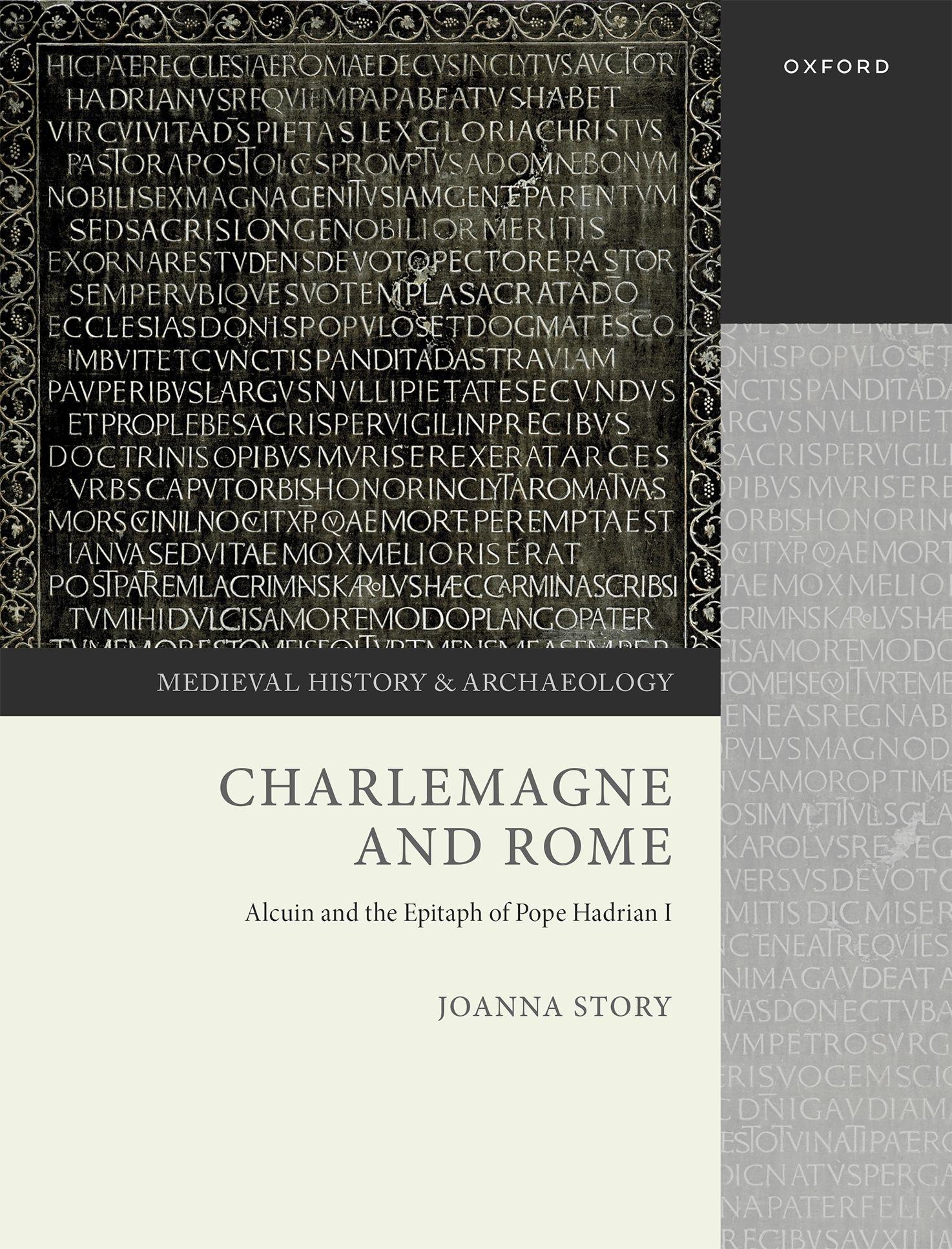

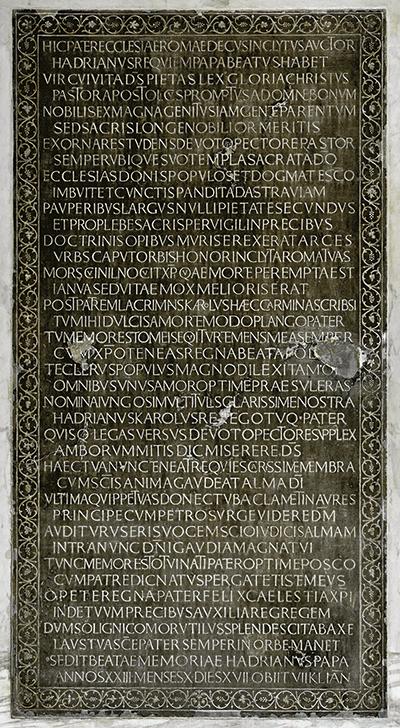

Frontispiece

The epitaph of Pope Hadrian I (d. 795). Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

0.1

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6

Jean Fouquet, ‘The Coronation of the Emperor Charlemagne’, GrandesChroniquesdeFrance(1455–60); Paris, BnF, Fr. 6465, fol. 89v. Reproduced by permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Charlemagne’s epitaph for Pope Hadrian I in the portico of St Peter’s in the Vatican with its seventeenth-century frame. Photo: Author, with kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Detail of the apse and south transept of the old basilica at St Peter’s from the 1590 engraving of Alfarano’s plan. Hadrian’s chapel is marked as no. 15, the Leonine chapel is no. 14 and the remains of S. Martino are labelled ‘a’. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Reconstruction of Old St Peter’s. Drawing: © Lacey Wallace.

Detail of Raphael’s ‘Coronation of Charlemagne’ from the Stanzadell’Incendioin the Vatican palace. Photo: Reproduced with permission of Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

The tomb of Pope Hadrian VI in S. Maria dell’Anima. The outer pair of columns are made of africanomarble, the rarest and most expensive coloured marble in antiquity. Photo: Author.

Donato Bramante (1505–6), ‘Sketches for the basilica of St Peter’s’ showing the outline of the new structure superimposed

over the old. Notice that the eastern piers stand within the nave of the old basilica. Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, Inv. GDSU n. 20 A. Photo: Reproduced by permission of the Ministero della Cultura.

The Porta del Popolo (built 1563–5). The four antique columns were taken from the exedra screens in the transept of the old basilica at St Peter’s. Photo: Author.

‘View of St Peter’s from the south west’, BAV, Collezione Ashby no. 329. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

Maerteen van Heemskerck (c.1536), ‘View of St Peter’s under construction from the south’. Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, 79 D 2a, fol. 54r. Photo: Reproduced with permission of the Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

Maerteen van Heemskerck (c.1536), ‘View of St Peter’s under construction from the south-east’. Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, 79 D 2a, fol. 51r. Reproduced with permission of the Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

Maerteen van Heemskerck (c.1536), ‘The new crossing and Bramante’s tegurium seen from within the north transept of Old St Peter’s’. Stockholm, National Museum, coll. Anckarsvärd 637. Photo: Courtesy of the National Museum of Fine Arts, Stockholm.

Giovanni Antonio Dosio (c.1564), ‘Sketch of the interior of St Peter’s basilia’, shown under construction, with Bramante’s teguriumand the ancient apse, seen from within the south transept; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, Inv. GDSU n. 91 A. Photo: Reproduced by permission of the Ministero della Cultura. Battista Naldini (?) (c.1564), ‘St Peter’s, view from the nave towards the apse and Bramante’s tegurium’. Note the stubs of the western transept wall on either side of the tegurium.

1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18

Hamburg, Kunsthalle, Inv. Nr 21311. Photo: Reproduced with permission of the Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

A watercolour by Domenico Tasselli (c.1611) for Giacomo Grimaldi’s AlbumdiSanPietro, showing the interior of the eastern part of the nave of St Peter’s, looking towards the murodivisorio. Note the numerous altars and monuments, and the door closing the arch in the murodivisoriowith steps leading up to the door and to the raised floor level in the new basilica beyond. BAV, Arch. Cap. S. Pietro, A.64.ter, fol. 12r. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

The doorway in the western wall of the south transept, showing the marble threshold and door jamb, the paving of the old basilica and, on the far left, the projecting wall of the tomb structure that fills the space between the doorway and the exedra pier. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

The face of the western pier that marked the boundary of the southern exedra. Abutting it to the right are two walls, both with painted decoration, which project slightly beyond the pier into the space of the transept. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Engraving of Alfarano’s plan of St Peter’s, ‘Almae urbis Divi Petri veteris novique Templi descriptio’, by Martino Ferrabosco, in G. B. Costaguti, ArchitetturadellabasilicadiSanPietroin Vaticano.OperadiBramanteLazzari,Michel’AngeloBonarota, CarloMaderni,ealtrifamosiArchitetti…(Rome, 1684). Photo: By kind permission of the Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

View of the façade of St Peter’s and its atrium by G. A. Dosio, engraved by Giambattista Cavalieri to show the opening of the Porta Santa by Gregory XIII on 24 December 1574; from, Ehrle and Egger, PianteeVedute, tav. 31. Roma, ICCD, Fototeca

1.19 2.1 2.2 2.3

Nationale, F8245, reproduced with permission of the Ministero della Cultura.

Drawing of the oratory of Pope John VII, from Grimaldi’s Instrumentaautentica. Hadrian I’s 783 inscription is labelled as Item M; the porphyry tomb of Pope Hadrian IV (1154–9) stands to the left, BAV, Barb. Lat. 2733, fols 94v–95r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

Detail from the StaMariaReginafresco, from the atrium of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome (right-hand side), showing Pope Hadrian I on the left with a square nimbus. Photo: Roberto Sigismondi (2011), reproduced by concession of the Ministero della Cultura, Parco archeologico del Colosseo.

Denarius of Hadrian I (issued 781–95); EMC1: no. 1032 (enlarged, x2). Obverse: CN[or H] ADRIANUS PAPA | IB reverse: VICTORIA DNN CONOB|H[adrianus]|R[o]M[a]. Photo: Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The AnnalesLaureshamenses, showing last part of the annal for 795 and beginning of the entry for 796; Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 515, fol. 2r, detail. Photo: Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

3.1

3.2

3.3

Detail of Hadrian’s epitaph, line 17. Photo: Author. Denarius of Charlemagne (issued 772–93). EMC1: no. 730 (PG 202) (enlarged, x2). Photo: Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

The colophon recording Charlemagne’s instruction to make this copy of Paul the Deacon’s Liberdediversisiquasticunculis ‘from the original’; Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, MS II 2572, fol. 1r. Photo: Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, Brussels.

3.4

‘Epitaphium Caroli’, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14641, fol. 31v (detail). Photo: Courtesy of the Bayerische

3.5 3.6 4.1

Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

A ninth-century copy of Alcuin’s ‘Epitaph for Pope Hadrian’; BnF, Lat. 2773, fol. 23v. Photo: Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

A twelfth-century copy of the LiberPontificalis, showing the end of the Lifeof Stephen II and the first twelve lines of Hadrian’s epitaph, which is completed on the next folio; BnF, Lat. 16897, fol. 33v (detail). Photo: Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The final ten lines of Hadrian’s epigram and the full text of the verses for Hildegard’s altar cloth; BAV, Pal. Lat. 833, fol. 29v.

Photo: Courtesy of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

4.2 4.3 4.4

Illustration showing the interior of a church with a ‘hanging crown’ over a draped altar. The Utrecht Psalter, Ps. 42: Iudica me; Utrecht, Rijksuniversiteitsbibliothek MS 32, fol. 25r (detail). Photo: Courtesy of Utrecht University Library.

The Ravenna mappa, showing woven bands of text. Reproduced from M. Mazzotti, ‘Antiche stoffe liturgiche ravennati’, FelixRavenna, 3rd ser., 53.ii (1950), 43. Photo: Courtesy of the Istituzione Biblioteca Classense, Ravenna.

The opening of the appendix to the Notitiaecclesiarumurbis

Romaewith the pilgrim’s itinerary of St Peter’s basilica. The first line on the page is the last of the account of cult sites in Milan; Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 795, fol. 187r. Photo: Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

4.5 4.6 5.1

Plan of St Peter’s and its oratories, s. viii/ix. © Lacey Wallace.

DescriptioUrbisRomae.The Einsiedeln Itineraries, No. 1; Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 326 (1076), fols 79v–80r.

Photo: Courtesy of the Stiftsbibliothek, Einsiedeln.

Detail of Hadrian’s epitaph showing coral fossils on the edges of the letter E. Photo: Author.

5.2 5.3

5.4

5.5

5.6

5.7

5.8

5.9

5.10

Detail of Hadrian’s epitaph showing the ornamental border with golden coloured pigment overlain by white lead in and around the vine scroll. Photo: Author.

Detail of the central motif in the lower ornamental border of Hadrian’s epitaph. Photo: Author.

Detail of Hadrian’s epitaph showing engraved ruling lines. Photo: Author.

Detail of Hadrian’s epitaph, showing part of lines 14–16. Photo: Author.

Hadrian’s epitaph: detail of letter T, showing traces of chisel marks. Photo: Author.

The epitaph of Pippin of Italy, d. 810, in Sant’Ambrogio, Milan (detail and complete text). Photo: Author.

The epitaph of Bernard of Italy, d. 817, in Sant’Ambrogio, Milan (detail and complete text). Photo: Author.

The LexdeimperioVespasiani, Musei Capitolini, Rome. Photo: Courtesy of Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Capitolini, Rome.

Maerteen van Heemskerck (c.1536), details of two drawings of the Lateran (conjoined here) showing the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in front of the loggia of Boniface VIII (c.1300) that projects from the southern end of the polyconch triclinium (the Saladelconcilio) built by Leo III (795–814); Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, 79 D 2a, fol. 12r and fol. 71r. Photo: Reproduced with permission of the Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

5.11

5.12

Pope Damasus’ eulogy at Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura. The text is not in any extant sylloge. Photo: Author.

Pope Damasus’ eulogy for S. Eutychius, at S. Sebastiano. This text was copied into the fourth Lorsch sylloge(L4). MECI, V.2. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Pontificio Istituto de Archeologia Cristiana, Rome.

5.13

Pope Damasus’ verses for the font at St Peter’s. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Part of an inscription from a pluteus at S. Pudenziana, naming Pope Siricius (385–98). Photo: Author.

Mosaic dedication inscription at Sta. Sabina (442–32). Pope Celestine’s name is in the top line, with the donor’s name, Peter, centrally placed in the middle of the text. Photo: Paolo Romiti, Alamy Stock Photo.

Inscription by Sixtus III for the Lateran Baptistery (the fifth of eight distiches). Photo: Author.

Verse inscription by Pope Leo I commemorating the restoration of the roof at S. Paolo fuori le Mura. MECI, X.5. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Pontificio Istituto de Archeologia Cristiana, Rome.

Inscription for Pope Vigilius after the Goths’ siege of Rome in 537/8. MECI, XI. 7/8. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Pontificio Istituto de Archeologia Cristiana, Rome.

Inscription for Pope John II (533–5) in S. Pietro in Vincoli. John’s name before his election (Mercurius) and his ties to S. Clemente are recorded in lines 2–3. Photo: Author.

Fragments from the epitaph of Pope Gregory I (d. 604). Photo: Author, with kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

The Column of Phocas, dedicatory inscription, 1 August 608. Photo: Gregor Kalas.

The epitaph of Theodore, d. 619, at Sta. Cecilia (detail). Photo: Author.

5.23

Inscription on a screen from the Oratory of Mary at St Peter’s dedicated by John VII (705–7). Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

6.2

A diploma of Pope Gregory II (715–31), recording a gift of lights to St Peter’s, as displayed in the portico in its seventeenth-century frame. Photo: Author, with kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro, Rome.

Pope Gregory III, record of the Council of 732 regarding the enactment of the offices to be said in his new oratory. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Prayers for Pope Gregory III, from the oratory of All Saints:

Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Verses by Gregory, cardinal priest of S. Clemente, describing a gift of books during the pontificate of Zacharias (741–52).

Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Pontificio Istituto de Archeologia Cristiana, Rome.

List of the feast days of male saints buried at S. Silvestro by Pope Paul I (757–67). Photo: Author.

A list of saints, from the pontificate of Paul I (757–67), at St Peter’s. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

Record of gifts of land by Eustathius and George, Sta. Maria in Cosmedin (s. viii med.) (detail). Photo: Author.

Inscription of Pope Hadrian I, 783, from the Chapel of John VII, St Peter’s. Photo: By kind permission of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano, Rome.

The black marble inscription of Verus, moritex, from Cologne (dimensions: 104cm × 82cm × 8cm; CIL XIII.8164a = ILS 7522). Photo: Courtesy of the Romisch-Germanisches Museum, Köln.

Map showing key places and the underlying geology of eastern Francia. © Tom Knott.

6.10

7.1

The modern quarry at Salet, Belgium (lower Viséan). Photo: Author.

Octagonal itinerary column from Tongeren, Belgium, made of black Mosan marble (36cm × 38cm). Brussels, Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Inv. No. B000189-001. Photo: CC BY–MRAH/KMKG.

Altar to the goddess Nehalennia, from Colijnsplaat, Netherlands, made of black Mosan marble. Photo: Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden.

Blausteinblocks in the masonry of the NNW exterior wall of the Carolingian chapel at Aachen. Note the large block with clamp and lewis holes showing likely reuse from a Roman structure.

Photo: Author.

Opus sectile from the upper floor at Aachen. Photo: Courtesy of Ulrike Heckner.

Black porphyry columns in Aachen. Reproduced by permission of the Domkapitel Aachen. Photo: Ann Münchow/Pit Siebigs.

Black porphyry column from the chapel of S. Zeno, Sta Prassede, Rome. Photo: Author.

Upper-level columns and arcading in the interior of the Aachen chapel. Photo: Author.

The Easter Table for the years 779–97 with marginal annotations recording the death of Pope Hadrian against the entry for 796 in the left-hand margin, and in the right-hand margin the places where Charlemagne celebrated Easter in the years 787–97. Würzburg, Universitätsbibliothek, M.p.th.f.46, fols 14v–15r. Photo: Reproduced with permission of Würzburg Universitätsbibliothek.

7.2

Dedicatory verses in Godesscalc’s Evangelistary. Charlemagne and Hildegard are named at the foot of the second column; Paris, BnF, NAL 1203, fol. 126v. Photo: Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Dedicatory verses from Charlemagne to Pope Hadrian in the Dagulf Psalter; Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 1861, fol. 4r (detail). Photo: Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

The Dagulf Psalter showing the Incipit facing the Beatus; Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 1861, fols 24v–25r. Photo: Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

The title page of a copy of the CollectioCanonum Quesnelliana; Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 191, fol. 3r. Photo: Courtesy of the Stiftsbibliothek, Einsiedeln.

Opening to the gospel of St John in the Abbeville Gospels; Abbeville, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 4, fol. 154r. Photo: Courtesy of the Archives e Bibliothèque patrimoniale, Abbeville.

The Lorsch Gospels, Incipitto the gospel of Luke. BAV, Pal. Lat. 50, fol. 7v. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

The Lorsch Gospels, Incipitto the gospel of John. BAV, Pal. Lat. 50, fol. 70v. Photo: Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome.

The title page to the four gospels; London, British Library, Harley MS 2788, fol. 12v. Photo: Reproduced with permission of The British Library Board.

Incipitto the Gospel of John; London, British Library, Harley MS 2788, fol. 162r. Photo: Reproduced with permission of The British Library Board.

The second set of bronze railings in the Aachen Chapel. Reproduced by permission of the Domkapitel Aachen. Photo: Ann Münchow/Pit Siebigs.

‘Bertcaud’s alphabet’; Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 250, fol. 11v. Photo: Courtesy of the Bergerbibliothek, Bern.

The dedication verses for the palace chapel, Aachen. The first two lines are at the foot of fol. 19r and the text continues with

8.1

8.2

six lines at the top of the first column of fol. 19v; Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Voss. Lat. 69, fol. 19 r/v. Photo: Courtesy of Leiden University Libraries.

Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 326 (1076), fol. 68r, detail showing the correction of the first word in line 5, from hincto hanc. Photo: Courtesy of the Stiftsbibliothek, Einsiedeln.

The Lateran Triclinium mosaic, as recreated in 1743. Photo: Author.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AASS

AFSP

Alfarano, DBV

ALMA

AMPr

Arch. Cap.

ARF

BAV

Bischoff, Katalog

ActaSanctorum.

L’Archivio della Fabbrica di San Pietro.

Tiberius Alpharanus, De Basilicae Vaticanae

Antiquissima et Nova Structura, ed. C. M. Cerrati (Vatican City, 1914).

ArchivumLatinitatisMediiAevi.

AnnalesMettensesPriores; B. de Simson, ed., MGH, SS rer. Germ (Hanover and Leipzig, 1905).

Archivio Capitolare.

Annales regni francorum unde ab a. 741 usque ad a. 829, qui dicuntur Annales laurissensesmaioresetEinhardi; F. Kurze, ed., MGH, SS rer. Germ. 6 (Hanover, 1895).

Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana.

B. Bischoff, Katalog der festländischen Handschriften des neunten Jahrhunderts(mit Ausnahme der wisigotischen), 4 vols (Wiesbaden, 1998–2017).

Bischoff, MS

BL

BnF

BSPV

B. Bischoff, Mittelalterliche Studien: Ausgewählte Aufsätze Zur Schriftkunde Und Literaturgeschichte, 3 vols (Stuttgart, 1966–81).

London, British Library. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

BasilicaSanctiPetriVaticani/TheBasilicaofSt Peter in the Vatican, ed. A. Pinelli, M.

Beltramini and A. Angeli, 4 vols (Modena 2000), I.i–ii (Atlas), II.i (Essays), II.ii (Notes).

CorpusbasilicarumChristianarumRomae:The early Christian basilicas of Rome (IV–IX Centuries), ed. R. Krautheimer, S. Corbett, and A. K. Frazer, 5 vols (Vatican City, 1937–77).

CodexCarolinus, ed. W. Gundlach, MGH, Epp. III, Epistolae Merowingici et Karolini aevi, I (Hanover, 1892), 469–657 (see also CeC).

Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina.

S. de Blaauw, Cultus et Decor . Liturgia e architettura nella Roma. tardoantica e medieval. Basilica Salvatoris, Sanctae Mariae, SanctiPetri, 2 vols (Rome, 1994).

Codex epistolaris Carolinus. Frühmittelatlerliche Papstbriefe an die Karolingerherrscher, ed. and German tr. F. Hartmann and T. B. Orth-Müller, Ausgewählte quellen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters Freiherr-vom Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe, 49 (Darmstadt, 2017); Codex epistolaris Carolinus. Letters from the popes to the Frankish rulers, 739–791, English tr. R. McKitterick, D. van Espelo, R. Pollard, and R. Price, Translated Texts for Historians, 77 (Liverpool, 2021). Both volumes put the letters in the order that they are found in the unique manuscript copy; thus, CeC 49 is the same as CC 60, using Gundlach’s wellestablished reference system.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, 17 vols (Berlin, 1871–1986).

CSLMA

ChLA

ED EHR

Einhard, VK

EMC1

Ep./Epp.

Codices Latini antiquiores: a palaeographical guide to Latin manuscripts prior to the ninth century, 12 vols (Oxford, 1934–72).

K. Gamber , Codices liturgici latiniantiquiores, Spicilegii friburgensis Subsidia, 1, 2 vols (Fribourg, 1963–4).

Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England.

Clavis des auteurs latins du Moyen Age. Territoire français 735–987, ed. M.-H. Jullien and F. Perelman, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio. Mediaevalis (Turnhout, 1994–).

ChartaeLatiniAntiquiores:FacsimileEditionof the Latin Chartersprior to the NinthCentury, 49 vols, ed. A. Brucker and R. Marichal (Olten and Lausanne, 1954–).

Ferrua, A., Epigrammata Damasiana. Sussidi allo studio delle antichità cristiane, 2 (Vatican City, 1942).

TheEnglishHistoricalReview.

Einhard, Vita Karoli; O. Holder-Egger, ed., EinhardiVitaKaroliMagni, MGH, SS rer. Germ. (Hanover and Leipzig, 1911). Translated by P. E. Dutton, Charlemagne’s Courtier: The Complete Einhard, Readings in Medieval Civilizations and Cultures, 2 (Peterborough, ON, 1998) and D. Ganz, Einhard and Notker the Stammerer: Two Lives of Charlemagne (London, 2008).

P. Grierson and M. A. S. Blackburn, eds, Medieval European Coinage, with a catalogue of the coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Vol. 1, The early Middle Ages (5th–10thcenturies)(Cambridge, 1986).

Epistola/ae, cited by edition number.

Facs.

FredegarCont.

ICURII.i

ICURn.s.

KdG

LP

MEC

Facsimile.

J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, ed. and tr., The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its continuations(London, 1960).

G. B. de Rossi, ed., Inscriptiones Christianae UrbisRomaeseptimosaeculoantiquiores, II.i: pars prima ab originibus ad saeculum XII (Rome, 1888), cited by item number.

InscriptionesChristianaeUrbisRomaeseptimo saeculo antiquiores: nova series, 10 vols (Rome, 1922–92), i: A. Silvagni, ed., Inscriptiones incertae originis; ii: A. Silvagni, ed., Coemeteria in viis Cornelia Aurelia, PortuensietOstiensi.

W. Braunfels and P. E. Schramm, eds, Karlder Grosse. Lebenswerk und Nachleben, 5 vols (Düsseldorf, 1967), i: Persönlichkeit und Geschichte, ed. H. Beumann; ii: Das geistige Leben, ed. B. Bischoff; iii: KarolingischeKunst, ed. W. Braunfels and H. Schnitzler; iv: Das Nachleben, ed. W. and P. E. Schramm; v: Registerband, ed. W. Braunfels.

Liber Pontificalis (cited by biography number and chapter); Le Liber Pontificalis, ed. L. Duchesne, 3 vols (Paris, 1886–1957), i–ii: texte, introduction et commentaire; iii: Additionsetcorrections.

Silvagni, A., ed., Monumenta epigraphica christiana saeculo XIII antiquiora quae in Italiae finibus adhuc exstant iussu Pii XII pontificismaximi, 4 vols in 7 (Rome, 1943); i: Roma; ii.1: Mediolanum; ii.2: Comum; ii.3: Papia; iii.1: Luca; iv.1: Neapolis; iv.2: Beneventum.

MGH

—DD

DD. Kar. 1

—Epp.

Epp. sel.

—Fontes

—Leges Capit.

Conc.

—Poetae

PLAC

—SS

SS rer. Germ.

—SS rer. Lang.

—SS rer. Merov.

ÖNB

OSPR PBSR

PL Rev.

Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

Diplomata.

Diplomata Karolinorum 1.

Epistolae.

Epistolae selectae.

Fontes Iures Germanici Antiqui in usum scholarum separatim editi. Leges.

Capitularia reges Francorum. Concilia.

Poetae Latini medii aevi.

Poetae Latini ævi Carolini I–III.

Scriptores (in Folio).

Scriptores rerum germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi.

Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI–IX.

Scriptores rerum Merovingicarum.

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalibliothek.

Old St Peter’s, Rome, ed. R. McKitterick, J. Osborne, C. M. Richardson, and J. Story (Cambridge, 2013).

PapersoftheBritishSchoolatRome.

J.-P. Migne, ed., Patrologiaecursuscompletus: sive biblioteca universalis, integra, uniformis, commoda, oeconomica, omnium SS. Patrum, doctorumscriptorumqueeccelesiasticorumqui ab aevo apostolico ad usque Innocentii III temporafloruerunt, 221 vols (Paris, 1844–64).

Revised version of the Annales regni Francorum; Annales regni francorum unde ab a. 741usque ada. 829,qui dicunturAnnales

SW, 799

laurissensesmaiores etEinhardi, ed. F. Kurze, MGH, SS rer. Germ. 6 (Hanover, 1895).

Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro.

Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/.

Settimane di studio del Centro Italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo.

C. Stiegemann and M. Wemhoff, eds, 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit. Karl der Große und Papst Leo III in Paderborn, 3 vols (Mainz, 1999), i–ii: Katalog der Ausstellung, Paderborn1999; iii: Beiträge.

Alcuin; The Bishops, Kings, and Saints of York, ed. P. Godman, Oxford Medieval Texts (Oxford, 1982), cited by line number. Universitätabibliothek/Universiteitsbibliotheek.

R. Valentini, and G. Zucchetti, eds, Codice topografico della città di Roma, 4 vols, Fonti per la Storia d’Italia 81, 88, 90 (Rome, 1940–53), i: Scrittori secoli I–IV; ii: Scrittori secoli IV–XII; iii; ScrittorisecoliXII–XIV; iv: Scrittori XV.