Land 1st Edition Robert G. Hoyland

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-the-holy-land-1st-edition-robertg-hoyland/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Holy Land H.G.M. Williamson Et Al.

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-illustrated-history-ofthe-holy-land-h-g-m-williamson-et-al/

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich Robert Gellately

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-illustrated-history-ofthe-third-reich-robert-gellately/

Three Pilgrimages to the Holy Land: Saewulf: A True Account of the Situation in Jerusalem / John of Würzburg: A Description of the Places of the Holy Land / Theoderic: A Little Book of the Holy Places Unknown

https://ebookmass.com/product/three-pilgrimages-to-the-holy-landsaewulf-a-true-account-of-the-situation-in-jerusalem-john-ofwurzburg-a-description-of-the-places-of-the-holy-land-theoderica-little-book-of-the-holy-places/

The Oxford Handbook of Central American History Robert Holden

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-centralamerican-history-robert-holden/

The Oxford History of the Third Reich 2nd Edition Earl Ray Beck Professor Of History Robert Gellately

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-the-thirdreich-2nd-edition-earl-ray-beck-professor-of-history-robertgellately/

Writing the Holy Land: The Franciscans of Mount Zion and the Construction of a Cultural Memory, 1300–1550 1st ed. Edition Michele Campopiano

https://ebookmass.com/product/writing-the-holy-land-thefranciscans-of-mount-zion-and-the-construction-of-a-culturalmemory-1300-1550-1st-ed-edition-michele-campopiano/

The Oxford Handbook of the History Phenomenology (Oxford Handbooks)

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-the-historyphenomenology-oxford-handbooks/

The Oxford History of the World 1st Edition Felipe Fernández-Armesto

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-theworld-1st-edition-felipe-fernandez-armesto/

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance 1st Edition Gordon Campbell

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-illustrated-history-ofthe-renaissance-1st-edition-gordon-campbell/

The OxfordHistory Ofthe Holy Land

H. G. M. Williamson was until recently Regius Professor of Hebrew at Oxford University. His expertise in the texts of the Old Testament is complemented by his active participation in the archaeology of the biblical period in the Holy Land.

Robert G. Hoyland is Professor of Late Antique and Early Islamic Middle Eastern History at New York University's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. His books include Arabiaand the Arabs (Routledge, 2001) and In God's Path (OUP, 2015). He has conducted fieldwork both in Israel/Palestine and in neighbouring regions of the Middle East.

The fifteen historians who contributed to The OxfordHistory ofthe Holy Landare all distinguished authorities in their field. They are:

JOHN J. COLLINS, Yale Divinity School

AVRAHAM FAUST, Bar-Ilan University

†ROBERT FISK, writer and journalist

LESTER L. GRABBE, University of Hull

RICHARD S. HESS, Denver Seminary

CAROLE HILLENBRAND, University of Edinburgh

ROBERT G. HOYLAND, New York University

KONSTANTIN KLEIN, University of Amsterdam

ANDRÉ LEMAIRE, École Pratique des Hautes Études

MILKA LEVY-RUBIN, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

NIMROD LUZ, Kinneret College, Galilee

DENYS PRINGLE, Cardiff University

ADAM SILVERSTEIN, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

PETER WALKER, Trinity School for Ministry

H. G. M. WILLIAMSON, University of Oxford

TheOxfordHistoryOfTheHoly Land

Editedby ROBERT G. HOYLAND

H. G. M. WILLIAMSON

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2023

The text of this edition was published in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Holy Land in 2018

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018 First published in paperback 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022946823

ISBN 978–0–19–288686–6 ebook ISBN 978–0–19–288687–3

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192886866.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Praise for The OxfordHistory ofthe Holy Land

‘Three great world faiths have invested so many hopes and passions in one relatively small part of the eastern Mediterranean seaboard and its hinterland, that there are risks even in calling it by a single name. This collective study of the “God-trodden land” is a richly informative, reliable, and sane guide to its troubled history: one valuable contribution to crafting it a more peaceful present and future.’

Diarmaid MacCulloch, University of Oxford

‘This book is a feast for lovers of the Holy Land. Serious and scholarly with substantial bibliography’

Bible Lands, Winter 2019

‘The Oxford History of the Holy Land fills a valuable place on the shelf of anyone interested in a more general overview of the significance of the Holy Land.…The authors do an admirable job of giving a modern academic historical overview that reconciles modern historical perspectives with traditional views informed by different religious faiths.'

Neil Xavier O'Donoghue, IrishTheologicalQuarterly

‘One-stop shopping for tourists, graduate students, and Sunday school teachers seeking reliable historical information.'

Kirkus Reviews

‘This is a remarkably elegant book, with its physical elegance matched by a corresponding elegance of content provided by noted and highly respected contemporary scholars in the archaeology and history of the biblical period of the Holy Land.'

Dale

E. Luffman, Association ofMormon Letters

ListofMaps

Introduction

The Birth of Israel

AvrahamFaust

Iron Age: Tribes to Monarchy

Lester L. Grabbe

Israel and Judah, c.931–587 BCE

AndréLemaire

Babylonian Exile and Restoration, 587–325 BCE

H. G. M. Williamson

The Hellenistic and Roman Era

John J. Collins

A Christian Holy Land, 284–638 CE

Konstantin Klein

The Coming of Islam

Milka Levy-Rubin

The Holy Land in the Crusader and Ayyubid Periods, 1099–1250

Carole Hillenbrand

The Holy Land from the Mamluk Sultanate to the Ottoman Empire, 1260–1799

NimrodLuz

From Napoleon to Allenby: The Holy Land and the Wider Middle East

Fisk

Pilgrimage

Peter Walker withRobertG. Hoyland

Sacred Spaces and Holy Places

RichardS. Hess andDenys Pringle

Scripture and the Holy Land

Adam Silverstein

FurtherReading

Index

List of Maps

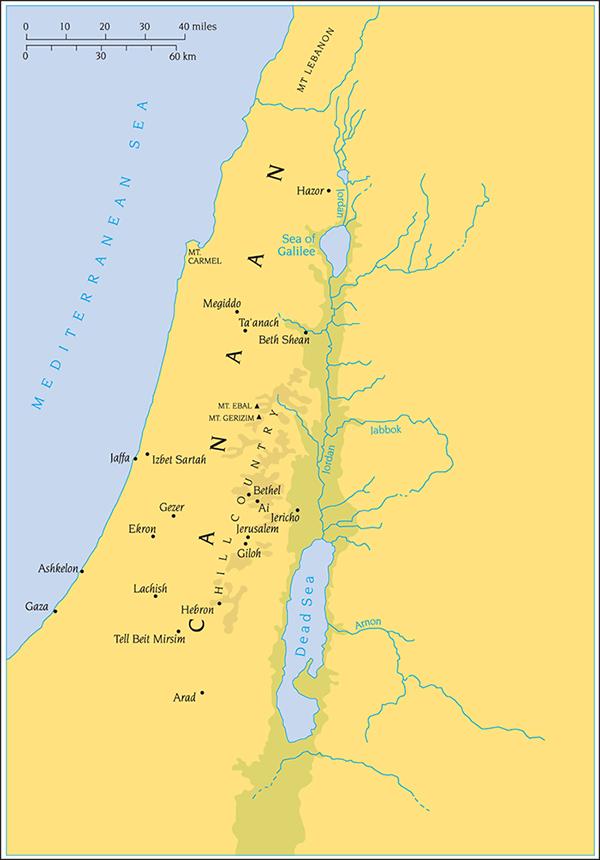

1.1

2.1

5.1

5.2 6.1 8.1 12.1

Map of the Holy Land in the earliest Israelite period

The Holy Land in the period of the Israelite monarchies

The cities of the Decapolis

Map of the Holy Land under Roman occupation in the first century

Map of the late antique Holy Land and neighbouring regions

Map of the Crusader states in Palestine, Syria, and Anatolia

Location of sacred spaces and holy places

Introduction

In an aide-memoire following the First World War, the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George wrote to his French opposite number Georges Clémenceau that Palestine was to be ‘defined in accordance with its ancient boundaries of Dan to Beersheba’. Lloyd George had been steeped in the Bible from his childhood, so that it is understandable, if politically astonishing, that he should have allowed his instinctive memory to influence his approach to modern political realities.

Different names and geographical definitions bedevil the history of this part of the world and none can do justice to the sweep of what we have set out to describe in the present volume. Precisely for that reason we have deliberately chosen the title Holy Land, a familiar name which has never featured on any map worth its salt. It serves to indicate that our intention here is far from political—and that is one good reason why we have called a halt in our historical survey at just the point where Lloyd George was clarifying his thoughts on the post-war settlement. But just as we have stopped short of the modern era, so we have not included anything about the thousands of years of occupation which preceded the biblical period. The Carmel Caves, for instance, have yielded evidence of some of the earliest human occupation known worldwide, a testimony to the geographical centrality of the region as a link between Africa and Europe. Jericho has often been called the word’s first city, and archaeology has revealed much about human occupation throughout the millennia since then.

The Holy Land, however, conjures up an approach to territory which is more cultural, and specifically religious, than political, however closely intertwined the two were until relatively recently.

This modest strip of land saw the birth of two world religions, Judaism and Christianity, and was of central significance to a third from its earliest days, Islam. It is sobering to recall that Jerusalem has been taken by military force by adherents of each of these three religions; no other city anywhere is of such central religious importance to each. It was therefore inevitable that we should begin our history with Abraham, whom each religion reveres. It is worth reflecting that according to our texts he owned no property in this land apart from a tomb, however, and that he had only limited engagement with the resident population.

The expression ‘Holy Land’ itself occurs first, and then only once, in the Hebrew Bible, at Zechariah 2:12: ‘The Lord will inherit Judah as his portion in the holy land, and will again choose Jerusalem’. These words were written quite late in the Old Testament /Hebrew Bible period, after the return of the Judeans from their exile in Babylon from 538 BCE onwards. The area was no longer independent at this time but divided between several provinces in the mighty Persian Empire. Neither here nor elsewhere are precise geographical divisions supplied. We are used to referring to the Holy Land in the much earlier period as Canaan, but that too did not exist as a single entity; it comprised a number of minor independent city-states under the overarching hegemony of Egypt. Then came the Israelites, and we eventually have two kingdoms during the first half of the first millennium BCE—Israel in the northern part and Judah (including Jerusalem) in the south. But to the west, along part of the Mediterranean coast, there were the Philistines, so that even then the territory was not united. And in that period the nearest we come to the expression ‘Holy Land’ refers initially to an area outside the land of Israel altogether, namely God’s ‘holy abode’ on Mount Sinai in Exodus 15:13, echoing the ‘holy ground’ where Moses encountered God in the burning bush at Exodus 3:5. From there we approach our more familiar usage when Psalm 78:54 reminds the worshippers in the Jerusalem temple that God ‘brought them to his holy border, the mountain that his right hand had won’.

Still, this is thin pickings for what became so influential a name in later centuries. It occurs a few times in early apocryphal Jewish writings after the close of the Old Testament period and then more frequently in the later rabbinic sources. It is completely absent, however, from the foundation documents of the Christian faith in the New Testament, and it did not become common Christian parlance (as Terra Sancta) until the Middle Ages, no doubt reflecting the attitude of European Crusaders and pilgrims. Accordingly, its use for maps has tended to be restricted to those included in Bibles, where the name is used anachronistically and without proper regard for either ancient or modern political realities. Medieval Muslims took some interest in the term because it appears in the Qur’an, where Moses is recorded as instructing the Israelites to ‘enter the holy land, which God has ordained for you’, though scholars were at odds over the definition of this term. The legal scholar Muhammad al-Tabari (d. 923), for example, says he knows of four main possibilities: ‘Mount Sinai and its environs’, ‘Jericho’, ‘al-Sham’ (which corresponds roughly to our term ‘The Levant’), and ‘Palestine and part of Jordan’. Yet the term did not enjoy circulation outside academic circles; rather, attention was paid to specific cities and sites, especially Jerusalem (simply called al-Quds, ‘holiness’, or Bayt al-Maqdis, ‘house of sanctity’) and the Temple Mount.

It fits with this spasmodic witness from antiquity that the region is not carefully defined; in the biblical reference cited above it seems to be restricted to Judah, a tiny part of what we usually mean by the term. In subsequent centuries its implicit definition will have varied according to the prevailing political and administrative circumstances. As with the varying definitions of the extent of the land in the Hebrew Bible, so subsequently the various regions within the southern Levant may be included or excluded as appropriate. While a basic working definition could be the land between the Jordan river on the east and the Mediterranean on the west, and between the Sinai desert in the south and the Hermon range in the north, the territory to the east of the Jordan was sometimes an integral part of the land as well, while at other times areas in the

north or the west were effectively excluded. As editors we have deliberately allowed our contributors freedom to concentrate on the natural geographical and national borders that suit their period of study most appropriately (see Map 1.1). Equally, it should be added, attention to some regions quite apart from the Holy Land itself has sometimes been imperative in order to understand what was going on there (Babylon in the biblical period, Europe at the time of the Crusades, and Turkey during the Ottoman period, for instance); to exclude such material could not be justified.

Two special features mark this History from some others and so deserve comment. First, in addition to the expected historical survey (which, incidentally, covers some 3,000 years, so that it cannot always enter into great detail), we have included three chapters on themes which transcend specific periods of history but which, in their different ways, are important to each of the three major religions and which, furthermore, contribute to the notion of a Holy Land: pilgrimage, sacred space, and Scripture. These are huge topics, of course, and so can effectively only be introduced here, but without including them we should not be able to do justice to some of the major underlying motives and values which drove the significant political actors.

Second, it is likely that, for the early period at least, most readers’ knowledge will derive from the Bible, and for many this remains an inspired source for religious belief and practice. Our greatly increased knowledge of the ancient world both from archaeological discoveries and from newly discovered texts of ancient Israel’s neighbours shows that we have to tread carefully when assessing the Bible from a purely historical point of view. It is far from our intention to cause any offence or deliberately to challenge personal beliefs, so we have asked all our authors to write with consideration towards those for whom a strictly historical approach may be unfamiliar. The fact remains, however, that these ancient texts were not written according to the methods or standards of modern historians and their purpose was religious, moral, or didactic, using at the same time all the stylistic skills they could bring to their task.

We do not believe that the results of modern historical research are in any way incompatible with the continuing use of the Bible as scripture. Nevertheless, it seems only right to warn readers in advance that the ‘story’ of ancient history may not always coincide with inherited preconceptions. Our hope is that all may nevertheless learn from, as well as enjoy, this summary of current understanding, and that through such understanding appreciation of what each of the faiths had to offer may be deepened without the hostile fragmentation which has characterized much of the history we trace here and which still, sadly, is prevalent in the modern world.

The Birth of Israel

Avraham Faust

The Beginning of Israel: The Biblical Narrative

The well-known biblical story of Israel’s birth and emergence is the story of a family, and how it became a people. Abraham left his home in Mesopotamia and emigrated to Canaan. This is where he lived with his wife, Sarah, and his children Isaac and Ishmael. His grandchild (Isaac’s son)—Jacob—and his great-grandchildren went down to Egypt, as an extended family or a lineage (hamulah). They stayed there for a few generations, multiplied, were then enslaved, and eventually left in the epic story of the Exodus, led by Moses. After forty years of wandering in the Sinai desert, they finally entered Canaan under the leadership of Joshua and conquered it. Joshua’s campaign began with the conquest of Jericho, where the Israelites, through the help of a local harlot by the name of Rahab, conquered the city after encircling it for seven days, blowing rams’ horns until the city walls miraculously crumbled. This was followed by the eventual conquest of the city of ‘Ai, and Joshua’s campaigns against coalitions of kings in the southern and northern parts of Canaan. Following the conquest, the land was divided between the various tribes, named after Jacob’s descendants. Despite a few sidestories that interrupt its flow (like the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38), the story is very clear, and the narrative flows quite smoothly.

Problems with the Narrative

Still, the story is not completely uniform, and it includes some intriguing features. Thus, although Abraham continued to live for fifteen years after Jacob’s birth, the story never mentions them meeting, and while Isaac, Abraham’s son and Jacob’s father, is mentioned in connection with both figures, Abraham and Jacob never interact. Another feature that raises some eyebrows lies in the apparent contradiction between the account of the conquest in the book of Joshua and the description of the land that was not conquered (in both the books of Joshua and Judges). Thus, cities like Gezer, Megiddo, and Ta’anach, are explicitly mentioned as being conquered by Joshua (Josh. 12:12, 21), but also appear in the description of the remaining land that was not conquered (Judg. 1:27, 29). These are but two examples out of many, and to such inconsistencies one has to add the growing discrepancies between the available historical and archaeological information we possess and some parts of the biblical narrative. Thus, as we shall see below under the section ‘Archaeological Background’, during much of the period discussed, Canaan was under Egyptian rule, but this is not acknowledged in the biblical stories. And while such discrepancies, or missing data, might be explained one way or another, there are even more direct contradictions between the biblical narrative and the historical and archaeological data at our disposal; for example, cities that are mentioned in the conquest stories in the Bible (like ‘Ai) did not in fact exist at the time when the stories are supposed to have taken place (we will discuss the chronology in more detail below under ‘Chronological Framework’). Such discrepancies gradually eroded the historical validity of the texts. The growing understanding (beginning centuries ago, of course) that the texts were written down many years after the events they were supposed to describe took place, that they went through a long process of transmission, and that they were extensively edited for various (mainly theological) purposes, only exacerbated the texts’ reliability problem, casting more doubts on the historicity of large portions of the well-known narratives.

1.1 Map of the Holy Land in the earliest Israelite period

Other elements in the stories seem to be more in line with what is known on the basis of modern research, and the process of the Israelite settlement in the more mountainous parts of the country, rather than in the valleys and plains, can be identified archaeologically (perhaps in accordance with the information supplied in Joshua 13:1–7, 17:18, and throughout the book of Judges, where the mountainous regions are the core of the Israelite settlement). The name Israel is attested in an Egyptian victory stela, dated to this period (late thirteenth century BCE). Other elements of the narrative are to a large extent beyond the realm of modern scholarship. Thus, while the background that is reflected in the stories about the Patriarchs and Matriarchs can be (and is) debated, their existence, and the historicity of the stories about these individuals and their small families, is largely outside the scope of scholarship. After all, we cannot expect to find documents or artefacts related to individuals, or even a family, after almost 4,000 years, and as we shall see below under ‘The Israelite Settlement: Assessing the Evidence’, even the exact background behind the stories continues to elude scholars.

It seems, therefore, that while some parts of the biblical narrative (at least some of its general outlines) appear to be in line with modern research, other parts are seriously challenged (if not completely undermined) by it, and some elements of the story remain outside scholarship’s domain, or are, at best, at its fringes. Consequently, there is not much agreement among scholars about any aspect of Israel’s early history or the historicity of the Bible. Some scholars view the biblical narrative as mostly reliable testimony for history, while others deny any historical value to the texts, and view them as a very late, literary creation which is of practically no use for the study of the periods it purportedly describes. Most scholars are located somewhere along a broad spectrum between these two extreme views.

So how can we proceed and reconstruct the story of Israel’s emergence in Canaan? It appears that a combination of the vast archaeological data we possess and the (more limited) historical information at our disposal, through a very careful and critical reference to the biblical narratives, can allow us to reconstruct Israel’s development. While very little can be viewed as a consensus among scholars, this chapter aims to present a plausible middle ground between the two more extreme approaches. We will begin our journey by presenting the chronological framework, and since the biblical story, briefly summarized above, is probably familiar, we will proceed by describing the situation in Canaan in the second millennium BCE, in the periods which are usually known by the names Middle Bronze Age (roughly 2000/1900–1550 BCE), Late Bronze Age (roughly 1550–1200 BCE), and Iron Age I (roughly 1200–970 BCE). We will then summarize the debate regarding the Israelite settlement, and proceed to offer a broad reconstruction of the processes through which Israel emerged in Canaan: we will review the group’s early developments, until the formation of the monarchy in the Iron Age II (in the tenth century, according to most scholars; see Chapter 2), and will suggest some possible insights into the way the biblical story—as we know it today—evolved.

Chronological Framework

Attempting to synchronize the archaeological periods with the biblical events and stories is not always a straightforward enterprise. The dating of archaeological periods addressed in this chapter, while relying on synchronisms with adjacent regions, was developed largely independently of the biblical narratives, and stands on its own. This statement might seem somewhat surprising, given how much biblical archaeology developed in the shadow of the biblical texts. Still, although nobody would deny that biblical texts influenced the archaeological inquiry in the Holy Land, scholars were usually critical (at least, by the standards of their time) and did not simplistically accept the biblical framework. The dating of the

Israelite settlement in Canaan is a good example of this. The Israelite settlement is dated by most scholars, from all schools of thought, including those who accepted the historicity of the conquest narratives in the book of Joshua, to (roughly) 1200–1000 BCE, and its beginning is dated to the late thirteenth century at the earliest. As we shall presently see, chronologies that are based on the Bible alone date the conquest to about 1400 BCE. This 200-year gap suggests that archaeologists followed the archaeological data, and rejected the biblical chronology when they found that the two did not match (although this does not negate the significance of the biblical chronology in influencing the general landscape of historical reconstruction). Nowadays, many of the dates are decided on the basis of scientific methods, mainly carbon 14 dating, which somewhat changes the traditional dating of some periods.

Biblical chronology, of course, relies first and foremost on the dates supplied in the Bible. One can create a chronological sequence that incorporates the period of the Patriarchs, and even the descent to Egypt and the slavery there, and a biblical chronology of the period of the monarchy in Israel and Judah can also clearly be compiled. The first part—that of the Patriarchs and the slavery in Egypt—is of course much more problematic and relies on a few sketchy and sometimes contradictory pieces of information, while the chronology of the period of the monarchy is more reliable. The most problematic feature, however, is the attempt to connect the two parts—the period of the Patriarchs and the sojourn in Egypt on the one hand and that of the monarchy on the other—something which relies on just one verse. 1 Kings 6:1 states that the construction of the Temple by Solomon was completed 480 years after the Exodus. Since the construction of the Temple was dated by many to around 960 BCE (though it might well have been somewhat later), then the Exodus, which ended the period of slavery in Egypt, should have occurred in about 1440 BCE, and the conquest of Canaan (after forty years in the desert) at about 1400 BCE. And the Patriarchs lived a few hundred years earlier (the exact time of the Patriarchs depends on which biblical verses one uses to create the chronology).

The biblical chronology, however, is not only sketchy, but even the available data are problematic on a number of counts. First of all, many of the numbers that are mentioned in the texts seem typological. Forty years, for example, is used quite often, and seems to designate a lengthy period of time—perhaps a generation—rather than an exact duration of time. Additionally, did the Patriarchs (and other biblical figures) really live for so many years—175 years for Abraham, for example? Or are the numbers exaggerated? Even the 480 years that supposedly separated the Exodus from the completion of the temple in Jerusalem—the only figure that connects the more reliable dates of the later monarchy with those of Israel’s prehistory—seems typological, and a number of scholars have pointed out that it might have been a result of a schematized counting of twelve generations (of forty years each). Thus, a more realistic figure for twelve generations would be 240–300 years, and would date the Exodus, and by extension the settlement in Canaan, to the thirteenth, even the late thirteenth century (we shall return to this issue below under ‘Israel’s emergence’).

The problematic nature of the biblical chronology is exemplified by the debate over the date of the patriarchal narratives. Even scholars who consider the stories to reflect a specific historical background vary greatly in dating them, and the dates supplied cover approximately a millennium. This great variation is partly the result of some scholars not accepting the biblical sequence of events as such. Still, many of those who accept the biblical sequence of events as broadly historical simply use its very unclear nature to support the period in which they find more cultural and social parallels to the background which is reflected in the stories. Most of the latter, however, place them somewhere between 2000–1500 BCE. When discussing the Exodus and the settlement, the situation is somewhat clearer. As noted, a literal reading of 1 Kings 6:1 would place the Exodus in the fifteenth century BCE, and the conquest of Canaan at the beginning of the fourteenth, but we have seen that a more critical reading of the verse will direct us to the thirteenth

century BCE, and this seems to be more in line with the external evidence at our disposal (see the following section).

We will now begin our archaeological survey, which supplies the background for Israel’s emergence, at the beginning of the second millennium BCE—in the Middle Bronze Age.

Archaeological Background

During the Middle Bronze Age (roughly 2000/1900–1550 BCE) Canaan experienced intensive urbanization, especially in the low-lying parts of the country, and to a more limited extent also in the highlands. Many cities were surrounded by massive earthworks, which gave the mounds their present form and to a large extent even created the Levantine landscape of today, which is dotted by mounds. The political structure of the era is not completely clear, but it is likely that the country was divided between many independent or semiindependent city-states. The period is regarded as representing a demographic peak in the area more generally, and some scholars estimate the population as about 140,000 (west of the Jordan). Although the figure is far from certain, and is questioned on many grounds, it does suggest, when compared with the demographic estimates of other periods, the prosperity of the period, something also reflected in the settlement remains uncovered by archaeologists. The relations with Egypt during the time of the Middle Kingdom are not clear. The Execration Texts are groups of texts, uncovered in Egypt, in which names of local rulers in Canaan were inscribed on bowls or figurines and were apparently used for voodoo-like purposes, probably to secure their rulers’ loyalty to Egypt. The existence of these texts might suggest that the Egyptians felt some authority over the region but this is not certain. In the later part of the Middle Bronze Age (known in Egyptian history as the Second Intermediate Period) Asian/Canaanite dynasties (known as the Hyksos) ruled over much of lower (northern) Egypt (the Nile delta), and the region was extensively settled by Canaanites who maintained close connections with Canaan itself.

During the sixteenth century BCE the Hyksos were ousted and were replaced by the eighteenth dynasty (often referred to as the ‘Hyksos expulsion’)—an episode that also marks the beginning of the new kingdom of Egypt. This triggered many campaigns into Canaan, and many cities were devastated in the course of the century. Many archaeologists consider this as the beginning of the Late Bronze Age (roughly 1550–1200 BCE). Although there is much continuity in culture between the two periods, the settlement and demography were greatly affected by the campaigns, and despite gradual recovery during the Late Bronze Age the country did not recover its Middle Bronze Age demographic peak until some point in the Iron Age. Population estimates for the end of the Late Bronze Age (i.e. after the recovery from the nadir of the sixteenth century) are between 46,000–70,000, and although the figures are uncertain, the comparison with the Middle Bronze Age estimate is quite telling. Settlements were concentrated in the lower parts of the country, and the highlands were only sparsely settled. From at least the fifteenth century, the country was apparently nominally subjugated to Egypt, and this situation prevailed through the nineteenth dynasty (roughly the thirteenth century BCE) and well into the time of the twentieth dynasty (until the middle of the twelfth century or slightly later). As part of their rule over Canaan, the Egyptians built garrisons in a few places (e.g. Gaza, Jaffa, Beth Shean), and the rest of the country was divided between many city-states, which were vassals of Egypt. Egyptian sources, and especially the Amarna letters (fourteenth century BCE), supply a wealth of information on the political and social organization in Canaan at the time, and we know of the existence of many marginal groups which were active outside the settlements, and whose activity led to severe unrest. Most notable among these groups are the notorious Habiru, composed of outcasts or exiled people from various backgrounds, who seem to have caused much unrest throughout the country (such groups were already known in earlier periods). It is a common accusation made by vassal Canaanite princes that their opponents are collaborating with the Habiru. Another group (or groups) mentioned in the Egyptian sources is that of the Shasu—tribal groups of pastoral

nomads that were active outside the settled areas or on their fringes in both Cisjordan (i.e. west of the river Jordan) and Transjordan (i.e. east of it). Towards the end of the period—during the thirteenth and early twelfth centuries—the Egyptians apparently strengthened their hold over Canaan. Archaeologically, this is expressed, for example, by the construction of the so-called Egyptian governors’ residencies.

The material culture of the period reflects the existence of many social groups and social classes. Imported pottery is abundant, and some scholars refer to a period of internationalism. Decoration on local pottery is common and was probably used to convey differences between classes and groups. While not many dwellings have been excavated in their entirety, many public buildings, including palaces and temples, are known to archaeologists, reflecting the social distinctions and hierarchy that characterized this period. This is also reflected in burials: hundreds of burials of various types are known from this period, and the differences between them were probably also used to convey social differences between groups, families, and even individuals.

A series of events, beginning in the late thirteenth century and ending around the middle of the twelfth century, marks the end of the Late Bronze Age and the transition to the Iron Age in the region. These include the fall of the Mycenean civilization, the demise of the Hittite Empire, the destruction of various major cities like Ugarit, and eventually Egypt’s withdrawal from Canaan and its political decline. As far as Canaan is concerned, these large-scale changes (marking the beginning of the Iron Age) were accompanied by a decline in many of the urban centres that existed in Canaan—mainly in the lower parts of the country as well as by the emergence of two additional phenomena: the Sea People, most notably the Philistines, who came from somewhere in the Aegean world or its fringes and settled in the southern coastal plain, and the Israelite settlement in the highlands.

The term ‘Israelite settlement’ refers to hundreds of small sites that were established during Iron Age I—beginning at some point in the second half of the thirteenth century—in the highlands of

Canaan in both Cisjordan and Transjordan, and mainly in the area north of Jerusalem, in the region of Samaria. Most of the settlements were quite small, less than 1 hectare in size, and were not densely settled. Many of the houses were long houses, of the type that later crystallized into the well-known four-room house which dominated the urban landscape of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the Iron Age II (tenth–sixth centuries BCE), and the economy was based on a mixture of grazing, growing grains, and the cultivation of olives and vines. The material culture uncovered in these sites was quite rudimentary, and included a very limited ceramic repertoire that was composed mainly of large pithoi (mainly of the type known as the collared rim jar), cooking pots, and bowls.

The pottery was simple and undecorated and did not include imported pottery, not even the highly decorated Philistine pottery that was produced in the nearby southern coastal plain, and which constituted nearly 50 per cent of the assemblage in many eleventhcentury sites there. Hardly any burials are known from these villages, probably because the population buried their dead in simple inhumations in the ground.

The association of these sites with the Israelites was based not only on the (rough) temporal and (more exact) spatial correspondence with the biblical testimony regarding the areas in which the Israelites settled but also on the clear connections between the culture unearthed in these settlements and the culture of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah of Iron Age II, as well as the reference in an Egyptian stela by a pharaoh called Merneptah to an ethnic group that he called Israel. The stela is dated to the late thirteenth century, and although the exact location of this group is not stated, most scholars view it as referring to the settlement phenomenon described above, or part of it.

The Israelite Settlement: The Growing Debate

While the Israelite identity of the settlers was not questioned until recently, there was a major debate on the process through which the

settlements came to be. Albrecht Alt, a German biblical scholar, noted as long ago as 1925 that there is a discrepancy between the description of a military conquest of the entire country, as depicted in the main narratives in the book of Joshua, and the situation on the ground following the conquest as described in the narratives in the books of Judges, 1–2 Samuel, and the descriptions of the remaining land in Joshua 13:1–7, Judges 1:27–35, in which the Israelites settled only parts of the country, mainly in the highlands. Moreover, from the Egyptian sources that relate to Late Bronze Age Canaan prior to the appearance of the Israelites, it appears that the Canaanite centres of settlement were concentrated in the valleys, the Shephelah (the low-lying region between the Judean hill country and the coastal plain), and the coast, whereas the highlands were only sparsely settled prior to the Israelite settlement. Comparing the Late Bronze Age Canaanite settlement distribution with that of the later Israelite settlement made it clear, argued Alt, that the Israelites settled in less hospitable regions that were largely devoid of Canaanite settlement anyway. This picture, of settlement in sparsely populated and inhospitable regions, does not correspond with a military conquest in which the conquerors annihilate the entire country and can settle wherever they choose, but rather with a more peaceful, and mostly non-confrontational process in which the Israelites occupied the sparsely settled regions of the country simply because they were not populated and so were available for settlement. Alt, therefore, concluded that the Israelite settlement was a long, gradual, and mainly peaceful process, in which pastoral groups crossed the Jordan in search of pastoral lands, and gradually settled in the relatively empty parts of the country. While the process was mainly peaceful, it was accompanied by occasional confrontations and wars. Towards the end of the Iron Age, when Israel’s national history was composed in Jerusalem (by the so-called Deuteronomistic school, that was probably active from the seventh century BCE onward), the various traditions that commemorated the warring episodes (some historical, some clearly more mythical in origin) were combined into the monumental history

of Israel. This period of Israel’s history was situated between the Exodus and the period of the Judges, and attributed to a local hero of the tribe of Ephraim: Joshua. According to Alt, therefore, the conquest that is described in the book of Joshua never actually happened. Due to the way it reconstructs the settlement process, this school of thought is often called the peaceful infiltration school (or theory).

William F. Albright, sometimes regarded as the doyen of biblical archaeology in its golden age between the two World Wars, strongly opposed this view. He claimed that the story in Joshua is historical, at least in its general outlines, and that the Israelite tribes did conquer Canaan by force. Albright introduced archaeology into the debate, and argued that archaeological inquiry can prove the historicity of the conquest. He suggested that scholars should excavate Canaanite cities (mainly those mentioned in the conquest narratives), and should the Late Bronze Age occupation be devastated towards the end of this period, it would suggest that the conquest traditions are historical. Albright went on to excavate the mound of Tell Beit Mirsim in the southeastern (inner) Shephelah, and was involved in additional projects, where evidence for violent destruction of the Canaanite cities of the Late Bronze Age was indeed unearthed. In light of its acceptance of the historicity of the main narratives in the book of Joshua, this school came to be known as the unified conquest school (or theory).

The debate between these two schools continued throughout most of the twentieth century, more and more scholars joining in, with figures like the German biblical scholar Martin Noth and the Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni taking the leading role in the peaceful infiltration school, and the American biblical scholar and archaeologist George E. Wright, the American biblical scholar John Bright, and the Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin taking the leading role in the unified conquest school. Members of the latter school stressed the sites in which the Canaanite cities were devastated and destroyed around the end of the Late Bronze Age (e.g. Tell Beit Mirsim, Hazor, Lachish, Bethel, and many others), while their

opponents emphasized the sites which did not even exist at the time (e.g. Arad, ‘Ai, Jericho), and the large gap between the destruction of some of the sites that were destroyed—about a century separates the destruction of Hazor and Lachish—which does not allow these destructions to be attributed to a single campaign.

Notably, while these two schools were the dominant ones during most of the twentieth century, additional theories developed over the years. In the 1960s, and mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, a new approach was developed (mainly by George Mendenhall and Norman Gottwald), which viewed the settlers as being mainly of Canaanite descent, and as local peasants who rebelled against their overlords, and fled to the highlands, where they met a small group of people who did come from Egypt, and together they formed ‘liberated Israel’. Although this view—called the peasants’ revolt or social revolution—was not directly supported by many scholars, it greatly influenced research and, indirectly at least, altered the academic discourse.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s an even newer approach was developed (separately, and with some differences) by the Israeli scholars Israel Finkelstein and Shlomo Bunimovitz, who noted that when viewed in the long term the settlement process of Iron Age I was only part of a larger cyclic process of settlement and abandonment in the highlands. This approach, which resulted from the systematic study of the discoveries made in the many archaeological surveys conducted in the highlands, noted that during the Early Bronze Age (third millennium BCE) the highlands were densely settled, but that settlement declined drastically in the Intermediate Bronze Age (late third millennium). Large-scale settlement was resumed in the early second millennium (Middle Bronze Age), but the new settlement phase persisted for only a relatively short period of time, and during the Late Bronze Age, as we have seen, settlement in the highlands was again very sparse. Then, in Iron Age I, large-scale settlement in the highlands was resumed. Identifying this pattern, it was argued, put the settlement wave of Iron Age I in general, and Israel’s emergence in particular,

within a broader perspective, so that it should not be viewed as a unique event, but rather as part of the cyclic process of settlement and abandonment in the highlands. Moreover, Finkelstein argued that settlement abandonment and decline (as between the Middle Bronze and the Late Bronze Ages) does not mean that the inhabitants died or left the region, but rather that they abandoned their settled way of life, and became semi-nomads within the very same region. Movement along the settlement–nomadic spectrum is a well-known phenomenon in the Middle East. Nomadism occurs when settlers change their main economic mode, increase their herds, leave the permanent settlement and come to rely mainly on their herds for subsistence. When the populations’ livelihood is based on nomadic pastoralism, argued Finkelstein, they do not leave many material remains—hence the rarity of finds attributed to this era in the highlands. Such phenomena are known in the Middle East in various periods, even for reasons as mundane as overtaxation and recruitment to the army. The reason the Middle Bronze Age settlers in the highlands might have reverted to a more nomadic way of life does not concern us here, but according to the new theory the population remained as nomads in the highlands during the following centuries, only to resettle in the late thirteenth and twelfth centuries BCE. Thus, according to this view, the settlers were not outsiders, but rather local pastoral nomads who settled down after a few hundred years of a pastoral livelihood that did not leave much by way of remains in the archaeological record of the highlands. Due to its reference to long-term processes, and following its explicit reference to the French AnnalesSchool, this approach is sometimes called the ‘longue durée’ approach, or the ‘cyclic process’.

The last two schools of thought (the ‘social revolution’ and the ‘longue durée’ perspectives) viewed the settlers, or most of them at least, as ‘local’ people (whether semi-nomads or settled population) who lived in the region for many generations, and who for various reasons settled down in the highlands (or moved there from the lowlands, but not from outside Cisjordan). This new trend towards viewing the settlers as ‘locals’, and not as a new population coming